7 Commodities, Centers, Peripheries

Whenever people have achieved a surplus above and beyond mere subsistence, trade and the accumulation of resources have led to urbanization. Cities at the nodes of these trade networks have become centers of wealth, power, and culture. Artists and craftspeople often find patrons or markets for their work in cities, and government administrators and businesspeople often leave extensive records. So cities, both ancient and modern, are usually full of interesting information for historians.

But just because they offer so much information about the past, we should never suppose that cities were the only places that mattered. Often historians interested in culture, or politics, or social movements focus too much attention on the cities where art was displayed, where governments debated, and where workers demonstrated. This narrow focus can distort our understanding of the past by suggesting that everything that happened in the city originated in the city. In fact, cities have always been centers for the accumulation, processing, and consumption of resources that usually originate in the hinterlands that surround them.

As transportation improved, the hinterlands that were the sources of raw materials could be farther away. Grain from upstate New York farms could float down Erie Canal and the Hudson River to New York City. Cotton from Southern plantations could become cloth in Lowell mills. And silver mined in Potosí could become money in London and Beijing. In each case, New York, Lowell, London, and Beijing were just as dependent as they had ever been on their hinterlands, even though increasing distance might seem to obscure the relationship. It is important, as the distances widen and interactions become more complicated, to be careful we do not lose sight of the economic lifelines tying the centers with the peripheries.

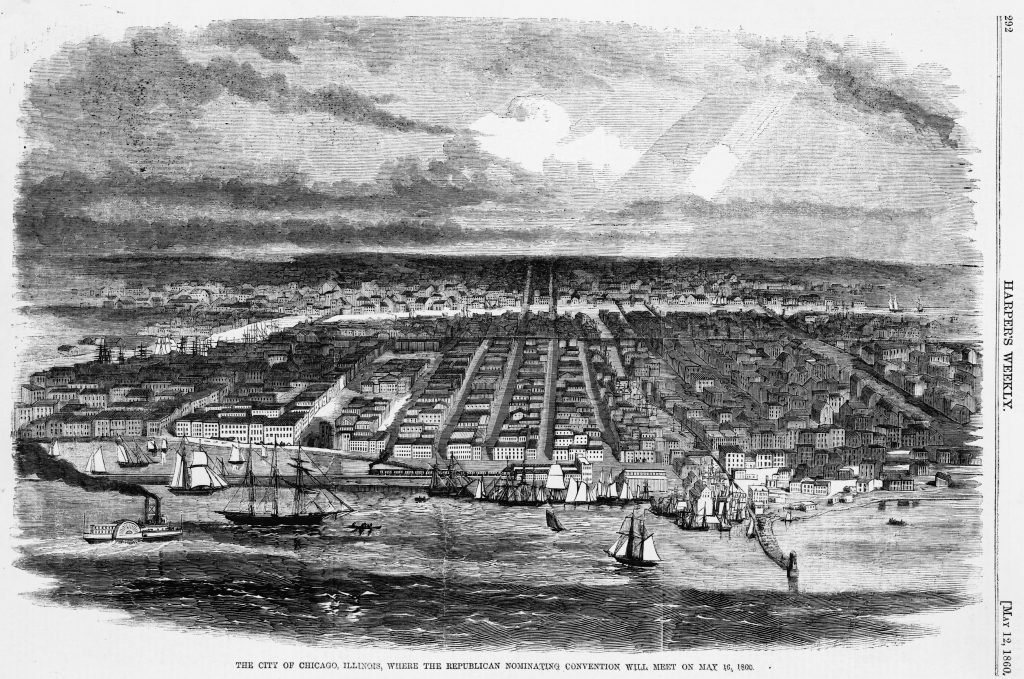

In this chapter we will consider the rise of new cities and new hinterlands as Americans pushed westward. The cities that developed on rivers, lakeshores, and at railroad junctions benefited from the advances in transportation discussed previously. But the transportation would have been pointless and the cities would have remained empty without the surrounding rural areas that supplied foods, fuels, and building materials. And the commodity agriculture, meat production, and forestry that developed alongside the cities we will consider in this chapter likewise depended on urban businesses and populations who were both the processors and often the consumers of their products.

Porkopolis

Recall how we previously observed difficult-to-ship grain west of the Appalachians become distilled into more portable whiskey by early Americans. This conversion into a commercial product for a distant market had been possible because there was more grain harvested than local farm families needed to survive, and also because rural people needed cash to buy things they could not make for themselves. Distilling whiskey not only made their surplus grain easier to transport, it increased the grain’s value per pound, and it added variety and interest that plain grain or flour lacked. In modern business terminology, the farmers diversified and added value.

A similar increase in variety and value occurred when grain was fed to domesticated animals such as poultry, cattle, and pigs. Even in primitive conditions, most people prefer not to live by bread alone. In subsistence societies, domesticated creatures usually foraged for themselves or ate waste products not fit for humans. In some societies, animals have continued to occupy this default livestock niche (some contemporary food activists argue we should move back toward this approach). But in America, when there was a surplus, even foods that could be eaten by people were often fed to livestock. These animals became a luxury food for consumers and a living bank account for their owners. They stored the food energy of perishable surplus grains and vegetables in their flesh until there was a shortage, and then they were eaten. As time went on and surpluses became more dependable, meat became a commodity that farmers could raise and sell for cash.

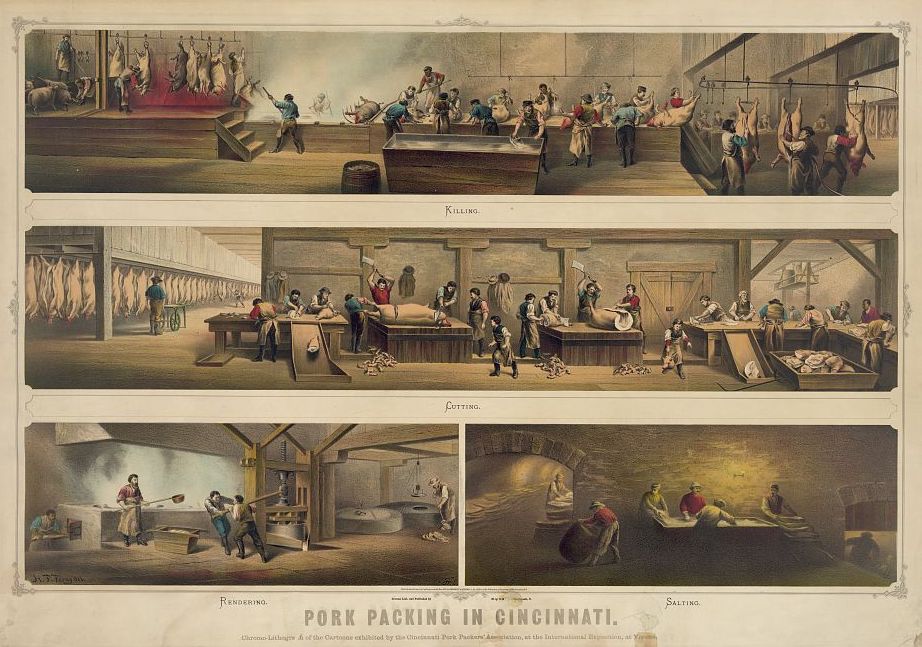

Pigs are extremely efficient converters of surplus plant foods to meat. They are omnivores that grow quickly and are able to produce twice as much meat per pound of grain as sheep or cattle, which are ruminants and prefer grasses. A sow can be bred much earlier than a heifer, and will produce a litter of 6 to 12 piglets after only four months gestation. Pigs were a favorite of homesteaders and frontier farmers because they would eat anything. Pigs could be turned loose to forage for acorns and were a great help to farmers rooting up tree stumps to clear fields. And pigs became the frontier’s first big meat product raised for city markets because unlike beef, their flesh is easily preserved by smoking or by salting.

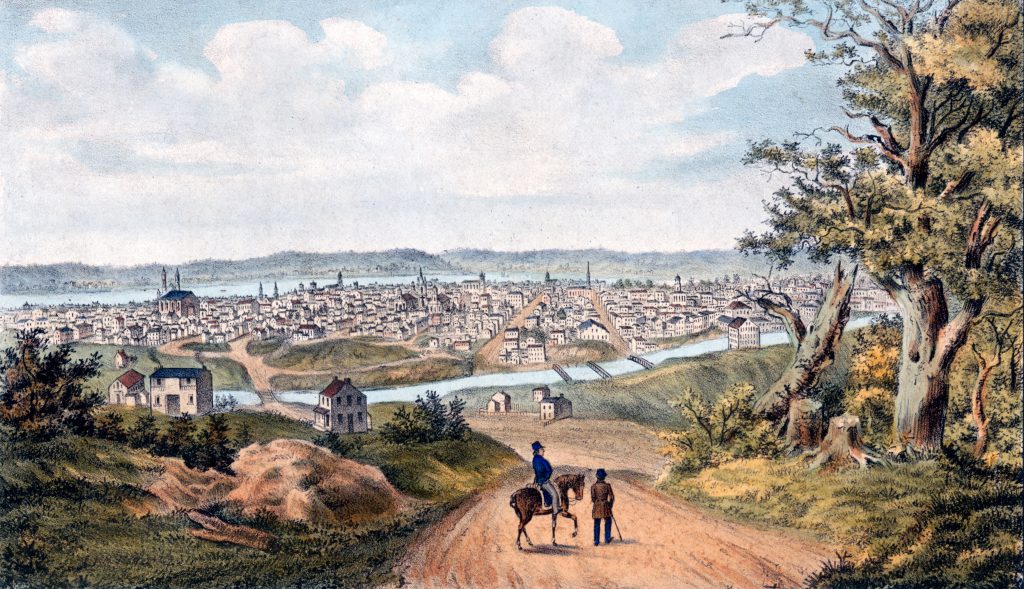

In the early 1800s, Buffalo New York and Cincinnati Ohio became centers of pork processing. Bacon and hams were smoked, and pork was salted and packed in barrels for storage and shipping. The earliest packers were merchants in frontier towns such as Chillicothe, Terre Haute, and Lafayette Indiana. As raising pigs for market became popular, farmers switched from the semi-wild razorback variety they had brought to the frontier, and began raising premium foreign breeds like the Suffolk, the Yorkshire, and the Poland China. Popular farm periodicals like The Prairie Farmer were filled with articles on the merits of different breeds and instructions on crossbreeding for improved results and hybrid vigor. Farmers became experts at calculating “the value of corn when sold in the form of pork,” which required them to know not only feeding yields and feed prices, but also to calculate transportation costs and risks, and to have some idea of the demand for their product in faraway markets. And as specialized processors built larger businesses in the cities, they needed access to capital.

The operating costs of a pork processor were high. Fixed costs of production were low, especially compared to eastern industries like textiles that required large factories and expensive machinery to operate. But a county pork processor might buy 6,000 hogs to pack in a season, which in the mid-1840s cost about $45,000. A city packer processing 15,000 hogs would need over $100,000 of cash or credit. Packing quickly became big business. By the 1830s America replaced Ireland as Europe’s source of cheap processed food. By the early 1840s, U.S. bacon and ham exports reached 166 million pounds. Shipments of processed pork were made easier by the growth of the rail network, but packers quickly realized that trains carrying barrels of salted pork could just as easily carry live animals. Railroads led to the concentration of packing in big cities such as Cincinnati, Louisville, Chicago, and St. Louis. But even in the 1850s, when Cincinnati was known as Porkopolis and processed over a quarter million hogs each year, the big cities only accounted for 40 percent of the business. By 1877, the Midwest was processing 2,543,120 hogs a year. Storage of ice for summer use allowed what had once been a seasonal business to continue year-round. With the rise of ice-packing, some pork processors moved back to smaller cities. The big city packers took advantage of refrigerated shipping to branch out into beef.

Beef on Ice

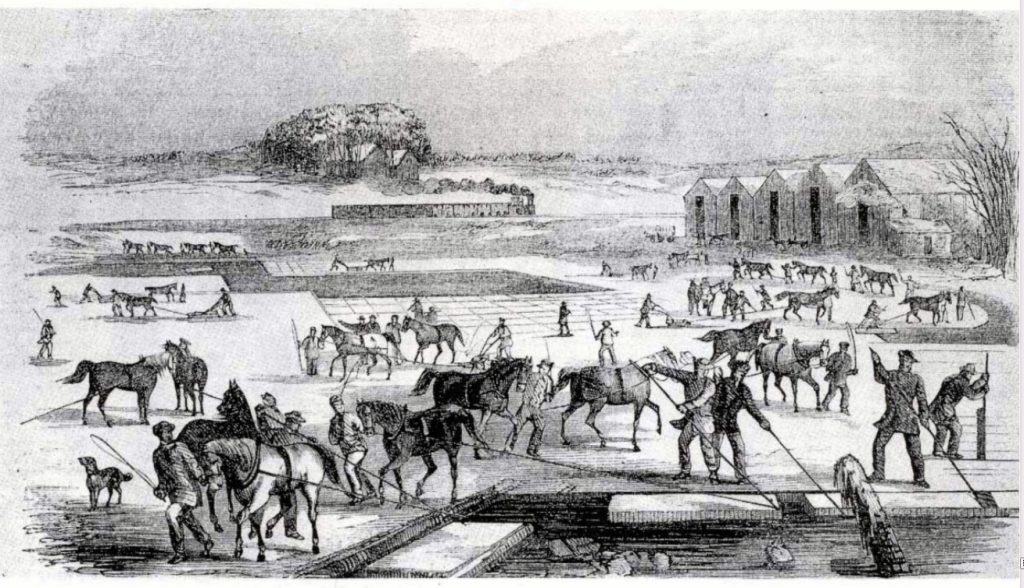

One of America’s forgotten industries that flourished during the nineteenth century was the ice business. Ice has been important throughout history, but in early America it was a luxury product costing hundreds of dollars per ton. Ice was traditionally cut from ponds or lakes in the winter, packed in sawdust, and stored in cellars or covered wells. In 1806, a 23-year old Harvard drop-out named Frederic Tudor bought a ship to carry a load of ice from his father’s farm in Saugus Massachusetts to the Caribbean island, Martinique. After successfully delivering Massachusetts ice to Martinique, Tudor convinced the governments of Cuba and several other islands to grant him a monopoly on ice imports. By 1833, Tudor was shipping ice to Calcutta, India. After a four-month journey half-way around the world, his ship’s cargo of 180 tons of New England ice had shrunk to only 100 tons, but Tudor still made a huge profit. Henry David Thoreau watched Tudor’s workers cutting ice on Walden Pond, and remarked in his journal, “The sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well.” By 1865, two out of three homes in the Boston area had an icebox.

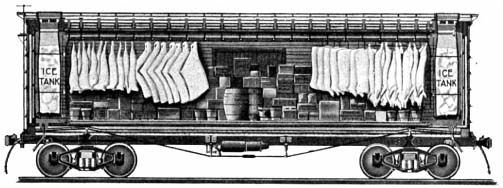

Like potash for soap and firewood for locomotive boilers, ice was something western settlers could quickly produce and sell for cash. Local entrepreneurs built icehouses near railroad lines and filled them from winter lakes. Midwestern pork packers like Gustavus Swift and Philip Armour saw an opportunity to expand their businesses. They were already shipping pork on ice, so why not ship chilled beef? Swift, Armour, and the other city packers contracted with icehouses along the rail lines, so their shipments could be kept reliably cold. Refrigerated rail cars first carried dressed beef from Chicago to Eastern cities in the late 1850s. But local butchers resisted this invasion of their market for many years, insisting that their freshly-killed local meat was tastier and safer. In 1878, Gustavus Swift developed the first practical ice-cooled refrigerated boxcar, or reefer. But adoption of the new technology was slow, and after ten years live cattle still outweighed dressed beef on the rails by four to one.

Because eastern butchers resisted the introduction of dressed beef and railroad companies did not want to risk losing the revenue they earned shipping live cattle, corporations like Swift and Armour built their own fleets of reefer cars. By 1900 the packers owned over fifty thousand refrigerated freight cars and the old local butchers were overwhelmed by their shipments of inexpensive chilled meat. A few years later, a new generation of city butchers was forced by the government to give up slaughtering animals altogether and to begin selling Chicago dressed beef.

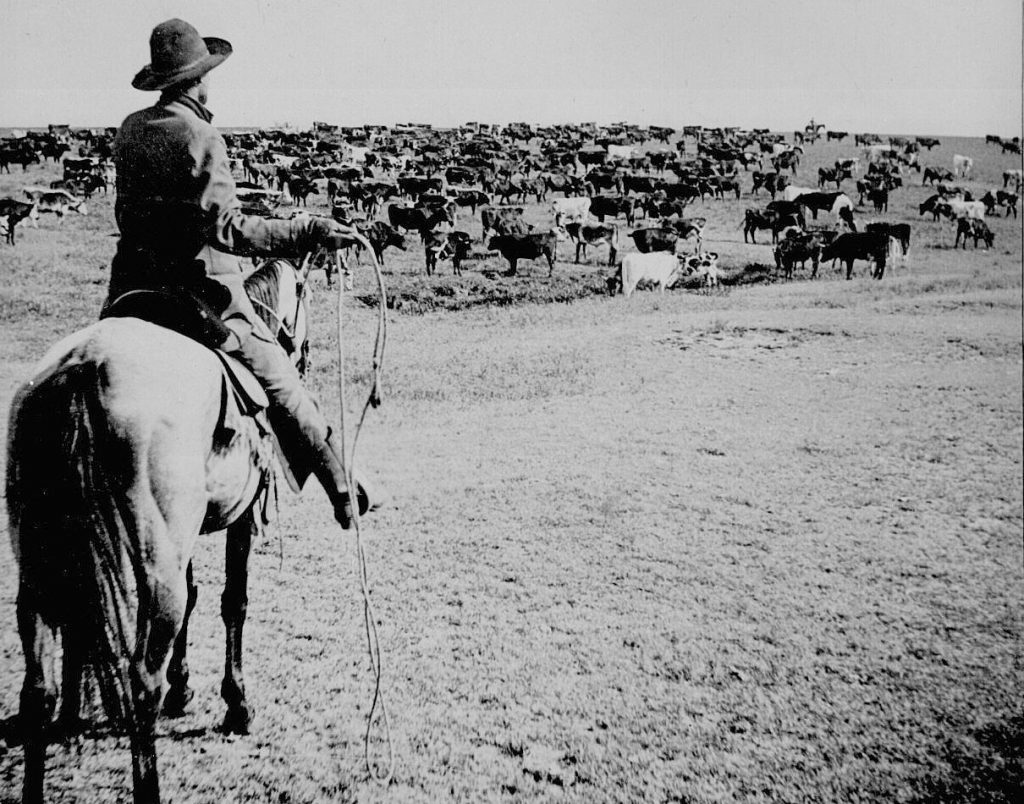

Unlike pork, beef spoils rapidly when it is not refrigerated. The earliest solution to this problem had been to ship live animals to market, where they would be slaughtered as needed and their meat processed for immediate sale by local butchers. Cattle-raising grew in the first half of the nineteenth century from something done on semi-arid rangelands in California and Texas that were no good for crops, to a mainstream activity for midwestern farmers. Cattle grow much more slowly than pigs. But they are ruminants, which means they can eat not only the surplus grains that farmers fed to pigs, but field grass, hay, straw, and silage left over after wheat and corn was harvested.

Like pigs, cattle had been on the frontier from the earliest days of Euro-American settlement. Milk cows were common on family farms and oxen (neutered bulls) were preferred over horses as draft animals, due to their strength and endurance. When either of these animals came to the end of its productive farm life, they were slaughtered and eaten.

In the city, of course, there was less room for a family milk-cow. Although it was actually common in many cities for poor people to keep pigs that foraged the neighborhoods, urban cattle required large amounts of hay and had to be looked after. Many city-dwellers relied on dairymen for their milk and on their local butchers to kill and process their steaks and roasts. Herds of cattle were often walked across the plains in long cattle drives to a railhead where they would be loaded onto freight cars for shipment to distant cities. These animals might walk hundreds of miles from their rangelands to the railhead, resulting in tremendous weight loss. After arriving at their destinations, the cattle would have to be finished: fed for a while to regain their weight. And when they were processed by a local butcher, up to 60% of the animals’ mass would still have to be discarded as inedible waste.

Chicago beef packers saw an opportunity. Finishing and processing live animals shipped to eastern cities added to beef’s cost. And local butchers often threw away parts of the carcass that could be rendered into marketable products, especially if they could be processed in large volume. But dressed beef was highly perishable and had to be sold quickly after processing. In spite of their fleets of reefer cars, corporations like Swift and Armour were often forced to sell dressed beef below its cost of production, in order to move the product before it went bad. The big meat packers turned this liability into an asset, buying the urban market with low prices and using the profits from other product lines to subsidize their losses. Prices for Chicago dressed beef were slashed to a level at which butchers could not match them with fresh meat. Eastern city customers naturally wanted the largest cut they could get for their dollar, and the Chicago packers made sure it was theirs. Gustavus Swift’s instructions to his salesmen were, “If you’re going to lose money, lose it. But don’t let ‘em nose you out.”

The Jungle

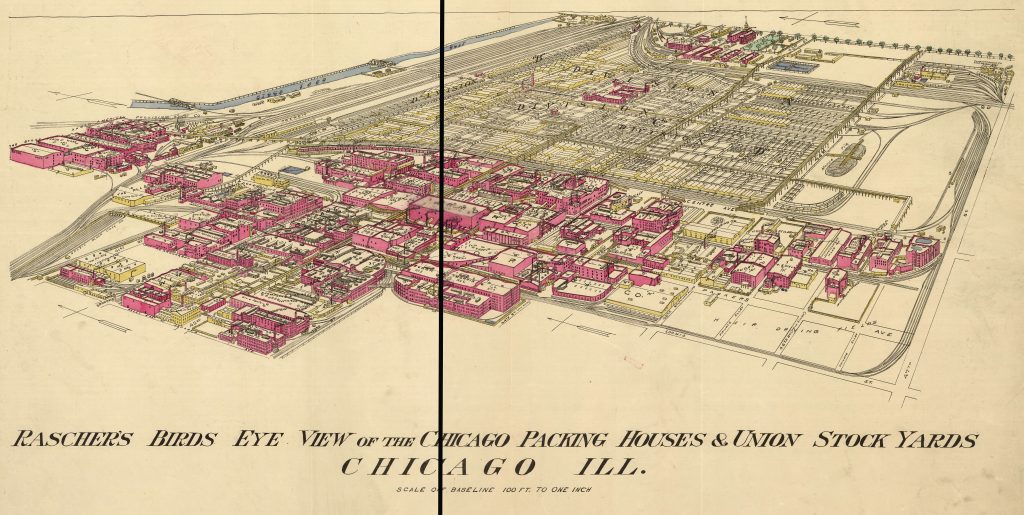

Chicago’s famous Union Stock Yards were opened in 1864, on 320 acres of swampy land southwest of the city. Animal pens were connected to the railroads with fifteen miles of track. The Yards processed two million animals in 1870, and by 1890 they were processing 9 million animals a year. By 1900, after an expansion, the 475-acre stockyard employed 25,000 people and produced over 80 percent of the meat sold in America. The Yards contained nearly 2,500 livestock pens that could house 75,000 hogs, 21,000 cattle, and 22,000 sheep at the same time. The Yards used 500,000 gallons of water daily and pumped the waste into the South Fork of the Chicago River in an area that quickly became known as Bubbly Creek. According to Chicago tradition, the creek still bubbles, nearly a hundred years later.

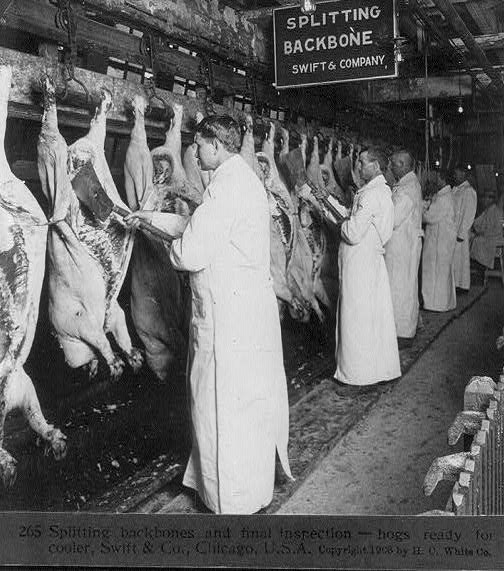

Growth of the Chicago meat packing industry was resisted by butchers, distrusted by consumers, and criticized by labor activists. Most Americans at the beginning of the twentieth century lived on farms or in small towns, and valued the face-to-face relationships that were still a big part of their commercial lives. And accounts of the Chicago meat packing industry were shocking. Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel, The Jungle, depicted the stockyards and packing plants as inhumane, unsanitary, and operated by corrupt businessmen who cut corners and victimized their immigrant workers. In a widely-read endorsement of The Jungle, famous author Jack London called the book “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of wage slavery.”

Although President Theodore Roosevelt was suspicious of Sinclair and considered him a dangerous socialist, he commissioned an investigation that quickly confirmed Sinclair’s sensational claims. The government report led directly to the Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906, designed to ensure that meat products used as food were processed under sanitary conditions and were correctly labeled. This type of regulation had never been needed when Americans slaughtered and processed their own farm animals or bought their meat from local butchers who they knew and trusted.

Small local companies lived and died by their reputations in a way that large, remote corporations did not. Government regulation was considered crucial to enforcing safety and quality controls in the stockyards and packing plants of Chicago because it was impossible for consumers to make corporations accountable the way they could their local butcher. What had once been a face-to-face, personal interaction between a merchant and the small community he was a part of had become a faceless transaction in a national market. The personal accountability that was part of face-to-face local commerce disappeared. Consumers were scattered and hard to organize, while producers were few and powerful. Ironically, although businessmen like Swift and Armour may initially have been offended by what they considered government intrusion into their operations, regulation may have actually saved their businesses by creating consumer trust in their processed meats, especially after people had read The Jungle.

The Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act that followed it in 1906 made State Governments accountable for inspecting meat sold inside their borders, and made the Federal Government responsible for meat sold across state borders or exported. The USDA also provided meat grading (Prime, Choice, and Select) as an optional service for a fee. But health and safety inspections were mandatory and were paid for by the government.

Although meat packers such as Armour and Swift may not have welcomed inspectors, corporations actually received a valuable government service at taxpayer expense. USDA inspections cost the meat packers nothing, calmed the suspicions of consumers, and restored trust in the corporate brands. Local butchers, who had never needed government inspectors to convince customers that their shops were clean or their meat safe, found themselves at an extreme disadvantage after government inspectors began stamping sides of Chicago beef with dye stamps declaring the meat wholesome. When the new laws went a step further and declared butchers could not sell uninspected meat at all, and there were not enough USDA inspectors to visit every local slaughterhouse and butcher shop and certify them, local operators were forced to resell Chicago-packed meat or go of business. Criticized for interfering in free enterprise with their mandatory inspections, the government had actually wiped out the Chicago meat industry’s competition through regulation.

There are still a few local meat processors scattered about the Midwest to this day. We call them lockers, and they exist because some farmers still raise a few animals for their own family use, and because Midwesterners hunt deer. Lockers and their customers are not allowed to sell meat without USDA inspection, although a few of the larger lockers are beginning to offer inspection services to livestock producers who want to sell their meat to local customers. Lockers are also allowed to process uninspected carcasses for a fee, which has traditionally been their main business. Every package of meat cut for home use at a locker must be marked with a stamp reading “NFS”, Not for Sale.

As a result of USDA regulations implemented a century ago, it is very difficult for local entrepreneurs to return to the business model of the pre-Jungle era, when customers knew their merchants and producers lived and died by their personal integrity and the quality of their products. Locavores and libertarians such as Virginia farmer-author Joel Salatin have criticized today’s regulatory regime, claiming it unfairly protects global food corporations from competition by small producers. Critics of the current system suggest the global concentration of meat processing has gone too far, but the trend shows no signs of stopping. America’s largest pork packer, Smithfield Foods, was recently purchased by the Shuanghui Group of China for nearly $5 billion. And criticism of the wasteful and inhumane nature of modern corporate food processing is at least as intense as it was when Sinclair wrote The Jungle, as we will see in Chapter Eleven.

In addition to processing rural foods for national markets, urban industries depended on raw materials from their hinterlands. Eastern cites grew around industries like the textile mills along the Merrimack River, processing cotton from Southern plantations. Western cities surrounded by undeveloped country became conduits for the natural resources of the frontier. In addition to meat-packing, Chicago became a center of the lumber industry.

Cutting trees in frontier forests was traditionally a winter activity, beginning each November after the harvest. Winter logging camps filled with Midwestern farmers or their sons, eager to supplement the season’s farm produce with some cash earnings. Another reason logging was a winter activity was because it was difficult to get white pine out of the woods at any other time. Pine forests were often boggy, and sixteen-foot sections of tree trunk were easier to slide over frozen roads. Lumbermen stacked the logs on horse-drawn sleds they drove over iced logging trails. Logs were then piled beside frozen streams throughout the winter, waiting for the spring snow-melt that would carry the timber downstream to a lake. Most of the timber that made its way to Chicago was floated across Lake Michigan. Timber came from Michigan, Wisconsin, and as far away as Minnesota. In 1879, The Lumberman magazine reported that “There is not today a navigable creek in the state of Michigan or Wisconsin [or] Minnesota, upon whose banks, to the head waters, the better grade of timber is still standing within a distance of two to three miles.”

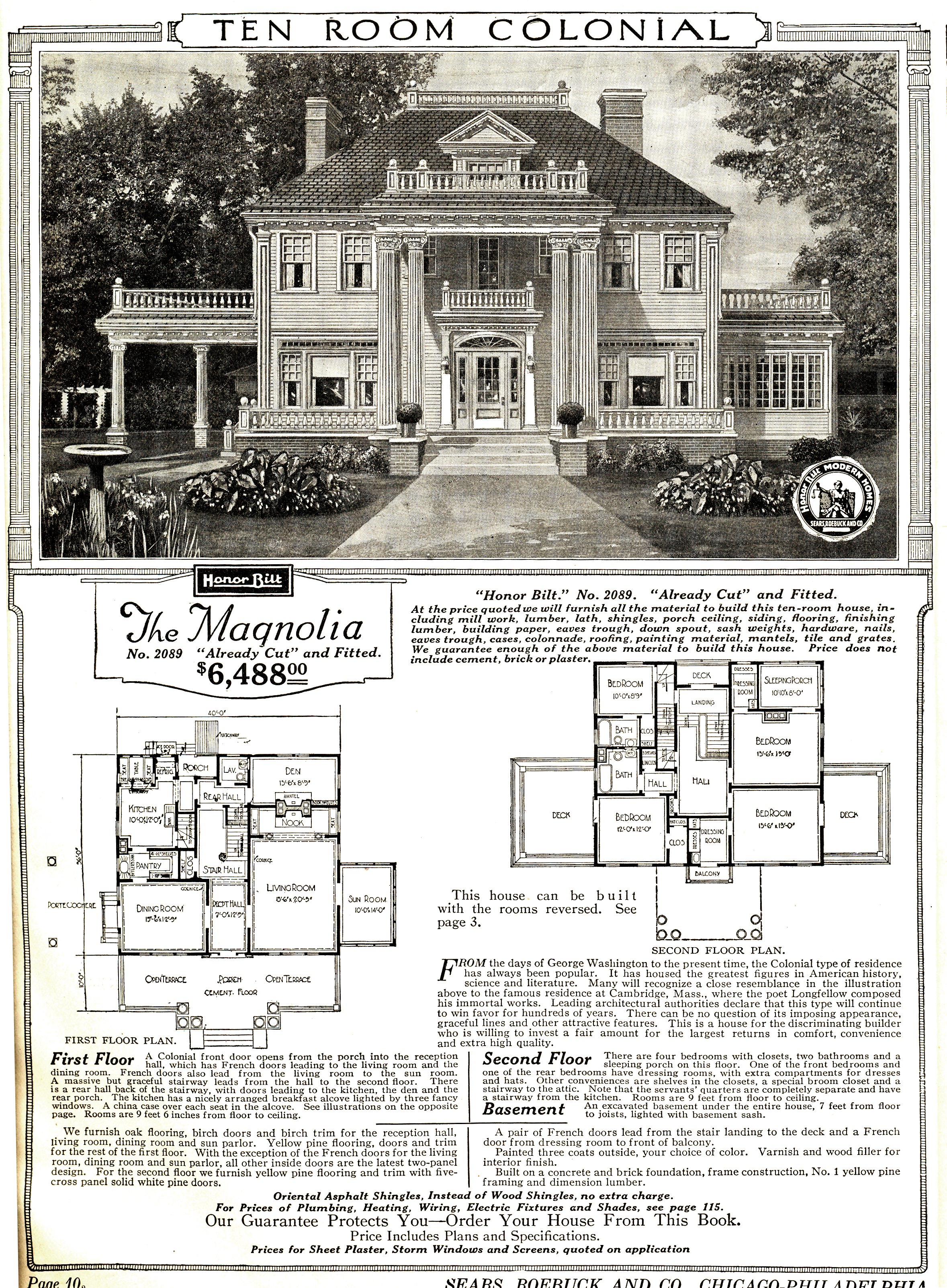

One of the major markets for Midwestern lumber processed in Chicago was house-building. Dimensional softwood lumber of the kind we are familiar with today made a new style of construction possible. Hardwood-framed, post and beam construction required special skills. A new technique called balloon-framing allowed houses to be built by relatively unskilled carpenters. Early American houses had been built of local hardwoods and had often been constructed in community efforts like the barn-raisings still held in traditionalist communities. Balloon houses were so easy to build that shoppers could buy them from mail order catalogs. In 1908, Chicago-based Sears Roebuck Company published its first Book of Modern Homes and Building Plans, which included 44 designs ranging in price from $360 to $2,890. Sears rail-shipped more than 70,000 catalog home kits between 1908 and 1940, in 370 designs. The ready-to-build kits included everything but concrete and bricks for their foundations. Competing regional and national companies sprang up, and the balloon construction style quickly became universal among American house-builders.

Lumber production in the Great Lakes region peaked in the early 1890s and then fell sharply when the industry moved to the Pacific Northwest. The cut-over area covered several states, and the forest was usually clear cut. While removal of the Midwest’s forests created potential new farmlands, the debris left by the cut-over first needed to be cleared. Clearing the branches and debris left when pine forests were cut was often accomplished with fire, leading to some of the worst forest fires in American history. But sometimes the environmental impact on remote, resource-producing hinterlands is harder to see than the growth and profit being generated in the processing cities. Contemporary media and history often celebrate the achievements of innovators and entrepreneurs in the centers, without counting the costs to environments, communities, and people on the peripheries. Our failure to charge these peripheral costs against the profits created at the center happens so frequently that, as mentioned in earlier chapters, economists have coined the term externality to describe it.

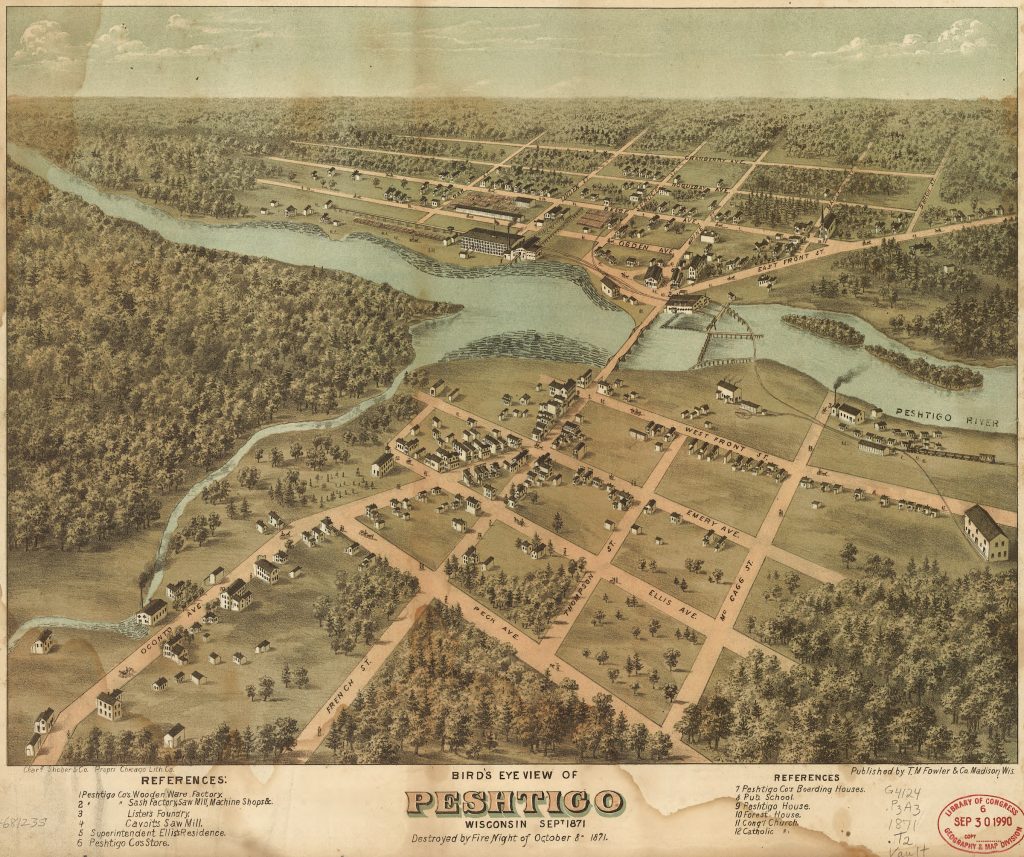

For example, while the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 made national news, a much larger blaze that had completely destroyed Peshtigo Wisconsin two days earlier did not. The Peshtigo fire, a direct result of the cut-over, killed 1,500 people in the town of only 1,700, or five times the number who died a couple of days later in Chicago. But unlike Chicago’s fire, the Peshtigo disaster was largely ignored at the time and has been virtually forgotten by historians outside Wisconsin.

Similar disasters in the cut-over region included the Great Michigan Fire of 1881, when over a million acres burned, the Hinckley Minnesota fire of 1894, and the Cloquet Minnesota fire of 1918. The deaths and destruction caused by these fires were tangible costs of Chicago’s lumber industry. But they were faraway and external to the calculation of Chicago lumber corporations’ profits. The fires were a cost of doing business, but the cost was socialized while the profits were privatized. In a final irony, to the disappointment of would-be farmers, the boosters who advertised the cut-over as a promising new agricultural region were wrong. Cut-over pine-forest soils turned out to be thin and easily eroded in floods that became more frequent once there were no live tree roots left to hold the soil and absorb rainfall.

The Mill City

Chicago was not the only Midwestern city that depended on resource-rich hinterlands for its growth. During the early decades of American history, as we have seen, farmers grew wheat for home use and milled it at local grist mills. Surplus flour was packed in barrels by merchant millers and shipped to eastern markets. But as railroads made western farmlands more accessible, urban merchants built mills of their own and began buying unprocessed grain directly from farmers.

The creation of global markets, the building of national consumer brands, and the reduction of the farmer to a mere raw material supplier all happened simultaneously in the flour-milling business. Chicago was one center of this consolidation. Another was Minneapolis, home of the familiar brands Pillsbury and General Mills, whose Gold Medal Flour can still be seen on supermarket shelves across America.

When farmers milled their grain locally and sold it close to home, people were able to buy flour from producers they trusted. The quality of the farmer’s wheat and the care the miller took processing it into flour mattered. Even factors such as a farmer’s reputation in the community or whether he paid his debts on time could influence a customer’s buying decisions. Consumers bought from people they trusted, and often from people with whom they had long-term relationships. Farmers were also able to take advantage of long-term local relationships when it was time to sell their harvests. Producers had a bit more leverage, when they could negotiate with their miller and their customers face to face.

Personal accountability and face-to-face relationships were swept away when farmers began carting their grain to elevators by the railroad for shipment to big-city flour mills. The bulk elevator was an innovation developed in another mill city, Buffalo, in the late 1820s after the opening of the Erie Canal. Elevators allowed large quantities of grain to be handled rapidly and stored together. Wheat might still be hauled to the elevator by individual producers in bags with the farmer’s name on it. But as soon as it was unloaded the grain went into bulk storage bins where it was mixed with everyone else’s grain. A particular farmer’s special attention to his fields, or to timing his harvest and drying and threshing his grain carefully, was lost along with his identity. Everyone’s grain went into the same railroad cars and when the trains arrived in Minneapolis, it did not even really matter where they had come from. Trains from all across the Midwest converged on Minneapolis because its millers had developed a new technology called the rolling mill, and in the final decades of the nineteenth century the Mill City became the world leader in flour production.

When Minnesota became the 32nd state in 1858, the population of Minneapolis had been only about five thousand. The town had grown up around the Falls of St. Anthony, where the power of the first major waterfall on the Mississippi River was used to saw lumber and grind flour. By 1870, there were about 13,000 people in the growing city and large-scale flour mills had taken over the river in much the same way textile corporations had taken over eastern rivers. Twenty years later, when the flour-milling industry reached its peak, Minneapolis had grown to over 165,000 and the Mississippi was lined with corporate mills, connected by a dedicated Stone Arch railroad bridge crossing the river between them.

Grain production surged as farmers devoted more acres to easy-to-sell cash crops. As supply increased, the price farmers received at the elevator for a bushel of wheat fell from $1.06 in 1870 to 63¢ in 1897, and corn dropped from 43¢ to 30¢. Farmers understood they were overproducing, but they also believed the game was rigged against them. Countless small farmers sold their grain to a few big corporations, and the farmers paid higher freight rates than the railroads charged their favored corporate customers.

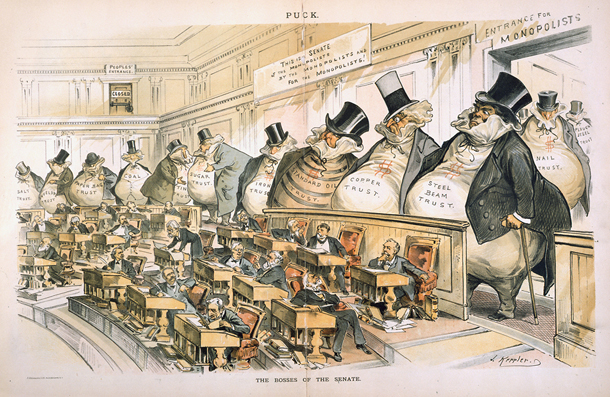

To make matters worse, when farmers entered the market to buy equipment, they once again felt they were on the wrong end of a system that pitted wealthy city corporations against powerless rural folk. In 1902 Wall Street financier J. P. Morgan merged the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, the Deering Harvester Company, and three smaller farm machine companies into the International Harvester corporation. After the biggest merger of its time, the farm equipment market consisted of 29 million farmers (38 percent of the American population), but only one $120 million corporation they could buy harvesters from.

Economic imbalance between corporations in the center and farmers at the periphery led to political mobilization. Farmers joined groups like the National Grange, began cooperatives to sell their produce and to buy equipment and supplies, and helped create the Populist political movement. The People’s Party never won a Presidential election, although their candidate, William Jennings Bryan, served as Secretary of State to Woodrow Wilson. But they elected several Midwestern Governors and dozens of Congressmen. Populists were key to the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act and to its application against monopolies. In 1914, following the breakup of Standard Oil, International Harvester became the next target of an antitrust suit (it survived).

The pattern of urban processing centers depending on resource-producing hinterlands repeated as Americans moved westward. This was not the only way growth could have occurred in America. It was the result of legal, political, and cultural choices. Enabled by transportation and encouraged by demand from urban consumers, products such as meat, lumber, and flour that had once been produced locally and used by customers who knew the producers, became standardized commodities in national markets. As these markets expanded, large corporations benefitted from their access to capital and their ability to create national brands like Sears Modern Homes, Swift Premium Bacon, and Gold Medal Flour. But another, sometimes hidden factor in this change was the government’s role in subsidizing these central processors by ensuring product safety and establishing standards of quality. And the effectiveness of concentrated economic power when it is pitted against small, scattered and often disorganized opponents should not be underestimated.

Recognizing how quickly America changed from a society of farmers and small-town people doing business with neighbors, to an impersonal national and ultimately global market where billions of consumers buy from a few immense corporations is crucial to understanding the present. The centers are now global, and the periphery now includes most Americans. New technology and new markets helped the American West grow, and led to our society of prefabricated homes and processed foods. But in the long run, the centers accumulated more economic and political power than the periphery. City corporations gained the upper hand, partly by business and technical innovation, but partly by ignoring external costs at the periphery and by taking advantage of government subsidies. That is, economic and political power have helped some people benefit more than others from this change. The point is not that change should not have happened, but that if we understand what actually happened, we may be better equipped to consider where we go from here.

https://youtu.be/h5ybzgwUlhg

Further Reading:

William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. 1991.

Charles Postel, The Populist Vision. 2007.

Joel Salatin, Folks, This Ain’t Normal: A Farmer’s Advice for Happier Hens, Healthier People, and a Better World. 2011.

Upton Sinclair, The Jungle. 1906.

Media Attributions

- 3c06375u © Harper's Weekly is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cincinnati-in-1841 © Klauprech and Menzel is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 03169v © Ehrgott & Krebs Lith. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ice_Harvesting,_Massachusetts,_early_1850s © Gleason's Drawing Room Companion is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Early_refrigerator_car_design_circa_1870 © Lordkinbote is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cowboy1902 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Birdseye_View_of_Union_Stock_Yards_by_Rasher,_1890 © Charles Rascher is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Chicago_meat_inspection_swift_co_1906 © H. C. White Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Livestock_chicago_1947 © John Vachon is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 4a23065v © Detroit Publishing Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sears_Magnolia_Catalog_Image © Sears Modern Homes is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sears_Magnolia_in_Benson,_North_Carolina © Rosemary Thornton is licensed under a Public Domain license

- pm010495 © T.M. Fowler & Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- MillsDistrict-MPLS-1895 © Frank Pezolt is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 38_00392 © Joseph Keppler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gold_medal_flour_factory © Angela is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license