11 Farmers and Agribusiness

In early America, just about everyone was a farmer. Everybody must eat, and in a time before transportation, refrigeration, and foods manufactured for long-term storage, that meant everybody was responsible for making food to put on their tables. Some people such as pre-Columbian Indians in the far north survived on hunting alone, and it is still possible to survive as a hunter today. But only if population density is so low the hunter community does not overwhelm the available game. Throughout America’s history, population growth has only been possible on a strong foundation of dependable food. That means farms.

As we have seen in previous chapters, the growth of American industry and cities depended on availability of foods produced by commercial farmers and on transportation networks able to get them to consumers. Let’s review population growth in the United States, paying close attention to American farmers. In the first U.S. Census of 1790, the new nation’s population was about four million people, almost all of them living in the countryside or in small towns and villages, and 90 percent of them listing their occupation as farmers. Actually, the other ten percent often farmed quite a bit too. Rural professionals such as doctors, lawyers, ministers, and merchants pastured horses and put up hay for their winter fodder, kept milk cows, and raised a few chickens or a hog for the table. Very few people had absolutely no connection with food production. Even sailors kept chickens for eggs and meat on long ocean voyages.

In the 1820 Census, Americans discovered the population of the United States had more than doubled to 9.6 million people, of whom 1.5 million were slaves. There were 61 towns and cities with more than 2,500 people, and nearly 9 million people, or 93 percent of the population, lived outside cities. Agricultural exports were about $42 million per year, amounting to about two thirds of total exports.

By 1840, when industry was accelerating in the Northeast and cities were beginning to expand rapidly, America’s population was just over 17 million. More than 9 million people were farmers, or about 69 percent of the total labor force. About 2.5 million slaves were recorded in the census, and in states like South Carolina enslaved people outnumbered free whites. Only ten percent of Americans lived in cities, and there were only 131 places in the country with more than 2,500 inhabitants. Most people living in small towns and villages still raised animals to eat and cut hay to feed their horses, even if the census recorded a different occupation. Of the people listed as farmers, many still grew crops primarily to feed their own families, and sold the excess in local markets. But some commercial farmers, like the Ranneys of Michigan and Upstate New York discussed in Chapter Four, regularly shipped agricultural products to distant markets for sale.

In 1880, America’s population passed the fifty million mark. 23 million Americans were farmers, and although the number of farmers was still growing, the farm population was growing slower than the non-farm population and for the first time less than half of working Americans were farmers. Three in ten Americans lived in urban settings. Some were farmers or the children of farmers who had had moved off the land; others were immigrants who settled in cities as soon as they arrives. There were nearly a thousand towns and cities with populations over 2,500. The largest cities, like New York and Philadelphia, held over a million people, and Chicago had a half million. There were about 4 million farms, and the average farm size was 134 acres. Farmers were becoming aware that they were numerous enough to be politically powerful, and were beginning to understand that their concerns were not the same as those of working people in the cities. They began organizing in groups like the Grange and the People’s Party to lobby for rural issues.

The American population in 1900 was over seventy-five million, and the number of farms and of farmers was still growing, although by the beginning of the twentieth century farmers only made up about a third of the U.S. workforce. 29 million people lived on about 5.75 million farms, and the average farm covered 147 acres. About a quarter of these farmers were former slaves and their descendants living in the South. 90% of America’s 8.8 million African American citizens lived in the rural South, although some were beginning to migrate to Northern cities in search of jobs and an escape from oppressive Jim Crow laws. Four out of ten Americans lived in nearly 2000 large towns and cities, and the nation’s commercial farmers were responsible for feeding them. Corn and wheat fields got larger and were planted year after year instead of being rotated into pasture. Commercial fertilizers and tractors became indispensable to maintaining a high level of agricultural productivity.

By 1920, America’s population had grown to over a hundred million people through both natural increase and immigration. U.S. borders remained largely open to immigrants until the early 1920s, when laws were passed to slow the flood of Europeans and Asians seeking a better life in the “land of opportunity.” In spite of coming from the countryside, many immigrants settled in cities and found work in industry. Although urban employment was growing more rapidly than rural and farmers made up just a quarter of the U.S. labor force, the number of American farms and farmers was still rising. Over 31 million people lived on 6.5 million farms, and another twenty million country people lived close to the land and were part of the rural economy. But for the first time, more than half of Americans lived in large towns and cities. Most of the city dwellers were completely dependent on foods raised by farmers they had never met, processed and distributed by large corporations in distant cities.

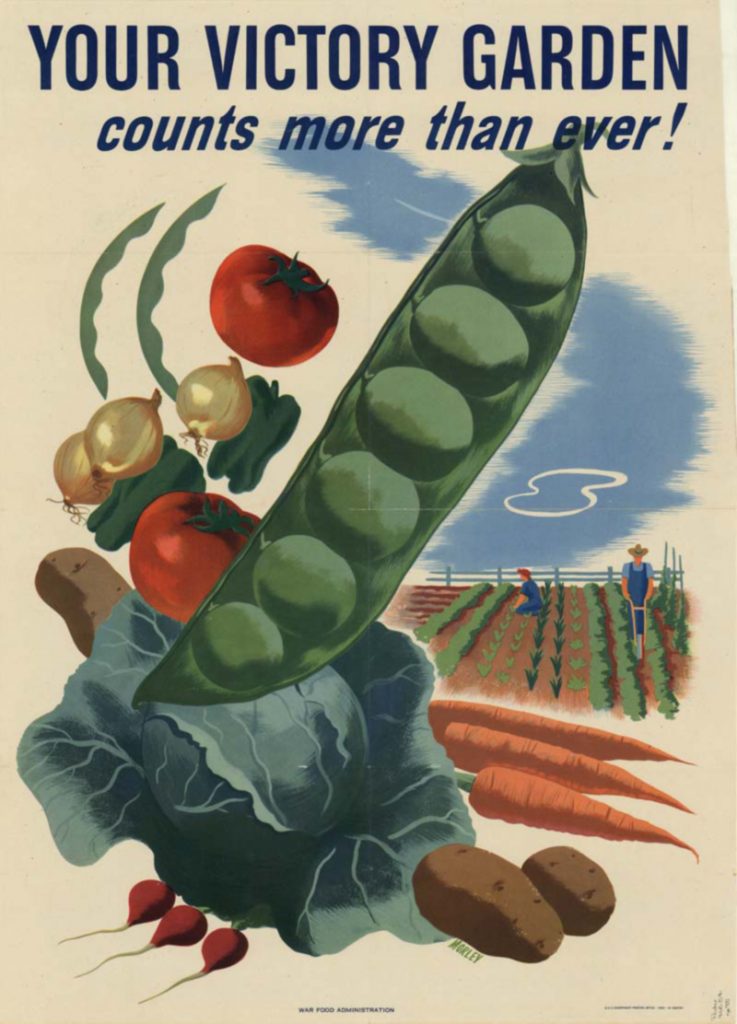

Many urban people regained a connection with the land when food rationing during the two World Wars and scarcity during the Great Depression caused the widespread planting of Victory Gardens and the keeping of backyard chickens. City people who had grown up on farms or emigrated from agricultural areas reconnected with their rural roots and took more responsibility for feeding their families. During these crises the government toned down its traditional support of the food processing industry and encouraged self-sufficiency, telling citizens that by feeding themselves they were helping the war effort. Unlike many European nations, the U.S. had never depended on food sources outside its own borders, but the wars and the Great Depression introduced many Americans to the concept of food security.

In 1950, at the start of America’s post-war boom, U.S. population was about 150 million and the farm population had finally begun to decline. 25 million farmers made up only one eighth of the work force, and over a million farms had disappeared since the previous census. Many had been swallowed by the Depression or erased by the Dust Bowl. However, the size of the average farm grew to 216 acres, because much of the cropland from failed family farms was consolidated into larger commercial operations able to take advantage of expensive new equipment. Industries that had built tanks and explosives during World War II were converted to civilian production, which meant larger tractors and combines, and more nitrate fertilizer. At the end of World War II, the U.S. military was supported by ten large munitions factories with an annual capacity of 1.6 million tons of ammonia. This capacity was turned over to fertilizer production, flooding the market with low-cost nitrate fertilizers that produced a boom in staple crops. A population that had faced high prices and food shortages for nearly two decades suddenly had disposable income and access to nearly unlimited, inexpensive food products.

By 1980, U.S. population exceeded 225 million and early three out of four Americans lived in large towns and cities. The farm population had fallen to just 6 million. Farmers now made up only 3.4 percent of the U.S. work force, and although there were still 2.5 million farms, their average size had ballooned to 426 acres. This was the era of the Farm Crisis, when Americans became aware that debt-strangled family farms were being forced into foreclosure at alarming rates. Saving the Family Farm became a political slogan, but even for those farms that survived, the nature of farming was changing dramatically. Unlike the self-sufficient small businesses of the early twentieth century, the new farms depended on extremely expensive capital equipment, high debt, and often on cheap, transient labor. Whether officially owned by corporations or families, most modern farms are controlled by the food-products manufacturers whose supply-chains they feed. Often the farmer’s single customer is also his banker and the mortgage-holder on his equipment and buildings. Many farmers only raise the crops and animals they’re instructed to raise by their corporate customers, and depend as heavily on the supermarket for their own food needs as any city-dweller.

According to the most recent information available, there are currently about 2.2 million farms in the U.S. Since 1980, the number of farms over 2000 acres has increased by nearly 25 percent, and the number of farms smaller than 50 acres has increased by about a third. A few of these smaller farms are part-time or “hobby” farms. But most are feedlots or concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), that are allowed to house 10,000 hogs or 125,000 chickens on a ten-acre parcel under most state guidelines. The number of traditional farms, between 50 and 2000 acres, has decreased by about 25 percent. And the number of corporate-owned farms has doubled.

Technology, transportation, and markets encouraged the growth and specialization of American farms. But another, often ignored influence on the American farm sector has been government agricultural policy. The United States Department of Agriculture began in 1839 as a department of the Patent Office, charged with compiling statistical data on American farming. Abraham Lincoln established an independent Department of Agriculture (because most Americans were farmers, Lincoln nick-named it the “people’s department”) in 1862. During the Progressive Era, the department opened agricultural experiment stations and extension agencies to promote scientific farming and improve country life. The federal government became much more actively involved in the American economy and agriculture during the Great Depression. The market crash of 1929 plunged the United States into a prolonged economic crisis and was perceived by many as evidence the free market could not avoid boom-and-bust swings. Just under half of Americans lived outside cities at the beginning of the Depression, so Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal included rural development and “agricultural adjustment” farm policies that became part of the American political landscape.

Farmers had been complaining since the nineteenth century that they were treated unfairly by the railroads and corporate food processors. Railroads were granted monopolies by the government, the farmers argued, and food processors were supported by USDA safety inspections. Farms were many and small; the corporations on the other side of the bargaining table were few and large. It was only fair, farmers argued, that a government that had stacked the deck in favor of big corporations should do something to protect the farmer. During the New Deal, the government finally threw its support behind the farmers, instituting crop-reduction programs that paid farmers to set land aside and limit the volume of crops reaching the market. Crop reduction stabilized prices, but resulted in higher food costs for consumers. Critics of the program argued that paying people not to produce something is absurd. But what makes sense and what is politically expedient are not always the same. The program was supported by rural constituencies and their representatives, and survived until the late 1970s, when political changes in Washington eliminated the New Deal price-stabilization and farmers were encouraged to plant “fence-row to fence-row.” Following the supply-side economics that became politically fashionable in the 1980s, the USDA’s official policy became “Get big or get out,” and farm programs were rearranged to incentivize the greatest possible production.

Of course, when supply explodes without an equally rapid increase in demand, prices plummet. When all the excess grain could not be absorbed in the export market, the free-market-oriented politicians who had criticized the absurdity of paying people to not produce crops instead found themselves setting price floors. The government began paying farmers more than the market would bear, to produce crops the market didn’t want. Direct Payments from the USDA made it possible for farmers to plant more corn than the market would buy, sell it below their cost of production, and then collect the rest of the floor price from the government. Like crop reduction, the program made no sense; it was a political compromise. But it helps explain why the government became so interested in turning corn into fuel. Ethanol production increases demand for corn, according to USDA economists, resulting in savings of over $6 billion in annual farm subsidies. While it is unclear whether that savings is offset by other subsidies elsewhere, or whether it is in the United States’ best interest to continue producing so much corn, reducing subsidies is probably a good thing. USDA direct payments to farmers between 1995 and 2012 totaled $292.5 billion. Subsidies attracted a lot of attention, but the number is more meaningful with context. Although USDA Direct Payments to farmers are high, two thirds of American farmers receive no subsidies at all, while the top 10 percent receive 75 percent of the money. Corn receives the most government support, nearly three times more than wheat, the next largest recipient. In the early years of the twenty-first century, food processors and manufacturers discovered they could buy corn for less than it cost to grow, which changed agriculture and the American diet in ways no one had anticipated.

High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is a chemical sweetener developed by Japanese industrial chemists in the late 1960s. Because the US maintains a high tariff on foreign sugar that makes domestic table sugar two to three times more expensive than sugar in the rest of the world, and because of USDA corn subsidies, HFCS is the cheapest sweetener available to American food manufacturers. It can be found in nearly all processed foods, even those that are not considered particularly sweet. U.S. government actions like sugar tariffs and the corn subsidy have contributed to making manufactured foods cheaper than most fresh foods. It is now possible to buy about five times more calories of processed food than of fresh food per dollar, in the average supermarket. That means from a purely economic perspective, a family on a tight budget trying to buy the most calories they can per dollar is much better off eating processed foods rather than fresh. Because of government farm policies, American families are actually better off financially if they never eat fresh foods. Another way of expressing this is that over the last generation, American family food spending as a percentage of income has dropped from 18% to 9%, while family health care costs over the same period have increased from 9% to 18%.

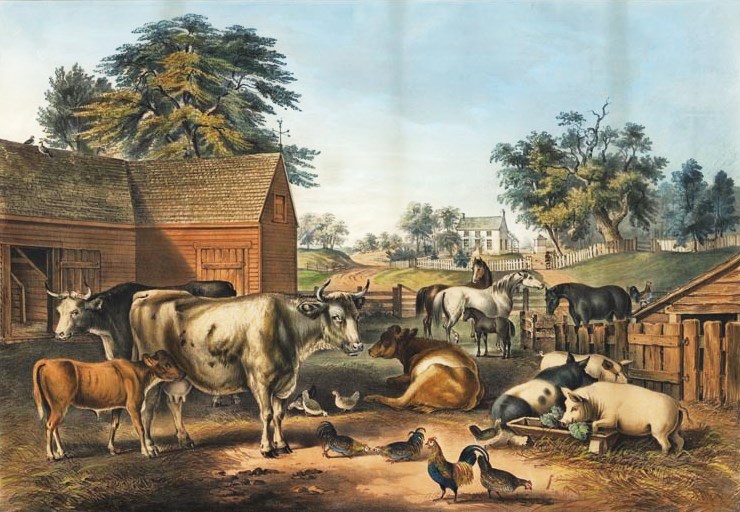

The way government policies have changed farms has a direct impact on the food choices available to American families. Due to the subsidy provided by USDA Direct Payments, it costs less to buy corn than it does to grow it. That means it makes economic sense for farmers who feed corn to animals not to grow the corn themselves. This has resulted in animal production being moved off the old-fashioned mixed-production farms that were once thought of as the backbone of America, onto concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). On traditional mixed-production farms, livestock were usually raised on pastures, often in a rotation with crops. Forage crops and the animals’ manure helped the land recover from staple crops like corn that mined soil fertility. The animals ate the grasses they had evolved to eat and contributed to the fertility cycle of the farm. The barnyard full of animals pictured in the Currier and Ives print earlier still represents the type of farm most people imagine when they think of American agriculture, and this was normal until the last couple of decades. Nowadays, trying to make a living in farming means obeying not only the orders of corporate customers, but the government’s incentives. Grain farmers specialize in a single high-yield crop, and animals are off the farm.

In concentrated animal feeding operations, animals are fed corn because corn is the universal low cost feed. CAFOs always use corn, whether they’re feeding chickens, turkeys, hogs, dairy cows or beef. But cattle, like goats and sheep, are ruminants. Grazing animals whose digestive systems evolved to ferment the cellulose in grasses do not thrive on a high-starch diet of corn. Feeding cattle a diet of corn results in chronic digestive diseases that must be continually treated with antibiotics. Introduction of permanent antibiotics into animal feeds over the last few decades has resulted in the evolution of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. And manure produced by millions of confined, medicated animals cannot be used as fertilizer without releasing those antibiotics into the ground-water and the ecosystems it supports.

Manure is no small problem in CAFOs. The hog-confinement operations of North Carolina alone produce twenty million tons of waste per year. In comparison, the cities of New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles combined do not produce as much human waste. And the waste produced by people in cities is heavily regulated, with specific requirements for treatment and safe handling. This is not the case with animal waste. But North Carolina, with just under ten million confined animals, is not even the largest hog state. Iowa has nearly eighteen million hogs, and Minnesota has nearly eight million. The top ten hog states house over 52 million animals in CAFOs. America’s hogs produce more waste than the nation’s entire human population. And then there are the confined flocks of laying hens and meat chickens, the turkeys, and the separate populations of dairy and beef cattle. When these animals lived on farms, their manure was an important source of soil fertility. On CAFOs manure is toxic waste, and the farms make up for its loss by spraying more synthetic ammonia produced using the high-energy Haber-Bosch process. As we have already seen, much of this fertilizer finds its way into America’s lakes, rivers, and the Gulf of Mexico.

But medicated cattle and hog manure are not the only issues facing agribusiness. Another element of modern farming that has undergone dramatic change that often goes unnoticed is the livestock itself. Most people are familiar with the efforts of corporations such as Monsanto, Syngenta, and Dow to produce genetically modified GMO crops and the determination of organic advocates to ban them. But even many organic enthusiasts seem unaware of the changes that have been made to the animals that become the meats they eat. We’ll focus here on the history and current condition of chickens, because I have some personal experience raising them. But the same pattern of increasing production concentration and specialization of the animals themselves can be seen in the commercial turkey, pork, and beef industries.

Go to your local food coop’s freezer and pick up the most expensive free-range, organic, vegetarian-fed broiler chicken you find. I can almost guarantee you it is a Cornish Rock hybrid, a specialized crossbreed designed for rapid growth, short legs, and lots of white meat. Unlike the hybrid broiler’s ancestors, this chicken can only live about nine weeks before it develops heart disease and its legs break under its own weight. The hybrid broiler cannot even reproduce naturally.

Chickens were domesticated in Asia about ten thousand years ago, from two related species of red and grey jungle fowl. They spread throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa, and reached the Americas along with other Eurasian livestock as part of the Columbian Exchange. Unlike most wild birds that only lay eggs during a short mating season, chickens have been bred to lay year-round. Chickens served a dual purpose on traditional farms as a source of both eggs and meat. Until recently, the same birds were usually used for eggs and meat, although many cultures have also bred specialized chickens for show or for cock-fighting. In early America, most chickens were considered “dunghill fowl,” a phrase that appears regularly in old documents and even in wills and estate inventories. Contrary to what the growers of the vegetarian chickens selling at your food coop would like you to believe, chickens are omnivores. They were associated with dung-hills because they can live on kitchen scraps and will happily pick through your compost pile, looking for the insects, worms, and grubs they consider special treats.

In the late 1840s and early 1850s when most Americans still lived close to the land, chicken breeding became a popular pastime. There was even a short-lived chicken mania and a poultry investment bubble in America, which began when the port of Shanghai was forcibly opened to western ships at the end of the Opium War. Because they can be fed so cheaply, live chickens were a regular part of the food carried on long sea voyages. A few exotic-looking Asian birds apparently survived their first voyages from China to America, and American breeders were excited by the large, attractive, feather-footed chickens they called Cochins and Shanghais after the birds’ ports of origin. The popularity and high prices paid for exotic birds prompted American farmers to pay more attention to chicken breeding, and soon varieties like the Plymouth Rock, the Rhode Island Red, and the Jersey Giant began to appear at regional fairs and agricultural shows. These varieties, now considered heritage breeds, were larger than the old dunghill fowl and were prodigious egg-layers. They are still popular as dual-purpose egg and meat producers.

After World War II, more than half the American population lived in cities where keeping livestock was usually illegal. When prosperous, professional families wanting more space moved to suburban developments rather than back to the countryside, backyard chickens became socially unacceptable even where it was possible to keep them. The sanitary cities movement had eliminated urban animals and the suburban lifestyle of mobility, consumerism, and affluence was quick to leave behind reminders of the hardships and Victory gardens of the Depression and the war years. The 1950s also saw the rise of scientifically-bred hybrid birds, and of the development of separate breeds for egg production and meat.

The average heritage hen lays about 200 eggs per year, lives up to eight years, and weighs five or six pounds. Today’s commercial layers are usually White Leghorn hens, a small Mediterranean breed that weighs three to four pounds, produces up to 320 eggs annually, and has a very high feed-to-egg conversion ratio. As egg production became a specialized business rather than something that happened in everyone’s backyard, feed conversion efficiency became much more important. It is not such a big deal when you keep a few backyard hens and they eat your kitchen scraps, grass, grasshoppers, and a little scratch feed. But feed efficiency is critical when you are managing two million hens in a factory. A smaller-sized bird was also valuable, because hens were kept eleven to a cage in 18 by 20 inch battery cages for the duration of their 72-week lives. 95 percent of the laying hens in America live in battery cages. The cage-free eggs you see selling for two to three times the price of regular eggs come from birds that don’t live in battery cages, but rather in large barns like broilers. Chickens raised for meat are even more specialized than laying hens. Although they are nearly all hybrid crosses of the White Cornish and the White Plymouth Rock breeds, the specific bloodlines are jealously-guarded trade secrets. Since the birds can’t reproduce naturally, breeding is centralized and three corporations control the primary genetic stock accounting for 80 percent of the 91 billion tons of broiler meat produced annually.

Cornish crosses have very large breasts, very short legs, and grow extremely rapidly. They are generally raised indoors on large open floors holding populations of up to a million birds. Unlike heritage chickens, hybrid broilers are not particularly effective as foragers. Broilers are usually fed medicated high-protein feeds, partly because hybrids are susceptible to illnesses that do not usually bother regular chickens, and partly because of the stress of overcrowding. The medication in the feed also promotes even more rapid growth in the fast-growing broilers. After about seven weeks of age, broilers begin to show signs of difficulty walking, and after nine weeks old they begin to suffer from heart disease and kidney failure. Their feed conversion has been improved by breeding to 1.9 pounds of feed to 1 pound of live weight, which is about twice as good as a heritage bird. But you have to feed them a specialized diet and be sure to kill them at eight weeks.

As you may know, chickens are making a bit of a comeback in hobby-farming and back-to-the land circles. There are several hatcheries that will send you day-old chicks by mail, and many towns and even some suburbs are beginning to allow backyard coops and small flocks. Oddly, although a variety of heritage breeds are popular for eggs, the hybrid broiler is still the best selling meat bird. The hatchery I use, for example, offers about twenty breeds of white-egg layers, thirty-five brown-egg layers, and specialty birds like the Chilean Araucana that lays green or blue eggs. For meat birds, however, the choices are the White Broiler or its recent hybrid cousins the Rainbow Ranger and Black Ranger, which are variations on the standard broiler that are slightly more mobile and grow out in about 13 weeks. The broilers are $2.40 each, and the Rangers are about $2.75. Recently, the hatchery added a fourth choice, which is the one I demonstrated in the video above. Instead of hybrid meat birds, you can buy what they call a Fry Pan Bargain, an assortment of whatever excess males the hatchery happens to have on the day you order. Since people mostly buy heritage hens for egg-laying, there are always leftover roosters that have to be shipped or killed. To avoid killing thousands of day-old chicks, the hatchery sells them at extremely low prices. You can buy Fry Pan chicks for 29 cents each if you take them a hundred at a time. The birds you receive are usually Rhode Island Reds, Plymouth Rocks, and Orpingtons, since those are the hatchery’s best-selling layer breeds. The heritage birds take longer to raise, but by the end of the summer they grow to three to four pounds each. While that is only about half the size of a hybrid bird at eight weeks, it is enough to make a decent family meal. And the heritage breeds can live on the pasture and eat mostly grass and bugs. Finally, if there is one you really like and you cannot bear to part with him, you can keep him, breed him with your laying hens and raise a whole new generation for free.

Not everyone can raise a hundred pastured chickens, of course. Even backyard chickens are not for everybody. But a lot of people could keep a friendly, colorful little hen or two in a coop on their porch or in the backyard and have fresh eggs for breakfast. Keeping chickens is really not that difficult. The hardest part, like many of the life changes that end up seeming inevitable years later, might really just be imagining it as a possibility.

One last issue to consider with poultry, which applies equally to hogs, cattle, and other CAFO livestock, is vulnerability. 2015 will be remembered by many American farmers as the year of the Avian Influenza. According to industry sources, H5N2 and H5N8 bird flu viruses swept through the Midwest in the Spring of 2015 in the worst epidemic ever experienced by American poultry farmers. At least 223 outbreaks were recorded, causing the destruction of tens of millions of chickens and turkeys. By late spring, the epidemic was national news. The New York Times reported that a single Iowa farm was being forced to euthanize 5.5 million laying hens and dispose of the carcasses. The farm, located in an Iowa county that earns close to $2 billion annually from agriculture, housed its layers in battery cages in 26 barns. Although the operators had isolated the outbreak to just two of those barns, the article said, they were forced to dispose of all their birds and thoroughly disinfect the entire operation.

While the epidemic was clearly frustrating for the farmers and tragic for all the chickens that had to be suffocated in spray-foam, there was more to the story than the Times reported. The Iowa farm the newspaper described was part of the Center Fresh Group, a corporation owned by eight Iowa families that controls 17 percent of the nation’s poultry and is the largest producer of eggs and shell products in America. Although the story said operators of the farm were “forced” by the USDA to destroy their birds, Center Fresh, like all the other operations that disposed of birds suspected of being diseased, killed their chickens voluntarily and was compensated by the USDA for the birds they destroyed. Chickens that died of disease were not covered by the reimbursement program, which provided growers with a strong incentive to cooperate with the government’s biosecurity protocols.

The flu outbreaks were blamed by the poultry industry on migratory waterfowl and the USDA issued instruction pamphlets on how to maintain biosecurity in commercial poultry operations. The precautions they recommended included eliminating wetlands and seasonal ponds used by migrating flocks of ducks and geese, and eliminating food sources for wild birds. Neither the industry nor the government commented on how the H5N2 and H5N8 influenza viruses, known to have originated in Asian commercial poultry, had migrated to the Americas and infected migrating ducks or how the disease managed to spread in ways that did not match the migratory routes. The industry and government biosecurity experts also failed to explain how so many flocks of commercial chickens, raised in cages indoors, managed to come in contact with the droppings of wild waterfowl. Media outlets like newspapers and TV news cooperated, reprinting the press releases issued by industry sources and the USDA without asking any questions. The poultry industry did notice that 90 percent of the flu outbreaks were in commercial flocks and only 10 percent in “backyard” flocks. But when the media mentioned this statistic, it was usually to emphasize the potential economic impact to growers forced to destroy million-bird flocks. No one asked why most backyard birds didn’t get the flu, just as no one had asked why wild birds, claimed to be the vector spreading the infection, were not sick.

Turkey producers were especially hard hit. The Hormel corporation, whose Jennie-O brand is the world leader in turkey products, warned that prices would rise steeply and that corporate profits would suffer. Biosecurity experts in the turkey industry claimed commercial flocks had caught the virus from wild turkeys. In Minnesota, the nation’s leading turkey-producing state, newspapers carried alarming stories of the nightmare virus and helpless farmers. Once again, wild turkeys, which regularly survive outdoors through Minnesota’s harsh winters, did not seem to be suffering. And no one could explain how barn-raised birds had caught the virus from their elusive woodland cousins. When scientists at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources announced there was no evidence linking wild birds to the flu outbreaks, the industry issued angry statements to the press, discrediting the scientists and reiterating their wild-bird theories. In late April, Minnesota’s Governor declared a state of emergency and visited a poultry company in southern Minnesota. A few miles from where the Governor commiserated with worried area residents was a commercial hatchery that ships 45 million day-old turkey poults to Minnesota growers every year. But no one seriously considered any of the commercial poultry industry’s centralized supply chains as possible vectors for disease. Minnesota’s leading newspaper, covering the Governor’s visit, quoted a local woman wondering about the mysterious disease threatening the region’s economy. “What is the source?” she asked. “Are they ever going to find the source?” A more accurate question might have been, are they ever going to honestly look for the source?

Further Reading

Simon Fairlie, Meat: A Benign Extravagance, 2011

Joel Salatin, Everything I Want to Do is Illegal: War Stories from the Local Food Front, 2007

Harvey Ussery, The Small-Scale Poultry Flock, 2013

Media Attributions

- 17565v © Fanny Palmer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cotton_plantation_on_the_Mississippi,_1884_(cropped) © Currier & Ives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1857 Farmyard © Fanny Palmer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gift_for_the_grangers_ppmsca02956u © J. Hale Powers & Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 4a31829v © Detroit Publishing Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Victory-garden © Morley Size is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2776334619_d3876183eb_b © Dan Long is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Iowa_harvest_2009 © Bill Whittaker is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Corn_Fields,_Iowa_Farm_7-13_(15277889101) © inkknife is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Hog_confinement_barn_interior © EPA is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Anaerobic_Lagoon_at_Cal_Poly © kjkolb is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Poultry_Classes_Blog_photo_-_Flickr_-_USDAgov © USDA is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

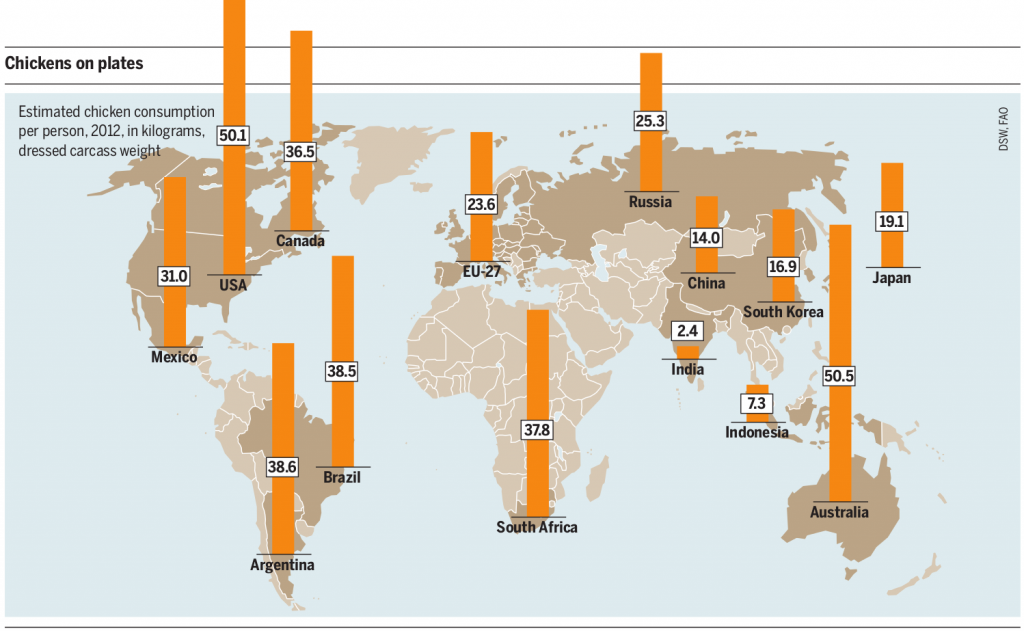

- Meat_Atlas_2014_Estimated_chicken_consumption © Heinrich Boell Foundation is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Indiapoultry © Sangamithra Iyer and Wan Park

- Broilers © Naim Alel is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Poultry_of_the_world © L. Prang & Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- chicks2 © Dan Allosso is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- IMG_0002 © Dan Allosso is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license