4 Frontier and Grid

Looking at Colonial North America, we noticed that many early English coastal settlements had been established on sites previously used by native Americans, who had disappeared due to disease or the social chaos caused by epidemics. As settlement moved westward, Euro-Americans were less likely to be able to take advantage of abandoned settlements and native improvements to the land. As time passed, fields and forests Indians had cleared and maintained with fire filled in again. And sometimes settlers farther west found natives still occupying their ancestral lands and unwilling to share with people they considered invaders. Many settlers tried to choose uncontested places to make their homes. They were not always successful, as the long string of nineteenth-century Indian Wars demonstrates.

The continent was large and the population density of native cultures was often much lower than that of the Euro-American settlements. Though there were always pioneers willing to take their chances in Indian Country on the frontier, many families moved to regions already considered to be well-established territory open for settlement. Although there were some notable exceptions, most of these regions were reasonably safe from Indians, who had already been pushed farther west. So for many settlers the idea of moving westward involved less Indian fighting and more clearing unoccupied land to make it productive for their new style of European-influenced American agriculture.

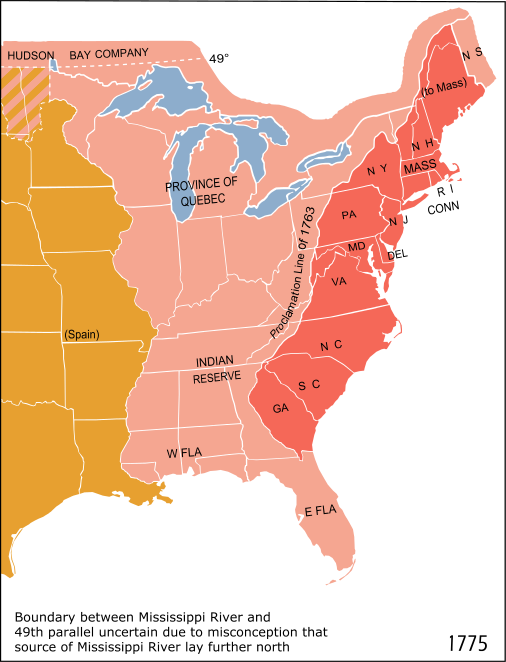

The frontier has always been a powerful magnet for the American imagination. It is not well remembered in most of our histories, but one of the grievances that led to the American Revolution was colonial anger that the British had accommodated the Indian nations that had allied with them against France in the Seven Years War (1756-63) by limiting westward expansion of the colonies. The Cherokee Nation and the powerful Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) had sided with the British against the French and against other native nations. But like the other natives, England’s Indian allies were alarmed by the inexorable growth of the colonies and wanted some assurance that their territories would be respected. In 1751, Benjamin Franklin had boasted that for every English baby born in Britain, two were born in America and soon there would be more Englishmen in the New World than in the old. The Iroquois, whose homelands included what is now western New York and Pennsylvania, saw their political stability and way of life threatened by expanding English settlement. So, as a reward for the Indians’ support and out of respect for the Confederacy’s undeniable military strength, the British government issued a proclamation establishing a western colonial boundary. The Proclamation Line followed the Appalachian Mountains, cutting through western New York and Pennsylvania and creating an Indian Reserve stretching from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

The English colonists were enraged. Many of their royal charters had given the colonies land grants extending to the Pacific Ocean. The colonists believed the Crown’s acknowledgement of Indian claims to that territory was a betrayal of their futures. And for many, the issue was more than just symbolic. Anticipating growth, many Americans had begun investing in the territory beyond their settlements. Following the proclamation, wealthy land speculators like George Washington instructed their agents to begin buying as much Indian land west of the mountains as possible. Washington warned his partners to keep “this whole matter a profound secret.” A lot of the surveying work Washington was famous for doing as a young man, he did on the wrong side of the Proclamation Line.

When the Sons of Liberty and the Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and drafted the Declaration of Independence, one of their many complaints against King George III was that he had unleashed “merciless Indian savages” against the colonists. Natives continued to resist when colonists appeared on their lands. Many Indians sided with Britain during the Revolution, seeing continued British control of the Americas as their best hope of retaining their land and sovereignty. Unfortunately for the natives, the colonists won their independence and barriers to westward expansion were swept away. At the Treaty of Paris in 1783, Britain relinquished its claim to all the territory east of the Mississippi to the United States. Although the new nation’s economic fate still depended heavily on its being part of an Atlantic trading community dominated by England, the unconquered frontier to the west was a strong influence on American policy and culture.

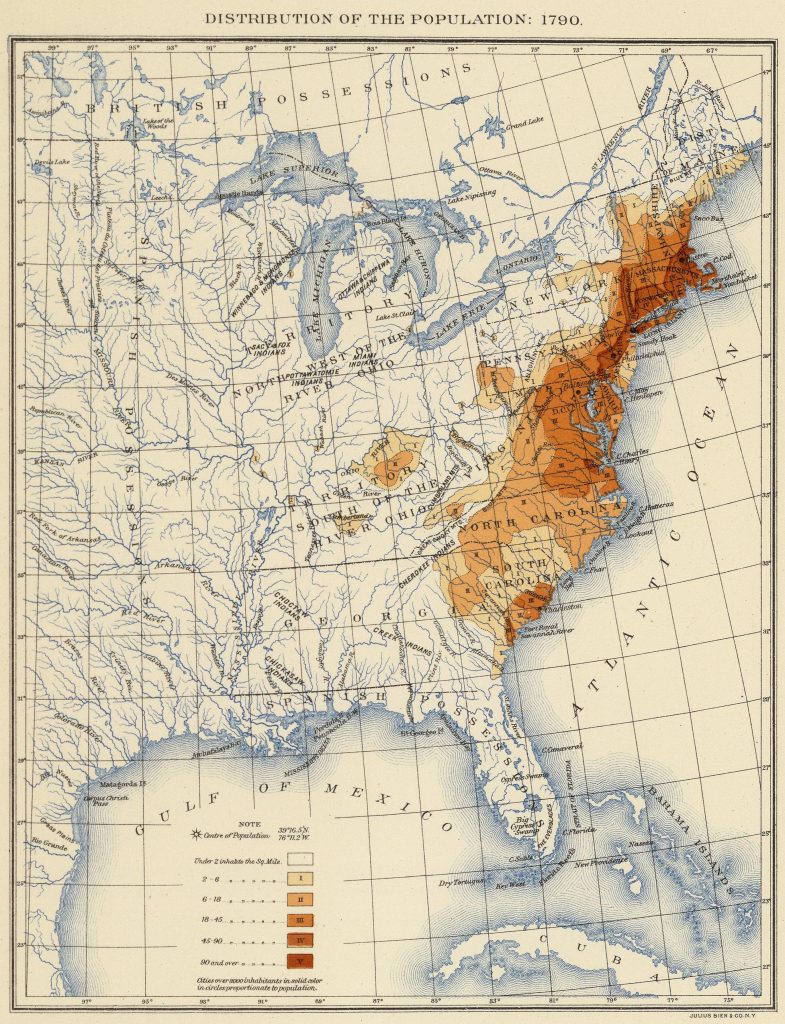

When the United States took its first national census in 1790, Americans discovered that half their population was under the age of 16. At the end of the eighteenth century, the American birthrate was higher than any birthrate ever recorded in a European nation. For comparison, it was more than double the highest birthrate achieved during the post-World War II baby boom. America’s growing population needed an outlet. For example, the western Massachusetts hill-town Ashfield contained 130 families in the early 1800s. Most of the town’s residents were farmers; even the town doctor kept a cow and raised hay to feed his horses. The average family had five children. Ashfield’s largest families had eleven.

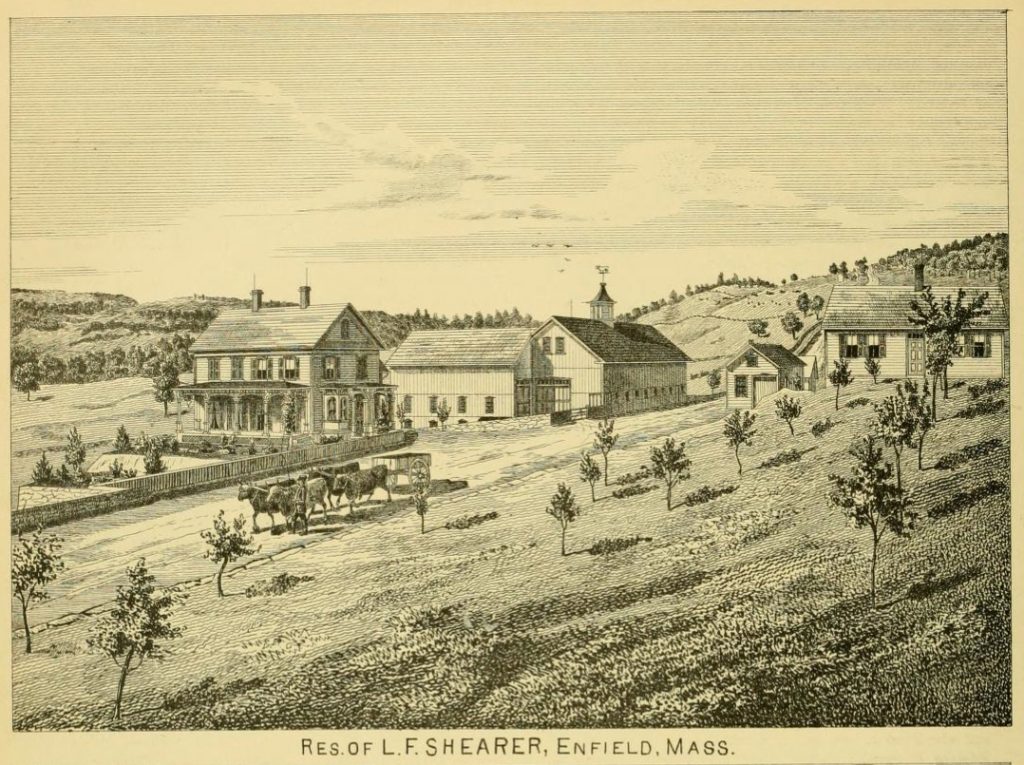

As the children of Ashfield and other young Americans grew up, they naturally looked westward. In contrast with the colonial Hudson River Valley, which had developed a feudal social structure of large estates and tenant farmers, and the tidewater South, which had developed an economy dominated by plantations worked by enslaved Africans, New England and the Middle Colonies had established a system of small-scale land ownership that continued after independence, creating large numbers of modest, self-sufficient farms. Yeoman farmers owned their land and fed their families and livestock from its produce. If farmers produced surpluses they would sell them, often to the town miller who would aggregate local products and resell them in Eastern cities. The cash farmers earned selling their surplus could be used to buy manufactured goods not available in the local economy, and sometimes even luxury items. Some farmers even grew specialty crops specifically for distant markets (Ashfield happened to specialize in peppermint). But their priority, if push came to shove, was feeding their families. And as those families grew, feeding everyone became harder to do.

Most farm families owned about 80 acres, and in a town like Ashfield much of that land was made up of wooded hills and rocky pastures, difficult to cultivate. While a hard-working farm family could feed itself, only one son could realistically inherit the farm and have enough tillable land to support a new family. Splitting a farm between all a family’s children would leave no one with enough farmland to raise the next generation. The obvious solution was to pass the farm to one son, which meant that the rest of the children had to repeat the work of their parents and start a new farm. As local land filled up, those children looked west.

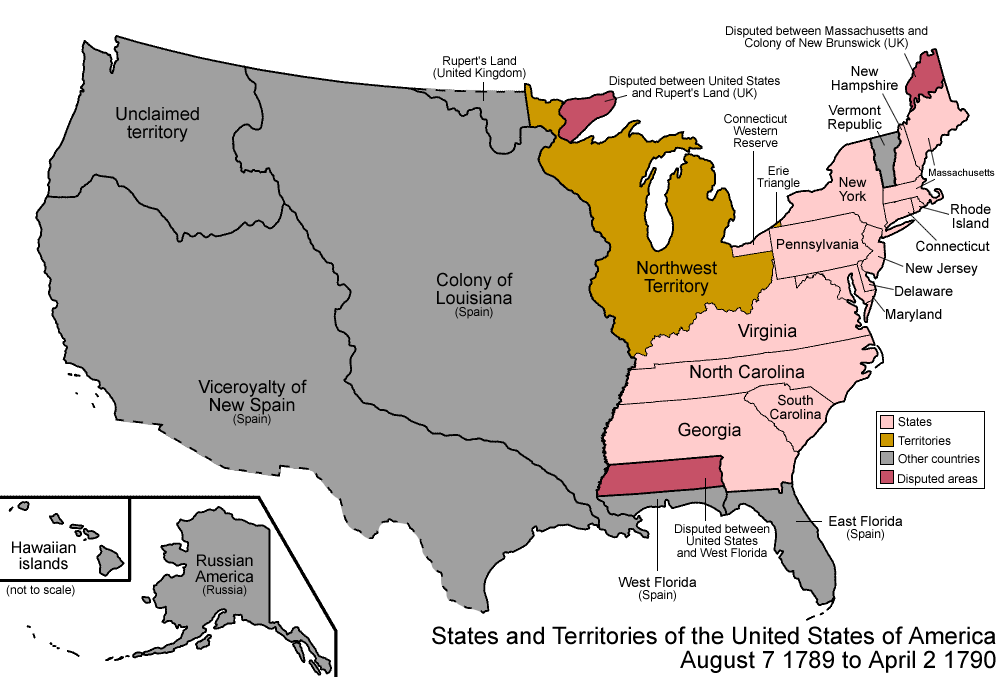

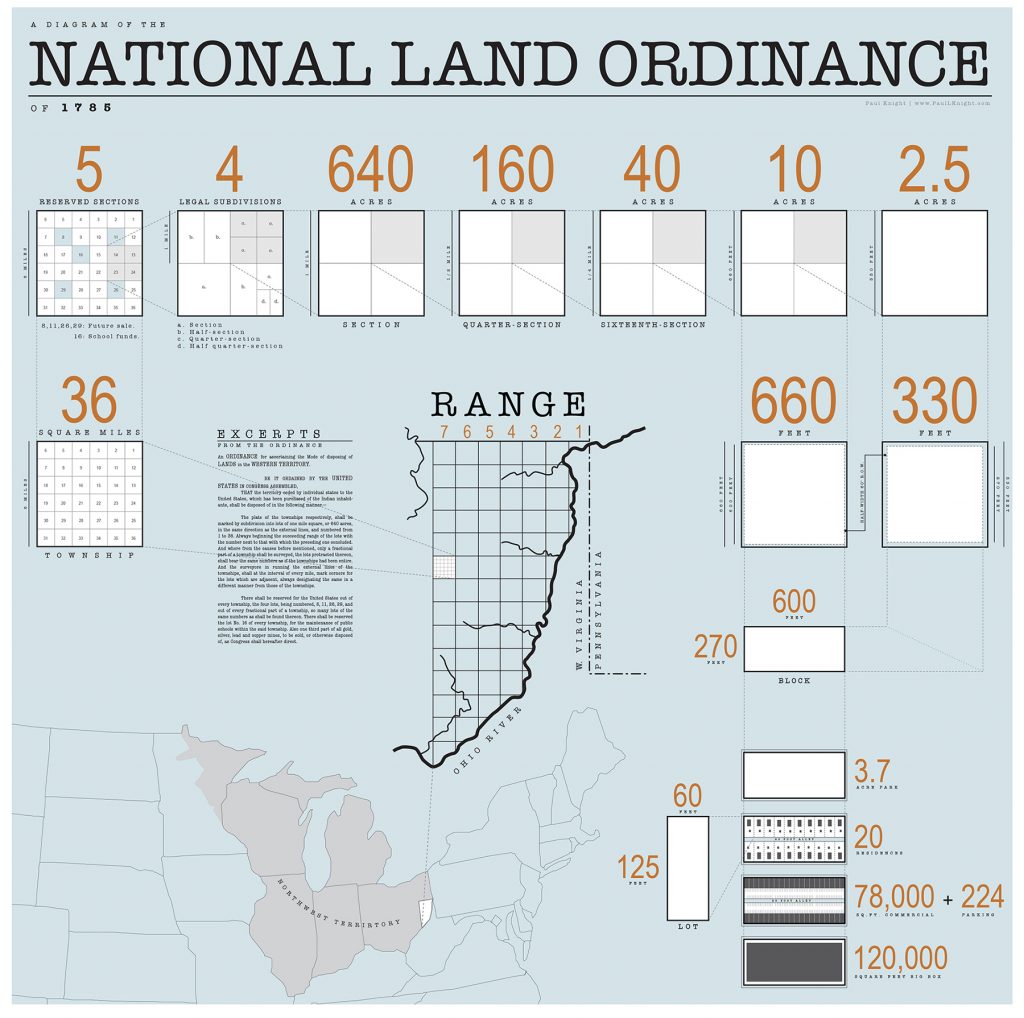

The new United States government made it easy for young families to start new farms. The Continental Congress appointed a committee that included Thomas Jefferson, to figure out how best to dispose of the land the nation had acquired in the 1783 Peace Treaty with England. Technically this territory belonged to the nation rather than to the thirteen new states; and since under the Articles of Confederation, Congress was not allowed to levy taxes, land sales were considered an appropriate way to raise funds to run the government. The result was The Northwest Ordinance, which created the Northwest Territory and specified the way western lands would be surveyed, parceled, and sold.

The Northwest Territory included lands that would become Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and eastern Minnesota. The Ordinance decreed that townships would be standardized as six-mile squares divided into thirty-six lots, called sections, of one square mile each. Five of these sections would be reserved for government or public purposes, including lot number sixteen in the center of each township, which would hold a mandatory public school. With half the nation’s population under age sixteen, free public education was considered a key to American progress, so public schools were built into one of the United States’ earliest national laws.

Each square-mile section contained 640 acres of land, which could be subdivided into quarter-sections of 160 acres each or half-quarter sections of 80 acres, which most people in the early nineteenth century considered the smallest size for a successful farm. In towns and cities, land could be subdivided down to 60 by 125 foot single family building lots. The price of the land on the frontier would remain low for most of the nineteenth century, beginning at $1 per acre and later rising to $1.25 per acre, although after the Specie Circular of 1836, payments at the Land Offices had to be made in cash rather than bank notes. In the cities, speculation could quickly drive land prices up, causing property bubbles like the one that inflated Chicago real estate values by 40,000 percent in the early 1830s, driving land prices to New York City levels before bursting in a storm of foreclosures in 1841.

Western New York and the territory just west of the Ohio River were among the first public lands to be surveyed and sold. Ashfield families like the Ranneys (whose family letters you’ll read in the chapter supplement) followed the Mohawk Valley and made farms in territory that had previously been beyond the Proclamation Line, on land taken during the Revolutionary War from the Haudenosaunee. Like many forward-looking families, the Ranneys invested in frontier land in Michigan at the same time they were moving from Massachusetts to New York. Just a few years after the family moved west from Ashfield, several of the younger Ranney brothers moved farther west. But family ties held, and the Ranneys remained in close contact throughout their lives.

Settlers from Connecticut and New Jersey rushed into the Ohio River Valley, which was close to Virginia and Western Pennsylvania across the Appalachians and the old Proclamation Line. Ohio Valley land was prized because although it was difficult bringing wagon-loads of farm products across the Allegheny Mountains to market, the Ohio River began at Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) and flowed into the Mississippi at what is now the southern tip of Illinois. Enterprising farmers could float their surplus grain down the rivers to the Spanish port of New Orleans, where merchants could put it on ships bound for East Coast Cities, the Caribbean, or even Europe.

Western New York filled quickly. Settlement of the Ohio Valley was equally rapid, and the Ohio Territory became a state in 1803. Many new Ohio farmers were from the middle states like Connecticut and New Jersey, whose original colonial charters had included parts of the Northwest Territory. As they left their settled homelands and cut new farms out of wild land, these Yankee farmers started a pattern that would repeat itself many times over the next century.

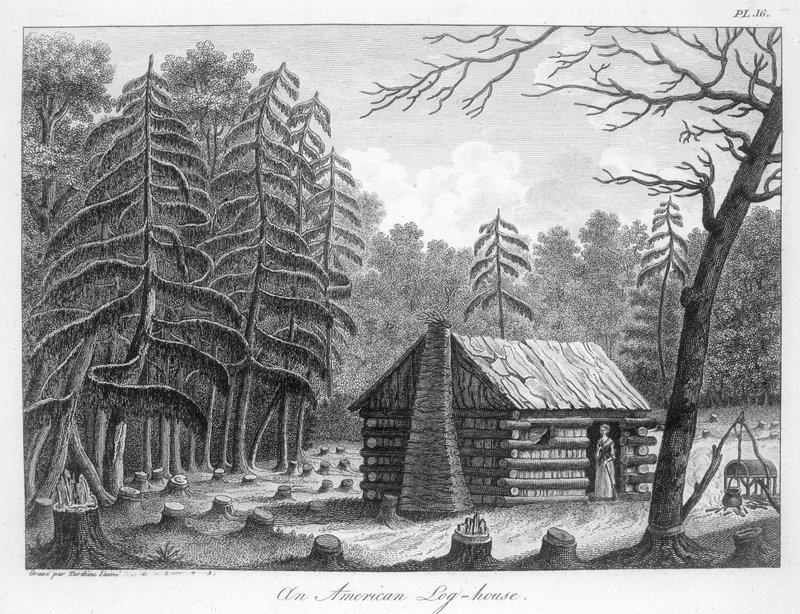

Pioneer Farmers

When many settler families arrived at the parcel they had often bought sight unseen from the land office, their new homestead was often trackless forest. Old growth woodlands covered most of the area between the Atlantic coast and the Mississippi, so this experience was repeated again and again. Before doing anything else, settlers moving to western Massachusetts in the 1760s, or western New York in the 1810s, or Michigan in the 1830s would need to build a shelter and clear enough land to raise the crops that would get them through the first winter and feed a few animals. Settlers often cleared fields by girdling trees, cutting a broad strip of bark to kill the tree. They planted corn Indian-style in hills between the standing deadwood. The following season, they cut and burned the dead trees, and after rotting a few years the stumps could be removed and the field plowed for wheat. A hardworking settler family could clear about 7 acres per year. The ashes from the burned forest provided nutrients for the soil and also potash for sale in the eastern cities. Potash was used to make soap, and was often the first product western settlers shipped back to eastern merchants.

Pioneer life was very hard work. In addition to clearing land, pasturing animals, and raising crops, settlers had to cut and split from thirty to forty cords of firewood per year for heating and cooking. Women spent much of their time cooking, which is a slow and tiring process when you do it over an open fire in a one-room cabin. In their spare time pioneer women raised their five children and wove cloth to make the family’s clothing.

After a couple of decades, a successful settler family usually had 20 to 30 acres of improved land and a substantial woodlot to supply their annual firewood needs. Since the frontier had been surveyed into six square-mile townships on the grid, there was usually a village or town within walking distance, providing a school, social life and a small market for surplus goods. Merchants often took produce from farmers in payment for manufactured goods and supplies the farmers could not make themselves. The merchant shipped farm products to cities for consumption or export, and bought supplies of city goods on annual buying trips to sell in town. In addition, peddlers carrying baskets and trunks of small goods like sewing needles, buttons, and medicines traveled on foot throughout the states and the new territories, bringing goods and news to even the remotest farmsteads.

By the time the farm was well established the family was usually quite large. One son, usually the youngest, would inherit the farm in return for taking care of his parents at the ends of their lives. Youngest sons tended to inherit the farm in the northeastern states and the territories Yankee families settled, because the older sons would have grown up too soon for the parents to be ready to retire. The youngest stayed at home and took care of the aging parents in exchange for inheriting the family property. The older sons, who would usually be adults long before their parents were ready to give up working, inherited cash when there was an estate to divide, and they often moved farther west to establish their own farms while their parents were still alive.

Free Soil and the Trail of Tears

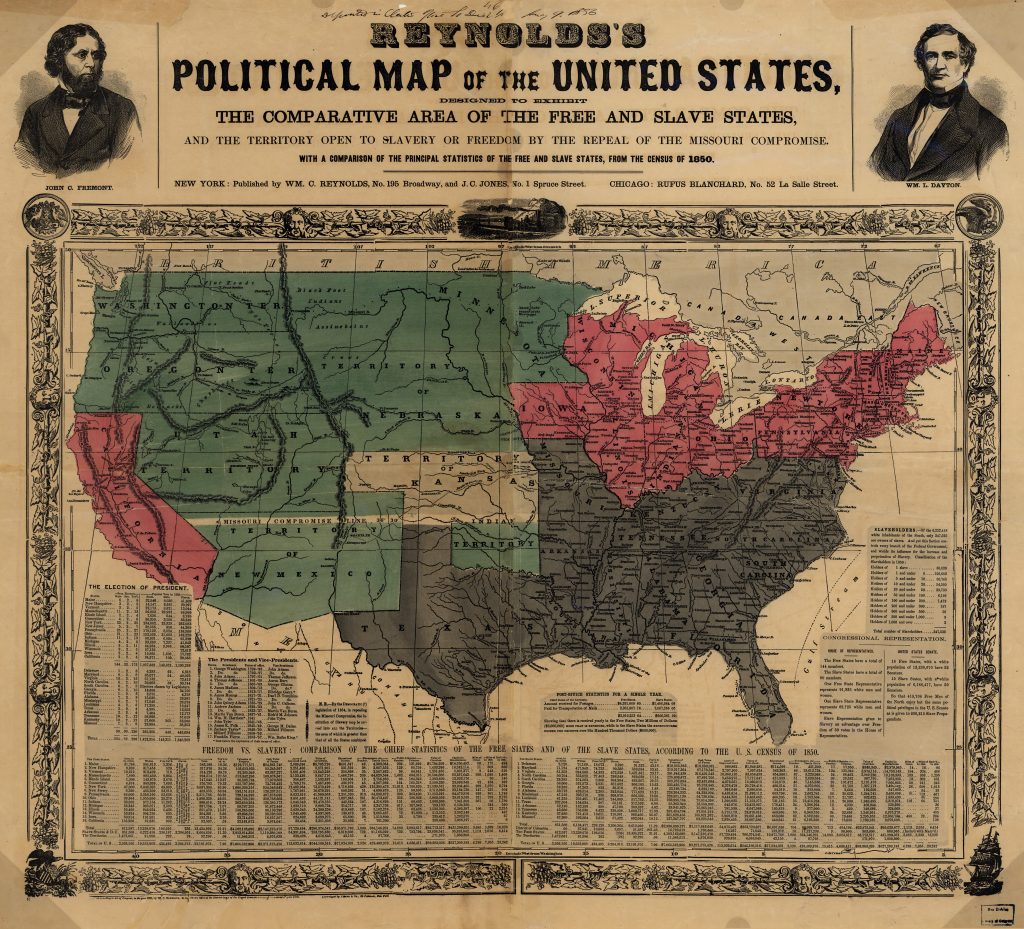

The Northwest Ordinance, which was passed in 1787 before the U.S. Constitution was even ratified, opened the territory that would become Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. In addition to establishing the grid and setting aside land for public schools, one of the most important elements of the Ordinance was that it prohibited slavery in the territories. This prohibition had a major impact on both the politics and the environments of the territories and states created by the Ordinance because it prevented the spread of large plantations based on slave labor and encouraged the style of small-scale land ownership and family farming we now associate with Thomas Jefferson’s ideal of the independent yeoman farmer. Jefferson, a slave-owner who wrote eloquently about freedom and equality, was a living symbol of the young nation’s moral struggle. Many northern farmers moving west came from old Yankee families with long traditions of sympathy for the abolitionist cause. Others understood that their small-farm produce would have difficulty competing in the market with farm products that had been produced using the unpaid labor of plantation slaves. Many western farmers joined Free Soil political groups that helped create the anti-slavery Republican Party (established in 1854 in either Ripon Wisconsin or Jackson Michigan by anti-slavery activists) and elect President Abraham Lincoln in 1860.

Thomas Jefferson’s 1803 Louisiana Purchase had doubled the size of the United States and opened an even wider territory for expansion, extending all the way to what is now the Idaho border in the northwest. But ironically, it had also reopened the conflict over slavery in the territories. When compromises between free-state and slave-state delegates resulted in a U.S. Constitution that failed to abolish slavery, most Americans believed the “slave problem” would take care of itself. The importing of new slaves from Africa ceased in 1807, and opponents of slavery believed the slavery would become increasingly irrelevant as southern slave states were surrounded by new, free states on all sides. However, as territories gained statehood, it became clear to southern politicians that the balance of power would shift toward the abolitionists if slavery was prohibited in all the new states. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 attempted to retain the balance of power be admitting states in pairs: one free and one slave. When Kansas and Nebraska territories were preparing for statehood in the 1850s, the compromise was broken in favor of a scheme described by its proponents as “popular sovereignty.” Under the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the populations of the territories would vote on whether to enter statehood on the free or slave side.

Supporters of slavery immediately began trying to influence the election through bullying and intimidating residents. Abolitionists retaliated by sending over a thousand Free Soil settlers into the territory o swing the election their way–many armed with Sharps rifles reportedly supplied by New England preacher Henry Ward Beecher. Two separate territorial legislatures claimed to represent the will of the people, each claiming the other was the result of voter fraud. Two constitutions were written, one supporting and one opposing slavery. Vigilante groups on both sides terrorized and occasionally murdered their opponents. The conflict which became known as “Bleeding Kansas” was not resolved until the Civil War, when Kansas was finally admitted to the Union in January 1861 as a free state.

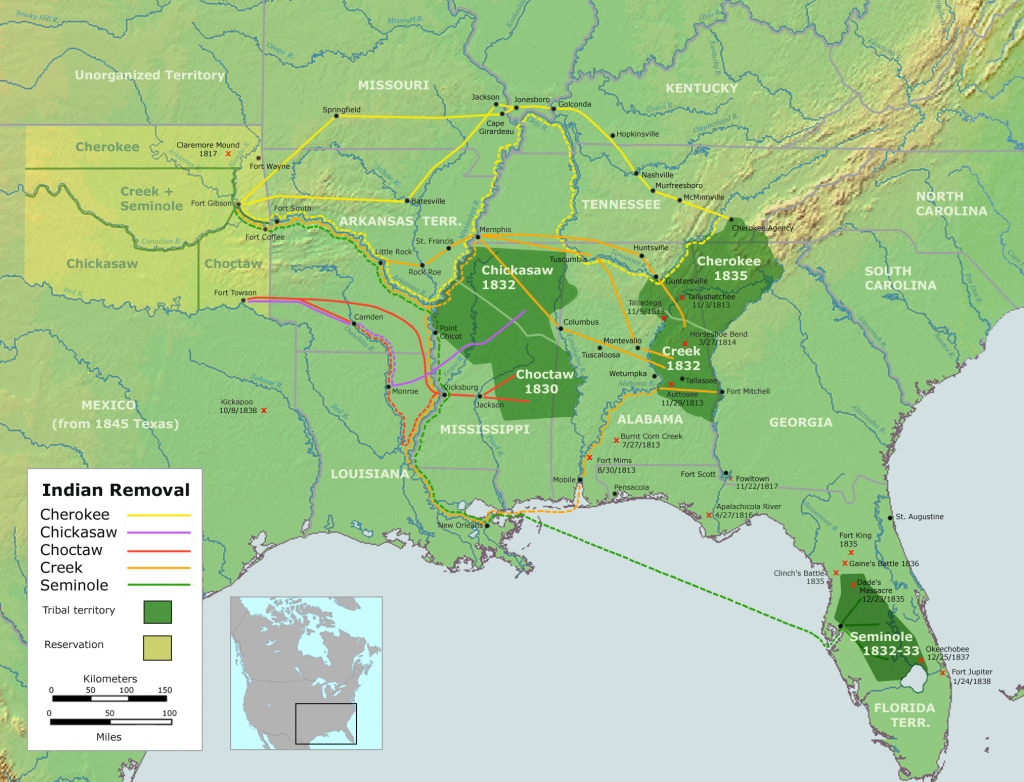

By 1810, after nearly a generation of westward expansion following the Northwest Ordinance, the Ohio and Cumberland River Valleys were beginning to look like the settled areas of the original eastern states. Cincinnati, Frankfort, and Nashville were becoming centers of commerce, as was Buffalo New York on the shore of Lake Erie. Saint Louis on the Mississippi and Detroit on the western end of Lake Erie were also growing, as people continued looking to the frontier for new opportunities. In the Southern States, westward expansion of the plantation system was challenged by the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations. The original policy of the U.S. government under President George Washington (and continued by Thomas Jefferson) had favored “acculturation” of the natives and their assimilation into American society. Impressed by American institutions, the Indians had adopted many of the elements of Euro-American culture including a two-house legislature, a legal system based on that of the United States, and even slavery. But Southern planters were not equally impressed by their Indian neighbors, and lobbied the government to remove the Indians and make western lands available for their own expansion. President Andrew Jackson, himself a Tennessee plantation owner, led a campaign for legislation to remove the Indians from their lands. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 passed in spite of stiff opposition, including that of Tennessee Congressman Davy Crockett, who spoke out against the bill. The new law was quickly judged unconstitutional by an 1832 Supreme Court decision (Worcester v. Georgia) that ruled in favor of the natives. But President Jackson ignored the court’s decision and the natives were removed to a region known as The Indian Territory, which later became Oklahoma, along the infamous Trail of Tears.

Transport and Commerce

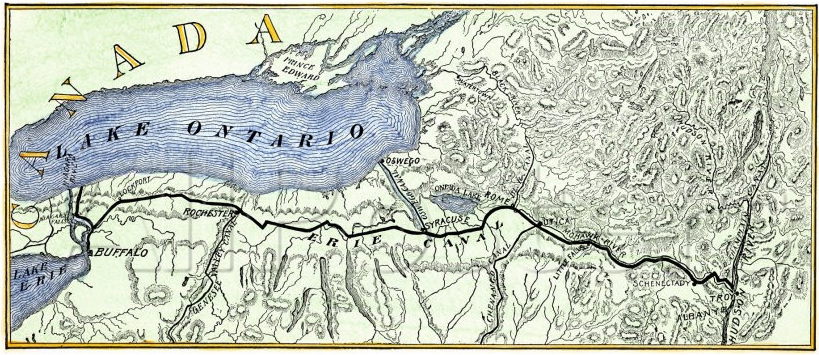

Along with population pressure, one of the main factors accelerating western settlement was improving transportation technology. Although they were far from eastern cities and clearly understood the importance of remaining self-sufficient, many westerner settlers still considered themselves part of the Atlantic commercial world. Success beyond mere subsistence for a growing number of farmers depended on their ability to get their produce to eastern markets. The first phases of expansion had allowed farmers to use waterways like the Hudson River in New York and the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers in the Middle West, to float their surpluses to markets like New York City, St. Louis, and New Orleans. The growth of trade convinced Americans that transportation was the key to expanding the frontier. We return to this topic in greater detail in Chapter Six, but here is an early example. The Erie Canal, begun in 1817 and completed in 1825, opened not only western New York but the entire Great Lakes region to commercial shipping. Less than ten years after the canal opened, the last fulling mills that processed homespun cloth disappeared from the Mohawk Valley, as western New York farm wives jumped at the opportunity to reduce their workload by buying eastern textiles.

By 1830, after nearly another generation of growth, the sons of farmers who had moved to the Ohio Valley and to western New York were on the move again. This time, their destinations were Illinois, Indiana and Southern Michigan. Cincinnati and Louisville were now major cities, and settlement was extending up the Missouri River as well as the Mississippi. Federal land offices sold most of the land between the original 13 states and the Mississippi during the first half of the 19th century. Beginning with the Northwest Territory, the land was surveyed and a grid of townships laid out. This pattern of well-organized settlement can still be seen in satellite images, or even from the windows of airplanes flying over the Midwest. The average size of a working farm today is closer to a full mile-square section than to the quarter or half-quarter section the original settlers had bought at the land office, but the grid pattern can still be seen from above. Farm technology like John Deere’s 1838 steel plow and Cyrus McCormick’s reaper, patented in 1837, helped western farms produce wheat for the commercial market. Bad harvests in Great Britain and wars in Europe provided high profits to exporters throughout much of the nineteenth century. More eastern farmers moved west, often selling old farms near growing cities and suburbs at profits that allowed them to buy substantially more land at cheaper western prices. The Land Office’s typical price during the first half of the nineteenth century remained $1.25 per acre.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Midwestern farmers were solidly embedded in an international commercial network. Cincinnati, on the Ohio River, was packing so much bacon and salt pork that the city became known as Porkopolis. The end of Europe’s Crimean War in 1856 cut grain prices by two thirds, helping to trigger the Panic of 1857 and a recession that lasted several years. Like it or not, American farmers settling the frontier were a key element of America’s growing power in international commerce.

Families and Immigration

Historians (and novelists, and later screen-writers) have often claimed that pioneers moving West were forced to severe all their ties with homes and families, and strike out on their own. Some have even suggested that migration to the frontier wiped away all the trappings of “old world” culture and produced a new, distinctly American civilization. Many argue that the stresses of frontier life may have helped produce the individualism and focus on nuclear families considered such a distinctive part of the American character. The image of the independent American, and especially the cowboy, has become an important part of our national self-image. The concept of Manifest Destiny, that America had a special mission to spread the virtues of democracy across the continent, was the public expression of the idea that the American character was unique and superior.

It’s quite true that it took courage and self-reliance to settle the Midwest or to travel all the way to the west coast, which before the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 required a grueling month-long trip on foot or horseback across the continent or a dangerous ocean voyage around the Straits of Magellan at the bottom of South America. But remarkably, families managed to stay connected in spite of these distances. For example, the Ranneys, whose letters to each other you will have the opportunity to read in the chapter supplement, were a Scotch-Irish family who had arrived in Colonial Connecticut in the 17th century. Several brothers moved to Ashfield Massachusetts about 1790, and their sons moved on to Phelps in western New York in the 1830s. A few years later, several Ranney brothers and cousins moved on to Michigan. A couple of Ranneys went even further and had adventures in the Indian Territory, Kansas, and the California Gold Rush. But throughout the nineteenth century, the brothers kept in touch through frequent letter-writing, visited each other, and even did regular business with each other. Michigan Ranneys sold farm produce to their merchant brother Henry in Massachusetts, and family members regularly loaned money to each other across the miles. The important point is, many American pioneers continued to consider themselves part of extended families and diligently held onto family connections in spite of great distance and limited communications.

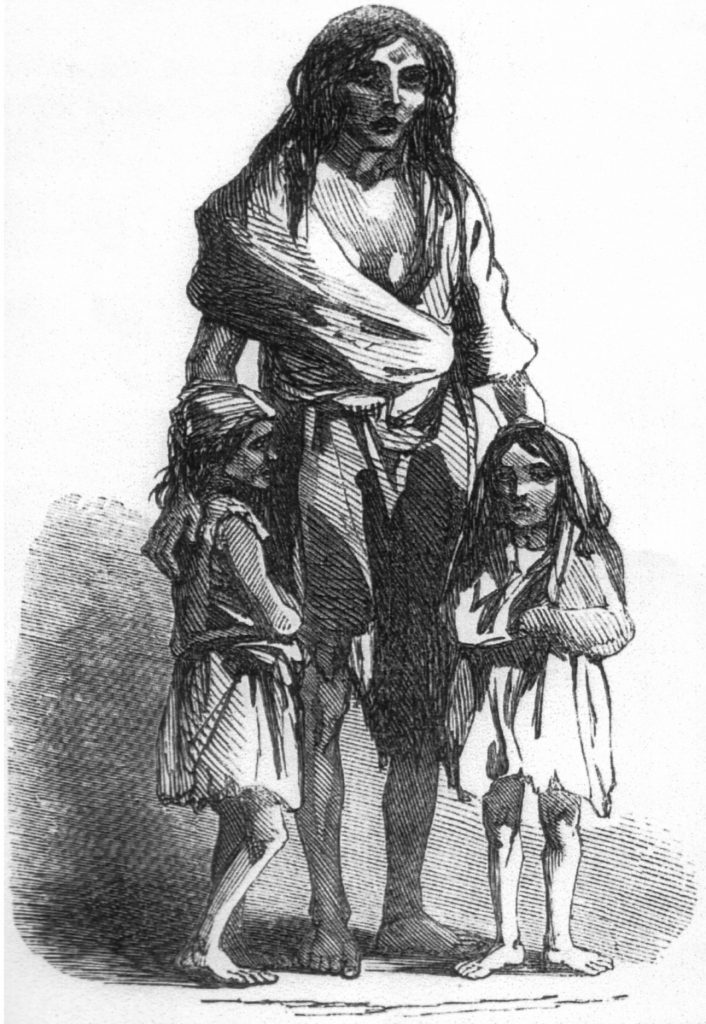

In addition to families extending themselves westward, immigrants from Britain and Europe joined the flow of farmers and farmers’ sons to the frontier. America’s poor diplomatic relations with England hampered immigration until after the conclusion of the War of 1812, but the end of hostilities opened the floodgates. Continuing wars in Europe and the social upheavals of the industrial revolution strengthened a flow of immigration that continued throughout the nineteenth century. In the late 1840s, nearly half the immigrants from Europe to the United States were Irish, fleeing the agricultural disaster known as the Irish Potato famine. Unlike the Andean Indians who had developed hundreds of varieties of potatoes for a wide range of purposes, Europeans grew only a few varieties bred from a small batch of imported seed potatoes. 350 years after the first potatoes had been brought to Europe by Columbus, most of the two million acres of potatoes grown in Ireland were a single variety, the Irish Lumper.

Potatoes were so inexpensive to grow, reliable, and high-yielding that the population in Ireland had exploded by the early nineteenth century. From a starting point of about 1.5 million in 1600, Ireland’s population grew by 600 percent in 200 years, reaching about 9 million people by the early 1800s. Of those 9 million people, four out of ten (or over 3.5 million people) ate no solid food but potatoes. Monoculture created vulnerability, because both Ireland’s economy and a large part of the nation’s food supply depended on a single crop. When the first reports of potato blight came in September 1845, the English landlords who owned most of Ireland’s farmland were slow to react. In the next two months, the blight wiped out about three quarters of a million acres of potatoes. The following year was worse, and the landowners had made no efforts to plant other crops or even blight-resistant varieties of potatoes. The year after that was even worse. Over a million people died, and about a million and a half fled Ireland. By 1850, Irish immigrants accounted for more than half the populations of Boston, New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia.

After 1850, immigration from Germany accelerated as Germans fled the chaos caused by their unsuccessful revolutions of 1848 and 1849. Over 42 million Americans of German descent were counted in the 2000 census, making German-Americans the largest ethnic group in America. While some of these German and the earlier Irish immigrants farmed, many became tradesmen, factory workers and laborers in Northeastern cities and in the newer cities of the northwestern frontier. Pittsburgh, Toledo, Milwaukee, Chicago, and Bismarck North Dakota were all noted in the 1900 census as having populations of between 50 and 75 percent “whites of foreign parentage.” The black population, of course, was still largely trapped by slavery and its aftermath in the South. The slave economy is also cited as a major cause of low immigration to Southern states in the 19th century. Immigrant farmers or wage-workers from Europe had no place in a society where most wealth was held by aristocratic families and most of the work was done by plantation slaves and later by destitute share-croppers.

No Decline

For a long time, historians believed that at around the same time that the Civil War destroyed the plantation system in the South, transportation and western farms had killed agriculture in the old northeast. Western farms were larger, they said, and the land was more fertile and easier to work than the hilly, rocky, exhausted soils of the northeastern states. This belief influenced the Country Life policies of Progressives in the early 20th century and has lived on in current farm and environmental policy, as we will see in later chapters. But if we look more closely at the details, a different picture emerges.

A closer look at data on land ownership and farm produce shows that New England farmlands continued increasing and forests continued shrinking until the final few years of the 19th century, by which time New England was over 90% deforested. This was long after the Midwest had taken over as the breadbasket of America, vastly outproducing the northeast in staple crops like wheat and corn. Hillside Yankee farm fields where it had always been difficult to grow wheat no longer had to try. They became pastures for Merino Sheep, which became a highly sought-after premium breed. Growing cities certainly lured people off eastern farms to work in factories like the textile mills of the Merrimack Valley which we cover in Chapter Five, but urban growth also provided a very lucrative market for farm products. And although eastern farmers with their small, steep, hillside fields could no longer keep pace with the Midwestern farmer in corn or wheat production, they could easily out-compete him on milk and hay. The bulkier and more perishable a product was, the greater the advantage for the local farmer. Eastern farmers became dairymen and grew hay to feed urban horses (before the age of cars and trucks, there were a lot of urban horses). Eastern truck farms grew fruits and perishable vegetables for nearby city people. As cities grew, the number of factory and office workers who earned wages rather than producing their own food increased dramatically. In the first US. Census after the Civil War, less than half of the people counted were listed as working in agriculture. This division of labor between people who grew their food and people who did not accelerated and ultimately created a new profession and a special class of people, American farmers, who were responsible for feeding the rest of us. This major shift in American culture also had major implications for the environment, as we will discover.

It’s easy looking back from the present, when only a tiny proportion of Americans can claim to be self-sufficient, to romanticize the yeoman farmer or the pioneer. Many historians share this romantic perspective, and some even insist that nineteenth century farmers fled westward to avoid the degrading capitalism of the cities. However, except for a small number of nineteenth-century Americans who joined religious settlements or utopian communes, most of the settlers who moved west remained interested in the culture and commerce of the eastern cities. Like the Mohawk Valley farm wives who had abandoned home weaving as soon as the Erie Canal brought affordable eastern textiles to their doorsteps, most Americans who moved west tried to maintain a healthy balance between commerce and self-sufficiency. The terms of the negotiation have changed over time, but the challenge to find that balance is one we still face today.

https://vimeo.com/315323972

https://youtu.be/WQpAzeydoZA

Further Reading

Christopher Clark, The Roots of Rural Capitalism. 1990.

Susan E. Gray, The Yankee West: Community Life on the Michigan Frontier. 1996.

Malcolm Rohrbough, The Land Office Business: The Settlement and Administration of American Public Lands, 1789-1837, 1968. The Trans-Appalachian Frontier, 2008.

Media Attributions

- Emanuel_Leutze_-_Westward_the_Course_of_Empire_Takes_Its_Way_-_Capitol © Emanuel Leutze is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 506px-Map_of_territorial_growth_1775.svg © Cg-realms is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1790 Population © Henry Gannett, Statistical Atlas of the United States, 1890 adapted by Photo by Dan Allosso is licensed under a Public Domain license

- United_States_1789-08-1790-04 © Golbez is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1785 Ordinance Diagram 3 © Isomorphism3000 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- pioneer © Georges-Henri-Victor Collot is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Reynolds’s_Political_Map_of_the_United_States_1856 © Reynolds is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Trails_of_Tears_en © Nikater is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Erie-canal_1840_map © Unknown (1840) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- American_Progress_(John_Gast_painting) © John Gast is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Irish_potato_famine_Bridget_O’Donnel © Illustrated London News is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1879EnfieldFarm © L.H. Everts is licensed under a Public Domain license