5 Commons, Mills, Corporations

Along with their traditional European ideas about culture, farming, and social organization, the English men and women who colonized North America brought with them a legal tradition known as the Common Law. English Common Law is a set of legal principles dating back to the Middle Ages. In this tradition the sources of the law and its authority are not royal decrees or legislative acts, but rather the accumulation of judges’ decisions on specific cases. Murder, for example, is a Common Law crime in Britain. It never required an Act of Parliament to declare murder illegal. Government can influence the Common Law, however; as it did when the British Parliament changed the mandatory sentence for murder from the death penalty to life imprisonment. The interaction between legislation and Common Law is important in American Environmental History because throughout most of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries our relationship with our environment has been shaped less by legislative deliberations than by routine court decisions that have created a series of legal precedents regarding property, usage rights, and liability.

The detached, somewhat alienated relationship modern Americans have with our physical environment and America’s culture of large corporations that often seem above the law actually developed together, because many of the most successful early corporations radically changed their physical environments. The Common Law America inherited from England contained a long list of precedents that guided judges in arbitrating between the claims of people whose interests conflicted. Some of these precedents dated back to the Roman Empire, giving judges clear guidance in deciding the rights and responsibilities of individuals. But as American commerce and industry became more complex, the law came to grips with the fact that society was not made up only of individuals. Even though Americans had left behind the royalty and hereditary nobility of British society, there were still some tasks that seemed too big for individuals to accomplish separately. Towns raised militia when needed, and the national government commanded an army and a navy and collected customs duties at ports. The States ran criminal and civil courts. But who was going to build colleges, hospitals, and bridges? As America grew there were institutions and services that society needed but that no individual had the resources to create on their own.

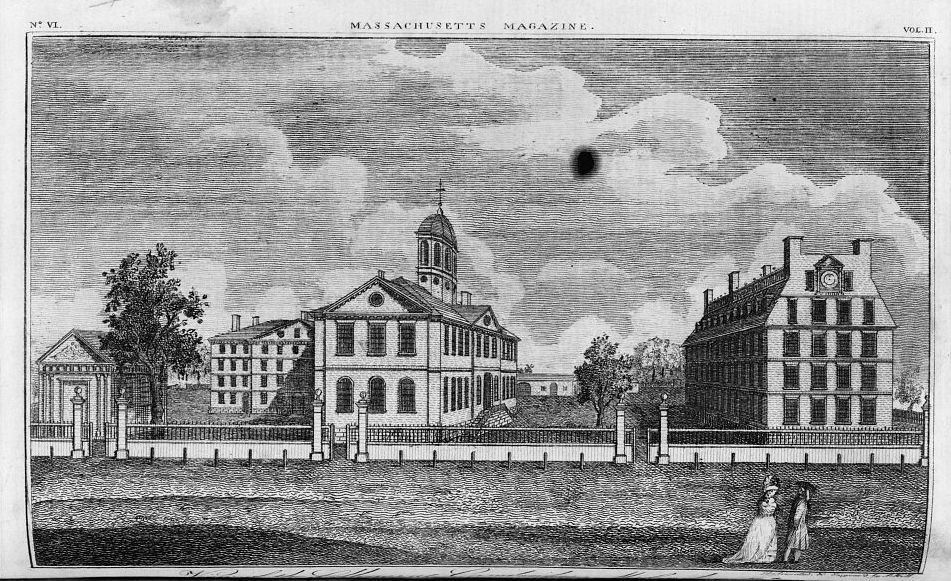

Early America’s answer to the challenge of projects too big for individual action was incorporation. Corporations during the colonial period had been quasi-public organizations given a royal charter to do a particular job. The Virginia Company and the Massachusetts Bay Company had both been royally-chartered corporations. They earned profits for their shareholders, but they also had (or at least they claimed to have) important social functions that transcended mere business. Without this social dimension, businesses—even very large ones—were normally organized as partnerships or sole proprietorships. State legislatures in early America continued the English tradition and chartered corporations to do particular tasks in the public interest. Colonial governments had begun this practice very early in American history, when the Massachusetts legislature established Harvard College in 1636 and then chartered the Harvard Corporation, North America’s first corporation, in 1650.

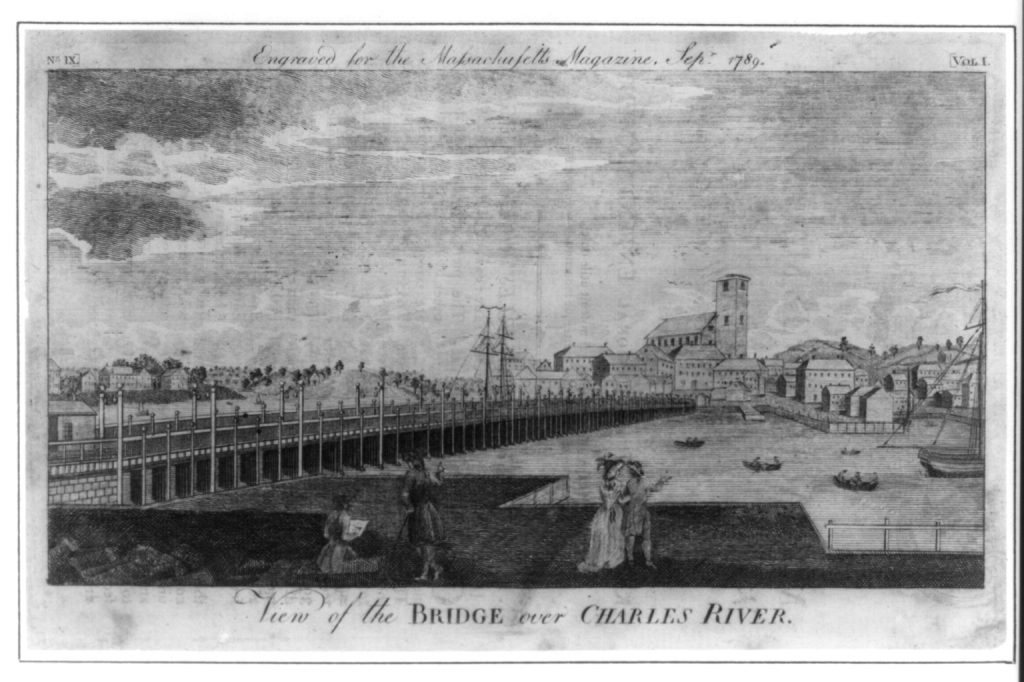

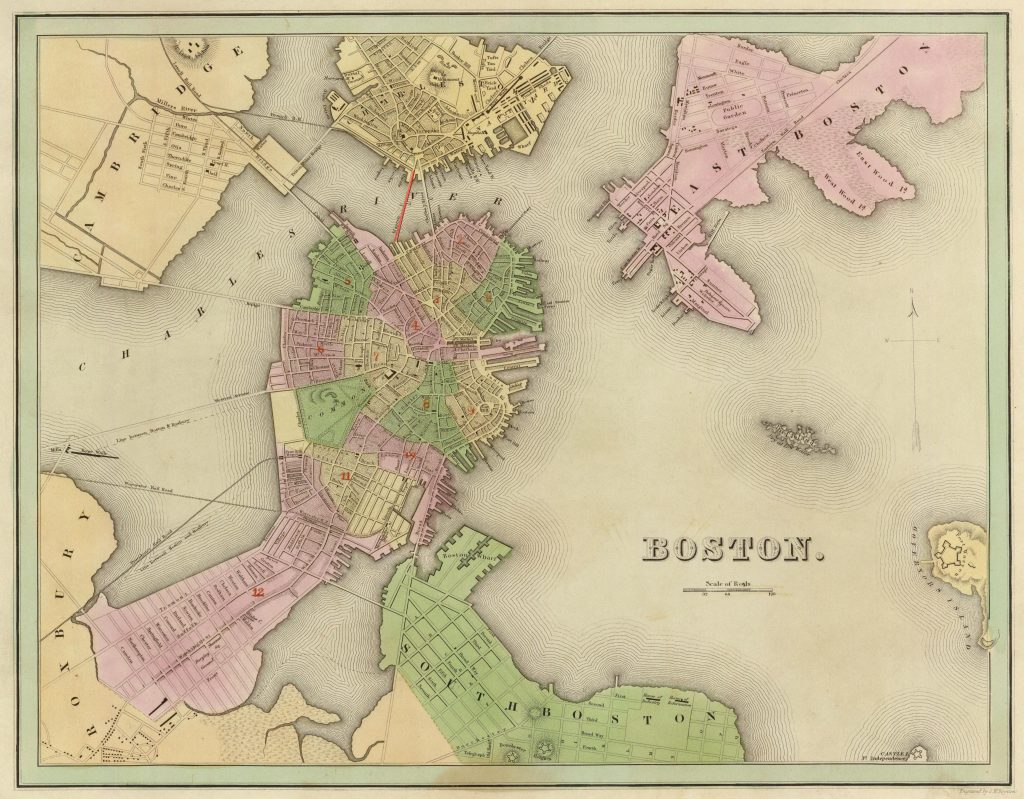

Corporate influence on the environment actually begins with this original American corporation. In 1640, Massachusetts’ colonial legislature gave Harvard College a license to run a ferry between Boston and Charlestown across the Charles River, to raise money to pay the school’s operating expenses. 145 years later, when the State of Massachusetts granted a corporate charter to the Charles River Bridge Company, to build the first bridge across the river in 1785, the new charter specified that the bridge company had to pay the Harvard Corporation £200 per year to compensate the college for the revenue the old ferry operation would lose to the new bridge.

The Charles River Bridge was a privately-operated toll bridge. Although it had originally been conceived as a public corporation that would provide a social benefit, the bridge company was wildly successful. The corporation had been capitalized at $50,000, meaning that $50,000 had been raised to build the bridge by selling shares to investors. Once built, the bridge collected $824,798 in tolls between 1786 and 1827. Although the original plan had been to eliminate the tolls once the bridge had paid for itself, the shareholders decided to continue profiting from their monopoly. So they voted to continue charging tolls and paying the profits out to themselves as dividends on their shares.

Enriching a few wealthy corporate shareholders at the expense of everyone else was not what Massachusetts legislators had intended when they had granted the corporation a charter to build a bridge that would monopolize river crossing. But although the Charles River Bridge Company had violated the spirit of their agreement with the State, it had not actually broken any laws. So the legislature chartered a new corporation, the Warren Bridge Company, to build a second bridge across the river, right next to the Charles River Bridge. Learning from their mistake, the legislature made sure the new charter specified that the Warren Bridge Company would only be allowed to collect tolls for six years or until the bridge paid for itself, whichever came first. Then ownership would revert to the Commonwealth and the bridge would become toll-free.

Outraged by the challenge to their privileged position as monopolist of foot and wheeled traffic across the river, the Charles River Bridge Company sued the Warren Bridge Company, claiming their 1785 charter had granted them a perpetual monopoly on traffic across the river. As the legislature that authorized the new bridge had expected, the Charles River Bridge Company’s revenues disappeared as travelers chose to pay the lower tolls on the Warren Bridge. The lawsuit failed in Massachusetts courts and the aggrieved plaintiffs took their suit all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In spite of hiring famous orator Daniel Webster to argue their appeal, the Charles River Bridge Company lost. The court’s decision reflected the justices’ agreement with lower court judges’ belief that the profits of the corporation and the interests of its shareholders were less important—and legally came second—to the State’s authority to charter corporations to meet public needs. Even so, the tremendous profits taken by Charles River Bridge shareholders during the period of their government-granted monopoly and their ability to push their lawsuit to the highest court signaled the beginning of a change in the way corporations viewed their roles in society and the responsibilities that went with their public charters.

Streams and Mills

Although by chartering a bridge corporation to connect Boston and Charlestown, Massachusetts had legislated a solution to an environmental problem, most early environmental issues were of smaller scale. So they were typically handled locally, by reference to Common Law. In pre-industrial America, lakes, rivers, and streams were considered community resources. This was another inheritance from feudal England, where peasants had shared fields (often owned by noble landlords) and had grazed their animals on common pastures. Early New England towns and cities were often built around a central Common which served as a meeting-place for militia as well as a pasture for grazing cattle and sheep. Like town Commons where all residents could let their animals graze, rivers, streams, and coastal fisheries were understood to be shared resources. Waterways were important means of transportation; often the only way to move people and supplies to and from remote back-country settlements. And rivers were vital food sources for many Euro-Americans, just as they had been for the Indians before the colonists arrived.

Fish such as Alewife, Herring, Shad, and Atlantic Salmon migrated from the ocean into rivers to spawn each spring. The annual run happened at a critical time of year, when supplies of food stored for winter use were often beginning to run out, and provided a common resource that was open to all. Fish from rivers and lakes were an important part of annual subsistence food supplies for many poorer Americans. The annual runs had been a major source of springtime nutrition for native and Euro-Americans for several centuries. But from the earliest period of European settlement, there were other uses for rivers that could conflict with free travel and fishing. Colonial and early American settlements used a great deal of timber for building and grew a lot of wheat for home use and for sale. So every settlement needed mills.

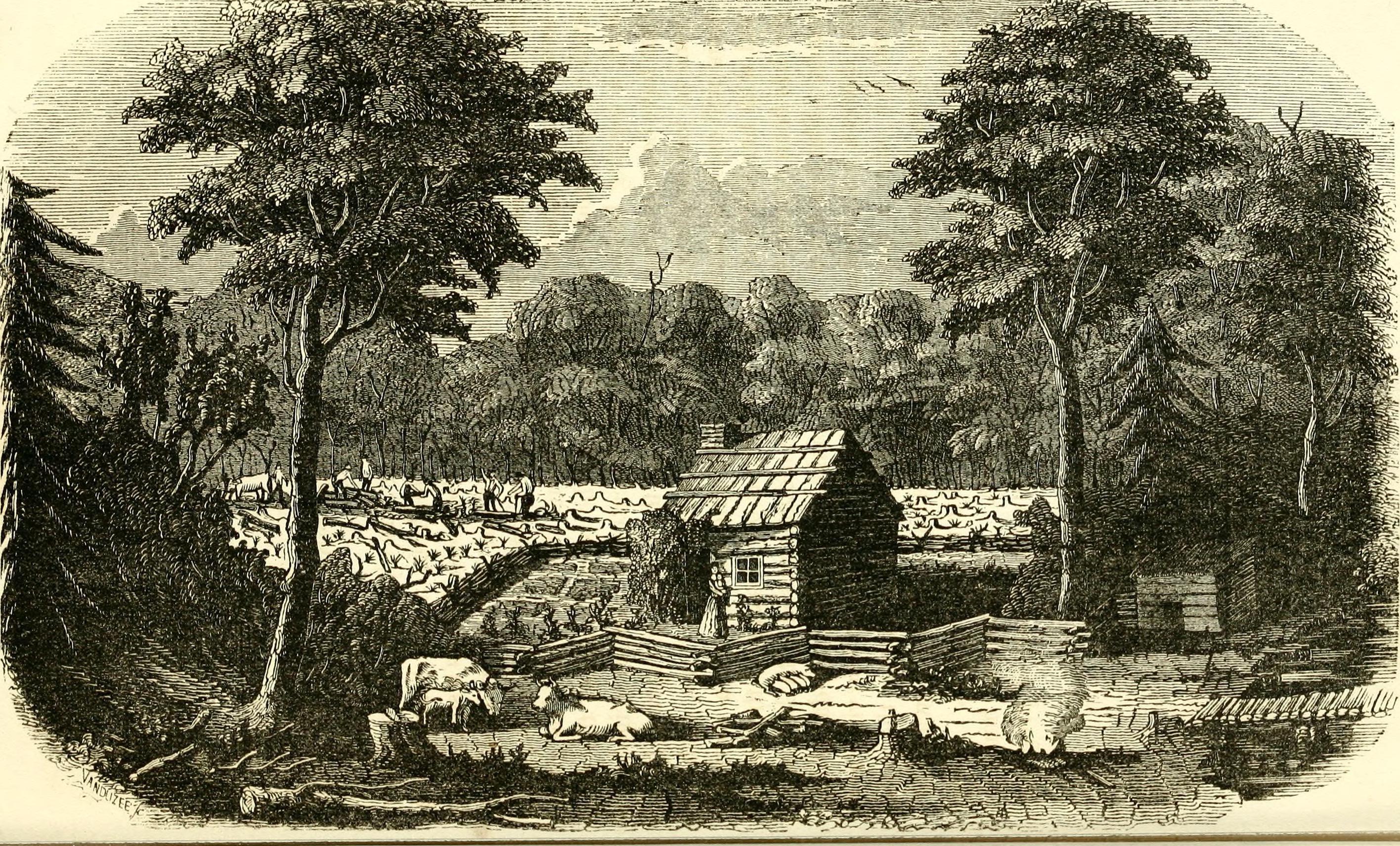

When towns were chartered in colonial times and in the early national period, organizers usually offered a reward of free land and sometimes even cash incentives to anyone willing to start a grist mill or a sawmill in the new town. Heavy mill machinery would have to be carried to the town-site and assembled, and then operating the mill required some expertise and took valuable time away from building a house and clearing fields. It made sense for new communities to offer some type of bounty to attract millers, since everybody in town would need lumber and flour, but no individual needed or could easily afford to build a private mill.

The idea that some projects were too big for everybody to do individually and that it made sense to share expensive, seldom-used tools is ancient. Today economists call these types of goods natural monopolies. Sawmills and grist mills, although they were frequently owned and run by individuals, clearly existed for the common good. Very few individual farmers grew enough wheat or needed enough lumber to justify building a private mill for their sole personal use. And no miller could afford the expense or expect to recover his investment in land, building, and machinery without the market provided by the rest of the townspeople. So millers received special incentives, and in return the mills would be open to everyone at affordable rates. There was a social contract involved in this activity that everyone understood.

The earliest homes in a new township were typically log cabins. But it’s difficult to build large structures using logs. Early town records usually show a rapid shift from log houses and barns to frame construction as soon as a sawmill opened in a town. Sawing lumber for a small project could be done by hand, if necessary. And small mill-wheels could be turned by animals like horses or oxen. But producing enough lumber for a large house or barn or driving a large millstone required much more power. So any township site that included a stream with a decent fall of water was considered a prime location for a settlement.

The streams and rivers that early American millers used for power did not belong to them. At some township sites, a river’s volume and fall were large enough that a miller only needed to divert a little water into a channel called a millrace, to power the mill’s wheel. In other places, a partial or a full dam was required to generate enough force to turn a wheel. When a miller needed to build a dam and change the natural flow of the stream, he was responsible and legally liable for the effects of his dam on people upstream and downstream from him.

Dam Breaking

With so many people depending on rivers for transportation, food, irrigation, and drinking water, changing a river’s flow was often controversial. A mill pond might flood a farmer’s field upstream or cut off water to a farm or another mill downstream. A dam might prevent fish from running upstream to their spawning grounds, endangering not only one year’s food supply but future fish populations. The issue was considered so serious and the stakes so high that it was actually legal in early America for people who felt they had been injured by a mill’s dam to go ahead and break the dam. If their farmland had been flooded or if the flow of water to a downstream farm or mill was cut off, the injured party could break the dam and restore the flow of water while the dispute was being settled in court. People were legally entitled to restore the stream to its original condition until society decided the fairest solution for everyone. The common law approach to water rights was so ancient that it was expressed by a Latin phrase that had been used in the Roman empire two thousand years earlier, aqua currit et debet currere, ut currere solebat: water flows and ought to flow, as it has customarily flowed. Any human-made change to a river’s natural state could be challenged, because everyone had equal rights to the river.

In addition, mill dams in early America were often seasonal structures that would be partially broken each year to allow freshets of snowmelt to pass by without flooding and damaging the area. Dams were also often taken down to allow the fish to run upstream in the spring. And flour milling or sawing lumber was seasonal work in many small towns, so mill races and ponds did not need to be permanent and always in use.

In early American towns, mills and their dams were well-understood technologies that had existed for many generations, authorized by the townspeople and used for the common good. The mills and their technology existed in a social system that emphasized their status as shared resources for community use. There was a reciprocal give and take between people who had different interests in the society, both in social customs and in common law. Millers were given special incentives to move to new towns and help them grow. In return, they were responsible for keeping the mills running and available to everybody, and for responding to their neighbors when they changed the flow of streams in ways that caused problems. In return, many millers enjoyed what amounted to a local monopoly on sawing wood and grinding flour. Although other millers were rarely prohibited from opening competing mills, there was only so much need and there was only so much water power. But there were always new towns needing millers, so common customs and common sense were effective ways to regulate early mills.

Textile Factories

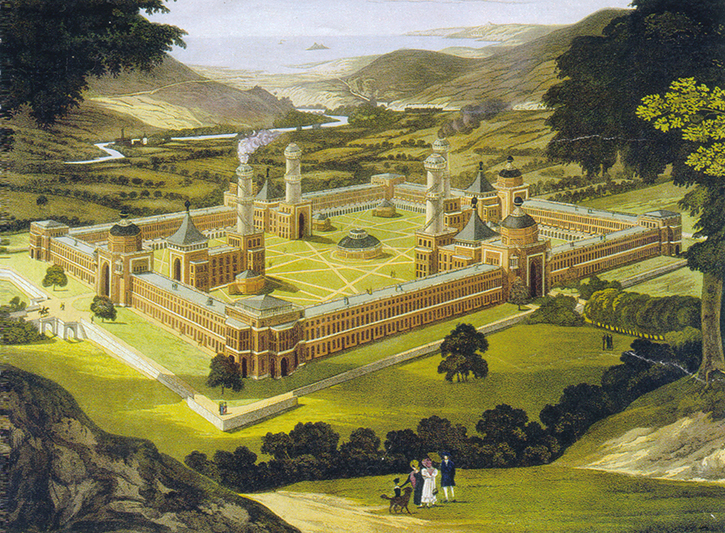

As new technology was developed and as the pace of change accelerated, this common law, common-sense social contract began to break down. One of the specific events that accelerated this change was a visit to Scotland in 1810 and 1811 by a pair of prosperous Boston merchants named Nathan Appleton and Francis Cabot Lowell, who toured the textile mills at New Lanark. These woolen mills on the River Clyde southeast of Glasgow were run by an innovative industrialist named Robert Owen, and were the largest completely water-powered mills in Great Britain. Owen’s textile operation employed so many people that the company had built an entire community around the factories to house the mill-workers and their families.

Robert Owen and his partners had bought the mills in 1799 from David Dale, Owen’s father-in-law. Sensitive to the negative social changes that industrial growth had brought to other parts of Britain, Owen built schools for the children of his workers and social organizations for the families. He put an end to the long-standing custom of forcing workers to buy only from the company store and tried to make New Lanark a real, living town. Owen’s partners had objected to his philanthropy, claiming that healthy, happy, well-educated workers did not really boost the bottom line. Rather than fight with them, Owen simply bought his partners out.

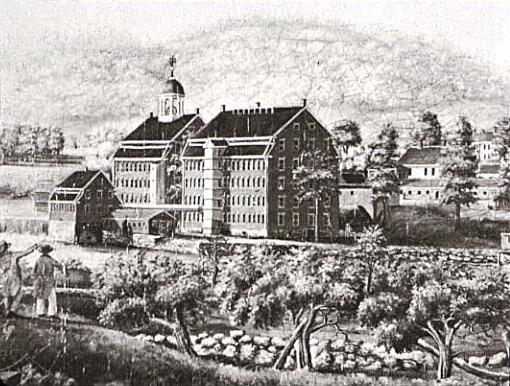

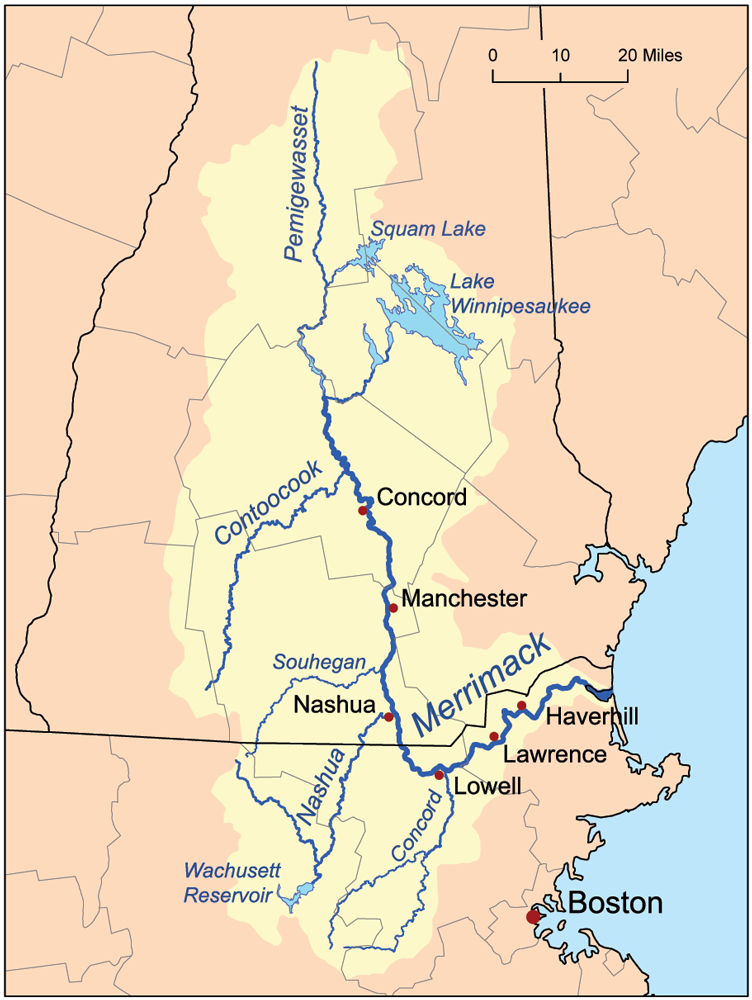

Appleton and Lowell returned to America and immediately began the Boston Manufacturing Company (BMC) in 1813 on the Charles River in Waltham, Massachusetts. At that time there were already twenty-three other mills on the Charles, but the BMC was something different. Appleton and Lowell’s mill was a completely water-powered textile factory on the model of New Lanark. The Boston Associates also followed Owen’s example in social engineering, and began building complete industrial cities in New England. Nashua, Manchester, and Concord on the Merrimack River grew from small agricultural towns to large textile cities. Lawrence and Lowell were built from the ground up as textile factory cities. Young people throughout the region, especially the daughters of farm families, flocked to these new industrial centers for the relative independence of factory employment. But the Boston Associates not only created cities and filled them with industrial wage workers. They helped change the way all Americans understood their environment.

The BMC’s textile mills employed mostly young women, aged 15 to 30. Between 1840 and 1860, the number of mill girls working in the Massachusetts textile industry rose from about ten thousand to over a hundred thousand. For context, the population of New England’s largest city, Boston, was about 93,000 in 1840 and 178,000 in 1860. By 1848, Lowell was the largest industrial city in America.

When the BMC opened their first mill, only seven out of a hundred Americans lived in cities. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the nation’s urban population was approaching twenty percent, with a lot of help from the mill girls. Some of the women were immigrants, but most had come from farm families. A hundred thousand young women moved to the city to work twelve hours a day in the textile mills. In spite of harsh work conditions and low pay, many of these women were experiencing personal freedom for the first time, and liking it. Most never went back to the countryside. As cities like Lowell, Lawrence, and Manchester grew around the mills, they created a new American population group, the urban wage-worker. The mill girls and other factory workers lived a different life and had very different concerns from those of the families they’d left behind in the countryside. Although they joined the new labor movement and were often critical of the mills they worked in, the mill girls’ lives became tied to the wellbeing of the industry that employed them.

Too Big to Fail

The creation, financial viability, and even the continued existence of new industrial cities like Lowell depended completely on the Boston Manufacturing Company’s profitability. Prosperity for Lowell’s citizens relied on the success of the business that paid their wages. The BMC was too big to fail. Over time, it was only natural for the city’s dependence on its creator and main employer to transform the way people understood the public good.

At the height of its power, the BMC controlled the entire Merrimack River from its source in Lake Winnipesaukee to its outflow in the Atlantic. The Boston Associates decided how much water would be let out of the New Hampshire lake and built dams to control the flow along the entire river so that all of the Merrimack’s water power was available to power the turbines of the BMC’s textile factories. River transportation, fishing, and all other competing uses of the Merrimack’s water were considered secondary to the BMC’s water-power requirements.

How did this happen? How did one corporation gain control over what only a generation earlier had been universally understood as a common good, a shared resource open to everyone? There was no bill presented in Congress. No elected representatives voted for this change in social priorities. If the issue had been debated in the legislature, things might have gone differently. Instead, the decision to grant control of one of the region’s major natural resources to a single corporation happened very slowly and under the radar, through a series of legal changes stemming from court decisions and reinterpretations of contract law.

It is important to remember that the public benefited from early corporations. The social good provided by natural monopolies explains why communities chartered corporations and allowed them to inconvenience or even injure the interests of individuals, in the same way towns allowed their local millers to occasionally flood a field, as long as the miller compensated the injured farmer for the loss. It was an issue of the public good coming before the private good. And corporations had public responsibilities: in exchange for special treatment (usually some form of a natural or legislated monopoly) the corporation was expected to act in the public interest. How did that all change between then and now?

The first step was a gradual shift in the interpretation of the mill laws. In every state there were laws that regulated how disputes over water rights would be addressed by the courts. Before the nineteenth century, the common law approach to water rights had been expressed by that Latin phrase, “water flows and ought to flow, as it has customarily flowed.” In Massachusetts, the mill laws dated from 1713 and they only allowed the property of other landowners to be compromised by mills “for the publick good.” But as time went on and case after case was brought before Massachusetts courts, judges began to rethink the phrase public good. As the users of water power grew from village grist and sawmills to textile factories, the judges began to see industry itself as a public good. By the time the Boston Associates were building entire cities from the ground up and providing employment that supported hundreds of thousands of Massachusetts families, it was difficult to argue there wasn’t a public interest in the BMC’s success, even if the profits of the enterprise were restricted to just a few shareholders.

Because textile factories used water power, even if it was on a much larger scale, Massachusetts judges tried to regulate them using mill laws that had been designed to settle the types disputes that applied to village sawmills and grist mills. Not only did the scale of the BMC’s operations make this legal treatment inappropriate, the judges lost sight of the fact that the Boston Manufacturing Company was a private corporation operating for the profit of its shareholders, while village mills had operated for the public good. Thus, through a series of judgments, mostly in lower courts, the BMC was allowed to redefine its relationship with society and with the environment. As a result, so slowly that almost no one noticed at the time, the nature of corporations themselves changed and the idea of a social contract for the public good was lost.

The Boston Associates were not the first textile operators in New England. When Samuel Slater had opened America’s first textile mill in 1793 on the Blackstone River in Pawtucket Rhode Island, he had organized his company as a partnership. But as business opportunities grew, the idea of incorporation changed. Between 1800 and 1809, only fifteen corporate charters were given to Massachusetts manufacturers. In the next ten years, the number jumped to 133. Corporations gradually stopped presenting themselves as public-spirited foundations operating institutions such as hospitals and colleges in the public interest. They became more like the business corporations we would recognize today, whose missions are clearly understood to be building share price and returning a profit to their shareholders. But because incorporation had once been about providing public services in exchange for special privileges, the new corporations frequently retained their special privileges, even after they had stopped providing public services.

Evading Responsibility

Along with the legislated monopolies many enjoyed, one of the special privileges corporations coveted was limited liability. Rather than being held responsible for all the damages that might be caused by a potentially dangerous business such as a textile mill, shareholders only risked the amount they invested. This not only helped firms raise more money, it allowed businesses to take bigger risks, since the worst that could happen in case of a disaster would be that the company would be forced to declare bankruptcy. Shareholders would lose only the money they had spent to buy company shares; their other assets could not be taken to compensate the victims of their company’s risky behavior.

Once again, it is important to remember that the reinterpretation of business law and contracts that allowed these changes to happen was not done by elected representatives in legislative debate, but by lawyers and judges who were often friends, relatives, and investors of the new textile industrialists. They shared not only an interest in the mills’ success, but a cultural orientation that made it easy to see the the textile industry itself as a public good to be protected.

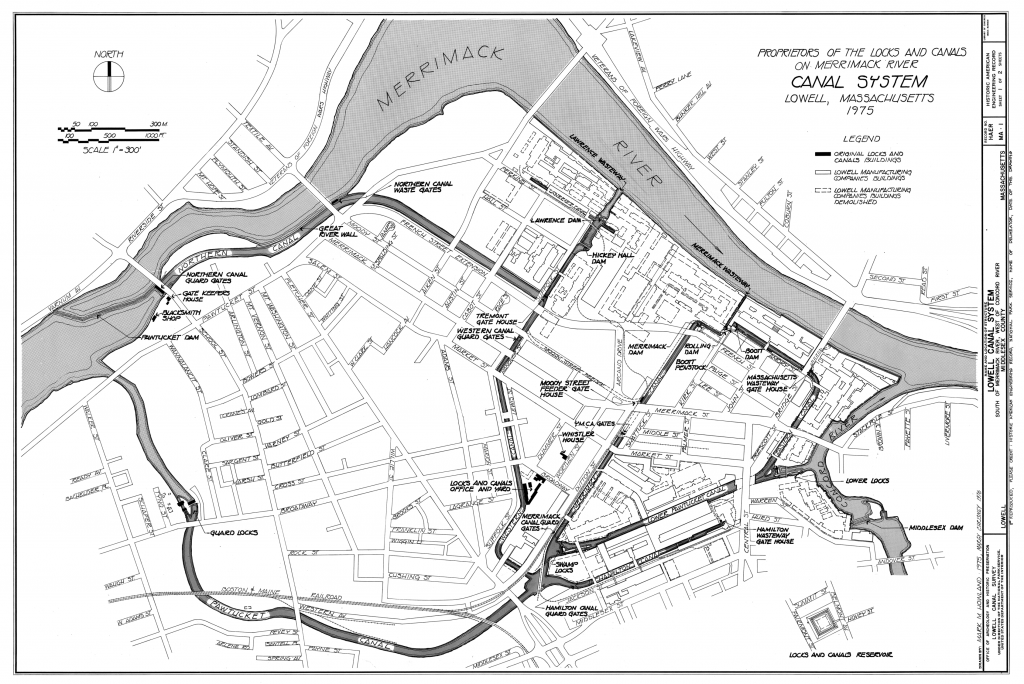

The most environmentally-damaging change caused by the New England textile industry, in the long run, was the gradual elimination the idea of common resources. First, legal reinterpretations separated the old mill laws from an idea of common good and used them to arbitrate property disputes of people who owned land beside rivers. Next, lawyers working for the textile corporations and judges sympathetic to their interests subverted the common law understanding of equal rights to water resources and shared responsibility for their upkeep. Finally, industrialists and their allies in the courts actually eliminated the idea that waterways were a community resource, so the flow of the river could be treated as a commodity that could be bought and sold by individuals. They did this by creating a water power company called the Proprietors of the Locks and Canals (PLC) which invented a concept called mill-power, that they sold to the textile mills.

Mill-power was an accounting tool: a number that measured the work that could be done by river water pushing the textile factories’ turbines. Although it had been a long-standing tradition that running water should never be considered private property, mill-power evaded that restriction. It was just a measurement invented by the PLC for accounting purposes. While the courts might have rejected the sale of the river by one corporation to another, there were no laws preventing the PLC from selling mill-power to BMC factories along the Merrimack River.

The immediate effect of reducing the physical Merrimack River to nothing more than an input into an accounting calculation was that the rest of society (who were unaware this was happening and in any case had no interest in buying mill-power) was no longer involved in these transactions. Society had not been prevented from participating, but the sale of the river had been hidden from the public and transacted in such a way that it made no sense for them to participate. But as a result, everyone who did not own a turbine suddenly lost access to the river and no longer had any say in its use. Worse, once a market price had been established even people with riverside property could be bought out, and by accepting a settlement payment could be effectively silenced forever.

There were never any bills introduced into the Massachusetts or New Hampshire legislatures, allowing citizens to debate whether control or ownership of the Merrimack River should be handed over to the corporation begun by Nathan Appleton and Francis Cabot Lowell. Appleton himself was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1842, and although Lowell died in 1817 at age 42, his son Francis Cabot Lowell Jr. became a U.S. Congressman and a Federal Judge. In 1850, the BMC’s textile empire earned $14,000,000 in annual revenue, which was half the combined Gross Domestic Product of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. BMC profits were high because they were the largest supplier of cotton fabric in the market and because they had been able to control their costs by keeping the mill girls’ wages low. After an unsuccessful strike, mill workers formed the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association in 1845 to fight for higher wages, lower rents in company-owned boarding houses, and a ten-hour day. A Legislative Committee looked into the mill girls’ demands and decided it was not the state’s responsibility to set work hours. Another important source of BMC profits was the low price of raw cotton, which of course was produced on Southern plantations by people who didn’t have to be paid at all.

When the PLC and the BMC gained complete control, shad and the salmon were no longer able to swim up the Merrimack River to breed. New Englanders lost a food source that had sustained generations every spring. The BMC was sued for damages by fishermen and residents along the river. In 1848 the corporation settled these lawsuits with payments totaling $26,000 to the plaintiffs. In return for a one-time cash payment, the plaintiffs and their descendants relinquished all future claims against the corporation. In other words, for $26,000 the destruction of a major New England fishery was settled once and for all. The fish were gone for good, but the only people compensated were a handful of plaintiffs in a single lawsuit. When the case was settled the issue was considered permanently closed. No one else would be allowed to sue for damages in the future, even though a resource that had always been available for common use had disappeared. This result illustrates not only how much power goes along with controlling a revenue stream worth half the economy of two states, but also how difficult it can be setting a one-time economic value on long-term environmental changes.

Was the destruction of the habitat of the salmon, shad, and of the other animal species that depended on those fish worth $26,000? Was the elimination of a major seasonal food source for rural working-class people in the region worth $26,000? How long would it take until people had spent $26,000 buying food to replace the fish they could no longer catch in the river? No one knew, because the questions were never asked. The public had become divided into groups that no longer shared common interests. Whether there were fish in the river was not a question that particularly concerned factory employees or many other residents of cities like Manchester, Lowell, or Lawrence, whose lives now revolved around urban wage-workers’ concerns such as work hours, rent in company dormitories, prices at the company store, and factory conditions. For the first time in America there was a population of working people that was permanently separated from direct contact with the land, and from the people who lived and worked on it. As we will see in later chapters, the separation of the American working class into urban and rural groups with different concerns had a profound impact on both social justice and the environment.

Externalities and Alternatives

In addition to privatizing the Merrimack River, the textile industry polluted it. In a sense, it did not matter that the fish could no longer run up the river. They would not have been able to survive the water and residents would not have been able to eat them. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the BMC’s mills and bleacheries were producing over fifty million yards of colored and printed fabric annually. The residues from production processes included dyes, bleaches, sulfuric acid, lime, and arsenic. Since there was no law against it, these residues were all dumped into the river. It was a widely-accepted belief that the running water of streams and rivers purified waste thrown into them, although no one really understood why. It is actually true that the microorganisms in water can digest and neutralize a reasonable quantity of (especially organic) waste. Unfortunately, the mills and the new cities the BMC had created overwhelmed the Merrimack’s ability to renew itself. Some mills actually discovered that river water could only be used for dying dark-colored fabrics because the water was too stained to use on whites and lighter shades.

Fish were regularly killed in large numbers up to two miles downstream from the mills’ outlets. A state commission advised the public against drinking river water downstream from Lowell on the Merrimack and pronounced the Nashua River unfit for drinking along its entire length. But the commissioners, pressured by their industrial sponsors, concluded that cleaning up the river or preventing further contamination would be too expensive, and recommended taking no action.

Although the Lowell mills and their canal power system had been meticulously engineered, the same could not be said for the city the BMC had created. Lowell grew haphazardly. As late as the 1870s, the city had no general sewage system. Cesspools leaked into ground water, contaminating the wells scattered throughout the city that provided Lowell’s residents with drinking water. Deaths in Lowell from typhoid fever, a water-borne disease, peaked in the 1870s and exceeded typhoid deaths in Boston through the end of the century, even though by 1900 Boston had five times Lowell’s population. In 1878 the Massachusetts legislature was forced to respond to public pressure, and passed “An Act Relative to the Pollution of Rivers, Streams, and Ponds Used as Sources of Water Supply.” Ironically, bowing to industry pressure, the lawmakers exempted the Merrimack River from the law’s pollution-control provisions.

The New England textile industry is usually remembered in history books as an enormous achievement. The Boston Manufacturing Company was indeed wildly successful, and created a model for American industrialism. Some of that praise is deserved. Nathan Appleton and Francis Cabot Lowell, and the men who led the BMC after them, pioneered industrial organization and built cities for New England and fortunes for themselves. But often when we celebrate progress we forget the cost.

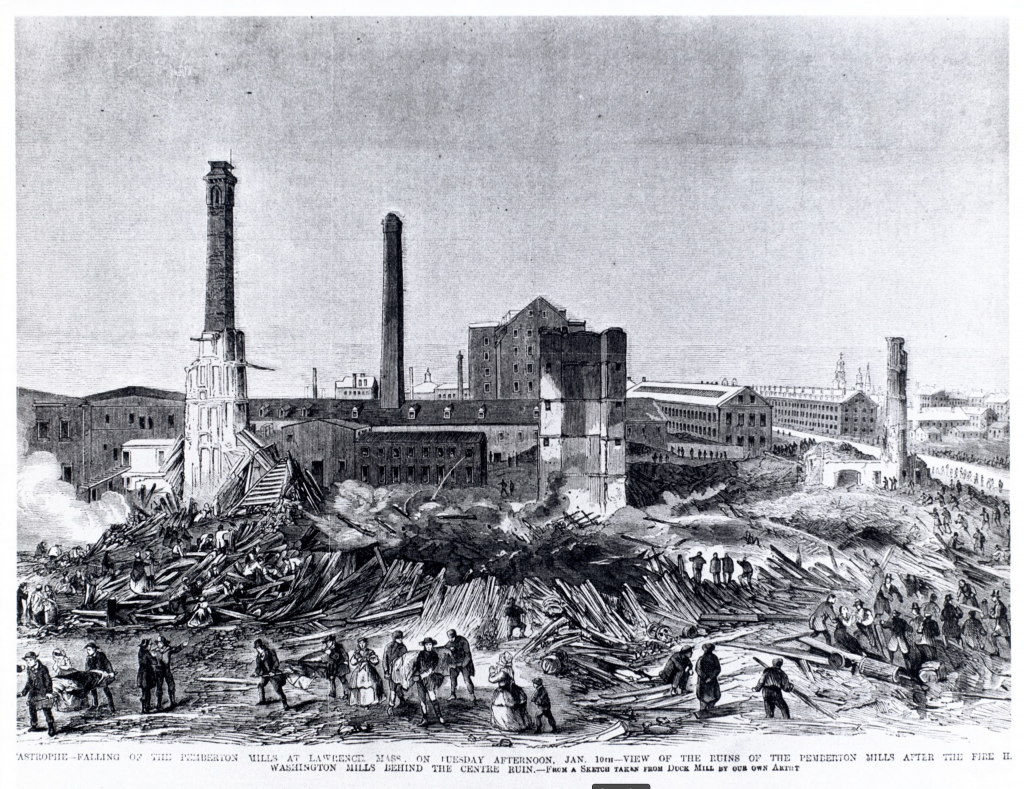

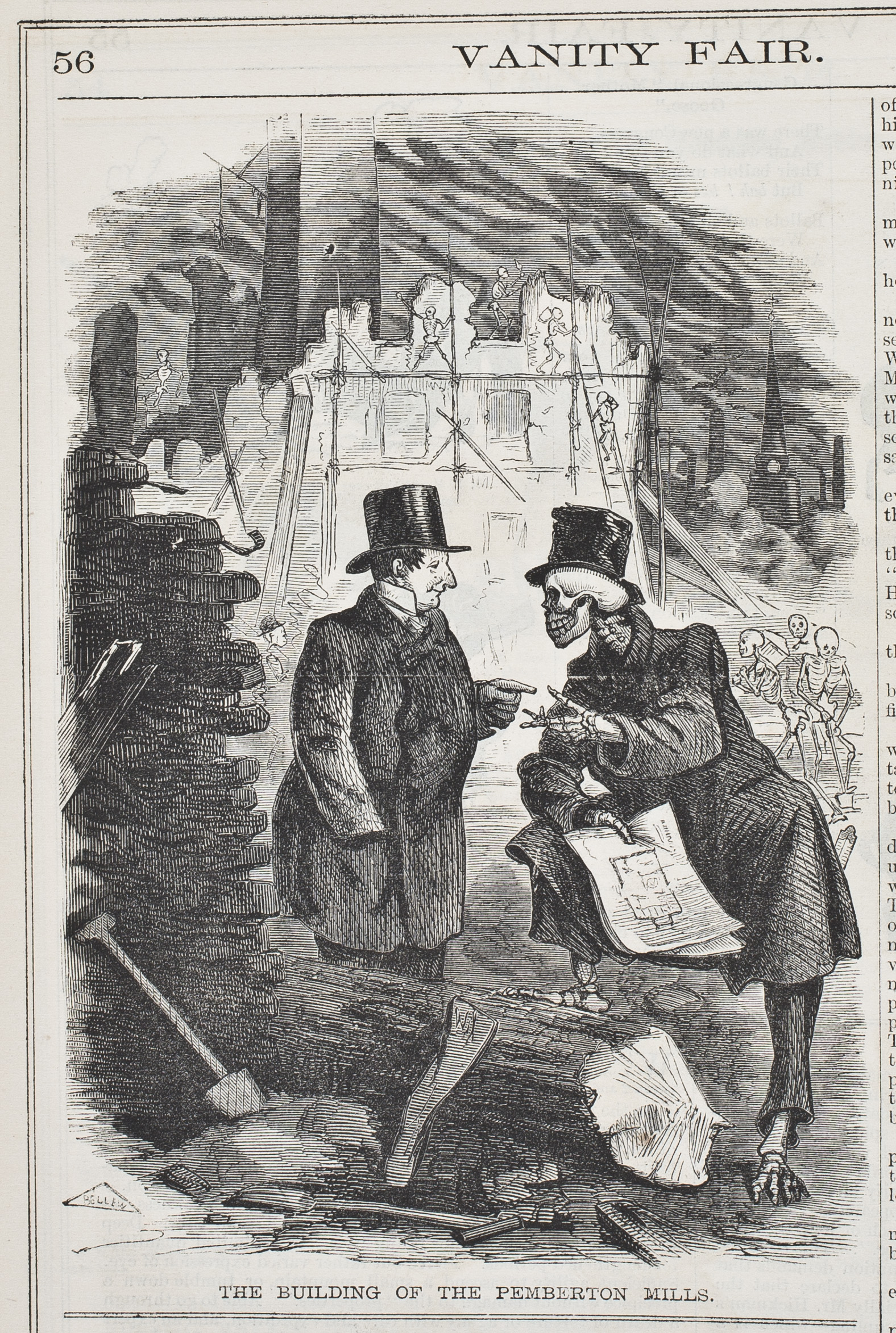

Water pollution was not the only danger the textile industry posed to the public, however. In January 1860, the five story Pemberton Mill in Lawrence collapsed with about 800 workers inside. The firm had been sold recently and its factory building filled with newer, heavier machines. 700 looms had been updated, and a business that had been near failing seemed to have been turned around with great success. The collapse killed 145 workers, mostly women, and left 166 seriously injured. In an investigation after the accident, the collapse was declared the result of preventable factors such as the overloading of the floors with heavy equipment, overcrowding, and even gross negligence in the original construction of the mill buildings. The disaster rallied some activists in the fight for workplace safety. But there were never any consequences for the people who owned and ran the factory. Life just went on. The Pemberton Mill’s owner bought out his partner and built a new factory on the site of the old one. After his death, the new factory was inherited by the owner’s sons. The building is still a prominent landmark of Lawrence.

Avoidable disasters such as the Pemberton Mill’s collapse add human costs that are difficult to quantify. But even setting these considerations aside, how much of the success and profit attributed to the Boston Manufacturing Company and the other mills of the Merrimack River Valley was the result of not having to count the costs their operations imposed on the environment and on people like New England mill girls and Southern plantation slaves who had been written out of the equation? In a sense, the privatization of profits and socialization of costs that allowed the textile industry to dominate the New England economy was just another special privilege given to a corporation by society, in spite of the broken social contract that no longer asked the corporation for anything of comparable social value in return. If economists and historians accounted for all the social and environmental costs, then how profitable was the Boston Manufacturing Company really? We will return to this idea, which economists call externality, in later chapters.

The development of the New England textile industry illustrates how subtle, often unnoticed changes in laws and customs accumulated over time to create the world of global corporatism we live in today. Through a combination of becoming too big to fail and slowly changing the way the law understood the concepts of common resources and social responsibility, corporate industrialists turned the waters of the Merrimack River, one of New England’s most valuable natural resources, into a steady flow of profits for the BMC and its owners. Changes begun in the New England textile industry lead directly to the ways we understand corporations, shared resources, and social responsibility today. But we should never conclude that the way things ended up was inevitable. The present is the result of hundreds of decisions, big and small, that people made along the way. To illustrate that point, we return to the beginning of this story, to Robert Owen.

Robert Owen organized a modern industrial city from the ground up in New Lanark. Appleton and Lowell learned from Owen that social engineering on a grand scale was possible, and they returned to New England inspired and followed Owen’s example in Waltham and then along the Merrimack River. What did Owen do after meeting Appleton and Lowell? Owen became the father of the British cooperative movement. In addition to being a wildly successful entrepreneur and capitalist, Owen promoted a system of corporate welfare that his critics, then and now, called socialist. Owen, however, embraced the term.

Robert Owen tried to improve the society his father-in-law had created around the textile factories, by building schools and by taking care of the health and welfare of his workers. New Lanark became a model of humane industrialism and socially responsible urban planning. But that wasn’t enough for Owen. After his success in Scotland, Owen wondered how much farther he could go. So he sold his interest in New Lanark and moved to Indiana, where he founded a cooperative community called New Harmony. Like Appleton and Lowell, Robert Owen seems to have experienced an “Aha!” moment when he realized how much power he held to change society and perhaps even to change people. But unlike the Boston Associates, who built a textile empire that made them millionaires, Owen chose to do something different with that power. Robert Owen’s decision suggests that as hard as they sometimes may be to see, history often comes down to a series of human choices.

https://youtu.be/lBXHiilQLMU

Further Reading

Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton, A Global History. 2014.

Benita Eisler, ed., The Lowell Offering: Writings By New England Mill Women (1845-1940). 1997.

Morton Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law, 1780-1860. 1977.

Ted Steinberg, Nature, Incorporated. 1991

Media Attributions

- Wayside_Grist_Mill © Dudesleeper adapted by Dan Allosso is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 3a45717v © Samuel Hill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3a24977u copy © Samuel Hill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Warren_Bridge_-_Boston-Charlestown_-_1 © Map by Thomas G. Bradford, engraved by G.W. Boynton is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pioneer © O. Turner is licensed under a Public Domain license

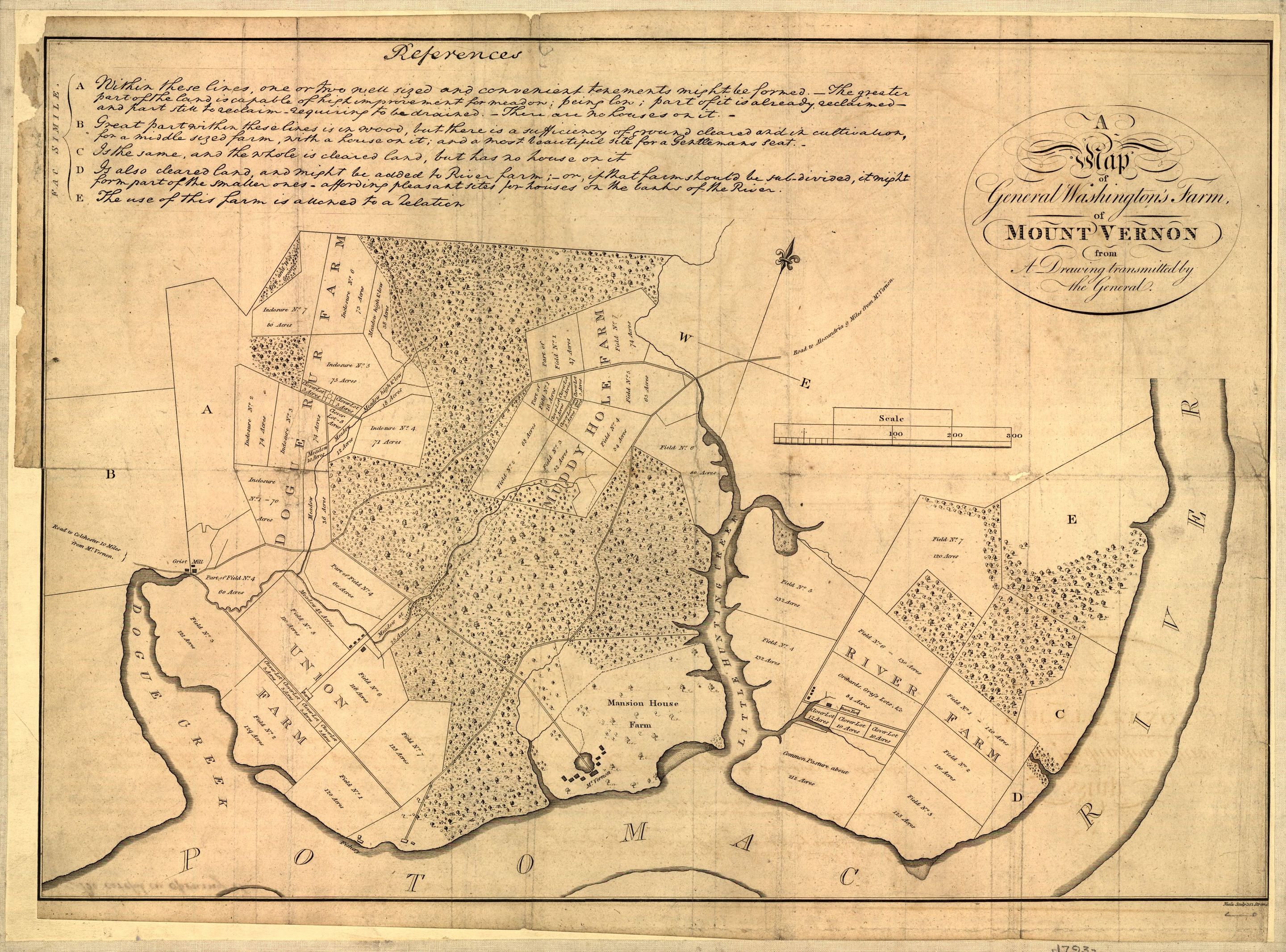

- 2880px-Gwash_map02 © George Washington is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3191883_da59af55 © Walter Baxter is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- New_Lanark_buildings_2009 © mrpbps is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Boston_Manufacturing_Company © Elijah Smith is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Merrimackrivermap © Karl Musser is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- acf8e511d20d2f1f6009c2c974c1b394 © E. A. Farrar is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pawtucket_slater_mill © dougtone is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 01830v © Lewis Wickes Hines is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Line_shaft_and_power_looms_at_Boott_Mills,_Lowell,_Massachusetts © Marcus Cyron is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 1975_map_of_canal_system_in_Lowell,_Massachusetts © National Parks Service is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Boston_Manufacturing_Company_mill_complex,_Waltham,_MA_-_1 © daderot is licensed under a Public Domain license

- D11023.jpg © Winslow Homer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pemberton © Frank Leslie is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 9c520918366467e2db21afbef8ceb0da © Vanity Fair is licensed under a Public Domain license

- New_Harmony_by_F._Bate_(View_of_a_Community,_as_proposed_by_Robert_Owen)_printed_1838 © F. Bate is licensed under a Public Domain license