10 Wilderness and Country Life

As discussed earlier, until quite recently most Americans lived on farms or in villages and small towns surrounded by countryside. The idea of a vanishing American wilderness developed at about the same time and for similar reasons as concern about country life, during a period when most American intellectuals and political leaders lived in cities and had lost a daily personal connection with their environments. While their interest in the land and the lives of rural people was usually genuine, the privileged, urban lifestyles of the people who became known as Progressives often colored their thinking about the wilderness and about life in the country. In this chapter we will examine the ideas about nature and life in rural America that have helped shape public policy and our own understanding of the environment in modern America.

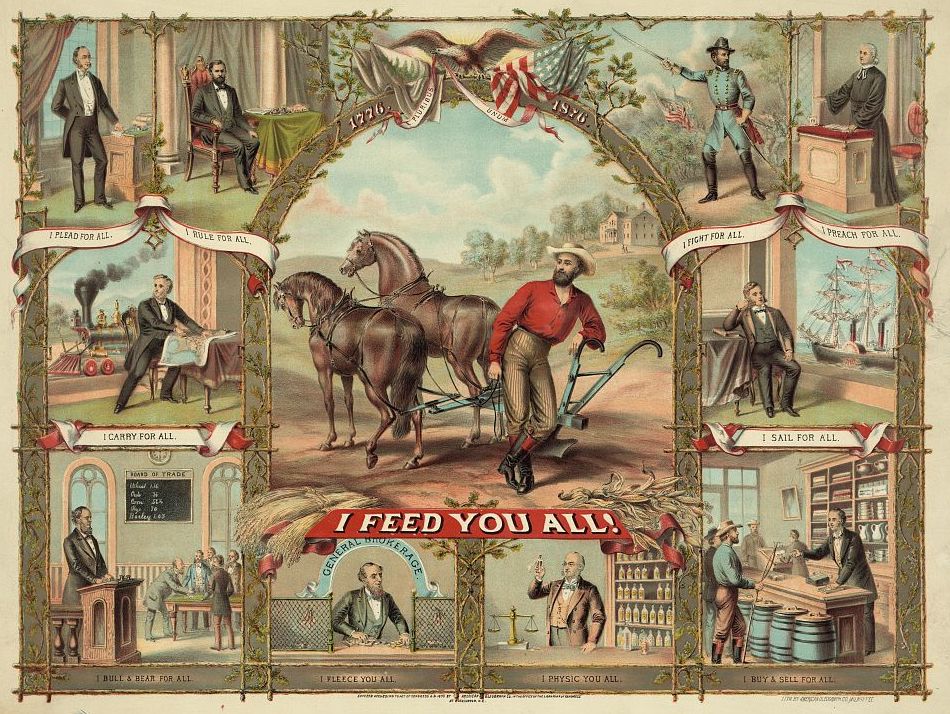

As we have seen, farmers, trappers, lumberjacks and others working on the frontier were parts of global commercial networks from the very beginning of European activity in the Americas. But new technologies such as steamboats, railroads, and rolling mills upset relationships between producers and consumers in this global commercial web. During the nineteenth century, for example, American farmers increasingly found themselves negotiating not with the people who ate their food, or even local millers or grocers; but with highly capitalized, well-financed industrial mills, stockyards, and food manufacturers. When many small producers negotiate with just a few large buyers, the buyers tend to hold most of the power.

The economic power of the corporations who were their suppliers and customers was not the only problem facing farmers. Railroads that had been built with government loans and with generous grants of public land became the farmers’ only choice for transporting their produce to markets in cities such as Chicago and Minneapolis. Although heavily subsidized, the railroads were run as private, for-profit corporations and were allowed to manage their own schedules and set their own prices. When farmers discovered that big corporations, including the food processors they sold their harvests to, were paying the railroads much lower freight rates, they felt they had been betrayed not only by the railroads, but by the politicians they believed the railroads controlled.

Following the end of the Civil War in 1865, a new wave of migration began and thousands of families moved westward to farm in states such as Kansas, Iowa, Minnesota, and the Dakota Territory. The population of Kansas grew from about 365,000 to over a million in the 1870s, and Nebraska also tripled in size. Unfortunately, grain markets did not offer these new farmers the lucrative opportunity they had anticipated. A short post-war recession lasting from 1869 to 1870 was followed by the Panic of 1873 and then by the Long Depression of 1873-1879, which until the 1930s had been known as the Great Depression. Prices for farm commodities were driven down and remained low for decades. Facing increased competition in commodity markets and continuing high rates from the railroads, farmers sought a way to improve their chances of financial success.

Farmers were well aware of their numerical advantage over railroad capitalists and corporate shareholders, and they organized to turn their numbers into political power. The Knights of Labor, one of America’s first unions to open its membership to workers outside a particular trade or specialty, was organized in 1869 to promote the ideal of the unity of all producing groups. Agricultural organizations included the Granger movement, the National Farmer’s Alliance, and the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance and Cooperative Union, which combined in 1875 to form the Farmers’ Alliance. In 1890 the Farmers’ Alliance joined with the Knights of Labor, which had become a leader of the growing urban labor movement, to form the People’s Party.

The People’s Party, also known as Populists, was ultimately unsuccessful in its attempt to establish a permanent third party and end the two-party system in American politics. But Populist ideas and proposals influenced the policies of both parties. The People’s Party platform called for a graduated income tax, direct election of Senators, civil service reform, and an eight-hour workday. Many Populists also advocated government control of “natural monopolies” such as the railroads, telegraphs, and telephones. These services were provided by the public sector in nations throughout Europe, Populists argued; often more efficiently and more equitably than in America. Although the People’s Party did not convince the majority of American voters to support these causes, their observations about the efficiency and quality of publicly-provided services like European railroads are as valid today as when they first made them.

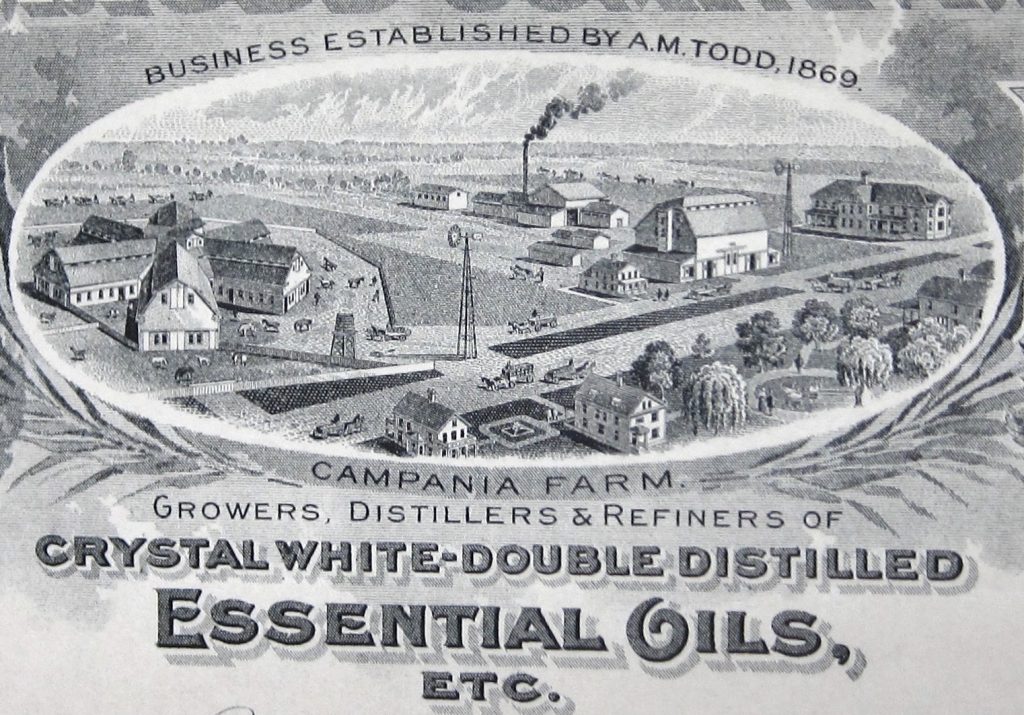

Although many Populists came from rural backgrounds, they took full advantage of the travel and communication opportunities provided by technological change. For example, Albert May Todd was a Michigan farmer’s son who built an international business in the last quarter of the nineteenth century processing and marketing peppermint oil. Based in Kalamazoo Michigan, Todd established several large-scale farms with their own company towns and agricultural research stations. The A.M. Todd company became the world leader in peppermint oil, and its owner decided to try his hand at politics. Like Robert Owen, Todd was both a successful capitalist and a committed socialist. He financed community centers in his rural company towns where workers could hold meetings, concerts and dances. Todd visited Europe regularly to promote his business, but he also devoted a great deal of time to studying European politics, especially events such as the Swiss referendum that nationalized the alpine country’s railroad system. Todd was also an art-lover who bought paintings and sculptures in Europe that he donated liberally to libraries, colleges, and even the public schools of Kalamazoo. Todd was elected to Congress in 1896 and spent his time in Washington arguing against the corrupting influence of monopolists and the railroads on American government. Later, Todd founded The Public Ownership League of America to advocate for municipal ownership of public utilities and nationalization of the railroads. Members of the League’s board of directors included the former governor of Illinois, the president of the United Mineworkers Union, and Chicago social reformer Jane Addams.

The activities of rural Americans like Albert Todd show that the ideas of Populist reformers were often informed by the most inclusive national and even international networks. Rural reformers had as much access to information and often had as much influence as their urban counterparts. Populist issues were gradually adopted by mainstream politicians, which drew many members of the People’s Party back into the two major parties. Populists should be given credit for the fact that nearly all the proposals in the People’s Party platform were later adopted by the major parties and passed into law.

Progressives & Nature

Unlike the People’s Party, the Progressive movement, which tried to merge Populist ideals of social justice with a celebration of scientific and social progress, was led to a much greater degree by urban intellectuals such as New Yorker Theodore Roosevelt and Princeton University president Woodrow Wilson. Progressives expressed their concern for the America outside the cities primarily through conservation and agrarian reform. America’s early conservation movement sprang from a growing appreciation of nature, especially among people whose lifestyles separated them from the natural world. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Prussian aristocrat and scientist Alexander von Humboldt traveled through Latin America collecting impressions and data that filled dozens of articles and books, making Humboldt one of the most famous men of his time. In 1804, Humboldt stopped in Washington on his return from the Andes and met with President Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had recently completed the Louisiana Purchase, and was curious about conditions in the Spanish colonies Humboldt had visited, in addition to sharing an interest in natural science. When Jefferson sent Louis and Clark to explore the northwest, he specifically directed them to collect scientific data about the plants and animals they encountered. This was partly because Jefferson believed detailed knowledge of the region would help support American claims on the territory, but also because he was genuinely interested in what they would discover.

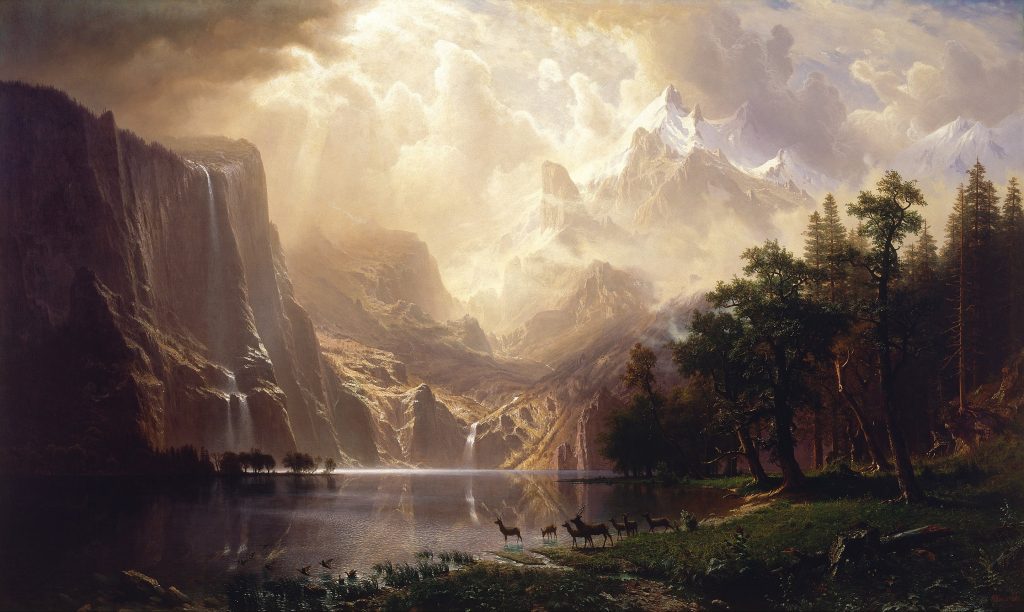

Interest in nature spread to the arts when British-born painter Thomas Cole became well-known in the 1830s for a style of romantic landscape painting that became known as the Hudson River School. Cole and his students painted not only scenes from the local countryside, but also natural monuments such as Niagara Falls. The falls were an inspirational destination for European travelers in America, and as transportation improved, for growing numbers of Americans. Thomas Cole and several of his students painted the falls, and many then traveled west to find new heroic vistas to paint. In the early 1860s, German-American painter Albert Bierstadt journeyed west with a survey expedition to paint in the Rocky Mountains and in the Sierras. His paintings, and those of other artists such as California natives Thomas Hill and William Keith, were reproduced as illustrations in popular magazines and travel guides. For many easterners, the western frontier became a land of unspoiled beauty imagined from these romantic depictions.

Yosemite Valley, in the California Sierras, was first painted in 1855 by a San Francisco artist named Thomas Ayres, who had moved to California in 1849 during the Gold Rush. In 1856 San Francisco’s newspaper, The Daily Alta California, carried Ayres account of “A Trip to the Yohamite Valley.” The article generated a lot of interest in the scenic region, and Ayres returned to Yosemite and produced sketches which he showed at the American Art Union in New York. On his return trip to California, around the Straits of Magellan in South America, Ayres’s ship sank and he and all his sketches were lost. But American leaders including Abraham Lincoln were influenced by Ayres and other artists’ representations of the west. In 1864, Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant, giving the region to the State of California as a park for “public use, resort and recreation.” Frederick Law Olmsted, the architect who had designed Central Park in New York, was appointed chairman of the park’s board of commissioners. During the Civil War, Montana Territory governor, Thomas Francis Meagher and railroad financier Jay Cooke suggested the “Great Geyser Basin” should also be protected. In 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the act that created Yellowstone, America’s fist national park. In 1891, at the urging of preservationist John Muir, Yosemite joined Yellowstone as a national park. In 1903, Theodore Roosevelt camped with Muir at Yosemite’s Glacier Point.

Today we think of Yellowstone and Yosemite as grand refuges, where pristine wilderness has been protected for future generations of Americans. But like many other American frontiers discovered since Europeans arrived in the New World, the national parks were already occupied when white men first encountered them. John Muir’s Sierra Club pressured the U.S. government until army troops removed the Indians whom Muir believed had “no place in the landscape.” Muir’s vision of the park as a “mountain mansion where nature has gathered her choicest treasures” did not include “such debased fellow beings.” In Yellowstone, park managers used the U.S. Army to evict resident Indians, declaring “we know that our right to the soils, as a race capable of its superior improvement, is above theirs.”

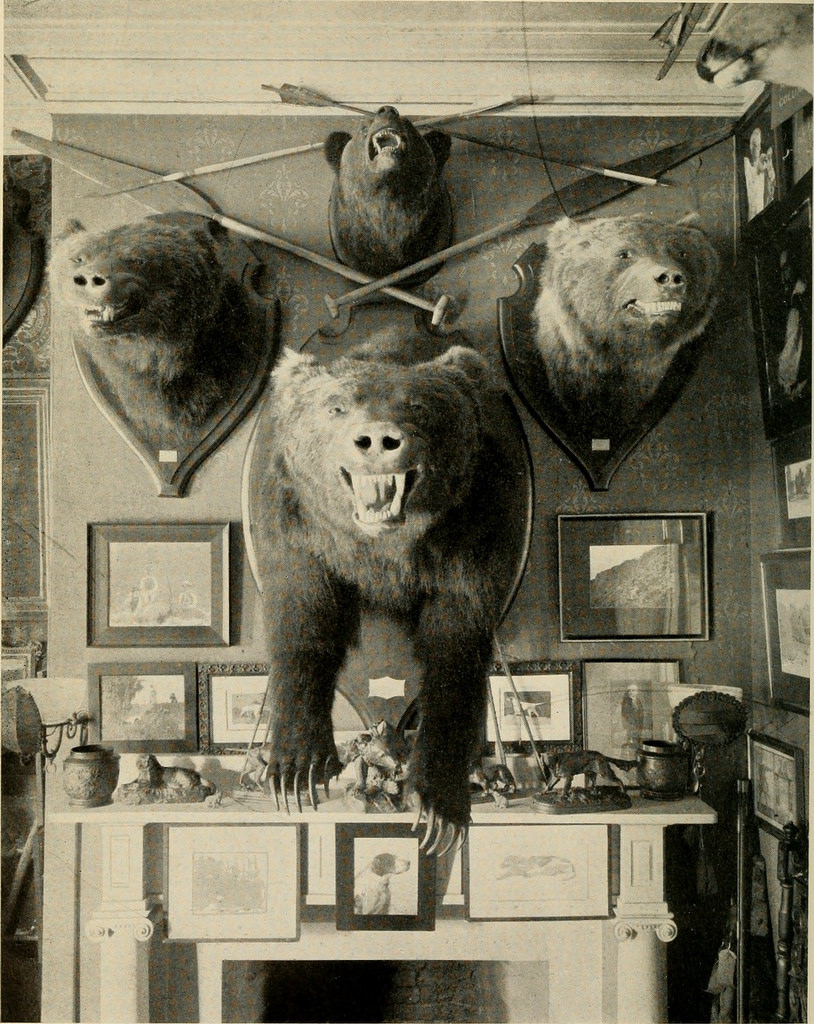

In addition to removing Indians from national parks, Progressives waged a war on poor rural people much closer to home, in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. In 1887, Progressive New York City Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt and several of his close associates formed a hunter-conservationist group called the Boone and Crockett Club, which dedicated itself to the preservation of big game. Members preached the sport-hunting ideal of “fair chase,” and opposed hunting for food or for the sale of food, which they called market hunting. In 1900, the Club helped pass the Lacey Act, which outlawed market hunting and prohibited the sale of wildlife, fish, and plants that had been illegally taken. Rural people who had hunted, fished, or gathered wild plants to feed their families and had occasionally sold surplus game were designated as poachers and prosecuted. While the regulations may have helped prevent game populations from being over-hunted, the laws also declared the subsistence practices of rural people illegal. People far from cities who took animals to feed their families suddenly found themselves fined or jailed as poachers, while rich members of the Club visited the woods to hunt big game and brought trophies home from African safaris.

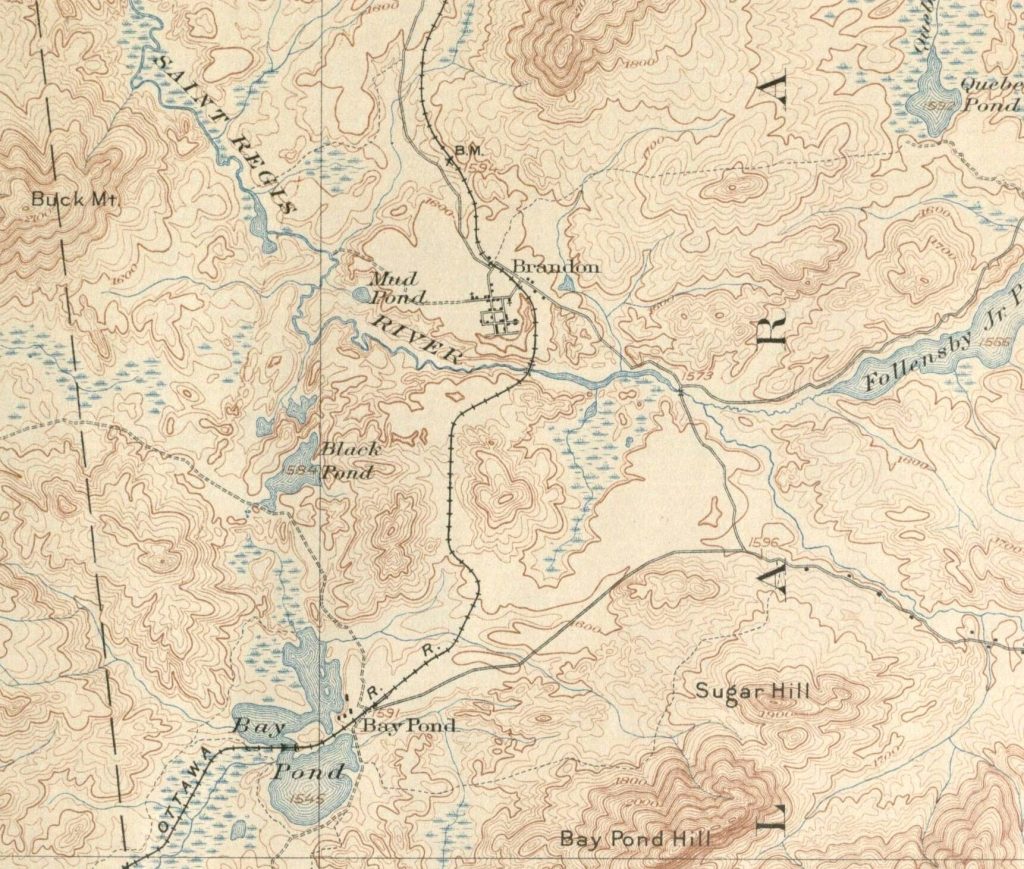

The Adirondacks are a 166-mile wide dome of mountains, about two hundred miles north of New York City. The Hudson river begins in the Adirondacks, and although the high terrain made poor farmland, it was ideally situated for wealthy New York sportsmen seeking weekend wilderness adventures. By 1893, sixty private game parks had been established, containing more than 940,000 acres of the region’s best hunting and fishing grounds. Another 730,000 acres was controlled by the State-owned Forest Preserve. In 1894, Forest and Stream Magazine observed that “private parks in the Adirondacks today occupy a considerably larger area than the State of Rhode Island.” Wealthy Manhattanites continued buying upstate parcels for estates they called “camps” in spite of the mansions filled with servants they established there. By 1899, the New York State Legislature was considering bills that would completely exclude poor people who had lived in the region for generations from hunting in the Adirondacks. Residents had little influence in Albany, but they knew their way around local forests. In 1903, after prosecuting several trespassers and poachers on his estate, 49-year old millionaire lawyer Orrando Perry Dexter was murdered by northern vigilantes.

One of the most visible and symbolic battles between wealthy “camp” owners and northern residents was played out in the courts beginning in 1902. Oliver Lamora, a Civil War veteran living in the Adirondack town of Brandon, supplemented his military pension with fishing and hunting in the woods surrounding the town. Originally a lumber town, Brandon’s fortunes had declined after the best marketable timber was cut. Around 1900, the town’s sawmill and surrounding timberland was sold to William Rockefeller, who had co-founded Standard Oil and along with his brother John was one of the world’s richest men.

Rockefeller bought out Brandon residents who chose to leave, and tore down their houses. Within a couple of years, he had removed several hundred buildings and New York magazines had begun humorously referring to Rockefeller as a “Maker of Wilderness.” But fourteen Brandon families decided not to sell. Oliver Lamora was among the holdouts. The problem was, there was virtually no way to leave the town of Brandon without crossing Rockefeller’s land. And anyone who trespassed was liable to be arrested and prosecuted. In April 1902, Lamora set out along one of the paths that crossed William Rockefeller’s camp. Worse, he stopped to fish in the St. Regis River, which Rockefeller considered his personal property. After catching over a dozen fish, Lamora was himself caught by one of the estate’s guards, and was prosecuted under New York’s Fisheries, Game, and Forest Law.

Lamora demanded a jury of his peers, and his peers acquitted him. Rockefeller was embarrassed and charged $11.39 in court costs for bringing a frivolous lawsuit. Rockefeller appealed and lost. But the co-founder of Standard Oil was one of the world’s richest men, and he was not accustomed to defeat. The New York Times remarked that “the case was carried from one court to another until a decision was rendered in favor of Mr. Rockefeller.” But sympathy for Lamora was strong and the jury awarded damages of only 18 cents. In the meantime, Adirondack locals had taken up subscriptions to cover Lamora’s court expenses and began going out of their way to fish in Rockefeller’s park. In 1903, the Times reported that “Mr. Rockefeller’s men have taken the names of upward of fifty persons who were found fishing in the Rockefeller park.”

Although newspapers and magazines like Forest and Stream were critical of the camps, pointing out that “Rockefeller, J. Pierpont Morgan…and other landed proprietors in the Adirondacks are only doing with our woods what they have already done with our industries,” wealthy New Yorkers were not prevented from buying up Adirondack land. In 1900, the park’s area was roughly 2.8 million acres. About 1.2 million acres was state-owned, the rest private. By 2000, the park had grown to 6 million acres. About 2.4 million acres are state-owned, and another 600,000 acres taken up by towns, lakes, and small holdings. That leaves 3 million acres in private hands. Rather than shrinking during what has been typically considered a very liberal century, private holdings have nearly doubled, until they now take up an area roughly equal to the State of Connecticut. As an illustration that the trend continues, in 2015, Alibaba.com founder Jack Ma purchased a 28,000 acre estate including the Rockefeller camp, the former town of Brandon, seven miles of river, eleven trout ponds, and a 2,200-foot mountain, for $27 million.

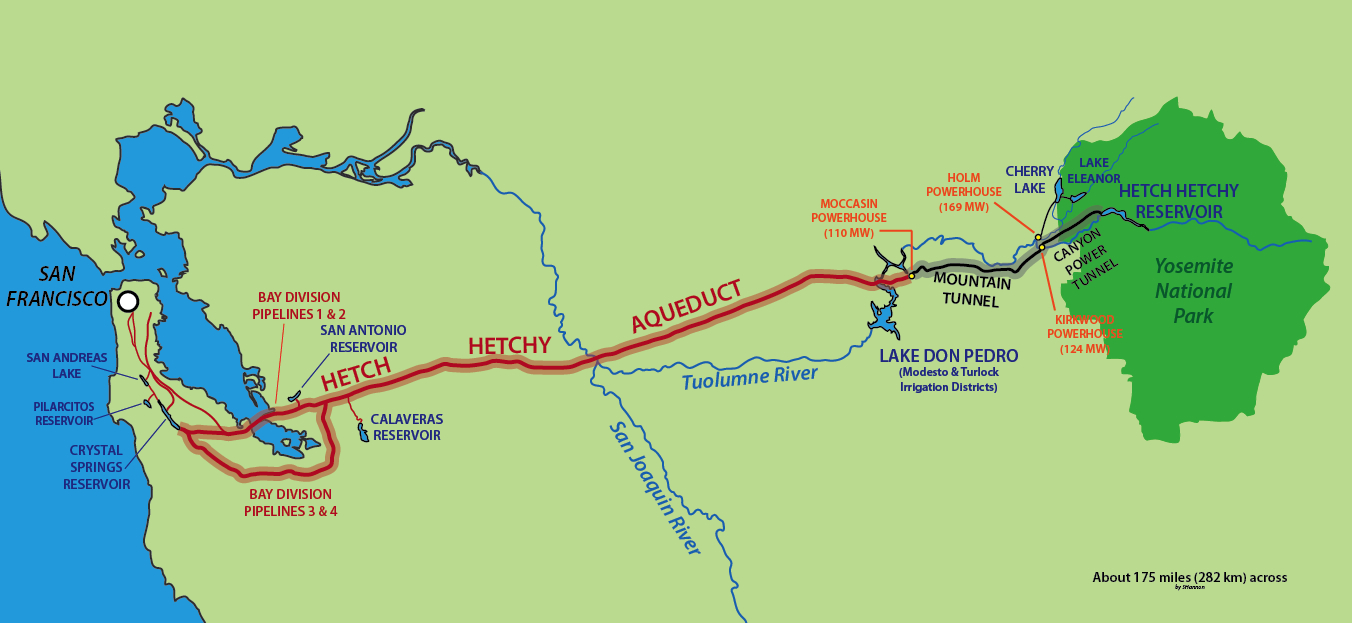

In the western states, conflicts over wilderness did not end when the Indians were evicted from the new national parks. One of the most divisive issues ever faced by Progressives focused on a battle between conservationists and preservationists when a portion of Yosemite was proposed as a source of water for the city of San Francisco. Like Boston and New York, San Francisco had grown around its harbor and the city was surrounded by seawater that its residents could not drink. As population climbed in the early years of the California Gold Rush, drinking water was actually ferried across the bay from Sausalito and sold by water vendors. Carts loaded with barrels and horse-drawn tankers plied the city’s steep streets daily, delivering water to homes and businesses. San Francisco had dammed small, nearby rivers to build the Pilarcitos and San Andrés Reservoirs in the 1860s and 1870s, but the city’s need for water kept increasing. And water sources close to San Francisco were all controlled by private companies, which worried city planners. The city of San Francisco wanted to control its own water supply, so plans were made in the late 1880s to look for a source farther away. By 1901 city water planners had decided the best source was the Hetch Hetchy Valley of the Tuolumne River.

The Tuolumne River was fed by a glacier in the Sierra Mountains and flowed through a scenic valley 150 miles from San Francisco. To keep their interest in the Hetch Hetchy secret, San Francisco officials filed for water rights in the valley as private citizens. They claimed this was to prevent speculators from buying up the water supply, which had actually happened in 1875 when San Francisco had expressed interest in the Calaveras Valley watershed. It may also have been an attempt to keep the project secret as long as possible from wilderness preservationists like John Muir, a nationally-known activist who had lobbied the U.S. Congress for legislation that had created Yosemite National Park, in which the valley was located, in 1890, and had founded the Sierra Club in 1892.

San Francisco’s interest in damming the Tuolomne River reached a new intensity after the Earthquake and Fire of 1906, which destroyed over eighty percent of the city. Although most of the city’s water mains had been broken by the quake, many blamed inadequate water supplies for the extensive damage inflicted by three days of fire. Opponents of San Francisco’s plan to dam the Tuolomne believed the valley was too valuable as wilderness to be sacrificed for a city water supply. Critics were also suspicious of the San Francisco officials who insisted that a Hetch Hetchy dam was the only viable plan. In 1907, San Francisco’s mayor and his political sponsor were both convicted of graft and corruption for supporting a scheme to have the city buy the Bay Cities Water Company, a private corporation that controlled water sources closer to town. The mayor was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison, which he did not serve. The mayor’s wealthy patron was actually sent to San Quentin.

Since the Hetch Hetchy Valley was inside America’s second national park, it required an Act of Congress to approve the dam project. After years of intense lobbying by both sides, dam supporters won the support of Washington lawmakers, and the project was begun in 1913. The Hetch Hetchy controversy forced conservationists and preservationists to articulate and debate their competing visions of how Americans should interact with nature, and especially of how the government should deal with the environment. The arguments supporting the dam were presented by Roosevelt’s Chief of the U.S. Forest Bureau, Gifford Pinchot, and the arguments against the project by John Muir. Although the decision was ultimately made to flood the valley, the issues raised by the debate regarding the value and purpose of wilderness have yet to be fully resolved.

In addition to difficulty agreeing who wilderness should be for, modern America has struggled with the basic concept of wilderness. In the inaugural issue of the journal Environmental History in 1996, historian William Cronon contributed an essay titled “The Trouble with Wilderness or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Cronon observed that for many modern Americans, “wilderness stands as the last remaining place where civilization, that all too human disease, has not fully infected the earth.” The more we learn of its particular history, Cronon said, the more we realize that “wilderness is not quite what it seems. Far from being the one place on earth that stands apart from humanity, it is quite profoundly a human creation.” When we look at “Nature”, Cronon said, “in fact we see the reflection of our own unexamined longings and desires.” Cronon recounted the stories of Indians excluded from national parks to make them appear pristine, and of the Hetch Hetchy Valley. He discussed Euro-American cultural traditions and concluded that although we fail to understand that what we believe are wild areas are usually constructed, the connection we seek is a sense of wonder. Wilderness, he said, “gets us into trouble only if we imagine that this experience of wonder and otherness is limited to remote corners of the planet, or that it somehow depends on pristine landscapes we ourselves do not inhabit.” Even though a tree in a pristine forest might represent a more complicated web of ecological relationships, Cronon concluded, “the tree in the garden is in reality no less other, no less worthy of our wonder and respect.” Nature remains important, Cronon said, even if it has people in it.

The idea of nature with people in it returns us to Country Life, the other concern of liberal intellectuals and Progressive reformers at the beginning of the twentieth century. Progressive solutions to what they perceived as a “rural problem” in the early twentieth century were often quite different from those advocated by rural people themselves. Progressives were frequently urban elites, who although genuinely concerned about country life, were not really living it. The issues they perceived were not always the same as the problems country people experienced. But sometimes, like rural Populists such as Albert Todd who had visited Europe and drawn on the experiences of a wider culture, American Progressives were joined by foreigners with wider perspectives, who were able to see causes and connections that were not apparent to rural people or to the urban Progressives who sought to help them.

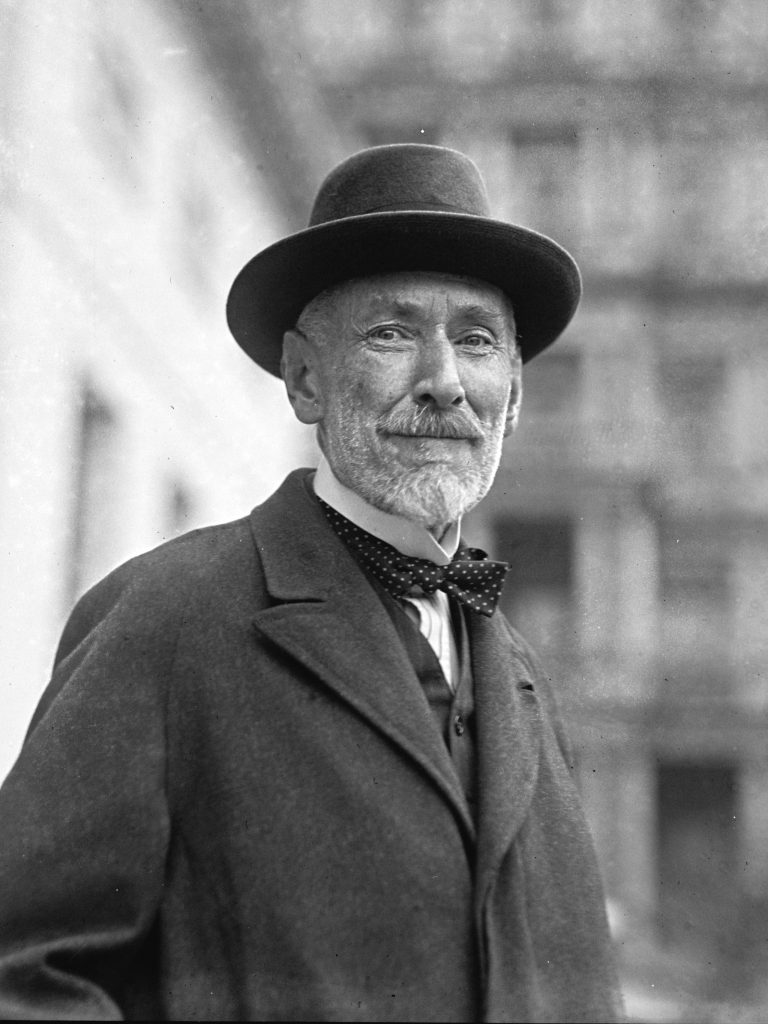

One such foreigner who contributed to the examination of country life was an Anglo-Irish aristocrat born at Dunsany Castle in Ireland. Sir Horace Plunkett was the third son of the sixteenth Baron Dunsany and the uncle of the famous fantasy author known as Lord Dunsany. Horace Plunkett was a leading activist for Irish home rule, and he developed the idea of Irish rural cooperatives. Plunkett believed that “The city has developed to the neglect of the country.” He suggested that of Theodore Roosevelt’s “Three Pillars of Country Life,” which were “better farming, better business, and better living,” the business problems of farmers should be addressed first. Being a wealthy aristocrat, Plunkett had access to American leaders like President Roosevelt, conservationist Gifford Pinchot, and railroad tycoon James Jerome Hill, all of whom had expressed interest in country life issues. Plunkett wrote a series of magazine articles beginning in 1908 that he compiled into a best-selling book called The Rural Life Problem of the United States.

During the first phase of the industrial revolution, Plunkett said, “economic science stepped in and, scrupulously obeying its own law of supply and demand, told the then-predominant middle classes just what they wished to be told.” Social and political science, he said, “rose up in protest against both the economists and the manufacturers, but they were pushed aside in the rush for progress.” Aside from this strangely antique language, many of Plunkett’s ideas apply equally well to problems we face today. Unusual for an analysis written a hundred years ago, Plunkett introduced the idea of a world market. And he said that neglect of rural regions was caused in part by the fact that reciprocity between the city and country had not really ceased. Interactions had actually increased, Plunkett said, but had become national and even international rather than local. Plunkett noted that “42 percent of materials used in manufacture in the United States are from the farm, which also contributes 70 percent of the country’s exports.” But the complexity of new trade patterns and supply chains had hidden the mutual dependence of city and country. Plunkett concluded, “Until the obligations of common citizenship are realized by the town, we cannot hope for any lasting national progress.”

If there was specific blame to be laid, Plunkett directed it not at the system, but at what he called “profiteers.” He wrote in 1908, “Excessive middle profits between producer and consumer may largely account for the very serious rise in the price of staple articles of food.” But even though urban middlemen were to blame and the problem impoverished rural people at the same time it aggravated the plight of poor city people, Plunkett said, “the remedy lies with the farmer” rather than with legislative action or government reform. Like the country life advocates who followed him, in the Progressive era and the New Deal of the 1930s, Plunkett connected the rural problem to the breakdown of democracy. Plunkett said that excluding people from the political sphere had damaged the democratic process. Farmers’ experience of the cycles of nature, which Plunkett described as slower and less affected by fads and market forces than the commercial and industrial processes that city people lived within, gave country people a more balanced political sense. City-dwellers’ one-sided experience may account for what Plunkett called “that disregard of inconvenient facts and that impatience of the limits of practicability which many observers note as a characteristic defect of popular government.” Plunkett also suspected farmers might be less attracted to socialism, which was a big concern in the early twentieth century, because in the country, he said, “the divorce of the worker from his raw material by the force of capitalism does not arise.” Unlike urban factory workers, Plunkett believed American farmers were not alienated from their means of production, because most of them were the proprietors of their own small businesses. Farmers were not victims of capitalism in the same way that urban wage-workers were. This entrepreneurial element of farming has definitely been eroded in the twentieth century, as agribusiness expanded and power shifted to the food processors who were the farmers’ customers, and often also their suppliers and their mortgage-holders. But it could be restored if more farmers could build connections with consumers through farmers’ markets, direct marketing, or community supported agriculture (CSAs).

Plunkett called for what he called “a moral corrective to a too-rapidly growing material prosperity.” But he did not really identify the motivation for what he called “the reckless sacrifice of agricultural interests by the legislators of the towns.” The issue he avoided confronting directly was the increasing unevenness of prosperity. Even in rural areas, the rewards went disproportionately to the few, and in most cases profits were captured by middlemen at the expense of both rural producers and urban consumers. “Under modern economic conditions, things must be done in a large way if they are to be done profitably,” Plunkett said, “and this necessitates a resort to combination.” Corporate organizations had three benefits, he said: economies of scale, elimination of what he called “the great middlemen who control exchange and distribution,” and political power. For better or worse, Plunkett said, “towns have flourished at the expense of the country by use of these methods, and the countryman must adopt them if he is to get his own again.” But farmers, Plunket admitted, “being the most conservative and individualistic beings,” were unlikely to organize themselves in joint stock companies or corporations, and hand over control to others.

Plunkett’s solution, the farmer’s cooperative, was a social and political as well as an economic tool because, “when farmers combine, it is a combination not only of money but of personal effort in relation to the entire business.” Plunkett tried to emphasize that the distinction between the capitalistic basis of joint stock ownership and the more human character of the cooperative system is fundamentally important. Compared to Ireland, where Plunkett had been instrumental in developing rural cooperatives, “the American farming interest is at a fatal disadvantage in the purchase of agricultural requirements, in the sale of agricultural produce, and in obtaining proper credit facilities.” Cooperatives could address each of these needs. “The long-term result of better business,” Plunkett said, would be Theodore Roosevelt’s other two priorities, better farming and better living. Cooperatives would begin a process of renewing rural social bonds, leading to a new neighborhood culture. Rather than trying to bring the advantages of the city to the country, Plunkett hoped rural communities would “develop in the country the things of the country, the very existence of which seems to have been forgotten.” After all, he said, “it is the world within us rather than the world without us that matters in the making of society,” once the physical necessities like clean water, medicine, and electricity had been made available by attending to better business.

Plunkett was well aware that his subject was rural but his audience was urban, and this may explain why his final chapter focused on education and socialization. Many urban Progressives felt that in addition to the economic and social challenges rural people faced, that there was something wrong with country people themselves. Unlike Plunkett, many American reformers believed rural people were inferior, either genetically or socially. Rural problems became a popular subject of study in the 1900s and 1910s, and groups like the American Sociological Society organized conferences and published books and articles on subjects such as “The Mind of the Farmer”, “Folk Depletion as a Cause of Rural Decline”, and “Social Control Through Rural Religion.” Universities published the results of studies announcing that the problem with country people was that nearly all of them had intestinal parasites. Other academics claimed the problem was the decline of rural schools or rural churches. Roosevelt’s Commission on Country Life was genuinely concerned about the problems of rural America, where half the nation’s population still lived. But the reformers were often perceived as condescending elitists who were out of touch with actual rural life. A century after the Country Life Commission issued its report, the rural webzine Daily Yonder commemorated it with an article titled “Country Life Movement—Miles To Go.”

The Country Life movement of the early twentieth century did produce some tangible results. The American Farm Bureau Federation, the Cooperative Extension Service of the land-grant colleges, the Bureau of Public Roads that paved many of the old mud tracks that people in the countryside struggled with, and the Farm Credit Bureau were all established in response to concerns identified by the movement. A couple of decades later, in the New Deal, rural electrification and the Farm Credit Administration addressed what were perceived as continuing problems of rural America, while at the same time providing employment and financial opportunities for unemployed workers, idled businesses, and underutilized credit markets. It is interesting that in addition to obvious issues like social change and natural resource use, people concerned with country life a century ago were well aware of globalization, of middlemen, and sometimes even of the differing world-views of rural and urban people. It will be interesting to see whether the twenty-first century makes better progress on these issues than the twentieth century was able to achieve.

https://youtu.be/yIKeAA9j6j0

Further Reading

Timothy Collins, “Country Life Movement—Miles to Go,” Daily Yonder June 24 2009. http://www.dailyyonder.com/country-life-movement-miles-go/2009/06/24/2189/

William Cronon, “The Trouble with Wilderness or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” Environmental History 1:1, Jan. 1996. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3985059

Karl Jacoby, Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation. Reprint 2014.

Horace Curzon Plunkett, The Rural Life Problem of the United States: Notes of an Irish Observer. 1910, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.34258

Media Attributions

- 00025v © American Oleograph Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gift_for_the_grangers_ppmsca02956u (1) © Strohbridge & Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1904CampaniaDetail © A.M. Todd Company, photo by Dan Allosso is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Humboldt und Bonpland am Fuß des Chimborazo in Ecuador © Friedrich Georg Weitsch is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cole_Thomas_The_Oxbow_(The_Connecticut_River_near_Northampton_1836) © Thomas Cole is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-Albert_Bierstadt_-_Among_the_Sierra_Nevada,_California_-_Google_Art_Project © Albert Bierstadt is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Muir_and_Roosevelt_restored © Underwood & Underwood is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 14779237211_516f4d8f50_b © G.B. Grinnell is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1905-Saint-Regis-1905-rp1908 © USGS is licensed under a Public Domain license

- William_Rockefeller_Home © Postcard is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hetch_Hetchy_Valley © Isaiah West Taber is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hetchhetchyprojmap © Shannon1 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Hetch_Hetchy_Valley_in_Yosemite_NP-1200px © Mav is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 2880px-The_Hetch_Hetchy_Valley,_California,_by_Albert_Bierstadt,_undated_-_Museum_of_Fine_Arts,_Springfield,_MA_-_DSC03988 © Albert Bierstadt is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sir_Horace_Plunkett,_1-15-23_LOC_npcc.07656_(cropped) © National Photo Company is licensed under a Public Domain license

- AG3 © USDA is licensed under a Public Domain license