6 Transportation Revolution

The transportation revolution in the United States began when Americans taking advantage of features of the natural environment to move people and things from place to place began searching for ways to make transport cheaper, faster, and more efficient. Over time a series of technological changes allowed transportation to advance to the point where machines have effectively conquered distance. People can almost effortlessly travel to anywhere in the world and can inexpensively ship raw materials and products across a global market.

But this technology is not ubiquitous, and it is not necessarily democratic. As a famous science fiction writer once said, the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed. Modern transportation infrastructure is controlled to a great extent by large corporations, but the benefits of transport are depended on by everyone. And transportation technology itself requires specific conditions such as abundant, cheap, portable energy in the form of fossil fuels, and public infrastructure created by our own and foreign governments, that even those large corporations depend upon but don’t control.

When we think of transportation, it is natural to think first about going places. Getting on a plane in one hemisphere and getting off on the other side of the world is a life-changing opportunity which was unavailable to most people as little as a generation ago, and unthinkable two generations ago. But more crucial to our daily lives than the freedom offered by world travel is the cargo from the other side of the world that reaches us quickly in the holds of jets and more slowly but in almost unimaginable volume in containers on ships. The global transportation of foods, raw materials, and finished goods goes virtually unnoticed in our daily lives, but makes our contemporary consumer lifestyle possible.

Although even the early stages of the transportation revolution allowed people like seventy-year old Achsah Ranney, from Chapter Five’s Supplement, to travel regularly between her children’s homes in Massachusetts, New York, and Michigan, the more significant change was the ability of her sons and of other Americans to move freight from place to place. The ability to effectively ship food and other goods to where they were needed allowed people to stay put, and even to concentrate themselves in cities in a way they had never been able to do before. The growth of eastern cities depended just as much on the transportation revolution as did the building of new cities in the west.

As we have already seen, early Americans made amazing journeys with very primitive methods of transportation. The people who crossed Beringia and settled North and South America were able to cover startlingly long distances on foot. European explorers crossed dangerous oceans to visit the Americas in tiny ships. Human and animal power has been used extensively throughout American history, and is still used today to reach remote areas off the grid. But it is clear that improvements in transportation technology have been among the most powerful drivers of change in our history. And the transportation revolution has certainly changed our relationship with the American environment.

Technological improvements to ocean-going ships in the fifteenth century made European colonialism possible in the first place. Ships became bigger, faster, and safer. More people and goods could leave the safety of coastal waters and cross the oceans, and the places these improved ships connected became centers of trade, population, and wealth. This pattern of growth repeated itself as new technologies were developed to help Americans expand across the continent.

As we have seen, American colonists depended on trade with England and with the sugar planters of the West Indies to make their outposts in New England and Virginia successful. But from the beginning of the American Revolution to the conclusion of the War of 1812, relations between the new nation and Britain were tense and trade suffered. If it had not found a way to ship people and goods to and from its own frontier, the United States would have remained a coastal nation focused on ports like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. The barely-remembered Whiskey Rebellion of 1791, when George Washington led United States troops against American farmers in western Pennsylvania, was really about transportation. Farmers west of the Appalachian mountains could not easily haul wagon-loads of grain to eastern markets, so they turned their harvests into a more portable product by distilling grain into whiskey. The farmers believed the government’s excise tax on distilled spirits had been instituted to drive them out of the whiskey business for the benefit of large Eastern distillers. Since they had few other sources of income, the tax was a serious issue for westerners. Luckily, the incoming Jefferson administration repealed the tax in 1801 and increasing Ohio River shipping provided new outlets for western produce.

Roads and Rivers

On the eve of the Revolution, the only road that did not hug the east coast followed the Hudson River Valley into western New York on its way to Montreal (this was one reason colonial Americans seemed continually obsessed with the idea of conquering Montreal and bringing it into the United States). Less than thirty years later, riders working for the Post Office Department carried mail to nearly all the new settlements of the interior. The postal system’s designer, Benjamin Franklin, understood that in order for the new Republic to function, information had to flow freely. Franklin set a low rate for mailing newspapers, insuring that news would circulate widely in the newly-settled areas. But it was one thing carrying saddlebags filled with letters and newspapers to the frontier, and something else moving people and freight.

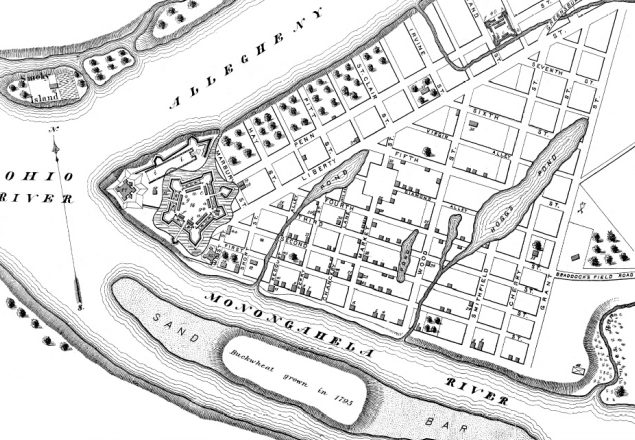

Rivers were the first important routes to the interior of North America. The Ohio River, which begins at Pittsburgh and flows southwest to join the Mississippi, helped people get to their new farms in the Ohio Valley and then helped them carry their farm produce to markets. The Ohio River Valley became one of the first areas of rapid settlement after the Revolution, along with the Mohawk River Valley in western New York. The importance of river shipping is illustrated by the fact that over fifty thousand miles of tributary rivers and streams in the Mississippi watershed were used to float goods to the port of New Orleans. The dependence of western farmers on the Spanish port also explains why New Orleans was a considered strategic city by the United States in the War of 1812. Thomas Jefferson’s 1803 purchase of the Louisiana Territory had actually begun as an attempt to buy the city of New Orleans, and Andrew Jackson’s defense of the port during the War of 1812 was vital to insuring the success of western expansion.

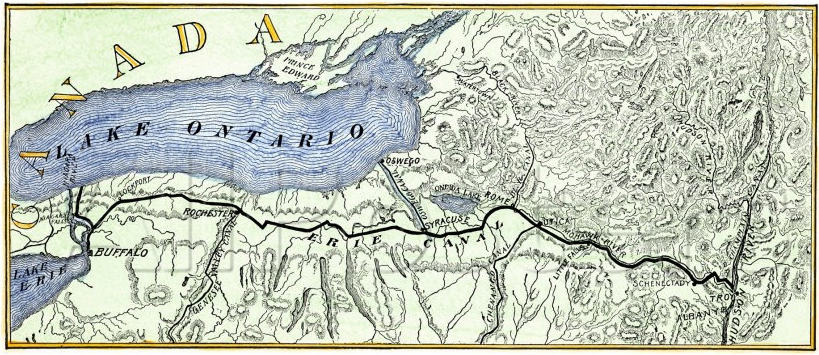

Early westward expansion depended on rivers, and towns and cities built during this era were usually on a waterway. Pittsburgh, Columbus, Cincinnati, Louisville, St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha, and St. Paul all owe their locations to the river systems they provide access to. Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and Milwaukee utilize the Great Lakes in the same way. These lakeside cities exploded after the Erie Canal opened a route from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic, and allowed New York to overtake New Orleans as the nation’s most important commercial port. The 363-mile Erie Canal was so successful that another four thousand miles of canals were dug in America before the Civil War.

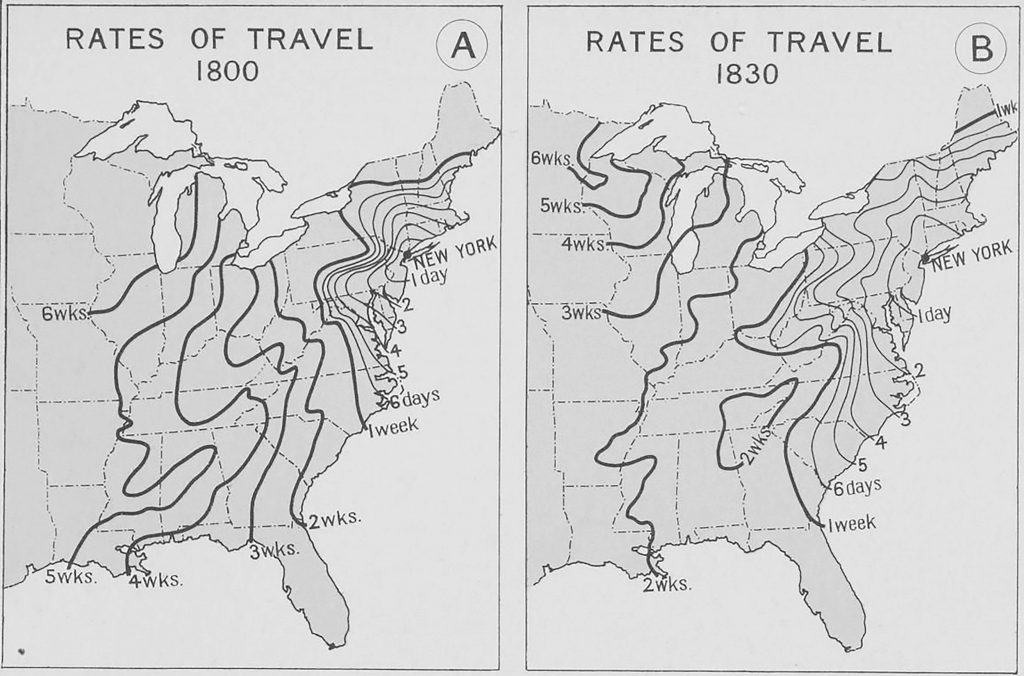

In 1800, it took nearly two weeks to reach Buffalo from New York City, a month to get to Detroit, and six grueling weeks of travel to arrive at the swampy lake-shore settlement that would become Chicago. Thirty years later, Buffalo was just five days away, Detroit about ten days, and Chicago less than three weeks. Horses pulled canal boats from towpaths on shore, eliminating the strain of travel for the boats’ passengers. Floating along on calm water was infinitely more comfortable than spending weeks on a wagon, in a cramped stage coach, or on horseback. The number of people willing to make long trips increased accordingly. And the amount of freight shipped to New York, after the canal cut shipping costs by over ninety percent, increased astronomically. Goods flowed along the Canal in both directions, offering life-changing opportunities. As mentioned previously, within ten years of the Erie Canal’s completion, the last fulling mill processing homespun cloth in Western New York shut its doors. Women no longer had to spend their time spinning wool and weaving their own textiles to make their family’s clothing. They could buy bolts of wool and cotton fabrics from the same merchant at the local general store who ground their family’s grain into flour and shipped it on the Canal to eastern cities. With fewer demands on their time, many women were able to not only improve their own quality of life, but contribute to family income by taking in piece-work, raising cash crops, or keeping cows and churning butter for sale to their local merchants.

The Age of Steam

Steam technology changed the nature of transportation. Until steam engines were put on riverboats, shipping had depended on either wind and river currents or on human and animal power. Goods could easily be floated south from farms on the nation’s rivers, but it was much more difficult and expensive to ship products against the rivers’ currents to the frontier. Flatboats and rafts accumulated at downstream ports, and were often broken down and burned as firewood. Steam engines made it possible to sail upstream as easily and nearly as quickly as down, causing an explosion of travel and shipping that radically changed frontier life.

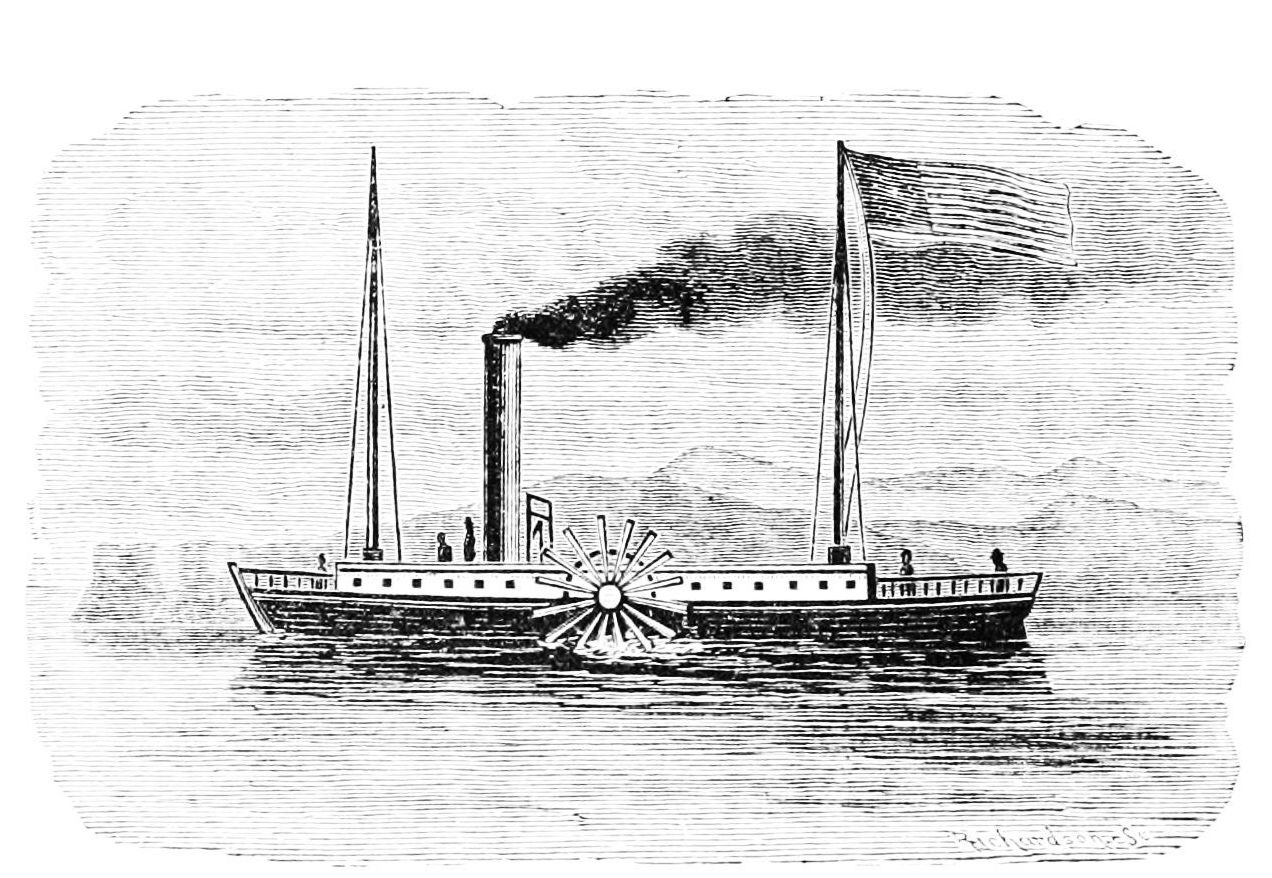

Steam engines were a product of early European industrialism. The first steam patent was granted to a Spanish inventor named Jerónimo Beaumont in 1606, whose engine drove a pump used to drain mines. Englishman James Watt’s 1781 engine was the first to produce rotary power that could be adapted to drive mills, wheels, and propellers. Robert Fulton, an American inventor who had previously patented a canal-dredging machine, visited Paris and caught steamboat fever. Fulton sailed an experimental model on the Seine, and then returned home and launched the first commercial American steamboat on the Hudson River in 1807. The Clermont was able to sail upriver 150 miles from New York City to Albany in 32 hours. In 1811, Fulton built the New Orleans in Pittsburgh and began steamboat service on the Mississippi.

Although Robert Fulton died just a few years later of tuberculosis, his partners Nicholas Roosevelt and Robert Livingston carried on his business, and the age of riverboats was underway. Like Fulton’s prototype and the Clermont, the New Orleans was a large, heavy side-wheeler with a deep draft. It was not the most efficient design for shallow water, and it did not take long for ship-builders to settle on the familiar shallow-draft rear-paddle riverboats that carried freight on the Mississippi and its tributaries well into the 20th century. The shallower a riverboat’s draft, the farther upriver it could travel. Steam-powered riverboats soon pushed the transportation frontier to Fort Pierre in the Dakota territory and even to Fort Benton, Montana. Riverboats made it possible to ship goods in and out of nearly the whole area Thomas Jefferson had acquired in the Louisiana Purchase just a generation earlier. And steam-powered ocean shipping made the markets of Britain and Europe readily accessible to farmers and merchants in the middle of North America.

The other transportation technology enabled by steam power, of course, was the railroad. But railroads were even more revolutionary than steamboats. In spite of their power and speed, steam-powered riverboats depended on rivers or occasionally on canals to run, but a railroad could be built almost anywhere. Suddenly, the expansion of American commerce was no longer limited by the routes nature had provided into the frontier.

America’s first small railroads had actually been built on the East Coast before a steam engine was available to power them. Trains of cars were pulled by horses and looked a lot like stage-coaches on rails. But after Englishman George Stephenson’s locomotives began pulling passengers and freight in northwestern England in the mid-1820s, Americans quickly switched to steam. The first locomotive used to pull cars in the United States was the Tom Thumb, built in 1830 for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Although Tom Thumb lost its maiden race against a horse-drawn train, Baltimore and Ohio owners were convinced by the demonstration of steam technology and committed to developing steam locomotives. The railroad, which had been established in 1827 to compete with the Erie Canal, already advertised itself as a faster way to move people and freight from the interior to the coast. Adding steam engines accelerated rail’s advantage over canal and river shipping.

Over 9,000 miles of track had been laid by 1850, most of it connecting the northeast with western farmlands. The Mississippi River was still the preferred route to market from Louisville and St. Louis south. But Cincinnati and Columbus became connected by rail to the Great Lake ports at Sandusky and Cleveland, giving the northern Ohio Valley faster access to New York markets. Detroit and Lake Michigan were also connected by rail, making the long steamboat trip around the northern reach of Michigan’s lower peninsula unnecessary.

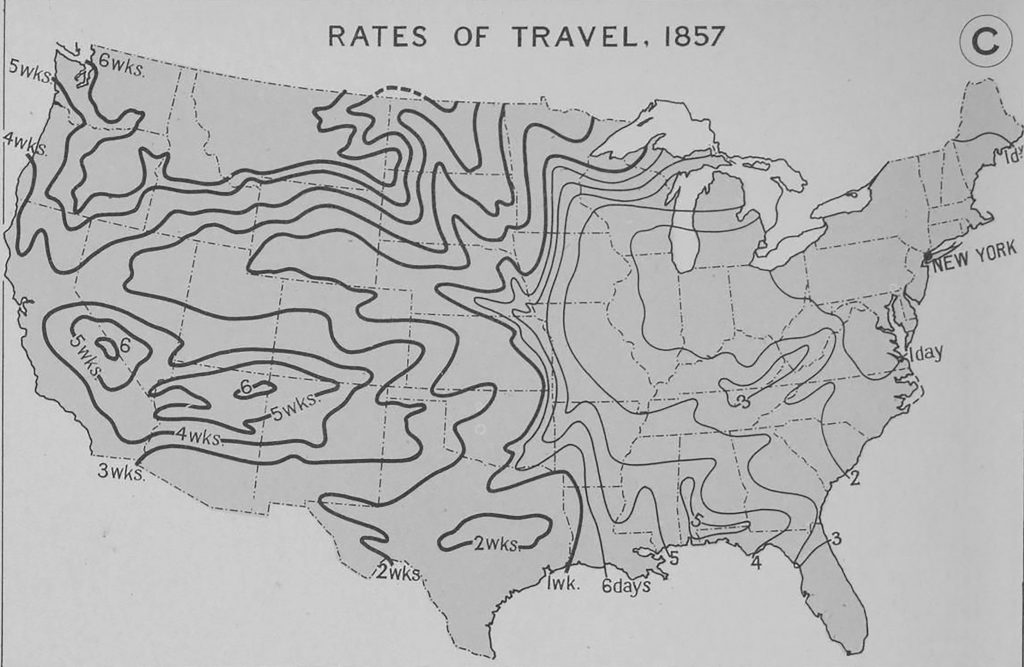

By 1857, rail travelers could reach Chicago in less than two days and could be almost anywhere in the northern Mississippi Valley in three. On the eve of the Civil War in 1860, Chicago was already becoming the railroad hub of the Midwest. The Illinois Central Company had been chartered in 1851 to build a rail line from the lead mines at Galena to Cairo, where the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers joined. Galena is also located on the Mississippi on the northern border of Illinois, but rapids north of St. Louis made transporting ore on the river impossible, illustrating the advantage of rails over rivers. A railroad line to Cairo, with a branch line to Chicago, would also attract settlers and investors to Illinois. Young Illinois attorney Abraham Lincoln helped the Illinois Central lobby legislators and receive the first federal land grant ever given to a railroad company. The company was given 2.6 million acres of land, and Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas helped design the checkerboard distribution of parcels that would become common for railroad land grants. The map below shows the extent of the land the government gave to the Illinois Central Company, which a few years later showed its gratitude by helping to finance Lincoln’s Presidential campaign against Douglas.

The North’s advantage over the Confederate South in railroad miles and the Union Army’s ability to move troops and supplies efficiently had a definite impact on the outcome of the Civil War. In the years following the war, the shattered South added very little railroad track and repaired only a small percentage of the tracks the Union Army had destroyed during the war. While railroads languished in the South, rail miles in the North exploded. In 1869, the West Coast was connected through Chicago to the Northeast, when the Union and Central Pacific Lines met at Promontory Point Utah on May 10th. The building of a transcontinental railroad was made possible by the Pacific Railroad Act, which President Lincoln had signed into law in 1862.

Public or Private?

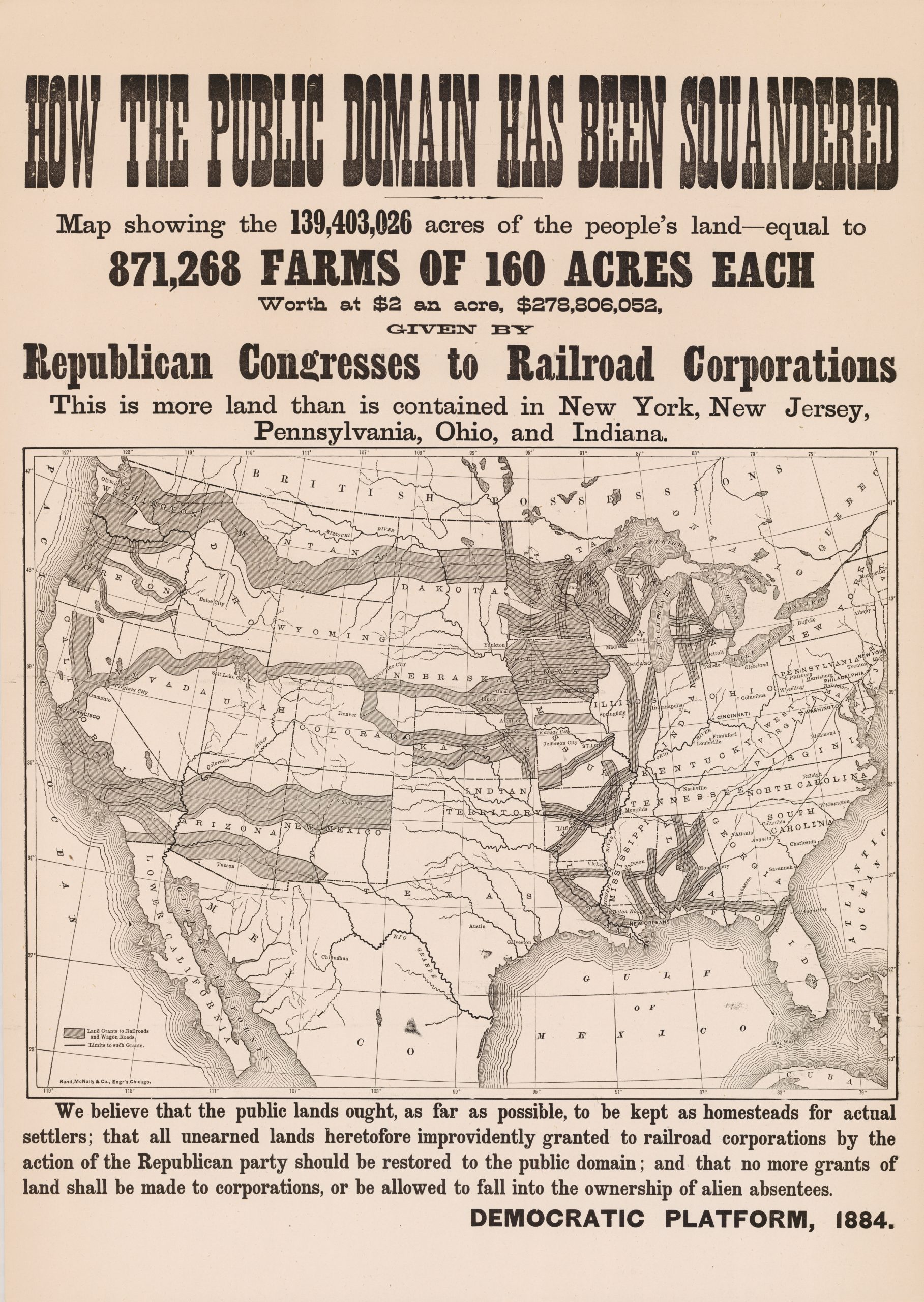

The Pacific Railroad Act was the first law allowing the federal government to give land directly to corporations. Previously the government had granted land to the states for the benefit of corporations. The Act granted ten square miles of land to the railroad companies for every mile of track they built. Land next to railroads always increased in value. The unprecedented gift of ten square miles of rapidly-appreciating land for every mile of track was a tremendous incentive to railroad companies to lay just as much track as they possibly could. Decisions to build lines were frequently based on the land granted, rather than on whether or not railroad companies expected the new lines to carry enough traffic or generate enough freight revenue to pay for themselves. In the eighteen years between the original Illinois Central grant of 1851 and the completion of the transcontinental line in 1869, privately-owned railroads received about 175 million acres of public land at no cost. This amounts to about seven percent of the land area of the contiguous 48 states, or an area slightly larger than Texas. For comparison, the Homestead Act distributed 246 million acres to American farmers over a 72-year period between 1862 and 1934, but required homesteaders to live on and to farm the land continuously for five years or pay for their parcel. The justification for the residency requirement was that the government was concerned homesteaders would become speculators and flip their farms. Railroad land grants were made with no similar stipulations because railroad corporations were expected to sell the lands they were given at a substantial profit.

It has often been argued that a national infrastructure project as large as a transcontinental railway could never have been built without government assistance. The West Coast and western territories needed to be brought into the Union, some historians have argued, and the only way to achieve this was with government-supported railroads. Ironically, the same people who make this argument usually also claim that it would have been disastrous for the government to have owned the railroads it had made possible with its legislation, loans, and land grants. An undertaking of this scope and scale, they say, requires that corporations be given monopolies and grants of natural resources and public credit. These arguments make it seem inevitable that giant corporations taking huge gifts from the public sector were the only way for America to move forward and build a rail network. However, history shows that this was not the only way a national rail system could have been built.

There are numerous examples of rail systems built and managed by the public sector in foreign countries, especially during the nineteenth century when nearly every rail system outside the United States was state-owned and operated. However, for the sake of simplicity we will restrict the comparison to the United States. The Northern Pacific Railway, a private corporation chartered by Congress in 1864, built 6,800 miles of track to connect Lake Superior with Puget Sound. In return, the corporation was given 40 million acres of land in 50-mile checkerboards on either side of its tracks. Not only did the Northern Pacific rely on the government for land and financing, the railroad used the services of the U.S. Army to protect its surveyors and to move uncooperative Indians out of its way. When the Northern Pacific’s proposed route cut through the center of the Great Sioux Reservation, established by the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, the corporation pressured the government to break the treaty. George Custer announced that gold had been discovered in the Black Hills after an 1874 mission protecting Northern Pacific surveyors, and Washington let the treaty be disregarded by both the railroad and the prospectors. The Indians responded with the Great Sioux War of 1876, which culminated in the Battle of Little Big Horn, where Custer and his Seventh Cavalry were wiped out by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse leading a force of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors. But although the Indians won the battle, they lost the war. Less than a year later, Sioux leaders ceded the Black Hills to the United States in exchange for subsistence rations for their families on the reservation.

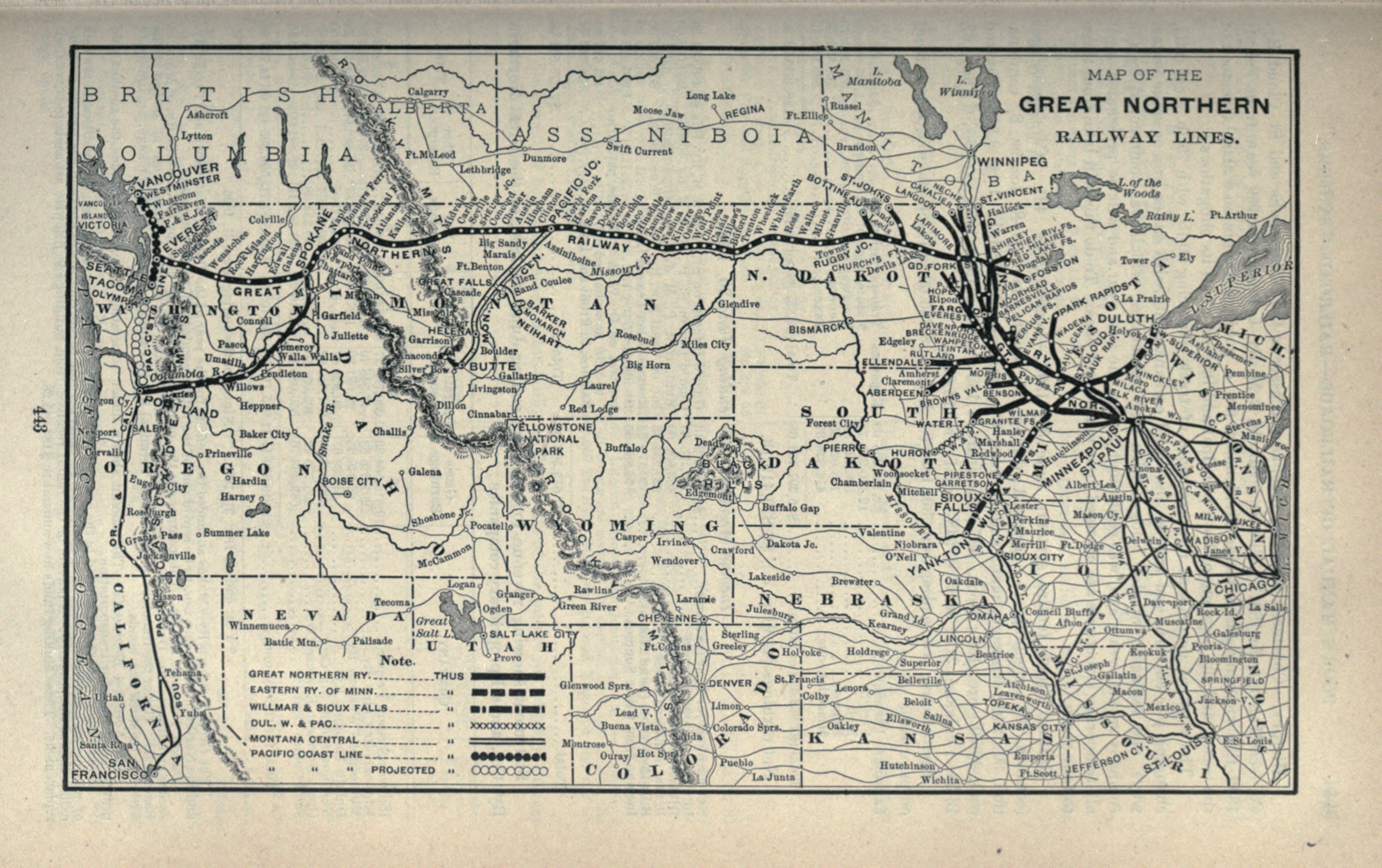

In contrast, Canadian-American railroad entrepreneur James Jerome Hill built his Great Northern Railroad line from St. Paul to Seattle during the last decades of the nineteenth century without causing a war and without receiving a single acre of free public land. The Great Northern bought land from the government to build its right of way and to resell to settlers. Hill claimed proudly that his railway was completed “without any government aid, even the right of way, through hundreds of miles of public lands, being paid for in cash.” The Great Northern system connected the Northwest with the rest of the nation through St. Paul, using a web of over 8,300 miles of track. And because Hill only built lines where traffic justified them rather than adding track just to collect free land, the Great Northern was one of the few transcontinental railroad companies to avoid bankruptcy in the Panic of 1893.

Regardless of the ways they were financed and built, the proliferation of railroads caused explosive growth. Chicago was a frontier village of 4,500 people in 1840. When Lincoln helped the Illinois Central receive the first land grant in 1851, the city’s population was about 30,000. Twenty years later Chicago was the center of a rapidly-growing railroad network, and the city held ten times the people. In 1880 Chicago’s population was over 500,000, and ten years later Chicago had over a million residents. We will take a closer look at the changes railroads brought to Chicago in a Chapter Seven.

Internal Combustion

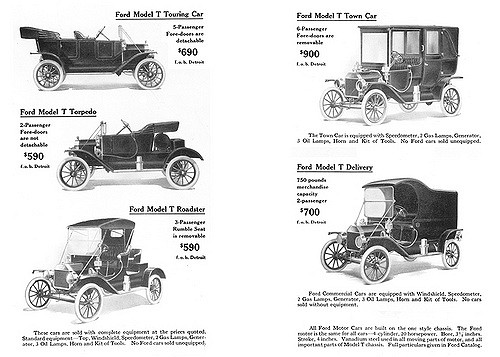

America’s transportation revolution did not end with steamboats and railroads and was not limited to public transportation technologies. The development of the automobile ushered in a new era of personal mobility for Americans. Internal combustion engines were inexpensive to mass produce and much easier to operate than steam engines. With the development of automobiles and trucks around the turn of the twentieth century, it no longer required a huge capital investment and a team of engineers to purchase and operate motorized transportation. Even the workers on Henry Ford’s assembly lines could aspire to owning their own Model Ts, especially after Ford doubled their wages to $5 a day in January 1914.

Engineers had experimented with building smaller machines using steam engines, and there were several examples in Europe and America of successful steam-powered farm tractors, trucks, and even a few horseless carriages. But internal combustion engines delivered much greater power relative to their mass, allowing smaller machines to do more work. The first internal combustion farm tractor was built by John Froehlich at his small Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Company in 1892. Others began applying internal combustion to farm equipment, and between 1907 and 1912 the number of tractors in American fields rose from 600 to 13,000. Eighty companies manufactured more than 20,000 tractors in 1913. After an auspicious beginning, Froehlich’s little Iowa company grew slowly and began building farm tractors in volume only after World War I. The Waterloo company built a good product, and was acquired by the John Deere Plow Company in 1918. Deere remains the world leader in self-propelled farm equipment.

The first internal combustion truck was built by Gottlieb Daimler in 1896, using an engine that had been developed by Karl Benz a year earlier. World War I spurred innovation and provided a ready market for internal combustion trucks that were much less expensive than their steam-powered rivals. By the end of the war gasoline-powered trucks had overtaken the steam truck market. Most large trucks now burn diesel fuel rather than gasoline, using a compression-ignition engine design patented by Rudolf Diesel in 1892.

Internal combustion trucks and tractors, like cars, allowed people to go farther, carry more, and do more work than had been possible using human and animal power. And they were much more affordable than comparable steam-based vehicles and easier to build at a scale that encouraged individual use and ownership. Trucking eventually challenged rail transport, especially after the development of semi-trailers and the Interstate Highway System. Although the first diesel truck engines only produced five to seven horsepower, they advanced quickly. Indiana mechanic Clessie Cummins built his first, six-horsepower diesel engine in 1919. The business bearing his name is now a global corporation doing $20 billion in annual business, mostly in diesel engines. Cummins’s current heavy truck engine is rated at 600 horsepower.

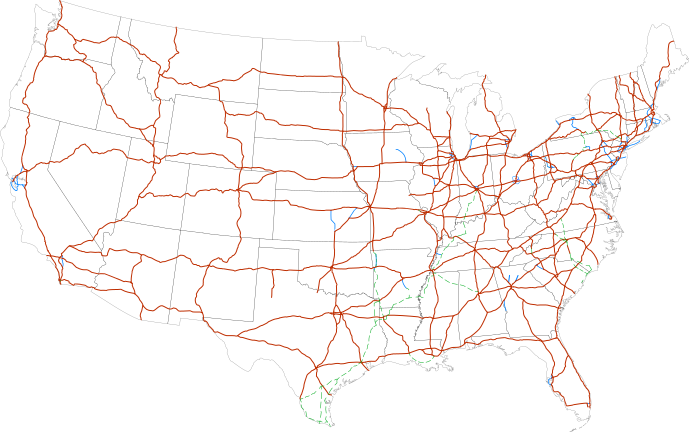

While it is easy to focus on the inventions and technological innovations of the internal combustion era, we should not lose sight of the infrastructure improvements that made these innovations valuable. Without paved roads to run on, there would have been far fewer cars and trucks and their impact on society and the environment would have been much different. The biggest road-building project in American history was the construction of the Interstate Highway System, financed by the Federal-Aid Highway Acts of 1944 and 1956. Unlike the transcontinental railroad project of the 1860s, the Interstate Highway System was paid for by the federal government and the roads are owned by the states. The system includes nearly 47,000 miles of highway, and the project was designed to be self-liquidating, so that the cost of the system did not contribute to the national debt. In addition to the Interstate System, American states, counties, cities and towns maintain systems of roads totaling nearly four million miles, about two-thirds of which are paved.

Gasoline vs. Ethanol

The economic trade-off of internal combustion for the farmers and teamsters who first adopted it was that speed and power came at a price. Where horses and oxen were readily available in farm communities and were cheap to maintain, tractors and trucks were a substantial investment. And unlike horses and oxen, tractors and trucks needed to be fueled with petroleum that made them dependent on a faraway industry. However, this dependence was not inevitable. Henry Ford and Charles Kettering, the chief engineer at General Motors, had both believed that as engine compression ratios increased, their companies’ engines would transition from gasoline to ethyl alcohol. We are all aware that the shift to ethanol did not happen, but why it did not is less well-known and may surprise you.

Most history books faithfully repeat the inaccurate story that Edwin Drake’s famous 1858 oil strike in Titusville Pennsylvania came just as the world was running out of expensive whale oil. Actually, there was a thriving market for alcohol fuel in the mid-nineteenth century United States. Ethanol was price-competitive with kerosene, and unlike kerosene it was produced by many small distillers, creating widespread competition that would continue to drive down prices. Unfortunately for ethanol producers and fuel consumers, the alcohol fuel industry was wiped out when the Lincoln administration imposed a $2.08 per gallon tax on distilled alcohol between 1862 and 1864. A gallon of Standard Oil kerosene still cost only 58 cents, so kerosene took over the American fuel market. Of course, after kerosene became the only available fuel, Standard Oil was free to raise prices as it saw fit.

But ethanol still had its advocates. The very first American internal combustion engine, built in 1826 by Samuel Morey, had used grain alcohol because it was inexpensive and readily available. Nearly a century later, Henry Ford’s Model T was designed to be convertible between kerosene, gasoline, and ethanol. General Motors chief engineer Kettering was convinced it was only a matter of time until ethanol became the fuel of choice.

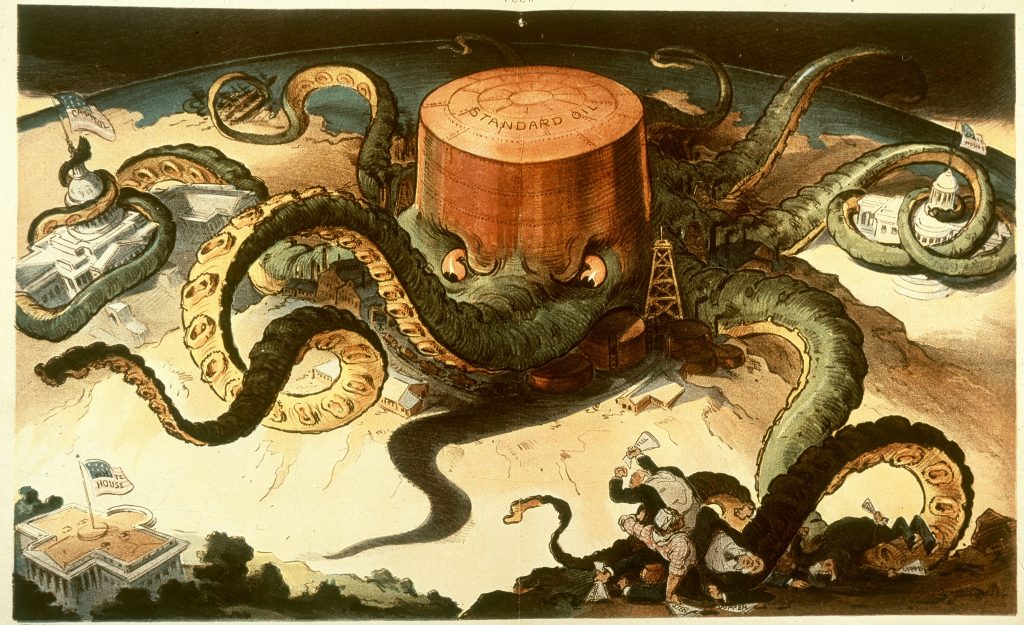

So why aren’t we all driving cars running renewable fuels? Part of the answer, as you have probably already guessed, is that Standard Oil made the auto industry an offer they couldn’t refuse. The oil company used its vast distribution network to make gasoline available everywhere it was needed, and insured that the price was so low that competitors could not profit if they entered the market. Standard Oil pioneered the practice of pricing below their cost of production to run competitors out of the business. The profits of the company’s many other divisions subsidized their short-term losses on gasoline. Predatory pricing was one of the principal charges made against the company in the 1911 antitrust case that resulted in the breakup of the Standard Oil Trust.

But Standard Oil’s predatory pricing does not tell the whole story of why we do not run cars on ethanol. The rest of the story, if anything, is even more sinister. It has long been known that using gasoline at high compression results in engine knocking. It was also well-known that ethanol did not knock. Charles Kettering at General Motors had argued for years that the “most direct route which we now know for converting energy from its source, the sun, into a material suitable for use as a fuel is through vegetation to alcohol.” The technology was simple and Americans had been distilling alcohol fuels for generations. Unfortunately, Kettering worked for a corporation whose major shareholder was the Du Pont family, who also happened to own the largest corporation in the chemical industry. It would be impossible for DuPont to profit or for General Motors to gain a competitive advantage using alcohol fuels, since the distilling technology was universally available and the product was un-patentable. However, there was an extremely profitable alternative.

Tetraethyl Lead (TEL) was a lubricating compound that could be added to gasoline to eliminate knocking. General Motors received a patent on its use as an anti-knock agent, and Standard Oil was granted a patent on its manufacture which was later extended to include DuPont. The three companies founded Ethyl Corporation to market TEL and other fuel additives. Unfortunately, lead is a powerful neurotoxin, linked to learning disabilities and dementia. The federal government had misgivings about allowing lead additives, and in 1925 the Surgeon General temporarily suspended TEL’s use and government scientists secretly approached Ford engineers seeking an alternative. In the 1930s, 19 federal bills and 31 state bills were introduced to promote alcohol use or blending. But the American Petroleum Industries Committee lobbied hard against them. Under intense industry pressure, the Federal Trade Commission even issued a restraining order forbidding commercial competitors from criticizing Ethyl gasoline as unsafe. By the mid-1930s, 90 percent of all gasoline contained TEL. Airborne lead pollution increased to over 625 times previous background levels, and the average IQ levels of American children dropped 7 points during the leaded-gas era. By the 1980s, over 50 million American children registered toxic levels of lead absorption and 5,000 Americans died annually of lead-induced heart disease. When public concern continued to increase, the Ethyl Corporation was sold in 1962 in the largest leveraged buyout of its time. In the 1970s the newly-established Environmental Protection Agency finally took the stand other federal agencies had been afraid to take. The EPA declared emphatically that airborne lead posed a serious threat to public health, and the government forced automakers and the fuel industry to gradually eliminate the use of lead. TEL is now illegal in automotive gasoline, although it is still used in aviation and racing fuels. Unleaded gasoline is now used in all new internal combustion cars. But while pure ethanol has powered most automobiles in Brazil since the 1970s, most Americans continue to use a blend containing just 10% ethanol to 90% gasoline.

Global Cargo

Two additional forms of transportation became increasingly important as the twentieth century ended and the twenty-first century began. Commercial airplanes are only a little over a hundred years old and the first air cargo and airmail shipments were flown in 1910 and 1911. Air cargo was considered too expensive for all but the most valuable shipments until express carriers such as UPS and Federal Express revolutionized the shipping business in the 1990s. The global economy now measures air freight volumes in ton-miles. In 2014, the world shipped more than 58 billion ton-miles of goods. Air freight also allows perishable items like fresh fruits and vegetables to be transported across oceans and continents from producers to consumers. This is a big business. Over 75 million tons of fresh produce are air-shipped annually, worth more than $50 billion.

For nonperishable items, container shipping has created a single global market. Standardized containers were invented by a trucker named Malcolm McLean, who realized it would save a lot of time and energy if his trucks didn’t need to be loaded and unloaded at the port, but could just be hoisted on and off a cargo ship. McLean refitted an oil tanker and made his first trip in 1956, carrying fifty-eight containers from Newark to Houston. Current annual shipping now exceeds 200 million semi-trailer sized containers. Containers can be shipped by sea, rail, truck, and even air, allowing just-in-time operators like Wal-Mart to manage a supply chain that relies much less on warehoused inventory, and more on product in transit.

But just as shifting from horse power to a gasoline truck or tractor a hundred years ago involved economic trade-offs, shopping at Wal-Mart today introduces a new level of dependence. We not only rely on transportation systems and the fuels they run on, but also on supply-chain software, international trade agreements and currency fluctuations, and even on the political situations of faraway nations. As long as the costs of inputs like fuel and infrastructure like ports, highways, and open borders remains low, the global market is a great deal for the consumer and a source of immense profits to businesses and their shareholders. But a company like Wal-Mart is just as dependent on factors it cannot control as its customers are. If any of these factors change, who will bear the cost?

https://youtu.be/N9gfTs3JnAk

Further Reading

Bill Kovarik, “Henry Ford, Charles Kettering and the Fuel of the Future,” Automotive History Review, Spring, 1998. Available online at www.environmentalhistory.org

Marc Levinson, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Larger, 2006.

Vaclav Smil, Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations or 1867-1914 and their Lasting Impact, 2005

George Rogers Taylor, The Transportation Revolution, 1815-1860, 1977.

Media Attributions

- World_airline_routes © Josullivan.59 is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- EmpressWalkLoblaws-Vivid © Raysonho is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2000_VA_Proof © US Mint is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pittsburgh_1795_large © Samuel W. Durant is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Erie-canal_1840_map © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Travel time 1800-30 © US Census adapted by Dan Allosso is licensed under a Public Domain license

- PSM_V12_D468_The_clermont_1807 © Popular Science is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Riverboats_at_Memphis © Detroit Publishing Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Travel time 1857 © US Census adapted by Dan Allosso is licensed under a Public Domain license

- PJM_1088_01 © Rand McNally adapted by Cornell University – PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Custer_Staghounds is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1897_Poor’s_Great_Northern_Railway © Poor's Manual is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3640769879_2b88ee74ce_z © THF24864 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Map_of_current_Interstates.svg © SPUI - National Atlas is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Earlyoilfield (1) © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Standard_oil_octopus_loc_color © Udo J. Keppler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- every-citizen-can-get-his-share-our-democratic-way-of-sharing-the-limited-amount-1024 © US Government is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Container_ships_President_Truman_(IMO_8616283)_and_President_Kennedy_(IMO_8616295)_at_San_Francisco © NOAA is licensed under a Public Domain license