9 The Road to Civil War

As we have already seen, the differences that led to the secession of the South and the Civil War were present from the start of the United States. Early compromises over the 3/5 provision of the Constitution and banning slavery in the Northwest Territory led to disagreements over issues like the states’ right to nullify federal laws. In this chapter we’ll look more closely at the escalating conflicts between the slaveholding South and the increasingly anti-slavery North and West.

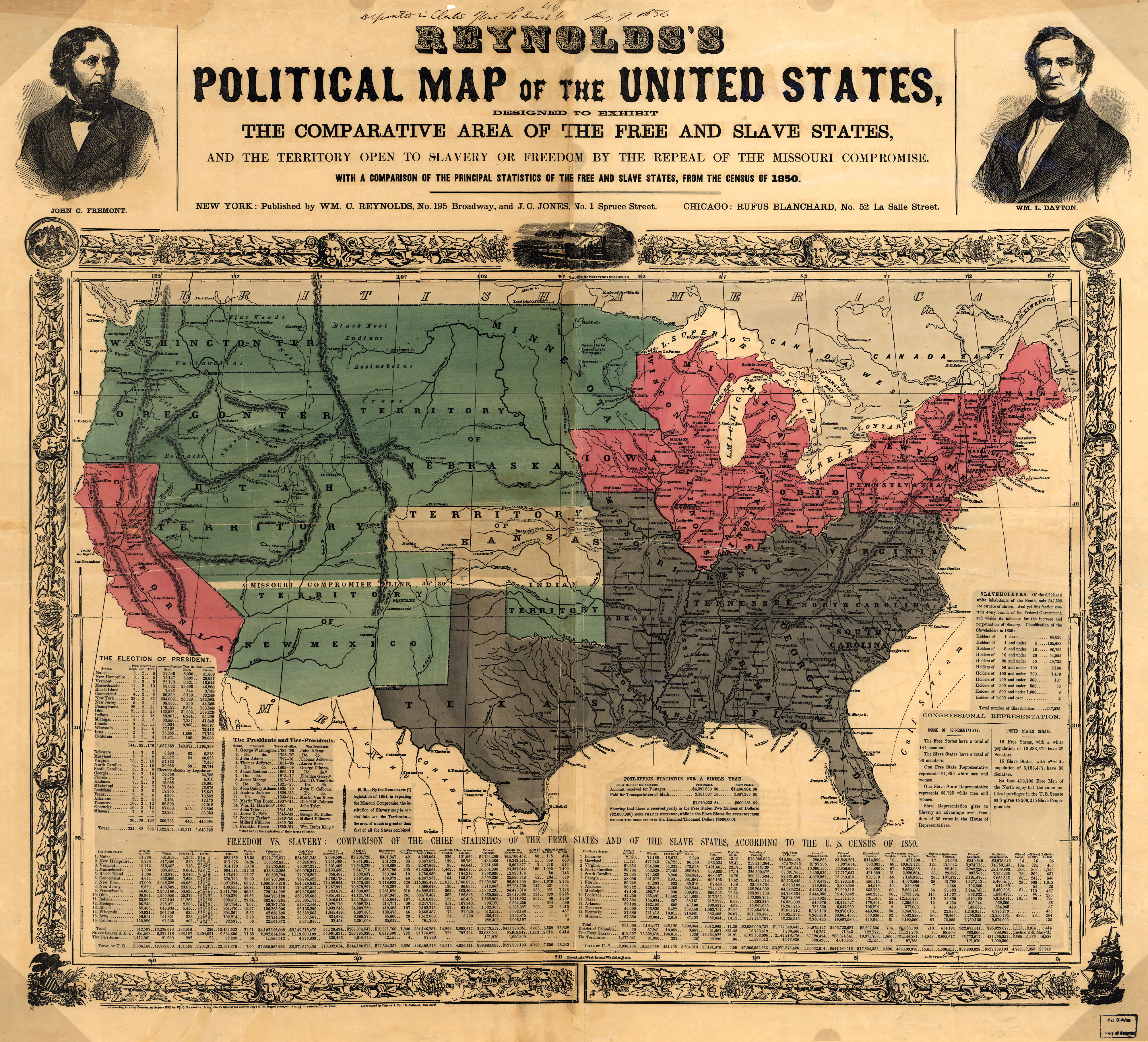

The admission of new states increased focus on the balance between supporters and opponents of slavery in government. In 1820, a bill called the Missouri Compromise allowed two new states to enter the Union simultaneously to keep the balance. Free-soil Maine and slaveholding Missouri would each get two senators and a small number of representatives until their populations increased. An additional clause in the law would prevent slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, excluding Missouri. President James Monroe signed it on March 6, 1820.

The Missouri Compromise was controversial at the time and many Americans worried that the country had become lawfully divided along sectional lines. Tejanos in northern Mexico were supported by southerners, especially after they achieved a degree of independence from anti-slavery Mexico in 1836. The annexation of Texas into the United States in 1845, which precipitated the Mexican-American War, also triggered another conflict over slave states. Congressman David Wilmot introduced an amendment called the Wilmot Proviso in August 1846 on a $2,000,000 appropriations bill intended for the final negotiations to resolve the war Americans believed would be over quickly. Wilmot’s rider would have banned slavery in all the territory the US acquired from Mexico. The appropriations bill with the Wilmot Proviso attached passed the House of Representatives but the Senate adjourned rather than debate it. It was reintroduced in February 1847 and again passed the House and failed in the Senate. In 1848, an attempt to make it part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo also failed. Sectional political disputes over slavery in the Southwest continued until the Compromise of 1850.

Antislavery northerners clung to the idea expressed in the 1846 Wilmot Proviso: slavery would not expand into the areas taken from Mexico. Though the proviso remained a proposal and never became a law, it defined the sectional division. The Free-Soil Party, which formed at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848 and included many members of the abolitionist Liberty Party, made this position the centerpiece of all its political activities, ensuring that the issue of slavery and its expansion remained at the front and center of American political debate. Supporters of the Wilmot Proviso and members of the new Free-Soil Party did not plan to abolish slavery in the states where it already existed, but Free-Soil advocates demanded that the western territories be kept free of slavery for the benefit of white settlers. They wanted to protect white workers from having to compete with slave labor in the West (Abolitionists, in contrast, looked to destroy slavery everywhere in the United States). Southern extremists, especially wealthy slaveholders, reacted with outrage at this effort to limit slavery’s expansion. They argued for the right to bring their slave property west, and they vowed to leave the Union if necessary to protect their way of life and ensure that the American empire of slavery would continue to grow.

The issue of what to do with the western territories added to the republic by the Mexican Cession consumed Congress in 1850. The border between Texas and New Mexico remained contested and the issue of California had not been resolved. California was the crown jewel of the Mexican Cession, and following the discovery of gold, it was flush with thousands of immigrants. By most estimates, however, it would be a free state, since the Mexican ban on slavery remained in force and slavery had not taken root in California.

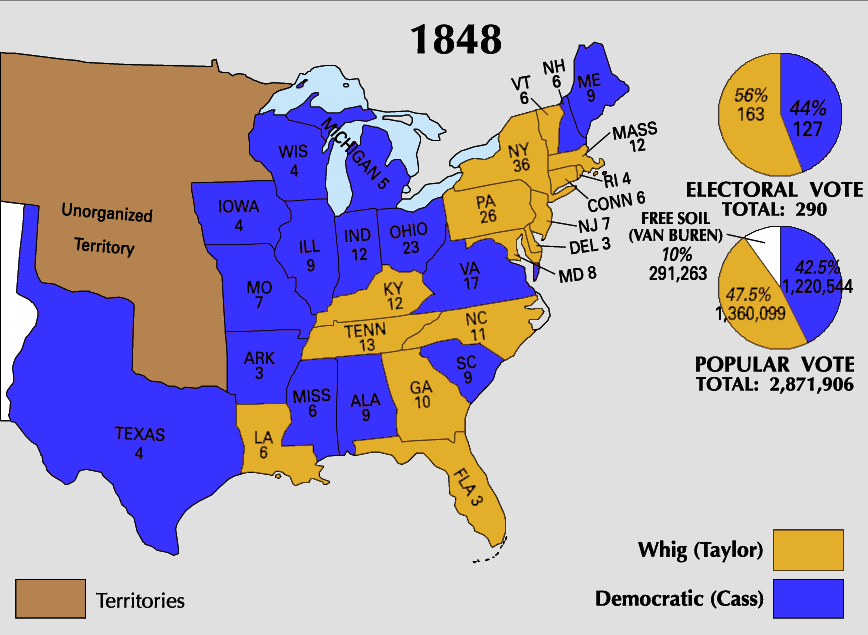

The presidential election of 1848 did little to solve the problems resulting from the Mexican Cession. The Democrats nominated Lewis Cass of Michigan, a supporter of popular sovereignty, or letting the people in the territories decide whether or not to permit slavery based on majority rule. The Whigs nominated General Zachary Taylor, a slaveholder who had achieved national prominence in the Mexican-American War. The fledgling Free-Soil Party put forward former president Martin Van Buren as their candidate. The Free-Soil Party attracted northern Democrats who supported the Wilmot Proviso, northern Whigs who rejected Taylor because he was a slaveholder, former members of the Liberty Party, and other abolitionists. The Free-Soil Party took votes away from Whigs and Democrats and helped to ensure Taylor’s election in 1848.

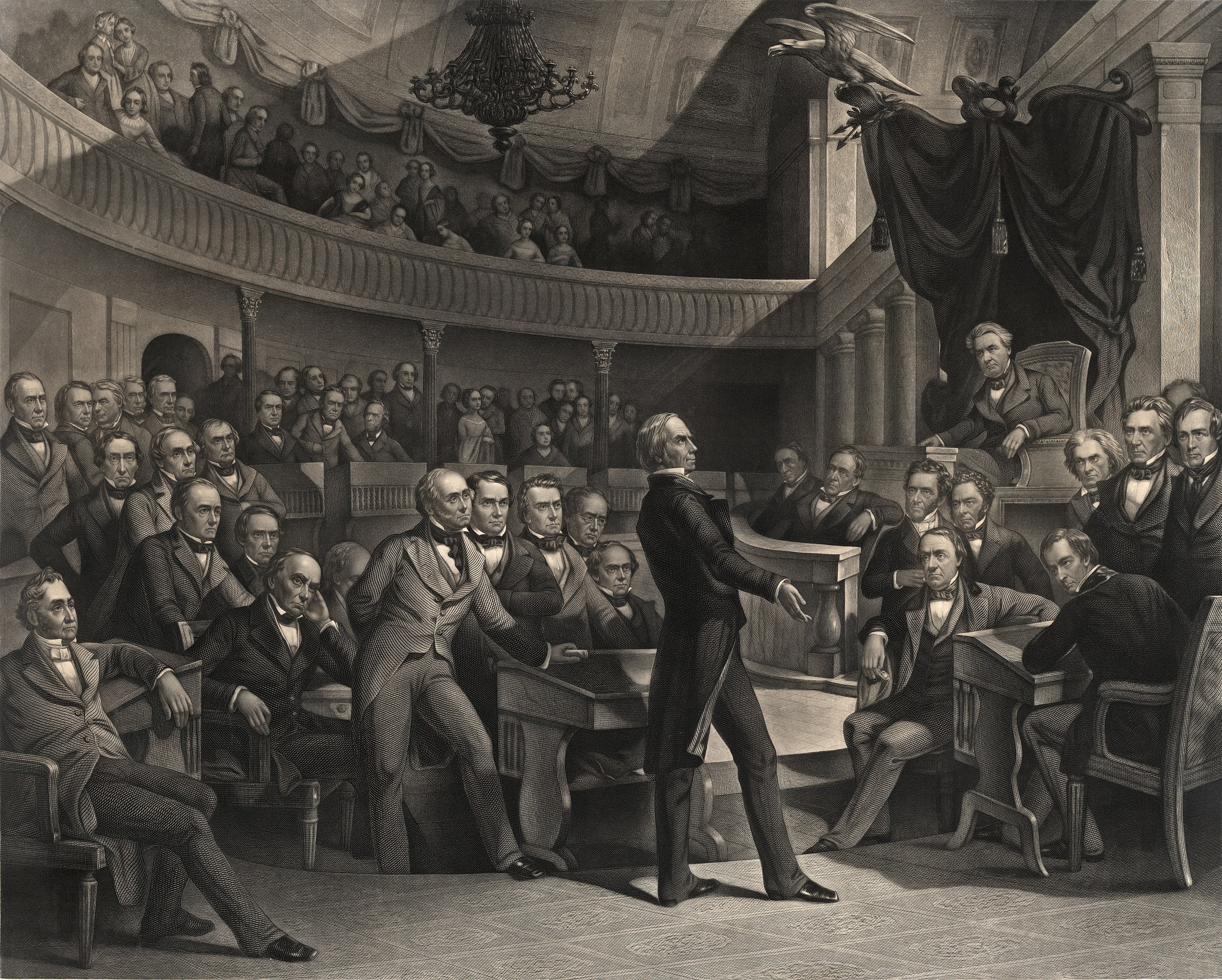

As president, Taylor sought to defuse the sectional controversy and preserve the Union. However, the California Gold Rush made California’s statehood into an issue demanding immediate attention. In 1849 California residents adopted a state constitution prohibiting slavery and President Taylor called on Congress to admit California and New Mexico as free states, a move that infuriated southern defenders of slavery. Taylor did not believe slavery could flourish in the arid lands of the Mexican Cession and proposed that the Wilmot Proviso be applied to the entire area. In Congress, Kentucky senator Henry Clay offered a series of resolutions addressing slavery and its expansion. Clay’s resolutions called for the admission of California as a free state; no restrictions on slavery in the rest of the Mexican Cession; a boundary between New Mexico and Texas that did not expand Texas; payment of outstanding Texas debts from the Lone Star Republic days; and the end of the slave trade but continuation of slavery in the nation’s capital; and a more robust federal fugitive slave law. Clay presented these proposals as an omnibus bill, that is, one that would be voted on its totality.

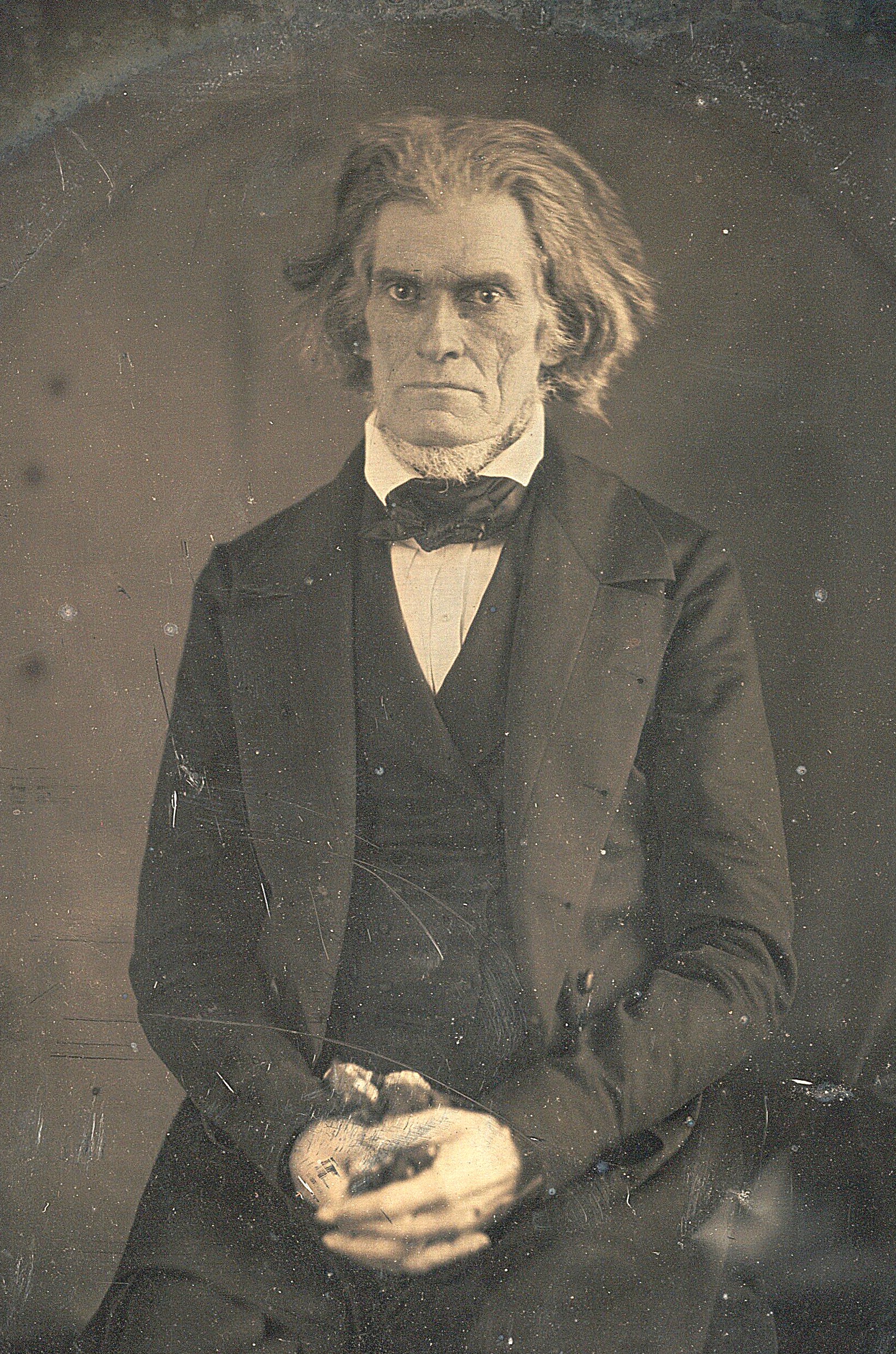

Clay’s proposals ignited angry debate that lasted eight months. Admitting California as a free state aroused the wrath of the aged and deathly ill John C. Calhoun, who had his friend Virginia senator James Mason present his assessment of Clay’s resolutions and the current state of sectional strife. Calhoun called for a vigorous federal law to ensure that runaway slaves were returned to their masters. He also proposed a constitutional amendment specifying a dual presidency—one office that would represent the South and another for the North. Calhoun’s argument portrayed an embattled South faced with continued northern aggression. Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster countered Calhoun and called for national unity, famously declaring that he spoke “not as a Massachusetts man, not as a Northern man, but as an American.” Webster asked southerners to end threats of disunion and requested that the North stop antagonizing the South by harping on the Wilmot Proviso. Like Calhoun, Webster also called for a new federal law to ensure the return of runaway slaves.

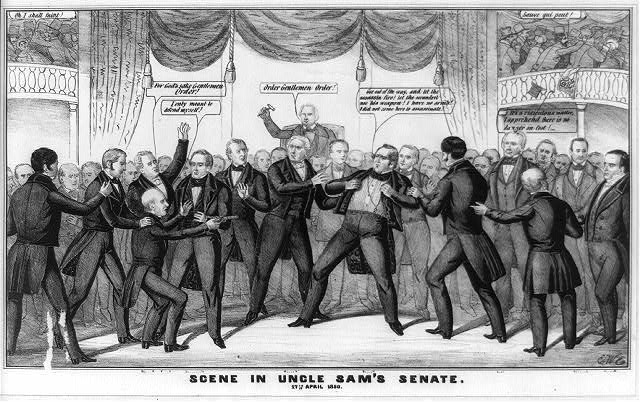

Webster’s efforts to compromise led many abolitionists to denounce him as a traitor. Whig senator William H. Seward of New York declared that slavery—which he characterized as incompatible with the assertion in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal”—would one day be extinguished in the United States. Seward’s speech invoked the idea of a higher moral law than the Constitution and secured his reputation in the Senate as an advocate of abolition. The American public followed the debates with great interest in newspapers. Colorful reports of wrangling in Congress further piqued public interest. It was not uncommon for arguments to devolve into fistfights or duels. One of the most astonishing episodes of the debate occurred in April 1850, when a quarrel erupted between Missouri Democratic senator Thomas Hart Benton and Mississippi Democratic senator Henry S. Foote. When the burly Benton advanced to assault Foote, the Mississippi senator drew his pistol.

President Taylor resented Henry Clay and disapproved of his resolutions. With neither side willing to budge, the government stalled on how to resolve the disposition of the Mexican Cession and the other issues of slavery. The drama only increased when in July 1850, when President Taylor abruptly died and Vice President Millard Fillmore became president. Unlike his predecessor, Fillmore worked with Congress to achieve a solution to the crisis of 1850. Clay stepped down as leader of the compromise effort and Illinois senator Stephen Douglas pushed five separate bills through Congress, collectively composing the Compromise of 1850. First, as advocated by the South, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, a law that provided for payment of federal “bounties” to slave-catchers. Second, to balance this concession to the South, Congress admitted California as a free state, a move that cheered antislavery advocates and abolitionists in the North. Third, Congress settled the contested boundary between New Mexico and Texas and the federal government paid the debts Texas had incurred as an independent republic. Fourth, antislavery advocates welcomed Congress’s ban on the slave trade in Washington, DC, although slavery continued to thrive in the nation’s capital. Finally, on the thorny issue of whether slavery would expand into the territories, Congress avoided making a direct decision and instead relied on the principle of popular sovereignty, allowing majorities in each territory to decide the territory’s laws. The compromise, however, further exposed the sectional divide as votes on the bills divided along strict regional lines.

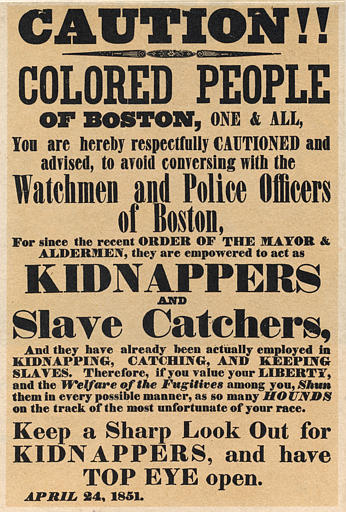

The hope that the Compromise of 1850 would resolve the sectional crisis proved short-lived when the Fugitive Slave Act turned into a major source of conflict. The federal law imposed heavy fines and prison sentences on people in the North and West who aided runaway slaves or refused to join posses to catch fugitives. Many northerners felt the law forced them to act as slave-catchers against their will. The law also established a new group of federal commissioners who would decide the fate of fugitives brought before them. In some instances, slave-catchers even brought in free northern blacks, prompting abolitionist societies to step up their efforts to prevent kidnappings. The commissioners had a financial incentive to send fugitives and free blacks to the slaveholding South, since they received ten dollars for every captive sent South and only five if they decided the person captured was actually free. The commissioners used no juries, and the alleged runaways could not testify in their own defense.

The law alarmed northerners and confirmed the existence of a “Slave Power” of elite slaveholders who wielded power over the federal government, shaping domestic and foreign policies to suit their interests. Despite southerners’ insistence on states’ rights, the Fugitive Slave Act showed that slaveholders were willing to use the power of the federal government to bend people in other states to their will. Although paranoid that federal power would restrict the expansion of slavery, southerners turned to the federal government to protect and promote the institution of slavery.

The actual number of slaves who were not captured within a year of escaping remained very low, perhaps no more than one thousand per year in the early 1850s. But southerners feared the influence of the Underground Railroad, a network of northern whites and free blacks who provided safe houses and secret escape routes from the South. Quakers were especially active in this network and historians believe that up to 100,000 slaves used the Underground Railroad. Many thousands of fugitives escaped the United States completely by going to southern Ontario, Canada.

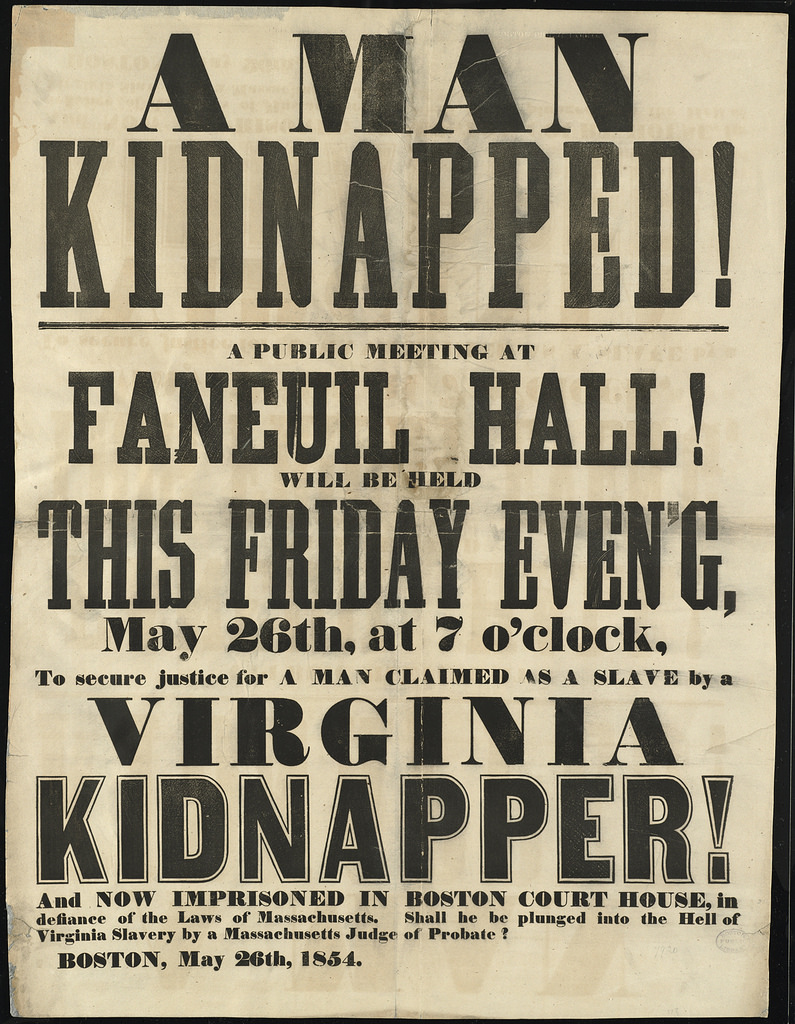

Some abolitionists, such as Frederick Douglass, believed that standing up against the Fugitive Slave Act necessitated violence. In Boston and elsewhere, abolitionists tried to protect fugitives from federal authorities. One case involved Anthony Burns, who had escaped slavery in Virginia in 1853 and made his way to Boston. When federal officials arrested Burns in 1854, abolitionists staged a series of mass demonstrations and a confrontation at the courthouse. Despite their best efforts, however, Burns was returned to Virginia when President Franklin Pierce supported the Fugitive Slave Act with federal troops. Boston abolitionists eventually bought Burns’s freedom. For many northerners, however, the Burns incident, combined with Pierce’s response, only amplified their sense of a conspiracy of southern power.

The backlash against the Fugitive Slave Act, fueled by Uncle Tom’s Cabin and well-publicized cases like that of Anthony Burns, resulted in personal liberty laws being passed in eight northern states declaring that the state would provide legal protection to anyone arrested as a fugitive slave, including the right to trial by jury. The personal liberty laws demonstrated the North’s use of states’ rights in opposition to federal power but furthered southerner claims that northerners had no respect for the Fugitive Slave Act or slaveholders’ property rights.

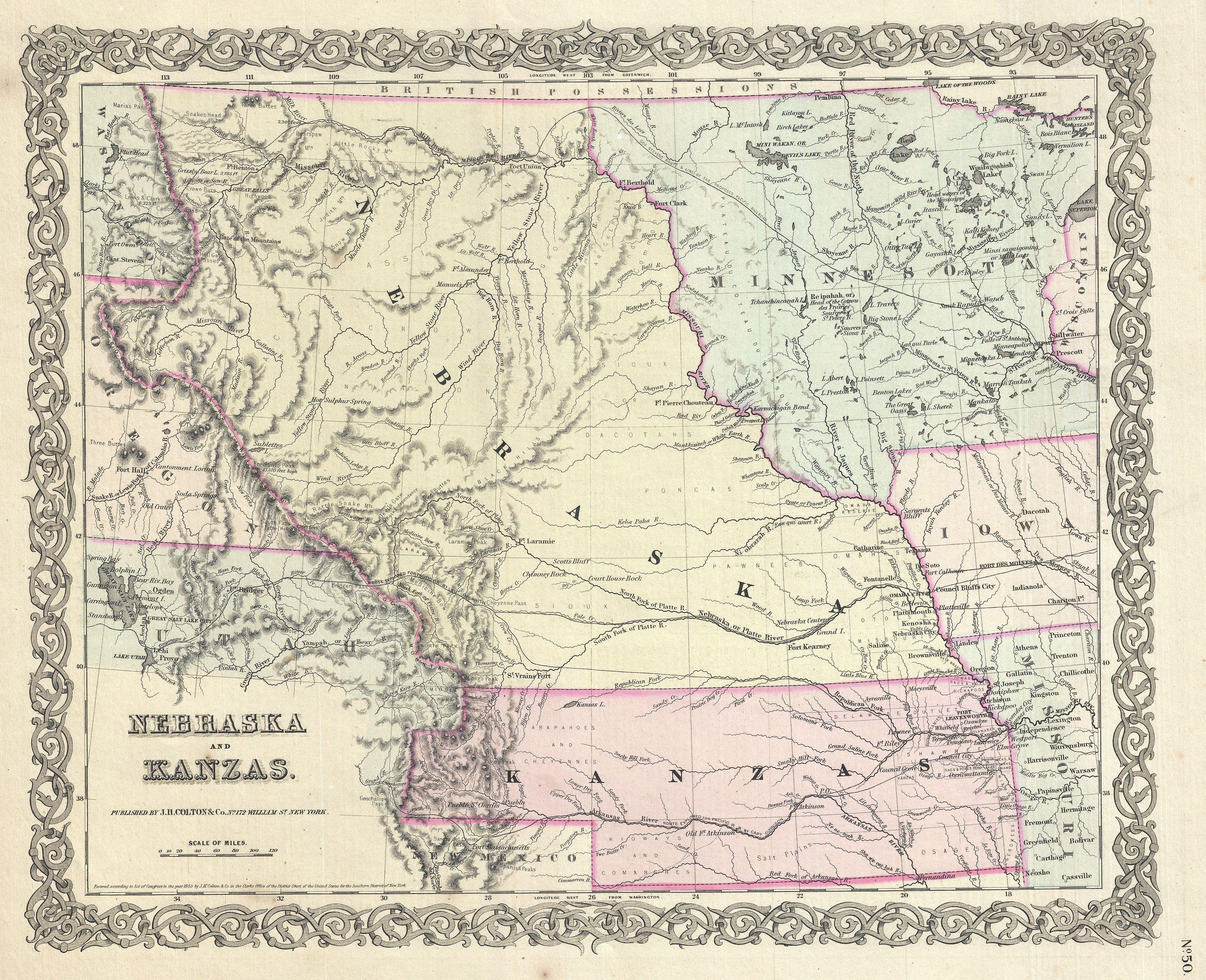

The relative calm following the Compromise was broken in 1854 over slavery in the territory of Kansas. Pressure had been building among northern farmers, who wanted the federal government to organize the territory west of Missouri and Iowa, which had been admitted to the Union as a free state in 1846. Promoters of a transcontinental railroad also lobbied for westward expansion. Southerners were growing resentful of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which established the 36° 30′ parallel as the geographical boundary of slavery on the north-south axis. Proslavery southerners now contended that popular sovereignty should apply to all territories, not just Utah and New Mexico. They argued for the right to bring their slave property wherever they chose.

As factions agitated for the settlement of Kansas and Nebraska, Democratic Illinois senator Stephen Douglas believed he had found a solution—the Kansas-Nebraska bill—that would promote party unity and also satisfy his colleagues from the South, who detested the Missouri Compromise line. In January 1854, Douglas introduced the bill. The act created two territories: Kansas, directly west of Missouri; and Nebraska, west of Iowa, and applied the principle of popular sovereignty. Douglas hoped his bill would increase his political capital and provide a step forward on his quest for the presidency. Douglas also wanted the territory organized in hopes of placing the eastern terminus of a transcontinental railroad in Chicago, rather than St. Louis or New Orleans.

After heated debates, Congress narrowly passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The Democrats divided along sectional lines as a result of the bill, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act gave rise to the Republican Party, a new political party that attracted northern Whigs, Democrats who shunned the Kansas-Nebraska Act, members of the Free-Soil Party, and assorted abolitionists. The new Republican Party pledged itself to preventing the spread of slavery into the territories and railed against the Slave Power, infuriating the South. As a result, the party became a solidly northern political organization. As never before, the U.S. political system was polarized along sectional fault lines.

In 1855 and 1856, pro- and antislavery activists flooded Kansas with the intention of influencing the popular-sovereignty decision on slavery in the territories. Proslavery Missourians who crossed the border to vote in Kansas became known as border ruffians, winning territorial elections through voter fraud and illegal vote counting (by some estimates, up to 60 percent of the votes cast in Kansas were fraudulent). Once in power, the proslavery legislature, meeting at Lecompton, Kansas, drafted a proslavery constitution known as the Lecompton Constitution. It was supported by President Buchanan, but opposed by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. The majority in Kansas, however, were Free-Soilers who had come from New England to ensure a numerical advantage over the border ruffians. The New England Emigrant Aid Society, a northern antislavery group, helped fund these efforts to halt the expansion of slavery into Kansas and beyond.

The Lecompton Constitution

Kansas was home to no fewer than four state constitutions in its early years. Its first constitution, the Topeka Constitution, would have made Kansas a free-soil state. A proslavery legislature, however, created the 1857 Lecompton Constitution to enshrine the institution of slavery in the new Kansas-Nebraska territories. In January 1858, Kansas voters defeated the proposed Lecompton Constitution, excerpted below, with an overwhelming margin of 10,226 to 138.

ARTICLE VII.—SLAVERY

SECTION 1. The right of property is before and higher than any constitutional sanction, and the right of the owner of a slave to such slave and its increase is the same and as inviolable as the right of the owner of any property whatever.

SEC. 2. The Legislature shall have no power to pass laws for the emancipation of slaves without the consent of the owners, or without paying the owners previous to their emancipation a full equivalent in money for the slaves so emancipated. They shall have no power to prevent immigrants to the State from bringing with them such persons as are deemed slaves by the laws of any one of the United States or Territories, so long as any person of the same age or description shall be continued in slavery by the laws of this State: Provided, That such person or slave be the bona fide property of such immigrants.

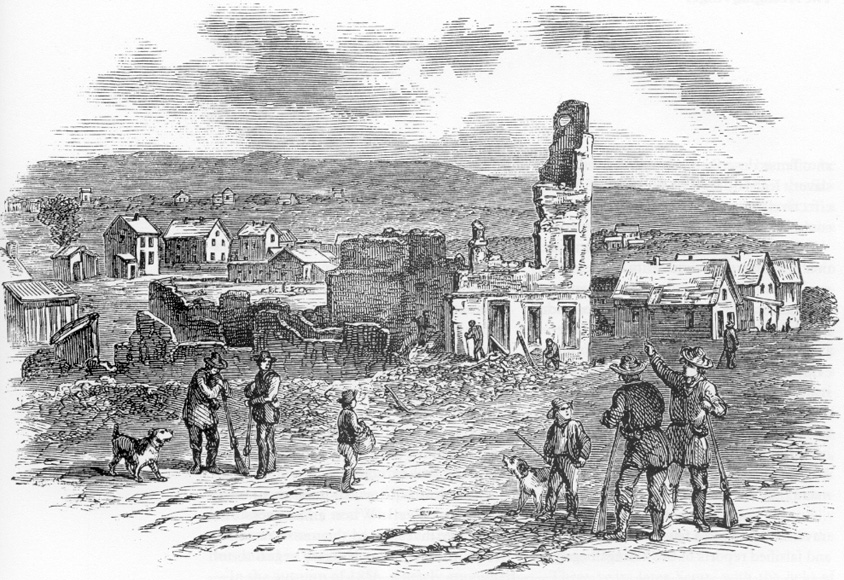

In 1856, clashes between antislavery Free-Soilers and border ruffians came to a head in Lawrence Kansas, a town founded by the New England Emigrant Aid Society. Proslavery emigrants from Missouri were equally determined that no “abolitionist tyrants” or “negro thieves” would control the territory. In the spring of 1856, several of Lawrence’s leading antislavery citizens were indicted for treason, and federal marshal Israel Donaldson called for a posse to help make arrests. He did not have trouble finding volunteers from Missouri. When the posse, which included Douglas County sheriff Samuel Jones, arrived outside Lawrence, the antislavery town’s “committee of safety” agreed on a policy of nonresistance. Most of those who were indicted fled. Donaldson arrested two men without incident and dismissed the posse.

However, Jones, who had been shot during an earlier confrontation in the town, did not leave. On May 21, falsely claiming that he had a court order to do so, Jones took command of the posse and rode into town armed with rifles, revolvers, cutlasses and bowie knives. The posse smashed the presses of the two newspapers, Herald of Freedom and the Kansas Free State, and burned down the deserted Free State Hotel. The next morning, a man named John Brown and his sons, who were on their way to provide Lawrence with reinforcements, heard the news of the attack. Disappointed that the citizens of Lawrence had not resisted the “slave hounds” of Missouri, Brown opted not to go to Lawrence, but to the homes of proslavery settlers near Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas. The group of seven, including Brown’s four sons, announced they were the “Northern Army” that had come to serve justice. They burst into the cabin of proslavery Tennessean James Doyle and captured him and two of his sons. One hundred yards down the road, Owen and Salmon Brown hacked their captives to death with swords and John Brown put a bullet in Doyle’s forehead. Before the night was done, the Browns raided two more cabins and executed two other proslavery settlers. None of those executed owned any slaves or had had anything to do with the raid on Lawrence.

Brown’s actions precipitated a new wave of violence. Guerrilla warfare between proslavery “border ruffians” and antislavery forces, which escalated during the Civil War, resulted in over 150 deaths. The events in Kansas served as an extreme reply to Douglas’s proposition of popular sovereignty. As the violent clashes increased, Kansas became known as “Bleeding Kansas.” Antislavery advocates’ use of force carved out a new direction for some who opposed slavery. Distancing themselves from William Lloyd Garrison and other pacifists, Brown and fellow abolitionists believed the time had come to fight slavery with violence.

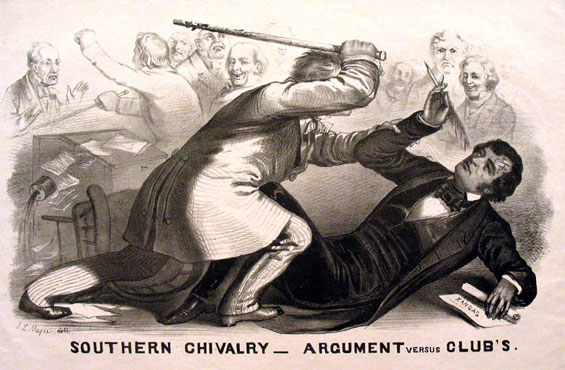

The violent hostilities associated with Bleeding Kansas were not limited to Kansas itself. The notorious “Caning of Sumner” in May 1856 followed upon a speech given by Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner in which he condemned slavery, declaring that admitting Kansas as a slave state was “the rape of a virgin territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of slavery; and it may be clearly traced to a depraved longing for a new slave state, the hideous offspring of such a crime, in the hope of adding to the power of slavery in the national government.” Sumner criticized proslavery legislators, particularly attacking a fellow senator and relative of Preston Brooks. Brooks responded by beating the unarmed Sumner with a cane, a thrashing that southerners celebrated as a manly defense of gentlemanly honor and their way of life. Brooks did not challenge Sumner to a duel; by choosing to beat him with a cane instead, he made it clear that he did not consider Sumner a gentleman. Many in the South rejoiced over Brooks’s defense of slavery, southern society, and family honor, sending him hundreds of canes to replace the one he had broken assaulting Sumner. The attack by Brooks nearly killed Sumner and left him incapacitated physically and mentally for a long period of time. Despite his injuries, the people of Massachusetts reelected him.

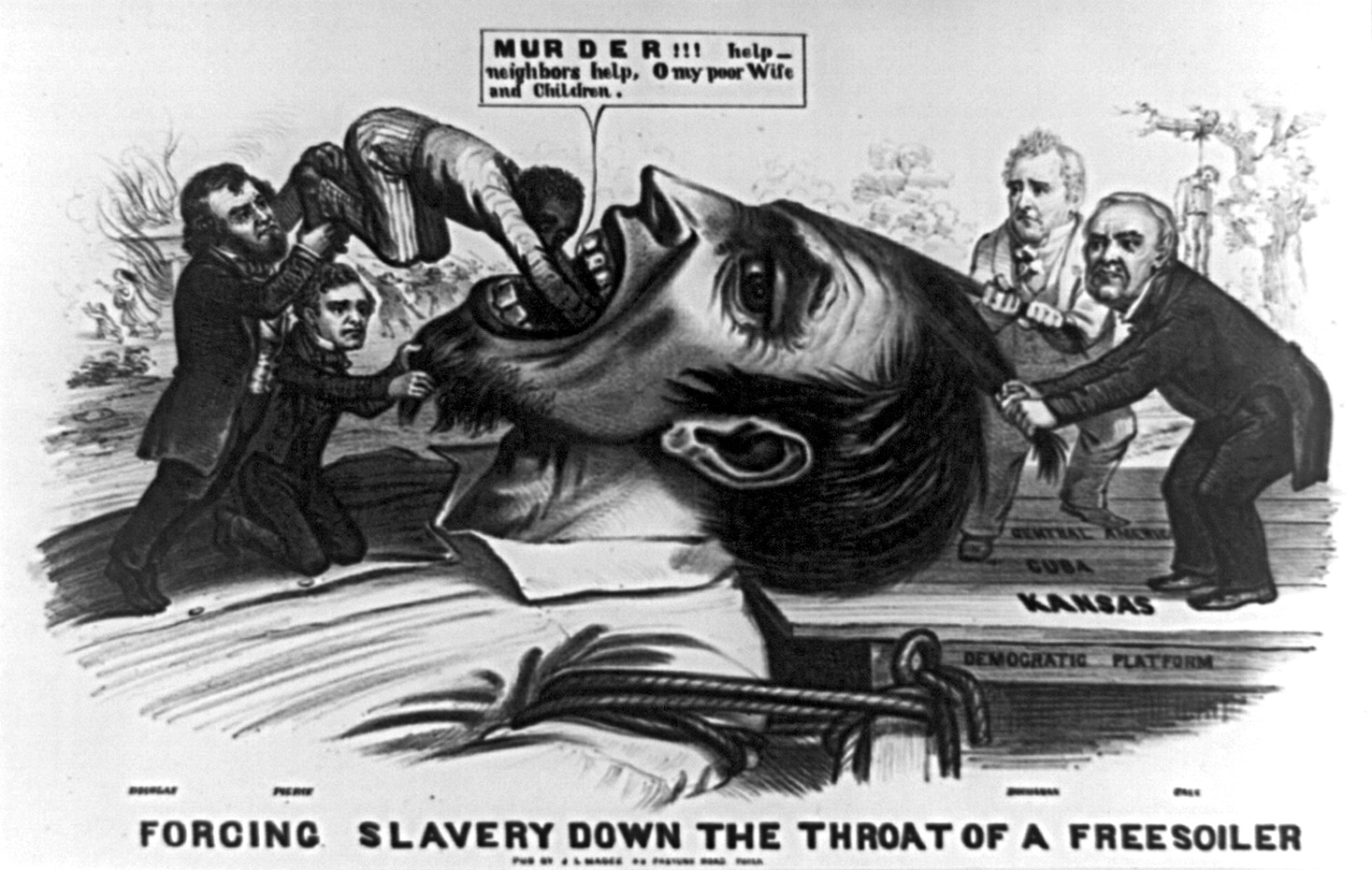

The electoral contest in 1856 took place in a transformed political landscape. A third political party appeared: the anti-immigrant American Party, a formerly secretive organization with the nickname “the Know-Nothing Party” because its members denied knowing anything about it. By 1856, the American or Know-Nothing Party had evolved into a national force committed to halting further immigration. Its members were especially opposed to the immigration of Irish Catholics and of laborers from China, who were thought to be too foreign to ever assimilate into a white America. The election also featured the new Republican Party, which offered John C. Fremont as its candidate. Republicans accused the Democrats of trying to nationalize slavery through the use of popular sovereignty in the West, a view captured in the 1856 political cartoon Forcing Slavery Down the Throat of a Free Soiler. The cartoon features the image of a Free-Soiler settler tied to the Democratic Party platform while Senator Douglas (author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act) and President Pierce force a slave down his throat.

The Democrats offered James Buchanan as their candidate. Buchanan’s qualification, in the minds of many, was that he had been out of the country when the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed. Buchanan won the election, but Fremont garnered more than 33 percent of the popular vote, an impressive return for a new party. The Whigs had been replaced by the Republican Party. Know-Nothings also transferred their allegiance to the Republicans because the new party also took an anti-immigrant stance, a move that further boosted the new party’s standing. (The Democrats courted the Catholic immigrant vote.) The Republican Party was a thoroughly northern party; no southern delegate voted for Fremont.

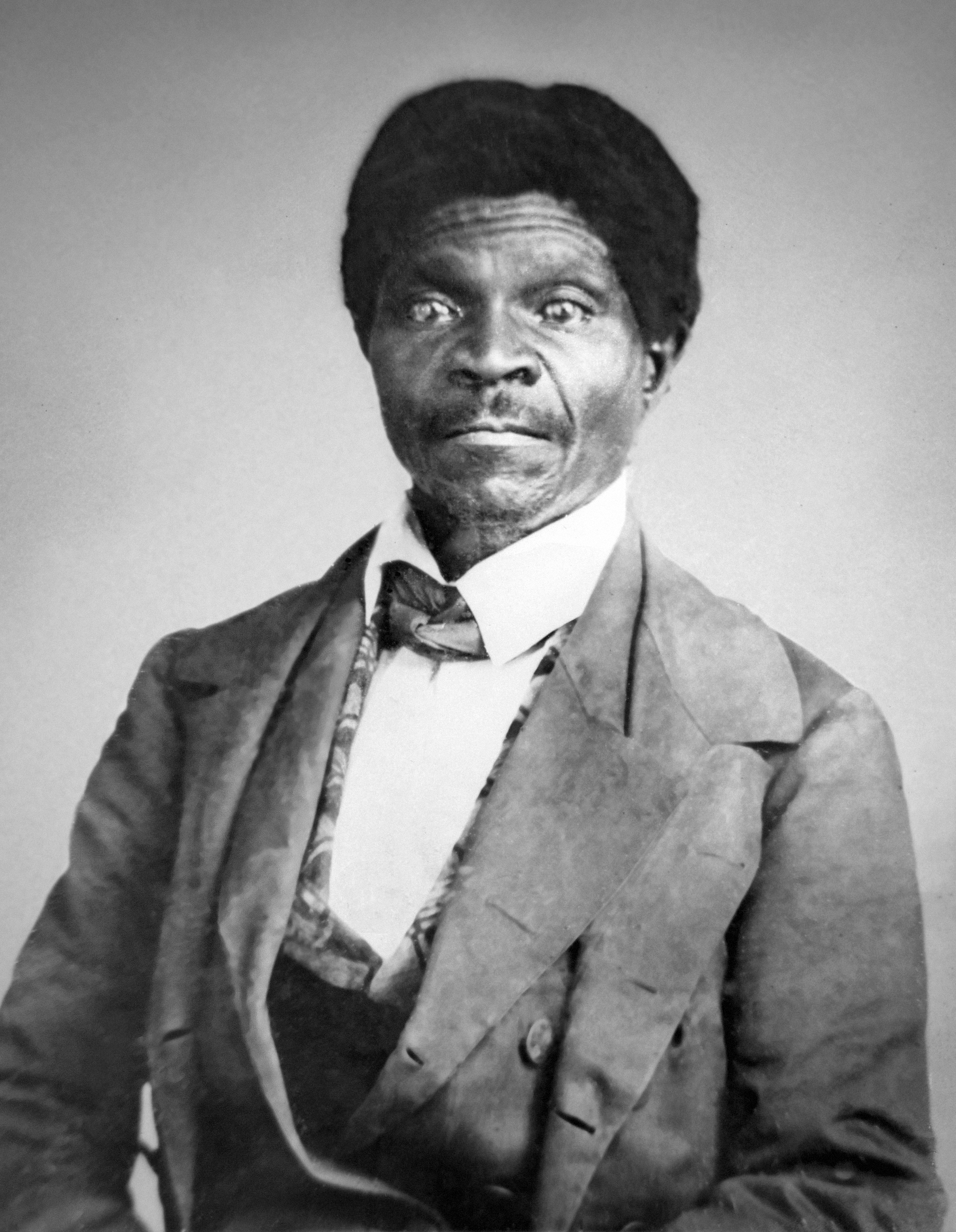

In 1857, several months after President Buchanan took the oath of office, the Supreme Court heard the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford. Scott, born a slave in Virginia in 1795, had been taken to Missouri, where slavery had been adopted as part of the Missouri Compromise. In 1820, Scott’s owner took him first to Illinois and then to the Wisconsin territory. However, both of those regions were part of the Northwest Territory, where the 1787 Northwest Ordinance had prohibited slavery. When Scott returned to Missouri, he attempted to buy his freedom. After his owner refused, he sought relief in the state courts, arguing that by virtue of having lived in areas where slavery was banned, he should be free.

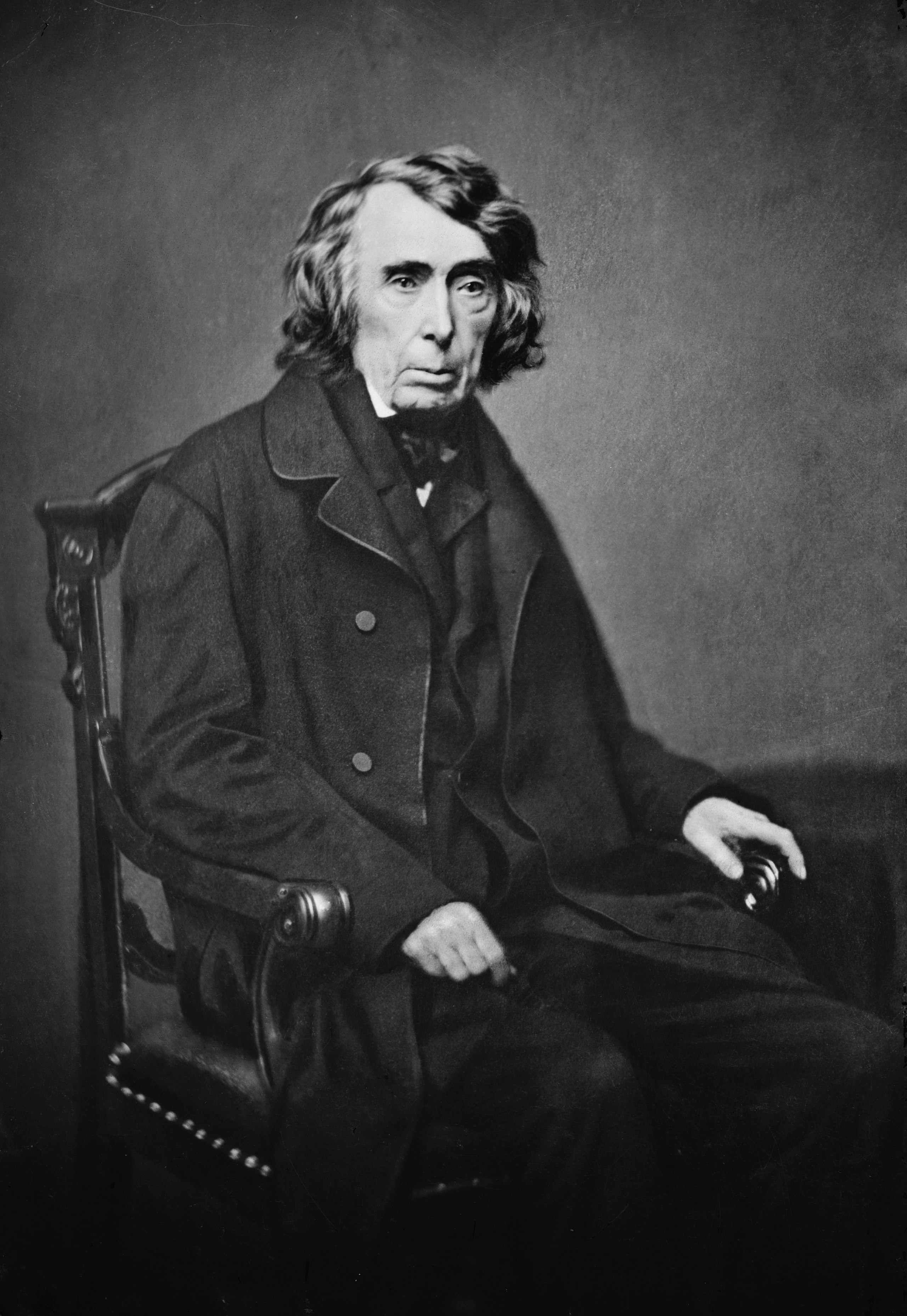

In a complicated set of legal decisions, a jury found that Scott, along with his wife and two children, were free. However, on appeal from Scott’s owner, the state Superior Court reversed the decision, and the Scotts remained slaves. In 1857, the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Roger Taney, a former slaveholder who had freed his slaves, handed down its decision. On the question of whether Scott was free, the Supreme Court decided he remained a slave. Taney then went beyond the specific issue of Scott’s freedom to make a sweeping and momentous judgment about the status of blacks, both free and slave. Per the court, blacks could never be citizens of the United States. Further, the court ruled that Congress had no authority to stop or limit the spread of slavery into American territories. This proslavery ruling explicitly made the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional; implicitly, it made Douglas’s popular sovereignty unconstitutional.

Roger Taney on Dred Scott v. Sandford

A free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a “citizen” within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States. . . .

The only two clauses in the Constitution which point to this race treat them as persons whom it was morally lawfully to deal in as articles of property and to hold as slaves. . . .

Every citizen has a right to take with him into the Territory any article of property which the Constitution of the United States recognises as property. . . .

The Constitution of the United States recognises slaves as property, and pledges the Federal Government to protect it. And Congress cannot exercise any more authority over property of that description than it may constitutionally exercise over property of any other kind. . . .

Prohibiting a citizen of the United States from taking with him his slaves when he removes to the Territory . . . is an exercise of authority over private property which is not warranted by the Constitution, and the removal of the plaintiff [Dred Scott] by his owner to that Territory gave him no title to freedom.

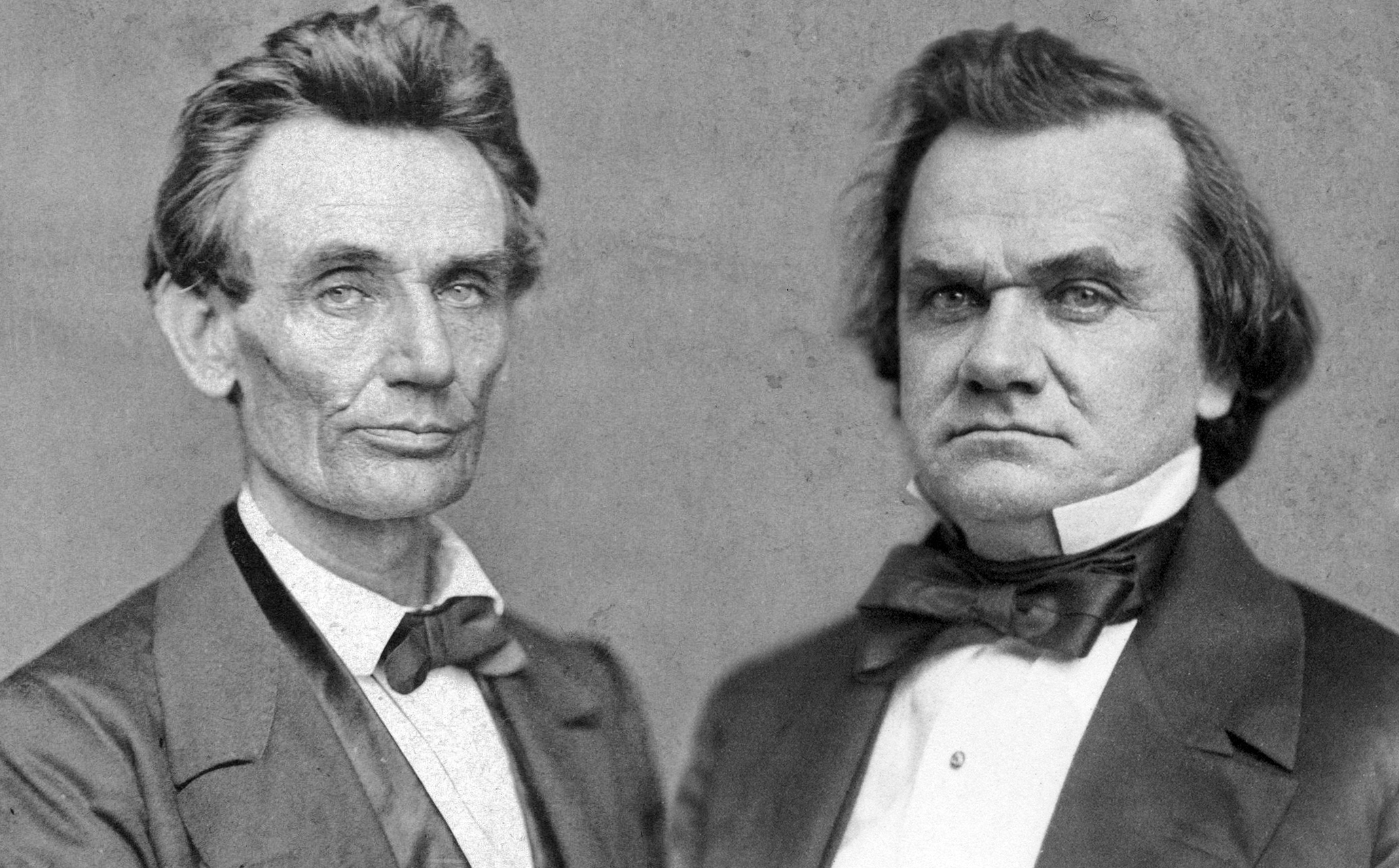

The turmoil in Kansas combined with the furor over the Dred Scott decision to form a background for the 1858 senatorial contest in Illinois between Democratic senator Stephen Douglas and Republican hopeful Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln and Douglas engaged in seven debates before huge crowds that met to hear the two men argue the central issue of slavery and its expansion. Newspapers throughout the United States published their speeches. Whereas Douglas already enjoyed national recognition, Lincoln remained largely unknown before the debates. These appearances provided an opportunity for him to raise his profile with both northerners and southerners.

Douglas portrayed the Republican Party as “black Republicans” who posed a dangerous threat to the Constitution. Because Lincoln declared the nation could not survive if the slave state–free state division continued, Douglas claimed the Republicans aimed to destroy what the founders had created. For his part, Lincoln said: “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half Slave and half Free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction: or its advocates will push it forward till it shall became alike lawful in all the States—old as well as new, North as well as South.” Lincoln interpreted the Dred Scott decision and the Kansas-Nebraska Act as efforts to nationalize slavery: that is, to make it legal everywhere from New England to the Midwest and beyond.

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

On August 21, 1858, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas met in Ottawa Illinois for the first of seven debates. People streamed into Ottawa from as far away as Chicago. Reporting on the event was strictly partisan, with each of the candidates’ supporters claiming victory for their candidate. In this excerpt, Lincoln addresses the issues of equality between blacks and whites.

[A]nything that argues me into his idea of perfect social and political equality with the negro, is but a specious and fantastic arrangement of words…I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so. I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality…I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position…[N]otwithstanding all this, there is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I hold that he is as much entitled to these as the white man…[I]n the right to eat the bread, without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man.

—Lincoln’s speech on August 21, 1858, in Ottawa, Illinois

During the debates, Lincoln questioned whether or not Douglas believed that the 1857 Supreme Court decision in the Dred Scott case trumped the right of a majority to prevent the expansion of slavery under the principle of popular sovereignty. Douglas responded during the second debate at Freeport, Illinois. In what became known as the Freeport Doctrine, Douglas upheld popular sovereignty, declaring: “It matters not what way the Supreme Court may hereafter decide as to the abstract question whether slavery may or may not go into a territory under the Constitution, the people have the lawful means to introduce it or exclude it as they please.” The Freeport Doctrine antagonized southerners and caused a major rift in the Democratic Party. The doctrine did help Douglas in Illinois, however, where most voters opposed the further expansion of slavery. The Illinois legislature selected Douglas over Lincoln for the senate, but the debates launched Lincoln into the national spotlight. Lincoln had argued that slavery was morally wrong, even as he accepted the racism inherent in slavery. He warned that Douglas and the Democrats would nationalize slavery through the policy of popular sovereignty. Though Douglas survived the senate election challenge from Lincoln, his Freeport Doctrine damaged the political support he needed from the Southern Democrats. This caused him to lose the following presidential election, undermining the Democratic Party as a national force.

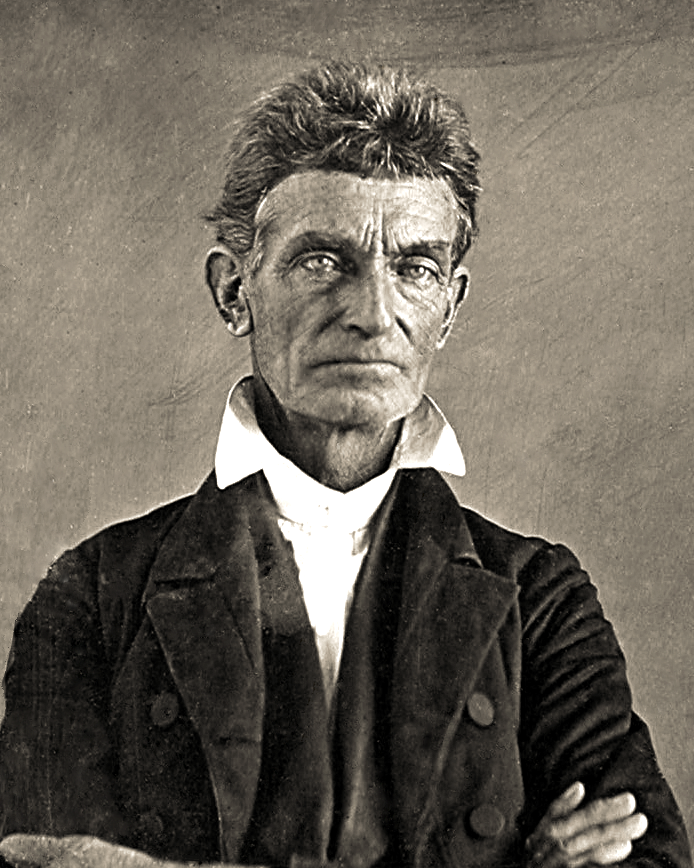

In October 1859, the radical abolitionist John Brown and eighteen armed men, both blacks and whites, attacked the federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry Virginia. They hoped to capture the weapons there and distribute them among slaves to begin an uprising that would bring an end to slavery. Brown had already demonstrated during the 1856 Pottawatomie attack in Kansas that he had no patience for the nonviolent approach preached by pacifist abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison. Born in Connecticut in 1800, Brown spent much of his life in the North, moving from Ohio to Pennsylvania and then upstate New York as his various business ventures failed. To him, slavery appeared an unacceptable evil that must be purged from the land, and like his Puritan forebears, he believed in using the sword to defeat the ungodly. Brown told other abolitionists of his plan to take Harpers Ferry Armory and initiate a slave uprising. Some abolitionists provided financial support, while others, including Frederick Douglass, found the plot suicidal and refused to join. On October 16 1859, Brown’s force easily took control of the federal armory, which was unguarded. However, his vision of a mass uprising failed completely. Very few slaves lived in the area to rally to Brown’s side, and the group found themselves holed up in the armory’s engine house with townspeople taking shots at them. Federal troops, commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee, soon captured Brown and his followers. On December 2, Brown was hanged by the state of Virginia for treason.

John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry and his subsequent execution generated intense reactions in both the South and the North. Southerners grew apprehensive of the possibility of other violent plots. They viewed Brown as a terrorist bent on destroying their civilization, and support for secession grew. Anxiety led several southern states to pass laws designed to prevent slave rebellions. Southerners also feared a hostile majority in the national government that would stop at nothing to destroy slavery. Was it possible, one resident of Maryland asked, to “live under a government, a majority of whose subjects or citizens regard John Brown as a martyr and Christian hero?” Many antislavery northerners did in fact consider Brown a martyr to the cause, and those who viewed slavery as a sin saw easy comparisons between him and Jesus Christ.

The election of 1860 threatened American democracy when the elevation of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency inspired secessionists in the South to withdraw their states from the Union. Lincoln’s election owed much to disarray in the Democratic Party. The Dred Scott decision and the Freeport Doctrine had opened wide sectional divisions among Democrats. Southerners vowed to prevent a northern Democrat, especially Illinois’s Stephen Douglas, from becoming their presidential candidate. Proslavery zealots insisted on a southern Democrat. Northern Democrats nominated Stephen Douglas, while southern Democrats, who met separately, put forward Vice President John Breckinridge from Kentucky. The Democratic Party had fractured into two competing sectional factions.

By offering two candidates for president, the Democrats gave the Republicans an enormous advantage. And to make matters worse for the South, pro-Unionists from the border states hoping to prevent a Republican victory organized the Constitutional Union Party and ran a fourth candidate. John Bell pledged to end slavery agitation and preserve the Union but never fully explained how he would accomplish this objective. The Republicans nominated Lincoln, and in the November election, he garnered a mere 40 percent of the popular vote, though he won every northern state except New Jersey. Lincoln’s name was blocked from even appearing on many southern ballots by Democrats. More importantly, Lincoln won a majority in the Electoral College. Southerners refused to accept the results. With South Carolina leading the way, southern states began to secede from the United States in 1860. South Carolinian Mary Boykin Chesnut wrote in her diary about the reaction to the Lincoln’s election. “Now that the black radical Republicans have the power,” she wrote, “I suppose they will Brown us all.” Her statement revealed many southerners’ fear that with Lincoln as President, the South could expect more mayhem like the John Brown raid. Ironically, Lincoln had no plans to restrict slavery in the states where it already existed. But he was committed to preserving the Union.

Media Attributions

- 1820USMap © Melish, Valance, Taylor is licensed under a Public Domain license

- US_SlaveFree1846_Wilmot © Kenmayer is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1848_Electoral_Map © USGS is licensed under a Public Domain license

- John_C_Calhoun_by_Mathew_Brady,_March_1849-original © Mathew Brady is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3a08181r © Edward Williams Clay is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-Henry_Clay_Senate3 (1) © Peter F. Rothermel is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Slave_kidnap_post_1851_boston © Lotsofissues~commonswiki is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 54232v © Harvey B. Lindsley is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 14337806846_9683be0218_b © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1855_Colton_Map_of_Kansas_and_Nebraska_(first_edition)_-_Geographicus_-_NebraskaKansas-colton-1855 (1) © J.B. Colton is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Reynolds’s_Political_Map_of_the_United_States_1856 (1) © Reynolds is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Free-state-hotel © Sara T. D. Robinson is licensed under a Public Domain license

- John_Brown_daguerreotype_c1856 © John Bowles is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Southern_Chivalry © John L. Magee is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Forcing_Slavery_Freesoilers_Throats © John L. Magee is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dred_Scott_photograph_(circa_1857) © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2560px-Roger_B._Taney_-_Brady-Handy © Mathew Brady is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Lincoln_Douglas © Scewing is licensed under a Public Domain license

- John_Brown_portrait,_1859 © Martin M. Lawrence is licensed under a Public Domain license

- John_Brown._Meeting_the_slave-mother_and_her_child_on_the_steps_of_Charlestown_jail_on_his_way_to_execution_LCCN2003674588 © Bernard F. Reilly is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1860_Electoral_Map © USGS is licensed under a Public Domain license