7 Transportation, Land, Industry

On the eve of the American Revolution, the only road that did not hug the east coast followed the Hudson River Valley into western New York on its way to Montreal (this was one reason colonial Americans seemed continually obsessed with the idea of conquering Montreal and bringing it into the United States). Less than thirty years later, riders working for the Post Office Department carried mail to nearly all the new settlements of the interior. The postal system’s designer, Benjamin Franklin, understood that in order for the new Republic to function, information had to flow freely. Franklin set a low rate for mailing newspapers, insuring that news would circulate widely in the newly-settled areas. But it was one thing carrying saddlebags filled with letters and newspapers to the frontier, and something else moving people and freight.

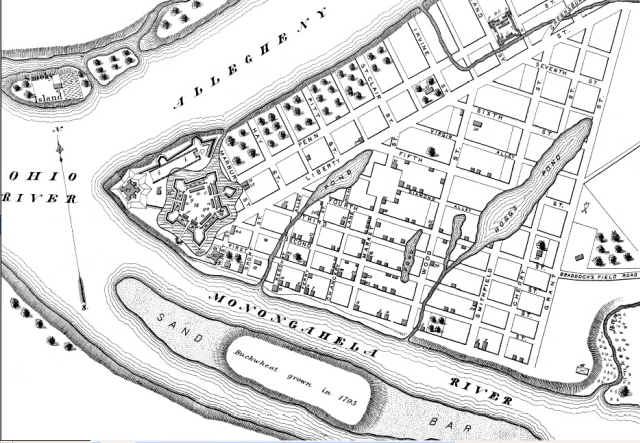

Rivers were the first important routes to the interior of North America. The Ohio River, which begins at Pittsburgh and flows southwest to join the Mississippi, helped people get to their new farms in the Ohio Valley and then helped them carry their farm produce to markets. The Ohio River Valley became one of the first areas of rapid settlement after the Revolution, along with the Mohawk River Valley in western New York. The importance of river shipping is illustrated by the fact that over fifty thousand miles of tributary rivers and streams in the Mississippi watershed were used to float goods to the port of New Orleans. The dependence of western farmers on the Spanish port also explains why New Orleans was a considered strategic city by the United States in the War of 1812. Thomas Jefferson’s 1803 purchase of the Louisiana Territory had actually begun as an attempt to buy the city of New Orleans, and Andrew Jackson’s defense of the port during the War of 1812 helped insure the success of western expansion.

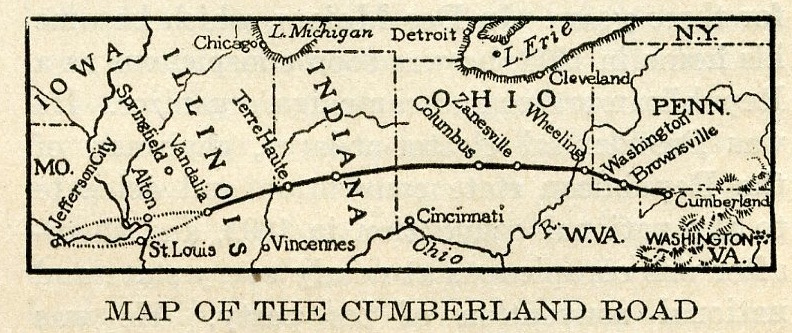

An important early part of the transportation revolution was the widespread building of roads and turnpikes. In 1811, construction began on the Cumberland Road, a national highway that provided thousands of settlers with a route from Maryland to Illinois. The federal government funded this important artery to the West, setting the pattern of government involvement in building transportation infrastructure for the benefit of settlers and farmers. States and even private companies also built turnpikes, which charged fees for use. New York State, for instance, chartered turnpike companies that dramatically increased the miles of state roads from one thousand in 1810 to four thousand by 1820. New York led the way in building turnpikes.

In spite of these new roads, most early westward expansion depended on rivers, and towns and cities built during this era were usually on a waterway. Pittsburgh, Columbus, Cincinnati, Louisville, St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha, and St. Paul all owe their locations to the river systems they provide access to. Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and Milwaukee utilize the Great Lakes in the same way. These lakeside cities exploded after the Erie Canal opened a route from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic, and allowed New York to overtake New Orleans as the nation’s most important commercial port. The 363-mile Erie Canal was so successful that another four thousand miles of canals were dug in America before the Civil War. Canal mania swept the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. Even short waterways, such as the two-and-a-half-mile canal that allowed boats to bypass the rapids of the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky, proved a huge leap forward by opening a water route from Pittsburgh to New Orleans.

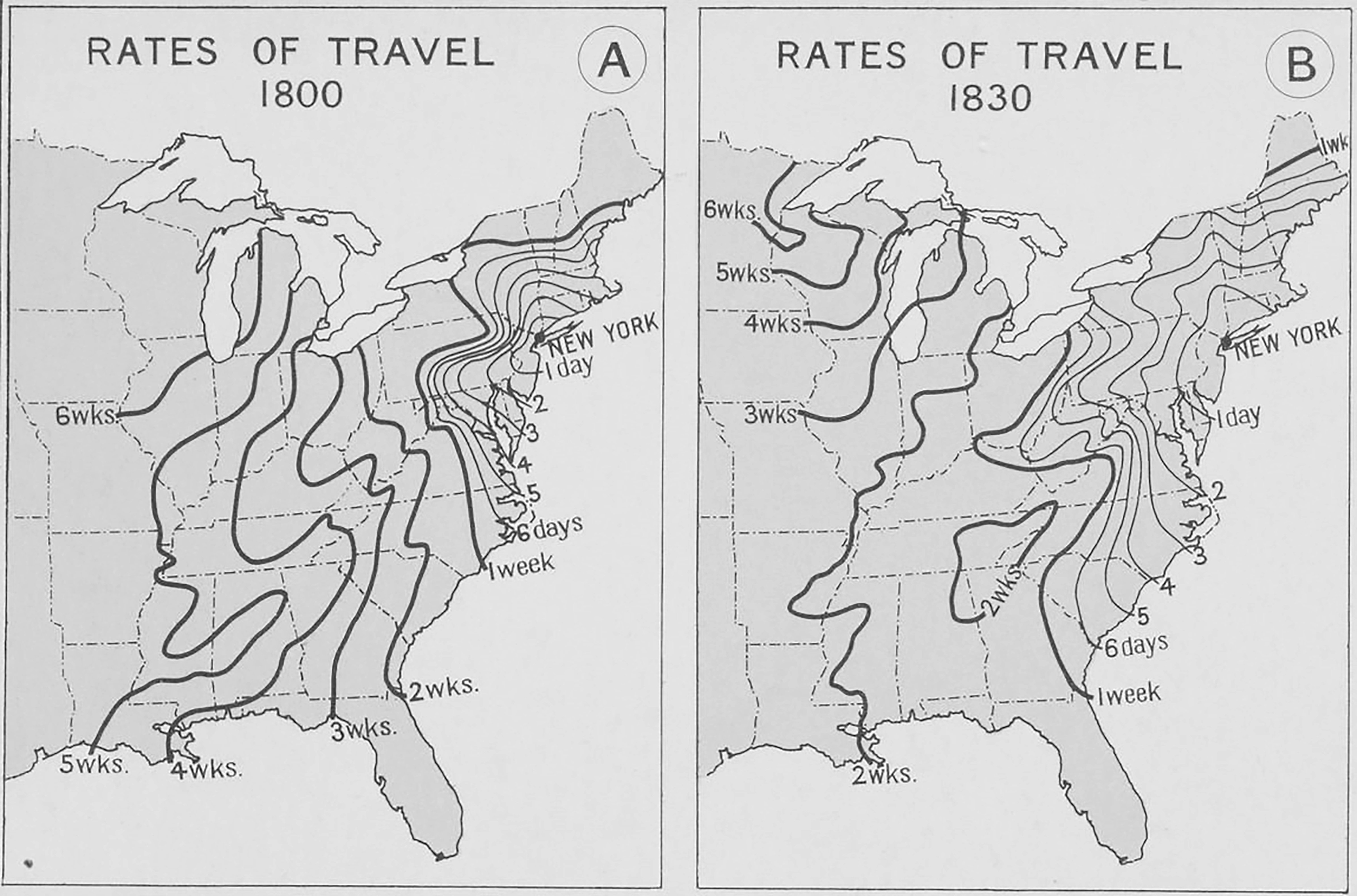

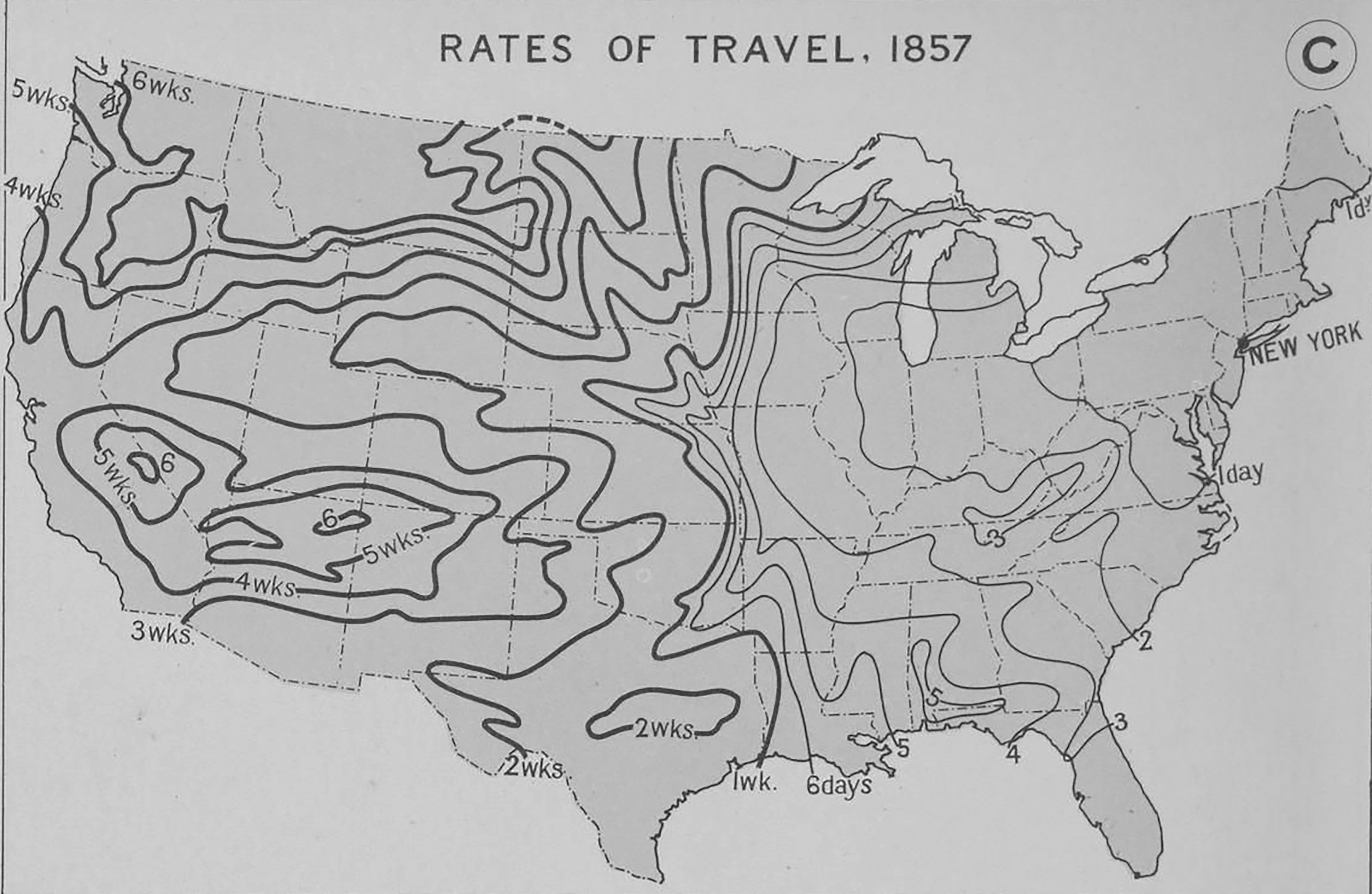

In 1800, it took nearly two weeks to reach Buffalo from New York City, a month to get to Detroit, and six grueling weeks of travel to arrive at the swampy lake-shore settlement that would become Chicago. Thirty years later, Buffalo was just five days away, Detroit about ten days, and Chicago less than three weeks. Horses pulled canal boats from towpaths on shore, eliminating the strain of travel for the boats’ passengers. Floating along on calm water was infinitely more comfortable than spending weeks on a wagon, in a cramped stage coach, or on horseback. The number of people willing to make long trips increased accordingly. And the amount of freight shipped to New York, after the canal cut shipping costs by over ninety percent, increased astronomically. Goods flowed along the Canal in both directions, offering life-changing opportunities. Within ten years of the Erie Canal’s completion, the last fulling mill processing homespun cloth in Western New York shut its doors. Women no longer had to spend their time spinning wool and weaving their own textiles to make their family’s clothing. They could buy bolts of wool and cotton fabrics from the same merchant at the local general store who ground their family’s grain into flour and shipped it on the Canal to eastern cities. With fewer demands on their time, many women were able to not only improve the quality of their own lives, but contribute to family income by taking in piece-work, raising cash crops, or keeping cows and churning butter for sale to their local merchants.

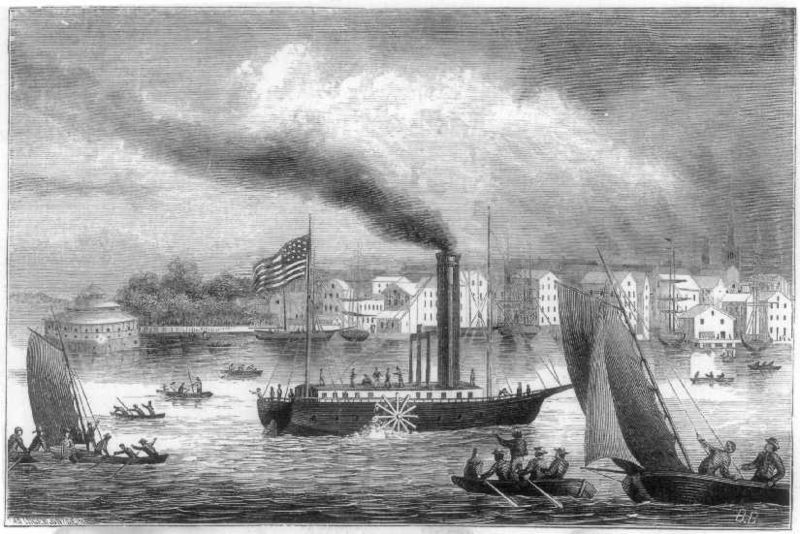

Steam technology changed the nature of transportation. Until steam engines were put on riverboats, shipping had depended on either wind and river currents or on human and animal power. Goods could easily be floated south from farms on the nation’s rivers, but it was much more difficult and expensive to ship products against the rivers’ currents to the frontier. Flatboats and rafts actually accumulated at downstream ports and were broken down and burned as firewood. Steam engines made it possible to travel upstream as easily and nearly as quickly as down, causing an explosion of travel and shipping that radically changed frontier life.

Steam engines were a product of early European industrialism and had originally been designed to drive pumps used to drain mines. Englishman James Watt’s 1781 engine was the first to produce rotary power that could be adapted to drive mills, wheels, and propellers. Robert Fulton, an American inventor who had previously patented a canal-dredging machine, visited Paris and caught steamboat fever. Fulton sailed an experimental model on the Seine, and then returned home and launched the first commercial American steamboat on the Hudson River in 1807. The Clermont was able to sail upriver 150 miles from New York City to Albany in 32 hours. In 1811, Fulton built the New Orleans in Pittsburgh and began steamboat service on the Mississippi.

Although Robert Fulton died just a few years later of tuberculosis, his partners Nicholas Roosevelt and Robert Livingston carried on his business, and the age of riverboats was underway. Like Fulton’s prototype and the Clermont, the New Orleans was a large, heavy side-wheeler with a deep draft. This was not the most efficient design for shallow water and it did not take long for ship-builders to settle on the familiar shallow-draft rear-paddle riverboats that carried freight on the Mississippi and its tributaries well into the 20th century. The shallower a riverboat’s draft, the farther upriver it could travel. Steam-powered riverboats soon pushed the transportation frontier to Fort Pierre in the Dakota territory and even to Fort Benton, Montana. Riverboats made it possible to ship goods in and out of nearly the entire area Thomas Jefferson had acquired in the Louisiana Purchase just a generation earlier. And steam-powered ocean shipping made the markets of Britain and Europe readily accessible to farmers and merchants in the middle of North America.

The other transportation technology enabled by steam power, of course, was the railroad. But railroads were even more revolutionary than steamboats. In spite of their power and speed, steam-powered riverboats depended on rivers or occasionally on canals to run. A railroad could be built almost anywhere. Suddenly, the expansion of American commerce was no longer limited by the routes nature had provided into the frontier.

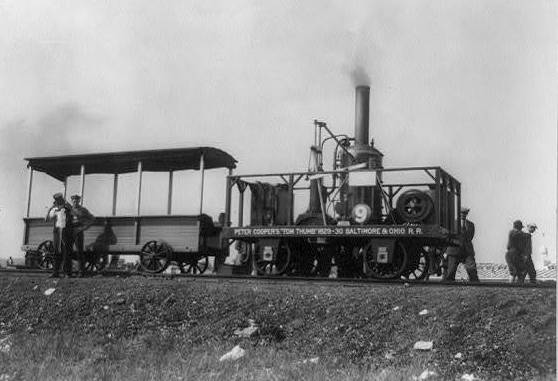

America’s first small railroads had actually been built on the East Coast before a steam engine was available to power them. The cars were pulled by horses and looked a lot like a train of stage-coaches on rails. But after Englishman George Stephenson’s locomotives began pulling passengers and freight in northwestern England in the mid-1820s, Americans quickly switched to steam. The first locomotive used to pull cars in the United States was the Tom Thumb, built in 1830 for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Although Tom Thumb actually lost its maiden race against a horse-drawn train, Baltimore and Ohio owners were convinced by the demonstration of steam technology and committed to developing steam locomotives. The B&O, which had been established in 1827 to compete with the Erie Canal, already advertised itself as a faster way to move people and freight from the interior to the coast. Adding steam engines accelerated rail’s advantage over canal and river shipping. Over 9,000 miles of track were laid by 1850, most of it connecting the northeast with western farmlands. The Mississippi River was still the preferred route to market from Louisville and St. Louis south. But Cincinnati and Columbus became connected by rail to the Great Lake ports at Sandusky and Cleveland, giving the northern Ohio Valley faster access to New York markets. Detroit and Lake Michigan were also connected by rail, making the long steamboat trip around the northern reach of Michigan’s lower peninsula unnecessary.

By 1857, rail travelers could reach Chicago in less than two days and could be almost anywhere in the northern Mississippi Valley in three. On the eve of the Civil War in 1860, Chicago was already becoming the railroad hub of the Midwest. The Illinois Central Company had been chartered in 1851 to build a rail line from the lead mines at Galena to Cairo, where the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers joined. Galena is also located on the Mississippi on the northern border of Illinois, but rapids north of St. Louis made transporting ore on the river impossible, illustrating the advantage of rails over rivers. A railroad line to Cairo, with a branch line to Chicago, would also attract settlers and investors to Illinois. Young Illinois attorney Abraham Lincoln helped the Illinois Central Company lobby legislators and receive the first federal land grant ever given to a railroad company. The company was given 2.6 million acres of land, and Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas helped design the checkerboard distribution of parcels that would become common for railroad land grants. The map below shows the extent of the land the government gave to the Illinois Central Company, which a few years later showed its gratitude by helping to finance Lincoln’s Presidential campaign against Douglas.

By 1840, more than three thousand miles of canals had been dug in the United States, and thirty thousand miles of railroad track were laid by the beginning of the Civil War. Together with the hundreds of steamboats that plied American rivers, these advances in transportation made it easier and less expensive to ship agricultural products from the West to feed people in eastern cities, and to send manufactured goods from the East to people in the West. Rural families also became less isolated as a result of the transportation revolution. People who had made the difficult trip on foot or horseback to settle western New York or southern Michigan were thrilled when “the cars” reached their communities, allowing them to visit relatives they had left behind. Traveling circuses, menageries, peddlers, and itinerant painters could also more easily make their way into rural districts, and people in search of work found cities and mill towns within their reach.

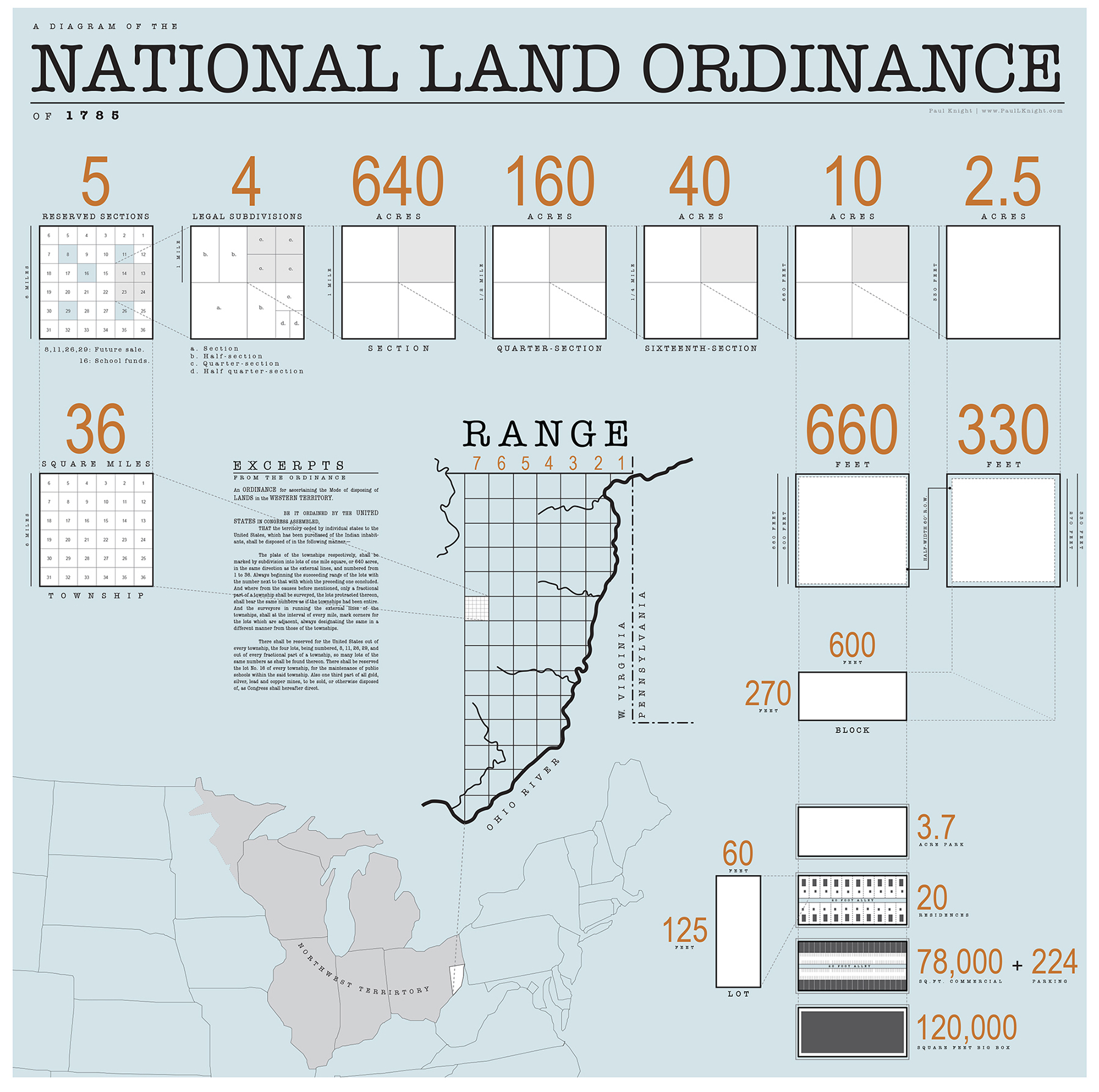

In the early nineteenth century, people poured into the territories west of the long-settled eastern seaboard and the barrier set by the British Proclamation Line. Among them were speculators seeking to buy cheap parcels from the federal government in anticipation of a rise in prices. The Ohio River Valley in the Northwest Territory appeared to offer the best prospects for many in the East, especially New Englanders. When New England farmers grew old, the farm usually passed to the youngest son, who was still at home when his parents became too old to work and who took care of them in exchange for inheritance. Older sons (and daughters who married other farmers’ sons) moved west and began their own farms, and early American families had an average of about six children. The result was “Ohio fever,” as thousands traveled to this fertile land close to a major river. The federal government oversaw the orderly transfer of public land to citizens at public auctions and at land offices in the new territories. The Land Law of 1796 applied to the territory of Ohio after it had been taken from Indians. The Land Law of 1800 further encouraged land sales in the Northwest Territory by reducing the minimum parcel size by half and enabling sales on credit, with the goal of stimulating settlement by ordinary farmers. Buyers were given low interest rates, with payments that could be spread over four years. Surveyors marked off the parcels in straight lines, creating a landscape of checkerboard squares.

Each square-mile section contained 640 acres of land, which could be subdivided into quarter-sections of 160 acres each or half-quarter sections of 80 acres, which most people in the early nineteenth century considered the smallest size for a successful farm. In towns and cities, land could be subdivided down to 60 by 125 foot single family building lots. The price of the land on the frontier would remain low for most of the nineteenth century, falling to $1 per acre and later rising to $1.25 per acre, although after Andrew Jackson’s Specie Circular of 1836, payments at the Land Offices had to be made in cash rather than bank notes or on credit. In the cities, speculation could quickly drive land prices up, causing property bubbles like the one that inflated Chicago real estate values by 40,000 percent in the early 1830s, driving land prices to New York City levels before bursting in a storm of foreclosures in 1841.

The future looked bright for those who turned their gaze on the land in the West. Surveying, settling, and farming, turning land taken from the Indians, which most Americans considered wilderness, into a profitable commodity, gave purchasers a sense of progress. A uniquely American story of the frontier developed became part of the national mythology, in which hardy individuals wielding an axe cleared land, built a log cabin, and turned the “wilderness” into a farm that paved the way for mills and towns.

A NEW ENGLANDER HEADS WEST

A native of Vermont, Gershom Flagg was one of thousands of New Englanders who caught “Ohio fever.” In this letter to his brother Azariah, dated August 3 1817, he describes the hustle and bustle of the emerging commercial town of Cincinnati.

DEAR BROTHER,

Cincinnati is an incorporated City. It contained in 1815, 1,100 buildings of different descriptions among which are above 20 of Stone 250 of brick & 800 of Wood. The population in 1815 was 6,500. There are about 60 Mercantile stores several of which are wholesale. Here are a great share of Mechanics of all kinds.

Here is one Woolen Factory four Cotton factories but not now in operation. A most stupendously large building of Stone is likewise erected immediately on the bank of the River for a steam Mill. It is nine stories high at the Waters edge & is 87 by 62 feet. It drives four pair of Stones besides various other Machinery as Wool carding &c &c. There is also a valuable Steam Saw Mill driving four saws also an inclined Wheel ox Saw Mill with two saws, one Glass Factory. The town is Rapidly increasing in Wealth & population. Here is a Branch of the United States Bank and three other banks & two Printing offices. The country around is rich. . . .

That you may all be prospered in the world is the anxious wish of your affectionate Brother

GERSHOM FLAGG

Many Americans were struck with “land fever.” Farmers strove to expand their acreage, and those who lived in areas where unoccupied land was scarce sought holdings in the West. They needed money to purchase this land, however. Small merchants and factory owners, hoping to take advantage of this boom time, also borrowed money to expand their businesses. When established banks refused to lend to small farmers and others without a credit history, state legislatures chartered new banks to meet the demand. In one legislative session, Kentucky chartered forty-six. As loans increased, paper money from new state banks flooded the country, creating inflation that drove the price of land and goods still higher. Speculators took advantage of this boom by purchasing property not to live on, but to resell at exorbitant prices.

During the War of 1812, the Bank of the United States had suspended payments in specie, “hard money” in the form of gold and silver coins. When the war ended, the bank continued to issue only paper banknotes and to redeem notes issued by state banks with paper only. The newly chartered banks also adopted this practice, issuing banknotes in excess of the amount of specie in their vaults. Printing more notes than a bank could back up with hard cash worked only so long as people were content to conduct business with paper money and refrain from demanding that banks redeem notes for the gold and silver that was supposed to back them. In most cases, people were happy to use paper money because gold and silver were bulky and inconvenient, and because the notes often came with interest attached. Much of the paper circulating as currency was actually promissory notes or agreements to pay a certain sum at a future date (for example, $100 in 60 days), including interest. The problem was that if large numbers of people, or banks that had loaned money to other banks, began to demand specie payments, the banking system would collapse because there was not actually enough specie to support the amount of paper money the banks had put into circulation. Some bankers were so afraid of “runs” in which customers would demand gold and silver that in one case an irate bank employee in Ohio stabbed a customer who had the audacity to ask for specie in exchange for the banknotes he held.

The economic bubble inflated by land fever burst in 1819, resulting in a depression called the Panic of 1819. It was the first prolonged economic depression experienced by the American public, who panicked as they saw the prices of agricultural products fall and businesses fail. Prices had already begun falling in 1815, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, when European demand for American crops began to wane and Britain began to “dump” its surplus manufactured goods, the result of wartime overproduction, in American ports. In 1818, crop prices tumbled by as much 75 percent, leaving farmers unable to pay their debts. As they defaulted on their loans, banks seized their property. However, because the drastic fall in agricultural prices had greatly reduced the value of land, the banks were left with farms they were unable to sell. Land speculators lost the value of their investments. As the countryside suffered, hard-hit farmers ceased to purchase manufactured goods. Factories responded by cutting wages or firing employees.

Also in 1818, the Second Bank of the United States needed specie to pay foreign investors who had loaned money to the United States to enable the country to purchase Louisiana. The bank began to call in the loans it had made and required state banks to pay their debts in gold and silver. Severe consequences followed as banks closed their doors and businesses failed. Three-quarters of the work force in Philadelphia was unemployed, and charities were swamped by thousands of newly destitute people needing assistance. In states with imprisonment for debt, the prison population swelled. As a result, many states drafted laws to provide relief for debtors. Even those at the top of the social ladder were affected by the Panic of 1819. Thomas Jefferson, who had cosigned a loan for a friend, nearly lost Monticello when his acquaintance defaulted and left Jefferson responsible for the debt. In an effort to stimulate the economy, Congress passed the Land Law of 1820, allowing smaller parcels of eighty acres to be sold. The Relief Act of 1821 allowed Ohioans to return land to the government if they could not afford to keep it and extended the credit period to eight years. States passed laws to prevent mortgage foreclosures so buyers could keep their homes. After four years, the depression abated and the American economy began to grow again.

In the late 1790s and early 1800s, Great Britain boasted the most advanced textile mills and machines in the world, and the United States continued to rely on Great Britain for finished goods. Great Britain hoped to maintain its economic advantage; so to prevent the knowledge of advanced manufacturing from leaving the Empire, the British banned the emigration of mechanics, skilled workers who knew how to build and repair the latest textile machines. Some British mechanics, including Samuel Slater, managed to travel to the United States with information on the workings of water-powered textile mills British industrialist Richard Arkwright had pioneered. In the 1790s in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Slater convinced several American merchants, including the wealthy Providence merchant Moses Brown, to finance and build a water-powered cotton mill based on the British models. Slater’s knowledge of both technology and mill organization made him the founder of the first successful cotton mill in the United States.

The success of Slater and his partners inspired others to build additional mills in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. By 1807, thirteen more mills had been established. President Jefferson’s embargo on British manufactured goods from late 1807 to early 1809 (discussed in a previous chapter) spurred more New England merchants to invest in industrial enterprises. By 1812, seventy-eight new textile mills had been built in rural New England towns. Most turned out woolen goods, while the rest produced cotton cloth. Slater’s mills and those built in imitation of his were fairly small, employing only seventy people on average. Under the “Rhode Island system,” families were hired and instead of being paid in cash, the father was given credit equal to the wages on his family’s labor that could be redeemed in the form of rent in company-owned housing or goods from the company-owned store.

The Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812 played a pivotal role in spurring industrial development in the United States. Jefferson’s embargo prevented American merchants from engaging in the Atlantic trade, and war further compounded the financial woes of American merchants. New England merchants Nathan Appleton and Francis Cabot Lowell had toured Britain’s largest water-powered textile mills during a stay in Great Britain in 1810. They memorized the designs of the machines they saw at New Lanark in Scotland, especially the power loom which replaced individual hand weavers. In 1813, Appleton and Lowell formed the Boston Manufacturing Company (BMC). They raised $400,000 and in 1814 established a textile mill in Waltham on the banks of the Charles River.

At Waltham, cotton was carded and drawn into coarse strands of cotton fibers called rovings. The rovings were then spun into yarn, and the yarn woven into cotton cloth. Yarn no longer had to be put out to farm families for further processing. All the work was now performed at a central location—the factory. Work in Lowell’s mills was both mechanized and specialized. The putting out system had begun the process of separating skilled craftwork into repetitive tasks; the factory expanded on this division of labor. And as machines took over labor from humans and people increasingly found themselves confined to the same repetitive step, the process of deskilling began.

The BMC opened additional textile mills on the Merrimack River, each employing hundreds of workers who lived in company towns, where the factories and worker housing were owned by the company. The most famous of these company towns was Lowell Massachusetts, built on land the BMC purchased in 1821 from the village of East Chelmsford, north of Boston. The mill owners planted flowers and trees to maintain the appearance of a rural New England town and to forestall arguments, made by many, that factory work was unnatural and unwholesome. The BMC avoided the Rhode Island system, preferring individual workers to families. These employees were not difficult to find. While young men could work at a variety of occupations, young women had more limited options. The textile mills provided ready employment for the daughters of Yankee farm families.

To reassure anxious parents that their daughters’ virtue would be protected and to maintain discipline, the BMC established strict rules governing the lives of these young workers. The women lived in company-owned boarding houses they paid for out of their wages. They woke early at the sound of a bell and worked a twelve-hour day during which talking was forbidden. They could not swear or drink alcohol, and they were required to attend church on Sunday. Overseers at the mills and boarding-house keepers kept a close eye on the young women’s behavior; workers who misbehaved lost their jobs and were evicted.

MICHEL CHEVALIER ON MILL WORKER RULES AND WAGES

In the 1830s, the French government sent engineer and economist Michel Chevalier to study industrial and financial affairs in Mexico and the United States. In 1839, he published Society, Manners, and Politics in the United States, in which he recorded his impressions of the Lowell textile mills. In the excerpt below, Chevalier describes the rules and wages of the Lawrence Company in 1833.

All persons employed by the Company must devote themselves assiduously to their duty during working-hours. They must be capable of doing the work which they undertake, or use all their efforts to this effect. They must on all occasions, both in their words and in their actions, show that they are penetrated by a laudable love of temperance and virtue, and animated by a sense of their moral and social obligations. The Agent of the Company shall endeavour to set to all a good example in this respect. Every individual who shall be notoriously dissolute, idle, dishonest, or intemperate, who shall be in the practice of absenting himself from divine service, or shall violate the Sabbath, or shall be addicted to gaming, shall be dismissed from the service of the Company. . . . All ardent spirits are banished from the Company’s grounds, except when prescribed by a physician. All games of hazard and cards are prohibited within their limits and in the boarding-houses.

Weekly wages were as follows:

For picking and carding, $2.78 to $3.10

For spinning, $3.00

For weaving, $3.10 to $3.12

For warping and sizing, $3.45 to $4.00

For measuring and folding, $3.12

Mechanizing the production of formerly handcrafted products and moving production from the home to the factory dramatically increased output of goods. For example, in one nine-month period, Rhode Island women who spun yarn into cloth on hand looms in their homes produced a total of thirty-four thousand yards of fabrics of different types. In 1855, the women working in just one of Lowell’s mechanized mills produced more than forty-three thousand yards. The BMC’s cotton mills quickly gained a competitive edge over the smaller mills established by Samuel Slater and those who had followed his lead. In Massachusetts, the BMC built new mill towns in Chicopee, Lawrence, and Holyoke. In New Hampshire, they built in Manchester, Dover, and Nashua. And in Maine, they built a large mill on the Saco River. Other entrepreneurs copied them. By the time of the Civil War, 878 textile factories operated in New England. All together, these factories employed more than 100,000 people and produced more than 940 million yards of cloth.

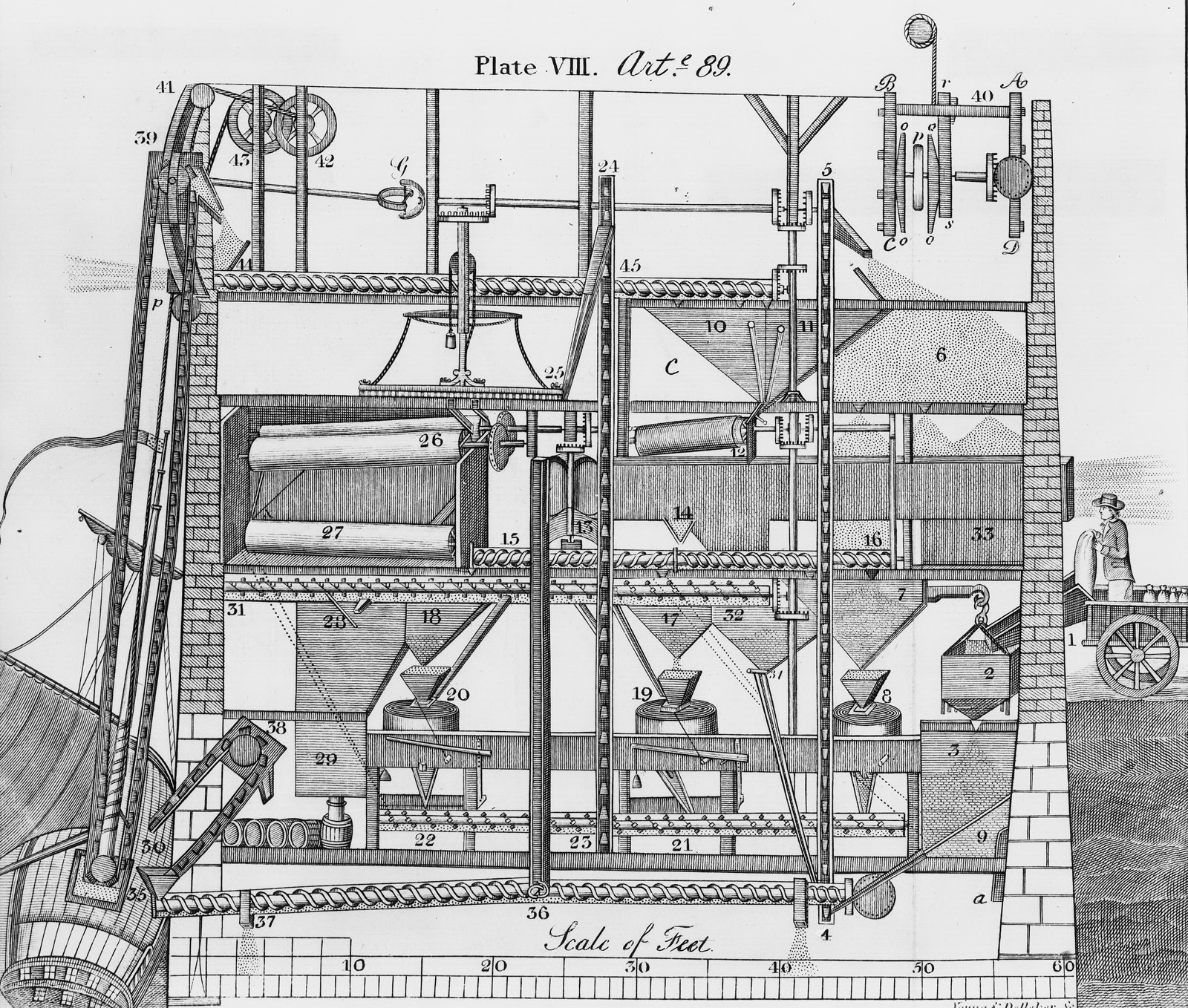

In addition to textiles, which formed the backbone of the Industrial Revolution in the United States as in Britain, other crafts increasingly became mechanized and centralized in factories in the first half of the nineteenth century. Products like shoes, leather, paper, hats, clocks, and guns that had been produced by craftsmen or by putting out were all produced in mechanized factories by the time of the Civil War. Flour milling became almost completely automated and centralized by the early decades of the nineteenth century using technology developed by Oliver Evans. Evans’s mills were so efficient that two employees could do work that had required five, and mills using Evans’s system spread throughout the mid-Atlantic states.

At the end of the eighteenth century, most American families had lived in candlelit homes with bare floors and unadorned walls. They cooked and warmed themselves over fireplaces and owned only a few changes of clothing. Most were farmers who produced most of their needs at home. They occasionally bought manufactured goods made by hand that were usually scarce and fairly expensive. The automation of the manufacturing process changed that, making consumer goods that had once been thought of as luxury items widely available for the first time. Now all but the very poor could afford the necessities and some of the small luxuries of life. When women could buy New England textiles, they no longer had to spend their time spinning and weaving. Rooms were lit by oil lamps, which gave brighter light than candles. Homes were heated by parlor stoves, which allowed for more privacy; people no longer needed to huddle together around the hearth. Iron cookstoves with multiple burners made it possible for housewives to prepare more elaborate meals. Many people could afford carpets and upholstered furniture, and even farmers could decorate their homes with curtains and wallpaper. Clocks, which had once been quite expensive, were now within the reach of most ordinary people. And as more people worked in factories and lived in cities, they no longer grew their own food or made the things they consumed. A new population of consumers grew along with the new products available for them to consume.

As production became mechanized and relocated to factories, life changed for workers. Farmers and artisans had controlled the pace and the order of their labor. If an artisan wanted to take the afternoon off, he could. If a farmer wished to rebuild his fence on Thursday instead of on Wednesday, he could. They conversed and often drank during the workday. Indeed, journeymen were often promised alcohol as part of their wages. Work in factories proved to be quite different. Employees were expected to report early in the morning and to work all day. They could not leave when they were tired or take breaks. Those who arrived late found their pay docked and repeated tardiness could result in dismissal. The monotony of repetitive tasks made days particularly long and most factory employees toiled ten to twelve hours a day, six days a week. In the winter, when the sun set early, oil lamps were used to light the factory floor, and employees strained their eyes to see their work and coughed as the rooms filled with smoke from the lamps.

Freedom within factories was limited. Drinking was prohibited. Some factories did not allow employees to sit down. Mills were often unbearably hot and humid in the summer and frigid in the winter, which led to health problems. And mills were dangerous. Workplace injuries were common. Workers’ hands and fingers were maimed or severed when they were caught in machines; in some cases, their limbs or entire bodies were crushed. Workers who didn’t die from such injuries but could no longer work lost their jobs. Corporal punishment of both children and adults was common in factories; where abuse was most extreme, children sometimes died as a result of injuries suffered at the hands of an overseer. As the decades passed, working conditions deteriorated in many mills. Workers were assigned more machines to tend and the owners increased the speed at which the machines operated. Wages were cut in many factories and employees who had once labored for an hourly wage were reduced to piecework, paid for the amount they produced and not for the hours they toiled. Low wages combined with regular periods of unemployment to make the lives of workers difficult, especially for those with families to support. In New York City in 1850, for example, the average male wage-worker earned $300 a year; while it cost approximately $600 a year to support a family of five. Women earned even less, even when they did the same jobs as men.

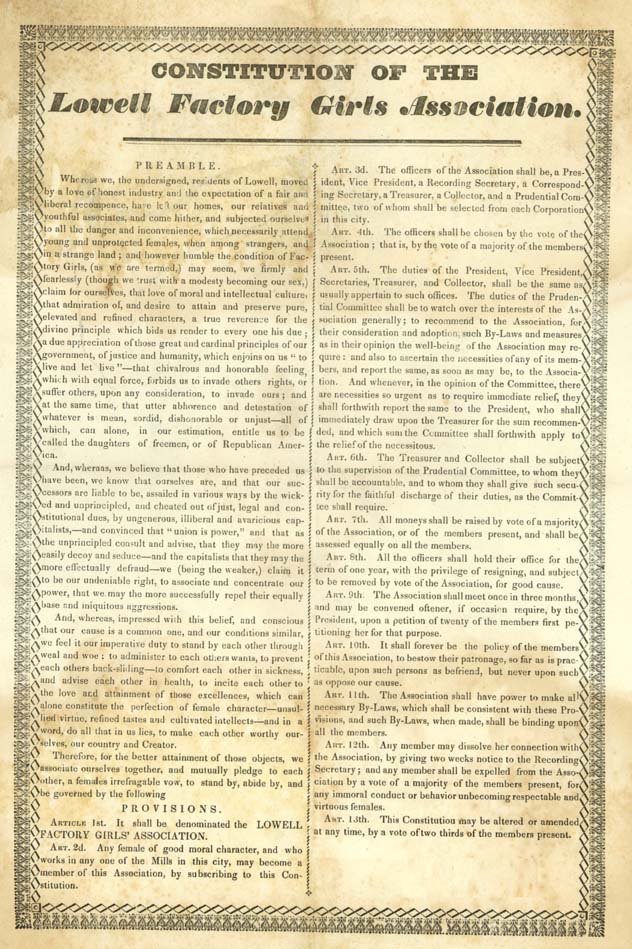

Many workers benefited from the new wage opportunities factory work presented. For many of the young New England women who ran the machines in Waltham, Lowell, and elsewhere, the experience of being away from the family was exhilarating and provided a sense of solidarity among them. Though most sent a large portion of their wages home, having even a small amount of money of their own was a liberating experience, and many used their earnings to purchase clothes and other consumer goods for themselves. The long hours, strict discipline, and low wages, however, soon led even these workers to organize and protest their working conditions and pay. In 1821, the young women employed by the BMC in Waltham went on strike for two days when their wages were cut. In 1824, workers in Pawtucket struck to protest reduced pay rates, longer hours, and the reduction of time allowed for meals. Similar strikes occurred at Lowell and in other mill towns like Dover New Hampshire, where the women employed by the Cocheco Manufacturing Company ceased working in December 1828 after their wages were reduced. In the 1830s, female mill operatives in Lowell formed the Lowell Factory Girls Association to organize strike activities in the face of wage cuts and, later, established the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association to protest the twelve-hour workday. Even though strikes were rarely successful and workers usually were forced to accept reduced wages and increased hours, work stoppages as a form of labor protest represented the beginnings of the labor movement in the United States.

In cities such as Philadelphia, New York, and Boston that experienced dizzying industrial growth during the nineteenth century, workers united to form political parties. Thomas Skidmore of Connecticut organized the Working Men’s Party which lodged a radical protest against the exploitation of workers that accompanied industrialization. Skidmore was inspired by Thomas Paine and the American Revolution to challenge the growing inequity in the United States. He argued that inequality originated in the unequal distribution of property through inheritance laws. In his 1829 treatise, The Rights of Man to Property, Skidmore called for the abolition of inheritance and the redistribution of property. The Working Men’s Party also advocated the end of imprisonment for debt. Skidmore’s vision of radical equality extended to all; women and men, no matter their race, should be allowed to vote and receive property, he believed. Skidmore died in 1832 when a cholera epidemic swept New York City, but the state of New York did away with imprisonment for debt in the same year.

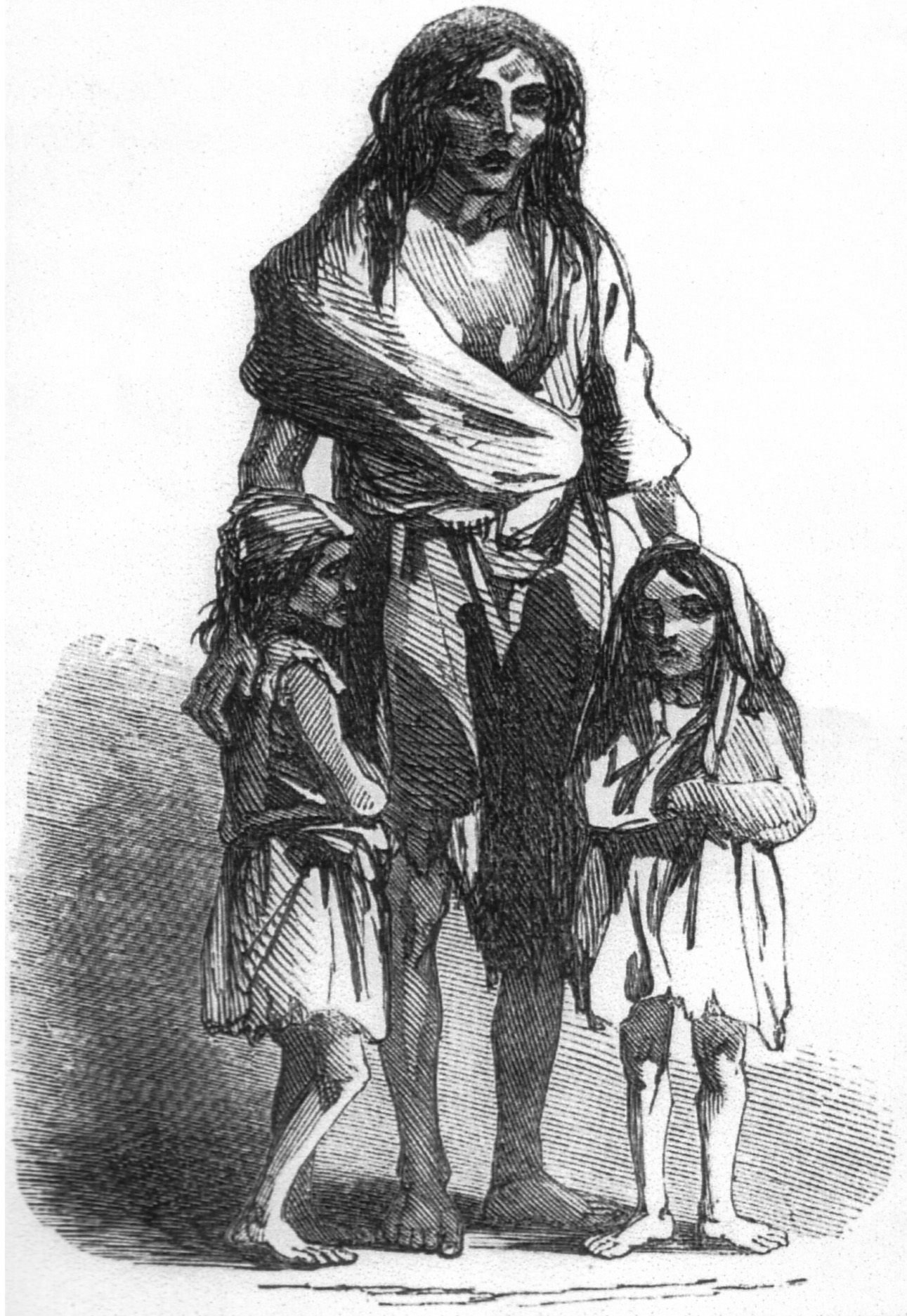

Worker activism became less common in the late 1840s and 1850s. Irish and German immigrants poured into the United States in the decades preceding the Civil War and native-born laborers found themselves competing for jobs with new arrivals willing to work longer hours for less pay. In Lowell, for example, the daughters of New England farmers found themselves competing with the daughters of Irish farmers who had fled the potato famine. Desperate immigrant women were willing to work for far less and endure worse conditions than native-born women. Many native-born “daughters of freemen,” as they referred to themselves, left the factories and returned to their families. Not all wage workers had this luxury, however. Widows with children to support and girls from destitute families had no choice but to stay and accept the faster pace and lower pay that competition for their jobs allowed factories to impose. Male German and Irish immigrants competed with native-born men. Germans, many of whom were skilled workers, took jobs in furniture making. The Irish provided the unskilled labor needed to load and unload ships, lay railroad track, and dig canals. American men with families to support grudgingly accepted low wages in order to keep their jobs. As work became increasingly deskilled, no worker was irreplaceable and no one’s job was safe.

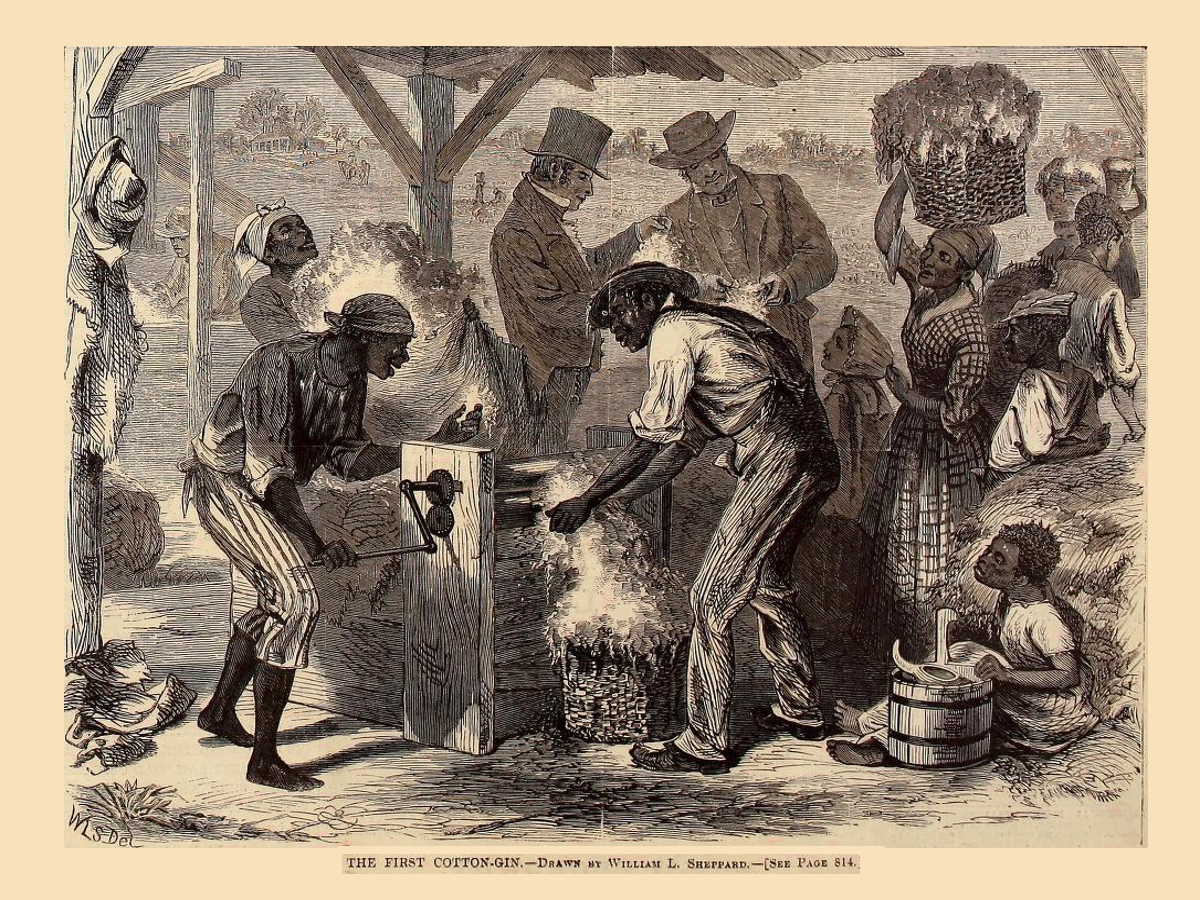

One of the most important inventions of the early nineteenth century was the cotton engine or gin, invented by Eli Whitney and patented in 1794. Whitney, who was born in Massachusetts, had spent time in the South and knew that a device to speed up the production of cotton was desperately needed so cotton planters could meet the growing demand for their crop. Whitney’s seemingly simple invention cleaned the seeds from raw cotton far more quickly than slaves working by hand. The cotton gin also aligned the cotton fibers in strands for spinning. As important as Whitney’s invention was, his development of the idea of interchangeable parts was even more innovative. Whitney designed machine tools that cut and shaped metal to make standardized parts for mechanical devices like clocks and guns. Whitney’s machine tools allowed guns to be mass manufactured and repaired by people other than skilled gunsmiths. His creative genius served as a source of inspiration for many other American inventors.

While Whitney’s cotton gin enriched the South, a southern-born businessman helped revolutionize life on northern farms. Cyrus McCormick’s father Robert had spent twenty years perfecting the mechanical reaper McCormick patented in 1834, with the help of Jo Anderson, a slave the family held on their Virginia plantation. Cyrus added manufacturing and marketing innovations to the successful reaper design, and moved his McCormick Harvesting Machine Company to Chicago to be closer to his customers. More farmers began using it in the 1840s, and by the 1850s, McCormick’s mechanical reaper and John Deere’s plow had opened the prairies to large-scale commercial agriculture. McCormick’s machines harvested grain faster than men with scythes and Deere’s plow could cut through the thick prairie sod. Agriculture north of the Ohio River became the breadbasket that would lower food prices and feed the major cities in the East. In short order, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois all become major agricultural states.

Samuel F.B. Morse added the telegraph to the list of American innovations introduced in the years before the Civil War. Born in Massachusetts in 1791, Morse first gained renown as a painter before turning his attention to the development of a method of rapid communication in the 1830s. In 1838, he gave the first public demonstration of his method of conveying electric pulses over a wire, using the basis of what became known as Morse code. In 1843, Congress agreed to help fund the new technology by allocating $30,000 for a telegraph line to connect Washington, DC, and Baltimore along the route of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Because railroads were already being granted “rights of way” through the countryside and cities, telegraph lines could easily be added along the tracks and telegraph offices became associated with railway stations. In 1844, Morse sent the first telegraph message on the new link. Improved communication systems fostered the development of business, economics, and politics by allowing for dissemination of news at a speed previously unknown. “Wire services” distributed news and merchants used the rapid communication allowed by the telegraph to establish standardized national pricing for commodities and products.

Economic elites gained further social and political ascendance in the United States due to a fast-growing economy that enhanced their wealth and new business innovations like the corporation that allowed capital to be concentrated and a new class of capitalists to grow. In northern cities such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, leading merchants formed an industrial capitalist elite and the gap widened between wealthy Americans and everyone else. Many of the new capitalists came from families that had been deeply engaged in colonial trade in tea, sugar, pepper, slaves, and other commodities and that were familiar with trade networks connecting the United States with Europe, the West Indies, and the Far East. These colonial merchants had passed their wealth to their children, who began to specialize in new types of industry, spearheading the development of factories and commercial services such as banking, insurance, and shipping. Junius Spencer Morgan, for example, rose to prominence as an international banker. Morgan’s success began in Boston, where he worked in the import business in the 1830s. He formed a partnership with a London banker, George Peabody, and created Peabody, Morgan & Co. In 1864, he renamed the enterprise J. S. Morgan & Co. His son, J. P. Morgan, became the leading financier in the later nineteenth and early twentieth century.

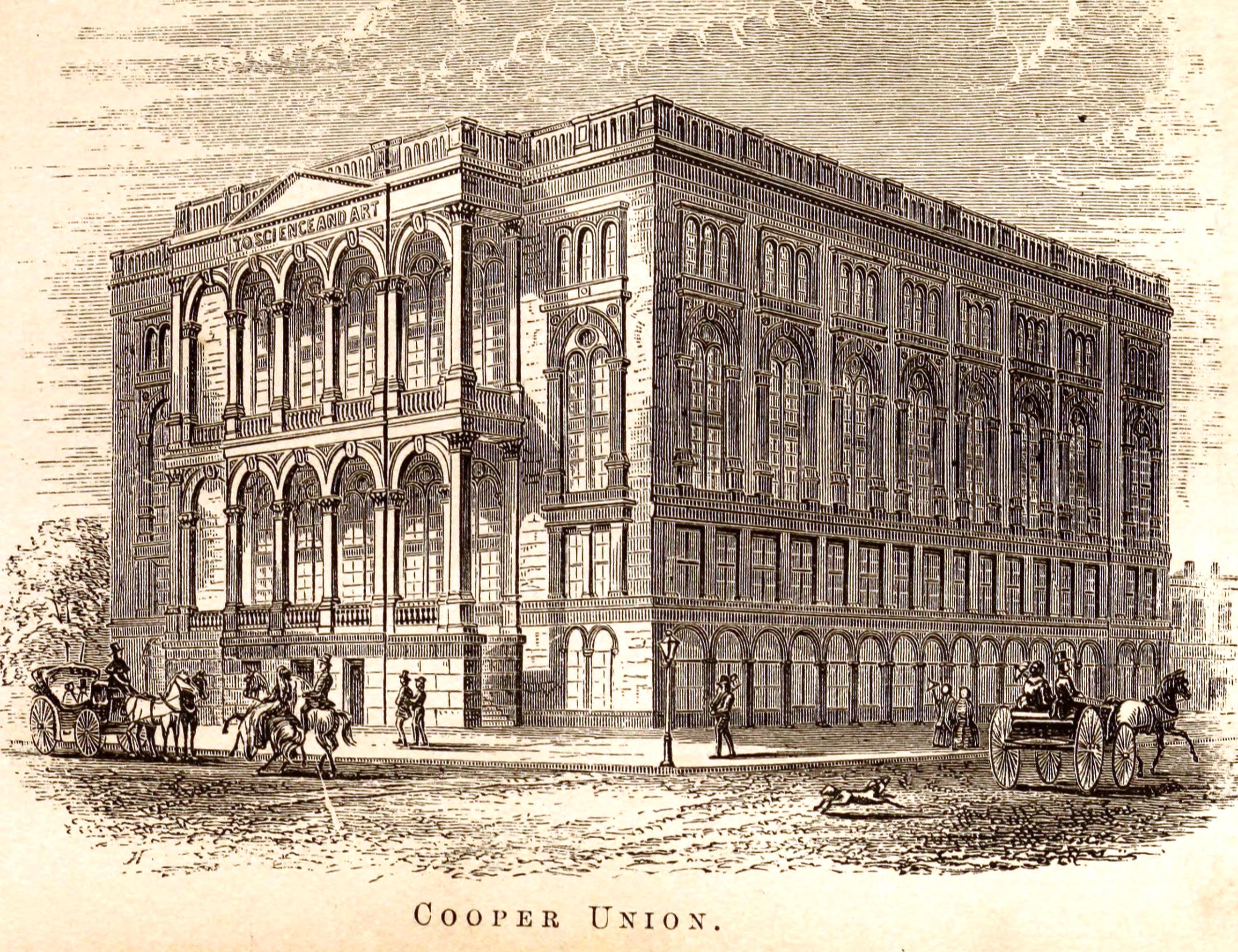

Although the Industrial Revolution made many of the existing upper class far richer, technological change also allowed some former artisans to reinvent themselves as manufacturers. Invention and innovation was not limited to men who had inherited wealth, and some of the new industrial leaders came from humble working-class origins. These self-made men embodied a new “American dream” of achieving wealth and social mobility through hard work and discipline. Although this sentiment had always been present and had been celebrated by writers like Ben Franklin, the nineteenth century was a golden age of rags-to-riches stories. Many of these newly established manufacturers formed a new economic elite that thrived in the cities and created a culture that celebrated hard work, an ideal that put them at odds with southern planter elites who prized leisure and with other elite northerners who had largely inherited their wealth and status. Peter Cooper is an example of this new northern manufacturing class. Cooper dabbled in many different moneymaking enterprises before making his fortune in the glue business. He opened a Manhattan glue factory in the 1820s and was soon using his profits to expand into activities including iron production. One of his innovations was Tom Thumb, the steam locomotive he built for the B&O railway. Despite becoming one of the wealthiest men in New York City, Cooper lived simply. Cooper believed respectability came through hard work, not family pedigree.

Those who had inherited their wealth derided self-made men like Cooper; he and others like him were excluded from social clubs established by the merchant and financial elite of New York City. Self-made northern manufacturers, however, created their own organizations that aimed to promote upward mobility. The Providence Association of Mechanics and Manufacturers was formed in 1789 and promoted both industrial arts and education as a pathway to economic success. In 1859, Peter Cooper established the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a school in New York City dedicated to providing education in technology. Merit, not wealth, mattered to Cooper, and admission to the school was based solely on ability. Race, sex, and family connections had no place, and every student received a full scholarship. The best and brightest could attend Cooper Union tuition-free, a policy that remained in place for over 150 years until it was modified due to financial difficulties in 2014.

In addition to adding new members to the elite class, the Industrial Revolution created the American Middle Class and the Working Class. Not all enterprising artisans were so successful that they could rise to the level of the elite. But many artisans and small merchants did manage to achieve and maintain respectability in an emerging middle class. Others became managers and office workers in the new businesses or in fields such as law, accounting, and finance that supported them. Lacking the protection of great wealth, members of the middle class worried that they might slip into the ranks of wage laborers and strove to maintain or improve their middle-class status and that of their children. Public education, which had always been valued in early America, became even more vital to success. In addition to education, the middle class valued cleanliness, discipline, morality, hard work, and good manners. Middle-class children did not work in factories; they attended school and in their free time engaged in “self-improving” activities that would teach them the skills and values they needed to succeed in life. In the early nineteenth century, members of the middle class began to limit the number of children they had. Fewer children died at a young age, children no longer contributed economically to the household, and raising them “correctly” required money and attention. Raising the next generation was the responsibility of middle-class women, who did not work for wages. Women’s work was caring for the children and keeping the house orderly and clean, often with the help of a servant. Middle-class women also performed the important tasks of cultivating good manners among their children and their husbands and of purchasing consumer goods; both activities proclaimed to neighbors and prospective business partners that their families were educated, cultured, and financially successful.

Middle class northerners were also more likely than their upper-class neighbors to support the abolitionist movement. Northern business elites, many of whom owned or had invested in businesses like cotton mills that profited from slave labor, often viewed the institution of slavery with ambivalence. Members of the middle class took a dim view of slavery, however, because it promoted a culture of leisure and was the antithesis of the middle-class view that dignity and respectability were achieved through work. Many members of the middle class became active in efforts to end it. Upwardly mobile middle -class citizens also promoted sanitary reforms in cities and temperance, or abstinence from alcohol. They supported Protestant ministers like Charles Grandison Finney, who preached that people could change their lives and bring about their own salvation, a message that resonated with members of class who already believed their worldly efforts had led to their economic success.

The Industrial Revolution in the United States also created a new class of wage workers, and this working class also developed its own culture. Although workers like Lowell’s mill girls first lived in company housing, workers soon formed their own neighborhoods, living away from the oversight of bosses and managers. As large numbers of immigrants from Ireland and then Germany arrived, many settled in northern and later northwestern cities like Boston, New York, Detroit, and Milwaukee. Immigrants generally did not settle in the South, because a slave-based economy provided them with few opportunities. While industrialization and consumer markets brought some improvements to the lives of the working class, these sweeping changes did not benefit laborers as much as they did the middle class and the elites. The working class continued to live a precarious existence and suffered greatly during economic slumps such as the Panics of 1819, 1837, and 1857.

Wage workers in the North were mostly hostile to the abolition of slavery, fearing it would unleash more competition for jobs from free blacks. Many were also hostile to immigration. The pace of immigration to the United States accelerated in the 1840s and 1850s as Europeans were drawn to the promise of employment and land in the United States. Many new members of the working class came from the ranks of these immigrants, who brought new foods, customs, and religions. The Roman Catholic population of the United States, fairly small before this period, began to swell with the arrival of the Irish and the Germans.

Media Attributions

- Pittsburgh_1795_large © Samuel W. Durant is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 6151399020_0d824c4cf9_b (1) © Eric Fischer is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- traveltime1 © US Census is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pittsford_on_the_Erie_Canal © George Harvey is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 800px-Clermont_illustration_-_Robert_Fulton_-_Project_Gutenberg_eText_15161 © G. F. and E. B. Bensell is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Riverboats_at_Memphis © Zeamays is licensed under a Public Domain license

- peter-coopers-tom-thumb-640 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- traveltime2 © US Census is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1805_Cary_Map_of_the_Great_Lakes_and_Western_Territory_(Kentucy,_Virginia,_Ohio,_etc..)_-_Geographicus_-_WesternTerritory-cary-1805 © John Cary is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1785 Ordinance Diagram 3 © Isomorphism3000 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Home_in_the_Woods_1847_Thomas_Cole © Thomas Cole is licensed under a Public Domain license

- A_View_of_Cincinnati_on_the_Ohio © Jervis Cutler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- firstbankexterior960 © NPS is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Second_Bank_of_the_United_States_front © Beyond My Ken is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Wilkinson_Mill_of_Slater_Mill_complex_-_exterior_&_water_power_systems © Bestbudbrian is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA © Mrpbps

- acf8e511d20d2f1f6009c2c974c1b394 (1) © E.A. Farrar is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Oliver_Evans_-_Automated_mill © James Poupard

- D11023.jpg © Winslow Homer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2_Young_Women © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- FGA_Constitution © Factory Girls Association is licensed under a Public Domain license

- William_L._Sheppard_-_First_use_of_the_Cotton_Gin,_Harper’s_weekly,_18_Dec._1869,_p._813 © William L. Sheppard is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Samuel_Morse_with_his_Recorder_by_Brady,_1857 © Mathew Brady is licensed under a Public Domain license

- J.P._Morgan_cph.3a02120 © Pach Brothers is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cooper_Union_from_Miller’s_New_York_as_it_is_(14596084839) © Seymour B. durst is licensed under a Public Domain license

- New_York_from_Union_Square_1850 © C. Bachmann is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Irish_potato_famine_Bridget_O’Donnel (1) © Illustrated London News is licensed under a Public Domain license