1 Setting the Scene

THE AMERICAS

During the last ice age, between about 36,000 and about 12,000 years ago, a land historians now call Beringia existed between Asia and North America. Sea levels were about 360 feet lower than they are at present, so a landmass as wide as Alaska was exposed that connected what is now eastern Siberia with what is now western North America, for probably well over ten thousand years (or twice as long as all of recorded history). The first inhabitants of the two continents that would be much later named the Americas lived in Beringia for thousands of years during the ice age, and then migrated into the Americas following the animals they hunted when glaciers began to retreat and rising sea levels cut them off from Asia. This was a gradual change, beginning over fifteen thousand years ago and probably happening in several waves, the last of which was about eleven thousand years ago. Although some scholars have suggested that migrations from Africa or from the Pacific may also have taken place, the fact that Asians and American Indians share genetic markers on a Y chromosome supports the theory that the ancestors of native Americans entered the Americas through Beringia.

Continually moving southward, the settlers eventually populated both North and South America, creating unique cultures that ranged from the highly complex and urban Aztec civilization in what is now Mexico City to the woodland tribes of eastern North America. Recent research along the west coast of South America suggests that migrant populations may have traveled down this coast by water as well as by land. Travelers reached what is now southern Chile over 14,800 years ago, for example, long before there was an ice-free overland route, suggesting that at least some of the new native Americans already knew how to make canoes or kayaks.

Researchers have also discovered that beginning about ten thousand years ago, humans all over the world began domesticating plants and animals, adding agriculture and pastoralism as a means of sustenance to the hunting and gathering techniques humans have used since our species’ origin in Africa. With this agricultural revolution and the more abundant and reliable food supplies it brought, populations grew and people were able to develop a more settled way of life, building permanent settlements and more complex social structures. Nowhere in the Americas was this more obvious than in Central America.

Questions for Discussion

- Why is it significant that Beringia was not a “land bridge”?

- There has been a lot of controversy over the years about the exact timing and the details of human expansion into the Americas. Why might that be?

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is the geographic area stretching from north of Panama up to the desert of central Mexico. Although marked by great topographic, linguistic, and cultural diversity, this region was the home of a number of civilizations with similar characteristics. Mesoamericans were polytheistic; their gods possessed both male and female traits and many demanded blood sacrifices of enemies taken in battle or even sometimes from the people themselves through ritual bloodletting. Corn, or maize, domesticated between 9,000 and 7,000 years ago, formed the staple foundation of a varied diet. Early Mesoamerican cultures developed a mathematical system, built aqueducts, temples, palaces, and pyramids, and devised a calendar that accurately predicted eclipses and solstices and that priest-astronomers used to direct the planting and harvesting of crops.

Most important for our knowledge of these peoples, Mesoamericans created the only known written language in the Western Hemisphere. Though Mesoamerica had no overarching, imperial political structure, trade over long distances helped spread a widely-shared culture. Weapons made of obsidian, jewelry crafted from jade, feathers woven into clothing and ornaments, and cacao beans that were whipped into a chocolate drink formed the basis of commerce. The first major Mesoamerican culture was the Olmec civilization.

Flourishing along the Gulf Coast of Mexico from about 1200 to about 400 BCE, the Olmec produced sophisticated works of art, architecture, pottery, and sculpture. They built aqueducts to transport water into their cities and irrigate their fields. They grew maize, squash, beans, and tomatoes, and bred small domesticated dogs which, along with fish, provided their protein. Although no one knows exactly what happened to the Olmec after about 400 BCE, their culture was the base upon which both the Maya and the Aztec built. The Olmec also developed a system of trade throughout Mesoamerica, giving rise to a wealthy merchant class.

One of the largest population centers in pre-Columbian America and home to more than 100,000 people at its height in about 500 CE, the city of Teotihuacan, was located about thirty miles northeast of modern Mexico City. The ethnicity of this settlement’s inhabitants is debated; some scholars believe it was a multiethnic city. Large-scale agriculture produced abundant food that created opportunities for people to develop special trades and skills other than farming. Teotihuacan’s builders constructed over twenty-two hundred-apartment compounds for multiple families, as well as more than a hundred temples. Among these were the Pyramid of the Sun (which is two hundred feet high) and the Pyramid of the Moon (one hundred and fifty feet high). Near the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, graves have been uncovered that suggest humans were sacrificed for religious purposes. The city was also the center for trade, which extended to settlements on the Gulf Coast.

The Maya were one Mesoamerican culture that had strong ties to Teotihuacan. Mayan architectural and mathematical contributions were significant. Flourishing from roughly 2000 BCE to 900 CE in what is now Mexico, Belize, Honduras, and Guatemala, the Maya perfected the calendar and written language the Olmec may have begun. They devised a written mathematical system to record crop yields and the size of the population, and to assist in trade. Taking advantage of their success in agriculture, the Maya built the city-states of Copan, Tikal, and Chichen Itza along major trade routes. These cities contained temples, statues of gods, pyramids, and astronomical observatories. However, possibly due to a drought that lasted nearly two centuries, their civilization declined by about 900 CE and the Maya abandoned their large population centers.

The Spanish encountered little organized resistance from the weakened Maya upon their arrival in the 1520s. However, they did find extensive Mayan history in the form of glyphs, or pictures representing words, recorded in folding books called codices (the singular is codex). In 1562, Bishop Diego de Landa, who feared recently (and forcefully) converted natives might revert to their traditional religious practices, collected and burned every codex he could find. Today only a few survive.

Questions for Discussion

- Many accounts of the Maya focus on their disappearance. How does this misrepresent their history?

- What potential downsides might a system of extensive trade in Mesoamerica suggest?

Tenochtitlán

When the Spaniard Hernán Cortés arrived on the coast of Mexico in 1519 at the site of present-day Veracruz, he quickly heard of a great city ruled by an emperor named Moctezuma. Cortés was told that this city was tremendously wealthy—reportedly filled with gold—and received tribute from all the surrounding tribes. The riches and complexity Cortés found when he arrived at that city, known as Tenochtitlán, were far beyond anything he or his men had ever seen. Several wrote descriptions of the public places of the island city, Tenochtitlán, admiring both its spotless cleanliness and the size of its markets, said to be bigger than those of any European capital. The city’s population when the Spanish first arrived was over 200,000; larger than Madrid, Rome, or London.

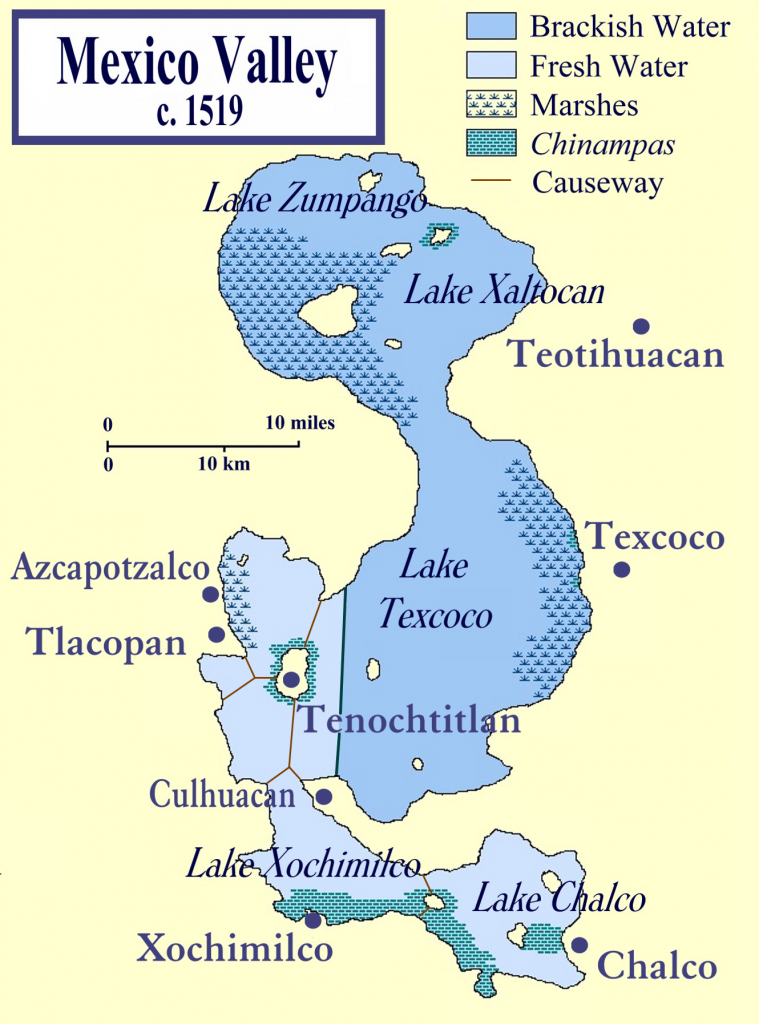

According to legend, generations before the Spanish arrived, a warlike people called the Aztec (also known as the Mexica) had left a city called Aztlán and traveled south to the site of present-day Mexico City. In 1325, they began construction of Tenochtitlán on an island in Lake Texcoco. By 1519, when Cortés arrived, the capital was connected to the mainland by several causeways. One of Cortés’s soldiers, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, recorded his impressions upon first seeing it: “When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land we were amazed and said it was like the enchantments . . . on account of the great towers and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream? . . . I do not know how to describe it, seeing things as we did that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about.”

Unlike the dirty, disease-ridden cities of Europe at the time, Tenochtitlán was well planned, clean, and orderly. The city had neighborhoods for specific occupations, a trash collection system, markets, two aqueducts that supplied fresh water, and public buildings and temples. Unlike the Spanish, Aztecs bathed daily, and wealthy homes might even contain a steam bath. A labor force of slaves from subjugated neighboring tribes had built the fabulous city and the three causeways that connected it to the mainland. To feed its population, Tenochtitlán invented chinampas: floating gardens built on barges made of reeds and filled with fertile soil. Lake water constantly irrigated these chinampas, which were six times as productive, per acre, as the best agriculture in Europe or Asia. Chinampas are still in use and can be seen today in the Xochimilco district of Mexico City.

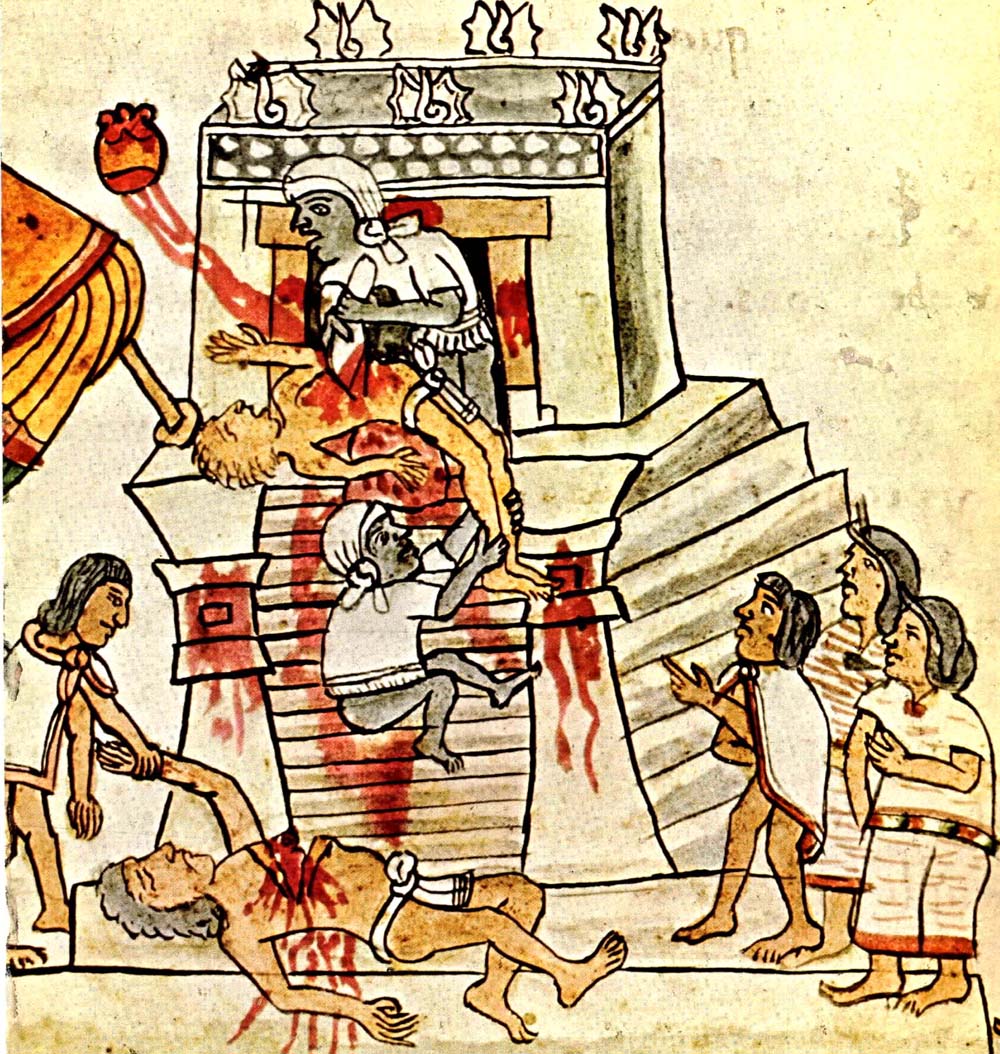

Some historians have stressed the sometimes disturbingly violent nature of Aztec society, and indeed the Spanish justified their conquest partly on accounts of human sacrifice and even rumors of cannibalism. Although Aztec society included many other elements such as the building of the city itself, and creation of its agriculture and its wide network of trade, evidence suggests the culture had a dark side as well. A ruling class of warrior nobles and priests performed ritual human sacrifice daily to sustain the sun on its long journey across the sky, to appease or feed the gods, and to stimulate agricultural production. The sacrificial ceremony included cutting open the chest of a victim (usually but not always a criminal or captured warrior) with an obsidian knife and removing the still-beating heart. The Aztecs taught their children that the best fate a boy could hope for was to die in battle or as a sacrifice to the gods. Women and children were also sometimes sacrificed in elaborate seasonal ceremonies to insure fertility and good harvests.

Questions for Discussion

- How do these details about Mesoamerican culture, and especially the Aztecs, line up with what you previously knew about them?

- Why was it so important for the city of Tenochtitlán to have the stable food supply produced by chinampa farming?

South America

In South America, the most highly developed and complex society was that of the Inca, whose name means “lord” or “ruler” in the Andean language called Quechua. At its height in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Inca Empire, located on the Pacific coast and straddling the Andes Mountains, extended some twenty-five hundred miles. It stretched from modern-day Colombia in the north to Chile in the south and included cities built at an altitude of 14,000 feet above sea level. The empire, called Tawantinsuyu or “four regions together” in Quechua, was a combination of four distinct political and ecological regions.

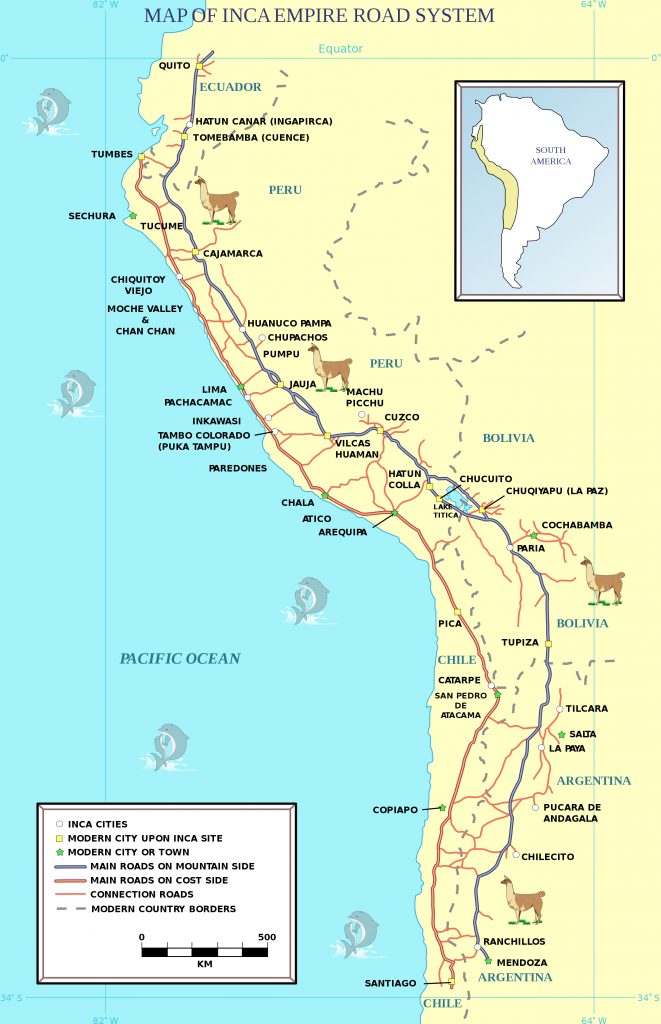

The Inca Royal Road system, built and then regularly repaired by workers stationed at varying intervals along its length, rivaled that of the Romans and efficiently connected the sprawling empire. Since there were no horses or oxen in the Americas to pull carts, the Inca, like all other pre-Columbian American societies, did not use axle-mounted wheels for transportation. Not having to account for wheels allowed them to build stepped roads to ascend and descend the steep slopes of the Andes, which worked well for pedestrians. These roads allowed traders to carry products on the backs of llamas and enabled the rapid movement of the highly-trained Incan army. Also like the Romans, the Inca were effective administrators. Runners called chasquis traversed the roads in a continuous relay system, ensuring quick communication over long distances. The Inca had no system of writing, however. They communicated and kept records using oral traditions and a system of colored strings and knots called the quipu.

The Inca people followed a lord who, as a member of a semi-divine ruling class, had absolute authority over every aspect of life. Much like feudal lords in Europe at the time, the elite class lived off the labor of peasants, accumulating vast wealth that they hoarded believing it would accompany them as they went, mummified, into the next life. The Inca farmed corn, beans, squash, quinoa (a grain cultivated for its seeds), and the indigenous potato on terraced land they hacked from the steep Andes mountains. Farmers in the altiplano, the high Andean plateau, developed potatoes over 9,000 years ago and the village markets of Peru and Bolivia are still crowded with varieties of potatoes the rest of the world has never seen. Peasants were allowed to keep only one-third of their crops to feed their families. The Inca ruler required a third, and the final third was set aside in a kind of welfare system for those unable to work. Huge storehouses were filled with food for times of need. Each peasant also worked for the Inca society a number of days per month on public works projects, in a labor requirement known as the mita. In return, the Inca overlord provided laws, protection, and relief in times of famine.

The Inca worshipped the sun god Inti and called gold the “sweat” of the sun. Unlike the Maya and the Aztecs, they rarely practiced human sacrifice and usually offered the gods food, clothing, and coca leaves. In times of dire emergency, however, such as in the aftermath of earthquakes, volcanoes, or crop failure, they resorted to sacrificing prisoners. The ultimate sacrifice was children, who were specially selected and well fed before being killed. The Inca believed these children would immediately go to a much better afterlife.

In 1911, the American historian Hiram Bingham uncovered the lost Incan city of Machu Picchu. Located about fifty miles northwest of the Inca capital (now Cusco, Peru) at an altitude of about 8,000 feet, the city had been built in 1450 and abandoned roughly a hundred years later, after the Spanish invasion. Scholars believe the city was used for religious ceremonial purposes and housed the priesthood as well as being a summer home for the Inca himself. The architectural beauty of this city is unrivaled. Using only the strength of human labor and no machines, the Inca constructed walls and buildings of polished stones, some weighing over fifty tons, that were fitted together perfectly without the use of mortar. In 1983, UNESCO designated the ruined city a World Heritage Site.

Questions for Discussion

- How do you think the Incas held together an empire that spanned over 2,500 miles?

- How would society be different, without domesticated draft animals like horses or oxen?

North America

With a few exceptions, the North American native cultures were much more widely dispersed than the Mayan, Aztec, and Incan societies, and their population centers did not achieve the sizes or organized social structures of the Central and South American cities. Although the cultivation of corn had made its way north, many Indians still practiced hunting and gathering – especially in regions with short growing seasons. Horses, first introduced by the Spanish, played a part in the later phase of North American native history, allowing the Plains Indians to more easily follow and hunt the huge herds of bison. A few societies had evolved into relatively complex forms, but North American city-states were in decline at the time of Christopher Columbus’s arrival. Most North Americans, it seems, preferred to live a less urban lifestyle. This does not mean their cultures were less sophisticated than those of the city-dwellers to the south or the Europeans, although many Europeans would make this assumption.

In the southwestern part of today’s United States lived several groups we collectively call the Pueblo. The Spanish first gave them this name, which means “town” or “village,” because they lived in towns or villages of permanent stone-and-mud buildings with thatched roofs. Like present-day apartment houses, these buildings had multiple stories, each with multiple rooms. The three main groups of the Pueblo people were the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Anasazi.

The Mogollon thrived in the Mimbres Valley (New Mexico) from about 150 BCE to 1450 CE. The Hohokam decorated pottery with a red-on-buff design and made jewelry of turquoise. In the high desert of New Mexico, the Anasazi, whose name means “ancient enemy” or “ancient ones,” carved homes from steep cliffs accessed by ladders or ropes that could be pulled in at night or in case of enemy attack. Roads extended 180 miles to connect the Pueblos’ smaller urban centers to each other and to Chaco Canyon, which by 1050 CE had become the administrative, religious, and cultural center of their civilization. A century later, however, probably because of drought, the Pueblo peoples abandoned their cities. Their present-day descendants include the Hopi and Zuni tribes.

The Indian groups who lived in the present-day Ohio River Valley and reached their cultural apex from the first century CE to 400 CE are collectively known as the Hopewell culture. Their settlements, unlike those of the southwest, were small villages. They lived in wattle-and-daub houses (made from woven lattice branches “daubed” with wet mud, clay, or sand and straw) and supported themselves with agriculture, hunting, and fishing. Utilizing the region’s many waterways, they developed trade routes stretching from Canada to Louisiana. The Hopewell exchanged goods with other tribes and negotiated in many different languages. From the coast they received shells; from Michigan, copper; and from the Rocky Mountains, obsidian. With these materials they created tools, weapons, necklaces, and exquisite carvings. What remains of their culture today are huge burial mounds and earthworks. Many of the mounds that were opened by archaeologists contained artworks and other goods that indicate their society was socially stratified.

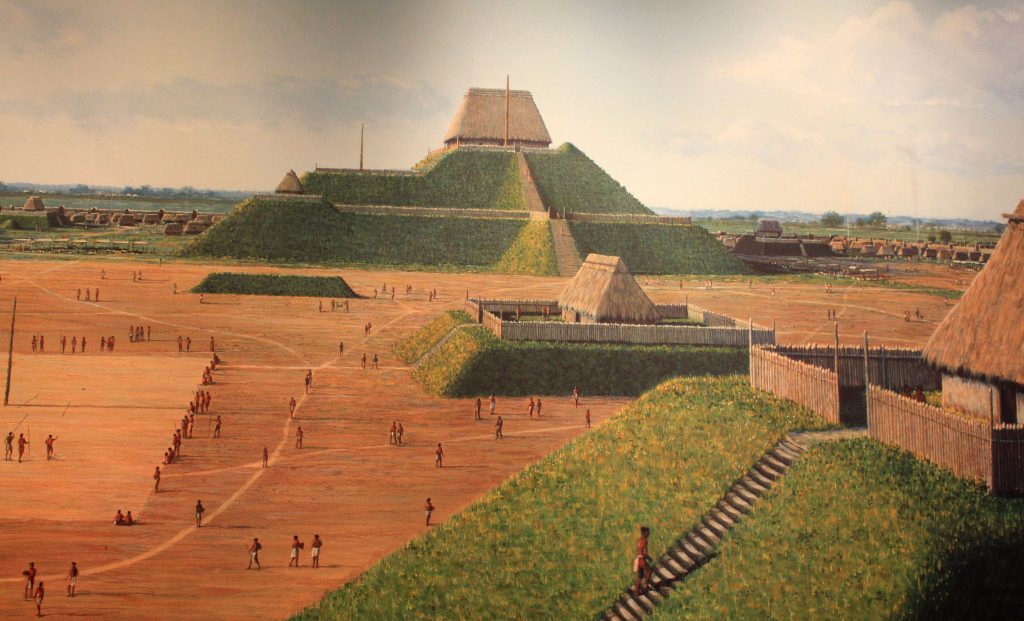

The largest known indigenous cultural and population center in North America was located along the Mississippi River near present-day St. Louis. At its height in about 1100 CE, this five-square-mile city, now called Cahokia, was home to more than ten thousand residents; tens of thousands more lived on farms surrounding the urban center. The city also contained one hundred and twenty earthen mounds or pyramids, each apparently the home of a leader who exercised authority over the surrounding area. The largest mound covered fifteen acres. Cahokia was the hub of political and trading activities along the Mississippi River. After 1300 CE, however, this civilization declined or people decided not to live in a highly stratified, organized society. By the time Europeans arrived the region, although still densely populated, had no major city ruling the Mississippi.

Encouraged by the wealth found by the Spanish in the settled civilizations to the south, fifteenth- and sixteenth-century English, Dutch, and French explorers expected to discover the same in North America. What they found instead were small, scattered communities, many already ravaged by European diseases brought by the Spanish and transmitted among the natives in the century before the new European explorers arrived. Rather than gold and silver, there was an abundance of land, and the timber and fur that land could produce.

The Indians living east of the Mississippi did not construct the large and complex societies of those to the west. Because they lived in small autonomous clans or tribal units, each group adapted to the specific environment in which it lived. Although often connected through trade and intermarriage, these groups were not unified and warfare among tribes was common as each group sought to increase its hunting and fishing areas. Eastern tribes shared many common traits. A chief or group of tribal elders made decisions, and although the chief was male, usually the women selected and counseled him. Men hunted, but women farmed and controlled a larger portion of the tribes’ food supplies. Gender roles were not as fixed as they were in the patriarchal societies of Europe, Mesoamerica, and South America.

Women typically cultivated corn, beans, and squash and harvested nuts and berries, while men hunted, fished, and provided protection. Both parents shared responsibility for raising children, and most major Indian societies in the east were matriarchal. In tribes such as the Iroquois, Lenape, Muscogee, and Cherokee, women had both power and influence. They counseled the chief and passed on the traditions of the tribe. This matriarchy changed dramatically with the coming of the Europeans, who introduced, sometimes forcibly, their own customs and traditions to the natives. Trade with Europeans also decreased the importance of women’s agricultural contributions to the tribes’ subsistence, which lessened their status in Indian society and influence on decision-making.

Clashing beliefs about land ownership and use of the environment would be the greatest area of conflict with Europeans. Although Europeans often claimed the Indians did not practice, or in general even have the concept of, private ownership of land, Eastern tribes regularly entered into contracts to sell lands to white settlers. Since the tribes shifted their hunting and farming as seasons and environmental conditions changed, early land contracts usually specified that the Indians would retain the right to use the land in a variety of ways. As the balance of power between Indian tribes and white communities began to shift in favor of the Europeans, these contracts were typically breached and Indians were prevented from hunting or setting up their camps on the lands they had sold. These breaches of contract and the rapidly-increasing number of white settlers in the colonies became a source of conflict, as we’ll see. A series of wars between Indians and Europeans occasionally threatened the survival of colonial communities, but in general went badly for the Indians.

In contrast, colonists from England and Europe believed in a deity who had created humanity in his own image with the command to use and subdue the rest of creation, which included not only land, but also all animal life. European history had also included famines when agriculture failed to produce enough food to support the population, so there was great social pressure to use the land as productively as possible. Unfortunately, European ideas of effective land use were based on the colonists’ prior experiences in Europe, while Indian land use practices were based on the different conditions of the Americas.

Northeastern Indians shifted their farms from place to place to allow soil fertility to regenerate, and they moved their camps seasonally to take advantage of hunting opportunities and spring fish runs. Upon their arrival in North America, Europeans found no fences, no signs designating ownership. Land, and the game that populated it, they believed, were there for the taking. Europeans failed to notice that the Indians had altered the landscape by burning the understory of the forests to open forest floors and provide more young greenery to attract game animals. Colonists wrote extensively about the parklike forests they found filled with abundant game, but never noticed that the Indians had been actively managing those forests to encourage the wildlife they hunted until it was too late. Generations later, when the Indians were mostly gone from New England, descendants of the first colonists wrote wistfully of a past when hunting and travel through the woodlands had been pleasant and easy. But they still didn’t understand that it had been the native people they had despised as lazy and unproductive, and had driven off the land, who had been responsible for its productivity.

Questions for Discussion

Type your key takeaways here.

- How were native cultures in North America different from those of Mesoamerica and South America?

- Discuss the ways natives adjusted to or altered their environments.

EUROPE

The fall of the Roman Empire (476 CE) and the beginning of the European Renaissance in the late fourteenth century roughly bookend the period we call the Middle Ages. Without a dominant centralized power or overarching cultural hub, European culture became organized around village farming and small communities. In some places peasants worked common lands; in others they worked for feudal lords who offered protection from other lords in exchange for taxes. Few people traveled more than ten miles from the place they were born.

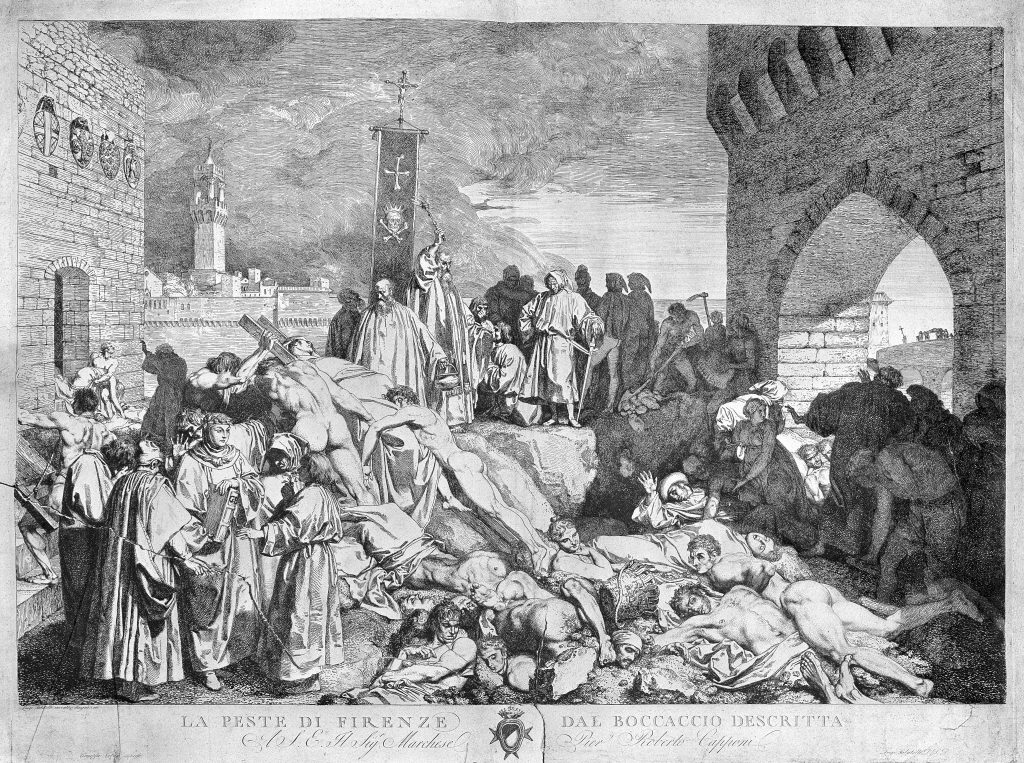

The Christian Church remained intact, however, and emerged from the period as a unified and powerful institution. Priests provided leadership for peasant communities and monks kept knowledge alive by collecting and copying religious and secular manuscripts. While monasteries generally focused on preserving Christian documents, Muslim scholars in the expanding Islamic empires preserved and continued the work of classical philosophy, science, medicine, and mathematics. Social and economic devastation arrived in 1340s, however, when merchants returning from the Black Sea unwittingly brought with them a highly contagious disease known as the bubonic plague. Within a decade the Black Death had killed nearly a hundred million people, about a third of Europe’s population. The loss of so many workers made labor much more valuable and may have awakened some workers to the fact that the ruling class badly needed the food and goods they produced. A high birth rate coupled with bountiful harvests helped the European population rebound during the next century. By 1450, a newly rejuvenated European society was on the brink of tremendous change.

In the seventh and eighth centuries, Islam had spread quickly across North Africa and into the Middle East. Christian Europeans resisted the Muslims in the Crusades and the Spanish Reconquista, which we’ll return to later. As more Europeans marched off to wars in the eastern Mediterranean region, a larger portion of western Europe became familiar with the goods of the East. A lively trade subsequently developed along a variety of routes known collectively as the Silk Road to supply the demand for these products. As Crusaders experienced the feel of silk, the taste of spices, and the utility of porcelain, desire for these products created new markets for merchants. In particular, the Adriatic port city of Venice prospered enormously from trade with Islamic merchants. Merchants’ ships brought Europeans valuable goods, traveling between the port cities of western Europe and the East from the tenth century on, along routes often passing through Muslim empires like the Ottoman. From the days of the early adventurer Marco Polo, Venetian sailors had traveled to ports on the Black Sea and some had established their own colonies along the Mediterranean Coast. For most Europeans, however, transporting goods along the old Silk Road was costly, slow, and unprofitable. Muslim middlemen collected taxes as the goods changed hands. Robbers waited to ambush treasure-laden caravans. A direct water route to the East, cutting out the land portion of the trip, had to be found. As well as seeking a water passage to the wealthy cities in the East, sailors wanted to find a route to the exotic and wealthy Spice Islands in modern-day Indonesia, whose location was kept secret by Muslim rulers. Longtime rivals of Venice, the merchants of Genoa and Florence also looked west.

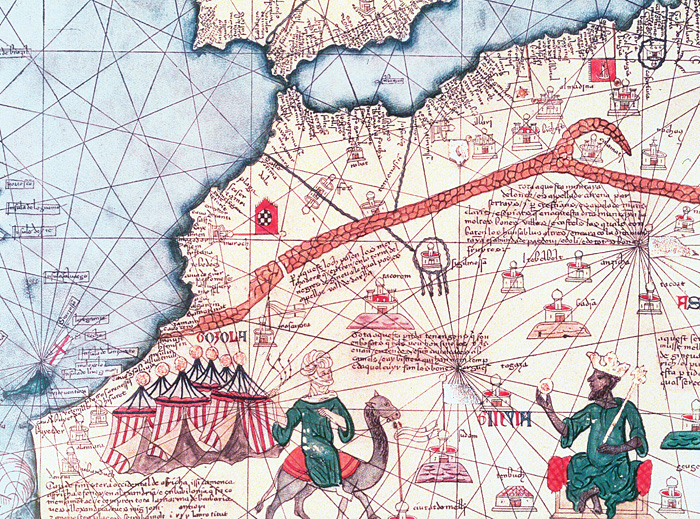

Although Norse explorers such as Leif Ericson, the son of Eric the Red who led the Norse territory of Greenland, had reached and established a colony in northern Canada roughly five hundred years prior to Christopher Columbus’s voyage, it was explorers sailing for Portugal and Spain who traversed the Atlantic throughout the fifteenth century and ushered in an unprecedented age of exploration and permanent contact with North America. Located on the extreme western edge of Europe on the Atlantic coast rather than the Mediterranean, Portugal, with its port city of Lisbon, soon became the center for merchants desiring to undercut the Venetians’ hold on trade. With a population of about one million and supported by its ruler Prince Henry, whom historians call “the Navigator,” Portugal began exploring and trading with western Africa. Skilled shipbuilders and navigators who took advantage of maps from all over Europe, Portuguese sailors used triangular sails and built lighter vessels called caravels that could sail down the African coast.

Just to the east of Portugal, King Ferdinand of Aragon married Queen Isabella of Castile in 1469, uniting two of the most powerful independent kingdoms on the Iberian peninsula and laying the foundation for the modern nation of Spain. Queen Isabella was also a religious zealot: she began the Spanish Inquisition in 1480, a brutal campaign to root out Jews and Muslims who had been forced to convert to Christianity but were suspected of secretly continuing to practice their faith. This powerful couple ruled for the next twenty-five years, centralizing authority and funding exploration and trade with the East. One of their daughters, Catherine of Aragon, became the first wife of King Henry VIII of England.

The year 1492 was the most significant of Ferdinand and Isabella’s reign. The couple oversaw the final expulsion of North African Muslims, called Moors, from the Kingdom of Granada, bringing the nearly eight-hundred-year Reconquista to an end. They also ordered all unconverted Jews to leave Spain. Finally, after six years of lobbying, a Genoese sailor named Christopher Columbus persuaded the monarchs to fund his expedition to the Far East. Columbus had already pitched his plan to the rulers of Genoa and Venice without success and the Portuguese had already discovered and controlled a route to Asia around the bottom of Africa. Columbus’s proposal to cross the Atlantic was the Spanish monarchy’s last hope of controlling a route to Asia. Christian zeal was a prime motivating factor for Isabella, as she imagined her faith spreading to the East. Ferdinand hoped to acquire wealth from trade.

Questions for Discussion

- How did the conflict between Christians and Muslims influence European history?

- Why does it seem to matter so much to people, who “discovered” America?

- Why did Spain (and not another nation) sponsor Columbus’ journey across the Atlantic?

AFRICA

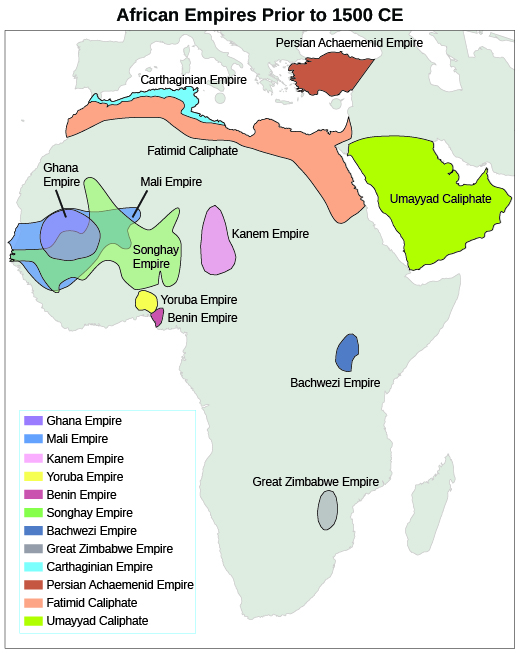

Following the death of the prophet Muhammad in 632 CE, Islam had spread quickly across North Africa, bringing not only a unifying faith but a political and legal structure as well. The first major empire to emerge in West Africa was the Ghana Empire. By 750, the Soninke farmers of the sub-Sahara had become wealthy by taxing the trade that passed through their area. For instance, the Niger River basin supplied gold to the Berber and Arab traders from west of the Nile Valley, who brought cloth, weapons, and manufactured goods into the interior. Huge Saharan salt mines supplied the life-sustaining mineral to the Mediterranean coast of Africa and inland areas. By 900, Muslims controlled most of this trade and had converted many of the African ruling elite. The majority of the population, however, maintained their tribal animistic practices, which gave living attributes to nonliving objects such as mountains, rivers, and wind. Because Ghana’s king controlled the gold supply, he was able to maintain price controls and afford a strong military. Soon, however, a new kingdom emerged.

By 1200 CE Mali had replaced Ghana as the leading state in West Africa. Muslim scribes played a large part in administration and government. By the fourteenth century, the empire was so wealthy that while on a hajj, or pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca, Mali’s ruler Mansu Musa gave away enough gold to create serious price inflation in the cities along his route. Timbuktu, the capital city, became a leading Islamic center for education, commerce and the slave trade.

The institution of slavery is not a recent phenomenon. Most civilizations have practiced some form of human bondage and unfree labor, and African empires were no different. Similar to the European serf system, those seeking protection, or relief from starvation, would become the servants of those who provided relief. People taken in battle were also traditionally enslaved. Debt might also be worked off through a form of servitude. Typically, these unfree workers became a part of the extended tribal family and their children were treated as full members of society. There is some evidence of chattel slavery, in which people are treated as personal property to be bought and sold, in the Nile Valley. It also appears there was a slave-trade route through the Sahara that brought sub-Saharan Africans to Rome, which had slaves from all over the world.

Arab slave trading, which exchanged slaves for goods from the Mediterranean, existed long before Islam’s spread across North Africa. Muslims later expanded this trade and enslaved not only Africans but also Europeans, especially from Spain, Sicily, and Italy. Male captives were forced to build coastal fortifications and serve as galley slaves. Women were added to the harem. The major European slave trade began with Portugal’s exploration of the west coast of Africa in search of a trade route to the East. By 1444, slaves were being brought from Africa to work on Portuguese sugar plantations of the Madeira Islands, off the coast of modern Morocco. The slave trade would expand greatly as European colonies in the New World demanded an ever-increasing number of workers for extensive plantations growing tobacco, sugar, and eventually rice and cotton, as we will see in later chapters.

Question for Discussion

- We’re going to talk a lot about the Atlantic slave trade as we proceed. Has the content presented here changed your understanding of the origins of slavery?

Media Attributions

- Beringia_land_bridge-noaagov © NOAA is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Mesoamerica_english

- San_Lorenzo_Monument_3 © Maribel Ponce Ixba is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Chichen_Itza_3 © Daniel Schwen is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Reconstruction_of_Tenochtitlan2006 © Xuan Che is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Lake_Texcoco_c_1519 © Madman2001 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Codex_Magliabechiano_(141_cropped)

- Inca_road_system_map © Manco Capac is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Over_Machu_Picchu © icelight is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 2560px-Ancient_ruins_in_the_Cañon_de_Chelle_10055u © Timothy H. O'Sullivan is licensed under a Public Domain license

- illinois-cahokia-half-picture-of-cahokia © Unknown is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- CNX_History_01_01_Tribes-1 © CNX/Openstax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 16530515369_afe2bf0045_b © BLMOregon is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- L0004057 The plague of Florence in 1348, as described in Boccaccio’s © L. Sabatelli is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- I._E._C._Rasmussen_-_Sommernat_under_den_Grønlandske_Kyst_circa_Aar_1000 © Carl Rasmussen is licensed under a Public Domain license

- La_rendición_de_Granada © Francisco Padilla Ortiz is licensed under a Public Domain license

- CNX_History_01_03_AfricanEmp © CNX/Openstax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- West_Africa_Catalan_Atlas © Flad is licensed under a Public Domain license