6 Democracy in America

Westward expansion and war between Great Britain and France in the 1790s shaped early United States foreign policy. As a new, indebted, and relatively weak nation, the American republic had no control over European events and no real leverage to obtain its goals of trading freely in the Atlantic. George Washington, reelected in 1792 by an overwhelming majority, refused to run for a third term, eliminating the threat that his presidency would become a monarchy and setting a precedent for future presidents. In the presidential election of 1796, the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties competed for the first time. Partisan division over the French Revolution and the Whiskey Rebellion fueled the divisiveness and Washington’s vice president, Federalist John Adams, defeated his Democratic-Republican rival Thomas Jefferson by a narrow margin of only three electoral votes. Adams won the New England and Mid-Atlantic states and Jefferson took the South and Pennsylvania. As loser in the presidential race, Jefferson became Adams’s Vice President (“Tickets” including both the presidential and vice-presidential candidate began in 1800 and a separate ballot for Vice President was implemented in 1804).

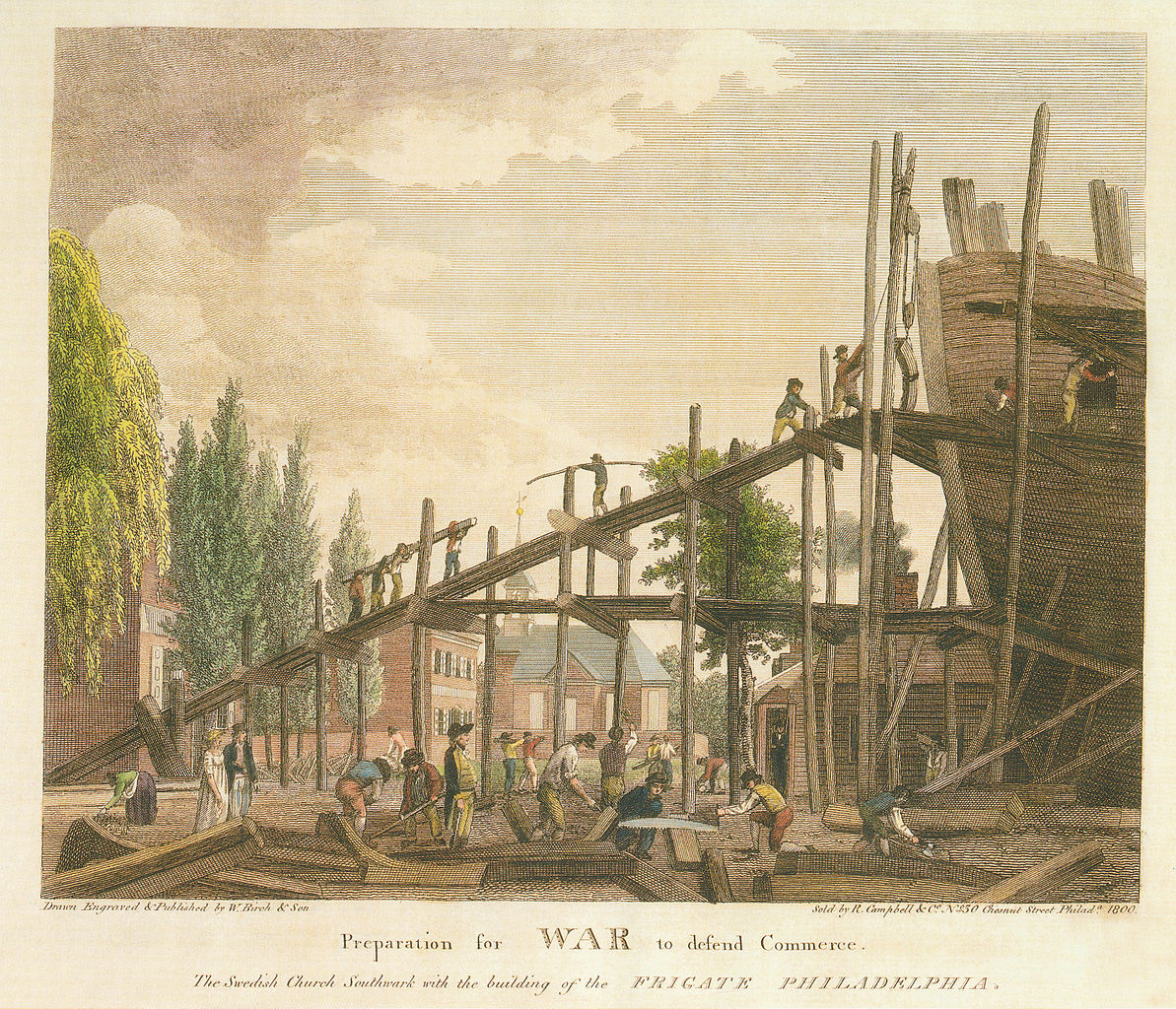

To Federalist president John Adams, relations with France posed the biggest problem. After the execution of Robespierre and the end of the Reign of Terror, the French wrote a new constitution that backed away from the democratic ideals of the revolution and a five-man committee called the Directory ruled France from 1795 to 1799. The Directory was continually at war with coalitions of enemies including the Ottoman Empire, Austria, Prussia, and the Kingdom of Naples. Great Britain was a constant foe and France issued decrees stating that any ship carrying British goods could be seized on the high seas. In practice, this meant the French would target American ships, especially those in the West Indies, where the United States conducted a brisk trade with the British. France declared its 1778 treaty with the United States null and void, and France and the United States waged an undeclared war from 1796 to 1800. Between 1797 and 1799, the French seized 834 American ships, and President Adams urged the buildup of the U.S. Navy, which had consisted of only a single vessel at the time of his election in 1796.

In 1797, President Adams sought a diplomatic solution to the conflict with France and dispatched envoys to negotiate terms. The French foreign minister, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, told the American envoys that the United States must repay all outstanding debts owed to France, lend France 32 million guilders (Dutch currency), and pay a £50,000 bribe before any negotiations could take place. News of the attempt to extract a bribe, known as the XYZ affair, outraged the American public and turned public opinion against France. In the court of public opinion, Federalists appeared to have been correct in their interpretation of France, while the pro-French Democratic-Republicans had been misled. At about the same time, rumors began to circulate of a German secret society called the Illuminati that critics accused of starting the French Revolution and attempting to spread the anarchist-democratic ideals of that revolution to America. Federalist politicians and American pastors (including Jedediah Morse, a very influential minister and author and father of the painter of the Adams portrait above) wrote and preached to warn Americans against the threat of the secret (and Catholic) Illuminati who they imagined had infiltrated and taken over the rival Democratic-Republican party. No evidence was ever found to support their accusations, and the conspiracy theories diminished after the election of Jefferson failed to result in the destruction of the republic.

The complicated situation in Haiti, which remained a French colony in the late 1790s under the control of the former slaves who had rebelled against the white planters, also came to the attention of President Adams. The Haitian leader Toussaint L’Ouverture, who had to contend with various domestic rivals seeking to displace him as well as a five-year long British invasion, wished to end the U.S. embargo on France and its colonies. In early 1799, in order to capitalize upon trade in the lucrative West Indies and undermine France’s hold on the island, Congress ended the ban on trade with Haiti—a move that acknowledged L’Ouverture’s leadership, to the horror of American slaveholders.

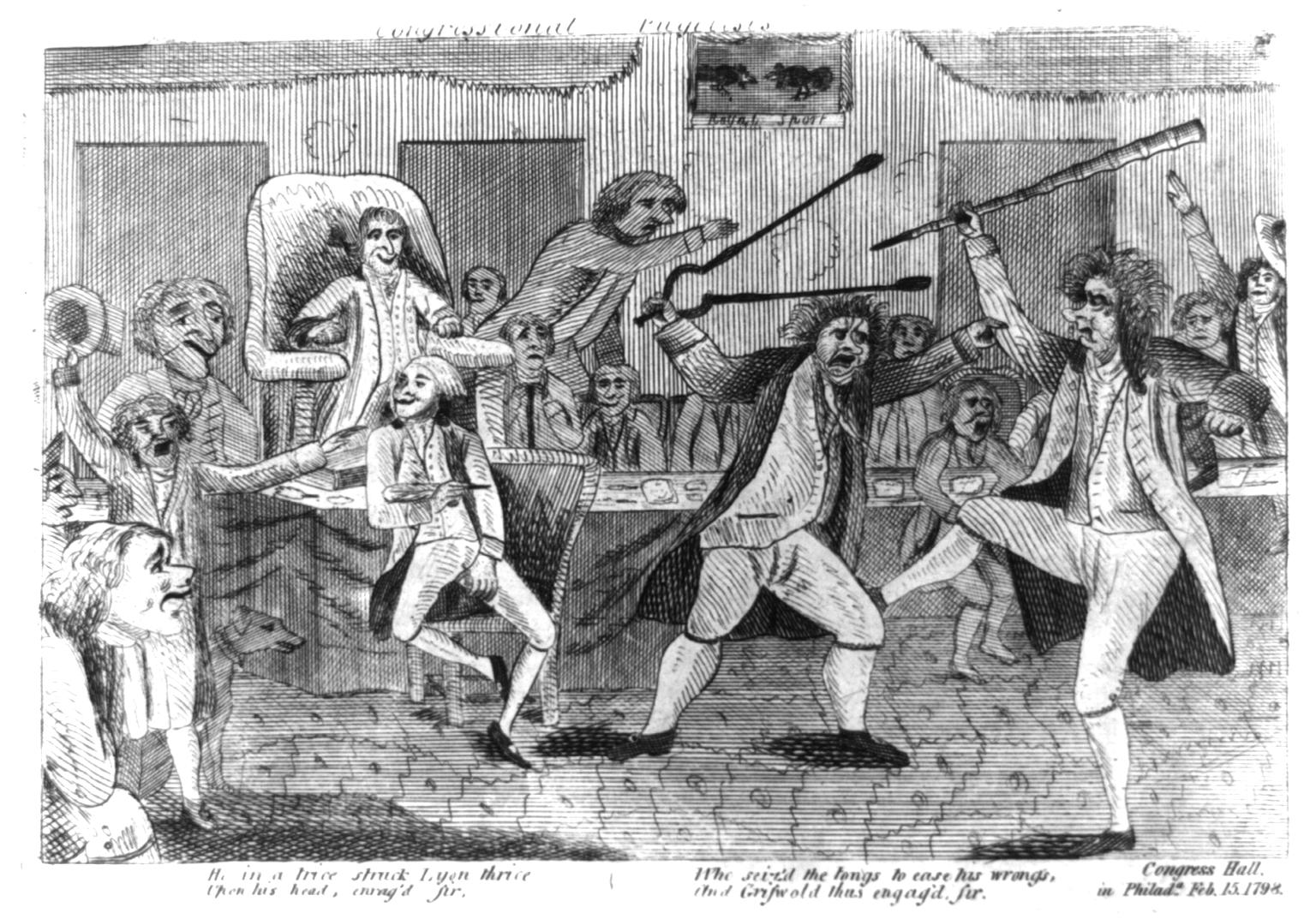

The surge of animosity against France during the undeclared war led Congress to pass several measures that in time undermined Federalist power. These 1798 war measures, known as the Alien and Sedition Acts, aimed to increase national security against what most had come to regard as the French menace and the Illuminati. The Alien Act and the Alien Enemies Act took particular aim at French immigrants fleeing the West Indies by giving the president the power to deport new arrivals who appeared to be a threat to national security. The act expired in 1800 with no immigrants having been deported. The Sedition Act was directed against U.S. citizens, imposing up to five years’ imprisonment and a massive fine of $5,000 on people convicted of speaking or writing “in a scandalous or malicious” manner against the government of the United States. Twenty-five men, all members of the opposition party, were indicted under the act, and ten were convicted. One of these was Congressman Matthew Lyon, Democratic-Republican representative from Vermont, who had launched his own newspaper, The Scourge Of Aristocracy and Repository of Important Political Truth.

The Alien and Sedition Acts raised important constitutional questions about the freedom of the press provided under the First Amendment. Democratic-Republicans argued that the acts were evidence of the Federalists’ intent to squash individual liberties and, by enlarging the powers of the national government, crush states’ rights. Jefferson and Madison mobilized the response to the Adams administration’s laws in statements known as the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, which argued that the acts were illegal and unconstitutional. The resolutions introduced the idea of nullification, the right of states to nullify acts of Congress, and advanced the argument of states’ rights. The ideas introduced in these resolutions would later become central in the fight over slavery. The undeclared war with France came to an end in 1800, when President Adams was able to secure the Treaty of Mortefontaine. His willingness to open talks with France divided the Federalist Party, but the treaty reopened trade between the two countries and ended the French practice of taking American ships on the high seas.

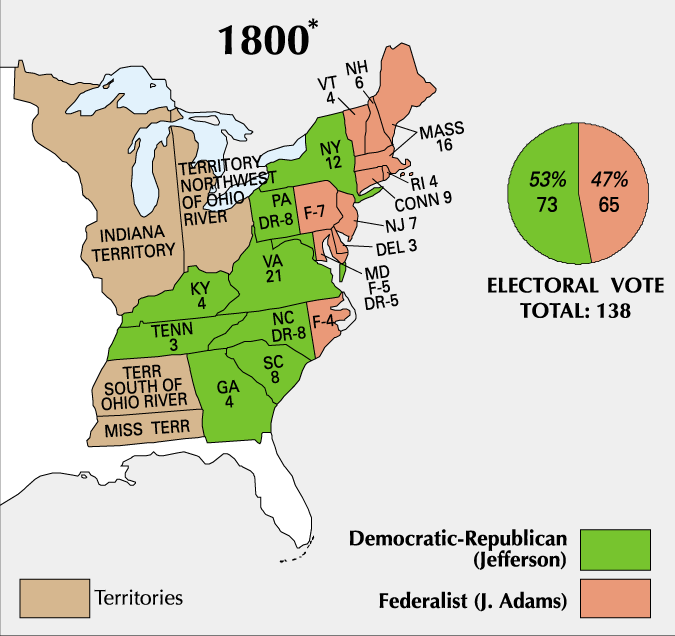

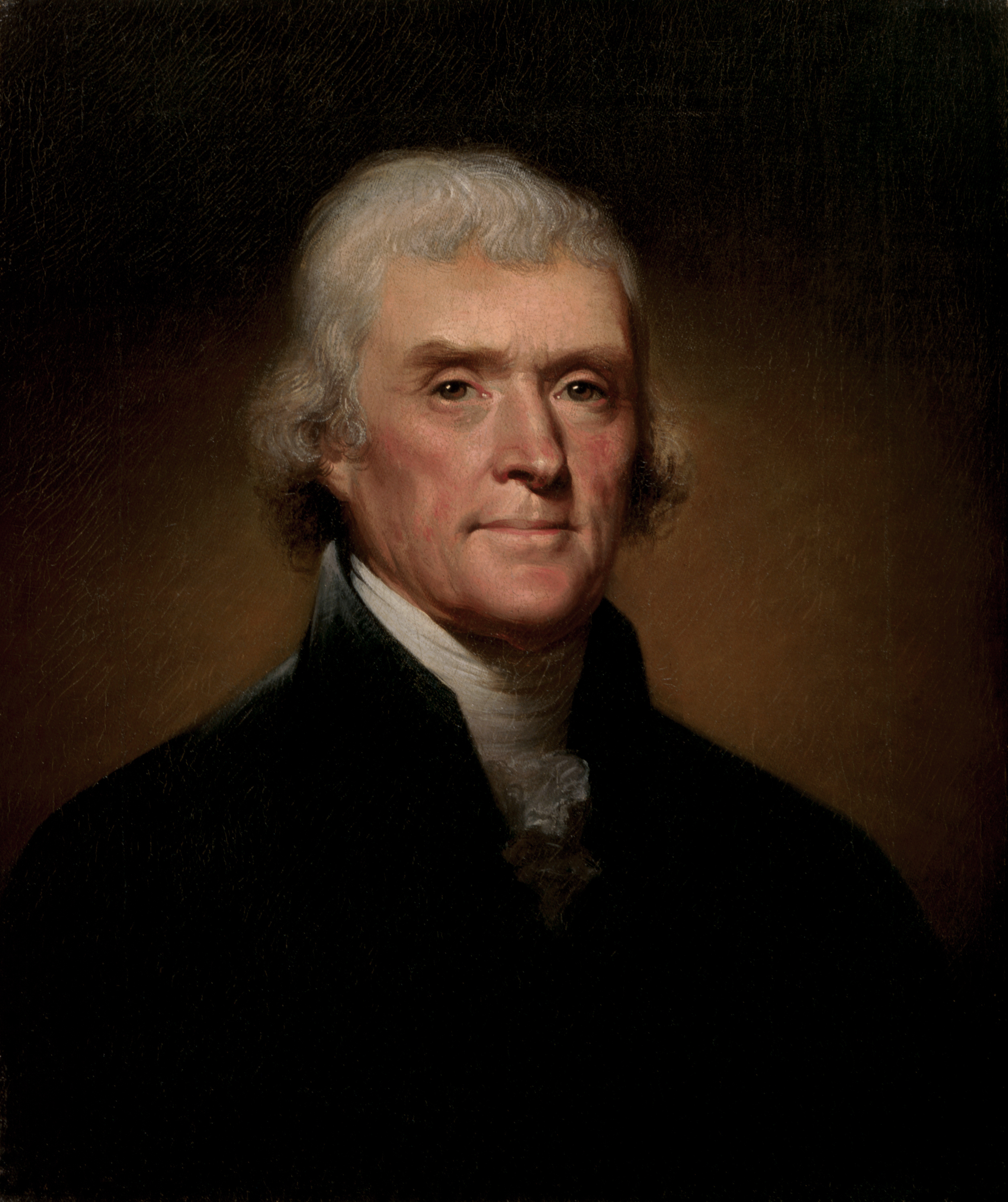

In 1800, another close election swung the other way. Jefferson picked up half of Maryland’s electoral votes but lost nearly half of Pennsylvania’s. The big difference was that by making New York Senator Aaron Burr his running-mate, Jefferson won all of New York’s 12 electoral votes, beginning a long period of Democratic-Republican government. The term “Revolution of 1800″ refers to the first transfer of power from one party to another in American history, when the presidency passed from Federalist John Adams to his vice president and political adversary, Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson. The peaceful transition of political power from one political party to another without bloodshed set an important precedent, especially after the rhetoric of the campaign which included suggestions that Jefferson’s party was a puppet for foreign powers or the Illuminati, and that anarchy and chaos would follow a Federalist defeat.

The election was much more divisive than the 1796 election had been, as both the Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties waged a mudslinging campaign unlike any seen before. Because the Federalists were badly divided, the Democratic-Republicans gained political ground. Alexander Hamilton, who disagreed with President Adams’s approach to France, wrote a lengthy letter, meant for people within his party, attacking his fellow Federalist Adams’ character and judgment and ridiculing his handling of foreign affairs. Democratic-Republicans happily reprinted the letter. Jefferson viewed participatory democracy as a positive force for the republic, a direct departure from Federalist views. His version of participatory democracy was only slightly more inclusive than that of the Federalists, however, extending only to the white yeoman farmers in whom Jefferson placed great trust. While Federalist statesmen, like the architects of the 1787 Constitution, feared a pure democracy and preferred to vest political power in the hands of merchants, bankers, and wealthy plantation owners, Jefferson was far more optimistic that the common American farmer could be trusted to make good decisions. Jefferson had cheered the French Revolution and had not objected when the French republic instituted the Terror to ensure the monarchy would not return. While residing in France in the late 1780s, Jefferson had written to a U.S. diplomat that “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.” By 1799, however, he had rejected the cause of France because of his opposition to Napoleon’s seizure of power and creation of a dictatorship.

Over the course of two terms as president, Jefferson reversed the policies of the Federalist Party by turning away from urban commercial development and early industrialization. Instead, he promoted agriculture through the sale of western public lands in small and affordable lots. Perhaps Jefferson’s most lasting legacy is his vision of an “empire of liberty.” He distrusted cities and instead hoped to build a rural republic of land-owning white men, or yeoman republican farmers. He wanted the United States to be the breadbasket of the world, exporting its agricultural commodities without suffering the ills of urbanization and industrialization. Men who worked for wages, he believed, could be intimidated by their employers into voting for the candidates preferred by their bosses (Ballots were not secret during this period; Massachusetts was the first state to adopt a secret ballot in 1888). Since American yeomen would own their own land, they could stand up against those who might try to influence their votes with threats or promises. Jefferson championed the rights of states and insisted on limited federal government as well as limited taxes. This stood in stark contrast to the Federalists’ insistence on a strong, active federal government. Jefferson also believed in fiscal austerity. He pushed for, and Congress approved, an end of all internal taxes such as those on whiskey and rum. The most significant trimming of the federal budget came at the expense of the military; Jefferson did not believe in maintaining a costly military during peacetime and he slashed the size of the navy Adams had worked to build. Nonetheless, Jefferson responded to the capture of American ships and sailors by pirates off the coast of North Africa by sending the U. S. Navy to war against the Muslim Barbary States in 1801, the first conflict fought by Americans overseas.

The slow decline of the Federalists, which began under Jefferson, led to a period of one-party rule in national politics. Historians call the years between 1815 and 1828 the “Era of Good Feelings” and highlight the “Virginia dynasty” of the time, since the next two presidents who followed Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe, both hailed from his home state. Like Jefferson, they both owned slaves and represented the Democratic-Republican Party. Though Federalists continued to enjoy regional popularity, especially in the Northeast, their days of prominence in setting foreign and domestic policy had ended. And partisan divisions sometimes flared up into violence. The animosity between the political parties exploded in 1804, when Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s vice president, killed Federalist Alexander Hamilton in a duel. When Democratic-Republican Burr discovered he would not be Jefferson’s running-mate in 1804, he ran for governor of New York. Burr lost to another Democratic-Republican, but blamed his defeat on Hamilton, who had been quoted in a newspaper article written to discredit him. On July 11, the two rivals met in New Jersey for a duel in which Burr shot Hamilton.

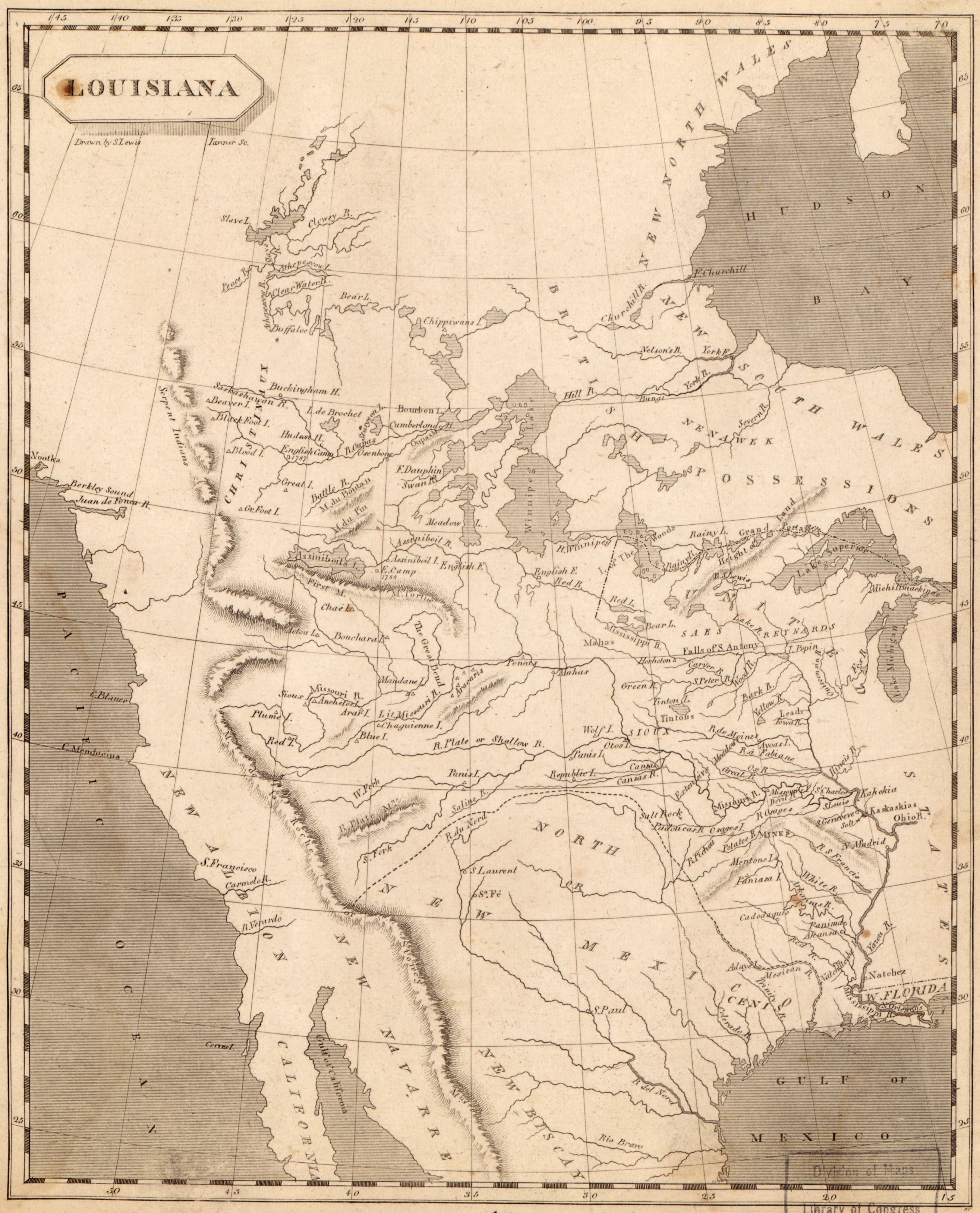

Jefferson realized his greatest triumph in 1803 when the United States bought the Louisiana territory from France. Louisiana, which had been a French Province since the seventeenth century, had been ceded to Spain in 1762 at the end of the French and Indian War. Napoleon had re-acquired the North American territory for France in 1800, but mounting debts from his failed attempt to reconquer Haiti (which in 1804 became the second former colony in the Americas to achieve independence from Europe and the only nation ever established by former slaves) and the prospect of a new war with Britain convinced the Emperor of the French to give up his ambition to return France to the Americas. For $15 million—a bargain price, considering the 828,000 square miles of land involved—the Louisiana Purchase greatly enhanced the Jeffersonian vision of the United States as an agrarian republic in which yeomen farmers would work the land. The United States doubled in size. Initially, Jefferson had only hoped to buy the city of New Orleans bolster trade in the West, seeing the port on the delta of the Mississippi River (then the western boundary of the United States) as crucial to America’s agricultural commerce. In his mind, farmers would send their produce down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where it could be put on ships or sold to European traders. When Spain had controlled New Orleans the United States had been allowed to traffic goods in the port without paying customs duties. Under French control of the city, the United States lost its right to deposit goods free in the port. Jefferson instructed Robert Livingston, the American envoy to France, to secure access to New Orleans, sending James Monroe to France to add additional pressure. The timing proved advantageous. Napoleon’s plan to make Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley a French-controlled breadbasket for Haiti, the most profitable sugar island in the world, was clearly failing. The emperor agreed to the sale in early 1803.

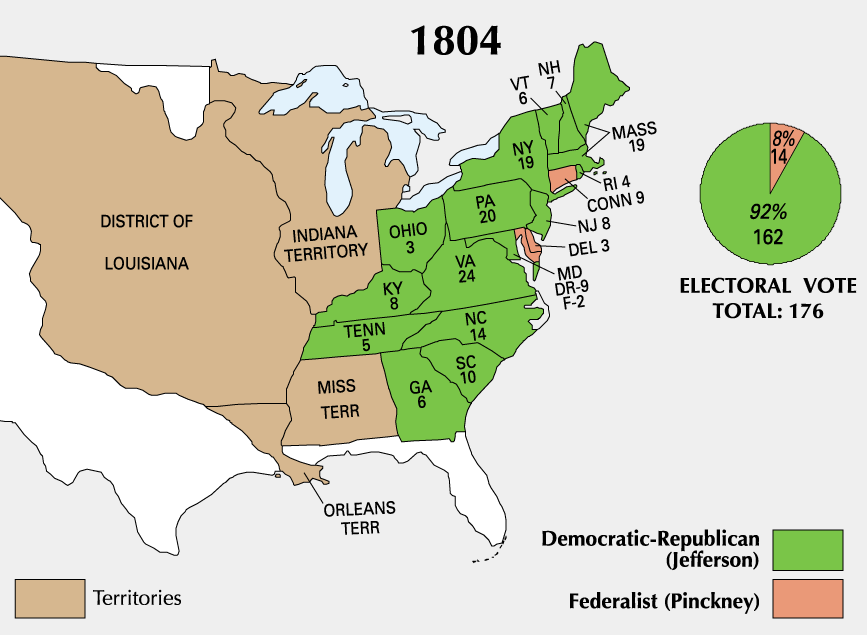

The Louisiana Purchase helped Jefferson win reelection in 1804 by a landslide. Of 176 electoral votes cast, all but 14 went to Jefferson. The great expansion of the United States did have its critics, however, especially northerners who feared both the addition of more slave states and reduced representation of their interests inCongress. And under a strict interpretation of the Constitution, it remained unclear whether President Jefferson had actually possessed the legal authority to add territory in this fashion. But the vast majority of citizens cheered the vast increase in the size and apparent importance of the republic. For slaveholders, new western lands would be a boon; for slaves, the Louisiana Purchase threatened to entrench their suffering further.

France and England continued their conflict in Europe and on the high seas during the Napoleonic Wars that raged between 1803 and 1815. Both declared open season on American ships, which they seized regularly. England was the major offender, the Royal Navy following a long-standing practice of “impressing” American sailors into its service. The issue came to a head in 1807 when the British warship HMS Leopard opened fire on a U.S. naval ship off the coast of Norfolk Virginia. The British boarded the ship and took four sailors. Having little power to force Britain to stop, Jefferson responded to the crisis with a sweeping ban on trade. The Embargo Act of 1807 prohibited American ships from leaving their ports until Britain and France stopped seizing them on the high seas. In early January, the Act was amended to include fishing boats, coastal traders, and whalers. As a result of the embargo, American commerce came to a near-total halt. The logic behind the embargo was that cutting off all trade would so severely damage the British and French economies that the seizures at sea would end. However, while the embargo did have some economic impact on the Britain, American commercial interests suffered more. The embargo hurt American farmers in addition to merchants, and seaport cities experienced increased unemployment and a rise in bankruptcies. American business activity declined by 75 percent from 1808 to 1809.

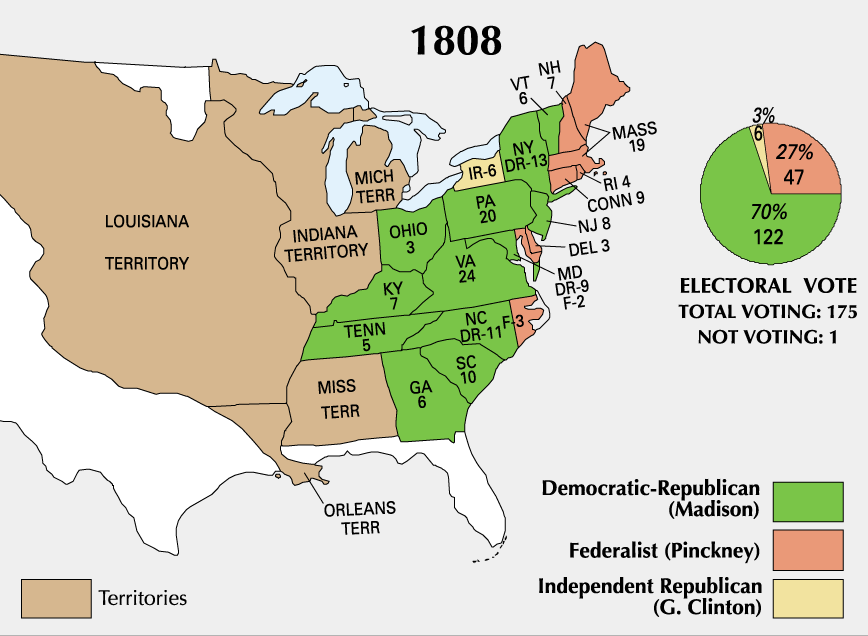

Enforcement of the embargo proved very difficult, especially in the states bordering British Canada. Smugglers’ Notch in Vermont, for example, earned its name from illegal trade with British Canada. President Jefferson attributed the problems with the embargo to lax enforcement. British merchants shifted their focus to South America and were actually happy to have less competition from American merchants. Critics of Jefferson observed that the champion of a small government that stayed out of citizens’ affairs was assuming extraordinary coercive powers to try to enforce his embargo. At the very end of his second term, Jefferson relented and signed the Non-Intercourse Act of 1808, lifting the unpopular embargoes on trade except with Britain and France. In the election of 1808, American voters elected another Democratic-Republican, James Madison. The Federalists again nominated South Carolinian Charles C. Pinckney, whom Jefferson had beaten decisively in 1804. Although Pinkney again did poorly in the South against the Virginian Madison, he did manage to win the Federalist-leaning New England states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. President Madison inherited Jefferson’s foreign policy problems with Britain and France. Most people in the United States, especially those in the West, saw Great Britain as a major problem.

The issue that concerned Americans on the western border was British support for native resistance to U.S. expansion. For many years, white settlers in the American western territories had steadily encroached on the Indians living there. Under Jefferson, the U.S. had practiced two main policies toward the natives: forcing Indians to adopt American ways of agricultural life, or aggressively driving Indians into debt in order to force them to sell their lands. In 1809, Tecumseh, a Shawnee war chief, began leading a Western Confederacy of tribes. His brother, Tenskwatawa, was a spiritual leader and prophet who urged a revival of native ways and rejection of Anglo-American culture, including alcohol. Tecumseh objected to a treaty signed by some but not all of the tribes in the region, selling 3 million acres of land to the United States. William Henry Harrison, the governor of the Indiana Territory, argued that the treaty he had negotiated was valid and that the Indians who signed it had the right to act for all their people. While Tecumseh was away trying to rally support for his cause, Harrison attempted to eliminate the natives by attacking Prophetstown, the Shawnee settlement named in honor of Tenskwatawa. Although he was not a military leader, Tenskwatawa led an Indian force into the field against Harrison. In the ensuing Battle of Tippecanoe, U.S. forces destroyed the settlement and confiscated 5,000 bushels of corn and beans the Indians had saved for the winter. They also found ample evidence that the British had supplied the Western Confederacy with weapons, despite the stipulations of earlier treaties.

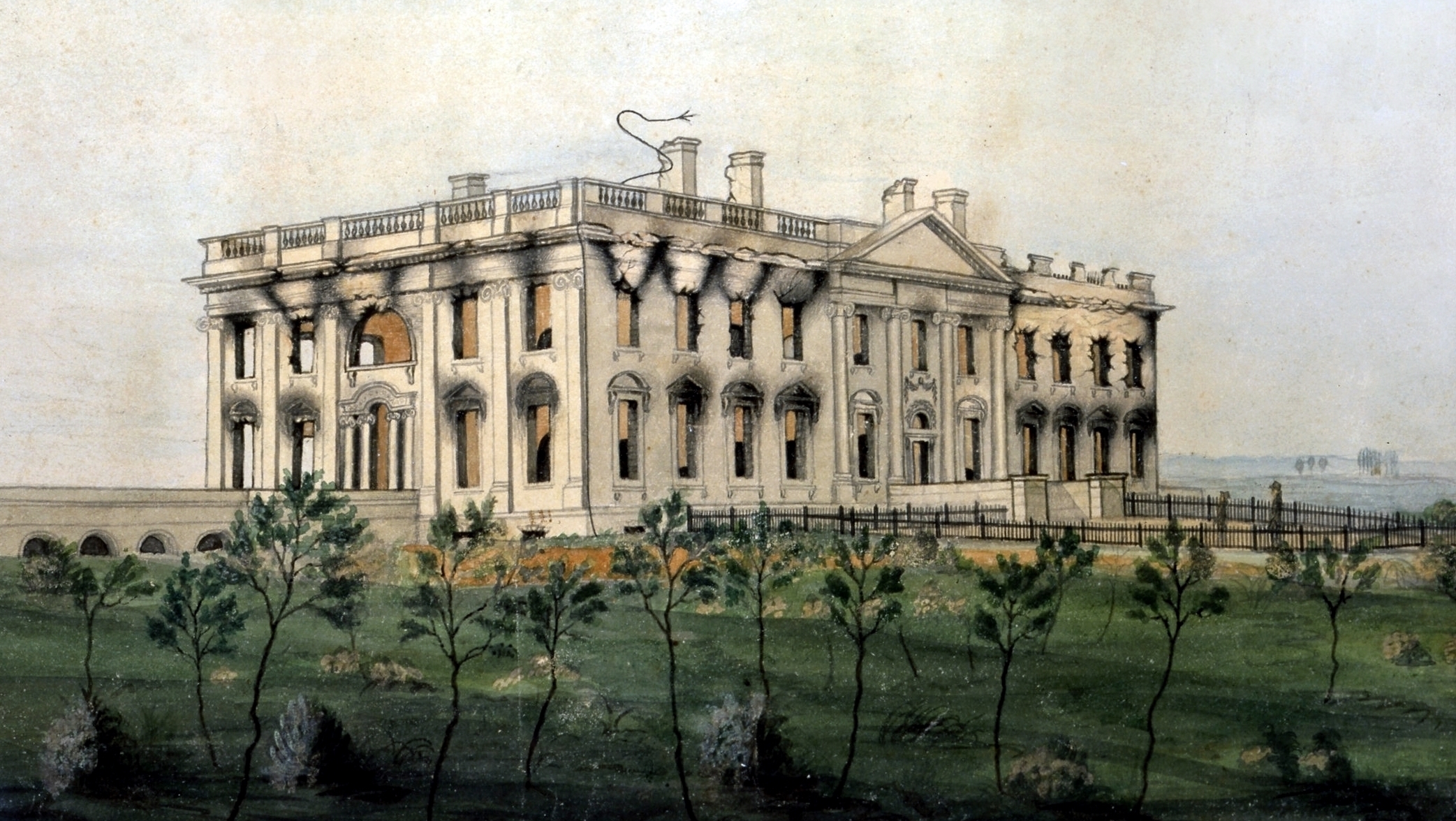

The seizure of American ships and sailors, and British support of Indian resistance led to strident calls for war against Great Britain. The loudest came from “war hawks” led by Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who spoke angrily in Congress of British insults to American honor. Opposition to the war came from Federalists, especially in the Northeast, who knew war would disrupt the maritime trade on which the region’s economy depended. In a narrow vote, Congress authorized the President Madison to declare war against Britain in June 1812. The war went very badly for the United States. In August 1812, the United States lost Detroit to the British and their Indian allies, including a force of one thousand men led by Tecumseh. By the end of the year, the British controlled half the Northwest. The following year, however, U.S. forces scored a few victories. Captain Oliver Hazard Perry and his naval force defeated the British on Lake Erie. At the Battle of the Thames in Ontario, the United States defeated the British and their native allies, and Tecumseh was counted among the dead. The Indian resistance lost an important leader, opening the Indiana and Michigan territories for white settlement. These victories could not turn the tide of the war, however. Britain had gained the upper hand in the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and the French army was on the run, allowing battle-hardened British combat troops to be diverted from Europe to fight in the United States. In July 1814, forty-five hundred British soldiers sailed up the Chesapeake Bay and burned Washington DC to the ground, forcing President Madison and his wife to flee for their lives. That summer, the British shelled Baltimore, hoping for another victory. However, they failed to dislodge the U.S. forces, whose survival of the bombardment inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

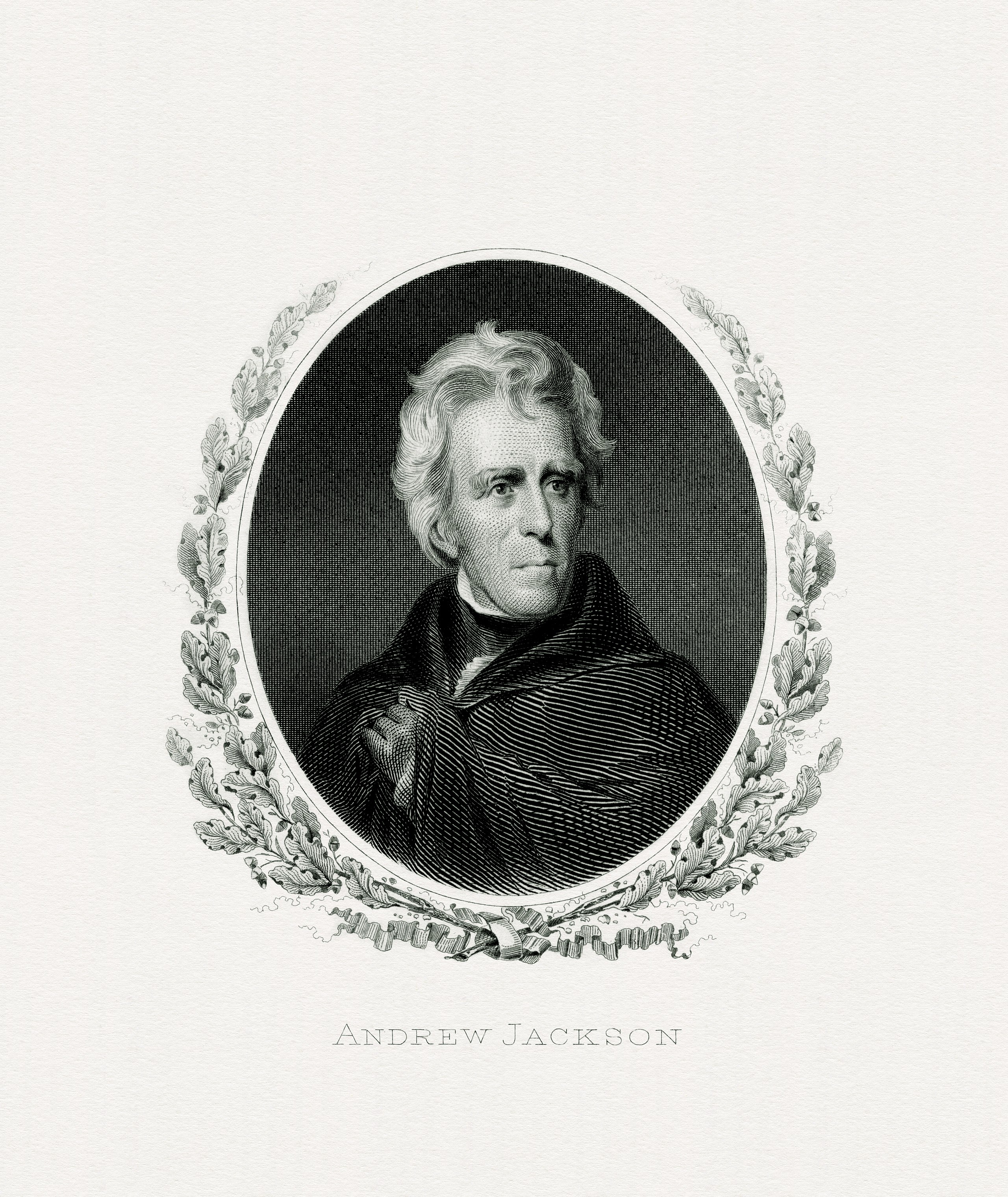

With the end of the war in Europe, Britain was eager to end the conflict in the Americas as well. In 1814, British and U.S. diplomats met in Flanders, in northern Belgium, to negotiate the Treaty of Ghent, signed in December. The boundaries between the United States and British Canada remained as they had been before the war, a relief to those in the United States who had feared a rupture in the country’s otherwise steady expansion into the West. Due to slow communication, the last battle in the War of 1812 happened after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed ending the war. Andrew Jackson had distinguished himself in the war by defeating the Creek Indians in March 1814 before invading Florida in May of that year. After taking Pensacola, he moved his force of Tennessee fighters to New Orleans to defend the strategic port against British attack. On January 8 1815 a force of battle-tested British veterans of the Napoleonic Wars attempted to take the port. Jackson’s forces devastated the British, killing over two thousand. Although the war was over and the battle’s outcome would not change the terms of the treaty, Jackson’s victory was symbolic. New Orleans and the Mississippi River Valley had been successfully defended, ensuring the future of American settlement and commerce. The Battle of New Orleans immediately catapulted Jackson to national prominence as a war hero and in the 1820s he emerged as the head of the new Democratic Party.

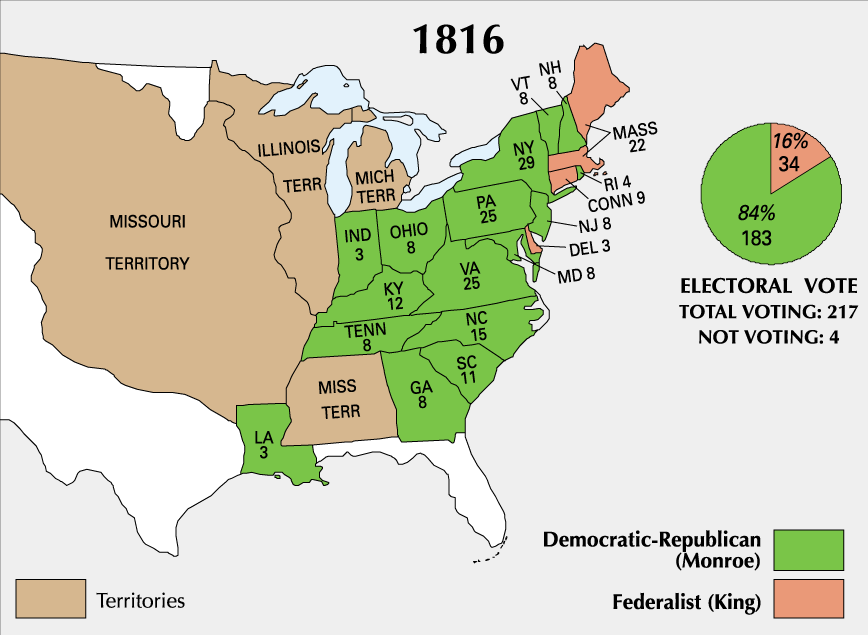

The War of 1812 was very unpopular in New England because it damaged the economy of a region dependent on maritime commerce. This unpopularity caused a resurgence of the Federalist Party in New England. Many Federalists deeply resented the power of the slaveholding Virginians, Jefferson and Madison, who appeared indifferent to their region. The depth of the Federalists’ discontent came to a head at the December 1814 Hartford Convention, a meeting of twenty-six Federalists in Connecticut, where some attendees suggested New England should secede from the United States. These arguments for disunion during wartime, combined with the convention’s condemnation of the government, made Federalists appear unpatriotic. The convention forever discredited the Federalist Party and accelerated its downfall. After 1816, in which Democratic-Republican James Monroe defeated his Federalist rival Rufus King, the Federalist Party never ran another presidential candidate.

Before the 1820s, a code of deference had been a central feature of the republic’s political order. Deference was the practice of showing respect for individuals who had distinguished themselves through military accomplishments, educational attainment, business success, or family pedigree. Deference shown to members of what many Americans in the early republic agreed was a natural aristocracy dovetailed with republicanism and its emphasis on virtue, the ideal of placing the common good above narrow self-interest. Republican statesmen in the 1780s and 1790s expected and routinely received deferential treatment from others, and ordinary Americans deferred to their “social betters” as a matter of course. Federalists believed American deference was less aristocratically-based than that of Britain; their political opponents disagreed.

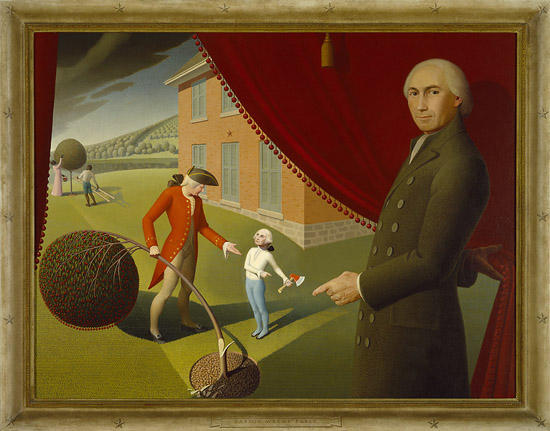

For the generation who lived through the American Revolution, George Washington epitomized republican virtue and deserved great deference from his countrymen. Washington’s judgment and decisions were considered beyond reproach. An Anglican minister named Mason Locke Weems contributed to the legend of Washington’s unimpeachable virtue in his 1800 book, The Life of Washington. Generations of nineteenth-century American children read Weems’ fictional story of a youthful Washington chopping down one of his father’s cherry trees and, when confronted by his father, confessing: “I cannot tell a lie”. The story illustrated Washington’s unflinching honesty and integrity, encouraging readers to both follow Washington’s example and to remember the deference owed to such towering national figures.

Washington and those who celebrated his role as president established a standard for elite, virtuous leadership that cast a long shadow over subsequent presidential administrations. Stories like those told by Weems emphasized Washington’s nobility and downplayed the fact that he was the wealthiest president in U.S. history and had been an aristocrat long before he became a revolutionary. The presidents who followed Washington shared the first president’s pedigree. With the exception of John Adams, who was from Massachusetts, all the early presidents, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, were members of Virginia’s slaveholder aristocracy. And even Adams, although not nearly as wealthy as the Virginians, was a member of New England’s elite. The extensive educations that children of the upper classes received helped prepare these men in their roles as visionaries of a new social order. One of the disadvantages faced by critics of the new order was that they were often unable to articulate their concerns in the same tone and language. That does not mean their concerns were not valid.

In the early 1820s, deference to pedigree began to wane in American society. Although social mobility was not universally available, enough men of modest ancestry were becoming successful in trades and businesses that the old elites had to make room for new elites. Established families retained their privileges (for example, the Cincinnati to this day is made up of the descendants of Revolutionary officers, not soldiers), but new voices demanded to be heard. A new type of deference took hold, responding to the will of the majority and not to a hereditary ruling class. The spirit of democratic reform became most evident in the widespread belief that all white men, regardless of whether they owned property, had the right to participate in elections.

Before the 1820s, many state constitutions had imposed property qualifications for voting as a means to keep democratic tendencies Federalists considered “mob-rule” in check. However, as Federalist ideals fell out of favor, ordinary men from the middle and lower classes increasingly questioned the idea that property ownership was the only indication of virtue. They argued for universal manhood suffrage, or voting rights for all white male adults. Some of these men had strong beliefs about issues that affected them, but many did not have the time, energy, or educations to debate political philosophy as the elite members of the founding generation had done. Political leaders began to focus more energy on crafting platforms and messages that would attract this new electorate. New states adopted constitutions that did not contain property qualifications for voting, a move designed to stimulate migration across their borders. Vermont and Kentucky, admitted to the Union in 1791 and 1792 respectively, granted voting rights to all white men regardless of whether they owned property or paid taxes. Ohio’s state constitution placed a minor taxpaying requirement on voters but otherwise embraced white male suffrage. Alabama, admitted to the Union in 1819, eliminated property qualifications for voting in its state constitution. Indiana (1816) and Illinois (1818) also extended the right to vote to white men regardless of property. Initially, the new state of Mississippi (1817) restricted voting to white male property holders, but in 1832 it eliminated this provision. Even old states reacted to the changing times. In Connecticut, Federalist power largely collapsed in 1818 when the state held a constitutional convention. The new constitution granted the right to vote to all white men who paid taxes or served in the militia. Similarly, New York amended its state constitution in 1821–1822 and removed the property qualifications for voting. However, expanded voting rights did not extend to women, Indians, or free blacks. Indeed, race and gender replaced property qualifications as the criterion for voting rights. New Jersey changed its laws to explicitly restrict the vote to white men only. Connecticut passed a law in 1814 taking the right to vote away from free black men and restricting suffrage to white men only. By the 1820s, 80 percent of the white male population could vote in New York State elections. No other state had expanded suffrage so dramatically. At the same time, however, New York effectively disenfranchised free black men in 1822 by requiring that “men of color” must possess property over the value of $250. Black men had had the right to vote under New York’s 1777 constitution; the new property qualification put voting out of their reach.

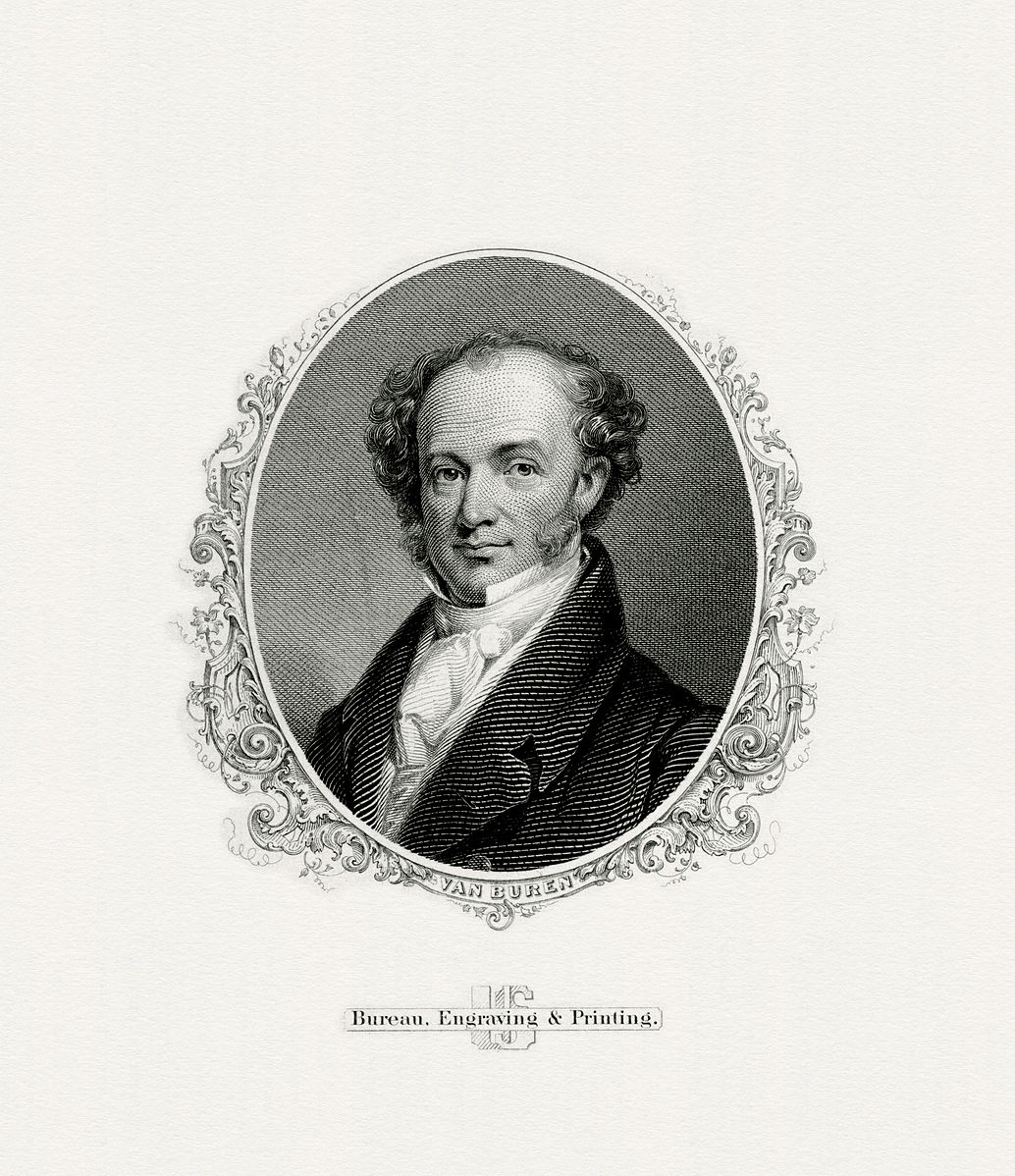

In addition to expanding white men’s right to vote, democratic currents also led to a new style of political party organization, most evident in New York State in the years after the War of 1812. Under the leadership of Martin Van Buren, New York’s “Bucktail” Republican faction gained political power by cultivating loyalty to the will of the majority rather than to an elite family or renowned figure. The Bucktails (named for the deer tails members wore on their hats, a symbol of membership in the Tammany Society) emphasized a pragmatic approach that seemed more focused on winning than on ideology. For example, at first the Bucktails opposed the Erie Canal project advocated by fellow Democratic-Republican DeWitt Clinton, but when the popularity of the massive transportation venture became clear, they supported it. DeWitt Clinton, nephew of longtime New York Governor (and Jefferson’s Vice President) George Clinton, was a three-term mayor if New York City and a senator before becoming governor of the state. Martin Van Buren, the Bucktail leader, was from an old Dutch family, but his father had been a tavern-owner rather than a major-general in the Continental Army like George Clinton. Van Buren would go on to be the only U.S. president for whom English was a second language. One of the Bucktails’ greatest achievements in New York was revising the state constitution in the 1820s. Under the original constitution, a Council of Appointments selected local officials such as sheriffs and county clerks. The Bucktails replaced this process with a system of direct elections, which meant thousands of jobs immediately became available to candidates who had the support of the majority. In practice, Van Buren’s party could nominate and support their own candidates based on their loyalty to the party. Van Buren created a political machine of disciplined party members who prized loyalty above all else, a harbinger of future patronage politics in the United States. This system of rewarding party loyalists is known as the spoils system from the expression, “To the victor belong the spoils”. Van Buren’s political machine helped radically transform New York politics.

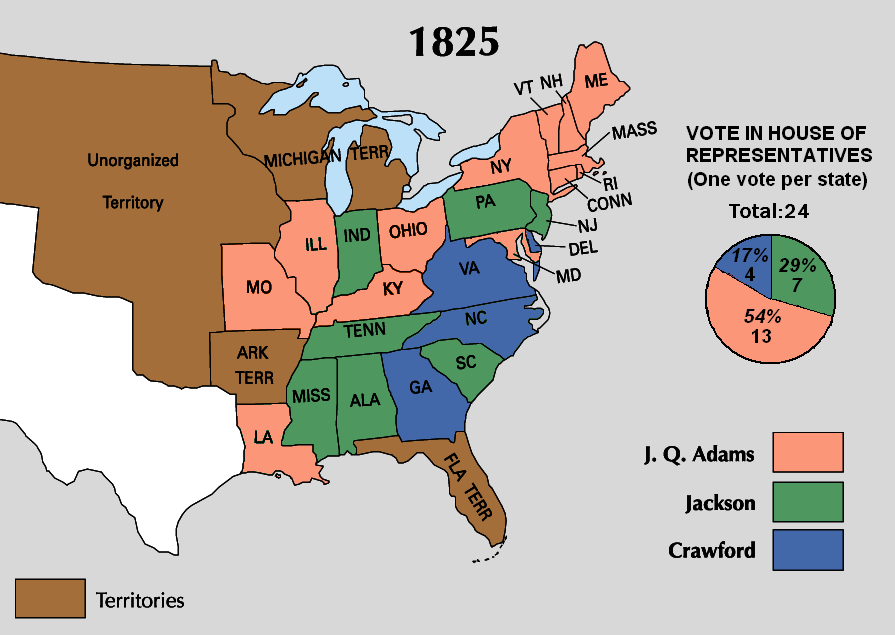

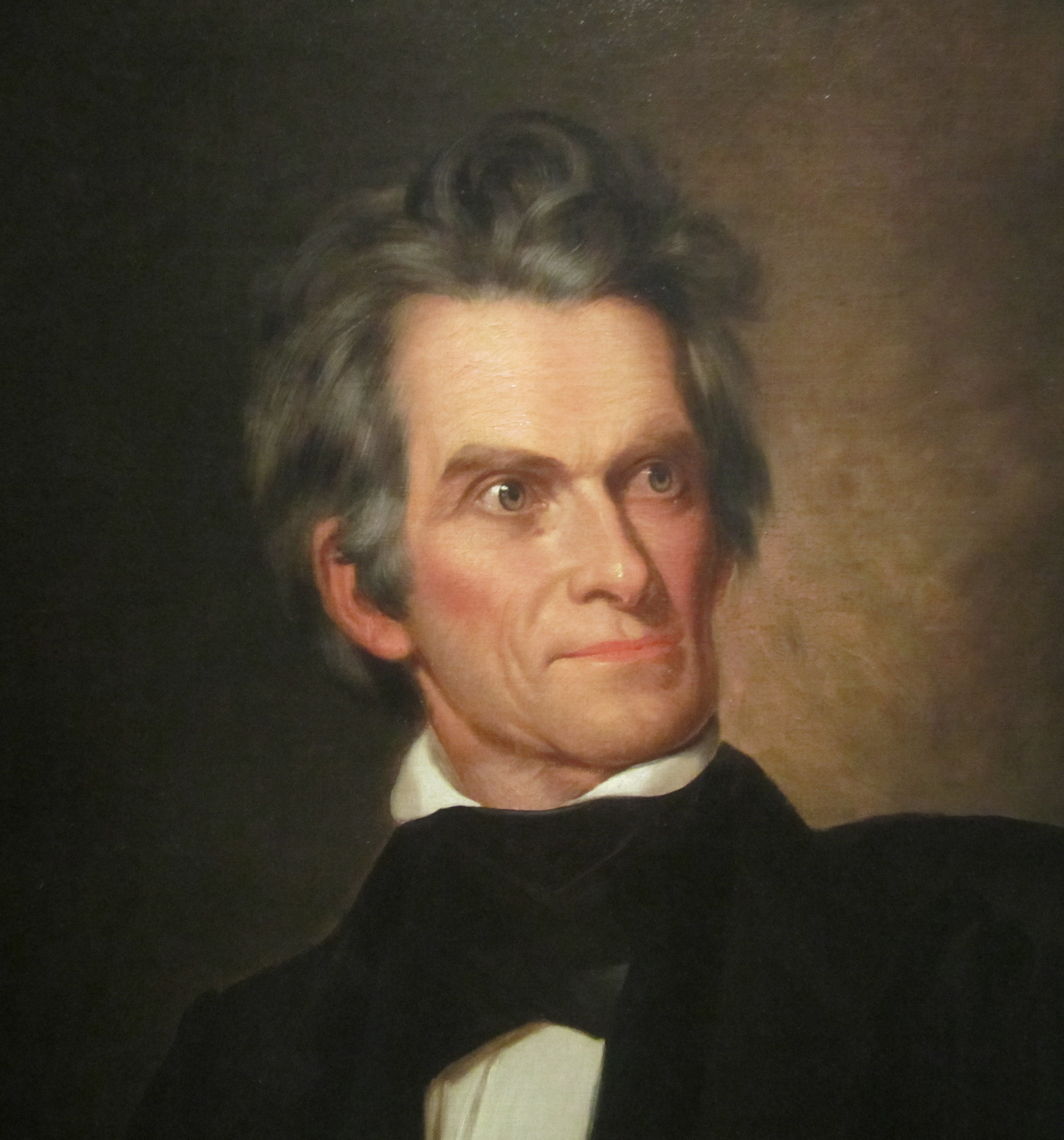

The presidential election of 1824 included tens of thousands of new voters and broke the older system of having congressional caucuses to determine who would run. The new voters had regional interests and voted them. For the first time, the popular vote mattered in a presidential election. Members of the Electoral College were chosen by popular vote in eighteen states, while the six remaining states used the older system in which state legislatures chose electors. With no caucus system, the presidential election of 1824 featured five candidates, all running as Democratic-Republicans. The crowded field included John Quincy Adams, the son of the second president, who had broken with the Federalists in the early 1800s and had served on important diplomatic missions including the mission to secure the peace treaty with Great Britain in 1814. John C. Calhoun from South Carolina had served as secretary of war and represented the slaveholding South. He dropped out of the presidential race to run for vice president. Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, hailed from Kentucky and represented the western states. He favored an active federal government committed to internal improvements such as roads and canals, to bolster national economic development and settlement of the West. William H. Crawford, a slaveholder from Georgia, suffered a stroke in 1823 that left him largely incapacitated, but he stayed in the race and had the backing of the New York machine headed by Van Buren. Andrew Jackson, the famed “hero of New Orleans,” rounded out the field. Jackson had very little formal education, but he was popular for his military victories in the War of 1812 and in wars against the Creek and the Seminole Indians. He had been elected to the Senate in 1823, and his popularity soared as pro-Jackson newspapers kept stories about the courage and daring of the Tennessee slaveholder constantly in front of voters. Results from the eighteen states where the popular vote determined the electoral vote gave Jackson the election, with 152,901 votes to Adams’s 114,023, Clay’s 47,217, and Crawford’s 46,979. The Electoral College, however, was another matter. Of the 261 electoral votes, Jackson needed 131 or better to win but secured only 99. Adams won 84, Crawford 41, and Clay 37. Because Jackson did not receive a majority vote from the Electoral College, the election was decided by the House of Representatives under the terms of the Twelfth Amendment. House Speaker Clay did not want to see his rival, Jackson, become president and worked the House to swing the vote to Adams. Clay’s efforts paid off and John Quincy Adams was certified by the House as the next president. Once in office, Adams appointed Henry Clay secretary of state. Jackson and his supporters cried foul. To them, the certification of Adams and his appointment of Clay as secretary of state reeked of anti-democratic corruption. John C. Calhoun labeled the whole affair a “corrupt bargain”. Everywhere, Jackson supporters vowed revenge against the anti-majoritarian result of 1824.

Secretary of State Clay championed what became known as the American System of high tariffs, a national bank, and federally sponsored internal improvements of canals and roads. Once in office, President Adams embraced Clay’s American System and proposed a national university and naval academy to train future leaders of the republic. The president’s opponents smelled elitism in these proposals and criticized what they viewed as the administration’s catering to a small privileged class at the expense of ordinary citizens. Clay also promoted internal transportation improvements. Using the proceeds from land sales in the West, Adams endorsed the creation of roads and canals to facilitate commerce and the advance of settlement in the West. Despite the successful opening of the highly profitable Erie Canal in 1825, many in Congress vigorously opposed federal funding of internal improvements, arguing that the Constitution did not give the federal government the power to fund these projects. However, in the end, Adams succeeded in extending the Cumberland Road into Ohio and broke ground for the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on July 4, 1828.

Tariffs, which both Clay and Adams promoted, had been used since the birth of the republic to raise money to operate the government and to advance domestic manufacturing by making imports more expensive. Congress had approved a revenue tariff in 1789 and Alexander Hamilton had proposed a protective tariff in 1790. Congress also passed tariff acts in 1816 and 1824. Clay spearheaded the drive for higher tariffs to bolster domestic manufacturing. In 1828 President Adams proposed a 50 percent tariff on imported goods. The tariff bill caused a fiery debate between supporters of states’ rights and those who wished to expand the power of the federal government. Opponents denounced the 1828 bill as the Tariff of Abominations, clear evidence that the federal government favored the manufacturing North over the agricultural South. The South, they argued, imported far more manufactured goods than the North, causing the tariff to fall most heavily on the southern states. The 1828 tariff generated additional fears among southerners. In particular, it suggested to them that the federal government could unilaterally take steps that hurt the South. This line of reasoning led some southerners to fear that the foundation of the southern social and economic life, slavery, could come under attack from a hostile northern majority in Congress. The spokesman for this southern view was President Adams’s vice president, John C. Calhoun.

During the 1800s, democratic reforms made steady progress with the abolition of property qualifications for voting and the birth of new forms of political party organization. The 1828 campaign pushed new democratic practices even further and highlighted the difference between the newly expanded electorate and the older, more exclusive Adams style of government. A slogan of the day, “Adams who can write/Jackson who can fight,” captured the contrast between the highly-educated but aristocratic Adams and the image of Jackson as a frontiersman and a war hero, with little formal education but great real-world experience. The 1828 campaign differed significantly from earlier presidential contests because the party organization that promoted Andrew Jackson reminded voters of the “corrupt bargain” of 1824. Jackson’s campaign framed his previous loss as the work of a small group of political elites deciding who would lead the nation in a self-serving manner and ignoring the will of the majority. From Tennessee, the Jackson campaign organized supporters around the nation through editorials in partisan newspapers heralding the “hero of New Orleans” and denouncing Adams. Though he did not wage an election campaign filled with public appearances, Jackson made a campaign speech in New Orleans on January 8, the anniversary of his defeat of the British in 1815. He also engaged in rounds of discussion with politicians who came to his home, the Hermitage, in Nashville.

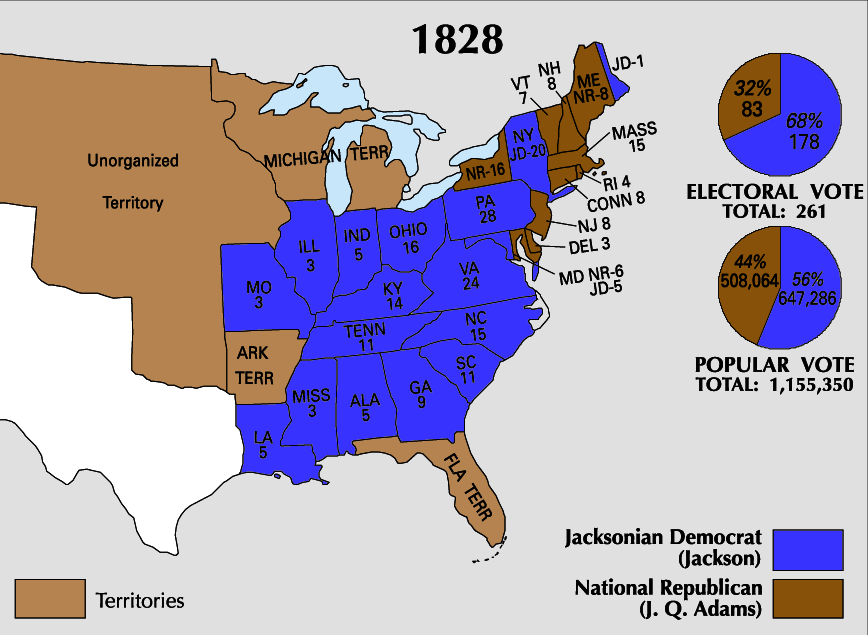

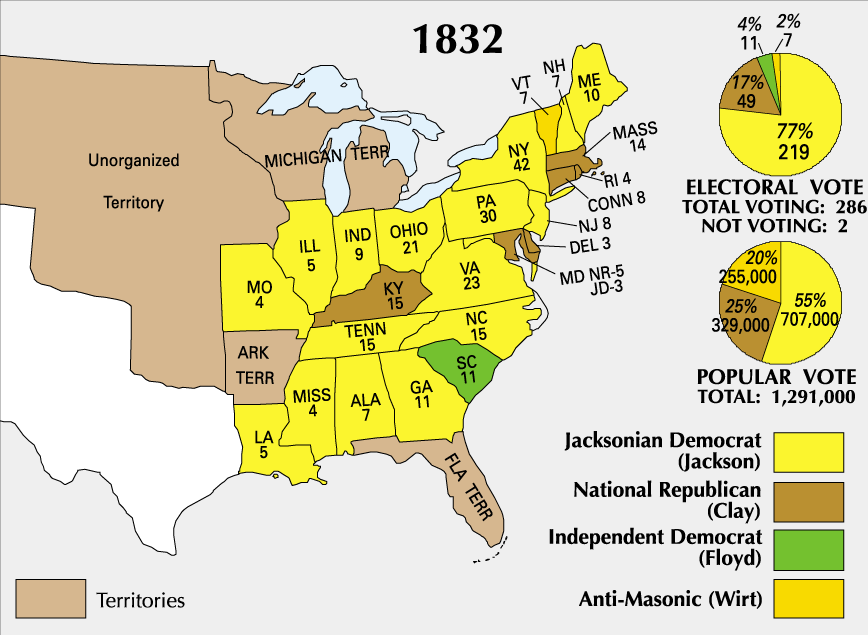

Jackson’s supporters worked to bring as many new voters as possible into the election. Local rallies, parades, and other rituals broadcast the message that Jackson stood for the common man against the corrupt elite backing Adams and Clay. Jackson’s supporters called themselves “The Democracy” or Democrats, to distinguish themselves from their Democratic-Republican opponents. Democratic organizations called Hickory Clubs, a tribute to Jackson’s nickname, Old Hickory, worked tirelessly to ensure his election. In November 1828, Jackson won an overwhelming victory over Adams, capturing 56 percent of the popular vote and 68 percent of the electoral vote. As in 1800, when Jefferson had won over the Federalist incumbent John Adams, the presidency passed peacefully to a new political party, the Democrats. The 1828 election was the climax of several decades of expanding democracy in the United States and the end of the older politics of deference.

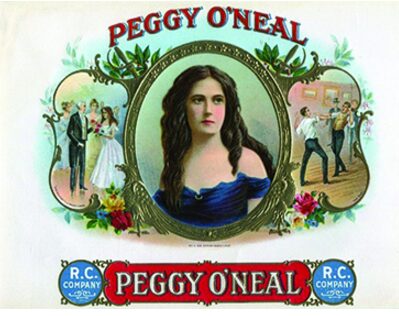

Amid accusations of widespread fraud including the disclosure that some $300,000 was missing from the Treasury Department, Jackson removed almost half of appointed federal government officers. Lucrative posts, such as postmaster and deputy postmaster, went to party loyalists, especially in places where Jackson’s support had been weakest, such as New England. Some Democratic newspaper editors who had supported Jackson during the campaign also gained public jobs. Jackson’s opponents complained of the spoils system that imitated the policies of Van Buren’s Bucktail Republican Party. The rewarding of party loyalists with government jobs resulted in spectacular instances of corruption. Perhaps the most notorious occurred in New York City, where a Jackson appointee made off with over $1 million. Such examples seemed proof positive that the Democrats were disregarding merit, education, and respectability not to respect the will of the majority, but to line their own pockets. In addition to dealing with rancor over office appointments, the Jackson administration became embroiled in a personal scandal known as the Petticoat Affair. This incident exacerbated the division between the president’s team and the insider class in the nation’s capital, who found the new arrivals from Tennessee lacking in decorum and propriety. At the center of the storm was Margaret “Peggy” O’Neal, a well-known socialite in Washington DC. Peggy O’Neal cut a striking figure and had social connections to the republic’s most powerful men. She married John Timberlake, a naval officer, and they had three children. Rumors abounded, however, about her involvement with John Eaton, a U.S. senator from Tennessee who had come to Washington in 1818.

Timberlake committed suicide in 1828, setting off a flurry of speculation that he had been distraught over his wife’s reputed infidelities. Eaton and Mrs. Timberlake married soon after, with the full approval of President Jackson. Many socialites snubbed the new Mrs. Eaton as a woman of low moral character, including Vice President John C. Calhoun’s wife, Floride. Calhoun fell out of favor with President Jackson, who defended Peggy Eaton and attacked those who would not socialize with her, declaring she was “as chaste as a virgin.” Jackson saw a parallel between Eaton’s treatment and that of his late wife, Rachel, who during the campaign had been subjected to vicious attacks on her reputation related to her first marriage, which had ended in divorce only after she had met Jackson. Martin Van Buren defended the Eatons and organized social gatherings with them, gaining influence with Jackson, who began relying on a group of informal advisers including Van Buren, dubbed the Kitchen Cabinet. This select group of presidential supporters highlights the importance of both party and personal loyalty to Jackson and the new Democratic Party.

By the early 1830s, the battle over the tariff took on new urgency as the price of cotton fell. In 1818, cotton had been thirty-one cents per pound but by 1831 it had sunk to eight cents per pound. While cotton production had soared and increased supply contributed to the decline in prices, many southerners blamed their economic problems on the tariff that raised the prices they had to pay for imported goods while their own income shrank. Resentment of the tariff was connected to the issue of slavery because the tariff demonstrated the power of the federal government to pass laws the states opposed. Some southerners feared the federal government would next move to the abolish slavery, which many northerners had opposed since the drafting of the Constitution. The theory of nullification provided wealthy slaveholders, who despite padding their numbers with the three fifths clause of the Constitution were becoming a minority in the United States, with an argument for resisting the national government if it acted contrary to their interests. James Hamilton, governor of South Carolina, denounced the “despotic majority that oppresses us.” Nullification also raised the specter of secession; aggrieved states at the mercy of an aggressive majority would be forced to leave the Union. Possibly because Calhoun supported nullification, South Carolina stood alone. President Jackson denied the nullifiers’ arguments. He and others, including former President James Madison, argued that the Constitution gave Congress the power to “lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises.” Jackson pledged to protect the Union against any who might try to tear it apart over the tariff issue. “The union shall be preserved,” he declared in 1830. The Tariff of 1832 lowered the rates on some imported goods, to calm southerners. It did not have the desired effect, however, and Calhoun’s nullifiers still claimed their right to override federal law. South Carolina passed an Ordinance of Nullification, declaring the 1828 and 1832 tariffs null and void in the Calhoun’s home state. Jackson responded, declaring in the December 1832 Nullification Proclamation that a state did not have the power to void a federal law.

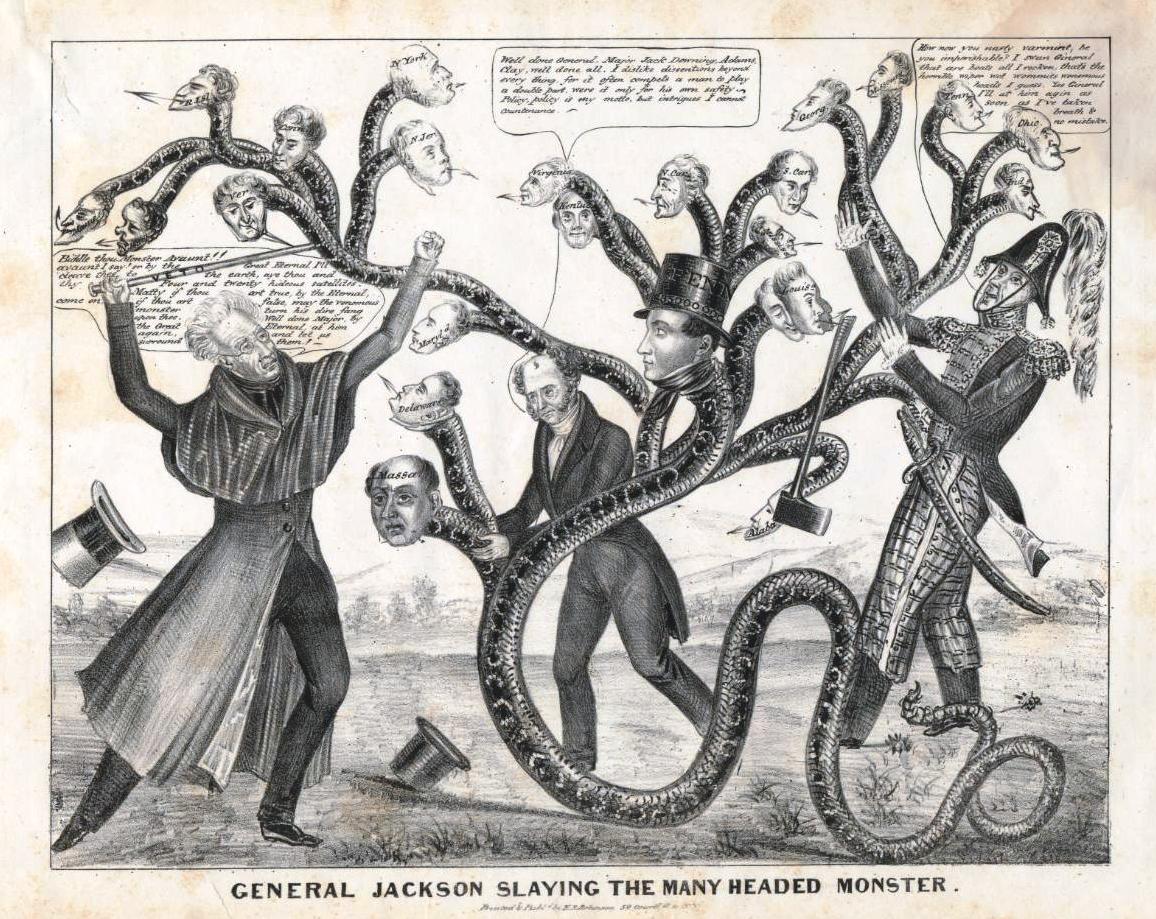

One of Jackson’s most notorious campaigns was his effort to end the national bank. Congress had established the Bank of the United States in 1791 as part of Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist financial program, but its twenty-year charter had expired in 1811. Congress, swayed by the Democratic-Republican majority’s hostility an institution catering to a wealthy elite, did not renew the bank’s charter. In its place, Congress approved a new national bank, the Second Bank of the United States, in 1816. It too had a twenty-year charter, set to expire in 1836. In the 1820s, the Second Bank of the United States moved into a magnificent new building in Philadelphia. However, despite Congress’s approval of the Second Bank, many people continued to view it as an anti-democratic tool of the wealthy. President Jackson had faced economic crises of his own during his days speculating in land, which had made him uneasy about paper money. To Jackson, hard currency, gold or silver, was a better alternative. The president also personally disliked the bank’s director, Nicholas Biddle, a wealthy Pennsylvanian whose family had emigrated to American with William Penn. A large part of the allure of mass democracy for politicians was the opportunity to capture and direct the anger and resentment of ordinary Americans against what they saw as the privileges of a few. Aristocrats like Biddle were easy targets for popular animosity, One of the leading opponents of the bank was Thomas Hart Benton, a senator from Missouri who declared that the bank served “to make the rich richer, and the poor poorer.” The self-important statements of Biddle, who claimed to have more power that President Jackson, seemed to confirm Benton’s claim.

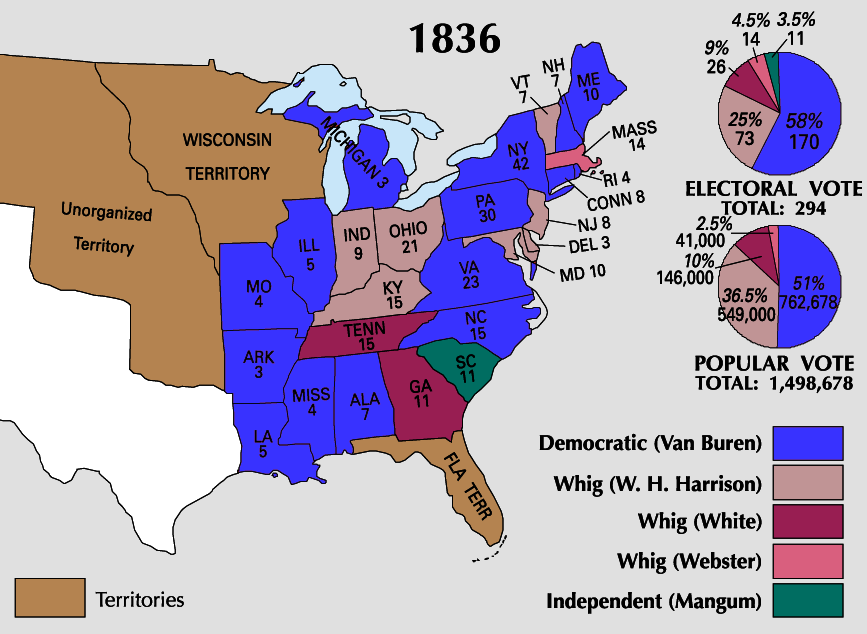

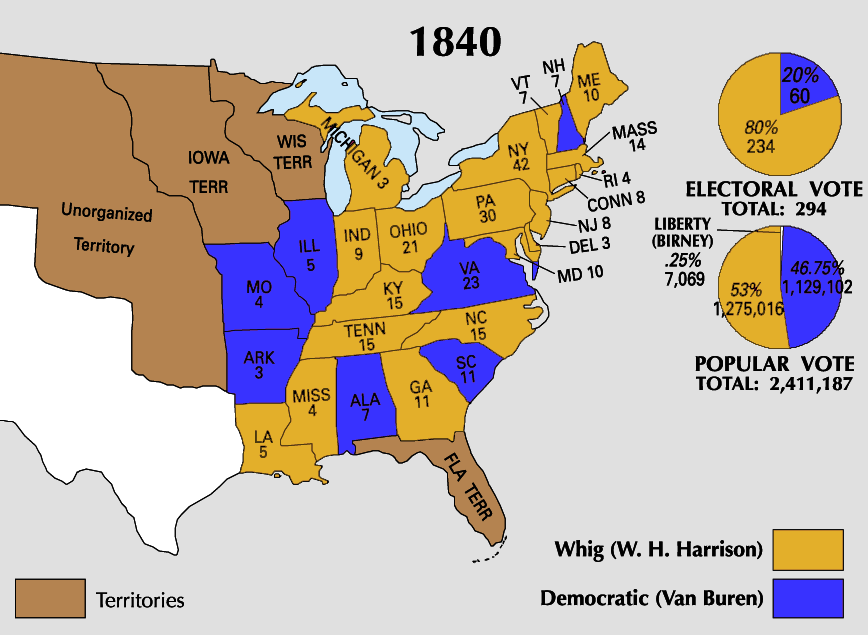

In his reelection campaign of 1832, Jackson replaced the nullification advocate John C. Calhoun with a new vice-presidential running-mate, Martin Van Buren. Jackson was opposed by Henry Clay, whose Anti-Jackson wing of the Democratic-Republican Party later took the name Whig in memory of the Englishmen who had opposed absolute monarchy in 1688 and the Patriots of the American Revolution. Jackson’s opponents hoped to use their support of the Second Bank to their advantage and pushed for legislation that would re-charter it even though its charter was not scheduled to expire until 1836. When the bill passed and came to President Jackson, he vetoed the measure. Jackson’s defeat of the Second Bank of the United States demonstrates the president’s ability to focus on the divisive issues that aroused the democratic majority. Jackson took advantage of people’s anger and distrust toward the bank, which stood as an emblem of special privilege and big government. He skillfully used that perception to present the charter veto as a struggle of ordinary people against an elite class who cared nothing for the public and pursued only their own selfish ends. As Jackson portrayed it, he fought for small government and ordinary Americans against what bank opponents called the “monster bank”. In the election of 1832, Jackson received nearly 55 percent of the popular vote against his opponent Clay. The veto was only part of Jackson’s war on the “monster bank.” In 1833, the president removed federal deposits from the bank and placed them in state banks. Biddle, the bank’s director, retaliated by restricting loans to the state banks, reducing the money supply. The financial turmoil increased when Jackson issued an executive order known as the Specie Circular, which required that western land sales be conducted using gold or silver only, rather than using paper banknotes. Jackson’s policies proved a disaster when the Bank of England, the source of much of the credit relied upon by American businesses, dramatically cut back on loans to the United States. Without the flow of credit from England, American depositors drained the gold and silver from their own domestic banks, making hard currency scarce. Adding to the economic distress of the late 1830s, cotton prices continued to plummet, contributing to a financial crisis called the Panic of 1837. The deep recession that followed it lasted to the mid-1840s and proved politically useful for Jackson’s opponents in the coming years. Martin Van Buren, elected president in 1836, would pay the price for Jackson’s hard-currency preferences.

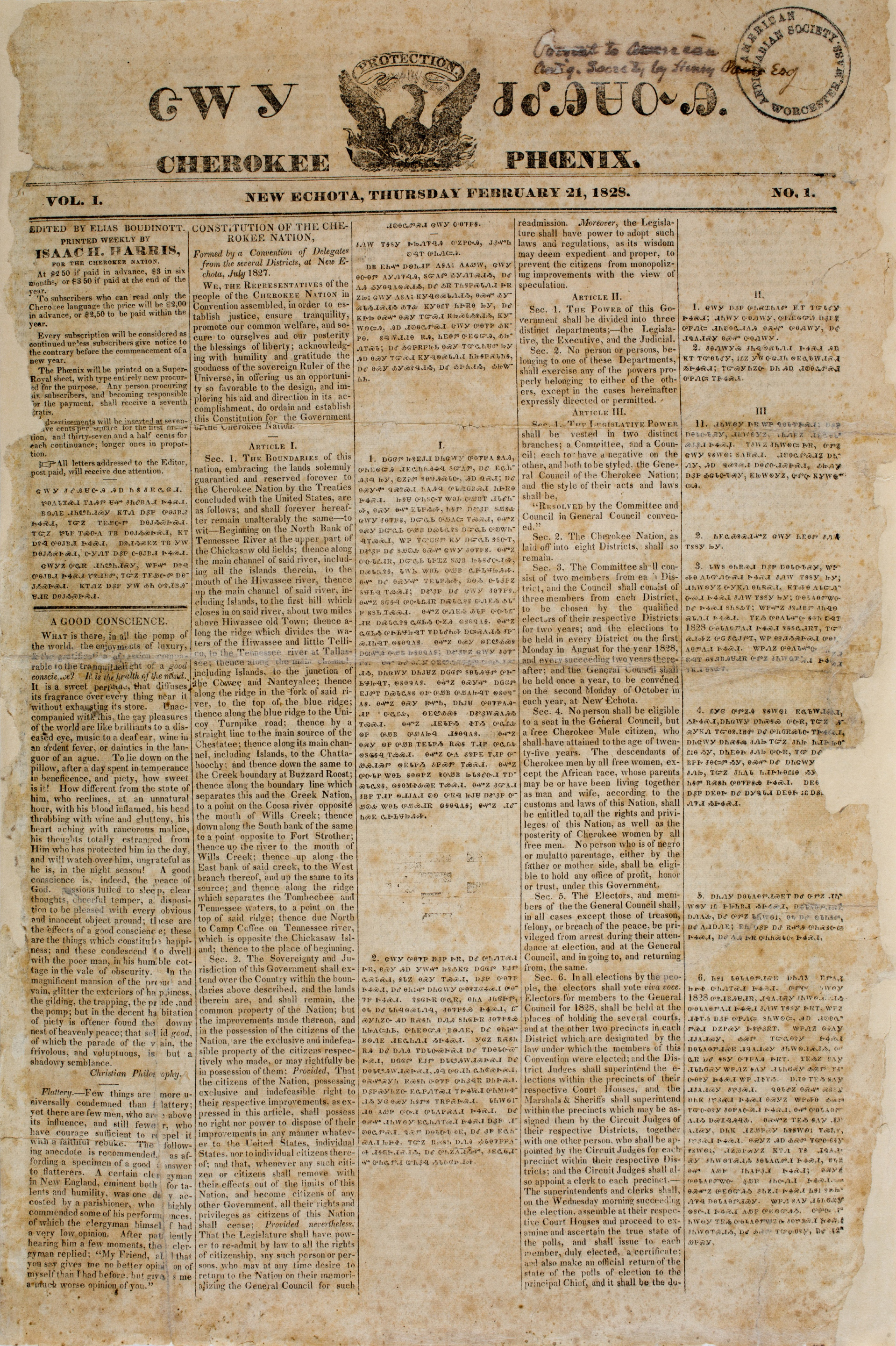

Pro-Jackson newspapers touted the president as a champion of opening land for white settlement and moving native inhabitants beyond the boundaries of “American civilization.” Jackson reflected majority opinion: most Americans believed Indians had no place in the white republic. Despite the efforts of many tribes to emulate the institutions and culture of the United States, Jackson’s animosity toward Indians ran deep. He had fought against the Creek in 1813 and against the Seminole in 1817, and his reputation and popularity rested largely on his firm commitment to remove Indians from states in the South. Democratic politicians and pro-Jackson newspapers portrayed the president as both a defender of the people and as a champion of western expansion. Popular culture in the first half of the nineteenth century reflected the aversion to Indians that was pervasive during the Age of Jackson. Jackson skillfully played upon this racial hatred to engage the United States in a policy of ethnic cleansing, eradicating the Indian presence from the land to make way for expanding white civilization. In his first message to Congress as president, Jackson had proclaimed that Indian groups living as sovereign entities within states presented a major problem for state sovereignty. This message referred directly to the situation in Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama, where the Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee tribal lands were obstacles to white settlement. These groups were known as the Five Civilized Tribes, because they had largely adopted Anglo-American culture, spoke English, practiced Christianity, and established a bicameral legislature and courts modeled after those of the states. Some Indians even held African slaves like their white counterparts. Whites especially resented the Cherokee in Georgia, where they coveted the tribe’s rich agricultural lands in the northern part of the state. The impulse to remove the Cherokee only increased when gold was discovered on their territory. Whites insisted the Cherokee and other native peoples could never be good citizens because of their savage ways, although the Cherokee had gone farther than any other Indians in adopting white culture. The efforts the Cherokee made to adopt white ways were of little consequence in an era when whites perceived all Indians as incapable of becoming full citizens of the republic.

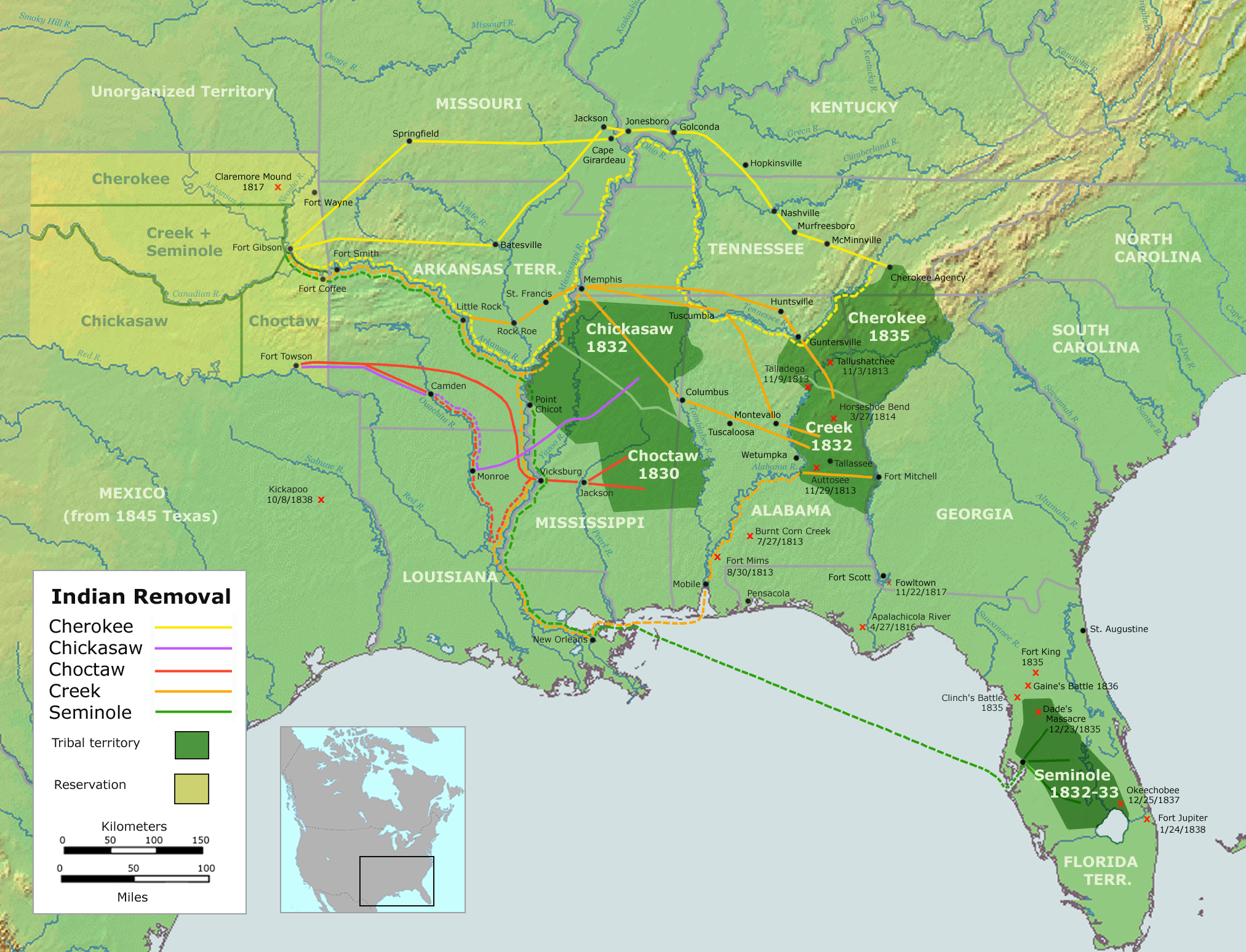

Jackson’s anti-Indian racism helped Congress to pass the 1830 Indian Removal Act which called for the removal of the Five Civilized Tribes from their homes in the southeastern United States to a western reservation that is now Oklahoma. Jackson, whose reputation as an Indian-fighter had helped him become president, declared in December 1830, “It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation. Two important tribes have accepted the provision made for their removal at the last session of Congress, and it is believed that their example will induce the remaining tribes also to seek the same obvious advantages.” The Cherokee decided to fight the federal law, however, and took their case to the Supreme Court. Their challenge had the support of anti-Jackson Congressmen including Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, and they retained the legal services of John Quincy Adams’s Attorney General, William Wirt. After Wirt lost his case, a second Supreme Court case called Worcester v. Georgia, asserted the rights of non-natives to live on Indian lands with native permission. Samuel Worcester was a Christian missionary and federal postmaster of New Echota, the capital of the Cherokee nation. A Congregationalist missionary, Worcester strongly opposed Indian removal. By living among the Cherokee, Worcester had violated a Georgia law forbidding whites from living in Indian territory. Worcester was arrested and found guilty along with nine others for violating the Georgia state law banning whites from living on Indian land. When the case of Worcester v. Georgia came before the Supreme Court in 1832, Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in favor of Worcester, finding that the Cherokee constituted “distinct political communities” with sovereign rights to their own territory. Hearing of the court’s decision, President Jackson wrote to a supporter in Tennessee, “the decision of the Supreme Court has fell still born, and they find that they cannot coerce Georgia to yield to its mandate.” Although he had previously disagreed with John C. Calhoun over the principle of nullification, Jackson was not above ignoring federal law when it suited him. The Supreme Court did not have any power to enforce its ruling in Worcester v. Georgia and it quickly became clear that the Cherokee would be forced to move. In a last attempt to defend their rights, most stayed on their land. The president sent in the U.S. military to remove the Indians and about sixteen thousand Cherokee were finally relocated to Oklahoma. This forced migration, known as the Trail of Tears, resulted in the deaths of as many as half the Cherokee along the way. The Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole peoples were also compelled to leave their homes. By the end of the 1830s nearly fifty thousand Indians had been removed from their southeastern homelands, opening 25 million acres for settlement and cotton plantations. The removal of the Five Civilized Tribes provides an example of the power of majority opinion in a democracy.

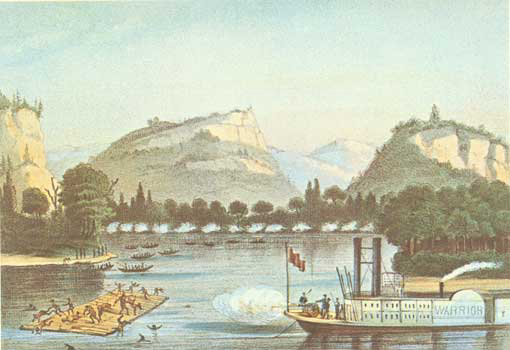

The U.S. government’s policy of forced removal led some Indians to actively resist. In 1832, the Fox and the Sauk, led by Sauk chief Makataimeshekiakiah (Black Hawk), moved back across the Mississippi River to reclaim their ancestral homeland in northern Illinois. Black Hawk’s War began when white settlers panicked at the return of the native peoples, and militias and federal troops quickly mobilized. At the Battle of Bad Axe U.S. troops killed over two hundred men, women, and children. About seventy white settlers and soldiers also lost their lives in the conflict. The war, which lasted only a matter of weeks, illustrates how much whites on the frontier hated and feared Indians during the Age of Jackson.

To some observers, the rise of Jacksonian Democracy in the United States raised troubling questions about the new power of the majority to silence minority opinion. Some worried that the rights of those who opposed the will of the majority would never be safe. Mass democracy also shaped political campaigns as never before. Perhaps the most insightful commentator on American democracy was the young French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville, whom the French government sent to the United States to report on American prison reforms. Tocqueville toured the U.S. and marveled at the spirit of democracy that pervaded American life. Tocqueville’s experience led him to believe that democracy was an unstoppable force that would one day overthrow monarchy around the world. He wrote and published his findings in 1835 and 1840 in a two-part work entitled Democracy in America. Analyzing the democratic revolution in the United States, Tocqueville wrote that the major benefit of democracy came in the form of equality before the law. The social revolution of democracy, however, carried negative consequences. Tocqueville described a new type of oppression, the tyranny of the majority, which overpowered the will of minorities and individuals and was, in his view, the main danger unleashed by democracy in the United States.

In this excerpt from Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville warns of the dangers of democracy when the majority will can turn to tyranny:

When an individual or a party is wronged in the United States, to whom can he apply for redress? If to public opinion, public opinion constitutes the majority; if to the legislature, it represents the majority, and implicitly obeys its injunctions; if to the executive power, it is appointed by the majority, and remains a passive tool in its hands; the public troops consist of the majority under arms; the jury is the majority invested with the right of hearing judicial cases; and in certain States even the judges are elected by the majority. However iniquitous or absurd the evil of which you complain may be, you must submit to it as well as you can.

The authority of a king is purely physical, and it controls the actions of the subject without subduing his private will; but the majority possesses a power which is physical and moral at the same time; it acts upon the will as well as upon the actions of men, and it represses not only all contest, but all controversy. I know no country in which there is so little true independence of mind and freedom of discussion as in America.

Primary Source Readings:

Black scientist Benjamin Banneker demonstrates Black intelligence to Thomas Jefferson, 1791

Benjamin Banneker, a free Black American and largely self-taught astronomer and mathematician, wrote Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State, on August 19, 1791. Banneker included this letter, as well as Jefferson’s short reply, in several of the first editions of his almanacs in part because he hoped it would dispel the widespread assumption that Jefferson perpetuated in his Notes on the State of Virginia that Black people were incapable of intellectual achievement.

Creek headman Alexander McGillivray (Hoboi-Hili-Miko) seeks to build an alliance with Spain, 1785

Native peoples had long employed strategies of playing Europeans off against each other to maintain their independence and neutrality. As early as 1785, the Creek headman Alexander McGillivray (Hoboi-Hili-Miko) saw the threat the expansionist Americans placed on Native peoples and the inability of a weak United States government to restrain their citizens from encroaching on Native lands. McGillivray sought the aid and protection of the Spanish in order to maintain the supply of trade goods into Creek country and counter the Americans.

Tecumseh Calls for Native American resistance, 1810

Like Pontiac before him, Tecumseh articulated a spiritual message of Native American unity and resistance. In this document, he acknowledges his Shawnee heritage, but appeals to a larger community of “red men,” who he describes as “once a happy race, since made miserable by the white people.” This document reveals not only Tecumseh’s message of resistance, but it also shows that Anglo-American understandings of race had spread to Native Americans as well.

Congress debates going to war, 1811

Americans were not united in their support for the War of 1812. In these two documents we hear from members of congress as they debate whether or not America should go to war against Great Britain.

Media Attributions

- Brooklyn_Museum_-_Portrait_of_John_Adams_-_Samuel_Finley_Breese_Morse_-_overall © Samuel F.B Morse is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1193px-Preparation_for_War_to_defend_Commerce_Birch’s_Views_Plate_29 © W. Birch & Son is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Toussaint_L’Ouverture © Chez Jean rue Jean de Beauvais is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Lyon-griswold-brawl © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ElectoralCollege1800-Large © Red Devil 666 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Official_Presidential_portrait_of_Thomas_Jefferson_(by_Rembrandt_Peale,_1800) © Rembrandt Peale is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Burning_of_the_uss_philadelphia © Edward Moran is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Louisiana._LOC_2001620468 (1) © Arrowsmith and Lewis is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ElectoralCollege1804-Large © Red Devil 666 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Columbia-John-Bull-Napoleon-ca1813 © William Charles is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ElectoralCollege1808-Large © Red Devil 666 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Death_of_Tecumseh_by_Currier_&_Ives © Currier and Ives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_President’s_House_by_George_Munger,_1814-1815_-_Crop © George Munger is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1280px-Battle_of_New_Orleans © Edward Percy Moran is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ElectoralCollege1816-Large © Red Devil 666 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Parson Weems’ Fable © Grant Wood is licensed under a Public Domain license

- David_Crockett © cliff1066 is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1034px-VAN_BUREN,_Martin-President_(BEP_engraved_portrait) © Bureau of Engraving is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Election_in_House1824-Large © Fishal is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1280px-Erie_Canal,_Lockport_New_York,_c.1855 © Herrmann J. Meyer is licensed under a Public Domain license

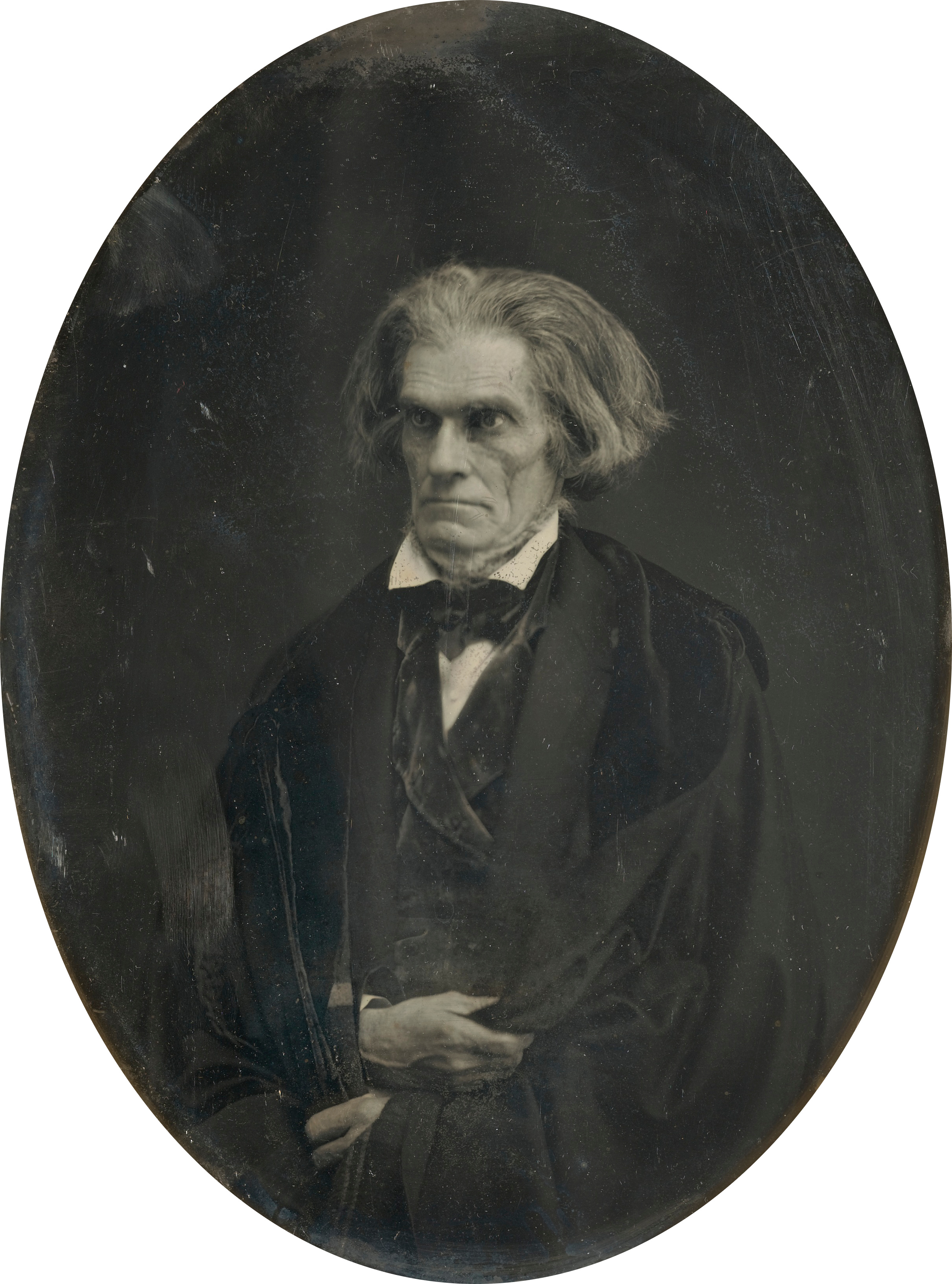

- John_C._Calhoun_at_National_Portrait_Gallery_IMG_4384 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2560px-JACKSON,_Andrew-President_(BEP_engraved_portrait) © Bureau of Engraving adapted by Godot13 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1828_Electoral_Map © Tallicfan20 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Peggy-O’Neal_image © RC Cigar Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- John_C._Calhoun_by_Mathew_Brady © Mathew Brady is licensed under a Public Domain license

- General_Jackson_Slaying_the_Many_Headed_Monster_crop © H.R. Robinson

- ElectoralCollege1832-Large © Red Devil 666 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cherokee_Phoenix_first_issue (1) © Elias Boudinot and Isaac H. Harris is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Trails_of_Tears_en (1) © Nikater is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1832_Battle_of_Bad_Axe_and_steamboat_Warrior © Amz and Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1836_Electoral_Map © Tallicfan20 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Alexis_de_tocqueville © Theodore Chasseriau is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1840_Electoral_Map © Tallicfan20 is licensed under a Public Domain license