10 Civil War

Before Abraham Lincoln took office, John Crittenden, a senator from Kentucky who had helped form the Constitutional Union Party during the 1860 presidential election, attempted to defuse the explosive situation by offering six constitutional amendments and a series of resolutions, known as the Crittenden Compromise. Crittenden’s goal was to keep the South from seceding, and his strategy was to transform the Constitution to explicitly protect slavery forever. Specifically, Crittenden proposed an amendment that would restore the 36°30′ line from the Missouri Compromise and extend it all the way to the Pacific Ocean, protecting and ensuring slavery south of the line while prohibiting it north of the line. He further proposed an amendment that would prohibit Congress from abolishing slavery anywhere it already existed or from interfering with the interstate slave trade. In an attempt to protect slavery in southern states, Crittenden proposed to introduce it in California, which had been a free state for ten years.

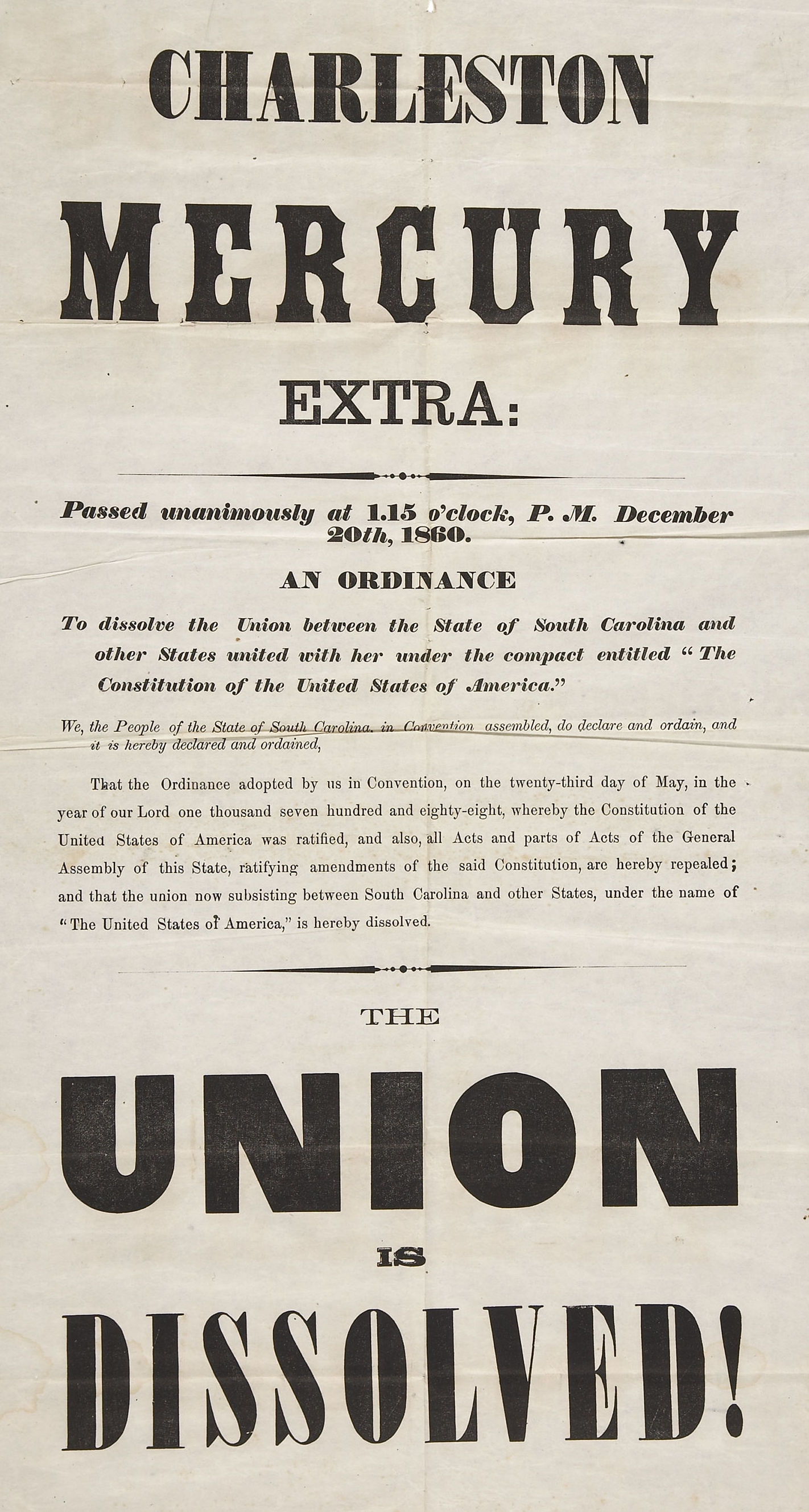

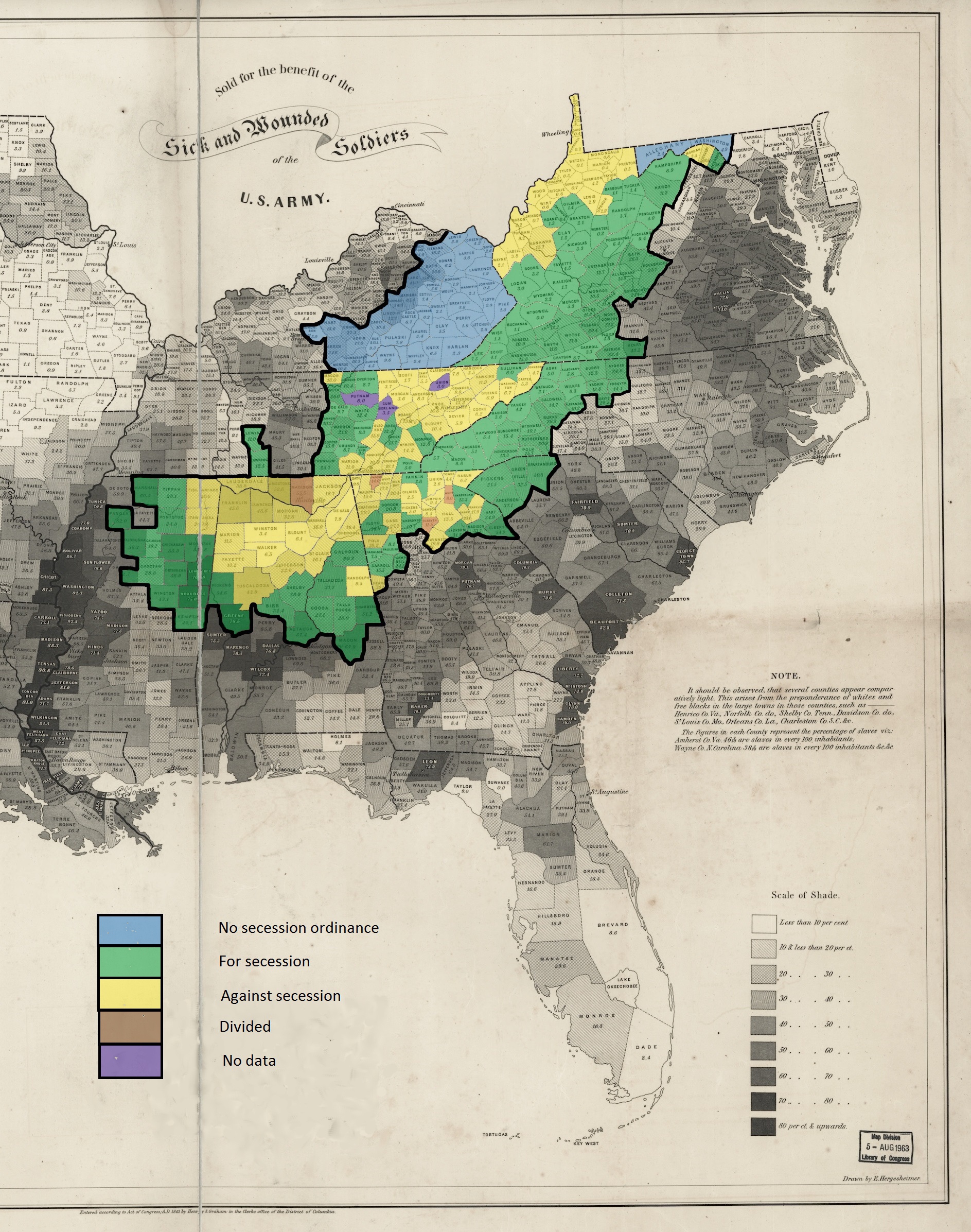

Republicans, including President-elect Lincoln, rejected Crittenden’s proposals because they ran counter to the party’s goal of keeping slavery out of the territories. Southern states rejected Crittenden’s compromise because it would prevent slaveholders from taking their human chattel north of the 36°30′ line. On December 20, 1860, only a few days after Crittenden’s proposal was introduced in Congress, South Carolina began the march towards war when it seceded from the United States. Mississippi, Florida, and Alabama followed South Carolina and seceded before the U.S. Senate rejected Crittenden’s proposal on January 16, 1861. Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas joined them in rapid succession on January 19, January 26, and February 1, respectively. Many cases secessions occurred after extremely divided conventions and popular votes. The people of the South were not unanimous in their support of secession, but as always, the planter class had its way.

The seven Deep South states that seceded quickly formed a new government. In the opinion of many Southern politicians, the federal Constitution that united the states as one nation was a contract by which individual states had agreed to be bound. However, they maintained, the states had not sacrificed their autonomy and could withdraw their consent to be controlled by the federal government. Southerners justified their actions with arguments about nullification, the nature of the Constitution, and the social contract theory of government that had influenced the founders of the American Republic.

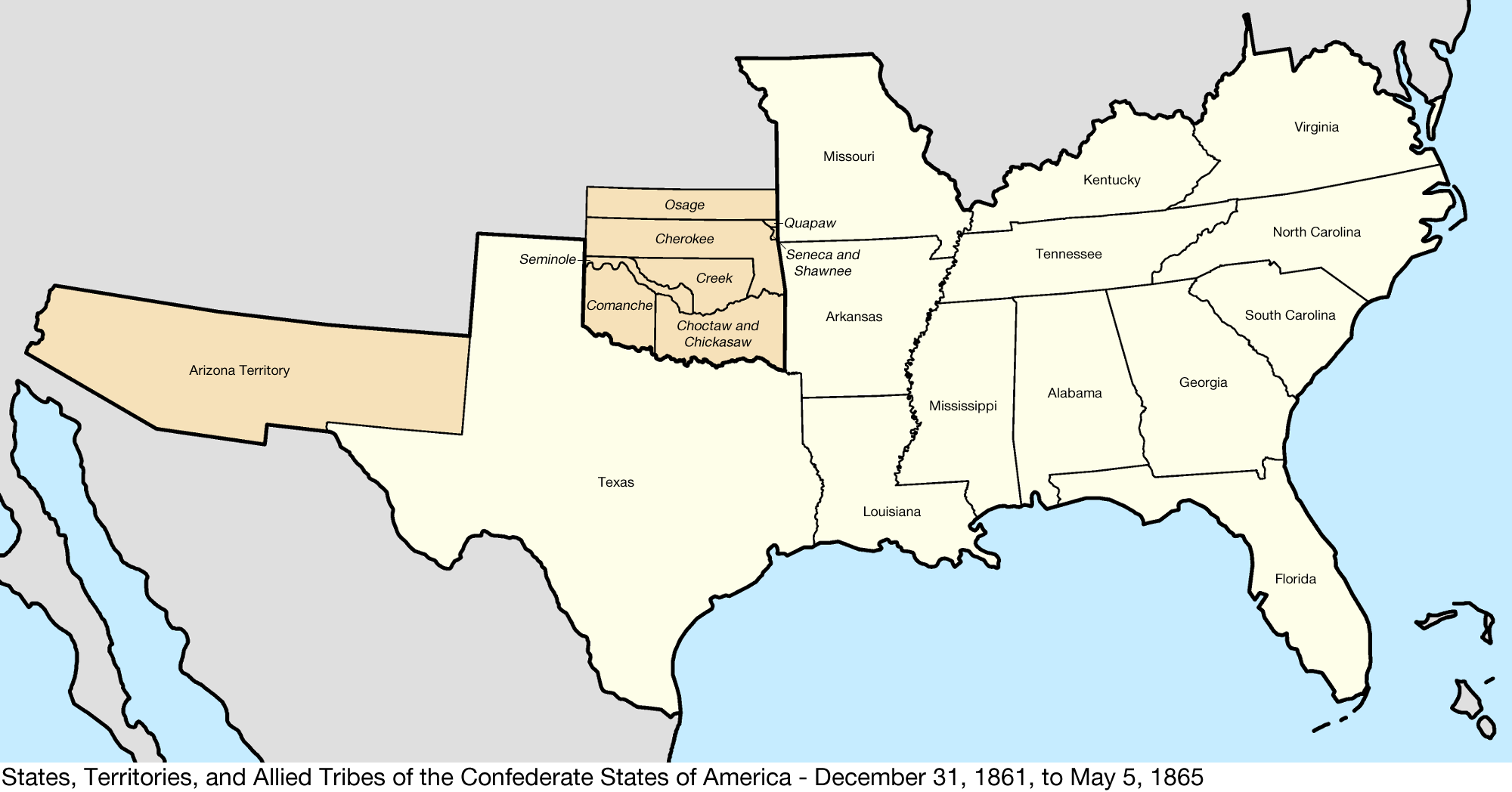

The new nation formed by these men would not be a federal union, but a confederation like the one that had preceded the Constitution. Individual member states agreed to unite under a central government for some purposes, such as defense, but to retain autonomy in other areas of government. In this way, states could protect themselves, and slavery, from interference by what they perceived to be an overbearing central government. The constitution of the Confederate States of America (CSA), drafted at a convention in Montgomery Alabama in February 1861, closely followed the 1787 US Constitution. The only real difference between the two documents concerned slavery. The Confederate Constitution declared that the new nation existed to defend and perpetuate racial slavery, and the leadership of the slaveholding class. Specifically, the constitution protected the interstate slave trade and guaranteed that slavery would exist in any new territory gained by the Confederacy. Article One, Section Nine, declared that “No . . . law impairing or denying the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.” Beyond its focus on slavery, the Confederate Constitution allowed for a Congress composed of two chambers, a judicial branch, and an executive branch with a president to serve for six years.

By the time Lincoln reached Washington DC in February 1861, the CSA had already been established. The new president confronted an unprecedented crisis. A conference held that month with delegates from the Southern states failed to secure a promise of peace or to restore the Union. On March 4 1861, the newly-inaugurated president repeated his views on slavery: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” His recognition of slavery in the South did nothing to mollify slaveholders, however, because Lincoln also pledged to keep slavery from expanding into the new western territories. Furthermore, in his inaugural address, Lincoln made clear his commitment to maintaining federal power against the secessionists working to destroy it. Lincoln declared that the Union could not be dissolved by individual state actions, and that secession was unconstitutional.

President Lincoln made it clear to Southern secessionists that he would fight to maintain federal property and to keep the Union intact. Other politicians, however, still hoped to avoid the use of force to resolve the crisis. In February 1861, in an effort to entice the rebellious states to return to the Union without resorting to force, Thomas Corwin, a representative from Ohio, introduced a proposal to amend the Constitution to make it impossible for Congress to pass any law abolishing slavery. The proposal passed the House on February 28, 1861, and the Senate passed the proposal on March 2, 1861. It was then sent to the states to be ratified. In his inaugural address, Lincoln stated that he had no objection to the amendment, and his predecessor James Buchanan had supported it. By the time of Lincoln’s inauguration, however, seven states had already left the Union. Of the remaining states, Ohio ratified the amendment in 1861, and Maryland and Illinois did so in 1862. Despite this effort at reconciliation, the Confederate states made no move to suggest they would be willing to return to the Union.

Indeed, by the time of the Corwin amendment’s passage through Congress, Confederate forces in the Deep South had already begun to take over federal forts. Fort Sumter, in the harbor of Charleston South Carolina, had a Union garrison of fewer than one hundred soldiers and officers, making it a vulnerable target for the Confederacy. Jefferson Davis was urged to take Fort Sumter and demonstrate Confederate resolve but delayed giving the order to attack. Some southerners hoped that the Confederacy would gain foreign recognition, especially from Great Britain, by taking the fort in the South’s most important Atlantic port. Local merchants refused to sell food to the fort’s Union soldiers, and by mid-April the garrison’s supplies began to run out. President Lincoln warned Confederate leaders that he planned to resupply the Union forces. His strategy insured that the decision to start a war would rest squarely on the Confederates rather than the Union. On April 12 1861, Confederate forces in Charleston began a bombardment of Fort Sumter. Two days later, the Union soldiers there surrendered.

The attack on Fort Sumter was effectively a declaration of war by the Confederacy on the United States, and on April 15 1861 Lincoln called upon loyal states to supply troops to defeat the rebellion and regain Fort Sumter. Faced with the need to choose between the Confederacy and the Union, border states and those of the Upper South, which earlier had been reluctant to dissolve their ties with the United States, were inspired to take action. They quickly voted for secession. A convention in Virginia that had already been assembled to consider the question of secession voted to join the Confederacy on April 17, two days after Lincoln called for troops. Arkansas left the Union on May 6 and Tennessee one day later. North Carolina followed on May 20.

Not all residents of the border states wished to join the Confederacy, however. Pro-Union feelings remained strong in Tennessee, especially in the eastern part of the state where slaves were fewer. The state of Virginia literally was split on the issue of secession. Residents in the north and west of the state, where few slaveholders resided, rejected secession and united to form West Virginia, which entered the Union as a free state in 1863. The rest of Virginia, including the historic lands along the Chesapeake Bay that were home to such early American settlements as Jamestown and Williamsburg, joined the Confederacy. The addition of this area gave the Confederacy even greater hope and brought General Robert E. Lee, the best military commander of the day, to their side. The secession of Virginia also brought Washington DC perilously close to the Confederacy. Concern that the border state of Maryland would also join the CSA, trapping the U.S. capital within Confederate territories, plagued Lincoln.

The Confederacy also gained the backing of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee tribes that had been removed from Georgia in the 1830s to the Indian Territory. The tribes supported slavery and many members owned slaves. These Indian slaveholders, who had been forced from their lands during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, now found common cause with white slaveholders. The CSA even allowed them to send delegates to the Confederate Congress.

While most slaveholding states joined the Confederacy, four crucial slave states remained in the Union. Delaware, a slave state despite its tiny slave population, never voted to secede. Maryland, despite deep divisions, remained in the Union as well. Missouri became the site of vicious fighting and the home of pro-Confederate guerrillas but never joined the Confederacy. Kentucky declared itself neutral, although that did little to stop the fighting that occurred within the state. These four states deprived the Confederacy of key resources and soldiers.

After the fall of Fort Sumter on April 15 1861, Lincoln called for seventy-five thousand volunteers from state militias to join federal forces. His plan was a ninety-day campaign to put down the Southern rebellion. The response from state militias was overwhelming, and the number of Northern volunteers exceeded the requisition. Lincoln began a naval blockade of the South, and the Confederacy responded to the blockade by declaring that a state of war existed with the United States. Although the attack on Fort Sumpter had left little doubt, this official pronouncement confirmed the beginning of the Civil War. Men rushed to enlist, to defend the new Confederate nation.

Many believed that a single, heroic battle would decide the contest. Northerners hoped that most Southerners would not actually fire on the American flag. Lincoln and his military leaders hoped a quick blow to the South, especially the capture of the Confederacy’s new capital of Richmond, Virginia, might end the rebellion before it went any further. On July 21 1861, the two armies met near Manassas, Virginia, along Bull Run Creek, only thirty miles from Washington, DC. Expectation of a climactic Union victory caused many Washington socialites and politicians to bring picnic lunches to a nearby area, hoping to witness a historic defeat of the rebellion. About sixty thousand troops assembled, most of whom had never seen combat, and each side sent eighteen thousand into battle. The Union forces attacked first and were pushed back. Confederate forces then carried the day, sending the Union soldiers and Washington onlookers scrambling back from Virginia and destroying Union hopes of a quick, decisive victory. Instead, the war would drag on for four long, deadly years.

The Confederates had the advantage of being able to wage a defensive war, rather than an offensive one. They had to defend their new boundaries, but they did not have to be the aggressors against the Union. The war would be fought primarily in the South, which gave the Confederates the advantages of the knowledge of the terrain and the support of the civilian population. Further, the vast coastline from Texas to Virginia offered ample opportunities to evade the Union blockade. And with the addition of the Upper South states, especially Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas, the Confederacy gained a much larger share of natural resources and industrial might than the Deep South states could muster.

Still, the Confederacy had disadvantages. The South’s economy depended heavily on the export of cotton, which Senator Hammond had declared King. With the naval blockade, the flow of cotton to England, the South’s main remaining market after the loss of New England’s textile mills, came to an end. The blockade also made it difficult to import manufactured goods. Although the Upper South added some industrial capability to the Confederacy, the South lacked industry or railroad infrastructure comparable to the North. The Confederate government began printing paper money, leading to runaway inflation. The advantage that came from fighting on home territory quickly turned to a disadvantage when Confederate armies were defeated and Union forces destroyed Southern farms and towns and turned Southern civilians into refugees. Finally, the population of the South stood at fewer than nine million people, of whom nearly half were black slaves, compared to a Northern population of over twenty million. These limited numbers became a major factor as the war dragged on and the death toll rose.

The North’s greater population, industrial capabilities, and extensive railroad grid made it far better at mobilizing men and supplies for the war effort. The industrial and transportation revolutions had transformed the North. The California gold fields contributed $186 million to the Union treasury, and farms in New England, the Mid-Atlantic, the Old Northwest, and the prairie states supplied Northern civilians and Union troops with abundant food throughout the war. Food shortages and hungry civilians were common in the South, where the best land had been devoted to raising cotton using the labor of slaves rather than to allowing free farmers to produce food.

Unlike the South, however, which could hunker down to defend itself and needed to maintain relatively short supply lines, the North had to invade and conquer a vast region. Union armies established long supply lines, and Union soldiers were forced to fight on unfamiliar ground and contend with a hostile civilian population. Then, to restore the Union after defeating Southern forces, the United States would need to pacify a conquered population in an area of over half a million square miles with nearly nine million residents. Although it had better resources and a larger population, the Union faced a daunting task against the well-positioned Confederacy.

General Lee tried to capitalize on the Union’s failure by moving his forces into northern Virginia. At the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Confederates again defeated the Union forces. Lee then pressed into Maryland, where his troops met the much larger Union forces near Sharpsburg, at Antietam Creek. A one-day battle on September 17 1862 saw a tremendous loss of life. At least eight thousand soldiers were killed or wounded, more than on any other single day of combat. Once again McClellan mistakenly held back a significant portion of his forces. Lee withdrew from the field first, but McClellan, fearing he was outnumbered, refused to pursue him. Antietam made it clear to Lincoln that McClellan would never win the war, and Lincoln also personally disliked McClellan, who had referred to the president as a “baboon” and a “gorilla,” and constantly criticized his decisions. Lincoln chose General Ambrose E. Burnside to replace McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac, but Burnside’s efforts to push into Virginia failed in December 1862 when Confederates held their position at Fredericksburg. Burnside’s failure led Lincoln to make another change in leadership, and Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker took over command of the Army of the Potomac in January 1863.

General Ulysses S. Grant, operating in Kentucky, Tennessee, and the Mississippi River Valley, was more successful. In the western campaign, the goal of both the Union and the Confederacy was to gain control of the major rivers in the west, especially the Mississippi. If the Union could control the Mississippi, the Confederacy would be split in two. The fighting in this campaign initially centered in Tennessee, where Grant’s Union forces pushed Confederate troops back and gained control of the state. The major battle in the western theater took place at Pittsburgh Landing, Tennessee, on April 6 and 7, 1862. Grant’s army was camped on the west side of the Tennessee River near a small log church called Shiloh, which gave the battle its name. On Sunday morning, April 6, Confederate forces under General Albert Sidney Johnston attacked Grant’s encampment with the goal of separating them from their supply line on the Tennessee River and driving them into the swamps on the river’s western side, where they could be destroyed. Unfortunately for the Confederates, Johnston was killed on the afternoon of the first day. Leadership of the Southern forces fell to General P. G. T. Beauregard, who ordered an assault at the end of that day. This assault was so desperate that one of the two attacking columns did not even have ammunition. Heavily reinforced Union forces counterattacked the next day, and the Confederate forces were routed. Grant had maintained the Union foothold in the western part of the Confederacy. The North could now concentrate on its efforts to gain control of the Mississippi River, splitting the Confederacy in two and depriving it of its most important water route.

The Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia, exercised sweeping powers to ensure victory, in stark contradiction to the states’ rights sentiments held by many Southern leaders. The initial popular outburst of enthusiasm for war in the Confederacy waned, and the CSA instituted a military draft in April 1862. Under the terms of the draft, all men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five would serve three years. The draft had an unequal effect on men of different classes. One loophole permitted men to hire substitutes instead of serving in the Confederate army. This provision favored the wealthy and led to resentment and resistance. Exercising its power over the states, the Confederate Congress denied state efforts to circumvent the draft.

The Confederate government also took over the South’s economy. Over the objections of slaveholders, it impressed slaves and forced them to work on fortifications and rail lines. Concerned about resistance to government measures, in 1862 the Confederate Congress gave President Davis the power to suspend habeas corpus, the right enshrined in British and American traditions of liberty. With a stated goal of bolstering national security in the fledgling republic, the Confederacy declared it could arrest and detain indefinitely any suspected enemy without giving a reason. This growth of the Confederate central government stood as a glaring contradiction to the earlier states’ rights argument of pro-Confederate advocates.

The war was costing the new nation dearly, but the Confederate Congress obeyed the demands of wealthy plantation owners and refused to place a tax on slaves or cotton, despite the Confederacy’s desperate need for the revenue that such a tax would have raised. Instead, the Confederacy drafted a taxation plan that kept the Southern elite happy and resorted to printing immense amounts of paper money, which quickly led to runaway inflation. Food prices soared and poor, white Southerners faced starvation. In April 1863, thousands of hungry people rioted in Richmond, Virginia. Many of the rioters were mothers who could not feed their children. The riot ended only when President Davis threatened to have Confederate forces open fire on the crowds.

One of the reasons that the Confederacy was so economically devastated was its self-satisfied certainty that cotton sales would continue during the war. The Confederate government also hoped that Great Britain and France would grant the CSA loans to ensure the continued flow of King Cotton. But Great Britain did not wish to risk war with the United States, which would have meant the invasion of Canada. The United States was also a major source of grain for Britain and an important purchaser of British goods. Britain found alternate sources of cotton in India and Egypt, leaving the South without the income or alliance it had anticipated.

Dissent within the Confederacy also affected the South’s ability to fight the war. Governors in the Confederate states often proved reluctant to provide supplies or troops for the use of the Confederate government. Even Jefferson Davis’s vice president Alexander Stephens opposed conscription, seizure of slaves to work for the Confederacy, and suspension of habeas corpus. Class divisions also divided Confederates. Poor whites resented the ability of wealthy slaveholders to excuse themselves from military service. Racial tensions plagued the South as well. On those occasions when free blacks volunteered to serve in the Confederate army, they were turned away, and enslaved African Americans were regarded with fear and suspicion, as whites grew paranoid about the possibility of slave insurrections.

Mobilization for war proved to be easier in the North than it was in the South. To fund the war effort and finance the expansion of Union infrastructure, Republicans in Congress drastically expanded government. Virtually every sector of the Northern economy became linked to the war effort. Republicans in Congress passed several measures in 1862. The Homestead Act provided generous inducements for Northerners to relocate and farm in the West. Settlers could lay claim to 160 acres of federal land by residing on the property for five years and improving it. Congress chartered two companies, the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific, and provided generous land grants and financing for these two businesses to connect the country by rail.

Congress paid for the war using a tax on the income of the wealthy, a tax on all inheritances, and high tariffs on imports. Two National Bank Acts, in 1863 and 1864, eliminated the currency issued by state banks, called on the U.S. Treasury to issue war bonds and on Union banks to buy the bonds. A Union advertising campaign to convince individuals to buy the bonds helped increase sales. The Legal Tender Act of 1862 created a national paper currency known as greenbacks, to replace state bank currencies. $150 million worth of greenbacks became legal tender and the Northern economy boomed, although high inflation also resulted.

Like the Confederacy, the Union turned to conscription to provide the troops needed to fight the war. In March 1863, Congress required all unmarried men between the ages of twenty and twenty-five and all married men between the ages of thirty-five and forty-five to register with the Union to fight in the Civil War. Draftees were selected by a lottery system. As in the South, a loophole in the law allowed individuals to hire substitutes if they could afford it. Others could avoid enlistment by paying $300 to the federal government. In keeping with the Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, African Americans were not citizens and were therefore exempt from the draft.

Early in the war, President Lincoln approached the issue of slavery cautiously. While he disapproved of slavery personally, he did not believe that he had the authority to abolish it. And Lincoln worried that making the abolition of slavery an objective of the war would cause the border slave states to join the Confederacy. His main goal in 1861 and 1862 was to restore the Union.

Lincoln’s Evolving Thoughts on Slavery

President Lincoln wrote the following letter to newspaper editor Horace Greeley on August 22, 1862. In it, Lincoln states his position on slavery, which is notable for being a middle-of-the-road stance. Lincoln’s later public speeches on the issue take the more strident antislavery tone for which he is remembered.

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time save Slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy Slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy Slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about Slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save this Union, and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views. I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty, and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men, everywhere, could be free. Yours, A. LINCOLN.

Since the beginning of the war, thousands of slaves had fled to the safety of Union lines. In May 1861, Union general Benjamin Butler reasoned that since Southern states had left the United States, he was not obliged to follow federal fugitive slave laws. Slaves who made it through the Union lines were shielded by the U.S. military and not returned to slavery. The intent was both to assist slaves and to deprive the South of a valuable source of manpower. In August 1861, legislators approved the Confiscation Act of 1861, empowering the Union to seize property, including slaves, used by the Confederacy. The Republican-dominated Congress took additional steps, abolishing slavery in Washington DC in April 1862. Congress passed a second Confiscation Act in July 1862, which extended freedom to runaway slaves and those captured by Union armies. Congress also addressed the issue of slavery in the West, banning the practice in the territories and making the 1846 Wilmot Proviso and the dreams of the Free-Soil Party a reality. However, even as the Union government took steps to aid individual slaves and to limit the practice of slavery, it passed no measure to address the institution of slavery as a whole.

Lincoln moved slowly and cautiously on the issue of abolition. However, as the war dragged on Republicans in Congress continued to call for the end of slavery. Responding to Congressional demands, Lincoln presented an ultimatum to the Confederates on September 22, 1862, shortly after the Confederate retreat at Antietam. He gave the Confederate states until January 1 1863 to rejoin the Union. If they did, slavery would continue in the slave states. If they refused, the war would continue and all slaves would be freed at its conclusion. The Confederacy took no action. It had committed itself to maintaining its independence and had no interest in the president’s ultimatum.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln made good on his promise and signed the Emancipation Proclamation. It stated “That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” The proclamation did not immediately free slaves in the border states, because these states were not in rebellion. But slaveholders in border states like Kentucky knew full well that if the institution were abolished throughout the South, it would not survive in a handful of border states between a free North and a conquered South. Despite the limits of the proclamation, Lincoln dramatically shifted the objective of the war increasingly toward ending slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation became a monumental step forward on the road to changing the character of the United States.

From the beginning of the war, the Confederacy placed great hope in being recognized and supported by Great Britain and France. European intervention in the conflict remained a strong possibility, but when it did occur, it was not in a way anticipated by either the Confederacy or the Union. Napoleon III of France believed the Civil War presented an opportunity for him to restore a French empire in the Americas. With the United States preoccupied, the time seemed ripe for action. Napoleon’s target was Mexico, and in 1861, a large French fleet landed in Veracruz. The French attempted to capture Mexico City, but the advance came to an end when Mexican forces defeated the French in 1862. Despite this setback, France eventually did conquer Mexico, establishing a regime that lasted until 1867. Rather than coming to the aid of the Confederacy, France used the Civil War to invade a sovereign nation that happened to be near territories it had once held in North America.

Still, the Confederacy had great confidence that it would find an ally in Great Britain despite the antislavery sentiment there. Southerners hoped Britain’s dependence on cotton for its textile mills would keep the country on their side. The Confederacy purchased two British armored blockade runners, the CSS Florida and the CSS Alabama. Both were destroyed during the war. The Confederacy’s staunch commitment to slavery eventually worked against British recognition and support. The 1863 Emancipation Proclamation ended any doubts the British had about the goals of the Union cause. In the aftermath of the proclamation, many in Great Britain cheered for a Union victory. Ultimately, Great Britain, like France, disappointed the Confederacy’s hope of an alliance, leaving the outnumbered and out-resourced CSA to fend for themselves.

At the beginning of the war, in 1861 and 1862, Union forces had used contrabands, or escaped slaves, for manual labor. The Emancipation Proclamation, however, led to the enrollment of African American men as Union soldiers. Former slaves as well as free blacks from the North, enlisted, and by the end of the war in 1865 their numbers had swelled to over 190,000. Racism among whites in the Union army fueled the belief that black soldiers could never be effective or trustworthy. Although many black soldiers saw combat duty, racism as well as concern over how they would be treated if captured affected the types of tasks assigned to them. Many black regiments were limited to hauling supplies, serving as cooks, digging trenches, and doing other types of labor, rather than fighting on the battlefield. African American soldiers also received lower wages than their white counterparts: ten dollars per month, with three dollars deducted for clothing. White soldiers, in contrast, received thirteen dollars monthly, with no deductions. Abolitionists and their Republican supporters in Congress worked to correct this discriminatory practice, and in 1864, black soldiers began to receive the same pay as white soldiers plus retroactive pay to 1863.

African American soldiers welcomed the opportunity to fight to free the slaves still trapped in the South. 85 percent were former slaves, fighting for the end of slavery. One black regiment, the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers, distinguished itself at Fort Wagner in South Carolina by fighting valiantly against an entrenched Confederate position. They willingly gave their lives for the cause. The CSA, not surprisingly, showed no mercy to black troops. In April 1864, Southern forces took back Fort Pillow in Tennessee from Union forces that had captured it in 1862. Confederate troops under Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest, the future founder of the Ku Klux Klan, overran the fort and the Union defenders surrendered. Instead of taking the black soldiers prisoner as they did the whites, the Confederates executed them. The massacre outraged the North and the Union refused to engage in any future exchanges of prisoners with the Confederacy.

In the final years of the war, Union forces increasingly engaged in total war, not distinguishing between military and civilian targets. They destroyed everything that lay in their path, committed to breaking the will of the Confederacy and forcing an end to the war. General Grant, mastermind of the Vicksburg campaign, took charge of the war effort. Grant pushed forward relentlessly, despite huge losses of men. In 1864, Grant committed his forces to destroying Lee’s army in Virginia. The immense losses that Grant’s forces suffered hurt Union morale. The war seemed unending, and many in the North began to question the war and desire peace. Undaunted by the changing opinion in the North and hoping to destroy the Confederate rail network in the Upper South, Grant laid siege to Petersburg for nine months. As the months wore on, both sides dug in, creating miles of trenches and gun emplacements.

The other major Union campaigns of 1864 were more successful and gave President Lincoln the advantage that he needed to win reelection in November. In August 1864, the Union navy captured Mobile Bay. General Sherman invaded the Deep South, advancing slowly from Tennessee into Georgia. The fall of Atlanta helped reverse the North’s sinking morale. In keeping with the logic of total war, Sherman’s forces cut a swath of destruction to Savannah. In what was called Sherman’s March to the Sea, the Union army destroyed everything in its path to demoralize the Confederacy, despite strict instructions regarding the preservation of civilian property. Homes were looted, houses and barns were burned, food was stolen, crops were destroyed, orchards were burned, and livestock was killed or confiscated. Savannah fell on December 21 1864. In 1865, Sherman’s forces invaded South Carolina, capturing Charleston and Columbia. In Columbia, the state capital, the Union army burned slaveholders’ homes and destroyed much of the city. From South Carolina, Sherman’s force moved north to join Grant and destroy Lee’s army.

Dolly Sumner Lunt on Sherman’s March to the Sea

The following account is by Dolly Sumner Lunt, a widow who ran her Georgia cotton plantation after the death of her husband. She describes General Sherman’s march to Savannah, where he enacted the policy of total war by burning and plundering the landscape to inhibit the Confederates’ ability to keep fighting.

Alas! little did I think while trying to save my house from plunder and fire that they were forcing my boys [slaves] from home at the point of the bayonet. One, Newton, jumped into bed in his cabin, and declared himself sick. Another crawled under the floor,—a lame boy he was,—but they pulled him out, placed him on a horse, and drove him off. Mid, poor Mid! The last I saw of him, a man had him going around the garden, looking, as I thought, for my sheep, as he was my shepherd. Jack came crying to me, the big tears coursing down his cheeks, saying they were making him go. I said: ‘Stay in my room.’ But a man followed in, cursing him and threatening to shoot him if he did not go; so poor Jack had to yield. . . . Sherman himself and a greater portion of his army passed my house that day. All day, as the sad moments rolled on, were they passing not only in front of my house, but from behind; they tore down my garden palings, made a road through my back-yard and lot field, driving their stock and riding through, tearing down my fences and desolating my home—wantonly doing it when there was no necessity for it. . . . About ten o’clock they had all passed save one, who came in and wanted coffee made, which was done, and he, too, went on. A few minutes elapsed, and two couriers riding rapidly passed back. Then, presently, more soldiers came by, and this ended the passing of Sherman’s army by my place, leaving me poorer by thirty thousand dollars than I was yesterday morning. And a much stronger Rebel!

Despite the military successes for the Union army in 1863, President Lincoln’s status among many Northern voters plummeted. Citing the suspension of habeas corpus, many saw him as a dictator, bent on grabbing power while senselessly and uncaringly drafting more young men into combat. Arguably, his greatest liability, however, was the Emancipation Proclamation and the enlistment of African American soldiers. Many whites in the North found this deeply offensive, since they still believed in racial inequality. The 1863 New York City Draft Riots illustrated the depth of white anger. Many Northerners believed that the Democratic candidate, General George B. McClellan, who did not support abolition and had been by Lincoln, would win the election. Many in the Republican Party considered Lincoln timid and indecisive. These Radical Republicans favored extending full rights to African Americans as well as completely refashioning the South after its defeat. The tide turned in favor of Lincoln, however, in the fall of 1864. Union victories bolstered Lincoln’s popularity and his reelection bid. In November 1864, despite forecasts to the contrary, Lincoln was reelected. Lincoln won all but three states: New Jersey and the border states of Delaware and Kentucky. To the chagrin of his Democratic opponent, McClellan, even Union army troops voted overwhelmingly for the incumbent President.

By the spring of 1865, it had become clear to both sides that the Confederacy could not last much longer. Atlanta, Savannah, Charleston, Columbia, Mobile, New Orleans, and Memphis had all been captured. In April 1865, Lee had abandoned both Petersburg and Richmond. Lee tried to unite his depleted army with Confederate forces commanded by General Johnston. Grant cut him off. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. By that time, Lee had fewer than 35,000 soldiers, while Grant had 100,000. Meanwhile, Sherman’s army proceeded to North Carolina, where General Johnston surrendered on April 19, 1865. The Civil War had come to an end after ending the lives of more than 600,000 soldiers. Many more had been wounded. Thousands of women were left widowed. Children were left without fathers, and many parents were deprived of a source of support in their old age. In some areas, an entire generation of young women was left without marriage partners. Property had been destroyed, and towns and cities were laid to waste. With the conflict finally over, the very difficult work of reconciling North and South and reestablishing the United States lay ahead.

From the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, Lincoln’s goal had been to bring the rebellious Southern states back the Union. In early December 1863, the president unveiled a three-part proposal for how the states would return. The “ten percent” plan gave a general pardon to all Southerners except high-ranking Confederate government and military leaders; required 10 percent of the 1860 voting population in the rebel states to take an oath of allegiance to the United States and accept the emancipation of slaves; and declared that once ten percent of southern voters took those oaths, the restored Confederate states would draft new state constitutions.

Lincoln hoped that the leniency of the plan, which allowed 90 percent of the rebels to avoid swearing allegiance to the Union, would bring about a quick resolution and make emancipation more acceptable everywhere. This approach appealed to the moderate wing of the Republican Party, which wanted to put the nation on a speedy course toward reconciliation. However, the proposal instantly drew fire from a larger faction of Radical Republicans in Congress who did not want to deal moderately with the South. Radical Republicans wanted to remake the South and punish the rebels. They insisted on harsh terms for the defeated Confederacy and protection for former slaves, going far beyond what the president proposed.

In February 1864, the Radical Republicans answered Lincoln with a proposal of their own. Their proposal, the Wade-Davis Bill, called for a majority of voters and government officials in Confederate states to take an Ironclad Oath, swearing that they had never supported the Confederacy or made war against the United States. Those who could not or would not take the oath would be unable to take part in the future political life of the South. When Congress passed the bill, the president refused to sign, using the pocket veto to kill the bill. Lincoln understood that no Southern state would have honestly met the criteria of the Wade-Davis Bill, and its passage would simply have delayed the reconstruction of the South.

Despite the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, the legal status of slaves and the institution of slavery remained unresolved. The Republican Party made the abolition of slavery a top priority by including the issue in its 1864 party platform. The president, along with the Radical Republicans, made good on this campaign promise in 1864 and 1865. A constitutional amendment passed the Senate in April 1864 and the House of Representatives in January 1865. The amendment then made its way to the states, where it swiftly gained the necessary support, including in the South. In December 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment was officially ratified and added to the Constitution. The first amendment added to the Constitution since 1804, it overturned a centuries-old practice by permanently abolishing slavery.

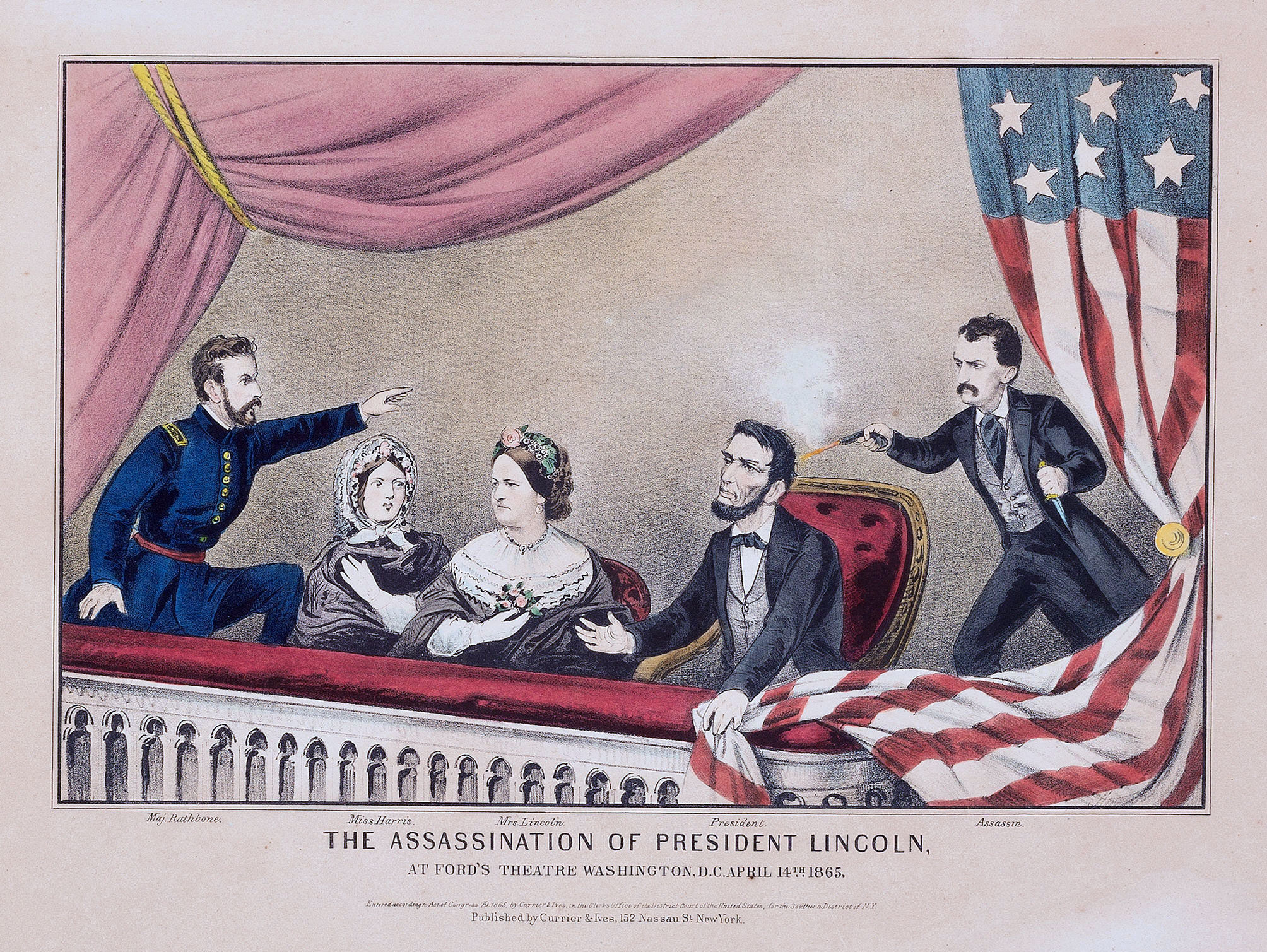

President Lincoln never saw the final ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. On April 14, 1865, the well-known actor John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln while he was attending a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington. The president died the next day. Booth supported the Confederacy and white supremacy, and his act was part of a larger conspiracy to eliminate the heads of the Union government and keep the Confederate fight going. One of Booth’s associates stabbed and wounded Secretary of State William Seward the night of the assassination. Another associate abandoned the planned assassination of Vice President Andrew Johnson at the last moment. Although Booth initially escaped capture, Union troops shot and killed him on April 26, 1865, in a Maryland barn. Eight other conspirators were convicted of participating in the conspiracy, and four were hanged. Lincoln’s death earned him immediate martyrdom, and hysteria spread throughout the North. To many Northerners, the assassination suggested an even greater conspiracy than what was revealed, masterminded by the unrepentant leaders of the defeated Confederacy. Radical Republicans exploited this fear and used the outrage of Lincoln’s assassination to advance their agenda in the ensuing months.

Media Attributions

- US_SlaveFree1858 © Kenmayer is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Charleston_Mercury_Secession_Broadside,_1860 © Charleston Mercury is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Confederate_States_map_1861-12-31_to_1865-05-05 © Golbez is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Abraham_Lincoln_inauguration_1861 © Alexander Gardner is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bombardment_of_Fort_Sumter_engraving_by_unknown_artist_1863 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1860-61_Secession_in_Appalachia_by_County © Dubyavee is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- First_Battle_of_Bull_Run_Kurz_&_Allison © Kurz & Allison is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1600px-CSA-T1-$1000-1861 © Godot13 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1780169 © Julius Bien is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Masterly_Inactivity,_Civil_War_Cartoon_1862 © Frank Leslie's Paper is licensed under a Public Domain license

- second-battle-field-at-bull-run-1600 © Robert Knox Sneden is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Thure_de_Thulstrup_-_Battle_of_Shiloh © Thure de Thulstrup is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Apr2_richmond_riot © Prensa is licensed under a Public Domain license

- US-$1-LT-1862-Fr-16c © Godot13 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Lincoln’s_Last_Warning,_October_1862 © Harpers Weekly is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Emancipation_Proclamation © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- USS_Kearsarge_CSS_Alabama © Xanthus Russell Smith is licensed under a Public Domain license

- DutchGapb © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Redeeming_the_republic_-_the_third_period_of_the_war_of_the_rebellion,_in_the_year_1864_(1889)_(14772788622) © Charles Carleton Coffin is licensed under a Public Domain license

- VicksburgBlockade © Currier & Ives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sherman’s_march_to_the_sea)_-_F.O.C._Darley_fecit_LCCN2003679761 © Alexander Hay Ritchie is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Columbia_demands_her_children!_LCCN2008661676 © Joseph E. Baker is licensed under a Public Domain license

- _Surrender_of_Gen._Lee,_at_Appomattox_C.H._VA,_April_9th_1865._ © Currier & Ives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Lincoln_and_Johnsond © Joseph E. Baker is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 13th Amendment © NARA is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Assassination_of_President_Lincoln_(color)_-_Currier_and_Ives_-_Original © Currier & Ives is licensed under a Public Domain license