3 Early North American Colonization

Spanish North America

During the 1500s, Spain expanded its colonial empire to the Philippines in the Far East and to areas in the Americas that later became the United States. The Spanish ideal for colonial society included natives eager to work and embrace Christianity, mountains of gold and silver, and a social order where everyone knew their place. Patriarchy and social hierarchy shaped the Spanish colonial world. Families achieved status by men’s military service to expand the empire, just as men had been ennobled by conquest for centuries during the Reconquista. The Spanish word for gentleman, hidalgo, literally means “son of something” (hijo de algo), suggesting that common men could become noble by acquiring wealth, lands, and status as a conquistador. The Spanish held themselves to be atop the social pyramid, with native peoples and Africans beneath them. Because relatively few Spanish women emigrated to the colonies, many conquistadors took native women as wives and mistresses. Although the Spaniards believed pure Spanish blood (sangre puro) was most noble, in practice Spanish-American society became racially mixed as Spanish men and native women had Mestizo children. In time an elaborate caste system developed where the social pyramid consisted of first Peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain on the Iberian Peninsula), then Criollos (Creoles of pure Spanish ancestry, born in the Colonies), followed by Mestizos whose status often reflected the percentage of Spanish ancestry they could claim. At the bottom were African slaves and Indians who were often also enslaved if they didn’t escape to the mountains of jungles where they could not be tracked.

The world native peoples had known before the coming of the Spanish was devastated by European diseases and further upset by Spanish colonial practices. The Spanish imposed the encomienda system in the areas they controlled and expanded the mita. Under these systems, authorities sometimes assigned Indian workers to mine and plantation owners with the understanding that the recipients would defend the colony and teach the workers the tenets of Christianity. In reality, the encomienda system exploited native workers. It was eventually replaced by another colonial labor system, the repartimiento, which required Indian towns to supply a pool of labor for Spanish overlords.

Spain gained a foothold in present-day Florida, viewing the region north of the Gulf of Mexico as a logical extension of their Caribbean empire, similar to Mexico itself. Before Cortés ever marched from Veracruz to Tenochtitlán in 1519, Juan Ponce de León had claimed the area around today’s St. Augustine for the Spanish crown in 1513, naming the land Pascua Florida (Feast of Flowers, or Easter) for the nearest feast day. Ponce de León was unable to establish a permanent settlement there, but by 1565, Spain needed an outpost to confront French and English privateers who used Florida as a base from which to attack treasure-laden Spanish ships heading from Cuba to Spain. The threat to Spanish interests was heightened in 1562 when a group of French Protestants (Huguenots) established a small settlement they called Fort Caroline, north of St. Augustine. With the authorization of King Philip II, Spanish nobleman Pedro Menéndez led an attack on Fort Caroline, killing most of the colonists and destroying the fort. The contest over Florida illustrates how European rivalries spilled over into the Americas, especially religious conflict between Catholics and Protestants.

In 1565, the victorious Menéndez founded St. Augustine, which became oldest permanent European settlement in the North America. In the process, the Spanish displaced the local Timucua Indians from their ancient town of Seloy, which had stood for centuries. Europeans typically built their cities on the sites of previous native settlements (other examples are Mexico City, Cusco, and Plymouth). The Timucua population had been devastated by diseases introduced by the Spanish, shrinking from around 200,000 before contact to fifty thousand in 1590. By 1700, only one thousand Timucua remained. Spanish Florida made an inviting target for Spain’s imperial rivals, especially the English, who wanted to gain access to the Caribbean. In 1586, Spanish settlers in St. Augustine discovered their vulnerability when the English pirate Sir Francis Drake nearly destroyed the town with a fleet of twenty ships and one hundred men. The Spanish built more wooden forts, all of which were burnt by raiding European rivals. Between 1672 and 1695, the Spanish constructed a stone fort, Castillo de San Marcos, to better defend St. Augustine against challengers.

Farther west, the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico) looked north to expand its territory into the land of the Pueblo Indians. Juan de Oñate explored throughout the region that is now the southwestern United States for Spain in the late 1590s. The Spanish hoped the region would yield gold and silver, but found little of value to them. In 1610, Spanish settlers established themselves at Santa Fe where many Pueblo villages were located. Missionaries labored to match Spain’s physical conquest with a spiritual conquest by converting the Pueblo to Christianity. The Pueblo adopted parts of Catholicism that dovetailed with their own long-standing views of the world. Spanish priests insisted that natives discard their old ways entirely and angered the Pueblo by focusing on converting the children, drawing them away from their parents. This deep insult, combined with an extended period of drought and increased attacks by their rivals the Apache and Navajo in the 1670s, inspired the Pueblo to try to push the Spanish and their religion from the area. Pueblo leader Po’Pay demanded a return to native ways so the hardships his people faced would end. To him and to thousands of Pueblo people, it seemed obvious that “when Jesus came, the Corn Mothers went away.” Expelling the Spanish would bring a return to prosperity and a pure, native way of life.

In 1680, the Pueblo launched a coordinated rebellion against the Spanish. The Pueblo Revolt killed over four hundred Spaniards and drove the rest, perhaps as many as two thousand, south toward Mexico. However, when droughts and attacks by rival tribes continued, the Spanish sensed an opportunity to regain their foothold. In 1692, they returned and reasserted their control of the area. Some of the Spanish explained the Pueblo success in 1680 as the work of the Devil, who had stirred up the Pueblo to take arms against God’s chosen people. The Spanish congratulated themselves that they and their God had prevailed in the end.

Questions for Discussion

- Why do we often forget that the first permanent European settlement in North America was St. Augustine?

- How do you think the racial mixing of Spanish America affected later attitudes about race?

New Netherland and New France

Seventeenth-century French and Dutch colonies in North America were modest in comparison to Spain’s global empire. New France and New Netherland remained small commercial operations focused on the fur trade and did not attract much immigration. The Dutch in New Netherland confined their operations to Manhattan Island, Long Island, the Hudson River Valley, and what later became New Jersey. Dutch trade goods circulated widely among the native peoples in these areas and spread to the interior of the continent along preexisting native trade routes. French farmer-settlers called habitants eked out an existence along the St. Lawrence River. Traveling French fur traders and missionaries ranged far into the interior of North America, exploring the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi River. These voyageurs allowed France to make somewhat inflated imperial claims to lands that nonetheless remained firmly under the dominion of native peoples. And because most of the French in North America were voyageurs, unions between French men and native women were common. The ethnically-mixed Métis peoples of Canada who trace their ancestry to these unions were recognized by the Canadian government in 1982.

After Jacques Cartier’s voyages of discovery in the 1530s, France delayed creating permanent colonies in North America until Samuel de Champlain established Quebec as a French fur-trading outpost in 1608. Although the fur trade was lucrative, the French saw Canada as an inhospitable frozen wasteland and by 1640 fewer than four hundred settlers had made their homes there. French fishermen, explorers, and fur traders made extensive contact with the Algonquian natives. The Indians tolerated the newcomers because their numbers were modest and because the French supplied them with firearms for their ongoing wars with the Iroquois, who received weapons from their Dutch trading partners. These seventeenth-century conflicts centered on the lucrative trade in beaver pelts, earning them the name of the Beaver Wars. Indians had been very effective managers of game for centuries in the Northeast, but the seemingly insatiable market for beaver pelts in Europe encouraged them to hunt and trap beavers to near extinction, and to encroach on the territories of their neighboring tribes. Fighting between rival native peoples spread throughout the Great Lakes region.

The Dutch Republic emerged as a center of commerce in the 1600s. The fleets of the Dutch West India Company plied the waters of the Atlantic, while Dutch East India Company ships sailed to the “Spice Islands” of the Far East, establishing the Dutch colony that became Indonesia and returning with prized spices like pepper to be sold in bustling ports at home, especially Amsterdam. In North America, Dutch traders established themselves first near Albany and soon opened for business on Manhattan Island. Peter Stuyvesant, director-general of the North American settlement from 1647 to 1664, expanded the fledgling outpost of New Netherland east to present-day Long Island and for many miles north along the Hudson River. The elongated colony served primarily as a fur-trading post, with the powerful Dutch West India Company controlling all commerce. Fort Amsterdam, on the southern tip of Manhattan Island, defended the growing city of New Amsterdam. In 1655, Stuyvesant took over the small colony of New Sweden along the banks of the Delaware River in present-day New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. The conquest of the Delaware River colony ended Sweden’s colonial efforts in North America, but Swedish interest in America remained strong and resulted in extensive emigration to the US in the nineteenth century. Stuyvesant also defended New Amsterdam from Indian attacks by having African slaves build a protective wall on the city’s northeastern border, giving present-day Wall Street its name.

New Netherland grew slowly and by 1664 only nine thousand people lived there. Conflict with native peoples and dissatisfaction with the Dutch West India Company’s trading practices made the Dutch outpost unattractive to many migrants. The small population meant a severe labor shortage and the Dutch West India Company imported 450 African slaves between 1626 and 1664. The company had involved itself heavily in the slave trade since their 1637 capture of Elmina, the slave-trading outpost on the west coast of Africa, from the Portuguese. Population shortage also encouraged New Netherland to welcome non-Dutch immigrants including Protestants from Germany, Sweden, Denmark, and England. New Amsterdam embraced a degree of religious tolerance unusual in other colonies, allowing Jewish immigrants to become residents beginning in the 1650s. Such a wide variety of people lived in the Dutch colony that one observer claimed eighteen different languages could be heard on the streets of New Amsterdam. As new settlers arrived, the colony of New Netherland stretched farther to the north and the west.

The Dutch West India Company found the business of colonization in New Netherland to be expensive. To share some of the costs, it rewarded Dutch merchants who invested heavily with patroonships, or large tracts of land and the right to govern the tenants there. In return, the shareholder who gained the patroonship promised to pay for the passage of at least thirty Dutch farmers to populate the colony. One of the largest patroonships was granted to Kiliaen van Rensselaer, a directors of the Dutch West India Company. Rennselaer’s feudal holdings covered most of present-day Albany and Rensselaer Counties. This pattern of settlement created a yawning gap in wealth and status between the tenants who paid rent and the wealthy patroons who enjoyed not only their landholdings but profits of their company shares, and influence with the Dutch government.

Question for Discussion

- How did the French and Dutch strategy in the Americas differ from that of Britain? What were the implications for history?

British Colonies in the Caribbean and North America

At the start of the seventeenth century, the English had not established a successful permanent settlement in the Americas. Over the next century, however, they outpaced their rivals. The English encouraged emigration far more than the Spanish, French, or Dutch and established nearly a dozen colonies. England had experienced a dramatic rise in population in the sixteenth century, and the colonies appeared a welcoming place for those who faced overcrowding and poverty at home. In the early seventeenth century, thousands of English settlers came to what are now Virginia, Maryland, and the New England states in search of opportunity and a better life. Promoters of English colonization in North America, many of whom never ventured across the Atlantic, wrote about the bounty the English would find there. In Chesapeake Bay, English migrants who established Virginia and Maryland hoped to find gold but quickly discovered that growing tobacco was the only sure means of making money. Thousands of unmarried, unemployed, and impatient young Englishmen, along with a few Englishwomen, pinned their hopes for a better life on the tobacco fields of these two colonies.

A very different group of English men and women flocked to New England, many spurred by religious motives. Many of the Puritans crossing the Atlantic brought families and children. Although promoters of emigration and colonial leaders like John Winthrop were motivated by profit and aware that in order to survive their new colonies needed to be part of the growing Atlantic commercial world, migrating families often were following their ministers and imagined a new society where reformed Protestantism would grow and thrive, providing a model for the rest of the Christian world. Many historians believe the fault lines separating what later became the North and South in the United States originated in the profound differences between the Chesapeake and New England colonies.

The source of those differences lay in England’s domestic problems. Troubles in England escalated in the 1640s when civil war broke out, pitting Royalist supporters of King Charles I and the Church of England against Puritan reformers and their supporters in Parliament. In 1649, Puritan Parliamentarians led by Oliver Cromwell gained the upper hand and, in a shockingly unprecedented move, executed the King. 1650s England became a republican commonwealth, a state without a king that rapidly descended into dictatorship. English colonists in America closely followed these events. Many Puritans left New England and returned home to take part in the struggle against the king and the national church. Other English men and women in the Chesapeake colonies and elsewhere in the English Atlantic World looked on in horror at the mayhem the Parliamentarians, led by the Puritan fanatics, appeared to unleash in England. The turmoil in England made the administration and imperial oversight of the Chesapeake and New England colonies difficult, and the two regions developed divergent cultures.

The Chesapeake colonies of Virginia and Maryland served a vital purpose in the developing seventeenth-century English empire by producing the valuable cash crop, tobacco. However, the first few years of Jamestown did not suggest the English outpost would survive. Most of the settlers were younger sons of the nobility, seeking their fortune in the new world since they would not be inheriting wealth or titles. They had no intention of working and expected either to find gold as the Spanish had or to become rich by trade or conquest. Settlers struggled both with each other and with the formidable Powhatan Indians who controlled the area. Jealousies and infighting among the English destabilized the colony. Captain John Smith, who wrote about his experiences in Virginia as well as New England, took control and exercised nearly-dictatorial powers. The settlers’ unwillingness and inability to grow their own food compounded their problems. Poor health, lack of food, and fighting with native peoples took the lives of many of the original Jamestown settlers. The winter of 1609–1610, which became known as “the starving time,” came close to annihilating the colony. Only sixty of the 500 settlers survived the winter, and some resorted to stealing bodies from graves for food. By June 1610, the few remaining settlers had decided to abandon the area; only the last-minute arrival of a supply ship from England prevented another failed colonization effort like the lost colony of Roanoke thirty years earlier. Supply ships brought new settlers, but only twelve hundred of the seventy-five hundred who came to Virginia between 1607 and 1624 survived.

George Percy on “The Starving Time”

George Percy, the youngest son of an English nobleman, was in the first group of settlers at the Jamestown Colony. He kept a journal describing their experiences; in the excerpt below, he reports on the privations of the colonists’ third winter.

Now all of us at James Town, beginning to feel that sharp prick of hunger which no man truly describe but he which has tasted the bitterness thereof, a world of miseries ensued as the sequel will express unto you, in so much that some to satisfy their hunger have robbed the store for the which I caused them to be executed. Then having fed upon horses and other beasts as long as they lasted, we were glad to make shift with vermin as dogs, cats, rats, and mice. All was fish that came to net to satisfy cruel hunger as to eat boots, shoes, or any other leather some could come by, and, those being spent and devoured, some were enforced to search the woods and to feed upon serpents and snakes and to dig the earth for wild and unknown roots, where many of our men were cut off of and slain by the savages. And now famine beginning to look ghastly and pale in every face that nothing was spared to maintain life and to do those things which seem incredible as to dig up dead corpses out of graves and to eat them, and some have licked up the blood which has fallen from their weak fellows.

—George Percy, “A True Relation of the Proceedings and Occurances of Moment which have happened in Virginia from the Time Sir Thomas Gates shipwrecked upon the Bermudes anno 1609 until my departure out of the Country which was in anno Domini 1612,” London 1624

Virginia weathered the worst and gradually gained a degree of permanence. Political stability came slowly and by 1619 the fledgling colony was operating under the leadership of a governor, a council, and a House of Burgesses. Economic stability came from the lucrative cultivation of tobacco. Although the local Indians cultivated a form of tobacco, an Englishman named John Rolfe (the husband of Pocahontas) introduced Spanish tobacco in 1611 from Trinidad, which he apparently smuggled out of the Spanish-controlled Caribbean. Smoking tobacco was a long-standing practice among native peoples, and English and other European consumers soon adopted it. By 1614 the Virginia colony was exporting tobacco back to England, which earned it a sizable profit and saved the colony from ruin. A second tobacco colony, Maryland, was formed in 1634, when King Charles I granted its charter to the Calvert family for their loyal service to England. Cecilius Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, conceived of Maryland as a refuge for English Catholics.

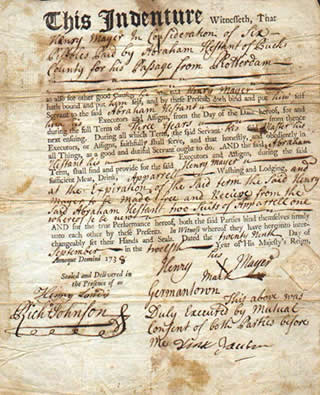

Growing tobacco proved very labor-intensive and the Chesapeake colonists needed a steady workforce to do the hard work of clearing land and caring for the tender young plants. To meet these labor demands, early Virginians relied on indentured servants. An indenture was a labor contract that young, impoverished, and often illiterate Englishmen and occasionally Englishwomen signed in England, pledging to work for between five and seven years growing tobacco in the Chesapeake colonies. In return, indentured servants received paid passage to America, food, clothing, and lodging. At the end of their indenture servants received “freedom dues” of food and other provisions to begin their lives as colonial settlers. In some cases, servants received a parcel land provided by the colony. The promise of a new life in America was a strong attraction for members of England’s underclass who had few options at home. In the 1600s, some 100,000 indentured servants traveled to the Chesapeake Bay. Most were poor young men in their early twenties. Life in the colonies was harsh. Indentured servants could not marry. If they committed a crime or disobeyed the “masters” who held their indenture contracts, servants often found their terms of service lengthened, sometimes by several years. Female indentured servants faced special dangers in what was essentially a bachelor colony. Many were exploited by unscrupulous tobacco planters who seduced them with promises of marriage. These planters would then sell pregnant servants’ contracts to other tobacco planters to avoid the costs of raising a child. Nonetheless, indentured servants who completed their terms of service often began new lives as tobacco planters. To entice even more migrants to the New World, the Virginia Company also implemented a headright system, offering men who paid their own passage to Virginia fifty acres plus an additional fifty for each servant or family member they brought with them. The headright system and the promise of a new life for servants acted as powerful incentives for English migrants to hazard the journey to the New World.

When they chose to settle along Chesapeake Bay, the English unknowingly placed themselves at the center of the Powhatan Confederacy, a powerful Algonquian alliance of thirty native groups with perhaps as many as twenty-two thousand people. Tensions ran high between the English and the Powhatan, and near-constant war prevailed as more and more English settlers arrived. The First Anglo-Powhatan War (1609–1614) resulted not only from the English colonists’ intrusion onto Powhatan land, but also from their refusal to follow native social protocols of gift exchange. English actions infuriated and insulted the Powhatan. In 1613, the settlers captured Pocahontas (also called Matoaka), the daughter of Wahunsenacawh, who the English called Chief Powhatan. Pocahontas helped quell the war in 1614 and promoters of colonization publicized her story as an example of the good work of converting the Powhatan to Christianity. Pocahontas married John Rolfe and travelled with him to England, where she met King James I. She died in London of a European disease, leaving behind a two-year old son, Thomas Rolfe, who returned to Virginia.

Peace in Virginia did not last long. The Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1620s) broke out after the death of Wahunsenacawh because of the expansion of the English settlement nearly one hundred miles into the interior and because of the continued insults and friction caused by English activities. The Chief’s brother, Opechanacanough, had never been reconciled to the English presence and went to war as soon as he became chief. The Powhatan attacked in 1622 and succeeded in killing almost 350 English, about a third of the settlers. The English responded by annihilating every Powhatan village around Jamestown and from then on became even more intolerant. The Third Anglo-Powhatan War (1644–1646) began with a surprise attack in which the Powhatan killed around five hundred English colonists. However, their ultimate defeat in this conflict forced the Powhatan to acknowledge King Charles I as their sovereign. Opechancanough was captured and paraded through Jamestown as a prisoner, although he was over 90 years old.The chief was then shot in the back by a soldier who had been assigned to guard him. The Anglo-Powhatan Wars, spanning nearly forty years, illustrate the degree of native resistance that resulted from English intrusion into the Powhatan confederacy.

Questions for Discussion

- How did the colonists of Virginia differ from the colonists of New England?

- Why did the Virginia colonists fight so many wars against the Powhatan?

- How did indentured servitude work? Does it strike you as a good deal?

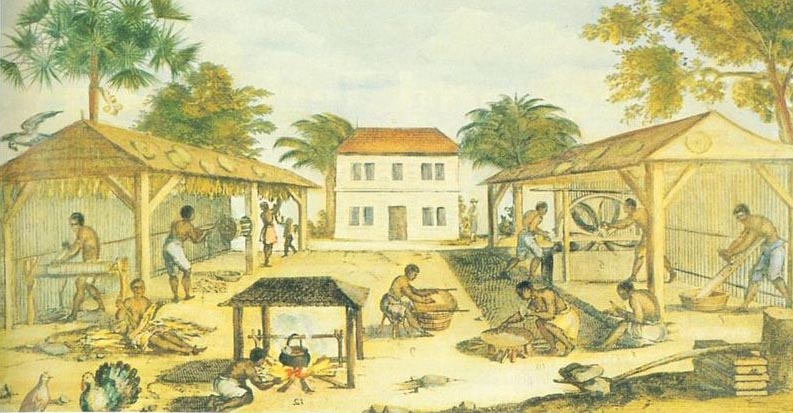

The transition from indentured servitude to slavery as the main labor source for English colonies happened first in the West Indies. On the island of Barbados, colonized in the 1620s, English planters first grew tobacco as their main export crop. In the 1640s they converted to sugarcane and, copying sugar planters on Spanish-controlled islands, began to rely on African slaves. In 1655, England took the much larger island of Jamaica from the Spanish and quickly turned it into a lucrative sugar island, using slave labor. While slavery was slower to take hold in the Chesapeake colonies, by the end of the seventeenth century, both Virginia and Maryland had also adopted slavery as the dominant form of labor to grow tobacco. Chesapeake colonists also enslaved native people, when they could capture them. When the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, their treatment resembled indenture more than chattel slavery, which legally defined Africans as property and not people. Many Africans worked as servants and, like their white indentured counterparts, could acquire land of their own. Some Africans who converted to Christianity became free landowners with white servants. The change in the status of Africans in the Chesapeake slavery based on race occurred in the last decades of the seventeenth century.

The English had no prior experience with slavery, since it did not exist in Britain. Bacon’s Rebellion hastened the transition to African chattel slavery in the Chesapeake colonies, after an uprising of both whites and blacks that was nearly successful overthrowing the colonial government convinced the authorities of the importance of separating white servants from black slaves. The rebels believed the Virginia government was impeding their access to land and wealth and doing little to clear the land of Indians. The leader of the rebels, Nathaniel Bacon, was a wealthy young Englishman who had arrived in Virginia in 1674. Despite an early friendship with Virginia’s royal governor, William Berkeley, Bacon found himself excluded from the governor’s circle of influential friends and councilors. He wanted land on the Virginia frontier but the governor, fearing war with neighboring Indian tribes, forbade further expansion. Bacon marshaled others, especially former indentured servants who believed the governor was denying them the right to own their own tobacco farms as promised after their years of indentured service. Bacon’s followers believed Berkeley’s frontier policy left English settlers at risk. Worse, Governor Berkeley tried to keep peace in Virginia by signing treaties with various local native peoples. Bacon and his followers, who saw all Indians as an obstacle to their access to land, advocated a policy of extermination.

In 1675, war broke out when Susquehannock warriors attacked settlements on Virginia’s frontier, killing English planters and destroying plantations, including one owned by Bacon. In 1676, Bacon and other Virginians attacked the Susquehannock without the governor’s approval. When Berkeley ordered Bacon’s arrest, Bacon led his followers to Jamestown, forced the governor to flee to the safety of Virginia’s eastern shore, and then burned the city. A vicious struggle ensued between Virginians loyal to the governor and those who supported Bacon. Reports of the rebellion traveled back to England, leading King Charles II to dispatch royal troops and English commissioners to restore order in the tobacco colonies. By the end of 1676, Virginians loyal to Governor Berkeley gained the upper hand, executing several leaders of the rebellion. Bacon escaped the hangman’s noose, instead dying of dysentery. The rebellion fizzled in 1676, but Virginians remained divided as supporters of Bacon continued to harbor grievances over access to Indian land.

Bacon’s Rebellion helped spur the adoption of racial slavery in the Chesapeake colonies. At the time of the rebellion, indentured servants made up the majority of laborers in the region. Wealthy whites worried over the presence of this large class of laborers and the relative freedom they enjoyed, as well as the alliance that black and white servants had forged in the course of the rebellion. Black and white workers lived in similar conditions and often mingled with each other. Replacing indentured servitude with black slavery diminished the risks caused by this contact and shared experience. Planters reduced their reliance on white indentured servants who were often dissatisfied and troublesome, and created a caste of racially defined laborers whose movements could be strictly controlled. Racial separation also lessened the possibility of further alliances between black and white workers. Racial slavery even served to heal some of the divisions between wealthy and poor whites, who could now unite as members of a “superior” racial group. While colonial laws in the tobacco colonies had made slavery a legal institution before Bacon’s Rebellion, new laws passed in its wake severely curtailed black freedom and laid the foundation for racial slavery. Virginia passed a law in 1680 prohibiting free blacks and slaves from bearing arms, banning blacks from congregating in large numbers, and establishing harsh punishments for slaves who assaulted Christians or attempted escape. Two years later, another Virginia law stipulated that all Africans brought to the colony would be slaves for life. The increasing reliance on slaves in the tobacco colonies and the draconian laws instituted to control them not only helped planters meet labor demands, but also assuaged English fears of further uprisings and alleviated class tensions between rich and poor whites.

Robert Beverley on Servants and Slaves

Robert Beverley was a wealthy Jamestown planter and slaveholder. This excerpt from his History and Present State of Virginia, published in 1705, clearly illustrates the contrast between white servants and black slaves.

Their Servants, they distinguish by the Names of Slaves for Life, and Servants for a time. Slaves are the Negroes, and their Posterity, following the condition of the Mother, according to the Maxim, partus sequitur ventrem [status follows the womb]. They are call’d Slaves, in respect of the time of their Servitude, because it is for Life.

Servants, are those which serve only for a few years, according to the time of their Indenture, or the Custom of the Country. The Custom of the Country takes place upon such as have no Indentures. The Law in this case is, that if such Servants be under Nineteen years of Age, they must be brought into Court, to have their Age adjudged; and from the Age they are judg’d to be of, they must serve until they reach four and twenty: But if they be adjudged upwards of Nineteen, they are then only to be Servants for the term of five Years.

The Male-Servants, and Slaves of both Sexes, are employed together in Tilling and Manuring the Ground, in Sowing and Planting Tobacco, Corn, &c. Some Distinction indeed is made between them in their Cloaths, and Food; but the Work of both, is no other than what the Overseers, the Freemen, and the Planters themselves do.

Sufficient Distinction is also made between the Female-Servants, and Slaves; for a White Woman is rarely or never put to work in the Ground, if she be good for any thing else: And to Discourage all Planters from using any Women so, their Law imposes the heaviest Taxes upon Female Servants working in the Ground, while it suffers all other white Women to be absolutely exempted: Whereas on the other hand, it is a common thing to work a Woman Slave out of Doors; nor does the Law make any Distinction in her Taxes, whether her Work be Abroad, or at Home.

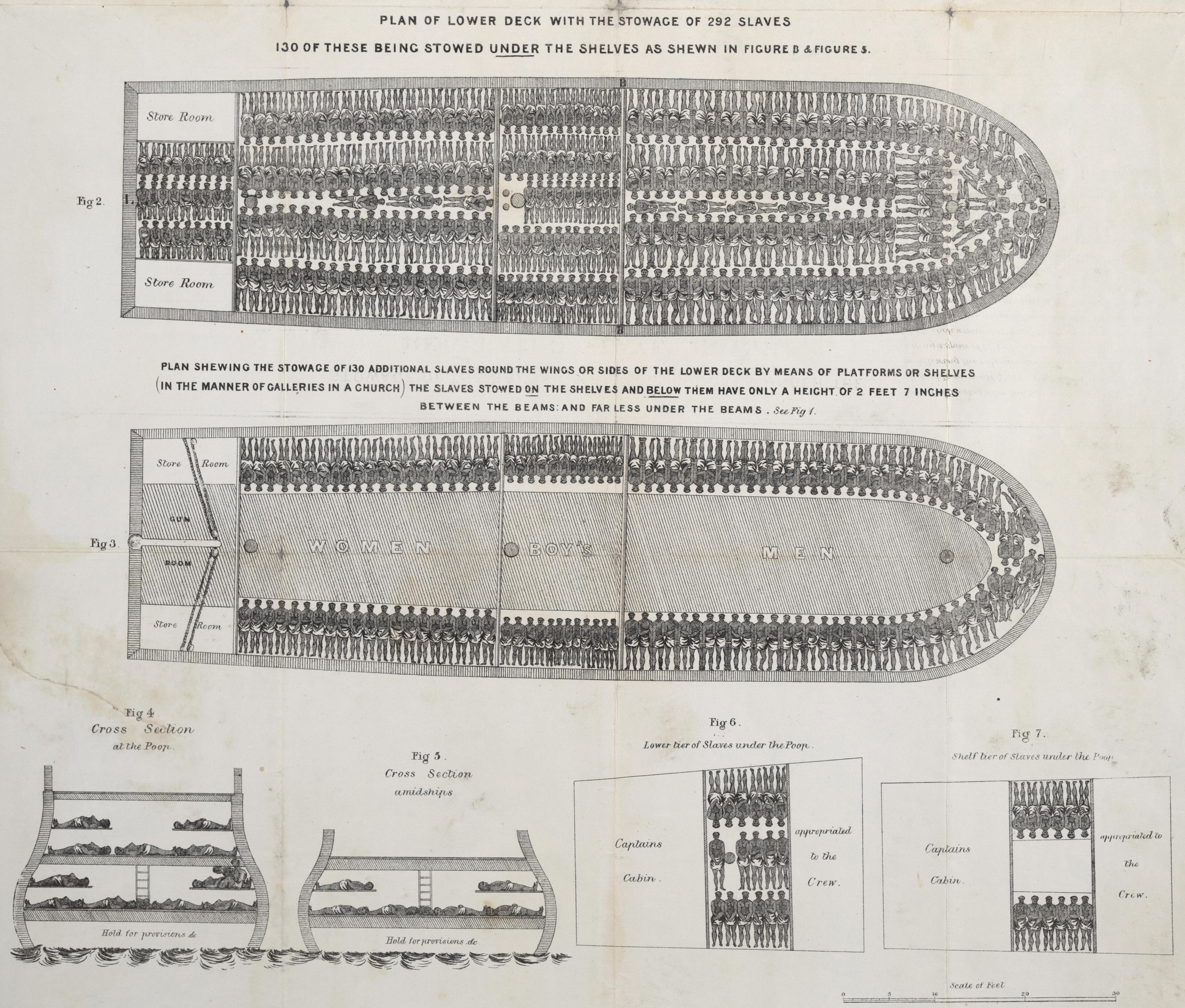

In the Caribbean and the southern North American colonies, adoption of cash crops such as sugar and tobacco created an insatiable demand for cheap labor. Free people were unwilling to work in the brutal conditions of a Barbados sugar plantation or a Virginia tobacco operation, and planters found they could maximize their profits by minimizing their labor costs. Nothing was cheaper than the forced labor of slaves who could be worked to death, so after 1600, the movement of Africans across the Atlantic accelerated. The English crown chartered the Royal African Company in 1672, giving the company a monopoly over the transport of African slaves to the English colonies. Over the next four decades, the company transported around 350,000 captive Africans from their homelands. By 1700, the tiny English sugar island of Barbados had a population of fifty thousand slaves, and the English had encoded the institution of chattel slavery into colonial law.

English colonists did not come from a society that included slavery and initially preferred to use servant labor. Nevertheless, by the end of the seventeenth century, English colonists throughout America and particularly in the Chesapeake Bay colonies relied on African slaves. While Africans had long practiced slavery among their own people, it had not been based on race. Africans enslaved other Africans as war captives, for crimes, and to settle debts; they generally used their slaves for domestic and small-scale agricultural work, not for growing cash crops on large plantations. African slavery was often a temporary condition rather than a lifelong sentence, and, unlike New World slavery, it was typically not passed from a slave mother to her children. African societies usually incorporated the enslaved people into the families they worked for, and by the end of a generation or two the children or grandchildren of the enslaved workers were often full-fledged family members.

The growing slave trade with Europeans had a profound impact on the people of West Africa, conferring prominence and power on local chieftains and merchants who traded slaves for European textiles, alcohol, guns, tobacco, and money. African rulers also charged Europeans for the right to trade in slaves and imposed taxes on slave purchases. Powerful African kingdoms even staged large-scale raids on each other and on weaker neighbors to meet the demand for slaves. Once sold to traders, all slaves sent to America endured the hellish Middle Passage, a transatlantic crossing that took one to two months. By 1625, more than 325,800 Africans had been shipped to the New World, though many thousands perished during the voyage. Four million enslaved Africans were transported to the Caribbean between 1501 and 1830. When they reached their destination in America, Africans found themselves trapped in shockingly brutal slave societies. In the Spanish, French, and English Caribbean, they were typically worked to death in three to six years on sugar plantations. In the Chesapeake colonies, they faced a lifetime of harvesting and processing tobacco. Everywhere, Africans resisted slavery, and running away was common. In Jamaica and elsewhere, runaway slaves created maroon communities, groups that resisted recapture and eked out a living from the land, rebuilding their communities as best they could. Many joined natives who had also fled European control and some formed communities that have lasted into the modern era. Like Indians, some Africans sought solace in the Christianity Europeans imposed on them. Others adhered to traditional ways, following spiritual leaders such as Vodun priests.

Questions for Discussion

- How did Bacon’s Rebellion change the Virginia colony’s attitude toward slavery?

- If England was a society without slavery, how did the English colonies become so dependent on the Atlantic slave trade?

New England

New England’s colonists discovered their new home was much less heavily occupied, but also less hospitable. The Pilgrims did not set out to migrate to a colder region and had actually been headed for a destination near the Hudson River, which they had heard good reports of while living in the Netherlands. Most European tracts boosting the Americas promised temperate climates and fertile soils (Captain John Smith’s Description of New England was an exception. Smith suggested the northeast was an idea location for industries like shipbuilding, fur-trading, and fishing). The Mid-Atlantic colonies and New England were at a similar latitude to the Mediterranean. Even Boston was farther south than the northern coast of Spain. Europeans were unaware of the Gulf Stream’s effect on western Europe’s climate, and assumed that conditions in America would reflect those of Europe. But as a result of the environments they encountered in America, while the English planters in Virginia and Maryland worked on expanding their profitable tobacco fields, the English in New England crowded together in towns where small farmers and artisans built more egalitarian communities focused on church and trade.

New England was settled largely by waves of Puritan families in the 1630s. Many who provided leadership in early New England were learned ministers who had studied at Cambridge or Oxford but who had questioned the practices of the Church of England. Dissenting ministers found themselves deprived of careers by the king and his officials, and their followers felt they had been blocked from opportunities for wealth and social advancement. Other Puritan leaders, such as the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop, came from the privileged class of English gentry. These well-to-do Puritans and many thousands more left their English homes not to establish a land of religious freedom, but to practice their own religion without persecution. Puritan New England offered them the opportunity to live as they believed the Bible demanded, but also to achieve the status and social mobility they were denied in England. In their “New” England, they set out to create a model of reformed Protestantism where there were no religiously-inspired political barriers to their success.

The conflict generated by Puritanism divided English society, partly because the Puritans demanded reforms that undermined the traditional culture. In the city where William Shakespeare had produced his masterpieces, Puritans called for an end to all theater, censuring playhouses as places of decadence. Indeed, the Bible itself became part of the struggle between Puritans and James I, who headed the Church of England. Soon after ascending the throne, James commissioned a new version of the Bible in an effort to stifle Puritan reliance on the Geneva Bible, which followed the teachings of John Calvin and placed God’s authority above the monarch’s. The King James Version, published in 1611, instead emphasized the majesty of kings. During the 1620s and 1630s, the conflict escalated to the point where the Anglican state church prohibited Puritan separatist ministers from preaching. According to the Church, Puritans represented a national security threat because their demands for cultural, social, and religious reforms undermined the king’s authority. Unwilling to conform to the Church of England, many Puritans found refuge in the New World. Yet those who emigrated to the Americas were not united. Some called for a complete break with the Church of England, while others remained committed to reforming the national church.

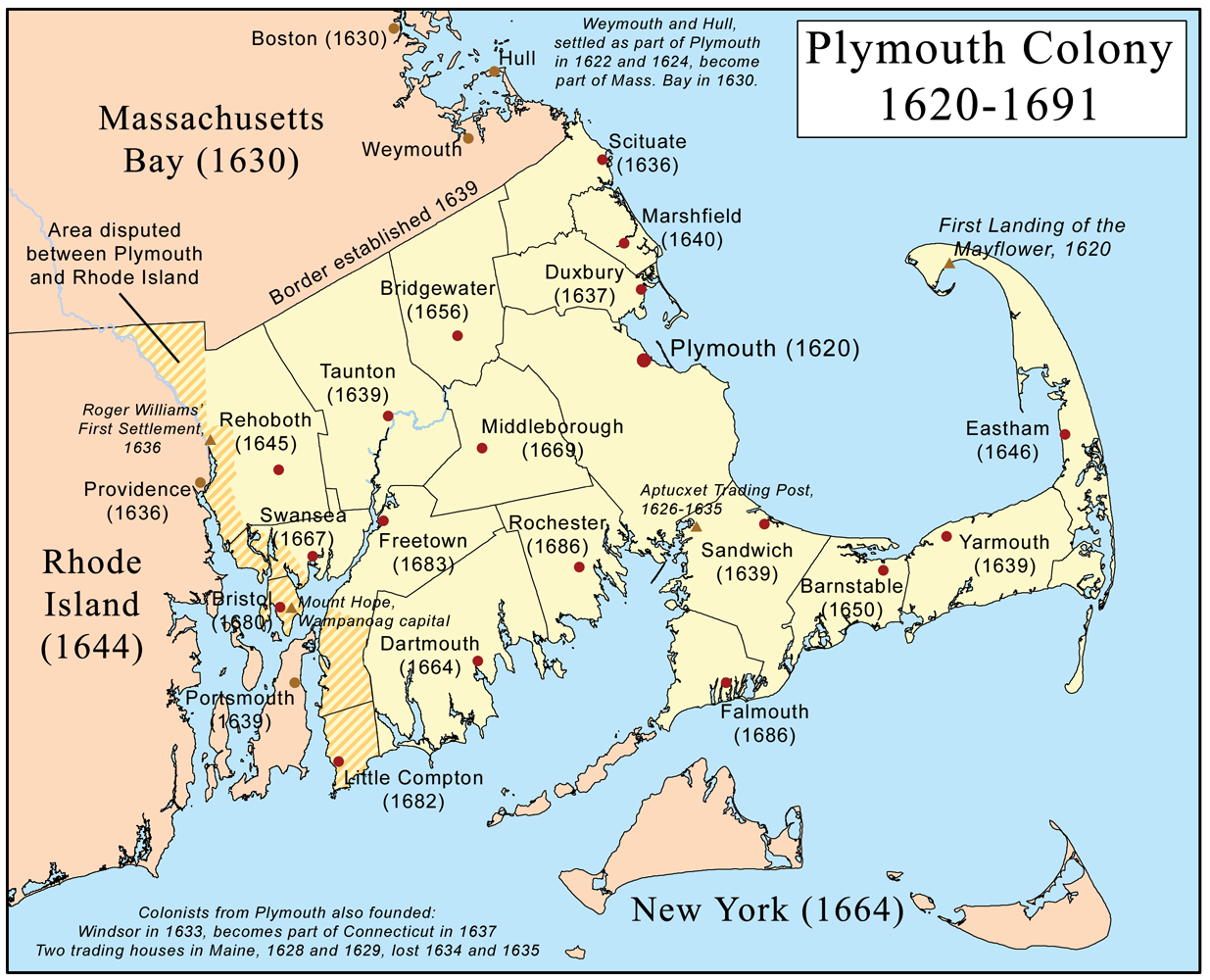

The first group of Puritans to make their way across the Atlantic was a small contingent known as the Pilgrims. Unlike other Puritans, they insisted on a complete separation from the Church of England and had first migrated to the Dutch Republic seeking religious freedom. Although they could worship without hindrance there, the Pilgrims grew concerned that they were losing their Englishness as they saw their children begin to learn the Dutch language and adopt Dutch ways. In addition, the English Pilgrims feared another attack on the Dutch Republic by Catholic Spain. In 1620, they moved on to found the Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts. The governor of Plymouth, William Bradford, was a Separatist, a proponent of complete separation from the English state church. Bradford and the other Pilgrim Separatists represented a major challenge to the prevailing vision of a unified English national church and empire. On board the Mayflower, which was aiming farther south but landed on the tip of Cape Cod, Bradford and forty other adult men signed the Mayflower Compact which presented a religious rather than an economic rationale for colonization. The compact expressed a community ideal of working together. When a larger exodus of Puritans established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1630s, the Pilgrims at Plymouth welcomed them and the two colonies cooperated with each other.

Different labor systems also distinguished early Puritan New England from the Chesapeake colonies. Puritans expected young people to work diligently at a craft or trade, and all members of their large families, including children, did the work necessary to run homes, farms, and businesses. Very few migrants came to New England as indentured laborers and some New England towns protected their well-disciplined homegrown workforce by refusing to allow outsiders in, assuring their sons and daughters steady employment. New England’s labor system produced remarkable results, notably a powerful maritime-based economy with scores of oceangoing ships and the crews necessary to sail them. During the colonial period, New England mariners sailing New England–made ships fished and whaled in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. New England merchants also transported Virginian tobacco, West Indian sugar, and slaves throughout the Atlantic World.

Much larger groups of Puritans left England in the 1630s, establishing the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the New Haven Colony, the Connecticut Colony, and Rhode Island. Unlike the exodus of young males to the Chesapeake colonies, these migrants arrived in families with young children and university-trained ministers. Their aim, according to John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts Bay, was to create a model of reformed Protestantism—a “city upon a hill,” and the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony stated as a goal that the colony’s people “may be soe religiously, peaceablie, and civilly governed, as their good Life and orderlie Conversacon, maie wynn and incite the Natives of Country, to the Knowledg and Obedience of the onlie true God and Saulor of Mankinde, and the Christian Fayth.” To illustrate this, the seal of the Massachusetts Bay Company shows a half-naked Indian inviting more English settlers to “come over and help us.” In spite of the Puritans’ professed desire to “save” the Indians, many appreciated the Divine Providence they believed had eliminated most of the people who had preceded them in New England. The Pilgrim settlement of Plymouth was built on the site of the Indian town Patuxet which had been wiped out by disease a few years before the Pilgrims’ arrival. And in his history of “Christ’s Great Works in America” (Magnalia Christi Americana, 1702), Puritan minister Cotton Mather described his satisfaction with the Indian epidemics. Mather wrote that “The Indians of these parts had newly…been visited with such a prodigious Pestilence; as carried away not a Tenth, but Nine Parts of Ten (yea, ‘tis said Nineteen of Twenty) among them…So that the Woods were almost cleared of those pernicious Creatures, to make Room for better Growth”

Puritan New England differed in many ways from both England and the rest of Europe. Protestants emphasized literacy so that everyone could read the Bible. Puritans’ commitment to literacy led to the establishment of the first printing press in English America in 1636. In 1640, they published the first book in North America, the Bay Psalm Book. Although many people assume Puritans escaped England to establish religious freedom, they proved to be just as intolerant as the English state church. When dissenters such as Puritan minister Roger Williams and spiritual advisor (women could not be ministers) Anne Hutchinson challenged Governor Winthrop in Massachusetts Bay in the 1630s, they were banished. Roger Williams questioned the Puritans’ taking of Indian land. Williams also argued for a complete separation from the Church of England, as well as the idea that the state could not punish individuals for their beliefs. Puritan authorities found him guilty of spreading dangerous ideas, but he went on to found Rhode Island where Williams wrote favorably about native peoples, contrasting their virtues with Puritan New England’s intolerance. Anne Hutchinson was also prosecuted by Puritan authorities for her criticism of the evolving religious practices in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Literate Puritan women like Hutchinson (who ironically was the daughter of an Anglican priest) presented a challenge to the male ministers’ authority. Hutchinson’s main offense was her claim of direct religious revelation, a type of spiritual experience that negated the role of ministers. In 1638, she was excommunicated for her defiance of authority and banished from the colony. She went to Rhode Island and later, in 1642, sought safety among the Dutch in New Netherland. The following year, Algonquian warriors killed Hutchinson and her family. In Massachusetts, Governor Winthrop noted her death as the righteous judgment of God against a heretic.

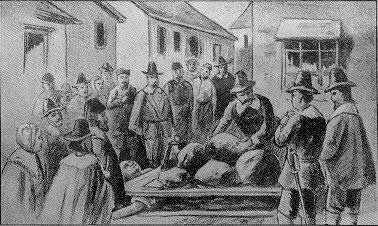

Like many other Europeans, Puritans believed in the supernatural. Every event appeared to be a sign of God’s mercy or judgment, and many believed in witches who allied with the Devil to do evil and cause deliberate harm such as the sickness or death of children, the loss of cattle, and other catastrophes. Hundreds were accused of witchcraft in Puritan New England, including people whose eccentric habits or unusual appearance bothered their neighbors. Women, seen as more susceptible to the Devil because of their supposedly weaker constitutions, made up the vast majority of suspects and victims of trial and execution. The most notorious cases occurred in Salem Massachusetts in 1692. Many of the accusers who prosecuted the suspected witches had been traumatized by Indian wars on the frontier and by unprecedented political and cultural changes in New England. Relying on their belief in witchcraft to help make sense of their changing world, Puritan authorities executed nineteen people and caused the deaths of several others.

Questions for Discussion

- Were the New England colonies truly about creating a model Christian society, a “city upon a hill”?

- Why were religious dissidents and witches so fiercely punished?

Like their Spanish and French Catholic rivals, English Puritans in America took steps to convert native peoples to their version of Christianity. John Eliot, the leading Puritan missionary in New England, urged natives in Massachusetts to live in “praying towns” established by English authorities for converted Indians. In keeping with the Protestant emphasis on reading scripture, he translated the Bible into the local Algonquian language in 1663. Eliot hoped that as a result of his efforts, some of New England’s native inhabitants would become preachers. Tensions had existed from the beginning between the Puritans and the native people who controlled southern New England. Relationships deteriorated as the Puritans continued to expand their settlements aggressively and as European ways increasingly disrupted native life. Like the series of wars the Virginia colony fought against the Powhatan, northern colonies were frequently at war with their Indian neighbors. When the Puritans had begun to arrive in the 1620s and 1630s, local Algonquian peoples had viewed them as potential allies in the conflicts already simmering between rival native groups. In 1621, the Wampanoag, led by Massasoit, made a peace treaty with the Pilgrims at Plymouth. In the 1630s, the Puritans in Massachusetts and Plymouth allied themselves with the Narragansett and Mohegan people against the Pequot, who had recently expanded into southern New England. In May 1637, the Puritans attacked a large group of several hundred Pequot along the Mystic River in Connecticut. To the horror of their native allies, the Puritans massacred all but a handful of the men, women, and children they found. The Pequot War in Connecticut, the Dutch-Indian War in the Hudson River Valley (1643), and the Beaver Wars (1650s) all ended badly for the Indians. Even King Philip’s War (1675), which is remembered as a disastrous, nearly-successful uprising by Massasoit’s son Metacomet, who had finally decided enough was enough, resulted in five times as many native deaths as European.

By the mid-seventeenth century, the Puritans had pushed their way further into the interior of New England, establishing fur-trading outposts that became towns along the Connecticut River Valley at Springfield (1636), Deerfield, and Northfield (both settled in 1673). There seemed no end to their expansion. Wampanoag leader Metacomet (known as King Philip among the English), the son of the chief who had made peace with the Pilgrims, was determined to stop the encroachment. The Wampanoag allied with the Nipmuck, Pocumtuck, and Narragansett to drive the English from the land. In the ensuing conflict, called King Philip’s War, native forces attacked farms and settlements throughout Massachusetts, endangering up to half of the frontier Puritan towns. By the end of 1675, the English (aided by Mohegans and Christian Indians) prevailed and sold many captives into slavery in the West Indies. The severed head of Metacomet was publicly displayed in Plymouth to deter future Indian attacks. Although many more Indians were killed than settlers, the war forever changed the English perception of native peoples. Puritan writers went to great lengths to vilify the natives as bloodthirsty savages. A new type of racial hatred became a defining feature of Indian-English relationships in the Northeast and New Englanders still tell stories of the Indian war that nearly succeeded.

While most of North America remained firmly under the control of native peoples for the first two centuries of European settlement, conflict increased as colonization spread and Europeans placed greater pressure upon the native populations, pushing Indians westward as the white population grew. Throughout the seventeenth century, the still-powerful native peoples waged war against the invading Europeans, achieving a degree of success in their effort to slow the spread of Europeans across the continent. At the same time, European goods had begun to change Indian life radically. In the 1500s, some of the earliest objects Europeans introduced to Indians were glass beads, copper kettles, metal utensils, knives, and guns. Iron awls made the creation of shell beads much easier and allowed a rapid increase in the production of wampum, used in ceremonies and as jewelry. As European settlements grew throughout the 1600s, European goods flooded into native communities. Soon native people were using commercially-acquired manufactured goods in the same ways as the Europeans. Many Indians abandoned their animal-skin clothing in favor of European textiles. Similarly, clay cookware gave way to metal cooking implements and Indians found that European flint and steel made starting fires much easier, and European metal traps and guns made them more effective against both game animals and human enemies. On the Great Plains, wild horses descended from escapees of conquistador herds increased the mobility of the Indians and changed the ways they hunted bison and waged war. In many of the horse-cultures that developed on the plains, the status of women (who as farmers had been the primary providers of food) decreased substantially. Contact with colonial communities and pressure to adopt elements of European culture and religion also suggested different relationships between the sexes. The influx of European materials also made warfare more lethal and changed traditional patterns of authority among tribes. Formerly weaker groups, if they had access to European metal and weapons, suddenly gained the upper hand against once-dominant rivals. Native peoples also used their new weapons against the European colonizers who had provided them.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did the Indians feel they had to go to war against the colonists?

- How did ongoing contact and trade between whites and Indians complicate native lifestyles and independence?

Primary Sources

Olaudah Equiano describes the Middle Passage, 1789

In this harrowing description of the Middle Passage, Olaudah Equiano described the terror of the transatlantic slave trade. Equiano eventually purchased his freedom and lived in London where he advocated for abolition.

Recruiting settlers to Carolina, 1666

Robert Horne’s wanted to entice English settlers to join the new colony of Carolina. According to Horne, natural bounty, economic opportunity, and religious liberty awaited anyone willing to make the journey. Horne wanted to recruit settlers of every social class, from those “of Genteel blood” to those who would have to sign a contract of indentured servitude.

Thomas Newe’s account of his experience in Carolina offers an interesting counter to Robert Horne’s prediction of what would await settlers. Newe describes deadly disease, war with Native Americans, and unprepared colonists. Newe longs for news from home but also appears committed to making a new life for himself in Carolina.

Haudenosaunee thanksgiving address

This Thanksgiving address was used by the six nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) to open and close major gatherings or meetings. The prayer was also sometimes used individually at the beginning or end of the day.

Rose Davis is sentenced to a life of slavery, 1715

Rose Davis was born to an indentured servant white woman and a Black man. Slave law claimed that children inherited the status of their mother, a law that enabled enslavers to control the reproductive functions of their enslaved women laborers. However, as race increasingly became a marker of slavery, even the children of free white women could be vulnerable to enslavement. Rose had been working as an indentured servant when she petitioned the court for her freedom. Instead, she was sentenced to a lifetime of slavery.

Media Attributions

- 1530px-Nouvelle-France_map-en.svg © Pinpin is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Ignacio_María_Barreda_-_Las_castas_mexicanas © Ignacio María Barreda is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-Baptista_Boazio’s_Map_of_Sir_Francis_Drake’s_Raid_on_St._Augustine_(published_in_1589)_(8879100326) © Baptista Boazio is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Castillo_de_San_Marcos © National Park Service is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Capitol_-_Po’_Pay © dougward is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- The_Trapper’s_Bride © Alfred Jacob Miller is licensed under a Public Domain license

- New_Amsterdam_and_its_people;_studies,_social_and_topographical,_of_the_town_under_Dutch_and_early_English_rule_(1902)_(14765778532) © John H. Innes is licensed under a Public Domain license

- CastelloPlanOriginal © Jacques Cortelyou is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1635_Blaeu_Map_of_New_England_and_New_York_(1st_depiction_of_Manhattan_as_an_Island)_-_Geographicus_-_NovaBelgicaetAngliaNova-blaeu-1635 © W. J. Blaeu is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Execution_of_Charles_I © C.R.V.N. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Capt_John_Smith’s_map_of_Virginia_1624 © Captain John Smith adapted by Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Large_Broadside_on_the_Maryland_Toleration_Act © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 00OPocahontas © USPS is licensed under a Public Domain license

- De_Bry_Chief_Virginia © Theodor De Bry is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Barbados © Richard Ligon is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Indenturecertificate © Greensburger is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1670_virginia_tobacco_slaves (1) © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Slaveshipposter © Plymouth Chapter of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Plymouthcolonymap © Kmusser is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- The_Mayflower_Compact_1620_cph.3g07155 © Jean Leon Jerome Ferris is licensed under a Public Domain license

- MassBaySeal © Michael G. Hall is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Giles_Corey_restored © Ridpath is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1600px-Tribal_Territories_Southern_New_England © Nikater adapted by Hydrargyrum is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- RISDM 48-246 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license