4 Colonial North America

When Charles II ascended the throne in 1660, English subjects on both sides of the Atlantic celebrated the restoration of the English monarchy after a decade of living without a king during the English Civil War and Cromwell’s dictatorial Commonwealth. Charles II lost little time in strengthening England’s global power. From the 1660s to the 1680s, England added to its North American holdings by establishing the Restoration colonies of New York and New Jersey (taken from the Dutch) as well as Pennsylvania and the Carolinas. In order to reap the greatest economic benefit from England’s overseas possessions, Charles II expanded on the mercantilist Navigation Acts begun by Cromwell, requiring commerce to be conducted using British ships and controlling where and in what products the colonies could trade; although many colonial merchants ignored them and enforcement remained lax. All the Restoration colonies started as proprietary colonies through grants the king gave to a trusted individual, family, or group.

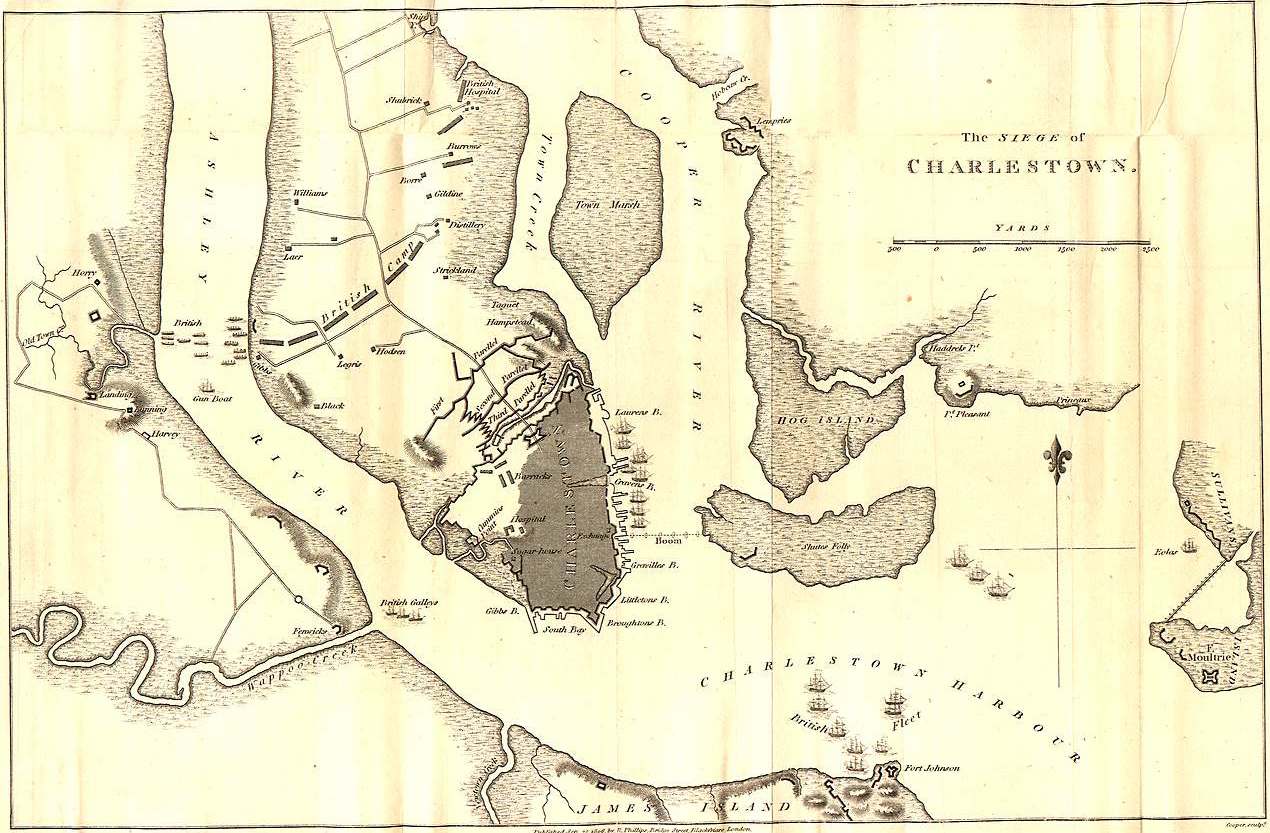

King Charles II hoped to establish English control of the region between Virginia and Spanish Florida, so in 1663 he issued a royal charter to eight loyal supporters, each of whom was to be a feudal-style proprietor of a region of the province of Carolina. These proprietors did not relocate to the colonies, however. Instead, English plantation owners from the well-established English sugar colony of Barbados migrated to the southern part of Carolina to settle there. In 1670, they established Charles Town (later Charleston), named in honor of Charles II, at the junction of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. As the settlement around Charles Town grew, farmers raised livestock for export to the West Indies. In the northern pine forests, settlers turned sap into turpentine, pitch, and the tar used to waterproof wooden ships. Political disagreements between settlers in the northern and southern parts of Carolina escalated in the 1710s through the 1720s and led to the creation, in 1729, of two colonies, North and South Carolina. Southern farmers had begun producing rice and indigo (a dark blue dye used by English royalty) in the early 1700s, and South Carolina continued to depend on these main crops. North Carolina continued to produce items for ships, especially turpentine and tar, and its population increased as Virginians moved there to expand their tobacco holdings. Tobacco was the primary export of both Virginia and North Carolina, which also traded in deerskins and slaves from Africa.

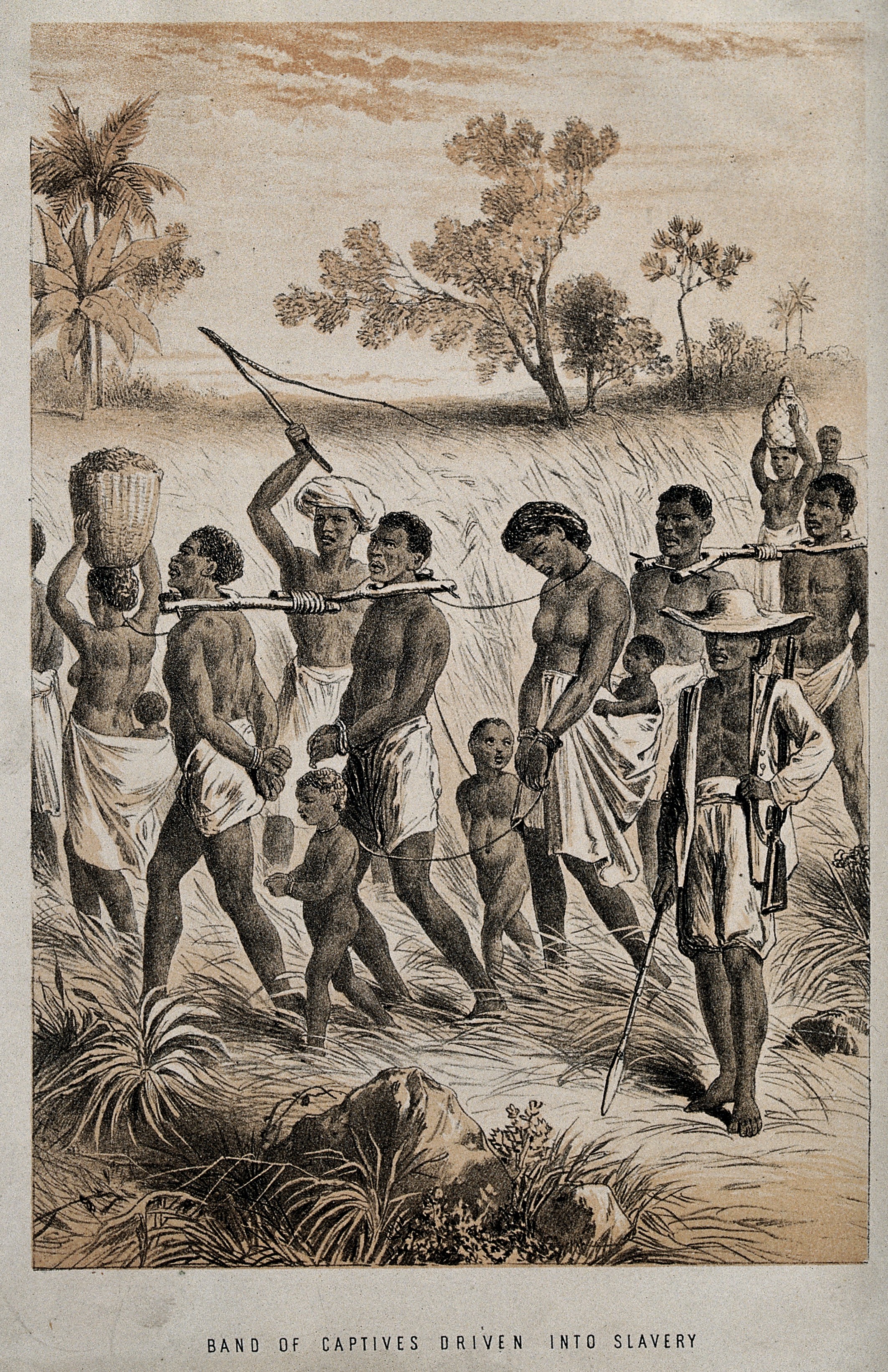

Slavery developed quickly in the Carolinas, largely because so many of the early migrants came from Barbados, where slavery was a well-established practice. By the end of the 1600s, a very wealthy class of rice planters attained dominance in the southern part of the Carolinas, especially around Charles Town. By 1715, a majority of the South Carolina population were enslaved Africans. The legal basis for slavery was established in the early 1700s as the Carolinas began to pass slave laws based on the Barbados slave codes of the late 1600s. These laws reduced Africans to the status of property to be bought and sold as other commodities.

As in other areas of English settlement, native peoples in the Carolinas suffered tremendously from the introduction of more European diseases. The southeastern region of North America had already been devastated by disease between the visits of De Soto in the 1530s and LaSalle in the 1670s. But the surviving natives were still susceptible to all the bacteria and viruses Europeans carried. Despite the effects of disease, Indians in the area endured and, following the pattern we’ve seen elsewhere in the colonies, grew dependent on European goods. Local Yamasee and Creek tribes built up a trade deficit with the English, trading deerskins and captives for European guns. English settlers exacerbated tensions with local Indian tribes by expanding their rice and tobacco fields into Indian lands. Worse, English traders took native women captive as payment for debts. The outrages committed by traders combined with the seemingly unstoppable expansion of English settlement onto native land led to the outbreak of the Yamasee War (1715–1718), an effort by a coalition of local tribes to drive out the European invaders. This native effort to force the newcomers to leave their ancestral lands nearly succeeded in annihilating the Carolina colonies. Only when the Cherokee allied themselves with the English did the coalition’s goal of eliminating the English from the region falter. The Yamasee War demonstrates the key role native peoples played in shaping the outcome of colonial struggles and, perhaps most important, of English success taking advantage of disunity between different native groups.

Questions for Discussion

- Why was Britain concerned about their claim to the land between Virginia and Florida?

- How did trade between colonists and Indians lead to war?

King Charles II also set his sights on the Dutch colony of New Netherland. The English takeover of New Netherland originated in the imperial rivalry between the Dutch and the English. The Anglo-Dutch wars of the 1650s and 1660s were fought for commercial advantages in the Atlantic World. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1664–1667), English forces occupied the Dutch fur trading colony of New Netherland, and in 1664, Charles II gave this colony (including present-day New Jersey) to his brother James, Duke of York (later King James II). The colony and city were renamed New York in his honor. The Dutch on Manhattan Island and in the Hudson River Valley chafed under English rule and in 1673, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), the Dutch briefly recaptured their colony. However, by the end of the conflict the English had regained permanent control.

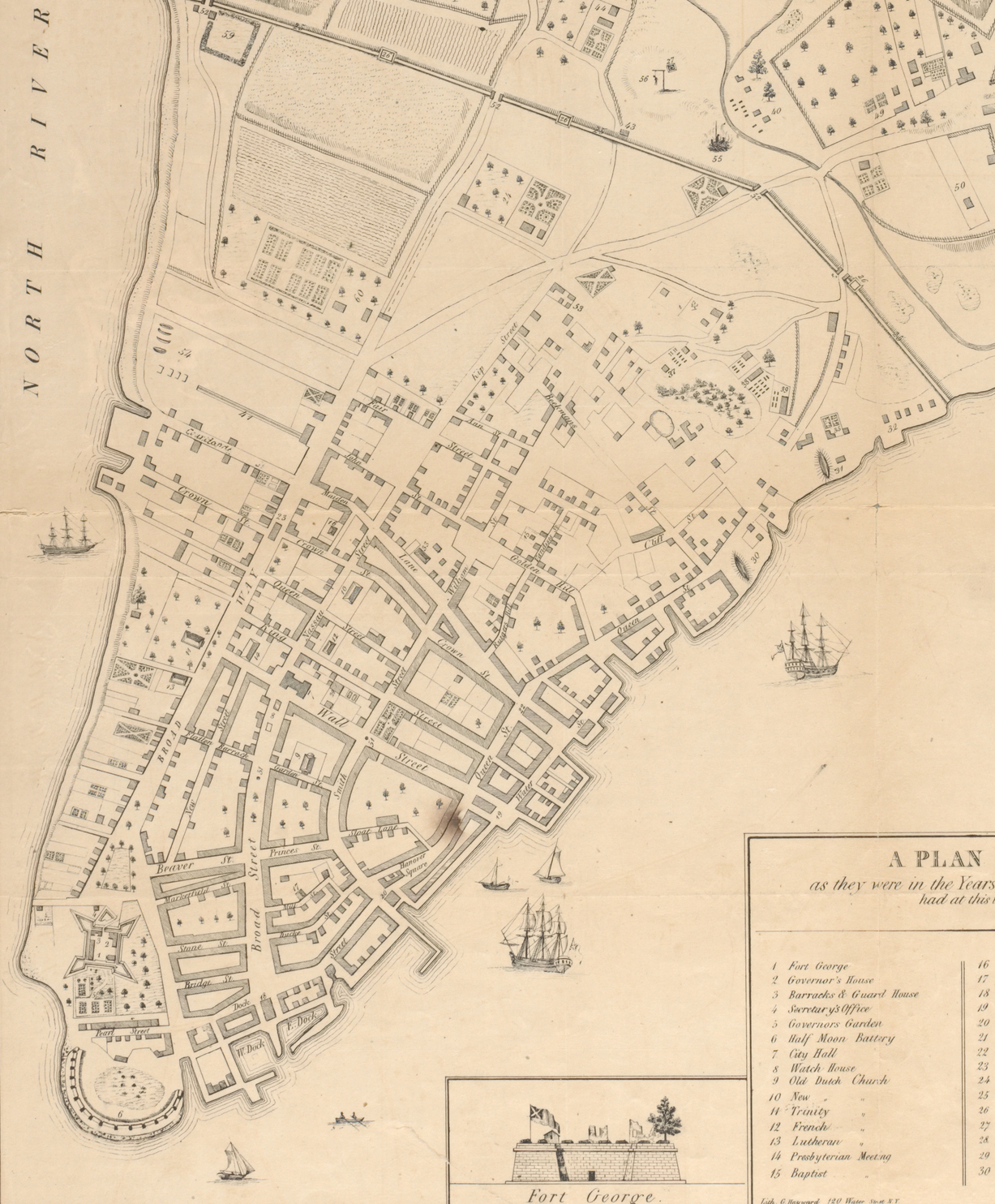

The Duke of York had no desire to govern locally or listen to the wishes of local colonists. It wasn’t until 1683, almost 20 years after the English took control of the colony, that colonists were able to convene a local representative legislature. The assembly enacted a Charter of Liberties and Privileges in 1683 that set out the traditional rights of Englishmen, like the right to trial by jury and the right to representative government; but New York society continued the Dutch patroonship system, granting large estates to a favored few families. The largest of these estates, at 160,000 acres (250 square miles), was given to a British aristocrat named Robert Livingston in 1686. The Livingstons and the other manorial families who controlled the Hudson River Valley married into Dutch patroon society and built a formidable political and economic force. Eighteenth-century New York City, meanwhile, contained a variety of people and religions including Dutch and English people, French Protestants (Huguenots), Jews, Puritans, Quakers, Anglicans, and a large population of slaves.

As they did in other regions, native peoples and slaves played important parts in shaping the history of colonial New York. After decades of war in the 1600s, the powerful Five Nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy, composed of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca) successfully pursued a policy of neutrality with both the English and the French to the north during the first half of the 1700s. This native diplomacy meant that the New York tribes continued to live in their own villages under their own government while enjoying the benefits of trade with both the French and the English. Slavery was also an important institution in the mid-Atlantic colonies. While New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania never developed plantation economies, enslaved people were often used on larger farms growing cereal grains. Enslaved Africans worked alongside European tenant farmers on New York’s Hudson Valley patroonships and New York City’s port where they worked in the maritime trades and domestic service. New York City’s economy was so reliant on slavery that over 40 percent of its population was enslaved by 1700, while 15 to 20 percent of Pennsylvania’s colonial population was enslaved by 1750. In New York, the high density of enslaved people heightened the fear of rebellion. A 1712 slave revolt in New York City resulted in the deaths of nine white colonists. In retribution, twenty-one enslaved people were executed and six others died by suicide before they could be burned alive.

The Restoration colonies also included Pennsylvania, which became the geographic center of British colonial America. Pennsylvania (“Penn’s Woods” in Latin) was created in 1681 when King Charles II bestowed the largest proprietary colony in the Americas on William Penn to settle a large political and financial debt he owed the Penn family. William Penn’s father, Admiral William Penn, had served the English crown by helping take Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655. The king personally owed the Admiral money as well.

Like early settlers of the New England colonies, many of Pennsylvania’s first colonists migrated for religious reasons. William Penn himself was a Quaker, a member of a new Protestant denomination, the Society of Friends, founded in the late 1640s. Quakers rejected the idea of worldly rank, believing instead in a new and radical form of social equality. Their speech reflected this belief in that they addressed all others as equals, using “thee” and “thou” rather than terms like “your lordship” or “my lady” that were customary for privileged individuals of the hereditary elite. Their rejection of inherited rank, however, did not prevent Quakers from seeking wealth and political power. The English crown had persecuted Quakers in England, and colonial governments such as Massachusetts had executed early Quakers who had gone to proselytize there. To avoid such persecution, Quakers created a community on the sugar island of Barbados. Soon after its founding, however, Pennsylvania became the destination of choice. Quakers flocked to Pennsylvania as well as New Jersey, where they could preach and practice their religion in peace. Unlike New England, whose official religion was Puritanism, Pennsylvania did not establish an official church. Indeed, the colony allowed a degree of religious tolerance that was rare in English America. To help encourage immigration to his colony, Penn promised a fifty acre “headright” to people who emigrated to Pennsylvania and completed their term of service. Not surprisingly, those seeking a better life came in large numbers, so much so that Pennsylvania relied on indentured servants more than any other colony.

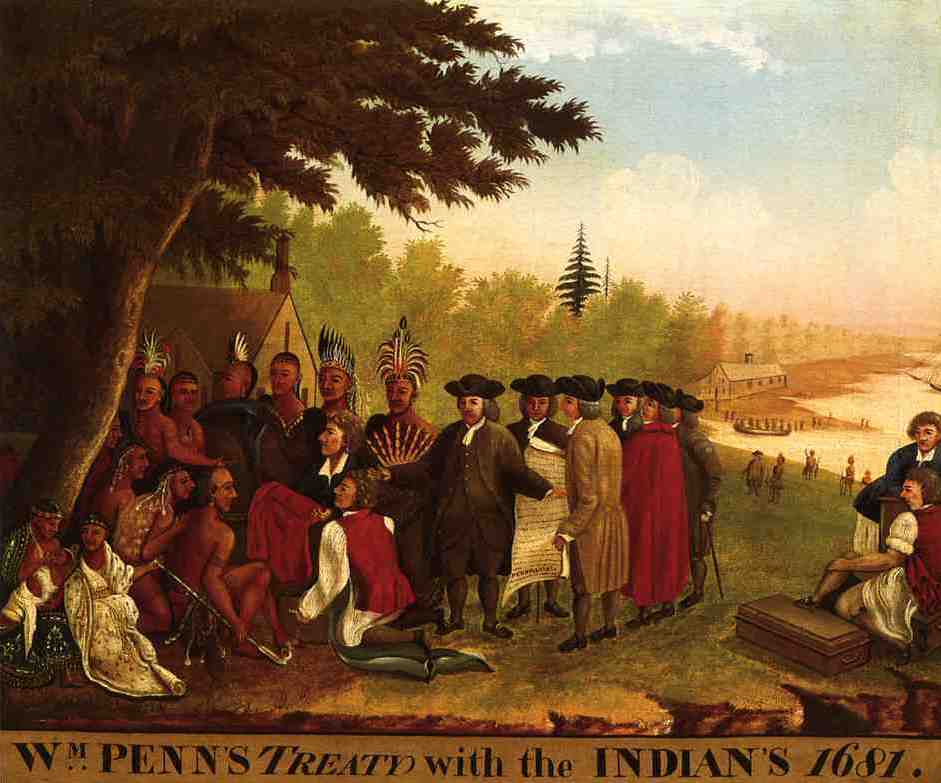

One of the primary tenets of Quakerism is pacifism, which led William Penn to establish friendly relationships with local native peoples. He formed a covenant of friendship with the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) tribe and signed a treaty with the Susquehannocks in 1701 to avoid war. Unlike other colonies, Pennsylvania did not experience war on the frontier with native peoples during its early history. As an important port city, Philadelphia grew rapidly. Despite their pacifism and egalitarian forms of speech, Quaker merchants were astute businessmen who established contacts throughout the Atlantic world and participated in the thriving African slave trade. Some Quakers, however, became troubled by the contradiction between their belief in the “inner light” and the practice of slavery. They rejected the practice and engaged in efforts to abolish it altogether. Philadelphia also acted as a magnet for immigrants, who came not only from England, but from all over Europe by the hundreds of thousands. The city and Pennsylvania appeared to offer the best opportunity for poor men and women, many of whom arrived as servants and dreamed of owning land. A few, like the fortunate Benjamin Franklin, a runaway from Puritan Boston, did extraordinarily well. Other immigrant groups in the colony, most notably Germans and Scotch-Irish (families from Scotland and northern England who had first lived in Ireland before moving to British America), greatly improved their lot in Pennsylvania. Of course, enslaved Africans imported into the colony to labor for white masters fared far worse.

JOHN WILSON OFFERS REWARD FOR ESCAPED PRISONERS

The American Weekly Mercury, published by William Bradford, was Philadelphia’s first newspaper. This advertisement from “John Wilson, Gaoler” (jailer) offers a reward for anyone capturing several men who escaped from the jail.

BROKE out of the Common Gaol of Philadelphia, the 15th of this Instant February, 1721, the following Persons:

John Palmer, also Plumly, alias Paine, Servant to Joseph Jones, run away and was lately taken up at New-York. He is fully described in the American Mercury, Novem. 23, 1721. He has a Cinnamon coloured Coat on, a middle sized fresh coloured Man. His Master will give a Pistole Reward to any who Shall Secure him, besides what is here offered.

Daniel Oughtopay, A Dutchman, aged about 24 Years, Servant to Dr. Johnston in Amboy. He is a thin Spare man, grey Drugget Waistcoat and Breeches and a light-coloured Coat on.

Ebenezor Mallary, a New-England, aged about 24 Years, is a middle-sized thin Man, having on a Snuff colour’d Coat, and ordinary Ticking Waistcoat and Breeches. He has dark brown strait Hair.

Matthew Dulany, an Irish Man, down-look’d Swarthy Complexion, and has on an Olive-coloured Cloth Coat and Waistcoat with Cloth Buttons.

John Flemming, an Irish Lad, aged about 18, belonging to Mr. Miranda, Merchant in this City. He has no Coat, a grey Drugget Waistcoat, and a narrow brim’d Hat on.

John Corbet, a Shropshire Man, a Runaway Servant from Alexander Faulkner of Maryland, broke out on the 12th Instant. He has got a double-breasted Sailor’s Jacket on lined with red Bays, pretends to be a Sailor, and once taught School at Josephs Collings’s in the Jerseys.

Whoever takes up and secures all, or any One of these Felons, shall have a Pistole Reward for each of them and reasonable Charges, paid them by John Wilson, Gaoler

—Advertisement from the American Weekly Mercury, 1722

Questions for Discussion

- How did English continuation of the Dutch patroon system in New York affect the colony’s history?

- Is it surprising to you that New York had a large enslaved population and constantly feared rebellion?

- How was Pennsylvania different from other colonies? How was it similar?

Creating wealth for the Empire remained a primary goal, and in the second half of the seventeenth century England attempted to gain better control of trade with its American colonies. The mercantilist policies the crown used to achieve this control are known as the Navigation Acts. The 1651 Navigation Ordinance, passed by Cromwell’s Commonwealth, required that only English ships could carry goods between England and the colonies. The ordinance further listed “enumerated articles” that could be transported only to England or to English colonies, including lucrative commodities like sugar, tobacco, indigo, rice, molasses, and naval stores such as turpentine. All were valuable goods not produced in England or in demand by the British navy. After ascending the throne, Charles II approved the 1660 Navigation Act, which restated the 1651 act to ensure a monopoly on imports from the colonies. Other Navigation Acts included the 1663 Staple Act and the 1673 Plantation Duties Act. The Staple Act barred colonists from importing goods that had not been made in England, creating a profitable monopoly for English exporters and manufacturers. The Plantation Duties Act taxed goods exported from one colony to another, a measure aimed principally at New Englanders, who exported food to the Caribbean sugar islands and imported great quantities of molasses to make rum. New England distillers also smuggled molasses they bought cheaply from French-held islands which were not allowed to distill their own spirits due to a law protecting France’s wine industry. Despite the Navigation Acts, Great Britain exercised lax control over the English colonies during most of the eighteenth century.

King James II, the second son of Charles I, ascended the English throne in 1685 after the death of his brother, Charles II. James worked to model his rule on the reign of the French Catholic King Louis XIV, his cousin. He centralized English political power around the throne, emulating the absolute monarchy his cousin enjoyed. Also like Louis XIV, James II was a Catholic and kept a standing army in times of peace that English Protestants believed would be used to crush their liberty. As James’s strength grew, his opponents feared their king would turn England into a Catholic monarchy with absolute power over her people. In 1686, James II applied his concept of a centralized state to the colonies by creating an enormous colony called the Dominion of New England. The Dominion included all the New England colonies (Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Plymouth, Connecticut, New Haven, and Rhode Island) and in 1688 was enlarged by the addition of New York and New Jersey. James placed in charge Sir Edmund Andros, a former colonial governor of New York. Loyal to James II and his family, Andros had little sympathy for New Englanders. His regime caused great uneasiness among New England Puritans when it called into question the many land titles that did not acknowledge the king and imposed fees for their reconfirmation. Andros also committed himself to enforcing the Navigation Acts, a move that threatened to disrupt the region’s trade, which was based largely on practices the Acts defined as smuggling.

In England, opponents of James II’s effort to create a centralized Catholic state were known as Whigs. The Whigs worked to depose James, and in late 1688 they succeeded in an event they celebrated as the Glorious Revolution. James fled to the court of Louis XIV in France while his daughter Mary and her husband William, Prince of Orange and elected ruler of the Protestant Dutch Republic, ascended the throne in 1689. The Glorious Revolution spilled over into the colonies. In 1689, Bostonians overthrew the Dominion of New England and jailed Sir Edmund Andros and other leaders of the regime. In New York, a German-born fur trader named Jacob Leisler led a group of Protestant New Yorkers against the dominion government. Acting on his own authority, Leisler assumed the role of King William’s governor and organized intercolonial military action independent of British authority. The government in London worried Leisler’s actions had usurped the crown’s prerogative and, as a result, he was tried for treason and executed. In 1691, England restored control over the Province of New York.

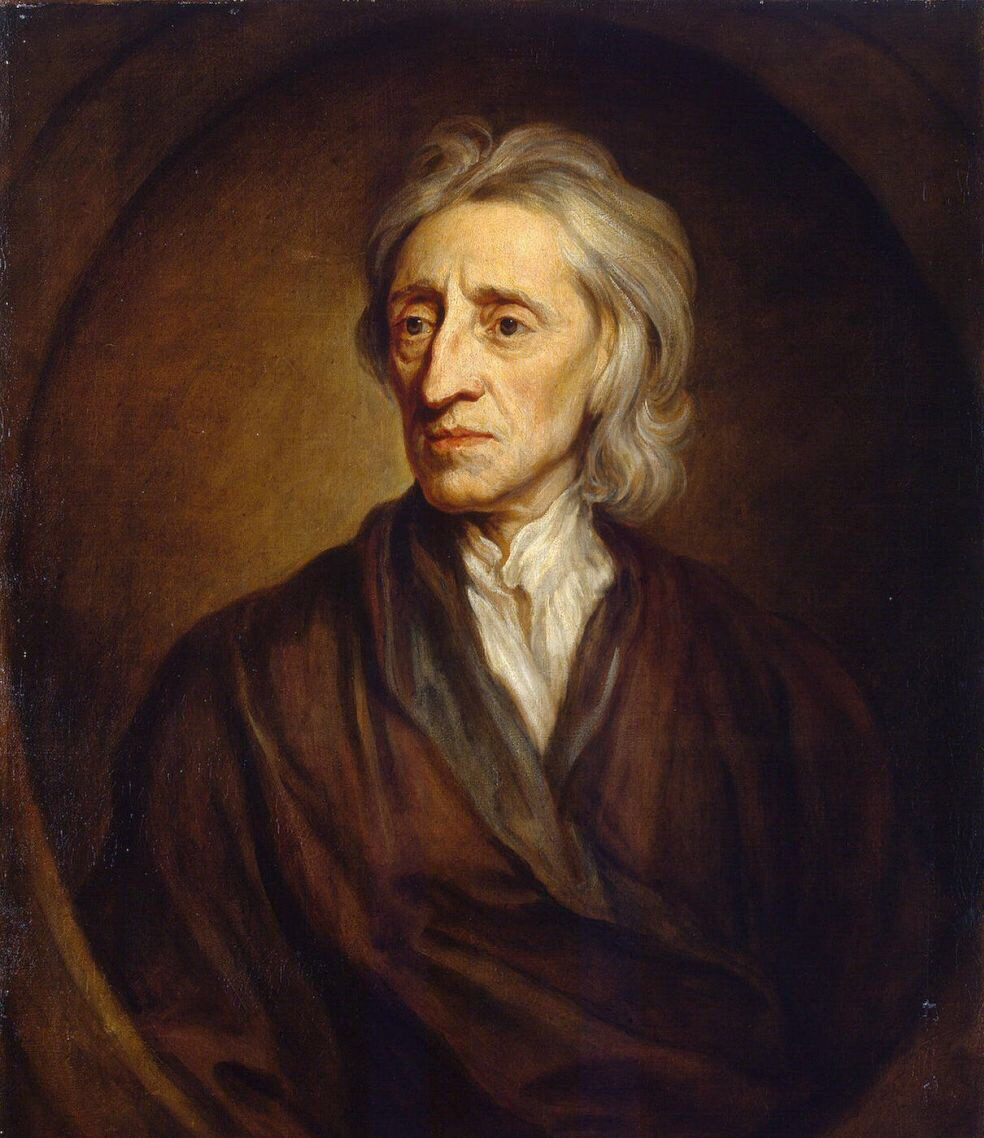

The Glorious Revolution led to the establishment of an English nation that limited the power of the king and provided protections for English subjects. England’s 1689 Bill of Rights established a constitutional monarchy, established Parliament’s independence from the monarchy, and protected rights such as freedom of speech, regular elections, and the right to petition the king. The 1689 Bill of Rights guaranteed certain rights to all English subjects including residents of the colonies, including trial by jury and habeas corpus (the requirement that authorities bring an imprisoned person before a court to demonstrate the cause of the imprisonment). John Locke (1632–1704), a doctor and educator who had taken refuge in Holland during the reign of James II and returned to England after the Glorious Revolution, published Two Treatises of Government in 1690. Locke argued that government was a social contract between leaders and the people, and that representative government existed to protect “life, liberty and property.” Locke rejected the divine right of kings and instead advocated for the central role of Parliament in a limited monarchy. Locke’s political philosophy had an enormous impact on future generations of colonists and established the paramount importance of representation in government.

Although Locke is most remembered for his writing on natural rights, he also wrote the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina in 1669, specifically protecting slavery in the new colony. The transport of slaves to the American colonies accelerated in the second half of the seventeenth century. In 1660, King Charles II created the Royal African Company to trade in slaves and African goods. His brother, James II, led the company before ascending the throne. The Royal African Company enjoyed a monopoly to transport slaves to the English colonies and between 1672 and 1713 the company bought 125,000 captives on the African coast. 25,000 died on the journey to the Caribbean and North America. The Royal African Company’s monopoly ended in 1689. Although the Glorious Revolution is typically seen as a triumph of liberty, after it many more English merchants engaged in the slave trade and the number of slaves transported increased dramatically. Although slaveholders took advantage of their captives’ differing languages and customs, many slaves adapted to their new lives by forming communities among themselves. Other Africans dealt with the trauma of their enslavement by actively resisting their condition, either by defying their masters or running away. Runaway slaves formed “maroon” communities that often successfully resisted recapture. The most prominent of these communities lived in the interior highlands of Jamaica, controlling the area and keeping the British away.

Slaves everywhere resisted their exploitation and many attempted to gain freedom in spite of brutal treatment. They understood that rebellion would bring massive retaliation from whites and had little chance of success. Even so, rebellions occurred frequently. An uprising that became known as the Stono Rebellion took place in South Carolina in September 1739. A literate slave named Jemmy led a large group of slaves in an armed insurrection against white colonists, killing several before militia stopped them. The whites suppressed the rebellion after a battle in which both slaves and militiamen were killed, and the remaining slaves were executed or sold to the West Indies. Jemmy and some of the other rebels are believed to have been from the Kingdom of Kongo, where the Africans were familiar with whites. If so, this common background may have made it easier for Jemmy to communicate with the other slaves in a region where blacks outnumbered whites, enabling them to work together to resist their enslavement even though slaveholders labored to keep slaves from forging such communities. In the wake of the Stono Rebellion, South Carolina passed a new slave code in 1740 called “An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes and Other Slaves in the Province”, also known as the Negro Act of 1740. This law imposed new limits on slaves’ behavior, prohibiting slaves from assembling, growing their own food, learning to write, and traveling freely.

In 1741, New York City authorities believed they had uncovered another planned rebellion by enslaved Africans and poor Black and white men. Tensions between property-owners and both slaves and the poor white population exploded when the city’s wealthier whites spread rumors that several suspicious fires were the early stages of a massive revolt in which slaves and poor free New Yorkers would murder whites, burn the city, and take over the colony. The Stono Rebellion was a recent memory, and throughout British America fears of similar incidents were still fresh. Searching for solutions, and convinced slaves were the principal danger, alarmed British authorities violently interrogated almost two hundred slaves accused of conspiracy. After a quick series of trials at City Hall, the government executed seventeen New Yorkers. Thirteen black men were publicly burned at the stake, while the others (including four whites) were hanged. Six people killed themselves to avoid being burned alive. Seventy slaves were sold to the West Indies. Little evidence exists to prove that the elaborate conspiracy white New Yorkers imagined actually existed.

British Americans’ reliance on indentured servitude and slavery to meet the demand for colonial labor helped create a wealthy colonial class in the Chesapeake tobacco colonies and elsewhere. The British-American gentry modeled themselves on the English aristocracy, who embodied the ideals of refinement and gentility. They built elaborate mansions to advertise their status and power. William Byrd II of Westover, Virginia, exemplifies the colonial gentry; a wealthy planter and slaveholder, he is known for founding Richmond and for his diaries documenting the life of a gentleman planter.

WILLIAM BYRD’S DIARY

August 27, 1709

I rose at 5 o’clock and read two chapters in Hebrew and some Greek in Josephus. I said my prayers and ate milk for breakfast. I danced my dance. I had like to have whipped my maid Anaka for her laziness but I forgave her. I read a little geometry. I denied my man G-r-l to go to a horse race because there was nothing but swearing and drinking there. I ate roast mutton for dinner. In the afternoon I played at piquet with my own wife and made her out of humor by cheating her. I read some Greek in Homer. Then I walked about the plantation. I lent John H-ch £7 [7 English pounds] in his distress. I said my prayers and had good health, good thoughts, and good humor, thanks be to God Almighty.

September 6, 1709

About one o’clock this morning my wife was happily delivered of a son, thanks be to God Almighty. I was awake in a blink and rose and my cousin Harrison met me on the stairs and told me it was a boy. We drank some French wine and went to bed again and rose at 7 o’clock. I read a chapter in Hebrew and then drank chocolate with the women for breakfast. I returned God humble thanks for so great a blessing and recommended my young son to His divine protection.

Questions for Discussion

- How did the British use the Navigation Acts to get the most value they could from their colonies?

- What does New York’s reaction to rumors of a possible revolt of slaves and poor free people reveal about the society?

The Enlightenment, also called the Age of Reason, was an intellectual and cultural movement in the eighteenth century that emphasized reason over superstition and scientific empiricism over blind faith. Using the power of the press, Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke, Isaac Newton, and Voltaire questioned accepted knowledge and spread new ideas about openness, investigation, and religious tolerance throughout Europe and the Americas. Enlightenment ideas included rationalism, empiricism, progressivism, and cosmopolitanism. Rationalism is the idea that humans are capable of using their faculty of reason to gain knowledge; a sharp turn away from the prevailing idea that people needed to rely on scripture or church authorities for knowledge. Empiricism promotes the idea that knowledge comes from experience and observation of the world. Progressivism is the belief that through their powers of reason and observation, humans could make progress over time. Belief in the possibility of social progress was especially important after the carnage and upheaval of European religious wars and the English Civil Wars in the seventeenth century. Finally, cosmopolitanism reflected Enlightenment thinkers’ view of themselves as citizens of the world and actively engaged in it, as opposed to being provincial, close-minded, and ruled by prejudice.

The Englishman Thomas Paine and the American Benjamin Franklin are often thought of as representatives or embodiments of the Enlightenment in British America. Franklin was born in Boston in 1706 to a large Puritan family and went to work as apprentice to his older brother in a print shop, where he improved his writing by copying the style of the London Spectator, which his brother printed. At the age of seventeen, the rebellious Franklin ran away to Quaker Philadelphia. There he began publishing the Pennsylvania Gazette in the late 1720s, and in 1732 he started his annual publication Poor Richard: An Almanack. Franklin gave readers practical advice such as, “Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.” Thomas Paine, about two decades younger than Franklin, grew up in England and worked as an excise (tax) officer and political pamphleteer before being introduced to Franklin in London. Franklin encouraged Paine to emigrate to America and wrote him a letter of introduction. Paine moved to Philadelphia and became editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine in 1775, just in time to participate in the America’s movement toward independence.

Franklin and Paine both rejected organized religion, preferring deism, an Enlightenment-era belief in an impersonal God who may have created but had no continuing involvement with the world and the events within it. Deists held that personal morality was more important than strict church doctrines. Franklin’s deism guided many philanthropic projects. In 1731, he established a reading library that became the Library Company of Philadelphia. In 1743, he founded the American Philosophical Society to encourage the spirit of inquiry. In 1749, Franklin provided the foundation for the University of Pennsylvania, and in 1751, he helped found Pennsylvania Hospital. Paine’s Deism drove him to support the American Revolution and later the French Revolution and to attack state religion in books like The Age of Reason.

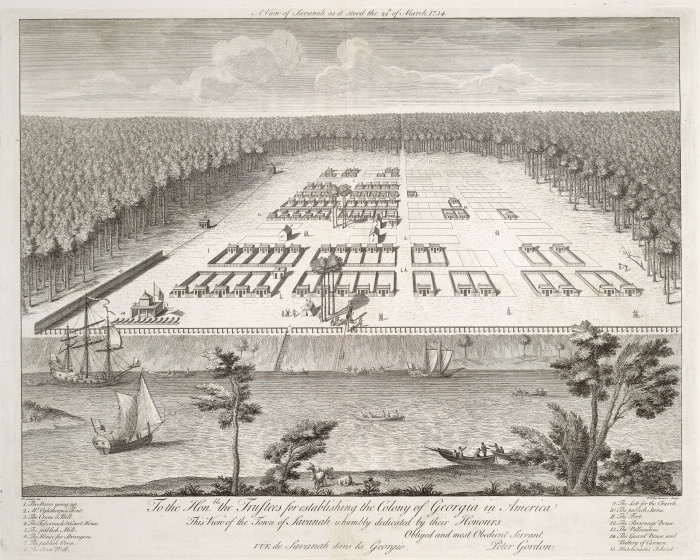

The reach of Enlightenment thought even prompted the founding of a new colony. Having witnessed the terrible conditions of debtors’ prisons and poverty of the streets of London, James Oglethorpe, a member of Parliament and advocate of social reform, petitioned King George II for a charter to start a new colony. The king understood the strategic advantage of a British colony positioned as a buffer between South Carolina and Spanish Florida, and granted a charter to Oglethorpe and twenty like-minded proprietors in 1732. Oglethorpe led the settlement of the colony, which was called Georgia in honor of the king. In 1733, he and 113 immigrants arrived and over the next decade, Parliament funded the migration of twenty-five hundred settlers, making Georgia the only government-funded colonial project. Oglethorpe’s vision for Georgia followed the ideals of the Enlightenment: he saw the colony as a place for England’s “worthy poor” to start anew. To encourage industry, he gave each male immigrant fifty acres of land, tools, and a year’s worth of supplies. In Savannah, the Oglethorpe Plan provided for a utopia: “an agrarian model of sustenance while sustaining egalitarian values holding all men as equal.” Oglethorpe’s vision of a just society ruled out alcohol and slavery. However, settlers who migrated into Georgia from South Carolina disregarded these prohibitions. Despite its proprietors’ early vision of a colony guided by Enlightenment ideals and free of slavery, by the 1750s, Georgia was shipping rice into the Atlantic commercial market grown and harvested by slaves.

Questions for Discussion

- Was the Deism of people like Franklin and Paine a positive or negative influence on their actions?

- How might history have been different if Oglethorpe’s idealistic vision for Georgia had succeeded?

The British colonies grew during a time when much of North America, especially the Northeast, engaged in frequent war. Generations of colonial families knew battle firsthand. In the eighteenth century, fighting was seasonal. Armies mobilized in the spring, fought in the summer, and retired to winter quarters in the fall. The British army imposed harsh discipline on its soldiers, who were drawn from the poorer classes, to ensure they did not step out of line during engagements. If they did, their officers would kill them. On the battlefield, armies dressed in bright uniforms to advertise their lack of fear. They stood in tight formation and exchanged volleys of close-range musket-fire with the enemy. In reality, troops often feared their officers more than the enemy.

Most imperial conflicts had both American and European fronts, leaving history with two or more names for each war. For instance, King William’s War (1688–1697) is also known as the War of the League of Augsburg. In America, the bulk of the fighting in this conflict took place between New England and New France. Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713) is also known as the War of Spanish Succession. England fought against both Spain and France over who would inherit the Spanish throne after the last Hapsburg ruler died. In North America, fighting took place in Florida, New England, and New France. In Canada, the French prevailed but lost Acadia and Newfoundland. The English failed to take Quebec, which would have given them complete control of Canada. Queen Anne’s War is best remembered in the United States for the French and Indian raid against Deerfield, Massachusetts, in 1704. A small French force, combined with a native group made up of Catholic Mohawks and Pocumtucs, attacked the frontier village of Deerfield, killing scores and taking 112 prisoners. Among the captives was the seven-year-old daughter of Deerfield’s minister John Williams, named Eunice. She lived with the Mohawks for years as her family tried to ransom her and became assimilated into the tribe. To the horror of the Puritan leaders, when she grew up Eunice married a Mohawk man and refused to return to New England.

Possession of Georgia and trade with the interior was the focus of the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739–1742), a conflict between Britain and Spain over claims to the land occupied by the fledgling Georgia colony between South Carolina and Florida. King George’s War (1744–1748), known in Europe as the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748), was fought in the northern colonies and New France. In 1745, the British took the massive French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. However, three years later, under the terms of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, Britain relinquished control of the fortress to the French.

The final imperial war, the French and Indian War (1754–1763), known as the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) in Europe, was the decisive contest between Britain and France in America. It began over rival claims along the frontier in present-day western Pennsylvania. Well-connected planters from Virginia (including a young George Washington) faced stagnant tobacco prices and hoped speculating in land on the western frontier would stabilize their wealth and status. They established the Ohio Company of Virginia in 1748, and the British crown granted the company half a million acres in 1749. However, the French also claimed the lands granted to the Ohio Company, and to protect the region they established Fort Duquesne in 1754, where the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers met to form the Ohio River.

Twenty-two-year-old Virginian George Washington, a planter’s son whose family had helped start the Ohio Company, apparently started the war with a command to his men to fire on French soldiers near present-day Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Fighting broke out along the frontier of New France and British America from Virginia to Maine. The war also spread to Europe and Asia as France and Britain fought to gain supremacy for their empires. The British fought poorly in the first years of the war and in 1754 the French and their native allies forced Washington to surrender at Fort Necessity, a hastily built fort constructed after his attack on the French. In 1755, Britain dispatched General Edward Braddock to the colonies to take Fort Duquesne. The French, aided by the Potawotomis, Ottawas, Shawnees, and Delawares, ambushed fifteen hundred British soldiers and Virginia militia as they marched toward the fort. The attack killed hundreds of Virginia militiamen and British soldiers, including General Braddock. The only British victory in 1755 was the capture of Nova Scotia. In 1756 and 1757, Britain suffered further defeats with the fall of Fort Oswego and Fort William Henry.

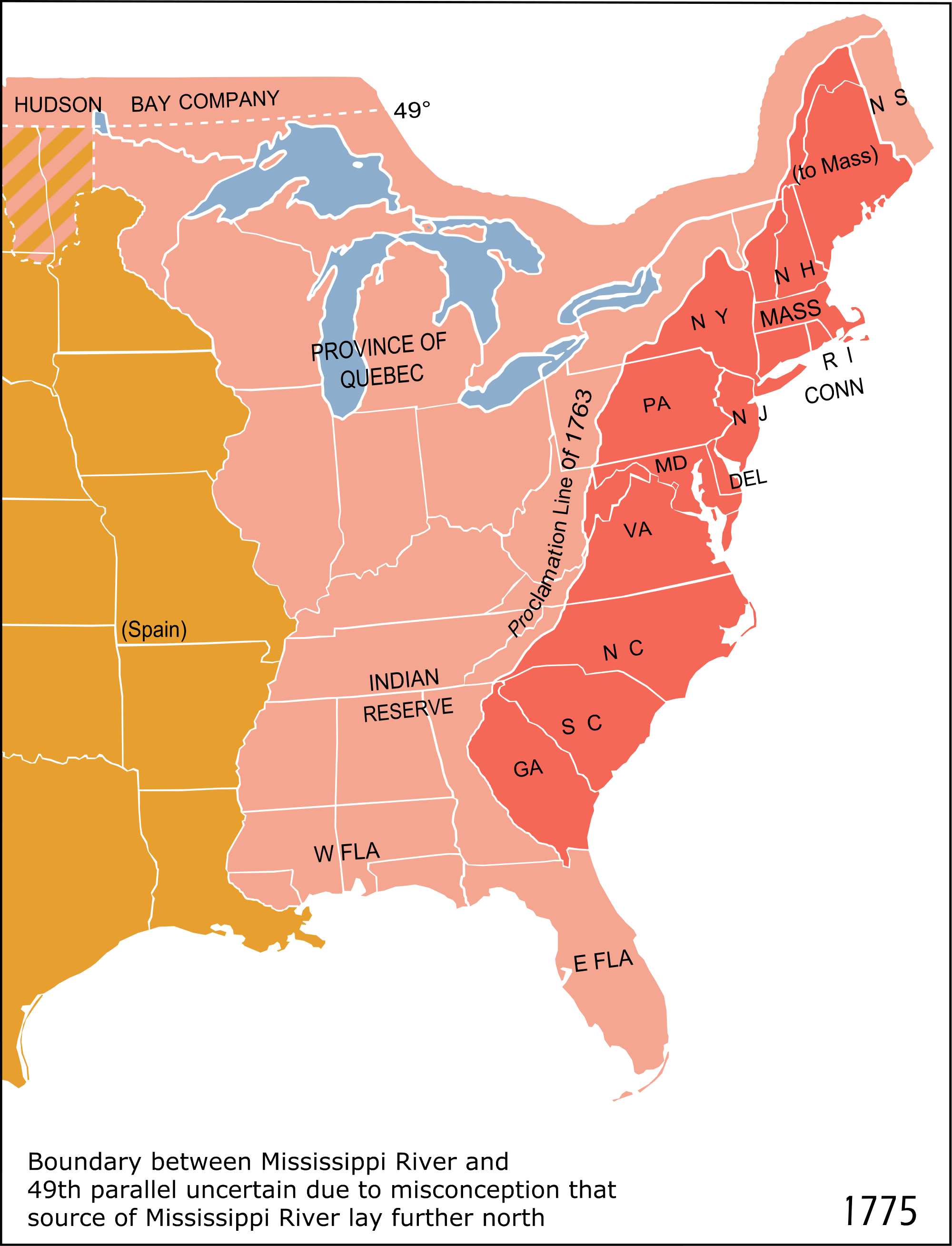

The war began to turn in favor of the British in 1758, due in large part to the efforts of William Pitt, a very popular member of Parliament. Pitt pledged huge sums of money and resources to defeating the French and Great Britain spent part of the money on bounties paid to new recruits in the colonies, helping invigorate the British forces. In 1758, the Iroquois, Delaware, and Shawnee signed the Treaty of Easton, aligning themselves with the British in return for some contested land around Pennsylvania and Virginia. In 1759, the British took Quebec, and in 1760, Montreal. The French empire in North America crumbled, but the war continued until 1763 when the French signed the Treaty of Paris. New France ceased to exist and the British Empire gained control over North America. The Empire not only gained New France under the treaty; it also acquired French sugar islands in the West Indies, French trading posts in India, and French-held outposts on the west coast of Africa. The English victory in the French and Indian War made Great Britain a truly global empire. Fort Duquesne, on the western frontier, was renamed Fort Pitt (later Pittsburgh) after the war’s champion in Parliament.

In the American colonies, ties with Great Britain were closer than ever. Professional British soldiers had fought alongside Anglo-American militiamen, creating a greater sense of shared identity. Colonial pride ran high as colonists sang “Rule, Britannia” and celebrated their identity as British subjects. Despite the celebratory mood, however, the victory over France produced massive war debt that became a serious problem for Parliament. The frontier had to be secure in order to prevent another costly war. Greater enforcement of imperial trade laws had to be put into place. Parliament had to raise revenue to pay for the war. Everyone was expected to contribute their share, including British subjects across the Atlantic. British territorial holdings now extended from Canada to Florida, and Britain’s military focus shifted to maintaining peace in the king’s newly enlarged lands. However, much of the land in the American British Empire remained under the control of powerful native confederacies, which made claims of British dominion beyond the Atlantic coastal settlements hollow.

Great Britain quartered ten thousand troops in North America after the war ended in 1763 to defend the borders and repel any attack by their imperial rivals. British colonists, eager for fresh land, poured over the Appalachian Mountains to stake claims. The western frontier had long been a “middle ground” where different imperial powers (British, French, Spanish) had interacted and compromised with native peoples. That era of accommodation in the “middle ground” came to an end after the French and Indian War. Virginians (including George Washington) and other land-hungry colonists had already raised tensions in the 1740s with their quest for land. Virginia landowners eagerly looked to diversify their holdings beyond tobacco, which had stagnated in price and had exhausted the fertility of the lands along Chesapeake Bay. They invested heavily in the newly available land.

This explosion of westward settlement brought the colonists into conflict as never before with Indian tribes like the Shawnee, Seneca-Cayuga, Wyandot, and Delaware, who were increasingly willing to fight to hold their ground against any further intrusion by white settlers. The treaty that ended the war between France and Great Britain was a disastrous blow to native peoples. With the French defeat, tribes who had sided with France lost an ally and trading partner as well as bargaining power over the British. After the war, British troops took over the former French forts but failed to court favor with the local tribes by distributing gifts as the French had done. They also significantly reduced the amount of gunpowder and ammunition they sold to the Indians, worsening relationships further.

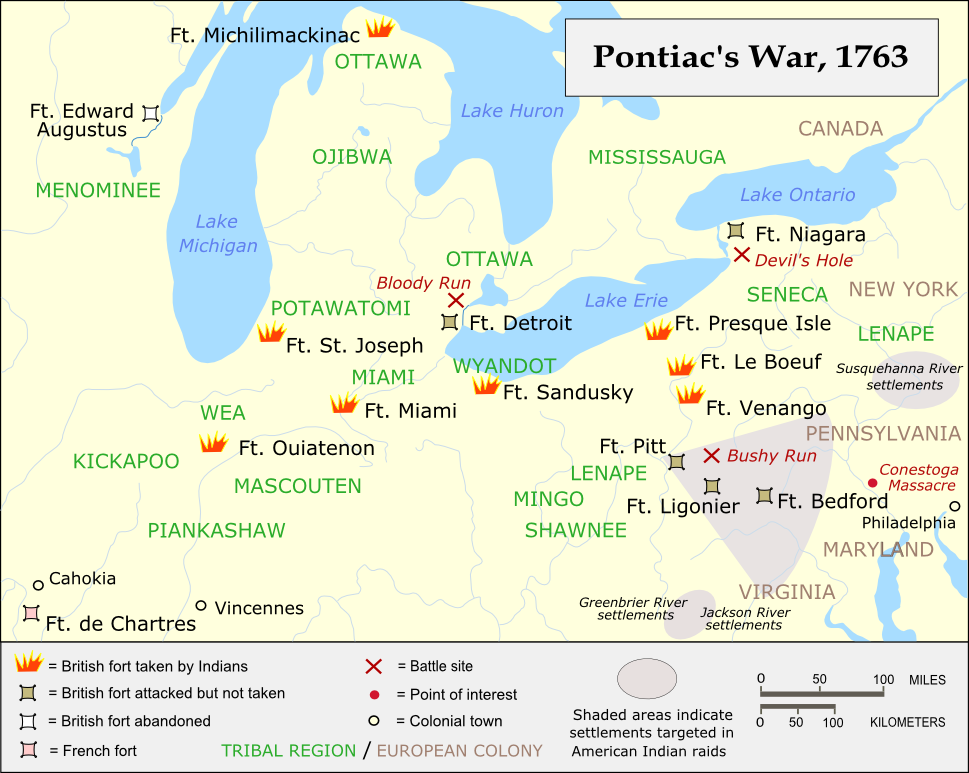

Indian resistance to colonists grew around the teachings of Delaware prophet Neolin and the leadership of Ottawa war chief Pontiac. Neolin preached a doctrine of shunning European culture and expelling Europeans from native lands. Pontiac echoed this idea, exhorting tribes to join together against the British: “It is important for us, my brothers, that we exterminate from our lands this nation which seeks only to destroy us.” In a broad-based alliance that came to be known as Pontiac’s Rebellion, the Ottawa warrior led a loose coalition of tribes against the colonists and the British army. The conflict began in 1763, when Pontiac and several hundred Ojibwas, Potawatomis, and Hurons laid siege to Fort Detroit while Senecas, Shawnees, and Delawares besieged Fort Pitt. Over the next year, the war spread along the backcountry from Virginia to Pennsylvania. Pontiac’s Rebellion triggered horrific violence on both sides. Stories of brutal attacks incited a deep racial hatred in the colonists against all Indians.

The actions of a group of settlers from Paxton, Pennsylvania, in December 1763, illustrates the deadly effects of white hatred of all Indians. A mob of Scots-Irish frontiersmen known as the Paxton Boys attacked a nearby village of Conestoga Indians of the Susquehannock tribe. The Conestoga had lived peacefully with local settlers, but the Paxton Boys viewed all Indians as savages and they brutally murdered six Indians and burned their homes. When Governor John Penn put the remaining fourteen Conestoga in protective custody in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the Paxton Boys broke into the building and killed and scalped all the Indians they found there. Although Governor Penn offered a reward for the capture of any Paxton Boys involved in the murders, no one ever identified the attackers. Some colonists reacted to the incident with outrage. Benjamin Franklin warned that “the Wickedness cannot be covered, the Guilt will lie on the whole Land, till Justice is done on the Murderers. The blood of the innocent will cry to heaven for vengeance.” Yet, as the inability to bring the perpetrators to justice clearly indicates, the Paxton Boys had many more supporters than critics.

Pontiac’s Rebellion and the Paxton Boys’ actions were examples of early American race wars, in which both sides saw themselves as inherently different from the other and believed the other needed to be eradicated. But the response of the Indians defending their homeland from invaders should not be equated with the attitudes of the British, who regarded the natives as a lesser race to be moved out of the way of progress. In a letter suggesting “gifts” to the natives of smallpox-infected blankets, British Field Marshal Jeffrey Amherst instructed one of his Colonels, “You will do well to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race.” Amherst, who gave his name to several towns and a college in New England, was ennobled by the British crown and became the first Baron Amherst. Pontiac’s Rebellion came to an end in 1766, when it became clear that the French, whom Pontiac had hoped would side with his forces, would not be returning to the fight. The repercussions, however, would last much longer. Race relations between Indians and whites remained poisoned on the frontier.

Well aware of the problems on the frontier, the British government took steps to try to prevent another costly war.

Questions for Discussion

- Why were European imperial conflicts often fought on American soil?

- How did Britain’s defeat of France in the Seven Years War affect Indians?

At the beginning of Pontiac’s uprising, the British issued the Proclamation of 1763, forbidding white settlement west of a borderline running along the spine of the Appalachian Mountains. Setting the Proclamation Line was an attempt to forestall further conflict on the frontier but British colonists who had hoped to move west objected to this restriction. The Americans believed they had just fought and won a war to ensure their right to settle the west. The Proclamation Line was a barrier to both the settlers’ and the land speculators’ visions of profits from westward expansion.

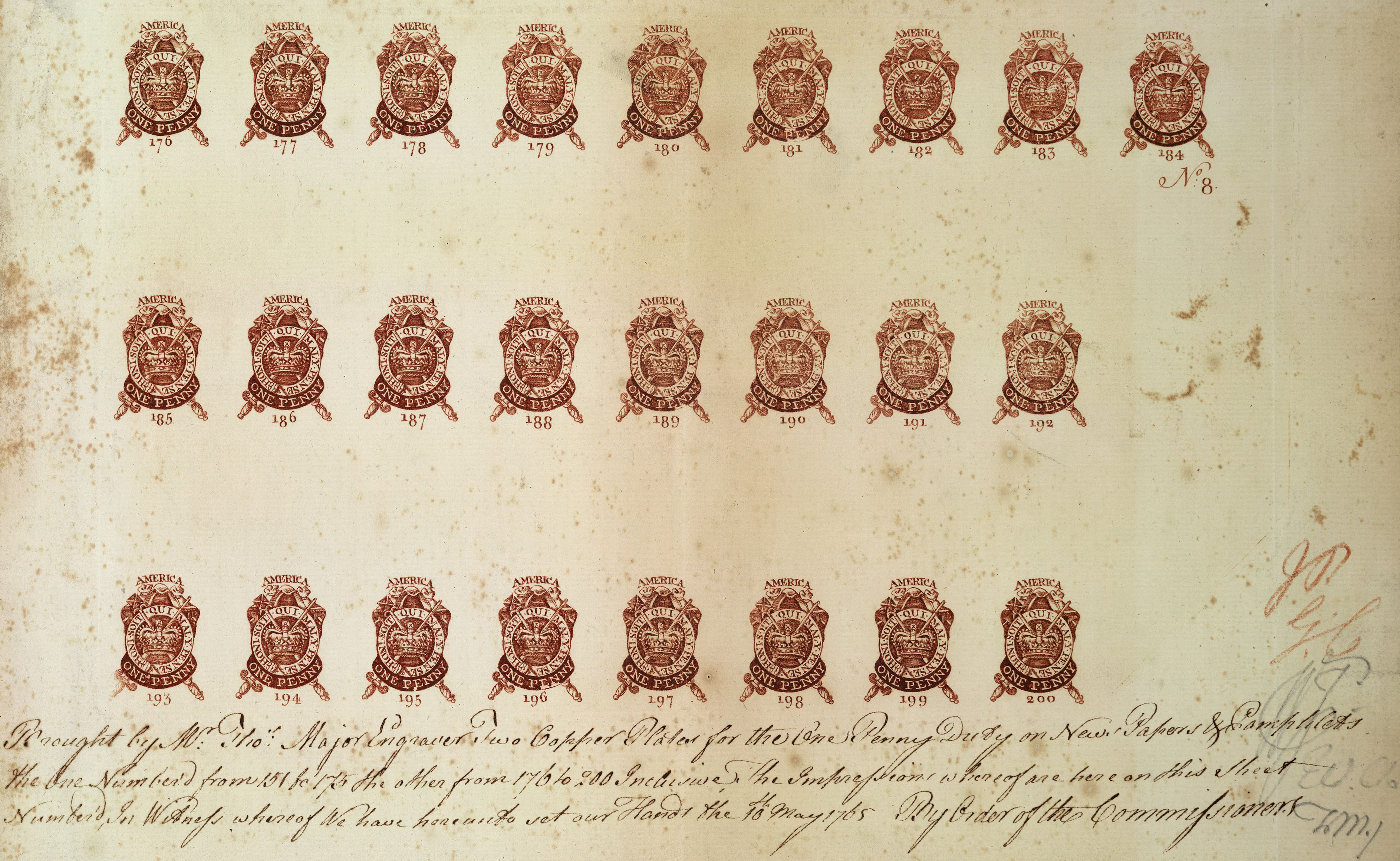

Great Britain’s newly-enlarged empire came with a price-tag that nearly doubled the British national debt from £75 million in 1756 to £133 million in 1763. Interest payments alone consumed over half the national budget, and the ongoing military presence in North America was a constant financial drain. The Empire needed more revenue and members of Parliament in Great Britain believed British subjects in North America should certainly shoulder their share of the financial burden. The British government began increasing revenues by raising taxes, even as interest groups at home lobbied to keep their own taxes low. Powerful aristocrats, well represented in Parliament, successfully prevented the government raising taxes on land. The new tax burden, instead, fell on the lower classes in the form of increased duties that raised the prices of imports like sugar and tobacco. A new Whig government under Prime Minister George Grenville promised to rein in government spending and make sure the American colonists did their part to pay down the massive debt. Grenville introduced the Currency Act of 1764, prohibiting the colonies from printing their own paper money and bringing American economic activity under greater British control. Grenville also pushed Parliament to pass the Sugar Act of 1764, which actually lowered duties on British molasses by half, from six pence per gallon to three, but which required violators of the Navigation Acts to be tried in vice-admiralty courts, tribunals that operated without juries. Some colonists argued that trial by jury had long been honored as a basic right of Englishmen. Depriving defendants of a jury, they contended, meant reducing liberty-loving British subjects to political slavery. To make their arguments seem more dramatic, some colonists equated this loss of liberty to the enslavement of Africans.

Parliament was in charge of taxation, and although it was a representative body, the colonies did not have direct representation in it. Protesters viewed themselves as having the same right as all British subjects to avoid taxation without their consent. The colonists ignored the fact that if they had been represented in the House of Commons, their representatives would not have been able to prevent the imposition of these new taxes. But for the British government, the colonists’ objections were beside the point. Parliament believed the relationship of the colonies to the Empire was one of dependence, not equality. The Stamp and Quartering Acts had the unintended consequence of drawing colonists from very different areas and viewpoints together in protest. In Massachusetts, for instance, James Otis, a lawyer and defender of British liberty, became the leading voice for the idea that “Taxation without representation is tyranny.” In the Virginia House of Burgesses, slaveholder Patrick Henry introduced the Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions, which denounced the Stamp Act and the British crown in language so strong that some conservative Virginians accused him of treason. And although the Stamp Act taxed documents and most impacted publishers, lawyers, and other professionals, the Quartering act affected people of all classes and turned the British troops that had recently been brothers in arms to the colonists into an expensive imposition.

The residents of Britain’s thirteen colonies had never before formed a unified political front, so Grenville and Parliament did not consider them capable of acting together. However, in response to the Stamp Act, the Massachusetts Assembly sent letters to the other colonies asking them to send delegates to a congress. Many American colonists from very different colonies found common cause in their opposition to the Stamp Act. Representatives from nine colonial legislatures met in New York in the fall of 1765 to reach a consensus. The Congress drafted a rebuttal to the Stamp Act, making clear that they desired only to protect their liberty as loyal subjects of the Crown. The document, called the “Declaration of Rights and Grievances”, outlined the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation and trials without juries. Meanwhile, popular protest was also gaining force.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did colonists object tot he Proclamation Line?

- Do you think the colonists were justified in objecting to pay 17% of the cost of the soldiers protecting the colonies?

The Stamp Act Congress was a gathering of landowning, educated white men who represented the social and political elites of the colonies; the colonial equivalent of the British aristocracy. While these gentlemen were drafting their grievances during the Stamp Act Congress, other colonists showed their distaste for the new act by boycotting British goods and protesting in the streets. Two groups, the Sons of Liberty and the Daughters of Liberty, led the popular resistance to the Stamp Act. Forming in Boston in the summer of 1765, the Sons of Liberty were artisans, shopkeepers, and merchants. Although the group’s members were common people, many of its leaders were lawyers like James Otis and Patrick Henry, doctors like Joseph Warren and Thomas Young, or businessmen like Benedict Arnold and John Hancock who were apparently not above encouraging their group to violent protest. Before the Stamp Act even went into effect, the Sons of Liberty began protesting. On August 14, they took aim at Andrew Oliver, who had been named the Massachusetts Distributor of Stamps. After hanging Oliver in effigy, the unruly crowd stoned and ransacked his house, then beheaded the effigy and burned the remains. Andrew Oliver resigned the next day. By that time, the mob had surrounded the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson, barricaded Hutchinson in his home and demanded that he renounce the Stamp Act. When Hutchinson refused the protesters looted and burned his house. The Sons of Liberty continued to lead violent protests with the goal of forcing the resignation of all appointed stamp collectors.

Formed in early 1766, the Daughters of Liberty took a less violent path. They protested the Stamp Act by refusing to buy British goods and boycotting British tea, opting to make their own teas with local herbs and berries. Well-born women held “spinning bees,” at which they competed to see who could produce the most homespun linen. The Daughters’ non-importation movement broadened the protest against the Stamp Act, giving women a new, active role in the political dissent of the time. Although women could not vote or hold official positions, they could vote with their purses, mobilize others, and make a difference in the political landscape. The Sons and Daughters of Liberty spread rapidly until there was a chapter in every colony. The Daughters of Liberty promoted the boycott on British goods while the Sons enforced it, threatening retaliation against anyone who bought imported goods or used stamped paper. In the protest against the Stamp Act, wealthy political figures like attorney John Adams supported the goals of the Sons and Daughters of Liberty, even if they did not engage in the Sons’ violent actions. Lawyers, printers, and merchants ran a propaganda campaign parallel to the Sons’ campaign of violence. In newspapers and pamphlets throughout the colonies, they published the reasons the Stamp Act was unconstitutional and urged peaceful protest. The colonial elites officially condemned violent actions but did not have the protesters arrested; a degree of cooperation prevailed, despite the groups’ different economic backgrounds.

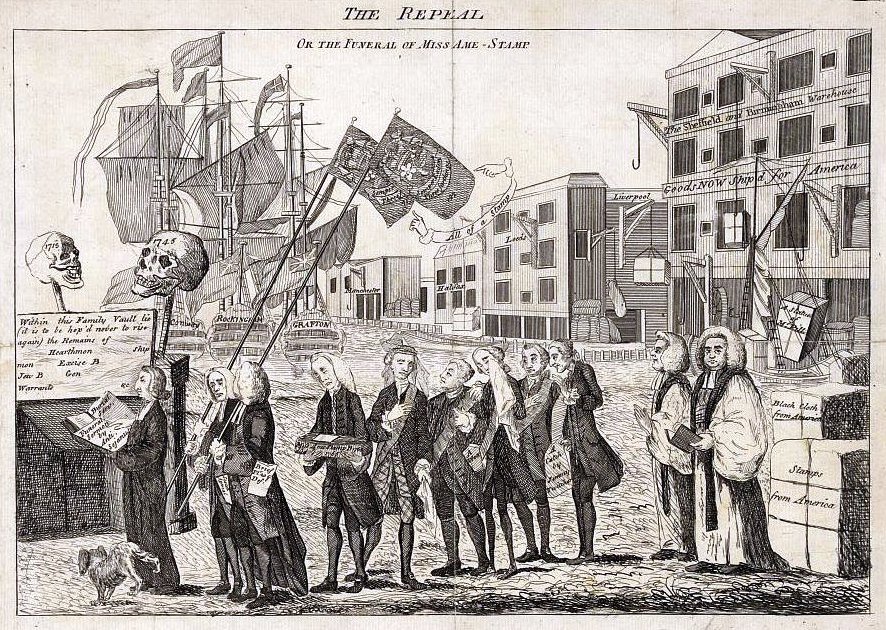

In Great Britain, news of the colonists’ reactions to the new laws worsened an already volatile political situation. Grenville’s imperial reforms had already increased domestic taxes and his unpopularity led to his dismissal by King George III. While many in Parliament still wanted such reforms, British merchants argued for their repeal. Non-importation of British goods by North American colonists was hurting their business. In March 1766, the new prime minister, Lord Rockingham, forced Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. Colonists celebrated what they saw as a victory for their British liberty; in Boston, merchant John Hancock treated the entire town to drinks. However, to appease those who feared the repeal would weaken parliamentary power over the American colonists, Rockingham also proposed the Declaratory Act which stated that Parliament’s power was supreme and that any laws the colonies may have passed to govern and tax themselves were null and void if they ran counter to parliamentary law.

Lord Rockingham’s tenure as prime minister only lasted a year. British landowners feared that if he did not raise enough revenue in the colonies, Parliament would raise their taxes instead. His successor, William Pitt, was sympathetic to the colonists but old and ill. Pitt’s chancellor of the exchequer, Charles Townshend, took on the duty of raising the needed revenue from the colonies. Townshend proposed the Restraining Act of 1767, which disbanded the New York Assembly that had voted not to pay for the garrison of British soldiers until it agreed to obey the Quartering Act’s requirements. The Townshend Revenue Act of 1767 placed duties on consumer items like paper, paint, lead, tea, and glass that the colonies did not manufacture themselves. The Indemnity Act of 1767 exempted tea produced by the British East India Company from taxation when it was imported into Great Britain. When the tea was re-exported to the colonies, however, the colonists had to pay taxes on it because of the Revenue Act. Critics of Parliament on both sides of the Atlantic saw this tax policy as an example of corrupt politicians giving preferable treatment to specific corporate interests, creating a monopoly.

To ensure compliance with his Revenue Act, Townshend introduced the Commissioners of Customs Act of 1767, which created an American Board of Customs to enforce trade laws. Customs enforcement had been based in Great Britain, but rules were difficult to implement at such a distance and smuggling was rampant. The new customs board was based in Boston and severely curtailed smuggling. Townshend also orchestrated the Vice-Admiralty Court Act, which established three more vice-admiralty courts, in Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston, to try violators of customs regulations without a jury. Since the judges of these courts were paid a percentage of the value of the goods they recovered, leniency was rare.

The Townshend Acts resulted in higher taxes and stronger British power to enforce them. Like the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts triggered protest in the American colonies. For a second time, many colonists objected to being taxed without representation and deprived of their liberty. The fact that the revenue the Townshend Acts raised would pay royal governors only made the situation worse, because it took control away from colonial legislatures that otherwise had the power to set and withhold a royal governor’s salary. The Restraining Act, which had been intended to isolate New York without angering the other colonies, had the opposite effect, showing the rest of the colonies how far beyond the British Constitution some members of Parliament were willing to go. The Townshend Acts generated a number of protest publications. In 1768, Boston businessman Samuel Adams wrote a letter that became known as the ”Massachusetts Circular”. Sent by the Massachusetts House of Representatives to the other colonial legislatures, the letter laid out the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation and encouraged the other colonies to again protest the taxes by boycotting British goods.

Great Britain’s response to Adams’s mild threat of disobedience served only to unite the colonies further. The secretary of state for the colonies demanded that Massachusetts retract the letter, promising that any colonial assemblies that endorsed it would be dissolved. This threat had the effect of pushing the other colonies to Massachusetts’s side. Even the city of Philadelphia, which had originally opposed the Circular, came around. The Daughters of Liberty also promoted the boycott of British goods. Women resumed their spinning bees and again found substitutes for British tea and other goods. Many colonial merchants signed non-importation agreements, and the Daughters urged colonial women to shop only with those merchants. The Sons of Liberty used newspapers and circulars to name and shame merchants who refused to sign such agreements; sometimes they were threatened by violence. The boycott in 1768–1769 turned the purchase of consumer goods into a political gesture. It mattered what you consumed and the clothes you wore indicated whether you were a defender of liberty in homespun or a protector of parliamentary rights in fine British attire.

The Massachusetts Circular got Parliament’s attention, and in 1768 the government sent four thousand British troops to Boston to put down any potential rebellion there. The troops were a constant reminder of British power over the colonies and an illustration of an unequal relationship between members of the same empire. As an added aggravation, British soldiers moonlighted as dockworkers, creating competition for employment. Bostonians, led by the Sons of Liberty, began a campaign of harassment against British troops. The Sons of Liberty also helped protect the smuggling operations of the merchants, claiming smuggling was crucial for the colonists’ ability to maintain their boycott of British goods.

John Hancock was one of Boston’s most successful merchants and prominent citizens. While he maintained too high a profile to work actively with the Sons of Liberty, it was well-known that supported their aims. He was also one of the many prominent merchants who had made their fortunes by smuggling. In 1768, customs officials seized the Liberty, one of his ships, and Bostonians rioted against customs officials, attacked the customs house, and chased out the officers. British soldiers crushed the riots, but over the next few years, clashes between British officials and Bostonians became common. Conflict turned deadly on March 5 1770, in a confrontation that came to be known as the Boston Massacre. On that night, a crowd of Bostonians from many walks of life started throwing snowballs, rocks, and sticks at British soldiers guarding the customs house. In the resulting scuffle, some soldiers, goaded by the mob, fired into the crowd and killed five people. Crispus Attucks, the first man killed, was of Wampanoag and African descent.

The Sons of Liberty immediately seized on the event, portraying the British soldiers as murderers and their victims as martyrs. Paul Revere, a silversmith and member of the Sons of Liberty, circulated an engraving that showed a line of grim redcoats firing ruthlessly into a crowd of unarmed, fleeing civilians. Among colonists who had begun to think of themselves as patriots, this view of the “massacre” confirmed their fears of a tyrannous government using its armies to attack their freedom. But to others, the mob was equally to blame for pelting the British with rocks and insulting them. John Adams, one of the city’s strongest supporters of peaceful protest against Parliament, represented the British soldiers at their murder trial. Adams said the soldiers were the tools of an unjust imperial policy. Of the eight soldiers on trial, the jury acquitted six, convicting the other two of the reduced charge of manslaughter. Long after the trial, the Sons of Liberty maintained a relentless propaganda campaign against British oppression. Newspaper articles and pamphlets implied that the “massacre” was a planned murder. In the Boston Gazette on March 12, 1770, an article described the soldiers as striking first. As it turned out, the Boston Massacre had actually happened after Parliament had already voted to partially repeal the Townshend Acts. By the late 1760s, the American boycott of British goods had drastically reduced British trade. Once again, merchants who lost money because of the boycott strongly pressured Parliament to loosen its restrictions and break the non-importation movement. Charles Townshend died suddenly in 1767 and was replaced by Lord North, who was more inclined to look for a solution with the colonists. North convinced Parliament to drop all the Townshend duties except the tax on tea. To those who had protested the Townshend Acts for several years, the partial repeal appeared to be a major victory. For a second time, colonists had rescued liberty from an unconstitutional parliamentary measure. The hated British troops in Boston departed. The consumption of British goods skyrocketed after the partial repeal, an indication of the American colonists’ continued desire to think of themselves as members of the Empire.

Questions for Discussion

- Which group do you think was more effective in the long run, the Sons or the Daughters of Liberty?

- Why do you think the colonists were so happy when the Townshend Acts were repealed?

Primary Sources

Boston trader Sarah Knight on her travels in Connecticut, 1704

Sarah Knight traveled from her home in Massachusetts to trade goods. Through her diary, we can get a sense of life during the consumer revolution, as well as some of the prejudices and inequalities that shaped life in eighteenth-century New England.

Eliza Lucas letters, 1740-1741

Eliza Lucas was born into a moderately wealthy family in South Carolina. Throughout her life she shrewdly managed her money and greatly added to her family’s wealth. These two letters from an unusually intelligent financial manager offer a glimpse into the commercial revolution and social worlds of the early eighteenth century.

Extracts from Gibson Clough’s war journal, 1759

Gibson Clough enlisted in the militia during the Seven Years War. His diary shows the experience of soldiers in the conflict, but also reveals the brutal discipline of the British regular army. Soldiers like Clough ended their term of service with pride in their role defending the glory of Britain but also suspicion of the rigid British military.

Pontiac, an Ottawa war chief, drew on the teachings of the prophet Neolin to rally resistance to European powers. This passage includes Neolin’s call that Native Americans abandon ways of life adapted after contact with Europeans.

Alibamo Mingo, Choctaw leader, reflects on the British and French, 1765

The end of the Seven Years War brought shockwaves throughout Native American communities. With the French removed from North America, their former Native American allies were forced to adapt quickly. In this document, a Choctaw leader expresses his concern over the new political reality.

Media Attributions

- Charles_II_by_John_Michael_Wright © John Michael Wright is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Charlestownmap © R. Phillips is licensed under a Public Domain license

- AMH-6740-NA_View_of_New_Amsterdam © Johannes Vingboons is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Edward_Hicks_-_Penn’s_Treaty © Edward Hicks is licensed under a Public Domain license

- V0011907 James II and Louis XIV and their compatriots portrayed as ha © R. de Hooghe is licensed under a Public Domain license

- John_Locke © Godfrey Kneller is licensed under a Public Domain license

- V0050647 Group of men and women being taken to a slave market © Unknown is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- nypl.digitalcollections.510d47e4-7375-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.001.v © David Grim is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Thomas_Paine_by_Laurent_Dabos-crop © Laurent Dabos is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 7511183764_66534228db_b © Peter Gordon is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Vue_du_debarquement_anglais_pour_l_attaque_de_Louisbourg_1745 © F. Stephen is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-French_and_indian_war_map.svg © Hoodinski is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Pontiac’s_war © Kevin Myers is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 2000px-Map_of_territorial_growth_1775.svg © Kooma is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Proof_sheet_of_one_penny_stamps_Stamp_Act_1765 © Board of Stamps is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Patrick_Henry_Rothermel © Peter F. Rothermel is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Repeal_of_the_Stamp_Act © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Boston_1768 © Paul Revere is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Boston_Massacre_high-res © Paul Revere is licensed under a Public Domain license