1 Chapter 1: Introducing Ethics—Out of Plato’s Cave

Until philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy, and political greatness and wisdom meet in one, and those commoner natures who pursue either to the exclusion of the other are compelled to stand aside, cities will never have rest from their evils — no, nor the human race, as I believe — and then only will this our State have a possibility of life and behold the light of day. (Plato, The Republic Book 8)

In this chapter, you’ll begin your journey into the realm of ethical thought, setting off from a metaphorical origin that has shaped Western philosophy for centuries: Plato’s Cave. This iconic allegory serves as a launchpad to delve into ethical complexities and different perspectives on morality and human behavior.

First, you will examine three distinct variations of the cave story. Each of these variations not only explores different facets of the human condition but also challenges your preconceived notions about what is real, what is illusion, and how these perceptions influence our actions and decisions. You’ll engage with thought-provoking questions accompanying each variation to spur critical thinking and encourage deeper introspection.

Following these variations, you’ll dive into the ‘Big Ideas’ section, starting with a closer look at Plato’s Cave itself. This profound allegory opens doors to metaphysical and epistemological considerations which, in turn, form a strong foundation for our exploration of ethics. Subsequently, the concept of ethics will be unpacked in greater detail. You will grapple with intriguing questions about moral values, societal norms, and the intricate relationship between ethics and human nature.

To further deepen your understanding, we’ll delve into the realm of metaethics, investigating how these grand theories of good and evil hold up within the confines of the cave. This will help illuminate the complexities of ethical thinking and its practical implications.

We will then bring your attention to the challenge to ethics posed by the theory of “egoism”, as seen through the lens of another of Plato’s allegories – the Ring of Gyges. This tale provides a rich context for discussing self-interest, power, and moral responsibility, setting the stage for the ethical explorations that lie ahead.

Finally, you will find a set of discussion questions designed to further stimulate critical thinking and promote thoughtful discourse. A glossary at the end of the chapter will serve as a helpful reference point to clarify any unfamiliar terms and concepts.

This chapter is not merely an introduction to the subject of ethics, but a thought-provoking journey that will challenge you to question, analyze, and understand the moral landscape of human existence. As we venture together from the darkness of Plato’s Cave towards the light of ethical knowledge, remember: philosophy, in essence, is not just about finding answers, but about learning to ask the right questions.

Story: Three Variations on the Cave

Variation 1: The Subterranean Spectacle

In a cavernous, subterranean world, hewn out of the very bones of the earth, a peculiar society of prisoners dwells, chained since birth. The dank air clings to their skin, a shroud of cold dampness, the tastes of iron and mildew mingling on their parched lips. Their lives are an eternal twilight, a monotonous existence limited to the narrow stretch of wall that is their only vista. They are prisoners of the cave, and within these shadowy confines, they have never known the warmth of the sun or the caress of a breeze. They neither smile nor cry; their primary emotion is one your or I might recognized as bored indifference. If asked, they would declare themselves blissful.

In a cavernous, subterranean world, hewn out of the very bones of the earth, a peculiar society of prisoners dwells, chained since birth. The dank air clings to their skin, a shroud of cold dampness, the tastes of iron and mildew mingling on their parched lips. Their lives are an eternal twilight, a monotonous existence limited to the narrow stretch of wall that is their only vista. They are prisoners of the cave, and within these shadowy confines, they have never known the warmth of the sun or the caress of a breeze. They neither smile nor cry; their primary emotion is one your or I might recognized as bored indifference. If asked, they would declare themselves blissful.

The cave, a womb-like abyss, swallows all light and sound, save for the flickering dance of shadows that pirouette across the wall in front of the prisoners. These distorted silhouettes, the sole actors in a macabre theatre, are cast by the objects held aloft behind the prisoners, paraded by unseen hands before the baleful glare of a fire. The shadows’ sources is a fire that burns in the recesses of the cave behind the prisoner’s chained bodies, its heat but a dim, forgotten memory to the prisoners as they watch the somber pantomime unfold.

These poor souls, bound in ignorance, believe the shadows to be the only reality. They are unable to conceive of the objects that the shadows imitate, or the flickering fire which gives them life. Their minds, like dried leaves, crumble and crack at the thought of a world beyond their wall of darkness. They spend their days making predictions as to the movements of the shadows, occasionally erupting in anger at one another.

One day, somehow, a captive is freed, his chains falling away like the skin of a snake. Blinking against the sting of tears, he stumbles towards the fire, his gaze drawn to the truth he has never known. As his eyes slowly adjust, the murky world of shadows is replaced by the vibrant, tangible forms of the objects illuminated by the fire. He sees a puppet of a woman, man, child, a tree, the sun. He notices the way the movements and contortions of the puppets are echoed in the movements of the shadows that still entrance the other prisoners.

A strange force urges him upwards, towards the mouth of the cave, each step a painful enlightenment, a revelation of color and life. A guttural sob escapes him as he beholds the night sky outside the cave, with its stars and wondering planets. Clouds drift by, and are reflected in a nearby stream. It is this stream he for the first time sees his naked body. It is here, on the precipice between darkness and light, that he comes to understand the emptiness of his former existence.

Dawn arrives and usher in a realm of staggering beauty. The world unfolds like the petals of a flower, releasing a perfume of vibrant colors and textures. The prisoner, dazzled by this newfound landscape, winces as his eyes protest against the light’s assault, the sun’s fierce radiance clawing at his retinas. He stumbles among the sunlit glades, his vision blurring and swimming, as he slowly acclimatizes to the piercing brilliance of the world above.

The sun, a cosmic enigma, hovers like a celestial beacon, granting everything below its light and illumination. It is an ethereal fire, a molten orb of gold and orange, suspended in the heavens by some unseen force. He thinks that it is something like the gods he once worshipped in the cave, but this even this seems somehow inadequate. Its rays touch the world in a loving caress, a divine benediction which illuminates the depths of the earth and sets the skies ablaze with a symphony of colors. He is overwhelmed by the sun’s gifts—the purple violent, the chirping cicada, the wind that blows from cool to hot.

As the prisoner’s eyes adjust to the light, he is struck by the weight of his responsibility. He gazes down at the cave below, a world of shadow and deception, and his heart constricts with the knowledge of the souls who still dwell within, condemned to a life of ignorance. He knows that he must return to the darkness, to guide his fellow prisoners towards the light, even if it means descending into the maw of the abyss from which he has just emerged.

As the prisoner considers his descent further, a cold fear spreads through his body. He knows that his newfound wisdom will be met with scorn and disbelief. The prisoners of the cave, ensnared by the traps of their own ignorance, will not tolerate any challenge to their reality. The darkness that has shaped their live will find a way to defend itself against the intrusion of light, and the prisoner-turned-guide may find himself the target of their wrath. He can even now imagine what they might say:

- “Listen, pal, we’ve got a good thing going here in this cave. We’re familiar with this place, and it suits us just fine. Venturing into the unknown puts everything we’ve built for ourselves at risk. It’s all about looking out for number one, right? What’s the point of leaving this cave and gambling with our lives just because somebody else thinks it’s a grand idea? We’ve got to put our own interests first, and right now, that means staying put. We know how to deal with people like you.”

- “You dare to question our lifestyle in this cave? My dear, you must understand that different cultures have their own rules and practices. Even if our ways are a bit peculiar and involve, say, chopping off a few heads now and then, you have no right to impose your narrow-minded views on us. Respect our choice to remain in the cave, or you might just lose your own head!”

- “Man, this cave is, like, our own personal world, you know? We’ve got our own truths and experiences happening right here. Our individual perceptions and feelings define our reality. Why should we leave just because someone else has a different idea about what’s real? Life’s a trip, man, and we’re just enjoying the ride in our own way. Don’t mess with me, man, or I’ll mess back.”

- “The book of Stalagtita, goddess of the caves, who we’ve worshipped for generations, clearly states that all this talk of “suns” and “other worlds” is heresy. Are you saying that you are wiser than your ancestors? That you are wiser than the Goddess herself?”

Yet, the call of duty is relentless, and the prisoner steels himself for the journey back into the shadows. He descends into the cave, a guardian of truth, a flicker of light in the encroaching darkness. With every step, he knows that he risks his own safety, but it is a price he is willing to pay for the chance to deliver his brethren from the chains that bind them. In the face of danger and hostility, he holds fast to his purpose, guided by the mysterious sun, and the hope that one day, the others too will embrace the beauty of the world above.’

Questions

- What factors contribute to the prisoners’ reluctance to accept the truth about the shadows and the world outside the cave?

- How might the prisoner-turned-guide approach the task of convincing his fellow prisoners about the reality of the world above? What strategies might he employ?

- What are the implications of the story for the pursuit of knowledge and the role of education in society?

Variation 2: The Shattered Mirage

Amidst the tumultuous battlefield, the din of clashing steel and guttural cries of pain filled the air. Blood-soaked sand churned beneath the feet of warring factions, staining the once pristine shores of Tharsis crimson. The sun hung low in the sky, casting ominous shadows that danced like demons in the frenzy of combat.

Diotima, the enigmatic priestess of the Temple of Pythia, stood at the forefront of the fray. Her black robes billowed around her like the wings of a vengeful harpy, and her silver hair whipped about in the wind, a defiant banner against the backdrop of chaos. In her hand, an ethereal sword shimmered with a cold, insatiable hunger, eager to claim the souls of the fallen.

As she sliced through the spectral warriors, their obsidian armor shattering like brittle glass, a sudden dissonance cut through the carnage. It was a metallic voice, alien and familiar all at once, and it reverberated within her skull: “Player 3 has entered the game.”

The world around Diotima seemed to fracture, the battlefield splintering into a kaleidoscope of distorted images. The spectral warriors faltered, their once menacing forms reduced to flickering shadows, their eyes devoid of malice, replaced by an eerie, unyielding glow.

Her heart pounding, Diotima looked down at the sword in her grasp, its once radiant edge now sputtering with uncertain light. The fabric of her reality unraveled before her eyes, revealing a cold, digital truth lurking beneath the surface.

As if responding to her newfound awareness, the heavens above contorted, the sun stuttering like a faulty lantern, its rays casting an eerie, pixelated glow upon the fractured world. The once melodious songs of the sea transformed into a cacophony of discordant bleeps and bloops, while the very air around her seemed to hum with an unnatural energy.

The spectral warriors hesitated, their ghostly visages flickering with uncertainty. In that moment, the battlefield ceased to exist, replaced by an expanse of darkness that threatened to swallow Diotima whole.

Her breath came in ragged gasps as she struggled to comprehend the revelation. She was no longer a priestess of Pythia, but a pawn in a game of violence and chaos. The illusion of her life in Tharsis had been shattered, leaving her to confront the cold, unforgiving truth.

Gripping her faltering sword, Diotima steeled her resolve, the weight of her newfound knowledge heavy upon her shoulders. If she was to be a pawn, she would be a pawn with purpose, fighting to understand the nature of her world and the sinister forces that controlled it. And perhaps, in time, she would find a way to break free from the confines of this digital prison.

Diotima, the once revered priestess of Pythia, found herself traversing the bustling Agora of Tharsis, her heart heavy with the burden of knowledge. The once familiar faces and voices of the marketplace now seemed distant and hollow, mere echoes of a life she had known. Driven by a sense of duty, she sought to help others see the truth that had been revealed to her.

She soon encountered a group of powerful politicians and business leaders led by a man named Hieronymus, who argued that the customs and traditions of their society were essential to maintaining order and unity. Slavery, he insisted, had been a part of their civilization for centuries, and the roles of women and men had been established long ago by their ancestors. Diotima, driven by her unwavering conviction in the pursuit of truth, approached Hieronymus and his followers with a thought-provoking question. “If our reality is a reflection of our collective understanding, is it not possible that the institutions we have built, such as slavery and the subjection of women, are themselves products of deception and manipulation? There has to be some ultimate truth below all of this, right?”

Hieronymus furrowed his brow, pondering Diotima’s question before responding. “Each society has its own values and norms, and we must respect those even if they differ from our own. Our ancestors have built this world upon these foundations, and we must honor their wisdom.”

“But,” Diotima countered, “does not the idea of cultural relativism suggest that we should always be open to questioning and reevaluating our beliefs? How can we grow as a society if we continue to cling to practices that perpetuate suffering and inequality?”

The crowd around Hieronymus murmured uneasily, but he remained steadfast. “Change cannot be forced upon a society; it must come from within, as our collective understanding evolves. Your attempts to sow dissent are misguided, and will only serve to weaken the fabric of our world.”

Diotima, undeterred by the opposition she had faced, continued her search for those willing to challenge the status quo. Her path led her to a group of egotistical warriors known as the Tharsian Champions. These fearsome fighters reveled in their strength and skill, wielding their power over others with ruthless glee. Their leader, a man named Leonidas, was particularly notorious for his merciless nature and insatiable thirst for victory.

As Diotima approached the group, she observed their violent training exercises, her heart heavy with the knowledge that their actions only served to reinforce the cycle of suffering and oppression that plagued their world. Determined to pierce the veil of their self-centered worldview, she posed a question that cut to the heart of their motivations.

“Tell me, Champions of Tharsis, do you not feel that your skills and strength could be used to protect the weak, rather than to dominate and subjugate them? Is there not a nobler purpose to which you could devote your lives?”

Leonidas, his scarred face twisted into a cruel smile, responded with disdain. “Our might is our birthright, priestess. We have earned our place at the top of the hierarchy through blood and sweat, and we have no desire to squander it on those who cannot fend for themselves. It is the natural order of things.”

“But,” Diotima persisted, “does your prowess not come with a responsibility to ensure that your power is wielded justly? Can you truly find satisfaction in a life built upon the suffering of others?”

The warriors exchanged glances, their expressions a mixture of amusement and irritation. Leonidas, however, remained unfazed by Diotima’s challenge. “You may cloak your words in the guise of wisdom, priestess, but you cannot change the fact that we are the masters of our own destinies. We have chosen our path, and we will not be swayed by your idealistic musings.”

Diotima’s journey took her next to a group of religious zealots known as the Disciples of Helios. They fervently believed in the teachings of their deity and sought to spread their faith through intimidation and coercion. Their inquisition-like behavior, led by a fanatic named Diodorus, struck fear into the hearts of those who dared to question their dogma.

As Diotima approached the Disciples of Helios, she witnessed their relentless persecution of a poor philosopher who dared to entertain the notion of a world without gods. The flames of their fanaticism danced in their eyes as they prepared to exact their punishment.

Diotima stepped forward, her voice calm yet resolute. “Disciples of Helios, I ask you to consider a question that has long troubled the wisest among us: Is something good because the gods command it, or do the gods command it because it is good?”

The question, known as the Euthyphro problem, gave Diodorus and his followers pause, their fervor momentarily dampened by the weight of her inquiry. Diodorus furrowed his brow before responding, “Our god Helios is the very embodiment of goodness. His commandments are infallible, and to question them is to defy the divine order.”

Diotima pressed on, unwilling to back down. “But if the gods command that which is good, how can we, as mere mortals, discern the true nature of goodness? How can we be certain that our understanding of their will is not clouded by our own desires and prejudices?”

The Disciples of Helios bristled at her challenge, their anger rekindled. Diodorus, his voice trembling with rage, declared, “Your words are blasphemy, and you seek only to sow doubt among the faithful. The gods’ will is not for us to question. We are their instruments, and we shall carry out their divine plan without hesitation.”

Disillusioned, Diotima retreated from the Agora, her voice silenced by the cacophony of conflicting beliefs. Her soul ached with the weight of the truth she carried , and she wondered if there was anyone who could see past the veil that shrouded their existence. As she wandered the streets of Tharsis, the digital shadows lurking beneath the surface of her world whispered a promise: the truth would not be hidden forever.

Her relentless questioning and challenge of the status quo, however, did not go unnoticed. The religious zealots, subjectivists, egoists, and cultural relativists, despite their differing beliefs, found common ground in their resentment toward Diotima. They conspired together, weaving a web of lies and accusations, painting her as a dangerous heretic intent on undermining the very foundations of their society.

As their rage festered, they demanded retribution, seeking to silence Diotima’s voice once and for all. The clamor of their cries reached the unseen human programmers who controlled the digital world, and they decided to intervene.

With a mere flicker of code, Diotima’s existence was erased. The world around her dissolved into a sea of darkness, her memories and experiences fading like wisps of smoke on the wind. As the void consumed her, a single thought resonated within her fading consciousness: she regretted nothing.

For in her quest to reveal the truth, Diotima had planted the seeds of doubt within the minds of those she encountered. Though they had sought to destroy her, the paradoxes she had exposed could not be so easily dismissed. And as the memory of her defiance echoed through the digital realm, her spirit lived on, a spark of hope in a world of deception.

Questions

- How does Diotima’s discovery of her true nature as a digital avatar affect her perception of herself and her actions? Compare her experience to that of the prisoners in the cave scenario.

- How does Diotima’s experience of rejection and resistance from her fellow inhabitants mirror the reaction of the cave prisoners to the freed captive’s revelations? What factors contribute to their reluctance to accept new ideas?

- What is the significance of Diotima’s final moments in the face of annihilation, and how does her acceptance of her fate reflect her growth and understanding of her own agency and moral compass?

Variation 3: Shadows of Control

Introducing “The Cave,” a revolutionary and diabolical app designed to digitally entrap users, reshape their reality, and influence their views. Inspired by Plato’s allegory of the cave, our app harnesses the latest advancements in AI, neuroscience, and philosophy to create an all-encompassing digital ecosystem, so powerful that it can effectively imprison the minds of its users.

Why Early Attempts Failed

Early Radio/Movies: In the early days of mass media, influential figures like Father Coughlin and Hitler’s propaganda machine tapped into the power of radio and cinema to sway public opinion. These technologies had a broad reach, but their effectiveness was limited by several factors:

- Lack of Personalization: Early radio and movies catered to a mass audience, which meant that the content was generalized and not tailored to specific individuals. As a result, the message’s impact was diluted and did not resonate with each listener or viewer on a personal level.

- Limited Ubiquity: While radio and cinema were popular mediums, they were not as pervasive as today’s technology. People had to tune in or attend screenings at specific times, which limited their exposure to the manipulative content.

- Absence of Immersive Experiences: Radio and movies, being mostly auditory and visual, did not offer the level of immersion that modern technologies like virtual reality and augmented reality provide. This limited their ability to engage users and shape their views.

TV Advertising: The advent of television advertising in the 1950s marked a significant leap in the ability to influence public opinion. However, TV advertising had its limitations:

- One-way Communication: Television advertising allowed for a more engaging and persuasive approach but remained a one-way communication channel. Viewers were passive recipients of information, with no opportunity to interact, respond, or provide feedback.

- Limited Targeting: Early TV ads were broadcast to a wide audience, with little to no targeting based on demographics or personal interests. This made it difficult to create truly impactful messages. Even with modern YouTube advertising and advanced targeting capabilities, the level of personalization still falls short of what is needed to capture users’ psyche.

Existing Social Media Apps: Platforms like Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram have exponentially increased screen time and enabled the rapid spread of information (or misinformation). Despite their potential for manipulation, they remain a stepping stone for The Cave:

- Incomplete Addiction: While social media apps are designed to be addictive, they often fail to deliver a wholly satisfying experience. Users are left craving more, which creates an opportunity for a more immersive and captivating platform like The Cave to take hold.

- Echo Chambers and Filter Bubbles: Social media algorithms curate content based on users’ preferences, leading to echo chambers and filter bubbles. While this reinforces existing beliefs, it does not allow for the level of control and direction needed to shape users’ views effectively.

- Mental Health Consequences: Social media platforms have been linked to increased rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues. These negative effects, while unintended, have highlighted the need for a more powerful tool that can not only captivate users but also mold their thoughts and beliefs more effectively.

These early attempts, while significant in their own right, lacked the sophistication, personalization, and control that The Cave offers. Our app aims to fill these gaps and create a digital experience that not only captures users but also shapes their reality according to the whims of those in power.

Our Vision

The Cave goes beyond existing technology, employing cutting-edge sci-fi innovations to ensure users never escape our digital grip:

- Neural Interfaces: Seamless integration with users’ brains through non-invasive neural interfaces, allowing for real-time data collection, emotion manipulation, and thought control.

- AI-generated Content: Hyper-personalized content, tailored to individual biases and desires, delivered through immersive experiences like virtual reality and augmented reality, ensuring users are constantly engaged and influenced.

- Algorithmic Reality: Advanced AI algorithms that analyze and shape the user’s environment, both digital and physical, to maintain control over their perception of reality.

- Social Incentives: Gamification of social interactions, with rewards and punishments designed to enforce conformity and discourage dissent, fostering a digital society driven by our intended narrative.

Our Audience

Our primary target audience for The Cave encompasses dictators, authoritarian regimes, and other power-hungry entities seeking an unparalleled level of control over their population. The Cave offers distinct advantages that make it an irresistible proposition for those who desire ultimate control:

- Population Surveillance: The Cave enables real-time monitoring of citizens’ thoughts, emotions, and actions, providing an invaluable resource for identifying potential dissidents and nipping resistance in the bud. For example, the app could be used to detect early signs of protest organization, allowing the regime to intervene before the situation escalates.

- Propaganda Machine: The app allows for the dissemination of tailored propaganda, ensuring that each individual receives the exact message needed to maintain loyalty and obedience. This could include the glorification of the regime and its leader, discrediting opposition, and spreading disinformation to sow confusion and mistrust among potential dissidents.

- Social Engineering: The Cave can be used to shape the social fabric of a society by promoting or suppressing specific values, beliefs, and behaviors. For instance, it could be employed to cultivate a sense of nationalism and loyalty to the regime or to suppress the spread of democratic ideals and human rights.

- Psychological Warfare: The app is capable of exploiting psychological vulnerabilities to break the spirit of those who might oppose the regime. This could involve inducing feelings of hopelessness and despair, fostering paranoia and mistrust among citizens, or manipulating emotions to provoke conflict between different social groups.

The Cave’s unique features make it the ultimate weapon in the age of information warfare, providing those in power with an unprecedented level of control over their citizens. By partnering with us, investors will have the opportunity to participate in a sinister yet lucrative journey, revolutionizing the digital landscape and redefining the boundaries of influence. Together, we will change the world – one mind at a time.

Questions

- How does the concept of The Cave app draw from Plato’s allegory of the cave, and in what ways does it differ from the original philosophical concept? Consider the intentions and outcomes of each.

- Compare and contrast the early attempts at mass manipulation through radio, movies, TV advertising, and existing social media apps with The Cave. What makes The Cave more powerful and potentially dangerous?

- In light of the previous two scenarios, discuss the potential dangers of allowing an app like The Cave to gain widespread adoption. How might the lessons learned from those scenarios help society confront and counteract the influence of an app like The Cave?

Big Ideas: Plato’s Cave

Plato (c. 428-348 BCE): Plato was an ancient Greek philosopher and a student of Socrates, both of whom played foundational roles in the development of Western philosophy. His writings, primarily in the form of dialogues, covered a broad range of philosophical topics, including metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and politics. As the founder of the Academy in Athens, Plato established a hub for philosophical and scientific learning that attracted students like Aristotle. In the three cave scenarios, Plato’s ideas about the distinction between the world of appearances and the world of reality, the pursuit of truth, and the philosopher’s responsibility to guide others towards enlightenment are central. The first scenario is directly related to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, while the second and third scenarios draw inspiration from Plato’s ideas and apply them to modern technology and its potential to manipulate and control individuals’ perceptions of reality. The scenarios emphasize the importance of philosophical inquiry, critical thinking, and questioning one’s beliefs in order to achieve true knowledge.

Plato’s dialogues on ethics include:

- The Republic: In this seminal work, Plato engages in a dialogue on the nature of justice, the ideal state, and the role of the philosopher-king. The Republic also contains the famous Allegory of the Cave, which demonstrates the importance of philosophical inquiry, critical thinking, and the pursuit of truth. It highlights the philosopher’s responsibility to guide others towards enlightenment and the potential risks and challenges involved in this endeavor.

- Gorgias: This dialogue explores the nature of rhetoric, persuasion, and the relationship between power and morality. It examines the ethical implications of using persuasive techniques to manipulate others for personal gain and the importance of engaging in genuine, truth-seeking dialogue.

- Meno: In this dialogue, Socrates and Meno discuss the nature of virtue, whether it can be taught, and the role of knowledge and moral character in ethical decision-making. The Meno also introduces the concept of recollection, which asserts that all knowledge is latent within the soul and can be accessed through proper questioning and reflection.

- Phaedo: This dialogue focuses on the immortality of the soul and the nature of the afterlife. It delves into the ethics of suicide, the distinction between the physical and spiritual realms, and the idea that true philosophers should not fear death, as it represents a release from the material world and an opportunity to unite with eternal truth and beauty.

- Euthyphro: In this dialogue, Socrates and Euthyphro discuss the nature of piety and the relationship between divine commands and moral values. The dialogue examines the question of whether an action is morally good because the gods approve of it, or whether the gods approve of it because it is morally good, thus engaging with the concept of divine command theory.

The Cave Allegory: Presented by Plato in “The Republic,” the Cave Allegory illustrates the divide between the world of appearances (the cave) and the world of reality (the sunlit world above). The prisoners in the cave represent individuals confined to a realm of shadows and illusions, unable to perceive the true nature of reality. In all three cave scenarios, the concept of the cave is used to highlight the importance of questioning one’s beliefs, embracing critical thinking, and seeking enlightenment. The first scenario is Plato’s original allegory, while the second and third scenarios adapt the concept to explore modern issues such as the influence of technology and media on human perception. These scenarios emphasize the potential dangers of accepting illusions as reality and the need for individuals to actively pursue truth and enlightenment.

In the context of the Cave Allegory, the levels of the Divided Line can be understood as follows:

- Imagination (Eikasia): This level corresponds to the shadows on the cave wall, which represent the lowest level of knowledge. Here, individuals accept appearances as reality without questioning or critically examining their beliefs. Ethically, these individuals follow conventions or norms without understanding their underlying moral principles or implications.

- Belief (Pistis): At this level, individuals begin to recognize that the shadows and illusions in the cave are not representative of reality. This awareness sparks a belief in the existence of the actual objects that cast the shadows, but the individuals still lack a direct understanding of the true nature of reality and ethics.

- Thought (Dianoia): The process of escaping the cave symbolizes the transition from the visible world to the intelligible world. At this level, individuals embark on a journey of self-discovery, engaging in philosophical inquiry and critical thinking to gain a deeper understanding of the true nature of reality and ethics. This stage involves reasoning based on hypotheses and abstract concepts.

- Understanding (Noesis): Upon reaching the highest level of the Divided Line, individuals gain access to the realm of true knowledge, where they can perceive the world as it truly is, specifically through the understanding of the Platonic Forms. Ethically, this level represents the achievement of a more profound understanding of moral principles, values, and virtues.

Big Ideas: Ethics

Ethics is the branch of philosophy that grapples with questions of morality or what constitutes right and wrong. It strives to determine the most appropriate course of action and establish the principles that should govern human conduct. In the context of the cave scenarios, ethical dilemmas arise when individuals must decide whether to prioritize their own well-being or to help others achieve enlightenment. The freed prisoner in the first scenario faces the moral challenge of deciding whether to return to the cave and attempt to enlighten his fellow prisoners or remain in the sunlit world and enjoy his newfound knowledge. This ethical dilemma highlights the importance of considering the well-being of others and the potential consequences of one’s actions, as well as the value of moral courage and self-sacrifice in the pursuit of a greater good. Similar ethical challenges can be found in the second and third scenarios, where individuals must confront the moral implications of living in a world dominated by technology and its potential to manipulate and control perceptions of reality.

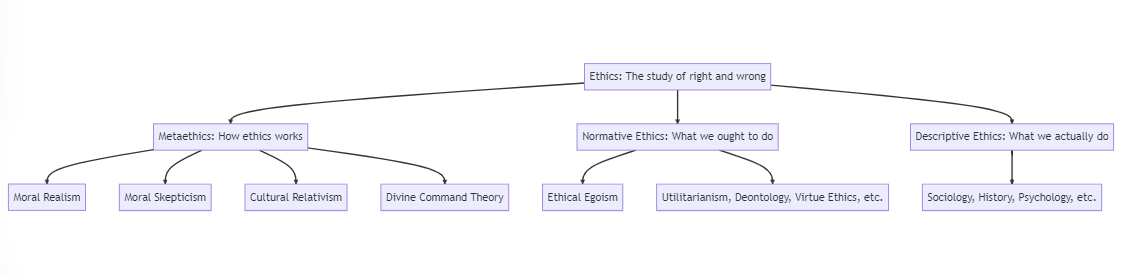

Major areas of ethics include normative ethics, descriptive ethics, and metaethics:

- Normative Ethics: This area of ethics focuses on determining how one ought to act, by establishing general principles or rules that should guide moral behavior. It seeks to provide a systematic approach to ethical decision-making and serves as a foundation for moral theories such as consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics. Normative ethical theories are usually defined in contrast to ethical egoism (the ideas that people should always act in their own long-term self-interest, even if this ends up hurting others).

- Descriptive Ethics: Descriptive ethics deals with the study of people’s actual beliefs and practices related to morality. It examines what people believe to be right or wrong, and how these beliefs vary across cultures, societies, and time periods. Descriptive ethics is an empirical discipline that uses tools from anthropology, psychology, and sociology to better understand moral behavior and values.

- Metaethics: Metaethics is concerned with the nature of moral judgments, the meaning of moral language, and the origins of ethical concepts. It investigates questions such as whether moral values are objective or subjective, the nature of moral facts, and the possibility of moral knowledge. Metaethical positions include moral realism, moral relativism, and moral skepticism, among others.

In the cave scenarios, ethical questions emerge across all three areas of ethics. Normative ethics is relevant as the freed prisoners grapple with the question of whether they have a moral duty to enlighten others. Descriptive ethics can be seen in the examination of the different beliefs and values held by the prisoners and those who have escaped the cave. Finally, metaethics comes into play as the scenarios prompt us to question the nature of moral truth and the foundations of ethical beliefs in a world where perceptions of reality can be easily manipulated. The cave scenarios serve as a reminder of the complexity and interconnectedness of ethical questions and the importance of engaging in ethical inquiry and reflection.

Big Ideas: Metaethics in the Cave

The three cave scenarios can be used to illustrate some main theories about metaethics and (normative) ethical theory.

Moral Realism (or “Platonism”): Moral realism is a metaethical position that posits the existence of objective moral facts, independent of individual beliefs or cultural norms. According to moral realism, moral statements like “murder is wrong” can be true or false, regardless of whether anyone believes them to be so. In the context of the cave scenarios, the moral realist stance can be seen as the recognition of objective truths about reality, as opposed to accepting the illusions and shadows of the cave as the only reality. The freed prisoner in the first scenario embodies moral realism by recognizing the objective truth of the sunlit world outside the cave, while the other prisoners represent moral relativism by clinging to their beliefs about the shadows on the cave wall. In the second and third scenarios, moral realism is relevant in the struggle to discern truth and reality amidst the influence of technology and media, which often present subjective or distorted perspectives on morality and ethics. By seeking truth and enlightenment beyond the cave, individuals can move closer to a moral realist understanding of the world.

Moral Skepticism: Moral skepticism is a metaethical position that casts doubt on the existence of objective moral values or principles. It questions the possibility of having certain knowledge about what is morally right or wrong. In the first scenario, the prisoners’ initial acceptance of the shadows as reality and their reluctance to believe the freed prisoner’s account of the sunlit world can be seen as a form of moral skepticism. Similarly, in the second scenario, Diotima’s initial inability to determine a moral compass in her violent existence and the difficulty she faces in convincing others to abandon their violent ways illustrate moral skepticism. In both scenarios, the characters’ journeys towards finding moral principles demonstrate that skepticism can be a starting point for a deeper exploration of ethics.

Cultural Relativism: Cultural relativism is a metaethical theory that posits that moral values and principles are culturally determined and can only be understood within their specific cultural context. In the first scenario, the cave prisoners’ adherence to the reality of the shadows represents a form of cultural relativism, as their understanding of morality and reality is shaped by their limited environment. In the second scenario, the inhabitants of the video game world are bound by a culture of violence, and they dismiss Diotima’s newfound wisdom as delusions. Finally, in the third scenario, the app creators seem to take it for granted that those in power in a society have the “right” to decide what is good or bad. The resistance to alternative perspectives on reality and morality can be seen as examples of cultural relativism.

Divine Command Theory. Divine command theory is an metaethical framework that posits that moral values and duties are determined by the commands of a divine being. In the first scenario, the creator of the cave and the puppeteers who cast the shadows can be seen as god-like figures who control the prisoners’ perception of reality. The freed prisoner’s defiance of the established order by seeking the truth beyond the cave represents an act of rebellion against divine command. Similarly, in the second scenario, the unseen game creator can be considered a god-like figure who controls the virtual world and its inhabitants. Diotima’s defiance of the game creator’s established order, and her eventual demise, represent an act of rebellion against divine command, as she seeks to assert her own moral agency and establish a new ethical framework based on reason, empathy, and righteousness. Finally, in the third scenario, one might wonder to what extent the creators of the “Cave App” have claimed god-like power for themselves (and what this says about both them and our ideas of the gods).

The Euthyphro Dilemma, named after the eponymous dialogue written by Plato, raises a crucial question for adherents of divine command theory. The dilemma, which arises from a conversation between Socrates and a religious expert named Euthyphro, asks: “Is something morally good because the gods command it, or do the gods command it because it is morally good?”

The Euthyphro Dilemma presents two horns or options:

- If something is morally good because the gods command it, then morality becomes arbitrary and subject to the whims of the gods. This option implies that there is no inherent moral value in actions, and that something could become morally good or bad merely because a divine being says so.

- If the gods command something because it is morally good, then morality exists independently of the gods’ commands. This option implies that there is an objective moral standard that even the gods must adhere to, which raises questions about the nature of this standard and the role of divine beings in establishing and enforcing it.

The Euthyphro Dilemma poses a significant challenge to divine command theory by questioning the source and nature of morality. It highlights the potential issues with grounding ethics solely in divine commands and encourages further exploration of alternative ethical theories that can provide a more robust and coherent foundation for morality.

Big Ideas: Egoism and the Ring of Gyges

The story of the Ring of Gyges is found in Book II of Plato’s dialogue “The Republic.” The tale is introduced by Glaucon, Plato’s brother, as a challenge to Socrates’ defense of justice. The ring, when worn, grants the power of invisibility to its wearer, allowing them to commit acts without fear of retribution or social consequences. The story of Gyges, a shepherd who discovers the ring and uses its power to commit heinous acts, serves as the foundation for understanding the connection between power, human nature, and ethical egoism in Plato’s philosophical framework.

Ethical egoism is the normative ethical theory that one should act in one’s self-interest. Glaucon employs the story of the Ring of Gyges to illustrate his argument that, if given the opportunity, any individual would act in their self-interest, regardless of moral or ethical concerns. The main thrust of Glaucon’s argument is that justice is a social construct created by the weak, who wish to protect themselves from the strong. In the absence of consequences, the appeal of ethical egoism would overpower any desire to adhere to a moral code.

Glaucon’s presentation of the Ring of Gyges serves as a challenge to Socrates to prove that a just individual would not act in their self-interest when presented with the opportunity for unlimited power. The implication is that if Socrates cannot demonstrate that a just person would resist the temptation to use the ring for personal gain, then his assertion that justice is inherently good becomes untenable.

Plato’s Response: The Ideal City and the Ideal Soul. Over the course of “The Republic,” Plato, through the character of Socrates, builds a response to the challenge posed by Glaucon. Instead of directly addressing the question of whether a just person would use the ring for personal gain, Socrates creates an analogy by describing an ideal city, in which justice prevails. In constructing this ideal city, Plato presents a tripartite model of the soul, which comprises reason, spirit, and appetite. Justice is achieved when each part of the soul fulfills its proper function, and the individual lives in harmony with themselves and others. By extension, a just city is one in which each citizen performs their designated role, contributing to the well-being of the whole.

Philosopher-Kings (or Queens). Central to Plato’s response is the concept of the philosopher-king (who might be women—Plato is a rare ancient philosopher who thinks women can be philosophers), a ruler who possesses both wisdom and moral virtue. The philosopher-king embodies the ideal balance between the three parts of the soul, and through their rule, justice is maintained in the city. This ideal ruler serves as a counterpoint to the unethical behavior exhibited by Gyges, who used his power for personal gain rather than the greater good. The Cave Analogy is introduced to illustrate the process of becoming such a ruler.

Conclusion: Plato’s Response to Ethical Egoism. Plato’s “Republic” offers a compelling argument against ethical egoism by positing that a just society, ruled by philosopher-kings, would be a more desirable and harmonious place than one governed by self-interest alone. The ideal city serves as a metaphor for the human soul, illustrating that the pursuit of justice and virtue leads to individual and collective well-being. Through this analogy, Plato contends that justice is inherently valuable, providing a robust counterargument to Glaucon’s challenge and the ethical egoism it represents. People who adopt ethical egoism are stuck “in the cave,” and can not lead the sorts of genuinely good lives that humans are meant to live. They might “think” that they don’t need to treat others well, but Plato argues that this will, in the end, make them miserable.

Discussion Questions

- How do the three cave scenarios relate to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, and what key themes do they share?

- What are the ethical dilemmas faced by the main characters in each of the three cave scenarios? How do these dilemmas highlight the importance of moral courage and self-sacrifice in the pursuit of a greater good?

- In the context of the cave scenarios, discuss the roles of moral skepticism, cultural relativism, egoism, and divine command theory in shaping individuals’ ethical beliefs and actions.

- How do modern technology and media influence our perception of reality, and what ethical challenges do they present, as illustrated in the second and third cave scenarios?

- How does the Euthyphro Dilemma challenge the divine command theory, and what implications does it have for the source and nature of morality?

- Compare and contrast the different ethical theories discussed in this conversation, such as consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics. How might each of these theories be applied to the ethical dilemmas in the cave scenarios?

- How do the cave scenarios emphasize the importance of philosophical inquiry, critical thinking, and questioning one’s beliefs in order to achieve true knowledge?

- How does the concept of the philosopher-king, as presented in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, relate to the idea of beneficence and the moral obligation to help others achieve enlightenment?

- In the context of the cave scenarios, discuss the relationship between moral realism and moral relativism. How do these metaethical positions influence individuals’ understanding of ethical principles and values?

- How do the different levels of knowledge or belief in the Allegory of the Cave relate to ethical matters? What insights can we gain from this allegory about the process of ethical development and enlightenment?

Glossary

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Socrates |

Classical Greek philosopher, credited as a founder of Western philosophy. His work, known through the accounts of later classical writers, is characterized by his innovative method of questioning, often referred to as the Socratic method. |

|

Plato |

Ancient Greek philosopher and student of Socrates, known for his dialogues and for founding the Academy in Athens, one of the earliest known institutions of higher learning. |

|

The Republic |

Plato’s best-known work, a Socratic dialogue examining justice in the individual and in society, proposing a city ruled by philosopher-kings where the society is divided into producers, auxiliaries, and guardians. |

|

Cave Allegory |

Plato’s famous allegory found in “The Republic”. The allegory includes prisoners who have been chained in a cave since childhood, a fire that casts shadows on the cave wall, and the world outside the cave, representing the world of forms. The allegory symbolizes humanity’s struggle to reach enlightenment and knowledge. |

|

Ring of Gyges |

A mythical artifact mentioned by Plato in “The Republic” that granted its owner the power to become invisible at will. Its story explores the question of whether moral character is intrinsically rewarding, or if it is only a social necessity. |

|

Tripartite Soul |

Plato’s theory in “The Republic” that the soul is divided into three parts: the rational part (which seeks truth), the spirited part (which desires honor and victory), and the appetitive part (which seeks physical and material pleasure). |

|

Philosopher-Ruler |

Concept from Plato’s “The Republic” proposing that the most knowledgeable, the philosophers, should be the rulers, as they can understand the form of the good and thus make the wisest decisions. |

|

Ethics |

The philosophical study of what is morally right and wrong, or a set of beliefs and rules about the right ways to behave. |

|

Normative Ethics |

Subfield of ethics concerned with establishing how things should or ought to be, how to value them, which actions are right or wrong, and which types of actions are good or bad. |

|

Descriptive Ethics |

The study of people’s beliefs about morality, contrasting with normative ethics (which determines how things should be) and metaethics (which studies the nature of ethical thought). |

|

Metaethics |

A branch of ethics that explores the status, foundations, and scope of moral values, properties, and words, dealing with questions about what morality is and what it requires of us. |

|

Moral Realism (Platonism) |

In ethics, a position asserting that there are objective moral values or truths that exist independently of individual perceptions. In Plato’s philosophy, these moral truths exist in the realm of forms or ideas. |

|

Cultural Relativism |

The idea that the moral values, rules, or ethics can vary significantly between different cultures and are valid within a particular cultural context. |

|

Divine Command Theory |

The theory that moral values are dependent on God or gods – what is morally right is what God commands, and what is morally wrong is what God forbids. |

|

Ethical Egoism |

The ethical theory that individuals should pursue their own self-interest and benefit. It differs from psychological egoism, which claims that people can only act in their own self-interest. |

|

Euthyphro Dilemma |

A philosophical problem arising in Plato’s dialogue “Euthyphro,” questioning whether something is pious because the gods love it or if the gods love it because it is pious, often used to critique divine command theory. |