16 Judaism

Judaism is the oldest monotheistic religion in our world. There have been and are those who argue for Hinduism being monotheistic, and those who point to Egyptian Akhenaten as leading the brief monotheistic sect of Aten worship. But there are arguments against each of these being true monotheistic faiths, and for the most part, scholars agree that it is Judaism that introduces real monotheism–the worship of only one god–to the organized world religions.

The history of the Jews can be divided into four general periods of time.

In the first period in the early history of the Hebrew people included nomadic and tribal life. There are various important events in the lives of these people, most of which we have no real historic or archaeological proof of being factual. These are elemental stories that inspire and show a covenant between the people and God, however, and the point of the stories is not really to be history, but to be inspirational. Early Jews followed various prophets from Abraham and his sons and grandsons, all the way to Moses and Joshua, and the tribes eventually found a homeland in what is now called Israel/Palestine. This first period is marked with the milestones of establishing first a tribal confederacy with judges ruling, eventually a kingly dynasty, the establishment of a capital in Jerusalem, and the first temple for sacrificial worship. The three great kings in Jewish tradition are Saul, David and Solomon. The approximate dates for this royal dynasty are 1020 to 922 BCE. These kings might more closely resemble tribal chieftains than European royals, but they were war leaders and lead a united kingdom of the tribes. After the reign of Solomon ended, the nation of Israel divided into two due to civil war, and after this the north was still called Israel, and the south, was then called Judah. The first historic indicator that we have indicating the factual reality of a nation called Israel comes

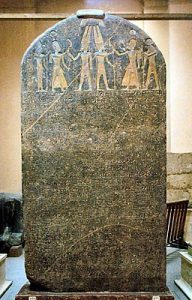

In the first period in the early history of the Hebrew people included nomadic and tribal life. There are various important events in the lives of these people, most of which we have no real historic or archaeological proof of being factual. These are elemental stories that inspire and show a covenant between the people and God, however, and the point of the stories is not really to be history, but to be inspirational. Early Jews followed various prophets from Abraham and his sons and grandsons, all the way to Moses and Joshua, and the tribes eventually found a homeland in what is now called Israel/Palestine. This first period is marked with the milestones of establishing first a tribal confederacy with judges ruling, eventually a kingly dynasty, the establishment of a capital in Jerusalem, and the first temple for sacrificial worship. The three great kings in Jewish tradition are Saul, David and Solomon. The approximate dates for this royal dynasty are 1020 to 922 BCE. These kings might more closely resemble tribal chieftains than European royals, but they were war leaders and lead a united kingdom of the tribes. After the reign of Solomon ended, the nation of Israel divided into two due to civil war, and after this the north was still called Israel, and the south, was then called Judah. The first historic indicator that we have indicating the factual reality of a nation called Israel comes from an Egyptian artifact called the Merneptah Stele, found at a dig in 1896 CE. On this item, which is a celebratory marker which writes about Merneptah conquering various neighboring nations, is found the name of the nation of Israel. The stele dates to 1208 BCE, and firmly establishes some kind of timeline for the nation’s existence. Although the texts talks about virtually eradicating Israel from existence, that clearly is an exaggeration.

from an Egyptian artifact called the Merneptah Stele, found at a dig in 1896 CE. On this item, which is a celebratory marker which writes about Merneptah conquering various neighboring nations, is found the name of the nation of Israel. The stele dates to 1208 BCE, and firmly establishes some kind of timeline for the nation’s existence. Although the texts talks about virtually eradicating Israel from existence, that clearly is an exaggeration.

A second period began between the eighth to the sixth century BCE when the kingdom of Assyria conquered northern Israel ion about 722 BCE, and then the kingdom of Judah and its first temple were destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, and the people were forced into a fifty-year exile in Babylon starting in about 596 BCE. Although there were many Jews forced to leave Judah, the majority of those so exiled were the educated, skilled, and upper classes of the Jewish people. Peasants, farmers, and those at a distance from population centers did not leave the country. This caused some rifts in the Hebrew people over time, especially when the exiles returned to Israel. This event called the Exile, however, led to the emergence of the synagogue style of worship instead of temple sacrifices, as the people in exile had no temple to use, and prompted putting religious law and history into a written form to guarantee its survival. Oral tradition translated into written materials, and we see psalms, the Torah, and other bits of writing coming from that era.

A second period began between the eighth to the sixth century BCE when the kingdom of Assyria conquered northern Israel ion about 722 BCE, and then the kingdom of Judah and its first temple were destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, and the people were forced into a fifty-year exile in Babylon starting in about 596 BCE. Although there were many Jews forced to leave Judah, the majority of those so exiled were the educated, skilled, and upper classes of the Jewish people. Peasants, farmers, and those at a distance from population centers did not leave the country. This caused some rifts in the Hebrew people over time, especially when the exiles returned to Israel. This event called the Exile, however, led to the emergence of the synagogue style of worship instead of temple sacrifices, as the people in exile had no temple to use, and prompted putting religious law and history into a written form to guarantee its survival. Oral tradition translated into written materials, and we see psalms, the Torah, and other bits of writing coming from that era.

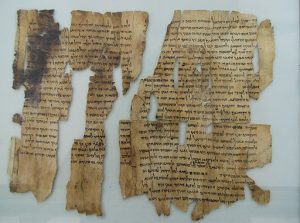

A second temple was eventually built in Jerusalem when the exiles were allowed to return home to Israel from Babylon. They began writing down in more permanent form what is now the first half of the Bible, the Hebrew Scriptures. Influences from the surrounding cultures entered into Jewish life both before and after this era. From the Babylonians came Zoroastrian ideas, such as the dualism of heaven and hell, and later the appeal of Hellenistic/Greek culture impacted Jewish worship and practice. Tensions arose because of differing ideas and practices in Judaism, and the differences between accepting and rejecting of these foreign influences led to the rise of Jewish factions after 165 BCE. These groups included the Sadducees, the Pharisees, the Zealots, and the Essenes, who assembled the Dead Sea Scrolls. This period also saw the growth of the Diaspora, Jewish communities established outside the land of Israel.

between accepting and rejecting of these foreign influences led to the rise of Jewish factions after 165 BCE. These groups included the Sadducees, the Pharisees, the Zealots, and the Essenes, who assembled the Dead Sea Scrolls. This period also saw the growth of the Diaspora, Jewish communities established outside the land of Israel.

The third period was initiated in the Common Era when the second temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE, as they violently put down a Jewish rebellion against the Roman occupation of Jewish land. This destruction of both the city and the temple ended the power of the temple priesthood, as sacrificial rituals were no longer possible, and forced the religion to move toward a greater focus on scripture. The Hebrew canon (the established list of books in the Hebrew scriptures) was finalized and commentaries about them were written in the next several hundred years. Classical Judaism and traditional Jewish life were also established during this time. Great communities of Jewish people in the Diaspora (non-Israeli lands) both flourished and endured persecution, mainly at the hands of European Christians. Considered “Christ![This triptych, which depicts a sequence of anti-Jewish violent acts throughout history (the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, the Spanish Inquisition, and pogroms in Eastern Europe), is ironically titled after the motto of the Societas Iesu (the Catholic Jesuit order): “for God’s greater glory [and the salvation of humanity].”](https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/910/2021/01/27244839657_1976b7f5e4_w-283x300.jpg) Killers” by the Catholic and eventually Protestant churches, the Crusades, the Inquisition, the Pogroms, and much general restriction and persecution took place during the entire Christian Era (post 30 CE). The Nazi era was actually preceded by hundreds of years of killing, persecution and hatred aimed at the Jewish people.

Killers” by the Catholic and eventually Protestant churches, the Crusades, the Inquisition, the Pogroms, and much general restriction and persecution took place during the entire Christian Era (post 30 CE). The Nazi era was actually preceded by hundreds of years of killing, persecution and hatred aimed at the Jewish people.

The fourth and final period, called the Reform Period, began in about 1800 CE as a response to the European Enlightenment. It was a time to question and modernize traditional Judaism, and it helped produce diverse branches within Judaism today, which hold differing views on Jewish identity and practice. The standard branches of Judaism came to be–the Orthodox, the Conservative, and coming out of the more academic and liberal wing of Judaism, the Reform Jews. These three became identifiable branches of the faith, with the Reconstructionist Jewish group coming about in the late 20th century CE. Centuries of persecution reached a climax with the Holocaust under the reign of Adolf Hitler. One-third of all Jews in the world were killed. Shortly after the end of World War II, the nation of Israel was born. Zionism, which is the concept of returning Jews to a Jewish homeland in what had been historic Israel, was born in the 3rd period, and came to full fruition in the 4th period with the  establishment of Israel as a nation in 1948. The centuries of conflict between the monotheistic faiths, between Europe and the Middle East, and between people who had lived in the Palestine/Israel area for many years, and those who immigrated there and bought land has continued to this day.

establishment of Israel as a nation in 1948. The centuries of conflict between the monotheistic faiths, between Europe and the Middle East, and between people who had lived in the Palestine/Israel area for many years, and those who immigrated there and bought land has continued to this day.

An excellent timeline for the development of Judaism from Professor Simon Schama[1]

Judaism and their Sacred Texts

Judaism is often associated with its most important writings. The Hebrew Bible contains a variety of material that records interactions and responses between the people and a God who is portrayed in complex ways, perhaps reflecting different ancient traditions that were ultimately combined. The scriptures are divided into three parts.

First is the Torah, the sacred core of five books containing stories of the Creation, Adam and Eve, a Great Flood, the Hebrew patriarchs and matriarchs, and Moses, the great liberator and lawgiver. It includes laws about religious ritual and daily conduct, including the Ten Commandments.

The Torah

We look at the major scripture of Judaism–the Torah–with assistance from Maryanne Saunders[2], writing for the British Library, The entire text of the article on the Torah can be read here at The Torah:

Torah (תורה) in Hebrew can mean teaching, direction, guidance and law. The most prominent meaning for Jews is that the Torah constitutes the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (also called the Pentateuch, ‘five books’ in Greek), traditionally thought to have been composed by Moses. These sacred texts are written on a scroll and kept in a synagogue. Sometimes the word Torah is used to refer to the whole Hebrew Bible (or Tanakh) which additionally contains Nevi’im (נביאים), which means Prophets, and Ketuvim (כתובים) meaning Writings. Torah can also refer to wider scriptural commentaries (Talmud) and even all Jewish religious knowledge. It is in this sense that Jews will often speak of the importance of living a life guided by Torah.

Example: the 10 Commandments

1) I am the Lord thy god, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt have no other gods before Me.

2) You shall not make for yourselves an idol

3) Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain.

4) Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy.

5) Honor thy father and thy mother.

6) Thou shalt not murder.

7) Thou shalt not commit adultery.

8) Thou shalt not steal.

9) Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

10) Thou shalt not covet anything that belongs to thy neighbor.

These five books are the same five books that make up the start of the Christian Bible. The Torah text can be written out by a scribe in Hebrew onto a scroll and used

in public prayer services or printed in books for individuals and congregations to study. The Torah has central importance in Jewish life, ritual and belief. Some Jews believe that Moses received the Torah from God at Mount Sinai, whilst others believe that the text was written over a long period of time by multiple authors. The scroll must also be written entirely in Hebrew with no vowels or indication of how the words are pronounced. This means that readers must have existing knowledge of the Torah to identify what each word means, emulating the texts and scholars as they were millennia ago. The text within is divided up into fifty-four portions, so that one (or sometimes two) can be read per week for a year, before starting again on a holiday called Simchat Torah (‘Rejoicing with the Torah’). Scrolls are generally required to be made out of animal skins and can take up to two years to produce, mainly due to the rules against erasing any of the words – which means that the scribe cannot make a single mistake without starting again. It was not until the 4th century BCE that the Torah became a holy object reserved for public readings. The text of the Torah would have originally been written down on papyrus scrolls to be studied and discussed by scholars. It is only after the Babylonian Exile in 444 BCE as the Jews returned to Israel, that Ezra the scribe is recorded as having read aloud from the five books of Moses (Nehemiah 8).

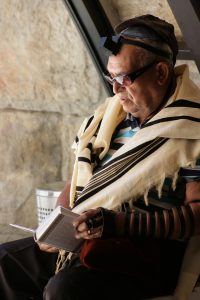

Traditionally, the Torah is read four times a week in the synagogue: at the Sabbath (Saturday) morning and afternoon services and in the morning service on Mondays and Thursdays. Additional readings may occur on high holy days such as Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) or Rosh Hashana (New Year). Many synagogues are in possession of more than one scroll, but all are housed in the Ark, a large cabinet positioned to face Jerusalem. As a sign of the sacred status of the Torah, the scroll is often covered with a decorative mantle. As well as being covered, the Torah is not read without a pointer to highlight and direct the reader. Hands don’t touch the surface, but instead a silver or bone pointer is used.

The Torah is chanted in the synagogue by the rabbi, the cantor (singing leader) or a person who has been called up to the bimah (an honour called Aliyah).

Example: Psalm 23

Cantor and senior Rabbi Angela Buchdahl from Central Synagogue, New York City

Whether there is any musical accompaniment depends on the denomination of the synagogue: for example, in Orthodox congregations the singing is in classical Hebrew, unaccompanied and without a microphone; on the other hand, in Reform synagogues there may be a choir, musical instruments and vernacular language used.

Another way in which the denomination of a synagogue may affect services is the degree to which women are included. In Orthodox and some conservative congregations, women are seated separately from men, in a gallery or behind a screen. In these congregations it is less likely that a woman would be permitted to go up to the bimah, read from or even touch the Torah scroll. On the other hand, Liberal, Reform and other synagogues allow women to be ordained as rabbis, lead prayer services and sit with whomever they please.

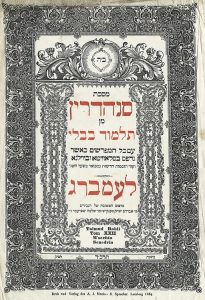

The Talmud

The Talmud is a set of writings about faith, and how to live the law. The Talmud, meaning ‘teaching’ is an ancient text containing Jewish sayings, ideas and stories. It includes the Mishnah (oral law) and the Gemara (‘Completion’). The Mishnah is a large collection of sayings, arguments and counter-arguments that touch on virtually all areas of life. The Gemara is known as a ‘sea’ of learning, a collection of stories about biblical characters, sober legal arguments and fanciful imaginings of the world of old and the world to come.

The Talmud developed in two major centers of Jewish scholarship: Babylonia and Palestine. The Jerusalem or Palestinian Talmud was completed about 350 CE, and the Babylonian Talmud (the more complete and authoritative) was written down about 500 CE, but was further edited for another two centuries. The Talmud served as the basis for all codes of rabbinic law.

From the Palestinian tradition of Jewish worship came the Ashkenazi rite used in Western and Eastern Europe and Russia. From the Babylonian tradition came the Sephardi rite followed in Spain, Portugal, North Africa, and the Middle East. Both rites, as well as some others, are still practiced in Orthodox Jewish communities worldwide.

Coming to grips with a Talmudic text can be demanding. While it is possible to read a page of the Bible in a matter of minutes, depending on the difficulty, a page of Talmud may take an hour or considerably more to go through with understanding. Traditionally it is studied with a partner or ‘friend’ in order to recreate the internal arguments and make sure that the subject in question, whether marriage, business ethics, capital punishment, property law or dietary regulations, has been examined from every conceivable angle.

Judaism centers on a way of life that recognizes the presence of God and the holiness of human life. Beyond embracing the Ten Commandments, the most obvious examples are keeping the Sabbath, observing holy days and festivals, and following dietary practices. Judaism is known for its strong moral and ethical orientation and a focus on everyday life that has led to major contributions in multiple fields that serve humanity, such as medicine and law. There is considerably less emphasis on an afterlife.

The Haggadah

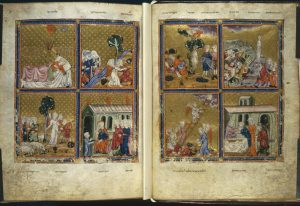

The Haggadah, which literally means ‘telling’, is the Hebrew service book used in Jewish homes on Passover eve to commemorate the Israelites’ miraculous liberation from hundreds of years of slavery in Egypt. Its text is a collection of biblical passages, blessings, legends and rituals arranged into an orderly sequence. The Haggadah is used primarily to teach the young in families about the continuity of the Jewish people and their unflinching faith in God, as summed up in one of its verses:

“And thou shall tell thy son in that day, saying: it is because of that which the Lord did for me when I came forth out of Egypt”. (Exodus 13. 8)

The Haggadah has long inspired artists and remains one of the most frequently illustrated texts in Jewish life. Perhaps because it was mainly intended for use at home, and its purpose was educational, Jewish scribes and artists felt completely free to illustrate the Haggadah. Indeed it was traditionally the most lavishly decorated of all Jewish sacred writings, giving some well-to-do Jews of the middle ages a chance to demonstrate their wealth and good taste as well as their piety through owning elaborate, sometimes gilded versions of the Haggadah.

Passover commemorates one of the most important events in the story of the Jewish people. Like Christianity and Islam, Judaism traces its origins back to Abraham. He was leader of the Israelites, a group of nomadic tribes in the Middle East some 4,000 years ago. Abraham is said to have established a religion that distinguished itself from other local beliefs by having only one, all-powerful God – a God who chose the Jews to be an example to the whole world.

The Israelites became slaves in Egypt, after they came there, according to the story of Joseph, because there was famine in the land of Israel. Eventually, a prophet called Moses delivered the Jews from their captivity with the help of several miraculous events intended to intimidate the Egyptian authorities. The last of these was the sudden death of the eldest son in every family. Jewish households were spared by smearing lambs’ blood above their doors – a sign telling the ‘angel of death’ to pass over.

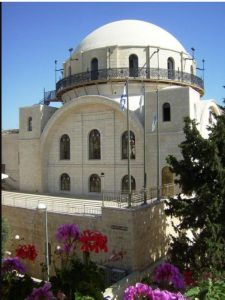

Synagogue Worship and Rituals in Judaism

With some assistance from Rabbi Johnny Solomon[3], we read more about rituals and holidays within Judaism:

Prayer is a part of Jewish life. Rather than prayer being solely personal, as we find in some few prayers in the Torah, it became, after the Diaspora, primarily a communal activity; and rather than worship being spontaneous, it had become highly prescriptive. Collective prayer overtook individual ritual worship. Temple worship often involved one person or one family bringing a sacrifice for prayers. As synagogues developed, prayer turned into a primary activity, and focused on the needs of the congregation.

In the Hebrew Scriptures, Ezekiel wrote:

“Although I have removed them far off among the nations, and although I have scattered them among the peoples, still, I have provided them with a miniature sanctuary in the countries where they have been exiled” (Ezekiel 11. 16)

Some have understood this to be a reference to the institution of the synagogue. First, while the Jewish people were exiled in Babylon, and later, after the destruction of the second temple by the Romans in 70 CE, there was no way for the people to perform tradition rituals. So during both of these times, new activities emerged.

Since the destruction of the temple, the rabbis placed much emphasis on the value of collective worship by speaking about verbal prayer as a replacement for sacrifices (see Hosea 14. 3), by invoking biblical verses such as ‘in the multitude of people is the king’s glory’ (Proverbs 14. 28) and by stating that while private prayer may not always be heard, communal prayer is always heard.

Various rituals in Judaism emerged. Upon waking up in the morning, a Jew recites a prayer. They then wash their hands in a ritual manner and recite a blessing; even the manner in which they get dressed can be informed by Jewish laws and values.

Beyond additional prayers recited at meal times, the home was, and is, also the place

for a variety of Jewish rituals, such as the circumcision of Jewish boys that takes place – ideally – when they are eight days old. For girls, naming and dedication ceremonies developed to take place when the baby was that same age.

Beyond this, while the synagogue and the home reflected the different aspects of formal and informal, and public and private worship, a third institution played critical role in Jewish communities for the past 2,000 years – namely, the house of study. The book of Joshua relates how Torah should be studied day and night (Joshua 1. 8). In every village, town or city where Jews lived, the study house would be where Jews (although historically this refers primarily to male Jews) would gather to study sacred texts such as the Talmud, or listen to lectures delivered by leading rabbinical scholars exploring legal or ethical teachings.

Various community holidays also emerged, as Jewish life become more formalized.

All Jewish holidays begin the evening before the date specified. This is because they believe that a day begins and ends at sunset. In reading the story of creation in Genesis 1, it says, “And there was evening, and there was morning, one day.” From this it is concluded that a day begins with evening, that is, at sunset. In addition, the Jewish calendar is lunar, with each month beginning on the new moon. So the dates of holidays vary, depending on the moon cycle. The most commonly celebrated holidays include:

- Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year

- Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, asking for forgiveness and repairing relationships (see this reflection on repair: Repair)

- Passover, the 8 day festival in the spring, celebrating the Exodus–the rescue from Egyptian slavery, led by Moses

- Hanukkah, a minor holiday that commemorates the miraculous victory of the Maccabees and rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem. NOT the equivalent of Christmas!

- Purim, the carnival style celebration of foiling an attempt to kill Persian Jews

Other holidays include celebration of harvest, of the end of the year reading of the Torah, bar and bat mitzvahs (coming of age ceremonies for children) and other community activities.

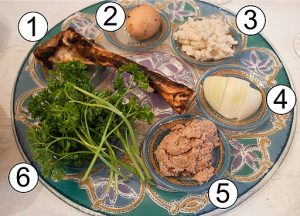

Many people have heard the term Kosher, but apply it more in slang terms to mean “genuine” or “legitimate”. In Jewish ritual, however, the concept of something being Kosher describes food that meets the standards of kashrut, which is a set of laws dealing with what foods can and cannot be eaten, and how they are to be prepared. The term Kosher is also used to describe ritual objects that are made in accordance with Jewish law and are fit for ritual use.

Although the details of kashrut are extensive, the laws all derive from a few fairly simple, straightforward rules[4]:

Although the details of kashrut are extensive, the laws all derive from a few fairly simple, straightforward rules[4]:

- Animals allowed to be eaten must have cloven hooves. This includes addax, antelope, bison, cow, deer, gazelle, giraffe, goat, ibex and sheep. In addition, kosher meat and poultry require special preparation. Birds allowed, at least in the US, are duck, turkey, chicken and goose. Fish must have a specific kind of scale and skin in order to be eaten. Pork and shellfish are specifically forbidden.

- Of the animals that may be eaten, the birds and mammals must be killed in accordance with Jewish law and using kosher equipment.

- All blood must be drained from the meat or broiled out of it before it is eaten.

- Certain parts of permitted animals may not be eaten, such as the back half of the cow, some internal organs where removing the blood is almost impossible, etc.

- Meat (the flesh of birds and mammals) cannot be eaten with dairy. Fish, eggs, fruits, vegetables and grains can be eaten with either meat or dairy. According to some views, however, fish may not be eaten with meat.

- Cooking equipment that has come into contact with meat may not be used in cooking with dairy, and vice versa. Utensils that have come into contact with non-kosher food may not be used with kosher food.

- Grape products made by non-kosher processes may not be consumed. This include jellies, pastries, juice and wine.

Keeping a kosher lifestyle and kitchen is considered a sign of obedience, even while some believe that these were early health restrictions, eating kosher is considered a sign of faith. Not all Jews follow the dietary laws, but all Orthodox and many Conservative Jewish people do.

Basic Beliefs

The earliest nomadic Hebrews were polytheistic, believing, as many groups in the Middle East did, in various deities representing different forces of nature such as fertility, agriculture, sun, rain, and so on. Eventually, however, early Hebrew prophets began to speak of just one God as the creator of all. Early Biblical authors gave God names such as Elohim (gods), Adonai (my lord), El Shaddai, (God almighty) and the tricky YHWH, which comes from the same root as the verb “to be,” sometimes written in English as Yahweh. God says, “I am who I am” in Exodus, when Moses asks for a name to use. It has also been translated as “I will be who I will be” or “I will become who I choose to become”. This intangible nature of God is part of the both immanent and transcendent nature of the divine in Jewish thought.

Example: one image of the divine

A coin from Gaza in Southern Philista, fourth century BC, the period of the Jewish subjection to the last of the Persian kings, has the only known representation of this Hebrew deity. The letters YHW are incised just above the hawk(?) which the god holds in his outstretched left hand, Fig. 23. He wears a himation, leaving the upper part of the body bare, and sits upon a winged wheel. The right arm is wrapped in his garment. At his feet is a mask. Because of the winged chariot and mask it has been suggested that Yaw had been identified with Dionysus on account of a somewhat similar drawing of the Greek deity on a vase where he rides in a chariot drawn by a satyr. The coin was certainly minted under Greek influence, and consequently others have compared Yaw on his winged chariot to Triptolemos of Syria, who is represented on a wagon drawn by two dragons. It is more likely that Yaw of Gaza really represents the Hebrew, Phoenician and Aramaic Sun-god, El, Elohim, whom the monotheistic tendencies of the Hebrews had long since identified with Yaw…Sanchounyathon…based his history upon Yerombalos, a priest of Yeuo, undoubtedly the god Yaw, who is thus proved to have been worshipped at Gebal as early as 1000 BC.

A coin from Gaza in Southern Philista, fourth century BC, the period of the Jewish subjection to the last of the Persian kings, has the only known representation of this Hebrew deity. The letters YHW are incised just above the hawk(?) which the god holds in his outstretched left hand, Fig. 23. He wears a himation, leaving the upper part of the body bare, and sits upon a winged wheel. The right arm is wrapped in his garment. At his feet is a mask. Because of the winged chariot and mask it has been suggested that Yaw had been identified with Dionysus on account of a somewhat similar drawing of the Greek deity on a vase where he rides in a chariot drawn by a satyr. The coin was certainly minted under Greek influence, and consequently others have compared Yaw on his winged chariot to Triptolemos of Syria, who is represented on a wagon drawn by two dragons. It is more likely that Yaw of Gaza really represents the Hebrew, Phoenician and Aramaic Sun-god, El, Elohim, whom the monotheistic tendencies of the Hebrews had long since identified with Yaw…Sanchounyathon…based his history upon Yerombalos, a priest of Yeuo, undoubtedly the god Yaw, who is thus proved to have been worshipped at Gebal as early as 1000 BC.

According to prophecy and stories throughout the early parts of the Bible, the God the Hebrews encountered was all-powerful and benevolent, merciful and just. Hebrew writings do not represent God in any visual way, but describe this god as a universal God, engaged in a lasting relationship with humankind and in a more specific covenant with the people of Israel. Various leaders and prophets have spoken about this relationship, and are honored–Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob, Leah and Rachel (the patriarchs and matriarchs) as well as Moses, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and many more.

The ancient Hebrews write in Exodus about the laws that came directly from God. We see this in both the 10 Commandments, well known to the world, but also in the development of more detailed laws regulating Jewish life, ritual, and worship. According to the Hebrew people, God is not abstract or distant, but is actively involved in history through revelation and as the people do or do not live out their covenant with God. Throughout Jewish history, the common thread has been God’s relationship with humanity. It is a covenant based on centuries of tradition, belief and ritual.

There is a belief in the existence of human free will, which is what determines good and evil, and this idea leads ultimately to a belief in human freedom and dignity.

Judaism is not a missionary religion. It accepts converts, but it is up to individual congregations and their process as to how that would work.

Traditionally, the Jewish people live in expectation of the coming of a Messianic Age in which universal peace will be established on earth according to the vision of the prophets of Israel.

One is judged by one’s actions–one lives the faith and tradition by deeds, not be claiming a creed of any sort. The basic statement of faith is the Shema’–“Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One”. Shema means, literally, “listen, heed, hear and do”.

A summary is stated well by the Harvard Pluralism Project:

“Jews today continue to pride themselves on the fact that the ethical monotheism of Judaism is the basic building block of Western religion. The idea of one God unites broad human communities historically, religiously, and culturally to the present day.”

Key Takeaway: One more Food for Jewish Thought

“Judaism in Brief.” Harvard University: Judaism Through Its Scriptures, HarvardX, 19 Apr. 2017, youtu.be/2sOzmBAaCHA.

“Discovering Sacred Texts: Judaism.” Discovering Sacred Texts: The British Library, 2 Oct. 2019, youtu.be/39MQJuX9A9g.

Solomon, Johnny. “Jewish Prayer at Home and in the Synagogue.” British Library, Sacred Texts, 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/jewish-prayer-at-home-and-in-the-synagogue.

“Babylonian Talmud” British Library, 2021, www.bl.uk/collection-items/babylonian-talmud.

“Religious and Spiritual Life.” UMass Amherst, 2021, www.umass.edu/orsl/about-jewish-holidays.

History, Center for Jewish. Center for Jewish History, 2021, www.cjh.org/.

Harchol, Hanan. “FAITH (Jewish Food for Thought).” Jewish Food for Thought, 3 Nov. 2013, youtu.be/YZ7A34luj40.

Harchol, Hanan. “Repair (Theme: Apology) – Jewish Food for Thought, the Animated Series.” Jewish Food for Thought, 11 Sept. 2011, youtu.be/IpDY260Jbpg.

- Simon Schama is University Professor of Art History and History at Columbia University and a Contributing Editor of the Financial Times. He is the author of 16 books and the writer-presenter of more than 40 documentaries on art, history and literature for BBC2. His art criticism for The New Yorker won the National Magazine Award for criticism in 1996; his film on Bernini from The Power of Art won an Emmy in 2007 and his series on British history and The American Future: a History, won the Broadcast Critics Guild awards. He won the NCR non-fiction prize for Citizens, National Book Critics Circle award for Rough Crossings, the WH Smith Literary Award for Landscape and Memory. He writes on cooking and food for GQ; fashion for Harper’s Bazaar and on everything else for the Financial Times. He curated the Government Art Collection show Travelling Light at the Whitechapel Gallery in London and has collaborated with Anselm Kiefer, John Virtue and Cecile B. Evans on contemporary art exhibitions and installations. His latest project is The Story of the Jews, which was broadcast on BBC2 in the UK and published as a book in autumn 2013. The second volume of The Story of the Jews is due to be published in autumn 2014. ↵

- Maryanne Saunders is a PhD candidate in the Theology and Religious Studies Department, King’s College London. Her research interest is religious modern and contemporary art with a particular focus on gender and sexuality. ↵

- Rabbi Johnny Solomon is a lecturer in Jewish Thought and Jewish Law and an independent Jewish education consultant to numerous Jewish schools and adult education programs. He has written numerous articles about contemporary Jewish law and trends in contemporary Orthodoxy, and he is currently completing his first book exploring the relevance of the ‘Sheheheyanu’ blessing. ↵

- If you want more extensive information, this page at the Orthodox Union website will help: https://oukosher.org/the-kosher-primer/ ↵