8 Buddhism

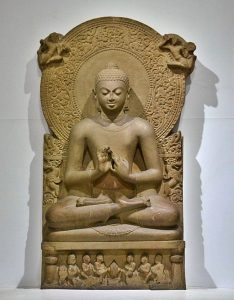

Originating in northern India in the 5th-6th century BCE Buddhism is concerned with the universal searching for enlightenment. The Buddha lived as Prince Siddhartha Gautama before renouncing his family as an adult and leaving his life of privilege in search of enlightenment. The Buddha lived and taught in north-east India in the 5th century BCE, dying in his eightieth year. The Theravāda tradition puts his death in 486 BCE, while the Mahāyāna tradition has it in 368 BCE. Recent scholarly research suggests his most likely dates were 484–404 BCE.

Telling the Story of Buddha: Siddhartha Gautama

The excellent PBS documentary film: The Buddha (there are transcripts beneath the video if you would rather read this material)

Buddhism teaches that all of life is suffering, caused by desire. To cease suffering one must end desire and this can be achieved through following the Noble Eight-fold Path (eight rules that guides the life and morals of a follower). Buddhists believe that all actions bring reward or retribution.

Buddha rejected many aspects of the Hinduism traditions and beliefs of his day. These included rejecting the caste system, an emphasis on rituals, and the belief in a permanent spiritual reality. He accepted Hindu ideas on karma and rebirth and the notion of liberation, which he called nirvana instead of moksha. In the centuries after his death, several schools emerged that eventually crystallized into the great branches of Buddhism recognized today: Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana.

Branches

Theravada is the only surviving conservative school whose goal was to pass on the Buddha’s teachings unchanged. Theravada Buddhism centers on the interdependence of the community of monks with ordinary people. Monks pursue nirvana supported by the people, who gain merit (good karma) by providing them with food, clothing, and provisions for the monastic life. Monks, in turn, are role models who offer advice, and run schools, meditation centers, and medical clinics. “In Theravada (Southern) Buddhist countries, the monks (bhikkhus) are easily recognized because they wear the characteristic orange robe, have their heads shaven, and go about barefoot. They are given a new name and the robe, and will live according to a code of 227 rules (the Vinaya). A monk may decide to disrobe (cease being a monk) at any time.”[1]

Theravada is the only surviving conservative school whose goal was to pass on the Buddha’s teachings unchanged. Theravada Buddhism centers on the interdependence of the community of monks with ordinary people. Monks pursue nirvana supported by the people, who gain merit (good karma) by providing them with food, clothing, and provisions for the monastic life. Monks, in turn, are role models who offer advice, and run schools, meditation centers, and medical clinics. “In Theravada (Southern) Buddhist countries, the monks (bhikkhus) are easily recognized because they wear the characteristic orange robe, have their heads shaven, and go about barefoot. They are given a new name and the robe, and will live according to a code of 227 rules (the Vinaya). A monk may decide to disrobe (cease being a monk) at any time.”[1]

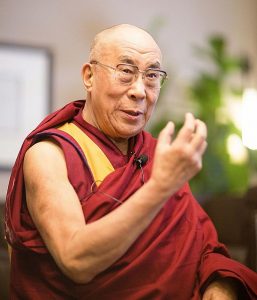

The Mahayana branch subdivided into many different schools and introduced innovations in teachings and the practice of Buddhist life for ordinary people. The Mahayana ideal was the deeply compassionate person called a bodhisattva, who refused to fully enter nirvana, but stayed among people to help others end their suffering. The historical Buddha was deemphasized by a worldview that saw the universe populated by many Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Major schools of this form of Buddhism include Shingon, Tendai, Pure Land, Nichiren, and Zen. In Mahayana (Northern) Buddhist countries there are two main branches, the Tibetan with monks wearing the characteristic maroon robe, and the Far Eastern Zen, which also has an unbroken line of nuns, where the robes are black or grey.

The Mahayana branch subdivided into many different schools and introduced innovations in teachings and the practice of Buddhist life for ordinary people. The Mahayana ideal was the deeply compassionate person called a bodhisattva, who refused to fully enter nirvana, but stayed among people to help others end their suffering. The historical Buddha was deemphasized by a worldview that saw the universe populated by many Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Major schools of this form of Buddhism include Shingon, Tendai, Pure Land, Nichiren, and Zen. In Mahayana (Northern) Buddhist countries there are two main branches, the Tibetan with monks wearing the characteristic maroon robe, and the Far Eastern Zen, which also has an unbroken line of nuns, where the robes are black or grey.

Associated with Tibetan Buddhism, Vajrayana combines Mahayana principles of living and teaching with various ritual practices incorporating mantras, mudras, and mandalas. An interesting feature is the transmission of leadership through reincarnations of other lamas (leaders). “Tibetan Buddhism is to be found not only in Tibet, but right across the Himalayan region from Ladakh to Sikkim, as well as parts of Nepal. It is the state religion of the kingdom of Bhutan. It also spread to Mongolia and parts of Russia (Kalmykia, Buryatia and Tuva) Tibetan refugees have brought it back to India, where it can be found in all the many Tibetan settlements. In modern times it has become very popular in the West. Tibetan Buddhism takes as its motivating spiritual ideal the way of the bodhisattva, the altruistic intention to attain enlightenment for all beings. All Tibetan traditions place special emphasis on the teacher-student relationship. This distinctive approach is based on the Indian ideal of the guru (Lama in Tibetan). The Vajrayana or Tantra is not considered separate from the Mahayana, but has a special connection within it, as it is based on an altruistic Mahayana motivation. Tantra is a path of transformation in which you work under the guidance of a suitably qualified teacher to allow you to access subtler and deeper states of consciousness such as transforming the emotions and ego.”[2]

Four Noble Truths

- Dukkha –all life is suffering, as one is incapable of finding ultimate satisfaction. This is an innate characteristic of existence in the realm of samsara (the life cycle that includes reincarnation);

- Samudaya–the origin, the arising of this suffering is craving, desire, wanting. Dukkha comes together with this taṇhā (“craving, desire or attachment”);

- Nirodha– the cessation, the ending of this dukkha, this suffering, can be attained by the renouncement or letting go of this taṇhā, the craving and desire;

- Magga–the way one gets rid of craving is through the path, the Noble Eightfold Path. This is the path leading to renouncement of tanha and cessation of dukkha.

The eight Buddhist practices in the Noble Eightfold Path are:

- Right View: our actions have consequences, death is not the end, and our actions and beliefs have consequences after death.

- Right Resolve or Intention: the giving up of home and adopting the life of a religious mendicant in order to follow the path; this concept aims at peaceful renunciation, into an environment of non-sensuality, non-ill-will (to loving kindness), away from cruelty (to compassion).

- Right Speech: no lying, no rude speech, no telling one person what another says about him to cause discord or harm their relationship.

- Right Conduct or Action: no killing or injuring, no taking what is not given, no sexual acts, no material desires.

- Right Livelihood: beg to feed, only possessing what is essential to sustain life;

- Right Effort: preventing the arising of unwholesome states, and generating wholesome states,

- Right Mindfulness: “retention”, being mindful of the dhammas (“teachings”, “elements”) that are beneficial to the Buddhist path.

- Right Concentration: practicing four stages of dhyāna (“meditation”), which culminates into equanimity and mindfulness. In the Theravada tradition and the Vipassana movement, this is interpreted as concentration or one-pointedness of the mind, and supplemented with meditation, which aims at insight.

The Three Fires

(1) Desire/Thirst, (2) Anger (3) Delusion

“Your house is on fire, burns with the Three Fires; there is no dwelling in it’ – thus spoke the Buddha in his great Fire Sermon. The house he speaks of here is the human body; the three fires that burn it are (1) Desire/Thirst, (2) Anger and (3) Delusion. They are all kinds of energy and are called ‘fires’ because, untamed, they can rage through us and hurt us and other people too! Properly calmed through spiritual training, however, they can be transformed into the genuine warmth of real humanity.” [3]

Buddhists promotes virtues such as kindness, patience and generosity. The virtues of wisdom and compassion are valued most of all. Ahimsa or harmlessness, connected with a respect for all things, is described, in part, by the term compassion. This desire to cause no harm to all beings includes animals, plants, and the world in general. In addition, this is a tradition that asks one to think and reflect on all one’s actions. Buddha himself told his followers not to believe statements or teachings without questioning, but to test each one for themselves.

Buddhists try to practice these Buddhist virtues actively in their everyday lives. The final goal of all Buddhist practice is to bring about that same awakening that the Buddha himself achieved through an active transformation of the heart and passions and the letting go of “self”.

Summary information about Buddhism: Harvard University

The term ‘Buddha’ is not a name but a title, meaning ‘Awakened One’ or ‘Enlightened One’. The man Siddhartha Gautama is not seen as unique in being a Buddha, as Buddhas are seen to have arisen in past eons of the world, and will do so in future. They are not incarnations of a God, but humans who have developed ethical and spiritual perfections over many lives. A Buddha is seen as one who becomes awakened to the true nature of reality, and awakened from ingrained greed, hatred and delusion. They are enlightened in being able to clearly see the nature of the conditioned world, with its many worlds in which beings are reborn, and Nirvana, the timeless state beyond all rebirths. Moreover a Buddha is seen as a wise and compassionate teacher who shows people the path beyond suffering.

Devotees founded temples and monasteries and sponsored the writing of holy texts.

Read and watch a short video about the development of Buddhist Texts

Peter Harvey[4] has written for the British Library about the development of sacred texts within the varied branches of Buddhism. The article begins with a longer description of the enlightenment of Buddha, and then moves into talking about Buddhist Texts.

“How were the Buddha’s teachings collected?

Soon after his death, 500 disciples who were enlightened Arahats, free of further rebirth, gathered to agree what he had taught, and arranged these into two kinds of text that could be communally chanted: Vinaya, on monastic discipline, and the Suttas, or discourses. At that time, writing was little used in India, but there was a well-developed tradition of passing on detailed texts orally. Different group of monks in time had slightly different versions that they passed on, but there is a remarkable overall agreement. The form preserved by the Theravāda school, in Pāli, was written down for the first time around 20 BCE in Sri Lanka, running to over 40 modern volumes.

The Suttas do not focus on the person of the Buddha, but his Dhamma (Pāli, Sanskrit Dharma): his teachings, the realities they point to, especially the nature of the world and the Path to Nirvana, and experiences on the Path, culminating in Nirvana. The Buddha said, though, that ‘he who sees the Dhamma sees me’.”

As the Buddha’s teachings spread across Asia, different sects stressed particular aspects of the quest for enlightenment. In addition to spreading the practices and beliefs of Buddha, it is also true that Buddhism had a strong influence on the early trade routes in Asia. Buddhism started its development from India, and reached other regions along what are known as the Silk Roads. Because beliefs moved along the trade routes, as well as material goods, Buddhism practices changed from place to place, developing within particular communities according to the traditions of those cultures. Buddhist monasteries were built and established along the developing trade routes, so that one would say that these faith communities were linked to economic growth. The commercial exchanges that occurred contributed to the improvement of the Buddhist monks’ lives. Because of the Buddhist concept of Dāna (generosity), monks received contributions from the merchants and traders along the Silk Roads. In return, monks provided spiritual guidance.

The development of trade amongst merchants of the region along the Silk Roads resulted in a further expansion of Buddhism towards eastern Asian lands, including in Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia. In addition, Buddhism moved north, to Japan, Korea, and areas in northern China. Goods and travelers from the Silk Roads moved north and Buddhism was one of the most influential imports brought to Japan along the trade routes. The ancient capital city of Nara, Japan, contains many Buddhist temples. Valuable items from the Silk Roads merchants and travelers are found in Nara’s Shosoin Treasure Repository of the Emperor.

Ted Talks from practitioners of Buddhism

Buddhism has spread well beyond Asia, and is somewhat familiar even in Western Countries. Check out these stories and reflections from Western Buddhists.

“Buddhism.” The British Library, The British Library, 20 Sept. 2018, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/themes/buddhism.

Harvey, Peter. “The Buddha and Buddhist Sacred Texts.” Discovering Sacred Texts, The British Library, 21 Sept. 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-buddha-and-buddhist-sacred-texts.

The Buddhist Society: The Spread of Buddhism, 2021, www.thebuddhistsociety.org/page/the-spread-of-buddhism.

“The Silk Roads Programme.” UNESCO Silk Roads Programme | Silk Roads Programme, 2021, en.unesco.org/silkroad/.

“Buddhism in Brief.” Buddhism in Brief, Harvard University, 19 Apr. 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=pG4R-rmX7HA.

“The Buddha.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 2010, www.pbs.org/thebuddha/.

“The Buddhist Review – The Independent Voice of Buddhism in the West.” Tricycle, 2021, tricycle.org/.

Puddicombe, Andy. “All It Takes Is 10 Mindful Minutes.” TED, Ted Talks, 2012, www.ted.com/talks/andy_puddicombe_all_it_takes_is_10_mindful_minutes.

Ricard, Matthieu. “The Habits of Happiness.” TED, Ted Talks, 2004, www.ted.com/talks/matthieu_ricard_the_habits_of_happiness.

Thurman, Robert. “We Can Be Buddhas.” TED, Ted Talks, 2006, www.ted.com/talks/robert_thurman_we_can_be_buddhas.

- https://www.thebuddhistsociety.org/page/the-spread-of-buddhism ↵

- https://www.thebuddhistsociety.org/page/tibetan-buddhism/ ↵

- https://www.thebuddhistsociety.org/page/fundamental-teachings ↵

- Peter Harvey is Emeritus Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Sunderland. He was one of the two founders of the UK Association for Buddhist Studies and edits its journal, Buddhist Studies Review. His books include An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices (Cambridge University Press, 1990, and 2013), An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics: Foundations, Values and Issues (Cambridge University Press, 2000), and The Selfless Mind: Personality, Consciousness and Nirvana in Early Buddhism (Curzon, 1995), and he has published many papers on early Buddhist thought and practice and on Buddhist ethics. Most recently, he edited an extensive integrated anthology of Buddhist texts, Common Buddhist Text: Guidance and Insight from the Buddha (2017) published for free distribution by Mahachulalongkorn-rajavidyalaya University, Thailand. ↵