2 The Countryside and The West

The People’s Party

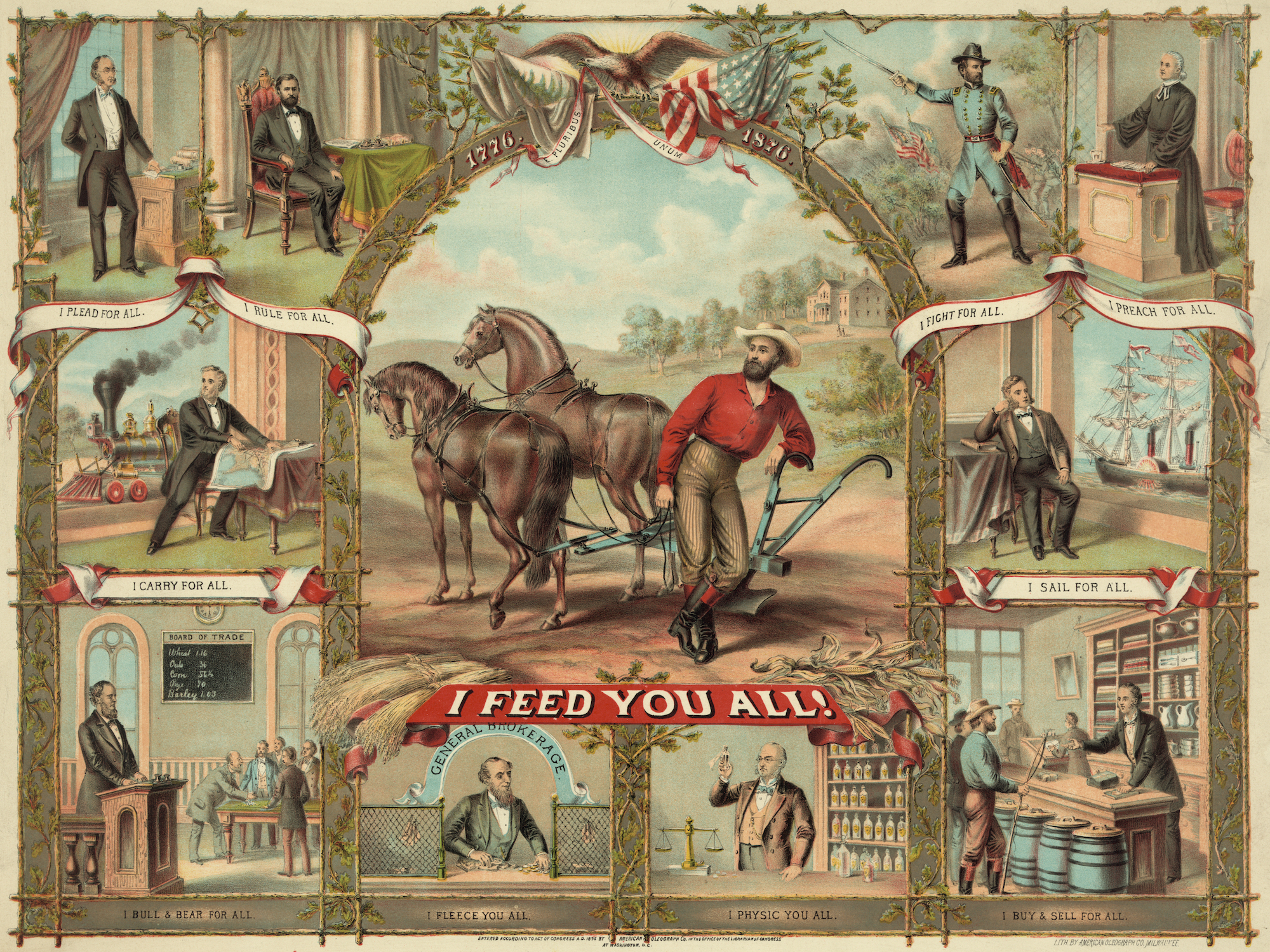

“Wall Street owns the country,” the Populist leader Mary Elizabeth Lease told dispossessed farmers around 1890. “It is no longer a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street, and for Wall Street.” Farmers, who remained a majority of the American population through the first decade of the twentieth century, were hit especially hard by industrialization. The expanding markets and technological improvements that increased efficiency also decreased commodity prices. Commercialization of agriculture put farmers at the mercy of bankers, railroads, and large equipment manufacturers like McCormick. Fluctuating global commodity markets caused wide swings in the prices farmers could get for their produce. Many farmers fell ever further into debt, lost their land, and were forced to enter the industrial workforce or, especially in the South, become landless farmworkers.

The rise of industrial giants reshaped the American countryside and the Americans who called it home. Railroad spur lines, telegraph lines, and credit arrived in farming communities and linked rural Americans with towns, regional cities, financial centers in Chicago and New York, and world markets. Meanwhile, improved farm machinery, easy credit, and the latest consumer goods flooded the countryside. But new connections and new conveniences came at a price. Farmers found their financial security depended on a national economic system subject to rapid price swings, rampant speculation, and limited regulation. Many came to believe the system enriched “parasitic” bankers and industrial monopolists at the expense of the many laboring farmers who fed the nation by producing its many crops and farm goods. Their dissatisfaction with an erratic and impersonal system put many of them at the forefront of what would become perhaps the most serious challenge to the established political economy of Gilded Age America. Farmers organized and launched their challenge first through cooperatives and the Farmers’ Alliance and later through the politics of the People’s (or Populist) Party.

Mass production and corporate consolidations spawned giant trusts that monopolized nearly every sector of the U.S. economy in the decades after the Civil War. In contrast, the economic power of the individual farmer was threatened by plummeting commodity prices and rising indebtedness. Farmers met in Lampasas, Texas in 1877 and organized the first Farmers’ Alliance to try to regain some economic power as they negotiated with railroads, merchants, and bankers. Farmers reasoned that if they banded together, they might gain economic leverage similar to that of big business. They could share machinery, bargain collectively with both suppliers and wholesalers, to negotiate higher prices for their crops. Cooperatives were a well-established economic tool that had been popular with liberal reformers in Great Britain and America since the early nineteenth century. Organizers spread from town to town across the South, the Midwest, and the Great Plains, holding evangelical-style camp meetings, distributing pamphlets, and establishing over one thousand alliance newspapers. As the alliance spread, so too did its near-religious vision of the nation’s future as a “cooperative commonwealth” that would protect the interests of the many from the predatory greed of the few. At its peak, the Farmers’ Alliance claimed 1,500,000 members meeting in 40,000 local sub-alliances.

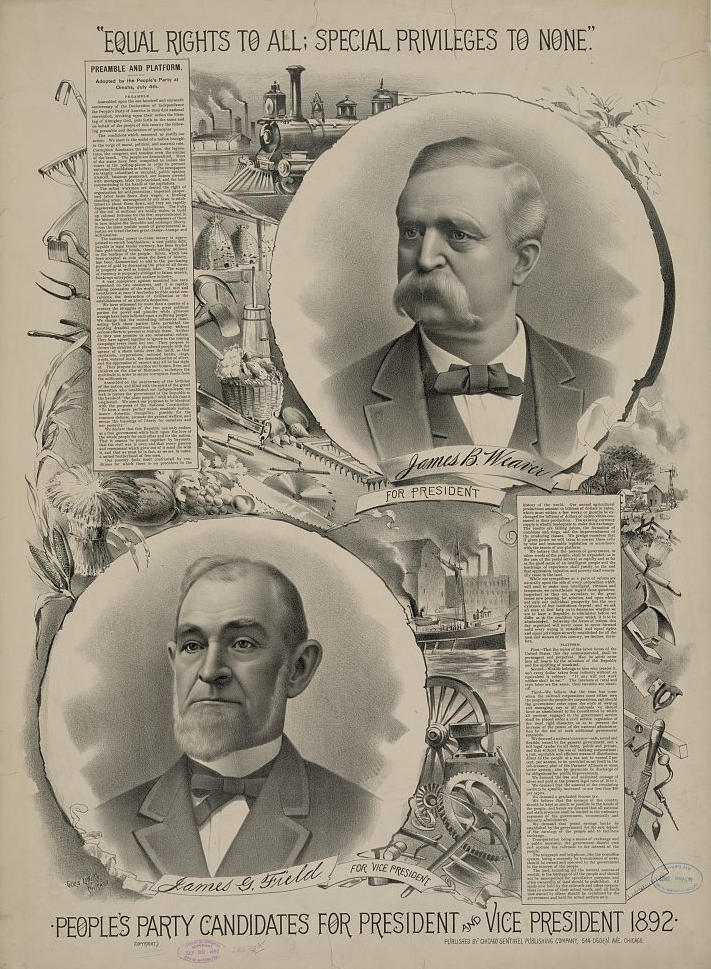

The alliance’s cooperatives spread across the South between 1886 and 1892 and reached more than a million members at their high point. While most failed financially, these “philanthropic monopolies,” as one alliance speaker termed them, inspired farmers to organize to address their economic difficulties. But cooperation was only part of the alliance message; another was political organizing. In the South, alliance-backed Democratic candidates won four governorships and forty-eight congressional seats in 1890. But at a time when falling prices and rising debts seemed to threaten the survival of family farmers, the two major political parties seemed incapable of representing the needs of poor farmers. So alliance members organized their own political party: the People’s Party, also known as the Populists. The party attracted supporters across the nation by criticizing the deep flaws they saw in the political economy of Gilded Age America, problems that both major political parties refused to address. Veterans of earlier fights for currency reform and silver coinage, disaffected industrial laborers, proponents of the benevolent socialism described in Edward Bellamy’s bestselling novel Looking Backward, and champions of Henry George’s farmer-friendly “single-tax” proposal (from his popular book, Progress and Poverty) joined Farmers’ Alliance members in the new party. The People’s Party nominated former Civil War general James B. Weaver as their presidential candidate at their first national convention in Omaha, Nebraska, on July 4, 1892.

At the Omaha convention, Populists adopted a platform that crystallized the alliance’s cooperative programs into a coherent political vision. The platform’s preamble, written by Minnesota Populist Ignatius Donnelly, warned that “the fruits of the toil of millions [had been] boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few.” The Omaha Platform and the larger Populist movement sought to counter the scale and power of monopolistic capitalism with an engaged, modern, and equally powerful federal government. The platform proposed nationalizing the country’s railroad and telegraph systems to ensure that essential services would be run in the interests of the people rather than for the profits of wealthy investors. To deal with the lack of currency and credit available to farmers, the platform advocated postal savings banks. It called for the establishment of a network of federally managed warehouses called sub-treasuries, which would extend government loans to farmers who stored crops in the warehouses as they awaited higher market prices. To aid debtors, Populists promoted an inflationary monetary policy that could be achieved by remonetizing silver. The platform called for direct election of senators and the secret ballot to ensure that the federal government would serve the people rather than entrenched partisan interests. Finally, a graduated income tax would protect Americans from the establishment of an American aristocracy. Populists believed these efforts would help shift economic and political power back toward the nation’s producing classes.

In the Populists’ first national election campaign in 1892, Weaver received over one million votes and twenty-two electoral votes; a startling performance for a third party that seemed to signal a bright future for the People’s Party. When the Panic of 1893 exacerbated the Long Depression, the Populist movement won further credibility and gained even more ground. Kansas orator Mary Lease, one of the movement’s most fervent speakers, admonished farmers to “raise less corn and more Hell.” Populist stump speakers crossed the country and blamed the greed of business elites and corrupt party politicians for causing the crisis fueling America’s widening inequality. Southern orators like James “Cyclone” Davis of Texas and Georgia firebrand Tom Watson stumped across the South decrying the abuses of northern capitalists and the Democratic Party. Pamphlets such as W. H. Harvey’s Coin’s Financial School and Henry D. Lloyd’s Wealth Against Commonwealth provided Populist perspectives on economic issues. In the 1894 elections, Populists elected six senators and seven representatives to Congress. A third party seemed successfully launched in American politics.

Populism, however, still faced substantial obstacles, especially in the South. The failure of Alliance-backed Democrats to live up to their campaign promises had driven some southerners to break with the party of their forefathers and join the Populists. Southern Democrats responded to the Populist challenge with electoral fraud and racial demagoguery. The Farmer’s Alliance had failed to challenge the pervasive white supremacy of the American South in their call for a grand union of the producing classes. Their constitution had banned black membership, citing as an excuse that the Alliance was a social organization “where we meet with our wives and daughters.” Black farmers responded by establishing the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance and Cooperative Union in 1886. Their organization spread quickly and grew to 1.2 million members by 1891. But Southern racism was formidable. The Colored Farmers’ Alliance fell into rapid decline after the white Farmer’s Alliance actually attacked the group for sponsoring strikes of cotton pickers. Racial mistrust and division remained the rule, even among aggrieved farmers. Populists opposed the corruption of the two major parties, but this did not necessarily make them champions of interracial democracy. As North Carolina’s Populist Senator, Marion Butler explained to an audience of his constituents, “We are in favor of white supremacy, but we are not in favor of cheating and fraud to get it.” Unfortunately, across much of the South, Populists and Farmers’ Alliance members were often at the forefront of the movement for disfranchisement and segregation.

Despite its racial failures, Populism exploded in popularity. The first major political movement to tap into the discomfort of many Americans with the disruptions created by industrial capitalism, the People’s Party seemed poised to capture political victory. And yet, even as Populism gained national traction, the movement was stumbling. The party’s leaders found it difficult to shepherd what remained a diverse and loosely organized coalition of reformers toward unified political action. The Omaha platform was a radical document, and some state party leaders preferred to pick and choose from among the reforms it proposed. More importantly, the major parties were too strong and too well organized, and the Democrats were preparing to co-opt many Populist ideas and inaugurate a new era of American politics.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did the People’s Party gain influence so quickly in American politics?

- What prevented the Populists from becoming a permanent third party?

Bryan, McKinley, Debs

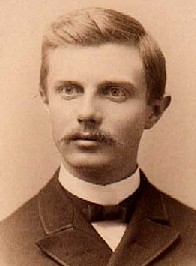

Two of the most famous politicians of this era were someone who seemed to be a Populist, William Jennings Bryan, and an actual Socialist, Eugene V. Debs. Bryan (1860–1925) had a famous career as an accomplished orator, a Nebraska congressman, a three-time presidential candidate, U.S. Secretary of State under Woodrow Wilson, and a lawyer who supported prohibition and opposed Darwinism in the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial. Although Bryan was unsuccessful in winning the presidency, his incorporation of many Populist ideas into the rhetoric of the Democratic Party altered the course of American political history.

When the Long Depressions worsened in the Midwest in the late 1880s, despairing farmers faced low crop prices and found few politicians on their side. Many rallied to the Populist cause, but Bryan worked from within the Democratic Party, winning election to the Nebraska House of Representatives, where he served for two terms. In 1895, Bryan launched a national speaking tour to promote the free coinage of silver. He believed that reissuing silver dollars, by inflating American currency, could alleviate farmers’ debts. In contrast, Republicans championed the gold standard and a flat money supply that would retain the value of accumulated wealth. The Democratic Party’s 1896 national convention nominated Bryan for president on a platform asserting that the gold standard was “not only un-American but anti-American.” Bryan spoke last at the convention, declaring, “we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” After a few seconds of stunned silence, the convention went wild.

The Republicans nominated William McKinley, an economic conservative who had written the Tariff Act of 1890 and who championed business interests and the gold standard. Bryan crisscrossed the country spreading the silver gospel. The election drew enormous attention and emotion. The pro-business Republicans outspent Bryan’s campaign fivefold. An unusually high 79.3 percent of eligible American voters cast ballots in the 1896 election and turnout averaged 90 percent in areas supporting Bryan, but Republicans won the population-dense Northeast and Great Lakes regions and California, delivering the Presidency to their man. In early 1900, Congress passed the Gold Standard Act, which effectively ended the debate over the nation’s monetary policy. Bryan ran again in 1900 and 1908, without success. McKinley signed the Dingley Tariff in 1897, which raised duties on foreign products to their highest level in history (52%). After beating Bryan again in 1900, McKinley was assassinated early in his second term in 1901 by Leon Czolgosz, an unemployed anarchist steelworker.

William Jennings Bryan was among the most influential losers in American political history. When the agrarian wing of the Democratic Party nominated the Nebraska congressman in 1896, Bryan’s fiery condemnation of northeastern financial interests and his impassioned calls for “free and unlimited coinage of silver” co-opted popular Populist issues. The Democrats were able to siphon off a large part of the Populists’ political support, but were unable to beat McKinley. Populist energy moved from the radical (but new and weak) People’s Party to the moderate (but old and powerful) Democratic Party. But energy for reform was weakened as many radicals refused to move toward the center and join the Democrats. However, although at first glance the Populist movement appears to have been a failure, the agrarian revolt established the roots of later reform. Nearly all of the policies outlined in the Omaha Platform would eventually be enacted into law over the following decades under the management of middle-class reformers. To a great extent, the Populist vision laid the foundation for the coming Progressive movement.

Some American socialists carried on the Populists’ radical tradition by continuing the effort to unite farmers and wage-workers in a sustained political struggle to reform American economic life. Socialists argued that wealth and power were in the hands of too few individuals, that monopolies and trusts controlled too much of the economy, and that owners and investors grew rich while the workers who had produced their wealth suffered from low pay, long hours, and unsafe working conditions. The early nineteenth-century political philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon had declared. “What is property?…It is robbery!” Later nineteenth-century philosopher Karl Marx described the new industrial economy as a worldwide class struggle between the wealthy bourgeoisie, who owned the means of production such as factories and large farms, and the proletariat, factory workers and tenant farmers who toiled only for the wealth of others. Marx and many of his followers believed that all the value in the economy was derived from labor. This was clearly not accurate, unless the term labor was given a definition wide enough to include not only “labor-saving” machinery but the intellectual work that went into designing new technologies, implementing them in factories, and then managing the new production processes. But Marx’s idea did focus attention on the fact that much accumulated wealth was the product of past labor, and that a lot of wealth accrued to people who did not do the work rather than to those who did. Ownership of capital assets (the “means of production”) seemed to be a key feature in hanging onto the profits, which workers believed was unjust.

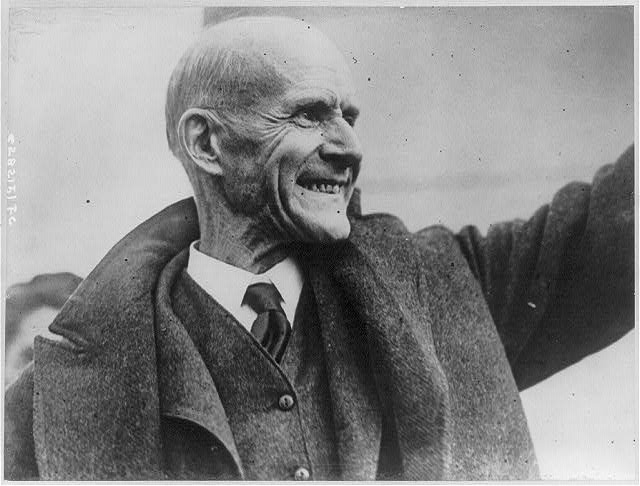

Eugene Victor Debs (1855-1926) was a trade unionist, an Indiana State Senator, and a Socialist Party candidate for president five times (the final time, in 1920, from prison). According to Debs, socialists advocated “the overthrow of the capitalist system and the emancipation of the working class from wage slavery.” Under their imagined socialist cooperative commonwealth, the means of production would be owned collectively, ensuring that all men and women received fair wages for their labor and a share of profits. According to socialist organizer and newspaper editor Oscar Ameringer, socialists wanted “ownership of the trust by the government, and the ownership of the government by the people.” Public Ownership Leagues attracted members from all walks of life, who wanted to shift control of services like city gasworks, streetcars, and later electrical production to the public. Other activists looked at European nations like Switzerland, which had nationalized its rail system in 1901, and wondered why American railroads, built with so much federal assistance, should remain in private hands. The idea that municipal services should be owned by local governments and natural monopolies such as railroads should be nationalized gained wide support.

The socialist movement drew from a diverse constituency that included reformers as well as revolutionaries. Party membership was open to all regardless of race, gender, class, ethnicity, or religion. Many prominent Americans, such as Helen Keller, Upton Sinclair, Jane Addams, and Jack London, became socialists. They were joined by masses of American laborers from across the United States. Factory workers, miners, railroad builders, tenant farmers, and small farmers all united under the red flag of socialism. Many supported Debs, Lucy Parsons (the widow of Albert Parsons, who had been executed for the Haymarket bombing), Socialist Labor Party leader Daniel DeLeon, and mining union leader William D. “Big Bill” Haywood in 1905 to form the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The “Wobblies”, as they were known, became a radical and confrontational union that welcomed all workers, regardless of race or gender.

Others turned to politics. The Socialist Party of America (SPA), founded in 1901, carried on the American third-party political tradition. Socialist mayors were elected in thirty-three cities and towns, from Berkeley, California, to Schenectady, New York, and two socialists from Wisconsin and New York won congressional seats. All told, over one thousand socialist candidates won American political offices. Julius A. Wayland, editor of the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason, proclaimed that “socialism is coming. It’s coming like a prairie fire and nothing can stop it. You can feel it in the air.” By 1913 there were 150,000 members of the Socialist Party and, in his fourth run for president in 1912, Eugene V. Debs received almost one million votes, or 6 percent of the total.

Like many activists including Helen Keller, Robert LaFollette, and Jane Addams, Debs spoke out loudly against America’s entry into World War I. President Woodrow Wilson declared Debs a “traitor to his country” and after a speech in Canton Ohio in which he urged young men to resist the draft, Debs was arrested on ten counts of sedition and sentenced to ten years in prison. At his sentencing, Debs said, “Your Honor, years ago I recognized my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.” Debs ran for president again while in prison and again received nearly a million votes. At the end of 1921, the new president, Warren G. Harding, commuted Debs’ sentence to time served. We will return to resistance to World War I in a later chapter.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did William Jennings Bryan become such a powerful force in the Democratic Party?

- How did Republicans such as McKinley defeat advocates of public ownership?

- Why was Eugene V. Debs never elected president?

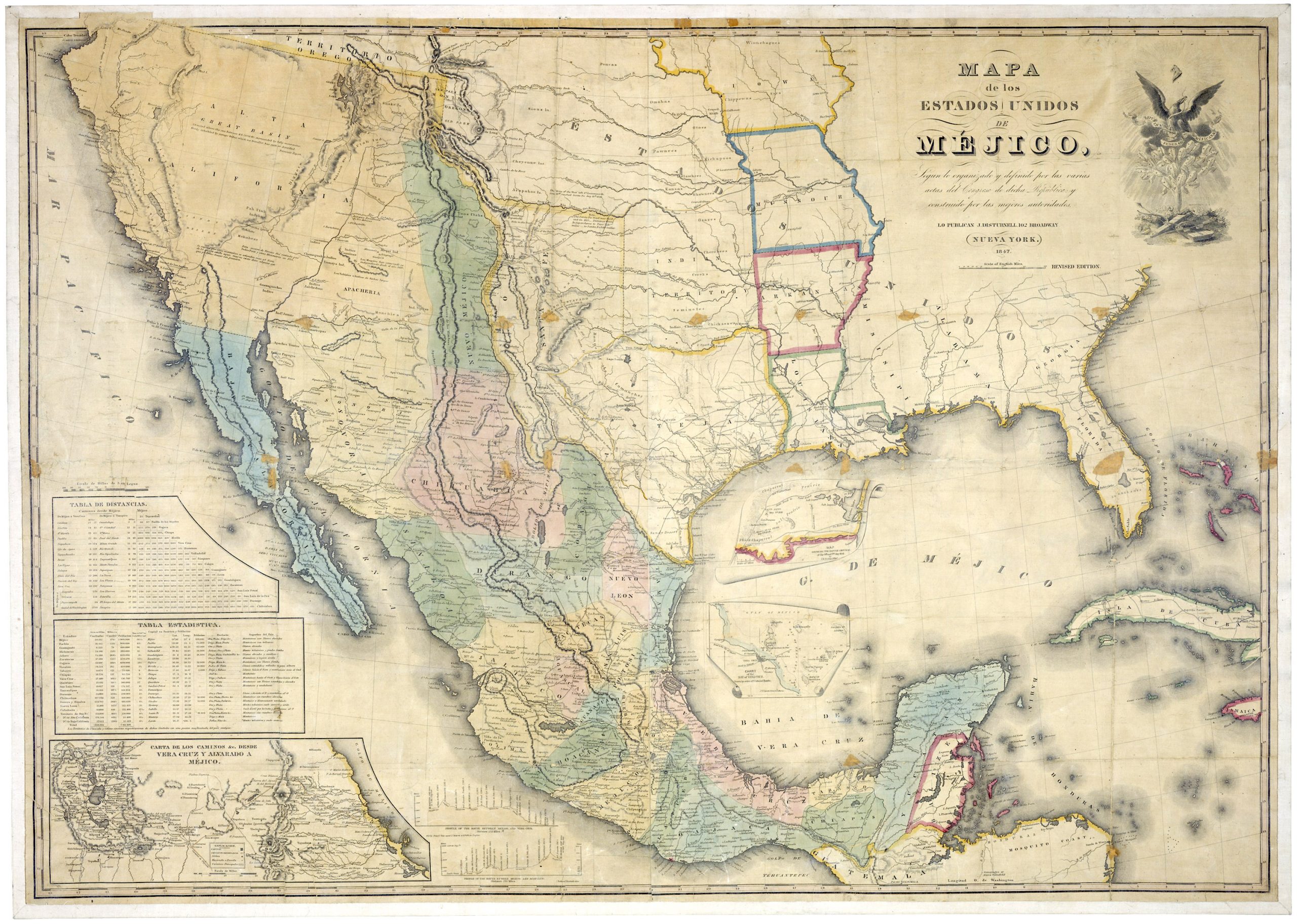

Western Expansion

The nineteenth century saw the expansion of the United States across the North American continent. Westward expansion had begun even before the Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War in 1783, in which Britain ceded the territory between the coastal colonies and the Mississippi River. These regions became the Northwest Territory; settlers arrived rapidly and the States of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois were admitted in 1803, 1816, and 1818. In 1803 Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase added another 828,000 square miles to the United States, doubled the size of the new nation. And in 1848 the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War with the U.S. acquisition of the half of Mexico between the Louisiana Territory and the Pacific, including what is now California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and part of Colorado and Wyoming. American expansion across the continent was considered the nation’s “Manifest Destiny” and relatively little thought was given to the native or Mexican people standing in the way of progress.

Native Americans had lived in the American West for between ten and fifteen thousand years. Linked culturally and geographically by trade, travel, and warfare, indigenous groups controlled most of the continent west of the Mississippi River well into the nineteenth century, despite the maps and treaties between nations designating these lands as U.S. territory. Spanish, French, British, and American traders and a few settlers had integrated themselves into many regional economies, but no imperial power had really achieved political or military control over most of the continent. But after the Civil War a West freed from fighting over slavery was quickly connected by railroads to a rapidly-industrializing east as population pushed farther west. The United States removed Native groups to ever-shrinking reservations, incorporated the West first as territories and then as states, and before the end of the century, controlled the entire land between the two oceans.

In the decades after the Civil War, Americans poured across the Mississippi River in record numbers. The first westward rushes had followed discoveries of gold in California in 1849 and in Colorado in 1859, and silver in Nevada, also in 1859. Adventurous American men (and a few women) had rushed to stake claims, although many more ended up working for wages than striking it rich. Some mined the claims that wealthy speculators like George Hearst acquired in boomtowns such as Virginia City, Nevada and Lead, South Dakota. Others worked in shops and saloons serving the boomtown residents. Some women went West with husbands and families; others worked in businesses including brothels catering to the large population of single miners. These service industries profited from the mining boom: as failed prospectors found, the rush itself often generated more wealth than the mines. The $25.5 million in gold that left Colorado in the first seven years after the Pikes Peak gold strike, for example, was less than half of what speculators had invested in the fever. Although that investment didn’t make most of the speculators rich, it did build a local economy. 100,000-plus migrants who settled in the Rocky Mountains were ultimately more valuable to the region’s development than the gold they came to find.

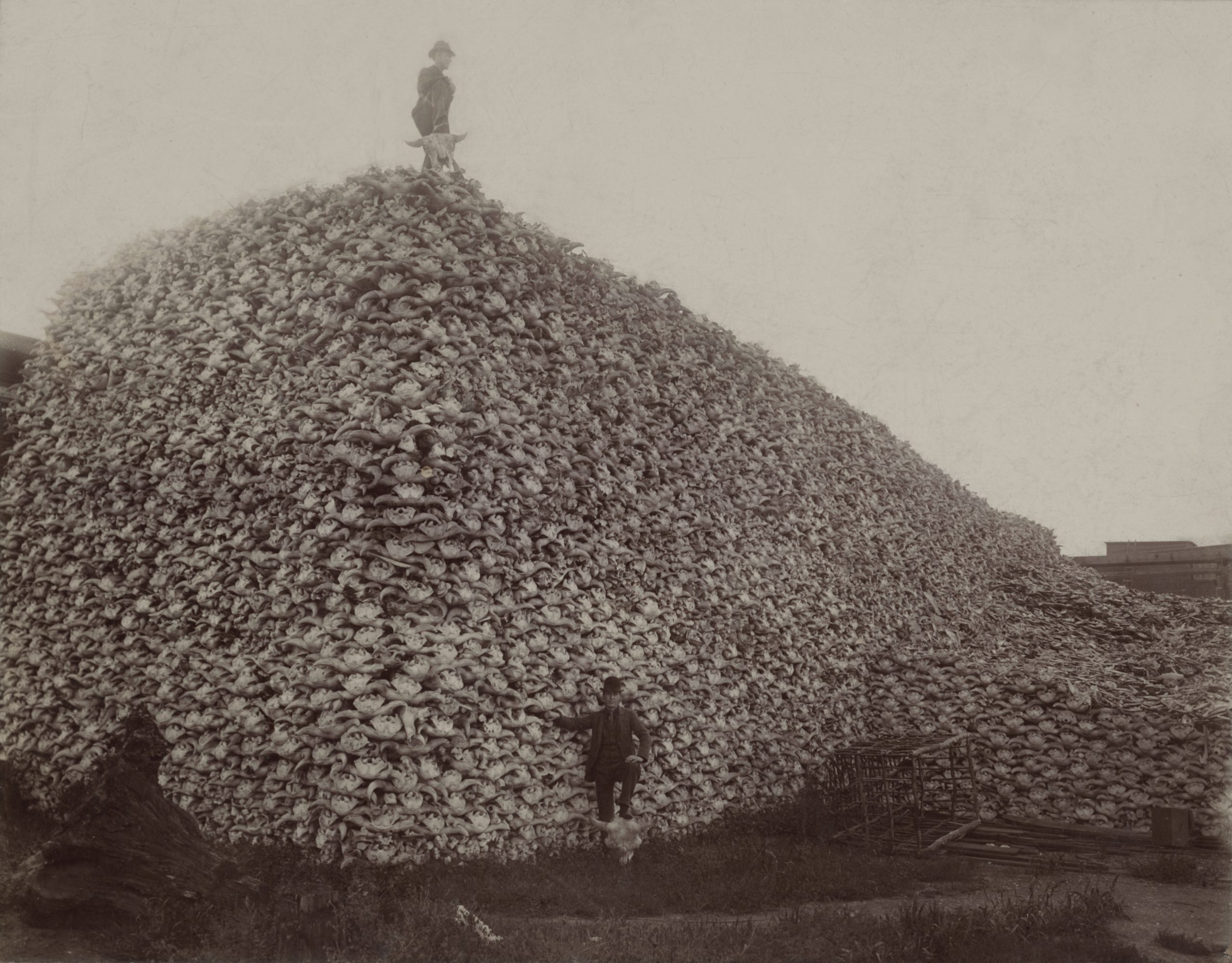

Other settlers came to the Great Plains to to farm or to ranch. Many began by collecting the hides of the great bison herds. Huge herds numbering millions of animals roamed the Plains, hunted for millennia by native people for food and their hides. American industry used the tough leather for industrial belting in eastern factories and as raw material for clothing and shoes. Specialized teams of buffalo hunters flocked to the West to shoot and skin the herds. Using new rifles, the hunters worked quickly, often taking hides and leaving carcasses to rot where they were shot. The infamous hunt peaked in the early 1870s, with the number of American bison plummeting from over ten million at midcentury to only a few hundred animals left alive by the early 1880s. The eradication of bison and expansion of the railroads allowed ranchers to replace the bison with cattle on the American grasslands.

Some settlers went west for religious freedom. Nearly seventy thousand members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (commonly called Mormons) migrated west between 1846 and 1868, fleeing from what they perceived as religious persecution. Many historians view Mormonism as a “uniquely American faith,” not just because it was founded by Joseph Smith in New York in the 1830s, but because of its optimistic and future-oriented tenets. Mormons incorporated into their faith the belief that Americans were exceptional—chosen by God to spread truth across the world and to build a New Jerusalem in North America. However, many Americans were suspicious of the Latter-Day Saint movement and its unusual rituals, especially the practice of polygamy, and most Mormons found it difficult to practice their faith in the eastern United States.

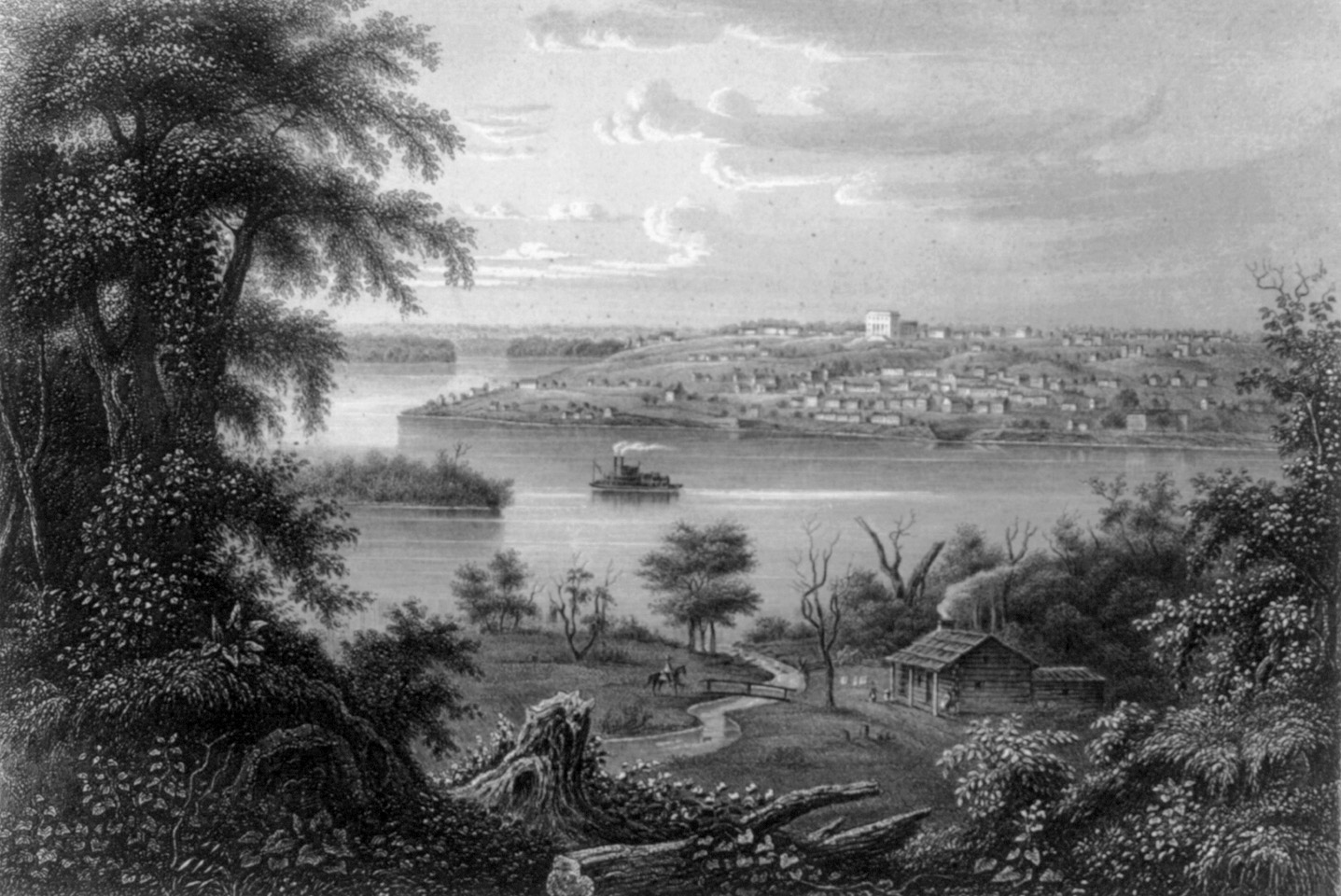

In 1844 Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were killed by a mob in Carthage Illinois while awaiting trial on charges stemming from a conflict with former Mormons in the town of Nauvoo, which Smith controlled. At the time, Smith was a candidate for the US presidency, running on a ticket that included protections for Latter-Day Saints and other minorities. A succession crisis followed Smith’s unexpected killing, which split church membership between three prominent leaders. Two formed new rival churches; Brigham Young led the remaining Mormons to the Utah Territory. Young was appointed governor of the Utah Territory by the federal government in 1850. He encouraged Mormon residents of the territory to farm or raise cattle, and urged them to be cautious of the outsiders who arrived as the mining and railroad industries developed in the region. Mormon settlements in Utah served as important supply points for other emigrants heading on to California and Oregon.

It was free land, ultimately, that drew the most migrants to the West. Family farms were the backbone of the agricultural economy that expanded into the West after the Civil War. In 1862, along with the Pacific Railroad Act that authorized transcontinental railways, Congress passed a Homestead Act which allowed male citizens (or those who declared their intent to become citizens) to claim federally owned lands in the West. Settlers could choose a 160-acre surveyed section of land, file a claim, and begin “improving” the land by plowing fields, building houses and barns, or digging wells. After five years of living on the land and working it, homesteaders could apply for the official title deed to the land. 1.6 million Americans used the Homestead Act between 1862 and 1934 to acquire about 250,000 square miles of land. Treeless plains that had once been considered unfit for settlement became a new agricultural heartland for land-hungry Americans.

The Homestead Act excluded married women from filing claims because they were considered to be legal dependents of their husbands. Some unmarried women filed claims on their own, but single farmers (male or female) found it nearly impossible to run a farm by themselves and thus were a small minority. Most farm households adopted traditional divisions of labor: men and their sons worked in the fields and women and their daughters managed the home and kept the family fed. The work of all family members was essential. Immigrants sometimes found in homesteading a chance for self-sufficiency unavailable in their native lands. Second or third sons who did not inherit land in both the Eastern States and in Scandinavia, for instance, founded farm communities in Minnesota, Dakota, and other Midwestern territories in the 1860s. Boosters advertising in Scandinavia encouraged emigration by advertising the semiarid Plains as “a flowery meadow of great fertility clothed in nutritious grasses, and watered by numerous streams.” Western populations exploded. In 1860, for example, Kansas had about 10,000 farms; by 1880 it had 239,000. Texas also saw enormous population growth. The federal census counted 200,000 people in Texas in 1850, 1,600,000 in 1880, and 3,000,000 in 1900, making it the sixth most populous state in the nation.

Questions for Discussion

- Why is it significant that expansion westward had been a part of American history since its start?

- What was the typical experience of someone who traveled west to participate in a gold or silver rush?

- What were the most significant effects of the elimination of bison herds from the plains?

- How did the Homestead Act affect the west?

Indian Wars

The “Indian wars,” mythologized in western folklore, were a series of sporadic engagements between U.S. military forces and various Native American groups. The more sustained and more impactful conflict, meanwhile, was economic and cultural. Native people’s traditional, cyclical movements across the Great Plains to hunt buffalo, raid enemies, and trade goods was incompatible with new patterns of American settlement and railroad construction. By the end of the nineteenth century, Thomas Jefferson’s hope that Indian groups might live isolated in the West was, in the face of white American expansion, no longer a viable reality. Although Indian removal had long been a part of federal Indian policy, following the Civil War the U.S. government redoubled its efforts to isolate Indians on reservations. If treaties and other forms of persistent coercion would not work, more drastic measures were taken. Against the threat of confinement and the extinction of traditional ways of life, Native Americans battled the American army and occasionally attacked encroaching American settlement.

One of the earliest western Indian wars, in 1862, began while the Civil War still consumed the nation. Throughout the 1850s, the Dakota of the Minnesota River Valley had grown increasingly frustrated by broken treaty promises and missed annuity payments by the U.S. government. The 1850 U.S. census had recorded only about 6,000 settlers in Minnesota; eight years later when it became a state, the white population was more than 150,000. The new American farmers cut the pine forests and plowed the prairies to plant corn and wheat. Hunting became unsustainable and Dakota who took up farming found only poverty. In August, 1862, four young men of the Santee tribe killed five white settlers near the Redwood Agency, an American administrative office. Facing an inevitable American retaliation, and over the protests of many members, the tribe chose a war to try to drive the settlers out of the region once and for all. Dakota warriors attacked settlements near the Agency, killing thirty-one men, women, and children. They then ambushed a U.S. Army detachment at Redwood Ferry, killing twenty-three. The governor of Minnesota called up militia and several thousand Americans waged war against the people they called Sioux. After battles at New Ulm, Fort Ridgely, and Birch Coulee, the Americans broke the Indian resistance at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, ending the brief war also known as the Sioux Uprising.

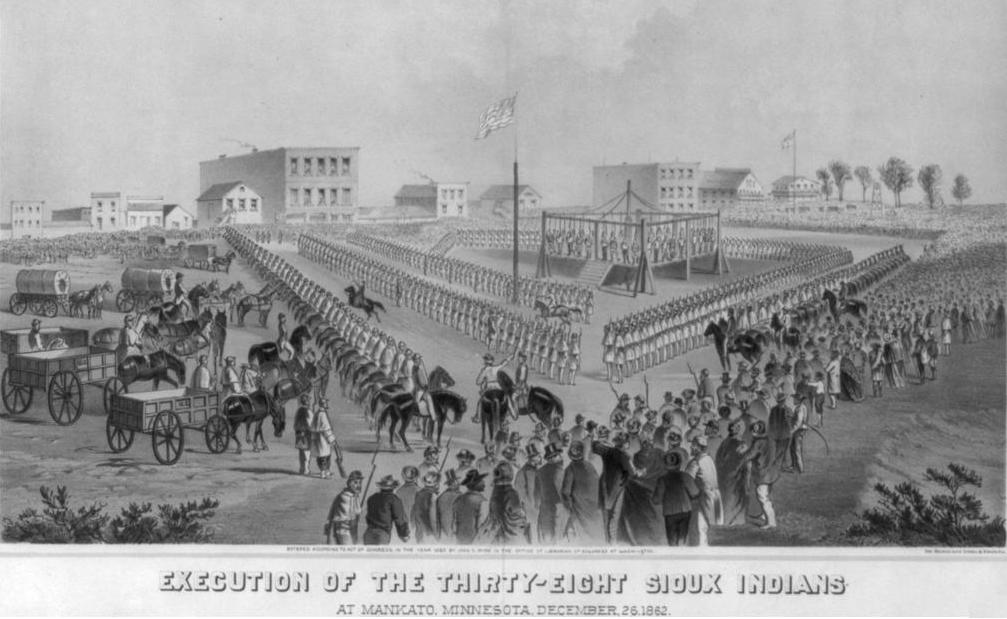

More than two thousand Dakota people had been captured during the fighting. Many of the men were tried at federal forts for murder, rape, and atrocities against white civilians that were sensationalized in newspaper accounts. For the first time, a military commission was formed to try the defeated Indians. 392 Dakota men were rapidly prosecuted and 303 convicted and sentenced to hang. President Lincoln commuted all but thirty-eight of the sentences. The Indians were executed in Mankato on December 26, 1862 in the largest mass execution in American history. Minnesota settlers and state government officials insisted not only that the Dakota must lose their reservation lands and be removed farther west, but that those who had fled should be hunted down and placed on reservations as well. The Army gave chase and, on September 3, 1863, after a year of attrition, they surrounded a large encampment of refugees who had fled into the Dakota territory near what is now Bismarck, North Dakota. American troops killed about three hundred men, women, and children. Dozens more were taken prisoner. The Army spent the next two days burning 300 tipis and 500,000 pounds of dried buffalo meat that had been stored as winter food, in an effort to starve out native resistance, which would continue to smolder. Sixteen hundred women, children, and old men were held in an internment camp at Fort Snelling, where over three hundred died of hunger and disease. The Dakota people were declared outlaws in Minnesota and a $25 bounty was offered per scalp collected.

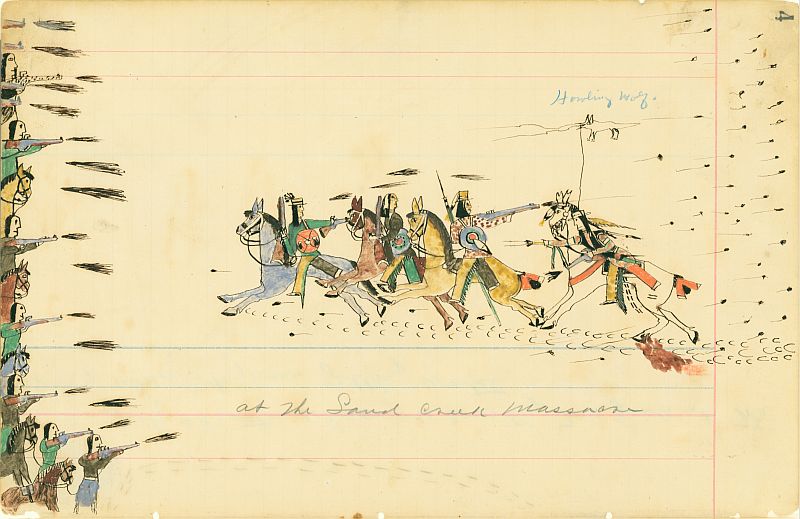

Farther south, tensions flared in Colorado. In 1851, the Treaty of Fort Laramie had secured passage across Indian territory for Americans passing through on their way to California and Oregon. But a gold rush in 1859 drew approximately 100,000 white gold-seekers who demanded new treaties to secure land rights in the Colorado Territory. Cheyenne bands splintered over whether to resist a new treaty that would confine them to a reservation. Settlers who already feared raids by Cheyennes, Arapahos, and Comanches read sensational accounts in their local newspapers of the Dakota uprising in Minnesota. Militia leader John M. Chivington warned settlers in the summer of 1864 that the Cheyenne were dangerous savages, urged war, and promised a swift military victory. Chivington, a former Methodist pastor, had commanded troops during the Civil War. Despite the fact that the aged Cheyenne chief Black Kettle, believing that a treaty would be best for his people, traveled to Denver to attend peace talks, Chivington insisted, “I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians. Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians!” When Black Kettle and his followers neared Sand Creek on their way to Fort Lyon, following government instructions in November 1864, Chivington’s 700 militiamen cut them down. It was a slaughter. About two hundred Indian men, women, and children were killed.

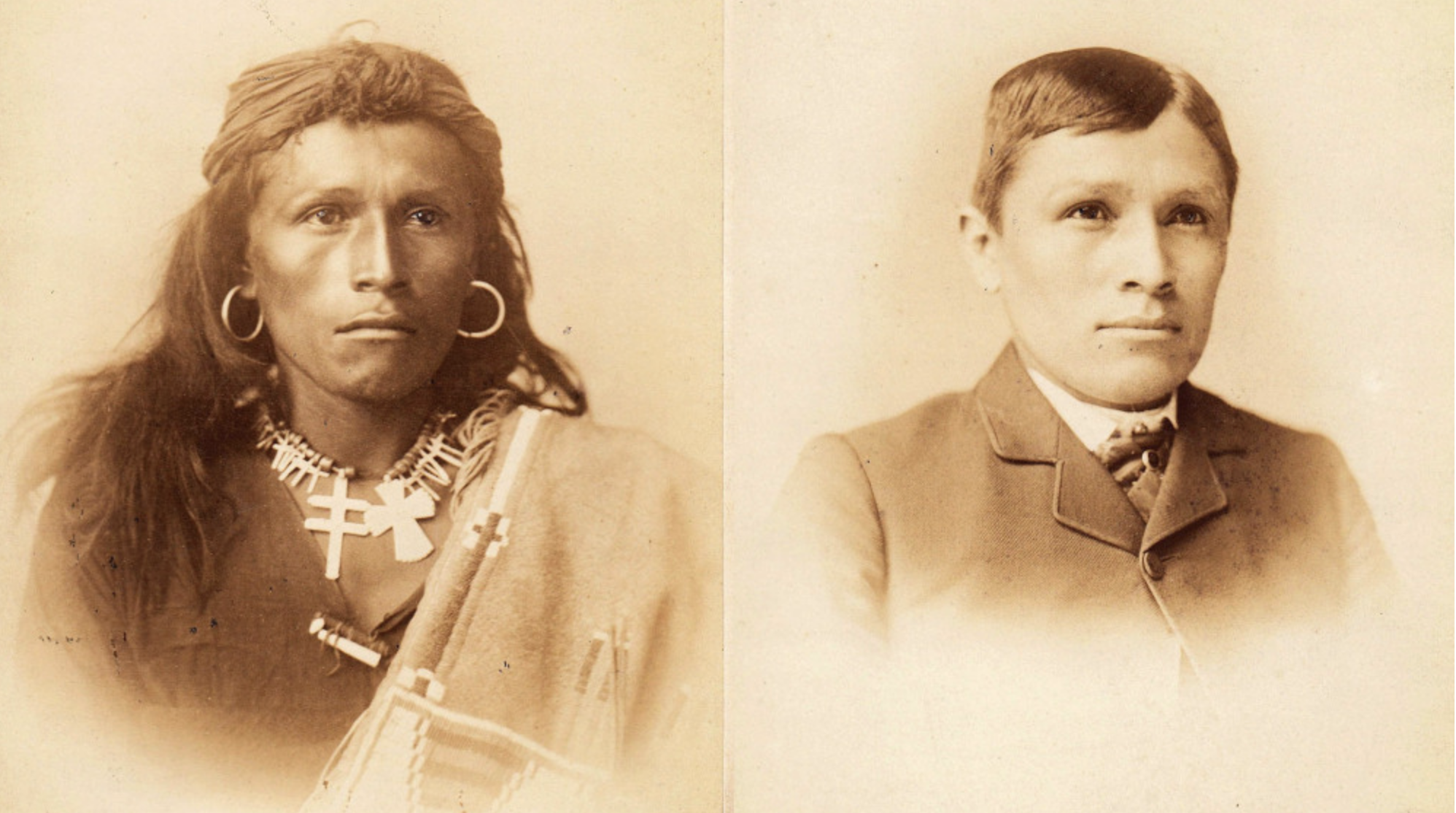

The Sand Creek Massacre was a national scandal and a joint committee of Congress determined that Chivington had “surprised and murdered, in cold blood, the unsuspecting men, women, and children on Sand Creek.” Many Americans pushed for a new peace policy and in 1868 Congress authorized an Indian Peace Commission and allied with prominent philanthropists to create the Board of Indian Commissioners. Much of the reservation system was handed over to Protestant churches, which were asked to find agents and missionaries to manage reservation life. In 1879, Captain Richard Henry Pratt founded what became known as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Inspired by the success of some Indian students at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural School, which had been established in 1868 by the American Missionary Association to teach freedmen in Virginia, Pratt believed along with many white Americans that rapid assimilation into Euro-American culture was the Indians’ best hope of survival. Pratt’s motto was, “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Carlisle became the model for boarding schools in fifteen states and territories.

Missionary women played a central role in cultural reeducation programs that tried to not only instill Protestant religion but also to impose traditional American gender roles and family structures. Their goal was to replace Indians’ communal social structures with small, patriarchal households. Women’s labor became a contentious issue because few tribes divided work according to the gender norms of middle- and upper-class Americans. Fieldwork traditional for white males was primarily done by Native women who controlled the products of their labor and the land that was worked. This gave the women status in society as food providers. Missionaries urged Native women to leave the fields and engage in more proper “women’s work”. American agents supervising reservations considered Indians lazy and thought Native cultures were inferior to their own. The views of J. L. Broaddus, appointed to oversee tribes on the Hoopa Valley reservation in California, are typical: “The great majority of them are idle, listless, careless, and improvident. They seem to take no thought about provision for the future, and many of them would not work at all if they were not compelled to do so. They would rather live upon the roots and acorns gathered by their women than to work for flour and beef.”

If the Indians could not be convinced through kindness to change their ways, most Americans agreed it was acceptable to use force. Native groups resisted. The Comanche in particular inspired terror from the Rocky Mountains to the Texas Gulf Coast. But after the Civil War, the U.S. military focused its attention on the remaining pockets of armed resistance. Confronted with renewed Comanche raiding, particularly by the famed war leader Quanah Parker, the Army finally proclaimed that all Indians who were not settled on the reservation by the fall of 1874 would be considered “hostile.” The Red River War began when Comanche bands refused to resettle and American troops launched expeditions into the Southern Plains to subdue them, ending in the defeat of the roaming bands in the canyonlands of the Texas Panhandle. Cold and hungry, with their way of life already decimated by soldiers, settlers, cattlemen, and railroads, the last free Comanche bands moved to the reservation at Fort Sill, in what is now southwestern Oklahoma.

On the northern Plains, the so-called Sioux people had yet to fully surrender. Following Red Cloud’s War, a rare victory for the Plains people, the U.S. government signed the second Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 and created the Great Sioux Reservation. In 1874, an American expedition led by George Armstrong Custer to protect Northern Pacific Railway survey crews discovered gold in the Black Hills. White prospectors flooded the area around Deadwood gulch, deep in the western region of the Reservation. Aware that U.S. citizens were violating treaty provisions but unwilling to prevent them from searching for gold, federal officials pressured the western tribes to sign a new treaty transferring control of the Black Hills to the United States while General Philip Sheridan quietly moved troops into the region. Initial clashes between the Army and Lakota warriors resulted in several Indian victories that, combined with the visions of Sitting Bull, attracted several bands who had already signed treaties but now joined to fight.

In late June 1876, a division of the 7th Cavalry Regiment led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer was sent up a trail into the Black Hills as an advance guard for a larger force. The 7th Cavalry, formed just after the Civil War, had previously fought Black Kettle’s Cheyenne in an engagement the government’s Indian Bureau had labeled a “massacre of innocent Indians.” Custer’s men attacked a camp along a river known to the Indians as Greasy Grass but marked on Custer’s map as Little Bighorn, and they found the population of the village far exceeded Custer’s estimates. Custer’s 7th Cavalry was vastly outnumbered; he and 268 of his men were killed. Custer’s fall shocked the nation and military expeditions were sent out to crush Native resistance. Sitting Bull escaped to Canada and the Lakota bands splintered off into the wilderness to begin a campaign of intermittent resistance. Heavily outnumbered and suffering after a long, hungry winter, Crazy Horse led a band of Oglala to surrender in May 1877. He was killed in custody a few months later. Other bands gradually followed until finally, in July 1881, Sitting Bull and his followers returned to their homeland from Canada, laid down their weapons and came to the reservation. Sitting Bull was killed in 1890 by authorities who feared he had returned to Standing Rock to lead the Ghost Dance movement. Indigenous powers had been defeated. The Plains, it seemed, had been pacified.

Questions for Discussion

- What were the general causes of the 1862 Dakota war against Minnesota settlers?

- Why were Indians the victims of so many massacres during the nineteenth century?

- Was the attempt to re-educate natives to assimilate to Euro-American culture successful?

- Why are characters like George Armstrong Custer generally considered as heroes in the American West?

Beyond the Plains

Plains peoples were not the only ones who suffered as a result of American expansion. Groups like the Utes and Paiutes were pushed out of the Rocky Mountains by U.S. expansion into Colorado and away from the northern Great Basin by the expanding Mormon population in Utah Territory in the 1850s and 1860s. Destruction of Indian nations in California and the Pacific Northwest received significantly less attention (at the time and from historians) than the dramatic conquest of the Plains, but Natives in these regions also experienced violence, population decline, and territory loss. Over one hundred distinct Native groups had lived in California before the Spanish and American conquests, but by 1880 the Native population of California had collapsed from about 150,000 on the eve of the gold rush to fewer than 20,000.

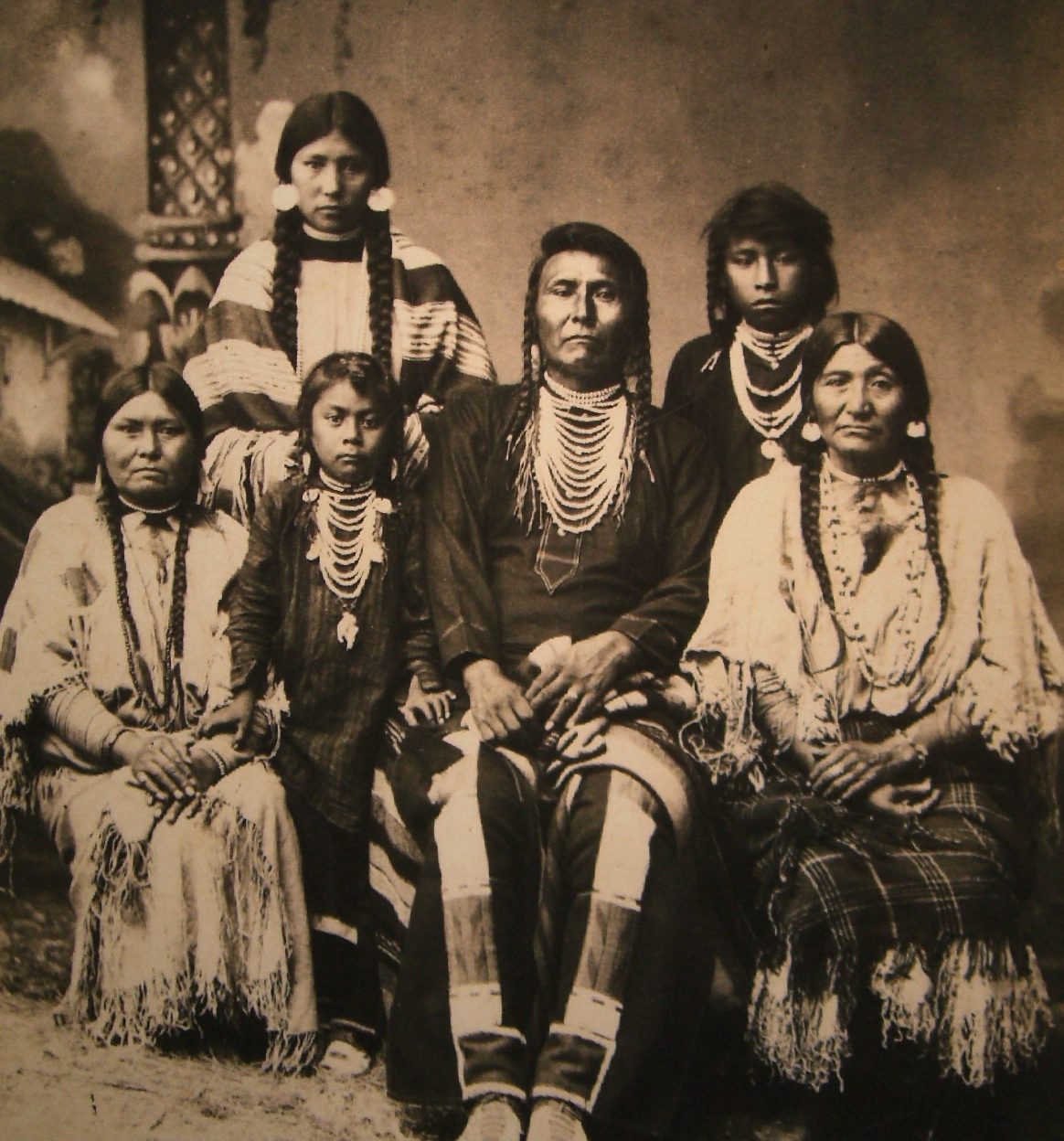

In 1872, the California-Oregon border erupted in violence when the Modoc people left the reservation of their historic enemies, the Klamath tribe, and returned to an area known as Lost River. White Americans had settled the region after Modoc removal and they complained bitterly of the Natives’ return. The U.S. Army got involved when fifty-two Modoc warriors led by a man called Captain Jack refused to return to the reservation and fought a guerrilla war for eleven months in which at least two hundred U.S. troops were killed. Four years later, in the Pacific Northwest, a branch of the Nez Percé tribe (who, generations earlier, had aided Lewis and Clark in their famous journey to the Pacific Ocean) refused to be moved to a reservation and, under the leadership of Chief Joseph, attempted to flee to Canada. Pursued by the U.S. Cavalry, the outnumbered Nez Percé battled across a thousand miles and were attacked nearly two dozen times before they gave in to hunger and exhaustion, surrendered, and were forced to return. The transcript of Chief Joseph’s surrender, recorded by an Army officer, became a landmark of American rhetoric. “Hear me, my chiefs,” Joseph said, “I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

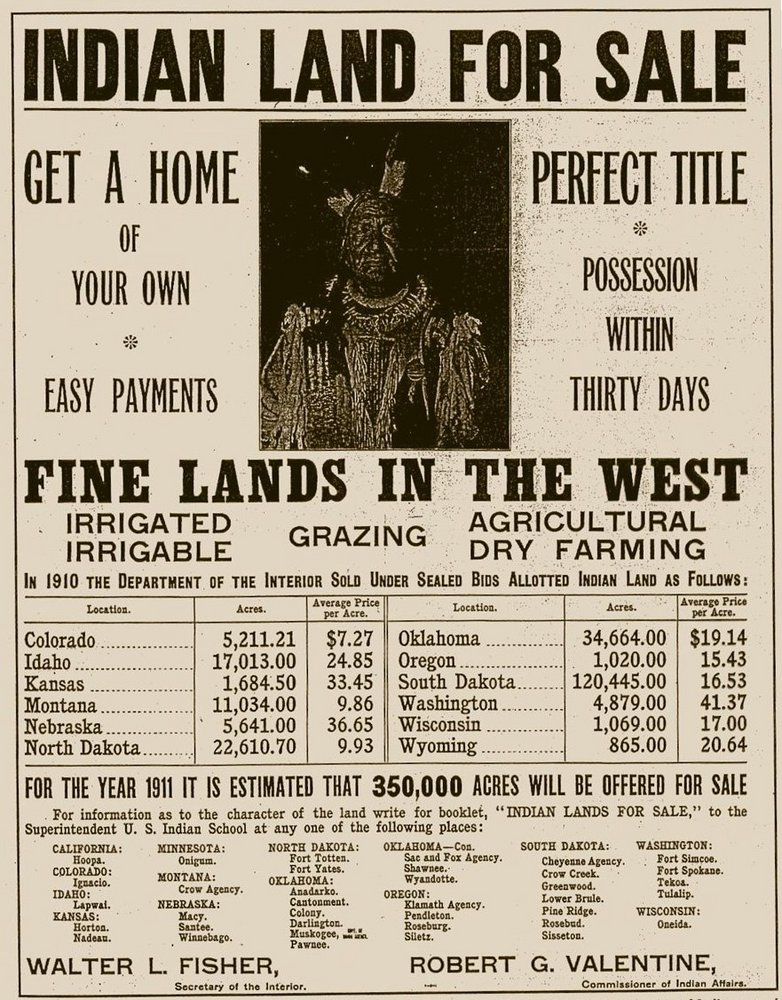

As settlers moved into the West, the situation for Natives deteriorated even further. Treaties negotiated between the United States and Native groups had typically promised that if tribes agreed to move to reservation lands, they could hold those lands collectively. But as American westward migration mounted and open lands closed, white settlers began to argue that Indians had more than their fair share of land, that the reservations were too big, that Indians were using the land “inefficiently,” and that they still preferred nomadic hunting instead of intensive farming and ranching. By the 1880s, many Americans championed legislation to allow the transfer of Indian lands to farmers and ranchers. They argued that allotting Indian lands to individual Native Americans, rather than to tribes, would encourage American-style land ownership and finally put Indians who had previously resisted the efforts of missionaries and federal officials on the path to “civilization.” Often, this argument masked the hope that individual Indians could be convinced or threatened into selling their parcels where tribal communities could not.

The Dawes General Allotment Act, passed by Congress in February 1887, splintered Native reservations into individual family homesteads. Each head of an Indian household was allotted 160 acres, the size of a claim that any settler could make on federal lands under the provisions of the Homestead Act. Single people over age eighteen would receive an eighty-acre allotment and orphaned children got forty acres. A four-year time limit was set for Indians to make their allotment selections. If no selection had been made in four years, the Secretary of the Interior would appoint an agent to make selections for the remaining tribe members. To protect Indians from being swindled by unscrupulous land speculators, the Act stated that all allotments would be held in trust and could not be sold by the allottees for twenty-five years. But lands that remained unclaimed by tribal members after allotment would revert to federal control and could be sold to American settlers.

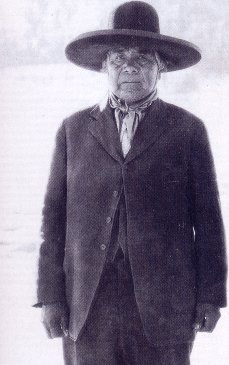

Conquest throughout the nineteenth century had displaced generations of Native Americans. Many took comfort from the words of Indian prophets and holy men. In Nevada at the beginning of 1889, Northern Paiute prophet Wovoka told his people he had experienced a great revelation. He said, “You must not hurt anybody or do harm to anyone. You must not fight. Do right always.” And they must, he said, participate in a religious ceremony that came to be known as the Ghost Dance. If the people lived justly and danced the Ghost Dance, Wovoka prophesied that their ancestors would rise from the dead, droughts would cease, the whites in the West would vanish, and the buffalo would once again cover the Plains.

Wovoka’s prophecy spread quickly. From across the West, members of the Arapaho, Bannock, Cheyenne, and Shoshone nations adopted the Ghost Dance. Perhaps the most avid Ghost Dancers were the Lakota. South Dakota, formed out of land that had once belonged to the Lakotas and had later been part of the Great Sioux Reservation, became a state in 1889. White homesteaders had poured in, reservation lands diminished, starvation set in, corrupt federal agents cut food rations, and drought hit the Plains. Many Lakota feared a future as the landless subjects of a growing American empire when a delegation of eleven men returned from a visit west to spread the revival in the Dakotas.

The message and the energy of the revival movement frightened U.S. Indian agents, who began arresting Indian leaders. Chief Sitting Bull’s assassination in December 1890 convinced many bands to flee the reservations to join fugitives farther west, where Lakota adherents of the Ghost Dance began claiming Dancers would be immune to bullets. Two weeks after Sitting Bull’s killing, a reconstituted 7th Cavalry intercepted a fleeing band of 350 Lakotas, including over 100 women and children. The fugitives were escorted to Wounded Knee Creek, where they camped for the night. The following morning, December 29, troops entered the camp to disarm the Indians. Tensions flared, a shot was fired, and a massacre ensued. The 7th Cavalry fired heavy weaponry including Hotchkiss light cannons indiscriminately into the camp. Two dozen cavalrymen were killed, either by concealed Lakota weapons or by friendly fire, but when the guns were finally silent, between 250 and 300 Native men, women, and children were dead.

Wounded Knee was the end of sustained, armed Native American resistance in the West. Individuals continued to the struggle against the pressures of assimilation and to preserve traditional cultural practices. But sustained military defeats, loss of sovereignty over land and resources, and the onset of crippling poverty, disease, and starvation on the reservations marked the final decades of the nineteenth century as a particularly dark era for America’s western tribes. But for white Americans, it became mythical.

Questions for Discussion

- Why was it important for the US to capture Chief Joseph as he was trying to lead his people to escape into Canada?

- What was the most important effect of the Dawes Act?

- Were white authorities right to be afraid of Ghost Dancers?

- Why has “Wounded Knee” become such a potent image of injustice to native peoples?

The “Wild West”

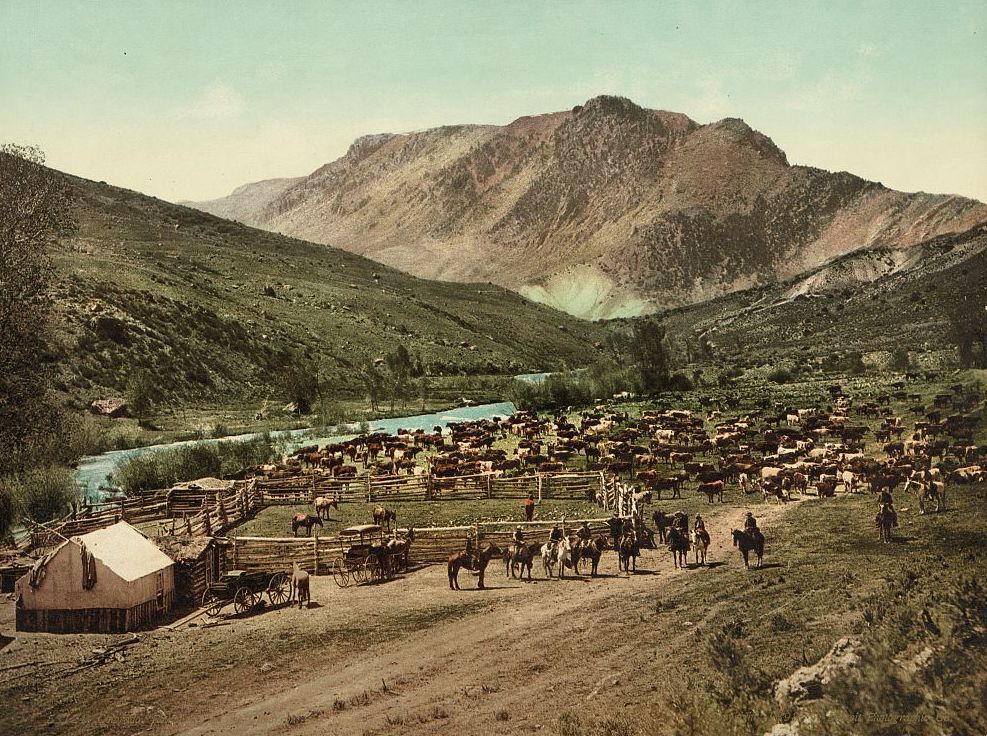

As Native Americans were pushed off the land, white settlers poured in. In addition to agriculture and extraction of natural resources like timber and precious metals, two major industries combined to prosper in the new western economy: ranching and railroads. The national rail network created in the 1860s produced the fabled cattle drives across the central Plains in the 1870s. Railroads allowed live cattle to be shipped to eastern cities, creating a market, and ranchers began driving cattle north to major rail-heads in Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska.

Cattle drives were difficult work for the crews who managed the herds. Historians estimate the number of men who worked as cowboys in the late-nineteenth century at up to forty thousand. Perhaps a fourth were African American, and more were likely Mexican or Mexican American. Many of the customs and techniques of American cowboys were borrowed from Mexican vaqueros. Cowboys adopted Mexican practices, gear, and Spanish terms such as rodeo, bronco, and lasso. While most cattle drivers were men, there are at least sixteen verified accounts of women participating in the drives. Some, like Molly Dyer Goodnight, accompanied their husbands. Others, like Lizzie Johnson Williams, helped drive their own herds. Williams (1840-1924), a business-woman, author, and teacher, was known as the Cattle Queen of Texas. She made at least three trips with her herds up the Chisholm Trail.

Like the prospectors who flocked to each new gold or silver rush, many cowboys hoped one day to become ranch owners themselves. But employment was insecure and wages were low. Beginners could expect to earn around $25 per month, and those with years of experience might earn $40. Trail bosses might earn $50 per month. But it was tough work. On a cattle drive, cowboys worked long hours and faced extremes of heat, cold, and intense blowing dust. They subsisted on limited diets with irregular supplies.

Despite a much more down-to-earth reality, the myth of “The American West” conjures visions of tipis, cabins, cowboys, Indians, farm wives in sunbonnets, and outlaws with six-shooters. These images that pervade American culture are actually as old as the West itself. As soon as settlers, prospectors, and cowboys began arriving on the scene, novels, rodeos, and Wild West shows sprang up to mythologize the American West throughout the post–Civil War era.

Americans devoured dime novels that embellished the stories of real-life individuals such as Calamity Jane and Billy the Kid. And Owen Wister’s fully fictional novels, especially The Virginian, established the character of the cowboy in popular culture as a gritty stoic with a rough exterior but possessing courage and skills needed to rescue less heroic people from train robbers, Indians, and cattle rustlers. Such images were reinforced when the rodeo added to popular conceptions of the American West as a place of action and conflict. Rodeos had begun as small roping and riding contests among cowboys in towns near ranches or celebrations in camps at the end of the cattle trails. Casual contests evolved into planned events, often scheduled around national holidays such as Independence Day. They gained popularity and soon dedicated rodeo circuits developed. Traveling shows toured the eastern United States and even crossed Europe from the 1880s to the 1910s. Former Army scout and bison hunter William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody was the first to recognize the broad national appeal of the stock characters of the American West—cowboys, Indians, sharpshooters, cavalrymen, and rangers—and put them all together into a massive traveling extravaganza. Cody called his production, launched in 1883, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.” He employed real cowboys and Indians such as “Wild Bill” Hickock and Sitting Bull in his productions. But it was still entertainment, little different in its broad outlines from contemporary theater. Storylines depicted westward migration, life on the Plains, and Indian attacks, all punctuated by “cowboy fun” like bucking broncos, roping cattle, and sharpshooting contests.

In an attempt to appeal to women, Cody recruited Annie Oakley, a female sharpshooter who thrilled onlookers by shooting apples off her poodle’s head and the ash from her husband’s cigar. May Manning Lillie, the wife of competing empresario Gordon Lillie, also became a skilled shot and performed as “World’s Greatest Lady Horseback Shot.” Female sharpshooters were Wild West show staples. As many as eighty toured the country at the shows’ peak. While such acts challenged expected Victorian gender roles, female performers carefully maintained their feminine identity by riding sidesaddle and wearing full skirts and corsets during their acts.

The western “cowboys and Indians” mystique was rooted in romantic nostalgia for a frontier era many saw as ending. In 1893, Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his “frontier thesis,” one of the most influential theories of American history, in a speech at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Turner looked back at the historical changes in the West and saw, instead of a tsunami of war and plunder and industry, waves of “civilization” washing across the continent. He described a frontier line “between savagery and civilization” that had moved unstoppably westward from the earliest English settlements across the Appalachians to the Mississippi and finally across the Plains to California and Oregon. Turner invited his audience to “stand at Cumberland Gap [a famous pass through the Appalachian Mountains into Kentucky], and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.”

The frontier stripped away the veneer of old European civilization, Turner said, forcing Americans to build a new civilization and to learn new rules. This new American character of freedom and self-reliance gave the United States its exceptional hustle and its democratic spirit and distinguished North America from the stale monarchies of Europe. But Turner worried about the future. The Census Bureau had declared the frontier closed in 1890. What would become of the nation without the safety valve of the frontier? It was a contagious sentiment. Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Turner that his essay “put into shape a good deal of thought that has been floating around rather loosely.” At the time Roosevelt was only a wealthy New York author interested in politics, but he shared Turner’s concern over the loss of the frontier. Roosevelt was also worried about the late nineteenth century’s new, “soft” industrial world of factory and office work. The mythical cowboy’s “aggressive masculinity” seemed to be the perfect antidote for middle- and upper-class, city-dwelling Americans who feared they “had become over-civilized” and longed for what Roosevelt called the “strenuous life.” The romance of the West would continue to pull at generations of Americans and would influence their ideas about the U.S. in world affairs.

Questions for Discussion

- How was the life of an actual cowboy similar to that of a “forty-niner” during the gold rush?

- Why were Wild West shows so popular?

- Why was Frederick Jackson Turner concerned that the frontier had been declared “closed”?

- What effect did frontier life have shaping Americans, in Turner’s opinion?

Primary Sources

Chief Joseph on Indian Affairs (1877, 1879)

A branch of the Nez Percé tribe, from the Pacific Northwest, refused to be moved to a reservation and attempted to flee to Canada but were pursued by the U.S. Cavalry, attacked, and forced to return. The following is a transcript of Chief Joseph’s surrender, as recorded by Lieutenant Wood, Twenty-first Infantry, acting aide-de-camp and acting adjutant-general to General Oliver O. Howard, in 1877.

Chester A. Arthur on American Indian Policy (1881)

The following is extracted from President Chester A. Arthur’s First Annual Message to Congress, delivered December 6, 1881.

Grover Cleveland’s Veto of the Texas Seed Bill (1887)

Amid a crushing drought that devastated many Texas farmers, Grover Cleveland vetoed a bill designed to help farmers recover by supplying them with seed. In his veto message, Cleveland explained his vision of the proper role of government.

William T. Hornady on the Extermination of the American Bison (1889)

William T. Hornady, Superintendent of the National Zoological Park, wrote a detailed account of the near-extinction of the American bison in the late-nineteenth century.

The “Omaha Platform” of the People’s Party (1892)

For the 1892 presidential election, the People’s Party crafted a platform that indicted the corruptions of the Gilded Age and promised government policies to aid “the people.” Nearly all of these Populist proposals were later enacted into law.

Frederick Jackson Turner, “Significance of the Frontier in American History” (1893)

Perhaps the most influential essay by an American historian, Frederick Jackson Turner’s address to the American Historical Association on “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” defined for many Americans the relationship between the frontier and American culture and contemplated what might follow “the closing of the frontier.”

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, “Lynch Law in America” (1900)

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, born a slave in Mississippi, was a pioneering activist and journalist. She did much to expose the epidemic of lynching in the United States and her writing and research exploded many of the justifications—particularly the rape of white women by black men—commonly offered to justify the practice.

William McKinley on American Expanionism (1903)

After the surrender of the Spanish in the Spanish-American War, the United States assumed control of the Philippines and struggled to contain an anti-American insurgency.

References:

This chapter was written by Dan Allosso, based on two chapters from The American Yawp. Those chapters were edited by Lauren Brand (Chapter 17) and Ellen Adams and Amy Kohout (Chapter 19), with content contributions by Lauren Brand, Carole Butcher, Josh Garrett-Davis, Tracey Hanshew, Nick Roland, David Schley, Emma Teitelman, Alyce Webb, Ellen Adams, Alvita Akiboh, Simon Balto, Jacob Betz, Tizoc Chavez, Morgan Deane, Dan Du, Hidetaka Hirota, Amy Kohout, Jose Juan Perez Melendez, Erik Moore, and Gregory Moore.

Recommended Reading on the West:

- Aarim, Najia. Chinese Immigrants, African Americans, and Racial Anxiety in the United States, 1848–1882. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

- Andrews, Thomas. Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

- Cahill, Cathleen. Federal Fathers and Mothers: A Social History of the United States Indian Service, 1869–1933. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

- Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: Norton, 1991.

- Gordan, Linda. The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Hämäläinen, Pekka. The Comanche Empire. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Hine, Robert V. The American West: A New Interpretive History. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Huhndorf, Shari M. Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001.

- Isenberg, Andrew C. The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750–1920. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Jacobs, Margaret D. White Mother to a Dark Race: Settler Colonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia, 1880–1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

- Johnson, Benjamin Heber. Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans into Americans. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Kelman, Ari. A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling over the Memory of Sand Creek. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Krech, Shepard. The Ecological Indian: Myth and History. New York: Norton, 1999.

- Limerick, Patricia Nelson. The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West. New York: Norton, 1987.

- Marks, Paula Mitchell. In a Barren Land: American Indian Dispossession and Survival. New York: Morrow, 1998.

- Montejano, David. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987.

- Pascoe, Peggy. Relations of Rescue: The Search for Female Moral Authority in the American West, 1874–1939. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Prucha, Francis Paul. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

- Schulten, Susan. The Geographical Imagination in America, 1880–1950. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Shah, Nayan. Stranger Intimacy: Contesting Race, Sexuality, and the Law in the North American West. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- Smith, Henry Nash. Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth. New York: Vintage Books, 1957.

- Taylor, Quintard. In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528–1990. New York: Norton, 1999.

- Warren, Louis S. Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show. New York: Knopf, 2005.

- White, Richard. “It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own”: A New History of the American West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

Recommended Reading on Empire:

- Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Brooks, Charlotte. Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Gabaccia, Donna. Foreign Relations: American Immigration in Global Perspective. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Greene, Julie. The Canal Builders: Making America’s Empire at the Panama Canal. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Guglielmo, Thomas A. White on Arrival: Italians, Race, Color, and Power in Chicago, 1890–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Harris, Susan K. God’s Arbiters: Americans and the Philippines, 1898–1902. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988.

- Hirota, Hidetaka. Expelling the Poor: Atlantic Seaboard States and the Nineteenth-Century Origins of American Immigration Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Hoganson, Kristin. Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

- Hoganson, Kristin L. Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign People at Home and Abroad, 1876–1917. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

- Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Kaplan, Amy. The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Kramer, Paul A. The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Lafeber, Walter. The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1963.

- Lears, T. J. Jackson. Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877–1920. New York: HarperCollins, 2009.

- Linn, Brian McAllister. The Philippine War, 1899–1902. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000.

- Love, Eric T. L. Race over Empire: Racism and U.S. Imperialism, 1865–1900. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

- Pascoe, Peggy. What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Perez, Louis A., Jr. The War of 1898: The United States and Cuba in History and Historiography. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Renda, Mary. Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of US Imperialism, 1915–40. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Rosenberg, Emily S. Spreading the American Dream: American Economic and Cultural Expansion, 1890–1945. New York: Hill and Wang, 1982.

- Silbey, David. A War of Frontier and Empire: The Philippine-American War, 1899–1902. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007.

- Wexler, Laura. Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of US Imperialism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- Williams, William Appleman. The Tragedy of American Diplomacy, 50th Anniversary Edition. New York: Norton, 2009 [1959].

Media Attributions

- 2880px-Emanuel_Leutze_-_Westward_the_Course_of_Empire_Takes_Its_Way_-_Smithsonian © Emanuel Leutze is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Greenback_factors © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The Farmers’ alliance history and agricultural digest © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1892PopulistPoster © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 00025u copy © American Oleographic Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- FSA/8a17000/8a170008a17065a.tif © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3f06259v © Geo. H. Van Norman is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3c18935v © C. M. Bell is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3b22777r © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Desturnell Mexico.tif © John Disturnell is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bison_skull_pile_edit © Chick Bowen is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Nauvoo3b24766u © Herrmann J. Meyer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hultstrand61 © A Milton is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1904paintingAttackNewUlmAntonGag © Anton Gag is licensed under a Public Domain license

- MankatoMN38 © W. H. Childs is licensed under a Public Domain license

- At_the_Sand_Creek_Massacre,_1874-1875 © Howling Wolf is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Screen Shot 2020-01-20 at 12.24.53 PM © American Yawp

- Red_Cloud_and_other_Sioux © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pawnee_bill_wild_west_show_c1905 © Siegel, Cooper & Co is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Chief_Joseph_and_family © F. M. Sargent is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Indian_Land_for_Sale © United States Department of the Interior is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Wovoka_Paiute_Shaman

- Woundedknee1891 © Northwestern Photo Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 17998v © Detroit Photographic Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 02638v © J.C.H. Grabill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Calamity_Jane_1890s © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- William_Notman_studios_-_Sitting_Bull_and_Buffalo_Bill_(1895)_edit © William Notman and Son is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Frederick_Jackson_Turner © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license