12 The New Right

-

Ronald Reagan

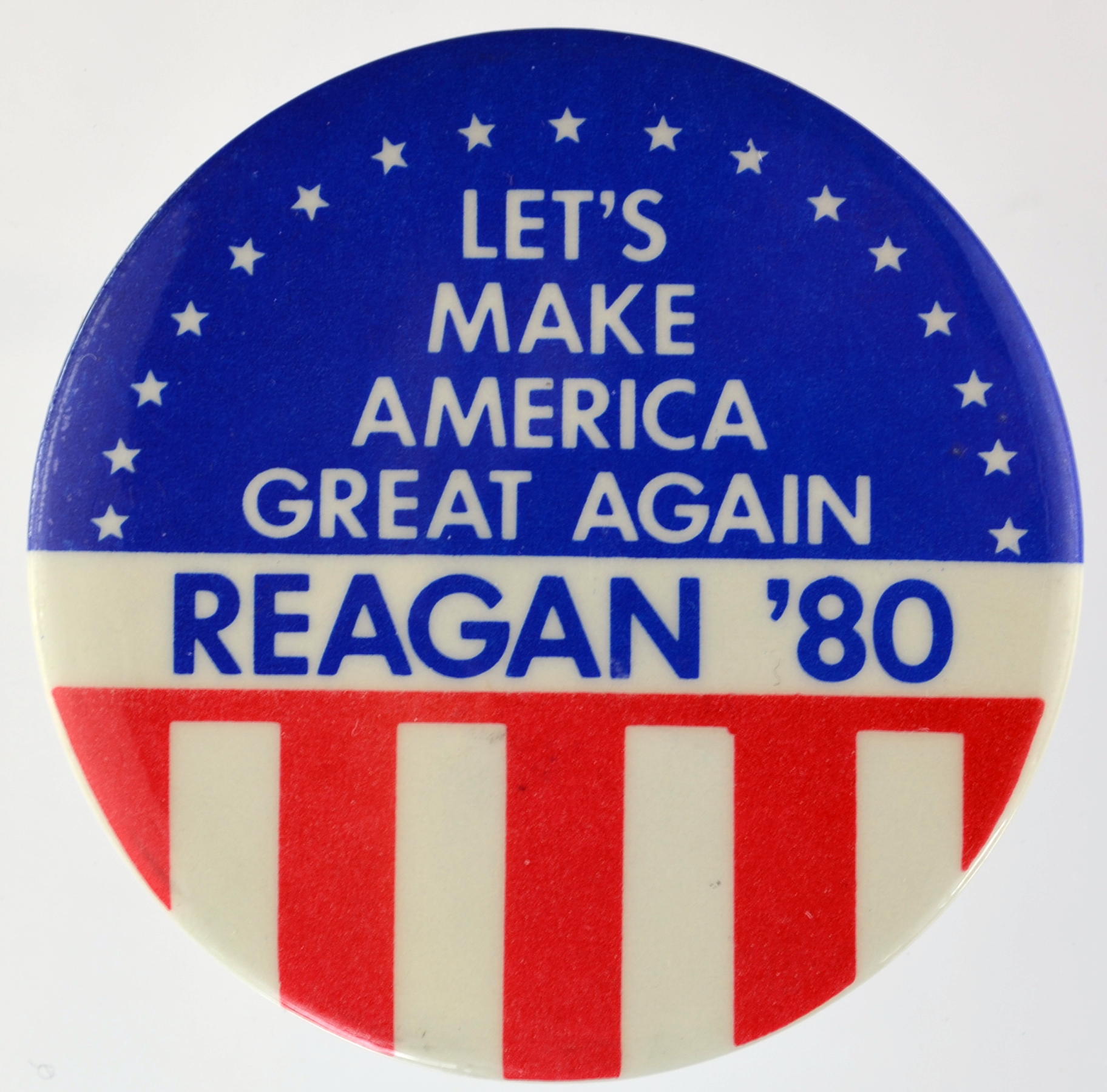

Speaking to Detroit autoworkers in October 1980, Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan described what he saw as the American Dream under Democratic president Jimmy Carter. The family garage may have still held two cars, cracked Reagan, but they were “both Japanese and they’re out of gas.” The charismatic former governor of California suggested that a once-proud nation was running on empty. But Reagan held out hope for redemption. Stressing the theme of “national decline,” he nevertheless promised to return the United States to its status as the admirable “city upon a hill” that he and many Americans believed it had once been. In November, Reagan’s vision was more attractive than Carter’s complaints of a national “malaise” and Reagan denied Carter a second term.

Ronald Reagan had been a B-list Hollywood actor before serving in a stateside public relations unit during World War II. Although originally a New Deal Democrat, Reagan became a Republican and cooperated with the HUAC investigations of the McCarthy era. He defeated two-term Democratic California governor Pat Brown in 1966 and served two terms himself; but he set his sights on the White House in 1968. In the primary, Reagan got more of the popular than Nixon but fewer delegates. He sat out the 1972 primary and then ran again in 1976, narrowly losing to the incumbent president, Gerald Ford. In 1980 Reagan crushed Carter, receiving over 50% of the popular vote and ten times the electoral vote. Reagan rode the wave of a powerful political movement historians have called the New Right. More libertarian in its economics and more conservative in its religious principles than the moderate conservatism popular after World War II, the New Right had by the 1980s evolved into the most influential wing of the Republican Party. The new conservative movement enjoyed the guidance of skilled politicians like Reagan and drew tremendous energy from grassroots activists. Newly mobilized Christian conservatives, in particular, helped the Republican Party steer the country rightward. Unpopular positions and internal party conflicts over race, economic policy, sexual politics, and foreign affairs fatally fractured the liberal consensus that had dominated American politics since the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt, and the New Right attracted support from Reagan Democrats, blue-collar voters who believed the party’s liberal agenda no longer represented their interests.

Ronald Reagan had been a B-list Hollywood actor before serving in a stateside public relations unit during World War II. Although originally a New Deal Democrat, Reagan became a Republican and cooperated with the HUAC investigations of the McCarthy era. He defeated two-term Democratic California governor Pat Brown in 1966 and served two terms himself; but he set his sights on the White House in 1968. In the primary, Reagan got more of the popular than Nixon but fewer delegates. He sat out the 1972 primary and then ran again in 1976, narrowly losing to the incumbent president, Gerald Ford. In 1980 Reagan crushed Carter, receiving over 50% of the popular vote and ten times the electoral vote. Reagan rode the wave of a powerful political movement historians have called the New Right. More libertarian in its economics and more conservative in its religious principles than the moderate conservatism popular after World War II, the New Right had by the 1980s evolved into the most influential wing of the Republican Party. The new conservative movement enjoyed the guidance of skilled politicians like Reagan and drew tremendous energy from grassroots activists. Newly mobilized Christian conservatives, in particular, helped the Republican Party steer the country rightward. Unpopular positions and internal party conflicts over race, economic policy, sexual politics, and foreign affairs fatally fractured the liberal consensus that had dominated American politics since the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt, and the New Right attracted support from Reagan Democrats, blue-collar voters who believed the party’s liberal agenda no longer represented their interests.

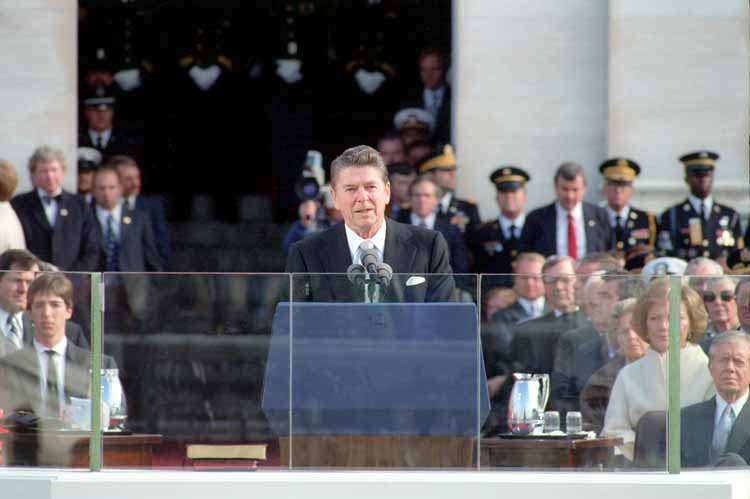

The rise of the right soon affected Americans’ everyday lives. The Reagan administration’s embrace of free markets reduced the active income redistribution and social welfare spending that had animated the New Deal and Great Society in the 1930s and 1960s. As American liberals increasingly embraced a “rights” framework directed toward African Americans, Latinos, women, lesbians and gays, Reagan complained of “Welfare Queens” who took advantage of the system. And following the lead set by Reagan when he claimed in his inaugural address that “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem,” conservative policy makers targeted the regulatory and legal landscape of the United States. Critics complained that Reagan’s policies served the interests of corporations and wealthy individuals, but the New Right harnessed popular distrust of regulation, taxes, and bureaucrats, and conservative activists celebrated the end of stagflation and substantial growth in GDP.

In many ways, however, the New Right promised more than it delivered. Many social welfare programs such as social security, Medicaid, and Aid to Families with Dependent Children survived the 1980s. And despite Republican vows of fiscal discipline, both the federal government and the national debt ballooned. At the end of the decade, conservative Christians viewed popular culture as more vulgar and hostile to their values than ever before. In the near term, the New Right won only partial victories on a range of public policies and cultural issues. Yet from a long-term perspective, conservatives achieved an enduring transformation of American politics and society. Liberals did not disappear, but they increasingly fought battles on terrain chosen by the New Right.

Race also drove the creation of the New Right. The civil rights movement, along with the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, challenged the racial hierarchy of the South. Jim Crow had been attacked under Democratic leadership, pushing many white southerners toward the Republican Party. Black Power, affirmative action, and court-ordered busing and integration of schools alienated whites in the North, often in cities previously known for political liberalism. At the same time, slowing wage growth, rising prices, and rising taxes threatened working- and middle-class families. Liberalism no longer seemed to offer many white Americans a path to prosperity, so they searched for new political solutions.

Christian conservatives also felt threatened by liberalism. In the early 1960s, the Supreme Court had prohibited teacher-led prayer and Bible reading in public schools. The counterculture’s celebration of sex and drugs, along with relaxed obscenity and pornography laws, convinced many that “permissive” liberalism encouraged immorality. Evangelical Protestants led a campaign to protect the “traditional” family. Many activists of the religious right were women who believed the Women’s Movement had gone too far. In 1968 and 1969 a group of mothers in California led a sustained protest against sex education in public schools. Catholic activist Phyllis Schlafly led opposition to the ERA while evangelical pop singer Anita Bryant convinced voters to repeal Miami’s gay rights ordinance in 1977. In 1979, Beverly LaHaye founded Concerned Women for America, which linked small groups of local activists opposed to the ERA, abortion, homosexuality, and no-fault divorce. Her husband, Tim, an evangelical pastor in San Diego, later coauthored the wildly popular Left Behind Christian book series.

Activists like Schlafly and LaHaye believed motherhood was women’s highest calling. Abortion struck at the core of female identity and drew different segments of the religious right together. The Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling outraged devout Catholics many evangelicals felt compelled to combat the procedure through political action. Grassroots passion drove anti-abortion activism, but new religious institutions turned the anti-abortion issue into a sophisticated movement. In 1979 Baptist minister and religious broadcaster Jerry Falwell founded the Moral Majority and dedicated it to advancing a “pro-life, pro-family, pro-morality, and pro-American” agenda. Conservative business leaders bankrolled new “think tanks” like the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute that embraced religion as they attacked regulation and “big government”. Together, New Right leaders took a more direct approach by hiring Washington lobbyists and creating political action committees (PACs) to push their agendas in the halls of Congress and federal agencies. Between 1976 and 1980 the number of corporate PACs rose from under three hundred to over twelve hundred.

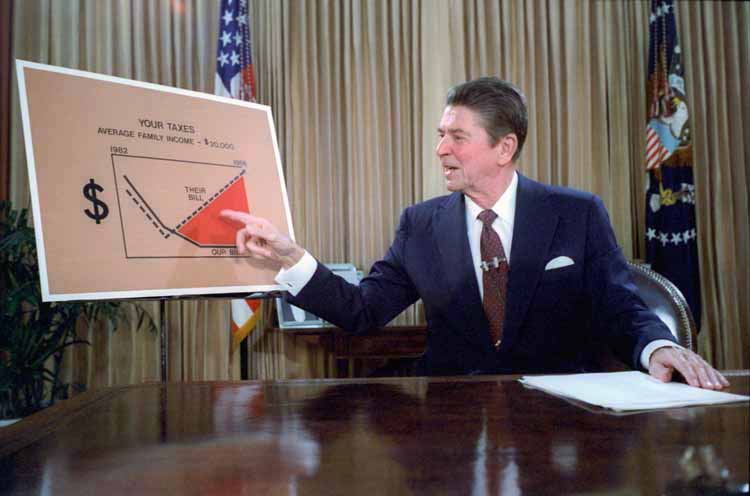

2. Morning in America

Many of the New Right’s concerns were symbolic and cultural. Reagan’s approach to government and the economy was similar. Once elected, Reagan focused less on eliminating government than on redirecting government to serve new ends. While New Deal Keynesian economics had focused on stimulating consumer demand, the Reagan administration’s supply-side economics claimed lower personal and corporate tax rates would encourage greater private investment and production. Supply-siders promised the resulting wealth would reach “trickle down” to lower-income groups through job creation and higher wages. Conservative economists predicted that lower tax rates would generate so much new economic activity that federal tax revenues would actually increase. Republican congressman Jack Kemp, co-sponsor of Reagan’s tax bill, promised that it would unleash the “creative genius that has always invigorated America.” The tax cut faced skepticism from Democrats and even some Republicans. Reagan’s vice president George H. W. Bush had called supply-side theory “voodoo economics” during the 1980 Republican primaries. But on March 30, 1981, Reagan survived an assassination attempt. Public support swelled for the hospitalized president and Congress approved a $675 billion tax cut in July. Federal taxes were reduced by more than one quarter and the top marginal rate fell from 70 percent to 50 percent. But Reagan remained a staunch anti-communist and ratcheted up tension with the Soviet Union. Congress also approved his request for $1.2 trillion in new military spending. The combination of lower taxes and higher defense budgets caused massive federal budget deficits and the national debt ballooned. By the end of Reagan’s first term it exceeded half of the nation’s GDP, compared to a third in 1981. The increase was staggering, especially for an administration that had promised to curb spending. Meanwhile, Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker continued his policy from the Carter years of combating inflation with high interest rates, which surpassed 20 percent in June 1981. The Fed increased the cost of borrowing money and stifled economic activity.

As a result, the United States experienced a severe economic recession in 1981 and 1982. Unemployment rose to nearly 11 percent, the highest figure since the Great Depression. Reagan also attacked unions during the strike of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO). During the 1980 campaign, Reagan had wooed organized labor, claiming to be “an old union man” who still held Franklin Roosevelt in high regard. Although PATCO had been one of the few labor unions to endorse Reagan, he ordered the striking air traffic controllers back to work and fired more than eleven thousand who refused. Reagan’s actions crippled PATCO the American labor movement. The unionized portion of the private-sector workforce fell from 20 percent in 1980 to 12 percent in 1990. Reductions in social welfare spending heightened the impact of the recession on ordinary people. Congress had followed Reagan’s lead by reducing funding for food stamps and Aid to Families with Dependent Children and removed a half million people from the Supplemental Social Security program for the physically disabled. Reagan also proposed cuts to social security benefits for early retirees. The Senate voted unanimously to condemn the plan, which Democrats framed as a heartless attack on the elderly. The New Right appeared to be in trouble.

Reagan nimbly adjusted to the political setbacks of 1982. Following the rejection of his social security proposals, Reagan appointed a bipartisan panel to consider changes to the program. In early 1983, the commission made its report and Congress quickly passed the recommendations into law, allowing Reagan to take credit for strengthening a program cherished by most Americans. The president also benefited from an economic rebound. Real disposable income rose and unemployment dropped in 1984. Meanwhile, the Fed’s high interest rates helped reduce inflation to 3.5 percent. Campaigning for reelection in 1984, Reagan cited the improving economy as evidence that it was “morning again in America.” His personal popularity soared. Most conservatives ignored the debt increase and tax hikes of the previous two years and rallied around the president. Former vice president Walter Mondale eventually secured the Democratic nomination but suffered a crushing defeat in the general election. Reagan captured forty-nine of fifty states, winning 58.8 percent of the popular vote.

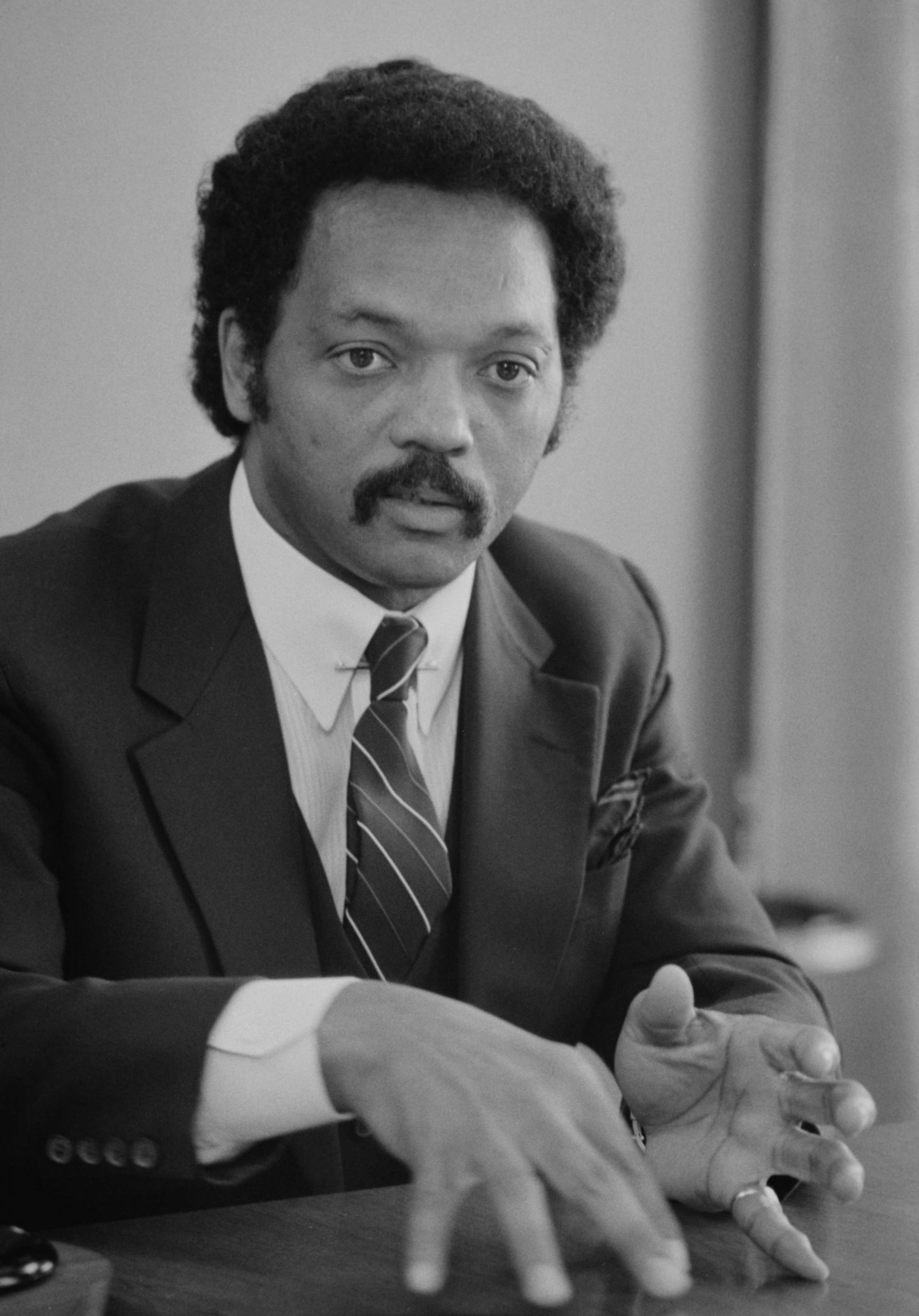

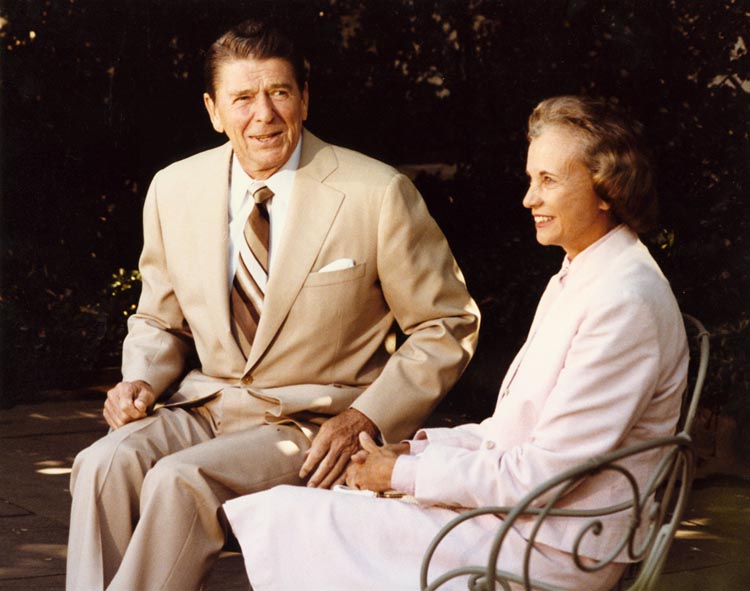

Mondale’s loss seemed to many Democrats to call for breed of moderates who better understood the mood of the American people. The future of the party belonged to post–New Deal politicians who could appeal to upwardly mobile, white professionals and suburbanites. In February 1985, a group of centrists formed the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) to begin distancing the party from organized labor and Keynesian economics while cultivating the business community. Civil Rights activist and presidential candidate Jesse Jackson dismissed the DLC as “Democrats for the Leisure Class,” but the organization included many of the party’s future leaders, including Arkansas governor Bill Clinton. The DLC illustrated how thoroughly the New Right had transformed American politics: New Democrats looked a lot like old Republicans. Democrats regained control of the Senate in 1986 and prevented Reagan from eliminating social welfare programs, although Congress failed to increase benefit levels or raise the minimum wage. Some of Reagan’s most far-reaching victories were his judicial appointments. Reagan named 368 district and federal appeals court judges during his two terms. Reagan also appointed three Supreme Court justices: Sandra Day O’Connor, who to the dismay of the religious right turned out to be a moderate; Anthony Kennedy, a solidly conservative Catholic who occasionally sided with the court’s liberal wing; and archconservative Antonin Scalia. In 1987, Reagan nominated Robert Bork to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court. Bork had opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, affirmative action, and the Roe v. Wade decision. After acrimonious confirmation hearings, the Senate rejected Bork’s nomination by a vote of 58–42.

3. Bad Times and Culture Wars

Working- and middle-class Americans, especially those of color, struggled to maintain economic equilibrium during the Reagan years. Foreign money poured into the United States to purchase high-interest government bonds, raising the value of the dollar. The strong dollar made US-produced goods more expensive than foreign products and attracted imports. America’s trade deficit, the excess of exports over imports, grew from $36 billion in 1980 to $170 billion in 1987. Foreign competition battered the manufacturing sector and the appeal of government bonds drew investment away from American industry. Competition from Japanese carmakers spurred a “Buy American” campaign. Meanwhile, a “farm crisis” gripped the rural United States. Expanded world production meant new competition for American farmers, while soaring interest rates caused the debt held by family farms to explode. Farm foreclosures skyrocketed during Reagan’s tenure. In September 1985, prominent musicians organized Farm Aid, a benefit concert at the University of Illinois’s football stadium designed to raise money for struggling farmers.

New Right values threatened the legal principles and federal policies of the Great Society and the “rights revolution.” Conservatives appointed to agencies such as the Justice Department and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission took aim at key policy achievements of the civil rights movement. The administration also tried to rescind federal affirmative action rules. In 1986, a broad coalition of groups including the NAACP, the Urban League, the AFL-CIO, and even the National Association of Manufacturers compelled the administration to abandon the effort. Spending cuts enacted by Reagan and congressional Republicans shrank Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Medicaid, food stamps, school lunch programs, and job training programs supporting disproportionately African American households. In 1982, the National Urban League’s annual “State of Black America” report concluded that “never [since the first report in 1976] . . . has the state of Black America been more vulnerable. Never in that time have black economic rights been under such powerful attack.” During Reagan’s last year in office the African American poverty rate stood at 31.6 percent, as opposed to 10.1 percent for whites. Black unemployment remained double that of whites throughout the decade. By 1990, the median income for black families was $21,423, 42 percent below the median income for white households. African American communities, especially in urban areas, also faced increasing violence and criminality. Homicide was the leading cause of death for black males between ages fifteen and twenty-four, occurring at a rate six times that of other groups. Although African Americans were most often the victims of violent crime, sensationalist media reports incited fears about black-on-white crime in big cities. Law enforcement agencies implemented more aggressive policing of minority communities and mandated longer prison sentences. The explosive growth of mass incarceration has damaged African American communities long into the twenty-first century.

American women pushed further into male-dominated spheres during the 1980s. By 1984, women in the workforce outnumbered those who worked in the home. New York representative Geraldine Ferraro became the first woman to run on a major party’s presidential ticket with Democratic candidate Walter Mondale. But women’s rights and especially abortion increasingly divided Americans along party lines. Pro-life Democrats and pro-choice Republicans grew rare, as the National Abortion Rights Action League enforced pro-choice orthodoxy on the left and the National Right to Life Commission did the same with pro-life orthodoxy on the right. Reagan, more interested in economic issues than social ones, provided only lukewarm support for the anti-abortion movement. He outraged anti-abortion activists by appointing Sandra Day O’Connor, a supporter of abortion rights, to the Supreme Court.

The emergence of a deadly new illness, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), simultaneously devastated, stigmatized, and energized the nation’s homosexual community. When AIDS appeared in the early 1980s, most of its victims were gay men. The Reagan administration met the issue with indifference, and some religious figures seemed to relish the opportunity to condemn homosexual activity. Catholic columnist Patrick Buchanan remarked that “the sexual revolution has begun to devour its children.” With the government unwilling to address the growing health crisis, homosexuals were left to forge their own response. Some turned to confrontation. New York playwright Larry Kramer founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, which demanded a more proactive response to the epidemic. Others worked to humanize AIDS victims with projects like the AIDS Memorial Quilt, begun in 1985. By the middle of the decade the federal government began to address the issue. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, an evangelical Christian, called for more federal funding on AIDS-related research, much to the dismay of critics on the religious right. In 1987 Reagan convened a presidential commission on AIDS that issued a report calling for anti-discrimination laws to protect people with AIDS and for more federal spending on AIDS research. The shift encouraged activists. Nevertheless, on issues of abortion and gay rights, activists spent the 1980s on defense, preserving the status quo rather than building on previous gains. This amounted to a significant victory for the New Right.

4. New Right Foreign Policy

The conservative movement gained ground on racial, gender, and sexual politics, but it captured the entire battlefield on American foreign policy in the 1980s. Ronald Reagan entered office a committed Cold Warrior. He held the Soviet Union in contempt, denouncing it in a 1983 speech as an “evil empire.” Reagan never doubted that the Soviet Union would end up “on the ash heap of history,” and he believed it was the duty of the United States to speed the Soviet Union to its inevitable demise. The Reagan Doctrine committed the United States to supplying aid to anticommunist forces worldwide. Federal spending on defense rose from $171 billion in 1981 to $229 billion in 1985, the highest level since the Vietnam War. Reagan described this as a policy of “peace through strength,” which appealed to Americans who feared the United States was losing its status as the world’s most powerful nation. American forces had withdrawn in disarray from South Vietnam in 1975. Jimmy Carter returned control of the Panama Canal to Panama in 1978, despite protests from conservatives. Pro-American dictators were toppled in Iran and Nicaragua in 1979. The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan and conservatives warned of American weakness in the face of Soviet expansion. Reagan agreed with fears of decline and warned, in 1976, that “this nation has become Number Two in a world where it is dangerous—if not fatal—to be second best.

The Reagan administration made Latin America a showcase for its aggressive new policies. Jimmy Carter had sought to promote human rights in the region, but Reagan instead focused on fighting communism. To Reagan, the term communism applied to all Latin American left-wing movements and anti-dictatorial resistance. When communists with ties to Cuba overthrew the government of the Caribbean nation of Grenada in October 1983, Reagan dispatched the U.S. Marines to the island. Dubbed Operation Urgent Fury, the Grenada invasion overthrew the leftist government after less than a week of fighting. Despite the minor scale and stakes of the mission, its success gave victory-hungry Americans something to cheer about after the military debacles of the previous two decades.

Grenada was the only time Reagan deployed American troops in Latin America, but the United States also influenced the region by supporting right-wing, anticommunist movements there. From 1981 to 1990, the United States gave more than $4 billion to the government of El Salvador in a futile effort to defeat the guerrillas of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). Salvadoran security forces equipped with American weapons committed numerous atrocities, including the slaughter of almost one thousand civilians at the village of El Mozote in December 1981. The Reagan administration took a more cautious approach in the Middle East, where its policy was determined by a mix of anticommunism and hostility toward the Islamic government of Iran. When Iraq invaded Iran in 1980, the United States supplied Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein with military intelligence and business credits, even after it became clear that Iraqi forces were using chemical weapons against Iranian soldiers and civilians. Reagan’s greatest setback in the Middle East came in 1982, when he dispatched Marines to the Lebanese city of Beirut to serve as a peacekeeping force. In October 1983, a suicide bomber killed 241 Marines stationed in Beirut. Congressional pressure and anger from the American public forced Reagan to recall the Marines from Lebanon in March 1984. Though Reagan’s policies toward Central America and the Middle East aroused protest, his policy on nuclear weapons generated the most controversy. Initially Reagan followed the examples of presidents Nixon, Ford, and Carter by pursuing arms limitation talks with the Soviet Union. But the breakdown of these talks in 1983 led Reagan to proceed with plans to place Pershing II medium-range nuclear missiles in Western Europe to counter Soviet SS-20 missiles in Eastern Europe. Reagan went a step further in March 1983, when he announced plans for a Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a space-based system he claimed would be able to shoot down incoming Soviet missiles. Critics derided the program as a “Star Wars” fantasy, and even Reagan’s advisors harbored doubts. “We don’t have the technology to do this,” secretary of state George Shultz told aides. These aggressive policies fed a growing nuclear freeze movement throughout the world. In the United States, organizations like the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy organized protests that culminated in a June 1982 rally that drew almost a million people to New York City’s Central Park.

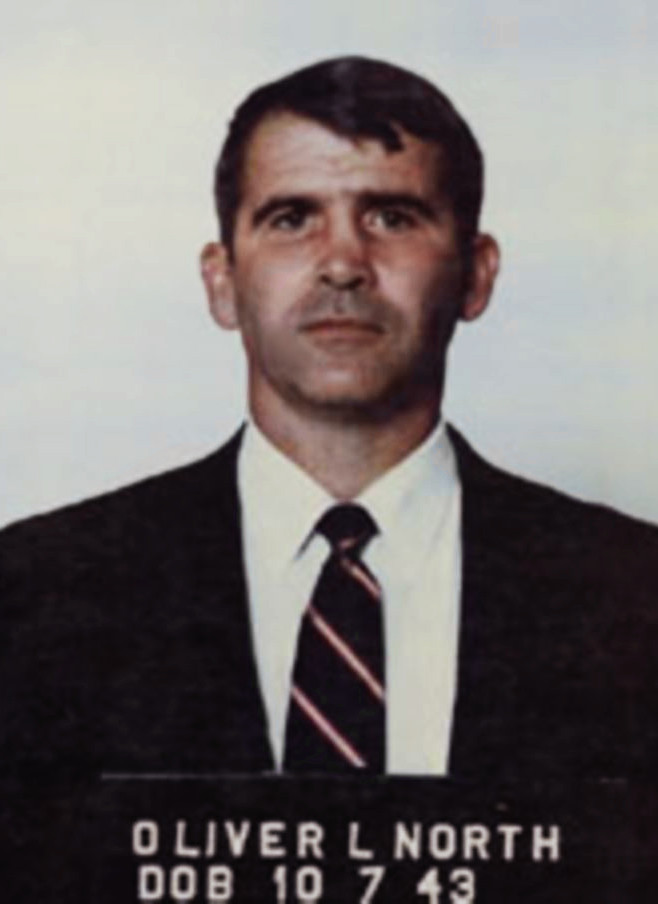

Protests in the streets were echoed by resistance in Congress. Congressional Democrats opposed Reagan’s policies while Republicans, though they supported Reagan’s anticommunism, were increasingly alarmed by the administration’s policy of circumventing Congress. In 1982, the House voted 411–0 to bar the United States from supplying funds to the contras, a right-wing insurgency fighting the leftist Sandinista government in Nicaragua. Reagan, overlooking the contras’ brutal tactics, enthusiastically described them as the “moral equivalent of the Founding Fathers.” The Reagan administration’s determination to ignore Congress led to a scandal that almost destroyed Reagan’s presidency. Robert MacFarlane, the president’s national security advisor, and Oliver North, a member of the National Security Council, raised money to support the contras by secretly selling American missiles to Iran and funneling the money to Nicaragua. When their scheme was revealed in 1986, it was hugely embarrassing for Reagan. The president’s agents had not only broken the law but had also armed an enemy that had held Americans hostage for 444 days, despite Reagan’s declaration that “America will never make concessions to the terrorists.” But while the Iran-Contra affair generated comparisons to the Watergate scandal, investigators were never able to agree that Reagan knew about the operation. And although the Iran-Contra scandal tarnished the Reagan administration’s image, it did not derail Reagan’s most significant achievement: easing tensions with the Soviet Union. In 1985 leadership of the Soviet Union passed to Mikhail Gorbachev, who realized that the Soviet Union desperately needed to reform itself. He instituted programs of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (transparency), and approached Reagan to negotiate an end to the arms race which was bankrupting the Soviet Union. Reagan and Gorbachev met in Switzerland in 1985 and Iceland in 1986. The two leaders developed a relationship that led to the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty of 1987, which committed both sides to a sharp reduction in their nuclear arsenal.

9. Sources and References

First Inaugural Address of Ronald Reagan (1981)

Ronald Reagan, a former actor, corporate spokesperson, and California governor, won the presidency in 1980 with a potent mix of personal charisma and conservative politics. In his first inaugural address, Reagan famously declared that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

Jerry Falwell on the “Homosexual Revolution” (1981)

“Letter from Jerry Falwell on his opposition to homosexuality and asking for support in keeping his “Old-Time Gospel Hour” television program on the air. Falwell writes that the Old Time Gospel Hour “is one of the few major ministries in America crying out against militant homosexuals” (p. 1). The letter is printed on what appears to be lined yellow notepad paper.”

Statements of AIDS Patients (1983)

HIV/AIDS confronted Americans in the 1980s. The disease was first associated with gay men (it was initially called Gay-Related Immune Disease, or GRID) and AIDS sufferers fought for recognition of the disease’s magnitude, petitioned for research funds, and battled against popular stigma associated with the disease.

Statements from The Parents Music Resource Center (1985)

In 1985, the Senate held hearings on explicit music. The Parents Music Resource Center (1985), founded by the wives of prominent politicians in Washington D.C., publicly denounced lyrics, album covers, and music videos dealing with sex, violence, and drug use. The PRMC pressured music publishers and retailers and singled out artists such as Judas Priest, Prince, AC/DC, Madonna, and Black Sabbath, and Cyndi Lauper. The following is extracted from statements by Susan Baker, the wife of then-Treasury Secretary James Baker, and Tipper Gore, wife of Senator and later Vice President Al Gore, in support of warning labels on music packaging.

Pat Buchanan on the Culture War (1992)

Pat Buchanan was a conservative journalist who worked in the Nixon and Reagan administrations before running for the Republican presidential nomination in 1992. Although he lost the nomination to George H.W. Bush, he was invited to speak at that year’s Republican National Convention, where he delivered a fiery address criticizing liberals and declaring a “culture war” at the heart of American life.

Satellites Imagined in Orbit (1981)

While Cold War fears still preyed upon Americans, satellite technology and advancements in telecommunications inspired hopes for an interconnected future. Here, an artist in 1981 depicts various satellites in orbit around the Earth.

Ronald Reagan and the American Flag (1982)

President Ronald Reagan, a master of the “photo op,” appears here with a row of American flags at his back at a 1982 rally for Senator David Durenberger in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Bill Clinton on Free Trade and Financial Deregulation (1993-2000)

During his time in office, Bill Clinton passed the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) in 1993, allowing for the free movement of goods between Mexico, the United States, and Canada, signed legislation repealing the Glass-Steagall Act, a major plank of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal banking regulation, and deregulated the trading of derivatives, including credit default swaps, a complicated financial instrument that would play a key role in the 2007-2008 economic crash. In the following signing statements, Clinton offers his support of free trade and deregulation.

This chapter was written by Dan Allosso, adapting material that first appeared in Chapters 29 and 30 of The American Yawp, with additional original content. the original chapters were edited by Michael Hammond, Richard Anderson, and William J. Schultz with content contributions by Richard Anderson, Laila Ballout, Marsha Barrett, Seth Bartee, Eladio Bobadilla, Kyle Burke, Andrew Chadwick, Aaron Cowan, Jennifer Donnally, Leif Fredrickson, Kori Graves, Karissa A. Haugeberg, Jonathan Hunt, Stephen Koeth, Colin Reynolds, William J. Schultz, Daniel Spillman, Andrew Chadwick, Zach Fredman, Michael Hammond, Richard Hayward, Joseph Locke, Mark Kukis, Shaul Mitelpunkt, Michelle Reeves, Elizabeth Skilton, Bill Speer, and Ben Wright.

Recommended Reading:

- Brier, Jennifer. Infectious Ideas: U.S. Political Responses to the AIDS Crisis.Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics.Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1995.

- Carter, Dan T. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963–1994. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1996.

- Chappell, Marisa. The War on Welfare: Family, Poverty, and Politics in Modern America.Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

- Cowie, Jefferson. Capital Moves: RCA’s 70-Year Quest for Cheap Labor. New York: New Press, 2001.

- Crespino, Joseph. In Search of Another Country: Mississippi and the Conservative Counterrevolution.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Critchlow, Donald. The Conservative Ascendancy: How the GOP Right Made Political History.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Dallek, Matthew. The Right Moment: Ronald Reagan’s First Victory and the Decisive Turning Point in American Politics.New York: Free Press, 2000.

- Ehrenreich, Barbara. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. New York: Metropolitan, 2001.

- Evans, Sara. Tidal Wave: How Women Changed America at Century’s End. New York: Free Press, 2003.

- Gardner, Lloyd C. The Long Road to Baghdad: A History of U.S. Foreign Policy from the 1970s to the Present. New York: Free Press, 2008.

- Hinton, Elizabeth. From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Hollinger, David. Postethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

- Hunter, James D. Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America.New York: Basic Books, 1992.

- Kalman, Laura. Right Star Rising: A New Politics, 1974–1980.New York: Norton, 2010.

- Kruse, Kevin M. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Lassiter, Matthew D. The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- MacLean, Nancy. Freedom Is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

- Meyerowitz, Joanne. How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Mittelstadt, Jennifer. The Rise of the Military Welfare State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Moreton, Bethany. To Serve God and Walmart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Nadasen, Premilla. Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States.New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Nickerson, Michelle M. Mothers of Conservatism: Women and the Postwar Right.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Osnos, Evan. Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth and Faith in the New China. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014.

- Packer, George. The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

- Patterson, James T. Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore.New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Phillips-Fein, Kim. Invisible Hands: The Businessmen’s Crusade Against the New Deal.New York: Norton, 2010.

- Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Translated from the French by Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2013.

- Rodgers, Daniel T. Age of Fracture.Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2011.

- Schlosser, Eric. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001.

- Schoenwald, Jonathan. A Time for Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism.New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Self, Robert O. All in the Family: The Realignment of American Democracy Since the 1960s.New York: Hill and Wang, 2012.

- Stiglitz, Joseph. Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. New York: Norton, 2010.

- Taylor, Paul. The Next America: Boomers, Millennials, and the Looming Generational Showdown. New York: Public Affairs, 2014.

- Troy, Gil. Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Westad, Odd Arne. The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times.New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Wilentz, Sean. The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008.New York: HarperCollins, 2008.

- Williams, Daniel K. God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right.New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Wright, Lawrence. The Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Knopf, 2006.

- Zaretsky, Natasha. No Direction Home: The American Family and the Fear of National Decline.Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Media Attributions

- Reagan_1980_campaign © Ronald Reagan Library is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Let’s_Make_America_Great_Again_button © Ronald Reagan presidential campaign is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Reagan_delivers_inaugural_address_1981 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 00757v © Warren K. Leffler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Reagans_waving_from_the_limousine_during_the_Inaugural_Parade_1981 © White House Photographic Office is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ronald_Reagan_televised_address_from_the_Oval_Office,_outlining_plan_for_Tax_Reduction_Legislation_July_1981 © White House Photo Office is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Jesse_Jackson,_half-length_portrait_of_Jackson_seated_at_a_table,_July_1,_1983_edit © Warren K. Leffler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- President_Reagan_and_Sandra_Day_O’Connor © White House Photographic Office is licensed under a Public Domain license

- default © Carol M. Highsmith is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 82nd_Airborne_soldiers_on_Grenada_1983 © Sgt. Michael Bogdanowicz is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Oliver_North_mug_shot © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Reagan_and_Gorbachev_hold_discussions © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license