5 The Great War

Before the Second World War, what we now call World War I was known simply as “The Great War.” It wasn’t the first war fought in multiple regions of the world by most of the world’s major powers. The Seven Years War of 1756 to 1761, which Americans generally call the French and Indian War after the part fought in North America, probably has a better claim to the title of the first world war. But the conflict from 1914 to 1919 is especially significant in American history because the United States emerged from it as a world military power and as the financial center of the global economy.

The Great War toppled empires, created new nations, and sparked tensions that would explode across future years; especially in the Second World War less than a generation later. On the battlefield, gruesome modern weaponry killed or terrorized an entire generation of young men. The U. S. entered the conflict in 1917 and was never again the same. The war announced to the world the United States’ arrival as a global power and its aftermath advanced an idealistic vision of a new global order, but ironically the U. S. wartime experience beat back American progressivism by unleashing vicious waves of repression. The war simultaneously stoked national pride and fueled disenchantments that burst Progressive Era hopes for the modern world. And it laid the foundation for a global depression, a second world war, and a whole new era of national, religious, and cultural conflict around the globe.

Foreign Entanglement

Germany rose in power and influence during the final decades of the nineteenth century, after its unification in 1871 under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Twenty-six kingdoms, grand duchies, principalities, and free cities were merged into a nation that thought of itself as an empire (and named itself the Deutsches Reich). The new Germany had a population of 41 million and was an industrial powerhouse. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, Germany surpassed Britain to become the largest economy in Europe and second in the world, behind the U.S. German scientists won more Nobel Prizes than any other nation. The German navy was second only to the British Royal Navy.

In 1888, Kaiser Wilhelm II took the imperial throne. Wilhelm was a member of the Hohenzollern dynasty and was the grandson of Queen Victoria of England. Perhaps taking his cue from the British Empire, Wilhelm launched Germany on a “New Course” toward imperialism. Wilhelm ordered his military leaders to read Alfred Thayer Mahan’s book, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, which had so impressed Theodore Roosevelt in America. He dismissed Bismarck as Chancellor in 1890 and began looking for ways to make Germany a colonial empire. When Wilhelm’s ally and personal friend, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife were assassinated on June 28, 1914 by a Serbian revolutionary named Gavrilo Princip, the European powers used the event to begin a war they had spent the last two decades preparing to fight. Russia and France had established a defensive alliance to counter the threat of Germany and Austria-Hungary in the Balkan region as the Ottoman Empire’s power declined. Queen Victoria had tried to avoid taking sides, but her successors Edward II and George V entered alliances against their relative Wilhelm, especially after his navy began to challenge theirs. The alliance between Great Britain, France, and Russia became known as the Triple Entente. The elaborate series of mutual defense treaties made war nearly inevitable.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the United States had a long tradition of resisting being drawn into internal European politics. American attitudes toward international affairs followed the advice given by President George Washington in his 1796 Farewell Address. Washington had urged his countrymen to avoid “foreign alliances, attachments, and intrigues”, warning against “those overgrown military establishments which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to republican liberty.” The government avoided participating in international diplomatic alliances and focused on championing the expansion of the transatlantic economy. American businesses and consumers benefited from the trade generated by nearly a century of European peace.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did most Americans prefer not to become involved in European conflicts?

- How did relationships between nations (and between their rulers) influence the beginning of the world war?

A foreign policy of neutrality also reflected America’s focus on the construction and management of its new powerful industrial economy, built in large part with loans and investments from Europe and especially London. U.S. dependency on foreign capital began to change when American bankers began making substantial loans to Britain and France. John Pierpont Morgan had died in 1913 and his successor, J.P. Morgan Jr. leveraged a friendship with British Ambassador Cecil Spring Rice to have the Morgan bank designated sole source U. S. purchasing agent for both Britain and France. J.P. Morgan and Company managed the allies’ purchases of munitions, food, steel, chemicals, and cotton; receiving a 1% commission on all sales. Morgan led a consortium of over 2,000 banks and managed loans to the allies that exceeded $500 million (nearly $13 billion in today’s dollars). Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State, the populist-leaning William Jennings Bryan, objected to the loans and argued that by denying financing to any of the belligerents, the U. S. could hasten the end of the war. But a quick end to the war wasn’t the bankers’ goal.

J. P. Morgan and Company’s Managing Director, Thomas Lamont presented his views in a 1915 speech to the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Lamont observed that the war offered the United States a unique opportunity to shift from being a debtor nation, dependent on loans from Europe and Britain, to becoming a global creditor. “We are piling up a prodigious export trade [with] war orders,” he said, “running into the hundreds of millions of dollars.” America was poised, Lamont concluded, to become the trade and finance center of the world, and the U.S. dollar to replace the British pound sterling as the world’s currency. But this would only happen, he warned, “if the war goes on long enough” A quick end to hostilities would allow Germany to rapidly regain its competitive position. The best result for America would be a long war that ended in German defeat and left the winners deeply in debt to the U. S.

It was a good thing, in a way, that America was not keen to enter the fighting. The European powers had been building up their military capabilities for nearly a generation before the outbreak of war, and it was unclear whether the United States could mobilize rapidly. Congress had authorized the construction of a modern navy and the Great White Fleet had sailed around the world between 1907 and 1909. But the army remained small and underfunded compared to the armies of Europe. The National Defense Act of 1916 authorized the building of the National Guard and military reserves. A system of state-administered units available for local emergencies could be activated by the president for use in international wars. The program also supplied summer training for college students as a reserve officer corps and allocated federal funds to train and drill reservists and the Guard. Finally, the Act created an Aviation Section of the Army and allocated $17 million to build 375 airplanes. The threat of war in Europe also enabled passage of the Naval Act of 1916. President Wilson pledged to insure the U. S. Navy was “incomparably, the greatest…in the world.”

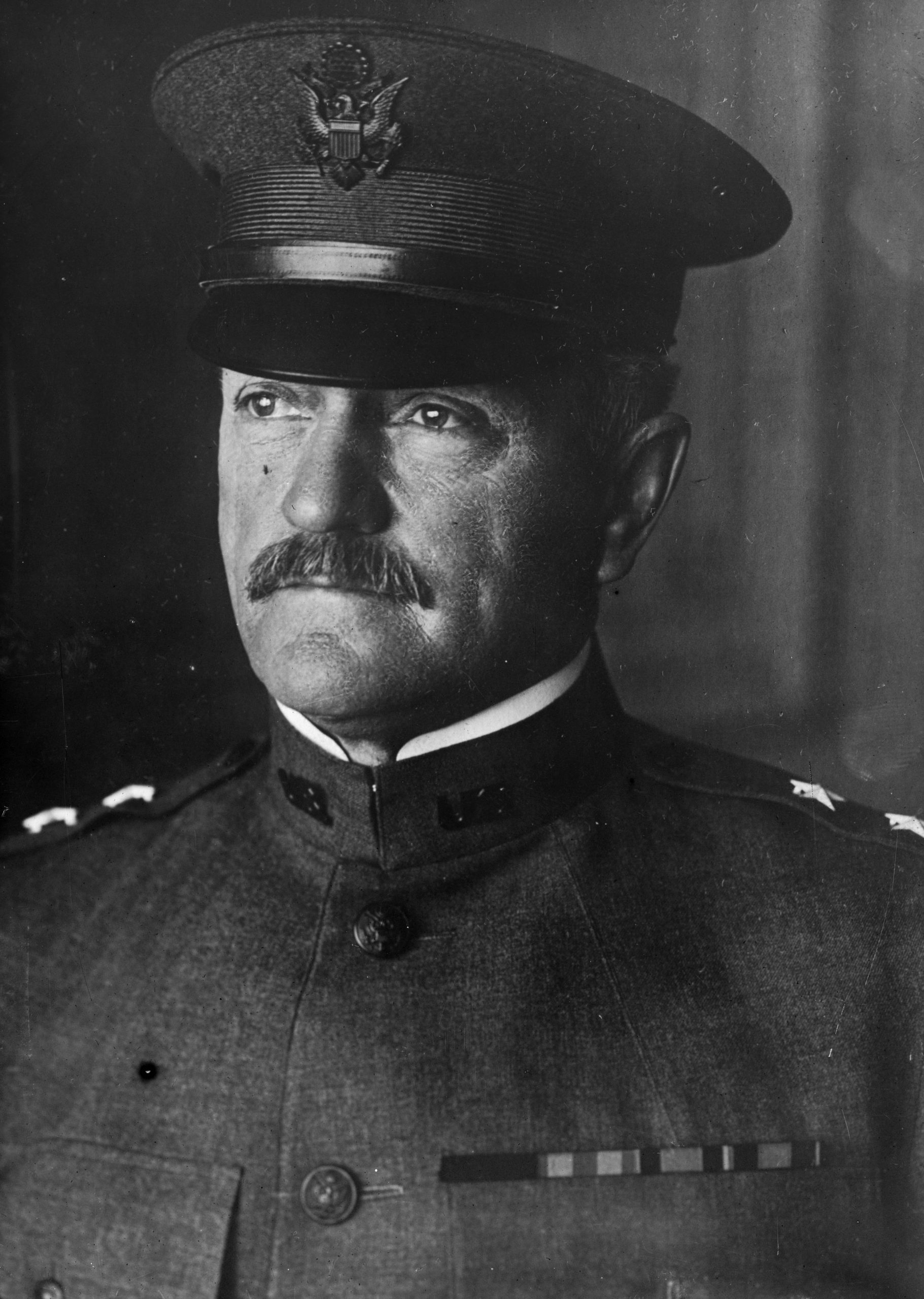

Border troubles in Mexico served as an important field test for modern American military forces and the National Guard. Revolution and chaos threatened American business interests when Mexican reformer Francisco Madero challenged Porfirio Diaz’s corrupt and unpopular regime. Madero was jailed, fled to San Antonio, and wrote the Plan of San Luis Potosí, paving the way for the Mexican Revolution. In April 1914, President Wilson had ordered Marines to accompany a naval escort to Veracruz on the eastern coast of Mexico. The Wilson administration had withdrawn its support of Diaz but watched warily as the revolution devolved into assassinations and chaos. In 1916, provoked by American support for his rivals, Pancho Villa raided Columbus, New Mexico. His troops killed seventeen Americans and burned down the town center. President Wilson commissioned General John “Black Jack” Pershing to capture Villa and disperse his rebels and used the powers of the new National Defense Act to mobilize over one hundred thousand National Guard units across the country as an invasion force in northern Mexico.

The European war had begun in August 1914 with a German advance into Belgium in an effort to encircle Paris. Both sides, however, had machine guns and artillery, and the German advance was halted after about a month at the Battle of the Marne. Technologically advanced nations had previously restricted their use of weapons like Gatling Guns, Hotchkiss Cannons, and Maxim Guns to suppress natives and expand their imperial reach in the American West, Africa, and the Middle East. When they deployed these weapons against each other, the war quickly became a static conflict fought from trenches dug in the fall of 1914 and occupied for the next five years. Trenches extended from the Swiss border in the south to the North Sea coast in Belgium, becoming a symbol of the futility of the war.

The conflict on the Eastern Front, between Germany and Russia, was more mobile. In 1916, as the months-long Battle of Verdun seemed to be going against the French, the Russian Army overwhelmed Austrian forces and forced the Germans to divert their forces from the Western Front. Peripheral campaigns against the Ottoman Empire at Gallipoli, throughout the Middle East, and in various parts of Africa had little bearing on the European contest for victory. The third year of the war, however, witnessed a major change in German military prospects when the Romanov Dynasty of Tsar Nicholas II collapsed in Russia in March 1917. The trouble had begun in late February with a strike by women factory workers in St. Petersburg. 90,000 women took to the streets shouting “Bread!”, “Down with the autocracy!”, and “Stop the war!” The following day, over 150,000 men and women marched and a general strike began. Within a few days the army had sided with the revolutionaries and Nicholas II was forced to abdicate. Since the revolutionaries and the army wanted to end their participation in the war, it was expected Germany would be able to devote all its resources on the Western Front.

Questions for Discussion

- Evaluate the bankers’ reasons for the position they took regarding the war. What factors do you think might cause them to change their opinions?

- What effect do you think the Russian Revolution had on military planners on both sides?

America Enters the War

In spite of the bankers’ interest in profiting on the European conflict, the federal government faced strong public opinion against entering what Americans saw as a fight they had no stake in. Scandinavians and German immigrants (the largest immigrant group in America) declared both their neutrality and their general impression that Germany’s culture was superior to that of its European rivals. The Irish, who had no love of England, were a powerful force in the Democratic party. Business leaders and social activists like Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, and Jane Addams were pacifists. Poor southerners reminded America that “a rich man’s war meant a poor man’s fight”. Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor, denounced the war in 1914 as “unnatural, unjustified, and unholy.” And socialist pamphlets argued that “a bayonet was a weapon with a worker at each end.” Woodrow Wilson ran for re-election in 1916 on the slogan, “He kept us out of war.” But only a month after his second inauguration, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917.

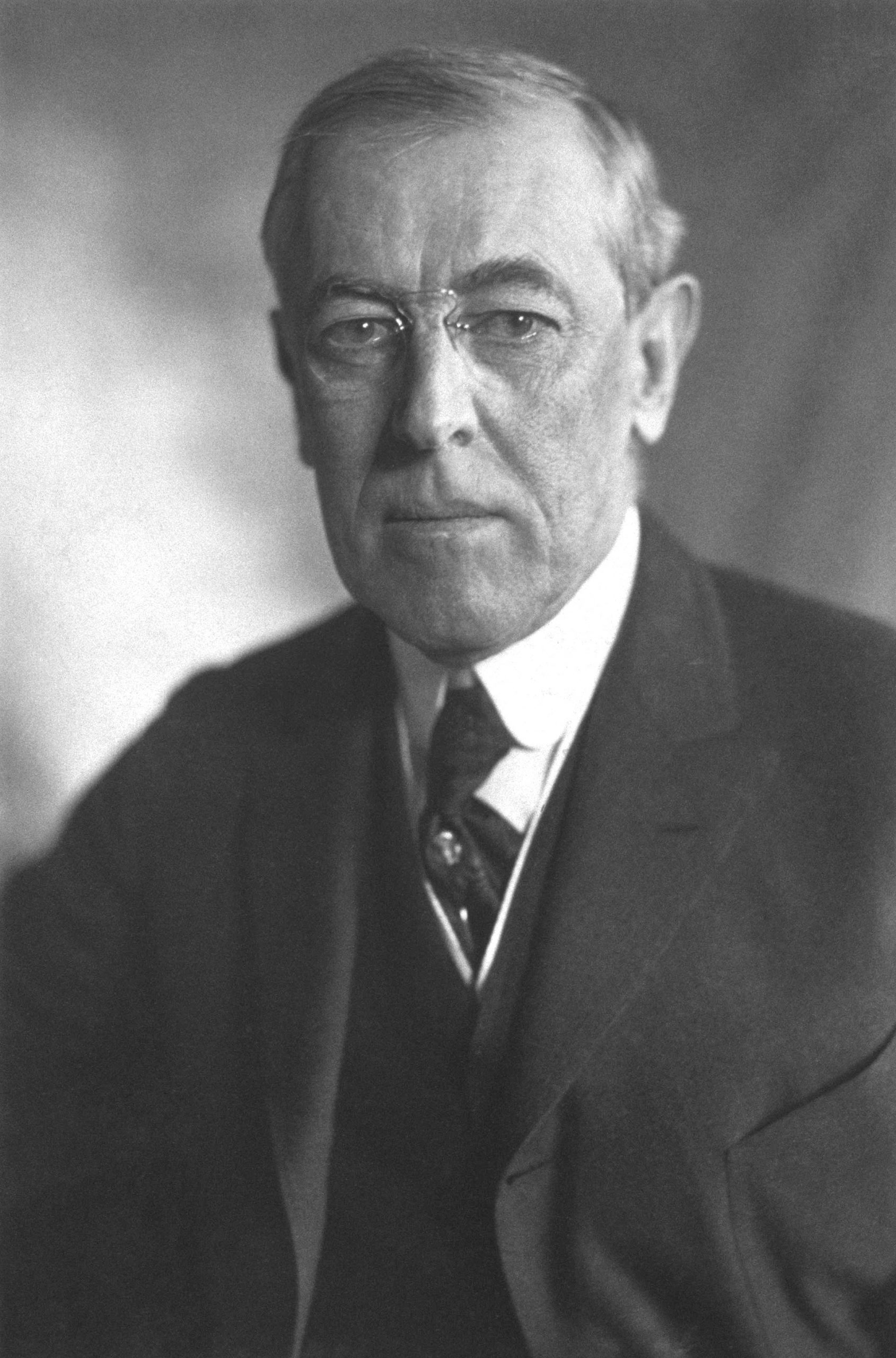

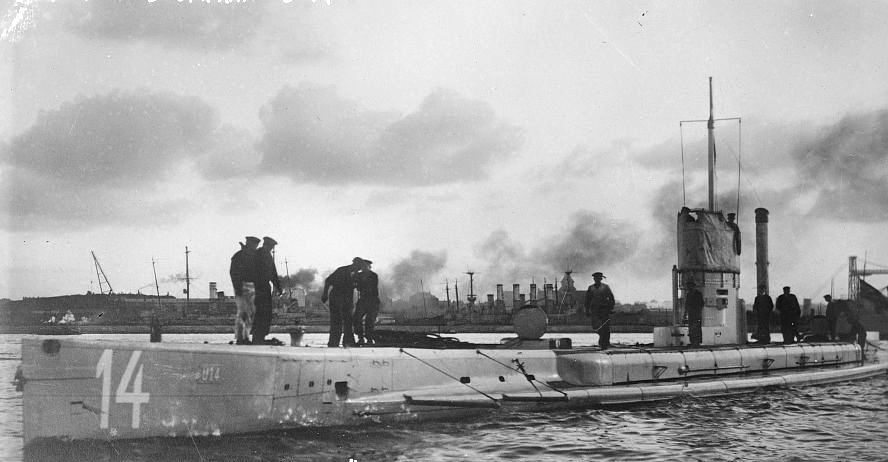

By the spring of 1917, President Wilson believed a German victory would drastically and dangerously alter the balance of power in Europe. But he had promised to keep the U. S. out of the war. Submarine warfare had been a problem earlier in the conflict, when Germany had been able to sink American ships carrying supplies for Britain and France. A passenger ship, the Lusitania, had been sunk by a German U-boat in early 1915, killing 1,198 passengers and crew, including 128 Americans. Germany had ended unrestricted submarine warfare at U. S. insistence, but in early 1917 they resumed U-boat attacks in an effort to starve the British. Finally, a document called the Zimmerman Telegram surfaced. When decoded it proved to be a suggestion from an official of the German foreign office to the German ambassador in Mexico that if the U. S. entered the war, Mexico should be encouraged to invade America to regain the territory taken in the Mexican-American War. Many Americans doubted the authenticity of the telegram, especially because it was delivered by British intelligence officers to the secretary of the U. S. Embassy in London. Zimmerman soon acknowledged its authenticity, claiming he had only been suggesting a Mexican invasion if the United States had already entered the war. The Mexicans, for their part, announced they had never seriously considered the German suggestion. With American public opinion finally behind him, President Wilson went to Congress in February, 1917 to announce that diplomatic relations with Germany had been severed. On April 2, Wilson returned with a “War Message” that included the argument that “The present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.” Congress declared war on Germany on April 4, 1917.

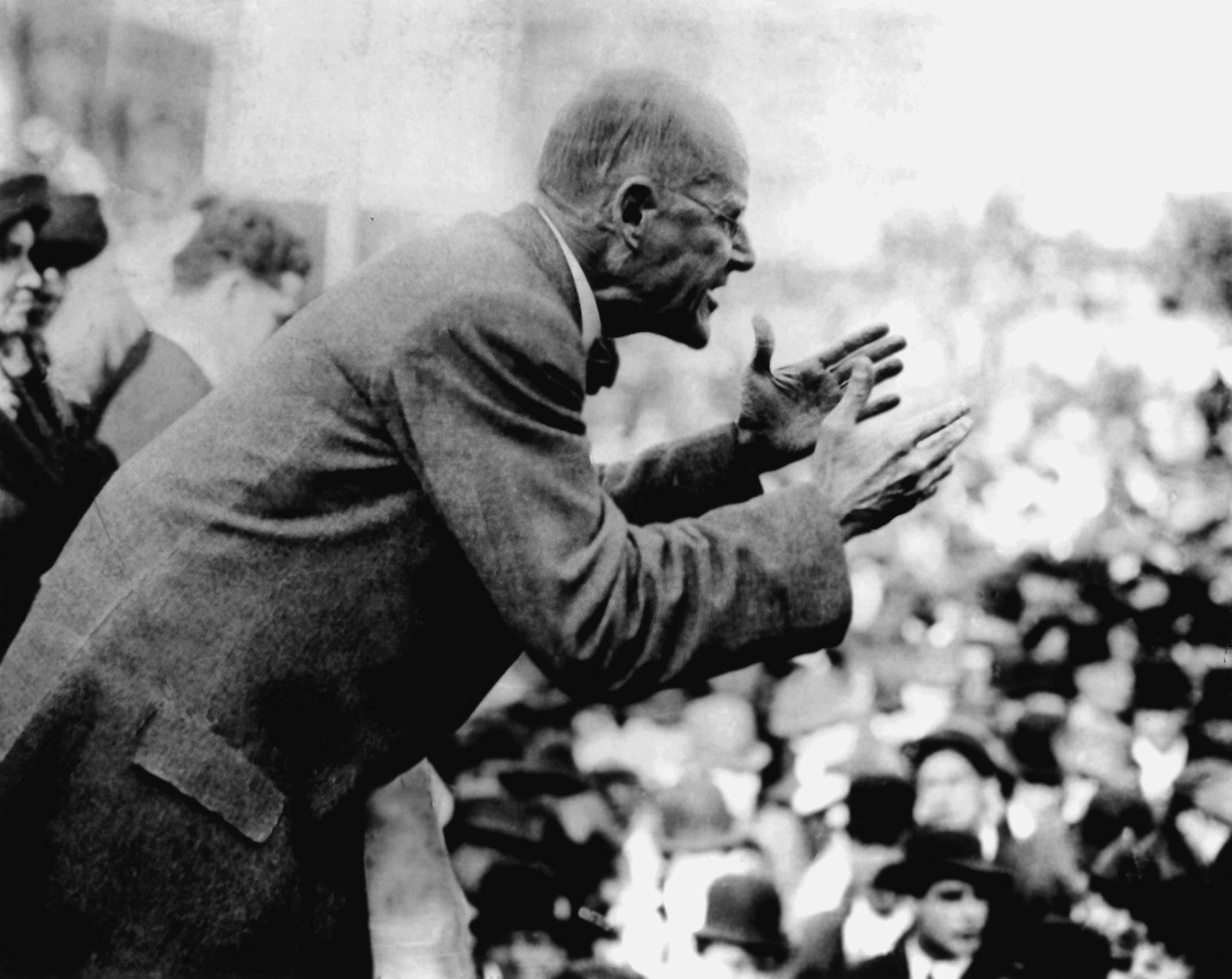

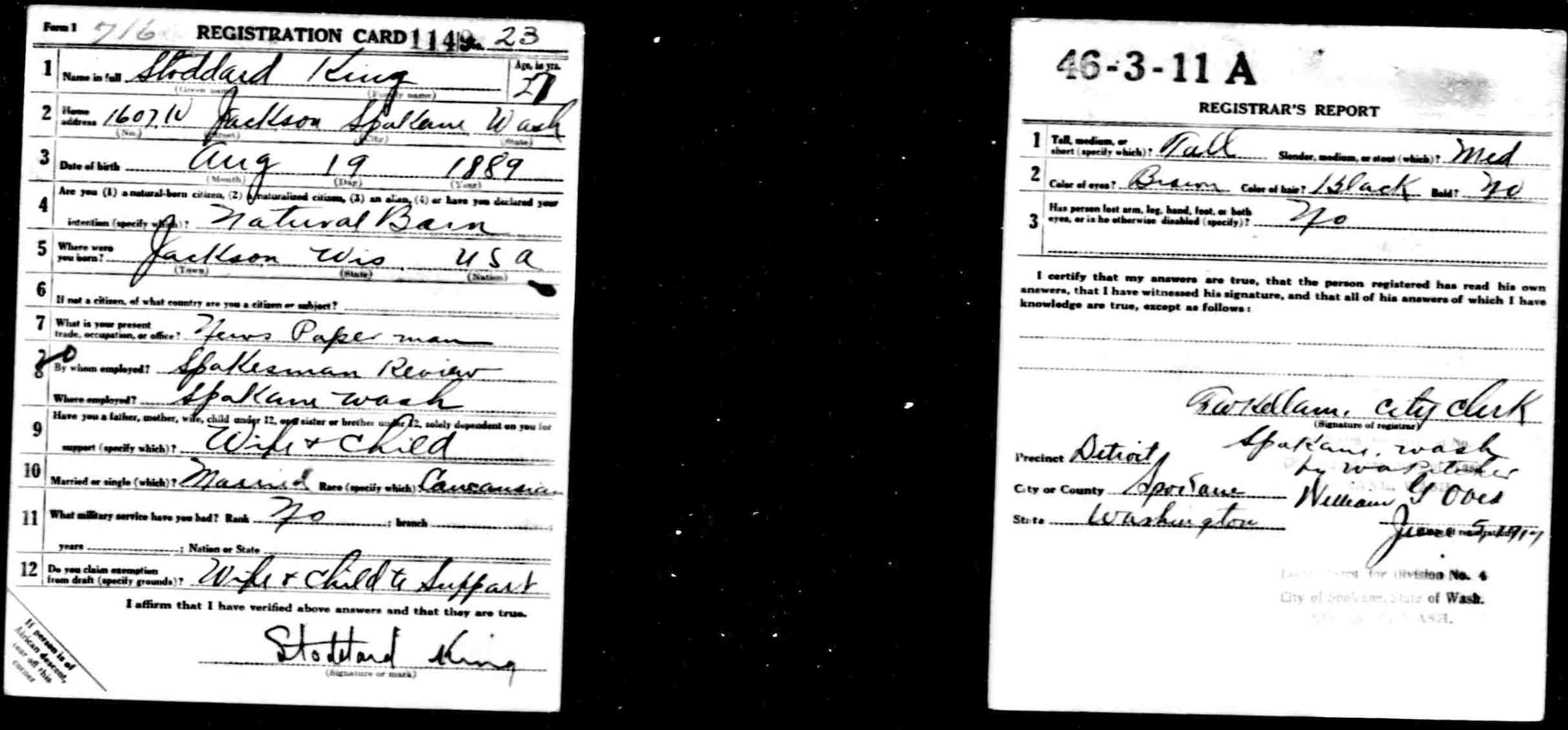

Considerable time elapsed before an effective force could be deployed to the Western Front in Europe. To pay for the military build-up, the government increased the federal income tax which had become legal in 1913. The War Revenue Act of 1917 reduced the lowest tax bracket to $2,000 and increased the maximum tax rate to 67%. The process of building the army and navy for the war also proved different from previous conflicts. The U.S. had historically relied mostly on volunteers to fill the ranks of the armed forces. Notions of patriotic duty and adventure appealed to many young men. American labor organizations favored voluntary service over conscription. A.F.L. leader Samuel Gompers changed his stance to support for the war effort but argued for volunteerism in letters to the congressional committees considering the question. “The organized labor movement,” he wrote, “has always been fundamentally opposed to compulsion.” Referring to American values as a role model for others, he continued, “It is the hope of organized labor to demonstrate that under voluntary conditions and institutions the Republic of the United States can mobilize its greatest strength.” But in the six weeks following the declaration of war, only 73,000 men volunteered for service. So, despite fears of popular resistance, Congress approved the Selective Service Act of 1917. The new draft law required all men between the ages of 18 and 30 to register; the following year the top age was raised to 45. Facing the potential of being drafted, 2 million American men volunteered. Another 2.8 million were drafted into service. Although some labor unions decided to support the war, others like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) opposed the war and called on members to resist the draft. Labor leader and recent presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs was convicted of sedition.

The government had moved quickly to eliminate any signs of dissent, passing the Espionage Act in June, 1917. Woodrow Wilson declared the act was designed to prosecute those who had “poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who have sought to bring the good name of our Government into contempt, to destroy our industries wherever they thought it effective for their vindictive purposes to strike at them, and to debase our politics to the uses of foreign intrigue.” Although Wilson implied that the people he intended to target were “born under other flags,” most like Debs were American citizens. Wilson also deliberately used the word “strike” to suggest that labor unions’ actions to defend worker rights during wartime would be considered an attack on America. The law was expanded with the Sedition Act of 1918, which prohibited any forms of speech that could be considered “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States…or the flag of the United States, or the uniform of the Army or Navy.” In addition to anti-draft activists, pacifists such as the directors of the Watchtower Society were imprisoned for suggesting in a religious tract that based on their understanding of the New Testament, “Everywhere and always murder in its every form is forbidden.” And as the Russian Revolution was taken over by the Marxist Bolshevik Party, prosecutors’ concern shifted from draft resistance to socialism and a Red Scare gripped America. Hundreds were arrested, deported, and jailed under the Espionage and Sedition Acts. By 1919 even the authorities realized they had gone a bit too far, and the U. S. Attorney General convinced President Wilson to commute the sentences of 200 prisoners convicted under the acts.

Under the draft law, basic physical fitness was the primary requirement for service. The Army Medical Department tested the general condition of young American men and selected those deemed healthy for service. The Surgeon General compiled his findings in the 1919 report, “Defects Found in Drafted Men,” a snapshot of 2.5 million men examined for military service. In that group, 1,533,937 physical defects were recorded, often more than one per individual. More than 34 percent of the men examined were rejected for service or later discharged for neurological, psychiatric, or mental deficiencies. The army used cognitive skills tests to determine intelligence. About 1.9 million men were tested and Army psychologists concluded that the average mental age of recruits was only about thirteen years. Eugenicists interpreted the results as mild retardation and as an indication of racial deterioration. Years later, experts agreed that the results misrepresented the levels of education for the recruits and revealed defects in the design of the tests.

Questions for Discussion

- What did it take for the American people to support US entry into the war?

- Why was instituting the draft a contentious decision?

- How did the ongoing Russian Revolution and the growing prominence of the Bolsheviks influence U.S. government policy?

Opportunities to Serve

The experience of service in the army expanded young men’s social horizons as native-born and foreign-born soldiers served together. Although immigrants including large numbers of Irish and Germans had been welcomed into Union ranks during the Civil War, between 1917 and 1918, the army accepted immigrants with some hesitancy because of the widespread public agitation against “hyphenated Americans.” German Americans were especially distrusted because of suspicions regarding their loyalty. Others were segregated. Racist attitudes among many white Americans mandated the assignment of white and black soldiers to different units. Despite racial discrimination, many African American leaders including W. E. B. Du Bois supported the war effort and encouraged service for black soldiers. Black leaders viewed military service as an opportunity to demonstrate to white society that black men were willing and able to assume all the duties and responsibilities of citizens, including wartime sacrifice. If black soldiers fought and died on equal footing with white soldiers, black leaders believed, white Americans would see that they deserved full citizenship. The War Department, however, barred black troops from combat and relegated black soldiers to segregated service units where they worked as general laborers.

In Europe, the experiences of black soldiers were often transformative. For example, the 15th New York National Guard Regiment, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, was one of the first African American regiments formed (it also included Puerto Rican Americans). Previously, black men who wanted to fight had been forced to enlist in the French or Canadian armies. Originally assigned to labor duties, the unit petitioned to be combat trained but white troops refused to cooperate. In a compromise, the unit was assigned to the French Army for the duration of the war. The French were happy to have the regiment and treated the men as equals. They spent 191 days in frontline trenches, more than any other U. S. troops. The unit also suffered more losses than any other American regiment with 1,500 casualties. The unit won a regimental Croix de Guerre decoration and was one of the first U. S. units to have black officers as well as troops.

Black soldiers found they were often treated better in Europe on their periods of leave than they had been at home. Recognizing the problems this might cause, the army often restricted the privileges of black soldiers to ensure that the conditions they encountered in Europe did not lead them to question their place in American society. However, black soldiers were not the only ones tempted by differences between wartime European culture and their lives at home. To ensure that American “doughboys” did not compromise what some American leaders saw as their special identity as men of the new world who had been sent to save the old, several religious organizations created programs designed to keep the men pure of heart, mind, and body. With assistance from the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and other temperance organizations, the War Department put together a program of schools, sightseeing tours, and recreations to provide wholesome and educational outlets. Soldiers welcomed most of the activities from these groups, but many still managed to find and enjoy the traditional recreations of soldiers at war.

Many women reacted to war preparations by joining military and civilian organizations. Most civilian wartime organizations, although chaired by male members of the business elite, had all-female volunteer workforces. Women performed the bulk of volunteer work during the war. And military leaders authorized a permanent gender transition of several support and clerical roles that gave women opportunities to don uniforms where none had existed before in history. The War and Navy Departments authorized the enlistment of women to fill positions in several administrative occupations, freeing more men to join combat units. Army women served as telephone operators for the Signal Corps, navy women enlisted as yeomen, and the first groups of women joined the Marine Corps in July 1918. Approximately twenty-five thousand nurses served in the Army and Navy Nurse Corps for duty stateside and overseas, and about a hundred female physicians were contracted by the army. Neither the female nurses nor the doctors were commissioned as officers in the military, which left the status of professional medical women hovering somewhere between the enlisted and officer ranks. As a result of their undefined status, many female nurses and doctors suffered physical and mental abuses at the hands of their male coworkers with no system of redress in place.

Millions of women also volunteered in civilian organizations such as the American Red Cross, the Young Men’s and Women’s Christian Associations (YMCA/YWCA), and the Salvation Army. Most women met at designated times to roll bandages, prepare and serve meals, package and ship supplies, and organize community fund-raisers. The variety of volunteer opportunities gave women many chances to appear in public spaces and promote charitable activities for the war effort. Female volunteers encouraged entire communities to get involved in war work. While most of these efforts focused on support for the home front, a small percentage of female volunteers served with the American Expeditionary Force in France.

Unfortunately, Jim Crow segregation in both the military and civilian sectors stood as a barrier for black women who wanted to give their time to the war effort. The military prohibited black women from serving as enlisted or appointed medical personnel. Some black women found opportunities to wear a military uniform in the armies of allied nations. A few black female doctors and nurses joined the French Foreign Legion. Black female volunteers faced the same discrimination in civilian wartime organizations. White leaders of the American Red Cross, YMCA/YWCA, and Salvation Army refused to admit black women as equal participants. Black women were allowed to charter auxiliary units in black communities but were given little guidance on organizing volunteers. They turned instead to the community for support and recruited millions of women for auxiliaries that supported the nearly two hundred thousand black soldiers and sailors serving in the military. While most female volunteers labored to care for black families on the home front, three YMCA secretaries worked with the black troops in France.

During the first few years of the war, Americans were generally detached from the events in Europe. Progressive Era reform politics dominated the political landscape, and Americans remained most concerned with the shifting role of government at home. However, the destruction taking place on European battlefields and rising casualty rates exposed the unprecedented brutality of modern warfare. Increasingly, a sense that the fate of the Western world would be decided by the victory or defeat of the Allies took hold in the United States. When he reversed his position and led America into the war, President Wilson articulated a global vision of democracy and promised this would be the “war to end all wars.” In addition to suppressing dissent, Wilson’s administration worked quickly to mobilize the volunteers and draftees needed to fill the ranks of the army and navy, and to cultivate popular support through enormous publicity and propaganda campaigns.

Wilson created the Committee on Public Information, which enlisted the help of Hollywood studios and other media outlets to cultivate a view of the war that pitted democracy against imperialism and framed America as a crusading nation rescuing Western civilization from medievalism and militarism. As the war continued, the government insisted that individual financial contributions made a great difference for the men on the Western Front. Americans lent their financial support to the war effort by purchasing war bonds or supporting the Liberty Loan Drive. President Wilson also told Americans that “Food will win the war.” Naval blockades and low agricultural output had reduced Britain and Europe to severe food rationing. Wishing to send more to its allies, the U. S. government encouraged Americans to plant “Victory Gardens”, preserve their own foods at home, and raise hens in their yards for eggs. A School Garden Army was established to train and support home gardeners. Over five million new gardens produced $1.2 billion in food by the war’s end.

Questions for Discussion

- How do you think the experiences of African Americans in the world war changed their attitudes toward how they were treated in the U.S.?

- What effect do you think women’s contribution to the war effort had on their subsequent struggle for the vote?

Horror of War

In addition to the terror of cowering in trenches waiting to be ordered “over the top” into a “no-man’s land” of machine guns and barbed wire, soldiers in the Great War used poisons such as chlorine and mustard gas on each other. The Germans first used poison gas successfully at the Battle of Ypres in 1915. Although the allies expressed outrage at this violation of 1899 and 1907 international Conventions on Land Warfare, they quickly developed their own gases and followed the German lead. Poison gases were generally heavier than air, so they flowed downhill into trenches. Gases also frequently blew into villages and towns near battlefields, killing up to a quarter million civilians during the course of the war.

The European powers struggled to adapt to the brutality of modern war. Until the spring of 1917, the Allies possessed few effective defensive measures against submarine attacks. German submarines had sunk more than a thousand ships by the time the United States entered the war. The rapid addition of American naval escorts to the British surface fleet and the establishment of a convoy system countered much of the effect of German submarines. Shipping and military losses declined rapidly, just as the American army arrived in Europe in large numbers. Although much of the equipment still needed to make the transatlantic passage, the physical presence of the army proved to a fatal blow to German plans to dominate the Western Front.

In November 1917 Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik party came to power in Russia. Desperate to exit the war so the new Red Army could focus on winning the Russian Civil War (1917-22), and to prevent a German invasion of Russia, Lenin’s government agreed to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany in March 1918. Russia surrendered Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine, losing 34% of its population and most of its industrial base. The treaty also called for territories claimed by the Ottoman Empire to be handed over to Germany’s ally, but Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia declared their independence. Russia also agreed to pay 6 billion marks to compensate Germany for its losses.

In March 1918, Germany tried to take advantage of its new single-front war before the Americans arrived, with the Kaiserschlacht (Spring Offensive), a series of five major attacks. By the middle of July 1918, each and every one had failed to break through the Western Front. Then, on August 8, 1918, two million men of the American Expeditionary Forces joined British and French armies in a series of successful counteroffensives that pushed the disintegrating German lines back across France. The German offensive gamble exhausted Germany’s military, making defeat inevitable. Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated at the request of the German military leaders and a new democratic government agreed to an armistice on November 11, 1918. German military forces withdrew from France and Belgium and returned to a Germany teetering on the brink of chaos.

By the end of the war, more than 4.7 million American men had served in all branches of the military. The United States lost over one hundred thousand men; fifty-three thousand dying in battle, and even more from disease. Their terrible sacrifice, however, paled before the European death toll. After four years of stalemate and brutal trench warfare, France had suffered almost a million and a half military dead and Germany even more. Both nations lost about 4 percent of their populations to the war. And death was not nearly done.

Questions for Discussion

- What effects do you think the trenches and poison gas attacks had on European soldiers and civilians?

- Why did Germany throw so much into the Spring Offensive?

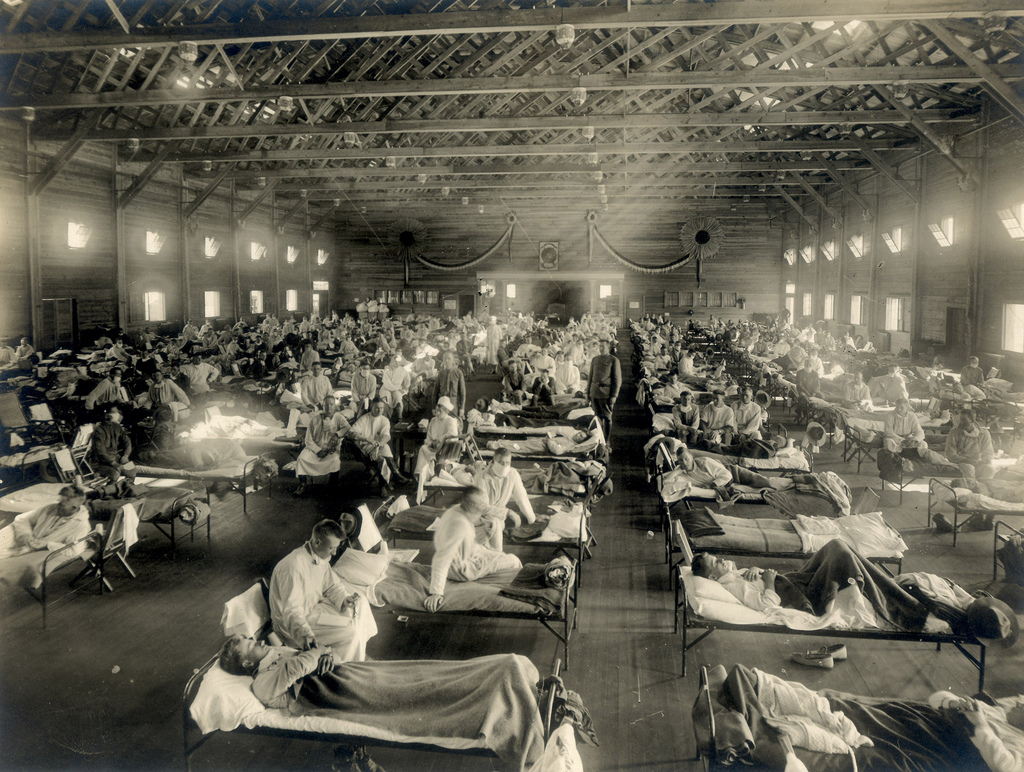

The Influenza Pandemic

Even as war raged on the Western Front, a new deadly threat loomed. In the spring of 1918, a new strain of the influenza virus appeared in the farm country of Kansas and hit nearby Camp Funston, one of the largest army training camps in the nation. The virus spread like wildfire. Between March and May 1918, fourteen of the largest American military training camps reported outbreaks of influenza. Some of the infected soldiers carried the virus on troop transports to France. By September 1918, influenza had spread to all training camps in the United States. And then it mutated. The second wave of the virus was even deadlier than the first. Unlike most flu viruses, the mutant strain struck down those in the prime of their lives rather than old people and young children. A disproportionate number of influenza victims were between ages eighteen and thirty-five. In Europe, influenza hit troops and civilians on both sides of the Western Front. The disease was misnamed “Spanish Influenza,” due to accounts of the disease that first appeared in the uncensored newspapers of neutral Spain while the warring nations tried to suppress the news of disease for propaganda purposes.

The “Spanish Flu” infected about 500 million people worldwide and resulted in the deaths of between fifty and a hundred million people; possibly more. World population in 1918 was about 1.8 billion; influenza infected nearly a third and killed between 5% and 10%. Reports from the surgeon general of the army revealed that while 227,000 American soldiers had been hospitalized from wounds received in battle, almost half a million suffered from influenza. The worst part of the epidemic struck during the height of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in the fall of 1918 and weakened the combat capabilities of both the American and German armies. During the war, more soldiers died from influenza than combat. But the pandemic continued to spread after the armistice, with a death toll of nearly 20% of those infected, as opposed to about 0.1% in regular flu epidemics. Four waves of worldwide infection spread before cases and deaths finally began fading in the early 1920s. No cure was ever found.

Question for Discussion

- Compare the “Spanish Flu” with the current COVID-19 pandemic. What can we learn from the past?

The Fourteen Points and the League of Nations

On December 4, 1918, President Wilson became the first American president to travel overseas during his term. Wilson went to Europe to end “the war to end wars”, and he intended to shape the peace. The war brought an abrupt end to four great European imperial powers. The German, Russian, Austrian-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires each evaporated and the map of Europe was redrawn to accommodate new independent nations. As part of the armistice, Allied forces occupied territories in the Rhineland to prevent Germany from reigniting war. A new German government disarmed while Wilson and other Allied leaders gathered in France at Versailles to dictate the terms of a settlement to the war. After months of deliberation, the Treaty of Versailles officially ended the war.

In January 1918, before American troops had even arrived in Europe, President Wilson had offered an ambitious statement of war aims and peace terms known as the Fourteen Points to a joint session of Congress. The plan not only addressed territorial issues but offered principles on which Wilson believed a long-term peace could be built. The president called for reductions in armaments, freedom of the seas, adjustment of colonial claims, and the abolition of the types of secret treaties that had led to the war. Some members of the international community welcomed Wilson’s idealism, but in January 1918, Germany still anticipated a favorable verdict on the battlefield and did not seriously consider accepting the terms of the Fourteen Points. Even the Allies were dismissive. French prime minister Georges Clemenceau remarked, “The good Lord only had ten [commandments].”

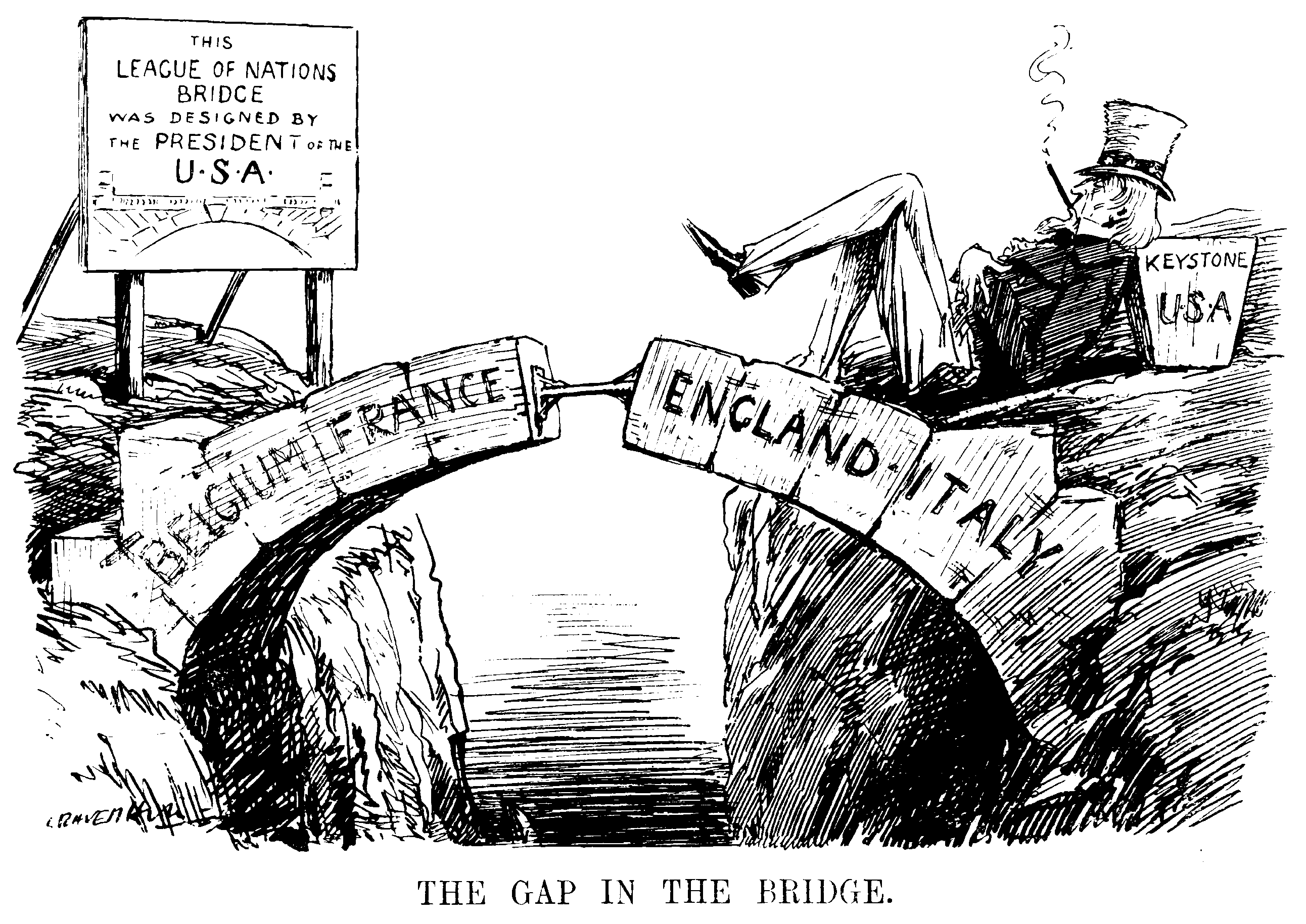

President Wilson continued to promote his vision of the postwar world. The United States entered the fray, Wilson proclaimed, “to make the world safe for democracy.” At the center of the plan was a new international organization, the League of Nations. It would be charged with keeping a worldwide peace, “affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.” This promise of collective security, that an attack on one sovereign member would be viewed as an attack on all, was a key component of the Fourteen Points. Wilson’s Fourteen Points speech was translated into many languages, and was even sent to Germany to encourage negotiation.

But while President Wilson was celebrated in Europe as a “God of Peace,” many of his fellow statesmen were less enthusiastic about his plans for postwar Europe. Former president Theodore Roosevelt called the Fourteen Points “high-sounding and meaningless” and said they could be interpreted to mean “anything or nothing.” And America’s closest allies had little interest in the League of Nations. Allied leaders focused instead on guaranteeing the future safety of their own nations. Unlike the United States, safe across the Atlantic, the Allies had endured the horrors of the war firsthand. They refused to sacrifice further. Negotiations made it clear that British prime minister David Lloyd-George was more interested in preserving Britain’s imperial domain, while French prime minister Clemenceau wanted severe financial reparations and limits on Germany’s future ability to wage war. The fight for a League of Nations was therefore largely on the shoulders of President Wilson.

Despite the Allies’ lack of agreement with the Fourteen Points, the key role of U.S. troops and U.S. dollars in the outcome gave the Americans an influential seat at the negotiating table at Versailles. Woodrow Wilson was seen as an international hero, and his appointee Thomas Lamont became a central figure in the negotiations that ended the war and set guidelines for German reparations that ultimately bankrupted the nation and led to WWII. Wilson’s Fourteen Points have received more attention from historians, but Britain and France were successful getting the punitive items they wanted in the final treaty. Lamont went along because shifting the financial burden to Germany guaranteed that the Allied nations that owed J.P. Morgan and Company so much money would be able to pay it back. By June 1919, the final version of the treaty was signed and President Wilson was able to return home. The treaty was a compromise that included demands for German reparations, provisions for the League of Nations, and the promise of collective security. Wilson didn’t get everything he wanted, but Lamont did. According to historian Ferdinand Lundberg, the “total wartime expenditure of the United States government from April 6, 1917, to October 31, 1919, when the last contingent of troops returned from Europe, was $35,413,000,000. Net corporation profits for the period January 1, 1916, to July, 1921, when wartime industrial activity was finally liquidated, were $38,000,000,000.”

Questions for Discussion

- Do you see any difficulty with the idea that Woodrow Wilson is typically seen by historians as an idealist, but his chief negotiator at Versailles was Thomas Lamont?

- Were Europeans right or wrong to put their national concerns first?

The real fight for the League of Nations was on the American home front. European leaders were more concerned about their nations’ security and sovereignty than about world peace. Wilson was surprised when Americans shared their views. Massachusetts senator Henry Cabot Lodge was the most prominent opponent of the League of Nations. As chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and a Republican Party leader, Lodge attacked the treaty for potentially robbing the United States of its sovereignty. Lodge demanded instead that America must remain free to deal with its problems in its own way, free from the collective security requirements and meddling oversight promised by a League of Nations. Unable to match Lodge’s influence in the Senate, President Wilson tried to take his case to the American people, hoping that ordinary voters could be convinced that the only guarantee of future world peace was the League. During his grueling cross-country trip, however, Wilson suffered an incapacitating stroke in October 1919. Although his family and friends concealed the seriousness of his condition, Wilson never fully recovered and he retired from public life at the end of his term in 1921 and died three years later at age 67. President Wilson’s dream for the League died on the floor of the Senate. Lodge’s opposition successfully blocked America’s entry into the League of Nations. The League began with forty-two members and grew to a peak of fifty-eight in late 1934. But the United States, whose president had championed the League, refused to join, refused to lend it American power, and refused to provide it with the influence needed to fulfill its purpose.

The Great War transformed the world. The Middle East, especially, was drastically changed. Before the war, the Middle East had three main centers of power: the Ottoman Empire, British-controlled Egypt, and Iran. President Wilson’s call for self-determination in the Fourteen Points appealed to many under Ottoman rule. In the aftermath of the war, Wilson sent a commission to determine the conditions and aspirations of the people. The King-Crane Commission found that most favored an independent state free of European control. However, the people’s wishes were largely ignored and the lands of the former Ottoman Empire disintegrated into several nations, many created by European powers with little regard to ethnic realities. These Arab provinces were ruled by Britain and France as “mandates”, and a new nation of Turkey emerged in the former Ottoman heartland in Anatolia. According to the League of Nations, mandates “were inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world.”

Though allegedly established for the benefit of the Middle Eastern people, the mandate system was essentially a reimagined form of nineteenth-century imperialism. France received Syria; Britain took control of Iraq, Palestine, and Transjordan (Jordan). The United States was asked to become a mandate power but declined. The geographical realignment of the Middle East also included the formation of two new Kingdoms of Hejaz and Yemen. The Kingdom of Hejaz only lasted until the 1920s, when it became part of Saudi Arabia. The disposition of the Middle East was complicated by the increasing importance of its oil resources. Oil had been discovered in Iran in 1908, and during the period when it was becoming the most important commodity of the twentieth century it was also becoming clear that some of the world’s largest reserves were located in the Middle East. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (now known as BP) was established in 1908 to control production in Iran. After the war, British-controlled businesses that had been licensed by the Ottomans to develop oil discoveries in Mesopotamia spurred British interest in creating a new Kingdom of Iraq under British mandate in 1920. The British-controlled multinational, TPC (Turkish Petroleum Company, established in 1912), received a 75-year concession to develop Iraq’s oil. A secret deal between Britain and France known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement had set the scene for the partition of the Ottoman Empire in 1916. The fact that the new League of Nations decisions validated the prior secret treaties suggests the League may not have been the new start Wilson had hoped.

Questions for Discussion

- In your opinion, what was the point of the League of Nations? As Wilson had imagined it, who did it benefit?

- Was the United States right or wrong to stay out of the League and refuse to take up mandates?

Racism and Red Scare

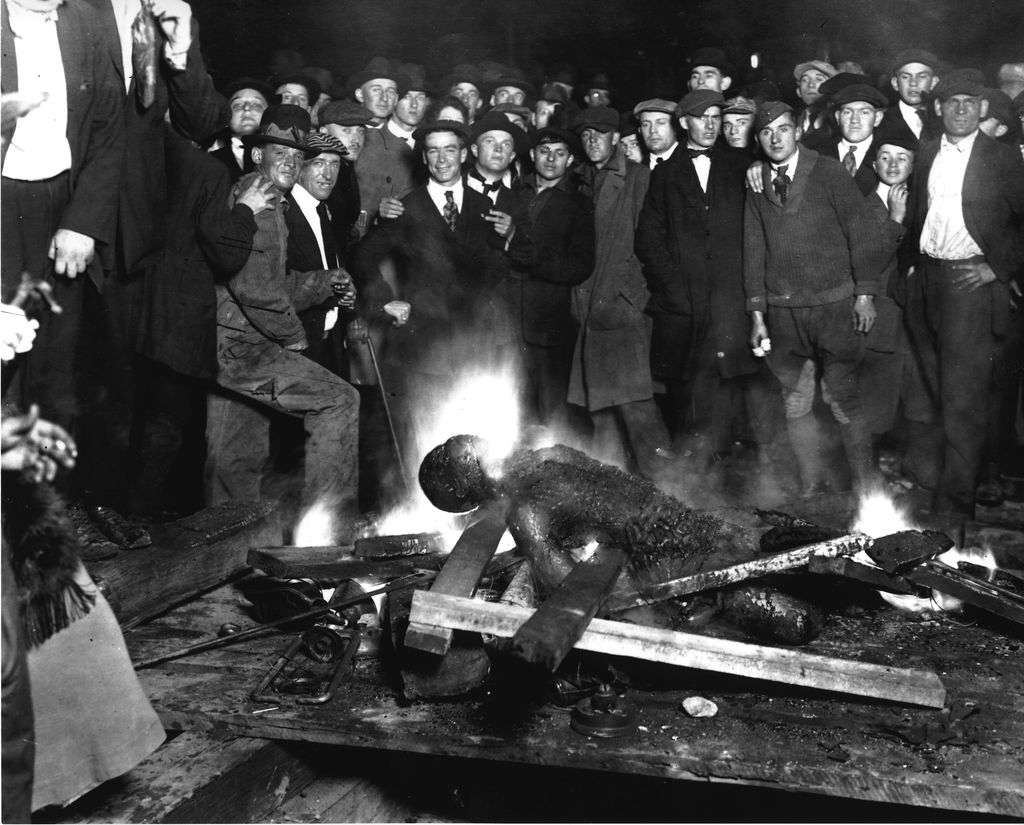

At home, the United States grappled with harsh postwar realities. Racial tensions exploded in the Red Summer of 1919 when violence broke out in at least twenty-five American cities, including Chicago and Washington, D.C. Industrial war production and massive wartime service had created vast labor shortages, and thousands of black southerners had traveled to the North and Midwest to to work in factories. But the Great Migration of black people escaping the traps of southern poverty and Jim Crow sparked new racial conflict when white northerners and returning veterans fought to reclaim their jobs and their neighborhoods from new black migrants. Many black Americans who had fled white supremacy in the South or had traveled halfway around the world to fight for the United States would not so easily accept postwar racism. The overseas experience of black Americans and their return triggered a dramatic change in black communities. W.E.B. Du Bois, who had encouraged blacks to enlist, highlighted black soldiers’ combat experience when he wrote of returning troops, “We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting. Make way for Democracy!” But white Americans just wanted a return to the status quo, a world that did not include social, political, or economic equality for black people. And they were alarmed at the thought of fearless, capable black men who had learned to handle weapons and defend themselves on foreign battlefields.

In 1919, racist riots erupted across the country from April until October. The bloodshed included thousands of injuries, hundreds of deaths, and vast destruction of private and public property across the nation. The weeklong Chicago Riot, from July 27 to August 3, 1919, considered the summer’s worst, included mob violence, murder, and arson. Race riots had rocked the nation before, but the Red Summer was something new. Recently empowered black Americans actively defended their families and homes from hostile white rioters, often with militant force. This behavior galvanized many in black communities, but it also shocked white Americans who interpreted black resistance as a prelude to total revolution. In the riots’ aftermath, James Weldon Johnson wrote, “Can’t they understand that the more Negroes they outrage, the more determined the whole race becomes to secure the full rights and privileges of freemen?” In the fall, an organization called the African Blood Brotherhood formed in northern cities as a permanent “armed resistance” movement. The socialist orientation of its members rapidly led to an affiliation with the Communist Party of America. But the Russian-led Communist International (Comintern) had no interest in semi-independent groups like the ABB with their Afro-Marxist ideas. The Brotherhood’s members found their way to other organizations like the Workers Party of America and the American Negro Labor Congress.

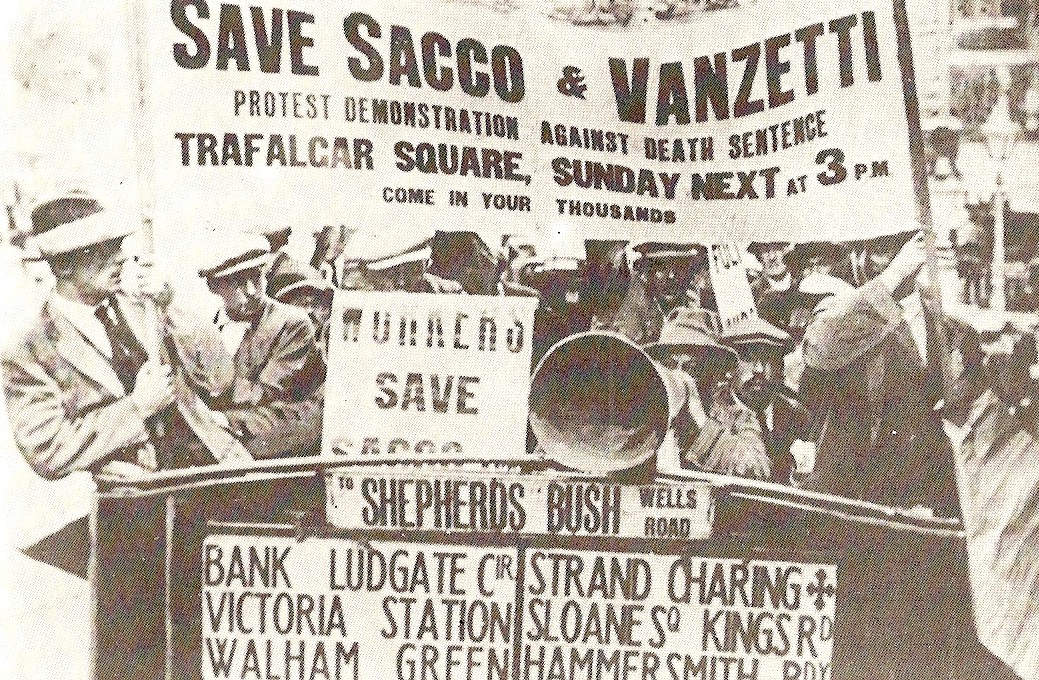

The success of the Russian Revolution further enflamed American fears of communism. The fates of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian-born anarchists convicted of robbery and murder in 1920 epitomized the new American Red Scare. Arrested on suspicion of armed robbery and murder, the trial focused not on the defendants’ guilt or innocence, but on their anarchist political affiliations. They were quickly convicted and sentenced to death, setting off a series of appeals and motions for mistrial. In 1925, while the two men sat on death row, another man confessed to the crime and provided details that made his confession credible. The judge, however, refused a petition for a new trial, later remarking to a Massachusetts lawyer, “Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day?” People all over the world demonstrated their sympathy with the accused. Albert Einstein, George Bernard Shaw, and H.G. Wells signed petitions. Demonstrations were held in London, Paris, Geneva, Amsterdam, and Tokyo. Famous authors wrote about the case, such as John Dos Passos’s Facing the Chair, Maxwell Anderson’s Gods of the Lightning or Upton Sinclair’s Boston. The IWW called a three-day national walkout to protest the executions. Sacco and Vanzetti were executed just after midnight on August 23, 1927. The Sacco-Vanzetti case demonstrated an American paranoia about immigrants and the potential spread of radical ideas, especially those related to international communism. On the 50th anniversary of the executions, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis issued a proclamation that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that “any disgrace should be forever removed from their names”.

Questions for Discussion

- What did the extension of racial conflict into the North after the war suggest about American attitudes regarding race?

- Was the anxiety of the Red Scare justified? Why were Americans so afraid of communism in the early 1920s?

Conclusion

World War I killed millions and profoundly altered the course of world history. Postwar instabilities led directly toward a global depression and a second world war. The war ignited the Bolshevik Revolution, which created the Soviet Union and later the Cold War. Its aftermath saw new Middle Eastern nations and aggravated ethnic tensions that the United States could not overcome. And the United States had fought on the European mainland and had become a major military and economic power. America’s place in the world was never the same. Unfortunately, by whipping up nationalist, racial, and anti-communist passions, American attitudes toward radicalism, dissent, and immigration were poisoned. Postwar disillusionment shattered Americans’ hopes for the progress of the modern world. The war came and went, leaving in its place the bloody wreckage of an old world through which the United States traveled to a new and uncertain future.

Primary Sources

Woodrow Wilson Requests War (April 2, 1917)

In this speech before Congress, President Woodrow Wilson made the case for America’s entry into World War I.

Alan Seeger on World War I (1914; 1916)

The poet Alan Seeger, born in New York and educated at Harvard University, lived among artists and poets in Greenwich Village, New York and Paris, France. When the Great War engulfed Europe, and before the United State entered the fighting, Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion. He would be killed at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. His wartime experiences would anticipate those of his countrymen, a million of whom would be deployed to France. Seeger’s writings were published posthumously. The first selection is excerpted from a letter Seeger wrote to the New York Sun in 1914; the second is from his collection of poems, published in 1916.

The Sedition Act of 1918 (1918)

Passed by Congress in May 1918 and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, the Sedition Act of 1918 amended the Espionage Act of 1917 to include greater limitations on war-time dissent.

Emma Goldman on Patriotism (July 9, 1917)

The Anarchist Emma Goldman was tried for conspiring to violate the Selective Service Act. The following is an excerpt from her speech to the court, in which she explains her views on patriotism.

W.E.B DuBois, “Returning Soldiers” (May, 1919)

In the aftermath of World War I, W.E.B. DuBois urged returning soldiers to continue fighting for democracy at home.

In this 1917 photograph, The Boy Scouts of America charge up Fifth Avenue in New York City in a “Wake Up, America” parade to support recruitment efforts. Nearly 60,000 people attended this single parade.

In this war poster, Uncle Sam points his finger at the viewer and says, “I want you for U.S. Army.” The poster was printed with a blank space to attach the address of the “nearest recruiting station.” Click on the image to view the full poster.

Reference Material

This chapter was written by Dan Allosso, based on The American Yawp chapter 21, which was edited by Paula Fortier, with content contributions by Tizoc Chavez, Zachary W. Dresser, Blake Earle, Morgan Deane, Paula Fortier, Larry A. Grant, Mariah Hepworth, Jun Suk Hyun, and Leah Richier.

Recommended Reading

- Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Coffman, Edward M. The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Cooper, John Milton. Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Dawley, Alan. Changing the World: American Progressives in War and Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Doenecke, Justus D. Nothing Less than War: A New History of America’s Entry into World War I. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

- Freeberg, Ernest. Democracy’s Prisoners: Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

- Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 1975.

- Gerwarth, Robert, and Erez Manela, eds. Empires at War: 1911–1923. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Greenwald, Maurine W. Women, War, and Work: The Impact of World War I on Women Workers in the United States. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1980.

- Hahn, Steven. A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Hawley, Ellis. The Great War and the Search for Modern Order. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979.

- Jensen, Kimberly. Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

- Keene, Jennifer. Doughboys, The Great War, and the Remaking of America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- Kennedy, David. Over Here: The First World War and American Society. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Knock, Thomas J. To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- MacMillan, Margaret. The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. New York: Random House, 2014.

- Manela, Erez. The Wilsonian Movement: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Murphy, Paul. World War I and the Origins of Civil Liberties in the United States. New York: Norton, 1979.

- Neiberg, Michael S. The Path to War: How the First World War Created Modern America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Rosenberg, Emily. Financial Missionaries to the World: The Politics and Culture of Dollar Diplomacy, 1900–1930. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

- Smith, Tony. Why Wilson Matters: The Origin of American Liberal Internationalism and Its Crisis Today. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017.

- Tuttle, William. Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1970.

- Wilkerson, Isabel. The Warmth of Other Sons: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. New York: Vintage Books, 2010.

- Williams, Chad L. Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Media Attributions

- Cheshire_Regiment_trench_Somme_1916 © John Warwick Brooke is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, by Franz von Lenbach © Franz von Lenbach is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Kaiser_Wilhelm_II_of_Germany_-_1902 © T. H. Voigt is licensed under a Public Domain license

- J.P._Morgan_and_J.P._Morgan_Jr © Moody's Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- John_Pershing,_Bain_bw_photo_as_major_general,_1917 © Bain News Service is licensed under a Public Domain license

- La_reprise_de_Douaumont,_le_24_octobre_1916 © Henri Georges Jacques Chartier is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1920px-Thomas_Woodrow_Wilson,_Harris_&_Ewing_bw_photo_portrait,_1919 © Harris & Ewing is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Submarine_U-14_LOC_6358166395 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Boy_Scouts_New_York_City,_1917_NGM-v31-p359 © National Geographic Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Debs_Canton_1918_large © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- King,_Stoddard_WW1_draft_card © Stoddard King is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 369th_15th_New_York is licensed under a Public Domain license

- GraceBanker © Malmstrom Airforce Base is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sow_victory_poster_usgovt © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Nach_Gasangriff_1917 © Hermann Rex is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Map_Treaty_of_Brest-Litovsk-en © United States Military Academy is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Emergency_hospital_during_Influenza_epidemic,_Camp_Funston,_Kansas_-_NCP_1603 © Otis Historical Archives is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- The_Gap_in_the_Bridge © Punch Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ThomasWLamont-1929Timemagazine © Time Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- MPK1-426_Sykes_Picot_Agreement_Map_signed_8_May_1916 © Royal Geographical Society is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Omaha_courthouse_lynching © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Save_Sacco_and_Vanzetti © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license