14 Millennial America

War on Terror

On the morning of September 11, 2001, nineteen young men boarded and then hijacked four passenger planes on the East Coast. They ranged in age from 20 to 33 years old (fourteen were 25 or younger) and came from Egypt (1), Lebanon (1), the United Arab Emirates (2), and Saudi Arabia (15). Their goal was to use the planes, filled with fuel for long-distance flights, as explosive weapons. American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center in New York City at 8:46 a.m. United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower at 9:03. American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the western façade of the Pentagon at 9:37. At 9:59, the South Tower of the World Trade Center collapsed. At 10:03, United Airlines Flight 93 crashed in a field outside Shanksville, Pennsylvania, brought down by passengers who had received news of the earlier hijackings. At 10:28, the North Tower collapsed. In less than two hours, nearly three thousand Americans had been killed.

The attacks stunned Americans. That night, President George W. Bush addressed the nation and assured Americans that “the search is under way for those who are behind these evil acts.” At Ground Zero three days later, Bush thanked first responders for their work. A worker said he couldn’t hear him. “I can hear you,” Bush shouted back, “The rest of the world hears you. And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.” American intelligence agencies quickly identified the Islamic militant group al-Qaeda, led by a wealthy Saudi, Osama bin Laden, as the perpetrators of the attack. Bin Laden had fought in Afghanistan against the Soviet invasion in the 1980s, with U.S. support. After the Soviet withdrawal in 1988-9, bin Laden established al-Qaeda, which was responsible for a 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center and a string of attacks at U.S. embassies and military bases across the world. Bin Laden’s Islamic radicalism and his anti-American aggression attracted supporters across the region and, by 2001, al-Qaeda was active in over sixty countries.

Although during his presidential campaign Bush had denounced intervention in foreign nations, once in office he filled his administration with firm believers in expanding American democracy and American interests abroad. Bush advanced what has become known as a neoconservative policy, which claimed the United States had the right to unilaterally and preemptively make war not only on terrorist organizations, but on any regime that posed a threat to the United States or to U.S. citizens. The “Bush Doctrine” would lead the United States into protracted conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq and entangle the United States in nations across the world. Journalist Dexter Filkins called it a Forever War, a perpetual conflict waged against an amorphous and undefeatable enemy. The geopolitical realities of the twenty-first-century world were forever transformed.

The United States had a history in Afghanistan. When the Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan in December 1979 to quell an insurrection that threatened to topple Kabul’s communist government, the United States and Saudi Arabia had financed and armed anti-Soviet insurgents, the Mujahideen. In 1981, the Reagan administration authorized the CIA to provide the Mujahideen with weapons and training. A wealthy young Saudi, Osama bin Laden, also fought with and funded the Mujahideen. And they began to win. The costs of the war, coupled with growing instability at home, convinced the Soviets to withdraw from Afghanistan in 1989. Osama bin Laden relocated al-Qaeda to Afghanistan after the country was taken over the Taliban in 1996. Under Bill Clinton, the United States launched cruise missiles at al-Qaeda camps in Afghanistan in retaliation for al-Qaeda bombings of American embassies in Africa. After September 11, with a broad authorization to retaliate for the attack on American soil, Bush administration officials made plans for military action against al-Qaeda and the Taliban. What would become the longest war in American history began with the launching of air and missile strikes in October 2001 against targets across Afghanistan. U.S. Special Forces joined with fighters in the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance. The capital, Kabul, fell on November 13. Bin Laden and al-Qaeda operatives retreated into the rugged mountains along the border of Pakistan in eastern Afghanistan. The American occupation of Afghanistan continued.

As American troops struggled to contain the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Bush administration set its sights on Iraq. After the conclusion of the Gulf War in 1991, controlling the oil-rich nation had continued to be an expensive task. America tried economic sanctions, weapons inspections, and no-fly zones. The expense to the United States of maintaining the two no-fly zones over Iraq was roughly $1 billion a year. Related military activities in the region added almost another $500 million to the annual bill. Iraqi authorities, meanwhile, clashed with UN weapons inspectors. In 1998, a standoff between Hussein and the United Nations over weapons inspections led President Clinton to launch punitive strikes aimed at debilitating what was thought to be a developed chemical weapons program. Cruise missiles fired from U.S. Navy warships and Air Force B-52 bombers targeted suspected chemical weapons storage facilities, missile batteries, and command centers. Airstrikes continued for four days, unleashing in total 415 cruise missiles and 600 bombs against 97 targets. The number of bombs dropped was nearly double the number used in the 1991 conflict. The timing of the strikes coincided with the Congressional vote to impeach Clinton in December 1998, leading some critics to suggest it was a distraction. It’s not known how many people were killed in the 1998 bombing. A couple of years earlier, when Clinton’s secretary of state, Madeline Albright, had been asked by an interviewer to comment on reports that up to a half million Iraqi children had been killed by US sanctions, she had replied, “This is a very hard choice, but we think the price is worth it.”

The conflict between the United States and Iraq continued through the 1990s and into the early 2000s, when Bush administration officials began championing “regime change.” Bush publicly denounced Saddam Hussein’s regime claimed he had resumed producing weapons of mass destruction. His advisors began pushing for war in the fall of 2002, alleging that Hussein was trying to acquire uranium and had aluminum tubes used for nuclear centrifuges. To stoke public alarm, George W. Bush said in October, “Facing clear evidence of peril, we cannot wait for the final proof—the smoking gun—that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud.” Protests broke out across the country and all over the world, but most Americans believed the administration’s claims and supported military action. On October 16, Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq resolution, giving Bush the power to make war in Iraq. To avoid an invasion, Iraq began cooperating with UN weapons inspectors in late 2002, but the Bush administration pressed on. On February 6, 2003, Secretary of State Colin Powell, who had risen to public prominence as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of State during the Gulf War in 1991, presented allegations of a robust Iraqi weapons program to the UN. Although he told the UN he was presenting just the facts, according to Powell’s chief of staff, he was secretly concerned about “how we’ll all feel if we put half a million troops in Iraq and march from one end of the country to the other and find nothing.”

The first American bombs hit Baghdad on March 19, 2003, in a three-day bombing campaign designed to produce “shock and awe” in the targeted population. Several hundred thousand troops moved into Iraq and Hussein’s regime quickly collapsed. Baghdad fell on April 9. On May 1, 2003, aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln, beneath a banner reading Mission Accomplished, George W. Bush announced that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended.” No evidence of weapons of mass destruction were ever found. And combat operations had not really ended. The Iraqi insurgency had begun, and the United States would spend the next ten years struggling to contain it. Efforts by various intelligence gathering agencies led to the capture of Saddam Hussein, who was found hiding in an underground bunker near his hometown in December 2003. The new Iraqi government found him guilty of crimes against humanity and he was hanged on December 30, 2006.

The ongoing “War on Terror” was a centerpiece in the race for the White House in 2004. Massachusetts senator John F. Kerry, a Vietnam War veteran known for his subsequent testimony against the war, attacked Bush for his inability to contain the Iraqi insurgency or to find weapons of mass destruction. Democrats also seized on photographic evidence that American soldiers had abused prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison outside Baghdad and criticized the administration’s inability to find Osama bin Laden. Many enemy combatants who had been captured in Iraq and Afghanistan were “detained” indefinitely at a military prison in Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. “Gitmo” became infamous for its harsh treatment, indefinite detentions, and torture of prisoners. Bush defended the War on Terror and his allies accused critics of failing to “support the troops.” Worse, along with twenty-eight of his fellow Democratic senators, Kerry had voted for the war. Although many later said they had been misled by the administration, Kerry and the Democrats were attacking a war they had authorized. Bush won a close but clear victory.

Katrina

During the second Bush term the continued deterioration of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and increasing evidence that the administration had lied about weapons of mass destruction tarnished the administration’s image, although Republicans retained control of the House and Senate. Bush’s presidency would take a bigger hit from his failure to respond to the domestic tragedy that followed Hurricane Katrina’s devastating hit on the Gulf Coast. New Orleans suffered a direct hit, the levees broke, and the city flooded. Thousands of refugees flocked to the Superdome, where supplies and medical treatment and evacuation were slow to come. Individuals died in the heat, waiting for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to arrive with aid. Bodies rotted and floated in flood-waters. Americans watched TV news reports of poor black Americans abandoned. Katrina became a symbol of a broken administrative system, a devastated coastline, and social inequality that allowed escape and recovery for some and not for others. Critics charged that Bush had staffed his administration with incompetent political supporters and had further ignored the displaced poor and black residents of New Orleans.

Afghanistan and Iraq, meanwhile, continued to deteriorate. In 2006, the Taliban reemerged as the US-supported Afghan government proved corrupt and incapable of providing social services or security for its citizens. Iraq descended further into chaos as insurgents battled against American troops and al-Qaeda in Iraq bombed civilians and released video recordings of beheadings. In 2007, twenty-seven thousand additional U.S. forces were deployed to Iraq to provide cover for the withdrawal of American forces. In December 2008, the Iraqi government approved the U.S.-Iraq Status of Forces Agreement, and U.S. combat forces began withdrawing from Iraqi cities in 2009. The last U.S. combat forces left Iraq on December 18, 2011. Violence and instability continued to rock the country.

Great Recession and Obama

Like most American economic catastrophes, the Great Recession began when a speculative bubble burst. Throughout the 1990s and into the new millennium, home prices climbed steadily and financial services firms looked to cash in on what seemed to be a safe and lucrative investment. But as more and more homes sold each year, mortgage companies began writing increasingly risky loans and then bundling them together and selling them as securities, sometimes so quickly that it became difficult to determine exactly who owned what. Decades of financial deregulation had rolled back Depression-era restrictions like the Glass-Steagall Act that had separated commercial and investment banks, and new laws like the Commodity Futures Modernization Act exempted credit-default swaps, the key financial instrument behind the crash, from regulation.

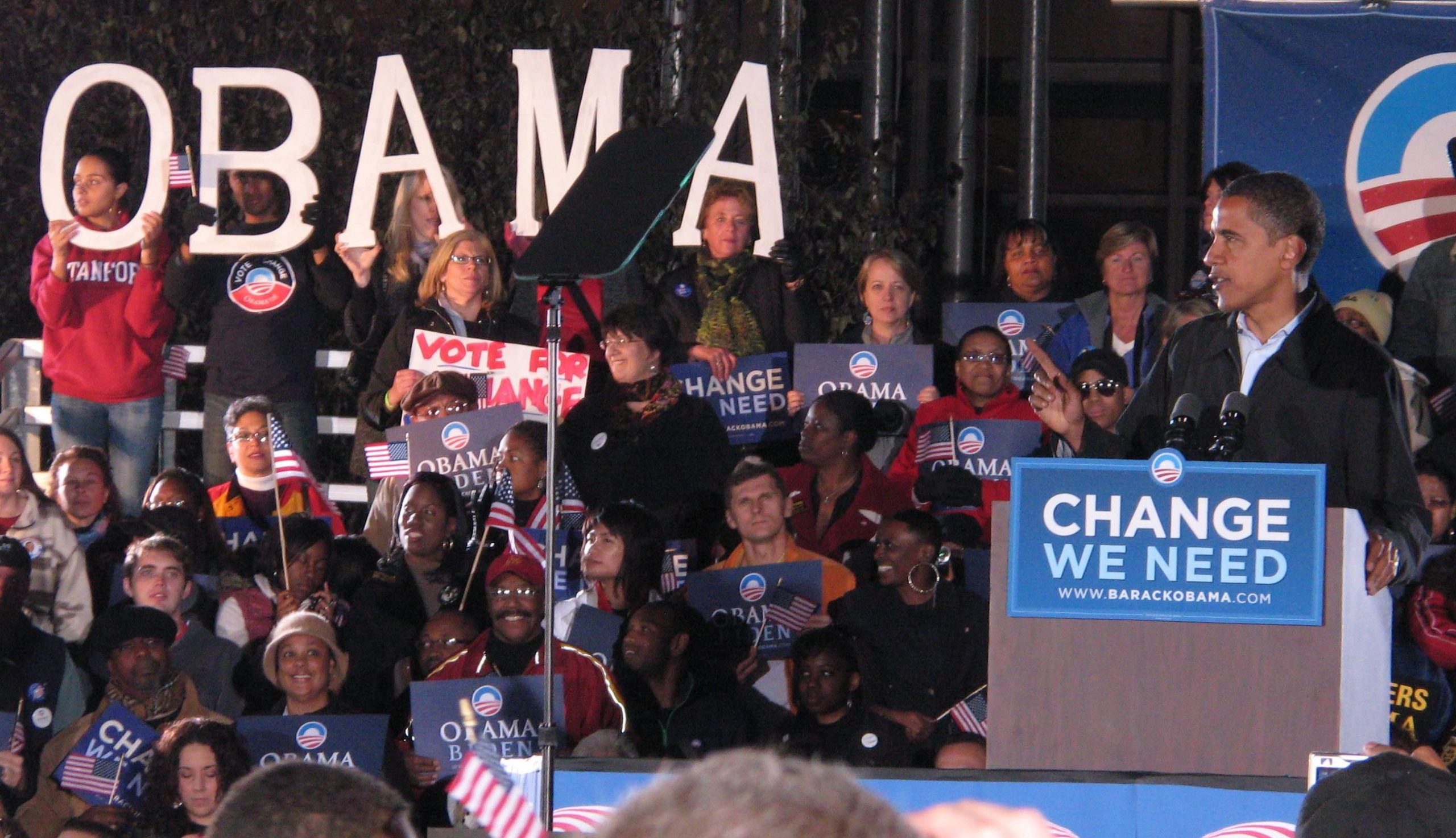

When the supply of new houses started to exceed demand and prices began to fall, many homeowners and real estate speculators began defaulting on their mortgages. These debts, even the lower-quality, “subprime” mortgages, had been bundled into securities and sold to investors as safe investments. Mortgage-backed securities that had been given very high marks by rating agencies turned out to be junk, and the whole system collapsed. Major financial services firms such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers went bankrupt and disappeared almost overnight. In order to prevent the crisis from spreading, the federal government poured billions of dollars into the industry, propping up hobbled banks. The crisis, which began under Bush, continued under Barack Obama. As a senator, Obama had opposed the Iraq War and the troop surge while his opponent, John McCain, had voted for them. Obama was also the mixed-race son of a white American mother and an African father, and was twenty-five years younger than McCain. His campaign promised “Change We Can Believe In,” and millions of voters believed him and carried the Democrats to a victory that included the White House and both branches of Congress. Obama’s campaign outspent McCain’s two to one, paying over three-quarters of a billion dollars for the win.

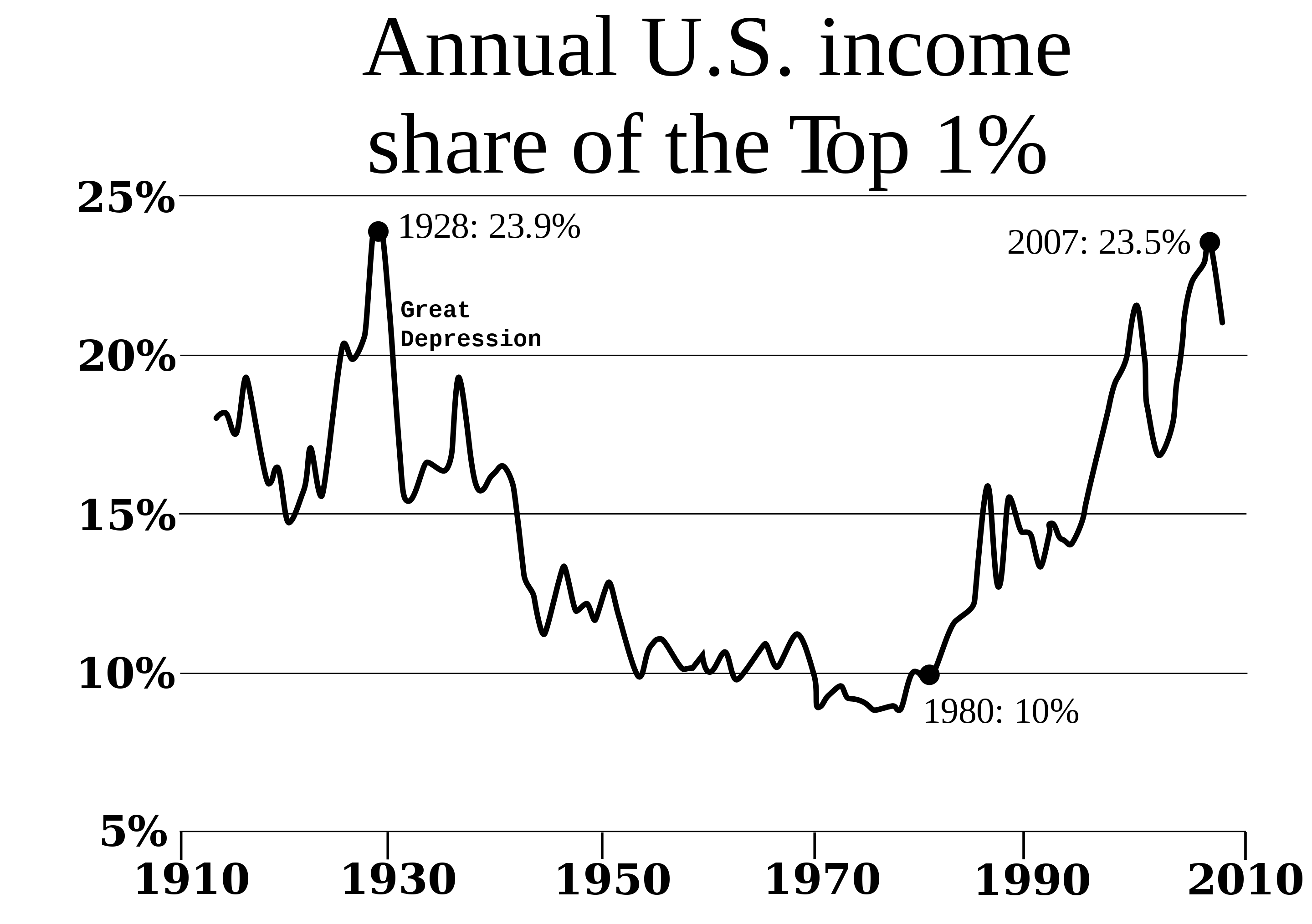

This was an unprecedented level of political spending: 2000 election spending had been about $650 million and in the 2004 election both candidates had spent a total of about $1 billion. In order to raise that money, Obama had made a lot of alliances and promises that were not that conducive to the change he had promised. Even before his inauguration, Obama began putting together a team to address the ongoing financial crisis. His appointees were Wall Street insiders; many had been at least partly responsible for the problem they were supposed to solve. Government bailouts of “too big to fail” corporations and massive giveaways to bankers created shock waves of resentment throughout the rest of the country. On the right, conservative members of the Tea Party attacked the cronyism of an Obama administration filled with former Wall Street executives. The same energies also motivated the Occupy Wall Street movement, as young, left-leaning New Yorkers protested an American economy that seemed overwhelmingly tilted toward “the one percent.”

The Great Recession accelerated the income and wealth inequalities populists on the left and right opposed. A study from the Congressional Budget Office found that since the late 1970s, after-tax income of the wealthiest 1 percent had grown by over 300 percent. The “average” American’s after-tax income had grown only 35 percent in thirty years; or slower than inflation. Economic trends and government policy had disproportionately benefited the wealthiest Americans for decades. But despite some political rhetoric, American frustration failed to generate anything like the social unrest of the early twentieth century. A weakened labor movement and a strong conservative bloc continued to stymie serious attempts at reversing or even slowing economic inequalities. Occupy Wall Street managed to generate a fair number of headlines and shift public discussion away from budget cuts and toward inequality, but its presence on the public stage was fleeting.

The Great Recession, however, was not. While bailed-out American banks quickly recovered and resumed their steady profits, and while the stock market climbed to new heights, American workers continued to lag. Job growth was slow and unemployment rates remained stubbornly high for years. Wages froze and well-paying full-time jobs that had been lost were too often replaced by low-paying, part-time work. A multi-job, less-than-full-time “gig” economy began to replace the previous economy where most people had earned a living at a single job. A generation of workers coming of age within the crisis, moreover, had been savaged by the economic collapse. Unemployment among young Americans hovered for years at rates nearly double the national average.

The economy continued its halfhearted recovery from the Great Recession. Obama campaigned for reelection on little to specifically address the crisis and, faced with congressional resistance as House and then Senate majorities were won by Republicans, accomplished even less. While corporate profits soared and stock markets rose steadily, wages stagnated and employment sagged for years after the Great Recession. By 2016, the average American worker had not received a pay-raise in almost forty years. The average worker in January 1973 had earned $4.03 an hour. Adjusted for inflation, that wage was about two dollars per hour more than the average American earned in 2014. Working Americans were losing ground. Most income gains in the economy had been captured by a small number of wealthy earners. Between 2009 and 2013, 85 percent of all new income in the United States went to the top 1 percent of the population.

But if money no longer flowed to American workers, it saturated American politics. In 2000, George W. Bush raised a record $172 million for his campaign. In 2008, Barack Obama became the first presidential candidate to decline public funds, removing any legal caps to his total fund-raising. Obama raised and spent nearly three quarters of a billion dollars for his campaign. Winning the average House seat, meanwhile, cost about $1.6 million and the average Senate Seat over $10 million. In 2002, Senators John McCain and Russ Feingold had crossed party lines to pass the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, bolstering campaign finance laws passed in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal in the 1970s. But political organizations exploited loopholes to raise large sums of money and, in 2010, the Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United v. FEC that no limits could be placed on political spending by corporations, unions, and nonprofits. Money flowed even deeper into politics.

Climate Crisis

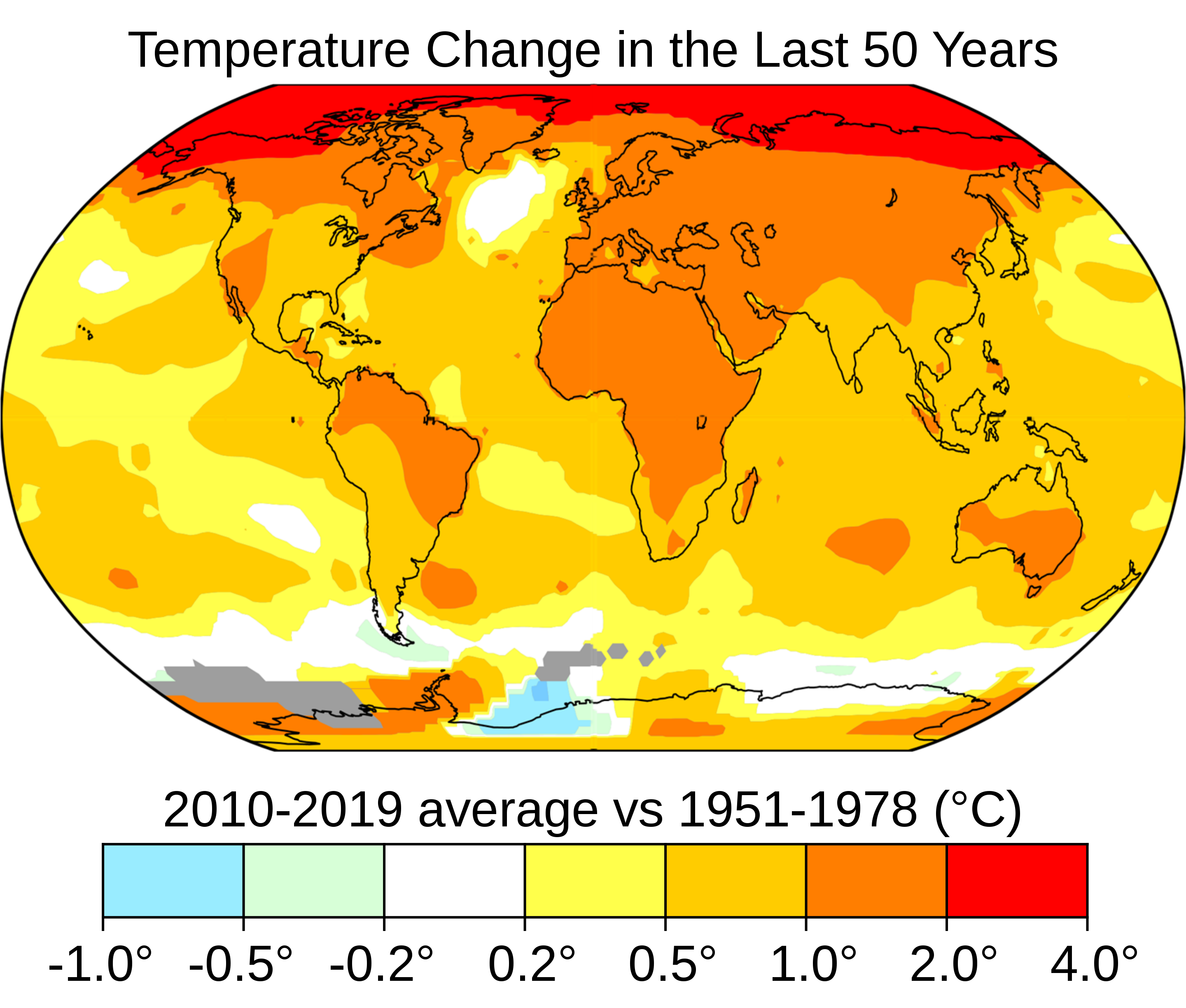

A lot of the money entering politics was focused on changing public opinion. Climate change, more than any other environmental concern, has dominated the attention of Americans in recent years (and has in many cases pushed pollution off the table, which is unfortunate). Although the idea that the planet’s climate has been adversely affected by human activity is very controversial in the media, politics, and popular culture, it is almost universally accepted by scientists. According to NASA, at least 97% of climate scientists agree that global warming over the past couple of centuries is due to human activities, or anthropogenic. American and international science organizations like the American Geophysical Union, the American Meteorological Society, and the American Medical Association, in addition to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, have all gone a step further, saying in the words of the American Physical Society, “We must reduce emissions of greenhouse gases beginning now.”

Of course who they mean by “we” is unclear, and the penalties for heeding their warnings are really hard to specify. The science is complicated and it is difficult for some people to understand. And to make matters worse, most Americans share a belief system that distrusts science and scientists, because science seems to contradict their most cherished religious doctrines about the nature of the world and their place in it. To make matters even worse, concern over climate change has been identified with a particular political orientation. The claim that only liberals care about the environment is not only absurd, but it ignores the traditional meaning of the word conservative. In reality, this is not a liberal vs. conservative issue. The argument against climate change has been carefully managed and funded by political action committees and foundations representing corporations that oppose changes in energy policy.

Although 97% of climate scientists agree on anthropogenic climate change, when Americans are asked, “Do most scientists believe that the Earth is getting warmer because of human activity?” 55% say either “No” or that they don’t know. Less than half of Americans are aware that scientists are basically unanimous on this issue, and thinking that scientists are unsure affects their own opinions about climate change and the the government policies they are willing to support to mitigate it. A recent study found that most of the public statements against climate change made from 2003 to 2010 could be traced to about 91 organizations which received $558,000,000 in grants during that period. From 2003 to 2007 this money was easily traceable to sources such as Exxon-Mobil and Koch Industries, two corporations opposed to changes in energy policy. With the changes in foundation funding that followed in the wake of the 2008 Citizens United Supreme Court decision that allowed corporations to hide their political spending, the sources of money funding climate change denial have been more difficult to trace. Climate deniers warn of the “command economies” they claim environmentalists wish to impose, using language designed to rile up libertarians and free market enthusiasts and mobilize them against changing the economy in ways that although bad for oil companies, would almost certainly create millions of new jobs.

New Horizons

Americans looked anxiously to the future and especially to millennials, the new generation that became adults in the first years of the 21st century. Pollsters focused on features that distinguish millennials from older Americans: millennials, the pollsters said, were more diverse, more liberal, less religious, and wracked by economic insecurity. While liberal social attitudes marked the younger generation, perhaps nothing defined young Americans more than the embrace of technology. The internet in particular, liberated from desktop modems, shaped more of daily life than ever before. The Apple iPhone in 2007 popularized the concept of smartphones for millions of consumers and, by 2011, about a third of Americans owned a mobile computing device. Four years later, two thirds did. And with the advent of social media, Americans used their phones and computers to stay in touch with family, chat with friends, share photos, and interpret the world. As newspaper and magazine subscriptions dwindled, Americans increasingly turned to their social media networks for news and information. Ambitious new online media giants, hungry for clicks and the ad revenue they represented, churned out provocatively titled, easy-to-digest stories that could be linked and tweeted and shared widely among like-minded online communities. Even traditional media companies, to offset shrinking revenues, used clickbait to appeal to their new online consumers.

The ability of individuals to share stories through social media apps revolutionized the media landscape and reshaped political debates. The easy accessibility of video capturing and the ability for stories to go viral outside traditional media, for instance, brought new attention to the tense and often violent relations between municipal police officers and African Americans. The 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, focused the issue and helped spawn the hashtag movement, #blacklivesmatter. But social media algorithms, code that chooses content for users’ newsfeeds based on what will be most engaging, began to create separate communities that see the world quite differently. In 2012 activist Eli Pariser warned Americans that they were trapped in “filter bubbles” where not only opinion but also often the facts people saw were being skewed to maximize their attention rather than to accurately represent reality. This has resulted in a breakdown of the shared consensus that has been an important element of American society. Where there was once an anchorman considered to be America’s most trusted man, there are now a nearly infinite number of competing voices. The ability technology gives nearly everybody to produce high quality content can make it very difficult to distinguish between reliable and unreliable sources. The age, size, or apparent audience of a source is also not an indicator, as large, wealthy networks have drifted into increasingly narrow niches that often seem to border on propaganda. The passage of time will probably help us distinguish the truth from the conspiracy theories. In the meantime, we’ll need to be particularly careful to critically examine the news and opinions we encounter.

Conclusion

The attacks of September 11, 2001, plunged the United States into a new series of seemingly interminable conflicts around the world. At home, economic recession, a slow recovery, stagnant wage growth, and general pessimism infected American life as contentious politics and cultural divisions poisoned social harmony. And yet the stream of history continues flowing. Trends shift, things change, and events turn. New generations bring new perspectives and share new ideas with new technologies. Our world is not inevitable. It is the product of choices people made in the past, leading to the choices before us today that lead to the future. Although it is difficult to sift through the barrage of signals and noise around us each day, I hope the historical perspectives you’ve been exposed to in this text will be useful to you as you evaluate whatever tomorrow brings and decide what you’re going to do about it.

Sources

9/11 Commission Report, “Reflecting On A Generational Challenge” (2004)

On July 22, 2004, the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States—or, the 9/11 Commission—delivered a 500-plus-page report that investigated the origins of the 9/11 attacks and America’s response and offered policy prescriptions for a post-9/11 world.

George W. Bush on the Post-9/11 World (2002)

In his 2002 State of the Union Address, George W. Bush proclaimed that the attacks of September 11 signaled a new, dangerous world that demanded American interventions. Bush identified an “Axis of Evil” and provided a justification for a broad “war on terror.”

In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that prohibitions against same-sex marriage were unconstitutional. Gay marriage had been a divisive issue in American politics for well over a decade. Many states passed referendums and constitutional amendments barring same-sex marriages and, in 1996, Bill Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act, defining marriage at the federal level as between a man and a woman. In 2003, the Massachusetts Supreme Court struck down Massachusetts’ state’s prohibition, making it the first state to legally marry same-sex couples. More followed and public opinion began to turn. Although President Obama still refused to support it, by 2011 a majority of Americans believed same-sex marriages should be legally recognized. Four years later, the Supreme Court issued its Obergefell decision. The majority opinion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, considered the relationship between history and shifting notions of liberty and injustice.

Barack Obama, Howard University Commencement Address (2016)

In 2016, President Barack Obama delivered the commencement address at Howard University, the nation’s most distinguished historically black university. In it, he urged students to be hardworking yet pragmatic in their quest to achieve “justice and equality and freedom” in American life.

Chelsea Manning Petitions for a Pardon (2013)

Chelsea Manning, a U.S. Army intelligence analyst, was convicted in 2013 for violating the Espionage Act by leaking classified documents revealing the killing of civilians, the torture of prisoners, and other nefarious actions committed by the United States in the War on Terror. After being sentenced to thirty-five years in federal prison, she delivered a statement, through her attorney, explaining her actions and requesting a pardon from President Barack Obama. Manning’s sentence was commuted in 2017.

A worker stands in front of rubble from the World Trade Center at Ground Zero in Lower Manhattan several weeks after the September 11 attacks.

Barack Obama and a Young Boy (2009)

In 2008, Barack Obama became the first African American elected to the presidency. In this official White House photo from May, 2009, 5-year-old Jacob Philadelphia said, “I want to know if my hair is just like yours.”

This chapter was written by Dan Allosso, partially adapting content from Chapter 30 of The American Yawp and incorporating original content. The original Yawp chapter was edited by Michael Hammond, with content contributions by Eladio Bobadilla, Andrew Chadwick, Zach Fredman, Leif Fredrickson, Michael Hammond, Richara Hayward, Joseph Locke, Mark Kukis, Shaul Mitelpunkt, Michelle Reeves, Elizabeth Skilton, Bill Speer, and Ben Wright.

Recommended Reading

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press, 2012.

- Canaday, Margot. The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Carter, Dan T. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963–1994. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1996.

- Cowie, Jefferson. Capital Moves: RCA’s 70-Year Quest for Cheap Labor. New York: New Press, 2001.

- Ehrenreich, Barbara. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. New York: Metropolitan, 2001.

- Evans, Sara. Tidal Wave: How Women Changed America at Century’s End. New York: Free Press, 2003.

- Gardner, Lloyd C. The Long Road to Baghdad: A History of U.S. Foreign Policy from the 1970s to the Present. New York: Free Press, 2008.

- Hinton, Elizabeth. From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Hollinger, David. Postethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

- Hunter, James D. Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

- Meyerowitz, Joanne. How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Mittelstadt, Jennifer. The Rise of the Military Welfare State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Moreton, Bethany. To Serve God and Walmart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Nadasen, Premilla. Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Osnos, Evan. Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth and Faith in the New China. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014.

- Packer, George. The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

- Patterson, James T. Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Translated from the French by Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2013.

- Ricks, Thomas E. Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq. New York: Penguin, 2006.

- Schlosser, Eric. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001.

- Stiglitz, Joseph. Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. New York: Norton, 2010.

- Taylor, Paul. The Next America: Boomers, Millennials, and the Looming Generational Showdown. New York: Public Affairs, 2014.

- Wilentz, Sean. The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008. New York: HarperCollins, 2008.

- Williams, Daniel K. God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Wright, Lawrence. The Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Knopf, 2006.

Media Attributions

- Operation Noble Eagle © Jim Watson is licensed under a Public Domain license

- US_10th_Mountain_Division_soldiers_in_Afghanistan © Staff Sgt. Kyle Davis is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Desert_fox_missile © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Colin_Powell_anthrax_vial._5_Feb_2003_at_the_UN © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Camp_Delta,_Guantanamo_Bay,_Cuba © Kathleen T. Rhem is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 050830-C-3721C-032 © NyxoLyno Cangemi is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 20081102_Obama-Springsteen_Rally_in_Cleveland © TonyTheTiger is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- We_Are_The_99% © Paul Stein is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 2880px-2008_Top1percentUSA.svg © RoyBoy is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 2880px-Change_in_Average_Temperature.svg © NASA is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Solar_panels_on_house_roof © Gray Watson is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 2880px-Eli_Pariser,_author_of_The_Filter_Bubble_-_Flickr_-_Knight_Foundation_(1) © Knight Foundation is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license