11 Unraveling and Malaise

-

The Great Society

Although Lyndon Johnson was fifty-four years old when he became president, or just nine years older than President Kennedy who he replaced, he seemed like a member of an older generation. This was because he was a member of an older political generation. John F. Kennedy had entered politics as a Congressperson in 1947 after serving in World War II. Johnson had been in Washington since 1931, first as legislative secretary to a Texas representative and then in 1937 as a Congressperson himself. Johnson was already in Washington when Franklin Roosevelt arrived; he became an ally of the new Democratic president and an ardent supporter of Roosevelt’s New Deal. President Lyndon Johnson, a white southerner with a thick Texas drawl and an understanding of Washington developed over eighteen years spent in the House and another dozen in the Senate, embraced the civil rights movement. Johnson had already managed passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960 as Senate Majority Leader. He took up Kennedy’s stalled 1963 civil rights bill, strengthened it, and navigated it through Congress. The following summer he signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, one of the most important pieces of civil rights legislation in American history. The comprehensive act barred segregation in public accommodations and outlawed discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, and national or religious origin.

The civil rights movement created space for political leaders to pass legislation, and the movement continued pushing forward. Direct action continued through the summer of 1964, as student-run organizations like SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality began the Freedom Summer drive in Mississippi, registering African American voters in a state with an ugly history of discrimination. In March 1965, activists attempted a march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to support local African American voting rights. A few weeks earlier, a twenty-six-year-old black man named Jimmie Lee Jackson had been shot by state troopers during a voting-rights demonstration when he tried to protect his mother from police who were beating her. On March 7, “Bloody Sunday,” civil rights leaders including John Lewis, the twenty-five-year-old SNCC leader, planned a 54-mile march from Selma to Montgomery, where Governor George Wallace continued to lead the opposition to civil and voting rights. As they left Selma, the marchers were attacked on the Edmund Pettus Bridge by white law enforcement with batons and tear gas. Television cameras captured the brutal beatings and tear gas attacks on peaceful marchers, and cheering white crowds waving Confederate battle flags. Film was flown to New York, where ABC News interrupted the network’s broadcast of “Judgment at Nuremberg” with a special report on the violence. Fifty million Americans watching a star-studded courtroom drama about Nazi atrocities instead watched uniformed Americans behaving like German storm troopers, following orders to brutalize their fellow Americans. Pulitzer Prize-winning authors Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, who chronicled the Civil Rights movement in The Race Beat, wrote that “the juxtaposition struck like psychological lightning in American homes.” Coverage of the march prompted President Johnson to present the bill that became the Voting Rights Act of 1965, abolishing voting discrimination in federal, state, and local elections.

On a May morning in 1964, speaking to graduates of the University of Michigan, President Johnson laid out a sweeping vision for a package of domestic reforms known as the Great Society. Johnson called for “an end to poverty and racial injustice” and challenged Americans to “enrich and elevate our national life, and to advance the quality of our American civilization.” The Great Society’s legislation was breathtaking in scope, and many of its programs and agencies are still with us today. In addition to civil rights, the Great Society took on a range of quality-of-life concerns that seemed suddenly solvable in a society of such affluence. It established the first federal food stamp program. Medicare and Medicaid ensured access to quality medical care. In 1965, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act was the first significant federal investment in public education, totaling more than $1 billion. The Great Society also established the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, and created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Johnson’s domestic agenda largely focused on the $3 billion allocated for War on Poverty programming within the Great Society’s Economic Opportunity Act (EOA) of 1964. No EOA program was more controversial than Community Action, the cornerstone antipoverty program. Community Action Programs would give disfranchised Americans a seat at the table in planning and executing federally funded programs. Despite widespread support for most Great Society programs, the War on Poverty increasingly became the focal point of domestic criticism. As racial unrest and violence swept across urban centers, critics from the right lambasted federal spending for “unworthy” citizens. The Civil Rights Acts, the Voting Rights Acts, and the War on Poverty provoked conservative resistance and were catalysts for the rise of Republicans in the South and West. However, subsequent presidents and Congresses have left intact the bulk of the Great Society, including Medicare and Medicaid, food stamps, federal spending for arts and literature, and Head Start. Even Community Action Programs inspired a new generation of community activists who had never before felt, as one put it, that “this government is with us.”

Questions for Discussion

- Why did the public react so strongly to the “Bloody Sunday” incident in Selma?

- What made President Johnson an effective executive?

2. Vietnam War Begins

American involvement in the Vietnam War began during the postwar period of decolonization. The Soviet Union backed many nationalist movements across the globe, but the United States feared the expansion of communist influence and pledged to confront any revolutions that seemed to attack Western capitalism. But it was often difficult to know when a revolutionary movement opposed capitalism or just western imperialism. American foreign policy was guided by the Domino Theory, the idea that if a country fell to communism, neighboring states would soon follow. After the communist takeover of China in 1949, the United States supported the French empire’s effort to retain control over its colonies in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos; largely because the leaders of the revolution had ties to communism.

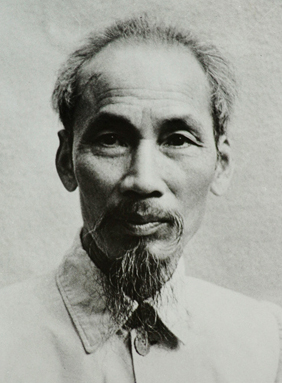

In 1945, a Vietnamese revolutionary named Ho Chi Minh issued a Declaration of Independence for the region that had been known as French Indochina, based on the American Declaration of 1776. Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969), who had embraced Marxism while living in Europe in the 1920s, had led the resistance to Japanese occupation during the war years. His Declaration began by quoting the famous American statement that “All men are created equal. They are endowed with their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” Between 1946 and 1954, France fought a counterinsurgency campaign against nationalist Viet Minh forces led by Ho Chi Minh. The United States assisted the French with funds, arms, and advisors, but it was not enough.In 1954, Viet Minh forces defeated the French army at Dien Bien Phu. A peace conference in Geneva temporarily divided Vietnam into two separate states until UN-monitored elections could be held. But the United States was aware that Ho Chi Minh was almost certain to be elected president of the new nation and blocked the elections. The temporary partition became permanent. The United States established the Republic of Vietnam, or South Vietnam, and installed a prime minister, Ngo Dinh Diem, known to be friendly to United States interests.

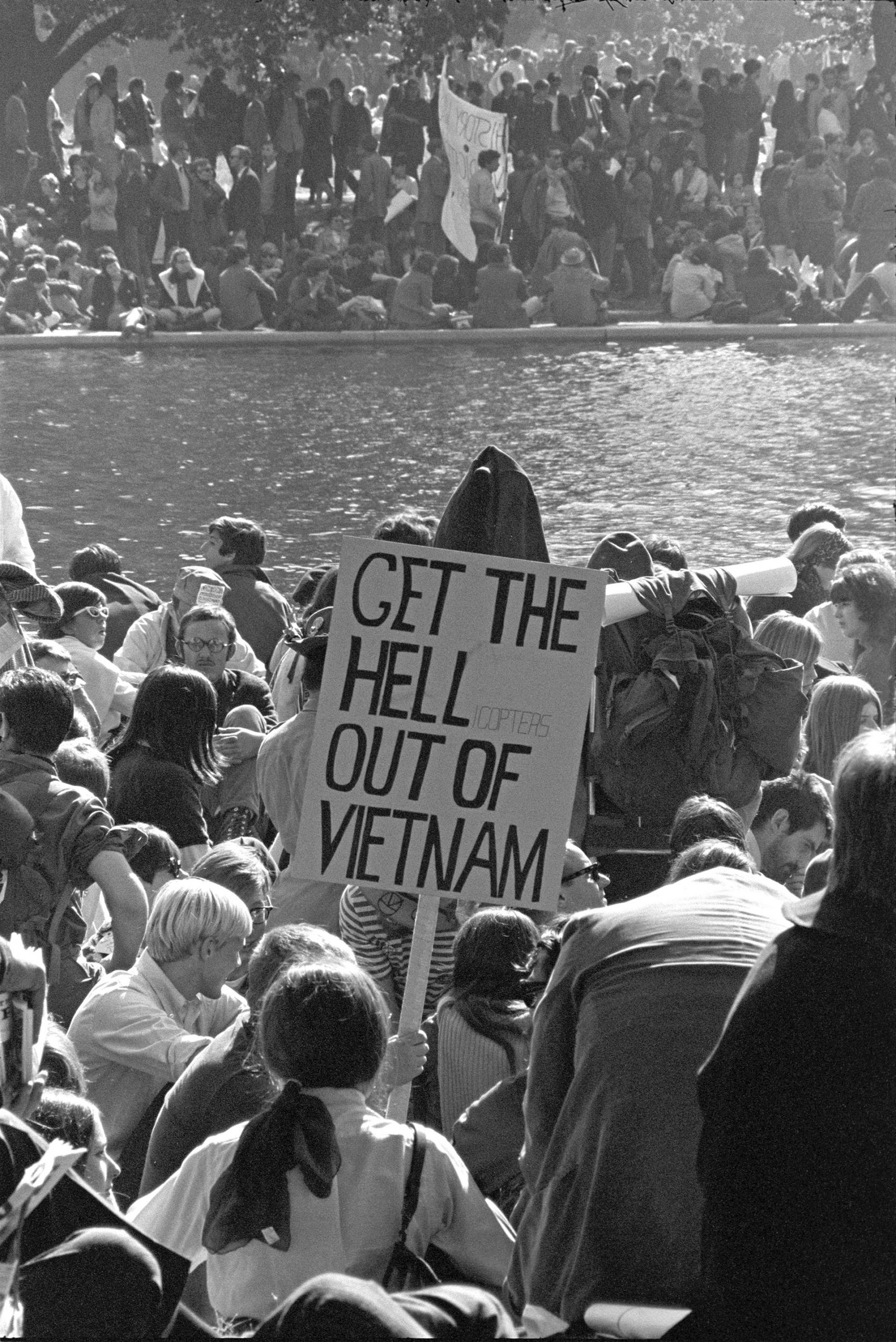

Diem’s government, however, lacked popular support and could not contain the communist insurgency seeking the reunification of Vietnam. The U.S. provided weapons and support, but South Vietnam failed to defeat Vietcong insurgents. Diem was assassinated in 1963 and a series of military dictators followed as the situation in South Vietnam continued to deteriorate. The American public remained largely unaware of Vietnam in the early 1960s, even as President John F. Kennedy secretly deployed sixteen thousand military advisors to help South Vietnam suppress a domestic communist insurgency. However, in August 1964 the USS Maddox reported incoming fire from North Vietnamese ships in the Gulf of Tonkin. Although the details of the incident are controversial, the Johnson administration exploited the event to escalate American involvement in Vietnam. Congress quickly passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting President Johnson the authority to deploy the American military to defend South Vietnam. U.S. Marines landed in Vietnam in March 1965, and the American ground war began. But no matter how many troops the Americans sent or how many bombs they dropped, they could not win. This was a different kind of war. Progress was not measured by cities won or territory taken but by body counts and kill ratios. Although American officials like General William Westmoreland and secretary of defense Robert McNamara claimed a communist defeat was on the horizon, by 1968 half a million American troops were stationed in Vietnam, nearly twenty thousand had been killed, and the war was still no closer to being won. Protests, which would provide the backdrop for the American counterculture, erupted across the country.

Question for Discussion

- Why did Ho Chi Minh emulate the US Declaration of Independence in his declaration?

3. Beyond Civil Rights

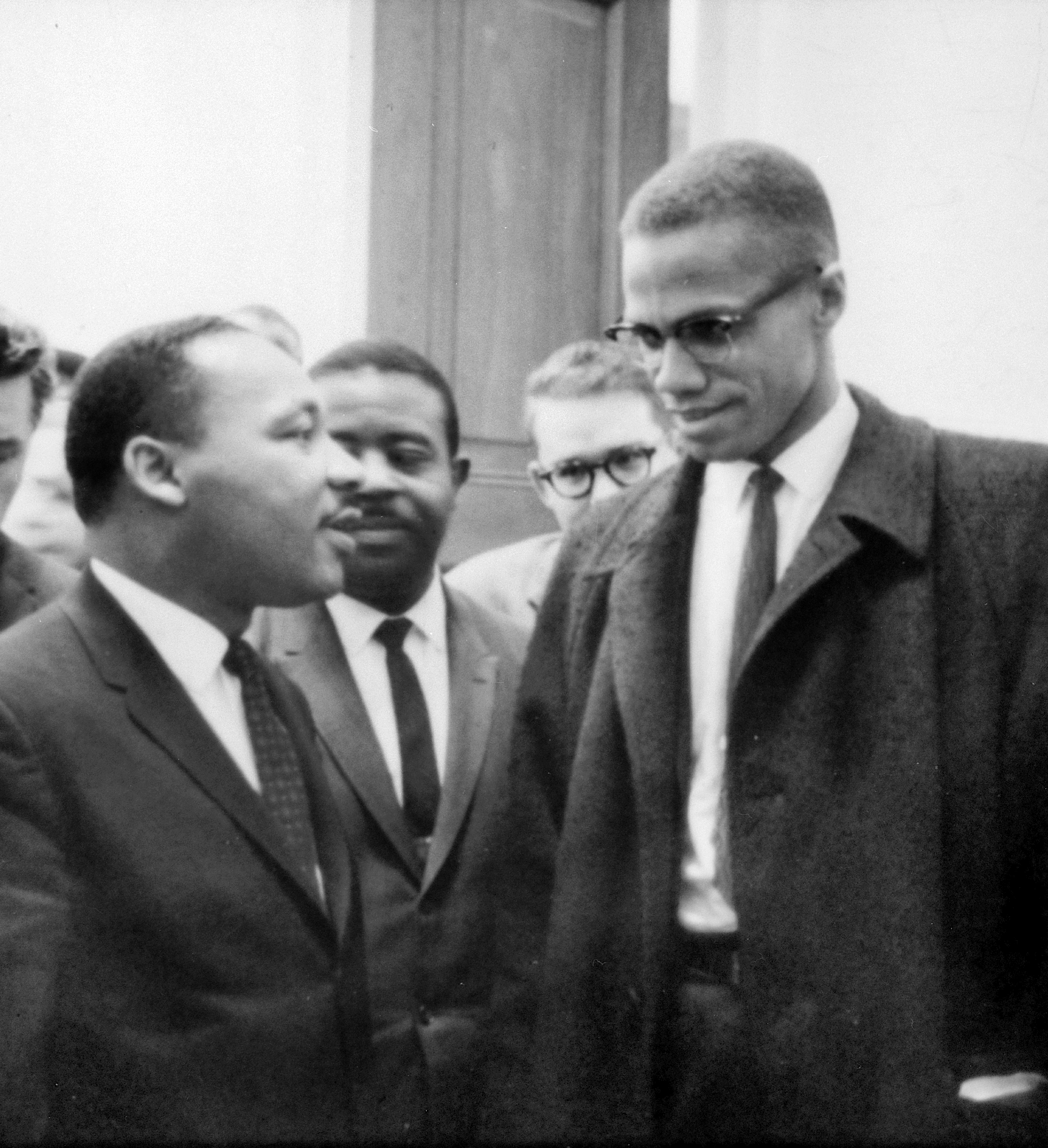

Despite substantial legislative achievements, frustrations with the slow pace of change grew. Tensions continued to mount in cities, which were plagued by riots throughout the 1960s, and the tone of the civil rights movement changed. Activists became less conciliatory and many embraced the more militant messages of the burgeoning Black Power Movement and Malcolm X, a Nation of Islam minister who encouraged African Americans to pursue freedom, equality, and justice by “any means necessary.” Prior to his assassination in 1965, Malcolm X emerged as a radical alternative to the racially integrated, largely Protestant approach of Martin Luther King Jr. Malcolm advocated armed resistance to defend the safety of black Americans, stating, “I don’t call it violence when it’s self-defense, I call it intelligence.” King and mainstream organizations like the NAACP and the Urban League criticized Malcolm X for what they called racial demagoguery. King believed Malcolm’s speeches were a “great disservice” to black Americans, complaining about the problems of African Americans without offering solutions. The differences between King and Malcolm X created an ideological tension that split black political thought throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

By the late 1960s, a radicalized SNCC, led by figures such as Stokely Carmichael, had expelled its white members and moved on from interracial efforts in the South, focusing instead on problems in northern cities. SNCC activists became frustrated with institutional tactics and turned away from the organization’s founding principle of nonviolence. They wanted African Americans to play a lead role in cultivating black institutions and articulating black interests rather than relying on interracial, moderate approaches. At a June 1966 civil rights march, Carmichael told the crowd, “What we gonna start saying now is black power!” The slogan not only resonated with audiences, it also stood in direct contrast to King’s “Freedom Now!” campaign. Carmichael asserted that “black power means black people coming together to form a political force.” To others it also meant violence. In 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. The Black Panthers became the standard-bearers for direct action and self-defense, to liberate black communities from white power structures. The revolutionary organization also sought reparations and exemptions for black men from the military draft. Citing police brutality and racist governmental policies, the Black Panthers aligned themselves with the “other people of color in the world” against whom America was fighting abroad. Although it was most known for its open display of weapons, military-style dress, and black nationalist beliefs, the party’s 10-Point Plan also included employment, housing, and education. The Black Panthers worked in local communities to run “survival programs” that provided food, clothing, medical treatment, and drug rehabilitation. They focused on modes of resistance that empowered black activists on their own terms.

But African Americans weren’t the only minority groups struggling to assert themselves in the 1960s. The successes of the civil rights movement and grassroots activism inspired countless new movements. In the summer of 1961, for instance, frustrated Native American university students founded the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC) to draw attention to the plight of indigenous Americans. In the Pacific Northwest, the council advocated for tribal fisherman to have immunity from conservation laws on reservations and in 1964 held a series of “fish-ins” where activists cast nets and waited for the police to arrest them. The NIYC’s militant rhetoric and use of direct action began a Red Power intertribal movement designed to draw attention to Native issues and to protest discrimination. The American Indian Movement (AIM) and other activists staged dramatic demonstrations. In November 1969, dozens began a year-and-a-half-long occupation of the abandoned Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. In 1973, hundreds occupied the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, site of the infamous 1890 Indian massacre, for several months.

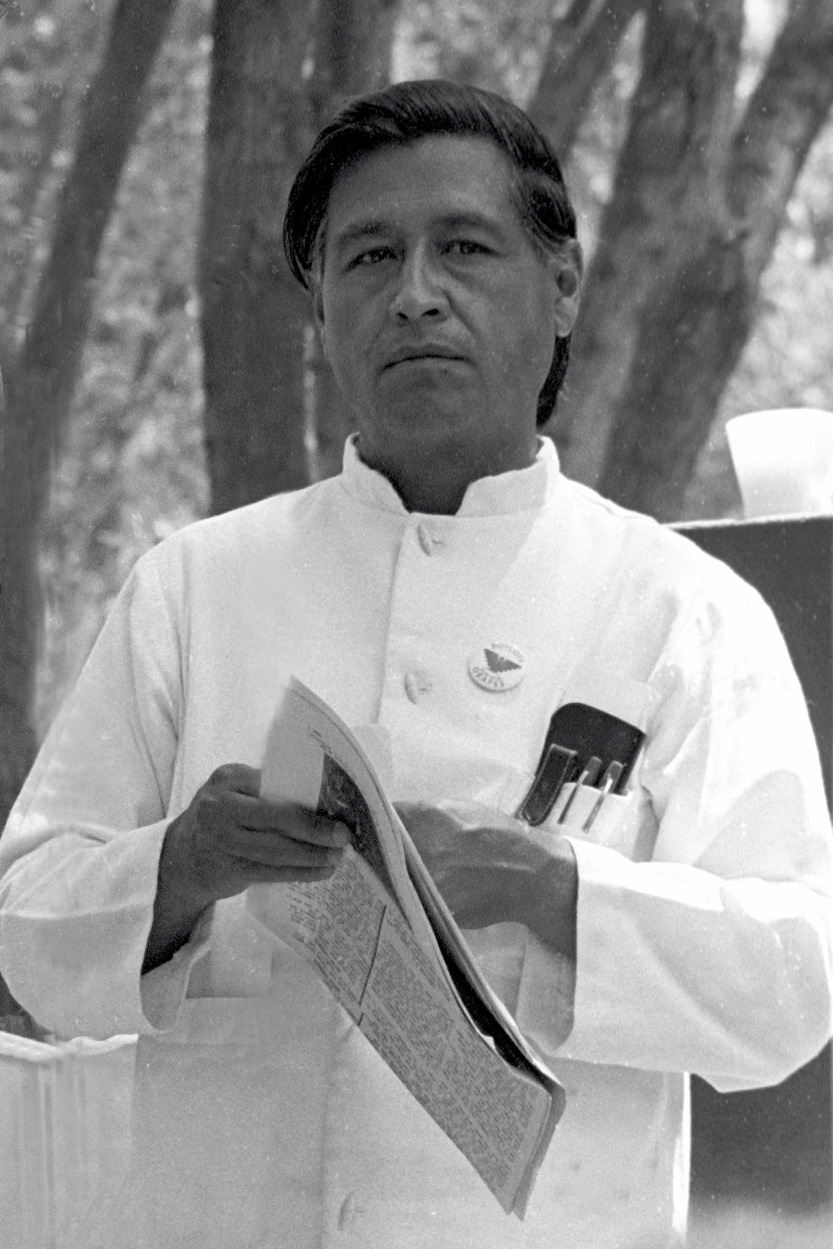

Meanwhile, the Chicano movement in the 1960s emerged out of the broader Mexican American civil rights movement of the post–World War II era. The movement confronted discrimination in schools, politics, agriculture, and other institutions. Organizations like the Mexican American Political Association and the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund patterned themselves after similar groups in the African American civil rights movement. Cesar Chavez became the most well-known figure of the Chicano movement, using nonviolent tactics to campaign for farm workers’ rights in the grape fields of California. Chavez and activist Dolores Huerta founded the National Farm Workers Association, which eventually became the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA). The UFWA fused the causes of Chicano and Filipino activists protesting the exploitation of workers on California farms. In addition to leading a hunger strike and a boycott of table grapes, Chavez led a three-hundred-mile march in March and April 1966 from Delano, on the southern end of California’s agricultural Central Valley, to the state capital of Sacramento on the northern end. The pro-labor campaign received national attention and the support of prominent political figures such as Robert Kennedy. Chavez’s birthday, March 31, is now observed as a federal holiday in California, Colorado, and Texas.

The feminist movement also grew in the 1960s. Women were active in both the civil rights movement and the labor movement, but their increasing awareness of gender inequality led women began to form a movement of their own. Like the early civil rights activists, an older generation of women who preferred to work within state institutions were prominent in the early part of the decade. When John F. Kennedy established a Presidential Commission on the Status of Women in 1961, former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt headed the effort. The commission’s report found discriminatory provisions in the practices of industrial, labor, and governmental organizations and advocated for “changes, many of them long overdue, in the conditions of women’s opportunity in the United States.” Change was recommended in employment practices, federal tax and benefit policies affecting women’s income, labor laws, and services for women as wives, mothers, and workers. These actions would ameliorate the types of discrimination primarily experienced by middle-class white working women, who were used to advocating through institutional structures like government agencies and unions. The concerns of poor and nonwhite women lay largely beyond the scope of the report.

Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique hit bookshelves the same year the commission released its report. Friedan had been active in the union movement and was a mother in the new suburban landscape of postwar America. Friedan helped many white middle-class American women recognize that their dissatisfaction as housewives was not something wrong with their marriages or themselves, but instead as a social problem experienced by millions of American women. Friedan observed that there was a “discrepancy between the reality of our lives as women and the image to which we were trying to conform, the image I call the feminine mystique.” Women were no longer content to blame their frustration on a loss of femininity, too much education, or too much female independence and equality with men. But middle-class white women were not the only activists addressing their issues. Mothers on welfare began to form local advocacy groups in addition to the National Welfare Rights Organization, founded in 1966. Mostly African American, these activists fought for greater benefits and more control over welfare policy and implementation. Women like Johnnie Tillmon fought for larger grants for school clothes and household equipment in addition to gaining due process and fair administrative hearings prior to termination of welfare entitlements.

At the end of the decade activists organized the Women’s Strike for Equality, celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of women’s right to vote. Sponsored by the National Organization for Women (NOW), the 1970 protest focused on employment discrimination, political equality, abortion, free childcare, and equality in marriage. In 1971, Michigan Congressperson Marth Wright Griffiths reintroduced a proposal for an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which passed the House in 1971 and in the Senate in 1972. ERA and many of the specific rights women’s activists claimed became the focus of a backlash led by conservative women and men who valued the traditional homemaker feminists rejected. The feminist movement would also fracture internally as minority women challenged white feminists’ racism and lesbians vied for more prominence within feminist organizations.

American environmentalism during the 1960s benefited from Americans’ recreational use of nature. Postwar Americans backpacked, went to the beach, fished, and joined birding organizations in greater numbers than ever before. These experiences, along with increased formal education, made Americans more aware of threats to the environment and to themselves. Many of these threats increased in the postwar years as developers bulldozed open space for suburbs and new hazards emerged from agricultural chemicals and industrial pollutants. When biologist Rachel Carson published her landmark book, Silent Spring, in 1962, a new concern for the environment swept America. Silent Spring argued for the interconnectedness of ecological and human health. Pesticides that accidentally killed bird populations, Carson argued, also posed a threat to human health. Carson’s argument was compelling to many Americans, including President Kennedy, although it was virulently opposed by chemical industry spokesmen who suggested the book was the product of an emotional woman, not a scientist. After Silent Spring, environmentalism continued to expand rapidly. Earth Day, on April 22, 1970, was the largest demonstration in American history up to that time. But even before the massive gathering for Earth Day, lawmakers from the local to the federal level had pushed for regulations to clean up the air and water. President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act into law in 1970, requiring environmental impact statements for any project directed or funded by the federal government. He also created the Environmental Protection Agency, the first agency charged with studying, regulating, and disseminating knowledge about the environment. A raft of laws followed to increase protection of air, water, endangered species, and natural areas.

Questions for Discussion

- What were the differences between Martin Luther King and Malcolm X?

- Were there common themes and techniques that movements such as Civil Rights, Women’s Rights, Latin Americans and Environmentalists all used?

4. The Moon, but…

To Americans in 1968, the country seemed to be unraveling. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed on April 4, 1968. He had reflected on his own mortality during a rally the night before. Confident that the civil rights movement would succeed without him, he brushed away fears of death. “I’ve been to the mountaintop,” he said, “and I’ve seen the promised land.” But America wasn’t prepared for the loss of its greatest civil rights leader. Riots broke out in over a hundred cities. Two months later, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was killed campaigning in California. He had been the last hope of many liberal idealists. Anger and disillusionment washed over the country. As the Vietnam War descended ever deeper into a brutal stalemate and the Tet Offensive exposed the lies of the Johnson administration, students shut down college campuses and government facilities. Protests enveloped the nation. For many sixties idealists, the violence of 1968 represented the death of a dream. Disorder overshadowed hope and progress. And for conservatives, the chaos was confirmation of all of their fears. Americans of 1968 turned their back on hope. They wanted peace and stability. They wanted “law and order.”

In July 1969, Americans watched the Apollo 11 moon landing on their TVs and celebrated both the human achievement and victory in the space race against the Soviet Union. Neil Armstrong’s “Giant leap for mankind” fulfilled the promise of the late John F. Kennedy, who had declared in 1961 that the United States would put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. But while Americans marveled at the achievement, the brief moment of wonder only punctuated years of turmoil. The Vietnam War disillusioned a generation, riots rocked cities, protests hit campuses, and assassinations robbed the nation of many of its leaders. If the Woodstock music festival of August 1969 captured the idealism of the sixties youth culture, the Altamont concert the following December revealed its dark side. Drugs, music, and youth resulted in not peace and love but anger, violence, and death. While many Americans in the 1970s continued to celebrate the political and cultural achievements of the previous decade, a more anxious, conservative mood grew across the nation. For some, the United States had not gone nearly far enough to promote social justice; for others, the nation had gone too far, unfairly trampling the rights of one group to promote the selfish needs of another. Onto these brewing dissatisfactions, the 1970s dumped the divisive remnants of a failed war, the country’s greatest political scandal, and an intractable economic crisis. It seemed as if the nation was ready to unravel.

Questions for Discussion

- Why was the moon landing so significant?

- Were concerts an accurate expression of youth culture?

5. Vietnam drags on

Perhaps no single issue contributed more to public disillusionment than the Vietnam War. The Johnson administration, which many believed had begun the war under false pretenses, escalated American involvement by deploying hundreds of thousands of troops to prevent the communist takeover of the south. Stalemates, body counts, hazy war aims, and especially the draft produced an antiwar movement and triggered protests throughout the United States and Europe. With no end in sight, protesters burned draft cards, refused to pay income taxes, occupied government buildings, and delayed trains loaded with war materials. By 1967, antiwar demonstrations were drawing hundreds of thousands. In one protest, hundreds were arrested after surrounding the Pentagon. Vietnam was also the first “living room war.” Open access to the battlefield provided unprecedented coverage of the conflict’s brutality. Americans confronted grisly images of casualties and atrocities. In 1965, the CBS Evening News showed U.S. Marines burning the South Vietnamese village of Cam Ne with little regard for the lives of its occupants, who had been accused of aiding Vietcong guerrillas. Rather than addressing the Marines’ actions, president Johnson berated the head of CBS, yelling over the phone, “Your boys just shat on the American flag.”

While the U.S. government imposed no formal censorship on the press during Vietnam, the White House and military used deceptive press briefings and interviews to paint a false image of the war. The United States was winning the war, officials claimed. They cited numbers of enemies killed, villages “secured”, and South Vietnamese troops trained. However, American journalists in Vietnam quickly realized the hollowness of such claims and the press corps began referring to afternoon briefings in Saigon as “the Five o’Clock Follies”. Editors frequently toned down their reporters’ pessimism, preferring the misinformation they received from government officials. But stories like CBS’s Cam Ne piece exposed a credibility gap, which was growing into a yawning chasm between the claims of official sources and the increasingly evident reality on the ground in Vietnam. Nothing did more to expose this gap than the 1968 Tet Offensive. In January, communist forces attacked more than one hundred American and South Vietnamese sites throughout South Vietnam, including the American embassy in Saigon. While U.S. forces beat back the surprise attack and inflicted heavy casualties on the Vietcong, Tet demonstrated that despite the propaganda of administration officials, the enemy could still strike at will anywhere in the country, even after years of war. Subsequent stories and images eroded public trust even further. In 1969, investigative reporter Seymour Hersh revealed that U.S. troops had raped and massacred hundreds of civilians in the village of My Lai. Three years later, Americans cringed at Nick Ut’s wrenching photograph of a naked Vietnamese child fleeing an American napalm attack. More and more Americans turned against the war.

Reeling from the war’s growing unpopularity, on March 31, 1968, President Johnson announced on national television that he would not seek reelection to a second full term. Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy battled for the Democratic Party nomination. After Robert Kennedy was assassinated in June, the Democratic Party’s national convention in Chicago erupted into violence. When the Democratic Party establishment nominated Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey rather than the popular anti-war candidate McCarthy, activists protested what they considered the hijacking of the process. Demonstrators planned massive protests in Chicago’s public spaces. Initial protests were peaceful, but the situation quickly soured as police issued threats and young people began to taunt and goad officials. Many of the assembled students had protest and sit-in experiences only in the relative safe havens of college campuses and were unprepared for Mayor Richard Daley’s aggressive and heavily armed police force and National Guard troops in full riot gear. Attendees recounted vicious beatings at the hands of police and Guardsmen, but many young people, remembering the public sympathy won via images of brutality against unarmed protesters during the civil rights movement, continued stoking the violence. Clashes spilled from the parks into city streets, and eventually the smell of tear gas penetrated the upper floors of the opulent hotels hosting Democratic delegates. Chicago’s brutality overshadowed the convention and culminated in an internationally televised, violent standoff in front of the Hilton Hotel. “The whole world is watching,” the protesters chanted. Local police brutally assaulted protesters on national television. For many Americans, the violent clashes outside the convention hall reinforced their belief that civil society was unraveling. Republican challenger Richard Nixon played on these fears, running on a platform of “law and order” and a vague plan to end the war. To appeal to Americans tired of the wasteful war, Nixon promised to phase out the draft, train South Vietnamese forces to fight for themselves, and gradually withdraw American troops. At the same time, Nixon appealed what he called the “silent majority” of Americans by calling for an “honorable” end to U.S. involvement that he later called “peace with honor.” Nixon narrowly edged out Humphrey in the fall’s election.

Campaign promises of American withdrawal, however, were ignored in a dramatic escalation of conflict. Looking to force the North Vietnamese to the negotiating table, Nixon pursued a “madman strategy” of attacking communist supply lines across Laos and Cambodia. Conducted without public knowledge or congressional approval, the bombings failed to spur the peace process, and talks stalled before the American-imposed November 1969 deadline. News of the illegal attacks renewed antiwar demonstrations. Police and National Guard troops killed six college students in separate protests at Jackson State University in Mississippi and at Kent State University in Ohio in 1970. Another three years passed and another twenty thousand American troops died before an agreement was reached. After Nixon threatened to withdraw all aid, the North and South Vietnamese governments signed the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973, allowing an end of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Peace was tenuous, and when war resumed North Vietnamese troops quickly overwhelmed southern forces. By 1975, despite nearly a decade of direct American military engagement, Vietnam was united under a communist government. The Vietnam War poisoned many Americans’ perceptions of their government and its role in the world. But while antiwar demonstrations attracted considerable media attention and are remembered today as a hallmark of the sixties counterculture, many Americans were wary of the rapid social changes that reshaped American society in the 1960s and worried that protests threatened an already tenuous civil order. A growing number of Americans turned to conservatism.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did Americans fail to support the war in Vietnam as they had supported previous wars?

- What effect do you think the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy had on US politics?

6. Nixon

Beleaguered by an unpopular war, inflation, and domestic unrest, President Johnson opted against reelection. The 1968 presidential election was shaped by Vietnam and social unrest as much as by the campaigns of Johnson’s Vice President Hubert Humphrey, former VP Richard Nixon, and third-party challenger George Wallace, the infamous segregationist governor of Alabama. The Democratic Party was in disarray in the spring of 1968, after senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy had both challenged Johnson in the primary and the president had responded with his shocking announcement. Nixon’s candidacy was aided further by riots that broke out across the country after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the shock of the Robert Kennedy assassination in June, and the chaos of the Democratic convention. The Republican’s campaign was defined by a pledge to restore peace and prosperity to what he called “the silent center; the millions of people in the middle of the political spectrum.” This campaign for the “silent majority” was carefully calibrated to attract moderate and conservative suburban Americans by linking liberals with violence and protest and rioting. Meanwhile, Humphrey struggled to distance himself from Johnson and maintain working-class support in northern cities, where voters were attracted by Wallace’s appeals for law and order and rejection of civil rights. Humphrey had union support that helped him in northern cities, but it was not enough. Nixon won by less than one percent, taking 43.3 percent of the popular vote to Humphrey’s 42.7 percent. Wallace, meanwhile, carried five states in the Deep South, and his 13.5 percent of the popular vote was a very impressive showing for a third-party candidate. Although Republicans won a few seats, Democrats retained control of both the House and Senate and Richard Nixon entered the White House in January 1969 with the opposition party controlling both houses.

Nixon focused his energies on American foreign policy, announcing the Nixon Doctrine which asserted the supremacy of American democratic capitalism committed the United States to continue supporting its allies financially, but denounced previous administrations’ willingness to commit American forces to Third World conflicts. Nixon told other nations to take responsibility for their own defense; turning America away from a policy of active, anticommunist containment, toward a new strategy of détente.” Promoted by national security advisor and eventual secretary of state Henry Kissinger, détente aimed to thaw relations with America’s Cold War rivals and freeze the growth of nuclear weapons. Taking advantage of tensions between communist China and the Soviet Union, Nixon pursued closer relations with both in order to strengthen the United States’ position relative to each. The strategy seemed to work. Nixon became the first American president to visit communist China in 1971 and the first since Franklin Roosevelt to visit the Soviet Union in 1972. Direct diplomacy and cultural exchange programs with both countries resulted in the formal normalization of U.S.-Chinese relations and the signing of two U.S.-Soviet arms agreements: the antiballistic missile (ABM) treaty and the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I). By 1973, after almost thirty years of Cold War tension, peaceful coexistence suddenly seemed possible.

Soon, though, the calm produced by a thawing of the Cold War gave way to a new instability. In November 1973, Nixon appeared on television to inform Americans that the United States was “heading toward the most acute shortages of energy since World War II.” Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), a cartel of the world’s leading oil producers, embargoed oil exports to the United States in retaliation for American intervention in the Middle East. The U.S. had supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War, a three-week conflict begun by Egypt and Syria in an unsuccessful effort to regain territory Israel had occupied since the Six-Day War of 1967. The embargo launched the first U.S. energy crisis. By the end of 1973, the global price of oil had quadrupled. Drivers waited in line for hours to fill up their cars. Gas was rationed and many stations ran out. OPEC ended the embargo in 1974, but the economic damage had been done. Like the Vietnam War, the oil crisis showed that small countries could still hurt the United States. And like Vietnam, the energy crisis accelerated disenchantment with the United States’ role in the world and the quality of its leaders. Worse, government scandals began eroding trust in America’s public institutions. In 1971, the Nixon administration tried unsuccessfully to sue the New York Times and the Washington Post to prevent the publication of the Pentagon Papers, a confidential and damning history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam commissioned by the Defense Department and later leaked. The papers showed how presidents from Truman to Johnson had repeatedly deceived the public regarding the war’s scope and direction. Nixon faced a rising tide of congressional opposition to the war, leading to unprecedented oversight of American war spending. In 1973, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution, dramatically reducing the president’s ability to wage war without congressional consent.

However, no scandal did more to destroy public trust than Watergate. On June 17, 1972, five men were arrested inside the offices of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in the Watergate Hotel Complex in downtown Washington, D.C. After being tipped off by a security guard, police found the men attempting to install sophisticated bugging equipment. One of those arrested was a former CIA employee working as a security aide for the Nixon administration’s Committee to Re-elect the President. While there was no direct evidence that Nixon had specifically ordered the Watergate break-in, he was in the habit of recording all the conversations he had with people in the Oval Office. In one of these secret recordings investigators found a conversation between Nixon and his chief of staff in which the president ordered that the DNC chairman be illegally wiretapped to obtain the names of the committee’s financial supporters. The names would then be given to the Justice Department and the Internal Revenue Service to investigate their personal affairs to dig up “dirt”. Nixon was also recorded ordering his chief of staff to break into the offices of the Brookings Institution and take files relating to the war in Vietnam, saying, “Goddammit, get in and get those files. Blow the safe and get it.” When news began to get out about the Watergate break-in, the White House launched a massive cover-up. Administration officials ordered the CIA to halt the FBI investigation (which the CIA had no authority to do) and paid hush money to the burglars and White House aides. Nixon distanced himself from the incident publicly and went on to win a landslide election victory against South Dakota Senator George McGovern in November 1972. But two persistent journalists at the Washington Post, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, continued to surface information that tied the burglaries ever closer to the CIA, the FBI, and the White House. The Senate held televised hearings. Citing executive privilege, Nixon refused to comply with orders to produce tapes from the White House’s secret recording system. In July 1974, the House Judiciary Committee approved a bill to impeach the president. Nixon resigned before the full House could vote on impeachment. He became the first and only American president to resign from office. Nixon’s vice president, Spiro Agnew, had resigned in scandal a year earlier, after being implicated in a bribery and tax evasion scheme unrelated to Watergate. He had been replaced with the leader of the House Republican caucus, Michigan Congressman Gerald Ford. Ford was sworn in as Nixon’s successor and a month later granted the disgraced president a full pardon. Nixon disappeared from public life without ever publicly apologizing, accepting responsibility, or facing charges.

Questions for Discussion

- What were the successes of the Nixon presidency?

- Did the Republicans represent a “silent majority”?

7. Deindustrialization

The postwar decades are remembered as a golden age for American workers; partly due to the fact that their economic gains were temporary. But during the 1950s and 60s, Americans of all classes benefited from postwar prosperity. Unemployment was low and a highly progressive tax system and powerful unions lowered general income inequality. Working-class standards of living nearly doubled between 1947 and 1973. But general prosperity masked deeper vulnerabilities. One of the best examples of the decline of American industry is the story of Detroit Michigan. Detroit had boomed during World War II. When auto manufacturers like Ford and General Motors had converted their assembly lines for the American war effort, observers had dubbed the city the “arsenal of democracy.” After the war, however, automobile firms began closing urban factories and moving to the suburbs. Many manufacturing firms began to reduce labor costs by automating, downsizing, and relocating to areas with “business friendly” policies like low tax rates, anti-union right-to-work laws, and low wages. Between 1950 and 1958, Chrysler cut its Detroit production workforce in half. Ford and General Motors eliminated more than even Chrysler. In the years between 1953 and 1960, East Detroit lost ten plants and over seventy-one thousand jobs. Because Detroit was a single-industry city, decisions made by the Big Three automakers reverberated across the city’s industrial landscape. As ancillary suppliers like machine tool companies were cut out of the supply chain, they were forced to cut their own workforces. Between 1947 and 1977, the number of manufacturing firms in the city dropped from over three thousand to fewer than two thousand. Manufacturing jobs fell from 338,400 to 153,000 over the same three decades.

Deindustrialization fell heaviest on the city’s African Americans. Although many middle-class black Detroiters managed to move out of the city, by 1960, 19.7 percent of black autoworkers in Detroit were unemployed, compared to just 5.8 percent of whites. Over time, Detroit devolved into unemployment, crime, and crippled municipal resources. When riots rocked Detroit in 1967, 25 to 30 percent of black residents between ages eighteen and twenty-four were unemployed. Deindustrialization in Detroit and elsewhere also went hand in hand with the long assault on unionization that began in the aftermath of World War II. Lacking the political support they had enjoyed during the New Deal years, labor organizations such as the CIO and the UAW shifted tactics and accepted labor-management accords in which cooperation, not agitation, was the strategic objective. At the same time, bureaucracy and corruption increasingly weighed down unions and alienated workers and the general public. Conservative politicians seized on popular suspicions of Big Labor, stepping up their criticism of union leadership and positioning themselves as workers’ true ally. Labor’s decline also reflected ideological changes in American liberalism. By the 1960s, many Democrats had forsaken working-class politics. They began to portray poverty not as the result of structural flaws in the national economy, but as the failure of individuals to take full advantage of the American system. Roosevelt’s New Deal might have attempted to rectify unemployment with government jobs, but Johnson’s Great Society and its imitators funded government-sponsored job training, even in places without available jobs. Union leaders in the 1950s and 1960s typically supported such programs and philosophies. Internal racism also weakened the labor movement. While national CIO leaders encouraged black unionization, white workers often opposed the integrated shop. In Detroit and elsewhere after World War II, white workers organized “hate strikes” and walked off the job rather than work with African Americans. And like the middle class, white workers opposed residential integration, claiming that black newcomers would lower property values.

By the mid-1970s, America’s widely-shared postwar prosperity leveled off and began to retreat. Growing international competition, technological inefficiency of industries that paid profits out to shareholders rather than reinvesting, and declining productivity stunted working- and middle-class wages. As the country entered a recession triggered by the oil shock, wages decreased and the pay gap between workers and management expanded, reversing three decades of postwar contraction. The tax code became less progressive and labor lost its foothold in the marketplace. Unions represented a third of the workforce in the 1950s, but only one in ten workers belonged to one as of 2015. American firms fled pro-labor states in the 1970s and 1980s. Some went overseas in the wake of new trade treaties to exploit low-wage foreign workers, but others turned to anti-union states in the South and West. Factories shuttered in the North and Midwest, leading commentators by the 1980s to dub America’s former industrial heartland the Rust Belt. With this, they contrasted the prosperous and dynamic Sun Belt. Southern and western states saw unprecedented economic, industrial, and demographic growth after World War II. During the New Deal, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had declared the American South “the nation’s No. 1 economic problem” and had injected massive federal subsidies, investments, and military spending into the region. During the Cold War, Sun Belt politicians lobbied hard for military installations and government contracts for their states. And southern states’ hostility toward organized labor attracted corporate leaders. The Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 facilitated cheap, non-unionized labor, low wages, and lax regulations that pulled northern industries away from the Rust Belt. Skilled northern workers followed the new jobs southward and westward, lured by cheap housing and a warm climate made more tolerable by modern air conditioning.

The South attracted business by promising firms wouldn’t be called on to share their profits. Middle-class whites grew rich, but often these were recent transplants, not native southerners. As the decaying cotton economy shed farmers and laborers, poor white and black southerners found themselves mostly excluded from the fruits of the Sun Belt. Public investments were scarce. White southern politicians channeled federal funding away from public education and toward high-tech industry and university-level research. The Sun Belt had growing numbers of high-skill, high-wage jobs but lacked the social and educational infrastructure needed to train native poor and middle-class workers for those jobs. Regardless, more jobs meant more people, and by 1972, southern and western Sun Belt states had more voters than the Northeast and Midwest. This gap continues to grow. And although the region’s economic and political ascendance was a product of massive federal spending, not only in government contracts but also in infrastructure investments to provide services like water in arid states, New Right politicians constructed a political brand centered on “small government” that found loyal support in the Sun Belt. These business-friendly politicians combined Protestantism and free market ideology, creating a potent new conservative movement. Prosperous and mobile, Sun Belt suburbanites gravitated toward an individualistic vision of free enterprise espoused by the Republican Party. Some, especially those most vocally anticommunist, joined groups like the Young Americans for Freedom and the John Birch Society. Less radical suburban voters, however, still gravitated toward the more moderate brand of conservatism promoted by Richard Nixon.

Question for Discussion

- What was the main cause of deindustrialization?

8. Sexual Revolution

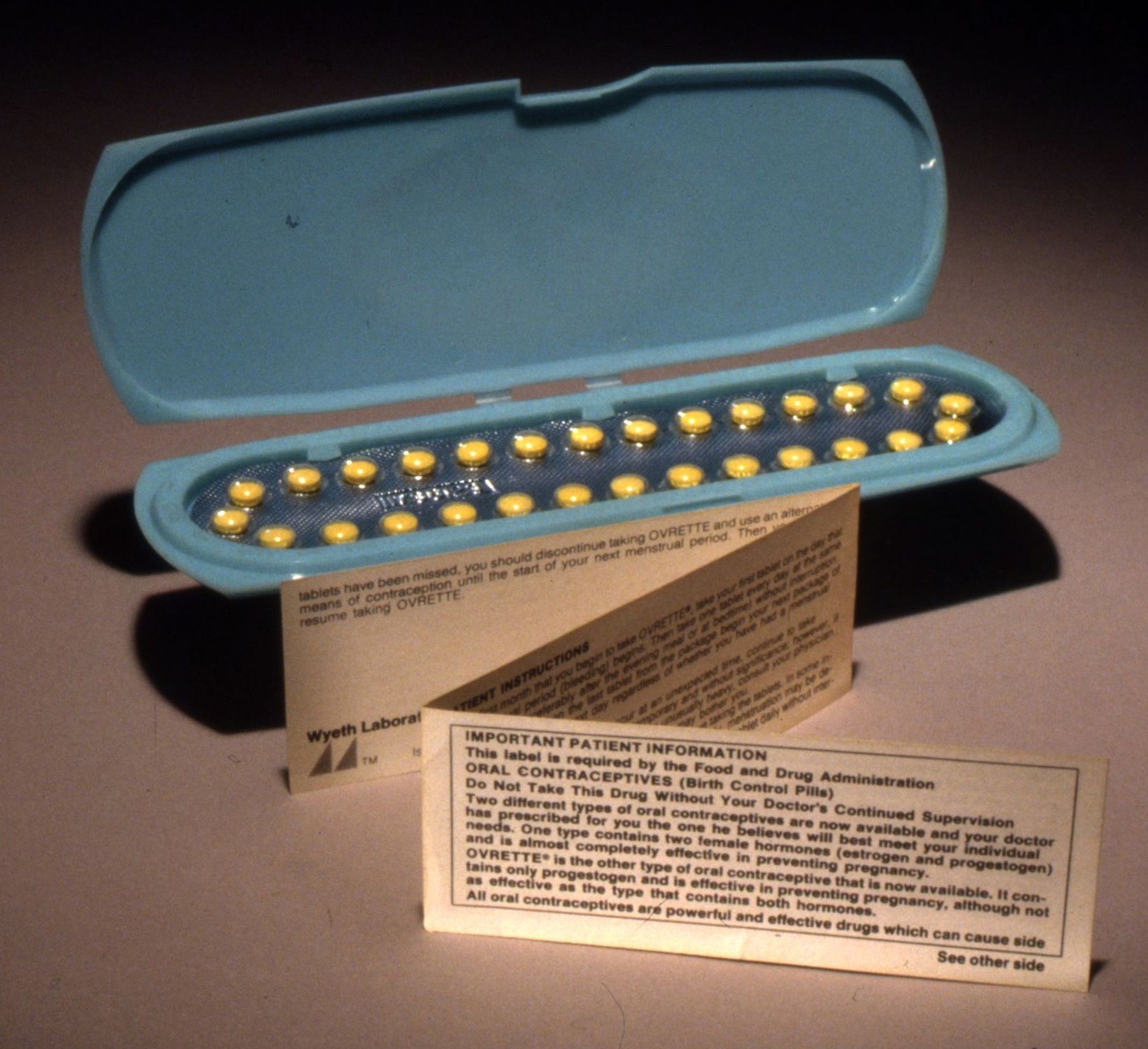

The sexual revolution continued into the 1970s. Many Americans, including feminists, gay men, lesbians, and straight couples, challenged strict gender roles and rejected the rigidity of the nuclear family. Cohabitation without marriage increased, couples married later or not at all, and divorce levels climbed. Sexuality, decoupled from marriage and procreation, became for many not only a source of entertainment but a worthy political cause.

A landmark legal ruling in 1973 established the battle lines for the “sex wars” of the 1970s. The Supreme Court’s 7–2 ruling in Roe v. Wade in 1973 recognized a constitutional “right to privacy.” and reasoned that “this right of privacy . . . is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” The Court decreed that states could not interfere with a woman’s right to an abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy and could only fully prohibit abortions during the third trimester. A woman’s right to control her body paralleled the fight for more control in their relationships. Between 1959 and 1979, the American divorce rate more than doubled. By the early 1980s, nearly half of all American marriages ended in divorce. The stigma attached to divorce evaporated and a growing sense of sexual and personal freedom motivated women to leave abusive or unfulfilling marriages. Legal changes also promoted higher divorce rates. Before 1969, most states required one spouse to prove that the other was guilty of a specific offense, such as adultery. In 1969, California adopted the first no-fault divorce law. By the end of the 1970s, almost every state had adopted some form of no-fault divorce. The new laws allowed for divorce on the basis of “irreconcilable differences,” even if only one party felt that he or she could not stay in the marriage.

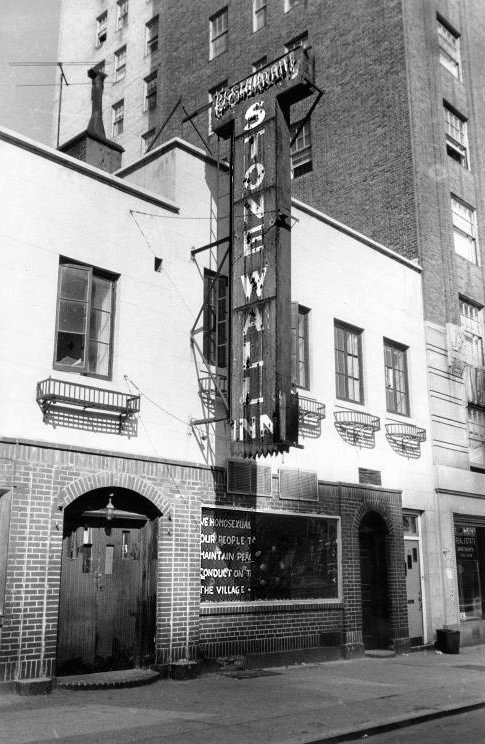

Gay men and women, meanwhile, negotiated a harsh world that stigmatized homosexuality as a mental illness or an immoral depravity. Inspired by the radicalism of the Black Power movement, protests of the Vietnam War, and the counterculture movement for sexual freedom, gay and lesbian activists agitated for a broader set of sexual rights. This activism was demonstrated in a 1969 uprising at the Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village. Police regularly raided gay bars and hangouts, but in June 1969, Stonewall patrons protested and began a multiday street battle that sparked a national movement for gay liberation. After Stonewall, gay activists increasingly attacked cultural norms that demanded they keep their sexuality hidden. Citing statistics that sexual secrecy contributed to suicide, activists urged people to come out and embrace their sexuality. A step towards the normalization of homosexuality occurred in 1973, when the American Psychiatric Association stopped classifying homosexuality as a mental illness. Pressure mounted on politicians. In 1982, Wisconsin became the first state to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation. More than eighty cities and nine states followed suit over the following decade. But progress proceeded unevenly, and gay Americans continued to suffer hardships from a hostile culture.

Question for Discussion

- Was sexual liberation for women and LGBT people a significant event or a distraction from more pressing issues?

9. The Misery Index

Although Richard Nixon eluded prosecution, Watergate continued to weigh on voters’ minds. It produced big congressional gains for Democrats in the 1974 midterm elections, and Gerald Ford’s pardon of Nixon destroyed his chances in the 1976 presidential race. Former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter, a nuclear physicist and peanut farmer who represented the rising generation of younger, racially liberal “New South” Democrats, captured the Democratic nomination. Carter did not identify with either his party’s liberal or conservative wing; his appeal was more personal than political. He ran on no great political issues, letting his background as a hardworking, honest, southern Baptist navy man ingratiate him to voters around the country. Carter was especially popular in his native South, where support for Democrats had wavered in the wake of the civil rights movement and George Wallace’s racist challenge. Carter’s wholesome image was a stark contrast to the memory of Nixon, and his government experience outside Washington gave him an advantage over the beltway insider who had pardoned Nixon. When Carter took the oath of office in January 1977, however, he became president of a nation in the midst of economic turmoil.

Oil shocks, inflation, stagnant growth, unemployment, and sinking wages weighed down the nation’s economy. Some of these problems were consequences of U.S. decisions to rebuild the shattered economies of Europe and Asia after the World War and during the Cold War. American diplomats used trade relationships to win influence and allies around the globe. They saw the economic health of their allies, particularly West Germany and Japan, as a crucial bulwark against the expansion of communism. American aid, investment, and special export privileges encouraged these nations to develop vibrant export-oriented economies at great cost to the United States. As American firms began moving to the Sun Belt to escape unions and preferred paying high shareholder dividends to reinvesting in new techniques and technology, foreign firms invested heavily, innovated, and created new “stakeholder” systems that included unions and communities in management decision-making. While the American economy stalled, Japan and West Germany soared and became major forces in the global production for autos, steel, machine tools, and electrical products. By 1970, the United States began to run massive trade deficits. The value of American exports dropped and the prices of its imports skyrocketed. Coupled with the huge cost of the Vietnam War (between $100 and $150 billion) and the rise of oil-producing states in the Middle East, growing trade deficits sapped the United States’ dominant position in the global economy.

American leaders didn’t know how to respond. The Nixon administration had allowed these rising industrial nations to maintain trade barriers that sheltered their domestic markets from foreign competition while they exported growing amounts of goods to the United States. By 1974, in response to U.S. complaints, many of these industrial nations revised their protectionist practices but developed subtler methods such as state subsidies for key industries to nurture their economies. The result was that Carter, like Ford before him, presided over a new economic dilemma: the simultaneous inflation and economic stagnation that became known as stagflation.” Neither Ford nor Carter had the means or ambition to protect American jobs and goods from foreign competition. American foreign policy had set the trend toward globalization in motion, and American policy-makers could not even agree on whether it was a good or bad thing, much less what to do about it. As firms and financial institutions invested, sold goods, and manufactured in new rising economies like Mexico, Taiwan, Japan, Brazil, and elsewhere, American politicians allowed them to sell their cheaper products in the United States. With the American government institutionalizing this new unfettered global trade, if only by inaction, many American manufacturers reasoned that the only viable path to sustained profitability was moving overseas, often by establishing foreign subsidiaries or partnering with foreign firms. Investment capital, especially in manufacturing, fled the United States looking for foreign investments and hastened the destruction of the productivity of American industry.

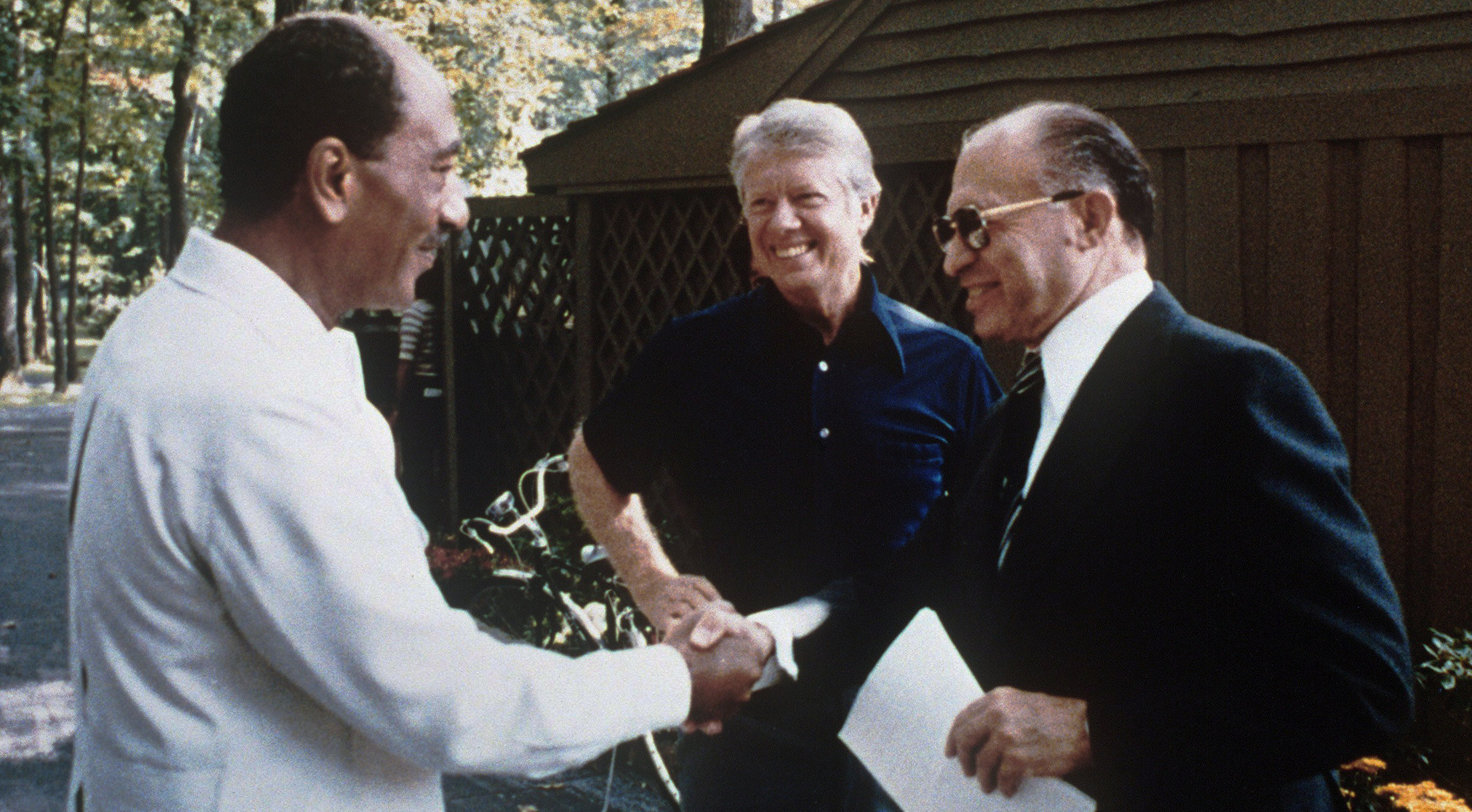

During the 1976 presidential campaign, Carter had pointed to the “misery index,” the sum of the unemployment rate added to the inflation rate, as an indictment of Gerald Ford and Republican rule. But Carter failed to slow the unraveling of the American economy, and the stubborn rise of both unemployment and inflation damaged his presidency. And just as Carter was unable to offer domestic policies to stem the unraveling of the American economy, his idealistic vision of human rights–based foreign policy crumbled. Carter had not made human rights a central theme in his campaign, but in May 1977 he declared his wish to move away from a foreign policy in which “inordinate fear of communism” caused American leaders to “adopt the flawed and erroneous principles and tactics of our adversaries.” Carter proposed instead “a policy based on constant decency in its values and on optimism in our historical vision.” Carter’s idealistic human rights policy tried to repair the damage done by the cynical foreign policies of his predecessors. He achieved some real victories: the United States reduced or eliminated aid to American-supported right-wing dictators guilty of extreme human rights abuses in places like South Korea, Argentina, and the Philippines. In September 1977, Carter negotiated the transfer to Panama of the Panama Canal, which cost him enormous political capital in the United States. A year later, in September 1978, Carter negotiated a peace treaty between Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat. The Camp David Accords represented the first time an Arab state had recognized Israel, and the first time Israel promised Palestine self-government. The accords had limits, for both Israel and the Palestinians, but they represented a major foreign policy achievement for Carter.

And yet Carter’s dreams of a human rights–based foreign policy crumbled before the Cold War and the realities of American politics. The United States continued to provide military and financial support for dictatorial regimes vital to American interests, such as the oil-rich state of Iran. When the U.S.-supported shah was deposed in November 1979, revolutionaries stormed the American embassy in Tehran and took fifty-two Americans hostage. Americans not only experienced another oil crisis as Iran’s oil fields shut down, they watched America’s news programs, for 444 days, remind them of the hostages and America’s new global impotence. Carter couldn’t win their release. A failed rescue mission only ended in the deaths of eight American servicemen. And Carter’s efforts to ease the Cold War with a new nuclear arms control agreement disintegrated under domestic opposition from conservative Cold War hawks such as Ronald Reagan, who accused Carter of weakness. A month after the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979, Carter committed the United States to defending its “interests” in the Middle East against Soviet incursions. The Carter Doctrine not only signaled Carter’s difficulty honoring his commitment to de-escalation and human rights, it testified to his increasingly desperate presidency.

With the collapse of American manufacturing, the stubborn rise of inflation, the sudden impotence of American foreign policy, and a culture ever more divided, a sense of unraveling pervaded the nation. “I want to talk to you right now about a fundamental threat to American democracy,” Jimmy Carter said in a surprise televised address on July 15, 1979. The president said the nation was suffering from a “malaise” that was partly due to the growing energy crisis, but was also something deeper. “The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways,” Carter said. “It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will.” American weakness was visible everywhere. And so, by 1980, many Americans—especially white middle- and upper-class Americans—felt a nostalgic desire for simpler times and simpler answers to the frustratingly complex geopolitical, social, and economic problems crippling the nation. The appeal of Carter’s soft drawl and Christian humility had signaled this yearning, but his utter failure to stop the unraveling of American power and confidence opened the way for a new movement that promised to undo the damage and restore the United States to its own nostalgic image of itself.

Questions for Discussion

- Did President Carter make a mistake by speaking openly about “malaise”?

- Assess Carter’s foreign policy: what were his main successes and failures?

10. Primary Sources

Lyndon Johnson on Voting Rights and the American Promise (1965)

On March 15, 1965, Lyndon Baines Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress to push for the Voting Rights Act. In his speech, Johnson not only advocated policy, he borrowed the language of the civil rights movement and tied the movement to American history.

Lyndon Johnson, Howard University Commencement Address (1965)

On June 4, 1965, President Johnson delivered the commencement address at Howard University, the nation’s most prominent historically black university. In his address, Johnson explained why “opportunity” was not enough to ensure the civil rights of disadvantaged Americans.

National Organization for Women, “Statement of Purpose” (1966)

The National Organization for Women was founded in 1966 by prominent American feminists, including Betty Friedan, Shirley Chisolm, and others. The organization’s “statement of purpose” laid out the goals of the organization and the targets of its feminist vision.

George M. Garcia, Vietnam Veteran, Oral Interview (2012/1969)

In 2012, George Garcia sat down to be interviewed about his experiences as a corporal in the United States Marine Corps during the Vietnam War. Alternating between English and Spanish, Garcia told of early life in Brownsville, Texas, his time as a U.S. Marine in Vietnam, and his experience coming home from the war.

Civil rights activists protested against the injustice of segregation in a variety of ways. Here, in 1965, marchers, some carrying American flags, march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to champion African American voting rights.

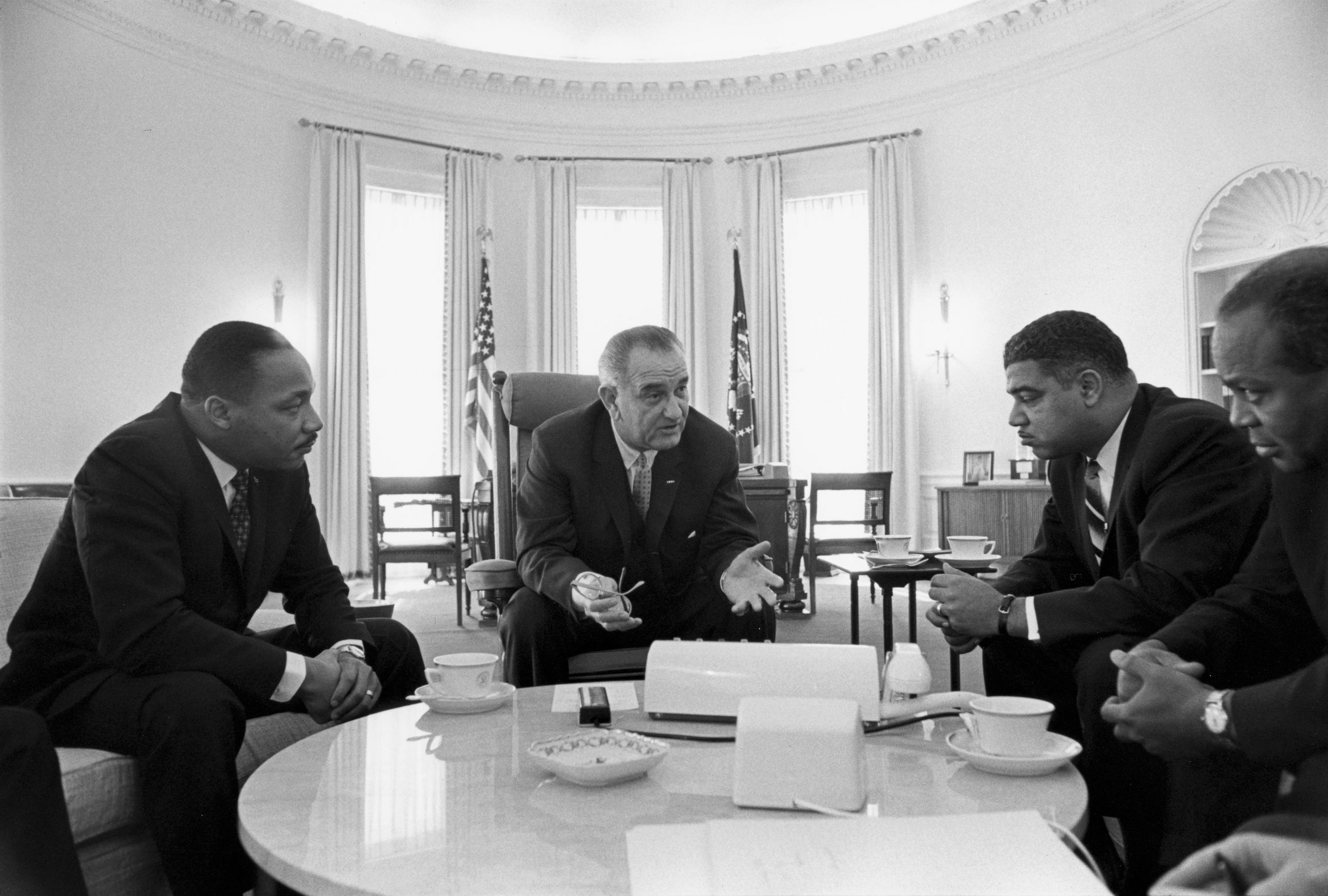

LBJ and Civil Rights Leaders (1964)

As civil rights demonstrations rocked the American South, civil rights legislation made its way through Washington D.C. Here, President Lyndon B. Johnson sits with civil rights leaders in the White House.

Women’s Liberation March (1970)

American popular feminism accelerated throughout the 1960s. The slogan “Women’s Liberation” accompanied a growing women’s movement but also alarmed conservative Americans. In this 1970 photograph, women march in Washington D.C. carrying signs reading, “Women Demand Equality,” “I’m a Second Class Citizen,” and “Women’s Liberation.”

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (1968)

Riots rocked American cities in the mid-late sixties. Hundreds died, thousands were injured, and thousands of buildings were destroyed. Many communities never recovered. In 1967, devastating riots, particularly in Detroit, Michigan, and Newark, New Jersey, captivated national television audiences. President Lyndon Johnson appointed an 11-person commission, chaired by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, to explain the origins of the riots and recommend policies to prevent them in the future.

Statement by John Kerry of Vietnam Veterans Against the War (1971)

On April 23, 1971, a young Vietnam veteran named John Kerry spoke on behalf of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War before the Senate Committee of Foreign Relations. Kerry, later a Massachusetts Senator and 2004 presidential contender, articulated a growing disenchantment with the Vietnam War and delivered a blistering indictment of the reasoning behind its prosecution.

Nixon Announcement of China Visit (1971)

Richard Nixon, who built his political career on anti-communism, worked from the first day of his presidency to normalize relations with the communist People’s Republic of China. In 1971, Richard Nixon announced that he would make an unprecedented visit there to advance American-Chinese relations. Here, he explains his intentions.

Barbara Jordan, 1976 Democratic National Convention Keynote Address (1976)

On July 12, 1976, Texas Congresswoman Barbara Jordan delivered the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention. As Americans sensed a fracturing of American life in the 1970s, Jordan called for Americans to commit themselves to a “national community” and the “common good.” Jordan began by noting she was the first black woman to ever deliver a keynote address at a major party convention and that such a thing would have been almost impossible even a decade earlier.

Jimmy Carter, “Crisis of Confidence” (1979)

On July 15, 1979, amid stagnant economic growth, high inflation, and an energy crisis, Jimmy Carter delivered a televised address to the American people. In it, Carter singled out a pervasive “crisis of confidence” preventing the American people from moving the country forward. A year later, Ronald Reagan would frame his optimistic political campaign in stark contrast to the tone of Carter’s speech, which would be remembered, especially by critics, as the “malaise speech.”

“Urban Decay” confronted Americans of the 1960s and 1970s. As the economy sagged and deindustrialization hit much of the country, many Americans associated major cities with poverty and crime. In this 1973 photo, two subway riders sit amid a graffitied subway car in New York City.

11. References

This chapter was written by Dan Allosso as a “remix” of parts of two chapters of The American Yawp with substantial original material added. The original chapters were edited by Samuel Abramson and Edwin Breeden, with content contributions by Samuel Abramson, Marsha Barrett, Brent Cebul, Michell Chresfield, William Cossen, Jenifer Dodd, Michael Falcone, Leif Fredrickson, Jean-Paul de Guzman, Jordan Hill, William Kelly, Lucie Kyrova, Maria Montalvo, Emily Prifogle, Ansley Quiros, Tanya Roth, and Robert Thompson. Seth Anziska, Jeremiah Bauer, Edwin Breeden, Kyle Burke, Alexandra Evans, Sean Fear, Anne Gray Fischer, Destin Jenkins, Matthew Kahn, Suzanne Kahn, Brooke Lamperd, Katherine McGarr, Matthew Pressman, Adam Parsons, Emily Prifogle, John Rosenberg, Brandy Thomas Wells, and Naomi R. Williams.

Recommended Reading

- Breines, Winifred. The Trouble Between Us: An Uneasy History of White and Black Women in the Feminist Movement.New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Brown-Nagin, Tomiko. Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement.New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1995.

- Cowie, Jefferson R. Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class. New York: New Press, 2010.

- Dallek, Robert. Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1961–1973.New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- D’Emilio, John. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940–1970.Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.

- Echols, Alice. Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967–1975.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

- Evans, Sara. Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

- Flamm, Michael W. Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest, and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Formisano, Ronald P. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Gitlin, Todd. The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage.New York: Bantam Books, 1987.

- Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd. “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past.” Journal of American History91 (March 2005): 1233–1263.

- Harvey, David. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Cambridge, UK: Blackwell, 1989.

- Isserman, Maurice. If I Had a Hammer: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left.Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

- Jenkins, Philip. Decade of Nightmares: The End of the Sixties and the Making of Eighties America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Johnson, Troy R. The American Indian Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Red Power and Self-Determination.Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008.

- Joseph, Peniel. Waiting ’til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America.New York: Holt, 2006.

- Kalman, Laura. Right Star Rising: A New Politics, 1974–1980. New York: Norton, 2010.

- Kazin, Michael, and Maurice Isserman. America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s.New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Lassiter, Matthew D. The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- MacLean, Nancy. Freedom Is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

- Marable, Manning. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. New York: Viking, 2011.

- Matusow, Allen J. The Unraveling of America: A History of Liberalism in the 1960s. New York: Harper and Row, 1984.

- McGirr, Lisa. Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Murch, Donna Jean. Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Orleck, Annelise. Storming Caesar’s Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty.New York: Beacon Books, 2005.

- Perlstein, Rick. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus.New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

- ———. Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. New York: Norton, 2003.

- Phelps, Wesley. A People’s War on Poverty: Urban Politics, Grassroots Activists, and the Struggle for Democracy in Houston, 1964–1976. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2014.

- Robnett, Belinda. How Long? How Long?: African American Women in the Struggle for Civil Rights.New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Rodgers, Daniel T. Age of Fracture. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2011.

- Roth, Benita. Separate Roads to Feminism: Black, Chicana, and White Feminist Movements in America’s Second Wave. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Sargent, Daniel J. A Superpower Transformed: The Remaking of American Foreign Relations in the 1970s. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Schulman, Bruce J. The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics. New York: Free Press, 2001.

- Springer, Kimberly. Living for the Revolution: Black Feminist Organizations, 1968–1980. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

- Stein, Judith. Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the 1970s. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Thompson, Heather Ann. Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. New York: Pantheon Books, 2016.

- Sugrue, Thomas. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Zaretsky, Natasha. No Direction Home: The American Family and the Fear of National Decline. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

https://youtu.be/thUu-G8aLvY

Media Attributions

- Lyndon_Johnson_meeting_with_civil_rights_leaders © Yoichi R. Okamoto is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bloody_Sunday-Alabama_police_attack © FBI is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Signing_of_the_EOA © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ho_Chi_Minh_1946 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- MLK_and_Malcolm_X_USNWR_cropped © us News and World Report is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cesar_chavez_crop2 © Work permit is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 03425v © Warren K. Leffler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 00750v © Thomas J. O'Halloran is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-Buzz_salutes_the_U.S._Flag © Neil Armstrong is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ARVN_in_action_HD-SN-99-02062.JPEG © U.S. Information Agency is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1920px-Vietnam_War_protestors_at_the_March_on_the_Pentagon © Frank Wolfe is licensed under a Public Domain license

- NIXONcampaigns © Ollie Atkins is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-Nixon_and_Zhou_toast © White House Photographer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Nixon_edited_transcripts © National Archives & Records Administration is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Abandoned_Packard_Automobile_Factory_Detroit_200 © Albert duce is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Patient_Package_Insert_for_Oral_Contraceptives_(FDA_079)_(8249451687) © FDA is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Stonewall_Inn_1969 © Diana Davies is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Think_Small © Doyle Dane Bernbach is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Camp_David,_Menachem_Begin,_Anwar_Sadat,_1978 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license