3 Empire and Jim Crow

Imperialism

The word empire typically conjures images of ancient Rome, Genghis Khan, or the British Empire: powers that depended on military conquest, colonization, occupation, or direct resource exploitation. But empires can take many forms and imperial processes occur in many contexts. One hundred years after the United States won its independence from the British Empire, some began to believe America was becoming (and perhaps should become) an empire of its own.

As Americans had explored and settled the West before the Civil War, a sense of “Manifest Destiny” had become a key component of popular culture. The idea that it was obvious, inevitable, and perhaps even God’s will that the United States should expand across the continent helped generate popular support for projects like the Mexican-American War and the ongoing Indian wars of the nineteenth century. In the decades after the American Civil War, the frontier was conquered to the point the Census could declare it “closed” in 1890. At that point the U.S. began to pursue American interests around the world. In the Pacific, Latin America, and the Middle East, the United States expanded on a long history of what proponents called exploration, trade, and cultural exchange but critics called annexation, invasion, and occupation. From either perspective, America began to look remarkably like an empire. And as the United States asserted itself abroad, it acquired increasingly higher numbers of foreign peoples at home. Imperialism and immigration raised similar questions about American identity: who was an “American,” and who wasn’t? What were the nation’s obligations to foreign powers and foreign peoples? How accessible and how fluid should American identity be for newcomers? These questions confronted late-nineteenth-century Americans with unprecedented urgency.

![Uncle Sam as a teacher, standing behind a desk in front of his new students who are labeled "Cuba, Porto [i.e. Puerto] Rico, Hawaii, [and] Philippines"; they do not look happy to be there. At the rear of the classroom are students holding books labeled "California, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, [and] Alaska". At the far left, an African American boy cleans the windows, and in the background, a Native boy sits by himself, reading an upside-down book labeled "ABC", and a Chinese boy stands just outside the door. A book on Uncle Sam's desk is titled "U.S. First Lessons in Self-Government".](https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/724/2020/01/28668v.jpg)

American military actions in the Pacific, China, and the Middle East reflected the nation’s new willingness to intervene in foreign governments to protect U.S. economic interests abroad. And America was not only ready to preserve foreign markets, it was willing to take territory. The United States acquired its first Pacific territories via the Guano Islands Act of 1856. Guano (dried sea-bird excrement) was the first important commercial fertilizer for industrial farming. The act created incentives for Americans to claim islands with guano deposits for the United States. Territory taken under the Guano Islands Act included parts of the Hawaiian chain, Midway atoll, and parts of American Samoa. These acquisitions were the first unincorporated island territories of the United States. They were not part of any other state or territory and they were not on the path to ever attain such a status. Though not well remembered, the act created a precedent for future American acquisitions.

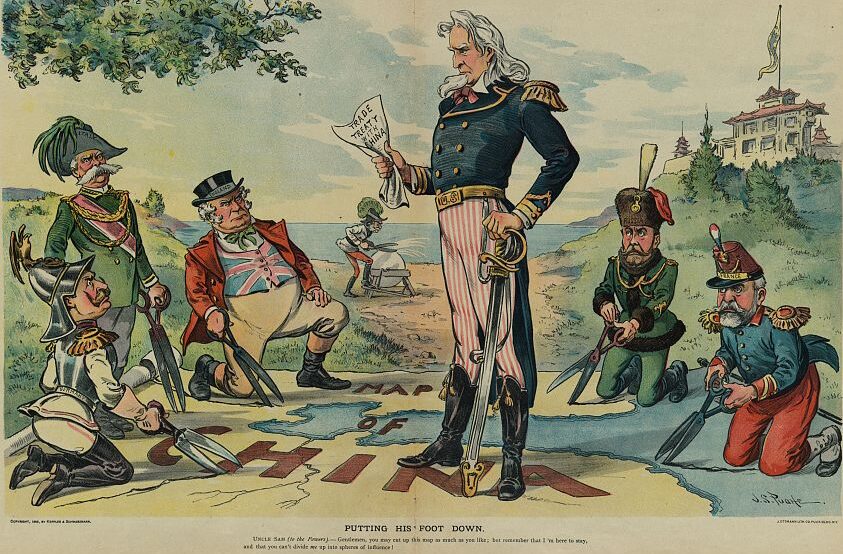

The United States had a long history of Pacific commerce. American merchant ships had been traveling to China since 1784. As a percentage of total American foreign trade, Asian trade remained comparatively small, and yet the idea that Asian markets were vital to American commerce affected American policy and, when those markets were threatened, prompted interventions. In 1900, American troops joined a multinational force that intervened to prevent the closing of trade threatened by the Boxer Rebellion, a movement opposed to foreign businesses and missionaries operating in China. President McKinley sent the Army without consulting Congress, setting a precedent for U.S. presidents to order American troops to action around the world under their executive powers.

In 1867, Mark Twain traveled to the Middle East as part of a large tour group of Americans. In a satirical travelogue, The Innocents Abroad, he wrote, “The people stared at us everywhere, and we stared at them. We generally made them feel rather small, too, before we got done with them, because we bore down on them with America’s greatness until we crushed them.” When Americans intervened in the Middle East, they did it with a conviction in their own superiority. The majority of American involvement in the Middle East prior to World War I came not in the form of trade but in education, science, and humanitarian aid. American missionaries led the way. The first Protestant missions had arrived in 1819. Soon the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions dominated missionary enterprises. Missions were established in almost every country of the Middle East, and even though their efforts resulted in relatively few converts, missionaries helped establish hospitals, schools, and Western-style universities, such as Robert College in Istanbul (1863), the American University of Beirut (1866), and the American University of Cairo (1919).

After this long history of international economic, missionary, and cultural engagement, the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (1898–1902) marked a crucial turning point in American interventions abroad. In a war with Spain and then in a counterrevolutionary conflict in the Philippines, the United States expanded its global reach. Over the next two decades, the United States would become increasingly involved in international politics, particularly in Latin America. New conflicts and territorial problems forced Americans to confront the ideological elements of imperialism. Should the United States act as an empire? Or were foreign interventions and taking territory antithetical to its founding democratic ideals? What exactly would be the relationship between the United States and the territories it acquired? Could colonial subjects be successfully and safely transformed into American citizens? The Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars brought these questions, which had always lurked behind discussions of American expansion, out into the open.

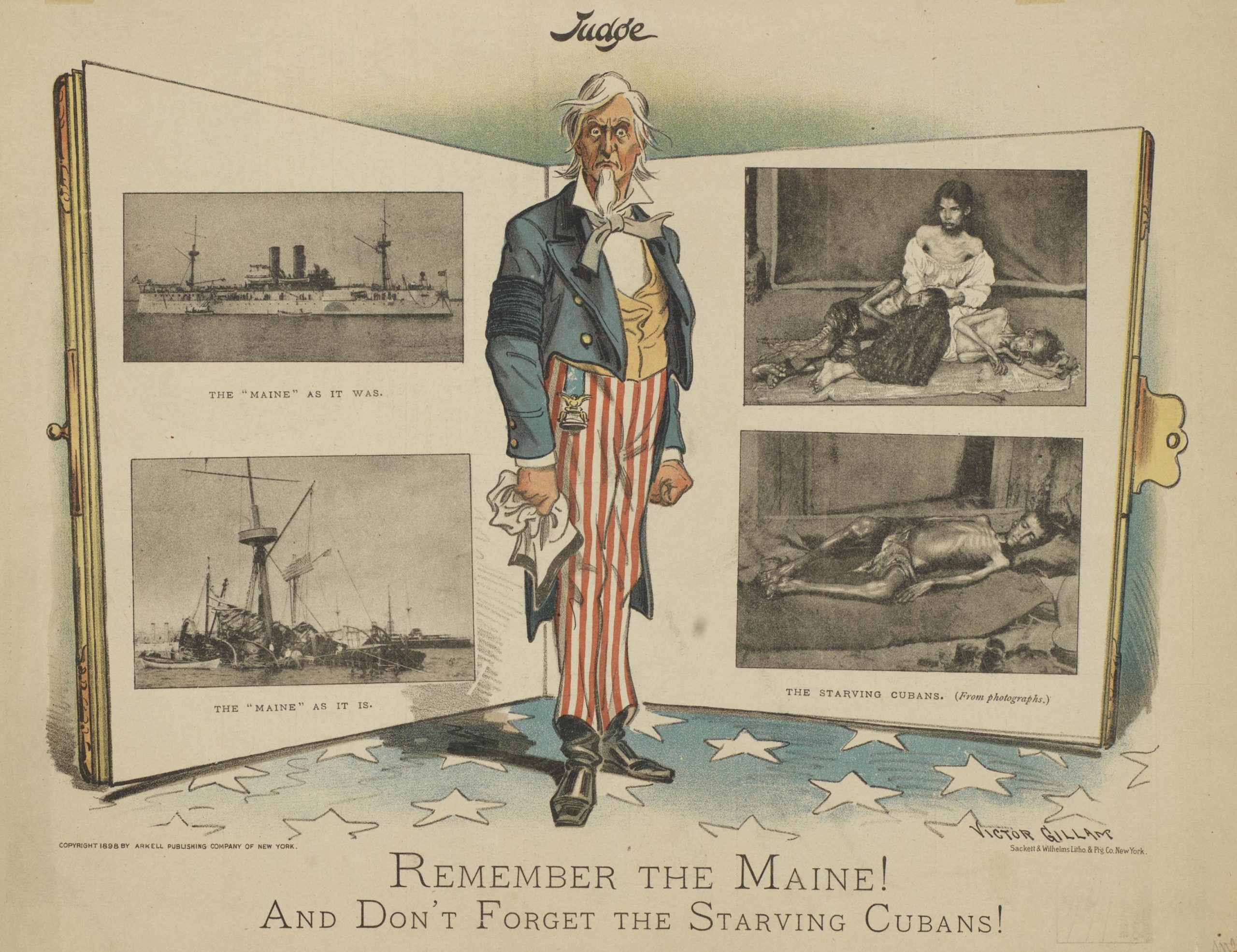

In 1898, Americans turned their attention southward to Cuba. The island’s revolution against the Spanish Empire had begun in 1895. By the winter of 1898, the Spanish had begun forcing Cubans living in certain cities to relocate to concentration camps. Prominent newspaper publishers sensationalized Spanish atrocities. While the U.S. government announced its wish to avoid armed conflict with Spain, President McKinley ordered the battleship Maine to Cuba in January 1898. After about two weeks in Havana harbor, a titanic explosion tore open the ship and killed three quarters of the crew of 354. A naval board of inquiry immediately began an investigation, but the loudest Americans had already decided that Spanish treachery was to blame. Capitalizing on the outrage, newspapers such as William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal called for war with Spain. Congress officially declared war on April 25.

Spain’s decaying military crumbled. In the Pacific, on May 1, the U.S. Navy engaged the Spanish fleet outside Manila and destroyed it easily. Two months later, American troops took Cuba’s San Juan Heights in what would become the most famous battle of the war, winning special accolades for Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders. Roosevelt had been the assistant secretary of the navy but had resigned his position in order to fight in the war. His well-publicized adventures in Cuba made him a national celebrity. The U.S. and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris in December. The terms of the treaty stipulated, among other things, that in addition to Cuban independence the United States would acquire Spain’s former holdings of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines.

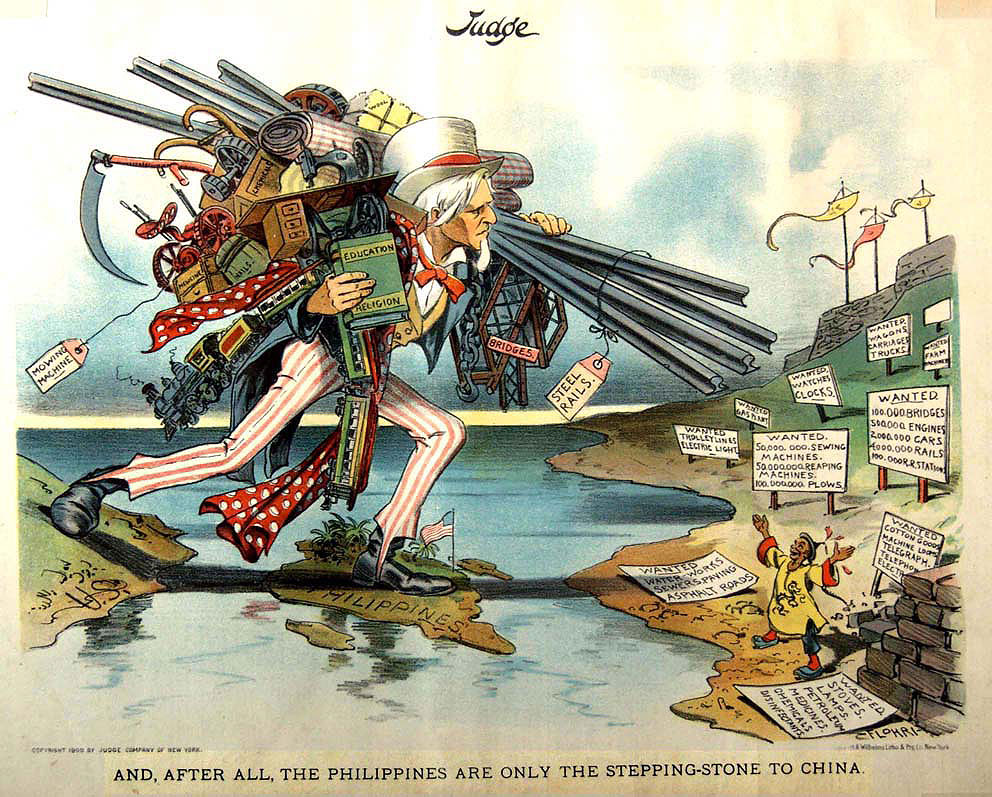

Although acquiring the Philippines had not been a goal of the war, the United States found itself in possession of a valuable foothold in the Pacific. At the urging of American businessmen who had overthrown the Hawaiian monarchy, the United States had annexed the Hawaiian Islands and their rich plantations in 1898. After the U.S. Navy’s defeat of the Spanish fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay, American and Philippine forces under the leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo met and the American leaders in the field promised to support the Filipino fight for independence, which like Cuba’s had begun long before the U.S. got involved. Debates about American imperialism continued against the backdrop of an upcoming presidential election. Emilio Aguinaldo was inaugurated as president of the First Philippine Republic in late January 1899; fighting between American and Philippine forces began in early February; and in April 1899, Congress ratified the 1898 Treaty of Paris, which gave Spain $20 million in exchange for the Philippine Islands. The United States rethought its promise to hand over the Philippines to the revolutionaries, and Aguinaldo began leading his guerrillas against their new adversary.

Seeing the Philippines as a gateway to Asia, President William McKinley issued a “Benevolent Assimilation Proclamation” in January 1899. Claiming its altruistic intentions and telling the Filipinos that they were not yet ready for the heavy responsibilities of self-government, the United States occupied the islands and from 1899 to 1902 launched a bloody series of attacks against Filipino insurrectionists that cost far more lives than the war with Spain. Under the leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo, Filipinos who had fought for freedom against the Spanish now fought against the very nation that had claimed to have liberated them from Spanish tyranny. The Philippines are an archipelago of over 7,000 islands, and President Aguinaldo waged a guerrilla war against the American invaders. Aguinaldo was captured in March 1901 and an occupation administration, with William H. Taft as the first governor-general (1901–1903), was established with military support. Although President Theodore Roosevelt declared the war to be over on July 4, 1902, resistance continued into the second decade of the twentieth century.

Questions for Discussion

- What is “Manifest Destiny”?

- How did the Guano Act set a precedent for later U.S. overseas actions?

- How were Americans convinced to support the Spanish-American War?

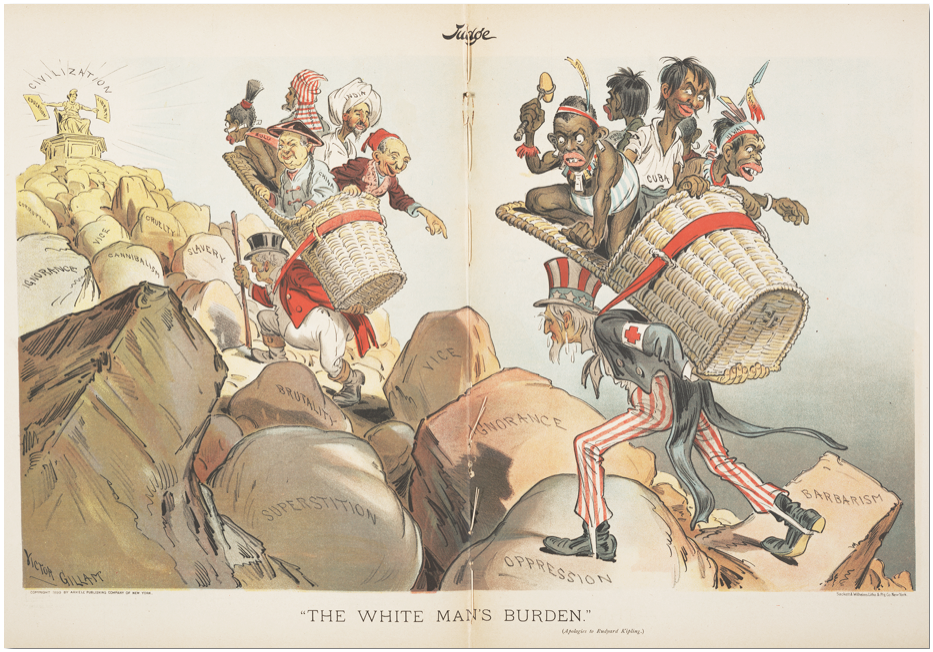

- What was the “White Man’s Burden”?

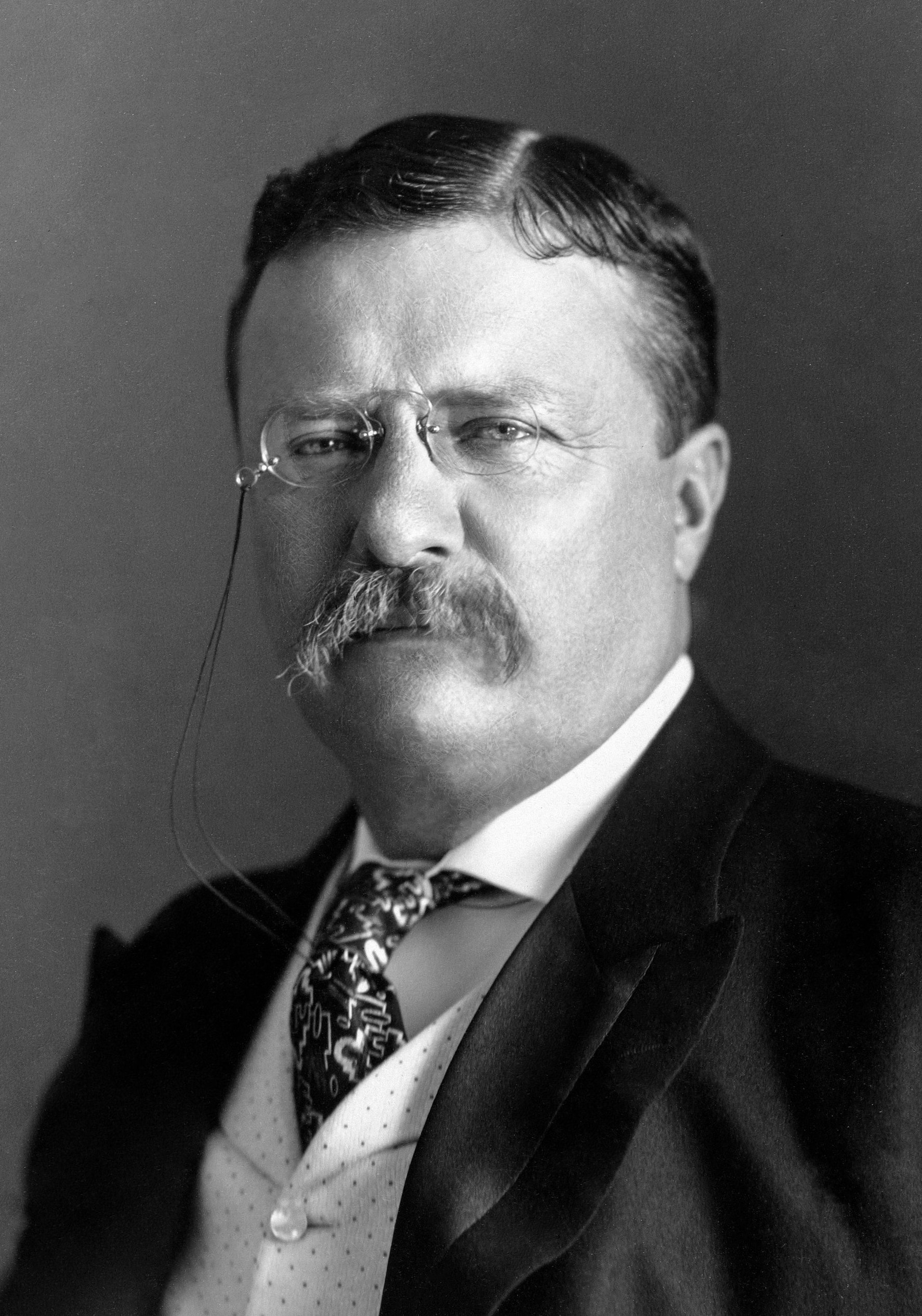

Theodore Roosevelt

Under the leadership of President Theodore Roosevelt, the United States entered the twentieth century ambitious to achieve global power by military might, territorial expansion, and economic influence. Though the Spanish-American War had been fought and the Philippine occupation had begun during the administration of William McKinley, Roosevelt, who became president when McKinley was assassinated in September 1901, was the most influential proponent of American imperialism at the turn of the century. Roosevelt’s emphasis on developing the American navy and on Latin America as a key strategic area of U.S. foreign policy had long-term consequences.

In return for Roosevelt’s support in the 1896 presidential election, McKinley had appointed Roosevelt as assistant secretary of the navy. Roosevelt supervised the construction of new battleships and new shipyards, all with the goal of projecting America’s power across the oceans. Roosevelt advocated for the annexation of Hawaii to prevent Japanese expansion and limit potential threats to the West Coast. Hawaii also had an excellent port for battleships at Pearl Harbor, and could be a fueling station on the way to pivotal markets in Asia. In an era of coal-powered steamships, naval power depended on access to coal depots placed strategically throughout the world.

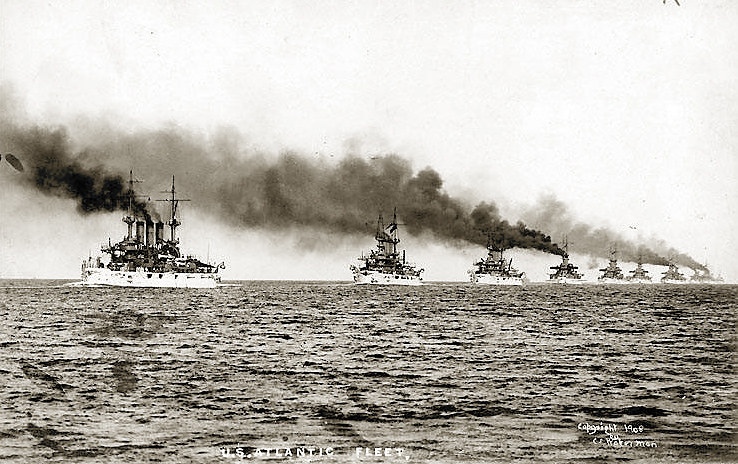

Roosevelt resigned his naval office in order to fight in Cuba. After winning headlines in the war, Roosevelt was rewarded by being selected to replace McKinley’s first vice president, Garret Hobart, who had died in office, in the 1900 election. When McKinley was assassinated and Roosevelt became president, he acted immediately to expand naval power. This included commissioning eleven battleships between 1904 and 1907. Alfred Thayer Mahan’s naval theories, described in his The Influence of Sea Power upon History, convinced Roosevelt that control of the sea required battleships and a “blue water” navy that could win decisive battles with rival fleets (Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany had also read Mahan’s book and had come to the same conclusions). As president, Roosevelt continued the policies he had established as assistant secretary of the navy and expanded the U.S. fleet. The Great White Fleet, sixteen all-white battleships, sailed around the world between 1907 and 1909, announcing America’s new power.

Roosevelt’s motto, “Speak softly and carry a big stick, and you will go far”, suggested that the persuasive power of the U.S. military could ensure U.S. hegemony over strategically important regions in the Western Hemisphere. Throughout his time in office, Roosevelt exerted U.S. control over Cuba (even after it gained formal independence in 1902) and Puerto Rico, and he deployed naval forces to enforce Panama’s independence from Colombia in 1901 in order to acquire a U.S. Canal Zone. A project to dig a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans had gone bankrupt, but Roosevelt’s government bought the assets of the canal company and engineered a revolution in Panama that delivered the necessary land. Later, Roosevelt issued the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904, proclaiming U.S. police power in the Caribbean. The doctrine as originally articulated by President James Monroe had said the United States would treat any military intervention in Latin America by a European power as a threat to American security. Roosevelt expanded it by declaring that the United States had the right to preemptive action through intervention in any Latin American nation in order to correct administrative and fiscal deficiencies that threatened the profits of U.S. businesses.

Roosevelt’s policy justified police actions in “dysfunctional” Caribbean and Latin American countries by U.S. Marines and naval forces that included the founding of a naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. U.S. police actions were not based on threats posed by other nations, but on requests for intervention from American businesses like the United Fruit Company, which dominated the banana trade. The term “banana republic” was coined by American author O. Henry in 1904 to describe small Latin American nations like Guatemala and Honduras that found themselves completely at the mercy of American businesses that could call on the U.S. military to control workers and replace governments that challenged their supremacy. In an approach known as gunboat diplomacy, naval forces and Marines would land in a national capital to protect American and Western personnel, seize control of the government, and dictate policies friendly to American business, such as the repayment of foreign loans or an end to efforts to redistribute land to poor farmers. For example, in 1905 Roosevelt sent the Marines to occupy the Dominican Republic and established financial supervision over the Dominican government. Imperialists framed such interventions as humanitarian. They celebrated white Anglo-Saxon societies as advanced civilizations, helping to uplift semi-civilized debtor nations in Latin America that lacked the discipline and self-control. Roosevelt preached that it was the “manly duty” of the United States to exercise police power in the Caribbean and spread the benefits of Anglo-Saxon civilization to inferior peoples. The president’s language contrasted debtor nations’ “impotence” with the United States’ civilizing influence, associating self-restraint and social stability with Anglo-Saxon manliness. The fact that Roosevelt’s rhetoric ignored reality was not noticed by many who were inspired by the vigor and bravado of his “bully pulpit”.

When military intervention was inconvenient, “Dollar diplomacy” offered a less costly method of empire. Washington worked with bankers to provide loans to Latin American nations in exchange for control over their national fiscal affairs. Presidents Taft and Wilson continued the practice during their own administrations. Lenders took advantage of the region’s need for cash and exacted punishing interest rates on massive loans, which were then sold off in pieces on the secondary bond market. American economic interests became threatened by the chronic instability of a region often plagued by mismanagement, civil wars, and military coups, which ironically had been caused by frequent U.S. interventions. Turnover in regimes interfered with the repayment of loans, as new governments often repudiated national debts they believed had been taken on by dictators selected by foreign companies, who had lined their own pockets rather than working for the people.

Though aggressive and a bully, Roosevelt insisted that dealing with the Latin American nations, he did not seek national glory or expansion of territory and believed that war should be a last resort. But Latin nations recognized that Roosevelt was speaking softly because he had already shown his big stick. According to Roosevelt, actions might be necessary to maintain “order and civilization.” Roosevelt had demonstrated his belief in using military power to protect national interests and spheres of influence. He also clearly believed that the American sphere included not only Hawaii and the Caribbean but also much of the Pacific. When Japanese victories over Russia threatened the regional balance of power, Roosevelt sponsored peace talks between Russian and Japanese leaders, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize in 1906.

Questions for Discussion

- What policies did Theodore Roosevelt justify with his ideas of the “strenuous life” and the “big stick”?

- What is a banana republic?

- Why was a shift to a “blue water” navy significant for American history?

Women and Imperialism

Debates over American imperialism revolved around more than just politics and economics and national self-interest. They also included notions of humanitarianism, morality, religion, and ideas of “civilization.” And they included significant participation by American women.

When commentators like Theodore Roosevelt spoke about America’s overseas ventures, they generally gave the impression that this was a strictly masculine enterprise. In Roosevelt’s mind, this was the ideal “strenuous life” for soldiers, sailors, government officials, explorers, and businessmen. But U.S. imperialism, which focused as much on economic and cultural influence as on military or political power, offered a range of opportunities for white, middle-class women. In addition to working as representatives of American businesses, women could serve as missionaries, teachers, and medical professionals. As artists and writers, women enthusiastically helped transmit ideas supporting imperialism. And the rhetoric of “civilization” that supported imperialism was itself a highly gendered concept. According to the racial theory of the day, humans progressed through stages of civilization in an orderly, linear fashion. Only Northern Europeans and Anglo-Saxon Americans had attained the highest level of civilization and had built an industrial economy and a gender division in which men and women had different but complementary roles. Social and technological progress had freed women of the burdens of physical labor (because raising children and managing a household weren’t considered work) and had elevated them to a position of moral and spiritual authority. White women had important roles to play in U.S. imperialism, both as symbols of the benefits of American civilization and as promoters of American values.

Civilization, while often cloaked in the language of morality and Christianity, was very much an economic concept. The stages of civilization outlined by racial theorists and social Darwinists were described by their economic character, progressing from hunter-gatherer to agricultural and then industrial societies. Producing and consuming industrial commodities was a key moment in the progress of primitive societies toward civilized life. Over the course of the nineteenth century, women had become closely associated with consumption, particularly of those commodities used in the domestic sphere. By using consumer products bought from American companies, foreigners could live the lifestyle and potentially absorb the virtues of American civilization.

In some ways, women’s support of imperialism was an extension of activities many of them were already engaged in as reformers among working-class, immigrant, and Native American communities in the United States. Many white women felt that they had a duty to spread the benefits of Christian civilization to those less fortunate than themselves. American overseas ventures expanded the scope of these activities. Literally, with the geographical range of possibilities encompassing practically the entire globe, and figuratively, with imperialism significantly raising the stakes of women’s work. No longer only responsible for shaping the next generation of American citizens, white women now believed they had a crucial role to play in the expansion of civilization itself. They would help determine whether civilization would continue to progress.

Of course, not all women were active supporters of U.S. imperialism. Many actively opposed it. Although many prominent public voices against imperialism were male, women made up a large proportion of the membership of organizations like the Anti-Imperialist League. For white women like Jane Addams and Josephine Shaw Lowell, anti-imperialist activism was an outgrowth of their work opposing violence and supporting democracy. Black female activists, meanwhile, generally viewed imperialism as another form of racial violence and drew parallels between the treatments of African Americans at home and, for example, Filipinos abroad. Indeed, Ida B. Wells, a journalist and co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.), viewed her anti-lynching campaign as anti-imperialist activism.

Questions for Discussion

- How were middle-class, white women symbols of American culture?

- Why did female activists like Jane Addams and Ida B. Wells oppose imperialism?

Immigration Again

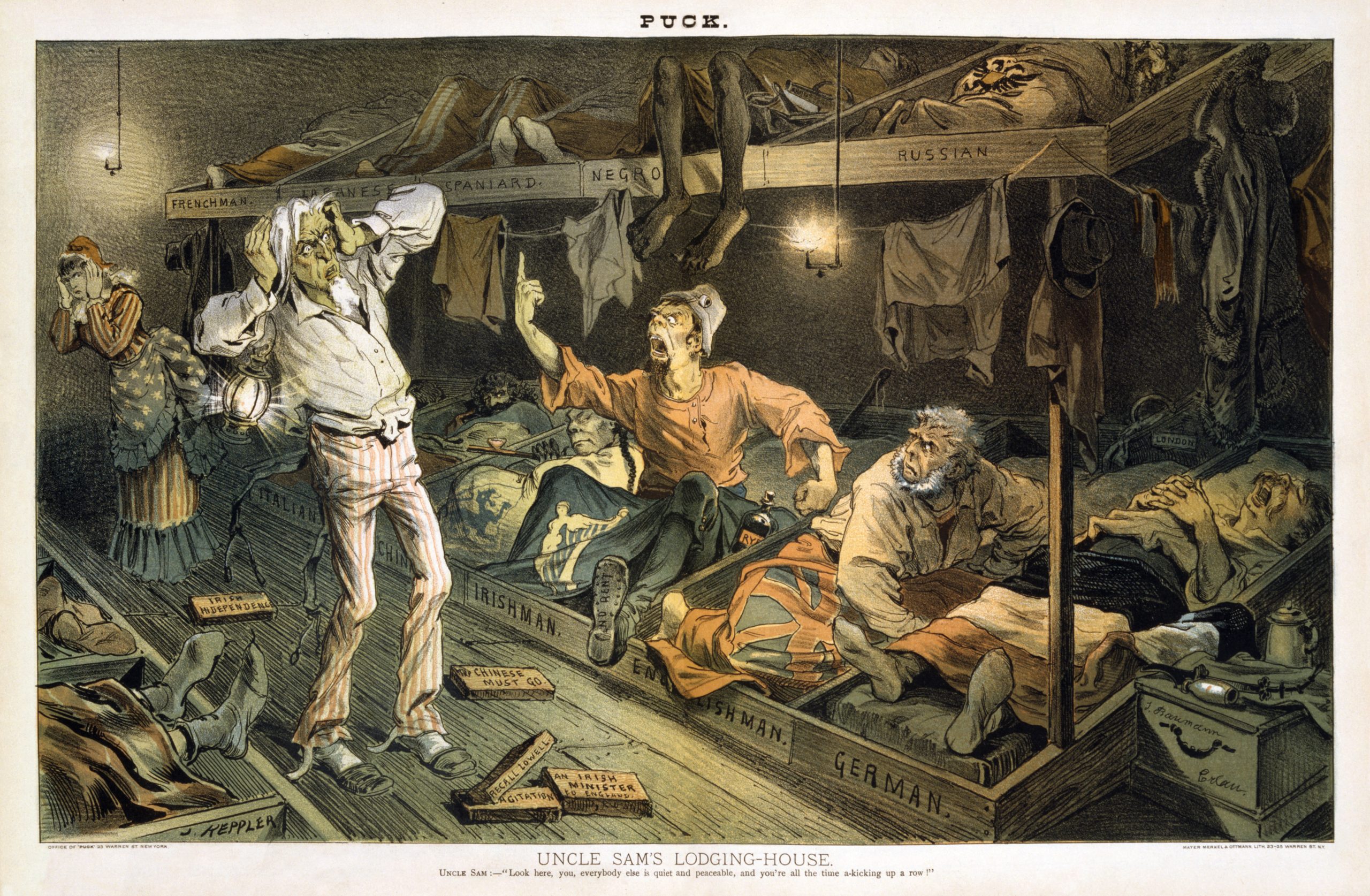

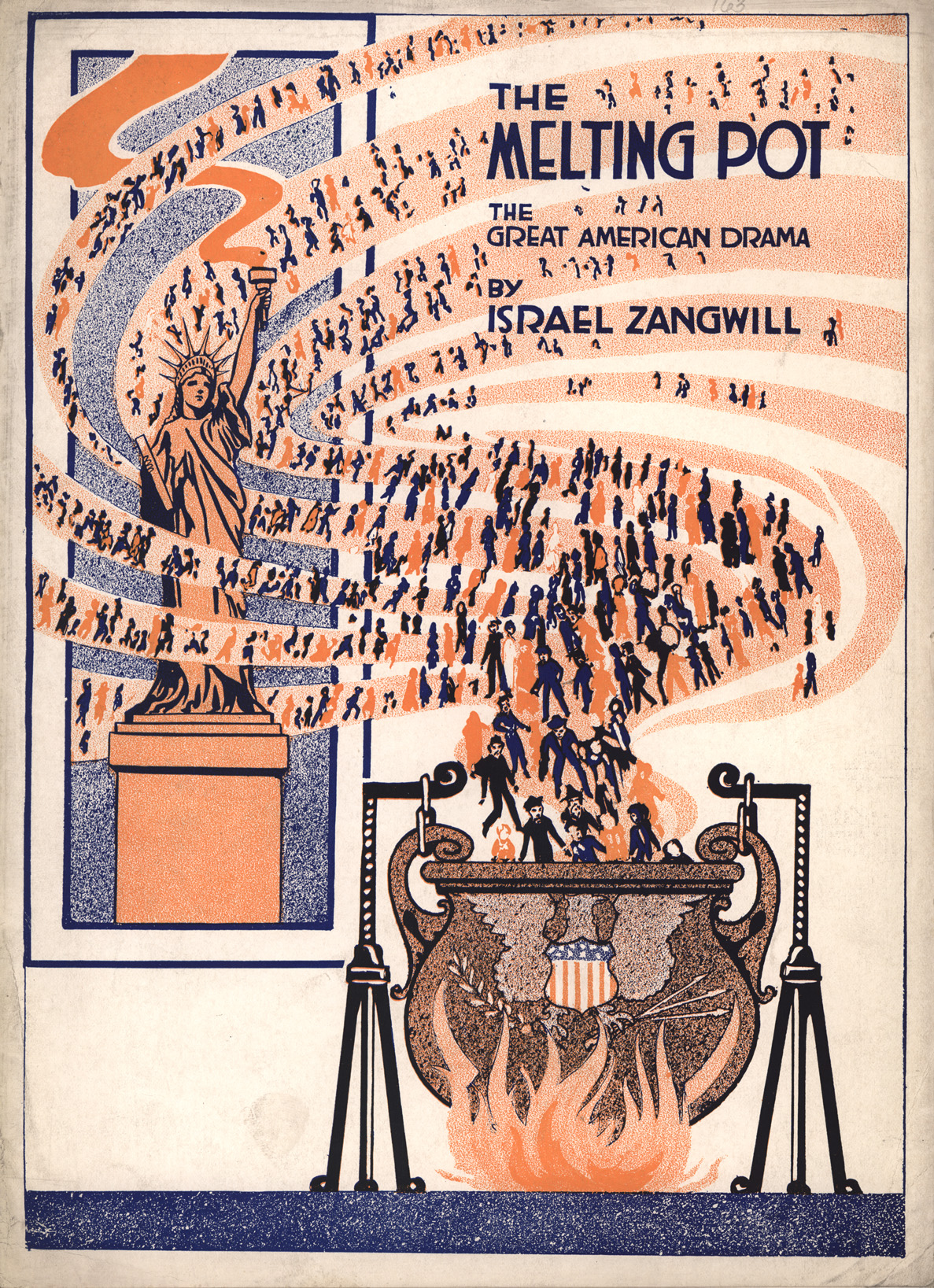

For Americans at the turn of the century, industrialization, imperialism, and immigration were all linked. Imperialism had at its core a desire for markets for American goods, and those goods were increasingly manufactured by immigrant labor. This sense of growing dependence on “others” as both producers and consumers, along with doubts about their ability to assimilate into the mainstream of white, Protestant American society, caused a great deal of anxiety among native-born Americans.

Between 1870 and 1920, over twenty-five million immigrants arrived in the United States. By the turn of the twentieth century, new groups such as Italians, Poles, and Eastern European Jews made up a larger percentage of the arrivals while Irish and German immigrant numbers began to dwindle. Although the growing U.S. economy needed large numbers of immigrant workers for its factories and mills and corporations supported immigration to keep wages low, many Americans resented the arrival of so many immigrants. Nativists felt that the new arrivals were unfit for American democracy. Others (often earlier immigrants themselves) worried that the arrival of even more immigrants would result in fewer jobs and lower wages. Such fears had resulted in anti-Chinese agitation on the West Coast leading to the Exclusion Act of 1882. Still others worried that immigrants brought with them radical ideas such as socialism and communism. These fears multiplied after the Chicago Haymarket incident in 1886, in which immigrant anarchists were among those accused of killing and injuring police officers in a bomb blast.

Since the colonial period, East Coast states had regulated immigration through passenger laws that prohibited the landing of destitute foreigners. State-level control of pauper immigration developed into federal policy in the early 1880s. In August 1882, Congress passed the Immigration Act, denying admission to people who were not able to support themselves, to people with mental illnesses, and to convicted criminals. In 1885, responding to American workers’ complaints about cheap immigrant labor, Congress added foreign workers migrating under labor contracts with American employers to the list of excludable people. Six years later, the federal government included people who seemed likely to become wards of the state, people with contagious diseases, and polygamists, and made all the groups of excludable people deportable. In 1903, those who would pose ideological threats, such as anarchists and socialists, also became the subject of new immigration restrictions.

Most opponents of immigration were responding to the shifting demographics of American immigration. The regions sending the most people to America had shifted from northern and western Europe to southern and eastern Europe and Asia. The “new immigrants” were poorer, spoke languages other than English, and were likely Catholic or Jewish. White Protestant Americans regarded them as inferior and American immigration policy began to reflect more explicit prejudice than ever before. Increased immigration of Italians, Jews, Slavs, and Greeks, led directly to calls for tighter restrictions. In 1907, entry of Japanese laborers was suspended when the American and Japanese governments reached the so-called Gentlemen’s Agreement, under which Japan would stop issuing passports to working-class emigrants. In 1911, the U.S. Immigration Commission highlighted the impossibility of incorporating these “new immigrants” into American society, asserting that they were the causes of rising social problems in America, such as poverty, crime, prostitution, and political radicalism.

The experience of Catholic immigrants shows the challenges immigrant groups faced in the United States. By 1900, Catholicism in the United States had grown from 1 percent of the population a century earlier to the largest religious denomination in America (though still outnumbered by Protestants as a whole). But the Church and its members remained an “outsider” religion in a nation that continued to see itself as culturally and religiously Protestant. Torrents of anti-Catholic literature and scandalous rumors maligned Catholics. Many Protestants doubted whether Catholics could ever make loyal Americans, since they supposedly owed their primary allegiance to the pope. But Catholics faced problems amongst themselves as well. Beginning in the 1830s, Catholic immigration to the United States had exploded with the arrival of Irish and German immigrants in the 1840s. Later Catholic arrivals from Italy, Poland, and Eastern Europe chafed at Irish dominance over the Church hierarchy. Mexican American Catholics expressed similar frustrations. Could all these different Catholics remain part of the same Church? Some bishops advocated rapid assimilation into the English-speaking mainstream. More conservative clergy cautioned against assimilation, seeing ethnic parishes as an effective strategy protecting immigrant communities. They worried that Protestants would use public schools to attack the Catholic faith. The American encounter with Catholicism shows the tense relationship between native-born and foreign-born Americans, and highlights ideas Americans used to situate themselves in a larger world, a world of empire and immigrants.

Questions for Discussion

- Why were southern and eastern Europeans and Asians less desirable immigrants in the eyes of many Americans?

- What were the main objections to Catholic immigration?

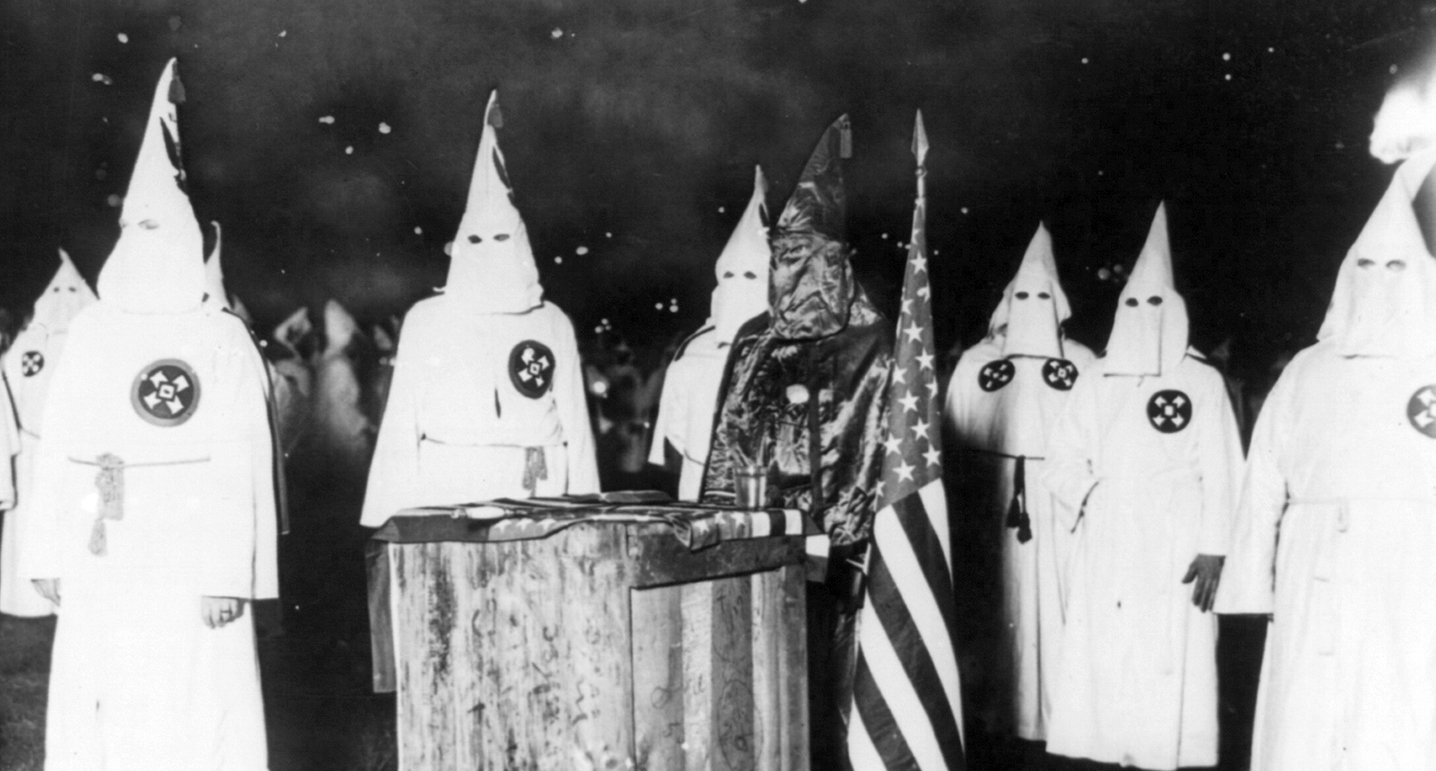

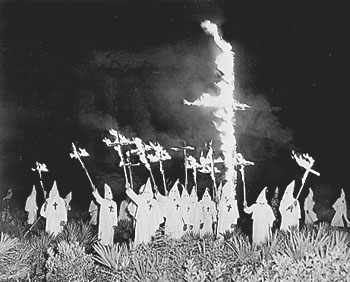

Racism and the New South

When Reconstruction had attempted to grant freedpeople full citizenship rights, whites had lashed out in fear, anger, and resentment. Southern whites resisted not only in organized terrorist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan but in political corruption, economic exploitation, and violent intimidation. When Reconstruction ended, whites took back control of state and local governments and used their reclaimed power to disenfranchise African Americans and pass “Jim Crow” laws segregating schools, transportation, employment, and public and private facilities. And nothing so forcefully continued the barbaric southern past than the wave of lynchings that washed across the South. Whether for actual crimes or fabricated crimes or for no crimes at all, white mobs murdered roughly five thousand African Americans between the 1880s and the 1950s.

Lynching, the illegal hanging of victims by angry mobs, was not just murder. Many victims were not simply hanged: they were terrorized, tortured, mutilated, burned alive, and shot. Southern lynchings often became public spectacles attended by thousands of eager spectators. Rail lines ran special cars to accommodate the rush of participants. Vendors sold keepsakes. Perpetrators posed for photos and collected mementos. One notorious example occurred in Georgia in 1899. Accused of killing his white employer and raping the man’s wife, twenty-four-year old Sam Hose was taken by a mob from the Newnan town jail where he was being held before trial. Word of the impending lynching quickly spread and specially chartered passenger trains brought thousands of visitors from Atlanta to witness the lynching. Members of the mob tortured Hose for about an hour. They sliced off the young man’s ears, fingers, genitals, and cut the skin off his face as he screamed in agony. Then they poured a can of kerosene over his body, burned him alive, and sold his body parts as souvenirs.

At the height of Southern lynching, in the last years of the nineteenth century, white southerners murdered two to three African Americans every week. Lynchings were most frequent in the Cotton Belt of the Lower South, where southern blacks were most numerous and where most worked as tenant farmers and field hands on the cotton farms of white landowners. From 1880 to 1930, Mississippi lynch mobs killed over five hundred African Americans; Georgia mobs murdered more than four hundred. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, prominent southerners openly supported lynching, arguing that it was a necessary evil to punish black rapists and deter others. The supposed danger of sexual assault of white women by black men was used for generations as an excuse for white violence. In the late 1890s, Georgia newspaper columnist and noted women’s rights activist Rebecca Latimer Felton (who would later become the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate) endorsed the killings. She said, “If it takes lynching to protect women’s dearest possession from drunken, ravening beasts, then I say lynch a thousand a week.” Felton praised the killing of Sam Hose, saying he had deserved less sympathy than a rabid dog. When opponents argued that lynching violated victims’ constitutional rights, South Carolina governor Coleman Blease angrily responded, “Whenever the Constitution comes between me and the virtue of the white women of South Carolina, I say to hell with the Constitution.”

But just how to circumvent the Constitution was an ongoing problem for white supremacists. The Fourteenth Amendment had promised equal protection under the law and the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited states from denying any citizen the right to vote on the basis of race. In 1890, a Mississippi state newspaper called on politicians to devise “some legal defensible substitute for the abhorrent and evil methods on which white supremacy lies.” The state’s Democratic Party responded with a new state constitution designed to purge “corruption” at the ballot box by disenfranchising blacks. The state first established a poll tax, which required voters to pay for the privilege of voting. Second, it stripped suffrage from those convicted of petty crimes most common among African Americans. Next, the state required voters to pass a literacy test. The disenfranchisement laws effectively moved electoral conflict from the ballot box, where public attention was greatest, to the voting registrar, where party officials were able to deny the ballot without the appearance of fraud. This technique was so successful that it has continued to be practiced to the present.

Between 1895 and 1908, the rest of the states in the South approved new constitutions including these disenfranchisement tools. Six southern states also added a grandfather clause, which automatically enfranchised anyone whose grandfather had been eligible to vote in 1867. This ensured that poor, illiterate whites who would have been otherwise excluded by poll taxes or literacy tests would still be eligible. Finally, each southern state adopted an all-white primary and excluded blacks from the only political contests that mattered across much of the South. These white supremacist tools did their work well. In 1900 Alabama had 121,159 literate black men of voting age. Only 3,742 were registered to vote. 130,000 black Louisiana voters had voted in the contentious election of 1896. Only 5,320 voted in 1900. While African Americans were clearly the target of these laws, some whites were disenfranchised as well. But most southern whites considered this a price worth paying to prevent the black vote that “corrupted” the region’s elections.

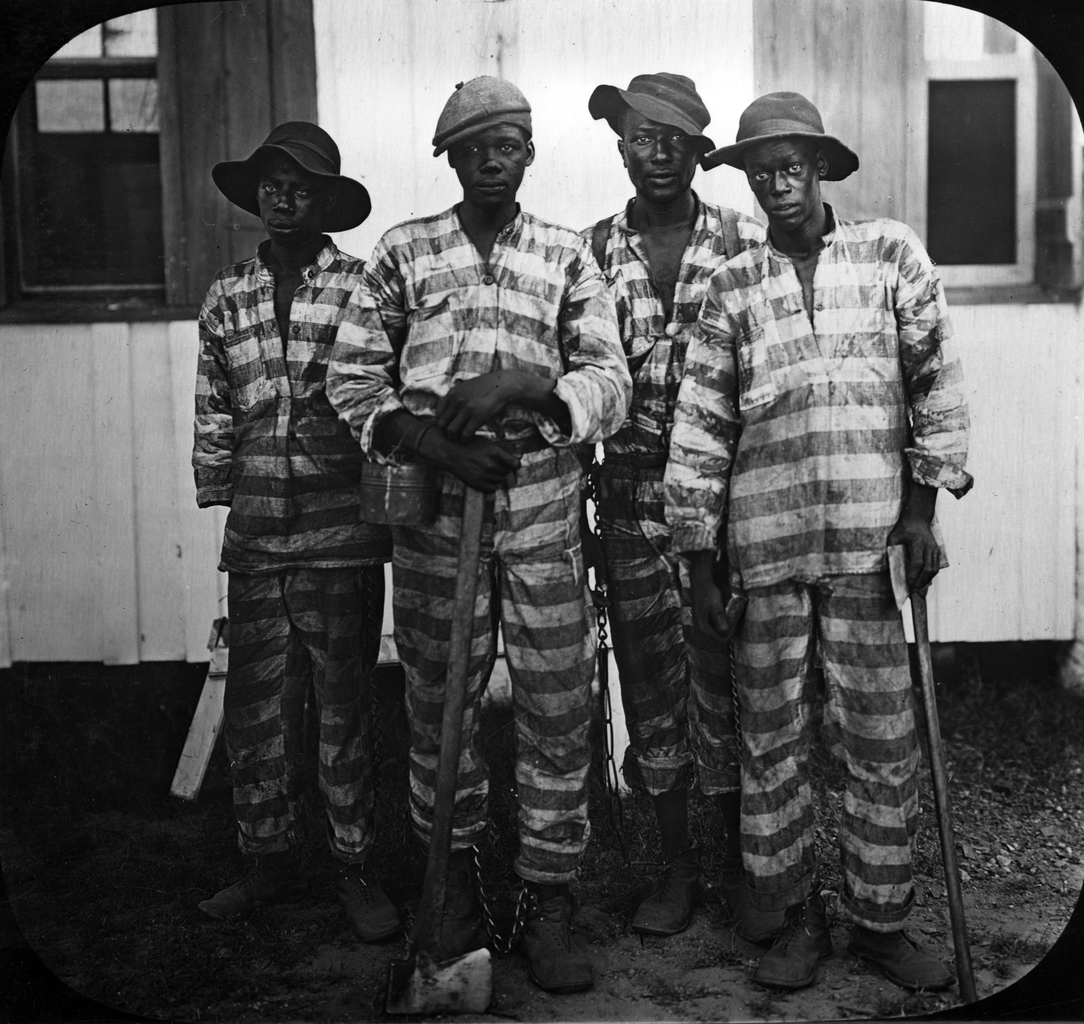

At the same time that the South’s Democratic leaders were adopting the tools to disenfranchise the region’s black voters, these same legislatures were constructing an elaborate system of racial segregation. Crop lien and convict lease systems were important legal tools of racial control in the rural South. Maintaining white supremacy in the city, however, was a more difficult matter. As railroad networks and cities expanded, so did the anonymity and freedom of southern blacks. Southern cities were becoming a center of black middle-class life that threatened racial hierarchies. White southerners relied on segregation to maintain white supremacy in restaurants, theaters, public restrooms, schools, water fountains, train cars, and hospitals.

Segregation violated the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment. To protect white supremacy, the Supreme Court ruled in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) that the Fourteenth Amendment only prevented discrimination directly by states. It did not prevent segregation imposed by individuals, businesses, or other entities. Southern states exploited this interpretation by segregating railroad cars in 1888. Then, in a case that reached the Supreme Court in 1896, New Orleans resident Homer Plessy challenged Louisiana’s segregation of streetcars. The Supreme Court ruled against Plessy and established the legal principle of separate but equal. The law said racially segregated facilities were acceptable as long as they were equivalent. In reality this was almost never the case. The Supreme Court defended its decision with language that echoed the racist assumptions of the day. “If one race be inferior to the other socially,” the justices explained, “the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” Justice John Harlan, the lone dissenter, countered, “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” Harlan went on to warn that the court’s decision would “permit the seeds of race hatred to be planted under the sanction of law.” Ignoring Harlan’s warning, whites segregated public spaces throughout the South.

Questions for Discussion

- How did white people justify lynching?

- Why were Southern states so intent on denying African Americans the vote?

- How was prison labor like a continuation of slavery? What effects do similar practices have in the present?

- What was the point of the Plessy decision and of John Harlan’s dissent?

Segregation was built on the Supreme Court’s judgment of “separate but equal.” Southern whites erected a defense of white supremacy that would last nearly sixty years. The South rejected black citizenship and limited black social and cultural life to segregated spaces. African Americans lived divided lives, acting the part whites demanded of them in public while maintaining their own world apart from whites. But many black Americans of the Progressive Era resisted their separation from the mainstream of American culture. Activists such as Ida Wells worked against southern lynching, while Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois offered competing visions of the possibilities of African American life. Washington and Du Bois were activists with extremely different life experiences, and this difference resulted in years of intense rivalry as they each advocated their distinct strategies for the uplifting of black Americans.

Born in Virginia in 1856, Booker Taliaferro Washington was subjected to slavery early in life. But Washington also developed an insatiable thirst to learn. After working his way through the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, Washington established the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Washington hoped that Tuskegee’s contribution to black life would come through industrial education and vocational training. He believed that attaining practical skills would help African Americans reach economic independence and develop self-worth and pride of accomplishment, even while living within the restrictions of Jim Crow. Washington poured his life into Tuskegee and led the institute for over thirty years, By his death in 1915 Tuskegee’s endowment had grown from a starting grant of $2,000 to over $1.5 million, which insured its survival to the present as Tuskegee University.

Washington was both praised as a race leader and criticized as an accommodationist to America’s unjust racial hierarchy. He argued that blacks should focus on education and entrepreneurship instead of directly challenging segregation and Jim Crow. In addition to founding and leading Tuskegee, Washington published a handful of influential books, including the autobiography Up from Slavery (1901). Washington was also active in black journalism, working to fund and support black newspaper publications, many of which sought to counter W.E.B. Du Bois’s growing influence.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in western Massachusetts in 1868, the child of free black parents. He had his first experience of the South when he went to Fisk University in Nashville Tennessee. Du Bois’ time in the South left a distinct impression that would lead him to study what he called the “Negro problem,” the racial and economic discrimination that Du Bois predicted would be the problem of the twentieth century. After Fisk, Du Bois attended Harvard, crossed the Atlantic to do graduate work in Germany, and returning to Harvard in 1895, became the first black American to receive a PhD there.

Du Bois became one of America’s foremost intellectual leaders on questions of social justice. He taught at Wilberforce University in Ohio and Atlanta University in Georgia and wrote about the history of the transatlantic slave trade and black life in urban Philadelphia. The most well-known of his works included The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and Darkwater (1920). Du Bois supported black civil rights with the Niagara Movement and the N.A.A.C.P., which he helped found in 1909. Du Bois worked from 1909 to 1934 as editor of The Crisis, one of America’s leading black publications. Du Bois attacked what he considered Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist approach to civil rights and urged black Americans to concede to nothing, to make no compromises and advocate for equal rights under the law. Du Bois said Washington had “implicitly abandoned all political and social rights”, but added, “I never thought Washington was a bad man…I believed him to be sincere, though wrong.”

With white supremacy secured, prominent white southerners looked outward for support. New South boosters hoped to confront post-Reconstruction uncertainties by rebuilding the South’s economy and convincing the nation that the South could be more than an economically backward, race-obsessed backwater. To support this goal, they began to retell the history of the recent past. A kind of civic religion known as the “Lost Cause” glorified the Confederacy and romanticized the Old South. White southerners looked forward to a segregated future while simultaneously imagining a past inhabited by contented and loyal slaves, benevolent and generous masters, chivalric and honorable men, and pure and faithful southern belles. Secession, they began to claim, had not been about protecting the institution of slavery. Confederate soldiers had fought only for home and honor, not for the continued ownership of human beings. The New South, then, would be built physically with new technologies, new investments, and new industries, but would celebrate the political and social customs of the Old South.

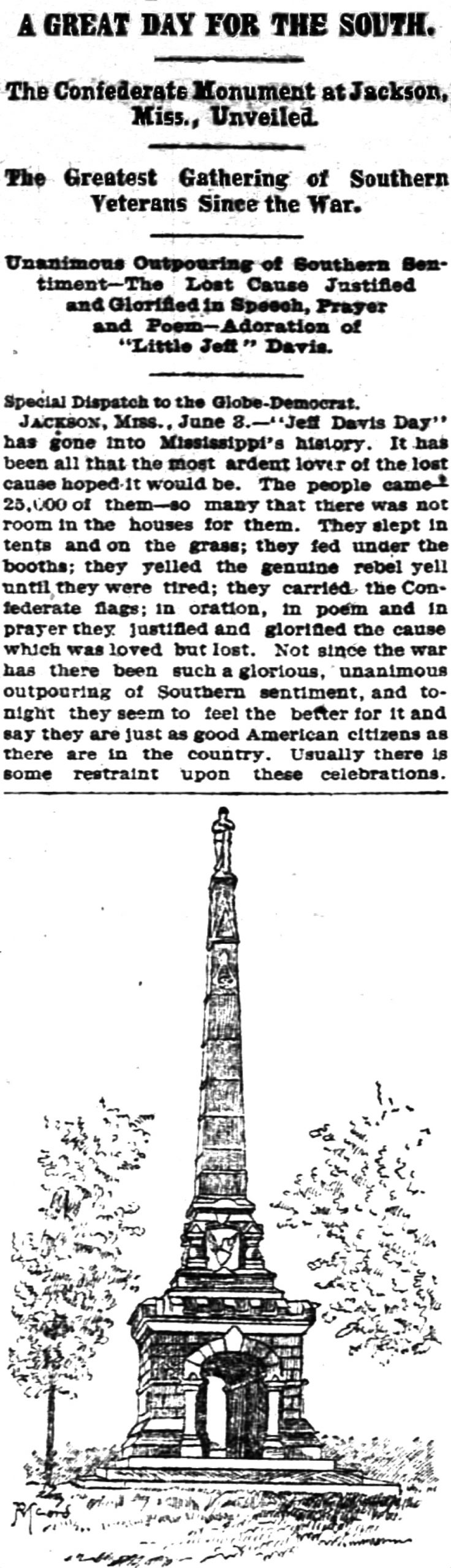

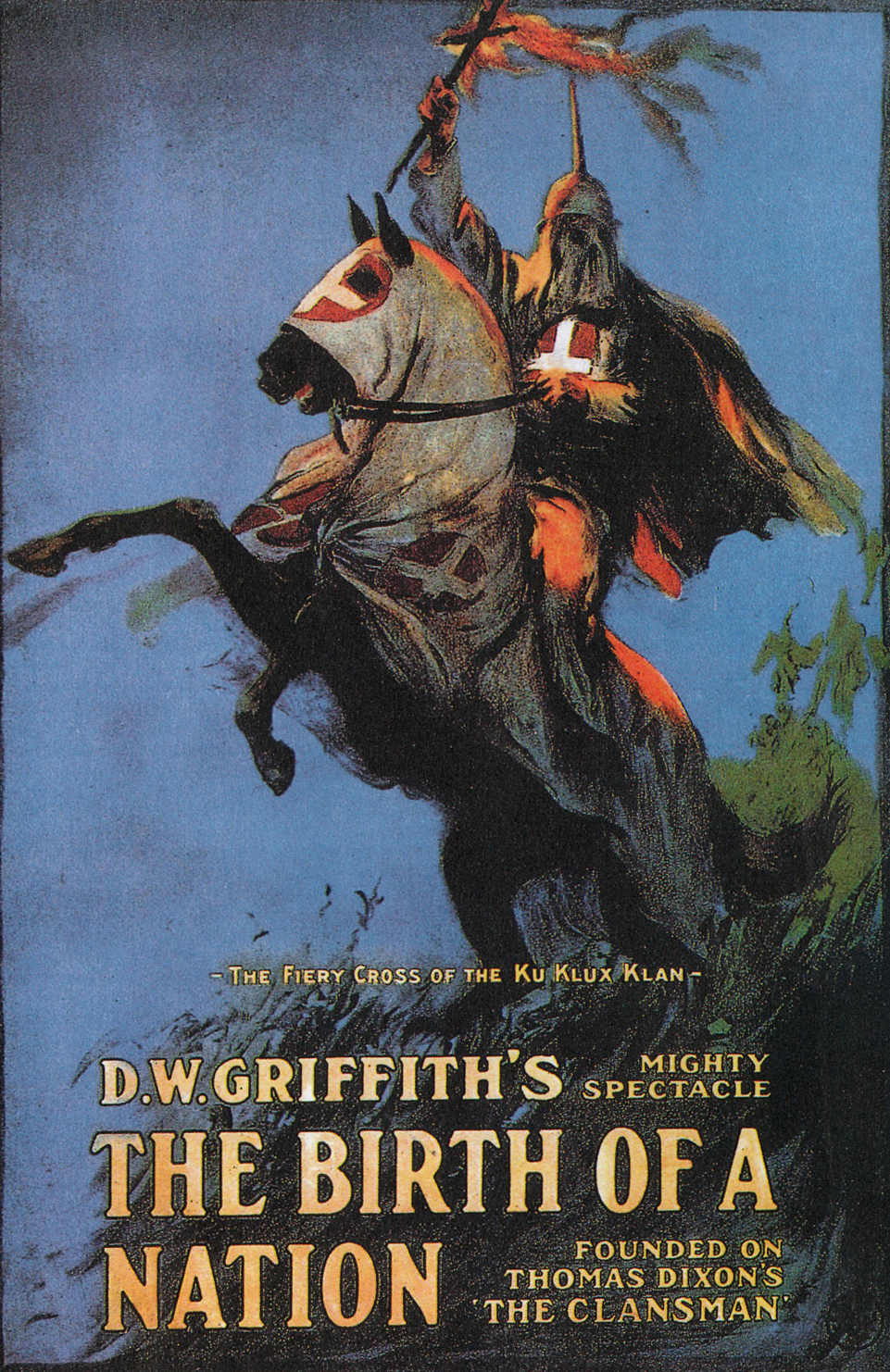

Lost Cause champions dominated the South. Women’s groups such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy joined with Confederate veterans to preserve a pro-Confederate past. They built Confederate monuments and celebrated Confederate veterans on Memorial Day. Across the South, towns erected statues of General Robert E. Lee and other Confederate figures. By the turn of the twentieth century, the idealized Lost Cause past was entrenched not only in the South but had gained credibility throughout the country. A generation of historians, from about 1900 to the 1930s, wrote histories that supported the Southern perspective. And in 1905, North Carolinian Thomas F. Dixon published a novel, The Clansman, which depicted the Ku Klux Klan as heroic defenders of the South against the corruption of African American and Northern “carpetbag” misrule during Reconstruction. In 1915, acclaimed film director David W. Griffith adapted Dixon’s novel into the groundbreaking blockbuster film, Birth of a Nation. The romanticized version of the antebellum South and the distortion of Reconstruction dominated popular imagination and the film almost singlehandedly rejuvenated the Ku Klux Klan.

While Lost Cause defenders mythologized their past, New South boosters struggled to wrench the South into the modern world. Railroads, roads, and manufacturing became their focus. The region attracted industries like textiles, tobacco, furniture, and steel. While agriculture, especially cotton production, remained the mainstay of the region’s economy, these new industries provided new wealth for owners, new investments for the region, and new opportunities for the exploding number of landless farmers to finally flee the land. Industries offered low-paying jobs but also opportunity for rural poor who could no longer sustain themselves through subsistence farming. Men, women, and children all moved into wage work. At the turn of the twentieth century, nearly one fourth of southern mill workers were children aged six to sixteen.

Questions for Discussion

- Compare the different approaches of W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. What points did they agree on? What did they disagree on?

- What is the central argument of the “Lost Cause” revision of Southern history?

Primary Sources

Henry Grady on the New South (1886)

Atlanta newspaperman and apostle of the “New South,” Henry Grady, won national recognition for his December 21, 1886 speech to the New England Society in New York City.

Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden” (1899)

As the United States waged war against Filipino insurgents, the British writer and poet Rudyard Kipling urged the Americans to take up “the white man’s burden.”

James D. Phelan, “Why the Chinese Should Be Excluded” (1901)

James D. Phelan, the mayor of San Francisco, penned the following article to drum up support for the extension of laws prohibiting Chinese immigration.

William James on “The Philippine Question” (1903)

Many Americans opposed imperialist actions. Here, the philosopher William James explains his opposition in the light of history.

Booker T. Washington & W.E.B. DuBois on Black Progress (1895, 1903)

Booker T. Washington, born a slave in Virginia in 1856, founded the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1881 and became a leading advocate of African American progress. Introduced as “a representative of Negro enterprise and Negro civilization,” Washington delivered the following remarks, sometimes called the “Atlanta Compromise” speech, at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895.

Mark Twain, “The War Prayer” (ca.1904-5)

The American writer Mark Twain wrote the following satire in the glow of America’s imperial interventions.

References:

This chapter was written by Dan Allosso, based on two chapters from The American Yawp. Those chapters were edited by Lauren Brand (Chapter 17) and Ellen Adams and Amy Kohout (Chapter 19), with content contributions by Lauren Brand, Carole Butcher, Josh Garrett-Davis, Tracey Hanshew, Nick Roland, David Schley, Emma Teitelman, Alyce Webb, Ellen Adams, Alvita Akiboh, Simon Balto, Jacob Betz, Tizoc Chavez, Morgan Deane, Dan Du, Hidetaka Hirota, Amy Kohout, Jose Juan Perez Melendez, Erik Moore, and Gregory Moore.

Recommended Reading on Empire:

- Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Brooks, Charlotte. Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Gabaccia, Donna. Foreign Relations: American Immigration in Global Perspective. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Greene, Julie. The Canal Builders: Making America’s Empire at the Panama Canal. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Guglielmo, Thomas A. White on Arrival: Italians, Race, Color, and Power in Chicago, 1890–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Harris, Susan K. God’s Arbiters: Americans and the Philippines, 1898–1902. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988.

- Hirota, Hidetaka. Expelling the Poor: Atlantic Seaboard States and the Nineteenth-Century Origins of American Immigration Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Hoganson, Kristin. Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

- Hoganson, Kristin L. Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign People at Home and Abroad, 1876–1917. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

- Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Kaplan, Amy. The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Kramer, Paul A. The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Lafeber, Walter. The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1963.

- Lears, T. J. Jackson. Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877–1920. New York: HarperCollins, 2009.

- Linn, Brian McAllister. The Philippine War, 1899–1902. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000.

- Love, Eric T. L. Race over Empire: Racism and U.S. Imperialism, 1865–1900. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

- Pascoe, Peggy. What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Perez, Louis A., Jr. The War of 1898: The United States and Cuba in History and Historiography. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Renda, Mary. Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of US Imperialism, 1915–40. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Rosenberg, Emily S. Spreading the American Dream: American Economic and Cultural Expansion, 1890–1945. New York: Hill and Wang, 1982.

- Silbey, David. A War of Frontier and Empire: The Philippine-American War, 1899–1902. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007.

- Wexler, Laura. Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of US Imperialism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- Williams, William Appleman. The Tragedy of American Diplomacy, 50th Anniversary Edition. New York: Norton, 2009 [1959].

Media Attributions

- West_minstrel_jubilee_rough_riders © Strobridge Lith Co is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 28668v © Louis Dalrymple is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Putting_his_foot_down © J. S. Pughe is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Flohri_cartoon_about_the_Philippines_as_a_bridge_to_China © Emil Flohri is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Remember_the_Maine!_And_Don’t_Forget_the_Starving_Cubans!_-_Victor_Gillam_(cropped) © Victor Gillam is licensed under a Public Domain license

- _The_White_Man’s_Burden__Judge_1899 © Victor Gillam is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Emilio_Aguinaldo_boarding_USS_Vicksburg © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1920px-President_Roosevelt_-_Pach_Bros © Pach Bros. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Us-atlantic-fleet-1907 © C.E. Waterman is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Street_in_Belize_-_British_Honduras © Henry Robertson Blaney is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Roosevelt_safari_elephant © Edward Van Altena is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Joseph_F._Keppler_-_Uncle_Sam’s_lodging-house © Joseph Ferdinand Keppler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- TheMeltingpot1 © Israel Zangwill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- KKK_night_rally_in_Chicago_c1920_cph.3b12355 © Underwood & Underwood is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Reb_Felton-Geo_Senate © National Photo Company is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Klan-in-gainesville © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Convicts_Leased_to_Harvest_Timber © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1920px-Booker_T._Washington_by_Francis_Benjamin_Johnston,_c._1895 © Frances Benjamin Johnston is licensed under a Public Domain license

- History_class_at_Tuskegee © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Motto_web_dubois_original © Addison N. Scurlock is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Newspaper_clipping_and_image_about_Jackson_MS_Confederate_monument_1891 © St. Louis (Missouri) Globe-Democrat is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Birth_of_a_Nation_theatrical_poster © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license