4 Cities and Progressives

One of the most prominent changes in American life in the nineteenth century was the growth of cities and of the number and percentage of Americans living in them. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, for example, Boston had a population of 25,000. New York City was not much bigger, with only 60,000 and Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles had not even been established. By 1850, Boston had 137,000 residents, New York 515,000, Chicago 30,000, San Francisco 21,000, and Los Angeles 1,600. By 1900, although only forty percent of Americans lived in cities or large towns, Boston had grown to 561,000, New York to 3.4 million, Chicago to 1.7 million, San Francisco to 343,000, and Los Angeles had 102,000.

We have seen previously that many of America’s new city-dwellers had migrated from the countryside in search of work in new industries. Much of the U.S. population growth of the first half of the nineteenth century was due to the extremely high birth rates of the generations just before and after the American Revolution, when the average family had well over four children and the population actually doubled every generation. After the War of 1812, many more were immigrants from foreign countries. Some of the first migrations of large groups followed the Irish Famine in 1845 and a series of failed socialist revolutions in the German states in 1848.

Although historical demographics have documented the rapid growth of American cities, it is important to understand that the addition of thousands of new residents measured from one U.S. Census to the next, every ten years, was just the tip of the iceberg. City populations not only increased rapidly, they changed even more quickly. During the decade from 1880 to 1890, for example, the population of Boston increased by about 85,000 people, from 363,000 to 448,000. But the number of people who moved into Boston during that decade was nearly ten times higher. More than 800,000 people passed through Boston during the decade between 1880 and 1890. Most stayed for a while and then moved on. The rapid turnover of Boston’s residents was only noticed when historians studied the city directories published annually. The researchers discovered that City Directory canvassers found only about half the homes they visited had the same residents, from one year to the next.

Digging into these directories, population historians discovered that the most mobile city-dwellers were often wage-workers and the poor. People who owned businesses and valuable real estate were much more “persistent,” in demographic terms, because they were in a sense anchored by their possessions. Over time, though, the greater persistence of more prosperous residents often allowed them to gain greater political power than poorer people who in many cases did not stick around long enough to organize; or often even to vote. Many poor and working-class city-dwellers were also recent immigrants, who needed time to learn the language and customs of their new homes. By 1900, inland cities such as Buffalo, Detroit, Milwaukee, Chicago, and Minneapolis were all the centers of regions where more than 75 percent of people lived in an urban setting. And after a half-century of immigration from Europe, more than three quarters of the residents of these cities were also classified as “Whites of Foreign Parentage,” according to Census language. That meant they were immigrants or the children of immigrants, overwhelmingly from either Irish or German-speaking families. Descendants of German immigrants, who arrived in great numbers just as the Midwest was opening for settlement in the mid-nineteenth century, still make up the majority ethnicity of a wide swath of middle America.

Questions for Discussion

- How does the decennial census misrepresent the actual impact of immigration in American cities?

- Why was “persistence” of residence so important for achieving political influence?

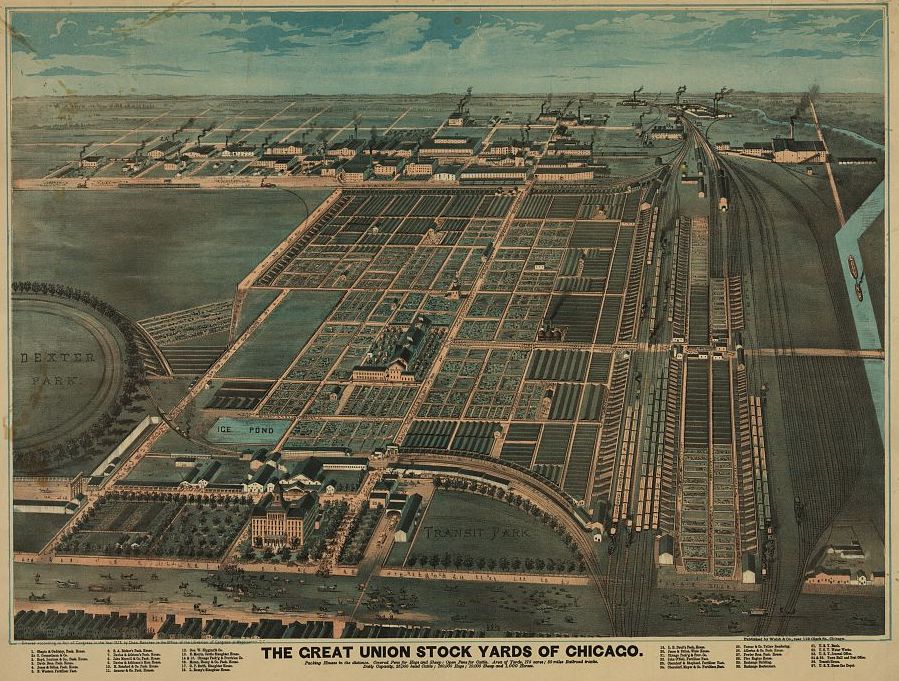

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Chicago became a symbol of the triumph of American industrialization. Its meatpacking industry represented many of the troubling changes occurring in American life. In the last decades of the century Chicago became America’s butcher. The city’s famous Union Stock Yards opened in 1864 on 320 acres of swampy land southwest of the city. Animal pens were connected to the railroads with fifteen miles of track. The Yards were already processing two million animals annually in 1870, and by 1890 they processed 9 million animals a year. By 1900, after an expansion, the 475-acre Yards employed 25,000 people and produced over 80 percent of the meat sold in America. The complex contained 2,500 livestock pens that could house 75,000 hogs, 21,000 cattle, and 22,000 sheep at the same time. The Chicago meat processing industry, a cartel of five firms led by Cudahy, Swift, and Armour, produced four fifths of the meat bought by American consumers. British author Rudyard Kipling visited the Stock Yards while living in America. “Once having seen them,” he reported, “you will never forget the sight.”

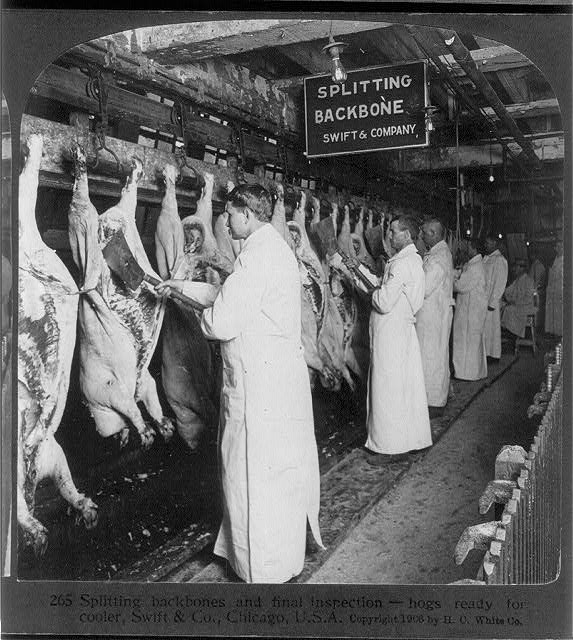

Chicago’s explosive growth reflected national trends. In 1870, only a quarter of the U.S. population had lived in towns or cities with populations greater than 2,500 and the largest occupational group was farmer. By 1920, a majority of Americans lived in towns and cities. Chicago’s newcomers had at first come mostly from Germany, Great Britain, and Scandinavia, but by 1890, Poles, Italians, Czechs, Hungarians, Lithuanians, and others from southern and eastern Europe made up a majority of new immigrants. In 1900, nearly 80 percent of Chicago’s population was either foreign-born or the children of foreign-born immigrants. In 1906, American novelist Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, a dramatic account of the experiences of a Lithuanian immigrant family living in Chicago and working in the Stock Yards. Although Sinclair had intended the novel to reveal the brutal exploitation of labor in the Yards and the meatpacking industry, to build support for the socialist movement, its major impact was to expose the dangerously unsanitary nature of industrialized food production.

The growing invisibility of livestock production, slaughterhouses, and industrial food production for urban consumers had enabled unsanitary and unsafe conditions. Unlike previous generations who had lived close to the land and agriculture, urban working people didn’t understand where their food came from. On April Fool’s Day in 1878, the New York Daily Graphic published a fictitious interview with the celebrated inventor Thomas A. Edison. The article described a fictional “biggest invention of the age”, a new Edison machine that could create forty different kinds of food and drink out of only air, water, and dirt. “Meat will no longer be killed and vegetables no longer grown, except by savages,” Edison promised in the fictional account. The miraculous new machine would end “famine and pauperism.” And all for just $5 or $6 per machine! The story was a joke, of course, but Thomas Edison nevertheless received inquiries from readers wondering when the new food machine would be ready for the market and where they could get one. Americans had apparently witnessed so many startling technological advances that would have seemed far-fetched mere years earlier, that the Edison food machine seemed plausible to some readers. While the newspaper story of the “meat machine” was a joke, Chicago’s food manufacturing business was the real thing. American consumers no longer had to grow their own crops or raise their own livestock, as their ancestors had done in the past. The new food industry was the miraculous machine, although Sinclair described it in The Jungle in less optimistic terms. “The slaughtering machine ran on,” he wrote, “like some horrible crime committed in a dungeon, all unseen and unheeded, buried out of sight and of memory.” Ironically, Sinclair’s description of the dangerously unsanitary and inhumane practices of the stockyards and packing plants was even more upsetting to American readers than his exposé of the working conditions faced by poor immigrants. Popular outrage over The Jungle led to the passage of the Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. Sinclair reportedly remarked, “I aimed at America’s heart, and by accident hit it in the stomach.”

Questions for Discussion

- Why did author Upton Sinclair say, “I aimed for the public’s heart, and by accident hit it in the stomach”?

- How did the increasing invisibility of industrial food production affect American culture?

- Has our current food industry corrected or continued the practices of the Chicago Stock Yards?

Urban Reformers

Coastal cities had often contended with challenging environments, especially when they began to grow. Boston was originally built on a peninsula surrounded by ocean and salt marshes, anchored to the mainland by a very narrow connection at the city’s southern tip. New York City occupied originally the southern tip of Manhattan Island, but the city’s rapid growth quickly exhausted the island’s shallow, easily-contaminated wells. Yellow fever and cholera epidemics in the early 1830s convinced New Yorkers they needed a new water source, and between 1837 and 1842, the city built an aqueduct and a reservoir to carry and store water from the Croton River forty-one miles away. The gravity-fed aqueduct supplied a Receiving Reservoir located at what is now the Turtle Pond in Central Park, and a Distributing Reservoir on Fifth Avenue between 40th and 42nd Streets. With granite walls 50 feet high and 25 feet thick, the Distributing Reservoir looked like a fortress guarding its 20 million gallons of fresh water. The wide promenade at the top of the reservoir’s walls became a popular destination for Sunday-morning socializing. The Croton Distributing Reservoir was used until the 1890s, when it was torn down and replaced by the Main Branch of the New York Public Library and Bryant Park.

By 1844, more than 6,000 homes of upper-class New Yorkers had been connected to the public water distribution system and public bathing facilities had been constructed for the poor. Providing public water added to New York’s challenges, though. Initially, most of the water closets in affluent houses were connected only to cesspools and pits that had originally been built for solid waste from privies. The small cesspools were almost immediately flooded by the volumes of water and waste flushed into them. Responding to the complaints of its most affluent residents, the city allowed connections to its storm sewers. But the conduits designed to carry excess rainwater were too narrow and the underground pipes’ bends and sharp corners clogged easily. New York’s storm sewer system was quickly overwhelmed.

Before indoor plumbing became universal, waste disposal had been much more visible and personal. When the Croton Reservoir began delivering abundant running water to lower Manhattan in the late 1840s, New York City already housed half a million people. Although getting the water into the city was considered a public service, landlords were not required to use the system. The overall population density of Manhattan was measured at over 41,000 people per square mile in 1880, but in the city’s poorer, more crowded areas, well over 150,000 people were crowded onto each square mile of land. Tenements had been built on single-family lots only 25 feet wide by 100 feet deep, sometimes housing twenty families on a lot that had been designed for one. Although water and sewage were available on many of the main streets, builders were not required to connect tenements to them. Often, to save money, landlords installed a single standpipe to provide running water and built privies in the small backyards. After 1900, revised building codes required new construction to include running water and bathroom facilities in each apartment. It was a long time, however, before all the old tenements were abandoned and torn down.

The adoption of indoor plumbing made human waste disposal a municipal service rather than the responsibility of the people producing the waste. Toilets broke an age-old ecological cycle that had returned nutrients back to the soils that had produced them. This created a soil nutrient problem on farms and a waste disposal problem in cities. What had been a circular resource flow from farm to table and back to farm became a one-way trip. Crops drained farm soils of fertility only to be shipped to cities for consumption and converted into waste that was flushed away. Out of sight, out of mind.

In addition to engineers and city planners addressing growing cities’ needs for drinking water and sanitation, idealistic nineteenth-century reformers began working to improving social conditions in American cities. Some reformers called attention to the social problems caused by the cultural dislocations of immigration, economic inequality, and the rapid growth of America’s cities. Others experimented with solutions. This spirit of reform became a key element of the early-twentieth century Progressive movement in politics and culture that tried to correct some of the social inequities of the Gilded Age.

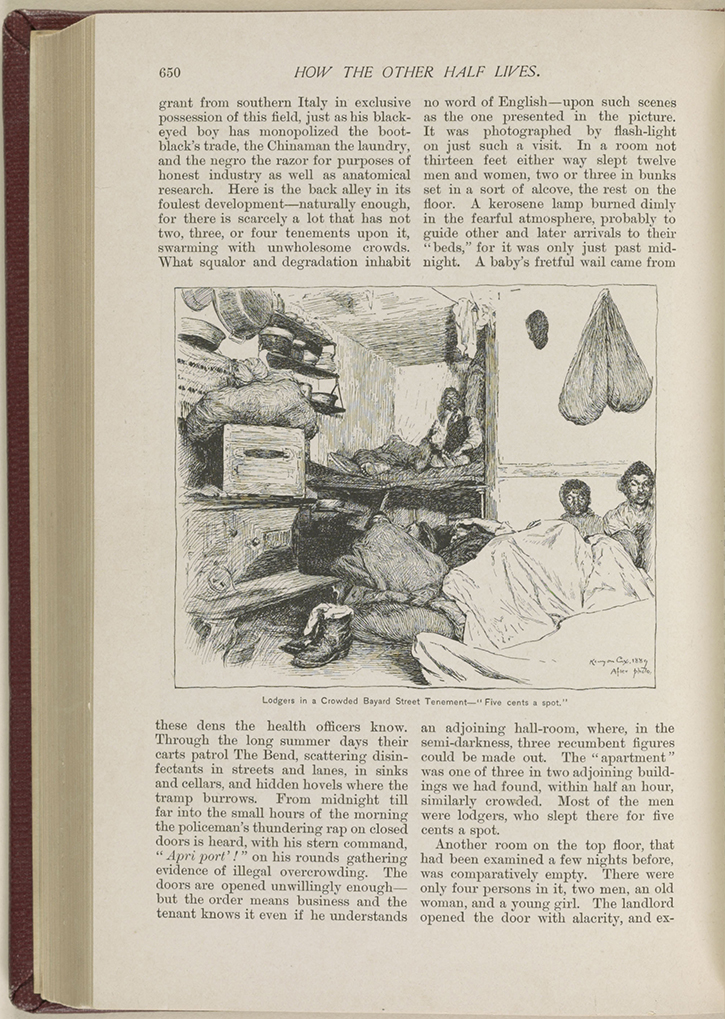

An early critic of urban inequality was Jacob Riis, a native of Denmark who became one of New York’s most prominent journalists. Riis had been born in 1849 into a family of fifteen children and had emigrated to New York at the age of 21. Originally trained as a carpenter, Riis became a newspaper reporter specializing in melodramatic accounts of the poverty and misery he found in neighborhoods like New York’s infamous Five Points. When words failed to convey the jarring disparity he witnessed between the glittering world of New York high society and the hopeless world of the poor, Riis turned to photography. In 1889, Riis’s eighteen-page article “How the Other Half Lives” was included in the widely-circulated Christmas issue of Scribner’s Magazine, with nineteen line drawings rendered from his photographs. Riis expanded the material into a 303-page book, which he followed two years later with a sequel called The Children of the Poor. Jacob Riis wrote a dozen more books over the next ten years and lectured regularly on social conditions in New York City. His efforts to call attention to the inequities of city life brought Riis to the attention of New York Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who later called Riis “the most useful citizen of New York.” Although the narratives in Riis’s books echoed many of the stereotypes of his time, his photographs were revolutionary. Middle- and upper-class Americans discovered there was an “Other Half” living in Gilded-Age America, and some began to devote themselves to reducing the inequality of their time.

One of the most effective social reformers who put her ideals into action providing direct services to poor city people was Jane Addams. Addams had been born into a prosperous Chicago family, the youngest daughter of a prominent Illinois politician. Born in 1860, Addams lost her mother and several siblings at a very young age, then grew up reading depictions of poor Londoners in novels by Charles Dickens and revolutionary tracts like the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini’s book, Duties of Man. After four years at Rockford Female Seminary, Addams embarked on a multiyear “grand tour” of Europe. Unlike other society ladies seeing the sights and visiting museums and concert venues, she found herself drawn to English settlement houses where philanthropists embedded themselves in poor communities and offered services to disadvantaged populations. Impressed by an 1887 visit to London’s famous settlement house, Toynbee Hall, Addams decided to start her own in Chicago. She returned home and opened Hull House in 1889. Begun in an old mansion that Addams purchased, moved into, and renovated with her own funds, Hull House grew into a thirteen-building complex that housed twenty-five women volunteers and served over 2,000 people per week.

Hull House settlement workers provided for their neighbors by running a nursery and a kindergarten, classes for parents and clubs for children, and by organizing social, recreational, and cultural events for the community. Services included public baths, boys’ and girls’ clubs, and a summer camp. In addition to their service work, Addams’ volunteer staff kept meticulous records and produced detailed studies of poverty, disease, and living conditions in the Chicago neighborhoods Hull House served. Social reformer Florence Kelley, who stayed at Hull House from 1891 to 1899, convinced Addams to begin exposing conditions in local sweatshops and advocating for the organization of workers into unions. Calling the conditions caused by urban poverty and industrialization a “social crime”, Addams began pressuring politicians. Together Kelley and Addams petitioned legislators to pass anti-sweatshop legislation that limited the workdays for women and children to eight hours. While Jane Addams called labor organizing a “social obligation,” she also warned the labor movement against the “constant temptation towards class warfare.” Addams, like many reformers, favored cooperation between rich and poor and bosses and workers.

Jane Addams and her organization began to influence public opinion and political debate on issues such as education reform, immigrants’ rights, occupational health and safety, child labor, and pension laws. Addams’ approach to solving problems of urban poverty included equal parts of direct aid to poor city people, scientific study into the roots of poverty and dependency, and political activism to bring this information to the public and government officials and to advocate change. Jane Addams became an international celebrity. In 1912, she became the first woman to give a nominating speech at a major party convention when she supported the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt as the Progressive Party’s candidate for president. Her campaigns for social reform and women’s rights won headlines and Addams’ advocacy grew beyond domestic concerns. Beginning with her work in the Anti-Imperialist League during the Spanish-American War, Addams increasingly began to see militarism as a drain on resources that might be better spent on social reform. In 1907 she wrote Newer Ideals of Peace, a book that became for many a philosophical foundation of pacifism. Addams emerged as a prominent opponent of America’s entry into World War I. She was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 for her work at Hull House, her advocacy work, and her anti-war activism.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did Theodore Roosevelt think Jacob Riis was the “most useful citizen” of New York?

- How did Jane Addams gain influence in public discussions about poor relief and social programs?

Gender, Religion, Culture

As we have seen, urbanization and immigration fueled anxieties that American culture was being subverted and that old forms of social and moral policing were increasingly inadequate. The anonymity of urban spaces presented an opportunity for female sexuality and for male and female sexual experimentation along a spectrum of orientations and identities. Anxiety over sex reflected generational differences as well as racial and class tensions. As young women pushed back against traditional expectations about premarital sexual expression, some social welfare experts and moral reformers labeled them feeble-minded, preferring to believe that such unfeminine behavior must be a symptom of clinical insanity rather than free-willed expression. Young people challenged the norms of their parents’ generations by wearing new fashions and enjoying the attractions of the city. Women’s clothing loosened their physical constraints: corsets relaxed and hemlines rose.

While many women worked to liberate themselves socially and sexually, many, sometimes simultaneously, worked to uplift others. Reform opened new possibilities for women’s activism in American public life and gave new energy to the long campaign for women’s suffrage. Support for women’s work came from female “clubs,” some focused on intellectual development; others emphasizing philanthropic activities. Unfortunately, few of these organizations were biracial, a legacy of the uneasy mid-nineteenth-century relationship between socially active African Americans and white women. Rising American prejudice led many white female activists to ban inclusion of their African American sisters. The General Federation of Women’s Clubs (formed in New York City in 1890) and the National Association of Colored Women (organized in Washington, D.C., in 1896), were both dominated by upper-middle-class, educated, northern women. But despite their similarities they remained divided by race.

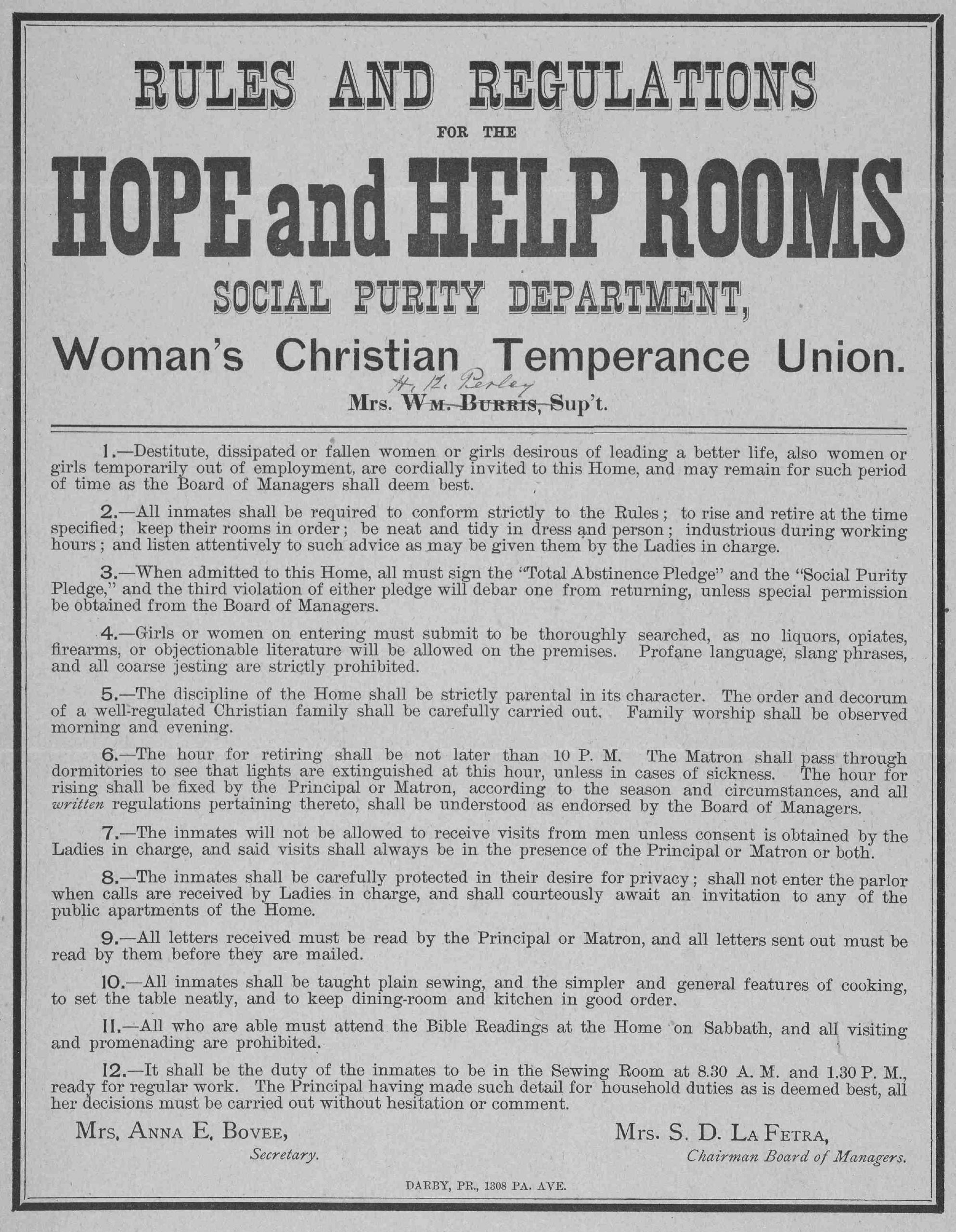

Women’s work against alcohol propelled temperance into one of the foremost moral reforms of the period. Middle-class women based their criticism of alcohol on Christian sentiment and their protective role in the family and home. Other women worked through churches and moral reform organizations to clean up American life. Some became moral vigilantes. Carrie A. Nation, an imposing woman who believed she was doing God’s will, won headlines for destroying saloons. In Wichita Kansas, in December 1900, Nation took a hatchet to the bar at the luxurious Carey Hotel. Arrested and charged with causing $3,000 in damages, Nation spent a month in jail before the county dismissed the charges on the basis of “delusion”. But Nation’s “hatchetation” drew national attention. Describing herself as “a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what He doesn’t like,” Nation continued her assaults and days later she smashed two more Wichita bars.

Most women, however, worked within more reputable organizations. Nation had founded a chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), but the organization’s leaders decided she was too “unwomanly and unchristian.” The WCTU had been established in 1874 as a modest temperance organization devoted to combating the evils of drunkenness. But in the last decade of the nineteenth century it transformed into a national political force, embracing a “do everything” policy that adopted any reforms that would improve social welfare and advance women’s rights. Temperance and then the full prohibition of alcohol became their goal.

Many American reformers associated alcohol with nearly every social problem. Drunkenness was blamed for domestic abuse, poverty, crime, and disease. The 1912 Anti-Saloon League Yearbook presented charts connecting increases in alcohol consumption with rising divorce rates. The WCTU called alcohol a “home wrecker.” Reformers also associated alcohol with cities and immigrants, maligning America’s recent arrivals, Catholics, and working classes in their crusade against liquor. Reformers believed that abolishing “strong drink” would bring social progress, reduce the need for prisons and insane asylums, save women and children from domestic abuse, and create a more just, progressive society.

Other American women expressed new discontents through literature. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s famous short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” attacked the expectation of feminine domesticity and ridiculed Victorian psychological remedies forced on women, such as the “rest cure.” Kate Chopin’s The Awakening criticized the domestic and familial roles available to women in American society and called attention to women’s feelings of malaise, desperation, and desire. Literature by and for women challenged the Victorian era’s understanding of femininity and feminine virtue, as well as established feminine roles.

It would be suffrage, ultimately, that would mark the full emergence of women in American public life. Generations of women had pushed for the right to vote. Notable victories were won in the West, where suffragists mobilized large numbers of women and male politicians embraced new forms of governance. Wyoming was the first state where women could vote beside men, beginning in 1869 with its acceptance as a U.S. territory and continuing with the writing of its state constitution in 1890. By 1911, six western states had passed suffrage amendments to their constitutions. Women’s suffrage was typically part of a package of reform efforts. Many suffragists argued that women’s votes were necessary to clean up politics and combat social evils. In the 1890s, the WCTU, then the largest women’s organization in America, endorsed suffrage. An alliance of working-class and middle- and upper-class women organized the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) in 1903 and campaigned for the vote alongside the National American American Suffrage Association. WTUL members viewed the vote as a way to further their economic interests and to foster a new sense of respect for working-class women.

The need to protect working-class women was starkly illustrated in 1911 when the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in Manhattan caught fire. The doors of the factory had been chained shut to prevent women employees from taking unauthorized breaks. The managers who held the keys had saved themselves when the fire broke out, but they left over two hundred women locked in the factory. A rickety fire escape ladder on the side of the building collapsed immediately. Women lined the rooftop and crowded the windows of the ten-story building to avoid the flames and smoke. Many jumped, landing in what newspaper reports described as a “mangled, bloody pulp”. Life nets held by firemen tore at the impact of the falling bodies. Among the onlookers, “women were hysterical, scores fainted; men wept [and] hurled themselves against the police lines.” By the time the fire burned itself out, 71 workers were injured and 146 had died.

A year earlier, the Triangle women had gone on strike demanding union recognition, higher wages, and better safety conditions. The owners of the factory had decided that the workers’ demands were too expensive and had called the police to break up the strike. After the 1911 fire, reporter Bill Shepherd reflected, “I looked upon the heap of dead bodies and I remembered these girls [and] their great strike last year in which the same girls had demanded more sanitary conditions and more safety precautions in the shops. These dead bodies were the answer.” After the fire, Triangle owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris were brought up on manslaughter charges. A jury acquitted them after less than two hours of deliberation.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did many activist women focus so much of their attention on banning alcohol? What were the advantages and disadvantages of this focus?

- Why was Wyoming one of the first places women were allowed to vote in the U.S.?

- How did the Triangle Fire focus national attention on women’s labor concerns?

While many men were challenged by the social changes women demanded, many also worried about their own masculinity. It seemed to many observers that industrial capitalism was withering American manhood. Rather than working on farms and in factories, where young men formed physical muscle and spiritual grit, workers sat behind desks, wore white collars, and pushed paper. A generation of young men were in danger of becoming what Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes described as “black-coated, stiff-jointed, soft-muscled, [and] paste-complexioned.” Neurologist George Beard even coined a medical term, neurasthenia, for a new condition marked by depression, indigestion, hypochondria, and extreme nervousness. The philosopher William James called it “Americanitis.” Academics increasingly warned that America had become a nation of emasculated men. Churches too worried about feminization. Women had always made up a majority of church memberships in the United States, but ministers believed they were gaining too much influence. The theologian Washington Gladden said, “A preponderance of female influence in the Church or anywhere else in society is unnatural and injurious.” Many feared that the feminized church had emasculated Christ himself. Rather than a rough-hewn carpenter, Jesus had been made “mushy” and “sweetly effeminate,” in the words of Baptist pastor Walter Rauschenbusch.

Advocates of a more masculine, muscular Christianity tried to stiffen young men’s backbones by putting them in touch with their primal manliness. They believed that young men ought to evolve as they imagined civilization evolved, advancing from primitive nature-dwelling to modern industrial enlightenment. But modern men had missed the earlier stage of development that should have toughened them up. To facilitate “primitive” encounters with nature for their members, these muscular Christians founded summer camps and outdoor boys’ clubs like the Woodcraft Indians, the Sons of Daniel Boone, and the Boy Brigades. Other champions of muscular Christianity, such as the Young Men’s Christian Association, built gymnasiums, often attached to churches, where young men could strengthen their bodies as well as their spirits. It was YMCA leader who coined the term bodybuilding; others invented the sports of basketball and volleyball.

Muscular Christianity, though, was about more than building strong bodies and minds. Many advocates also romanticized the “Wild West” myth and championed imperialism, cheering on attempts to “civilize” non-Western peoples. Gilded Age men were encouraged to embrace a particular vision of masculinity connected with the rising tides of nationalism, militarism, and imperialism. During the Spanish-American War in 1898, Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders had embodied the ideal of the tall, strong, virile, and fit American man that epitomized the United States’ imperial agenda. Roosevelt and others like him believed a reinvigorated masculinity would preserve the American race’s superiority against foreign foes and the feminizing effects of over-civilization. The centrality of manhood as an imperial ideal may well have set back women’s efforts to gain a voice and a vote in American society.

Questions for Discussion

- Was concern over “neurasthenia” or “Americanitis” legitimate, in your opinion?

- How did the new focus on fitness relate to America’s idea of itself in world affairs?

Targeting Trusts

In one of the most popular books of the Progressive Era, The Promise of American Life, Herbert Croly argued in 1909 that because “the corrupt politician has usurped too much of the power which should be exercised by the people,” the “millionaire and the trust have appropriated too many of the economic opportunities formerly enjoyed by the people.” The people had failed to hold their politicians accountable, which had allowed corporations and their owners to dominate American economic life and grab more than their fair share. Croly and other reformers believed that wealth inequality eroded democracy and the people had to win back the power taken by the moneyed trusts. These “trusts” were monopolies or cartels that made agreements or consolidated (often illegally) to control a specific product or industry.

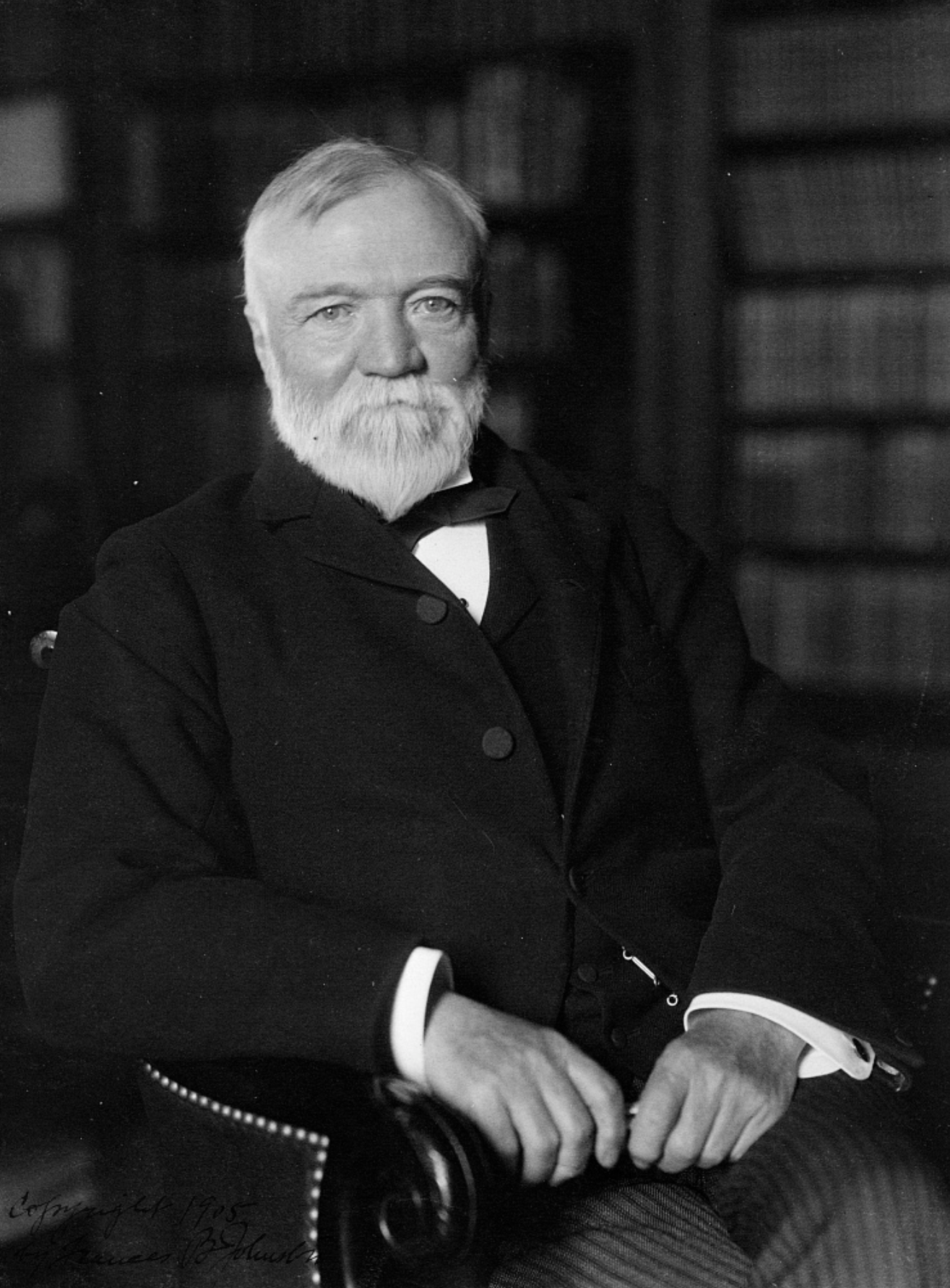

The rapid industrialization, technological advancement, and urban growth of the 1870s and 1880s triggered major changes in the way businesses structured themselves. A Second Industrial Revolution was enabled by new technological inventions and by new national and global markets, and by the federal government’s laissez faire, or “hands off,” economic policy. An argument influenced by the ideas of Social Darwinism claimed that an unregulated business climate had allowed for the beneficial growth of trusts such as the consolidation of Carnegie Steel in 1901 along with 200 companies in 127 cities into U.S. Steel, and John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. These two corporate giants displayed the vertical and horizontal integration strategies common to the new trusts. Carnegie used vertical integration to control every phase of business from raw materials to transportation, manufacturing, and distribution. Rockefeller practiced horizontal integration by buying out competing refineries. Once they dominated a market, critics warned, the trusts would be free to inflate prices, bully rivals, and bribe politicians.

Between 1897 and 1904, over four thousand companies had been consolidated down into 257 giant corporations. The twentieth century became the age of monopoly and the aggressive businessmen known to their critics as robber barons. Their cutthroat stifling of economic competition, mistreatment of workers, and corruption of politics sparked an opposition that pushed for regulations to rein in the power of monopolies. Big business, whether in meatpacking, railroads, telegraph lines, oil, or steel, posed new problems for the American legal system. Before the Civil War, most businesses had operated in a single state. They might ship goods across state lines or to other countries, but they typically had offices and factories in just one state. However, once mass-producing corporations operated across the nation, questions arose about who had the authority to regulate such firms. During the 1870s, many states passed laws to check the growing power of corporations. In 1887, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act, establishing an Interstate Commerce Commission to prevent discriminatory and predatory pricing practices. The Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 aimed to limit the anticompetitive practices of cartels and monopolistic corporations. The Sherman Act declared that not all monopolies were illegal, only those that “unreasonably” stifled free trade. The courts seized on the law’s vague language, however, and the act was turned against itself to limit the growing power of labor unions. Only in 1914, with the Clayton Anti-Trust Act, did Congress attempt to close loopholes in previous legislation.

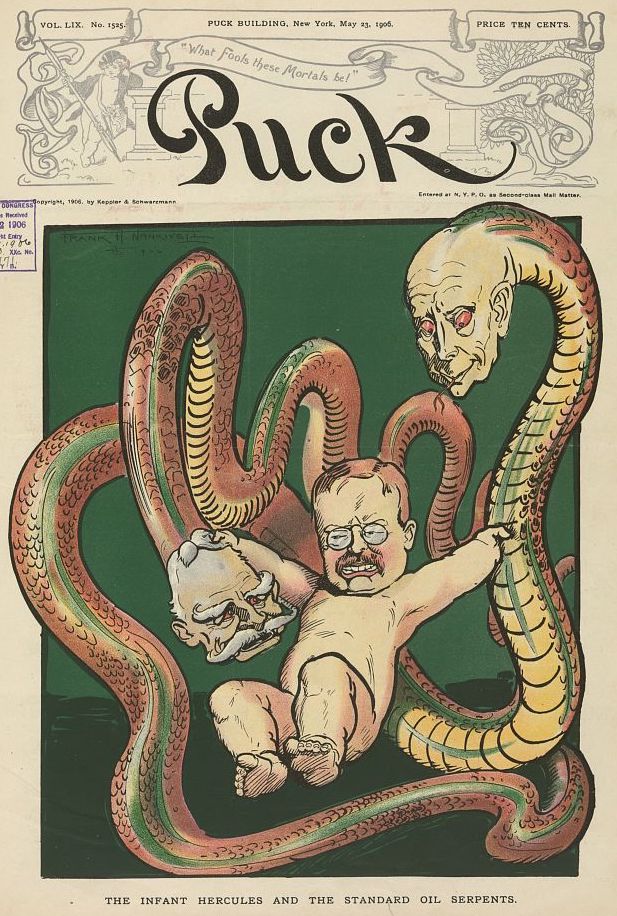

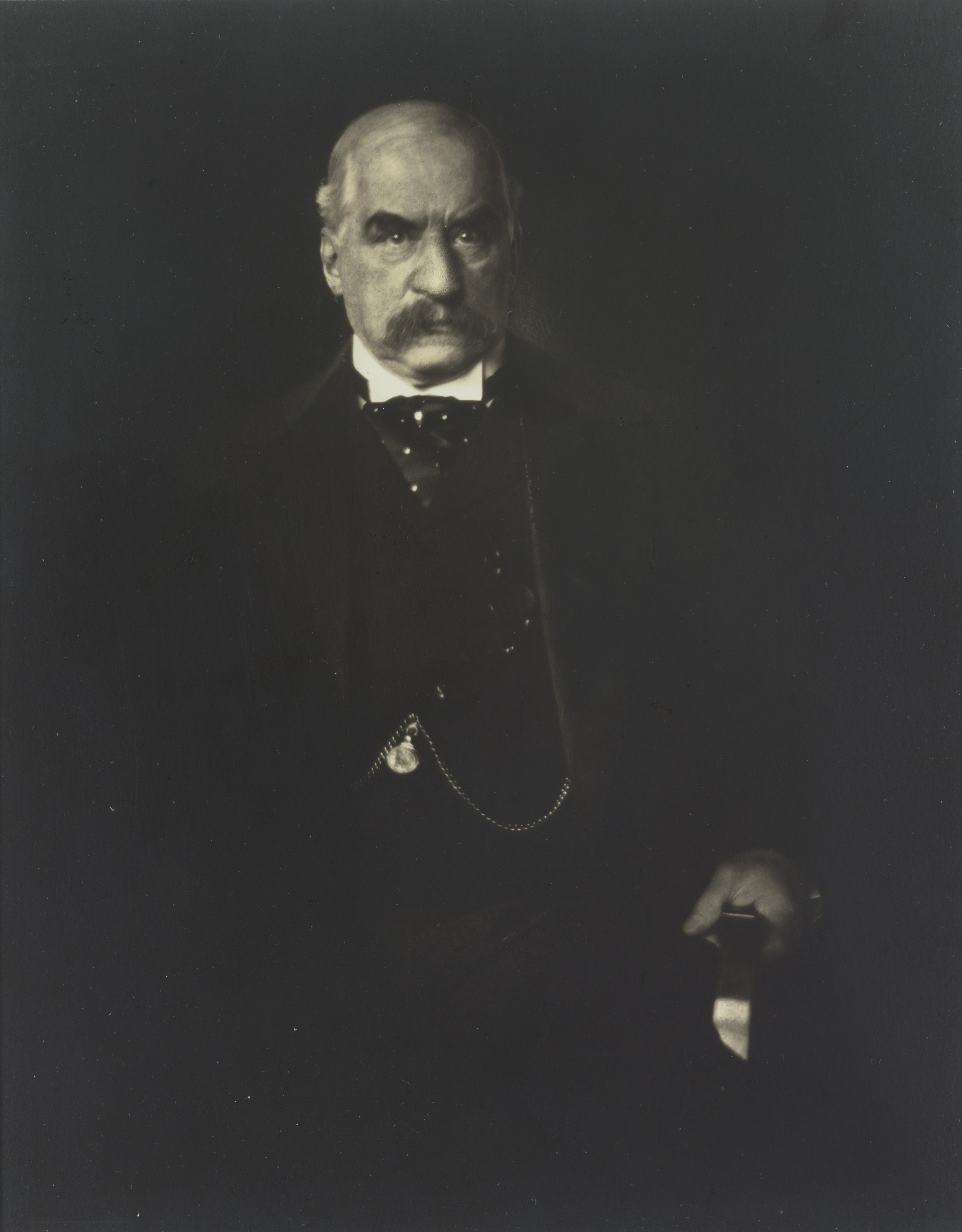

The progressive idea of “trust busting” gained popularity with the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, who imagined himself a mediator between opposing forces such as labor unions and corporate executives. Despite his own wealthy background, Roosevelt pushed for antitrust legislation and regulations, arguing that the courts could not be relied on to break up the trusts. Roosevelt relied on his own moral judgment to determine which monopolies he would pursue. Roosevelt believed there were good and bad trusts, necessary monopolies and corrupt ones. Although his reputation as a trust buster was wildly exaggerated, he was the first major national politician to at least speak against the trusts. “The great corporations which we have grown to speak of rather loosely as trusts,” he said, “are the creatures of the State, and the State not only has the right to control them, but it is in duty bound to control them wherever the need of such control is shown.” Roosevelt was widely believed to have come to a gentlemen’s agreement of some type with J. P. Morgan, and after a single conflict over Northern Securities, the trust-buster never again pursued banker who created the biggest trusts. But the president was also an expert at reading which way the political winds were blowing, and may have been responding to popular opinion in his choice of targets.

Roosevelt’s single Morgan-backed target was the Northern Securities Company, a trust used by wealthy bankers to hold controlling shares in all the major railroad companies in the American Northwest. By controlling the majority of shares rather than the principal, Morgan and his collaborators tried to claim that it was not a monopoly and circumvent the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. Roosevelt’s administration sued and in 1904 the Northern Securities Company disbanded into separate competitive companies. Two years later Roosevelt signed the Hepburn Act, allowing the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate best practices and set reasonable rates for the railroads. Roosevelt was more interested in regulating corporations than breaking them apart. However, his successor William Howard Taft firmly believed in court-led trust busting and during his four years in office more than doubled the number of monopoly breakups that had occurred during Roosevelt’s seven years in office. Taft notably went after U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar corporation that J.P. Morgan had formed by merging nearly every major American steel producer.

Trust busting and the proper handling of monopolies dominated the election of 1912. When the Republican Party re-nominated the incumbent Taft for a second term, Roosevelt left the party and formed the Progressive or “Bull Moose” Party. Although Roosevelt had hand-picked Taft as his successor, he may have felt the litigious president relied too much on the power of the courts (Taft would later sit on the Supreme Court) to attack bankers who had become Roosevelt’s allies. In the 1912 campaign, Roosevelt’s main financial support came from George Perkins, the Morgan partner who had put together the U.S Steel merger. Roosevelt’s “Bull-Moose Progressive” campaign was endorsed by many reformers such as Jane Addams, but it was a political disaster. Taft and Roosevelt split the Republican votes, allowing the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, to carry forty states with only about 42 percent of the popular vote. Wilson’s platform emphasized neither trust busting nor federal regulation but rather incentives he claimed would help small-businesses increase their competitive chances. Although like Bryan before him, Wilson claimed to support the ideas of the third party (he is still sometimes described by historians as a Progressive), once he won the election, Wilson edged nearer to Roosevelt’s position, signing the Clayton Anti-Trust Act of 1914. The Clayton Act substantially enhanced the earlier Sherman Act, specifically regulating mergers and price discrimination and protecting labor’s access to collective bargaining and related strategies of picketing, boycotting, and protesting. Congress created the Federal Trade Commission to enforce the Clayton Act, ensuring at least some measure of implementation. We will return for a closer look at Woodrow Wilson’s presidency in the next chapter.

Questions for Discussion

- Why were critics of big business concerned about the wave of mergers between the 1890s and the early 1900s?

- How did the growth of commerce from a local to a national scope change the way government related to businesses?

- Was President Roosevelt’s reputation as a “trust-buster” deserved?

Primary Sources

Andrew Carnegie on “The Triumph of America” (1885)

Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie celebrated and explored American economic progress in this 1885 article, later reprinted in his 1886 book, Triumphant Democracy.

Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams (1918)

Henry Adams, the great grandson of President John Adams, the grandson of President John Quincy Adams, the son of a major American diplomat, and an accomplished Harvard historian, writing in the third person, describes his experience at the Great Exposition in Paris in 1900 and writes of his encounter with “forces totally new.”

Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives (1890)

Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant, combined photography and journalism into a powerful indictment of poverty in America. His 1890, How the Other Half Lives shocked Americans with its raw depictions of urban slums. Here, he describes poverty in New York.

Rose Cohen on the World Beyond her Immigrant Neighborhood (ca.1897/1918)

Rose Cohen was born in Russia in 1880 as Rahel Golub. She immigrated to the United States in 1892 and lived in a Russian Jewish neighborhood in New York’s Lower East Side. Her, she writes about her encounter with the world outside of her ethnic neighborhood.

Jane Addams, “The Subjective Necessity for Social Settlements” (1892)

Hull House, Chicago’s famed “settlement house,” was designed to uplift urban populations. Here, Addams explains why she believes reformers must “add the social function to democracy.” As Addams explained, Hull House “was opened on the theory that the dependence of classes on each other is reciprocal.”

Eugene Debs, “How I Became a Socialist” (April, 1902)

A native of Terre Haute, Indiana, Eugene V. Debs began working as a locomotive fireman (tending the fires of a train’s steam engine) as a youth in the 1870s. His experience in the American labor movement later led him to socialism. In the early-twentieth century, as the Socialist Party of America’s candidate, he ran for the presidency five times and twice earned nearly one-million votes. He was America’s most prominent socialist. In 1902, a New York paper asked Debs how he became a socialist. This is his answer.

Woodrow Wilson on the “New Freedom,” 1912

Woodrow Wilson campaigned for the presidency in 1912 as a progressive democrat. Wilson argued that changing economic conditions demanded new and aggressive government policies–he called his political program “the New Freedom”– to preserve traditional American liberties.

Theodore Roosevelt on “The New Nationalism” (1910)

In 1910, a newly invigorated Theodore Roosevelt delivered his outline for a bold new progressive agenda, which he would advance in 1912 during a failed presidential run under the new Progressive, or “Bull Moose,” Party.

References:

This chapter was written by Dan Allosso, based on two chapters from The American Yawp. Those chapters were edited by David Hochfelder (Chapter 18), with content contributions by Jacob Betz, David Hochfelder, Gerard Koeppel, Scott Libson, Kyle Livie, Paul Matzko, Isabella Morales, Andrew Robichaud, Kate Sohasky, Joseph Super, Susan Thomas, Kaylynn Washnock, and Kevin Young; and Mary Anne Henderson (Chapter 20), with content contributions by Andrew C. Baker, Peter Catapano, Blaine Hamilton, Mary Anne Henderson, Amanda Hughett, Amy Kohout, Maria Montalvo, Brent Ruswick, Philip Luke Sinitiere, Nora Slonimsky, Whitney Stewart, and Brandy Thomas Wells.

Recommended Reading on City Life:

- Beckert, Sven. Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Blight, David. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Briggs, Laura. “The Race of Hysteria: ‘Overcivilization’ and the ‘Savage’ Woman in Late Nineteenth-Century Obstetrics and Gynecology.” American Quarterly 52 (June 2000). 246–273.

- Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

- Cole, Stephanie, and Natalie J. Ring, eds. The Folly of Jim Crow: Rethinking the Segregated South. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2012.

- Cott, Nancy. The Grounding of Modern Feminism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987.

- Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: Norton, 1991.

- Edwards, Rebecca. New Spirits: Americans in the Gilded Age, 1865–1905. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Gutman, Herbert. Work, Culture and Society in Industrializing America: Essays in American Working-Class and Social History. New York: Knopf, 1976.

- Hale, Grace Elizabeth. Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940. New York: Pantheon Books, 1998.

- Kasson, John F. Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century. New York: Hill and Wang, 1978.

- Leach, William. Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture. New York: Random House, 1993.

- Lears, T. J. Jackson. No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880–1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

- Odem, Mary. Delinquent Daughters: Protecting and Policing Adolescent Female Sexuality in the United States, 1885–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Peiss, Kathy. Cheap Amusements. Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986.

- Peiss, Kathy. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

- Putney, Clifford. Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Silber, Nina. The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865–1900. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Strouse, Jean. Alice James: A Biography. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1980.

- Trachtenberg, Alan. The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007.

Recommended Reading on the Progressive Era:

- Ayers, Edward. The Promise of the New South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Bay, Mia. To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells. New York: Hill and Wang, 2010.

- Cott, Nancy. The Grounding of Modern Feminism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987.

- Dawley, Alan. Struggles for Justice: Social Responsibility and the Liberal State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Dubois, Ellen Carol. Women’s Suffrage and Women’s Rights. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

- Filene, Peter. “An Obituary for ‘The Progressive Movement,’” American Quarterly 22 (Spring 1970): 20–34.

- Flanagan, Maureen. America Reformed: Progressives and Progressivisms, 1890s–1920s. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Foley, Neil. The White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Gilmore, Glenda E. Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Hale, Grace Elizabeth. Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Hicks, Cheryl. Talk with You Like a Woman: African American Women, Justice, and Reform in New York, 1890–1935. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Hofstadter, Richard. The Age of Reform: From Bryan to F.D.R. New York: Knopf, 1955.

- Johnson, Kimberley. Governing the American State: Congress and the New Federalism, 1877–1929. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Kessler-Harris, Alice. In Pursuit of Equity: Women, Men, and the Quest for Economic Citizenship in 20th-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Kloppenberg, James T. Uncertain Victory: Social Democracy and Progressivism in European and American Thought, 1870–1920. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Kolko, Gabriel. The Triumph of Conservatism. New York: Free Press, 1963.

- Kousser, J. Morgan. The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880–1910. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974.

- McGerr, Michael. A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870–1920. New York: Free Press, 2003.

- Molina, Natalia. Fit to Be Citizens?: Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879–1939. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

- Muncy, Robyn. Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890–1935. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Rodgers, Daniel T. Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Sanders, Elizabeth. The Roots of Reform: Farmers, Workers, and the American State, 1877–1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Stromquist, Shelton. Re-Inventing “The People”: The Progressive Movement, the Class Problem, and the Origins of Modern Liberalism. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

- White, Deborah. Too Heavy a Load: In Defense of Themselves. New York: Norton, 1999.

- Wiebe, Robert. The Search for Order, 1877–1920. New York: Hill and Wang, 1967.

- Woodward, C. Vann. Origins of the New South, 1877–1913. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1951.

Media Attributions

- 4a31829v © Detroit Publishing Co.

- Milwaukee © The Gugler Lithographic Co is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 02434v © Walsh & Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Chicago_meat_inspection_swift_co_1906 © H. C. White Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- jr0059_enlarge © Jacob Riis is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Jane_Addams © Cox Studio is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Hull_House © V.O. HAMMON PUBLISHING CO. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Jane_Addams_profile © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- TangoOfTo-Day

- Carrie_Nation is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 001dr © WCTU is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Charlotte_Perkins_Gilman_by_Frances_Benjamin_Johnston © Frances Benjamin Johnston is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Landscape © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- TriangleFire_25March1911_BodiesOnSidewalk © Brown Brothers is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Screen Shot 2020-01-26 at 8.50.58 PM © Boston Medical and Surgical Journal is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Kansas_U_team_1899 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3j00122v © Udo Keppler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Carnegie © Johnston, Frances Benjamin is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Senatorial_Round_House_by_Thomas_Nast_1886 © Thomas Nast is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 26061v © Puck Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- JP_Morgan © Edward Steichen