1 Capital and Labor

In this chapter we will focus on the changing American economy in the period between the end or Reconstruction in 1876 and the First World War, and how people responded to this challenge. We are paying particular attention to mostly urban issues of labor and corporate power, and as a result passing over some important issues of rural and Western America that we will return to in the next chapter. This means we will be covering the same decades from two slightly different angles in successive chapters. This is one way of approaching the topic, which is used in most textbooks. It’s not my favorite way, but I’m still working on a slightly different approach.

There will be questions along the way to verify you’re getting the main ideas and to suggest points you may want to consider for discussion and exams. A video of a lecture that covers this information is available at the end of the chapter, and there’s a podcast version of the content available here that you can to listen to while reading or use to review. You will need to highlight, annotate and comment using Hypothesis, but I want to make the content as accessible as possible to people with different learning styles.

Financial Instability

Although the Civil War was about slavery and not about states’ rights, as many revisionists have claimed, it is nonetheless true that the war and its aftermath catalyzed a widespread increase in federal power at the expense of state and local control. The Lincoln administration’s Pacific Railway Act created a new transcontinental rail industry. Its elimination of state banking in favor of a system of national banks consolidated credit in eastern financial centers, primarily in New York City. And government spending and tax policy during and after the war helped create new industries such as Standard Oil, which benefited from a prohibitive tax that made grain alcohol uncompetitive with kerosene as a fuel. Federal control and concentrated economic power seemed to promise a new era of rational economic management for the newly reunified, continental nation. But neither government nor big business were able to tame the boom-and-bust business cycles that continued to plague the American economy.

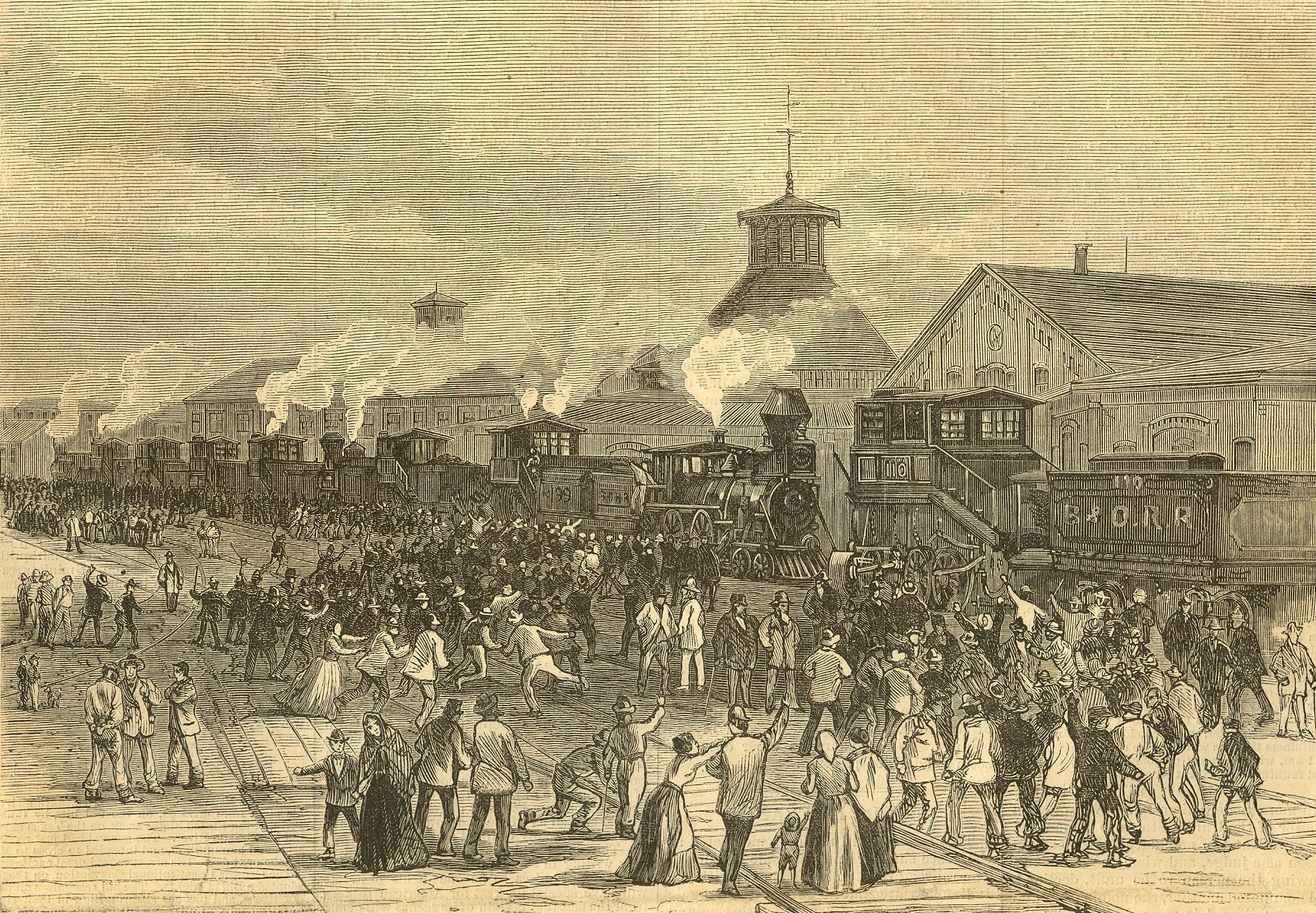

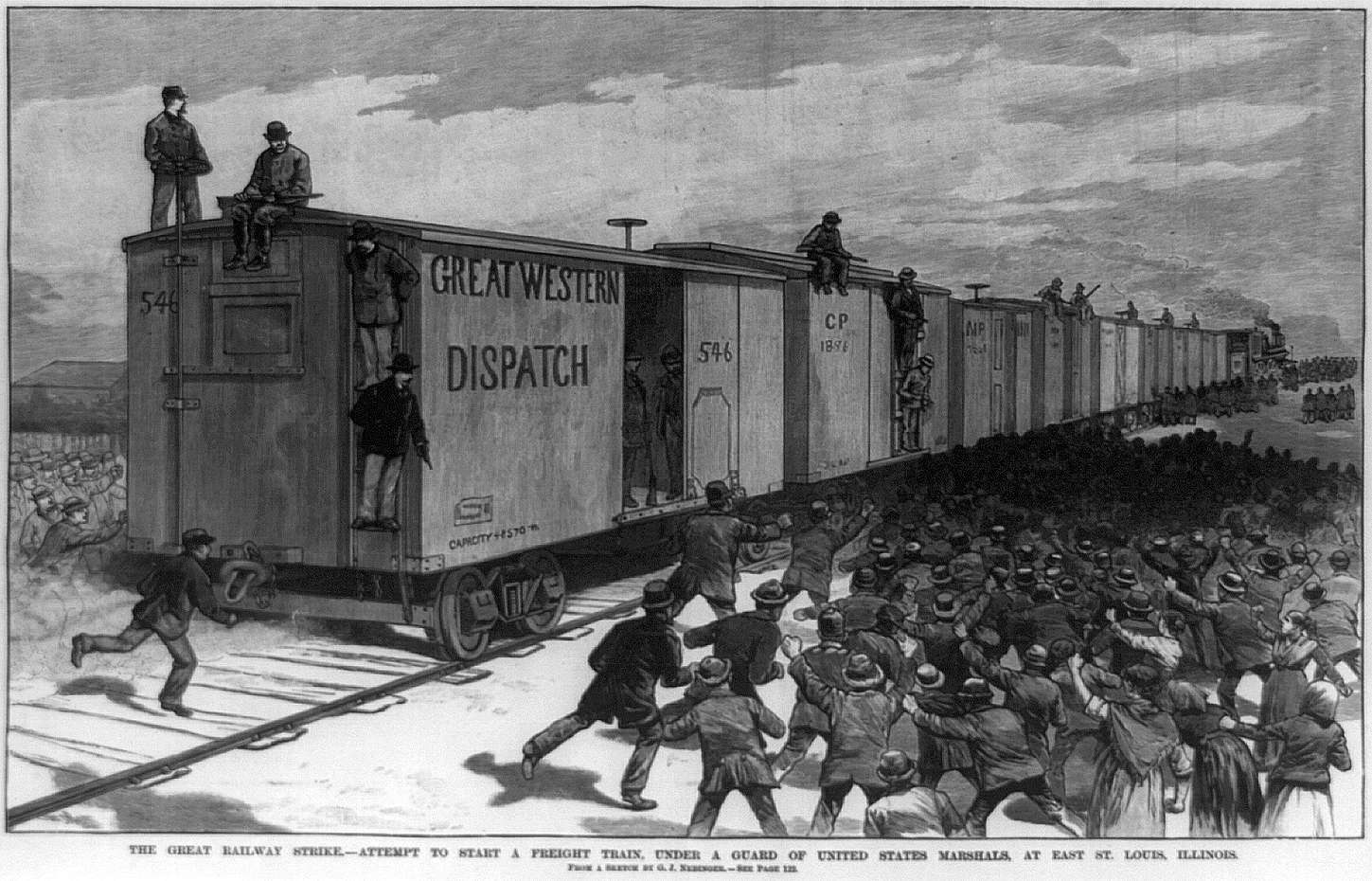

The speculative bubble created by railroad financing burst in the Panic of 1873, which began a period called the Long Depression that lasted until nearly the end of the century and was so bad that before the Great Depression of the 1930s the period was known simply as “The Depression”. The Panic began with the failure of the largest bank in America, owned by railroad speculator Jay Cooke. The United States government’s decision to stop coining silver dollars in 1873 and return to the gold standard in 1875 exacerbated the financial distress, and lower wages and deflation led to labor disputes like the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Rail lines slashed wages although, workers complained, they continued to reap enormous government subsidies and pay shareholders lucrative stock dividends. Workers struck from Baltimore to St. Louis, shutting down railroad traffic—the nation’s economic lifeblood—across the country.

Panicked business leaders and their political allies reacted quickly. When local police forces would not or could not suppress the strikes, governors called on state militias or even the US Army to break them and restore rail service. Many striking workers destroyed rail property rather than allow militias to reopen the rails. The protests approached a class war. The governor of Maryland deployed the state’s militia in Baltimore and the militia fired into a crowd of striking workers, killing eleven and wounding many more. Strikes convulsed towns and cities across Pennsylvania. The wealthy president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Thomas Andrew Scott, who had been Assistant Secretary of War for Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, is often named as one of the first Robber Barons of the Gilded Age. Scott suggested that if striking workers complained they were hungry, they should be given “a rifle diet for a few days and see how they like that kind of bread.”

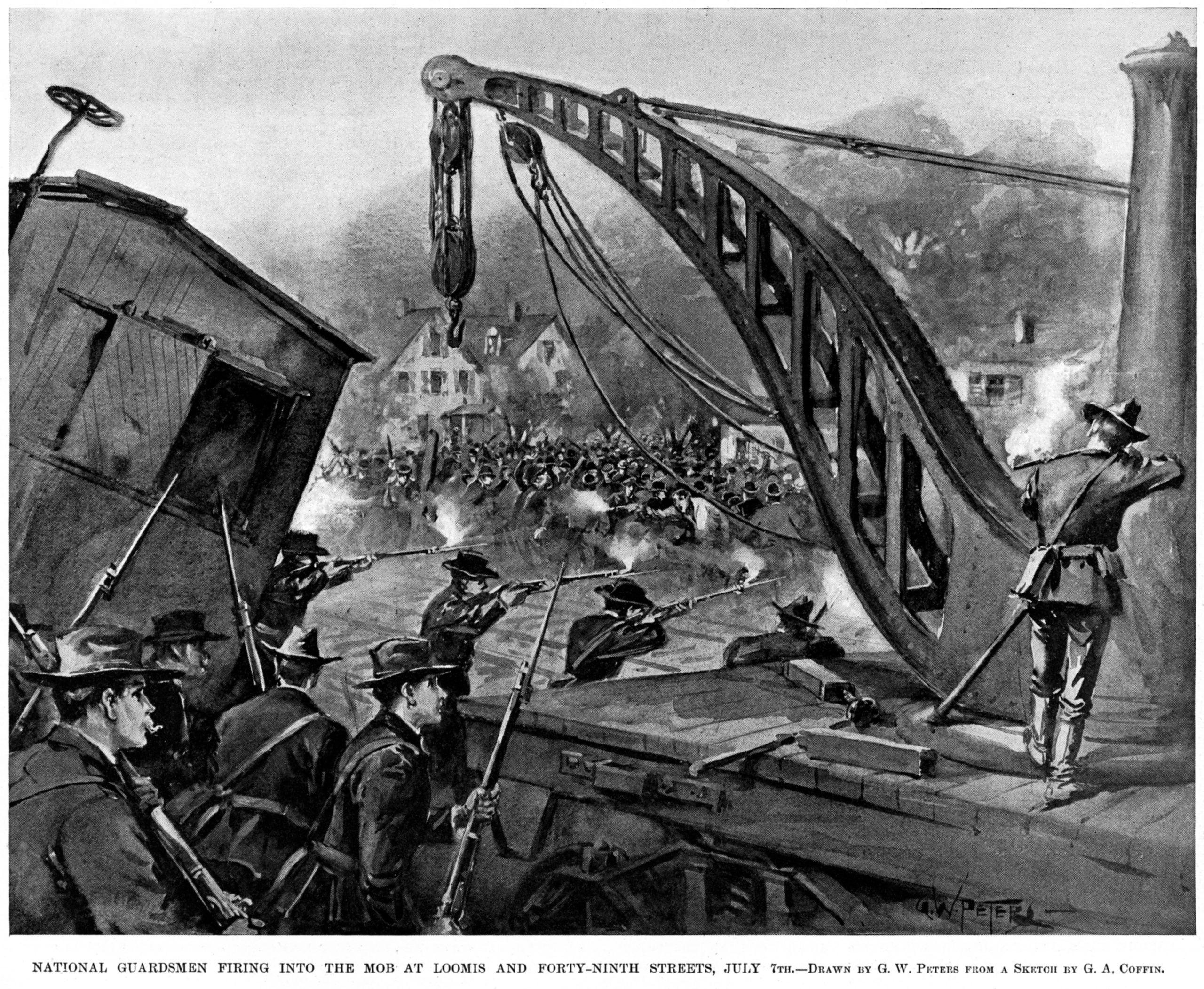

When police in Pittsburgh refused to put down the protests out of solidarity with the strikers, the governor called out the state militia who killed twenty strikers with bayonets and rifle fire. A month of chaos erupted. Strikers set fire to the Pittsburgh rail yards, destroying dozens of buildings, over a hundred locomotives, and over a thousand cars. In Reading Pennsylvania, strikers destroyed rail property and an angry crowd of sympathizers bombarded militiamen with rocks and bottles. The militia fired into the crowd, killing ten. A general strike erupted in St. Louis, one of the hubs connecting the eastern U.S. to the new transcontinental network. Strikers seized rail depots and declared their demands for the eight-hour day and the abolition of child labor. Federal troops and hired vigilantes fought their way into the main St. Louis depot, killing eighteen and breaking the strike. Rail lines were shut down all across neighboring Illinois, where coal miners struck in sympathy. The Workingmen’s Party, founded in 1876 by followers of Karl Marx, organized a protest in Chicago attended by tens of thousands. Twenty protesters were killed in Chicago by special police and militiamen.

The Workingmen’s Party reorganized in 1878 as the Socialist Labor Party, which still exists today. Courts, police, and state militias suppressed the strikes, but it was federal troops that finally defeated them. When Pennsylvania and West Virginia militiamen were unable to contain the strikes, federal troops stepped in. On the orders of President Hayes, American soldiers were deployed all across northern rail lines. Soldiers moved from town to town, suppressing protests and reopening rail lines. Six weeks after it had begun, the strike had been crushed. Nearly 100 Americans died in “The Great Upheaval.” Workers destroyed nearly $40 million worth of property. The strike galvanized the country. It convinced laborers of the need for institutionalized unions, persuaded businesses of the need for even greater political influence and government aid, and foretold a half century of labor conflict in the United States.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did the power of the federal government expand so much during the Lincoln administration?

- How did the consolidation of credit and financial markets aid the growth of big business?

- Why did corporate executives like Thomas Andrew Scott feel justified using deadly force against striking workers?

The Triumph of Capital

The great national strikes first hit the railroads only because no other industry had so effectively marshaled together capital, government support, and bureaucratic management. But labor unrest grew with the increasing success of industrial capitalism. Many workers perceived their new powerlessness in the coming industrial order. Skills mattered less and less in an industrialized, mass-producing economy, and their strength as individuals seemed ever smaller and less significant when companies grew in size and power and managers gained wealth and political influence. Long hours, dangerous working conditions, and the difficulty of supporting a family on meager and unpredictable wages compelled workers to organize armies of labor and battle against the power of capital.

The post–Civil War era saw revolutions in American industry. Technological innovations that had begun with the interchangeable parts introduced into gun manufacturing by Eli Whitney and national investments in infrastructure like railroads and telegraph slashed the costs of production and distribution. Inventions like sewing machines streamlined production and the Bell telephone and typewriters allowed more efficient communication, allowing new administrative frameworks to sustain the weight of vast, national corporations. National credit facilitated by the consolidation of banking in financial centers like New York eased uncertainties surrounding rapid movement of capital between investors, manufacturers, and retailers. Plummeting transportation and communication costs opened new national media, which manufacturers and their advertising agencies used to nationalize consumer products.

By the turn of the century, corporate leaders and wealthy industrialists had embraced new principles of scientific management called Taylorism after their noted proponent, Frederick Taylor. The precision of interchangeable steel parts, the harnessing of electricity after the victory of Nikola Tesla’s alternating current over Thomas Edison’s direct current, the innovations of machine tools, and the mass markets wrought by the railroads offered new avenues for efficiency. To match the demands of the machine age, Taylor said, firms needed a scientific organization of mass production. He urged all manufacturers to increase efficiency by subdividing tasks. Rather than having thirty mechanics individually making thirty machines, for instance, a manufacturer could assign thirty laborers to perform thirty distinct tasks. The workers would complete their individual tasks more quickly and with greater precision, since their attention would be focused. Such a shift would not only make workers as interchangeable as the parts they were using, it would also dramatically speed up the process of production. Taylorism increased the scale and scope of manufacturing and allowed for the flowering of mass production. Building on Whitney’s use of interchangeable parts in pre-Civil War weapons manufacturing, American firms advanced mass production techniques and technologies. Singer sewing machines, Chicago meat packers’ “disassembly” lines, McCormick grain reapers, and Duke cigarette rollers all achieved unprecedented levels of production that propelled their companies into the forefront of American business. Henry Ford, who consulted with Taylor, made the assembly line famous in 1913, allowing the production of automobiles to skyrocket as their cost plummeted; but American firms had been paving the way for decades.

Cyrus McCormick had been constructing mechanical reapers for harvesting wheat since the 1840s. He had relied on skilled blacksmiths, skilled machinists, and skilled woodworkers to handcraft horse-drawn machines. But production was slow and the machines were expensive. The reapers enabled massive efficiency gains in grain farming, but their high cost and slow production times put them out of reach of most American wheat farmers. Toward the end of his life in 1880, McCormick hired a production manager who had overseen the manufacturing of Colt firearms to transform his system. The McCormick plant introduced new jigs, steel gauges, and pattern machines that could make new, interchangeable parts. The Chicago factory had produced twenty-one thousand machines in 1880. In 1885 after McCormick’s death, with his son running the company, the factory produced twice as many. By 1889, less than a decade later, McCormick was producing over one hundred thousand a year in spite of labor disputes that exploded into the Haymarket Massacre of 1886.

New technologies like the McCormick reaper, the John Deere plow, and chemical fertilizers made America the world’s breadbasket by the 1870s. Industrialization and mass production pushed the United States into the forefront of world manufacturing. The American economy had lagged behind Britain, Germany, and France as recently as the 1860s, but by 1900 the United States had taken its place as the world’s leading manufacturing nation. Thirteen years later, by 1913, the United States produced one third of the world’s industrial output—more than Britain, France, and Germany combined.

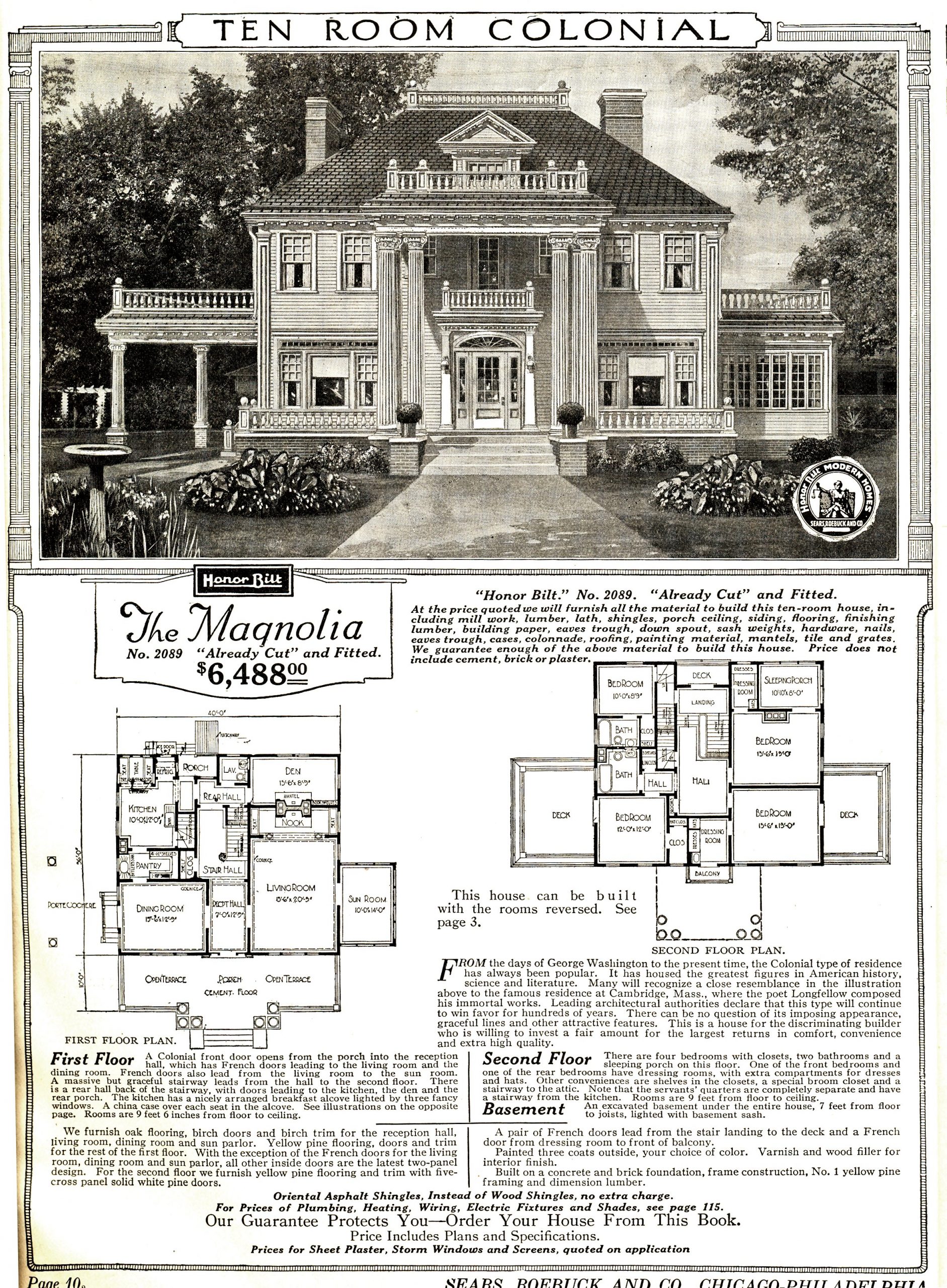

Firms such as McCormick’s took advantage of economies of scale: a reduced per-unit cost achieved by making great quantities of standardized products. After accounting for large “fixed cost” investments in machines and marketing, each additional unit of a product could be made for very low “variable” production cost. The bigger the production run, the bigger the profits. New industrial companies that could raise the capital to take advantage of scale economies hungered for markets to keep their high-volume production facilities operating. Retailers and advertisers helped create the massive markets needed for mass production, and corporate bureaucracies facilitated the management of giant new firms. A new class of professional managers operated between the worlds of workers and owners and ensured the efficient operation and administration of mass production and mass distribution. Retailers like Sears Roebuck, which launched its first mail-order catalog in 1888, helped create a mass consumer market. Chicago-based Sears took advantage of railroads to ship products as large as entire house-building kits to customers throughout America. Even more important to the growth and maintenance of these new companies, however, were the legal creations used to protect investors and sustain the power of massed capital.

The up-front costs of building factories for mass production and then marketing and distributing a product to a national or global market were prohibitive for all but the very wealthiest individuals. Even if the rich could afford to self-finance their industrial ventures, the risks and liabilities of big business were too great to bear individually. The corporate form was ages old, and joint stock corporations had been chartered by European monarchs in the early colonial period. But the privilege of incorporation had generally been reserved for public works projects or government-sponsored monopolies. Colleges, hospitals, and even bridges were built by chartered corporations because they provided a public benefit and because they were natural monopolies: there only needed to be one in any particular place. After the Civil War, however, new state incorporation laws passed during the early nineteenth century became a legal mechanism for nearly any enterprise wishing to marshal vast amounts of capital while limiting the liability of shareholders. Corporations could sell shares to investors with the guarantee that all they risked were the dollars they invested. Unlike the proprietors of private companies, corporate shareholders had limited liability. Taking advantage of the opportunity to wash their hands of legal and financial obligations while still retaining the right to profit massively, investors flooded corporations with the capital they needed to industrialize.

But a competitive marketplace threatened the profitability of these capital investments. Unless an industrial process was protected by a patent, the process and the product could be duplicated by competitors. The first US patent laws, passed in 1790 and 1793, granted fourteen years of protection to patent-holders, but after that period products and processes were open to copying. The efficiency gains and scale economies of mass production were could be undone by cutthroat competition. To keep out competitors, firms dropped their prices, which cut into profits. Companies rose and fell, and many investors suffered losses, as manufacturers struggled to maintain supremacy in their particular industries. Achieving economies of scale was dangerous: while additional production increased profits, the high fixed costs of building and operating expensive factories dictated that even modest losses from selling underpriced goods were preferable to not selling goods at all. Manufacturers sometimes remarked ironically, we lose a little on each sale, but make it up with volume. Although the battle to gain market share by cutting prices often benefitted consumers, corporate profits became unstable. American industry tried everything to avoid competition, creating informal pools and trusts, entering price-fixing agreements, and dividing markets. When blocked by antitrust laws and renegade price cutting, many companies merged into consolidated corporations or trusts. Rather than suffer from ruinous competition, firms combined and bypassed it altogether.

Between 1895 and 1904, and particularly in the four years between 1898 and 1902, a wave of mergers rocked the American economy. Competition was eliminated in what became known as “the great merger movement.” In nine years, four thousand companies—nearly 20 percent of the American economy—were folded into rival firms. In nearly every major industry, newly consolidated corporations utterly dominated their market. General Electric was created in 1892 when Wall Street financier J.P. Morgan merged Thomas Edison’s electric company with several others. DuPont, established as a gun-powder mill in 1802, began expanding in 1902 when control was shifted to a professional director. The corporation dominated its sector so completely that it was the target of an antitrust investigation in 1912. Forty-one separate consolidations each controlled over 70 percent of the market in their respective industries. In 1901, J. P. Morgan oversaw the formation of United States Steel, built from eight leading steel companies. Industrialization was built on steel, and one firm—the world’s first billion-dollar company—controlled the market. A year later Morgan merged the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company with four other farm equipment companies to form International Harvester. Monopoly had arrived.

Questions for Discussion

- How did technological improvements lead to “de-skilling” of many industrial jobs?

- Why was Taylorism so exciting to investors and managers?

- How did the corporate form and economies of scale transform business?

- Why might Americans in the early years of the twentieth century have been worried about mergers and corporate consolidation?

Wealth Inequality

Industrial capitalism produced the greatest advances in efficiency and productivity that the world had ever seen. Giant corporations marshaled capital on an unprecedented scale, produced affordable consumer products, and earned profits that created unheard-of fortunes. But mass production also created millions of low-paid, unskilled, unreliable jobs with long hours and dangerous working conditions. Industrial capitalism launched the United States into a Gilded Age of inequalities that challenged American ideals of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness available to all. The sudden appearance of the extreme wealth of industrial and financial leaders alongside the crippling squalor of the urban and rural poor shocked Americans. “This association of poverty with progress is the great enigma of our times,” economist Henry George wrote in his 1879 bestseller, Progress and Poverty.

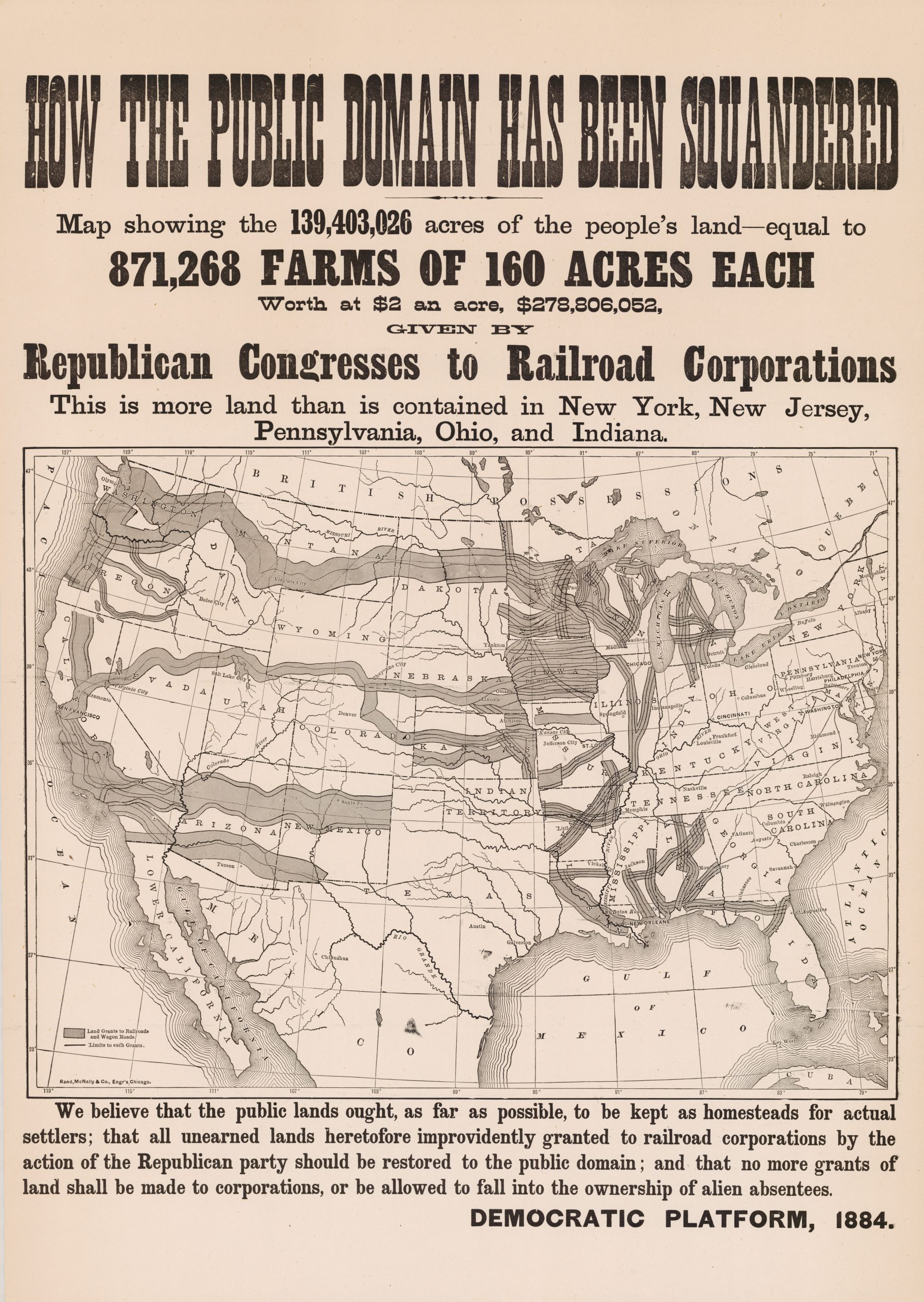

The great financial and industrial titans, called robber barons by their critics, included railroad investors such as Leland Stanford, Jay Gould, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, oilmen such as John D. and William Rockefeller, steel magnates such as Andrew Carnegie and Henry Frick, and bankers such as Jay Cooke and J. P. Morgan. These businessmen amassed fortunes that, adjusted for inflation, are still among the largest the nation has ever seen. And they congratulated themselves for their superior ability. Andrew Carnegie wrote an essay that became known as “The Gospel of Wealth” to justify his fortune. According to contemporary measurements, in 1890 the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans owned one fourth of the nation’s assets and the top 10 percent owned over 70 percent. As the Gilded Age progressed, the barons widened the head-starts they had often achieved only with government help. Railroad companies, for example, had been provided government-backed financing to build their transcontinental tracks and land grants totaling 175 million acres (an area about equal to the state of Texas). Bankers benefitted from national banking laws that consolidated finance in New York. The government and the railroads it financed were the steel industry’s biggest customers. Standard Oil employed predatory pricing, made secret deals with railroads on freight costs, and the government looked the other way while the Ohio company became a trust controlling over 90 percent of oil refining in America. By 1900, the richest 10 percent controlled perhaps 90 percent of the nation’s wealth.

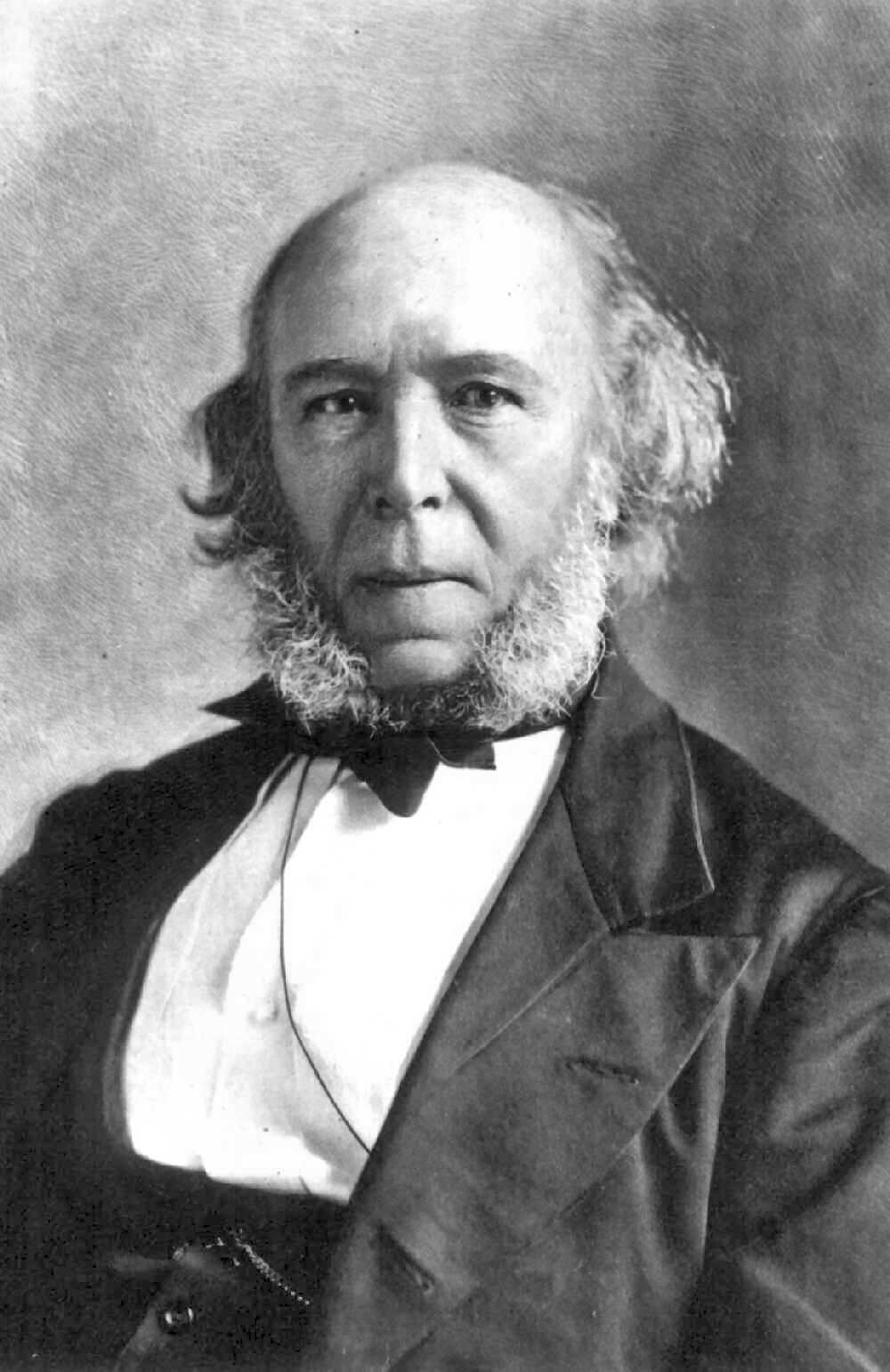

As these vast fortunes accumulated among a small number of wealthy Americans, new ideas were employed to bestow moral legitimacy upon them. In 1859, British naturalist Charles Darwin had published his theory of evolution through natural selection, On the Origin of Species. By the 1870s, Darwin’s theory had gained widespread traction among biologists, naturalists, and other scientists in the United States and had begun to challenge the social, political, and religious beliefs of many Americans. One of Darwin’s most influential popularizers, the British sociologist and biologist Herbert Spencer, applied Darwin’s theory to society and popularized the phrase survival of the fittest. Although Spencer’s assumption that human society worked by the same laws as nature was flawed, the idea took hold. The fittest people, Spencer said, would demonstrate their superiority through economic success in a free market. State welfare and private charity that prevented the “unfit” from failing would lead to social degeneration by encouraging the survival of the weak.

The wealthy and their defenders made the most of this social Darwinism. “There must be complete surrender to the law of natural selection,” the Baltimore Sun journalist H. L. Mencken wrote in 1907. “All growth must occur at the top. The strong must grow stronger, and that they may do so, they must waste no strength in the vain task of trying to uplift the weak.” Social Darwinists believed they had identified a natural order that extended from the laws of the cosmos to the workings of industrial society. All species and all societies, including modern humans, the theory claimed, were governed by a relentless competitive struggle for survival. For social Darwinists the inequality of outcomes that led some to become wealthy while others starved should be not merely tolerated but encouraged and celebrated. Inequaltity signified the progress of species and societies. Spencer’s major work, Synthetic Philosophy, sold nearly four hundred thousand copies in the United States by the time of his death in 1903. Gilded Age industrial elites, such as Andrew Carnegie, Thomas Edison, and John D. Rockefeller, were among Spencer’s prominent followers. Even some American thinkers, such as Yale sociologist William Graham Sumner, echoed his ideas. Sumner said, “Before the tribunal of nature a man has no more right to life than a rattlesnake; he has no more right to liberty than any wild beast; his right to pursuit of happiness is nothing but a license to maintain the struggle for existence.” Although Sumner seemed to imply that most strivers would never achieve their goals, many Americans focused on the positive. Massachusetts author Horatio Alger promoted the popular image of “rags-to-riches” success in stories like his bestseller Ragged Dick. Even though there were very few examples of poor boys rising to wealth and social status by honesty and hard work, the possibility of achieving the goals of life, liberty and happiness was kept alive in what became known as the Horatio Alger myth.

Not everybody welcomed inequality so eagerly. The spectacular growth of the U.S. economy and the ensuing inequities in living conditions and incomes confounded many Americans. But as industrial capitalism overtook the nation, it bought political protection. Although both major political parties state power to support the interests of capital against labor, big business looked primarily to the Republican Party. The party been formed as a coalition of an antislavery faction committed to “free labor” and the Whig Party, an ardent supporter of American business. Abraham Lincoln had been a corporate lawyer who defended railroads and a Whig Congressman before joining the Republican Party. During the Civil War the Republican national government, led mostly by former Whigs, took advantage of the wartime absence of southern Democrats to push through a pro-business agenda. The Republican congress gave millions of acres and dollars to railroad companies. Republicans became the party of business and dominated American politics throughout the Gilded Age and the first several decades of the twentieth century. Of the sixteen presidential elections between the Civil War and the Great Depression, Republican candidates won all but four. In the generation after the war, the Democratic Party was remembered as the party of slavery and Republicans regularly discredited Democratic candidates by “waving the bloody shirt” and reminding voters of the war. Republicans controlled the Senate in twenty-seven out of thirty-two sessions in the same period. Republicans used their control of government to enact high protective tariffs designed to shield American businesses from foreign competition. Southern planters had vehemently opposed tariffs before the war but could do nothing to prevent their increase. The Dingley tariff, passed in 1896 by President William McKinley, was even higher than the tariff McKinley had written a few years earlier as a Congressman. It remained in effect for twelve years and imposed duties on foreign goods that averaged 52%, the highest in U.S. history. Tariffs provided the protective foundation for a new American industrial order, while Spencer’s social Darwinism provided moral justification for national policies that minimized government interference in the economy for anything other than the protection and support of business.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did inequality between rich and poor Americans increase so much during the Gilded Age?

- Was Social Darwinism an effective justification of inequality?

- How plausible was the “Horatio Alger myth” of rags-to-riches success? Why was it so popular?

The Labor Movement

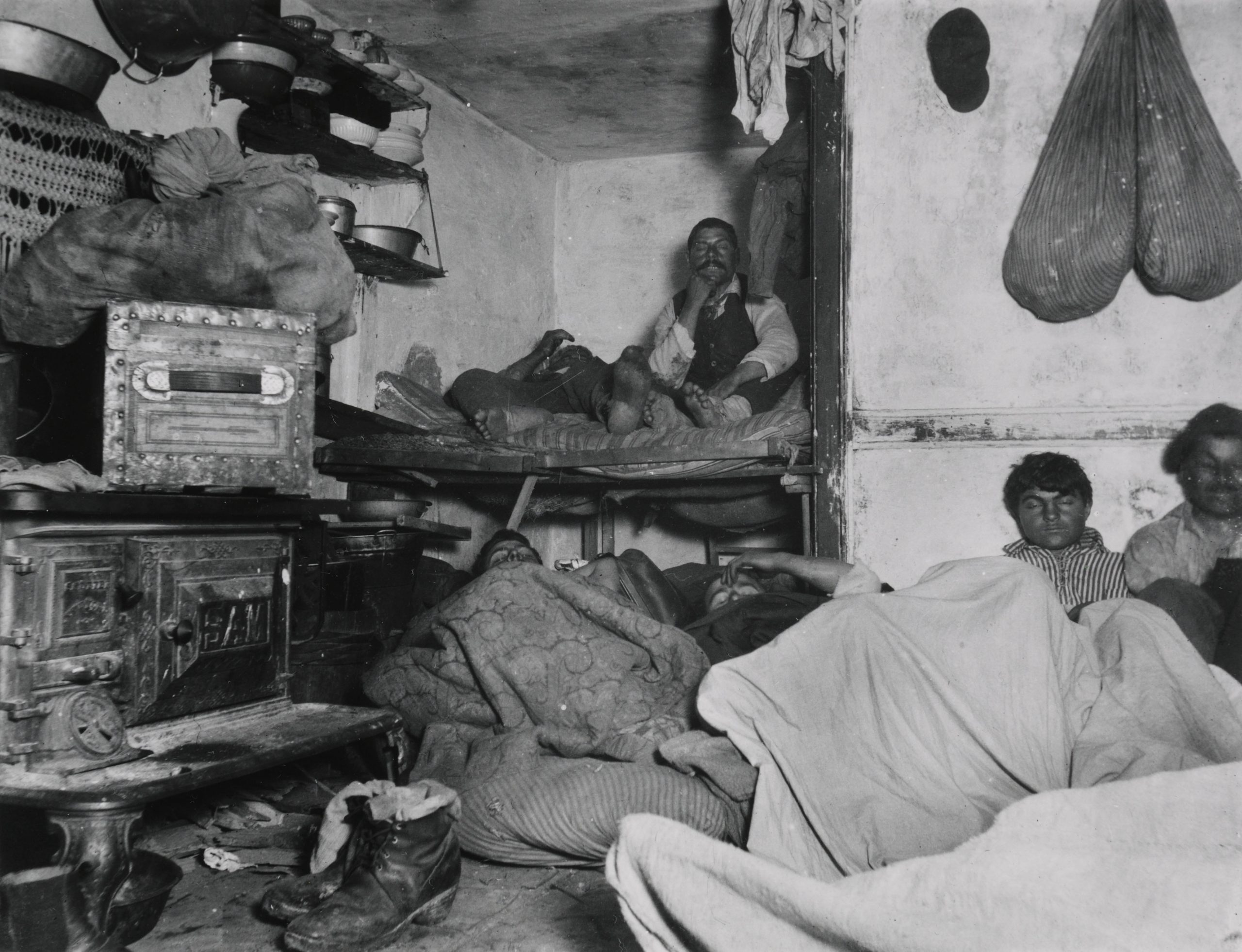

The ideas of social Darwinism attracted little support among the mass of American industrial workers. Although at the turn of the twentieth century farmers were still the largest workforce in America, industrial workers toiled in difficult jobs for long hours and little pay. Mechanization and mass production threw skilled craftsmen into unskilled machine-operator positions. Industrial work ebbed and flowed with the economy, which government and big business had failed to prevent from falling into cyclical recessions. The typical industrial laborer could expect to be unemployed one month out of the year. They worked sixty hours a week but could still expect their annual income to fall below the poverty line. Among the working poor, wives and children were forced into the labor market to compensate. Crowded cities, meanwhile, failed to accommodate growing urban populations and skyrocketing rents trapped families in overcrowded tenements.

Strikes challenged American industry throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Workers seeking higher wages, shorter hours, and safer working conditions had struck throughout the antebellum era, but organized unions were fleeting and transitory. The Civil War and Reconstruction seemed to briefly distract the nation from the plight of labor, but the failure of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 convinced workers of the need to organize. Union memberships began to climb. The Knights of Labor enjoyed considerable success in the early 1880s, due in part to its efforts to unite skilled and unskilled workers. The Knights welcomed all laborers, including women (they only barred lawyers, bankers, and liquor dealers). By 1886, the Knights had over seven hundred thousand members. The Knights envisioned a cooperative producer-centered society that rewarded labor, not capital, but, despite their sweeping vision, the Knights focused on practical gains that could be won through the organization of workers into local unions.

In Marshall, Texas, in the spring of 1886, one of Jay Gould’s rail companies fired a Knights of Labor member for attending a union meeting. Already a wealthy financial speculator, Gould had bought control of the Union Pacific when the government-supported railroad company’s stock price was depressed during the Panic of 1873. By 1886, Gould personally controlled 15 percent of America’s tracks. When the fired worker’s local union walked off the job, others joined. In Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, and Illinois, nearly two hundred thousand workers struck against Gould’s rail lines. Gould hired strikebreakers and the Pinkerton Detective Agency, a private security contractor, to suppress the strikes and get the rails moving again. Political leaders helped him and called in state militias to support Gould’s companies against their citizens. The Texas governor deployed the Texas Rangers. Workers countered by destroying property, which only won them negative headlines in newspapers under Gould’s influence. For many readers, the newspaper accounts justified the use of strikebreakers and militiamen. The strike broke, briefly undermining the Knights of Labor, but the organization regrouped and threw its support behind a national campaign for the eight-hour day.

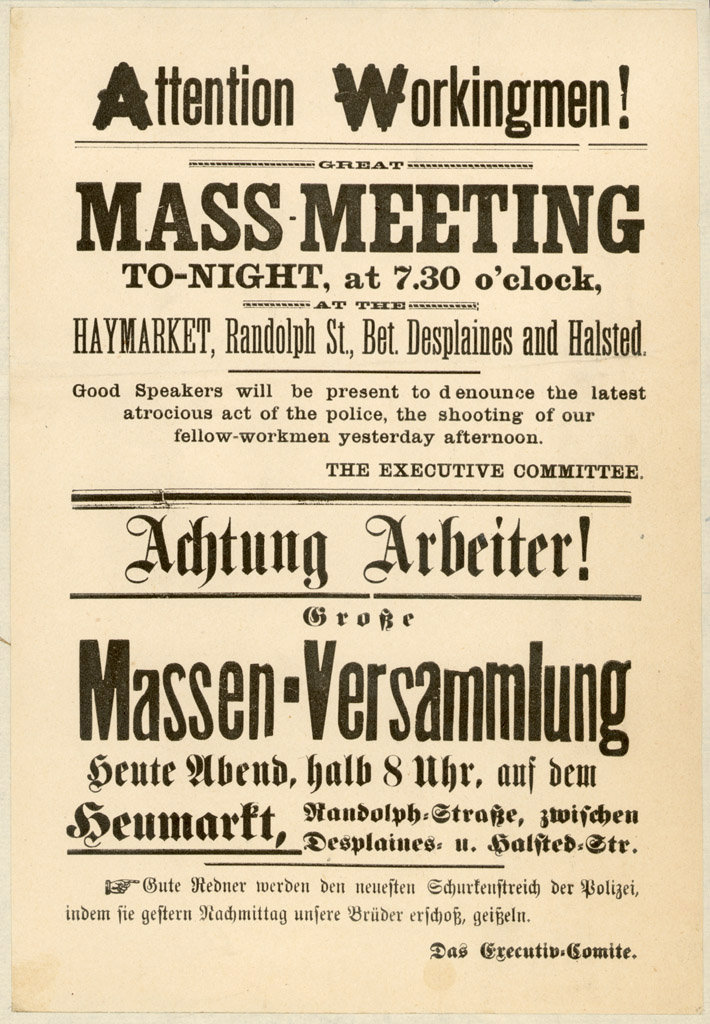

Although President Ulysses S. Grant had issued a “National Eight Hour Law” proclamation and Congress had mandated a forty-hour work week for federal employees, there were no such standards in private industry. The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (known as the American Federation of Labor or AFL after 1886) resolved at its 1884 Chicago convention that “eight hours shall constitute a legal day’s labour” and set May 1, 1886 as a start date for the new workday. When May Day came, the Knights of Labor’s national leadership did not support the change but the Knights’ Chicago leader, Albert Parsons, marched with his wife Lucy and their two children at the head of a parade of 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue, chanting “eight hour day with no cut in pay.” Over the next few days over 350,000 American workers struck in sympathy at 1,200 factories.

Chicago led the nation with 70,000 strikers. On May 3, a group of strike supporters began harassing strikebreakers at the McCormick plant in Chicago. The company called the police, who arrived and opened fire. Four people were killed and many more wounded. The following morning a protest was planned at Haymarket Square, which was attended by a couple thousand workers. Police arrived at 10:30 and ordered the speaker and crowd to leave. A homemade bomb was thrown toward the police and exploded, killing one and wounding six. Police opened fire on the crowd, killing four and wounding up to seventy protestors. An anonymous police official later told a Chicago Tribune reporter that “A very large number of the police were wounded by each other’s revolvers…[they] emptied their revolvers, mostly into each other.”

The deaths of the Chicago policemen sparked outrage across the nation, and sensational accounts of the Haymarket Riot helped many Americans to associate unionism with radicalism. Eight Chicago anarchists were arrested and, although no direct evidence implicating them in the bombing, were charged and found guilty of conspiracy. Four were hanged and one committed suicide before he could be executed. The Knights and other unions repudiated violent tactics and some suspected Pinkertons were responsible for the bomb, since the agency was known for planting its agents in unions to stir up trouble. Membership in the Knights had peaked earlier that year but fell rapidly after Haymarket as the group became associated with violence and radicalism. The national movement for an eight-hour day collapsed.

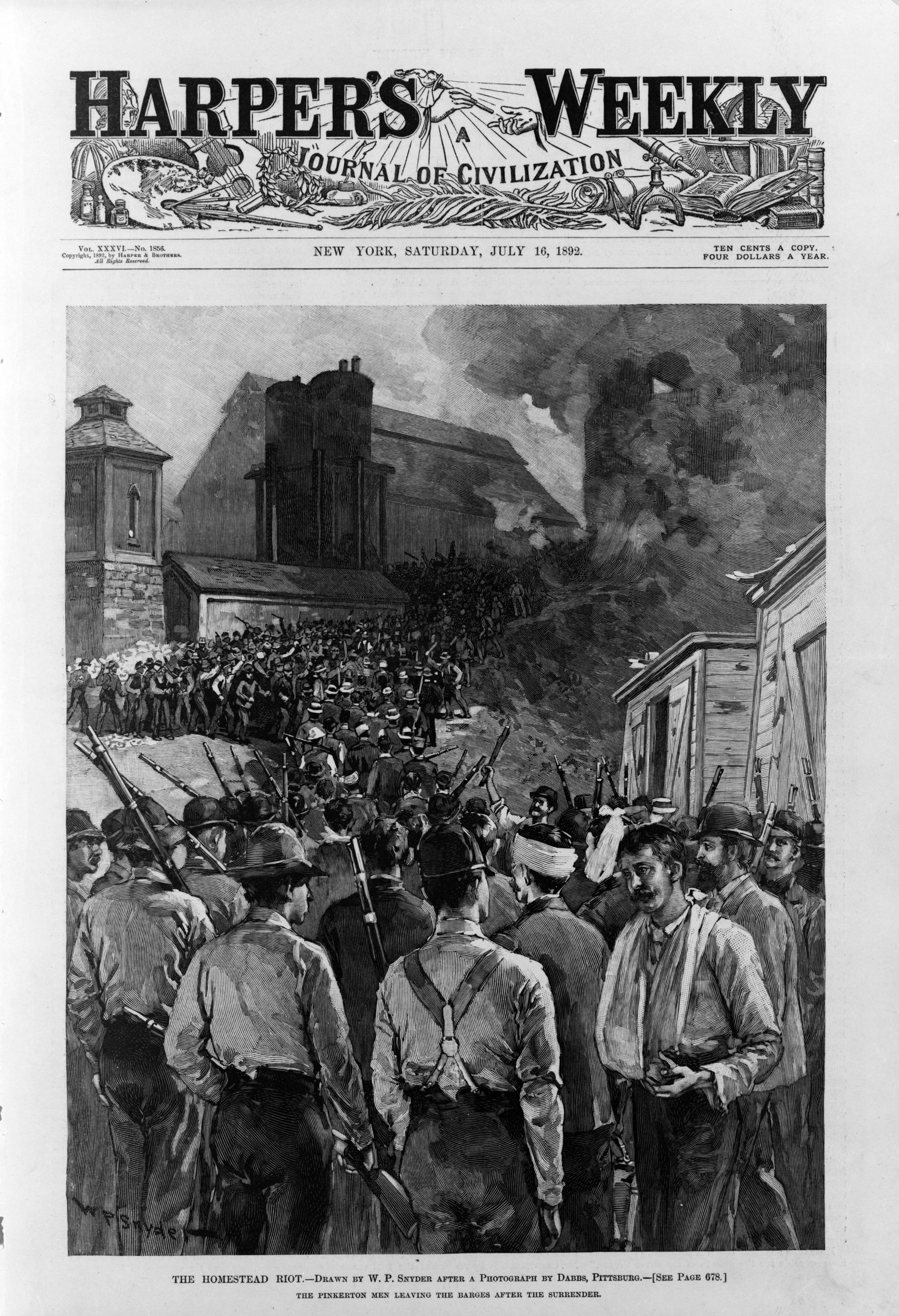

Though it had supported the eight-hour day in 1884, the newly-renamed American Federation of Labor (AFL) repositioned itself as a conservative alternative to the Knights of Labor. An alliance of craft unions composed of skilled workers, the AFL rejected the Knights’ expansive vision of a “producerist” economy and advocated “pure and simple trade unionism,” a program that aimed for practical gains such as higher wages, fewer hours, and safer conditions. The AFL advocated a less aggressive approach that tried to avoid strikes. But workers continued to strike. In 1892, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers struck at one of Andrew Carnegie’s steel mills in Homestead, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. After suffering repeated wage cuts even though protective tariffs were protecting Carnegie Steel’s profits, workers shut the plant down and occupied the mill. The plant’s operator, Henry Clay Frick, called in hundreds of Pinkerton detectives, but the steel workers fought back. The Pinkertons tried to land by river on barges provided by Frick and were besieged by the striking steel workers. After several hours of pitched battle, the Pinkertons surrendered, ran a bloody gauntlet of workers, and were kicked out of the mill grounds. But the Pennsylvania governor called the state militia, broke the strike, and reopened the mill. The union was essentially destroyed in the aftermath.

Despite repeated failure, workers continued to strike industrial corporations. In 1894, 4,000 workers in Pullman rail car factories in Chicago struck when George Pullman cut wages by a quarter but kept rents and utilities in his company town constant. The American Railway Union (ARU), led by Eugene Debs, launched a sympathy boycott in which the ARU would refuse to handle any Pullman cars on any rail line anywhere in the country. 250,000 railroad workers joined the boycott and disrupted rail transportation in twenty-seven states. Although thirty people were killed in riots and sabotage damaged property worth $80 million, the governor of Illinois sympathized with workers and refused to call in the state militia. It didn’t matter. In July, President Grover Cleveland dispatched thousands of American soldiers to break the strike, and a federal court issued a preemptive injunction against Debs and the union’s leadership. Debs was arrested and imprisoned, and the strike evaporated without its leadership. Jail radicalized Debs, proving to him that political and judicial leaders were merely tools for capital in its struggle against labor. But it wasn’t just Debs. The final two decades of the nineteenth century saw over twenty thousand strikes and lockouts in the United States. But workers were not the only ones struggling to stay afloat in industrial America. American farmers also lashed out against the inequalities of the Gilded Age and denounced political corruption for enabling economic theft.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did business find the movement for a mandatory eight-hour workday so distasteful?

- Why were strikers and protestors willing to keep fighting, when police, state militias, and federal troops regularly opened fire on them?

Immigration and Race

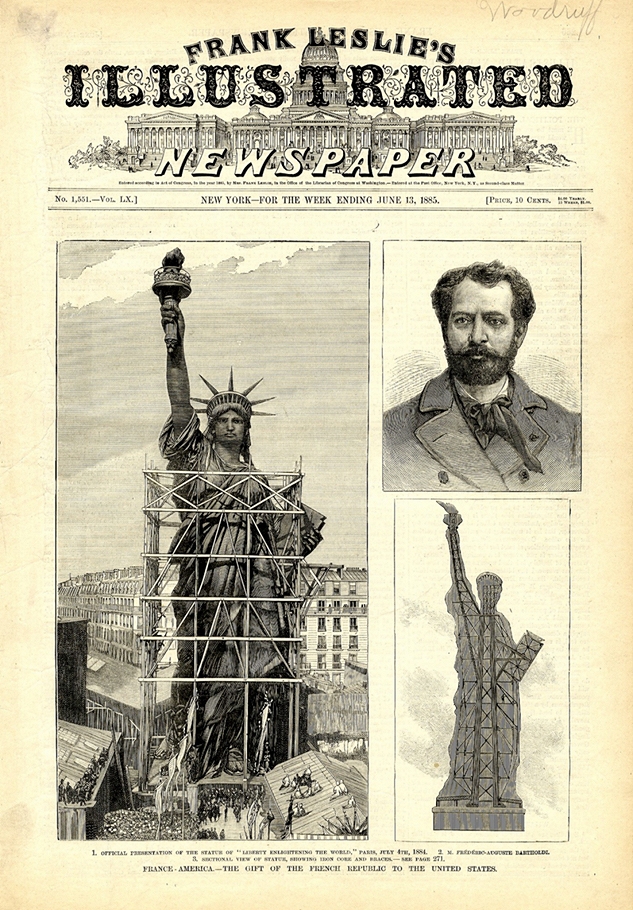

Americans celebrated in 1886 when President Grover Cleveland dedicated the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor. A million people attended New York’s first ticker-tape parade and the President promised the statue’s “stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man’s oppression until Liberty enlightens the world.” The famous poem written by Emma Lazarus to raise funds for the statue’s construction, inscribed on the statue’s base, had called to the world to “Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” But not everyone was equally excited. The Cleveland Gazette, a black newspaper, argued the statue’s torch should not be lit “until the ‘liberty’ of this country is such to make it possible for an inoffensive and industrious colored man to earn a respectable living for himself and family, without being ku-kluxed, perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed.” Throughout most of the South, Jim Crow laws and racist policies prevented African Americans from participating in society equally, in spite of Constitutional amendments guaranteeing their citizenship and right to vote. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court supported a policy of “separate but equal” in the landmark case Plessy v. Ferguson. Although black leaders like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois differed on the best approach to raise their communities to a more equal status, both agreed that ideas of white supremacy had not ended with Reconstruction.

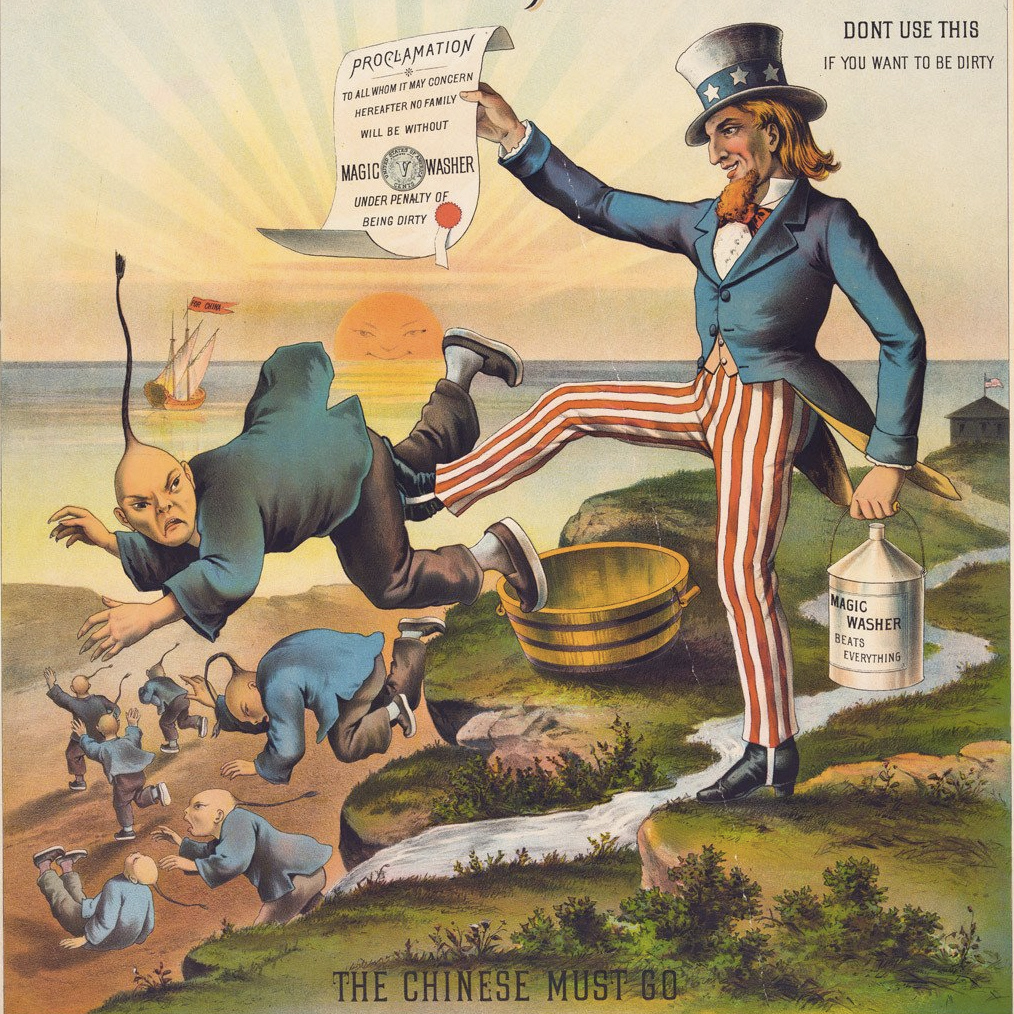

The statue’s dedication did not signal an end to the Jim Crow policies and “black codes” that enforced segregation and victimized African Americans. Nor did the statue signal a new era of open immigration. Just a few years before, Congress had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law preventing all members of a specific ethnic or national group from immigrating to the United States. Thousands of Chinese men had been recruited to build America’s transcontinental railroads, and Chinese people continued to work in mining and other low-paying, often dangerous jobs. By 1880, over 200,000 Chinese immigrants lived in the United States; many in the West. After the Exclusion Act, several western mining communities where whites blamed Chinese workers for a lack of jobs took the law into their own hands. Massacres of Chinese people in Rock Springs and Hell’s Canyon, Wyoming, in 1885 and 1887 resulted in twenty-eight and thirty-four deaths, respectively. The exclusion, originally intended to last ten years, was renewed in 1892 and made permanent in 1902. The legal exclusion of immigrants based on race continued until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Questions for Discussion

- Why were some Americans less excited about the dedication of the Statue of Liberty?

- What were some of the reasons African Americans and immigrants were mistreated?

- When did the unjust treatment of blacks and Chinese end?

Primary Source Readings

Proposed Intervention in Cuba (1875)

Excerpts from Secretary of State Hamilton Fish’s official letter to Caleb Cushing, the American minister to Spain.

Battle of the Little Big Horn from Indian Perspective (1876)

Two Moons’ account, published in McClure’s Magazine in 1898.

Henry George, Progress and Poverty, Selections (1879)

In 1879, the economist Henry George published a bestselling book exploring the contradictory rise of both rapid economic growth and crippling poverty.

William Graham Sumner on “What the Social Classes Owe to Each Other”, 1883

William Graham Sumner, a professor of sociology at Yale University, penned several pieces associated with the philosophy of Social Darwinism. In this excerpt, Sumner argues that “the rich are good-natured.”

“The Tournament of Today” (1883)

“Print shows a jousting tournament between an oversized knight riding horse-shaped armor labeled “Monopoly” over a locomotive, with a long plume labeled “Arrogance”, and carrying a shield labeled “Corruption of the Legislature” and a lance labeled “Subsidized Press”, and a barefoot man labeled “Labor” riding an emaciated horse labeled “Poverty”, and carrying a sledgehammer labeled “Strike”. On the left is seating “Reserved for Capitalists” where Cyrus W. Field, William H. Vanderbilt, John Roach, Jay Gould, and Russell Sage are sitting. On the right, behind the labor section, are telegraph lines flying monopoly banners that are labeled “Wall St., W.U.T. Co., [and] N.Y.C. RR”.”

Andrew Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth (1889)

Andrew Carnegie, the American steel titan, explains his vision for the proper role of wealth in American society.

An audio podcast version of this chapter is available here to listen along while reading or download.

References

This chapter is loosely based on Chapter 16 of The American Yawp. In its original form the chapter was edited by Joseph Locke with content contributions by Andrew C. Baker, Nicholas Blood, Justin Clark, Dan Du, Caroline Bunnell Harris, David Hochfelder Scott Libson, Joseph Locke, Leah Richier, Matthew Simmons, Kate Sohasky, Joseph Super, and Kaylynn Washnock. For this “remix”, the chapter was edited and revised by Dan Allosso, who also added new content and deleted a bit.

Recommended Further Reading

- Beckert, Sven. Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Benson, Susan Porter. Counter Cultures: Saleswomen, Managers, and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890–1940. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1986.

- Cameron, Ardis. Radicals of the Worst Sort: Laboring Women in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1860–1912. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

- Chambers, John W. The Tyranny of Change: America in the Progressive Era, 1890–1920, 2nd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000.

- Chandler, Alfred D., Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1977.

- Chandler, Alfred D., Jr. Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: Norton, 1991.

- Edwards, Rebecca. New Spirits: Americans in the Gilded Age, 1865–1905. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Enstad, Nan. Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure: Working Women, Popular Culture, and Labor Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

- Fink, Leon. Workingmen’s Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

- Goodwyn, Lawrence. Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

- Green, James. Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement, and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America. New York City: Pantheon Books, 2006.

- Greene, Julie. Pure and Simple Politics: The American Federation of Labor and Political Activism, 1881–1917. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Hofstadter, Richard. Social Darwinism in American Thought. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944.

- Johnson, Kimberley S. Governing the American State: Congress and the New Federalism, 1877–1929. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Kazin, Michael. A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. New York: Knopf, 2006.

- Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Krause, Paul. The Battle for Homestead, 1880–1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992.

- Lamoreaux, Naomi R. The Great Merger Movement in American Business, 1895–1904. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- McMath, Robert C., Jr. American Populism: A Social History, 1877–1898. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993.

- Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Painter, Nell Irvin. Standing at Armageddon: The United States, 1877–1919. New York: Norton, 1987.

- Postel, Charles. The Populist Vision. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Sanders, Elizabeth. Roots of Reform: Farmers, Workers, and the American State, 1877–1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Trachtenberg, Alan. The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age. New York: Hill and Wang, 1982.

Media Attributions

- Harpers_8_11_1877_6th_Regiment_Fighting_Baltimore © e Harper's Weekly, Journal of Civilization, Vol XXL, No. 1076, New York is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Last_Spike_1869 © Thomas Hill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1886Railroads © John Y. Huber Company is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Harpers_8_11_1877_Destruction_of_the_Union_Depot © M.B. Leiser is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Morgan,_Sam © Udo Keppler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Musterarbeitsplatz © Hebeisen, Walter: F. W. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- McCormick_Twine_Binder_1884 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sears_Magnolia_Catalog_Image is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Homestead_Steel_Hearth_3 © William J. Gaughan is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Jacob_Riis,_Lodgers_in_a_Crowded_Bayard_Street_Tenement © Jacob Riis is licensed under a Public Domain license

- William_Rockefeller_Home is licensed under a Public Domain license

- PJM_1088_01 © Rand McNally adapted by Cornell University – PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Herbert_Spencer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ragged_Dick_Frontispiece_Coates_1895 © Henry T. Coates is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Abraham_Lincoln_by_Nicholas_Shepherd,_1846-crop © Nicholas H. Shepherd is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1912_Lawrence_Textile_Strike_1 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Harpers_8_11_1877_Blockade_of_Engines_at_Martinsburg_W_VA © Harpers Weekly is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Great_Railway_Strike_1886_-_E_St_Louis © Nebinger, G. J. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- HACAT_DE1 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Homestead_riot_harpers_3c26046v © W.P. Snyder is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 940707-gwpeters-nationalguardfiring-harpers-940721 © G.W. Peters is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Leslie_Liberty © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Chinese_Must_Go_-_Magic_Washer_-_1886_anti-Chinese_US_cartoon © The George Dee Magic Washing Machine Company