Chapter 2 Scope

2

Scope

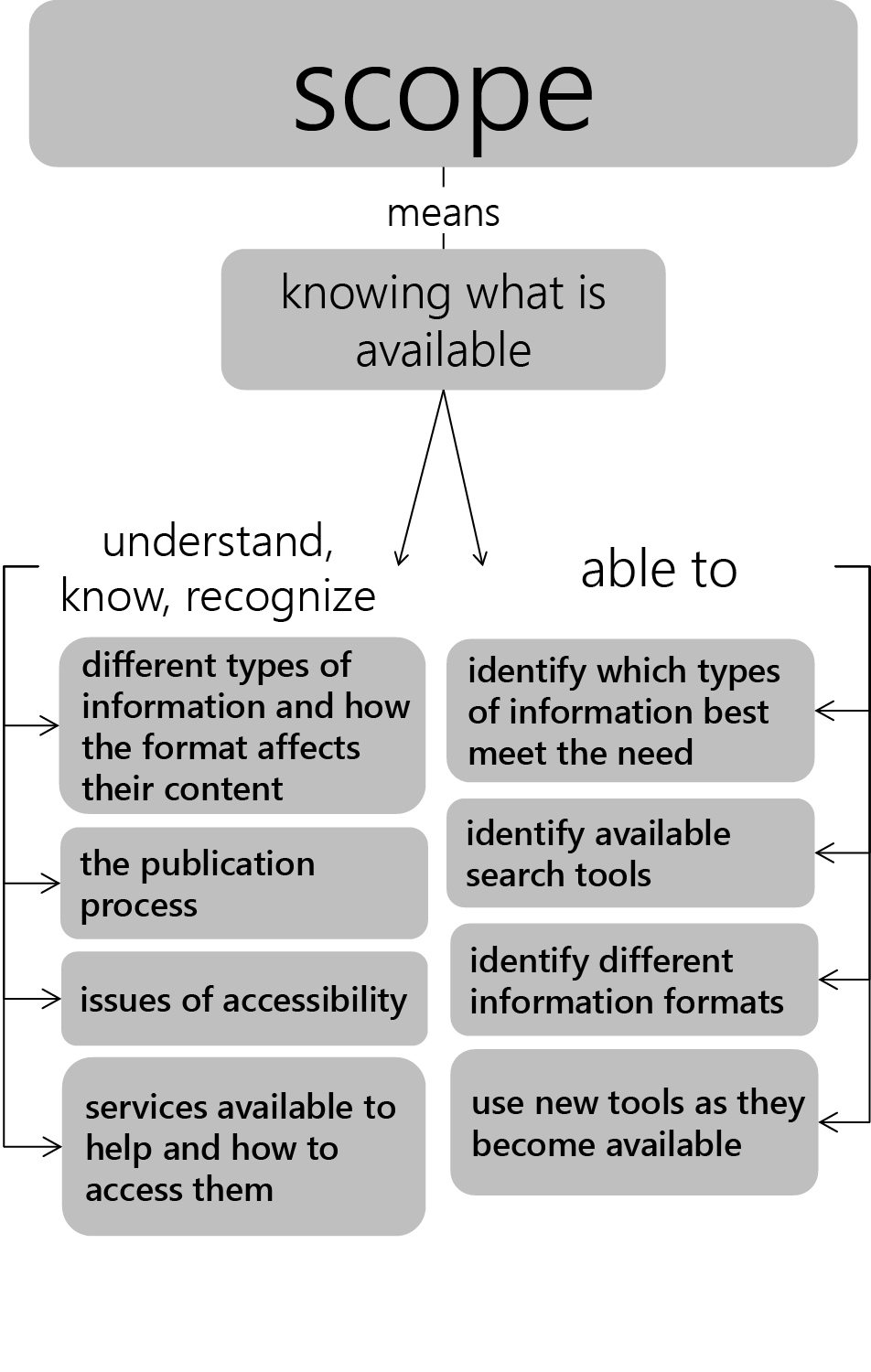

A person who is information literate in the Scope pillar is able to assess current knowledge and identify gaps.

The above statement is from the Seven Pillars of Information Literacy, the model of information literacy presented in the Introduction of this book. The following list, from the creators of the Seven Pillars model, provides more detail about the Scope pillar. Components include:

- “Know what you don’t know” to identify any information gaps

- Identify which types of information will best meet the need

- Identify the available search tools, such as general and subject specific resources at different levels

- Identify different formats in which information may be provided

- Demonstrate the ability to use new tools as they become available

Additionally the information literate person in the Scope pillar understands

- What types of information are available

- The characteristics of the different types of information source available to them and how they may be affected by the format (digital, print)

- The publication process in terms of why individuals publish and the currency of information

- Issues of accessibility

- What services are available to help and how to access them

Scenario

Mohamed is active in his Mosque and a student group for Muslims on campus. He was born into a Muslim family and lives in a community with Muslims from all over the Middle East and Africa. He is interested in how greater American society perceives the Muslim faith and to what extent it welcomes faithful Muslims into everyday life. He knows that there are kind and welcoming non-Muslims in his community and on campus, but he also sees tensions and conflicts between people of different faiths or backgrounds. Mohamed wants to put together a research paper about this topic for his Writing course, but is nervous about the directive from his professor to use academic books and scholarly journals about this topic.

The Information Cycle

In addition to knowing that you are missing essential information about a research topic, another component of information literacy is understanding that the information you seek may be available in different formats such as social media postings, news items, government information, scholarly journal articles and books. Each format has a unique value. The graphic below represents a common process of information dissemination, known as The Information Cycle. It demonstrates how information is created and disseminated across society during a period of time.

When an event happens, we usually hear about it from social networks and news sources first. These first reports are concerned with what happened. To borrow from journalists, we learn about the who, what, where, when, why and how of an event. Sometimes these initial reports get the facts wrong or frame events out of context; however, as time goes by we begin to see general agreement on what happened in news sources, on social media networks and in government or police investigations. A more in-depth exploration and analysis of the event often comes later from different government officials, talking heads across our society, journalists and scholars. We see longer formats emerge: scholarly journal articles, investigative journalism, government reports, proposed legislation and policy reviews. At this point we are beginning to make meaning out of the event. Calls for action become strengthened by understanding the context. Deeper explorations of the event tie it to larger social problems, scientific theories, legislative solutions or regulatory issues. Documentaries and books are two formats that emerge much later, as a way to document history or demonstrate how different events come together to explain various scientific, social, economic and political phenomena. Events take on greater meaning as we figure out how they fit into the big picture.

When college professors ask students to use academic books and scholarly journal articles, they are asking students to seek out information that examines, analyzes, synthesizes, scrutinizes and frames issues using scholarly perspectives, theories and research methods. As Mohamed seeks out scholarly information for his college research paper, he should think about how the specific topic he is interested in exploring fits into larger social problems, scientific theories, legislative solutions or academic disciplines. Most professors do not want a simple account of the world, they want a deeper examination. Mohamed might explore what scholars have to say about the assimilation of Muslim immigrants into American society, or how Muslims and Christians coexist in American society over time or how recent events in the Middle East have affected Muslims in America. Simple web searches do not typically lead to information that addresses this degree of complexity. There are scholarly journal articles, extensive government reports, in depth journalistic pieces and documentaries on the web; however, you have to know where to look.

Free Market Information and Filter Bubbles

Because The Information Cycle begins with an event that is disseminated across social networks or news sources, it is tempting to think this is where you should start a research project. Many of us are introduced to new events, ideas, organizations, people and places in our social networks or trusted news sources. We might even have an important news article, blog post, personal experience or podcast that inspires the research project we are interested in exploring for a class. Taking your inspiration from real life events or personal experiences is a great idea, doing research in your preferred digital ecosystem is not advisable. There are two problems with conducting research through our social networks and in web browsers: most of us lack access to high quality information and most of us are subject to algorithmic intervention when we interact with the world wide web.

When you are conducting research for a college level course, most professors require the use of peer reviewed journals or scholarly publications. These high quality information resources are not typically given away for free. Many scholarly articles can be found in a Google Scholar (or other preferred browser) search; however, when you go to the website to access the article you are given a free abstract of the article but then asked to pay for the full text. The same can be true of scholarly books, you can get a free preview but have to pay for a full text view of the book online. Scholarly information is valuable and can command high prices in the free market. If you pay for access to every article or book you want to read for a research paper, you will quickly find research to be an expensive endeavor. One way to avoid this problem is a use Open Access scholarship, which is discussed in Chapter 9 Scientific Literacy. Another way to avoid this problem is to use the resources in your school library. Your tuition helps pay for this information and it has been vetted by librarians, so you know it will be appropriate for college level research.

The more subtle problem with research across social networks and through web browsers is algorithmic intervention. Companies that provide web based services, like social media platforms or web browsers, have powerful incentives to keep you engaged with their platform or application: advertising revenue and personal data collection. Facebook, Twitter, Google and other web based service providers keep your business and increase your participation on their platforms by presenting you with content that entertains or resonates with you. They employ sophisticated algorithms to make sure you enjoy connecting with people, events, ideas, organizations and advertising on their platforms. These companies also collect as much personal information about you as they can to tailor your experience and perhaps sell this data to other companies. If you use a web based platform enough you will find yourself in a Filter Bubble, a place that presents you with agreeable and entertaining information at the expense of challenging or disagreeable information. The vast majority of free web based services or applications rely on personal data collection and advertising revenue to get and keep your business. Conducting research is this kind of environment will limit your ability to find multiple perspectives, especially perspectives that differ from your own view of the world.

Academic Libraries

Academic libraries are an important place for students to conduct research. They are not interested in collecting personal data from students or optimizing search so that students only find agreeable or entertaining content. Academic library collections are developed with students and faculty in mind. They are tailored to the academic programs, assignments and research needs of the campus. Students who become familiar with the organization and collections of an academic library will save themselves time and effort when conducting research for college classes. Academic libraries primarily collect scholarly information in a variety of formats, however you will also find information from journalists and government officials. In this way, academic libraries mirror the classroom. Professors are primarily concerned with scholarship and academic ways of thinking about the world, but they are keenly aware of how this relates to greater society.

Mohamed knows he needs to use academic books and scholarly journal articles for his paper, but it is important to understand how these required resources relate to other formats in an academic library collection. Scholarly information is published in a variety of formats, each with its own special considerations when it comes to conducting research. The following formats can be found on physical shelves and in digital searches of databases or catalogs. Consider how you might use the following formats as you conduct research at your academic library

Reference Information

In an academic library, reference information is synonymous with background information. It is the source information you use to understand the basic elements of your topic, the terminology scholars use when discussing a topic and how it fits into a larger context. Academic encyclopedias and dictionaries form the backbone of a reference collection, but you might use other primary sources or commentary collected by your academic library to learn more about your research topic. Reference collections tend to be separated from other collections physically and digitally. They are intended to be used like Wikipedia, for understanding a topic, but not necessarily as the final destination for inquiry. Unlike Wikipedia, most professors are fine with students quoting and citing academic reference resources. This is because reference resources are written or edited by academics, scholars, scientists, researchers and other experts. However, students should not stay in a reference collection if they want to go deeper into a research topic.

Books

Books have been a staple of academic research since Gutenberg invented the printing press. Most academic books come out of traditional publishers with clear editorial review policies. Research in the humanities and social sciences, which include academic disciplines such as anthropology, literature and history, are primarily published in this format. A book can cover a research topic deeper than most other information sources. Books will give you a full picture of the topic, event or controversy you are researching. They can give you the context of a research topic, detailing the history and current situation we find ourselves in. Books tend to be the culmination of long term research and investigation, so you can mine a book’s bibliography or works cited pages for scholarly journal articles, research studies, government reports, experts in the field or other books. Also, academic books give you clear connections to disciplinary thinking on a topic, giving you insight into the important academic theories, scholars, research experiments or foundational knowledge of which you should be aware.

Newspaper and Magazine Articles

Magazine and newspaper articles are typically written by journalists who report on an event they have witnessed firsthand or after they make contact with those more directly involved. Journalists focus on information that is of immediate interest to the public and they write so that a general audience can understand the content. In research, newspaper articles are often best treated as primary sources, especially if they were published immediately after a current event. Magazine articles and longer investigative newspaper articles tend to explore why something happened, usually with the benefit of a little hindsight. Writers of these long form articles rely heavily on investigation and interviews for research. Journalists tend to be equal opportunity consumers of academic, government and popular information resources. This blending of resources makes their work more accessible for students exploring a topic or looking for a direction to take their research. Newspaper and magazine articles are considered popular resources rather than a scholarly resources, which gives them less weight in academic work.

Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles are written by and for experts in an academic field of study. They typically describe original research conducted to provide new insight to an academic field of study. You may have heard the term “peer review” in relation to scholarly articles. Peer reviewed articles undergo a review process carried out by professional researchers, academics and industry experts. This group checks the accuracy of the information presented in a scholarly article and the validity of the research methods used to conduct the research behind the findings. This peer review process adds a level of credibility to scholarly articles that you would not find in a magazine or news article. Scholarly articles tend to be long and feature specialized language that is meant for an expert audience. They provide the framework for researchers and scholars to build new original research projects. Scholarly articles carry a lot of weight in scholarship and professors often require their use in undergraduate assignments.

While scholarly journal articles are typically required for students doing college level research projects, they are not a great place to start your research. By their nature, scholarly journal articles are narrowly focus on one particular study or research project. It takes several studies to start drawing conclusions about a social phenomenon, scientific theory, law of nature or other piece of the academic cannon. As a novice to a field of study, an undergraduate student should start formulating their research question, research topic, and narrow research focus before they dive into scholarly journal articles.

It is a good idea to run your research topic by a professor or librarian to get recommendations about scholars, experiments, literature reviews, ethnographies or scientific studies that might be important to your understanding of the topic. When searching databases for scholarly journal articles, it is a good idea to have a few different arguments you want to make about your topic. Having more than one argument or line of reasoning ensures that you can use different studies for different points you want to make. It also forces you to find scholarly articles that come to slightly different conclusions or design their experiments in slightly different ways.

Government Information

Some academic libraries are depository libraries for the Federal Depository Library Program and collect specific documents or publications from different government agencies, most are not. All academic libraries collect or curate government information, in print or digital formats, that is useful to their campus communities.

Government information consists of any information produced by local, state, national or international governments and is usually available at no cost. However, it can reproduced by a commercial entity with added value and cost. To use free government information, look for websites that are created by official government entities such as the US Department of the Interior, UNESCO, the State of Minnesota or the Library of Congress. You can typically conduct searches of the official websites or use databases and tools developed by a government agency to search different kinds of information. For example, the United States Congress has a searchable database of legislation and proposed bills. The US Census Bureau has a searchable database to help you explore census data. Another way to access free government information is to use web portals developed by official government agencies. Web portals are websites that bring together information of many different formats into one uniform search. USA.gov is a large federally developed web portal that brings together information and services from many different government agencies across the United States. Many academic libraries have research guides or links out to relevant government information, databases, tools and portals.

Government information can help students understand the history, policies, legislation, programs, regulations or agencies involved in a research topic. Sometimes the government is a key player in our research interests. In this case, government information can be treated as primary source information. Many government agencies conduct original research, this can be published as government reports or scholarly journal articles. In this case, government information can be used as evidence to prove or disprove a theory or hypothesis. Many government officials have demonstrated expertise and first hand experience with our research topic. In this case, government information can lend us credible expert opinion or commentary on our research topic. Government information is useful and vast, students should approach government information with a clear research topic or research question in mind to avoid overload.

How to Be a Strategic Researcher

Mohamed has been learning about how information is created and disseminated across American society and what academic libraries collect. This knowledge should help him find academic books and scholarly journal articles on his research topic. More importantly, this information should help him be strategic about what to collect and when. The first thing Mohamed should do is gather background information and develop a research question. You can review Chapter 1 Identify if you need help with topic development. Once he is focused, he has decisions to make about where to look for information on his research topic. He might immerse himself in popular magazines and newspapers to understand what the conversation about Muslims in America looks like to everyday people. He may look for an academic book that deeply explores this topic, sets up a framework for understanding this topic and maybe even points to relevant scholars or research on this topic. He will definitely need to find scholarly journal articles, but he should do that when he has several answers to his research question that he wants to verify or find evidence to support. Government information may or may not be important to his research; fortunately, he does not have to make that decision right away.

The next three chapters discuss important knowledge, techniques and skills you need to navigate the physical and digital collections in an academic library. Web browser searching is not explicitly covered, but there are similarities to academic research and you will find some direct application.