Chapter 5 Evaluate

5

Evaluate

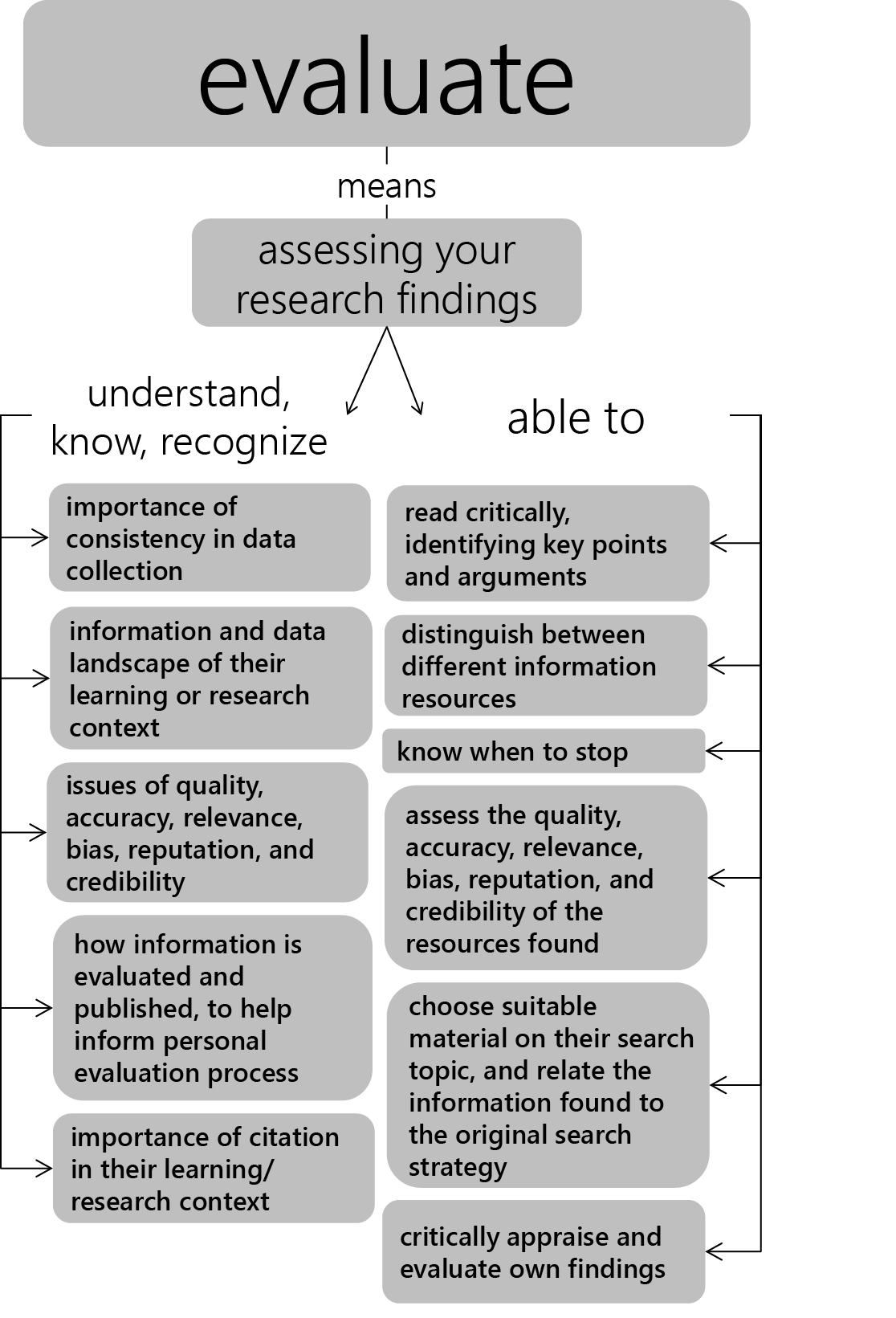

The Evaluate pillar states that individuals are able to review the research process and compare and evaluate information and data. It encompasses important knowledge and abilities.

They understand

- The information and data landscape of their learning/research context

- Issues of quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation and credibility relating to information and data sources

- How information is evaluated and published, to help inform their personal evaluation process

- The importance of consistency in data collection

- The importance of citation in their learning/research context

They are able to

- Distinguish between different information resources and the information they provide

- Choose suitable material on their search topic, using appropriate criteria

- Assess the quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation and credibility of the information resources found

- Assess the credibility of the data gathered

- Read critically, identifying key points and arguments

- Relate the information found to the original search strategy

- Critically appraise and evaluate their own findings and those of others

- Know when to stop

Scenario

Emilio has resolved to eat healthier and work out more. He just finished his first year of college and is not ready for the summer soccer season. As a nursing student, Emilio took a required nutrition course and he thinks he has the basics down. However, his feels his course work did not fully address diets for athletes with performance goals. In addition, he wants to develop a workout routine that he can maintain during the school year.

While writing a paper for the required nutrition course, Emilio learned about the health and science databases in his college library. He knows there are a lot of fad diets and “get pumped quickly” workouts on the web and he does not want to waste his time on gimmicks. He has been collecting interesting nutrition articles shared through his social media networks and he is following several fitness instructors on Instagram. Emilio is a bit intimidated, but he is going to take his research to the next level. He is going to see if the articles he found through social media are using evidence based practice. He is going to start building his nutrition and workout plan today.

Finding and Reading Resources Quickly

Most students struggle to find time to do everything. Researching an academic paper could be the kind of time consuming process that pushes them over the edge. Professors have high standards for the kinds of resources they want students to use and they expect students to cite information and use information in the right context. This chapter covers two important, but sometimes time consuming, steps in the research process: evaluation and analysis. Evaluating and analyzing resources matter when you need information to make important decisions or evidence based conclusions. These skills help you judge the reliability of resources and put those resources into action. While these skills are emphasized in academic research, they are equally useful to students making important personal decisions, like Emilio.

There are shortcuts to evaluation and analysis, which can save you time and effort. One big time saver is to use the academic library. The resources you find in databases and on shelves have been placed there by a librarian, so these resources have already been evaluated to a certain extent. Using academic resources can also save time when you starting reading and analyzing the text. Traditional academic publishing required standard formatting that has carried through to the digital age. You can use this formatting to your advantage.

This chapter will explain the concepts behind evaluating and analyzing resources. It will also outline processes and guiding questions you can use to do evaluation or analysis effectively.

Distinguishing Between Information Resources

Information is published in a variety of formats, each with its own special considerations when it comes to evaluation. Consider the following formats.

Social Media

Social media is a quickly rising star in the landscape of information gathering. Facebook updates, Instagram posts, tweets, wikis, and blogs have made information creators of us all. These platforms have a strong influence on the way we gather and disseminate information. Social media is often the first place we learn about current events or discover new items of interest. Anyone can create or contribute to social media, and there are no gatekeepers to fact check for accuracy or censor slanderous or hateful speech. So do people really use social media for research? Information Scientists might use social media for the aggregate data that is collected from users to gain insights, but this requires special training. Most other academics use social media as primary source accounts of the human experience around historic events or social phenomena. You might look for the social media posts of the politically powerful, intellectually important or socially influential to gain their insights. Eyewitness accounts and reactions may also be important sources of information for context.

News Articles

These days, social media platforms are the first place to get information about a big news story. News media often post to social media as they learn new facts and insights. Longer form news articles and reports are generated quickly as the story progresses. News articles are written by journalists who report on an event they have witnessed firsthand, or after they make contact with those more directly involved. Journalists focus on information that is of immediate interest to the public and they write so that a general audience can understand the content. These articles go through a fact checking process, but when a story is big and the goal is to inform readers of urgent or timely information, inaccuracies may occur. In research, news articles are often best treated as primary sources, especially if they were published immediately after a current event.

Magazine Articles

While news articles and social media tend to concentrate on what happened, how it happened, who it happened to, and where it happened, magazine articles tend to explore why something happened, usually with the benefit of a little hindsight. Writers of magazine articles also fall into the journalist category and rely heavily on investigation and interviews for research. Fact-checking in magazine articles tends to be more accurate because magazines publish less frequently than news media, so they have more time to get the facts right. Depending on the focus of the magazine, articles may cover current events or just items of general interest to the intended audience. The language may be more emotional or dramatic than the factual tone of news articles, but the articles are written at a similar reading level so as to appeal to the widest audience possible. A magazine article is considered a popular resource rather than a scholarly one, which gives it less weight in academic research. However, magazines can be a more accessible resource to explore why something happened.

Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles are written by and for experts in an academic field of study. They typically describe original research conducted to provide new insight to an academic field of study. You may have heard the term “peer review” in relation to scholarly articles. Peer reviewed articles undergo a review process carried out by professional researchers, academics and industry experts. This group checks the accuracy of the information presented in a scholarly article and the validity of the research methods used to conduct the research behind the findings. This peer review process adds a level of credibility to scholarly articles that you would not find in a magazine or news article. Scholarly articles tend to be long and feature specialized language that is meant for an expert audience. They provide the framework for researchers and scholars to build new original research projects. Scholarly articles carry a lot of weight in academic research and professors often require their use in undergraduate assignments.

Books

Books have been a staple of academic research since Gutenberg invented the printing press. A research topic can be covered more deeply in a book than most other information sources. Also, the conventional wisdom for books is that anyone can write one, but only the best ones get published. This is becoming less true as books are published in a wider variety of formats, which is something to be aware of when using a book for research purposes. Most academic books come out of traditional publishers with editorial review still in place. Research in the humanities, which include academic disciplines such as literature and history, is primarily published in this format.

Evaluating Information Resources

CAPPS: Currency. Author. Publisher. Point of View. Sources.

When choosing a resource for your research, what criteria do you usually use? Gauging whether the resource relates to your topic is probably one. How high up it appears in your search results may be another. Beyond that, you may base your decision on how easy a resource is to access. These are all important criteria, to varying degrees, however they may not be the best criteria when you are conducting academic research. Professional researchers and academics have criteria they use to evaluate resources as they conduct research. These criteria help them determine if a resource is worth incorporating into their project or not.

When you evaluate a source of information, you are judging it. In academic research the goal of evaluation is to make sure you use resources that are reliable, authoritative, truthful and appropriate for academic research. The following criteria outline different aspects of a resource that you should judge. Evaluation starts with the resource, but usually requires more investigation into how the resource was researched, authored, produced and disseminated.

Currency

Time has an interesting relationship with information. Currently published information is typically what we seek when conducting academic research. However, resources with older publication dates are sometimes more accurate, written by someone with more authority or created in a different context that is more relevant to our research topic. The following list of questions should be considered when you evaluate the currency of a resource you are using for academic research:

- When was this resource published or last updated?

- When was the research in this resource conducted?

- How does the date of publication influence the accuracy of the information presented?

- Does your research topic demand current information or is older information useful?

- How often is research updated in this academic discipline?

Author

The author of a resource is one of the most important criteria to evaluate when conducting academic research. The best sources of information are written by authors with expertise, which can be gained in their career, their education or through their hard work on an issue. When you select resources written by authors with high academic credentials and demonstrated expertise, your academic research project gains more authority and reliability. That does not mean journalists, activists, politicians, celebrities, religious figures or everyday people should be avoided. Resources produced by these authors should evaluated using the same questions and framework as academic authors. The following list of questions should be considered when you evaluate the author of a resource you are using for academic research:

- Has the author written other works with similar content?

- What are the author’s credentials?

- Does the author have an advanced degree in the topic they are writing about?

- Do they teach at a college or university?

- Are they a professional researcher at a university, government agency or private company?

- Are they a journalist with a long career or subject expertise for their publication?

- Do you see a bias or a particular point of view in this author’s affiliations?

- Are they a member of a “think tank” such as the Kato Institute or the Brookings Institute?

- Are they a “talking head” or someone recognized as a media personality?

- Are they associated with an activist organization that is concerned about the issues they write about?

Publisher or Publication

A publisher or publication has a great deal of influence on the resources they publish. For researchers evaluating a resource, publisher and publication websites are important places to learn about the audience, mission and editorial policies that shaped the resource. Many publishers or publications are serving a well defined audience that has certain expectations of the content. In cases where author information is scarce, publishers and publications can lend credibility to a resource or provide insight into why a resource was produced. The following list of questions should be considered when you evaluate the publisher of a resource you are using for academic research:

- Does the publisher or publication have a reputation for publishing quality information?

- Does the publisher or publication have a bias or a particular point of view?

- Does the publisher or publication have a clearly articulated editorial policy?

- Does the publisher or publication have a mission or values statement?

- Does the publisher or publication try to reach a particular audience?

- Is the publisher a university press, large commercial publisher, small publisher, or alternative press publisher?

- If the publication is a scholarly journal, do you see a mission statement that supports original scholarship or research? Do you see a peer review policy and editorial board full of experts in the field?

Point of View or Bias

Neutrality is a difficult state for humans to achieve, most resources express a point of view or exhibit bias. It is in the nature of publishing to reach a particular audience and produce something they will buy. Understanding the point of view or bias of an author, publisher or publication can help you understand the purpose or intention of the resource. You can use the point of view or bias in resources to your advantage, especially when you produce argumentative research papers. When you need to be more objective or neutral for a research project, you should seek out resources that express different points of view and come from different kinds of authors and publishers. Acknowledging the points of view or bias in your sources will help you understand your own points of view or bias. The following list of questions should be considered when you evaluate the points of view or bias of a resource you are using for academic research:

- Is the resource produced by scholars, activists, journalists, politicians, talking heads, the government or a private business?

- What is the purpose of the resource? Is the purpose to inform, entertain, teach, activate or influence?

- Is the author giving a factual report, presenting a well-researched scholarly opinion, or relaying a personal opinion?

- Who is the intended audience: the public, the politically active, students, academics or researchers?

- Does the author offer several points of view or are they focused on one view?

- Can you identify objective writing (both sides of the argument) or a subjective bias (expressing one’s own point of view)?

- Is the writing style of the author clear and understandable?

- Does the author legitimately need to use complex language because of the subject matter, or do they use complex technical language to possibly confuse the reader?

Sources

Most published resources are produced from other sources of information. You can find an author’s sources in the citations, bibliography, works cited page, footnotes, endnotes or in-text references of a resource. These sources of information show you how the author conducted their research. Scholars often dive deep into scholarly books and journal publications or conduct original research to reach their conclusions. Journalists conduct interviews, comb through government information, seek out eyewitness accounts and talk to experts in the field. Authors disclose their sources of information to assure their audience of their credibility and accuracy. A resource without sources should not be trusted. The following list of questions should be considered when you evaluate the sources of a resource you are using for academic research:

- Can you determine where the author gathered information?

- Does this resource have citations, bibliographies, works cited pages, footnotes, or in-text references to outside sources

- Is the information from original scholarly research including case studies, experiments and observations?

- Are there helpful charts, graphs, or pictures provided? What do these graphics represent?

- Is the information from journalistic investigation including interviews, government reports, think tank reports or eyewitness accounts?

- Are the sources outdated or possibly incorrect because of their age?

- Can you verify the accuracy and trustworthiness of the sources?

- Has the author gathered a comprehensive assortment of sources to support their assertions and conclusions?

Analyzing Information Sources

3E: Explore. Examine. Explain.

Analysis typically happens after evaluation, but can be an interchangeable process. Analysis is about understanding the content of a resource and relating it to your research focus. It requires close examination of the resources in question, so you can pinpoint the most relevant information and possibly narrow down the number of resources you use for a research project. The ultimate goal is to identify resources that answer your research questions and give you evidence to work with. 3E is a framework you can use to identify relevant content in your sources of information.

Explore: Analyzing Information Resources Quickly

Many academic sources of information are created with standard formatting guidelines that make it easier for users to browse and understand quickly. When you begin analyzing your resource, pay close attention to the following features of a book or article. Quickly scanning these parts of the resource can help you determine if the resource is worth pursuing further.

Introductions, Forwards, Prefaces, Abstracts

The purpose of introductions, forwards, prefaces and abstracts is to introduce the reader to the larger work. They hint at what the author is trying to accomplish with their book or article. Abstracts in particular will detail research methods used and ultimate conclusions in a scholarly article. Introductory sections can include information on why the topic was chosen, the author’s interest in the topic, why the topic is important, or the lens through which the topic will be explored. Knowing this information before diving in to the article or book will help you understand the author’s approach to the topic and how it might relate to the approach you are taking in your own research. These sections might also help you evaluate the author.

Table of Contents

Most of the time, if your source is a book or an entire website, it will be divided into sections that each cover a particular aspect of the overall topic. It may be necessary to read through all of these sections in order to get a “big picture” understanding of the information being discussed or it may be better to concentrate on the areas that relate most closely to your own research. Looking over the table of contents or menu will help you decide if you need the whole source or only pieces of it.

Indexes

Academic books often have an index or two. This is typically a list of topical terms with pages numbers to different parts of the book. These topics can help you pinpoint pages or even paragraphs about your research interest.

References, Bibliographies, Works Cited, Footnotes and Endnotes

If the resource you are using is research-based, it should list out the sources of information. Sources of information can be found within the work, these are typically footnotes, endnotes, in text citations or in text references. Academic books and scholarly journal articles usually have bibliographies or works cited pages at the end of the work, where all the sources of information used in the work can be found. This large list of sources can give you a big picture view of the research the author engaged in. Some academic books list out the sources in bibliographies or works cited pages at the end of each chapter. Newspaper and magazine articles typically mention their sources of information in the narrative of their work. That makes it a little more difficult to track down exact reports, studies or research referenced. If the newspaper or magazine article is web based, hyperlinking is a newer approach to creating in text references for the readers to look into. If you really like what an author has to say in their book or article, the references can lead you to other relevant articles, books, reports or people to look into. This is called mining the bibliography.

Examine: Analyzing Information Resources Closely

Once you have identified relevant articles, books, websites and sections of books, you need to do a more in depth analysis of your resources. Analysis can help you find answers to your research questions, solutions to your problems and logical arguments to organize your thoughts. This examination of specific resources is the most time consuming part of your research process because it requires careful reading of your resources. Often this examination is done while you are developing your final research project. Keep in mind that the overall goal of analysis is not just to present a collection of gathered evidence. The goal is to strategically gather evidence that will answer your research question. To do this effectively, you need to take time to read and examine resources.

One rhetorical framework that might help you be strategic comes from Aristotle, he gave names to three modes of persuasion: Ethos, Pathos and Logos. According to Aristotle, using these three modes of persuasion helps you develop a balanced set of arguments that can reach the hearts and minds of your audience. Below are definitions of these types of arguments and examples of evidence that might help you make this kind of persuasive argument.

Ethos:

The use of authority, expertise and credibility to persuade your audience.

- Look for experts in the field, this expertise may be attained with degrees, experience or positions of power.

- Quote experts on a particular topic, especially if they say something insightful or impactful.

- Use information, theories or frameworks created by an expert.

- Adopt the language of experts, use precise terminology.

Pathos:

Appeals to the emotions of your audience: pity, anger, fear and hope.

- Look for real world examples to demonstrate problems or solutions in action.

- Use vivid details and images to engage the reader’s emotions and imagination.

- Appeal to the values and beliefs of the reader to take action.

- Adopt the language of pity, anger, fear and hope when you need to make this kind of argument.

Logos:

Uses data, statistics, and all types of reasoning to persuade your audience.

- Look for the arguments other experts use to persuade.

- Find the context of your problem and solution: historical, social, biological, epidemiological, psychological, etc.

- Outline your arguments in different orders to see what makes logical sense or makes the most impact.

- Gather data, statistics, case studies, reports and other original research to demonstrate your points.

Another helpful way to think about logical arguments comes from the sciences. Inductive and Deductive reasoning are logical ways of thinking about cause and effect or hypothesis and evidence. Outlined below are the processes of logical reasoning and how they relate to evidence:

Deductive Reasoning:

- Starts with a broad generalization and then applies it to a specific case to affirm or disprove the generalization

- Begins with a generalization or theory

- Develops a hypothesis or solution to test or examine

- Designs and runs the experiment, develops logical statements or proofs, examines the evidence for a solution

- Proves or disproves the hypothesis with a logical conclusion from the experiment, proof or examination

Deductive reasoning is used in the Scientific Method. It is also plays an important role in philosophical logic, syllogisms are pairs of logical statements that can be used to test theories. When testing a generalization or theory, you typically need to use methods from an academic discipline like the Scientific Method or Syllogisms. The goal of this test or experiment is to reproduce the same result over and over again to prove or disprove a hypothesis. When you do informational research, you are examining possibilities or examining evidence. The nature of information makes it difficult to definitely prove or disprove a hypothesis or solution, but you can use this approach to create logical arguments explaining a theory.

Inductive Reasoning:

- Makes broad generalizations from a representative case, specific observations, set of facts or evidence

- Starts with a representative case, specific observations, set of facts or evidence

- Looks for patterns in the observations or infers an explanation for the evidence

- Ends by proposing a theory

Inductive reasoning is the opposite of deductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning should be based on a sufficient amount of reliable evidence. The representative case, specific observations, set of facts or evidence must fairly represent the larger situation or context. When conducting informational research, inductive reasoning is often used when we encounter new evidence. It can be an important process for helping us relate the little pieces to a larger whole.

There are many more ways to think about evidence and arguments. Asking professors or other persuasive people can give you more ideas. Not all of the evidence you gather will be equally relevant and good. You want stories that reveal the human dimension of your topic, expert voices to lend authority and research findings to demonstrate effective solutions. Focus on finding the best possible supporting evidence that will illustrate your research focus and help to support any argument you are hoping to make. Throughout your examination of resources, keep your research question in mind. The best evidence will always directly address your research question.

Explain: Interpret and Make the Argument Your Own

Once your resources have been critically examined, you need explain what you have learned or concluded. There are many formats for presenting research findings: written papers, visual presentations, literature reviews, research projects, oral presentations, creative pieces, art works and many more. Emilio’s nutrition and workout plan will look different from a research paper on optimal nutrition and workout findings for male athletes. Understanding the final product of your research helps structure the research findings.

Most academic research papers or presentations require a minimum of three arguments. Multiple arguments strengthen your position because an adversary has to disprove each argument to win the debate. Multiple arguments that work together can help reinforce your ultimate conclusion. Emilio, for example, probably has arguments for “high protein diets” and “low calorie diets” that he has to make decisions about. It may be the case, that these diets are not mutually exclusive and all arguments should inform the nutrition plan. It may also be the case, that the evidence for one diet plan is stronger or that more experts agree on one particular approach to nutrition. Emilio’s understanding of his research needs should help him make decisions about which arguments to seek out and ultimately adopt. If he is evaluating his resources critically and analyzing them closely, decisions about which argument to follow or use get easier.

Critical thinkers accept that information resources are not created equally. When they bring information from various resources together, they make decisions about what gets in and what gets left out. Critical thinkers make connections between resources and produce a well informed final understanding.

Conclusion

Emilio has a clear goal for his research and a good understanding of the information environment he lives in. He is willing to accept that information from his personal social networks should be verified by academic experts. Emilio is capable of developing an excellent nutrition and workout plan. However, a lot depends on his willingness to engage in evaluating and analyzing his resources.