5 The Stylistic Characteristics of Anuak Music

The music of the Anuak tribe is extensive in amount and wide-ranging in its effect on those who participate in its production. From a recorded sample of over 850 selections, I determined seven specific categories of songs that are unique in their use and function among the Anuak. These categories are: (1) Lullabies and children’s songs; (2) Love songs; (3) Marching songs (Nirnam or songs of boasting) (4) Dancing songs, Dudbul; (5) Hymns and sacred songs; (6) Songs in praise to the chief, Oberos; and (7) War songs, Agwagas. This chapter describes the textual, melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, formal, and instrumental characteristics of representative songs in each category. The audio recordings for all the selections described in this chapter can be located by tape number in the index at https://www.anuaklegacy.com/index.

The texts of the representative songs are included and represent the essential content of the song. In several instances, word-for-word translations are provided. In most cases, however, the idea of the text is present; other interpretations are possible.

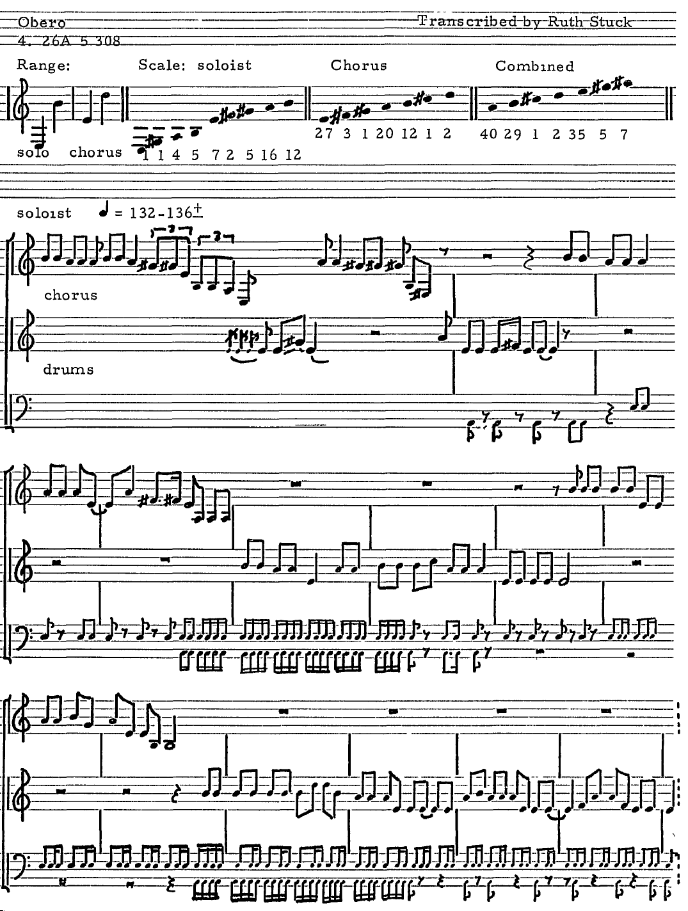

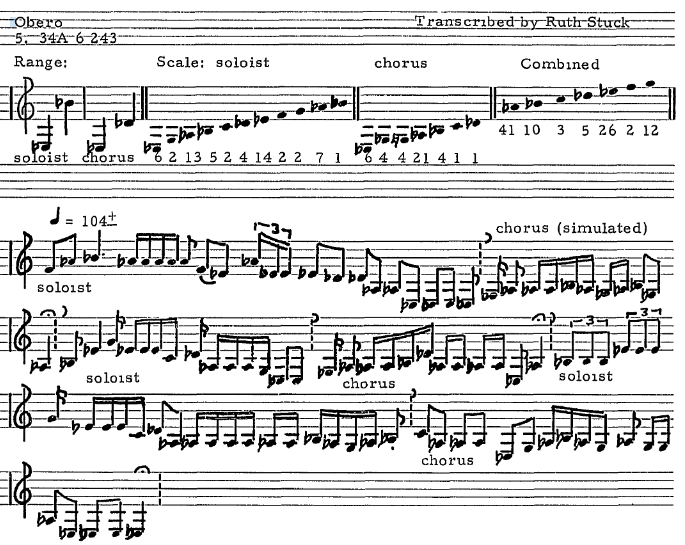

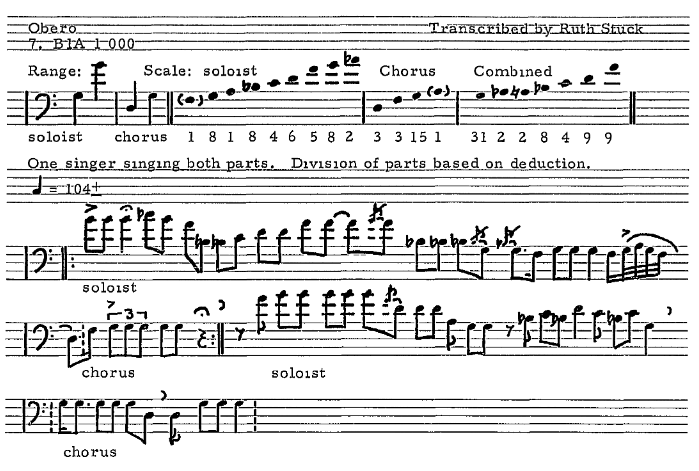

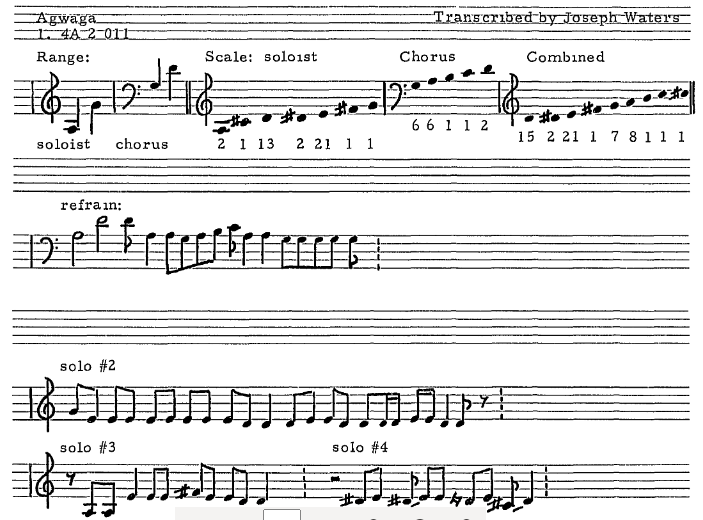

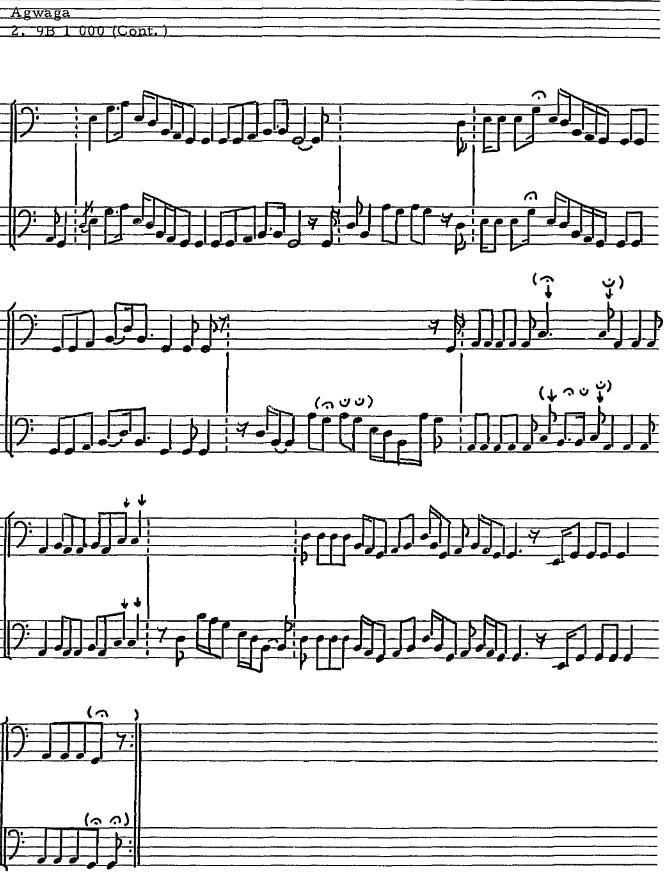

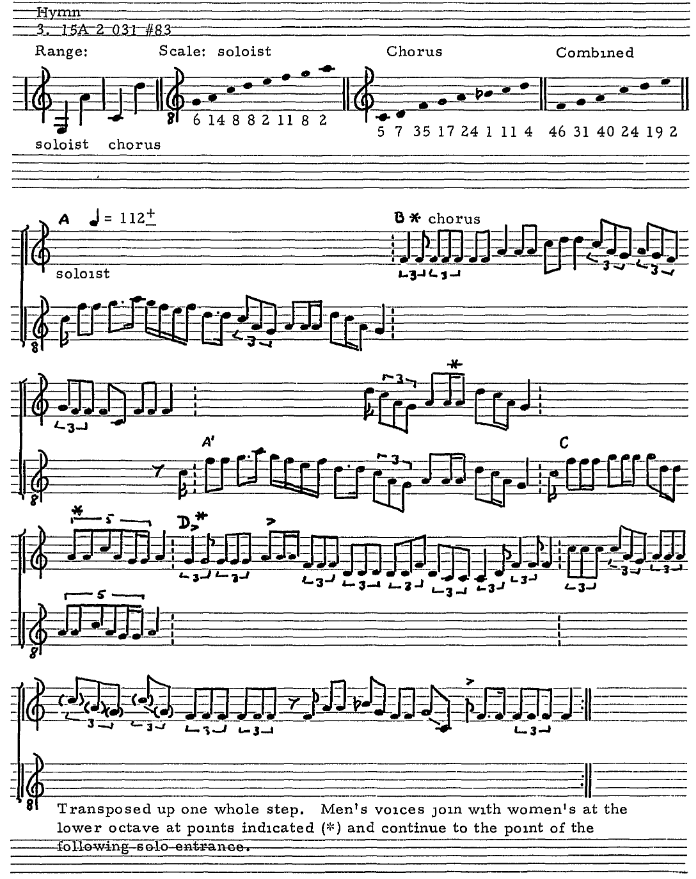

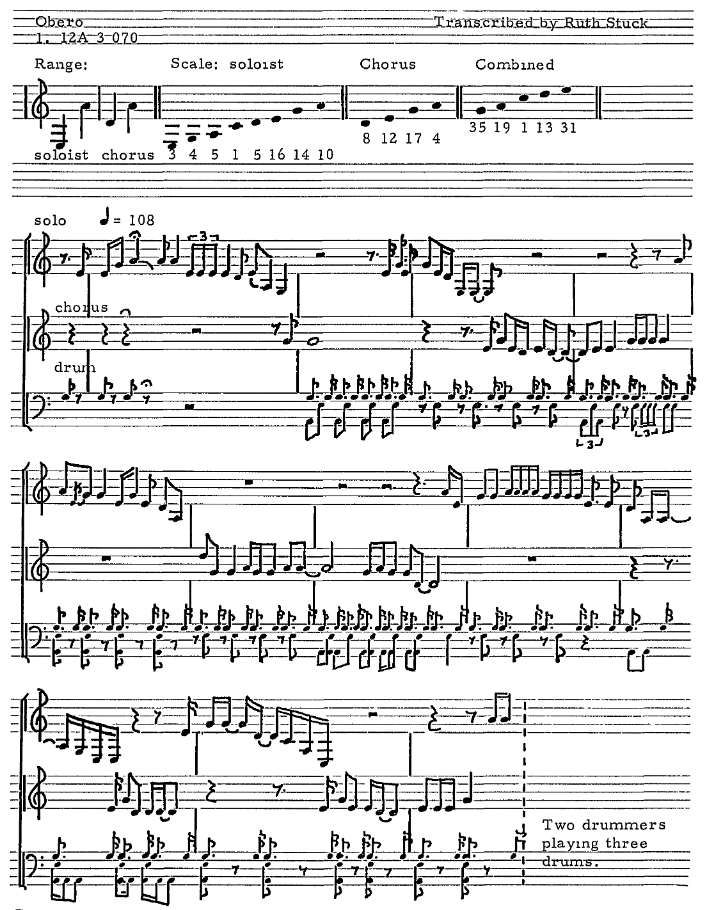

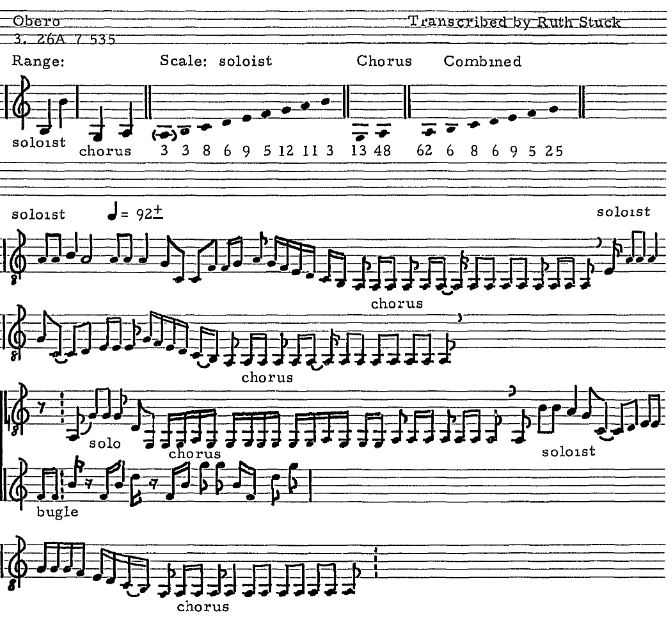

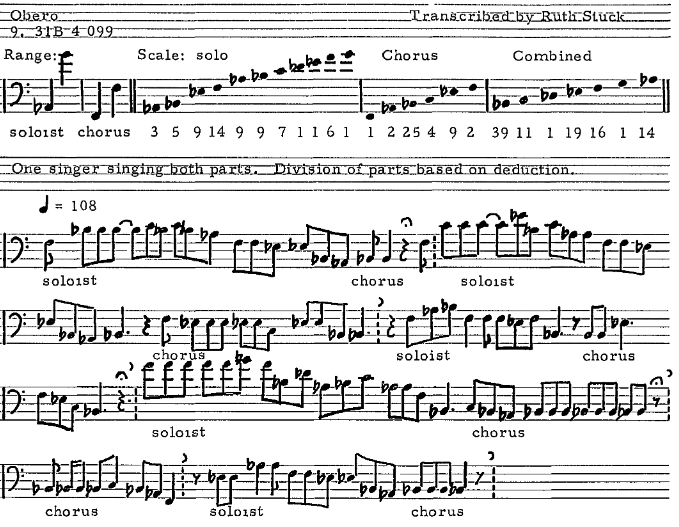

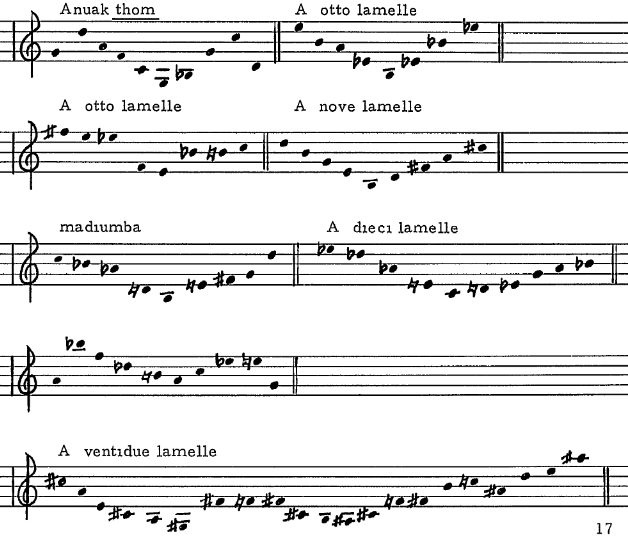

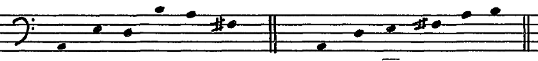

Representative selections have been notated for study and analysis. In most cases, because of the length of the songs, only the initial melodic content or the first few phrases is notated. An effort has been made to include the salient features of the selection in the notation. In several cases, the entire song is present in notation.

A brief summary of each song genre follows individual selections of that genre. An overview of instrumental usage, construction, playing technique, and general description is also included. The stylistic characteristics of Anuak music are summarized and conclusions are drawn. Comparisons are made with generalized African practice.

The following notation markings have been used in the song transcriptions:

| Time value is slightly shorter than written. | |

| Time value is slightly longer than written. | |

| Parentheses indicate that the enclosed, slightly irregular time values together make up the sum of the actual written note values. | |

| Pitch is slightly higher or lower than written. | |

| Intonation is unclear; therefore, the pitch is approximated. | |

| A note head with a tail indicates a short glissando up to or away from the pitch. | |

| A line connecting two notes indicates a melisma. | |

| Grace note. | |

| Accent. |

1. Lullabies and Children’s Songs

“It is remarkable how much similarity there is between European children’s games and the games that these children play, almost as though there were a sympathetic tie between children the world over. But it is worth noticing that we have lost much of our children’s music, as witness the number of our games which are played without song.”[1]

Tucker’s observation about Shilluk songs can also be seen in the games played by the Anuak children as well.

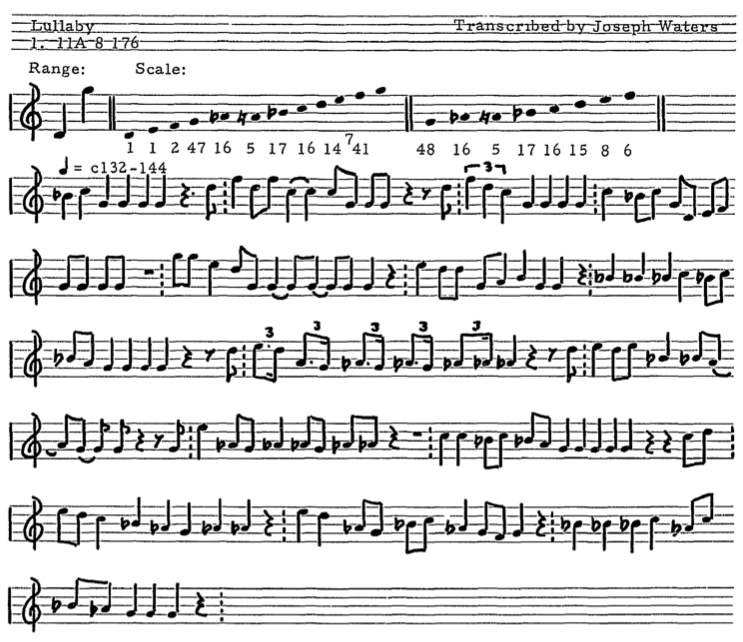

1.1. LULLABY (11A 8 176) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 11A 8 176 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 12, 1972 Date of Transcript: August 2, 1972 Source of Song: Performer: Woman soloist with rattle for accompaniment Informant: Paul Abulla |

|

Description: |

The village of Tierlul is a five-minute walk down a well-traveled path from Pokwo. Most frequently, after arriving, we sit down under a tree on the close edge of the village. On this day, we are visited by a variety of individuals, but work proceeds slowly. The woman sings this lullaby while holding the baby. Another woman provides an even pulse using a baby’s rattle. |

|

The Text: |

(This lullaby simply asks the baby not to cry. The baby’s name is mentioned.) |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: Short phrases of varying length moving downward to G. Range: D to G, Octave and a fourth. Intervals: Unisons: 38 (30%) Minor 2nds: 18 (14%) Major 2nds: 36 (28%) Minor 3rds: 10 (8%) Major 3rds: 5 (4%) Perfect 4ths: 10 (8%) Augmented 4ths: 1 (1%) Perfect 5ths: 6 (5%) Augmented 5ths: 1 (1%) Major 6ths: 2 (2%) Octaves: 1 (1%) Scale: See example. Mode: Tonality: The pitch of greatest prominence is G. An acculturative influence is suspected, possibly Arabic. Timbre: Solo woman and rattle. Texture: Monophonic. Intensity: Subdued. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

A duple feeling throughout. Tempo: Quarter note = 132-144 approximate. |

|

Form: |

A solo song possessing an improvised character. Non-repetitive. |

|

Instruments: |

A baby’s rattle used for rhythmic pulse. |

|

|

|

1.2. Lullaby (11A 9 201) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 11A 9 201 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 12, 1972 Date of Transcript: August 2, 1972 Source of Song: Performer: Woman soloist Informant: Paul Abulla |

|

Description: |

The woman sings this lullaby while holding the baby. This performance is especially for recording. |

|

The Text: |

(An authentic lullaby) This baby was given by God. (She has three children all of them girls. This is the fourth and is a boy.) |

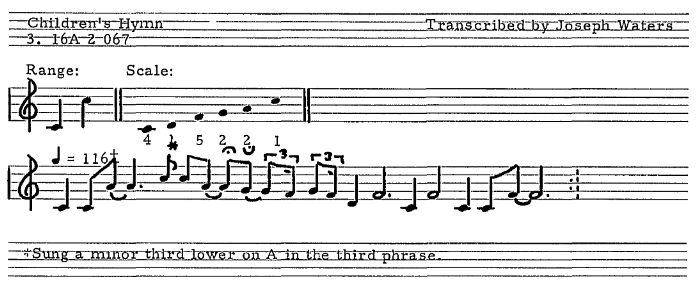

1.3. Children’s Hymn (16A 2 067) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 16A 2 067 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 15, 1972 from another recording Date of Transcript: September 23, 1972 Source of Song: Pokwo Church congregation: girls singing Informant: Paul Abulla and Henry Akway |

|

Description: |

This is a simple children’s song in praise to God. The performance is by a group of young girls singing without accompaniment in a church gathering in Pokwo. The date of the taping is unknown as it was in the possession of the missionary and re-recorded. |

|

The Text: |

Children like us love God. Children like us love God. I’m very happy. (Or the text has been translated: We love children like us.) |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: Generally downward. Range: D to D (C to C transposed) Intervals: Unisons: 1 (1%) Major 2nds: 4 (28%) Minor 3rds: 4 (28%) Perfect 4ths: 4 (28%) Major 6ths: 1 (1%) Scale: See transcription. Mode: Pentatonic. Tonality: G Major in the recorded performance. Notated in F. Timbre: Children’s voice singing naturally. Texture: Monophonic Intensity: A moderate volume with no increase in power. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

Basically, duple with uneven stress patterns. Some 6/8 swing felt. Tempo: approximately Quarter note = 116. No acceleration. |

|

Form: |

There are three repetitions of the printed phrase. There are very slight differences between them for the most part, having to do with pitch duration. One difference in pitch frequency occurs in the third phrase. The indicated C is sung a minor third lower on A. |

|

Instruments: |

None present. |

|

|

|

1.4. Lullaby (24B 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 24B 1 000 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 22, 1972 Date of Transcript: November 4, 1972 Source of Song: Probably Gok area. Performer: Solo girl singer, singing for the recording. Informant: Agwa Alemo and David Omot. |

|

Description: |

Praising the child and telling it not to cry. The child’s name is Obang, the third child. |

|

The Text: |

By your grandfather, don’t cry anymore. |

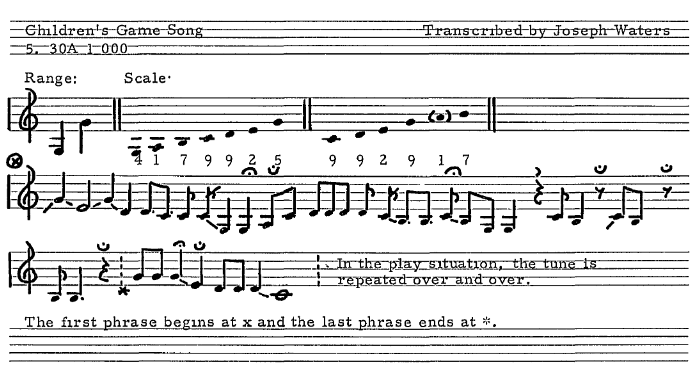

1.5. Children’s Game Song (30A 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 30A 1 000 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 24, 1973 Performers: About fifteen girls, ages nine to thirteen. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

On July 26, 1972, we are asked to come to Mary’s Bead Shop because the children have prepared to sing play-songs. They first sing the songs in the Bead Shop and then go outside and demonstrate the games which go with the songs. The recordings are made as the children play and sing. “A song for fun. Like a competition between the children.” (Informant, Alemo) |

|

The Text: |

One bird with a white crown and black body eats fish… |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: Generally downward with an up and down sing-song quality. Range: Octave G to G Intervals: Unison: 16 (43%) Minor 2nds: 6 (16%) Major 2nds: 6 (16%) Minor 3rds: 4 (11%) Major 3rds: 1 (2%) Perfect 4ths: 3 (8%) Major 6ths: 2 (4%) Scale: See transcription. Mode: Major Tonality: C (Transposed up one-half step) Timbre: Children’s voices. Texture: Monophonic, 12-15 voices. Intensity: Natural in a play situation. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

Duple. |

|

Form: |

There are seven repetitions of this phrase. In the play situation, the phrase would be repeated over and over. |

|

Instruments: |

None present. |

|

|

|

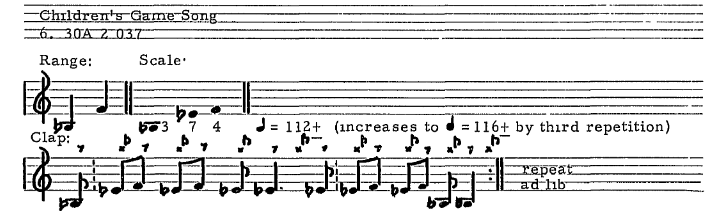

1.6. Children’s Game Song (30A 2 037) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 30A 2 037 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 24, 1973 Performers: About fifteen girls, ages nine to thirteen. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This game song would be sung with the children sitting in a circle and one child in the middle. As the children finish a singing of the chant, the child in the middle would quickly sweep her hand around the circle to catch someone who is not quick enough to draw their hand behind their back after clapping in rhythm. Anyone caught would replace the child in the center. “This kind of song is known everywhere in the Anuak area. Children play these games the same everywhere.” (Informant, Alemo) |

|

The Text: |

Mother, pull the fishing basket strongly, My mother caught fish with it. Elaboration: When the ladies fish, they use something like a basket. The men use a spear and the small children use their hands. They put their hands in the water and catch fish and will say to their mother, “Put the basket down, I caught a fish, momma.” This means that they need their mother to come to help them. (Informant, Alemo.) |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: Arc-like. Sung like a chant. Range: Perfect 5th. The range is covered in the first three notes. Intervals: Unisons: 3 (25%) Major 2nds 7 (58%) Perfect 4ths: 1 (8%) Perfect 5ths: 1 (8%) Scale: See transcription. Mode: Pentatonic implied by the limited tones used. Tonality: Eb though the children always return to Bb. The tone of greatest prominence could be the final or the second tone. Timbre: Children’s voices. Texture Monophonic. 12-15 voices. Intensity: Natural in a play situation with increasing intensity. |

|

Harmony: |

None present except for voices one octave above the notes written. The children’s voices are joined in the third repetition at the upper octave. |

|

Rhythm: |

Duple metric feeling with hand clapping providing a steady beat. Tempo: Approximately 112 to the quarter note. Very slight acceleration as intensity increases. |

|

Form: |

One well-defined phrase repeated over and over. Because the dotted quarter is vocally sustained into the second half of the phrase, this should be considered as one phrase rather than two smaller phrases. |

|

Instruments: |

No instruments are used. Hand clapping accompaniment only. |

|

|

|

1.7. Children’s Game Song (30A 3 065) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 30A 3 065 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 24, 1973 Performers: About fifteen girls, ages nine to thirteen. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

No particular game is associated with this song. Other than moving their hands in rhythm, the children use no motions. |

|

The Text: |

When the small fish are chased away by the big fish, they will jump. The bird will try to catch them one by one. The small fish are going to look for a safe place by following the currents of the river. Elaboration: A large gray bird eats the small fish. When the small fish start their journey to the north of the river, he will follow them. When the big fish try to catch the small fish, the small fish will jump and when they jump, the bird catches them. |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: The first phrase is arc-like; The second less so. Range: M6. The range is covered in the first three notes. Intervals: Unisons: 6 (33%) Major 2nds: 6 (33%) Major 3rds: 2 (11%) Perfect 4ths: 4 (22%) Scale: See transcription. Mode: Pentatonic. Tonality: C major. Returning to G gives the impression and feel of incompleteness. Timbre: Children’s voices. Texture: Monophonic, 12-15 voices. Intensity: Strong singing with increasing intensity and a resultant gradual raising of pitch level. |

|

Harmony: |

None present except for incidental singing at the fourth. |

|

Rhythm: |

Duple metric feeling with a strong pulse on every beat. No acceleration. Tempo: Approximately 120 to the quarter note. |

|

Form: |

Two well-defined phrases repeated over and over. The second phrase is one measure longer than the first. |

|

Instruments: |

No instruments are used. |

|

|

|

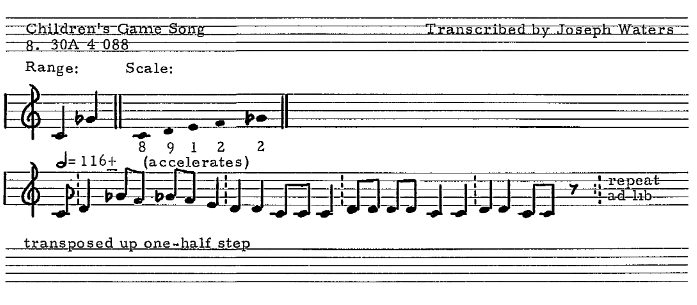

1.8. Children’s Game Song (30A 4 088) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 30A 4 088 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 24, 1973 Performers: About fifteen girls, ages nine to thirteen Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This song is fun to play. Children gather in a circle and two are selected to be in the middle of the circle. Those forming the circle will try to keep the ones in the middle from escaping. They want to find out if one is quick enough to get out. Some will never be able to escape. (Informant, Alemo) |

|

The Text: |

A small insect builds a house on the roof with mud. When the insect emerges, he is able to be swatted. He can be swatted with a horse tail swatter. |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: Arc-like; rising at beginning and gradually down at the end of the phrase. Range: D 5 Intervals: Unisons: 9 (43%) Minor 2nds: 4 (19%) Major 2nds: 7 (33%) Diminished 4ths: 1 Scale: See transcription. Tonality: C is the key center Timbre: Children’s voices Texture: Monophonic, 12 – 15 voices. Intensity: Natural as at play. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

Duple metric feel. Tempo: Approximately 116 to the quarter note, with acceleration. |

|

Form: |

The phrase is repeated over and over. |

|

Instruments: |

No instruments are used. Physical movement provides rhythmic feeling. |

|

|

|

1.9. Children’s Game Song (30A 5 118) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 30A 5 118 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 24, 1973 Source of Song: Performers: About fifteen girls, ages nine to thirteen. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This chant is repeated over and over. It is used by children when it is raining. They will jump while they sing this song. They indulge in a sort of contest of who is going to keep jumping the longest. The idea of the song is simply an expression of happiness. It has no other meaning. |

1.10. Children’s Game Song (10A 6 135) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 10A 6 135 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 24, 1973 Performers: About fifteen girls, ages nine to thirteen Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

Many children will form a circle holding hands together. They will select one person who will test the hands of the children to see who is weak and who is strong saying, Whose door is it…? Our door. Can I destroy it? Yes. The child will try to push his way out of the circle. They sometimes will not get out. But if the one being pushed against is weak, the hands will separate and they will get away. |

|

The Text: |

Who is this door? Ours. Who’s is this door? What is there? Crocodile. Will I kill it? Yes. |

1.11. Children’s Game Song (30A 7 171) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 30A 7 171 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 24, 1973 Performers: About fifteen girls, ages nine to thirteen Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

The children play with clay, making a pot, pounding it as they sing. |

|

The Text: |

This is my clay. (repeating) |

1.12. Children’s Game Song (30A 9 251) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 30A 9 251 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 24, 1973 Performers: About fifteen girls, ages nine to thirteen Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This song describes a bird with a beak and a crown. They ask the bird: “Let me see your crown…” (see below) When the children reach the last part of the song where the bird refuses to show the crown to the children, they then imitate the action of the bird. The bird tries to walk, skipping away from the children. The children will pretend as they are imitating the bird, using the same head and body movements, skipping away |

|

The Text: |

Let me see your crown. (The bird replies), No. Why can’t we see it? Because I have smoke on it. How does the smoke taste? It tastes bitter. |

1.13. Children’s Game Song (30A 11 366) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 30A 11 366 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 24, 1973 Performers: About fifteen girls, ages nine to thirteen. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This song is sung for the girls who are able to nurse from the breast. The girls will dance by shaking the upper part of their body. |

|

The Text: |

I cannot beg from somebody because I have my breasts. Those that have not developed will feel ashamed. I will not beg from somebody. (Repeated many times.) |

1.14. Summary of Lullabies and Children’s Songs |

|

|

The Text: |

Texts for children’s songs are generally short and repetitive. They stress subjects that may be taken from everyday life and may simply be an expression of happiness or an imitation of adult activity in play. The texts of game songs and lullabies give opportunity for childish play or the soothing of a baby. |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: Children’s songs and lullabies generally consists of short phrases. Phrases are either arc-like or display a generally downward contour. Range: Lullabies have a rather wide range. One example has a range of an octave and a fourth. Children’s songs range between a diminished fifth and an octave. Intervals: Unisons: (30%) Minor 2nds: (8%) Major 2nds: (33%) Minor 3rds: 8%) Major 3rds: (4%) Perfect 4ths: (12%) Perfect 5ths: (1%) Major 6ths: (1%) Mode: Pentatonic dominates with some acculturative influence found particularly in the lullabies. |

|

Harmony: |

No intentional harmony is found. |

|

Rhythm: |

A duple feeling predominates. |

|

Form: |

There is considerable repetition. Generally, a phrase is repeated over and over in the children’s songs. Considerably more elaboration and non-repetitiveness occur in the lullabies except where a small portion may be extracted and repeated. |

|

Instruments: |

Informal musical instruments are used such as a baby’s rattle. The pounding of feet and the clapping of hands provide a pulse. |

2. Love Songs

The love songs among the Anuak seem to be of fairly recent development and though popular among the young people, meet with less favor by the older. The adults believe that the singing of these songs will take the young people’s attention and interests away from the war songs and the traditional interests of the tribe. They see love songs as an indication that the young people are moving away from Anuak traditional cultural values.

The words of a love song are not too important. It is the occasion that is important. Love songs are sung in small gatherings or as the young people participate in a dance among their peers.

2.1. Love Song (6B 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 6B 1 000 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 10, 1972 Date of Transcript: July 26, 1972 Source of Song: From Gok. Composed by the singer, Olieng Ojulo. Performer: Olieng Ojulo, a 21-year-old male. Singing without accompaniment. Informants: Paul Abulla and Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. Field notes for July 10, 1972 yield information about Olieng. The singer-composer, Olieng Ojulo, is the first person to sing for us on this day. He is from Gok (Gawk), about forty miles away and is a well-known composer. His grandfather was also a composer and now he is following in his grandfather’s footsteps. Olieng states that he composes for pleasure and receives no pay for his songs. Most of his songs are love songs and are basically for dancing. |

|

The Text: |

If you agree to marry me, although I am poor, by our life we can live together. Why don’t you tell me if you refuse me? My poorness made me to sing a song. (He wants to go to a certain place with his wife. He mentions the names of his friends.) |

2.2. Love Song (8A 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 8A 1 000 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 10, 1972 Date of Transcript: July 25, 1972 Source of Song: From Gok. Composed by the singer, Olieng Ojulo. Performer: Olieng Ojulo from Gok is a 21-year-old male. He is self-accompanied on a one-gallon gasoline can “drum.” Informants: Paul Abulla and Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. Olein Ojulo accompanies himself on a one-gallon gasoline can. Placing the can flat on the ground, he plays it with his hands using a highly rhythmic accompaniment similar to that of a western bongo player. One finds the use of such a can or a large gourd for accompaniment to be quite standard in the performing of love songs, particularly in small groups. Such accompaniment provides much less volume and the instruments are much less cumbersome than the drums of the village. One need not ask the chief for permission for their use nor do they attract undue attention. |

|

The Text: |

I heard that my girlfriend went to Gilo River. So, I hope that she will be back. |

2.3. Love Song (10B 5 122) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 10B 5 122 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 10, 1972 Date of Transcript: July 25, 1972 Source of Song: from Akobo, Sudan Performers: Two girls, about 16 years old: Awiti Ojulo from Tedo and Awill Akway Informant: Paul Abulla |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. There are several themes that continually appear in love songs. The full implications of these themes become clearer when one studies the marriage practices of the tribe. Informant, Paul Abulla, mentions some of these problems as he transcribes the words of the song. |

|

The Text: |

When I sleep, I dream about my boyfriend. (When a girl is given to a rich man and she doesn’t like him, he will beat her until she is harmed. She may have a hand broken or something of this seriousness.) Her husband went to a certain place and nobody knows whether he is going to come back or not. (This one song probably includes the problems of several people. One is married to a rich man that she doesn’t love and another who doesn’t know if her husband will return or not.) When I see somebody who is not educated, I don’t like him. (Perhaps somebody who doesn’t know how to behave or has bad manners.) If you refuse me, please tell me so that I can get a better one. (This part is included in all love songs. The same words and melody crop up over and over: ma ne eni ouwar ba chani go, ana cito ki orro gonno mi kaatha ciri. “It would be better to tell me. I’m going to look for demoui.” |

2.4. Love Song (20B 4 036) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 20B 4 036 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 20, 1972 Date of Transcript: September 27, 1972 Performers: Young fellow about 14, Nyigwo Nyang, with a girl about 16, in the background. They are both from Gok. The boy accompanies on the one gallon can “drum.” Informant: Paul Abulla and Henry Akway |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. The young fellow, Nyigwo Nyang, sang throughout the day with excellent enthusiasm and style. Many of the songs sung were short, praising themselves. This song is a love song that was heard many times. Frequently, the other versions were short and included the chorus only. This is an excellent and complete version of the song. |

|

The Text: |

I have sent a letter to you. She has been asked, “Why do you disturb your mind with him?” He said, “A poor man goes out to different villages to trade till he gets something to pay.” A rich man wants his way to be prepared. Then he will come and pick up the girl without working any hardship for her. If you have refused me, why don’t you tell me. I have found another one. He looks like a prince. I didn’t know he was that poor. |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: A complex song generally on two planes throughout. A high statement is answered at approximately a fifth to an octave lower. Range: Two octaves: C-C. Intervals: Unisons: 195 (38%) Minor 2nds: 4 (1%) Major 2nds: 171 (34%) Minor 3rds: 48 (9%) Major 3rds: 2 (-%) Perfect 4ths: 60 (12%) Perfect 5ths: 16 (3%) Minor 7ths: 1 (-%) Octaves: 11 (2%) Scale: See example. Mode: Pentatonic. Includes a melismatic quality. A non-Anuak influence implied. Tonality: C Timbre: Youthful full voice of a boy of about 14. Texture: Solo unchanged male voice with the soft singing of a female in the background. The male accompanies the performance on a one gallon can “drum.” Intensity: Free and full. Open quality, not strained. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

A duple feeling throughout. |

|

Form: |

A call and response form is implied. |

|

Instruments: |

A one-gallon gasoline can is used as a drum. |

|

|

|

2.5. Love Song (20B 15 258) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 20B 15 258 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 20, 1972 Date of Transcript: September 27, 1972 Performers: Nyigwo Nyang, male about 14 with a girl singer about 16, both from Gok. The boy accompanies on the one gallon can “drum.” Informants: Paul Abulla and Henry Akway |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. This is a very clever duet. The boy sings a phrase and the girl echoes the phrase. |

|

The Text: |

I have gone to foreign lands and inside the forests, but I’ve decided that the best is to go to the Anya Nya and join them. All the Anuaks refer their problems to me. Where could I get this store of properties. I better go to the forest. You could trade a gun. It’s just like wood. Telling the girl: May God bless you. It has been exposed to everyone. The girl replies: Yes, exposed to the public. Boy: Stay, God will help you. Girl: You stay, you will be helped by God. Stay, but after ten years, if you don’t get anything to pay for the dowry, I better give myself to the government. Boy: Even me. I will give myself to a rich person that will get me some demoui and pay for the dowry. Repeats. |

|

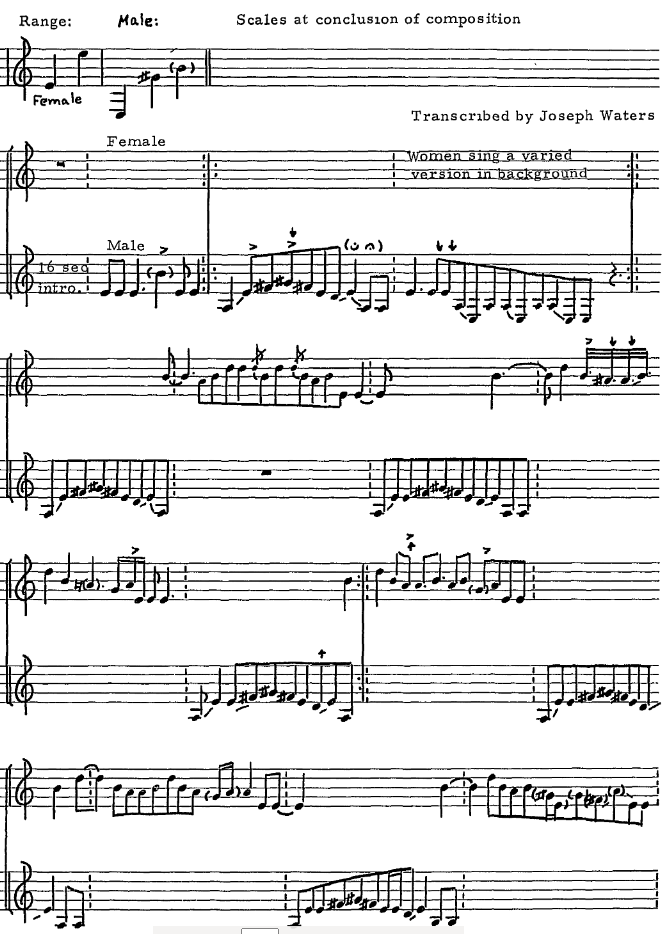

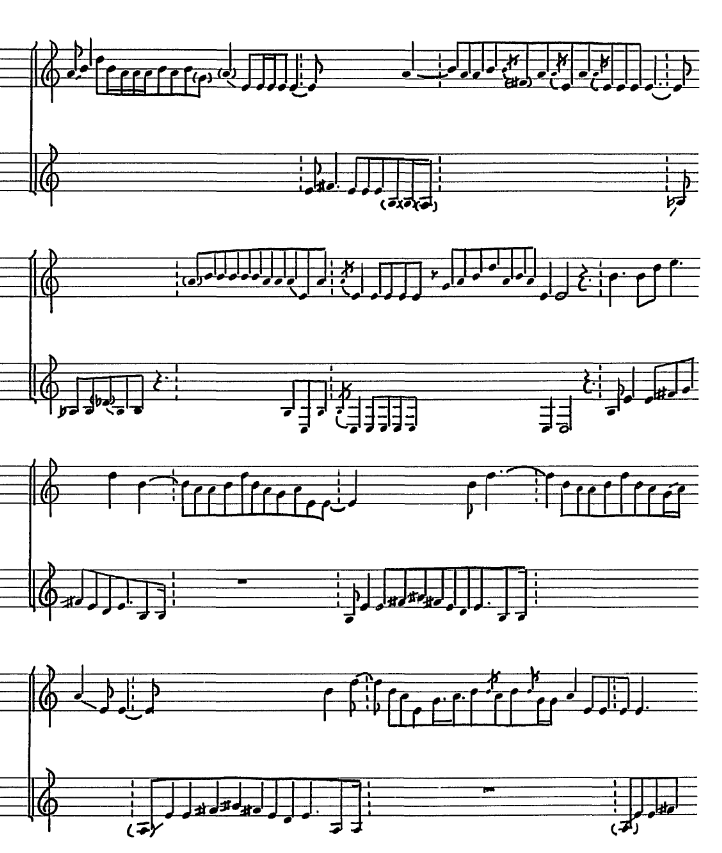

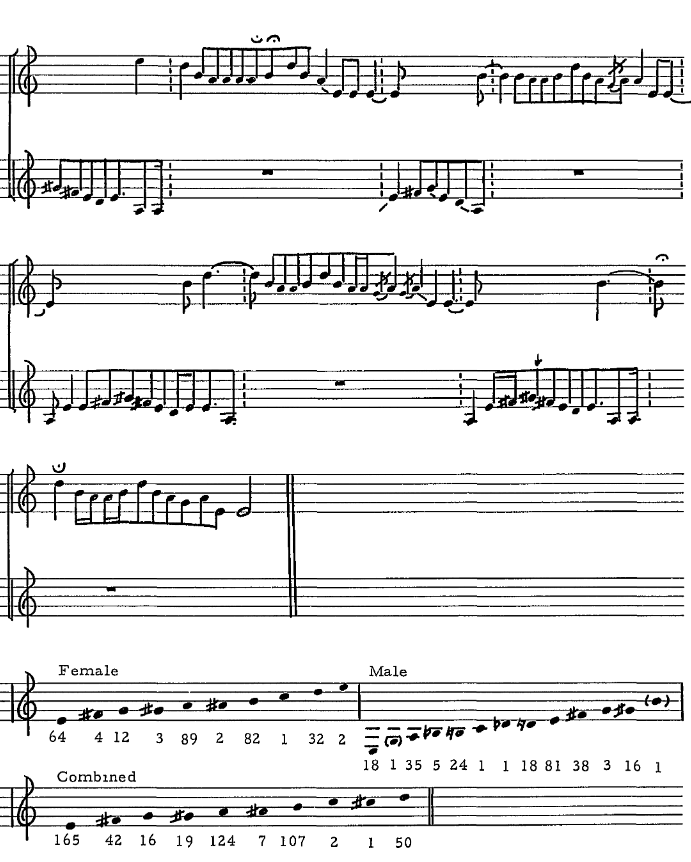

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: Short arcs. Range: Female: E-E one octave; Male: E-B one octave and a fifth; Intervals: Unisons: Female: 83 (28%) Male: 65 (27%) Minor 2nds: Female: 3 (1%) Male: 2 (1%) Major 2nds: Female: 86 (29%) Male: 111 (45%) Minor 3rds: Female: 69 (23%) Male: 7 (3%) Major 3rds: Female: 4 (1%) Male 1 (-%) Perfect 4ths: Female: 31 (11%) Male: 26 (11%) Perfect 5ths: Female: 17 (6%) Male: 30 (12%) Octaves: Female: 1 (-%) Male: 1 (-%) Mode: Pentatonic. A high degree of ornamentation in the female part implying an acculturative influence. Tonality: E Timbre: Unchanged male voice and youthful female voice accompanied on a one gallon can “drum.” Texture: A duet. Two separate parts interweave. This example is very unlike any other example recorded. Drum accompanied. Intensity: Free and full singing. |

|

Harmony: |

The only example discovered of harmony among the Anuak. Overlapped portions include unisons, octaves, fifths, sixths, and fourths. Horizontal harmonies. |

|

Form: |

A call and response pattern. The brief calls are short, straightforward and often repeated. The responses are also repeated and in addition are ornamented and melismatic. The responses differ from the calls. |

|

Instruments: |

The male singer accompanies the duet on a one gallon can “drum.” |

|

|

|

2.6. Love Song (20B 19 367) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 20B 19 367 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 20, 1972 Date of Transcript: September 27, 1972 Source of Song: Probably Gok Performers: Nyigwo Nyang, male about 14 with a female singer about 16, both from Gok. The boy accompanies on a one gallon can “drum.” Informants: Paul Abulla and Henry Akway |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. This duet is sung with great rhythmic drive. |

|

The Text: |

When I slept by night, I didn’t sleep. Because of what I had been thinking of, I dreamed. Plans have been destroyed by the old man. But I’m still thinking alone. (Praising the girl.) I am poor. I came from a different place, from a foreign land. A person like me has to be poor. You tell Akwata, I heard that her greeting has reached me. (Praising Akwata) I’m going to sing a song for her where she goes. (Informing another girl): Tell that girl that properties are like water, in which everybody is in need. So am I and I’m sure I will get it in the future. A rich man gives a dowry as if he is tired of them. |

2.7. Love Song (29B 7) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 29B 7 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 19, 1973 Source of Song: Probably from Gok Performer: Gilo Akway, 20–23-year-old lady with leprosy. Can “drum” accompaniment. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. A love song does not have the same exactness about it as does an Obero or Agwaga. They are often mixed together; a portion from one love song may be joined with several others. Or the singer may sing the first part of the song, mentioning the names of the people, come to the ending and say, “I send my greeting and a letter to you, “pause for a moment and then repeat from some part of the song. The occasion and the individuals present will help to determine the performance. Informant, Agwa Alemo, reported that the old men are not pleased with these love songs, which they consider modern. They do not have the same respect for the modern dancing songs as they have for the war songs. The old men fear that the young people will not be willing to face war if it comes. They want the young people to like war as the older generation does. The young people’s preference for the love songs is another indication to the older ones that they are moving away from cultural values. The content of this love song resulted in a discussion of the Anuak’s relation with the Ethiopian police. Agwa Alemo stated that it is a common idea that, “If I go to be a policeman in the government in Ethiopia, they will not give me a rank or a good place to be. The government will send me where there is a war.” This is what is commonly done. Anuaks are separated. They do not serve together. An article from Mussolini’s time said that if Anuaks are together, they will cause trouble. During Mussolini, four hundred Anuaks came to fight against him in Addis Ababa. When they lived in Addis, many were given a rank. When they walked in the town, the people used to abuse them with slaps because they fought with the Gallas. Those who were given rank were taken out and went to the palace and the rank insignias were burned. His Majesty gave them the ranks, but the Anuaks became very angry and took the ranks off themselves. Many of them died on the way back to Gambela. They fought Gallas on the way. Still, a few are still alive in Addis. If the young generation wants to be in the police, they will be brought directly from Gambela to the Ogaden Desert where there is a war with Somalia.” |

|

The Text: |

I’m finished with thinking. But there is no other way unless I go to be a policeman. If the rich man loves with you, it doesn’t mean that he really loves you. Repeats: (This song is mixed with a song in which my informant, Paul Nyinyoni, is included.) The girl replies to all the people: If he was to go somewhere, everyone knew it. I heard of the coming of Nyinyoni to the Gilo River. (The first part of this song is from Gok and the last part is from several places. The song is repeated.) (Insulting a rich man): If your daughter is keeping away from a rich man’s home, you will take her to a far village and give her to someone who is very rich also. (The lover of the girl mentions): My love became like a mirror which you can see your face. (Meaning, my lover has been seen or used by many different people.) |

2.8. Love Song (31B 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 31B 1 000 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 27, 1972 Date of Transcript: March 10, 1973 Source of Song: Village of Owelo. Performer: Composed by Nyinyoni (not my informant). Nyigwo Nyang, male, about 14, accompanying himself on a one gallon can “drum.” Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. This taping was done on a bright, pleasant day, sitting under a tree in Tierlul. Many singers were sitting around and shared the work of singing. One of the most rewarding singers was this young man. He sang love songs with drive and great vitality. |

|

The Text: |

I’m going to where there are no villages, to look for a dead elephant. And I advise those that don’t have parents, father and mother, not to marry. When I made myself proud about the girl, I thought I was making it for myself, and I did not know she was going to be taken by a rich man. (Saying about a beautiful girl): If she wants to come to visit, we can cut the grass so that she can come easily to our station. I’ve spent much money because I didn’t know that she was going to agree with me. (The singer insults people who have much money.) Tell her that even though you are married to a rich man, I’ll wait for her. She’s lovely and needed by many Nuers and Anuak because she looks very beautiful. |

2.9. Love Song (31B 10 641) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 31B 10 641 Place of Recording: Peno Date of Recording: July 28, 1972 Date of Transcript: March 10, 1972 Source of Song: Peno or Tedo, by Nyinyoni (Not my informant) Performers: Nyinyoni, accompanied by player on gourd and player on two bottles Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. The Field Notes for July 28, 1972 set the scene for a memorable day of travel and recording. “9:40 a.m. We leave Pokwo, heading downstream to Peno. It is cloudy with a hint of rain. A cool traveling day. “10:20 a.m. We stop at the police post in Etung and check in with the Amhara Lieutenant to inform him of our destination. “10:40 a.m. We arrive at Peno. We land at a clear, flat area and sit with the men, the Jo Burra. Paul Nyinyoni first holds conversation with the fellow we have come to see, Nyinyoni Ajwiar from Owelo. Being friends, they discuss the injuring of the chief by one of the Anyo Nya while being drunk several days before. “11:15 a.m. Taping session begins with Nyinyoni seated in front of us. The chief seated on a raised section under a tree, the men of the Burra watching in a circle, they younger boys at a distance under the shelter of a house roof, close enough to do whatever the Jo Burra requests. (If they fail to, they will be fined a goat or more or whipped.) The women and children are seated at a distance by the houses. Nyinyoni is a song composer of great repute and also a person who has traveled around to a great extent within the tribe. So, his songs have been composed in a variety of places at a variety of times. “Nyinyoni wants to find a drum or a tin for rhythm, but has difficulty. Soon a man with a gourd and a man with two bottles–a beer bottle and a mineral water bottle–arrive and form the accompaniment. The gourd is played as a drum and the bottles are played alternately pounding them on the ground, causing two different pitches to sound. The placing of a finger over and then off the top of the bottles also causes a pitch change.” |

|

The Text: |

(Saying about a man who has much money): A poor boy who shares a girl together. The girl took the poor. Repeats. That girl took a poor boy. When a poor boy went to the gold mine, his wife was taken by a rich man. (The poor boy sends back a greeting to his wife.) Though I’m far from you, I can see you in my mind, going to Gambela and going to Gilo River. Those rich people, they are greedy. They don’t sympathize with any person. They don’t eat in a group, but they eat by themselves. |

2.10. Love Song (32A 12 795) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 32A 12 795 Place of Recording: Peno Date of Recording: July 28, 1972 Date of Transcript: March 17, 1973 Source of Song: Tedo. Written by Nyinyoni in about 1966. Performers: Okelo, a young man of about 18, accompanied by gourd and bottles. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This performance was at the request of the investigator. The performance of this love song took place in the setting described for love song number 9 31B 10 641. Each love song may be different, but the themes remain quite constant. |

|

The Text: |

(The singer mentions his friends who are poor like him. They left their villages in the same year.) He says: God, who creates the girl very nicely, straight and well-built. (Mentions the leader) When the leader was invited to another village, I went with him. When we reached where we were invited, I saw many friends and the girl whom I was in need of. People were saying, “You are welcome to join our group.” And you say, “Thank you very much,” to the invitation to join the group. (The girl whom he was wanting to marry talked with him): What do you think now? (He asked) The girl answered, “I want my father to die so that we can skip away.” She continued, “We better go to the gold mines so that we can work together to get the money of the rich person easily.” |

2.11. Summary of Love Songs |

|

|

The Text: |

The texts of love songs are generally short and repetitive and allude to several subjects. Love songs comment about the poor man who has to work long and hard to get his dowry, contrasting him with the rich man who gets what he wants without trouble and does not appreciate what he has. The rich old man takes the girls away from the poor young men. The young man loses his love because of a lack of dowry and his plans are destroyed by the old man. A dominant theme of love and lost love quite accurately reflects actual courtship problems among the tribe. Love songs may also include the names of the young people and therefore form a way of praising each other. But the dominant theme of love songs is the need of the young for marriage wealth so that their love objects will not be taken by the old and/or rich men of the village. |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: The examples analyzed display short arcs or a high initial statement answered at a lower level. Range: Wide, varying from one octave to two octaves. Intervals: Unisons: (32.5%) Minor 2nds: (1%) Major 2nds: (35.5%) Minor 3rds: (11.5%) Major 3rds: (1%) Perfect 4ths: (11.5%) Perfect 5ths: (6%) Octaves: (1%) Mode: Pentatonic dominates. The examples analyzed are highly ornamented implying an acculturative influence. Timbre: Young people in solo and duet combinations. Texture: Analyzed examples include a two-part selection and solo male voice with soft singing in the background. The love songs are accompanied with a can “drum.” Intensity: Free and full with an open, unstrained quality. |

|

Harmony: |

Some harmony can be found among the love songs. Duets occur as one singer sings a phrase and the second singer will echo the phrase or provide an original phrase beginning before the other is finished. The temporary layering or overlap creates a horizontal harmony of various intervals. |

|

Rhythm: |

Love songs are highly rhythmic with a duple feeling dominating. |

|

Form: |

Love songs are relatively short and contain considerable repetition. The call and response pattern are evident. |

|

Instruments: |

In the improvised nature of the small singing occasions among friends, it is easier and more appropriate to do with a makeshift instrument rather than get permission to use the village drums. Therefore, a drum substitute is found. A can “drum” (a one-gallon gasoline can) or a larger metal container for a larger occasion will work as a resonating chamber for accompanying dance and singing. On other occasions, a gourd beaten rhythmically will provide a good body of sound for accompaniment. Flute, bottles beaten on the ground, or the thom (thumb piano or mbira) provide an effective accompaniment. |

3. Marching Songs (Nirnam)

The marching song (Nirnam) is much like a love song in that it is used in an age set stratified activity. A Nirnam is composed by the young in a village when they agree on refusing something, often salt or beer, or some other item of food until they kill a certain animal. “The men prepare themselves and the girls prepare for the successful hunt by preparing beer for that day when the animal is killed. After the animal is killed, a song will be formed according to the action. Everyone will be glad; they will return to eating the thing they had sworn not to eat and the song will tell of the exploit.”[2]

3.1. Marching Song (20A 6 097) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 20A 6 097 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 20, 1972 Date of Transcript: September 27, 1972 Source of Song: Probably Ajwara Performer: Woman soloist singing for recording purposes. Informant: Paul Abulla and Henry Akway |

|

Description: |

Marching songs, or Nirnam, may be characterized as songs of boasting. They are for a certain age set and are composed for the occasion when some large animal is to be killed. The members of the age set take an oath not to participate in some activity or to refrain from some food or drink until the animal has been killed. |

|

The Text: |

We have shot holes in the beer strainer because of the boasters. We are good shooters. You take your 3003 rifle and fight. The generation of Dhogo is boasting to fight. Let us go back and drink. You beat our drum very well. He who goes back and drinks is spoiling his name. (He would spoil or discredit his name because the age set of Dhogo swore not to drink beer until they had killed the elephant.) A word-for-word linear translation follows: Adhinga [The strainer] agocwa [shot] mac [bullet] kipper [because] gwocwa [are boasting] kongo [beer] No [When] dwue [come] ki [from] bang ngu dhogo [liar Dhogo] ocwoli [be called] nidi [how] Thor [Shooting aim] mo [that] enayi [he has] Kwaylwak [Man responsible for a certain generation]. Ojulo [Title of the] nikango [man] congo [the day] ojolwa [we shall respond] go [it] dhogo [person’s title] cwol [called] ni [is] dejashmach [Dejashmach]. Kwanya [Take] (Pick up) abucare [3003] ki [with] nyare [daughter] no [that] kwot [Kwot] (name of a person) Bang [Nobody] ngat [person] jiemo [argue who is best] ki [with] uni [you] podha [proceeded] lwa [the generation] dhodo [title of man] liec Lwa [The generation] liec [title of man] jo [people] ngwya [boast] karleng [place of fight] jo [people] dokedo [would have fought]. Joby [Title] winy, wala [buffalo] nyino [the man] obwoth [lead] abongo [type of dance] jo [people] ngwoya [boast] gin [something] rac [bad]. Dejachmach [Dejachmach] wana [we] duo [returned] bang [from] ngu [lion] wa [we] bwoth [lead] thabur [marching]. Iwa [Title] caam [of the girls] nyogira [called] nyi [girls] kwaa-ya [leaders] arage [robes] kargi [all] bet [them]. Nyi [The person] ko [said] ni [that] wa [we] do [return] ri [back to] math [drink] bulli [title] winy-caam [of a person] goc [beat] Burwa [drum] (our drum) niber [good] ne [so] winye [heard] ngat [person] kale [brought] kongo [beer] ranya [spoil] Nyinga [name] Gok [Gok] (village name) |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: Descending patterns from the initial high point. Range: Two octaves. Intervals: Unisons: 27 (40%) Major 2nds: 17 (25%) Minor 3rds: 9 (13%) Perfect 4ths: 8 (12%) Perfect 5ths: 5 ((7%) Major 9ths: 2 (3%) Scale: See transcription. Mode: Pentatonic (anhemitonic, first mode) Tonality: A Timbre: Female singer. Texture: Monophonic. Solo without accompaniment. In a usual situation this would be sung as a call and response. Intensity: Moderate. |

|

Rhythm: |

Duple meter. Built on eighth notes grouped in pairs, sometimes subdivided. |

|

Form: |

Call and response, though not identified in this example. Two nearly identical phrases. |

|

|

|

3.2. Marching Song (20A 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 20A 1 000 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 20, 1972 Date of Transcript: September 27, 1972 Source of Song: Gok Performer: Woman soloist from Gok singing for recording purposes. Informants: Paul Abulla and Henry Akway |

|

Description: |

This characteristic marching song boasts of the killing of a leopard and an elephant. |

|

The Text: |

All of you; all of you; you young boys, put on your shoes. You are the second. You young girls, put on your shoes. You are the first. (The young boys have killed a leopard.) I want to perform a very nice song of marching that could be heard all over the villages. This is the generation of the man (in charge of them) Ogira. We are the top men. (Praises the age set) We don’t have an old man in our village. But our village is always being aggressed. We have killed a lion and a male elephant. Our village has gone back to its former normalcy. In the time of marching, the trumpets and the drums sound. We march on, the generation of Ogira. (Praising themselves) We refused to eat a certain kind of fish. But we will be eating the skin of an elephant. The young boys have come after killing the elephant. The people have received them with cheers. Repeats. |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: A generally descending contour from the beginning of each short phrase. Range: Minor tenth: C-Eb Intervals: Unisons: 17 (20%) Minor 2nds: 2 (2%) Major 2nds: 25 (30%) Major 3rds: 2 (2%) Minor 3rds: 13 (16%) Perfect 4ths: 11 (13%) Perfect 5ths: 5 (6%) Octaves: 8 (10%) Scale: See transcription. Mode: Mixolydian, First mode. Tonality: F Timbre: Female singer. Texture: Monophonic. Solo without accompaniment. In a village situation, this would be sung in a call and response pattern. Intensity: Moderate. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

Various combinations of duple and triple which produce at times a feeling of compound meters 5/8 and 7/8. |

|

Form: |

Call and response, though not identified in this example. Two almost identical phrases followed by a third phrase with new material. |

|

Instruments: |

None present. |

|

|

|

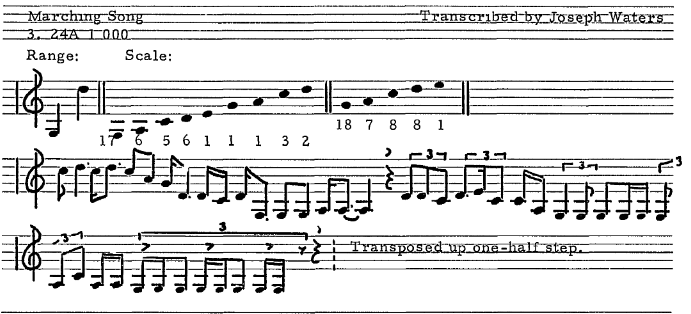

3.3. Marching Song (24A 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 24A 1 000 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 22, 1972 Date of Transcript: September 30, 1972 Source of Song: Okuna Performer: Woman soloist, Omot from Gok singing for recording purposes. Informants: Paul Abulla and Henry Akway |

|

Description: |

About thirty people surround the recording area as Omot sings about the killing of an elephant. |

|

The Text: |

All the generation, we are to visit the country of Haile Selassie. People are talking of the chief, Nyigwo. But we are going to resume and establish again the dynasty of the chief as it was from the first chief, Okedi. People of the village ask, “Where are the young boys?” They have gone to the elephant. The young boys want to go to the North where the Masengos would run and the leaves shall fall down. (The Masengos wear leaves. Therefore, the boys would destroy them. They would run and the leaves will fall down.) (Praising a girl) She is a gentle girl. We were asked, where did you come from? We came from the fence. (Or from inside the fence of the chief) We are the people who refused olwietha (made to replace salt.) We will never eat it again. (Insulting it: Like the urine of a donkey.) We refuse it and our village has been heard all over the Anuak villages. Repeats. (The Anuaks would have destroyed the Masenko tribe, but because of the law, they did not.) |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: A complexly rhythmic melody starting high and immediately descending to a low tessitura. Range: Octave and a fifth: G-D. Intervals: Unisons: 20 (49%) Major 2nds: 13 (32%) Minor 3rds: 4 (8%) Major 3rds: 1 (2%) Perfect 4ths: 2 (5%) Perfect 5ths: 1 (2%) Scale: See transcription. Mode: Tonal penta scale. Tonality: Gb Timbre: Female singer. Texture: Monophonic. Solo without accompaniment. In a village situation this would be sung as a call and response. Intensity: Moderate. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

Complex. An incomplete quarter note triplet is described containing only 2 ½ of the usual 3 quarter notes. The last beat is cut off; it functions both as the last beat in the quarter note triplet and also as the first beat in the following eighth note triplet. (Waters) |

|

Form: |

Call and response, though not identified in this example. This representative portion is a part of a selection of five sections. It is a theme with three variations plus a recapitulation of the theme. All sections have the same range and general shape. They begin on the same dominant and progress downward to conclude on the same tonic a perfect twelfth below. Each contain a series of repeated notes on the bottom tonic. (Waters) |

|

Instruments: |

None present. |

|

|

|

3.4. Marching Song (29A 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 29A 1 000 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 26, 1972 Date of Transcript: February 19, 1973 Source of Song: Gok Performer: Athur Abulla, female about 28 from Gok, singing unaccompanied for recording purposes. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

The young generation in Gok swore not to drink beer until they had killed an elephant. This song was sung to commemorate that event. On this particular occasion, they shot the male elephant, and the female elephant tried to chase them away. This is mentioned in the song. |

|

The Text: |

Though the female tried to chase us away, we killed both and took the child of the elephants. (The Gok people were the first in the Anuak area to catch such a small elephant. When they tried to bring this elephant to Gambela, unfortunately it died on the way.) This year will be a happy year. The young generation of Ethiopia will be playing. Our Quilwak will stand in front of an airplane and will be photographed. (Quilwak was the leader of the generation, Kwaclwak.) |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: The highest point is achieved at the beginning and descends gradually. Range: Octave and a perfect fifth: F-C Intervals: Unisons: 14 (29%) Minor 2nds: 2 (4%) Major 2nds: 13 (27%) Minor 3rds: 7 (15%) Major 3rds: 5 (10%) Perfect 4ths: 7 (15%) Mode: Pentatonic Tonality: F Timbre: Solo female singer. Texture: Monophonic. Solo without accompaniment. In a village situation, this would be sung as a call and response pattern. Intensity: Moderate. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

Complex, free. |

|

Form: |

Nonrepetitive consisting of a number of phrase groups similar to the one transcribed. Call and response, though not identified in this example. |

|

Instruments: |

None present. |

|

|

|

3.5. Marching Song (31A 4 235) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 31A 4 235 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 27, 1972 Date of Transcript: March 10, 1973 Source of Song: Ajwara Performer: Yalo Alwinye from Ajwara, a man with a clear high voice singing unaccompanied for recording purposes. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This song refers to the killing of an elephant in 1963, approximately. |

|

The Text: |

Swear not to smoke tobacco. (athumanua) When we swear not to smoke the Anuak smoke, we went to Juba and we came back with hand bags. When we see many fellows having hand bags, we see that our village will never again be destroyed. All the people of the villages saw us. Our marching and girl’s marching will be heard in the whole area of Anuak, and we will go to Juba with our girls together. |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: The highest point occurs at the beginning of the piece and descends. Range: Two octaves: A-A. Intervals: Unisons: 56 (52%) Major 2nds: 28 (26%) Minor 3rds: 8 (7%) Major 3rds: 1 (1%) Perfect 4ths: 10 (9%) Perfect 5ths: 4 (3%) Octaves: 1 (1%) Scale: See transcription. Mode: Minor. Tonality: D Timbre: Male singer with a clear, high voice. Texture: Monophonic. Solo without accompaniment. In a usual situation this would be sung as a call and response pattern. Intensity: Moderate. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

Free. No strong feeling for pulse. |

|

Form: |

The introductory phrase is repeated and followed by a number of variations. Call and response, though not identified in this example. |

|

Instruments: |

None present. |

|

|

|

3.6. Marching Song (32A 10 383) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 32A 10 383 Place of Recording: Peno Date of Recording: July 28, 1972 Date of Transcript: March 17, 1973 Source of Song: Peno Performers: Okelo, a young man of about 18 singing at first without accompaniment and then with added gourd and bottles. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

As the singer performs for this recording, he sits before the microphone with another man playing the gourd as a drum and a third man playing the bottles by alternately pounding them on the ground causing two different pitches to sound. He sings at first without accompaniment and then the instruments are added, changing the rhythm of the song. When the rhythm is changed, the marching song becomes a dancing song. |

|

The Text: |

(When they swore to kill an elephant, they said): If we miss to kill an elephant, we will kill a young Nuer fellow. If I’m really angry (or upset), I will go to attack a certain village of Nuers. (Ten to fifteen years ago, the Anuaks were fighting village against village. If one village and another were in disagreement, the people who swore would say, “If we don’t kill the animal, we will go and attack that village.”) If we capture a small elephant, we will adopt it to help it grow. The ivory can be cut and divided among this our generation. |

|

Instruments: |

A gourd used as a drum and two bottles. |

3.7. Marching Song (33B 4 189) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 33B 4 189 Place of Recording: Peno Date of Recording: July 28, 1972 Date of Transcript: March 24, 1973 Source of Song: The village of Okade; written by Nyinyoni in 1963. Performer: Nyinyoni, composer and well-known singer. Sung at first without accompaniment and then with added gourd and two bottles. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

The setting for this recording is much the same as that for Number 6, 32A 10 383. |

|

The Text: |

(In our area, there are young fellows who want to cause fights between villages. The old men will send them out saying, “If you don’t know war, you better go and fight an elephant in the forest.” The old men used to say that to young boys who didn’t know war at all.) When we kill an elephant, everybody in the village will buy a gun. If you don’t know war, then you better go fight an elephant. If there is a war now in the village, I know now that you are going to fight. Repeats. We didn’t fight an elephant because of the meat but because of the ivory. (Instruments: gourd and bottles are added.) When we fought elephant, we captured a small one. Repeats: “Captured a small elephant daughter.” You refused the old men so that the young boy that is going to marry you will give you the ivory of an elephant that we kill. (The accompaniment slows down. The drumming changes, but the song is the same one. When the boys came from hunting, the girls went to them singing this song in the slow form.) We are glad you are coming. (The accompaniment speeds up again. When the girls reached the boys, the drums were beaten in a dancing form and the boys and girls danced together. This is why the music speeded up again.) |

|

Instruments: |

A gourd is used as a drum along with two bottles beaten rhythmically on the ground. |

3.8. Marching Song (37A 12 323) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 37A 12 323 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: August 3, 1972 Date of Transcript: September 9, 1972 Source of Song: Oboa, composed by Omot Opiew, about 1961 Performer: Omot Opiew, male; sung without accompaniment. Informants: Cham Moses, Obong Odiel, Omot Ochan, and Henry Akway |

|

Description: |

Omot Opiew sings for the recoding. He states that since he is a composer, it is very easy for him to learn other songs. Therefore, he knows many. The old composers in his village died, so he took over.[3] |

|

The Text: |

(These people have refused fish having scales.) I’m greeting all of you. You are the generation of a man called Lion. (The man having this title is the head of that group.) Let’s talk of this and have one decision. Whatever we have talked about strongly (or promised to do) shall not be left. (Shall not be ignored.) They found what they had been looking for. The sound of bullets shall be heard at Dhirmac (a village) People have asked us, what have you killed? (He replied) There is no particular thing. Whatever we will find, we shall kill it and we won’t tell the number of what we have killed. This generation shall be counted among the top (the strongest). (Then they were asked): Where are you going? We shall be marching with our shoes. We have refused this fish, and we shall never eat it. Even though four or five people among us try to kill something, it is still we, the generation who has killed it. We are the first and the strongest. We have a decision that is hidden. (Which means, they will never expose the decision until it has been told to the chief.) There are two groups. The first group will be leading. (Called Awero, a kind of bird, like a duck, black and with numerous white spots, some blue on the head and no hair on the sides of the head.) The second group shall follow the first group (called Gweno, chicken). The groups shall cross the river through the village of Abol. |

3.9. Marching Song (B 4A 9 247) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: B 4A 9 247 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: January 8, 1973 Date of Transcript: April 27, 1973 Source of Song: Ocwing, about 1958 Performers: Okwot Buy, male, from Okade, joined by the group around him. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

Okwot sings this song of boasting for the recording. |

|

The Text: |

(The Anuaks are using buffalo skin to make shoes. This kind of shoe is very hard to beat someone with.) We are the generation who ignore the beating of this kind of shoes who fought the people of Maji and the people in Bale province. The dancing that we are going to dance will be heard in the whole region of Anuak. We are the generation of the man who is named after a giraffe. Raise your hand with an ivory. We are who people are looking at. (The song praises the leader of their generation who is likened to a man who makes commands and leads during a war.) |

3.10. Marching Song (B 6A 2 149) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: B 6A 2 149 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: January 12, 1973 Date of Transcript: May 5, 1973 Source of Song: Ajwara. Composed by Otok in about 1956. Performers: Kwot Onyinyi with five other men. All men are about 30-45 and sing without accompaniment for the recording. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This marching song is unclear as to what the people swore not to eat. However, they wanted to kill a lion and their age set leader is named after a buffalo. |

|

The Text: |

When we boast for a lion, we didn’t come back and people thought that our generation would be finished by a lion. Those who say that our generation would be finished, when we fought it, we shot the lion and it fell down on its right shoulder. When we march, we will have a flag leading and the bullets will be shooting after the flag. You told the people to keep silent. But they said, we are the generation of the people who disobeyed the order to keep quiet. When people ask where are those who killed the lion, we will be in the line under the flag. The trumpet will be blown and we will march. Those who kill a lion are the best men. Amharas came from hunting in the forest. (They named themselves as Amhara, a term of respect.) We have killed what we said we would kill. |

3.11. Summary of Marching Songs (Nirnam) |

|

|

The Text: |

Because marching songs relate the exploits of a group of young people in their success against some animal, they provide an opportunity for a particular age set to boast of their strength and achieve status and prestige. They boast that they are the top men, that they have been received with cheers. They have displayed their bravery by the killing of a large animal and this deed is for the entire village to see. In some ways, this activity and the recording of the activity has the connotation of establishing manhood. It is important to follow through on the promises for the sake of the status and honor of the age set. The texts describe the mode of fighting as well as the object of the battle. Plans are described: they will be led into battle with a flag; they will go in with bullets flying; they will split up and then attack. Fighting an animal provides a surrogate war and in effect heightens the young’s desire for violence as well as providing an outlet. The texts describe a form of ritual that the young people take seriously. They swear not to participate in something until their goal is achieved. They may not drink beer, or eat fish, or salt, or smoke tobacco until they have accomplished their goal. |

|

Melodic Analysis: |

Shape: There is a pattern of the highest point of the melody being achieved at the beginning of the song or at the beginning of the phrase and then descending to a lower tessitura. Range: Wide. Ranges of the songs vary from a minor tenth to two octaves. Intervals: Unisons: (38%) Minor 2nds: (1%) Major 2nds: (28%) Minor 3rds: (12%) Major 3rds: (3%) Perfect 4ths: (11%) Perfect 5ths: (4%) Octaves: (2%) Major 9ths: (1%) Mode: A variety of tonal patterns are present including pentatonic, mixolydian, and tonal pentatonic modes. Timbre: All recorded examples that have been transcribed were with soloists singing for the occasion. Texture: Monophonic. Intensity: Moderate. |

|

Harmony: |

None present. |

|

Rhythm: |

Ranging from complex and free with no feeling of pulse to a duple feeling. With the addition of some rhythmic pulse, it is probable that the songs would display a duple feeling. |

|

Form: |

Varies from nonrepetitive to theme and variations, to identical phrases. In a normal village situation, a call and response pattern of singing would be followed. |

|

Instruments: |

None used in transcribed examples. Drums or gourds are used. |

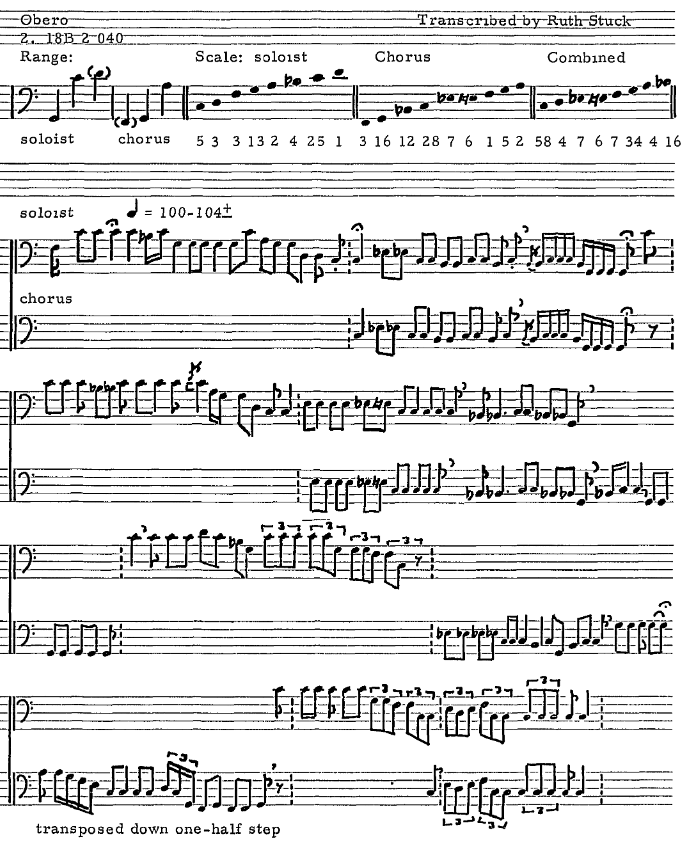

4. Dancing Songs (Dudbul)

The dudbul or dancing song accompanies a major portion of the dance activity of the Anuak. There is a variety of dancing patterns and accompanying drum beats such as the okama, abongo, alenga, and koro which can be characterized by their drum beat patterns and accompanying actions. Since these are more connected with the dance and have limited verbal-musical content, they are mentioned only in passing. The dudbul has a large body of music prepared for it and some comments are appropriate.

The age set is important in this type of dancing. The activity is largely confined to members of the same set of both sexes. Word content for Dudbuls is similar to Oberos and Nirnams, in that the chief is begged for certain needs of the singer. In addition, many other individuals in the village are mentioned in the songs. “When the dudbul is sung during the dancing, there are some people when they are mentioned in the song immediately will give a price, a spear, five or ten dollars. Because of that, the people who dance will repeat that part many times to make the person dance…the one that gave something.”[4]

4.1. Dancing Song (10B 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 10B 1 000 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 12, 1972 Date of Transcript: August 1, 1972 Performer: Young female soloist, Onyicli singing for the recording. Informant: Paul Abulla |

|

Description: |

A dancing song would normally be performed during a village dance and would involve an age set and members of the opposite sex. Drums would be used and a call and response pattern incorporated. This performance is by a single singer for the benefit of the investigator. |

|

The Text: |

I never thought of getting something, but I did. What was given by the chief (or the king), I will not deny that I was not given. (To a certain lady) Don’t be surprised. This liar is trying to confuse us and bring misunderstanding between us. Anyone who stays with the chief may get something. (Mentions the names of the people.) (Asking the people whose names are in the song to give something to the singer. Sometimes, when people find that their names are in the song, they will give something to the composer. Not only the chief gives, but those whose names are in the song will give something to the fellow who wrote the song.) (Informant Abulla) (She asks the chumi (chief or king) not for herself, but to give something to the people.) |

4.2. Dancing Song (11B 4 124) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 11B 4 124 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: July 12, 1972 Date of Transcript: August 2, 1972 Source of Song: Openo Performer: Ocan Obang, male singer, about 20, singing without accompaniment for recording purposes. Informant: Paul Abulla |

|

Description: |

This song belongs to the Jo Burra, the bodyguard. |

|

The Text: |

Mentions the names of those in the bodyguard.) Some people used to go to the chief, saying, “Don’t give this boy demoui or cow. He is not a good man.” (Continues to mention the names of the people.) |

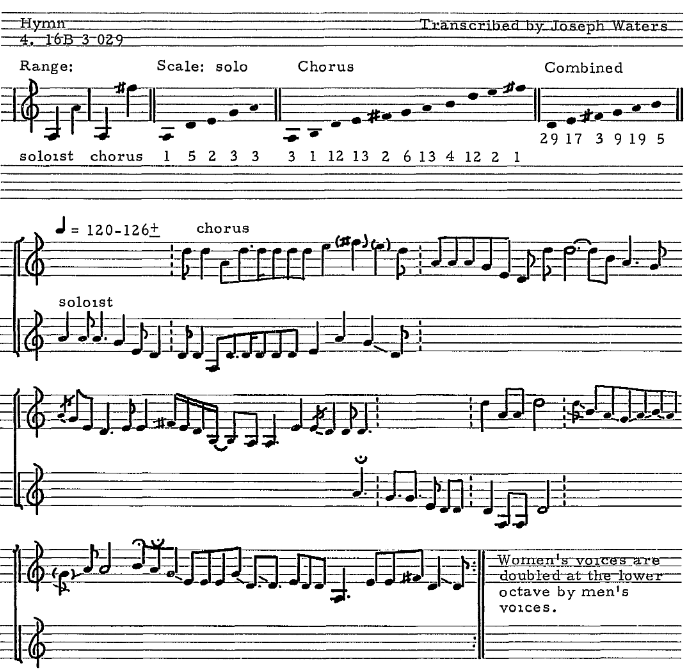

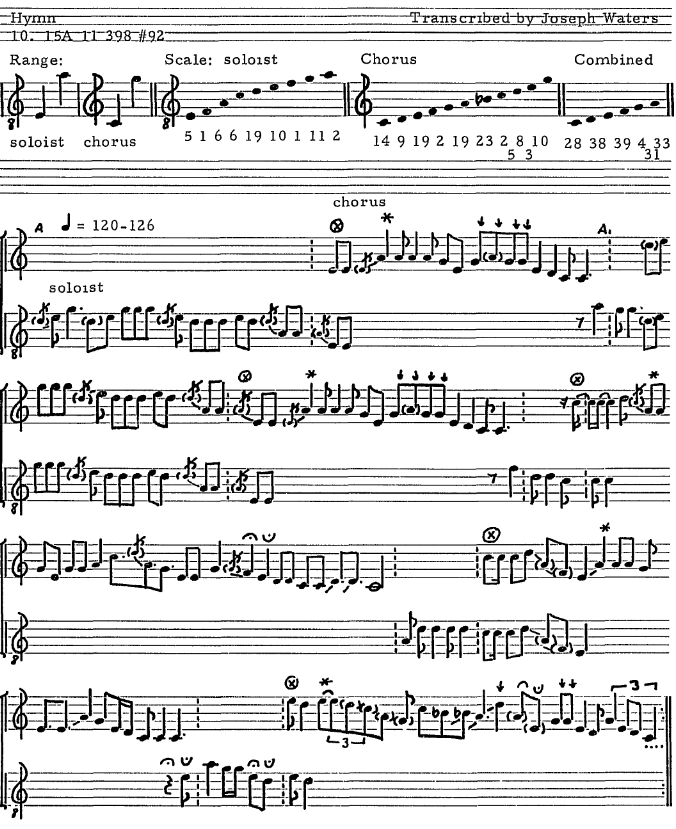

4.3. Dancing Song (18A 1 000) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 18A 1 000 Place of Recording: Anyele Date of Recording: July 17, 1972 Date of Transcript: September 5, 1972 Source of Song: Probably Anyele Performers: People of the Village Informant: Omot Ochan |

|

Description: |

Field Notes of July 17, 1972 yield this description of the village of Anyele and the recording success encountered. “Anyele is on the right side of the Baro River, downstream from Illea. The setting is dominated by three large trees casting a shade over the dancing area and (learned later) suspected as being spirit trees, worshipped by and possibly dominating the thinking of the community. The people are not well-prepared as they were not aware of our coming. Yet they seem poorly disciplined and surly. The children sing with long delays between each song. They react to a degree and yet not with the pride evident in other places. The children sing loudly and inaccurately. The village then decides to sing, led by someone who is not the usual leader, and they do not sing well. There is much inattention and talking while singing is going on. Perhaps with the normal leader, they would do better. The first question asked of us was for some form of pay if they would sing. They showed no respect to Paul, but later showed considerable alarm when they realized who he was.” |

|

The Text: |

(Praising the people in the group.) (When performed, they praise you or praise his friend and the girl friends and the group. The dancing arrangement would be with the girls in the center of the circle surrounded by the boys.) |

4.4. Dancing Song (19B 11 285) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 19B 11 285 Place of Recording: Pokwo Date of Recording: July 20, 1972 Date of Transcript: September 25, 1972 Source of Song: Gok Performer: Gilo Akway, solo female singer who has leprosy. Informant: Paul Abulla and Henry Akway |

|

Description: |

This recording session took place in the village of Pokwo. Thirty or forty children stood around or sat and watched the procedure. They particularly enjoyed the play-back of each tape after it had been recorded. The leprosy patient from Gok sings with confidence and with a clear, strong voice. This recording session was at the request of the investigator. |

|

The Text: |

(Praising the people) I didn’t expect that I would come out without getting anything. I don’t know whether I will get something or not. (Praising two people, saying): I expect something. The king has become better now. He has some trade but my poverty will just throw me to a foreign land. (Praising a girl, saying): You won’t be taken by that rich man forever. You will be back with us. She’s a good girl. She has refused to be taken by the rich man and the rich man now is troubled of what to do. You insult him and give him back his properties. (Praising the girls about their beauty.) (Mentions a certain girl) When people talk, she will be taken to a rich man. They will simply reply. “Oh, our beautiful girl.” I don’t expect coming out without getting anything. (Praising some girls) She has become like a daughter. For me, I have enough, but I’m still looking for the next girl. (Praising the girls, saying): Our wife has disappeared. Something that you have looked for (meaning a girl), If it is taken by somebody, why don’t you die without feeling anything. A bullet will strike you unknowingly, without feeling. (Praising the girls) Whatever people have been talking about, I have never forgotten it. (That girl may have been the first one promised him.) We have not cultivated very well this year because we were not determined due to the trouble of the girl that has just been picked without our notice. (Praising the generation) I’m the poorest. Nobody is like me. (Praising the people) He would be called by that bead. (The ones from the girl’s lower lip, hanging to the floor.) (Praising the girls with their titles.) (Praising a certain girl) Try to stop my poorness. (Praising the people) I wish that demoui would become something very easy to be found. (Mentioning the name of a certain girl) I compare you with a certain beautiful thing. She works hard. (Praising the people, saying): Who will blame you. (Praising a girl) She is beautiful. |

4.5. Dancing Song (26A 8) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 26A 8 Place of Recording: Illea Date of Recording: July 24, 1972 Date of Transcript: January 20, 1973 Source of Song: Illea Performers: Soloist Odiel, male, with villagers and trumpet player Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

This song is essentially a love song for the chief. It is in the dudbul, or dancing song category. The field report of July 24, 1972 provides a description of the village scene. “12:00 noon. Action begins with the women and children sitting to our left, the soloist in the center in front of the drums. The men are to the right and what dancing is done takes place in the far center, out of the shade of the trees. The leader is strong, expert and responsible for the composition of many of the songs sung. He is the composer for several of the villages in the area, making his living as a composer of songs for several of these places.” |

|

The Text: |

God, what can I do…what can I do? I swear in the name of our chief, God, what can I do? I swear in the name of our chief. When I feel my fullness, I will be calling your name. What problem have you seen that I have done? It seems to me that I’m the best friend in the village. (Praising his friend and his wife also.) (The singer mixes different languages including the sounds of the Somali.) You are the leader of the village. No one will overthrow you. (Trumpet sound included) (He is singing in a different language and then back to Anuak at which time the villagers respond.) You re the leader of the village. No one will overthrow you. |

4.6. Dancing Song (32A 4 076) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: 32A 4 076 Place of Recording: Peno Date of Recording: July 28, 1972 Date of Transcript: March 17, 1973 Source of Song: Composed by Nyinyoni Ajwiar from Owelo while he was in Gambela. Performer: Nyinyoni accompanied by gourd and two bottles. Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

Recording this composition was a part of a very pleasant session in Peno about one hour down river from Pokwo. The soloist was a strong singer, self-assured and respected. Field Notes for July 28, 1972 describe the scene: “Taping session begins at 11:15 with Nyinyoni seated in front of us. The chief is seated on a raised section under a tree, the men of the Burra watching in a circle, the younger boys at a distance under the shelter of a house roof, close enough to do whatever the Jo Burra requests. The women and children are seated at a distance by the houses. Nyinyoni is a song composer of great repute and a person who has traveled around to a great extent within the tribe. His songs have been composed in a variety of places and at a variety of times. “Nyinyoni wants to find a drum or a tin for rhythm, but he has difficulty. Soon a man with a gourd and a man with two bottles, a beer bottle and a whiskey (mineral water?) bottle arrive and form the accompaniment. The gourd is played as a drum and the bottles are played alternately pounding them on the ground, causing two different pitches to sound. The placing of a finger over and then off the top of the larger bottle also causes a pitch change.” The song includes a good deal of explaining. |

|

The Text: |

(There is a girl who was married by one of the freedom fighters and the girl came to Gambela to buy clothes. When she came, she fell in love with one boy in Gambela, a man called Paul. The freedom fighter sent a message from the headquarters to Gambela to let the girl go back. He said, “How can you fall in love with a boy in Gambela, those who are roaming in a town with no place to sleep and nothing to be eaten?” There was a rich man who produced a song against the poor. This man, Nyinyoni the singer, replied the song to him, answering the song sung against the poor.) You refuse that boy. Don’t marry him. Repeats You beat the drum that can be heard in Kudbudi (Gilo River area). (There was a boy who was wanting to marry a girl. When they agreed to marry each other, before it was heard by the people, he went to the gold mine. Those who are living in Tiernam used to marry a girl who is married already and they married the boy’s wife while he was in the gold mine. The boy who was in Torit (the location of the gold mine) asked a question about the girl.) (He said) How were you married by that man? (The girl answered): Because you stayed for a long time in the gold mine. (When the boy came back from the gold mine, the girl was in need of him again. She admired him and said he looked like one of the captains of the Anya Nyas.) There is no possible way to get money by working at the gold mine. Repeats last part. Our wife came back from Gambela. We will still want her and take her again. A rich man is a person who eats alone who wants to share nothing. |

4.7. Dancing Song (B 1B 7 1050) |

|

|

Recording Information: |

Tape Number: B 1B 7 1050 Place of Recording: Tierlul Date of Recording: January 5, 1973 Date of Transcript: April 23, 1973 Source of Song: Composed by Odiel Okelo from Ebago. The song is from Illea, composed in 1972. Performer: Odiel, singing without accompaniment Informant: Agwa Alemo |

|

Description: |

An extended amount of time was spent with Odiel Okelo during this recording session as he sang for the investigator. Odiel’s work was observed several times during the time we spent in the area. He sings with his hands over his ears, sitting forward, and looking through eyes that appear not to be well. |

|

The Text: |