3 The Electrical Age

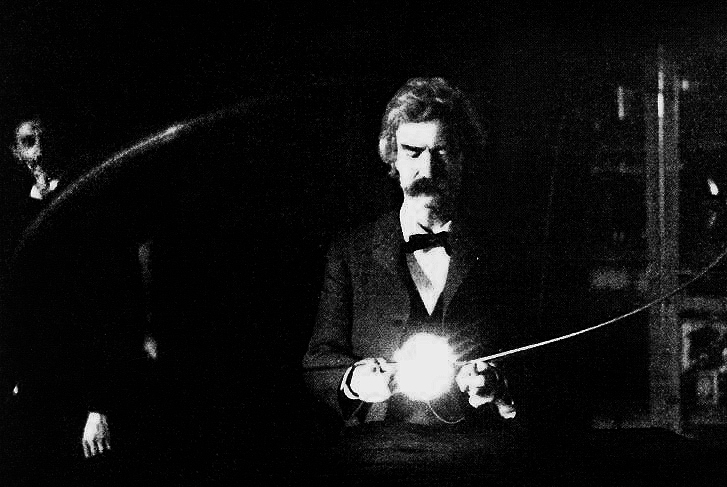

The Electrical Age could be said to have begun with Michael Faraday (1791-1867), the friend of Ada Byron whose discoveries helped pave the way for the electric motor. Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) developed alternating current and invented the induction motor in 1887 and 1888, then engaged in a famous “war of the currents” with Thomas Edison, who had bet on direct current. Tesla won that war when he partnered with George Westinghouse in 1893 to generate power at Niagara Falls and to light the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Tesla was awarded 278 patents in 26 countries, and experimented with wireless power transmission, X-rays, robotics, and lasers. Edison accumulated 1,093 US patents for devices like the phonograph, the incandescent light bulb, improvements to the telegraph, batteries, and the carbon microphone used in telephones.

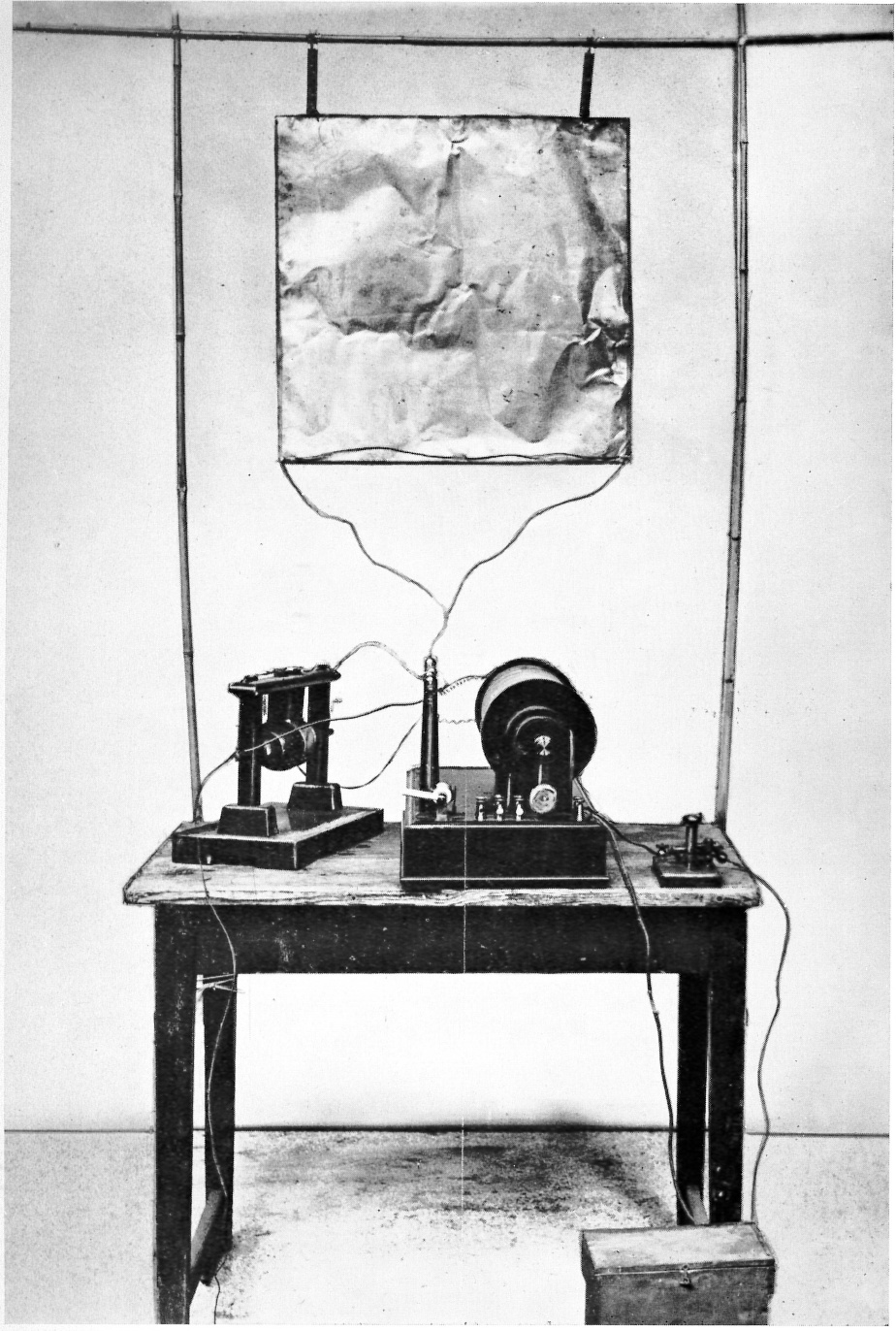

Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937) was an Italian electrical engineer and winner of the 1909 Nobel Prize in physics. At the age of twenty he designed a radio-telegraph machine, which he demonstrated in England over the next couple of years. By the end of the 1890s, he was sending wireless morse code signals to ships at sea, and at the beginning of the twentieth century Marconi sent and received radio transmissions across the Atlantic.

John Logie Baird (1888-1946) was a Scottish engineer who in 1928 achieved the first transatlantic television transmission. In the same year Baird also demonstrated color TV and stereoscopic 3D TV. Philo Farnsworth (1906-1971) was an American best known for inventing the first all-electronic image pickup device for video cameras in 1927.

Robert H. Goddard (1882-1945) was an American physicist who is credited with inventing the liquid-fueled rocket in 1914. Goddard first successfully launched a rocket in 1926, and over the next fifteen years he launched 34 rockets, reaching altitudes of 1.6 miles and speeds of over 500 mph. Americans took little notice of Goddard’s work, although Charles Lindbergh was impressed. In 1923 Goddard warned that the Germans were pursuing rocketry, but serious American engineers were not interested.

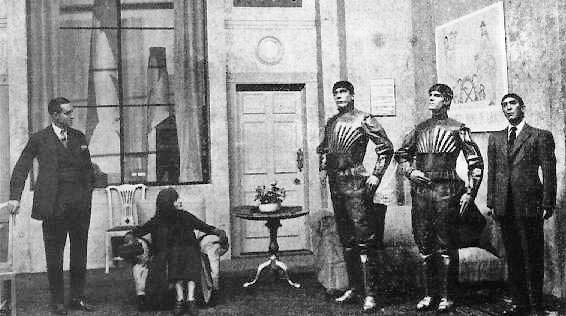

Karel Capek (1890-1938) was a Czech writer of what we now recognize as early science fiction. Capek coined the term robot in a 1920 play called R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) about a dystopian factory whose workers were sentient androids. Robota means serf labor in Czech. Capek’s stories discussed the ethical problems of mass production, dictatorship, nuclear weapons (yet to be produced), and the greed and power of corporations.

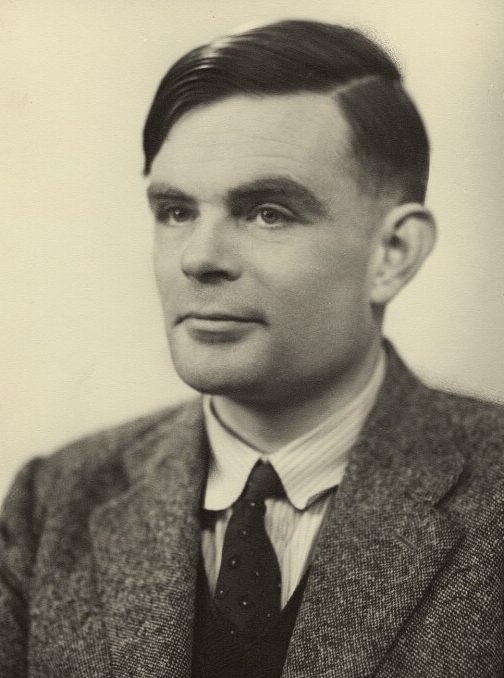

Alan Turing (1912-54) was an English mathematician and early computer scientist. He worked with British code-breakers at Bletchley Park and devised an electromechanical machine that could decipher the settings of the German Enigma machine.

Turing invented the Turing Machine in 1936 as a mathematical model of computation. It is an abstract concept rather than a physical assembly of parts, so Turing’s work in a sense follows in the tradition of Ada Byron. In the conceptual model, the “a-machine” (automatic machine) manipulates a potentially infinite-length “memory tape” divided into discrete cells. The machine scans a cell and reads the symbol located there that stands for the desired function. The machine follows the instruction, writes its output in the cell, and moves to the next cell.

One of the first things Turing discovered about this model of computing is that it does not provide a solution to the Entscheidungsproblem or “decision problem” of logic first outlined by German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz in the 17th century and later elaborated by David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann in 1928 and Kurt Gödel in 1933. The gist of the problem is completeness: can an algorithm be created that could decide whether a given statement is provable using the rules of formal logic. Turing and Alonzo Church concluded in 1936 that the answer was no. This led to the Turing-Church thesis on the nature of computable functions, and ultimately to Turing’s definition of the “Universal Turing Machine”. The UTM is a Turing machine that can simulate the operations of any other Turing machine and run them as programs. John von Neumann used Turing’s idea to develop his concept of the stored-program computer in 1946, now known as von Neumann architecture.

John von Neumann (1903-57) was a Hungarian-American mathematician and physicist. After a youth distinguished by several recognitions of his genius, von Neumann was offered a lifetime professorship at the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton. He worked on the Manhattan Project during WWII, and is credited with developing the concept of mutual assured destruction (MAD) during the Cold War.

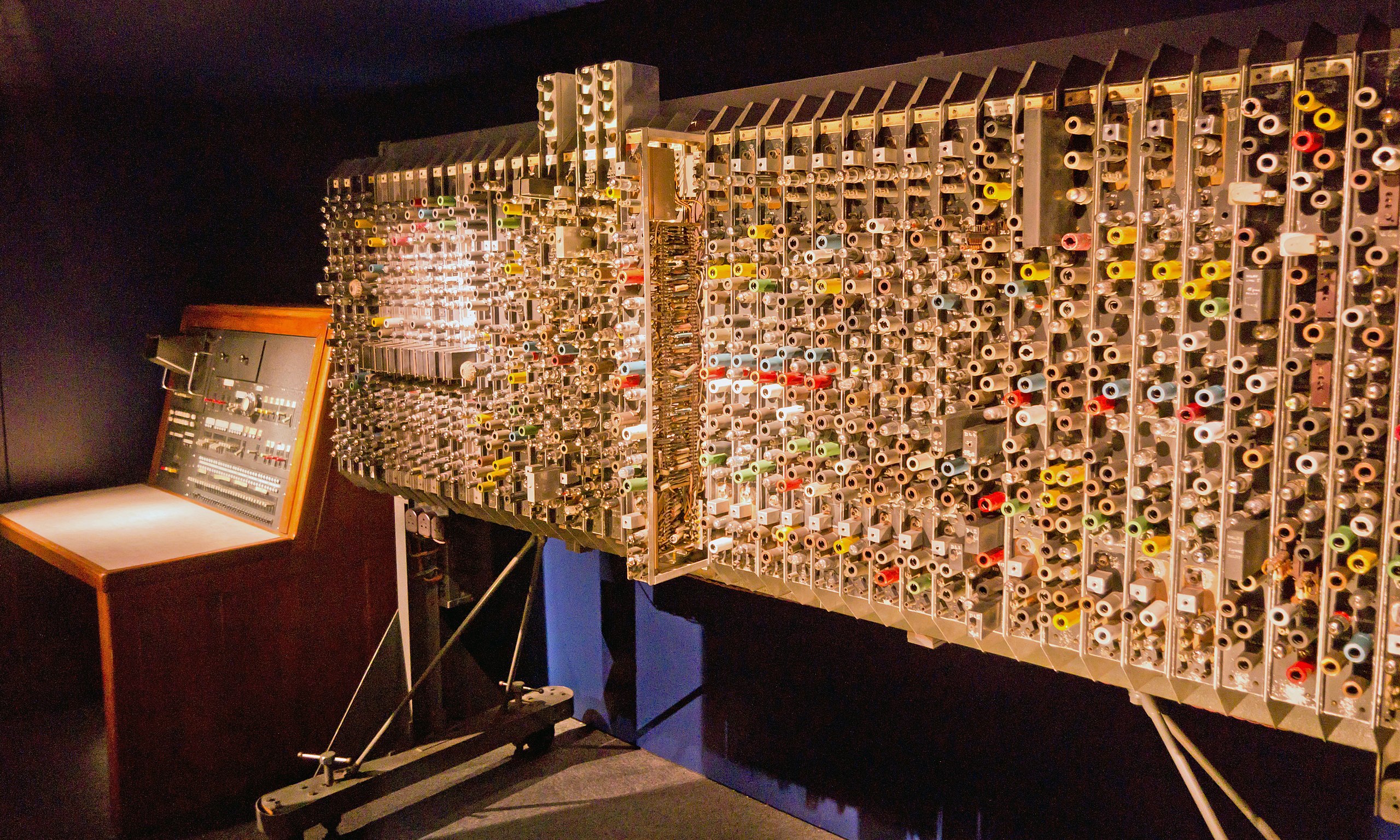

The architecture specifies an input device connected to a central processing unit that contains a process controller and an arithmetic/logic unit connected to a memory unit that stores data and instructions. The program instructions and data are both kept in read-write random-access memory (RAM). This was an advance over the program-controlled computers of the 1940s, which were programmed by setting switches and inserting patch cables. While program-controlled computers could also be considered UTMs, they required physical manipulation of operators to alter their programming. Von Neumann architecture shifted that manipulation into code.

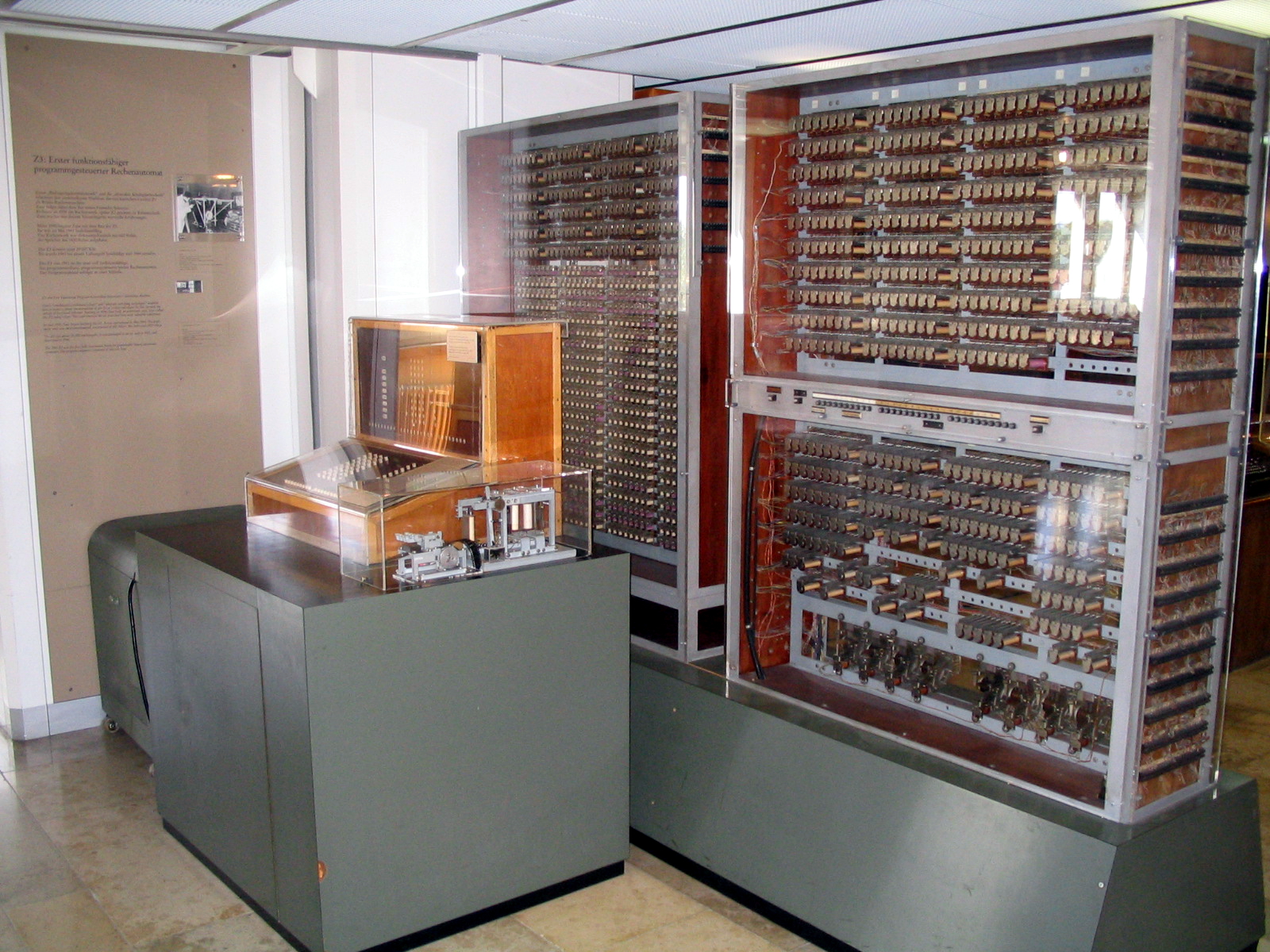

The first Turing-complete computer ever built (Turing completeness = UTM, and the Babbage Analytical Engine would have been Turing complete but was never built) was the Z3, designed by Konrad Zuse and built in Berlin in 1941. The Z3 was the world’s first programmable, digital computer, but it was program-controlled. The Z3 had 2,600 relays and ran at 5.3 Hz. It was not used for war-related computing but was destroyed in December 1943 during allied bombing of Berlin. Other German computers were used to calculate and simulate V2 rocket trajectories.

In 1946 Turing was awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his work, much of which was unknown to the public due to the Official Secrets Act. After WWII, Turing designed the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) between 1946 and 1948. It was one of the first stored-program computers, but a full version of the machine was not completed until after his death in 1954.

In 1950, Turing wrote an article called “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” for the journal Mind. In it he proposed what has become known as the Turing Test in which a human tries to judge whether the responses he receives to questions asked via a blind test are coming from another human or from a computer emulating a human. The ability to pass for human, according to the logic of the test, is the same as being human. Turing doesn’t really address whether the computer is using identical processes as the human to understand and respond to questions, and this has become a central problem in the formulation of questions and claims in not only artificial intelligence but in the science of human thought.