6 Networks

One of the first networks was the semi-automatic business research environment (SABRE) launched by IBM in 1960, which initially connected two mainframe systems and grew into the airline reservation system. In 1963, American psychologist and computer scientist JCR Licklider proposed a concept he called the “Intergalactic Computer Network” when he became the first director of the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). Licklider described it as “an electronic commons open to all, ‘the main and essential medium of informational interaction for governments, institutions, corporations, and individuals.’”

One of the earliest problems discovered by the designers of networks was traffic control. Rather than keep an open line analogous to a telephone conversation, designers chose to divide information up into packets so that the communication circuit was occupied only while the packet was being transmitted and was freed up before and after for other packets. This division of information into discrete packets allowed for much more traffic on a limited bandwidth. Packet-switching wide area networks were actually imagined before local area networks, and in 1965 Donald Davies in the UK proposed a national packet-switched network for Britain. In 1966 Bob Taylor secured funding for ARPANET, the first network to use TCP/IP, developed by Robert Kahn and Vint Cerf. The network was established in 1969, 50 years ago.

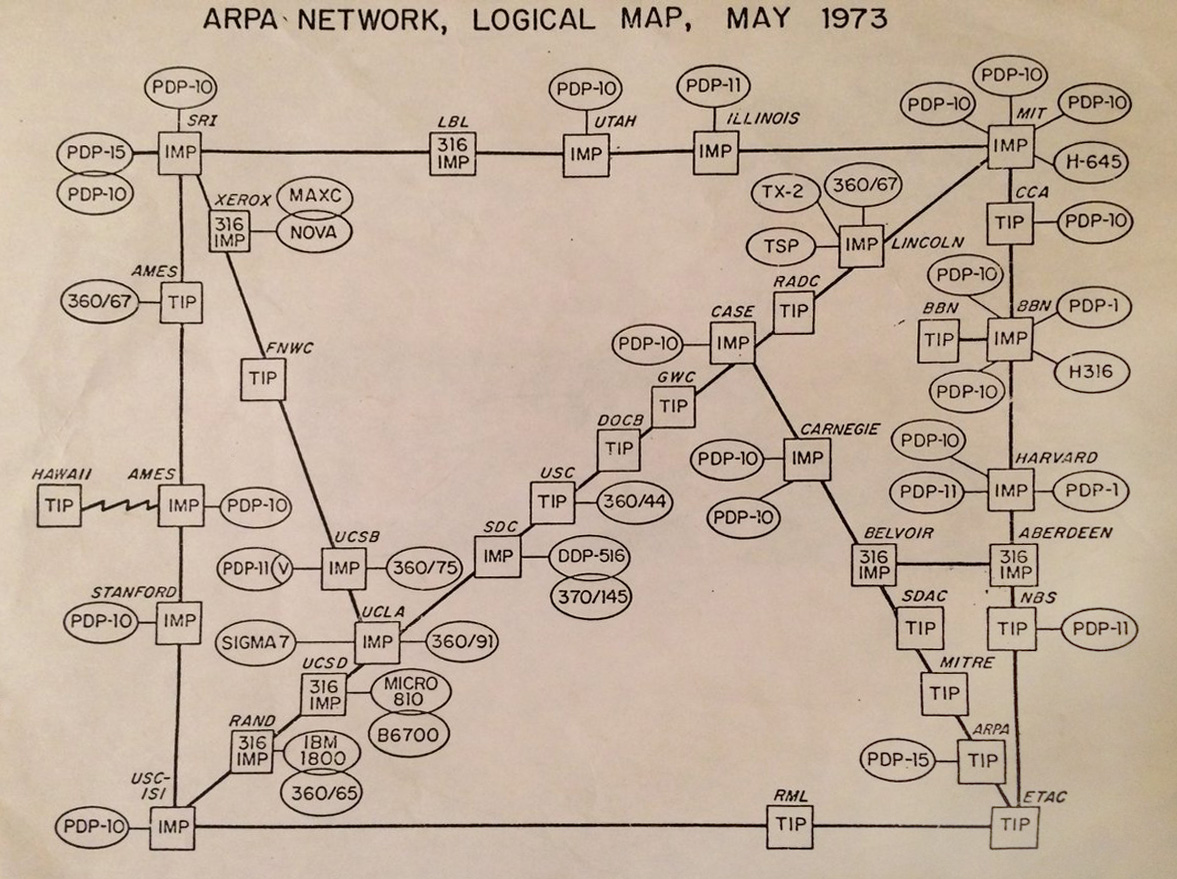

Transmission Control Protocol and Internet Protocol are the two main features of the Internet Protocol Suite known as TCP/IP, which provides for the reliable, error-checked stream of data packets that enables file transfer, email, remote access, and the world wide web. ARPANET was a network of networks, joining government facilities and research universities on what in 1970 became a 230.4 kbit/s backbone that used Honeywell 316 minicomputers as the interface message processor that later became a router. While the internetwork was mostly dedicated to official communications, it was permissible for researchers and users to occasionally communicate personally with each other using email. Commercial and political communications, however, were strictly forbidden.

Initially most wide area networking outside of government was done using dial-up connections over the analog telephone network. One of the first companies to provide access was a Cleveland Ohio insurance company subsidiary that called itself CompuServe. The service, also begun in 1969, was designed as a way to provide in-house computer processing support for the Golden United Insurance Company, and to rent time on the company’s DEC PDP-10 minicomputers to business users. CompuServe was spun off as a separate company in 1975 and began shifting from just selling time-sharing to selling packaged applications.

Users connected with the service via a modem (modulator/demodulator) that converted packets of data to acoustical signals that could be transmitted over analog phone lines. In 1968, the FCC had decided a lawsuit that required AT&T, who held a monopoly on telephone lines in the US, to allow electronic devices to be connected via acoustical couplers (this also enabled the development of answering machines and faxes). Since phone handsets were all identical, a single modem could work with most phones and transmit data at 300 bits/s over standard phone lines.

Rapidly-falling costs of electrical components in the 1970s made direct-connect modems less expensive, and by 1981 a microcontroller was added to the Hayes Smartmodem that allowed it to receive commands from the computer, dial a number, and connect. Modems could be mounted in the expansion slots of microcomputers or connected via an RS-232 serial port. The proliferation of modems attached to personal computers and a speed increase to 1200 and then 2400 bps (also called baud, although baud measures signal changes rather than strictly bits transferred) fueled the rapid growth of Bulletin Board Systems, which were computers running software allowing users to connect to the system using a terminal program, upload and download data files, read news and bulletins, and exchange messages with other users via email, message boards, and sometimes by direct text chatting. Some BBSs hosted single and multiplayer games and many were devoted to a particular interest or topic. At their peak in the mid-1990s, there were over 100,000 BBSs running in the US.

In addition to BBSs, a worldwide distributed discussion system called Usenet was established by a pair of Duke University graduate students in 1980. Users were able to post messages or “articles” into a newsgroup where it could be visible to the world. The advent of the world wide web did nothing to slow the growth of Usenet: in 2019 daily posts are over 100 million and daily volume over 70 TB.

CompuServe competed with BBSs by making local dial-up connections available in every major city. In 1979, Radio Shack began test-marketing a residential information service called MicroNet that did so well that CompuServe renamed it CIS, CompuServe Information Service. At its peak in the early 1990s, CIS ran an online chat system, a message forum platform covering thousands of topics, software libraries for most operating systems, and online games. CIS introduced the Graphics Interchange Format (GIF) for images in 1987, which allowed still and motion graphics to be easily stored and exchanged.

In 1984 a new, family-oriented online service called Prodigy was created by a joint venture between IBM, CBS (which dropped out in 1986), and Sears Roebuck. Unlike CompuServe’s command-line interface, Prodigy offered a graphical user interface (GUI) designed to be more intuitive and easier to navigate. Like CIS, Prodigy made local phone numbers available and routed calls at company expense to a data center in Yorktown New York. By 1990, Prodigy was the second-largest online service with 465,000 subscribers to CIS’s 600,000. By 1993 it had passed CompuServe.

In 1991, an online game provider called Quantum Link transformed itself into America Online and offered a free dial-up trail subscription. In 1992 It added a Windows version of its access software, and in 1993 made Usenet groups available. AOL free trial CDs became ubiquitous; CEO Steve Case has claimed that at one point in the 90s half the CDs produced worldwide had an AOL logo. By the mid-1990s, AOL had passed both Prodigy and CompuServe, even though the service charged by the hour until 1996. In 1997, more than half of all US homes with internet access got it through AOL. In 1998 AOL acquired Netscape, in 1999 MapQuest, and in 2000 AOL merged with Time Warner.

English scientist Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web (WWW) in 1989 and wrote the first web browser in 1990 while working at the particle accelerator at CERN. The browser was released to the public in 1991, just prior to the passage of the High Performance Computing Act of 1991 (AKA the Gore Bill) to create what Senator Al Gore called the information superhighway. The Gore bill funded a National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois, where a team of student programmers including Marc Andreessen wrote the Mosaic browser.

Andreessen graduated, moved to California and met Jim Clark, who had founded Silicon Graphics but had recently left the company. They formed Netscape and made their browser, called Navigator, available for free to non-commercial users. Netscape Navigator did not stay free to all users, which created some confusion. But the biggest difficulty the browser had was Microsoft’s decision to bundle its own browser, Internet Explorer, with Windows 95. IE became the most widely-user browser, holding 95% of the market by 2003. Microsoft made it very difficult for PC OEMS and even users to uninstall IE and use Netscape and Java, which led to the antitrust case argued in Feb 2001, in which the court ruled that Microsoft had violated the law and abused its monopoly powers. Netscape never recovered from losing the “first browser war” and was acquired by AOL in 1999.

Local Area Networks were hampered by Microsoft’s long-term inability to make DOS work as a multi-user system (like Digital Research’s Concurrent DOS). Ethernet network hardware was developed in the 1970s at Xerox PARC by Robert Metcalfe, who co-founded 3Com. There were several competing early topologies such as stars and hardware specs like coaxial cabling, but ultimately the winner was unshielded twisted-pair cable with an RJ-45 8-contact connector. 10-base T operated at 10 Mbits/s, and was gradually improved to 100 and 1000. The software layer’s evolution was even more complicated.

Novell began as a hardware manufacturer CP/M systems in 1979, but shifted its focus to a multi-user operating system it called Netware in 1983. Novell acquired Digital Research in 1991 and used DR DOS as a bootloader. Initially the company planned to challenge Windows with a competing graphical desktop environment, but their greatest success was in small to medium sized office networks. The systems were so difficult to install and maintain that Novell created a certification training program, and Netware Certified Engineers commanded high salaries.

Novell experimented with a variety of systems and applications. They sold most of their UNIX business to the Santa Cruz Operation (SCO) in 1995. For a while they owned WordPerfect and Quattro Pro, office applications that competed with Microsoft. They sold these to Corel in 1996. In 1997, Eric Schmidt became CEO and Novell began to lose ground. Microsoft’s Windows 95, IBM’s OS/2, and Linux all offered network services for PCs, and ultimately Novell adopted Linux. Schmidt became CEO of Google in 2001.

The final network operating system, and the winner by any measure, is the Uniplexed Information and Computing Service, now called UNIX. First developed in the 1970s by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie at Bell Labs, UNIX was available free because AT&T was prevented from entering the computer business under the terms of its 1982 antitrust loss, which had also broken the telephone giant into seven regional “baby Bell” operating companies. AT&T sold its rights to UNIX to Novell, which later sold those rights to SCO. In the meantime, other organizations such as UC Berkeley (BSD), IBM (AIX), Microsoft (Xenix), Sun Microsystems (Solaris), SGI (IRIX) – all of which were proprietary distributions with similar functionality.

UNIX was written in the C programming language (also developed at Bell Labs), so its functions were often emulated by programmers in university computer labs. One of these was Linus Torvalds, a grad student at the University of Helsinki who was frustrated that a free version of UNIX called GNU was not yet available. The GNU (GNU’s not UNIX!) Project had been started in 1983 by Richard Stallman at MIT. Stallman was a proponent of free software, and AT&T’s sale of Bell Labs (completed in 1984) made the source code to UNIX unavailable to universities. Torvalds wrote a kernel he called FREAX, but a coworker who ran the school’s FTP server changed the name.

Linux gained popularity among hackers due to its free distribution and its easy configurability. A programmer could configure the Linux kernel with just the features desired, which led to an explosion of both OS distributions (Red Hat, Debian, Ubuntu, Darwin, Android) as well as use in embedded systems which were becoming popular. PC manufacturers like IBM and Dell adopted Linux as an option to reduce the cost of their systems and break Microsoft’s monopoly on the OS. And organizations like NASA discovered that clusters of networked off-the-shelf PCs running Linux could rival the computing power of proprietary supercomputers. Currently ALL the systems on the Top-500 list run Linux.

Companies such as Sun and SGI that had dominated the high-performance workstation and server business were equally challenged. For example, SGI’s graphics capabilities had caused many applications such as Maya (Alias Wavefront, now Autodesk), Molecular Simulations, Pixar Renderman, Flame, Lightwave 3D, and Power Animator, were all once IRIX-only apps. The ability to build modular Linux distributions and the sheer brute force of Moore’s law combined to make PC clusters as powerful as SGI’s unified memory architecture (UMA) workstations, and it was game over for SGI.