2018

Alisa Hoven: Using Food and Culture to Promote Environmental Justice

Sabine Peterka

Alisa Hoven can spot a good path. She completed a 2,300 mile bike ride, has lead dog-sled trips near the Boundary Waters and enjoys exploring trails along the Mississippi. Each of these activities takes an eye for pathways, and when it comes to advocating for topics she cares about, Hoven can also identify paths for activism to take.

Hoven, who was working for a non-profit in Minneapolis at the time, took a break from grant writing to speak with me about her work in environmental justice. She told me that she often sees two possible paths for environmental justice activism to take. The first is working toward policy changes within the systems already in place. This work is crucial to making communities livable and alleviating pain in people’s day-to-day lives. However, Hoven has found herself beginning to tread more on the second path of activism: creating alternative spaces outside the oppressive systems that dominate society.

“In every moment, in every community, the largest assault to the environment is from white supremacy and capitalism,” Hoven said. “It’s much bigger than a single issue or one fight for one pipeline; it’s such an oppressive system … So I want each community to be building with people who see that whole system and want to dismantle it. Working from one lens of one issue, I think we’re missing our mark.”

Hoven’s past involvement with environmental justice work has been on a larger scale; she has fought for water and against pipelines, even visiting Standing Rock two years ago. In our conversation, she often referred to her role as supporting the environmental justice movement, rather than leading it. But her efforts have certainly inspired action. Recently, Hoven’s values of education and trust-building have led her to become more involved in local environmental justice work. When I asked about her background in environmental justice, she said that the past six months have been a new stage of her journey as she has applied broad values at a more local level. “I’ve always been interested in how humans interact with the Earth and I feel like we make … a lot of poor choices that impact a lot of people unfairly,” she said.

In 2013, Hoven was a member of the Minnesota GreenCorps through the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. This program places AmeriCorps members with organizations to promote future protection of the environment. Hoven was then placed at Hope Community in the Phillips neighborhood in 2018, where she worked as a program coordinator for the Healthy Food Strong Community Program which engages neighbors in urban gardening.

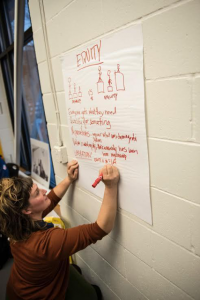

Through neighborhood involvement, Hope Community provided valuable learning opportunities. Hope Community is a nonprofit which started as a homeless shelter in the 1980s. Today, in addition to housing, it provides community gardens and a variety of learning and leadership opportunities. Hope Community is based on a model of engagement, asking the community what changes they want to see and working with them to take those actions. In alignment with this mission, the organization holds regular community listening sessions to provide space for dialog and trust-building. Hope Community also works to involve youth, who survey residents and gather information about the area.

The Phillips neighborhood where Hope Community is located faces a variety of environmental justice concerns, including air pollution, soil contamination and highway construction. Hoven highlighted the irony of sickness and high asthma rates from the air pollution: “The largest polluter in the neighborhood is the hospital,” she told me. Although there are multiple medical buildings in the area, the large facilities worsen the air quality, making people sick. Furthermore, soil was contaminated with arsenic from the CMC Heartland Partners Lite Yard site, a pesticide plant. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) website, it is likely that arsenic spread from the site into residential yards. The plant was in operation from 1938 to 1963 and clean-up was conducted by the EPA from 2004 to 2008. However, some residents did not respond to requests by the EPA to excavate contaminated soil from their property. In addition to soil contamination and air pollution, the Phillips neighborhood is intersected by two interstate highways: 94 in the north and 35 in the west. Hoven noted that the construction of these highways displaced residents.

Phillips is a diverse area, which Hope Community embraces. According to 2012 to 2016 census data, Midtown Phillips is 34% black, 31% hispanic and 25% white. The median household income in 2016 was $45,289 but almost 40% of residents made less than $35,000. To compare, the median household income in the U.S. in 2016 was $57,617. When I spoke with Hoven, she emphasized that this diversity enriches conversations about environmental justice topics.

At Hope Community, Hoven dedicated herself to “Ground Work” in the three community gardens which are active April through October. In total, 7,500 square feet of growing space are used and managed by Hope Community and surrounding neighbors. There are also two community kitchens and year-round skill-sharing opportunities such as open garden nights and cooking groups. Hoven told me that many neighbors are eager to share their skills. With a diverse population, everyone has something to teach and something to learn.

“[Ground Work is] focused and centered on food and reclaiming our connection with the land and with each other,” she said. “It’s a super diverse block where there’s lots of different cultures and identities and experiences that get to be in space together and can provide very fruitful, honest conversations and also moments of humility.”

In Ground Work, community members are encouraged to explore their cultural relationship with the Earth, learning about plants their ancestors grew and sharing family recipes. Growing, cooking and eating can help people to express and share ideas about home, famine, war, corruption and capitalism. This work centers on the question “What are our stories of food and culture and where do we come from?” In fact, Hoven uses food as an entry point into deeper conversations on environmental justice topics. Growing, cooking and eating can help people to express and share ideas about home, famine, war, corruption and capitalism. When I asked Hoven about using food as an access point, she noted that identifying or discovering one’s relationship with the land is an important step.

“Learning and continuing to connect to your own personal story of where your people come from and what relationship they had with the land, what harm and healing has happened – that’s important I think with any work,” Hoven said.

In fact, Hoven has enjoyed diving into her own ancestral histories of hurting and healing. To reflect on the harm and healing related to one’s heritage without bringing guilt is extremely valuable, she said. She told me that coming from a healthy identity and a place of trust and loving allows for more open communication with coworkers. An awareness of her own identity has helped her find her role in her work.

“I am a European identified cis female who comes from more of a middle-class background, and that’s not a common demographic in the community,” Hoven said. “I definitely am in community with an awareness of that privilege that I bring.”

Being conscious of her identity allows Hoven to build trust through commitment and open communication. She said that through her work, she rejects charity models and mindsets, seeking to work with — rather than for — the community. Joining a project because it is well-funded does not earn trust, Hoven told me. Having devoted herself to work in the Phillips community for almost five years, Hoven has proven persistent dedication.

“[To build trust,] come in with humility and really wanting to work with the community to create change,” Hoven said. “I do not believe that [a charity mindset] is how transformational change happens. So I’m just generally in the midst of people sharing about my lived experience and hearing theirs.”

Hoven is also conscious of when to step in or step back. With a laugh, she mentioned that as a quiet Midwesterner, outspokenness does not come naturally. While she challenges herself to use her voice to push where and when she sees a need, she also recognizes that she is not equipped for every job. A new Wellness Garden project meant to provide for people of color, for example, is something she strongly supports but will not lead. Rather, Hoven said her role is to listen.

“[I am] definitely working to listen and understand people’s experiences,” she said. “And I think the main pillar of my work or sort of my goal is to listen and help make the connections that people want to make the changes they want to see. I am definitely more of a leader on the side.”

Hoven left her work at Hope Community in the summer of 2018. In the past six months, she has delved into more local environmental justice work by starting her own LLC, named Wild Heart. Wild Heart is centered on garden services + education. She hopes to bring that into community work, with the overarching goals of “…nourishing food for humans while creating spaces for pollinators”. Hoven has been able to provide gardening services amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, but has had to pause her educational efforts due to social distancing and the ways of coming together in person are made more difficult by the pandemic. She hopes to offer more education and workshops once we come back together.

“Part of the reason why I started the LLC…was because I wanted to keep my hands in the dirt and work directly with the communities. I also have more autonomy working for myself, allowing me to focus on whichever projects I think I could help most with.”

Hoven is spending part of her summer at Buttermilk Falls CSA & Folk School Retreat, a farm in Osceola, Wisconsin. Individuals who visit or work at the farm are given the room to reflect on this history and are encouraged to reflect on their own histories and lineages in the process.Buttermilk Falls is a nonprofit farm that “…creates direct connections between the people who eat the food, the land, and the people who grow the food.” They plant, grow and harvest their produce without using any harmful herbicides, pesticides or insecticides, aiming to maintain a healthy relationship with the land they are on. There is also a focus on understanding the history of the land that is being farmed, where individuals who visit or work at the farm are given the room to reflect on this history and are encouraged to reflect on their own histories and lineages in the process.

During her time at this farm, Hoven develops a curriculum and manages day camps for children, educating them on gardening and the importance of having a relationship with their food and where it comes from. She is currently exploring the ways she can decolonize her teaching practices and show up fully and honestly to the hard life-long work of coming back to each other and the land.

“Teaching these children and working with these communities, I am often asking myself ‘How can we honorably harvest something from the land (a concept she learned from Robin Wall Kimmerer)? What has enabled us to be around gardens?’ I think these food stories and really questioning the ethics behind our work is key to bringing us closer to the land and each other.”

She sees value in celebrating small moments, even if complete healing is still a long way off. Maybe her goal of food, water, medicine and liberation for everyone will not come to fruition in her lifetime, but she believes that the people she impacts in her life can carry that work to the next generation and beyond. For now, victories like a good growing season are well worth recognizing.

“There’s a lot of healing work to do,” she said.

While this may be true, Hoven seems to be on a path toward the creation of new, liberating systems of environmental justice. In our conversation, Hoven painted a hopeful and idyllic image of “small, integrated communities who work to grow and share food together” with an emphasis on mutual aid autonomy. Hoven’s healing work promotes healthy relationships among neighbors, with the planet and with the past. And it all starts with food.

References

Buttermilk Falls CSA & Folk School. (n.d.). Retrieved July 08, 2020, from http://www.buttermilkcsa.com/

“2013: Member – Alisa Hoven.” Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Accessed 9 April 2018 https://www.pca.state.mn.us/2013-member-alisa-hoven.

Hope Community. Accessed 9 April 2018. http://hope-community.org/

“Midtown Phillips Neighborhood.” Minnesota Compass. Accessed 1 May 2018. http://www.mncompass.org/profiles/neighborhoods/minneapolis/midtown-phillips#notes

“Minnesota GreenCorps.” Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Accessed 24 April 2018. https://www.pca.state.mn.us/waste/minnesota-greencorps#about-85f9daae

“South Minneapolis Residential Soil Contamination, Minneapolis, MN.” United States Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed 1 May 2018. https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.Cleanupid=0509136#bkground