2018

Abé Levine: Placekeeping as a Strategy for Environmental Justice

Adele Welch

“We are, in a sense, seeing each other as separate which is not entirely healthy,” community organizer Abé Levine told me over Google Hangout. He paused thoughtfully before continuing, his microphone picking up his gentle and clear voice. “People need to understand we’re all part of one community.”

Levine’s environmental justice activism brings people together in social contexts such as the garden, kitchen, and meeting room. He works as a Program Assistant at Hope Community in South Minneapolis on youth programming and policy initiatives. The organization started in the 1970s as a shelter and hospitality house, but currently operates as a community center whose goal is to “present an alternative to gentrification.”

Levine and Hope Community take a collective approach to activism because both are aware that not one individual or institution holds the answers to community problems. As a transplant to the Twin Cities himself, Levine is keenly aware of his positionality. Throughout this profile piece, I focus on how Levine and Hope Community effectively engage with environmental justice organizing through the process of “placekeeping,” which preserves cultural resources and knowledge by exposing and supporting what demands already exist within a community. Levine is able to leverage his multiple identities by acting as a facilitator instead of a producer of solutions.

Placekeeping: an introduction

The term “placekeeping” is a relatively new response to the concept of “placemaking,” which has roots in the 1960s. Placemaking refers to the process of improving a neighborhood or larger city through investment in public spaces such as parks, plazas, and streets. According to the Project For Public Spaces, placemaking refers to, “a collaborative process by which we can shape our public realm in order to maximize shared value.”

However, placemaking as it was historically practiced wasn’t enough for many low-income communities and communities of color because of the threat of gentrification. As the quality of public spaces improved, property values rose, and many local residents were forced to leave the spaces they had physically and symbolically constructed. While PPS currently emphasizes the role of local community involvement in placemaking, a new expression, “placekeeping” more directly underlines the need to preserve a place’s existing community and cultural assets while working to improve its condition.

While both words are sometimes used interchangeably, “placekeeping” gained popularity in the late 2000s. “Placekeeping has been described as the active care and maintenance of a place and its social fabric by the people who live and work there. It is not just preserving buildings but keeping the cultural memories associated with a locale alive,” U.S. Department of Arts and Culture representative Jess Solomon explained. Cultural activist Roberto Bedoya is known for offering the example of “Rasquachification” as placekeeping, which refers to an aesthetic expression of intense colors and decorations in Mexican-American neighborhoods. Maintaining the cultural memories of a place reclaims the artistic processes of low-income communities and communities of color while working against gentrification and displacement.

Levine defines placemaking and placekeeping in a similar manner. “Placemaking is the idea of generating a culture where maybe it’s lacking or needs revitalization, and placekeeping is unearthing the stories and assets that already exist here,” “Placemaking is the idea of generating a culture where maybe it’s lacking or needs revitalization, and placekeeping is unearthing the stories and assets that already exist here.” he explained to me. Hope Community puts placekeeping into practice by holding listening sessions to connect and equip community leaders. While the organization and Levine works to improve the economic and environmental conditions of the Phillips and Cedar-Riverside neighborhood, they recognize that they are not and should not be alone in brainstorming solutions. Levine is reflective on how his identity shows up in practice and how his background led him to environmental justice organizing, which ultimately leads to more effective strategies for change.

Levine’s background

Levine cites his cultural context, family, and education as major influences on his interest in environmental justice. He grew up outside of Boston near nature reserves, including one of Harvard’s Arboretums. “I grew up in the city but was surrounded by nature and opportunities to run around … I feel like that was super critical in my development,” he said. “It’s something I wish every community had.” He described his childhood neighborhood as working class, queer, Puerto Rican and Asian, but dealing with gentrification. Despite this, Levine had a positive relationship with public natural spaces from a young age.

Levine also told me about how his family impacts his current work in food justice. “I had access to cultural foods that were important to me and that was an important form of community building,” he said, citing his grandmother as the organizer of the family. Every Sunday, Levine remembered affectionately, she would gather the family around traditional Chinese dishes. Bringing people together around cultural foods continues to be an important aspect of Levine’s work, especially with youth, and he upholds that food is “a big vehicle for [placekeeping].” On the younger end of the family, Levine’s adopted sister influenced his interest in youth work. While helping raise her, he said, he was, “thinking about how you educate, how you have conversations, how you have learning activities around these bigger, heavier things, that are hands-on and enriching.”

These “bigger, heavier things” Levine mentioned could be a reference to the broader, often times oppressive systems that shape society he learned more deeply about at Macalester College. Through studying the education system, farming system, and the environment in particular, Levine graduated with a greater understanding of environmental justice that he puts to use as an organizer.

How Levine placekeeps: youth work and policy

Levine works for Hope Community’s Food, Land, and Community initiative. He employs environmental justice placekeeping in two main areas: youth programming and policy. The youngest person he works alongside is four years old, and the oldest are over 65.

“A youth culture of food”

As a community center, the Hope Community building includes a kitchen, garden, and technology space for children and young people to spend time in after school and during the summer. Youth work was the first topic Levine brought up in our interview. “We’re doing just basic learning about food, the harvest, the ecosystem, and trying to get youth into more positions of leadership,” he described. Most of the youth that Levine works with are between five and thirteen years old.

Levine’s specific programs include a weekly dinner night for young people and their families and a Food & Photo Project aimed at teenagers. Just like he was able to connect with his cultural heritage and environment through food as a child, Levine is interested in cultivating a “youth culture of food, food activism, or food engagement” in South Minneapolis. According to Levine, food is a powerful part of environmental justice because it has to do with, “people feeling like their own culture is represented … as well as looking into how we can grow more on public land.” Opportunities to garden and cook can help, “people [feel] ownership and autonomy in their neighborhoods,” he continued. Through the Food & Photo project, Levine hopes to engage youth with food through art. “There’s just room for … people being able to express their full selves and identities in work,” Levine said, particularly through creative projects. Placekeeping emphasizes both community autonomy and artistic expression, which Levine cultivates among young persons.

Looking into the future, Levine is interested in involving more young people in policy and research. He cited the organizing around Minneapolis public parks as a site for youth engagement. “It’s the place that they are; it’s their space,” Levine stated. Young people should be involved in the policy conversation about, “how that land is owned and benefits community,” he continued, cycling back to the concept of placekeeping as benefiting all community members. Additionally, Levine mentioned Youth Participatory Action Research as a framework he is interested in exploring for a summer program. Ideally, he would interview young people for a 13-week, paid summer research cohort about social justice in South Minneapolis.

While retaining youth is difficult in the out-of-school time field, Levine strives to operate from a youth-centric perspective to sustain and improve Hope Community’s programming. He prioritizes listening to young people, following through on what interests them, and sometimes just giving them space. “I might just leave for a while and let young people do their thing,” he laughed. He also speaks with parents, guardians, and elders to leverage the assets of students’ families. In addition, Levine asserted that increased partnerships would strengthen Hope Community’s youth work, such as partnerships with different daycares, youth organizations, and activists, especially those working in rural settings. As a leader, Levine employs placekeeping by facilitating intra-group and extra-group dialogue in the community to connect people, utilize existing resources, and cultivate change.

Policy: “a constant negotiation”

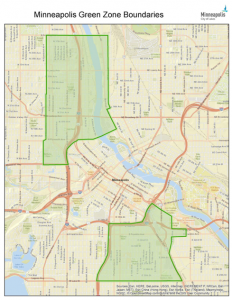

Levine balances youth programming at Hope Community with city-level policy work. Currently, the organization is involved in Minneapolis’ Green Zones Initiative.

“Green Zones is a model that started in Los Angeles amongst, I would say predominantly black and brown, disenfranchised communities that have experienced a lot of environmental racism,” Levine told me. “[They] came together to proactively develop policies that would protect their communities and move their communities forward.” Thanks to the Minneapolis Climate Action Plan Environmental Justice Working Group, Minneapolis has designated two areas in South and North Minneapolis as Green Zones. The City of Minneapolis describes Green Zones as, “a place-based policy initiative aimed at improving health and supporting economic development using environmentally conscious efforts.”

Levine organizes and attends meetings teaching community members what Green Zones are and how they can provide input on specific policy. He is interested in making sure the zoning process is conducted in a holistic manner that takes into account green jobs, air, soil, and water quality, equity and anti-displacement, food access, and energy and homes. While he said he is excited to come back to Hope Community’s principles of anti-displacement, Levine also expressed frustration about policy’s bureaucratic nature and time-consuming complexity.

“[Policy] is a constant negotiation. It should be very simple to say like, hey rent’s increasing at a rapid rate, and people’s incomes, particularly Black and Latino families, are decreasing. There should be a way to control the rent so that it’s affordable to people. But it’s a process to do that,” Levine explained. While policy may be uninviting for the average person, Levine breaks down the process for community members so they have the tools to influence decisions. Placekeeping emphasizes the empowerment of local persons to create positive change, and policy is an influential sphere that Levine attempts to bring more community members to.

Placekeeping as a framework

Placekeeping is not only a strategy, but a framework as well. While Levine’s work is across the board, he organizes with a few of his own best practices in mind that tie his approach together. He analyzes and utilizes his own identity, is cognizant of cultural boundaries of the community, stresses his role as a facilitator, and develops trust over time. These methods strengthen the placekeeping process. The following tools can function as recommendations for all community organizers.

Reflect on and leverage identity

Levine describes himself as a mix of identities, some of which are privileged and some are not. He is able to bring all of the intersections of his identity in his work. Levine specifically talked about his self-assessed educational privilege, housing privilege, and job privilege. While bringing comprehensive knowledge from his educational background can help put Hope Community’s work into context, Levine stated he often, “[thinks] about if I should be the main voice in a space.” Levine also celebrates the assets that come from his marginalized identities. “I try to share … the stories of my family, I try to share Chinese cultural foods or traditions,” he told me. By presenting his identity with pride and honesty, Levine is able to communicate on shared levels with the community members he works with. However, he is careful not to assume homogeneity with his own background. This aids in the placekeeping process by building a respectful environment.

Learn cultural boundaries

“This is a large Somali community, so [I try] to learn a little bit of the language and also what cultural boundaries exist,” Levine told me. By paying attention to specific cultural customs, Levine shows community members that he values their safety and background. He demonstrates that he cares about the cultural assets that community members bring to a space, which is necessary if placekeeping attempts to preserve them.

Facilitate instead of create

“I’m not here to create solutions for people’s lives, but if anything, to listen, to facilitate programs, [and] to hold space,”“I’m not here to create solutions for people’s lives, but if anything, to listen, to facilitate programs, [and] to hold space.” Levine said. Uncovering what needs already exist within a community is an integral part of placekeeping. Instead of coming in with solutions, Levine emphasizes that the kitchen and garden is “always a space to [listen].” Levine’s work is not passive, but focuses on creating structures for people to take their stories and curiosities and, “move to a place of leadership or changemaking.”

Practice patience

Levine understands that placekeeping is built from authentic relationships, which take time to cultivate. He said he, “[moves] at the speed of trust” to “[develop] relationships over the long haul.” By allowing community members, especially youth, time to grow into their identities, Levine creates a comfortable atmosphere at Hope Community. Placekeeping is not a quick fix, and Levine is concerned with sticking around and getting to know the community, which builds trust and helpful vulnerability.

Conclusion

Levine and Hope Community’s framework of “placekeeping” demonstrates a sustainable and useful approach to community organizing. He works for environmental justice through youth work and policy by tapping into existing community knowledge and resources to support effective solutions. For example, he aims to create local research-based organizing opportunities for young people, and trains community leaders to influence city-wide policy that affects their neighborhood.

Levine sustains his placekeeping approach by grounding himself in his own identity and background, such as his family’s Chinese heritage and food customs as well as his experience playing outdoors as a child. Regardless of whether or not his identities match the communities he is working with, he employs placekeeping strategies to cultivate an environment of respect, safety, and trust at Hope Community. Levine is a placekeeping facilitator, and all organizers can learn from this approach.

Levine and I ended our Google Hangout talking about the future of environmental, economic, and social justice activism in Minneapolis. “I’m really excited to see that, there is an upswing of activism and taking issues into our own hands,” he said, his voice lively. “Young people as well, are out there.”

References

“Food, Land, and Community.” Facebook. Accessed May 01, 2018. https://www.facebook.com/hopegardens2017/.

“Green Zones Initiative.” City of Minneapolis. May 02, 2018. http://www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us/sustainability/policies/green-zones.

“Home.” Hope Community. 2018. http://hope-community.org.

“Human Rights and Property Rights: Placemaking and Placekeeping.” U.S. Department of Arts and Culture. March 21, 2016. https://usdac.us/news-long/2016/3/20/0iu8rr9hmo2a9aqnmdup9budjjxjm8.

Roberto Bedoya. “Spatial Justice: Rasquachification, Race and the City.” Creative Time Reports. September 15, 2014. http://creativetimereports.org/2014/09/15/spatial-justice-rasquachification-race-and-the-city/.

“What Is Placemaking?” PPS. 2018. https://www.pps.org/article/what-is-placemaking.