I Fight No More Forever: The Nez Perce War of 1877

In September of 1805, the ragged and starving men of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery stumbled out of the Bitterroot Mountains and onto the Weippe Prairie (near present-day Weippe, Idaho) and made the first direct contact with the Nez Perce. Startled by the desperate condition of the expedition’s men whose unkempt beards and foul smell suggested to Twisted Hair’s band that the strangers might be half-dog. The band nevertheless provided them food and shelter. The following spring, Lewis and Clark’s men lodged with the Nez Perce again and, in May, William Clark recorded that their hosts had shown “greater acts of hospitality than we have witnessed from any nation or tribe since we have passed the Rocky Mountains.” Upon the corps’ departure, the parties agreed to ongoing “peace and friendship.” Some seventy years later, with this once-strong relationship in tatters, several Nez Perce bands led the United States military on a nearly four-month, 1500-mile chase that remains one of the most remarkable military feats in all of American history.[1]

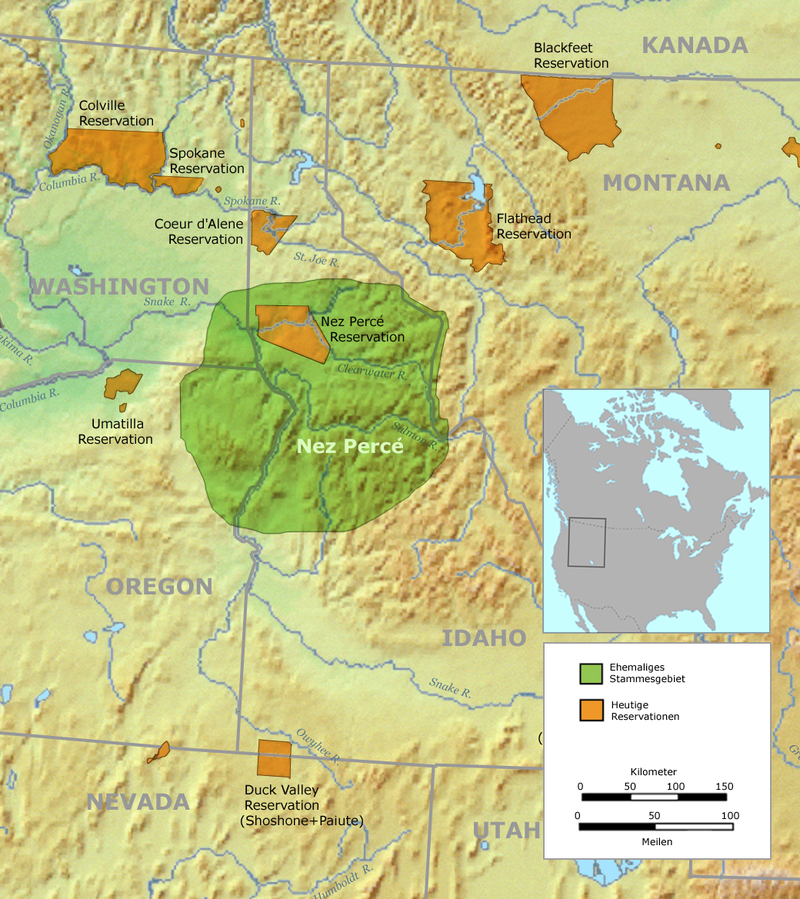

At the time of contact, Twisted Hair’s band was one of many small independent bands of Nez Perce totaling approximately 4,000 and occupying 27,000 square miles on the Columbia Plateau (centering on North-central Idaho, but reaching Southeastern Washington, Northeastern Oregon and into Western Montana) [see map].

Ancestorial Lands of the Nez Perce

But in the wake of Lewis and Clark, the pre-contact life ways of the Nez Perce where the often-isolated bands moved with the seasons and came together in larger groups only several times a year fundamentally changed.[2]

In a sequence of events that had become familiar with indigenous nations further east, the Nez Perce became dependent on trade and shortly thereafter saw their culture challenged by missionaries. Although proving more resistant to economic dependence than many other indigenous nations, by the late 1820s Nez Perce men became consistent participants in regional trading rendezvouses. More influential, however, was the Nez Perce reaction to the efforts of protestant missionaries who arrived in the late 1830s. Learning of what they called the Book of Heaven from Lewis and Clark and later from mountain men and traders, some Nez Perce showed a willingness to embrace this new religion. Tuekakas, a well-respected headman in the remote Wallowa Valley in eastern Oregon adopted the new religion and encouraged his followers to do the same. In 1840, he and his wife had a son, Thunder Rolling Down a Mountain, who they baptized and gave the Christian name Joseph. But in the first decade of Joseph’s life, the missionaries’ appeal began to fade for his father. As thousands of settlers traveled past Nez Perce territory along the well-worn Oregon Trail, missionaries dictated harsh rules to the Nez Perce and enforced them by public corporal punishment. In the face of this influx of foreign people and culture more remote bands of Nez Perce, including Tuekakas’s Wallowa band, withdrew from extensive white contact and returned to their more traditional ways of life.[3]

Soon missionary efforts gave way to waves of settlers. By 1850 an estimated 13,000 non-indigenous people were living in Oregon Territory. Soon after it became clear to the government that legal title to land on the Columbia Plateau was a necessity. In 1855, Isaac Stevens, the Governor of the newly created Washington Territory, arrived on the Plateau with a mandate to acquire title to the lands occupied by the Cayuse, Umatilla, Walla Walla, Yakima, and Nez Perce. After weeks of negotiations, the tribes agreed to cede 31 million acres in southeastern Washington and northeastern Oregon. The Nez Perce did so because the treaty created a large reservation encompassing most of their homelands and protected their right to use ceded lands as they always had. But treaty ratification was held up in the US senate for nearly four years and government promised payments and border protection failed to materialize.[4]

Less than a year after the treaty was ratified in March of 1859, prospectors discovered gold on the new reservation. Before the year was out, 8,000 miners rushed to the strike location and invaded Nez Perce land. Rather than trying to protect the reservation the government decided to negotiate a new treaty. But during the 1863 negotiations, the Nez Perce could not act in unison, and after the lengthy tribal council some bands, including Tuekakas’s Wallowa band, decided to break with the more assimilated bands and leave the council. In their absence, Lawyer, a leader of an assimilated band who had been designated as the “Head Chief of the Nez Perce” by the government (but not by the Nez Perce) signed a new treaty that reduced the reservation to 1/10th its original size. According to this new treaty the lands of what became known as the non-treaty bands of Nez Perce lay outside the new reservation mandated by a treaty the bands never signed.[5]

For a time the non-treaty bands were mostly too isolated to have much contact with the constant stream of white settlers, but eventually the influx began to encroach on the their lands. In 1871 the now-aged Tuekakas counseled his son Joseph: “Never accept any gifts” from white men, “They will say that you have sold something.” He continued, “you must stop your ears whenever you are asked to sign a treaty selling your home. This country holds your father’s body. Never sell the bones of your father and mother.” Young Joseph, along with his brother Ollokot, granted their dying father his final request.[6]

The brothers’ promise proved difficult to keep. Within a year of their father’s death homesteaders began to graze cattle and stake claims in the Wallowa Valley. Joseph met these intruders with a respectful but firm message: neither he nor his father had ever sold the land and that they were unwelcome. Tensions rose and an 1873 government attempt at dividing the valley between settlers and Nez Perce failed and was rescinded in 1875. Instead, all non-treaty Nez Perce lands were to be opened for settlement and the Nez Perce relocated to the 1863 reservation. Tasked with this feat was General Oliver Otis Howard, the head of the army’s Department of the Columbia. Howard, a Civil War veteran who had been a champion of freedmen after the war, hoped that he could find a mutually agreeable solution to what initially seemed a minor concern.[7]

In 1875, General Howard met with Joseph reporting later, “Joseph and I became quite good friends.” Shortly after he wrote Washington advocating for Joseph’s claim to their ancestral lands. “It is a great mistake to take from Joseph and his band of Indians that valley… possibly Congress can be induced to let these really peaceable Indians have this poor valley for their own,” he counseled. But in June of 1876, just as a high-profile murder left one of Chief Joseph’s friends dead at the hands of white settlers and the Nez Perce clamoring for justice, Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne annihilated George Custer and his entire command at the Little Big Horn. With the Wallowa Valley in crisis, the nation was no longer in the mood to consider compromise.[8]

The following May a heated council convened at Fort Lapwai where Howard, forced to execute government policy, told Joseph and leaders of other non-treaty bands (Looking Glass, White Bird, and Toohoolhoolzote) that they must bring their bands to the reservation within 30 days or his army would forcibly move them. Only Joseph and Looking Glass’s restraint prevented the assembled Nez Perce from slaughtering the massively over-matched military garrison. Cooler heads knew that while an immediate and complete military victory was achievable, such a victory would bring overwhelming retaliation. Reluctantly, the non-treaty leaders left the council agreeing to bring their people to the reservation.[9]

As the bands gathered and made their way toward the reservation in June, a tense situation deteriorated into bloodshed. To avenge the murder of his father, Wahlitits and several accomplices snuck out of the camp and killed the known murderer and two others. Fueled by a long list of grievances, frustration, rage and alcohol other Nez Perce young men left the camp and attacked horrified homesteaders. By the time news reached General Howard, eighteen settlers lay dead, and rumors of real and imagined Indian atrocities had thrown the plateau into a panic. Promising to “make short work of it” Howard dispatched about 100 mounted troops. At White Bird Canyon on June 17th Nez Perce warriors attacked the soldiers’ flank, killing 33, and sending the rest into a confused retreat. Hastily, chiefs organized their bands and fled as Howard called for reinforcements.[10]

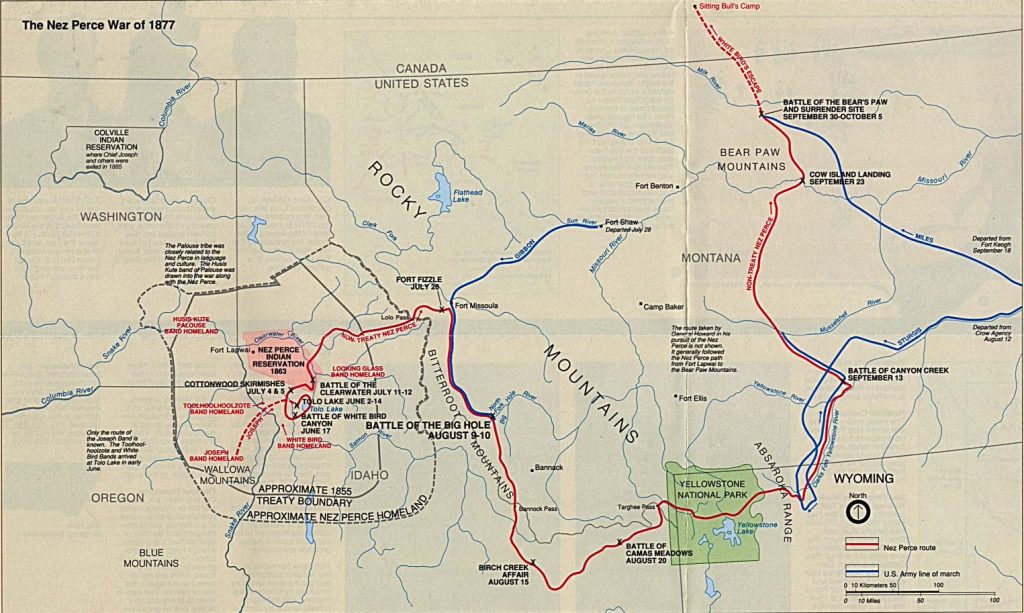

With only about 200 warriors, the Nez Perce fled with 600 non-combatants, all of their possessions, and a horse and livestock herd that numbered between two and three thousand. Despite these challenges, they were able to distance themselves from Howard’s pursuing army. After retreating from a two-day battle at Clearwater on July 11-12, they moved northeast across Idaho and over the difficult Bitterroot Mountains. Elected trail chief and main military strategist, Looking Glass incorrectly assumed that Howard would not follow them into Montana and that their allies, the Crow, would provide safe haven. After traveling south along the Bitterroot River and knowing that General Howard was days behind at worst and had given up all together at best, Looking Glass allowed his weary people to rest at a plateau surrounded by mountains known as the Big Hole. Unbeknownst to them, Colonel John Gibbons had organized a military force from western Montana and utilized Bannock scouts to track the Nez Perce to the Big Hole. Before dawn on August 9th, Gibbons attacked the unsuspecting Nez Perce and killed nearly 90 mostly women and children in the opening minutes of the conflict. In the fiercest fighting of the war, the Nez Perce regrouped and forced the soldiers back. The following day, warriors pinned down Gibbon’s troops as the non-combatants fled south and then east toward the newly designated Yellowstone Park.[11]

After eluding US troops under Colonel Sturgis in Yellowstone, Nez Perce relief turned to despair when they learned that the Crow would not assist them, but rather were working as scouts for the soldiers. Out of options, the Nez Perce turned to their last hope – to travel north across Montana to Canada where Lakota Chief Sitting Bull had found sanctuary and established a camp after his victory at the Little Big Horn. On September 13, they fought off Sturgis’s troops at Canyon Creek before crossing the Missouri River ten days later. Having distanced themselves from Sturgis, who was joined now by Howard, the Nez Perce slowed their pace in hopes of providing some comfort to their sick and exhausted people. A day’s march from Canada, they camped at Snake Creek in the shadows of the Bear Paw Mountains. What the Nez Perce didn’t know, was that Howard had dispatched a mounted force under the command Colonel Nelson A. Miles from Fort Keogh in Eastern Montana on September 18th. Miles, traveling with fresh, better-supplied troops traveled briskly in a northwesterly direction and reached the Nez Perce campsite at Snake Creek on September 29th.[12]

Nez Perce War 1877 – Map

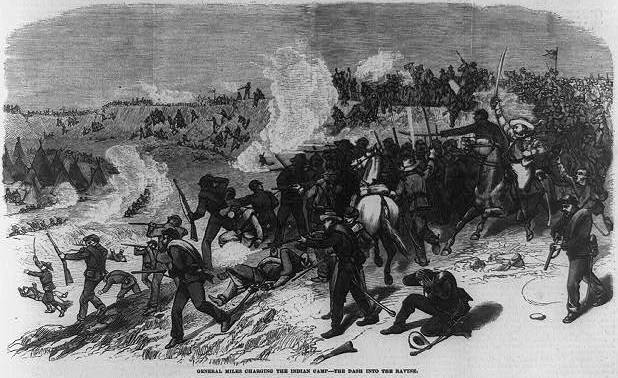

The Nez Perce awoke on September 30th with the ground shaking from a fierce cavalry charge of some six hundred mounted soldiers. Warriors quickly organized and repelled the soldiers. After two more failed assaults, Miles settled in for a siege and the Nez Perce with the horses driven off realized they were finally trapped. With negotiations already underway, General Howard reached the battlefield on October 4th.[13]

Battle of the Bear’s Paw

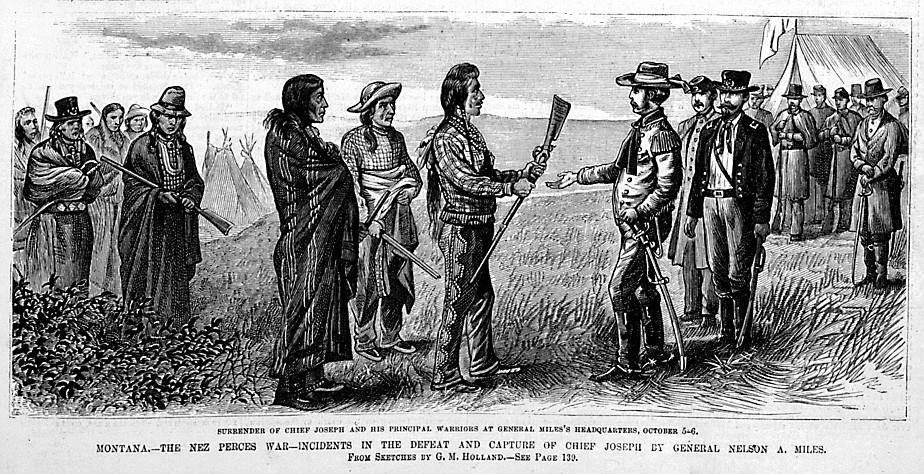

Because Howard had negotiated primarily with Chief Joseph prior to the onset of bloodshed, he assumed Joseph was singularly in command of the Nez Perce retreat. In reality, Joseph played little role in defining strategy but rather was in charge of establishing, organizing, and moving the camp. The trail chiefs, Looking Glass and later Poker Joe were the true Nez Perce strategists. Regardless, Howard’s war dispatches captured the nation’s attention as they characterized Joseph as the “Red Napoleon” and the mastermind behind the Nez Perce fighting retreat. Because both Looking Glass and Poker Joe had been killed in the final battle and White Bird had decided to take those willing and sneak out of the soldiers noose toward Canada, Chief Joseph added to his legend by taking the lead in the negotiations to end hostilities.

General Howard, Colonel Miles and Chief Joseph

- General Oliver O. Howard

- Chief Joseph

- Colonel Miles Nelson

NOTE: You can click on the images to enlarge them. Use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Promised that he and his people would be allowed to return to their homeland in the spring, Joseph agreed to surrender the 418 Nez Perce who remained.[14] They had come some 1500 miles, befuddled 2,000 troops sent against them, and were within 40 miles from Canada. In a speech translated from a second-hand retelling that has since become famous, Joseph purportedly declared:

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead… It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are — perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.

But Miles’s promise to Joseph was over-ruled by General Sherman and the surrendering Nez Perce were first sent to Kansas and then to Oklahoma. Joseph continued to advocate eloquently for his people, even meeting with President Hayes in 1879. Eventually, in 1885, his people were allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest, however, they were divided. Joseph and half of his number were sent to a reservation in northern Washington, segregated from the rest of his people who were sent to an Idaho reservation. For nearly twenty more years Joseph continued to lobby fruitlessly for his people’s return to his Wallowa Valley. When Joseph passed away in 1904, his doctor attributed his death to “a broken heart.”[15]

Good Words

“The first white men of your people who came to our country were named Lewis and Clark….All the Nez Percés made friends with Lewis and Clark and agreed to let them pass through their country, and never to make war on white men. This promise the Nez Percés have never broken. It has always been the pride of the Nez Percés that they were the friends of the white men.”

-Chief Joseph, 1879[16]

“The Indians throughout displayed a courage and skill that elicited universal praise. They abstained from scalping; let captive women go free; did not commit indiscriminate murder of peaceful families, which is usual, and fought with almost scientific skill….Nevertheless, they would not settle down on lands set apart for them…and when commanded by proper authority, they began resistance by murdering persons in no manner connected with their alleged grievances….They should never again be allowed to return to Oregon.”

-William Tecumseh Sherman, 1877[17]

- Brian Schofield, Selling Your Father’s Bones: American’s 140-Year War Against the Nez Perce (New York: Simeon and Schuster, 2009), 12-14, cover flap; Kent Nerburn, Chief Joseph & The Light of the Nez Perce (New York: HarpersCollins, 2005), 3-8. ↵

- http://www.nezperce.org/history/frequentlyaskedq.htm#where; Nerbern, Chief Joseph, 8-9, 51 ↵

- Nerbern, Chief Joseph, 13-28, 30-32; Schofield, Selling Your Father’s Bones, 13-17, 29. ↵

- Nerbern, Chief Joseph, 46-49; Schofield, Selling Your Father’s Bones, 32-34, 41; “1855 Treaty Sesquicentennial,” Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, available online as of November 2, 2012 at: http://www.umatilla.nsn.us/Treaty150.html#anchor63292; “Treaty With The Nez Perce, 1855.” Available online as of November 2, 2012 at: http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/vol2/treaties/nez0702.htm ↵

- Nerbern, Chief Joseph, 53-54, 56-59; Schofield, Selling Your Father’s Bones, 37-38; “Treaty with the Nez Perce Indians, 9 June 1863,” available online as of November 2, 2012 at: http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/nez0843.htm ↵

- Nerburg, Chief Joseph, 61-62 ↵

- Schofield, Selling Your Father’s Bones, 49-51, 55; Nerburn, Chief Joseph, 64-69, 72-73 ↵

- Schofield, Selling Your Father’s Bones, 56-57; Nerburn, Chief Joseph, 69-73; “Little Bighorn Battle Field,” National Parks Service, available as of November 4, 2012 at: http://www.nps.gov/libi/index.htm. ↵

- Schofield, Selling Your Father’s Bones, 72-75; Nerburn, Chief Joseph, 77-83. ↵

- Nerburn, Chief Joseph, 90-99. ↵

- “Good Words,” The West: Episode Six (1874-1877) Fight No More Forever. Transcript available online as of November 10, 2012 at: http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/program/episodes/six/goodwords.htm ↵

- “The Flight of the Nez Perce,” available online as of November 12, 2012 at: http://www.ourheritage.net/index_page_stuff/following_trails/chief_joseph/chief_joseph_timeline.html; “General Miles,” available online as of November 13, 2012 at: http://www.ourheritage.net/index_page_stuff/following_trails/chief_joseph/9_Sept77/9_18_1877_Miles.html; “Good Words,” The West: Episode Six (1874-1877) Fight No More Forever. Transcript available online as of November 10, 2012 at: http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/program/episodes/six/goodwords.htm ↵

- “Good Words,” The West: Episode Six (1874-1877) Fight No More Forever. Transcript available online as of November 10, 2012 at: http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/program/episodes/six/goodwords.htm ↵

- Nerburn, Chief Joseph, 277. ↵

- “Chief Joseph,” The West. Available online as of November 13, 2012 at: http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/a_c/chiefjoseph.htm ↵

- “Good Words,” The West: Episode Six (1874-1877) Fight No More Forever. Transcript available online as of November 10, 2012 at: http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/program/episodes/six/goodwords.htm ↵

- “Good Words,” The West: Episode Six (1874-1877) Fight No More Forever. Transcript available online as of November 10, 2012 at: http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/program/episodes/six/goodwords.htm ↵