The American Tragedy at Wounded Knee

Around 2 AM on the morning of December 30, 1890, Major Albert Hartsuff entered the Episcopal Church at the Pine Ridge Indian Agency in South Dakota. A veteran army surgeon, Hartsuff had been treating wounded soldiers since seven the previous evening. The scene in the church caused the already exhausted Hartsuff to “grow pale and waver.” Sitting abruptly, he admitted to journalist Thomas Tibbles that “this is the first time I’ve seen a lot of women and children shot to pieces,” and, he added, “I can’t stand it.”[1]

Army wagons had brought 38 wounded Lakota women and children to the agency from Wounded Knee Creek, where earlier in the day a confrontation between the US Army and a band of Minneconjou Lakota had turned into a disaster. With the field hospital full of wounded soldiers and a handful of Lakota, the remaining 38 were left in wagons as night-time temperatures plummeted to well below freezing. Upon discovering the wagons, Reverend Charles Cook ordered that the wounded be brought into the church. Through the night Lakota agency physician Charles Eastman along with his future wife, Elaine Goodale, coordinated efforts to treat the petrified victims. Goodale later noted the irony of the scene, recalling that “joyous green garlands still wreathed the windows and doors, while the glowing cross in the stained-glass window behind the altar looked down in irony – or in compassion – upon the pagan children struck down in pagan flight.” Above the Lakota “pierced with bullets or terribly torn by pieces of shell, all sick with fear” a banner’s Christmas message, “Peace on earth, good will to men,” seemed out of place.[2]

The heart-wrenching scene at the agency proved to be only a small part of the devastation left by the events of December 29, 1890. While accounts detailing how the gunfire began paint a contradictory and confusing story, it is clear that after the first shots the US 7th Cavalry immediately overwhelmed the outnumbered, mostly unarmed Lakota and indiscriminately killed men, women and children.[3]

The Ghost Dance

During the 1880s well-intentioned but dangerously misguided reform efforts attempted to alleviate poverty and disillusionment on western Indian reservations. Working under the 1887 Dawes Severalty Act, the government began allotting sections of communally owned tribal lands to individuals and selling excess plots to white settlers. On the Great Sioux Reservation, already reduced in size after Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse had defeated General George Custer at the Little Big Horn in 1876, the government used dubious methods to convince the Lakota to take the first step in allotment. Over strong opposition, some Lakota signed an 1889 agreement that ceded half of their remaining land and created six smaller reservations: Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Crow Creek, Lower Brule, Pine Ridge and Rosebud (see map).[4]

The following winter, harsh conditions and reduced government rations brought widespread hunger and epidemic disease. But with the spring came a new hope. A delegation of Lakota had returned from a trip to Nevada, where they had met Wovoka, a Paiute prophet. Indians who believed in his message, and danced as he instructed, would be rewarded with the coming of an Indian messiah and the dawn of a new age. The vision promised the return of deceased friends and relatives, plains filled with buffalo, and that “there will be no white man to lay his hand on the bridle of the Indians’ horse.” When late summer droughts destroyed Lakota crops the Ghost Dance began to attract significant numbers of converts especially among the more traditional Lakota living on the Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Standing Rock and Crow Creek reservations. Although only a minority of Lakota adopted in the Ghost Dance religion, which preached peace and that its followers “must not hurt anyone,” the vision of a new world without white people startled some. Concern grew when Lakota dancers began wearing “ghost shirts” that they claimed could repel bullets.[5]

No one was more frightened than Daniel F. Royer, the newly appointed Indian Agent at the Pine Ridge Reservation. Royer was appointed for political reasons and completely unqualified for his post. While more experienced agents, military personnel and Christian Lakota all believed that the Ghost Dance would harmlessly run its course if left alone, Royer panicked. Journalist Tibbles recalled that the “new nervous, inexperienced agent promptly lost his head.” Within a week of his appointment in October 1890, Royer, whom the Lakota took to calling “Young Man Afraid of Indians,” informed Washington that he might need troops to keep order at Pine Ridge. On November 15 he wired the Commissioner of Indian Affairs: “Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy…the employees and government property at this agency have no protection and are at the mercy of these dancers.” The following day, after fleeing with his family for Rushville, Nebraska, he telegraphed General John R. Brooke: “Indians are wild and crazy over the Ghost Dance…We are at the mercy of these crazy demons. We need the military and we need them at once.” Additional alarmist messages flooded into Washington from the newly appointed Special Agent, E.B. Reynolds, at the adjacent Rosebud Reservation.[6]

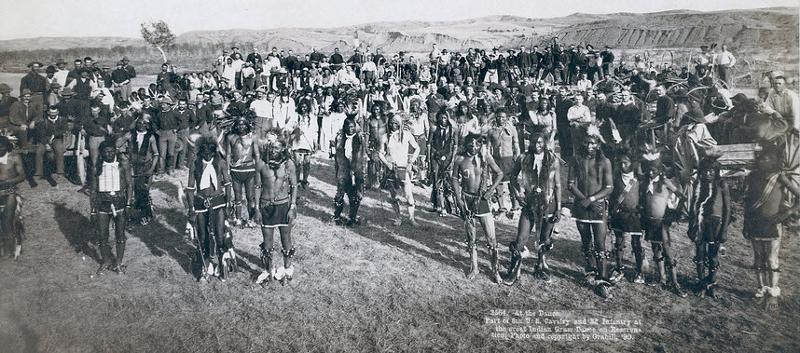

Responding to prodding from Washington, General Nelson A. Miles, Commander of the Division of the Missouri, reluctantly dispatched troops to Pine Ridge and Rosebud. The arrival of the first detachments of troops on November 20 threw the reservations into chaos. Some Lakota flocked to the agencies for protection, while others fled to join the Ghost Dancers. Settlers, who had mostly viewed the Ghost Dance as a curiosity, began to fear a Lakota attack and clamored for protection. Meanwhile, thousands of Ghost Dancers flocked to the badlands and congregated at the “Stronghold” in the northwest corner of the Pine Ridge Reservation.[7]

Spotted Elk

On December 15 the tense situation deteriorated further when Lakota police shot and killed Sitting Bull in a botched arrest attempt. Sitting Bull had fled to Canada after the Battle of the Little Big Horn but had returned to the Standing Rock reservation in 1883. While skeptical of the Ghost Dance, the Hunkpapa Lakota leader did not discourage his followers from dancing, and James McLaughlin, the Standing Rock Agent, blamed him for rising tensions. After the shooting, more than three dozen of Sitting Bull’s dismayed followers fled south to the Cheyenne River Reservation and joined Spotted Elk’s (often referred to as Big Foot) Minneconjou band. Big Foot was a strong voice in opposition to federal policy and had embraced the Ghost Dance message.[8]

Despite his outspoken opposition to government policy, Spotted Elk had a reputation as a calming voice and shrewd negotiator. When Red Cloud, the then-aged Oglala war hero living on the Pine Ridge Reservation, heard rumors that Spotted Elk was beginning to question the promise of the new religion, he invited the Minneconjou leader to Pine Ridge in hopes that he could help defuse the standoff. Spotted Elk accepted the invitation and set off with his band for Pine Ridge on December 22, 1890. Believing that the Minneconjou band was headed for the Stronghold, General Miles dispatched soldiers to intercept it. On December 28 Major Samuel M. Whitside and a detachment of the 7th Cavalry caught up to the band and found Spotted Elk stricken with pneumonia – bleeding from the nose and mouth, he was barely able to speak. After escorting the band to the cavalry encampment at Wounded Knee Creek, Whitside issued the hungry Lakota rations and called for reinforcements. [9]

Around 8:30 PM Colonel James Forsyth arrived with additional men and assumed command. Now, 470 well-armed troops (including a detachment of Lakota scouts) supported by four Hotchkiss guns capable of rapidly firing 1.6- caliber shrapnel-filled shells surrounded Spotted Elk’s band. The magnitude and firepower of the force sent to bring them in startled Spotted Elk’s band that just days earlier Lieutenant Colonel Edwin Sumner described as a “harmless lot, mostly women and children.” They numbered about 350 – 230 of whom were indeed women and children.[10]

The following morning news that the Ghost Dancers from the stronghold had agreed to come into the agency along with Spotted Elk’s capture brought relief – the crisis seemed at an end. Before escorting Spotted Elk’s band to Pine Ridge, however, Forsyth attempted to disarm the Lakota. A call to voluntarily turn over their weapons yielded only 25 guns and a call to search tepees, which produced an additional 38. Unsatisfied and growing impatient, Forsyth then ordered that the men submit to a body search. As Forsyth suspected, some of the young men were concealing guns under their blankets. The situation grew tense. With the men separated from the rest of the camp and surrounded by troops, several Lakota noticed soldiers loading their weapons. A medicine man began to dance and preach in Lakota. Some remember him reassuring the men clad in ghost shirts that the soldiers’ bullets would not harm them.[11]

Tragedy

As soldiers began disarming the young men, Black Coyote announced that he was not going to give up his gun – it was expensive, he had done nothing wrong and should not be forced to part with it. Soldiers grabbed Black Coyote and began wrestling the gun from his hands – it discharged into the air. After a second or two of indecision, officers ordered their troops to fire just as the few Lakota who still had guns dropped their blankets and fired in return. Within moments most of the Lakota men were struck down. By Forsyth’s count his troopers killed 82, including Spotted Elk, in the council area. Only about 20 men were able to flee back through the soldiers toward their families and join the handful of men who had not been at the council. Because Forsyth unwisely deployed his troops facing each other as they surrounded the council area, their initial volleys also accounted for most of their own casualties.[12]

As the wounded Lakota in the council area scrambled to acquire weapons from fallen soldiers and return sporadic fire, the rest retreated toward the women and children in the main Lakota camp. As they did, additional soldiers joined the fray and the four Hotchkiss guns began firing their explosive shells at a rate of 50 per minute. Journalist Will Kelley witnessed the carnage and wrote “soon the mounted troops were after them, shooting them down on every hand.” He added, “Just now it is impossible to state the exact number of dead Indians. There are many more than the number killed outright. The soldiers are shooting them down wherever found. No quarter given by anyone.” According to journalist Charley Allen, who himself was nearly killed by soldiers, “the boys of the Seventh Cavalry were too excited to think of anything but vengeance.” The handful of Lakota men led many of the remaining women and children to a ravine behind the camp and attempted to hold off the soldiers. Turning Hawk, a Minneconjuo Lakota, recalled, “those who escaped that first fire got into the ravine…they were pursued on both sides by the soldiers and shot down.”[13]

After the rifle and Hotchkiss fire subsided, Allen, who had witnessed young boys playing near the council prior to the firefight, recorded: “on reaching the corner green where the schoolboys had been so happy in their sports but a short time before, there was spread before me the saddest picture I had seen or was to see thereafter, for on that spot of their playful choice were scattered the prostrate bodies of all those fine Indian boys, cold in death… The gun-fire had blazed across their playground in a way that permitted no escape. They must have fallen like grass before the sickle.”[14]

Even after the officers called a cease-fire at the council grounds and in the ravine, the killing continued. Mounted troopers chased the fleeing Minneconjuos, in some cases up to three miles, and killed unarmed men, women and children. George Bartlett, a captain of the Lakota Police from Pine Ridge, witnessed five women followed by soldiers. As Bartlett explained, “they sat down on the hill and faced them and the soldiers killed all five of them. When they saw they were going to be slain they covered their faces with their blankets and awaited death.”[15]

Wounded Knee Aftermath

News of the slaughter at Wounded Knee threw the agency into further chaos. Ghost Dancers who were making their way toward the agency immediately reversed their course and fled north toward the Cheyenne River. Thousands of previously “peaceable” Pine Ridge Lakota, including Red Cloud, panicked and joined their relatives in flight – pushing their numbers to some 5,500. It took Miles, who arrived at Pine Ridge on December 31, over two weeks to convince the disaffected Lakota to return to their reservations. On January 15, 1891, the Lakota agreed to return after Miles provided assurances of a general clemency, increased rations and a chance to be heard in Washington. He also agreed to replace Royer and additional incompetent sub-agents with more trusted army officers.[16]

Cover Up

As the cavalry’s actions at Wounded Knee became clearer, Miles grew increasingly furious with Forsyth. Reacting to early newspaper accounts of the “battle,” the US Army Commander, General John Schofield, wired Miles congratulating “the brave 7th Cavalry for their splendid conduct.” Miles replied by informing Schofield that Forsyth’s actions “will undoubtedly be the subject of an investigation… the disposition of 400 soldiers and 4 pieces of artillery were fatally defective; large numbers of troops were killed and wounded by fire from their own ranks, and a very large number of women and children were killed.” The following day Schofield wrote Miles to hold the congratulations and make an inquiry into “the killing of women and children on Wounded Knee Creek.” On January 4th Miles relieved Forsyth and launched an investigation into his conduct.[17]

The soldiers suffered 25 killed and over three dozen wounded – mostly by their own hands. The death rate of the Lakota was much higher and more difficult to verify. Estimates suggest that the US Cavalry killed between 250-275 Lakota – mostly unarmed women and children. The inquiry Miles began went nowhere. Officers, soldiers, and pro-government Lakota scouts rallied around Forsyth and presented a tainted story that held the officers and the soldiers innocent and placed the blame on their Lakota victims. Ignoring Miles’s scathing commentary denouncing the findings of the inquiry, Schofield added his own cover letter telling the Secretary of War, Redfield Proctor, that the 7th showed “excellent forbearance” and that its conduct “was well worthy of commendation bestowed upon it by me in my first telegram after the engagement.” Proctor concurred and added that there was no evidence that any soldiers were killed by friendly fire and that “there is little doubt that the first killing of women and children was by this first fire of the Indians themselves.” Nearly a year later, Miles was still irate. In a private letter he called the Wounded Knee engagement a “wholesale massacre,” and wrote that he had “never heard of a more brutal, cold-blooded massacre than that at Wounded Knee. About two hundred women and children were killed and wounded; women with little children on their backs, and small children powder-burned by the men who killed them being so near as to burn the flesh and clothing with the powder of their guns, and nursing babes with five bullet holes though them.”[18]

Wounded Medals

In addition to praising the 7th Cavalry’s “splendid conduct” during the engagement at Wounded Knee, the U.S. Army also awarded 20 Medals of Honor to five officers and 15 enlisted men. While many carry rather generic citations such as “bravery in action,” or “distinguished gallantry,” some offered more specifics. Paul Weinert, for example, received his medal for “firing his howitzer at several Indians in the ravine.” The citation recounted that Weinert had “gallantly served his piece, after each fire advancing it to a better position.” While Weinert’s account tells of heavy fire coming from the ravine, more credible accounts paint a different picture – that of unarmed women and children attempting to escape while being protected by a handful of Lakota men with rifles. Historian Jerry Green concluded that by positioning his Hotchkiss gun “less than three hundred yards away, Weinert’s firing inflicted terrible damage, undoubtedly killing and wounding many women and children.”[19]

- Thomas Henry Tibbles, Buckskin and Blanket Days: Memoirs of a Friend of the Indians – Written in 1905 by Thomas Henry Tibbles. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1957), 323; Mary C. Gillett, The Army Medical Department 1865-1917. Army Historical Series, (Washington, DC: Center for Military History United States Army, 1995), 85 ↵

- Heather Cox Richardson, Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre. (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 275-76; Elaine Goodale Eastman, Sister of the Sioux: The Memoirs of Elaine Goodale Eastman, 1885-1891. Edited by Kay Graber (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 162, 161; Tibbles, Buckskin and Blanket Days, 321 ↵

- Richardson, Wounded Knee, 10-11; “Basic Chronology,” The Wounded Knee Museum. Available online as of October 26, 2013 at http://www.woundedkneemuseum.org/ ↵

- “Dawes Act,” Our Documents. Available online as of October 26, 2013 at: http://ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=50; Faragher, et al., Out of Many, 490-91; Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America. Revised Edition. (New York: Back Bay Books, 2008), 224; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 106; Risjord, Dakota, 158-65. ↵

- Risjord, Dakota, 166; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 118, 179; Goodale, Sister of the Sioux, 138-39; “Wovoka – Jack Wilson (c. 1856-1932)” New Perspectives on the West. PBS. Available online as of October 28, 2013 at: http://pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/s_z/wovoka.htm; William S.E. Coleman, Voices of Wounded Knee. (Lincoln, NE: The University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 9. ↵

- Tibbles, Buckskin and Blanket Days, 302; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 176, 178-80, 189, 195-96; Coleman, Voices of Wounded Knee, xxii, 88-89. ↵

- Risjord, Dakota, 167; Coleman, Voices of Wounded Knee, 45; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 209; Goodale, Sister of the Sioux, 151. ↵

- Risjord, Dakota, 167-69; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 173-74; “Like Grass Before the Sickle,” New Perspectives on the West, The West Episode Eight (1877 – 1914) ↵

- Risjord, Dakota, 168-69; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 173, 210. ↵

- Risjord, Dakota, 168-69; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 262; Coleman, Voices of Wounded Knee, 156. ↵

- Richardson, Wounded Knee, 267; Coleman, Voices of Wounded Knee, 289-95; Risjord, Dakota, 170. ↵

- Richardson, Wounded Knee, 267-71; Coleman, Voices of Wounded Knee, 295-301, 306; Risjord, Dakota, 170; Tibbles, Buckskin and Blanket Days, 311. ↵

- Richardson, Wounded Knee, 270, 273; Coleman, Voices of Wounded Knee, 312-13 ↵

- Richardson, Wounded Knee, 276; “Like Grass Before the Sickle,” New Perspectives on the West, The West Episode Eight (1877 – 1914) One Sky Above Us. ↵

- Richardson, Wounded Knee, 273-75. ↵

- Risjord, Dakota, 171-72; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 276, 282-83, 286. ↵

- Richardson, Wounded Knee, 275, 286. ↵

- Green, “The Medals of Wounded Knee,” 206; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 300. ↵

- Green, “The Medals of Wounded Knee,” 206; Richardson, Wounded Knee, 300. ↵