5 Lectures and Discussions

In the previous two chapters, you learned all about reading. Reading is a fundamental skill all college students need to master. It is essential– the same way learning to read music is essential to students who want to be music majors. However, there are other skills you need to master. You were already introduced to these ideas in chapter 2, but now we’ll get more in-depth. Remember the “warm up.” “work out,” “cool down” you learned about in the last chapter? That same process applies to other academic skills.

The purpose of this chapter is to help you master two other important skills: understanding and taking notes on lectures and participating in class discussions.

Learning Objectives

By the time you are done reading this chapter, you will have:

- An understanding of why lectures are so difficult to take notes on

- Strategies for keeping up during a lecture

- Strategies for understanding your instructor’s lecture goals

- Ideas about how to set up notebook page for lectures

- Suggestions about how to “process” your notes after the lecture

- An understanding of when and why your instructor might use discussions

- Strategies for “getting the most” out of a discussion

Set Yourself Up for Success in Lectures

In order to take effective notes, you have to understand why you should take them in the first place, then strategize to make notetaking work for you.

Students need to take notes because it is impossible for the human brain to remember all of the important concepts from a 50 – 80 minute lecture. Some students say “I get more out of lecture if I just sit and listen” but that is biologically impossible. The human brain is not wired to remember that much information at a sitting. Some students say, “I don’t need to write anything because the instructor gives us powerpoints.” While many instructors do this, the Power Points are rarely complete. Usually, they are just an outline. Other students say, “I just copy down what the instructor puts on the board.” This is a good start, but usually not enough. Often, the instructor writes an outline of the lecture on the board, but very few details.

Think of lecture notes like a second (or third) “book” for the class. You are writing it based on your understanding of your instructor’s lecture. You need to study it and use it just like you do your textbook and any other materials your instructor has assigned you.

Notetaking can be very low-tech. All you need is a notebook and a pen. Pencils tend to smear and fade so it is best not to use them. Have a separate notebook for each class. Do not take all your notes in one notebook—if you do, your math notes are jumbled up with your history notes and your English notes. If you prefer to take your notes on a device– great. Just have a system for saving each set of notes so you can clearly see what class they are from. Also, be very mindful of the status of your device. Make sure your device is charged before you leave for campus. Bring your charger and know where on campus you can plug it in. Make sure you get to class in plenty of time to turn on your computer, warm it up, open up a new document, etc. If any of these things are issues for you, pen and paper is a better bet.

Before you develop a notetaking system, you have to carefully think through what equipment you need. In chapter 1, you learned about getting organized. Use what you learned there to be organized for lectures.

Notetaking is Tough

Notetaking during lectures is hard. If you struggle with it, it isn’t because something is wrong with you—it is because it is hard. Here’s why:

It is a complex process. You have to listen to the lecture, figure out what is being said, decide what is important enough to write down, come up with a way to say it in your own words and write it down at the same time you are listening to the next idea the lecturer is saying.

It is hard to catch everything. You cannot re-start, back up or re-read if you get confused. Lectures are like trains—they keep going whether you are on them or not. While you can certainly stop the lecturer to ask questions, it is sometimes difficult to do so.

Every lecture is different. If you have a great note taking style for one lecture, it might not be the best one for the next lecture. It can be a challenge to continually adapt your note taking style to fit the lecture. Also, some instructors are great at helping you out by saying things like, “This is really important, so write it down.” Some instructors are more interesting than others and are better organized. Other instructors go off on tangents and drone on and on. All this variety can make it hard to take notes.

You probably already knew that taking notes in lecture is a complex process and that some lecturers are better than others. However, there is another reason why taking notes on lectures is hard. It is not a type of communication most people have much experience with.

Lectures are not organized the way most of your daily communication is, and it is important to recognize that. Most of the communication you do on a daily basis is heavily aimed toward achieving a goal you can act on or use to make a decision. This is “goal-oriented communication.” Your lectures, as a rule, are “concept-based communication.”

Goal-Oriented Communication

Goal-Oriented communication is designed to achieve a specific goal. This kind of communication relies heavily on details and facts, and, of course, achieving a goal. Here is a sample of Goal-Oriented communication:

Your car is making a funny noise so you call a mechanic. When the service representative answers the phone, you provide details about what the car is doing as well as its make and model. The service representative provides you with several days and times when a mechanic can see your car. This entire exchange depends on specific facts: what the car doing, how old it is, etc. Then, you need to remember what day and time you agreed to bring the car in.

You begin the conversation with a goal in mind– you want to make an appointment for your car. You end the conversation with that goal achieved– you now have an appointment for your car.

Concept-Based Communication

Concept-based communication is more complex—partly because it isn’t a skill you practice every day, but also because it is simply more complex. Of course, your instructor has a goal for their lecture– they want you to understand how something works, or why an event is important, etc. However, it is easy to lose that goal because lectures have many points, subpoints, and sub-sub points.

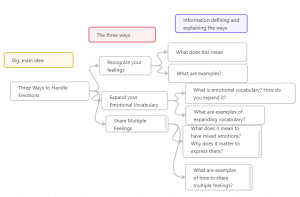

Let’s re-visit the example of the Communications lecture on healthy ways to handle emotions.

Your instructor says something in the beginning of class like “Today, we’re going to talk about healthy ways to handle emotions.” Then, she goes on to say, “There are three ways to handle your emotions in a healthy way. You can recognize your feelings, expand your emotional vocabulary and share multiple feelings.”

Now, the instructor goes back to the first point she made– you can recognize your feelings. She explains what recognizing feelings means, and gives examples of how to recognize them, and explains how and why this is healthy for people to do. Next, she moves on to major point number two: expand your emotional vocabulary and repeats the same process– she defines the idea, gives examples and explains why it matters. Finally, she moves on to point number three– sharing multiple feelings and goes through all the steps again.

A couple things are worth noting– first of all, in most everyday situations, people don’t usually go back to something they said 15 or 20 minutes ago and expand on it. If you and your friends are talking about how much fun you had at an event over the weekend, you usually will move on from that conversation and begin to talk about something else. Lectures are unique in the lecturer makes a point early in the lecture, but doesn’t get back to it for some minutes. The second thing worth noting is that some lecturers are great about saying something like “Okay, now I’m moving on to point two.” or even “Remember how I said we’d be talking about three ways to handle emotions? I just finished telling about one and now I’m moving on to two.” However, if the speaker doesn’t say anything to help you along, you might lose track of exactly where they are in the lecture.

By the time you instructor gets to the second main point “Expand your emotional vocabulary,” even a very good student might have forgotten that this is the second main point. By the time your instructor gets to the examples connected to main idea three it is likely minute 48 or 49 of the 60 minute lecture. It might be hard to see that “recognizing your feelings,” “expanding your emotional vocabulary” and “sharing multiple feelings” are three major ways to handle your emotions since so much time has elapsed and so many facts and ideas have been presented that you might struggle to see the connections and notice the overall idea— there are three ways to handle emotions in a healthy way.

Often, this confusion causes students to focus on the details in lectures–which makes sense since you have to focus on details in most other communication. For example, you need to remember the day and time you are supposed to bring your car in for repairs. The overall concept is that your car isn’t working properly, but without focusing on the details– when your appointment is– you can’t solve the big problem. Let’s say your instructor says, “60% of married couples end up in fights because their Emotional Vocabulary isn’t big enough.” (By the way, this “fact” is totally made up!) You jump on the statistic and write in your notes, “60% married couples fight—emotional vocab not big enough.” But your instructor doesn’t really care about the statistic—she’s using it to make the larger point—having a small emotional vocabulary causes problems.

What students often do when they listen to lecture is write down facts they find interesting, or the instructor has put on the board. Instead of seeing an overall picture and how those facts fit into it, they simply remember facts (I.e. That Archduke Ferdinand was killed in 1914—but not about why his death launched a World War.) The instructor, on the other hand, wants you to see how those facts make a larger point—expanding your emotional vocabulary can help you avoid conflicts or why Archduke Ferdinand’s assassination caused a war.

If you can figure out the entire goal of a lecture you have helped yourself decide what matters to write down and given yourself a framework for taking your notes.

Taking Notes on Lectures

Now that you know all the reasons why taking notes on a lecture is hard, (and that, if you find taking notes on lectures difficult that there is nothing wrong with you) you need to know what to do about it. The first step to making lectures easier to take notes on is to think about your instructor’s overall lecture type. Next, you need practical strategies for taking notes.

Understand Your Instructor’s Lecture Type

The first key to taking good notes in a lecture is understanding what type of lecture your instructor uses. Most lectures fall into one of three categories: hand-in-hand, jumping off point or combination.

Hand-in Hand Lectures

These lectures are right over the material in the books. They are called hand-in-hand since they “walk” side by side with the book—the material you read in the textbook is the same material you hear about in lecture. Usually, your instructor will give “hand in hand” lectures because they 1) believe the material in the book is difficult and needs further explanation or 2) because the information is REALLY important to learn and they want to make sure it makes sense to you.

If your instructor gives hand-in-hand lectures, they usually expect you to read the chapter before the lecture. Many students think the opposite is true– they think the instructor will tell them what they are supposed to “get out” of the chapter. If you realize that your instructor’s major lecture strategy is to give hand-in-hand lectures, the best thing you can do is make sure you come to class having read the material first.

Jumping Off Point Lectures

Jumping off Point lectures “jump off” from the book material. They bring in materials you cannot read about in the book—they may expand on ideas in the book or provide examples of concepts in it. Usually, instructors who give “jumping off point” lectures believe that students are responsible for reading and learning from the book. They feel it is their job to use their expertise to provide you with information that you cannot learn from the book. Often, these instructors believe the information in the book is a foundation their lectures will build on. They also believe you are responsible for the material they provide you in lecture and may test you on it.

Sometimes students hear a jumping off point lecture and say, “The instructor just talks and tells stories. The lecture has nothing to do with the book.” While you might have an instructor who just likes to talk, it is rarely true that the lectures have nothing to do with the book. If your instructor gives jumping off point lectures, they usually expect you to do several things on your own.

- Read all material ahead of time

- Make connections to the textbook material on your own

- Take good enough notes that you will be able to be tested on what you learn in lecture.

Think of it like this: your instructor doesn’t usually want to want to waste time just talking– they plan to use what you are learning in lectures in some way– usually on a test, or in a paper.

Combination Lectures

Some instructors will combine both Hand-in-hand and jumping off point lectures. Others will use one type of lecture for some chapters in a semester and another type for other chapters.

If this is your instructor’s strategy, some of the same advice applies: read materials ahead of time, assume you will be tested on what you learn in lecture and develop a notetaking system that is complete enough that you will be able to understand the material when you review it.

How to Make Lectures Easier to Understand and Take Notes on

Now that you know all the reasons why notetaking is hard, and you have an understanding of what type of lectures are common in college classes, now it is time to think about developing a manageable notetaking system.

The first step in doing that is to recognize what is NOT part of a good notetaking system!

Neatness and spelling. If you hope to take complete notes, you can’t also have great penmanship and perfect grammar and spelling. You’ll need to abbreviate, use arrows, leave words out of sentences, etc.

Complete sentences. Some students think good notetaking means writing down the instructor’s words exactly as they said them. This is impossible. You will need to come up with a way to re-write, in a much shorter way, what the instructor has said.

So what IS part of a good notetaking system? Remember how your reading notes, whatever style you choose, should have four types of information? The same is true of your lecture notes. In case you forgot the four types of information, here is a review, but adapted for lectures:

Structure notes: These notes are very simple—they help you determine VERY QUICKLY when you took the notes and what they are about. Writing “October 12” in the upper right-hand corner of your notes is a structure note. Just below it, if you wrote something like, “How clouds are formed,” or “The process of perception” or “Characteristics of Romantic Literature” then you have made a quick note for yourself so that, at a glance, you know the subject of that day’s lecture notes. Doing this makes studying for tests easier.

Terms/dates/facts notes: These notes are just what they sound like– they are terms and definitions, important dates, statistics (i.e. “60% of people think XYZ”) and facts. (i.e. who won an election, who wrote a book, who developed a particular theory). Your instructor often writes these things on the board.

Concept notes: After your instructor writes a term, date or fact on the board, they will often spend a few minutes talking about it. In that time, they usually explain why the term, date or fact matters. You need to write this down as well. These are concept notes– they help you understand things like WHY you need to know the terms, facts and dates your instructor wrote down. (Remember Archduke Ferdinand? The important idea here is not the date he was assassinated, but how and why his assassination led to World War I— that important stuff often comes from your instructor’s mouth but doesn’t get written on the board).

Relational notes: Remember relational notes from chapter 3? You need them again when you write lecture notes. As a matter of fact, they are vital to understanding your notes. Just as with reading, these notes can take many forms– single words, numbers, arrows or simple drawings. Often, your instructor will say something that will help you with relational notes. For example, if you are in a communications class and your instructor says, “Today we are going to talk about three ways to express emotions in a healthy way,” you should note that, by the end of the class, you should have three ways to express emotions.

Warm Up, Work Out, Cool Down for Lectures

You already know about Warm Ups, Work Outs and Cool Downs for reading. The same basic idea applies to lectures. A successful student warms up before a lecture, works out during a lecture and then cools down afterwards. This chapter section breaks down how you warm up, work out and cool down for lectures.

You already know about Warm Ups, Work Outs and Cool Downs for reading. The same basic idea applies to lectures. A successful student warms up before a lecture, works out during a lecture and then cools down afterwards. This chapter section breaks down how you warm up, work out and cool down for lectures.

Warming Up for Lectures

Warming up for lectures has two parts. Part one takes place at home, and part two takes place at the beginning of the lecture.

Part 1: Before Lecture, Decide What’s Coming Up

Re-read the notes you took the last time the class met and see if you can make an educated guess about the next lecture. For example, in your Business class you are learning about several ways to set up a business. On Tuesday, your instructor got through the first two. It is reasonable to assume that, on Thursday, you will go over the remining way. It is also likely your instructor will provide you with basically the same information about each way to set up a business– for example, they will begin with a definition of each way, and follow that with pros and cons.

Use past experience to help you decide what’s coming up. If your instructor has been lecturing step by step over the book, (hand in hand lecture) it is safe to assume he will cover the next section of the book. If your instructor likes jumping-off-point lectures, it is safe to assume she will give another one.

Once you know what’s coming up, you can make decisions about how to organize your notes pages in your notebook. (More on that later).

Part 2: Use the First Minutes of Class to Decide How to Organize Notes

Are you a fan of crime drama? Ever notice if you miss the first few minutes of your show—the part where the crime happens, you spend the rest of the show somewhat confused? Same deal with your classes. If students miss class time, it is often at the beginning. They figure missing the first five minutes of class can’t hurt too much, right? One very important thing often happens in the first 3-5 minutes of class, and if you miss it, you will be lost.

Often instructors spend the first 3-5 minutes saying things like, “Today we are going to . . . . and next time class meets, I expect you to . . . .”. If you miss that, you miss important organizational information.

Use your instructor’s opening remarks to help you organize your notes. Here are sample opening remarks and some decisions you can make about how to take notes:

| If your instructor says something like . . . . | Then you should recognize that. . . |

| “Today, we are going to discuss three artists who were central to 18th Century American Art.” | There are going to be three major parts to the lecture– you should make sure to clearly mark each artist. |

| “Understanding how blood moves through the body is tricky because there is a lot to remember.” | By lecture’s end, you should have a sense of a process– in this case, how blood moves in the body. Whenever you need to understand a process, numbers can help. (i.e. step 1 is . . . . step 2 is . . . .) |

| “There are many reasons why people in lower socioeconomic groups have worse health outcomes.” | Your instructor will list, explain and describe a series of reasons. By lecture’s end, you should have a clear list of reasons. |

| “There are major differences (or similarities) between A and B . . . .” | Your notes need to make it clear how two or more things are similar and/or different. Make those similarities and differences clear in your notes. |

| “Today, you are going to learn how (event, person, concept) caused X, Y and Z to happen | Your notes need to make it clear how a person, event, etc. caused a series of things to happen, and why that is important. |

Working Out for Lectures

There are many ways to take effective notes. Some students love the Cornell method, others like to write things down in the order in which they heard them. Others like to use outlines or mind maps. Whatever method you choose, your notetaking system must have three features:

- It must allow you to clearly record main ideas from a lecture

- It must be “sustainable.” It is impossible to write down every word your instructor says. Therefore, you need to develop a method of taking notes that allows you to record a great deal of information quickly—this may involve developing a series of abbreviations, using symbols or creating an outline. Note taking strategies that require you to write out full sentences, spell all words correctly and record every idea are not sustainable because you will quickly fall behind.

- It must produce reviewable notes. The notes you take during a lecture are supposed to be like a second textbook for your class. They are useless if you cannot use them to study for exams or do other assignments for the class. Your notes need to be legible, and have enough information that, when you go back, you can make sense of what you wrote.

Here are general tips for creating a sustainable system:

Abbreviate

Most classes have jargon you can abbreviate. In an American Government class, for example, the word “Government” will be used a great deal. In an Earth Science class, long words like “environment” or “Photosynthesis” might be used regularly. Abbreviate them—“gov,” “env” and “Phsyn” will be much easier for you to write quickly. If you are worried you will forget what your abbreviations mean, make a glossary at the top of your page or reserve a page at the beginning of your notebook for abbreviations.

Abbreviate common concepts. For examples, instructors may say that something has increased or decreased, improved, or gotten worse etc. Use an arrow up or an arrow down to represent that idea. You can the arrow up or down in any class.

Use mathematical symbols to represent ideas like “added,” or “lost,” “divided” or “multiplied.” For example the concept:

“The Governor needed five more Congress members’ votes in order to pass the bill” might show up like this in your notes:

“Gov need 5 + cong member to pass bill.”

NOTE: Spend a few minutes of your outside-class study time thinking up abbreviations. Your mind is too focused on what and how to write when you are actually IN the lecture. Students will often say abbreviating is a bad idea since they won’t be able to say what the abbreviations stand for. Again, if you decide ahead of a lecture what abbreviations mean what, make a glossary.

Listen for Transitions

Most instructors give you some warning when they are about to move on to another topic. Learn to pay attention to how your instructor’s transition. Here are some clues:

Some will stop a lecture and ask if there are questions about what they just said. Often, that is a cue that they are moving on to another topic.

Others will cue the class by saying something like “The second important point . . . .” This tells you that the instructor is moving on. In your notes, write “2nd important point . . .”

Sometimes instructors will “change gears” by warning you that something is different than something else. For example, if a Biology teacher is talking about deciduous trees and wants to shift to talking about evergreen trees, she might say something like, “Evergreen trees are different from deciduous trees in several important ways . . . .” In your notes, write something like “Evgn diff from decid trees ‘cuz .. . .”

Instructors will sometimes write lecture outlines on the board—make sure to use them! However, many students make the mistake of writing down only what the instructor puts on the board. Usually, this simply isn’t enough. Taking more thorough notes is necessary.

Catch Up

Even really great notetakers get behind during a lecture. Probably, the best thing to do is “catch up” to whatever the lecturer is doing right now. If you are trying to recall stuff they said five minutes ago, you miss what is happening right now and then you get even farther behind.

Cooling Down After the Lecture

Many students take notes and don’t to review them until the day before a test— if you do this, you will likely not understand much of what you wrote. Notes need to be studied several times a week, and you need a system for doing so.

The notes you take are like another book for your class. You need to use them like you would a book, which means that your notes have to have some of the same qualities a book does. As you already have learned, you can’t write an entire, well-organized book while you are sitting in class—you have to make it a point to work with your notes as part of your homework routine.

Step 1: Organize Your Notebook

Look over the notes you took that day and do two things (if you haven’t already)

- In the upper right corner of the page (or left, if you prefer) write the date

- Across the top of the page, maybe in a different color pen, write a sentence or phrase that sums up that lecture’s main point. Something like, “Healthy ways to express emotions” or “The four kinds of volcanos” or “Reasons why World War 1 started” will be good enough. You just want to be able to tell later what that day’s lecture was about so it is easier to study for exams. (Also, if you are not able to come up with a short phrase or sentence that sums up the lecture, you might need a tutor, or a visit to your instructor!)

Step 2: Process Your Notes

Many students say they “look over” or “review” their notes. But what does that even mean? How to you know you have done a good job “looking over” your notes?

A better way to think about it is you need to process your notes. What does it mean to “process” your notes? While there are a number of ways to do that, here is a simple one: In class, leave part of your notebook page blank so you can write on it later. The easiest way to do this is to create an extra wide left margin. While in class, take your notes on the right side of the page and leave the left side for “Processing space.”

Use that blank portion of the page to process your notes. Below are 12 ideas about how you can process your notes during a homework session. Read them and decide which suggestions you’d like to try. Combine several suggestions if you’d like. You might even use different techniques for different kinds of classes.

- Note your confusion. Write a symbol (a question mark is a good one!) in the processing space to indicate what you are confused about. Write a question if you have one. Also, it might help to write down how you hope to resolve your confusion—i.e. ask in class, see a tutor, etc.

- Get the Big Picture. In the chapter on reading, you learned 6 graphic organizers. Use the processing space to draw a graphic organizer. For example, if the goal of the lecture was to explain how blood moves through the heart, make a timeline graphic that sums up that process.

- Mark where there is missing information. It is easy to miss something during a lecture. If, during the lecture on how blood flows through the heart, you realize you seemed to have missed step three, add it in the processing space.

- Add additional notes of explanation. After lecture, go through your notes and ask yourself, “If I lost these notes and found them again in 10 days, would they make sense to me? If not, what do I need to add?” Use the processing space to make those additions.

- Anchor random facts to a concept. Let’s say you are in Astronomy and your instructor lectures about atoms. You have the term “ground state” in your notes but you don’t remember what it is or how it connects. Use the processing space to define the term and note why it is important.

- Develop a symbol system. In the processing space, write symbols to mark different kinds of information. Below are suggestions of symbols and what to mark:

- If your instructor defines something, write “DEF” in the margins.

- If your instructor uses an example to make an important point, write “EX” in the margin and explain why/ how that example was used—what point did that example make?

- If you remember that something causes something else, make that clear—in the margins write X caused Y—draw arrows, etc.

- If knowing what people did what is important (i.e. in a History or Art History class), draw a stick figure in the margin with the person’s name under it.

- Use colors. Using colored pens during a lecture isn’t a good idea. For example, let’s say you decide all definitions will be in purple, important people will be in red, while all dates will be orange. You need to remember that during the lecture and be ready to grab the right color when you need it. That’s too much to hold in your brain while you are trying to make sense of the lecture. But AFTER lecture, colors can be great tools, as long as you decide ahead of time what the colors mean. For example, you can highlight main ideas in blue, examples in pink, subpoints in green and definitions in purple.

- Write your own headings and subheadings. You know that textbooks use headings and subheadings. Make your own headings and subheadings using different colored pen and/or highlighters. For example, if your instructor is lecturing over major outcomes of the Civil Rights Act go back to your notes and write “Major outcomes of Civil Rights Movement” in the processing space. Write each outcome in the processing space next to the place in your notes where you wrote about it. For example, write “Ending segregation” in the margin next to the notes you took on ending segregation.

- Mark important notes about upcoming assignment or exams. Sometimes, in the lecture, your instructor will say something like “This is a good example of the kind of thing you can write your paper about.” Or “You’re going to have to know the difference between X and Y for the exam.” Come up with a certain symbol to mark that kind of stuff—like an exclamation point.

- Make connections between other course materials and the lecture. If you notice your instructor talks about a psychological experiment that was also mentioned in the book, note that in the processing space. You can draw a link symbol and/or say something like “This is also in Chapter 8.”

- Note ideas for projects or papers. If you know you have a paper coming up in Art History and you have to choose an artist and explain how their work fits into an art movement, and your instructor says something in lecture that helps you decide what you want to include in your paper, mark it with a special symbol so you don’t lose your idea.

- Tab your notes. As you get closer to a big exam or paper, make tabs for your notes. Buy tabs at office supply stores or make your own out of masking tape or sticky notes.

Step 3: Put the Lecture into the Bigger Picture

Each lecture is a small part of the class, but you still need to know how it fits into the goals of the course. Think of it like this: your little toe is very small, but not unimportant. If you injure it, you will quickly find out how much you rely on it for balance. One lecture is the same way. It might be a small part of the course, but it matters, so you need to put the work in to figure out why your instructor gave it.

- Ask yourself why your instructor decided to lecture over this material in the way they did. What type of lecture is it? Hand-in-hand or jumping-off-point? Why do you suppose they chose to deliver that type of lecture to the class today? How does the lecture relate to other course materials you have to read for the course?

- Make sure you understood the lecture itself. When you review, pretend you need to tell a classmate who missed the lecture what the main ideas were. Actually explain the notes—either out loud or silently.

- Share notes with a classmate. What did he or she write down? How is it different from what you wrote down? What can you add to one another’s notes?

Start Today . . . Get Ready for Lectures

The chart below gives suggestions about how to prepare for and use lectures– starting now.

| Warm up | Look over the notes you took in class the last time it met. See if there are clues about what today’s lecture might be about.

Decide whether previous lectures have been hand-in-hand, jumping off point or a combination. Ask yourself why your instructor is choosing this type of lecture.

|

| Work Out | Take notes during the lecture. Make sure you go beyond simply copying what is on the board. This chapter is full of tips about how to make this easier.

|

| Cool Down | Review your notes within 24 hours. Make sure you understand what you wrote and think through how it applies to the other things you are learning in the class. |

Set Yourself Up for Success in Class Discussions

Discussion is a big part of college instruction. Most instructors use discussion in their class at least a few times during the semester, so it is important to understand their purpose. Many students have a negative opinion about discussion because they believe important information and learning can only come from the instructor, so what students have to say isn’t really that important. Some students even get mad when their instructor has discussions—they believe that instructors have them when they want a “day off” since, on discussion days, students do most of the “work.”

Since an instructor’s attention cannot be everywhere, some students use discussion time to text friends and family, have side conversations or do homework for another class. Some may think that, since their classmates are not experts, what difference does it make what they have to say?

However, your instructor has discussions for specific purposes. There are three types of discussions. They are:

Concept Check Discussion- The purpose of concept check discussions is to give students opportunities to practice discussing challenging concepts. The act of putting unfamiliar terms and concepts into your own words causes you to clarify your thinking and deepen your understanding. Listening to someone else describe a concept is less likely to lead to deep understanding than having to talk about it yourself. Think about it like this— If you want to learn to swim, you must actually swim. You can learn a little bit by listening to someone talk about swimming, or watching other people swim, but you cannot learn to swim until you put on a bathing suit and jump in the water.

Instructors have concept check discussion because they want to see what the class does and doesn’t understand– usually so they can address it with further explanation. They want to know what you think about what you are learning. They will often use the discussion time to say, “You’ve got this right, but the part you are missing is . . . .” or “Wait, I better go over that concept again . . . . .”

Task Focused Discussion—The purpose of a Task Focused discussion is to complete a task—usually one that will help you with an upcoming test or assignment. Sometimes, task-focused discussions are with the whole class, but often the instructor will break the class up into small groups. An instructor might ask you to brainstorm topics for an upcoming paper or think up examples to illustrate an important concept. He or she might ask you to summarize a reading, pick out main ideas or develop a time-line that will help you understand an important process or a significant series of events. In a math or science class, you might be asked to solve problems and use formulas.

Instructors have Task Focused Discussions because they 1) want to reduce stress by giving you a chance in class to prepare for an upcoming assignment or test 2) They want to see if you can do something they’ve been teaching you to do– which will help them decide what future classes and lectures might focus on. 3) The want to give you an opportunity to try a task while they and other students are around to help. This is one step to getting you ready to do it on your own.

Workshop- Workshops focus on evaluating another student’s work. You may be asked to read and comment on one another’s essays or compare and contrast how you approached a problem. (They are different from task-focused discussions because task focused discussions because workshops focus on evaluating student work as opposed to testing the class’s understanding of concepts). Students are often hostile to workshops because they feel they are grading one another’s work—which is the instructor’s job, not theirs. They may think, “I barely understand this myself, why should I have to comment on someone else’s work?” They may say “Only the instructor’s opinion matters since they give the grade. Who cares what my classmates think?” However, your instructor sees workshops very differently.

Usually, instructors have workshops to help students develop judgment about what is and is not effective work. This is a first step in being able to do something yourself with confidence. For example, if you are learning about effective thesis statements, your instructor may want to see if you can read other students’ papers and recognize when a good thesis statement and one that needs more work. The idea behind a workshop is that, if you can recognize what is good and what needs work about a classmate’s thesis, you will leave class better able to write a good thesis statement next time you have to do it. Also, when the semester ends, you need to be able to use whatever you learned to help you with other classes you take later. You learn to write papers in composition so you can write an academic essay on your own for that sociology class you are taking the following semester. Workshops provide you with practice being independent and using your new skills while your instructor is still nearby to help you if you get confused.

Understanding What Your Instructor (Probably) Means by “Discussion”

Sometimes, there is miscommunication between instructors and students about what a discussion or a workshop is. Your instructor might say something like, “On Friday, we will discuss chapter five.” In most cases, this is what your instructor expects: you will have read chapter five by class time, you will have a good understanding of the concepts, you will attend class with questions. But students sometimes assume that they will be told what they need to know about chapter five during class on Friday, so reading the chapter ahead of time isn’t necessary. When students come to class without having read, they get confused quickly since the instructor is discussing terms and ideas they have not heard.

Similarly, an instructor might say something like “On Monday, we will have a workshop over your papers” or “We will go over the problems at the end of chapter three.” Usually, your instructor expects you to come to class with your papers written and your problems completed to the best of your ability. They hope you will ask questions about what you did not understand or that you will review other students’ work. Sometimes, students hear “workshop” or “discussion” and they think “study hall.” They expect they will have the hour to work on their homework for the class– and so they come to class with nothing done.

In college, you won’t often get class time to do homework. Since classes only meet two or three times a week, instructors generally expect you to do homework outside class.

Think about It . . . .Getting the Most Out of Discussions

When instructors expect students to participate in a workshop over a paper or discuss a chapter, but a student comes to class without having completed the work, sometimes the student concludes that discussion days are a waste of time. The truth is that there is nothing wrong with the lesson– the problem is that the student is unprepared.

If a hockey player showed up for practice with no skates or pads, they would have to sit on the bench and watch everyone else practice. Practice will go on with the players that did show up prepared. This doesn’t mean the practice itself is a waste of time or ineffective. It means that it was a waste of time for the player who did not show up prepared. The same is true for your classes—if you show up prepared, you will get more out of class.

Warm Up, Work Out Cool Down for Discussions

Just as with reading college materials and listening to lectures, there is also a warm up, a work out and cool down to do for discussions.

Just as with reading college materials and listening to lectures, there is also a warm up, a work out and cool down to do for discussions.

Warming up for Discussion

Sometimes, you will come to class and be surprised you are having a discussion, but if you know ahead of time you are going to have one, warm Warming up can be pretty simple. Do one or all of the following:

- Make sure you read all the materials assigned.

- Think ahead of time about what discussion type best seems to fit your class and instructor. Do you think you will have a concept check discussion, a task focused discussion or a workshop?

- If you are going to workshop or discuss a paper, problem set, etc. make sure you do it to the best of your ability ahead of time.

- Come with questions. Discussions are usually designed to let students and instructors interact, so take advantage of that time to ask for clarification.

- Accept that you are at least partially responsible for “getting something out of” a discussion. Come prepared to participate.

Working Out During a Discussion

If you know you are going to have a discussion or workshop, think ahead of time about its purpose. If you can figure out if the discussion is a concept check discussion, a task focused discussion or a workshop, that will affect how you work out.

Working Out During a Concept Check Discussion

Your instructor has concept check discussions because they want to give you practice talking about important ideas. That often means one of two things:

- Your instructor believes the material you are covering is essential to the class and you will benefit from an opportunity to ask questions and discuss ideas with others. Their goal is that you will leave class with a good understanding of whatever was the subject of the discussion. They want you to have this solid understanding because it will be important later—the concepts you cover in that discussion will be essential to understanding the rest of the class.

- Your instructor wants you to be able to discuss certain ideas in your own words or develop your own opinion about some part of the subject matter. Your instructor rarely does this randomly—they want you to be able to discuss certain ideas in your own words or develop your own opinions about them in order to prepare you for something you will do down the road such as write a paper, take an essay test or give a speech.

To get the most out of a concept check discussion, ask yourself: “What concepts and ideas seem to be really important to my instructor in this discussion? How confident am I that I understand these concepts? Do I understand this concept well enough to discuss it in my own words? Have I developed my own opinions about this concept?”

Finally, find out what you have to do with the information you are learning. Will you have to write a paper? Take an essay test? Give a speech? You can often look at a course schedule or the syllabus to find out. If you can’t find anything there, ask your instructor directly what assignments are coming up and how the discussion relates to that assignment.

Working Out During a Task Focused Discussion

Your instructor has task focused discussions when they want to give you an opportunity to master a skill you will need to be successful in the class or give you an opportunity to accomplish a task that will have a direct influence on an assignment you will need to do later. Often task focused discussion happen in small groups of 3 to 5.

To work out during a task focused discussion, ask yourself, “Why is this skill important to master?” or “How will this task we are working on help me with the assignment, tests, etc. we will have down the road?”

Also, actually participate during the discussion. It is tempting to allow the other students to do the work, particularly if it seems they know more than you do. However, if it matters to your success in the class that you master particular skills, ask yourself, “Do I really understand this?” Make every effort to truly understand the task you are being asked to do. Make every effort to understand why your instructor would like you to do that task and how it relates to upcoming assignments, papers or tests.

Working Out During a Workshop

Your instructor has a workshop when they want you to provide feedback to other students in the class on something they have done—like a paper or an art project. Of course, you will also receive feedback from other students. Your instructor has these kinds of discussions because they want to give you opportunities to practice skills you have learned in the class so you will slowly but surely be able to do these things on your own.

The question to ask yourself during an Evaluation discussion is, “What specific skills is this workshop designed to teach me? Have I mastered those skills well enough to be able to apply them to my own work and the work of other students?”

Think about It . . . The Need for Speed

Speed is great when it comes to lots of things– internet connections, getting through the drive-through at your favorite restaurant, running a race. But speed is not great in discussions– especially task focused discussions and workshops.

When instructors break students into groups to complete a task, there is always a group that finishes quickly. They sit, scrolling on their phones, claiming to be “done” when the instructor checks on their progress. If your group finishes first, question your work very carefully. You probably missed something.

Ask the instructor to be sure– remember, this is your time to develop skills.

Cooling Down After a Discussion

A cool down for a discussion is fairly straightforward. When you are doing your homework for the class later on, ask yourself these questions:

“What did my instructor want us to get out of today’s discussion?” Jot down all the answers you could think of. You might say “My instructor wants us to learn how supply-demand graphs work” or “My instructor wants to know how well we understood cell division.”

Next ask yourself, “How will the concepts I learned in this discussion help me achieve future goals in the class?” Again, jot down your answers. You might say “My instructor wants us to learn how supply-demand graphs work because we will have to do them on the exam in two weeks.”

Finally, ask yourself how confident you are that you understand not only why you had this sort of discussion, but if you mastered the skills or concepts you were working with.

Start Today . . . .Get Ready for Discussions

The chart gives suggestions about how to get ready for discussions . . . starting now.

| Warm Up | Warming up for a discussion can be difficult if you don’t know you will have one until you arrive in class. If you do know ahead of time, prepare by making sure your homework and readings are done as thoroughly as possible. In your notebook, jot down what you think the purpose of the discussion will be and what you would like to get out it. For example, if you know you will be discussing a particular type of math problem, jot down what confuses you about it. You can also prepare questions ahead of time. |

| Work Out | To work out in a discussion is to devote your full energy to understanding the purpose of the discussion and doing what your instructor is asking of you. It also means listening carefully to classmates and committing to the idea of saying something yourself.

|

| Cool Down | To cool down after a discussion is to think carefully about which of the three purposes (or which combination of purposes) your discussion served. Ask yourself “What was I supposed to get out of this discussion?” Answering that question will help you determine what you instructor thinks is important.

|