2 The Four Basic Principles of Academic Success

College will take two to four years to complete. Along the way, you will have different kinds of classes, and each will require different skills. Every instructor will have different expectations and goals for you. While you are a student, you may change majors, fail a class or surprise yourself when you realize you have a passion for a subject you never thought would interest you. Even though you will be confronted with a whole range of classes, learning situations, types of tests and types of professors, there are skills you can learn that will help you be successful in all academic situations.

Just as actors in a musical need to be good at singing, dancing and acting in order to put on a good show, you need to be able to study effectively, manage time, and read well. This chapter will give you a basic overview of each of these skills so you can develop a sense of what goes into being a successful student. Later chapters will provide you with an in-depth look at these skills along with practical suggestions about how to make your study sessions as productive as possible.

Learning Objectives

By the time you are done with the chapter, you will know:

- The “body rules,” or how to work within your brain and body’s limitations so you can make better study choices and maximize your ability to remember what you learn

- The basics of time management for college success

- Strategies for making it easier to remember what you read

- How to use course structure and course components to make good guesses about what might show up on exams

Principle 1: The Body Rules

If you’re going to be a successful student, you have to make study choices that maximize your brain’s ability to remember and minimize your chances of forgetting what you read and hear. To do this, you have to have a basic understanding of how your brain and body work (and don’t work together). That is what you will learn in the chapter.

Why does an hour of lecture seem like an eternity, but an hour of movie watching flies by? Why can you work a four or five hour shift without getting particularly bored or tired, but you’ll doze off if you attempt four or five hours of homework?

The answer lies in our biology. People first learn through their senses—babies learn by seeing, tasting or touching everything that comes their way. And babies are also highly emotional. When they spill a glass of juice, they cry. They don’t say, “Gee, no big deal. There’s more in the ‘fridge.” When we grow up, even though we get much more sophisticated, we still feel the most comfortable dealing with information we can make sense of using our five senses or our emotions. When you come home after a long day of school or work and you want to relax for an hour or two before ore going to bed, you’re much more likely to want to watch reruns of your favorite shows than a physics lecture. You may think to yourself, “I don’t want to think that hard.”

Most popular television shows deal with falling in love, family relationships, or conflicts with employers. We can relate to these stories because of our own human experience, and so they hold our attention. Our senses are happy, too—TV shows allow us to both see and hear what’s going on, and, as a general rule, the more senses involved in an activity the less likely it is to be boring. This is why you never doze off playing a sport or doing yard work—all your senses are being used to do the task at hand. When you read, your body is still. You use only your eyes and your brain, so chances of falling asleep go way up.

College classes, unlike most of the rest of your life, force you to rely on your intellect—which, since you don’t use it as often as you do your senses and emotions, is a bit like an under-developed muscle. It tires easily. Your intellect comes into play when you have to learn abstract ideas like patriotism, democracy, self-esteem, globalization and cultural understanding. Your senses don’t help you make understand these ideas because you can’t picture them, hear them or touch them. Trees, cars, computers and music are much easier for your brain to process.

If you want to strengthen your intellect, you need to know how to maximize your brain’s ability to learn, remember and make connections between important ideas. The body rules explain how to treat your brain so it is more likely to work well and less likely to tire out.

Body Rule 1: The Twenty-Four Hour Rule

Unless you make an effort to use information, you forget much of it within 24 hours. Your brain is an efficient house-keeper. After about 24 hours, your brain sorts through new information you’ve taken in and puts it in one of two places: the “garbage can” or your long-term memory. Information moves to long-term memory if you use it frequently or it makes a big impression—you would remember the time your science teacher set the classroom curtains on fire with a Bunsen burner, but you might not remember the point of the lesson. To combat your brain’s instinct to “throw out” what you learned, review notes and reading within 24 hours and again later in the week so your brain gets the message that this stuff needs to move into long-term memory.

Body Rule 2: Seven to Nine Concepts Rule

Your brain can “hold” 7-9 new concepts at a time. Brains are like potted plants. If you continue to pour water into a potted plant once it is saturated, the water will simply spill over the edges of the pot, where it will do the plant no good. Any gardener knows that it is better to water plants in small amounts over the course of time—once the appropriate amount of water is utilized and absorbed, more can be added. Students who choose to read a 30-page chapter at one sitting set themselves up for failure since the human brain simply isn’t wired to learn all those concepts at once. Break up difficult reading into small sections of 5-8 pages to make it less likely you will have to learn more than your brain can hold at once. Novels and some kinds of essay reading can be exceptions to this rule, but most textbooks need to be digested in smaller bites.

Body Rule 3: The Sleep Schedule Rule

Bodies like routine. But some students have sleep schedule that vary widely—some nights they go to bed at 10 pm while others they stay up until 2 am studying, or working. If you keep this kind of schedule, you give yourself jet-lag, and you will have the fatigue and “out of it” feelings associated with that problem. Bodies like to release hormones, digestive juices, etc. on a specific schedule. When you alter your schedule a great deal in the course of a week, your body gets confused and tired.

Body Rule 4: Twenty-minute Attention Span

After 20 minutes of doing one activity, most adults’ minds will wander. This doesn’t mean that you can only study for 20 minutes a day—it means that you have to think of your brain like a muscle. When you study, alter your activities. For example, if you have to read a chapter, read for about 20 minutes, then stop to summarize what you read. Stopping to write or talk will rest your “reading muscles” so they will be ready to tackle new reading.

Body Rule 5: Forgetfulness Rule

You will forget 40-60% of what you read or hear unless you make a special effort to remember it, or the new information is closely related to information you already know. For example, you will easily understand how to play a new type of poker game if you already know how to play poker. If you are brand new to Art History, you may have a tough time remembering much about classical architecture unless you take notes and review them. Students resist taking notes because they believe they have exceptional memories, but chances are they don’t—and unless they take notes and review them, they will remember only enough to pass an exam with a D.

Principle 2: Time Management

Time management is discussed first because all other skills depend on your ability to manage time. Unless you devote an appropriate amount of time to reading, reviewing, and preparing for tests, you will always struggle academically.

Time management is discussed first because all other skills depend on your ability to manage time. Unless you devote an appropriate amount of time to reading, reviewing, and preparing for tests, you will always struggle academically.

Time management is more than just making sure you get to your classes on time. It involves setting priorities, disciplining yourself to study even when you’d rather be doing something else, and learning to juggle your personal activities (everything from going away for the weekend to scheduling a haircut) with your studies so you can be a well-rounded student. More than anything, managing time requires commitment. There is a lot to say about time management, and more will be covered later. Right now, the essential thing to know about time management is to how to create a schedule with adequate time devoted to homework.

Daily/ Weekly Planning

If you are like most college students, you have a job, take a full-time course load and participate in a club or two. Some students are married with families. All these activities and obligations make for a hectic schedule! Managing time is essential for students.

Step 1: Changing Your Perception of “Free Time”

Most students don’t have any trouble putting their classes, meetings and work hours into a calendar. The hard part is scheduling study times. First-year students, if they came to college right after high school, are used to having their time scheduled for them. They started classes at 9, finished at 3:30, and then went to after school practices, rehearsals or meetings. At home maybe their parents scheduled dinner and evening study times. At work, many employees show up on time and then the boss decides what they will do when. Many students begin their college career having never managed time before.

It is a new concept for many students to schedule study time during their “free time.” Most students perceive their “free time” (when they have nothing formal scheduled) as time they could use to study, or do something else—socialize, play with their children, check social media.

In addition to being new at time management, college students also must battle human nature. Human nature makes time management difficult as well. People tend to be “path of least resistance” creatures—in other words, if they don’t feel there is something they have to do, they usually will do what is fun or easy. Homework isn’t fun or easy for most students, so they put it off.

The solution to this is planning. If you look at your schedule and realize you have from 2-4 off each afternoon, set it aside as study time, not free time. Just as you schedule your shift at work, or time to get together with friends, you need to make time to study. Without a study schedule, students often socialize or watch videos when they ought to be studying.

Step 2: Knowing the “Rule”

The rule for college success is to spend two hours studying outside class for every hour you spend inside.

Many students are surprised when they find out how much time it takes to be an effective student. Many first-year students earned good grades in high school without having to study more than an hour or two a night. Many students, if they spent 20 minutes on homework a night and earned C’s in high school think they will certainly earn B’s if not A’s if they increase their study time to 30 minutes a night. They are shocked when they fail their first assignments. Many students earn low grades simply because they do not study enough.

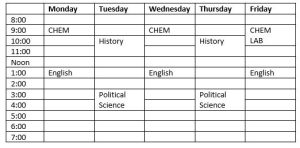

The first step in time management is to analyze your schedule to figure out exactly how many hours you can expect to spend “hitting the books.” If you are a full-time college student, you likely are taking about 12 credits. Your schedule might look like a lot like Carlos’. He has:

- Chemistry from 9:00-9:50 on Mondays and Wednesdays and a Chem lab on Fridays from 9:00-10:30

- English from 1:00-1:50 on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

- History from 10:00-11:50 on Tuesdays and Thursdays

- Political Science from 2:00-3:50 on Tuesdays and Thursdays

If Carlos wrote his schedule out on a weekly planner, it would look like the calendar below:

Carlos’ Schedule

Carlos’ Monday-Wednesday-Friday classes are 50 minutes each and he has two of them. That means each Monday, Wednesday and Friday he spends 100 minutes in class plus his Chem lab. By the end of the week, that is a total of 390 minutes spent in classes.

His Tuesday-Thursday classes are each 100 minutes long. He has two of them as well, meaning that he spends 200 minutes in class every Tuesday and Thursday. By the end of the week, that equals 400 minutes.

If he adds his Monday, Wednesday, Friday classes to his Tuesday, Thursday classes, he spends a grand total of 790 minutes in classes. If he divides 790 by 60 to translate from minutes to hours, he discovers that he spends a little over 13 hours in class each week.

There are 168 hours in a week. Thirteen is 8% of 168. That means he spends only 8% of each week in class. That doesn’t sound like much!

However, if he follows the college rule and studies two hours outside class for every hour inside class, he needs to plan roughly 26 hours of studying each week. If he adds 26 and 13, he comes up with 39 hours—very close to a full-time job.

You will find it helpful to calculate how many hours you should ideally spend studying each week, and how many hours you actually are studying. Some classes will require much more than two hours a day, and others will require less, but you should always plan to spend twice as much time studying as you do in class.

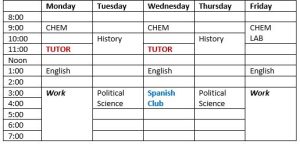

The Balancing Act

The previous schedule only included Carlos’ classes, but most students need to juggle extra-curricular activities and jobs into their schedules. Here are other things Carlos needs to add to his schedule:

- A Chemistry Tutor appointment On Mondays and Wednesdays at 11:00

- Spanish club on Wednesdays from 3:00-5:00

- Work on Mondays and Fridays from 3:00-7:00

if he added these things to his calendar, it would begin to get a bit fuller. See the calendar below:

When he adds his classes, work, tutoring and Spanish Club hours up, it totals 51 hours. This schedule doesn’t include time to do laundry, grocery shop, socialize or study. As activities and personal chores begin to add up, it becomes clear that Carlos has to plan if he’s going to get everything in, or he will perpetually be running behind. Of course, this particular schedule doesn’t include the weekends, which might be set aside for doing homework, running errands, etc.

Carlos chooses to study between his classes on Mondays and Wednesdays and right away in the morning on Tuesdays and Thursdays. He adds study time before work, Saturday morning and Sunday afternoon. By the time he is done squeezing in homework time, he has found 21 hours during the week for homework.

Here is the schedule with possible study times and the weekend added:

If Carlos treats the times labeled “homework” the same way he would appointments, then his study time will work into his schedule just like all his other activities. Will Carlos need this much time? Maybe some weeks he will. It is better to have the time set aside then not to have the time, but then need it.

One important thing Carlos is doing is using the time between classes, even though it is only an hour. Many students like to wait until they have a longer block of time but take advantage of those shorter time blocks in your day. If you have to read a 300- page novel for English class, and you manage to read 30 pages during an hour you have between classes, you have just completed 10% of that work. If you have 20 math problems to do and manage to complete 3 in your one-hour break, that’s not a bad start.

Step 3: Making a Commitment

When you have an appointment with a friend or are expected at work, someone else is counting on you to show up. People keep their obligations to others because they don’t want to risk ending a friendship or losing a job. When you make an appointment with yourself to study, you may not feel the same obligation to follow through on your plan. You might go to the gym, play video games or spend hours watching funny cat videos. One key to time management is being willing to commit to your studies, even if it means giving up fun activities. There is no magic way for you to keep yourself on a schedule other than sheer determination, but here are some suggestions that might help:

- Find a study partner and make study dates. Pick someone who will respect your need to study instead of socialize.

- Schedule your fun times. It is easier to do something difficult if you know you will get a chance to do something fun later.

- If you just can’t help yourself and you wind up spending study time having fun, carefully plan how you will make up that time later.

Start Today . . . Manage Your Time for Success

The best things you can do today to begin managing your time successfully are:

- Assess which the body rules you are following. Depending on your life, it might be impossible for you to follow all of them, but follow as many as you can.

- Make a calendar that not only has your work hours, the hours you spend in class and any weekly things you do– your work hours, meetings with friends, etc. but also the hours you plan to study.

- Accept that you will not always stick to your plan.

Think about “Free Time”

Many students resist planning their time because:

- Planning restricts them too much

- Something unexpected happens and they get off track

- They are waiting until they feel like studying

Here are the counter arguments:

“But planning is too restrictive . . . .”

Students at the University of Minnesota, Morris who agreed to fill out Time Management Worksheets almost all agreed that it reduced stress and made them feel more free. Why? When they planned ahead, they became much more aware of test and due dates. Nothing “snuck up” on them anymore. They stopped having those panicky moments when they realized something was due in a few hours and they hadn’t started it.

“But something unexpected will happen . . . “

You may sit down to study only to have a loved one come home upset and needing to talk. A family member may need a ride to the hospital, or you might put in extra hours at work. Unless you are a machine, you will get off track—it is part of being human. However, if you planned to write your English paper between 1 and 3 and you wind up babysitting your niece during that time, you know what you need to make up.

“But I’m not in the mood . . .”

Don’t ever wait for moods. Successful people work almost every day at their sport, art or job. If your hairdresser, doctor or professor only showed up for work when they wanted to they’d get fired. Part of being mature is doing things you don’t want to do because you have to in order to achieve your dreams. Besides, when you work daily at something, inspiration is more likely to strike because you have the material constantly in your mind. Just as a runner is more likely to beat her fastest time in a race if she practices daily and stays in shape, you are more likely to have sudden inspiration during tests or assignments if you stay on top of the reading. Besides, how realistic is it that you’ll ever truly be in the mood to study classical rhetoric? Or Anatomy and Physiology? If you want the grades, you have to put in the time.

Principle 3: Reading for Content

Reading is likely the first academic skill you learned. If you are like most American students, you learned to read in kindergarten, but didn’t learn how to take notes on lectures, study for tests and write papers until years later. Because most students can barely remember a time when they were not able to read, they assume they must be pretty good at it. After all, they have had years of practice.

So why do students often make comments like, “I know I read it, but I can’t remember anything!” or “When I go to review the chapter, it seems as though I have never seen this stuff before in my life.”

The reality is that many college students struggle to pick out main ideas and figure out what they need to know for their exams. One of the most common reasons for struggling is that students try to learn too much at one time, and forget what they learn as a result.

Chapter 4 will go over reading, but there are simple changes you can make to your study routine today. Keep reading.

The Problem

Have you ever been introduced to a good-sized group of people you have never met before? Often, someone will say, after everyone has said their name, “Okay, now there is going to be a test.” People laugh because everyone understands that it is very difficult for most people to learn 15 or 20 names after hearing them once. If you were to have a test on those names, it is likely you would “fail.” Brain research shows that most people can only hold 7-9 “items” in short term memory at once. Even though you realize how hard it is to learn twenty names, you might be trying to do the academic equivalent of that each time you study.

Many students, if they have a test over two chapters in Psychology on Friday, will sit down to read the chapters for the first time on the Wednesday or Thursday just before the test. If it is difficult or impossible for most students to remember 20 names after one introduction, how can they expect to commit several dozen concepts to memory in a matter of a few hours?

The human brain is not wired to study the same subject for four or five hours at a stretch, nor is it wired to learn page after page of material in one sitting. Remember the potted plant analogy from earlier in this chapter? When you water a plant, you can only pour until the soil in the pot is saturated. Once the soil is holding as much water as it can, water will drain out the bottom or flow over the rim of the pot—where it will do the plant no good. Once the plant begins to use the water, the soil will dry out again and be ready to absorb more.

Your mind works like the potted plant and potting soil. If you continually dump terms, dates, names and places into your head without giving them a chance to “sink in” your head will overflow before the information is absorbed.

The Solution

The first thing to do when you receive a new reading assignment is break it up so you are reading 6-10 textbook pages for each class each day. (Novels and short stories don’t really count here— they require different reading skills.) In other words, if you are assigned a 35-page chapter and you have 8 days to read it, read about 5 pages each day. There are a number of reasons breaking up reading is effective.

- It divides a long task into a shorter, more pleasant one. If you hate washing dishes, you may grumble a lot less about having to do them if you do them daily. Spending ten minutes a day doing dishes may be preferable to letting them build up until washing them will take two hours. Psychologically, it is usually easier to tackle tasks you don’t like if they are short. The same is true for reading. If you know you only need to pay attention long enough to get through five pages, that seems less daunting than having to slog your way through a 30 page chapter.

- It makes it more likely you will remember what you read. As already mentioned, you tend to learn concepts more thoroughly if you have fewer of them to learn at a time. When you break up reading, you divide the number of concepts you need to learn into a manageable number, which makes it more likely you will remember what you are learning. (Imagine the large group scenario again. If you met two people on Monday and had a chance to really get to know them, and you met two more people on Tuesday and two more again on Wednesday, it is more likely that, by Friday, you’d remember the names of everyone you’d met so far.)

- It might help you keep up with the lectures. Reading a little bit each day is also effective because most professors lecture over the chapter, and if you’ve read what they are going to lecture over before you attend class, you will be that much more familiar with the new terms and concepts the professor will talk about. You will get more out of the lecture if you have read the material ahead of time. Instructors generally expect their students to have read the material prior to the lecture.

Start Today . . . Improve Your Reading Comprehension

A study conducted at the University of Minnesota, Morris revealed that reading a little bit each day is a habit successful students have. A group of students in an introductory Psychology class were interviewed about study habits. Each week, the class had to read a chapter, and the average length of each chapter was about 35 pages. ALL A band and B students reported that they read 6 to 7 pages of the chapter a day.

The best thing you can do to improve your reading today is to divide your reading into smaller chunks and avoid “marathon” reading.

Tip: Most students underestimate the amount of time it takes to read well. To get a more accurate idea of how long it will take you to read a chapter, to this:

- Set your watch or phone for 20 minutes.

- Read carefully enough to understand.

- When your phone or watch beeps, stop reading.

- Count the pages you read. Multiply by 3 to see how many you can read in an hour.

- Use that information to figure out how long it will take you to finish all the reading.

Principle 4: Understanding Course Structure and Exams

It is possible for students to read well, take lots of notes during lecture, attend class every day, carefully plan out their study sessions and still struggle in class. It is vital to have all the skills previously discussed in this chapter, but there is one more skill you must have if your classes are really going to “click” for you.

You must have the ability to analyze course structure and determine what your instructor hopes students will learn from the course.

Course Goals

Even though most students would argue that classes aren’t much fun, it is helpful to compare a class to a party. People have parties to celebrate specific occasions, such as birthdays or anniversaries. Typically, the person hosting the party makes decisions about decorations and food based on the theme of the party. If you and your friends decide to throw a surprise birthday party for your cousin who loves Hawaii, you may choose to have a tropical theme, complete with tiki torches and pineapple smoothies. All decisions about decorations, attire, food and activities ultimately are decided by the Hawaii theme.

Even though most students would argue that classes aren’t much fun, it is helpful to compare a class to a party. People have parties to celebrate specific occasions, such as birthdays or anniversaries. Typically, the person hosting the party makes decisions about decorations and food based on the theme of the party. If you and your friends decide to throw a surprise birthday party for your cousin who loves Hawaii, you may choose to have a tropical theme, complete with tiki torches and pineapple smoothies. All decisions about decorations, attire, food and activities ultimately are decided by the Hawaii theme.

Like a party planner, your professor often starts with a theme, or a goal for the course. Goals can include learning specific knowledge (such how trade changed medieval Europe) or developing an approach to information you can use in many settings (such as how to analyze a speech in a communications class). Some classes have both kinds of goals.

If your Political Science professor wants you to become skilled at seeing how the media manipulates voters, they will select class readings and activities to enhance that theme. Most instructors have a paragraph or two in their syllabus describing what they hope students will be able to do once they complete the course. If you haven’t already, read your syllabus and look for a section entitled “Course Objectives,” “Course Overview,” or something similar. Carefully examine this part of the syllabus for clues about course goals.

Course Goals Make Homework Easier

Having a theme makes both parties and classes easier. When you go to the grocery store to buy paper cups for your Hawaiian party, you will walk right past the ones with snowmen, flowers or birthday candles on them. Instead, you’ll zero in on the paper cups decorated with palm trees. You don’t need to spend time agonizing over the decision because the theme you’ve chosen makes the decision for you.

Just as a party’s theme determines the decorations and food choices, the course goals determine the course structure. Course structure includes the decisions your professor makes about the class. How often are tests? What format will they have? Is the class lecture based or discussion based? Instructors select books, materials, and assignments based on the goals they set for the course. If you clearly understand the course goals, it will be much easier for you to understand the course components—which are anything you need to read, watch, listen to or do to acquire the information you need for your class. Your textbook, the lecture, lab activities, other reading, in-class films, speakers, etc. are all course components.

If we go back to the Political Science example– if you are reading an article on media ethics and you know your professor wants you to understand how the media manipulates the public, you will know that you need to take notes on anything the author says about manipulating people. Rather than spending precious time and energy wondering why you are reading the article, what you are supposed to “get out” of it, and what to take notes on, you can focus instead on how the article fits into the themes of the course and take notes that relate to the theme.

Class Structure Examined

While there are exceptions to every rule, it is often possible to determine what your tests will be like by looking at the course structure. The way your professors structure their courses is a big clue about what is valuable and important to them, and typically, what is valuable and important will turn up on tests.

There are many ways to design a course, but here are some of the most common ways, and an analysis of them.

Lecture Classes

Does the professor do the bulk of the talking? Many classes have this format, with some brief breaks for student questions. There are essentially two types of lectures:

Hand-in-hand lecturing occurs when the professor essentially explains the book. These lectures don’t usually introduce new ideas or terms. Usually, a professor’s purpose in having lectures of this type is to make sure you understand what you are reading, give you an opportunity to ask questions about the material and high-light the most important ideas for you.

Jumping off point lectures have a very different purpose and can be harder for students to follow. These lectures delve deeply into a topic that may have been mentioned only briefly in your textbook. Professors usually give this type of lecture when they want you to have a deeper understanding of a topic than the book provides. Textbooks usually cover a wide range of topics without exploring any one topic in great depth. Often, they simply report, leaving the opinionated arguments to other books. Professors sometimes use their lectures to add spice to the topic. Sometimes, they give this type of lecture as a way to showcase a particular person, place or idea that is significant to the discipline. Sometimes, they want to present points of view that may be different from, or may conflict with, those in the textbook.

For example, your Art History text book might mention Vincent Van Gogh, where he lived and what his most famous paintings were, but your professor may spend a day lecturing about Van Gogh’s role in the art community, how his early work was received and what place he holds today as an artist. Some professors may alternate types of lectures, depending on the topic, but usually lectures will fall into one of these two categories. Once you know what sort of lecture your professor tends to give, it will be easier to know what to take notes on.

Discussion Classes

If your instructor sets aside time each week for discussion, they value giving you an opportunity to develop and express your own opinions about the subject matter. Many students dislike discussion because they don’t like being put “on the spot” or talking in front of others. Some students think “I can’t discuss this. I barely understand it!” Other students think instructors have discussions when they don’t feel like planning a lecture. However, instructors use discussions for specific purposes. We will dive deeper into the purposes of lectures and how to prepare for them in chapter five, but for now, it is important to think about the role of discussion in your classes. They are listed below:

Concept Check Discussion– The purpose of concept check discussions is to give students opportunities to practice discussing challenging concepts. The act of putting unfamiliar terms and concepts into your own words causes you to clarify your thinking and deepen your understanding. Listening to someone else describe a concept is less likely to lead to deep understanding than having to talk about it yourself. Think about it like this— If you want to learn to swim, you must swim. You can learn a little bit by listening to someone talk about swimming, or watching other people swim, but you really cannot learn to swim until you put on a bathing suit and jump in the water.

Task Focused Discussion—The purpose of a task focused discussion is to complete a task—usually one that will help you with an upcoming test or assignment. Sometimes, task focused discussion are with the whole class, but sometimes the instructor will break the class up into small groups. An instructor might ask you to brainstorm topics for an upcoming paper, or think up examples to illustrate an important concept. He or she might ask you to summarize a reading, pick out main ideas or develop a time-line that will help you understand an important process or a significant series of events. In a math or science class, you might solve problems.

Workshops– A workshop focuses on evaluating another student’s work. You may be asked to read and comment on one another’s essays, or you may be asked to compare and contrast how you approached a specific problem or question. Usually, the purpose of a workshop is to help students develop judgment about what is and is not effective work to you can apply it to your own work. Workshops provide you with practice being independent and using your new skills while your instructor is still nearby to help you.

Usually, professors who teach using discussion sessions are comfortable when students disagree with them and one another. They value opinions and want to create an interactive classroom environment, often because they think it will be more interesting than lecture. In these classes, it is likely that you will have essay tests that require you to write about and defend your opinions. If you have multiple-choice tests in these classes, they are likely to be sophisticated questions that require you to connect ideas, themes and subjects in order to answer them successfully.

Relationships between Course Components

While it may seem like it sometimes, your instructor doesn’t make haphazard, spur of the moment decisions about what you should read, write or listen to for the class. Course components all have a relationship. Here are some possibilities:

Practical Application—you may be assigned reading that will show you how a particular idea works in “real life.” For example, if you are studying mental health, you may be assigned a novel whose central character suffers from depression. If you are reading about the role of art in community identity, you may be assigned an article on an annual art festival in a small town. These readings bring the ideas and concepts you are learning about “to life.” Test questions may ask you to describe what terms or concepts you saw reflected in these “real life” readings.

Compare and Contrast—Your professor may want you to understand that there are many perspectives on an issue. They may assign you articles or books that feature different perspectives on the same topic. Your instructor’s purpose is to get you to understand the complexity of an issue and formulate your own opinions about it. If your Art History professor assigned you five articles that provide five definitions of art, you conclude that they want you to think about how different people, or groups of people define art. Chances are that you may, at some point, be asked to compare and contrast those definitions, or come up with your own. Otherwise, why spend so much time and energy making sure you understand that there are so many ways to define art?

Close-Up Example—Sometimes your professor will cover a huge, broad topic in class, but they will want you to understand this topic in terms of a few specific examples. If you are studying racial tensions in the United States, you will quickly learn that racial problems occur in all parts of this country. But simply reading statistics about discrepancies in wages, health care and education may not give you the picture your professor wants you to have. They may assign you a book about how one particular town dealt with racism over the last few decades and how the racial climate has changed over time.

Course Components Analyzed

Below you will see how two students, Nick and Shaina, analyzed course components for a Psychology class and a Sociology class.

In Nick’s Psychology class, he has to read a textbook, watch videos that get into depth about concepts he’s already read about, and he needs to listen to lectures that also focus on explaining concepts that are introduced in the book.

If Nick were to analyze the course components his class, this is what he might conclude:

| Course Component | Description of Components | Nick’s Conclusions |

| Textbook | All major concepts come from here. | The instructor wants us to read the book to get the basics of major concepts. |

| Videos | Hand-in-hand with the book | Videos cover the same concepts the book does. Our instructor usually says something like, “This concept is complex, but this video is good at making it easier to understand,” so I can conclude it is important to learn these concepts. |

| Lectures | Hand-in-hand with the book | In her lectures, she goes over the book, but gets more in-depth and talks about research. It seems she really wants us to get the basics from the book and more detail from the lecture. |

Shaina is taking a Sociology class. Here are here course components: a textbook, some articles off the internet and a weekly discussion. Below are Shaina’s conclusions:

| Course Component | Description | Shaina’s Conclusions |

| Textbook | All major concepts come from the book. | We should read the book before we come to class or read the articles since the ideas we learn in the articles are based off of the information in the book. |

| Articles | Practical Application | The articles take an idea from the book and show how it works in the real world. We read about norms in the book, and then we read an article about what happens when marriage norms changed in a society. |

| Discussions | Confusion reducing and concept check | In our discussions she invites us to ask questions, but she also gives us scenarios and wants us to apply sociological concepts, so she is using them to make sure we understand the concepts. |

Start Today . . . . Figure out the Roles of Each Course Component

If you want to be a better student today, think about your course components. A course component is anything you need to read, watch or listen to as part of the course.

Use the chart below. List your course components in the left column. In the middle column, use the information in this chapter to describe each component. Finally, write down conclusions about why your instructor has chosen that course component. If you aren’t sure why you are doing something in your class, ask your instructor or a tutor.

| Course Component | Description | Conclusions |

Anything a student must read, watch, listen to or do in order to acquire the information they need for their class.