Emergency Preparedness, Response, and Recovery

Ernstmeyer & Christman- Nursing Mental Health and Community Concepts- OpenRN

A disaster is defined as a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to hazardous events interacting with conditions of exposure, vulnerability, and capacity that lead to human, material, economic, and environmental losses and impacts.[1] Every community must prepare to respond to disasters that include natural events (e.g., tornadoes, hurricanes, floods, wildfires, earthquakes, or disease outbreaks), man-made events (e.g., harmful chemical spills, mass shootings, or terrorist attacks), or infectious disease outbreaks. See Figure 18.2[2] for an image of the effects of the natural disaster Hurricane Katrina.

Emergency preparedness is the planning process focused on avoiding or reducing the risks and hazards resulting from a disaster to optimize population health and safety. Disaster management refers to the integration of emergency response plans throughout the life cycle of a disaster event. Because disasters cause physical and psychological effects in a community, emergency preparedness and disaster management emphasize collaboration and cooperative aid among health care institutions and community agencies to ensure a coordinated and effective response.[3]

Read the American Nurses Association resource regarding Disaster Preparedness.

Emergency preparedness and disaster management are based on four key concepts: preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery. This process guides decision-making when an emergency or disaster occurs in a community.[4] After the disaster event has concluded, evaluation of the effectiveness of the response occurs as part of planning emergency preparedness. See Figure 18.3[5] for a diagram that illustrates this theoretical framework for emergency preparedness. Each of these concepts is further discussed in the following subsections.

Preparedness

Preparedness includes planning, training personnel, and providing educational activities regarding potential disastrous events. Planning includes evaluating environmental risks and social vulnerabilities of a community. Environmental risk refers to the probability and consequences of an unwanted accident in the environment in which community members live, work, or play. Risk assessment also includes assessing social vulnerabilities that affect community resilience.[6]

Social vulnerability refers to the characteristics of a person or a community that affect their capacity to anticipate, confront, repair, and recover from the effects of a disaster.[7] Populations living in a disaster-stricken area are not affected equally. Many factors can weaken community members’ ability to respond to disasters, including poverty, lack of access to transportation, and crowded housing. Evidence indicates that those living in poverty are more vulnerable at all stages of a catastrophic event, as are racial and ethnic minorities, children, elderly, and disabled people.[8] Socially vulnerable communities are more likely to experience higher rates of mortality, morbidity, and property destruction and are less likely to fully recover in the wake of a disaster compared to communities that are less socially vulnerable. Community health nurses must plan emergency responses to disasters that address these social vulnerabilities to decrease human suffering and financial loss.

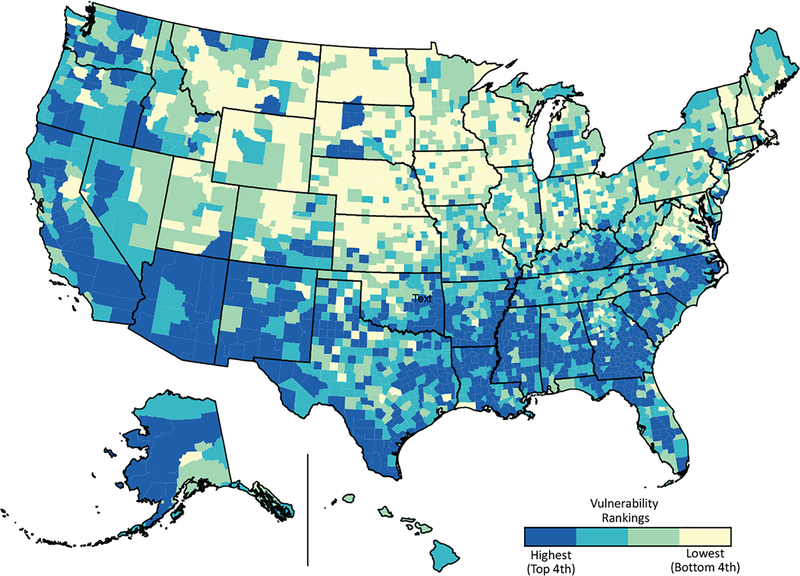

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) created a Social Vulnerability Index database and mapping tool designed to assist state, local, and tribal disaster management officials in identifying the locations of their most socially vulnerable populations. Geographic patterns of social vulnerabilities can be used in all phases of emergency preparedness and disaster management. See Figure 18.4[9] for an image of social vulnerability mapping.

Mitigation

Mitigation refers to actions taken to prevent or reduce the cause, impact, and consequences of disasters. Health care institutions and community health agencies plan three Cs to mitigate the effects of a disaster:

- Communication: An emergency communication plan identifies tools, resources, teams, and strategies to ensure effective actions during emergencies.

- Coordination: Coordination plays a crucial role in efficiency and effectiveness of disaster management by providing a big picture of an emergency and reducing uncertainty levels among responders.

- Collaboration: Collaboration allows responders to act together smoothly and helps reduce impact of the disaster.

Response

The response phase occurs in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. When a disaster occurs, actions are taken to save lives, treat injuries, and minimize the effect of the disaster. Immediate needs are addressed, such as medical treatment, shelter, food, and water, as well as psychological support of survivors. Personal safety and well-being in an emergency and the duration of the response phase depend on the level of a community’s preparedness. Examples of response activities include implementing disaster response plans, conducting search and rescue missions, and taking actions to protect oneself, family members, pets, and other community members.[10]

While the immediate actions of responding to a disaster are treating physical injuries, psychological effects must be addressed as well. To minimize psychological effects, nurses and first responders can provide support to victims of the disaster by following these tips from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)[11]:

- Promote safety: Ensure basic needs are met and provide simple instructions about how to receive these basic needs.

- Promote calm: Listen to people express their feelings and provide empathy and compassion even if they are angry, upset, or acting out. Offer objective information about the situation and efforts being made to help those affected by the disaster.

- Promote connectedness: Help people connect with friends, family members, and other loved ones. Keep families and family units together as best as possible, especially by keeping children with those whom they feel safe.

- Promote self-efficacy: Give suggestions about how people can help themselves and guide them toward the resources available. Encourage families and individuals to help meet their own needs.

- Promote help and hope: Know what services available and direct people are to those services and continue to update people about what is being done. When people are worried or scared, remind them that help is on the way.

Disaster Response Protocols

When thinking about responding to a disaster, first responders and emergency personnel come to mind such as law enforcement, fire departments, and emergency medical technicians (EMTs). However, nurses are also called upon to assist in emergencies or disasters and must be competent in responding. Nurses may be involved in triaging individuals for treatment.

To respond effectively when a disaster occurs, emergency responders perform triage by prioritizing treatment for individuals affected by the disaster or emergency. Field triage sorts victims affected by the event and ranks victims based on the severity of their symptoms. Disaster triage determines the severity of injuries suffered by victims and then systematically distributes them to local health care facilities based on their severity.

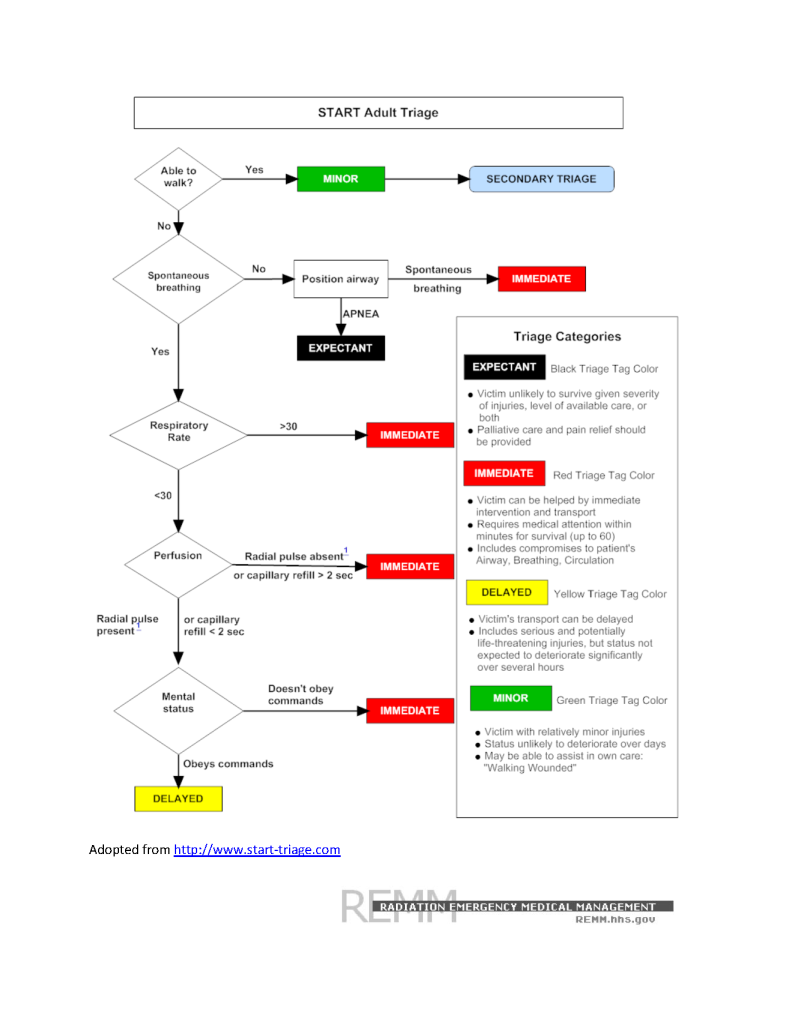

Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) is an example of a triage system established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that prioritizes treatment of victims by using standard colors indicating the severity of symptoms and prognosis. See Figure 18.5[12] for the START algorithm. The following colors indicate severity of injury and prognosis:

- RED: Emergent needs

- Life-threatening needs, such as alterations in airway, breathing, and circulation; impairment in neurological systems; or severe, life-threatening injuries.

- They may have less than 60 minutes to survive.

- These patients will be seen first or immediately.

- YELLOW: Urgent, but delayed needs

- Life-threatening needs; status is not anticipated to change quickly or significantly in the next hours, so transport can be delayed.

- GREEN: Non-urgent needs, often referred to as the “walking wounded”

- Minor injuries; status is not likely to deteriorate over the next several days.

- Many individuals can assist with obtaining their own care.

- BLACK: The person has died or is expected to die soon

- This person is unlikely to survive given the severity of their injuries, level of available care, or both.

- Palliative care and pain relief should be provided.

Providing Care for Those Exposed to Environmental Hazards

Nurses may be involved in caring for clients who have been exposed to chemicals or other environmental hazards. See Table 18.3 for assessment findings and interventions for a variety of exposures. Chelation therapy is a treatment indicated for heavy metal poisoning such as mercury, arsenic, and lead. Chelators are medications that bind to the metals in the bloodstream to increase urinary excretion of the substance.

Some chemical exposures require decontamination to treat the individual, as well as to protect others around them, including first responders, nurses, and other patients. Decontamination is any process that removes or neutralizes a chemical hazard on or in the patient to prevent or mitigate adverse health effects to the patient; protect emergency first responders, health care facility first receivers, and other patients from secondary contamination; and reduce the potential for secondary contamination of response and health care infrastructure. For example, if a farmer enters a rural hospital’s emergency department after chemical exposure to an insecticide spray, decontamination may be required. See Figure 18.6[13] for an image of decontamination.

The decision to decontaminate an individual should take into account a combination of these key indicators[14]:

- Signs and symptoms of exposure displayed by the patient

- Visible evidence of contamination on the patient’s skin or clothing

- Proximity of the patient to the location of the chemical release

- Contamination detected on the patient using appropriate detection technology

- The chemical and its properties

- Request by the patient for decontamination, even if contamination is unlikely

Table 18.3 Assessment Findings and Interventions for Exposure to Various Environmental Hazards

| Chemical or Hazard | Assessment Findings | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) Poisoning

(Auto exhaust and improperly vented or malfunctioning furnaces or fuel-burning devices)[15] |

Primarily decreased mental status from confusion to coma

May have cherry-red appearance of the lips and skin *Note: Pulse oximetry does not reflect accurate oxygenation levels because CO binds to hemoglobin. |

|

| Lead Poisoning

(Lead-contaminated paint dust, water, or food and bullets in wild game)[16],[17] |

Abdominal pain, constipation, fatigue, joint pain, muscle pain, headache, anemia, memory deficits, psychiatric symptoms, elevated blood pressure, decreased kidney function, decreased sperm count, increased mortality

*Note: Some symptoms may be irreversible. |

|

| Formaldehyde Poisoning

(Construction and agriculture products and disinfectants)[18] |

Eye and skin irritation, abdominal pain, bronchospasm, shortness of breath, decreased respiratory rate, acute kidney failure |

|

| Arsenic Poisoning

(Contaminated groundwater, tobacco smoke, hide tanning, and pressure treated wood)[19],[20] |

Nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, paresthesias, muscle cramping, skin pigmentation changes, skin lesions and cancers, cardiac dysrhythmias, death |

|

| Mercury

(Thermometers, sphygmomanometers, fluorescent light bulbs, amalgam tooth fillings, and contaminated fish)[21] |

Acute inhalation exposure in occupational settings may cause cough, dyspnea, chest pain, excessive salivation, inflammation of gums, severe nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, dermatitis |

|

| Radon Gas

(Naturally occurring gas resulting from the decay of trace amounts of uranium found in the earth’s crust)[22] |

Persistent cough, hoarseness, wheezing, shortness of breath, coughing up blood, chest pain, frequent respiratory infections like bronchitis and pneumonia, loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, lung cancer |

|

| Infectious Disease

(HIV, hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and COVID-19) |

Symptoms are based on disease process |

|

| Frostbite

(Overexposure of skin to cold)[23] |

White or grayish color of exposed skin, may be hard or waxy to touch; lack of sensitivity to touch or numbness and tingling; clear or blood-filled blisters after thawing; cyanosis after rewarming indicates necrosis |

|

| Organophosphates

(Insecticides and bioterrorism nerve agents)[24] |

Acute onset of symptoms related to cholinergic excess: bradycardia, increased salivation, tearing, urination, vomiting and diarrhea, diaphoresis, paralysis, respiratory failure, hypotension, seizures

Intermediate syndrome: neck flexion weakness, cranial nerve abnormalities, muscle weakness |

|

| Bioterrorism

(Anthrax, smallpox, nerve agents, and ricin)[25] |

Symptoms are based on the agent |

|

Access up-to-date, evidence-based information for suspected poisoning at the Poison Control Center or call 1-800-222-1222.

Read more about Patient Decontamination in a Mass Chemical Exposure Incident by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Recovery

During the recovery period, restoration efforts occur concurrently with regular operations and activities. The recovery period from a disaster can be prolonged. Examples of recovery activities include the following[26]:

- Preventing or reducing stress-related illnesses and excessive financial burdens

- Rebuilding damaged structures

- Reducing vulnerability to future disasters

When people are affected by a disaster, they may respond in a variety of different ways. It is natural and expected to respond to a disaster with emotions such as fear, worry, sadness, anxiety, depression, and despair. Many people exhibit resiliency, the ability to cope with adversity and recover emotionally from a traumatic event.[27] However, the mental health of the population must be considered and monitored during recovery from any disastrous event. For example, some people may relive previous traumatic experiences or revert to using substances to cope. Behavioral health responses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorder, and increased risk for suicide should always be considered when assessing individuals’ responses to a disaster.

Effects from trauma extend beyond the physical damages from any disaster. It may take time for individuals to recover physically and emotionally. Survivors of a community disaster should be encouraged to take steps to support each other to promote adaptive coping. Use the following box to read additional information in the “Tips for Survivors of a Traumatic Event” handout by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Read the SAMHSA handout on “Tips for Survivors of a Traumatic Event” PDF.

Review concepts related to loss and the stages of grief in the “Grief and Loss” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Agencies Providing Emergency Assistance

Many federal, state, and local agencies provide support to communities during disasters. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is the agency that promotes disaster mitigation and readiness and coordinates response and recovery following the declaration of a major disaster. FEMA defines a disaster as an event that results in large numbers of deaths and injuries; causes extensive damage or destruction of facilities that provide and sustain human needs; produces an overwhelming demand on state and local response resources and mechanisms; causes a severe long-term effect on general economic activity; and severely affects state, local, and private sector capabilities to begin and sustain response activities.[28] FEMA employees represent every U.S. state, local, tribal, and territorial area and are committed to serving our country before, during, and after disasters.

Disasters are declared using established guidelines and procedures. Because all disasters are local, they are initially declared at the local level. This declaration is typically made by the local mayor. When the mayor determines that capabilities of local resources have been or are expected to be exceeded, state assistance is requested. If the state chooses to respond to a disaster, the governor of the state will direct implementation of the state’s emergency plan. If the governor determines that the resource capabilities of the state are exceeded, the governor can request that the president declare a major disaster in order to make federal resources and assistance available to qualified state and local governments. This ordered sequence is important to ensure appropriate financial assistance.[29]

A state of emergency is declared when public health or the economic stability of a community is threatened, and extraordinary measures of control may be needed. For example, an infectious disease outbreak like COVID-19 can cause the declaration of a state of emergency. A county or municipal agency is designated as the local emergency management agency, and local law specifies the chain of command in emergencies. Use the following box to access more information about federal and local agencies that provide emergency assistance.

Examples of Organizations That Provide Emergency Assistance

Federal

Local

Local county emergency management divisions

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). The future of nursing 2020-2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25982 ↵

- “LA_1603_9thDistDam121.jpg” by Booher, Andrea, Photographer is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Savage, C. L. (2020). Public/community health and nursing practice: Caring for populations (2nd ed.). FA Davis. ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵

- “Environmental Health and Emergency Preparedness” by Dawn Barone for Open RN is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Flanagan, B. E., Hallisey, E. J., Adams, E., & Lavery, A. (2018). Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's social vulnerability index. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(10). 34–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7179070/ ↵

- Flanagan, B. E., Hallisey, E. J., Adams, E., & Lavery, A. (2018). Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's social vulnerability index. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(10). 34–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7179070/ ↵

- Flanagan, B. E., Hallisey, E. J., Adams, E., & Lavery, A. (2018). Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's social vulnerability index. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(10). 34–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7179070/ ↵

- This image is derivative of Flanagan, B. E., Hallisey, E. J., Adams, E., & Lavery, A. (2018). Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's social vulnerability index. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(10), 34–36. Access the report at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7179070/ ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2005). Psychological first aid for first responders. [Handout]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Psychological-First-Aid-for-First-Responders/NMH05-0210 ↵

- “StartAdultTriageAlgorithm.png” by unknown author at CHEMM is in the Public Domain. ↵

- “decontamination26.jpg” by Benjamin Crossley CDP/FEMA is in the Public Domain. ↵

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security, & U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2014). Patient decontamination in a mass chemical exposure incident: National planning guidance for communities. http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/responders/Documents/patient-decon-natl-plng-guide.pdf ↵

- Clardy, P. F., & Manaker, S. (2021, June 17). Carbon monoxide poisoning. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- World Health Organization. (2021, October 11). Lead poisoning. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health ↵

- Goldman, R. H., & Hu, H. (2021, November 4). Lead exposure and poisoning in adults. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2014, October 21). Medical management guidelines for formaldehyde. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/MMG/MMGDetails.aspx?mmgid=216&toxid=39 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2018, February 15). Arsenic. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/arsenic ↵

- Goldman, R. H. (2020, October 8). Arsenic exposure and poisoning. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Beauchamp, G., Kusin, S., & Elinder, C. (2022, February 1). Mercury toxicity. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- National Radon Defense. (n.d.). Radon symptoms. https://www.nationalradondefense.com/radon-information/radon-symptoms.html ↵

- Zafren, K., & Mechem, C. C. (2021, February 1). Frostbite: Emergency care and prevention. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Bird, S. (2021, September 23). Organophosphate and carbamate poisoning. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Adalja, A. A. (2022, January 10). Identifying and managing casualties of biological terrorism. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2022, March 23). Disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/disaster-preparedness ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵

The first IPEC competency is related to values and ethics and states, “Work with individuals of other professions to maintain a climate of mutual respect and shared values.”[1] See the box below for the components related to this competency. Notice how these interprofessional competencies are very similar to the Standards of Professional Performance established by the American Nurses Association related to Ethics, Advocacy, Respectful and Equitable Practice, Communication, and Collaboration.[2]

Components of IPEC’s Values/Ethics for Interprofessional Practice Competency[3]

- Place interests of clients and populations at the center of interprofessional health care delivery and population health programs and policies, with the goal of promoting health and health equity across the life span.

- Respect the dignity and privacy of clients while maintaining confidentiality in the delivery of team-based care.

- Embrace the cultural diversity and individual differences that characterize clients, populations, and the health team.

- Respect the unique cultures, values, roles/responsibilities, and expertise of other health professions and the impact these factors can have on health outcomes.

- Work in cooperation with those who receive care, those who provide care, and others who contribute to or support the delivery of prevention and health services and programs.

- Develop a trusting relationship with clients, families, and other team members.

- Demonstrate high standards of ethical conduct and quality of care in contributions to team-based care.

- Manage ethical dilemmas specific to interprofessional client/population-centered care situations.

- Act with honesty and integrity in relationships with clients, families, communities, and other team members.

- Maintain competence in one’s own profession appropriate to scope of practice.

Nursing, medical, and other health professional programs typically educate students in “silos” with few opportunities to collaboratively work together in the classroom or in clinical settings. However, after being hired for their first job, these graduates are thrown into complex clinical situations and expected to function as part of the team. One of the first steps in learning how to function as part of an effective interprofessional team is to value each health care professional’s contribution to quality, client-centered care. Mutual respect and trust are foundational to effective interprofessional working relationships for collaborative care delivery across the health professions. Collaborative care also honors the diversity reflected in the individual expertise each profession brings to care delivery.[4]

Cultural diversity is a term used to describe cultural differences among clients, family members, and health care team members. While it is useful to be aware of specific traits of a culture, it is just as important to understand that each individual is unique, and there are always variations in beliefs among individuals within a culture. Nurses should, therefore, refrain from making assumptions about the values and beliefs of members of specific cultural groups.[5] Instead, a better approach is recognizing that culture is not a static, uniform characteristic but instead realizing there is diversity within every culture and in every person. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines cultural humility as, “A humble and respectful attitude toward individuals of other cultures that pushes one to challenge their own cultural biases, realize they cannot possibly know everything about other cultures, and approach learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.”[6] It is imperative for nurses to integrate culturally responsive care into their nursing practice and interprofessional collaborative practice.

Read more about cultural diversity, cultural humility, and integrating culturally responsive care in the “Diverse Patients” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Nurses value the expertise of interprofessional team members and integrate this expertise when providing client-centered care. Some examples of valuing and integrating the expertise of interprofessional team members include the following:

- A nurse is caring for a client admitted with chronic heart failure to a medical-surgical unit. During the shift the client’s breathing becomes more labored and the client states, “My breathing feels worse today.” The nurse ensures the client’s head of bed is elevated, oxygen is applied according to the provider orders, and the appropriate scheduled and PRN medications are administered, but the client continues to complain of dyspnea. The nurse calls the respiratory therapist and requests a STAT consult. The respiratory therapist assesses the client and recommends implementation of BiPAP therapy. The provider is notified and an order for BiPAP is received. The client reports later in the shift the dyspnea is resolved with the BiPAP therapy.

- A nurse is working in the Emergency Department when an adolescent client arrives via ambulance experiencing a severe asthma attack. The paramedic provides a handoff report with the client's current vital signs, medications administered, and intravenous (IV) access established. The paramedic also provides information about the home environment, including information about vaping products and a cat in the adolescent’s bedroom. The nurse thanks the paramedic for sharing these observations and plans to use information about the home environment to provide client education about asthma triggers and tobacco cessation after the client has been stabilized.

- A nurse is working in a long-term care environment with several unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) who work closely with the residents providing personal cares and have excellent knowledge regarding their baseline status. Today, after helping Mrs. Smith with her morning bath, one of the UAPs tells the nurse, “Mrs. Smith doesn’t seem like herself today. She was very tired and kept falling asleep while I was talking to her, which is not her normal behavior.” The nurse immediately assesses Mrs. Smith and confirms her somnolescence and confirms her vital signs are within her normal range. The nurse reviews Mrs. Smith’s chart and notices that a new prescription for furosemide was started last month but no potassium supplements were ordered. The nurse notifies the provider of the client’s change in status and receives an order for lab work including an electrolyte panel. The results indicate that Mrs. Smith’s potassium level has dropped to an abnormal level, which is the likely cause of her fatigue and somnolescence. The provider is notified, and an order is received for a potassium supplement. The nurse thanks the AP for recognizing and reporting Mrs. Smith’s change in status and successfully preventing a poor client outcome such as a life-threatening cardiac dysrhythmia.

Effective client-centered, interprofessional collaborative practice improves client outcomes. View supplementary material and reflective questions in the following box.[7]

View the “How does interprofessional collaboration impact care: The patient’s perspective?” video on YouTube regarding clients' perspectives about the importance of interprofessional collaboration.

Read Ten Lessons in Collaboration. Although this is an older publication, it provides ten lessons to consider in collaborative relationships and practice. The discussion reflects many components of collaboration that have been integral to nursing practice in interprofessional teamwork and leadership.

Reflective Questions

- What is the difference between client-centered care and disease-centered care?

- Why is it important for health professionals to collaborate?

The second IPEC competency relates to the roles and responsibilities of health care professionals and states, “Use the knowledge of one’s own role and those of other professions to appropriately assess and address the health care needs of clients and to promote and advance the health of populations.”[8]

See the following box for the components of this competency. It is important to understand the roles and responsibilities of the other health care team members; recognize one’s limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities; and ask for assistance when needed to provide quality, client-centered care.

Components of IPEC’s Roles/Responsibilities Competency[9]

- Communicate one’s roles and responsibilities clearly to clients, families, community members, and other professionals.

- Recognize one’s limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities.

- Engage with diverse professionals who complement one’s own professional expertise, as well as associated resources, to develop strategies to meet specific health and health care needs of clients and populations.

- Explain the roles and responsibilities of other providers and the manner in which the team works together to provide care, promote health, and prevent disease.

- Use the full scope of knowledge, skills, and abilities of professionals from health and other fields to provide care that is safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable.

- Communicate with team members to clarify each member’s responsibility in executing components of a treatment plan or public health intervention.

- Forge interdependent relationships with other professions within and outside of the health system to improve care and advance learning.

- Engage in continuous professional and interprofessional development to enhance team performance and collaboration.

- Use unique and complementary abilities of all members of the team to optimize health and client care.

- Describe how professionals in health and other fields can collaborate and integrate clinical care and public health interventions to optimize population health.

Nurses communicate with several individuals during a typical shift. For example, during inpatient care, nurses may communicate with clients and their family members; pharmacists and pharmacy technicians; providers from different specialties; physical, speech, and occupational therapists; dietary aides; respiratory therapists; chaplains; social workers; case managers; nursing supervisors, charge nurses, and other staff nurses; assistive personnel; nursing students; nursing instructors; security guards; laboratory personnel; radiology and ultrasound technicians; and surgical team members. Providing holistic, quality, safe, and effective care means every team member taking care of clients must work collaboratively and understand the knowledge, skills, and scope of practice of the other team members. Table 7.4 provides examples of the roles and responsibilities of common health care team members that nurses frequently work with when providing client care. To fully understand the roles and responsibilities of the multiple members of the complex health care delivery system, it is beneficial to spend time shadowing those within these roles.

Table 7.4. Roles and Responsibilities of Members of the Health Care Team

| Member | Role/Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP) (e.g., certified nursing assistants [CNA], patient-care technicians [PCT], certified medical assistants [CMA], certified medication aides, and home health aides) | Work under the direct supervision of the RN. (Read more about Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP) in the “Delegation and Supervision” chapter.) |

| Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses (LPN/VN) | Assist the RN by performing routine, basic nursing care with predictable outcomes. (Read more details in the “Delegation and Supervision” chapter.) |

| Registered Nurses (RN) | Use the nursing process to assess, diagnose, identify expected outcomes, plan and implement interventions, and evaluate care according to the Nurse Practice Act of the state they are employed. |

| Charge Nurses or Nursing Supervisors | Supervise members of the nursing team and overall client care on the unit (or organization) to ensure quality, safe care is delivered. |

| Directors of Nursing (DON), Chief Nursing Officer (CNO), or Vice President of Patient Services | Ensure federal and state regulations and standards are being followed and are accountable for all aspects of client care. |

| Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) | Practice in a variety of health care environments and participate in mentoring other nurses, case management, research, designing and conducting quality improvement programs, and serving as educators and consultants. |

| Nurse Practitioners (NP) or Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRN) | Work in a variety of settings and complete physical examinations, diagnose and treat common acute illness, manage chronic illness, order laboratory and diagnostic tests, prescribe medications and other therapies, provide health teaching and supportive counseling with an emphasis on prevention of illness and health maintenance, and refer clients to other health professionals and specialists as needed. NPs have advanced knowledge with a graduate degree and national certification. |

| Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNA) | Administer anesthesia and related care before, during, and after surgical, therapeutic, diagnostic, and obstetrical procedures, as well as provide airway management during medical emergencies. |

| Certified Nurse Midwives (CNM) | Provide gynecological exams, family planning guidance, prenatal care, management of low-risk labor and delivery, and neonatal care. |

| Medical Doctors (MD) | Licensed providers who diagnose, treat, and direct medical care. There are many types of physician specialists such as surgeons, pulmonologists, neurologists, cardiologists, nephrologists, pediatricians, and ophthalmologists. |

| Physician Assistants (PA) | Work under the direct supervision of a medical doctor as licensed and certified professionals following protocols based on the state in which they practice. |

| Doctors of Osteopathy (DO) | Licensed providers similar to medical physicians but with different educational preparation and licensing exams. They provide care, prescribe, and can perform surgeries. |

| Dieticians | Assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions related to specific dietary needs of clients, including regular or therapeutic diets. Formulate diets for clients with dysphagia or other physical disorders and provide dietary education such as diabetes education. |

| Physical Therapists (PT) | Develop and implement a plan of care as a licensed professional for clients with dysfunctional physical abilities, including joints, strength, mobility, gait, balance, and coordination. |

| Occupational Therapists (OT) | Plan, provide, and evaluate care for clients with dysfunction affecting their independence and ability to complete activities of daily living (ADLs). Assist clients in using adaptive devices to reach optimal levels of functioning and provide home safety assessments. |

| Speech Therapists (ST) | Develop and initiate a plan of care for clients diagnosed with communication and swallowing disorders. |

| Respiratory Therapists (RT) | Specialize in treating clients with respiratory disorders or conditions in collaboration with providers. Provide treatments such as CPAP, BiPAP, respiratory treatments and medications like aerosol nebulizers, chest physiotherapy, and postural drainage. They also intubate clients, assist with bronchoscopies, manage mechanical ventilation, and perform pulmonary function tests. |

| Social Workers (SW) | Provide a liaison between the community and the health care setting to ensure continuity of care after discharge. Assist clients with establishing community resources, health insurance, and advance directives. |

| Psychologists and Psychiatrists | Provide mental health services to clients in both acute and long-term settings. As physician specialists, psychiatrists prescribe medications and perform other medical treatments for mental health disorders. Psychologists focus on counseling. |

| Nurse Case Managers or Discharge Planners | Ensure clients are provided with effective and efficient medical care and services, during inpatient care and post-discharge, while also managing the cost of these services. |

The coordination and delivery of safe, quality client care demands reliable teamwork and collaboration across the organizational and community boundaries. Clients often have multiple visits across multiple providers working in different organizations. Communication failures between health care settings, departments, and team members is the leading cause of client harm.[10] The health care system is becoming increasingly complex requiring collaboration among diverse health care team members. For example, when a COPD exacerbation client is discharged from the acute care setting, their condition may necessitate home resources or care in order to optimize their recovery. This may require the coordination of home oxygen resources, a walker, or home visits in order to assess their transition and recovery. Nurses must understand that community resources are individualized to their regional area and advocating for client needs and resource gaps is an important part of their role.

The goal of good interprofessional collaboration is improved client outcomes, as well as increased job satisfaction of health care team professionals. Clients receiving care with poor teamwork are almost five times as likely to experience complications or death. Hospitals in which staff report higher levels of teamwork have lower rates of workplace injuries and illness, fewer incidents of workplace harassment and violence, and lower turnover.[11]

Valuing and understanding the roles of team members are important steps toward establishing good interprofessional teamwork. Another step is learning how to effectively communicate with interprofessional team members.

Community Resource Care Coordination Case Scenario

Patient Background

Name: Mr. Gerald Hermso

Age: 72

Medical History: Chronic Heart Failure (CHF), Hypertension, Type 2 Diabetes, Hyperlipidemia

Recent Hospitalization: Mr. Hermso was admitted to the hospital due to a CHF exacerbation characterized by shortness of breath, fatigue, and fluid retention. After stabilization with diuretics, beta-blockers, and lifestyle adjustments, Mr. Hermso is ready for discharge.

Discharge Planning Goals:

- Ensure Mr. Hermso's safe transition from hospital to home.

- Minimize the risk of readmission.

- Provide ongoing support for managing CHF at home.

Discharge Coordinator’s Role:

The discharge coordinator plays a crucial role in organizing Mr. Hermso's transition from the hospital to his home. This includes identifying and coordinating community resources that can support his ongoing care.

- Assessment of Needs: The coordinator reviews Mr. Hermso's medical records and discharge plan, including prescribed medications, follow-up appointments, dietary restrictions, and physical activity recommendations. The coordinator assesses Mr. Hermso's living situation. Does he live alone? Does he have any support systems such as family or friends who can assist him? Identify any potential barriers to Mr. Hermso managing his condition at home, such as mobility issues, medication management challenges, or limited access to transportation.

- Collaboration with Nursing Staff: The discharge coordinator collaborates with the nurse assigned to Mr. Hermso to ensure all his needs are met. The nurse provides insights into Mr. Hermso's physical and psychological readiness for discharge. Together, they develop a plan to address his needs post-discharge.

- Community Resources Identification: The discharge coordinator arranges for a home health nurse to visit Mr. Hermso several times a week to monitor his vital signs, administer medications, and provide education on CHF management. The coordinator sets up a service with a local pharmacy for medication delivery and synchronization, ensuring that Mr. Hermso receives his prescriptions on time. The nurse will teach Mr. Hermso how to use a pill organizer. A referral is made to a community dietitian who specializes in CHF to provide Mr. Hermso with personalized meal planning that aligns with his dietary restrictions. The coordinator arranges for Mr. Hermso to receive telehealth equipment, including a scale and blood pressure monitor, so that his weight and blood pressure can be monitored remotely. The nurse will educate Mr. Hermso on using this equipment. The coordinator refers Mr. Hermso to a local cardiac rehab program, where he can receive supervised exercise and education on heart health. If Mr. Hermso lacks transportation, the coordinator connects him with local transportation services that can take him to follow-up appointments and rehab sessions. The coordinator links Mr. Hermso with a local CHF support group where he can connect with others who have similar experiences, providing emotional and social support.

Nurse's Role:

- Patient Education: The nurse provides detailed education on CHF management, including recognizing early signs of exacerbation, the importance of medication adherence, dietary restrictions (e.g., low-sodium diet), and the need for regular physical activity. The nurse teaches Mr. Hermso how to use his new telehealth equipment and ensures he understands how to log and report his readings.

- Care Coordination: The nurse ensures that all community resources are in place before discharge. This includes confirming home health services, medication delivery, and transportation arrangements. The nurse reviews the discharge plan with Mr. Hermso and his family (if applicable) to ensure they understand the follow-up schedule and how to access the resources provided.

- Follow-up: The nurse schedules a follow-up call within 48 hours of discharge to check on Mr. Hermso’s progress, answer any questions, and address any emerging issues.

Outcome:

- Immediate Post-Discharge: Mr. Hermso transitions home with a solid support system in place. He has access to home health services, medication management, dietary support, and telehealth monitoring.

- Long-term Monitoring: Through consistent follow-up and engagement with community resources, Mr. Hermso is better equipped to manage his CHF at home, reducing the likelihood of readmission and improving his overall quality of life.

The third IPEC competency focuses on interprofessional communication and states, “Communicate with clients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease.”[12] See Figure 7.1[13] for an image of interprofessional communication supporting a team approach. This competency also aligns with The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goal for improving staff communication.[14] See the following box for the components associated with the Interprofessional Communication competency.

Components of IPEC’s Interprofessional Communication Competency[15]

- Choose effective communication tools and techniques, including information systems and communication technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that enhance team function.

- Communicate information with clients, families, community members, and health team members in a form that is understandable, avoiding discipline-specific terminology when possible.

- Express one’s knowledge and opinions to team members involved in client care and population health improvement with confidence, clarity, and respect, working to ensure common understanding of information, treatment, care decisions, and population health programs and policies.

- Listen actively and encourage ideas and opinions of other team members.

- Give timely, sensitive, constructive feedback to others about their performance on the team, responding respectfully as a team member to feedback from others.

- Use respectful language appropriate for a given difficult situation, crucial conversation, or conflict.

- Recognize how one’s uniqueness (experience level, expertise, culture, power, and hierarchy within the health care team) contributes to effective communication, conflict resolution, and positive interprofessional working relationships.

- Communicate the importance of teamwork in client-centered care and population health programs and policies.

Transmission of information among members of the health care team and facilities is ongoing and critical to quality care. However, information that is delayed, inefficient, or inadequate creates barriers for providing quality of care. Communication barriers continue to exist in health care environments due to interprofessional team members’ lack of experience when interacting with other disciplines. For instance, many novice nurses enter the workforce without experiencing communication with other members of the health care team (e.g., providers, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, surgical staff, dieticians, physical therapists, etc.). Additionally, health care professionals tend to develop a professional identity based on their educational program with a distinction made between groups. This distinction can cause tension between professional groups due to diverse training and perspectives on providing quality client care. In addition, a health care organization’s environment may not be conducive to effectively sharing information with multiple staff members across multiple units.

In addition to potential educational, psychological, and organizational barriers to sharing information, there can also be general barriers that impact interprofessional communication and collaboration. See the following box for a list of these general barriers.[16]

General Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[17]

- Personal values and expectations

- Personality differences

- Organizational hierarchy

- Lack of cultural humility

- Generational differences

- Historical interprofessional and intraprofessional rivalries

- Differences in language and medical jargon

- Differences in schedules and professional routines

- Varying levels of preparation, qualifications, and status

- Differences in requirements, regulations, and norms of professional education

- Fears of diluted professional identity

- Differences in accountability and reimbursement models

- Diverse clinical responsibilities

- Increased complexity of client care

- Emphasis on rapid decision-making

There are several national initiatives that have been developed to overcome barriers to communication among interprofessional team members. These initiatives are summarized in Table 7.5a.[18]

Table 7.5a. Initiatives to Overcome Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[19]

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Teach structured interprofessional communication strategies | Structured communication strategies, such as ISBARR, handoff reports, I-PASS reports, and closed-loop communication should be taught to all health professionals. |

| Train interprofessional teams together | Teams that work together should train together. |

| Train teams using simulation | Simulation creates a safe environment to practice communication strategies and increase interdisciplinary understanding. |

| Define cohesive interprofessional teams | Interprofessional health care teams should be defined within organizations as a cohesive whole with common goals and not just a collection of disciplines. |

| Create democratic teams | All members of the health care team should feel valued. Creating democratic teams (instead of establishing hierarchies) encourages open team communication. |

| Support teamwork with protocols and procedures | Protocols and procedures encouraging information sharing across the whole team include checklists, briefings, huddles, and debriefing. Technology and informatics should also be used to promote information sharing among team members. |

| Develop an organizational culture supporting health care teams | Agency leaders must establish a safety culture and emphasize the importance of effective interprofessional collaboration for achieving good client outcomes. |

Communication Strategies

Several communication strategies have been implemented nationally to ensure information is exchanged among health care team members in a structured, concise, and accurate manner to promote safe client care. Examples of these initiatives are ISBARR, handoff reports, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS. Documentation that promotes sharing information interprofessionally to promote continuity of care is also essential. These strategies are discussed in the following subsections.

ISBARR

A common format used by health care team members to exchange client information is ISBARR, a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back.[20],[21]

- Introduction: Introduce your name, role, and the agency from which you are calling.

- Situation: Provide the client’s name and location, the reason you are calling, recent vital signs, and the status of the client.

- Background: Provide pertinent background information about the client such as admitting medical diagnoses, code status, recent relevant lab or diagnostic results, and allergies.

- Assessment: Share abnormal assessment findings and your evaluation of the current client situation.

- Request/Recommendations: State what you would like the provider to do, such as reassess the client, order a lab/diagnostic test, prescribe/change medication, etc.

- Repeat back: If you are receiving new orders from a provider, repeat them to confirm accuracy. Be sure to document communication with the provider in the client’s chart.

Nursing Considerations

Before using ISBARR to call a provider regarding a changing client condition or concern, it is important for nurses to prepare and gather appropriate information. See the following box for considerations when calling the provider.

Communication Guidelines for Nurses[22]

- Have I assessed this client before I call?

- Have I reviewed the current orders?

- Are there related standing orders or protocols?

- Have I read the most recent provider and nursing progress notes?

- Have I discussed concerns with my charge nurse, if necessary?

- When ready to call, have the following information on hand:

- Admitting diagnosis and date of admission

- Code status

- Allergies

- Most recent vital signs

- Most recent lab results

- Current meds and IV fluids

- If receiving oxygen therapy, current device and L/min

- Before calling, reflect on what you expect to happen as a result of this call and if you have any recommendations or specific requests.

- Repeat back any new orders to confirm them.

- Immediately after the call, document with whom you spoke, the exact time of the call, and a summary of the information shared and received.

Read an example of an ISBARR report in the following box.

Sample ISBARR Report From a Nurse to a Health Care Provider

I: “Hello Dr. Smith, this is Jane Smith, RN from the Med-Surg unit.”

S: “I am calling to tell you about Ms. White in Room 210, who is experiencing an increase in pain, as well as redness at her incision site. Her recent vital signs were BP 160/95, heart rate 90, respiratory rate 22, O2 sat 96% on room air, and temperature 38 degrees Celsius. She is stable but her pain is worsening.”

B: “Ms. White is a 65-year-old female, admitted yesterday post hip surgical replacement. She has been rating her pain at 3 or 4 out of 10 since surgery with her scheduled medication, but now she is rating the pain as a 7, with no relief from her scheduled medication of Vicodin 5/325 mg administered an hour ago. She is scheduled for physical therapy later this morning and is stating she won’t be able to participate because of the pain this morning.”

A: “I just assessed the surgical site, and her dressing was clean, dry, and intact, but there is 4 cm redness surrounding the incision, and it is warm and tender to the touch. There is moderate serosanguinous drainage. Her lungs are clear, and her heart rate is regular. She has no allergies. I think she has developed a wound infection.”

R: “I am calling to request an order for a CBC and increased dose of pain medication.”

R: “I am repeating back the order to confirm that you are ordering a STAT CBC and an increase of her Vicodin to 10/325 mg.”

View or print an ISBARR reference card.

Handoff Reports

Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as “a transfer and acceptance of client care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing client specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the client’s care.”[23] In 2017 The Joint Commission issued a sentinel alert about inadequate handoff communication that has resulted in client harm such as wrong-site surgeries, delays in treatment, falls, and medication errors.[24]

The Joint Commission encourages the standardization of critical content to be communicated by interprofessional team members during a handoff report both verbally (preferably face to face) and in written form. Critical content to communicate to the receiver in a handoff report includes the following components[25]:

- Sender contact information

- Illness assessment, including severity

- Client summary, including events leading up to illness or admission, hospital course, ongoing assessment, and plan of care

- To-do action list

- Contingency plans

- Allergy list

- Code status

- Medication list

- Recent laboratory tests

- Recent vital signs

Several strategies for improving handoff communication have been implemented nationally, such as the Bedside Handoff Report Checklist, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS.

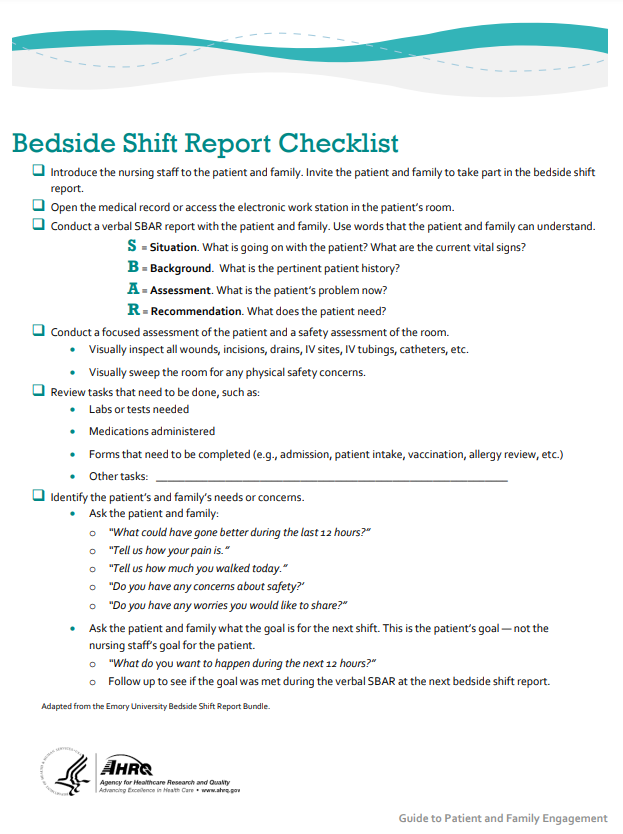

Bedside Handoff Report Checklist

See Figure 7.2[26] for an example of a Bedside Handoff Report Checklist to improve nursing handoff reports by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).[27] Although a bedside handoff report is similar to an ISBARR report, it contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts.

Print a copy of the AHRQ Bedside Shift Report Checklist.[28]

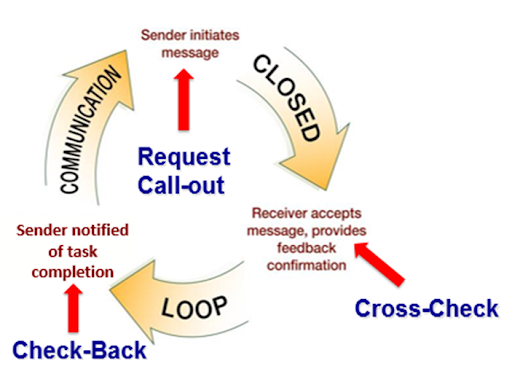

Closed-Loop Communication

The closed-loop communication strategy is used to ensure that information conveyed by the sender is heard by the receiver and completed. Closed-loop communication is especially important during emergency situations when verbal orders are being provided as treatments are immediately implemented. See Figure 7.3[29] for an illustration of closed-loop communication.

- The sender initiates the message.

- The receiver accepts the message and repeats back the message to confirm it (i.e., “Cross-Check”).

- The sender confirms the message.

- The receiver notified the sender the task was completed (i.e., “Check-Back”).

See an example of closed-loop communication during an emergent situation in the following box.

Closed-Loop Communication Example

Doctor: "Administer 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT."

Nurse: "Give 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT?"

Doctor: "That's correct."

Nurse: "Benadryl 25 mg IV push given at 1125."

I-PASS

I-PASS is a mnemonic used to provide structured communication among interprofessional team members. I-PASS stands for the following components[30]:

I: Illness severity

P: Patient summary

A: Action list

S: Situation awareness and contingency plans

S: Synthesis by receiver (i.e., closed-loop communication)

See a sample I-PASS Handoff in Table 7.5b.[31]

Table 7.5b. Sample I-PASS Verbal Handoff[32]

| I | Illness Severity | This is our sickest client on the unit, and he's a full code. |

|---|---|---|

| P | Patient Summary | AJ is a 4-year-old boy admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to left lower lobe pneumonia. He presented with cough and high fevers for two days before admission, and on the day of admission to the emergency department, he had worsening respiratory distress. In the emergency department, he was found to have a sodium level of 130 mg/dL likely due to volume depletion. He received a fluid bolus, and oxygen administration was started at 2.5 L/min per nasal cannula. He is on ceftriaxone. |

| A | Action List | Assess him at midnight to ensure his vital signs are stable. Check to determine if his blood culture is positive tonight. |

| S | Situations Awareness & Contingency Planning | If his respiratory distress worsens, get another chest radiograph to determine if he is developing an effusion. |

| S | Synthesis by Receiver | Ok, so AJ is a 4-year-old admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to a left lower lobe pneumonia receiving ceftriaxone, oxygen, and fluids. I will assess him at midnight to ensure he is stable and check on his blood culture. If his respiratory status worsens, I will repeat a radiograph to look for an effusion. |

Listening Skills

Effective team communication includes both the delivery and receipt of the message. Listening skills are a fundamental element of the communication loop. For nursing staff, this involves listening to clients, families, and coworkers. Active listening involves not just hearing the individual words that someone states, but also understanding the emotions and concerns behind the words. Employing active listening reflects an empathetic approach and can improve client outcomes and foster teamwork.

Nurses often serve as the communication bridge between clients, families, and other health care team members. By listening attentively to colleagues, nurses can ensure that important information is accurately conveyed, reducing the risk of misunderstandings and enhancing the overall efficiency of care delivery. This collaborative environment fosters a culture of mutual respect and support, ultimately leading to better health care outcomes.

In order to develop active listening skills, individuals should practice mindfulness and practice their communication techniques. Listening skills can be cultivated with eye contact, actions such as nodding, and demonstration of other nonverbal strategies to demonstrate engagement. Maintaining an open posture, smiling, and attentiveness are all nonverbal strategies that can facilitate communication. It is important to take measures to avoid distractions, offer a summation of the communication, and ask clarifying questions to further develop the communication.

Documentation

Accurate, timely, concise, and thorough documentation by interprofessional team members ensures continuity of care for their clients. It is well-known by health care team members that in a court of law the rule of thumb is, “If it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done.” Any type of documentation in the electronic health record (EHR) is considered a legal document. Abbreviations should be avoided in legal documentation and some abbreviations are prohibited. Please see a list of error prone abbreviations in the box below.

Read the current list of error-prone abbreviations by the Institute of Safe Medication Practices. These abbreviations should never be used when communicating medical information verbally, electronically, and/or in handwritten applications. Abbreviations included on The Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” list are identified with a double asterisk (**) and must be included on an organization’s “Do Not Use” list.

Nursing staff access the electronic health record (EHR) to help ensure accuracy in medication administration and document the medication administration to help ensure client safety. Please see Figure 7.4[33] for an image of a nurse accessing a client’s EHR.

Electronic Health Record

The electronic health record (EHR) contains the following important information:

- History and Physical (H&P): A history and physical (H&P) is a specific type of documentation created by the health care provider when the client is admitted to the facility. An H&P includes important information about the client’s current status, medical history, and the treatment plan in a concise format that is helpful for the nurse to review. Information typically includes the reason for admission, health history, surgical history, allergies, current medications, physical examination findings, medical diagnoses, and the treatment plan.

- Provider orders: This section includes the prescriptions, or medical orders, that the nurse must legally implement or appropriately communicate according to agency policy if not implemented.

- Medication Administration Records (MARs): Medications are charted through electronic medication administration records (MARs). These records interface the medication orders from providers with pharmacists and are also the location where nurses document medications administered.

- Treatment Administration Records (TARs): In many facilities, treatments are documented on a treatment administration record.

- Laboratory results: This section includes results from blood work and other tests performed in the lab.

- Diagnostic test results: This section includes results from diagnostic tests ordered by the provider such as X-rays, ultrasounds, etc.

- Progress notes: This section contains notes created by nurses, providers, and other interprofessional team members regarding client care. It is helpful for the nurse to review daily progress notes by all team members to ensure continuity of care.

- Nursing care plans: Nursing care plans are created by registered nurses (RNs). Documentation of individualized nursing care plans is legally required in long-term care facilities by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and in hospitals by The Joint Commission. Nursing care plans are individualized to meet the specific and unique needs of each client. They contain expected outcomes and planned interventions to be completed by nurses and other members of the interprofessional team. As part of the nursing process, nurses routinely evaluate the client’s progress toward meeting the expected outcomes and modify the nursing care plan as needed. Read more about nursing care plans in the “Planning” section of the “Nursing Process” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Read the American Nurses Association’s Principles for Nursing Documentation.

Now that we have reviewed the first three IPEC competencies related to valuing team members, understanding team members’ roles and responsibilities, and using structured interprofessional communication strategies, let’s discuss strategies that promote effective teamwork. The fourth IPEC competency states, “Apply relationship-building values and the principles of team dynamics to perform effectively in different team roles to plan, deliver, and evaluate client/population-centered care and population health programs and policies that are safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable.”[34] See the following box for the components of this IPEC competency.

Components of IPEC’s Teams and Teamwork Competency[35]

- Describe the process of team development and the roles and practices of effective teams.

- Develop consensus on the ethical principles to guide all aspects of teamwork.

- Engage health and other professionals in shared client-centered and population-focused problem-solving.

- Integrate the knowledge and experience of health and other professions to inform health and care decisions, while respecting client and community values and priorities/preferences for care.

- Apply leadership practices that support collaborative practice and team effectiveness.

- Engage self and others to constructively manage disagreements about values, roles, goals, and actions that arise among health and other professionals and with clients, families, and community members.

- Share accountability with other professions, clients, and communities for outcomes relevant to prevention and health care.

- Reflect on individual and team performance for individual, as well as team, performance improvement.

- Use process improvement to increase effectiveness of interprofessional teamwork and team-based services, programs, and policies.

- Use available evidence to inform effective teamwork and team-based practices.

- Perform effectively on teams and in different team roles in a variety of settings.

Developing effective teams is critical for providing health care that is client-centered, safe, timely, effective, efficient, and equitable.[36] See Figure 7.5[37] for an image illustrating interprofessional teamwork.

Nurses collaborate with the interprofessional team by not only assigning and coordinating tasks, but also by promoting solid teamwork in a positive environment. A nursing leader, such as a charge nurse, identifies gaps in workflow, recognizes when task overload is occurring, and promotes the adaptability of the team to respond to evolving client conditions. Qualities of a successful team are described in the following box.[38]

Qualities of A Successful Team[39]

- Promote a respectful atmosphere

- Define clear roles and responsibilities for team members

- Regularly and routinely share information

- Encourage open communication

- Implement a culture of safety

- Provide clear directions

- Share responsibility for team success

- Balance team member participation based on the current situation

- Acknowledge and manage conflict

- Enforce accountability among all team members

- Communicate the decision-making process

- Facilitate access to needed resources

- Evaluate team outcomes and adjust as needed

TeamSTEPPS®

TeamSTEPPS® is an evidence-based framework used to optimize team performance across the health care system. It is a mnemonic standing for Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Department of Defense (DoD) developed the TeamSTEPPS® framework as a national initiative to improve client safety by improving teamwork skills and communication.[40]

View this video about the TeamSTEPPS® framework[41]:

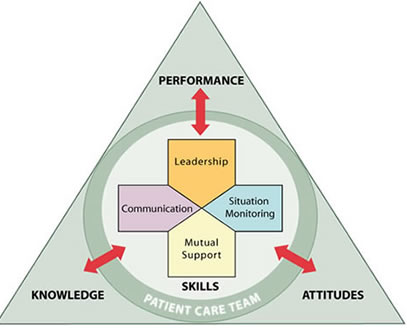

TeamSTEPPS® is based on establishing team structure and four teamwork skills: communication, leadership, situation monitoring, and mutual support.[42] See Figure 7.6[43] for an image of the TeamSTEPPS® framework followed by a description of each TeamSTEPPS® skill. The components of this model are described in the following subsections.

Team Structure

A nursing leader establishes team structure by assigning or identifying team members' roles and responsibilities, holding team members accountable, and including clients and families as part of the team.

Communication

Communication is the first skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework. As previously discussed, it is defined as a “structured process by which information is clearly and accurately exchanged among team members.” All team members should use these skills to ensure accurate interprofessional communication:

- Provide brief, clear, specific, and timely information to other team members.

- Seek information from all available sources.

- Use ISBARR and handoff techniques to communicate effectively with team members.

- Use closed-loop communication to verify information is communicated, understood, and completed.

- Document appropriately to facilitate continuity of care across interprofessional team members.

These communication strategies are further described in the “Interprofessional Communication” section of this chapter.

Leadership

Leadership is the second skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework. As previously discussed, it is defined as the “ability to maximize the activities of team members by ensuring that team actions are understood, changes in information are shared, and team members have the necessary resources.” An example of a nursing team leader in an inpatient setting is the charge nurse.

Effective team leaders demonstrate the following responsibilities[44]:

- Organize the team.

- Identify and articulate clear goals (i.e., share the plan).

- Assign tasks and responsibilities.

- Monitor and modify the plan and communicate changes.

- Review the team's performance and provide feedback when needed.

- Manage and allocate resources.

- Facilitate information sharing.

- Encourage team members to assist one another.

- Facilitate conflict resolution in a learning environment.

- Model effective teamwork.

Three major leadership tasks include sharing a plan, monitoring and modifying the plan according to situations that occur, and reviewing team performance. Tools to perform these tasks are discussed in the following subsections.

Sharing the Plan

Nursing team leaders identify and articulate clear goals to the team at the start of the shift during inpatient care using a “brief.” The brief is a short session to share a plan, discuss team formation, assign roles and responsibilities, establish expectations and climate, and anticipate outcomes and contingencies. See a Brief Checklist in the following box with questions based on TeamSTEPPS®.[45]

Brief Checklist

During the brief, the team should address the following questions[46]:

___ Who is on the team?

___ Do all members understand and agree upon goals?

___ Are roles and responsibilities understood?

___ What is our plan of care?

___ What are staff and provider's availability throughout the shift?

___ How is workload shared among team members?

___ Who are the sickest clients on the unit?

___ Which clients have a high fall risk or require 1:1?

___ Do any clients have behavioral issues requiring consistent approaches by the team?

___ What resources are available?

Monitoring and Modifying the Plan

Throughout the shift, it is often necessary for the nurse leader to modify the initial plan as client situations change on the unit. A huddle is a brief meeting before and/or during a shift to establish situational awareness, reinforce plans already in place, and adjust the teamwork plan as needed. Read more about situational awareness in the “Situation Monitoring” subsection below.

Reviewing the Team's Performance

When a significant or emergent event occurs during a shift, such as a “code,” it is important to later review the team’s performance and reflect on lessons learned by holding a “debrief” session. A debrief is an informal information exchange session designed to improve team performance and effectiveness through reinforcement of positive behaviors and reflection on lessons learned.[47] See the following box for a Debrief Checklist.

Debrief Checklist[48]

The team should address the following questions during a debrief:

___ Was communication clear?

___ Were roles and responsibilities understood?

___ Was situation awareness maintained?

___ Was workload distribution equitable?

___ Was task assistance requested or offered?

___ Were errors made or avoided?

___ Were resources available?

___ What went well?

___ What should be improved?

Situation Monitoring

Situation monitoring is the third skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework and defined as the “process of actively scanning and assessing situational elements to gain information or understanding, or to maintain awareness to support team functioning.” Situation monitoring refers to the process of continually scanning and assessing the situation to gain and maintain an understanding of what is going on around you. Situation awareness refers to a team member knowing what is going on around them. The team leader creates a shared mental model to ensure all team members have situation awareness and know what is going on as situations evolve. The STEP tool is used by team leaders to assist with situation monitoring.[49]

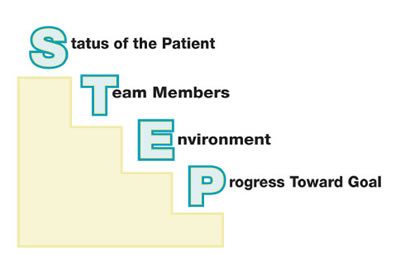

STEP

The STEP tool is a situation monitoring tool used to know what is going on with you, your clients, your team, and your environment. STEP stands for Status of the clients, Team members, Environment, and Progress toward goal. See an illustration of STEP in Figure 7.7.[50] The components of the STEP tool are described in the following box.[51]

STEP Tool[52]

Status of Clients: “What is going on with your clients?”

__ Patient History

__ Vital Signs

__ Medications

__ Physical Exam

__ Plan of Care

__ Psychosocial Issues

Team Members: “What is going on with you and your team?”(See the “I’M SAFE Checklist” below.)

__ Fatigue

__ Workload

__ Task Performance

__ Skill

__ Stress

Environment: Knowing Your Resources

__ Facility Information

__ Administrative Information

__ Human Resources

__ Triage Acuity

__ Equipment

Progression Towards Goal:

__ Status of the Team's Clients

__ Established Goals of the Team

__ Tasks/Actions of the Team

__ Appropriateness of the Plan and are Modifications Needed?

Cross-Monitoring

As the STEP tool is implemented, the team leader continues to cross monitor to reduce the incidence of errors. Cross-monitoring includes the following[53]:

- Monitoring the actions of other team members.

- Providing a safety net within the team.

- Ensuring that mistakes or oversights are caught quickly and easily.

- Supporting each other as needed.

I’M SAFE Checklist

The I’M SAFE mnemonic is a tool used to assess one’s own safety status, as well as that of other team members in their ability to provide safe client care. See the I’M SAFE Checklist in the following box.[54] If a team member feels their ability to provide safe care is diminished because of one of these factors, they should notify the charge nurse or other nursing supervisor. In a similar manner, if a nurse notices that another member of the team is impaired or providing care in an unsafe manner, it is an ethical imperative to protect clients and report their concerns according to agency policy.[55]

I’m SAFE Checklist[56]

__ I: Illness

__M: Medication

__S: Stress

__A: Alcohol and Drugs

__F: Fatigue

__E: Eating and Elimination

Read an example of a nursing team leader performing situation monitoring using the STEP tool in the following box.

Example of Situation Monitoring