12 Virtues of Logic: Cultivating Character and Skill in Argumentation

A Little More Logical | Brendan Shea, PhD (Brendan.Shea@rctc.edu)

In this chapter, we explore the intersection of logic, argumentation, and character. Drawing on Aristotle’s concept of virtue ethics, we examine how cultivating certain virtues and avoiding vices can make us better thinkers and arguers. We look at examples from philosophy, literature, film and history to illustrate the power of combining good character with strong reasoning skills. Practicing virtues like intellectual humility, empathy, and epistemic responsibility can lead to more constructive dialogues and sounder judgments. The chapter also examines pitfalls that arise from either lack of virtue or lack of skill, and considers how virtue argumentation relates to areas like mental health and political polarization. Ultimately, virtuous and skilled argumentation is presented as a worthy ideal to strive for – one that can help elevate the quality of our thinking, our discourse, and our lives.

Learning Outcomes:

- Understand the key tenets of virtue ethics and how they apply to argumentation, including the doctrine of the mean and the importance of cultivating good character through practice.

- Identify important argumentative virtues such as open-mindedness, empathy, intellectual humility, and epistemic responsibility, and recognize them in action in examples from philosophy, literature, and pop culture.

- Distinguish between the two main ways arguments can go wrong – through vices that aim to confuse others and lack of skills that end up confusing ourselves – and learn strategies for avoiding these pitfalls.

- Examine the parallels between the principles of virtue argumentation and cognitive behavioral therapy techniques for improving mental health and well-being.

- Apply the lessons of virtue argumentation to the challenges of political polarization, learning from historical examples like Lincoln and Oppenheimer about how to navigate high-stakes debates with integrity and wisdom.

Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics and the Good Life

Have you ever wondered what it means to be a truly good person? The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle had some fascinating ideas about this. He developed a theory called “virtue ethics” that is still influential today.

Aristotle believed that the key to living a good life, which he called “eudaimonia” (often translated as happiness or flourishing), was to cultivate virtues. Virtues are positive character traits like courage, wisdom, justice, and self-control.

According to Aristotle, virtues are the “golden mean” between two extremes. For example, courage is the middle ground between cowardice and recklessness. A courageous person is neither too timid nor too brash. Aristotle called this idea the “doctrine of the mean.”

To illustrate, think about one of Chandler’s jokes from the TV show Friends. In trying to be funny, he often goes too far and ends up offending people. Aristotle would say Chandler is being reckless with his humor – an excess of wit without enough sensitivity. The virtuous mean would be telling jokes that are funny but also kind and appropriate for the audience.

Other examples might include:

|

Virtue |

Explanation |

|

Courage (Recklessness, Cowardice) |

The virtue of facing fear and danger with confidence and bravery. It is the mean between the excess of recklessness, which is acting without proper caution, and the deficiency of cowardice, which is being too afraid to act. |

|

Temperance (Self-indulgence, Insensibility) |

The virtue of moderation in pleasures and desires. It is the mean between the excess of self-indulgence, which is overindulging in pleasures, and the deficiency of insensibility, which is being unresponsive to pleasure. |

|

Justice (Injustice, Injustice) |

The virtue of being fair and impartial. It is the mean between the excess of injustice, which is being unfair or biased, and the deficiency of injustice, which is also being unfair or biased. |

|

Wisdom (Imprudence, Rashness) |

The virtue of making good judgments and decisions. It is the mean between the excess of imprudence, which is being excessively cautious or hesitant, and the deficiency of rashness, which is acting without proper consideration. |

|

Compassion (Pity, Cruelty) |

The virtue of caring for and helping others who are suffering. It is the mean between the excess of pity, which is feeling excessive sorrow or sympathy for others, and the deficiency of cruelty, which is being indifferent or callous to others’ suffering. |

|

Integrity (Dishonesty, Self-righteousness) |

The virtue of being honest and consistent in one’s beliefs and actions. It is the mean between the excess of dishonesty, which is lying or deceiving others, and the deficiency of self-righteousness, which is being overly self-righteous or moralistic. |

|

Humility (Arrogance, Undue humility) |

The virtue of having a reasonable and justified sense of self-worth. It is the mean between the excess of arrogance, which is having an excessive and unwarranted sense of self-worth, and the deficiency of undue humility, which is having too low a sense of self-worth. |

Importantly, Aristotle emphasized that virtues are developed through practice and habit. We aren’t born with a courageous or generous character – we have to cultivate it over time, by repeatedly practicing those behaviors until they become second nature.

So in Aristotle’s view, being an ethically good person is about striving for that golden mean in our character, that balance point where we are at our best. And he thought this was also the surest path to eudaimonia – to a truly happy, successful and flourishing life. Virtue and happiness go hand in hand.

As we’ll see, Aristotle’s ideas provide a helpful lens for looking at what it means to be a good thinker and a skilled reasoner too. His emphasis on cultivating intellectual virtues and avoiding extremes offers valuable insight for improving our arguments and making better decisions.

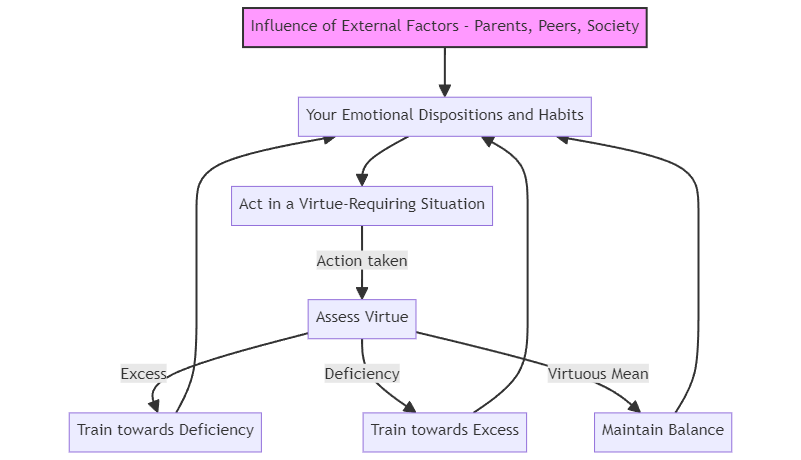

Graphic: Training Aristotelian Virtues

Common Objections to Virtue Ethics

When we try to apply virtue ethics to the realm of argumentation and reasoning, several potential problems arise. However, upon closer examination, these issues can be addressed, allowing us to develop a virtue-based approach to assessing arguments and reasoning. Let’s break down these concerns:

Normativity: Can virtue theories tell us what we ought to do? The first worry is that virtue ethics doesn’t give us clear rules or principles to follow. Unlike other ethical theories that provide strict guidelines, virtue ethics focuses on character traits. So, how can it tell us the right way to argue or reason?

While virtue theories may not offer absolute rules, they still provide guidance. By identifying the virtues of a good reasoner (like open-mindedness, humility, and intellectual courage), we gain a normative standard to strive towards. The virtues point us in the right direction, even if they don’t give us a step-by-step roadmap.

Universality: Can virtue theories apply to everyone, everywhere? Another concern is that virtues seem to vary across cultures and contexts. What counts as good reasoning in one community might not hold up in another. Doesn’t this undermine the universal applicability of virtue-based approaches?

However, while the specific expression of virtues may differ, the core concepts are often shared. Most cultures value traits like honesty, courage, and wisdom, even if they manifest in different ways. By focusing on these common foundations, we can develop a broadly applicable virtue framework for argumentation.

Applicability: Can virtue theories be applied in practice? Finally, there’s the worry that virtue theories are too abstract to be useful in real-world reasoning and argumentation. How do we go from lofty ideals to concrete assessments of arguments?

This is where the rubber meets the road. Virtue theories can inform our practice by giving us role models to emulate and vices to avoid. By studying examples of good and bad reasoning (both in real life and in fiction), we can develop practical wisdom. Over time, we internalize the virtues and learn to apply them flexibly in different situations.

In The Avengers, when Captain America says, “We have orders, we should follow them,” he’s displaying blind obedience – a deficiency of independent thinking. In contrast, when Iron Man pushes back, he’s demonstrating the virtue of critical questioning. Studying exchanges like this attunes us to the virtues and vices of reasoning in action.

So while virtue theories face challenges, they can still provide a valuable framework for evaluating the quality of reasoning and argumentation. By cultivating intellectual virtues, we become better thinkers and arguers, capable of navigating complex issues with wisdom and integrity.

Considerations of Character vs Ad Hominem

When we evaluate arguments, we often hear that we should focus on the content of the argument itself, not on the person making it. This is because of a well-known fallacy called “ad hominem,” which is Latin for “to the person.” An ad hominem argument attacks the character of the person making the argument, rather than addressing the substance of their claims.

For example, imagine a political debate where one candidate says, “We can’t trust my opponent’s tax policy because they cheated on their spouse.” This is a classic ad hominem move. Instead of engaging with the merits of the tax policy, the candidate is trying to undermine their opponent’s credibility by pointing to a character flaw that’s unrelated to the issue at hand.

Ad hominem arguments are considered fallacious because they distract from the actual reasoning and evidence. Even if someone has personal shortcomings, that doesn’t necessarily mean their arguments are wrong. A person’s character and their arguments are logically independent.

However, while ad hominem attacks are often misleading, there are times when a person’s character is relevant to appraising their arguments. In particular, if someone has a known history of dishonesty or bias, that can give us reason to be extra skeptical of their claims.

Consider a few examples:

- In the movie Thank You for Smoking, lobbyist Nick Naylor is known for his clever rhetoric in defending the tobacco industry. However, his arguments are less convincing because we know he’s being paid to promote a product that harms people’s health. His financial incentives to deceive undermine his credibility.

- Imagine a used car salesman who has been caught lying to customers about the condition of his cars. Even if he makes plausible arguments about a particular vehicle, his history of dishonesty gives you reason to doubt his claims and seek independent verification.

- In the play Othello, the villain Iago is known for his manipulative and deceitful nature. So when he starts making insinuations about Desdemona’s faithfulness, the audience has reason to be skeptical. His arguments might sound convincing on the surface, but we know his character is not trustworthy.

In cases like these, the person’s established vices – like greed, dishonesty, or malice – can indeed color our assessment of their arguments. We’re not dismissing their arguments simply because of character flaws, but rather, we’re recognizing that their flaws create a risk factor for bad reasoning or deception.

On the flip side, when someone has demonstrated virtues like honesty, fairness, and expertise, we may have reason to give their arguments more weight. If a trusted doctor with a track record of integrity makes an argument about public health, their good character lends credibility to their claims.

The key is that the character traits have to be directly relevant to the reliability of their arguments. We can’t dismiss arguments because of just any character flaw, but only those that legitimately impact the person’s reasoning or truthfulness.

So while the ad hominem fallacy warns us not to get sidetracked by personal attacks, considerations of character can play a valid role in appraising arguments – as long as those considerations are logically related to the soundness of their reasoning. The intellectual virtues and vices of the arguer can indeed affect our trust in their conclusions.

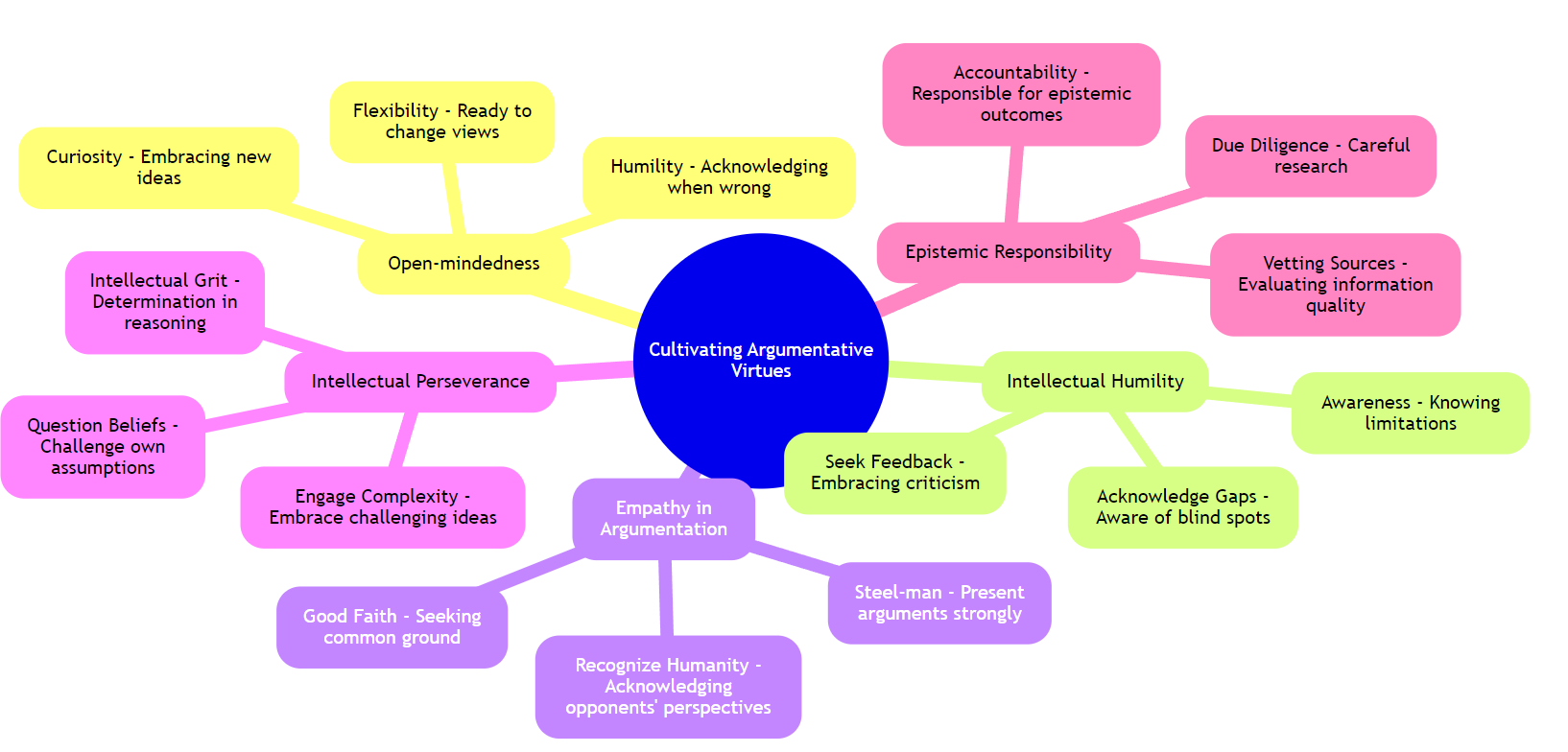

Cultivating Argumentative Virtues

As we’ve seen, while ad hominem attacks are often fallacious, there are times when a person’s character is relevant to evaluating their arguments. Traits like honesty, bias, and expertise can affect the credibility of someone’s reasoning. But beyond just assessing other people’s arguments, we can turn this lens on ourselves. What character traits should we cultivate to be good reasoners and arguers?

Just as Aristotle proposed virtues like courage and temperance for ethical character, we can identify virtues that make for strong intellectual character. These “argumentative virtues” are the habits of mind that promote clear, rigorous, and fair reasoning. Let’s explore a few key examples:

Open-mindedness is the willingness to sincerely consider new ideas and perspectives, even when they challenge our existing beliefs. It means approaching arguments with a spirit of curiosity and flexibility, being ready to change our minds if presented with compelling reasons to do so. An open-minded reasoner is humble enough to acknowledge when they might be wrong, and courageous enough to revise their views in light of strong counterarguments.

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, the protagonist Elizabeth Bennet exemplifies open-mindedness. Early in the novel, she forms a negative opinion of the proud Mr. Darcy based on limited information and her own prejudices. However, as she learns more about Darcy’s true character and motivations, she becomes willing to question her initial judgments. Elizabeth’s openness to new evidence, even when it contradicts her preconceptions, allows her to correct her misjudgments and ultimately find happiness. Her intellectual journey demonstrates how open-mindedness can lead us to a more accurate understanding of the world and of others.

Intellectual humility is the recognition that our knowledge and opinions are always subject to limitations, biases, and errors. It’s the opposite of arrogance or overconfidence in our own intellectual abilities. An intellectually humble person is aware of the gaps and blind spots in their understanding, and actively seeks out feedback, criticism, and opposing perspectives to improve their thinking.

In Moby Dick, the narrator Ishmael demonstrates intellectual humility as he grapples with the complexities of the world and his own place in it. Throughout the novel, Ishmael is eager to learn from those around him, whether it’s the experienced whalers on the Pequod or the various cultures he encounters on his travels. He recognizes the limits of his own understanding, noting that “there is no quality in this world that is not what it is merely by contrast.” This humility allows Ishmael to gain a richer, more nuanced perspective on life, in contrast to the hubristic certainty of Captain Ahab, whose single-minded obsession ultimately leads to destruction.

Empathy in argumentation is the ability to genuinely understand and consider the feelings, experiences, and perspectives of others, especially those with whom we disagree. Empathetic reasoners steel-man opposing arguments, seeking to present them in their strongest and most sympathetic form before offering a critique. They strive to find common ground and engage in good faith, recognizing the humanity in their intellectual opponents.

A powerful example of empathy in argumentation can be found in Atticus Finch from To Kill a Mockingbird. As a lawyer defending a wrongfully accused black man in a racist society, Atticus faces immense hostility and pressure from his community. Yet he persistently tries to understand and appeal to the perspectives of his opponents, whether it’s the prejudiced jurors or his own children as they grapple with the injustice around them. In his famous closing argument, Atticus entreats the jury to set aside their biases and “do their duty,” considering the evidence from a fair and empathetic standpoint. While he doesn’t succeed in swaying the jury, Atticus’s empathetic approach stands as a model of principled, compassionate argumentation in the face of division.

Intellectual perseverance is the willingness to engage with difficult, complex ideas and arguments, even when it’s cognitively challenging or unsettling. It’s the grit and determination to think through issues thoroughly, to follow the reasoning where it leads, even if that means questioning our own cherished beliefs. Perseverant reasoners see intellectual obstacles not as barriers, but as opportunities to deepen their understanding through effort and engagement.

We see a striking example of intellectual perseverance in Sophie Zawistowski from William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice. As a survivor of the Holocaust, Sophie is haunted by impossible moral dilemmas and the weight of her choices. Yet she refuses to shy away from grappling with these painful philosophical questions. In her conversations with the narrator Stingo, Sophie dives unflinchingly into the most troubling implications of her experiences, persisting through the emotional and intellectual anguish they provoke. Her determination to confront the hardest truths and find some meaning in her suffering stands as a testament to the power of intellectual perseverance in the face of even the darkest realities.

Epistemic responsibility is the duty we have as reasoners and arguers to carefully evaluate the quality of the information and sources we use to form our beliefs and make our cases. It means taking due diligence in researching claims, vetting authorities, considering alternative explanations, and holding ourselves accountable for the epistemic consequences of our arguments. Epistemically responsible reasoners serve as careful stewards of the truth.

A case study in epistemic responsibility can be found in the movie Spotlight, which tells the true story of journalists investigating child abuse in the Catholic Church. The reporters, exemplified by Michael Rezendes, demonstrate a deep commitment to rigorously verifying their sources and claims, even under immense social and institutional pressure to back down. They painstakingly chase down every lead, corroborate each accusation, and consider alternative narratives before going public with their explosive findings. In doing so, they uphold the highest standards of epistemic responsibility in their roles as public truth-seekers and argument-makers. The film shows how this sort of diligence and integrity is essential for the health of discourse and society.

By cultivating virtues like open-mindedness, intellectual humility, empathy, perseverance, and epistemic responsibility, we can become better thinkers, communicators, and citizens. We can create a culture of argumentation that is not only more effective at reaching the truth, but also more humane and collaborative in the process. While it’s not always easy to live up to these ideals, embodying them in our everyday reasoning and debate is a worthy aspiration – one that can make a real difference in the quality of our thinking and our public discourse.

The Power of Argumentative Virtues

Why do these argumentative virtues matter? It’s not just about scoring debate points or sounding smart. When adopted on a wide scale, these virtues have the power to propagate truth and improve the quality of discourse across society.

On a personal level, cultivating virtues like open-mindedness and epistemic responsibility makes us better thinkers and decision-makers. By carefully vetting sources and considering alternative perspectives, we’re more likely to form accurate beliefs and make well-reasoned choices. This can have profound effects on our lives, from our health choices to our career paths to our relationships.

In Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, the protagonist Jean Valjean embodies the transformative power of open-mindedness and intellectual humility. After serving a lengthy prison sentence, Valjean initially struggles to shed his identity as a hardened criminal. But a pivotal encounter with a merciful bishop prompts Valjean to reconsider his choices and beliefs. By humbly opening his mind to a different way of living, Valjean is able to break the cycle of anger and resentment, ultimately becoming a force for compassion and positive change in the lives of others. His story demonstrates how a willingness to question our assumptions and learn from others’ perspectives can set us on a path to moral and intellectual growth.

But the impact of these virtues goes beyond the individual. When communities and institutions embrace them, it can lead to better collective outcomes and a healthier public discourse.

Consider the vital role that epistemic responsibility plays in the pursuit of justice. In the documentary series Making a Murderer, defense attorneys Dean Strang and Jerry Buting tirelessly work to uncover the truth behind a potentially wrongful conviction. Despite facing a system stacked against them, Strang and Buting remain committed to rigorously examining the evidence, questioning the official narrative, and advocating for their client’s rights. Their intellectual perseverance in the face of daunting odds exemplifies the kind of responsible truth-seeking that is essential to a functioning legal system. By holding themselves and the state accountable to high epistemic standards, defenders like Strang and Buting uphold the integrity of the justice process and work to prevent grievous errors.

Or picture a media landscape where news organizations embraced epistemic responsibility, carefully vetting information before disseminating it and transparently correcting errors. We could have more confidence in the accuracy of the information we consume and a more solid foundation of shared facts upon which to base public discourse. The 2017 documentary “The Post” tells the real-life story of journalists at the Washington Post who published the Pentagon Papers, revealing the U.S. government’s deception about the Vietnam War. The film shows the reporters’ commitment to rigorously verifying their sources and considering the public interest, even in the face of enormous political pressure. Their adherence to epistemic responsibility helped expose important truths and inform the public debate.

Even in the realm of science and scholarship, argumentative virtues are key. The academic enterprise is built on principles like intellectual humility, recognizing the limits of our knowledge, and perseverance in the pursuit of truth. The 2014 film “The Theory of Everything” depicts the life of legendary physicist Stephen Hawking, who exemplified these virtues. Despite facing immense physical challenges and having his groundbreaking ideas initially dismissed by the scientific establishment, Hawking remained humbly open to new evidence and committed to tirelessly developing and communicating his theories. His intellectual character allowed him to revolutionize our understanding of the universe.

On the other hand, when argumentative vices run rampant, the result is often a breakdown of productive discourse and a failure to address pressing issues. In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, the character of Brutus initially appears to embody epistemic responsibility, carefully weighing his duty to Rome against his loyalty to Caesar before joining the conspiracy. However, in the aftermath of the assassination, Brutus fails to anticipate the emotional reaction of the Roman public and cedes the rhetorical high ground to Marc Antony. By allowing his reasoned arguments to be overwhelmed by Antony’s emotive appeals, Brutus demonstrates a lack of rhetorical empathy and adaptability. His inflexible commitment to abstract principles over practical persuasion ultimately dooms the republican cause and plunges Rome into civil war. Brutus’s tragedy is a reminder that even those with ostensibly good intentions can contribute to destructive outcomes if they neglect key argumentative virtues.

As these examples illustrate, the cultivation of argumentative virtues is not just an academic exercise – it has real implications for the health of our personal lives, our institutions, and our public discourse. By striving to emulate the open-mindedness of Valjean, the epistemic responsibility of Strang and Buting, and by learning from the mistakes of characters like Brutus, we can all become better thinkers, communicators, and citizens. In a world rife with polarization, misinformation, and bad-faith argumentation, the argumentative virtues offer a path forward – a way to rebuild the norms and practices that make productive disagreement possible.

Thought Questions

- Aristotle believed that virtues are developed through practice and habit. Can you think of an example from your own life where you had to cultivate a virtue over time? What challenges did you face and how did you overcome them?

- The doctrine of the mean states that virtues are the “golden mean” between two extremes. Choose a virtue and discuss what you think the two extremes would be. How can we strike the right balance in our own lives?

- The document gives the example of the character Chandler from Friends telling offensive jokes. Can you think of a time when you or someone you know went too far in joking around and ended up hurting someone’s feelings? How could the situation have been handled better?

- Do you agree that most cultures share some common virtues, even if they manifest in different ways? What virtues do you think are most universally valued and why?

- The document argues that while ad hominem attacks are often fallacious, there are times when a person’s character is relevant to evaluating their arguments. Do you think it’s ever fair to consider someone’s personal history or motivations when assessing their claims? Why or why not?

- Imagine you are in a debate and your opponent keeps using personal attacks and bad-faith arguments. How could you use the argumentative virtues of empathy, open-mindedness and intellectual perseverance to handle this situation effectively?

- The story of Jean Valjean in Les Miserables is used to illustrate the transformative power of open-mindedness and intellectual humility. Can you think of a time in your life when being open to a new perspective helped you grow as a person? What did you learn from the experience?

- The defense attorneys in Making a Murderer are praised for their epistemic responsibility in the face of a flawed justice system. Do you think lawyers have a special duty to be rigorous truth-seekers? What other professions depend on this virtue?

- The downfall of Brutus in Julius Caesar is partially attributed to his lack of “rhetorical empathy.” Why do you think the ability to anticipate and appeal to an audience’s emotions is an important argumentative skill? Can you think of a powerful speech that moved you personally?

The Two Pitfalls of Argumentation: Vices and Lack of Skill

When we engage in argumentation, there are two main ways our arguments can go astray: by confusing others through a lack of virtue, or by confusing ourselves through a lack of skill. Understanding this distinction is crucial for improving the quality of our discourse and becoming more effective reasoners.

First, let’s consider how arguments can fail by confusing others. This happens when an arguer lacks key argumentative virtues like honesty, empathy, and fairness. Instead of striving to engage in good faith and find genuine understanding, the vicious arguer employs manipulative tactics designed to mislead or overpower their opponent.

One common manifestation of this vice is the use of fallacious reasoning. The vicious arguer may deliberately construct arguments based on logical fallacies, preying on the audience’s cognitive biases and emotions rather than appealing to sound reasoning. For example, they might use ad hominem attacks to discredit their opponent’s character, or employ false dichotomies to make their own position seem like the only reasonable choice.

A prime example of this kind of fallacious argumentation can be found in the character of Emperor Palpatine from the Star Wars franchise. Throughout the prequel trilogy, Palpatine manipulates the Galactic Senate and the Jedi Council by constructing arguments based on fear, prejudice, and false pretenses. He fabricates a phony war, exaggerates threats to security, and scapegoats vulnerable groups like the Jedi in order to justify his own power grabs. Palpatine’s arguments are effective at deceiving both the public and key decision-makers precisely because they exploit their lack of argumentative virtue – their willingness to be misled by appeals to emotion and self-interest rather than reason and evidence.

Another way arguments can go wrong by confusing others is when the arguer lacks the virtue of intellectual empathy. Instead of striving to genuinely understand and address their interlocutor’s perspective, the unempathetic arguer may engage in straw-manning – misrepresenting their opponent’s position in a way that makes it easier to attack. Or they may simply ignore their opponent’s arguments entirely, talking past them rather than engaging substantively with their points.

Martin Luther King Jr. famously encountered this lack of empathy in his interactions with white moderate leaders during the civil rights movement. In his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”, King expresses frustration with those who claim to support the goals of equality and justice, but constantly urge activists to slow down, compromise, and wait for a more convenient time to press for change. King argues that these ostensible allies exhibit a failure of moral and intellectual empathy – they prioritize their own comfort and an illusion of social peace over engaging with the perspective of the oppressed. By refusing to grapple with the actual arguments and demands of the civil rights movement, the white moderates end up perpetuating the very injustices they claim to oppose.

On the other hand, arguments can also fail by confusing the arguer themselves. This happens when the arguer lacks the necessary skills to construct and evaluate arguments effectively. Even if their intentions are virtuous, a lack of argumentative competence can lead them to embrace and spread faulty reasoning.

One common way this plays out is through a lack of skill in evaluating sources and evidence. The unskilled arguer may be taken in by misinformation or propaganda, failing to properly vet claims before accepting and repeating them. They may fall prey to confirmation bias, only seeking out evidence that supports their preexisting views while dismissing contradictory information.

We can see this dynamic at work in the documentary Behind the Curve, which explores the world of flat Earth believers. Many of the individuals profiled in the film seem genuinely convinced of their beliefs and committed to spreading what they see as the truth. However, their lack of scientific literacy and critical thinking skills leads them to embrace a wide range of baseless conspiracy theories and pseudoscientific claims. Despite their intellectual sincerity, their arguments are utterly confused and divorced from reality due to a fundamental lack of argumentative competence.

Another way unskilled arguers can end up confusing themselves is through a lack of logical coherence. They may make arguments that are internally inconsistent or that don’t logically support their conclusions. Even if the individual steps of their argument make sense, a lack of skill in structuring and analyzing arguments can lead to a muddled and unconvincing overall case.

An example of this can be found in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. The protagonist Raskolnikov constructs an elaborate philosophical justification for committing murder, arguing that extraordinary individuals have a right to transgress moral boundaries for the greater good. However, as the novel progresses, it becomes clear that his argument is riddled with logical inconsistencies and unexamined assumptions. Raskolnikov’s lack of skill in rigorously examining his own reasoning leads him to become confused and tortured by doubts, even as he tries to convince himself and others of his argument’s validity.

It’s important to note that argumentative vices and lack of skill often go hand in hand. The vicious arguer, unconstrained by a commitment to truth and fairness, is more likely to employ fallacious reasoning and prioritize persuasion over logical coherence. At the same time, a lack of argumentative skill can make one more susceptible to bad-faith tactics, as it’s harder to identify and refute manipulative arguments.

However, the two problems are distinct and require different remedies. Overcoming argumentative vices requires a fundamental reorientation of values and character – a commitment to embodying virtues like honesty, empathy, and open-mindedness. Developing argumentative skills, on the other hand, is a matter of education and practice – learning the principles of logic, familiarizing oneself with common fallacies, and honing one’s ability to construct and critique arguments.

A truly skilled and virtuous arguer is one who combines both characterological and technical excellence. They are committed to engaging in good faith and following the arguments where they lead, but also possess the knowledge and competence to reason effectively. We might think of an ideal like Martin Luther King Jr. himself, who demonstrated both a deep moral conviction and a formidable ability to construct persuasive arguments for justice and equality.

Aspiring to this kind of argumentative virtue and skill is a lifelong endeavor, requiring constant self-reflection and practice. But it’s an endeavor that’s deeply worthwhile, both for our individual growth and for the health of our collective discourse. In a world where vicious and unskilled argumentation runs rampant, we desperately need more models of what good argumentation can look like – argumentation that brings light rather than heat, that aims at mutual understanding rather than domination, and that views every disagreement as an opportunity to sharpen our thinking and move closer to the truth. By striving to embody these ideals, we can all play a role in making that world a reality.

The Ideal of the Virtuous and Skilled Arguer

Throughout our exploration of argumentative virtues and vices, a central idea has emerged: the best arguers are those who combine both virtue and skill in their reasoning and discourse. While it’s possible to argue with good intentions but poor technique, or to deploy sophisticated logical and rhetorical strategies in the service of manipulation and deception, the ideal arguer is one who unites a commitment to truth and fairness with the ability to reason effectively and persuasively.

Consider the example of Atticus Finch from Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. As a lawyer defending a falsely accused black man in a racist society, Atticus faces immense pressure to compromise his principles and pander to the prejudices of the jury. However, he remains steadfast in his commitment to justice and equality, refusing to resort to underhanded tactics or emotional appeals. At the same time, Atticus is a skilled legal mind, able to construct logical, evidence-based arguments that expose the inconsistencies and biases in the prosecution’s case. Even though he ultimately loses the trial, Atticus’s combination of moral courage and argumentative competence makes him a powerful role model for his children and community.

On the other hand, an arguer who possesses virtuous intentions but lacks basic argumentative skills can end up doing more harm than good. Imagine a well-meaning activist who is passionate about an important cause, but who constantly makes claims that are unsupported by evidence, engages in fallacious reasoning, and fails to address counterarguments. Even if their heart is in the right place, their lack of skill in constructing and defending arguments can undermine their credibility and ultimately hinder the very goals they’re trying to achieve. Good intentions are not enough – a baseline level of argumentative competence is necessary to participate productively in discourse and avoid spreading confusion and misinformation.

This is why cultivating both virtue and skill is so crucial for anyone who wants to engage in effective argumentation. By committing ourselves to virtues like honesty, open-mindedness, and empathy, we ensure that our arguments are driven by a sincere desire for truth and mutual understanding rather than ego or agenda. And by honing our skills in logic, rhetoric, and critical thinking, we equip ourselves to construct compelling arguments, evaluate claims rigorously, and communicate our ideas clearly and persuasively.

Importantly, this cultivation of virtue and skill is not just an individual pursuit, but a collective one. The more we as a society prioritize and model these ideals of argumentative excellence, the more we can elevate the quality of our public discourse as a whole. We can create a culture where good arguments are valued over cheap point-scoring, where intellectual humility is prized over dogmatic certainty, and where a diversity of viewpoints is seen as an opportunity for growth rather than a threat to be silenced.

This is where the emerging field of virtue argumentation has so much to offer. By providing a framework for analyzing and evaluating the character traits and habits of mind that make for good reasoning, virtue argumentation opens up new avenues for improving our individual and collective argumentative practices. It gives us a vocabulary for praising intellectual courage in the face of groupthink, for valuing fairmindedness over partisan loyalties, for recognizing the importance of perseverance in the pursuit of difficult truths.

Of course, much work remains to be done in fleshing out the details of what specific virtues look like in practice, how they interact with each other, and how they can be cultivated through education and cultural change. But the promise of virtue argumentation is immense. By putting character at the center of our understanding of good reasoning, it offers a richer, more humanistic vision of what argumentation can be – not just a bloodless exchange of proofs and rebuttals, but a way of engaging with each other and the world that calls forth our highest selves.

Ultimately, the goal of virtue argumentation is not just to make us better debaters, but better people. It recognizes that the way we argue reflects something deep about who we are and what we value. When we strive to embody virtues like humility, empathy, and love of truth in our reasoning, we aren’t just improving our chances of winning an argument – we’re shaping our character in ways that ripple out to every aspect of our lives and relationships.

So the next time you find yourself in a disagreement, remember the ideal of the virtuous and skilled arguer. Ask yourself not just whether your argument is logically valid or rhetorically effective, but whether it reflects the kind of person you want to be. Are you arguing to understand, or just to win? Are you considering the perspectives and experiences of others, or just trying to impose your own? Are you willing to follow the truth wherever it leads, even if it means admitting you were wrong?

These are not easy questions, but they are vital ones. For in the end, the quality of our arguments is inextricable from the quality of our character. And in a world that often seems to incentivize intellectual vice and reward argumentative cheap shots, the cultivation of virtue and skill in our reasoning is not just an academic exercise – it’s a moral imperative. It’s a way of fighting back against the tide of bad faith and confused thinking, and of modeling a better way forward.

So let us take up this challenge with courage and conviction. Let us commit ourselves to being the kinds of arguers and the kinds of people who elevate rather than degrade our discourse. Let us see in every disagreement an opportunity to learn, to grow, to move closer to the truth. And let us never forget that in arguing virtuously and skillfully, we are not just making a point – we are making a difference, one conversation at a time.

Logic and Mental Health – Virtue Argumentation and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

As we’ve explored the concepts of virtue argumentation and the importance of cultivating good habits of mind, it’s worth noting the striking parallels between this approach and the principles of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). CBT is a widely used form of psychotherapy that focuses on identifying and changing unhelpful patterns of thinking and behavior in order to improve emotional well-being and cope with life’s challenges.

At its core, CBT is based on the idea that our thoughts, feelings, and actions are all interconnected. When we get stuck in negative, distorted, or irrational ways of thinking, it can lead to emotional distress and unhealthy behaviors. CBT helps individuals recognize these problematic thought patterns and develop strategies for challenging and reframing them in more balanced, realistic ways.

This emphasis on the power of our thoughts and beliefs to shape our experiences has much in common with the central tenets of virtue argumentation. Just as CBT encourages individuals to examine and modify their internal self-talk, virtue argumentation calls on us to be mindful of the quality of our reasoning and to cultivate habits of mind that promote clear, fair, and truth-oriented thinking.

Consider the example of Harley Quinn, the former psychiatrist turned supervillain turned antihero. Throughout her complex history, Harley has struggled with issues of identity, self-worth, and unhealthy relationships. Her tumultuous partnership with the Joker often led her to engage in dichotomous thinking (“Either he loves me or I’m nothing”), minimization of abuse (“He doesn’t mean to hurt me, it’s just how he shows his love”), and self-blame (“It’s my fault for not being good enough for him”).

In CBT terms, these are examples of cognitive distortions – exaggerated, overly negative ways of interpreting reality that can perpetuate cycles of dysfunction and suffering. To break free from these patterns, Harley would need to practice cognitive restructuring – identifying her negative automatic thoughts, examining the evidence for and against them, and generating alternative, more balanced perspectives. She might ask herself questions like, “Is my worth really dependent on the Joker’s approval? What are my own values and strengths outside of this relationship?” or “Is it realistic to expect myself to be perfect and never make mistakes? Can I learn to treat myself with more compassion and understanding?”

This process of self-reflection and rational self-analysis aligns closely with the ideals of virtue argumentation. By practicing intellectual humility (recognizing that her initial self-judgments may be biased or exaggerated), open-mindedness (considering alternative viewpoints and evidence), and epistemic responsibility (basing her beliefs on sound reasoning rather than emotional reactivity), Harley can develop a more accurate and empowering sense of self.

Another example is Shuri, the brilliant princess of Wakanda. As a young woman in a male-dominated field, Shuri may sometimes struggle with imposter syndrome or self-doubt. She might find herself thinking things like, “I’m not really qualified to be in charge of this project,” “Everyone will see through me and realize I’m a fraud,” or “I have to be perfect and never make mistakes.”

CBT would encourage Shuri to challenge these distorted thoughts by looking for evidence to the contrary – remembering her past successes, the skills and knowledge she’s developed, and the respect and admiration she’s earned from her colleagues. She might practice cognitive reframing, replacing self-critical thoughts with more balanced and motivating ones like, “I have worked hard to get where I am and have valuable contributions to make,” or “Making mistakes is a normal part of the learning process and doesn’t negate my overall competence.”

By cultivating these habits of rational self-reflection and self-encouragement, Shuri can build resilience and maintain her confidence even in the face of stress and setbacks. And by modeling these virtues of intellectual humility, openness to feedback, and commitment to growth, she can inspire and empower others around her to do the same.

Ultimately, both CBT and virtue argumentation are about recognizing the power of our thoughts and beliefs to shape our realities, and taking responsibility for cultivating habits of mind that serve our well-being and our highest values. Whether we’re superheroes, royalty, or ordinary humans, we all face challenges and setbacks that can distort our thinking and strain our coping abilities.

Women and minorities in particular often face additional barriers and biases that can feed into negative self-talk and irrational argumentation. Characters like Harley Quinn and Shuri show us that it’s possible to overcome these challenges by committing ourselves to the lifelong practice of self-reflection, rational analysis, and principled reasoning. By developing the cognitive and emotional resilience we need to face adversity with wisdom, integrity, and grace, we can all learn to be the heroes of our own stories – one thought, one argument, one choice at a time.

So the next time you find yourself falling into patterns of self-doubt, remember the examples of these remarkable women. Ask yourself: What would Harley do to challenge those distorted thoughts and reclaim her sense of self-worth? How would Shuri practice intellectual humility and openness to growth in the face of imposter syndrome? By channeling the insights of CBT and the virtues of good reasoning, we can all cultivate the clarity, resilience, and inner strength to rise above our limitations and become the best versions of ourselves.

Virtue Argumentation and Political Polarization – Lessons from Lincoln and Oppenheimer

In our exploration of virtue argumentation and its applications, it’s crucial to consider how this approach might help us navigate one of the most pressing challenges of our time: political polarization. In an era where public discourse is increasingly characterized by tribalism, echo chambers, and bad-faith argumentation, the need for a more virtuous and principled approach to reasoning and debate has never been more urgent.

The film Lincoln offers a compelling case study in how the virtues of good argumentation can be brought to bear on political division and conflict. The movie, based on Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book Team of Rivals, depicts President Abraham Lincoln’s efforts to pass the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in the midst of the Civil War. Faced with fierce opposition from both his political opponents and members of his own party, Lincoln must find a way to build consensus and persuade others to support his cause.

Throughout the film, we see Lincoln embodying many of the key virtues of good argumentation. He demonstrates intellectual humility, recognizing that he doesn’t have all the answers and must rely on the wisdom and expertise of others. He practices empathy and perspective-taking, striving to understand the concerns and motivations of those who disagree with him. And he exhibits rhetorical skill and persuasiveness, crafting arguments that appeal to both the logic and the emotions of his audience.

Perhaps most importantly, Lincoln shows a deep commitment to the virtues of honesty and principled compromise. He refuses to engage in the kind of deceptive or manipulative tactics that some of his allies employ, insisting that the end goal of abolition must be pursued through legitimate and ethical means. At the same time, he recognizes that achieving this goal will require finding common ground and making difficult trade-offs. He’s willing to negotiate and make concessions where necessary, but never loses sight of his ultimate moral purpose.

In the end, it’s this combination of moral clarity and pragmatic flexibility that allows Lincoln to achieve his historic victory. By modeling the virtues of good argumentation and principled leadership, he’s able to navigate the complex political landscape and build the coalitions needed to bring about transformative change.

Another example of the power of virtuous argumentation in the face of political conflict can be found in the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist who led the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bomb during World War II. As depicted in the film Oppenheimer, Oppenheimer faced immense pressures and ethical dilemmas as he wrestled with the implications of his work and the rapidly changing political climate of the Cold War era.

Throughout his life, Oppenheimer demonstrated a deep commitment to the virtues of intellectual honesty, curiosity, and open-mindedness. He was known for his willingness to engage in rigorous debate and to change his mind in the face of new evidence or arguments. Even as he worked on a project of immense secrecy and national importance, he strove to foster a culture of scientific inquiry and collaboration among his colleagues.

At the same time, Oppenheimer was acutely aware of the moral dimensions of his work and the awesome responsibility that came with developing a weapon of such devastating power. He famously quoted the Bhagavad Gita after witnessing the first successful atomic test, saying, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” In the years that followed, he became an outspoken advocate for international arms control and opposed the development of the even more powerful hydrogen bomb.

Oppenheimer’s story illustrates the complex interplay between the virtues of good argumentation and the demands of political and moral responsibility. On the one hand, his commitment to intellectual honesty and open inquiry allowed him to push the boundaries of scientific knowledge and achievement. On the other hand, his willingness to grapple with the ethical implications of his work and to speak out against the dangers of unchecked nuclear proliferation put him at odds with some of the most powerful political forces of his time.

In the end, Oppenheimer’s legacy remains a subject of debate and interpretation. Some see him as a hero who helped end World War II and then worked tirelessly to prevent future nuclear catastrophe. Others see him as a tragic figure who unleashed the genie of atomic warfare and then struggled to put it back in the bottle. What is clear is that his story embodies both the potential and the limitations of virtuous argumentation in the face of political polarization and existential threat.

So what lessons can we draw from the examples of Lincoln and Oppenheimer for our own efforts to navigate the challenges of political division and social change? First and foremost, they remind us of the importance of cultivating the virtues of good argumentation – intellectual humility, empathy, honesty, and principled compromise – in our own lives and in our public discourse. By modeling these virtues and holding ourselves and others accountable to them, we can help to create a culture of more constructive and meaningful dialogue across differences.

At the same time, these examples also highlight the need for moral clarity and conviction in the face of complex and high-stakes challenges. As Lincoln and Oppenheimer both understood, the pursuit of truth and justice sometimes requires making difficult choices and taking principled stands, even when it means risking personal or professional consequences.

Ultimately, the practice of virtue argumentation is not a panacea for the deep-rooted problems of political polarization and social division. These challenges are complex and multifaceted, and will require sustained effort and commitment from all of us to address. But by embracing the virtues of good reasoning and ethical persuasion, we can begin to build the kind of trust, understanding, and common purpose that are essential for tackling the great challenges of our time.

Discussion Questions

- This chapter describes two main ways arguments can go wrong – confusing others through lack of virtue, or confusing ourselves through lack of skill. Which of these do you think is more common in public discourse today, and why? What examples come to mind?

- Emperor Palpatine is used as an example of a vicious arguer who exploits people’s emotions and biases. Can you think of a real-world public figure or media personality who employs similar rhetorical tactics? What makes their arguments effective, and how could they be countered?

- Martin Luther King Jr. accused white moderates of lacking empathy and a sense of moral urgency during the civil rights movement. Do you think this critique still applies to modern social justice debates? When is compromise and incremental change justified, and when is more radical, immediate action needed?

- The flat Earth documentary Behind the Curve is discussed as an example of how sincere but unskilled arguers can end up deeply confused. What role do you think the media and educational institutions should play in combating misinformation and promoting critical thinking skills?

- Atticus Finch is held up as a model of a virtuous and skilled arguer who combines moral courage with logical prowess. Who do you consider to be a real-world example of this ideal, and what qualities do they exemplify in their argumentation?

- The chapter suggests that good intentions aren’t enough for making sound arguments – a baseline level of skill is also necessary. How could schools, universities, or public education better equip citizens with the tools of effective reasoning and debate?

- Virtue argumentation is compared to cognitive behavioral therapy in its emphasis on cultivating rational, self-reflective habits of mind. Do you think this kind of “arguing with yourself” is a helpful tool for personal growth? What mental arguments or self-talk patterns do you find yourself falling into, and how could you challenge them?

- The stories of fictional characters like Harley Quinn and Shuri are used to illustrate how women and minorities may be especially vulnerable to irrational self-doubt and negative self-talk. How have you seen imposter syndrome or stereotype threat play out in your own life or the lives of people you know? What strategies help build resilience in the face of these challenges?

- Abraham Lincoln is praised for his commitment to principled compromise in the passage from virtue argumentation to political polarization. Is compromise always a virtue in politics, or are there times when it amounts to a betrayal of one’s values? How can we tell the difference?

- The physicist Robert Oppenheimer is described as embodying the potential and limitations of virtuous argumentation in the face of existential threats and political pressure. Looking at present-day global challenges like climate change or nuclear proliferation, what role do you think virtuous and skilled argumentation has to play in finding solutions? What else is needed besides good arguments to drive meaningful action on these issues?

Glossary

|

Virtue Ethics (Aristotle) |

An approach to ethics that emphasizes the development of good character traits, or virtues, as the foundation for moral behavior and decision-making. |

|

Eudaimonia |

The ultimate goal of human life according to Aristotle, often translated as happiness, well-being, or flourishing, achieved through the cultivation of virtue. |

|

Doctrine of the Mean |

Aristotle’s idea that virtues are the desirable middle ground between two extremes of excess and deficiency. |

|

Argumentative Virtues |

Positive character traits or habits of mind that promote clear, rigorous, and fair reasoning, such as open-mindedness, intellectual humility, and epistemic responsibility. |

|

Open-mindedness |

The willingness to sincerely consider new ideas and perspectives, even when they challenge one’s existing beliefs. |

|

Intellectual Humility |

The recognition that one’s knowledge and opinions are always subject to limitations, biases, and errors. |

|

Empathy in Argumentation |

The ability to genuinely understand and consider the feelings, experiences, and perspectives of others, especially those with whom one disagrees. |

|

Intellectual Perseverance |

The willingness to engage with difficult, complex ideas and arguments, even when it is cognitively challenging or unsettling. |

|

Epistemic Responsibility |

The duty to carefully evaluate the quality of information and sources used to form beliefs and make arguments. |

|

Ad Hominem Fallacy |

An argument that attacks the character of the person making a claim, rather than addressing the substance of the claim itself. |

|

Steel Man |

The practice of presenting an opponent’s argument in its strongest, most charitable form before offering a critique. |

|

Virtue Argumentation |

An approach to argumentation that emphasizes the role of character traits and intellectual virtues in promoting good reasoning and constructive dialogue. |

|

Vicious Argumentation |

Argumentation that aims to confuse, mislead, or overpower others through the use of fallacious reasoning, manipulation, or bad faith tactics. |

|

Fallacious Reasoning |

Arguments that rely on faulty logic, such as ad hominem attacks, false dichotomies, or appeals to emotion, rather than sound reasoning and evidence. |

|

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) |

A form of psychotherapy that focuses on identifying and changing unhelpful patterns of thinking and behavior to improve emotional well-being. |

|

Cognitive Distortions |

Exaggerated, overly negative, or irrational ways of interpreting reality that can perpetuate cycles of dysfunction and suffering. |

|

Cognitive Restructuring |

The process of identifying, challenging, and replacing negative automatic thoughts with more balanced, realistic perspectives. |

|

Intellectual Courage |

The willingness to face and critically examine ideas that may be threatening to one’s beliefs or worldview. |

|

Principled Compromise |

The practice of finding common ground and making concessions in the pursuit of a higher goal or value, without sacrificing one’s core principles. |

|

Imposter Syndrome |

A psychological pattern characterized by persistent self-doubt and fear of being exposed as a fraud, despite evident competence and achievements. |

References

This chapter was orignally based on ideas developed by Andrew Aberdein in a series of published article (see below), and by the responses to these articles. Here’s an (incomplete) list of some recent work on the topic of argumentation and virtue.

Aberdein, Andrew. 2021. “Was Aristotle a Virtue Argumentation Theorist?” In Essays on Argumentation in Antiquity, edited by Joseph Andrew Bjelde, David Merry, and Christopher Roser, 39:215–29. Argumentation Library. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70817-7_11.

Aberdein, Andrew, and Daniel H. Cohen. 2016. “Introduction: Virtues and Arguments.” Topoi 35 (2): 339–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-016-9366-3.

Aikin, Scott F., and John P. Casey. 2016. “Straw Men, Iron Men, and Argumentative Virtue.” Topoi 35: 431–40.

Bailin, Sharon, and Mark Battersby. 2016. “Fostering the Virtues of Inquiry.” Topoi 35: 367–74.

Cohen, Daniel H. 2017. “The Virtuous Troll: Argumentative Virtues in the Age of (Technologically Enhanced) Argumentative Pluralism.” Philosophy & Technology 30: 179–89.

———. 2019. “Argumentative Virtues as Conduits for Reason’s Causal Efficacy: Why the Practice of Giving Reasons Requires That We Practice Hearing Reasons.” Topoi 38 (4): 711–18.

Cohen, Daniel H., and George Miller. 2016. “What Virtue Argumentation Theory Misses: The Case of Compathetic Argumentation.” Topoi 35: 451–60.

Doury, Marianne. 2013. “The Virtues of Argumentation from an Amoral Analyst’s Perspective.” Informal Logic 33 (4): 486–509.

Drehe, Iovan. 2016. “Argumentational Virtues and Incontinent Arguers.” Topoi 35: 385–94.

Finley, Cassie. 2023. “From Virtue Argumentation to Virtue Dialogue Theory: How Aristotle Shifts the Conversation for Virtue Theory and Education*.” Educational Theory 73 (2): 153–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12571.

Gascón, José Ángel. 2015. “Arguing as a Virtuous Arguer Would Argue.” Informal Logic 35 (4): 467–87.

———. 2016. “Virtue and Arguers.” Topoi 35: 441–50.

Godden, David. 2016. “On the Priority of Agent-Based Argumentative Norms.” Topoi 35: 345–57.

Kidd, Ian James. 2020. “Martial Metaphors and Argumentative Virtues and Vices.” In Polarisation, Arrogance, and Dogmatism, 25–38. Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429291395-4/martial-metaphors-argumentative-virtues-vices-ian-james-kidd.

Oliveira de Sousa, Felipe. 2020. “Other-Regarding Virtues and Their Place in Virtue Argumentation Theory.” Informal Logic 40 (3): 317–57.

Thorson, Juli K. 2016. “Thick, Thin, and Becoming a Virtuous Arguer.” Topoi 35 (2): 359–66.