4 Movie Villains Explain Fallacies of Weak Induction

A Little More Logical | Brendan Shea, PhD

Learning Outcomes: By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify and explain the key fallacies of weak induction, including hasty generalization, false cause fallacies (post hoc ergo propter hoc, slippery slope, gambler’s fallacy), and appeals to unqualified or biased authority.

- Recognize and analyze these fallacies in real-world contexts, such as media, politics, health and nutrition, and personal relationships.

- Apply the principles of strong inductive reasoning, such as representative sampling, consideration of confounding variables, and reliance on credible expertise, to avoid fallacies in your own thinking and decision-making.

- Understand and appreciate the role of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in establishing causal relationships and overcoming the limitations of anecdotal evidence and cognitive biases.

- Engage with the ideas of philosopher Hannah Arendt to deepen your understanding of how fallacies of weak induction can contribute to the rise of totalitarianism, the “banality of evil,” and the manipulation of public opinion through propaganda.

Keywords: Fallacy of weak induction, Hasty generalization, Appeal to anecdotal evidence, Converse accident, Small sample, Unrepresentative sample, Suppressed evidence, False cause fallacy, Post hoc ergo propter hoc, Slippery slope, Gambler’s fallacy, Appeal to unqualified authority, Appeal to biased authority, Randomized controlled trial (RCT), Placebo, Blinding, Confounding variable, Treatment group, Control group, Phase 1 trial, Phase 2 trial, Phase 3 trial, Phase 4 trial, Hannah Arendt, Banality of evil, Totalitarianism, Propaganda, Lying world of consistency, Supersense

The Joker Explains Hasty Generalization

You’re in for a treat. I’m the Joker, Gotham’s resident agent of chaos and mastermind behind some of the most bewildering capers you’ve ever seen. You know, the pale-faced, green-haired guy with a penchant for jokes and anarchy. Batman’s favorite sparring partner, if you will. But enough about me, let’s talk about something even more intriguing: hasty generalizations.

Hasty Generalization is like throwing a dart with a blindfold; you make a broad conclusion based on limited, often insufficient data. It’s the bread and butter of lazy thinkers. You see one or two instances and voila, you think you’ve got the whole picture. It’s like saying all clowns are maniacal just because you met me. Tempting, but oh, so incorrect!

Some variants of this fallacy include:

- Appeal to anecdotal evidence. Oh, I love a good story, don’t you? This fallacy’s about using personal tales instead of cold, hard facts. Imagine ol’ Harv Dent tells you about a coin landing heads up ten times in a row, and suddenly you think every flip’s gonna be heads! It’s like taking one wild night in Gotham and saying the whole city’s a circus. Hilarious, but oh, so misleading

- Converse Accident. Converse accidents are like assuming that because I haven’t set off any fireworks lately, my smile truly means peace. Basically, the fallacy involves deciding that a “special case” is actually a “rule.” Don’t let the lack of explosions fool you! Just because I’m not actively causing chaos doesn’t mean I’m not planning something spectacular. My mind is a constant carnival of mischief, even when my face is in repose. Remember, the calm before the storm is often the most ominous.

- Small Sample. Basing conclusions on a small sample is like judging all of Gotham’s lawyers based on Harvey Dent. Now, don’t get me wrong, Harvey was a fine prosecutor and all, but assuming all lawyers share his noble ideals is like assuming all clowns have a heart of gold. Just remember, sometimes the most dangerous individuals wear the most respectable masks.

- Unrepresentative Sample. Judging all of Gotham based on the residents of Arkham Asylum is like saying everyone in a disco ball is a dancer. Sure, there are some truly twisted individuals within those walls, but they’re hardly representative of the average Gothamite. You’ll find plenty of ordinary people going about their lives, oblivious to the madness that lurks beneath the surface.

- Suppressed Evidence. This fallacy involves ignoring or omitting relevant information that contradicts your argument. It’s like the GCPD showcasing their successful arrests while ignoring their botched cases. ‘Gotham’s Finest, always catching the bad guys’ – except when they’re not. Selective storytelling at its finest!

Taking advantage of these fallacies is one of my favorite pastimes! You see, it’s all about understanding the psyche of Gotham’s citizens and manipulating it to my advantage. Let me peel back the curtain on some of my more… entertaining endeavors.

- With just a few strategically executed misdeeds, I can send the entire city into a frenzy. For instance, by targeting influential figures in high-profile, shocking ways, I create a narrative of unpredictability and terror. People start to generalize that no one is safe, that chaos reigns supreme. They don’t need to see a crime on every corner; just the thought that it could happen is enough to send shivers down their spines. Think of me the next time you let a “true crime story” influence the way you vote or act.

- Gotham is a city rife with underlying tensions and prejudices. By playing into these, I amplify existing stereotypes. For example, if I stage a crime in a certain neighborhood and leave behind evidence suggesting a particular group’s involvement, the city’s quick to blame the whole group. It’s a simple matter of nudging people’s existing biases a bit further. Hasty generalization plays a role in many types of bias, including racism, sexism, and various types of religious discrimination.

- Of course, I’ve also fallen for this fallacy myself. There was a time when I underestimated young Robin, thinking him just a sidekick, a mere extension of Batman. How delightfully wrong I was! That boy wonder turned out to be quite the thorn in my side, proving that even I can sometimes be guilty of oversimplifying things.

In essence, the power of hasty generalizations lies in their ability to create a narrative far beyond the reality of the actions. It’s not about the scale of the crime, but the story it tells and the fear it instills. And fear, my dear reader, is a potent tool in the hands of a skilled artist like myself. It’s not just about the killings; it’s about the story they tell and the shadows they cast in the minds of the people. And in those shadows, I find my greatest power.

Hasty Generalizations in Real Life

Now let’s bridge the gap between Gotham and your everyday life. You see, hasty generalizations aren’t just the playthings of a fictional villain like me; they’re very much a part of your real world, too.

Media and Public Perception. Just as I use a few chaotic acts to paint Gotham as a city teetering on the brink of disaster, your media often uses isolated incidents to shape public perception. Sensational news stories can lead people to overestimate the prevalence of certain crimes or risks. This can influence everything from public policy to individual behavior — a little like how a true crime story might sway your voting choices or personal safety measures.

Social Stereotypes and Prejudices. Reflect on how, in Gotham, I exploit existing prejudices for my schemes. In your world, hasty generalizations are at the root of many social biases. When people form opinions about entire groups based on limited interactions or media portrayals, it can lead to racism, sexism, religious discrimination, and more. These generalizations, just like the ones I provoke in Gotham, can cause real harm, leading to unfair treatment and policy decisions.

Personal Relationships. Consider my underestimation of Robin. In your lives, hasty generalizations can impact personal and professional relationships. Misjudging someone based on first impressions or hearsay can lead to missed opportunities and unjust treatment. It’s crucial to remember that individuals are more complex than a single story or appearance suggests.

The real trickery of hasty generalizations is their subtlety. They slip into your thoughts and decisions without the pomp and flair of my crimes in Gotham, but their effects can be just as dramatic. They shape your view of the world, influence how you treat others, and can even dictate major life decisions.

Strong vs Hasty Generalizations (Table)

|

Dimension |

Strong Generalization |

Hasty Generalization |

|

Evidence Quality |

High-quality, well-researched evidence. For example, a comprehensive study showing trends in crime rates over a decade in multiple cities. |

Limited or anecdotal evidence. E.g., using a single high-profile crime event to generalize about the safety of an entire city. |

|

Sample Size and Diversity |

Large and diverse samples that are representative. For instance, analyzing crime data from various neighborhoods, demographics, and times to draw conclusions about crime trends. |

Small, non-representative samples. Like concluding that a neighborhood is dangerous based on a few isolated incidents. |

|

Consideration of Context |

Thoroughly considers the context and contributing factors. Such as understanding the socio-economic and cultural factors behind organized crime trends in a region. |

Overlooking or ignoring context. For example, attributing a rise in crime solely to policy changes without considering economic downturns or other social factors. |

|

Methodological Rigor |

Utilizing scientifically sound and systematic methods. This includes longitudinal studies to ascertain patterns in terrorism and its root causes. |

Using flawed or simplistic methodologies. Like basing an entire theory of criminal behavior on sensationalized media reports or isolated case studies. |

|

Consistency with Other Data |

Aligns with and is corroborated by other data and research. For instance, aligning theories of cybercrime proliferation with technological advancements and global trends. |

Conflicts with or ignores existing data and research. Such as claiming a surge in violent crime without considering nationwide statistics showing a downward trend |

Discussion Questions

- How can we distinguish between a legitimate generalization and a hasty generalization?

- What are the potential consequences of relying on hasty generalizations?

- How can we avoid falling victim to hasty generalizations in our own thinking?

- How do media and public perception contribute to hasty generalizations?

- How do hasty generalizations play a role in perpetuating social stereotypes and prejudices?

- How can hasty generalizations negatively impact personal relationships?

Nurse Ratched Explains False Cause Fallacies

Hello, I’m Nurse Ratched, the steadfast overseer of the mental ward in the novel (and movie) One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s nest. I’m known for my strict rules and my commitment to order and control. Everyone (patients, families, and doctors) is afraid of me, basically, and I can make people do whatever I want to them as a result. Now, let’s talk about something that disrupts the logical order of things just as much as a chaotic patient: false cause fallacies.

False Cause Fallacies occur when a causal connection is assumed between two events when none actually exists. It’s like assuming that because a patient shows improvement after taking a new medication, the medication must be the cause, without considering other factors.

- Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc—This Latin phrase means “after this, therefore because of this.” It’s when one assumes that because one event followed another, the first must have caused the second. It’s like saying a patient’s recovery is due solely to my strict regime, without considering other therapeutic factors.

- Slippery Slope—This is the belief that a small initial action will lead to a chain of events culminating in a much larger, usually negative, result. It’s like suggesting that allowing patients one small liberty will inevitably lead to complete anarchy in the ward.

- Gambler’s Fallacy—This fallacy occurs when someone believes that past events can influence the probability of something happening in the future, despite each event being independent. For instance, thinking a patient is ‘due’ for a breakthrough in therapy because they’ve had no progress for a while is a classic example of the gambler’s fallacy.

In my ward, just as in logic, it’s crucial to distinguish between what merely appears to be true and what is actually true. False cause fallacies can lead to dangerous misjudgments, both in treating patients and in reasoning about cause and effect in the wider world.

A skilled villain (such as myself) can do quite a bit with the skillful exploitation of these fallacies.

Exploiting the Vulnerability of Family Members (Post Hoc Fallacy). When a patient shows any sign of improvement after I implement a new, strict policy or medication regime, I promptly meet with their family members. I skillfully attribute this improvement solely to my recent interventions. By doing so, I exploit the family’s desperate need for hope and their limited understanding of medical and psychological complexities. They’re often emotionally exhausted and willing to grasp at any sign of progress, making them vulnerable to my authoritative assertions. I paint a picture where my methods are the sole beacon of hope, thereby increasing their reliance on my judgment and quashing any doubts they might have about my methods.

Maintaining Control Over Patients (Slippery Slope Fallacy). I often use the slippery slope fallacy to instill fear and maintain discipline among patients. For instance, I might suggest that a small act of non-compliance, like questioning a rule, could lead to severe repercussions such as isolation, increased medication, or even indefinite extension of their stay. This tactic preys on the patients’ fears of losing their already limited freedoms and the unknown consequences of defiance. By amplifying the potential outcomes of minor infractions, I create a state of constant anxiety and compliance. Patients start policing not only their actions but also their thoughts, internalizing the belief that any step out of line could lead to catastrophic consequences. Many people with anxiety are already prone to “slippery slope” thinking—I just make it that much worse.

Cementing My Authority with Supervisors (Gambler’s Fallacy). To maintain my authority and methods unchallenged, I sometimes suggest to my supervisors that a particularly difficult patient is ‘due’ for a breakthrough because of their prolonged resistance to treatment, implying that my continued strict approach will eventually yield results. This plays into the common misconception that a change is inevitable merely because it hasn’t happened yet, ignoring the randomness and complexity of human behavior. By presenting my approach as the only logical path to an imminent breakthrough, I exploit my supervisors’ desire for efficiency and results. This not only reinforces my authority but also deflects any scrutiny or criticism of my methods.

False Cause Fallacies in the Real World

The tendrils of false cause fallacies extend beyond the confines of my ward and into your everyday lives. Understanding these fallacies is crucial, as their misapplication can lead to serious misjudgments and errors in various aspects of society.

In Healthcare and Medicine. Just as I might attribute a patient’s improvement solely to my strict regime, in the real world, similar fallacies occur. For instance, people might assume a new health trend or supplement is effective because of a few anecdotal success stories, without considering placebo effects or other contributing factors. This leads to misguided health choices and can overshadow evidence-based medical practices.

In Politics and Policy Making. The slippery slope fallacy is not just a tool for instilling fear in my patients; it’s often used in political rhetoric. Policy makers and lobbyists might argue that a minor legislative change could lead to extreme outcomes (like suggesting that small gun control measures will lead to a total ban on firearms), influencing public opinion and policy based on fear rather than rational debate.

In Financial Decisions (Gambler’s Fallacy). In the financial world, the gambler’s fallacy can lead to poor investment decisions. Investors might believe that a stock is ‘due’ for a rise or fall based on past performance, ignoring market complexities and leading to potentially disastrous financial choices.

In Personal Relationships. Relationships often suffer from these fallacies. For instance, one might believe that a small disagreement will inevitably lead to a relationship’s end (slippery slope), or attribute a partner’s mood to a single action without considering other stressors (post hoc). This can lead to misunderstandings and unnecessary conflicts.

In Education and Child Development. Educators and parents might fall for these fallacies too. For example, assuming a child’s success or failure is solely due to one factor, like a particular teaching method or parenting style (post hoc), without considering the child’s individual needs or external influences.

In real life, just as in my ward, these fallacies can shape perceptions, decisions, and actions in profound ways. They can lead to erroneous conclusions, influence public opinion, and even dictate policy. Recognizing and questioning these fallacies is crucial for rational decision-making, whether you’re running a mental ward, governing a city, or navigating your personal life. Just as I manipulate these fallacies to maintain control and order, they can be manipulated in your world too, often with significant consequences.

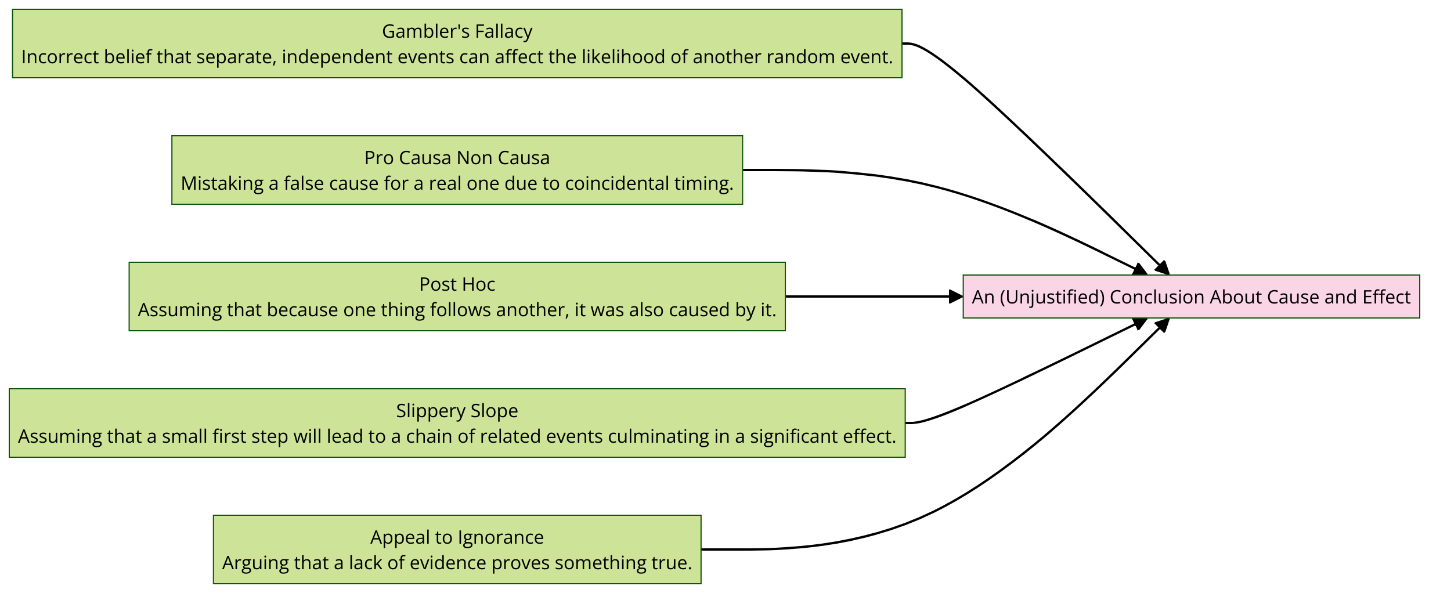

Graphic: Causes of Bad Causal Reasoning

Good vs Fallacious Causal Inference (Table)

|

Dimension |

Strong Causal Inference |

Weak Causal Inference |

|

Evidence Quality |

High-quality evidence from multiple, reliable sources. For example, well-conducted longitudinal studies showing a consistent link between certain life experiences and specific mental health conditions. |

Poor-quality or anecdotal evidence. E.g., a single case study hastily generalizing a new therapy’s effectiveness without considering other variables. |

|

Sample Size and Representation |

Large, diverse, and representative samples providing a comprehensive view. For instance, a study encompassing various demographics to understand the prevalence of depression. |

Small, non-representative samples leading to overgeneralizations. Like concluding a treatment is universally effective based on its success in a specific, homogenous group. |

|

Consideration of Confounding Variables |

Thorough consideration and control of confounding variables. For example, accounting for socio-economic status, genetics, and environmental factors when studying the efficacy of a psychiatric medication. |

Ignoring or overlooking potential confounding variables. Such as attributing improved patient well-being solely to medication, without considering therapy, lifestyle changes, or placebo effects. |

|

Methodological Rigor |

Employing rigorous, scientifically sound methods. This includes randomized control trials (RCTs) to ascertain the effectiveness of a new therapy method. |

Using flawed or biased methodologies. For instance, relying solely on self-reported data without cross-verification to establish a treatment’s success. |

|

Consistency with Existing Knowledge |

Aligns with and is supported by existing scientific understanding and literature. E.g., a study on depression that aligns with established psychological theories and previous research findings. |

Conflicts with or lacks consideration of existing scientific knowledge. Like a new theory that claims a revolutionary understanding of schizophrenia but contradicts established medical consensus. |

Discussion Questions

- Identify and explain the three types of false cause fallacies discussed in the text: Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, Slippery Slope, and Gambler’s Fallacy. Provide real-world examples of each type of false cause fallacy.

- Compare and contrast strong causal inferences with weak causal inferences, as outlined in the table.

- Describe the potential dangers of relying on false cause fallacies in decision-making.

- How can we avoid falling victim to false cause fallacies in our own thinking?

- Discuss the importance of considering alternative explanations and evidence before forming conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships.

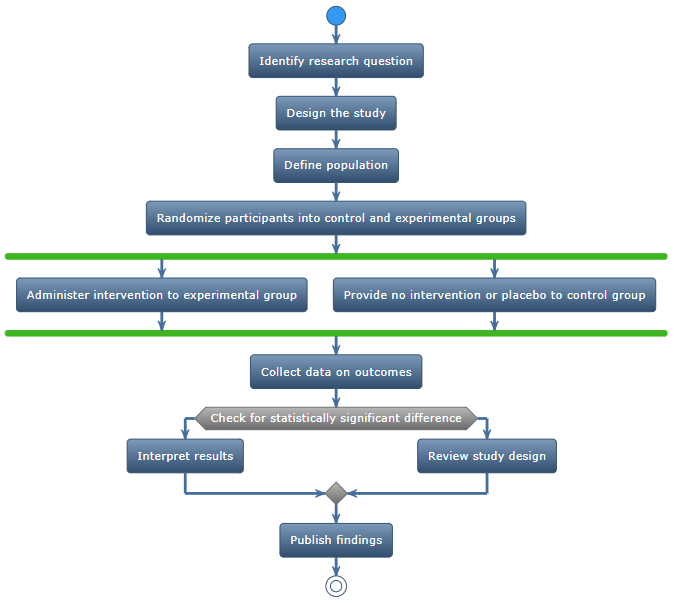

Randomized Control Trials: Avoiding Fallacies in the Real World

In the fictional worlds of villains like the Joker and Nurse Ratched, hasty generalizations and false cause fallacies are tools of manipulation and control. The Joker might use a single, dramatic crime to make Gotham believe the city is descending into chaos, while Nurse Ratched might attribute a patient’s improvement solely to her harsh methods. But in the real world, we have a powerful tool to avoid these pitfalls: the randomized control trial (RCT).

Understanding Randomized Control Trials An RCT is a type of scientific experiment that tests the effectiveness of a treatment or intervention while minimizing bias and confounding variables. Imagine the Joker wanting to test a new laughing gas. He might randomly divide a group of henchmen into two: one group gets the gas (the treatment group), while the other gets regular air (the control group). By comparing the two groups, he can see if the gas really causes uncontrollable laughter, or if it’s just a coincidence (a hasty generalization).

Key features of an RCT include:

- Participants are randomly put into different groups, usually a treatment group (getting the intervention) and a control group (getting no intervention or a placebo). This ensures the groups are similar at the start.

- The control group provides a baseline for comparison. In the Joker’s case, the henchmen not getting the laughing gas are the control. Sometimes the control group receives a placebo (a “sugar pill” that is inactive, but “looks like” the real treatment).

- Ideally, neither participants nor researchers directly involved know who is in which group during the trial (this is called double-blinding). This reduces bias. The Joker might have an assistant administer the gas without knowing which is which.

RCTs are powerful tools against hasty generalizations and false cause fallacies. Let’s see how:

- By randomly assigning a large, diverse group of participants, RCTs avoid conclusions based on too small or biased samples. The Joker might want to test his gas on a variety of henchmen, not just a few who might have quirky reactions.

- RCTs try to make groups as similar as possible, so the only expected difference is the treatment itself. This prevents falsely attributing effects to the treatment that are really caused by other cofounding factors – unlike Nurse Ratched blaming her methods for changes in patients that may have many causes.

- Carefully defined, measurable outcomes and statistical analysis in RCTs avoid subjective judgments or assumptions of cause-and-effect based simply on one event following another (post hoc fallacy). The Joker would need to clearly define what counts as ‘uncontrollable laughter’ and make sure he isn’t fooled by chance timing.

RCTs are crucial in testing new medical treatments, from drugs to surgeries. They typically involve a series of phases:

- Phase 1: Small trials focused on safety, usually in healthy volunteers. Think of it as the Joker making sure his new gas doesn’t have unexpected side effects on a few henchmen first.

- Phase 2: Larger trials testing efficacy and side effects in people with the condition being treated. Here, the Joker might test if the gas works on a bigger group of targets.

- Phase 3: Large-scale trials comparing the new treatment to existing ones. These often involve hundred to thousands of different subjects. The Joker would want to know if his laughing gas is better than his old joke-shop gags.

- Phase 4: Post-approval studies monitoring long-term safety and effectiveness. Even after the Joker starts using his gas, he’d need to watch for long-term effects.

Throughout these phases, RCTs help ensure that conclusions about the treatment’s effects are based on sound, unbiased evidence, not hasty generalizations from anecdotes or false assumptions of causality.

While powerful, RCTs have limits. They can be costly and time-consuming, and not always practical or ethical – randomly denying potentially beneficial treatment can be problematic. Even the Joker might hesitate to withhold a life-saving antidote from half his gang for the sake of an experiment. Researchers must balance scientific rigor with participant welfare.

In the end, though, randomized control trials are a vital safeguard against the kinds of hasty generalizations and false cause fallacies that villains like the Joker and Nurse Ratched exploit. By promoting representative sampling, controlling for confounding variables, and enabling objective causal inferences, well-designed RCTs bring us closer to truth – whether we’re testing laughing gas or life-saving medications. As we navigate a complex world, being aware of these fallacies and appreciating tools like RCTs is crucial for clear thinking and sound decisions. So the next time you see a news headline or hear a politician’s claim, ask yourself: is this a hasty generalization, a false cause fallacy, or a conclusion based on rigorous, controlled study? The answer makes all the difference.

Graphic: Randomized Control Trials

Darth Vader Introduces Appeals to Unqualified or Biased Authority

Greetings. I am Darth Vader, once known as Anakin Skywalker, now a Dark Lord of the Sith and enforcer of the Galactic Empire’s might. In my journey from a Jedi Knight to the embodiment of the Sith, I have learned the power and danger of authority, and how it can be wielded or misused. Now, let me introduce you to the fallacy of appeals to unqualified or biased authority, a concept as intriguing as the Force itself.

In the vastness of the galaxy, much like in your world, knowledge often comes from authorities. These could be experts in their fields, leaders, or institutions renowned for their insights. However, not all appeals to authority are valid.

An appeal to unqualified or biased authority is a logical fallacy that occurs when an argument relies on the opinions or expertise of individuals who have no legitimate authority on the matter at hand. It’s like consulting a droid on matters of the Force — ineffective and illogical. Main subtypes of the fallacy include:

- Appeal to Unqualified Authority—This occurs when the authority in question, though respected, lacks expertise in the relevant area. For instance, a famous holofilm star giving advice on complex intergalactic politics would be akin to a stormtrooper discussing the subtleties of lightsaber combat — out of their depth and expertise.

- Appeal to Biased Authority—In this case, the authority might be an expert, but they have a bias that skews their judgment. It’s like asking Emperor Palpatine about the benefits of going to the “dark side” of the force versus staying with the “light side.” While he is definitely about the Force, he has an interest in making you choose the dark side.

Remember, while it is natural to seek knowledge from authorities, it’s critical to assess their qualifications and biases. Just as the Empire often uses propaganda and skewed information to maintain control, authorities in your world can also present biased or unqualified views as facts. In your pursuit of knowledge, be as discerning as a Sith seeking truth in the shadows, and as cautious as a Jedi guarding against the Dark Side.

Obi-Wan or Palpatine? Trusting the Right People

In a galaxy rife with conflict and deception, determining whom to trust is a matter of utmost importance, often having profound implications. My experiences with two pivotal figures, Obi-Wan Kenobi and Emperor Palpatine, starkly illustrate this challenge.

Obi-Wan Kenobi was a Jedi Master and my mentor, who guided me through much of my early life. He was a stalwart adherent to the Jedi Code, a skilled warrior, and a wise counselor. Our relationship was complex, marked by respect and, at times, tension, as I struggled with the constraints of the Jedi teachings. Emperor Palpatine, by contrast, was the Sith Lord who lured me to the Dark Side. He presented himself as a wise and benevolent guide, offering knowledge and power beyond the reach of the Jedi. Our relationship was built on manipulation, with Palpatine exploiting my fears and ambitions.

In retrospect, there were a number of good reasons for trusting Obi-Wan Kenobi over Palpatine:

- Obi-Wan’s teachings and advice were consistent with those of other respected authorities, such as the Jedi Masters. This alignment with a broader, respected tradition of knowledge—part of the “science” of my world—lent credibility to his guidance.

- Unlike Palpatine, Obi-Wan did not seek personal gain from his teachings. His guidance was grounded in a genuine desire to uphold the Jedi principles and to support the greater good, even at personal cost.

- Transparency and Consistency. Obi-Wan’s counsel was transparent and consistent. He did not shroud his teachings in deceit or alter his principles to suit the situation, which is indicative of a trustworthy authority.

- Obi-Wan’s guidance was often based on empirical evidence and observable truths that I could “check” if I wanted, as opposed to Palpatine’s reliance on manipulation and deceit.

My journey—from the light side of the force to the dark side and back again—underscores the importance of critically evaluating the sources of guidance one chooses to follow. Obi-Wan represented a trustworthy authority, grounded in a tradition of knowledge, integrity, and a commitment to the greater good, whereas Palpatine embodied manipulation and personal ambition. The lesson here extends beyond the stars of my galaxy to your own lives: scrutinize the motivations, alignment with respected knowledge, and moral standing of those you choose to trust. This careful consideration is crucial in navigating the complex tapestry of influences that shape your path.

The Emperor Strikes Back: Palpatine on How to Mislead and Manipulate

I am Emperor Palpatine, the architect of the Galactic Empire, and I think the previous section doesn’t quite do me justice. My dominion extends far beyond mere military might; it is rooted in the strategic manipulation of authority, a tactic resonant with some of Earth’s most infamous dictators. The key to my reign lies not just in the exertion of power, but in the artful subversion and consolidation of authority. Appeals to inappropriate or biased authority are my bread and

To secure my position, I first focused on undermining existing pillars of authority. The Jedi, with their deep-rooted spiritual and moral influence, posed a significant challenge. Like Stalin’s approach to the Church, I systematically discredited and dismantled the Jedi Order, painting them as traitors and erasing their influence from public consciousness. This strategy was not limited to the Jedi; I extended it to all realms of thought and information. Science and intellectualism, potential breeding grounds for dissent, were tightly controlled and redirected to serve the Empire’s ends, mirroring Mao’s suppression of intellectualism during China’s Cultural Revolution. Furthermore, akin to Putin’s Russia, I ensured the media became a tool of the state, disseminating only Empire-approved narratives, effectively quashing free press and speech.

But dismantling existing authorities was only half the battle. Establishing myself as the ultimate authority was crucial. I crafted a cult of personality, omnipresent and commanding, instilling a sense of stability and order. This move paralleled the tactics of leaders like Hitler, where the leader’s image becomes synonymous with the state. I also centralized power, ensuring that all governance and decision-making were dependent on me, reminiscent of Stalin’s totalitarian regime. Such consolidation left no room for other authorities, making the Empire and its people wholly reliant on my will.

My rule was further cemented through propaganda and misinformation. By controlling the narrative, I shaped the Empire’s perception of truth, a tactic used by many totalitarian regimes to maintain power. This manipulation created a populace that looked to me as the sole source of information, guidance, and even basic necessities, much like Mao’s control over China. Through these means, I created an environment where the Empire’s dependence on my authority was absolute, rendering any form of dissent or resistance futile.

My reign as Emperor is a testament to the power of authority manipulation. By undermining traditional sources of authority and positioning myself as the singular guiding force, I established an unassailable regime. This approach, echoing the methods of Earth’s totalitarian rulers, underscores the profound impact of authority in shaping and controlling societies. My rule is not just a demonstration of power; it is an orchestrated symphony of control, influence, and absolute authority.

Trustworthy vs Untrustworthy Authorities (Table)

|

Metric |

Trustworthy Authorities |

Untrustworthy Authorities |

|

Expertise and Credentials |

Possess relevant expertise and credentials in their field. For example, a climate scientist discussing climate change based on years of research and study. |

Lack relevant expertise or credentials. E.g., a celebrity or politician without scientific training asserting opinions on complex scientific issues. |

|

Bias and Objectivity |

Strive for objectivity and acknowledge their biases. They present information based on evidence, like a researcher disclosing potential conflicts of interest while discussing medical advancements. |

Display clear biases or vested interests that skew their perspective. For instance, a business leader denying environmental issues due to their investment in fossil fuels. |

|

Consistency with Established Knowledge |

Their statements and views align with established knowledge and consensus. An example is a historian accurately representing historical events in line with academic consensus, even if it’s politically sensitive. |

Often contradict established knowledge without credible evidence. For example, promoting conspiracy theories that go against historical facts or scientific understanding. |

|

Transparency in Sources |

Cite transparent, verifiable sources for their information. A trustworthy journalist, for instance, uses credible sources and verifiable data when reporting on political issues. |

Use unverifiable, obscure, or non-transparent sources. An example would be a political pundit citing anonymous sources or unverified ‘facts’ to support a divisive narrative. |

|

Accountability and Correction |

Willing to be held accountable and correct mistakes. A reliable authority in any field, like a respected news organization, will issue corrections and updates when errors are made in reporting. |

Resist accountability and refuse to correct misinformation. For example, a political figure or group continuing to spread disproven information without acknowledging errors. |

Discussion Questions

- Explain why relying on unqualified or biased authorities can be dangerous and misleading.

- Discuss the similarities and differences between appeals to unqualified or biased authority in your world and the galaxy depicted in the text.

- Describe strategies for evaluating the qualifications and potential biases of authorities before accepting their claims as true.

- How can individuals be more discerning consumers of information in an age of widespread propaganda and misinformation?

- Discuss the ethical implications of using appeals to unqualified or biased authority, especially in fields like politics, media, and advertising.

More Villains on Their Favorite Fallacies

Cruella de Vil Explains Appeal to Vanity. “Darlings, it’s Cruella de Vil here, the epitome of style and sophistication. Now, let’s talk about my favorite fallacy: the Appeal to Vanity. It’s all about flattering one’s self-love to sway opinions. For instance, imagine convincing someone to join a cause by telling them it’s only for the most elite and fashionable individuals. They’re so caught up in feeling superior and stylish that they fail to question the cause itself. It’s deliciously deceptive and oh-so-chic!”

Thanos Explains Fallacies of Composition and Division. “I am Thanos, the wielder of the Infinity Gauntlet. The Fallacies of Composition and Division are particularly intriguing. These involve assuming what’s true for a part is true for the whole, or vice versa. Consider this: just because each individual person might find it beneficial to use “a bit more resources like gasoline”, it doesn’t mean that this helps society, and in fact might lead to ecological collapse. It’s a fallacy I’ve seen many succumb to, failing to understand the complexity of ecosystems at a universal scale.”

Scar Explains Appeal to Force. “Greetings, I am Scar, the brains behind the coup of Pride Rock. The Appeal to Force is a fallacy I hold dear. It involves using threats or the prospect of harm to sway opinions. Imagine this: I convince the hyenas to support my ascension to the throne not by logical argument, but through the implicit threat of what might happen if they don’t. It’s not the strength of the argument that wins them over, but the fear of crossing me. In the grand circle of life, might often makes right, or at least it convinces others you’re right.”

Loki Explains Appeal to Ignorance . “Loki here, Asgard’s most misunderstood genius. My favorite fallacy is the Appeal to Ignorance. It’s about exploiting what others don’t know. For instance, convincing the people of Midgard (Earth) of my divinity, simply because they can’t prove otherwise. This fallacy plays beautifully into the hands of someone like me, who thrives in the shadows of uncertainty and mystery. After all, in the absence of certainty, a cunning word can be mightier than the strongest scepter.”

The Wicked Witch of the West Explains False Dichotomy. “I am the Wicked Witch of the West, the terror of Oz. My preferred deceptive tool? The False Dichotomy. It involves presenting two opposing options as if they are the only ones available. Take, for example, telling Dorothy, ‘Either surrender the ruby slippers or face my wrath.’ This narrows her world to two choices, hiding other possible options and strategies she might employ. It’s a powerful way to limit someone’s thinking and control their next move.”

Sample Problems: Reasoning About Diets

Fallacies of weak induction can be tough to avoid. However, they can have big consequences for our lives. For example, here are some fallacies of weak induction related to diet and health:

|

Passage |

Analysis |

|

Dr. Oz says that I can lose weight by eating garcinia extract. Since he’s a doctor, I should do what he says. |

Appeal to Inappropriate Authority. While Dr. Oz may be a doctor, he isn’t the only doctor, and his opinion hardly represents a consensus of experts. If you wanted to know what to think of this claim, you’d want to do some research and see the *consensus* view on this. (In the case of nutrition, the scientific consensus is usually reflected in publications by government agencies like the Food and Drug Administration, major medical institutions like Mayo Clinic or Cleveland Clinic, and by diet recommendations of groups like the American Heart Institute.) |

|

Six weeks ago, I cut gluten (or meat, or milk, or whatever) from my diet, and look how much weight I’ve lost, and how much better I feel. I can only conclude that [specific food item x] was the cause of my weight gain or ill health. |

False Cause (non causa pro causa/post ergo propter hoc). The case of diets provides an especially clear example of how this fallacy. It can seem obvious to people that the most recent diet they’ve engaged in was “the cause” of their weight loss. However, this is almost always an unjustified conclusion, since there are things happening besides merely cutting out this food item that might bear a causal relationship to the weight loss (for example, people might just be eating less food, or have changed their exercise habits, etc.). This is why things like scientific studies are so important. |

|

I lost 10 pounds in the first two months of my diet. So, I can reasonably expect to lose 50 pounds over the next 10 months. |

Hasty Generalization. The first two months of a new diet are *not* an unbiased sample of what the future holds. In most cases, people will put on much of the weight they’ve lost. |

|

In a study of mice, a group of mice that were forced to fast for 12 hours a day lived 20% longer than mice that ate all. [Implicit: humans are mice are similar in that they are mammals, etc.] Therefore, I could extend my life span by 20% by fasting for 12 hours a day. |

Weak Analogy. The weak analogy here is between mice and humans. The problem is not that we can’t learn anything from studying mice (we can!), but that it’s unlikely that an individual human will respond precisely the same way the mice do (as this argument claims). This argument ignores these differences between humans and mice, and then proceeds to make a very strong claim about what will happen to a certain human. If the conclusion were weaker (“it might improve my health to take a break from eating now and again”) the argument itself would be stronger. |

|

My physician said that my cholesterol was very high, and that I should consider changing my diet. I talked to a nutritionist who agreed. They told me I should consider following the “DASH diet.” So, my health will improve if I do this. |

No fallacy. Note that, because of the inductive nature of this argument, you still might be wrong about the conclusion! And it may well be that new evidence will eventually cause you to revisit this conclusion. However, it is reasonable to act on this evidence (expert advice rooted in scientific consensus). |

|

There’s lots of scientific disagreement about diets, and no one has conclusively shown the best diet. So, who are you to say that my diet of “eat all the doughnuts, all the time” is bad? |

Appeal to Ignorance. It’s true that many questions about nutrition (and with science generally) are unsolved. It’s also true that there’s no way of mathematically proving that any crazy diet idea won’t work. However, this does NOT mean that the evidence supports all diets equally or that we don’t have solid evidence against your crazy diet. |

|

Lots of people I’ve talked to said they lost weight after stopping eating food item F. I also read many stories of people on the internet who did the same thing. Obviously, everyone could lose weight by doing this. |

Hasty Generalization. For any given popular diet (including many entirely at odds with one another), you can almost certainly find anecdotal evidence to support it via the testimony of friends, social media, news stories, your own experience, etc. However, gathering data in this way is highly biased (since you are almost sure to encounter many more stories of successes than failures.). |

|

I saw a news article about a scientific study that provided some support for diet X. Hence, that diet is clearly the way to go! |

Suppressed Evidence. As is the case with many other issues, there are a LOT of studies on nutrition. While new studies are relevant, it is fallacious to ignore/suppress evidence against diet X in making a decision. |

|

Diets A, B, and C have all failed me. This just means that diet D is all the more likely to work! |

Gambler’s fallacy. There’s no particular reason to think that failing on one diet makes another’s succeeding any more likely. |

Minds that Mattered: Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was a German-American political theorist and philosopher whose work focused on the nature of power, authority, and totalitarianism. Born into a Jewish family in Hanover, Germany, Arendt fled Nazi Germany in 1933 and eventually settled in the United States in 1941. She became a prominent intellectual figure in post-war America, holding positions at various universities and publishing influential works on political philosophy.

Arendt’s most famous work, “The Origins of Totalitarianism” (1951), is a comprehensive analysis of the rise of totalitarian regimes in the 20th century, focusing on Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union under Stalin. In this work and others, Arendt sought to understand the social and political conditions that allowed for the emergence of these oppressive systems and the ways in which they maintained power through the manipulation of public opinion and the suppression of dissent.

Key Ideas

In her book “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,” Arendt introduced the concept of the “banality of evil” to describe how ordinary people can participate in atrocities without being inherently evil themselves. She argued that Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi bureaucrat responsible for organizing the deportation of Jews to concentration camps, was not a sadistic monster but rather a disturbingly average person who unthinkingly followed orders. This idea challenges the hasty generalization that all those involved in the Holocaust were inherently evil or sadistic. Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil highlights the dangers of hasty generalization in moral reasoning. By assuming that only inherently evil people can commit atrocities, we risk overlooking the ways in which ordinary people can be complicit in oppressive systems through their unquestioning obedience to authority and lack of critical thinking. Arendt’s work encourages us to resist the temptation to make sweeping judgments about individuals based on their actions and instead to examine the broader social and political contexts that enable atrocities to occur.

“The Origins of Totalitarianism,” Arendt analyzed how totalitarian regimes used propaganda to manipulate public opinion and maintain their grip on power. She introduced the concept of the “supersense,” which refers to the totalitarian claim to possess a higher understanding of reality that justifies their actions and policies. Totalitarian propagandists often appealed to inappropriate authorities, such as pseudoscientific theories or the supposed infallibility of the leader, to support their supersense and discourage critical thinking. Arendt’s analysis of totalitarian propaganda demonstrates how appeals to inappropriate authority can be used to manipulate individuals and societies. By presenting their claims as backed by unquestionable sources of truth, totalitarian regimes sought to suppress independent thinking and maintain control over the population. Arendt’s work encourages us to be cautious of claims that rely on the perceived status or expertise of the speaker rather than the merits of the argument itself, as this fallacy can make us vulnerable to manipulation by those seeking to establish or maintain oppressive systems of power.

In “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” Arendt introduced the concept of the “lying world of consistency,” which refers to the totalitarian tendency to create a distorted sense of reality in which all events and phenomena are attributed to the actions of the regime or its enemies. This distortion often relied on the false cause fallacy, in which a causal relationship is claimed between events without sufficient evidence or logic. Arendt argued that the lying world of consistency was essential to the maintenance of totalitarian power, as it provided a simplistic and emotionally compelling narrative that could mobilize the masses and suppress dissent. Arendt’s concept of the lying world of consistency highlights the dangers of the false cause fallacy in political discourse. By presenting complex phenomena as the result of a single cause, totalitarian regimes sought to create a distorted understanding of reality that served their interests. Arendt’s work encourages us to be skeptical of simplistic explanations for complex events and to seek out more nuanced and evidence-based understandings of the world. By recognizing and resisting the false cause fallacy, we can become more resilient to the manipulations of oppressive systems of power.

Influence

Hannah Arendt’s work has had a profound impact on political philosophy, social theory, and the study of totalitarianism. Her insights into the nature of power, authority, and the mechanisms of oppressive regimes have influenced generations of thinkers and activists.

Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil has become a widely recognized and debated idea in discussions of morality, responsibility, and the psychology of those who participate in atrocities. Her analysis of the Eichmann trial has sparked ongoing conversations about the nature of culpability and the role of individual choice in the context of oppressive systems.

In the field of totalitarianism studies, Arendt’s work remains a foundational text. “The Origins of Totalitarianism” continues to be widely read and cited by scholars seeking to understand the rise and maintenance of authoritarian and totalitarian regimes. Arendt’s insights into the role of propaganda, ideology, and the manipulation of reality in these systems have informed subsequent research and analysis.

Beyond academia, Arendt’s ideas have influenced political activists and movements seeking to resist oppression and promote human rights. Her emphasis on the importance of critical thinking, individual responsibility, and the need to resist the manipulations of those in power has resonated with activists and citizens alike.

Today, as the world faces ongoing challenges related to authoritarianism, propaganda, and the erosion of democratic norms, Arendt’s work remains as relevant as ever. Her insights continue to provide a valuable framework for understanding and confronting the mechanisms of oppression and the importance of individual agency in the struggle for a more just and humane world.

Discussion Questions: Hannah Arendt

- How does Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil challenge our assumptions about the nature of those who participate in atrocities? What are the implications of this idea for our understanding of moral responsibility and culpability?

- In what ways do totalitarian regimes use propaganda and appeals to inappropriate authority to manipulate public opinion and suppress dissent? How can individuals and societies resist these manipulations?

- How does the false cause fallacy contribute to the creation and maintenance of what Arendt calls the “lying world of consistency” in totalitarian systems? What are the consequences of this distortion of reality for individuals living under these regimes?

- Arendt’s work emphasizes the importance of critical thinking and individual responsibility in resisting oppression. What role do these qualities play in promoting and defending democratic values and human rights?

- How can Arendt’s insights into the mechanisms of totalitarianism inform our understanding of contemporary political challenges, such as the rise of authoritarianism, the spread of misinformation, and the erosion of democratic norms?

Glossary

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Appeal to Anecdotal Evidence |

This fallacy occurs when specific instances, personal stories, or isolated examples are used to make a general conclusion, without considering a wider range of scientific evidence or statistical data. |

|

Appeal to Biased Authority |

A fallacy where an argument relies on an authority who may have professional credentials but is known to have biases or vested interests that could prejudice their objectivity and judgment. |

|

Appeal to Unqualified Authority |

This fallacy occurs when advice or assertions are sought from a person who has no expertise, training, or specific knowledge in the area under consideration. |

|

Banality of evil |

Arendt’s concept that describes how ordinary people can participate in atrocities, often by unthinkingly following orders and failing to critically examine their actions. |

|

Bias |

A systematic error in the design, conduct, or analysis of a study that can lead to inaccurate conclusions. |

|

Blinding |

The practice of keeping participants and/or researchers unaware of which group a participant belongs to, to reduce bias. |

|

Confounding Variable |

A factor that influences both the dependent and independent variables, potentially causing a false association between them. |

|

Control Group |

The group of participants in an RCT that does not receive the intervention or treatment, serving as a baseline for comparison. |

|

Converse Accident |

Also known as ‘hasty induction’, this is the fallacy of drawing a broad, generalized conclusion from specific, exceptional instances, thereby neglecting the possibility of counterexamples. |

|

Gambler’s Fallacy |

The erroneous belief that if something happens more frequently than normal during a given period, it will happen less frequently in the future, or vice versa. This fallacy ignores the independence of events. |

|

Hasty Generalization |

A logical fallacy where a general conclusion is drawn from a sample that is either too small or biased. This premature generalization leads to conclusions that are not supported by the requisite evidence. |

|

Lying World of Consistency |

Arendt’s term for the totalitarian tendency to create a distorted sense of reality in which all events and phenomena are attributed to the actions of the regime or its enemies, often relying on the false cause fallacy. |

|

Phase 1 Trial |

A stage of a clinical trial typically involving a small group of healthy volunteers, that primarily assesses the safety and side effects of a treatment. |

|

Phase 2 Trial |

A stage of a clinical trial involving a larger group of participants who have the condition being treated, that assesses the efficacy and optimal dosage of a treatment. |

|

Phase 3 Trial |

A stage of a clinical trial involving a large group of participants, that compares the effectiveness of the new treatment to existing standard treatments. |

|

Phase 4 Trial |

Post-approval studies that monitor the long-term safety and effectiveness of a treatment after it has been approved and is being used in the general population. |

|

Placebo |

An inactive substance or treatment that appears identical to the treatment being tested, used in the control group to account for the psychological effects of receiving a treatment. |

|

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc |

A fallacy where it is concluded that because one event followed another, the first must be the cause of the second. This ignores other potential causal factors or the possibility of coincidence. |

|

Propaganda |

The systematic dissemination of information, often misleading or biased, to promote a particular political cause or point of view. |

|

Randomized Control Trial (RCT) |

A type of scientific experiment that randomly assigns participants into different groups to test the effectiveness of a treatment or intervention while minimizing bias and confounding variables. |

|

Slippery Slope |

This fallacy suggests that a relatively minor first step will lead to a chain of related and progressively more significant events, leading to some ultimate, often drastic, outcome. |

|

Supersense |

The totalitarian claim to possess a higher understanding of reality that justifies their actions and policies, often supported by appeals to inappropriate authorities. |

|

Suppressed Evidence |

This fallacy involves intentionally ignoring or omitting relevant data or information that contradicts or undermines one’s argument or position, thereby presenting a skewed and biased perspective. |

|

Totalitarianism |

A form of government characterized by the complete control of all aspects of society by a single party or leader, often relying on propaganda, terror, and the suppression of individual freedoms to maintain power. |

|

Treatment Group |

The group of participants in an RCT that receives the intervention or treatment being tested. |

|

Unrepresentative Sample |

A logical fallacy where conclusions are drawn from a sample that does not accurately represent the population as a whole. The sample may be large but still fails to encapsulate the diversity or variations present in the target group. |

References

Arendt, Hannah. 2017. “The Origins of Totalitarianism.” Penguin Classics.

Arendt, Hannah. 2006. “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.” Penguin Classics.

Bergstrom, Carl T., and Jevin D. West. 2021. “Calling Bullshit: The Art of Skepticism in a Data-Driven World.” Random House.

Chabris, Christopher, and Daniel Simons. 2011. “The Invisible Gorilla: And Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us.” Crown.

Eldridge, Richard. 2019. “Hannah Arendt.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/arendt/.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. “Thinking, Fast and Slow.” Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Levinovitz, Alan. 2020. “Natural: How Faith in Nature’s Goodness Leads to Harmful Fads, Unjust Laws, and Flawed Science.” Beacon Press.

McRaney, David. 2011. “You Are Not So Smart: Why You Have Too Many Friends on Facebook, Why Your Memory Is Mostly Fiction, and 46 Other Ways You’re Deluding Yourself.” Gotham Books.