3 Cartoonishly Bad Reasoning: An Introduction to Informal Fallacies

A Little More Logical | Brendan Shea, PhD

Welcome to the wacky world of fallacies, where SpongeBob and Patrick’s comical campaign for mayor of Bikini Bottom serves as our guide to spotting flawed reasoning. In this chapter, we’ll dive deep into the murky waters of circular arguments, false dichotomies, and emotional appeals, using relatable examples from beloved cartoon characters and thought-provoking parallels to real-world situations. We’ll learn from the logical missteps of Bart Simpson, gain wisdom from the Futurama gang’s humorous antics, and draw insightful connections to the works of W.E.B. Du Bois. Along the way, you’ll acquire a toolkit for identifying and avoiding common fallacies, honing your critical thinking skills to navigate the treacherous tides of everyday argumentation. So, put on your scuba gear and join us on this hilarious and enlightening expedition into the depths of fallacious reasoning, where laughter meets logic, and cartoon capers illuminate the intricacies of rational discourse.

Learning Outcomes: By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify and differentiate between formal and informal fallacies, recognizing their key characteristics and how they undermine logical reasoning.

- Spot and avoid common informal fallacies such as circular arguments (begging the question), false dichotomies, ad hominem attacks, appeals to ignorance, and emotional appeals in everyday discourse.

- Analyze arguments in popular media, literature, and real-life situations to detect fallacious reasoning, using examples from SpongeBob SquarePants, The Simpsons, Futurama, and other sources.

- Apply the principle of charity when evaluating arguments, striving to interpret others’ reasoning in the most rational and coherent manner possible before critiquing it.

- Reflect on the role of emotions in logical reasoning, drawing insights from Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean to cultivate a balanced and well-integrated approach to argumentation.

Keywords: Fallacy, Formal fallacy, Informal fallacy, Circular argument, Begging the question, False dichotomy, Ad hominem, Abusive ad hominem, Circumstantial ad hominem, Tu quoque, Poisoning the well, Appeal to ignorance, Pseudoscience, Conspiracy theory, Appeal to people, Appeal to pity, Appeal to force, Principle of charity, Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean, Double consciousness, Fallacy of composition, Affirming the consequent, Denying the antecedent, Illicit conversion

Intro: Election Season in Bikini Bottom

Background: The residents of Bikini Bottom had grown increasingly frustrated with the lack of leadership and guidance from their current mayor. They had had enough and determined it was time to elect a new one. So, they decided to hold a mayoral election. SpongeBob and Patrick, the two best friends and residents of Bikini Bottom, decided to run against each other for the position. Before the election, however, a series of strange and outrageous events began to unfold.1

First, Mr. Krabbs, the owner of the Krusty Krabb restaurant, was seen floating around town in a giant octopus-shaped hot air balloon in an attempt to promote his candidacy. When the balloon collapsed and threatened to strangle everyone, it was only through the efforts of Sandy, the local scientist, that the town was saved. These events only further convinced the citizens of Bikini Bottom that Sandy was the clear best candidate for mayor. However, SpongeBob and Patrick were still determined to win the election and argued amongst themselves about who should be the next mayor. Without SpongeBob and Patrick’s votes, though, Mr Krabbs will win election against Sandy. Squidward, their neighbor, was fed up with the arguing and tried to mediate a resolution, but to no avail.

Patrick: I should be mayor of Bikini Bottom because I’m the best star(fish) for the job.

SpongeBob: No, I should be mayor because I’m the most qualified.

Squidward: That’s circular reasoning! You’re both just asserting that you should be mayor without proof.

Patrick: Well then, you’ll have to decide between us. If I’m not the mayor, then the only choice is SpongeBob.

SpongeBob: Yeah, if it’s not me then it has to be Patrick! At least one of us is going to be the mayor. Yeah!

Squidward: That’s a false dilemma. I think can think of million other fish who would be better suited for the job, Sandy, Plankton, Gary, Mr. Krabs, and even me! It’s not like I am forced to choose just between the two of you.

Patrick: No way! Consider this argument: If I am the mayor, then SpongeBob is not the mayor. And clearly, SpongeBob is not the mayor. So I should be the mayor!

Squidward: That’s denying the antecedent! If SpongeBob is not the mayor, it does not necessarily follow that Patrick should be mayor. Haven’t you two taken a logic class?

Patrick: Alright, then, how about this? If I am the mayor of Bikini Bottom, then I must live in Bikini Bottom. And clearly, I live in Bikini Bottom. So I should be mayor!

SpongeBob: Exactly! And if I’m the mayor, then everyone will be happy. And everyone is happy. So it must be me!

Squidward: You are both committing the fallacy of affirming the consequent! Just because something good happened doesn’t mean that either of you caused it. Plus, you’re equivocating when you say “everyone”. Who exactly are you referring to? Do you mean the citizens of Bikini Bottom? Or all the fish in the ocean? And do you really mean everyone, or a majority, or just you and Patrick? I certainly wouldn’t be happy if either of you were the mayor.

Patrick: I’m the best choice for mayor because the choice of mayor is made by the citizens of Bikini Bottom. And since I am a citizen of Bikini Bottom, I get to decide who is mayor. I choose myself!

SpongeBob: However, if I’m the mayor, then Bikini Bottom will finally get to eat all of the Krabby patties it’s so desperately been craving. I know that all of the people here love Krabby patties. From this, it naturally follows that the city as a whole loves Krabby patties, too. If I’m mayor, I’ll feed the city, and not just the fish that live here.

Squidward: You’re both committing the fallacy of division and composition! Just because a whole has a certain property doesn’t mean that each part has that same property. Also, just because each part has a certain property doesn’t mean that the whole must have that same property. Cities don’t Krabby patties! Single starfish don’t get to decide the outcome of elections. That’s not how logic works!

SpongeBob: Patrick, how can someone as dim-witted as you hope to be mayor of Bikini Bottom, Patrick? You’ll obviously just need me to do all of the thinking anyway!

Patrick: Well, SpongeBob, *I* was just wondering how someone as immature and emotional as you are could hope to be mayor. I’m the stable adult around here.

Squidward: That’s a complex question fallacy! You both are asking complex questions that assume something is true and then use that assumption to make an (unfair) argument. This isn’t how logic works.

Patrick: You know, SpongeBob, after taking about it, I’m not sure I want to be mayor any more. I’ve heard Sandy has amazing karate skills. I’m going to vote for her!

SpongeBob: That’s a great idea. I heard she can make jellyfish fly. She’s a great candidate.

Squidward (sighing): Sandy does have a degree in marine biology, experience running a business and knowledge of local politics. You should definitely vote for her.

- Choose 1 or 2 of SpongeBob’s and Patrick’s arguments, and put them in standard form.

- Now, explain in as much detail as you can “what went wrong” with these arguments.

- Can you think of any real life examples of the sorts of poor reasoning used in this dialogue?

What are Fallacies?

A fallacy is a mistake in reasoning or arguing. More formally, a fallacy is an argument that has something wrong with it besides being based on incorrect information. When someone uses a fallacy, their argument doesn’t hold up well under scrutiny, and they ought to have known better. It’s important to know that fallacies can be (deductive) valid or (deductive) invalid, and (inductive) strong or (inductive) weak, but they can never be (deductive) sound or (inductive) cogent.

Let’s break that down:

Deductively Invalid (Always Fallacious). If an argument is invalid, this means that even if the premises (the starting points of the argument) are true, the conclusion doesn’t logically follow. For example, suppose Bugs Bunny says: “If something is a carrot, then it’s delicious. This is a delicious snack. Therefore, this snack is a carrot.” This is an invalid argument, and is called a formal fallacy (more on that later). Even if the premises were true, the conclusion does not logically follow. The fact that the snack is delicious doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a carrot. It could be any delicious food.

Deductively Valid (or Inductively Strong) but Fallacious. An argument can be valid, meaning it is structured correctly and the conclusion logically follows from the premises, but still fallacious if the premises are untrue or questionable. For example, suppose Squidward asserts: “All creatures who live in a pineapple under the sea are excellent clarinet players. SpongeBob lives in a pineapple under the sea. Therefore, SpongeBob is an excellent clarinet player.” This argument is valid in structure – if the premises were true, the conclusion would logically follow. However, the premises are questionable (especially the first one). This makes the argument fallacious despite its valid structure. For similar reasons, we can have arguments that are inductively strong but fallacious. Arguments such as begging the question or false dichotomy are of this sort.

Inductively Weak (Always Fallacious). An inductively weak argument doesn’t provide enough support for its conclusion, making it less convincing. For example, suppose Mr. Burns reasons from “There haven’t been any accidents at my nuclear powerplant in the last week” to “There probably won’t be any accidents in the next 10 years, even if I radically lower safety standards.” The premises here simply don’t support the conclusion.

Fallacies are never deductively sound or inductively cogent. Remember, a sound argument is one that is not only valid but also has all true premises. A cogent argument is inductively strong and has all true or mostly true premises. Fallacies fail these criteria because they involve some form of incorrect reasoning or false premises. A cogent argument might still have a false conclusion, of course, but that doesn’t mean it’s fallacy as it represents the “best reasoning we could have done.”

Fallacies aren’t just in speech or writing; we can fall into the trap of fallacious thinking too. It’s easy to dismiss someone’s argument because we don’t like them, but that’s a fallacy in itself. The principle of charity requires us to represent others’ arguments fairly, and try to find ways to represent their arguments that don’t presume the person is committing a fallacy. Finally, ne aware of how easy it is to spot others’ fallacies while missing our own. This is a common human tendency, as psychological research shows. So, when you think someone else is making a fallacious argument, check your own reasoning too!

Formal Fallacies

Formal fallacies are errors in the logical structure of a (deductive) argument. They are invalid because their form—a specific arrangement of premises and conclusion—leads to a conclusion that does not logically follow from the premises. Any argument with these forms is invalid, regardless of the content. For example:

Affirming the Consequent. If P, then Q. Q is true. Therefore, P must be true.

- Example: “If I use an ACME rocket (P), I’ll catch the Road Runner (Q). I caught the Road Runner (Q). Therefore, I must have used an ACME rocket (P).”

This form is invalid because even if Q is true, it doesn’t necessarily mean P is true. There could be other reasons for Q happening.

Denying the Antecedent. If P, then Q. P is not true. Therefore, Q is not true.

- Example: “If Sonic is fast (P), he will escape my trap (Q). Sonic is not fast (P is not true). Therefore, he won’t escape my trap (Q is not true).”

This form is invalid because the falsity of P does not necessarily imply the falsity of Q. There could be other factors that lead to Q.

Illicit Conversion: All A are B. Therefore, all B are A.

Example: “All Smurfs are small. Therefore, all small things are Smurfs.”

This is a fallacy because the fact that all Smurfs are small does not mean that everything small is a Smurf. The conversion of the subject and predicate is illicit here, leading to an invalid conclusion.

Unlike their formal counterparts, informal fallacies aren’t about the structural flaws in an argument; rather, they arise from problems in the argument’s content or the way it’s presented. These fallacies can be deductive or inductive and can appear strong, weak, valid, or invalid. However, they can never be sound or cogent due to issues with their premises. In the forthcoming lessons, we will explore various types of informal fallacies, beginning with one of the most common: the Circular Argument, also known as Begging the Question.

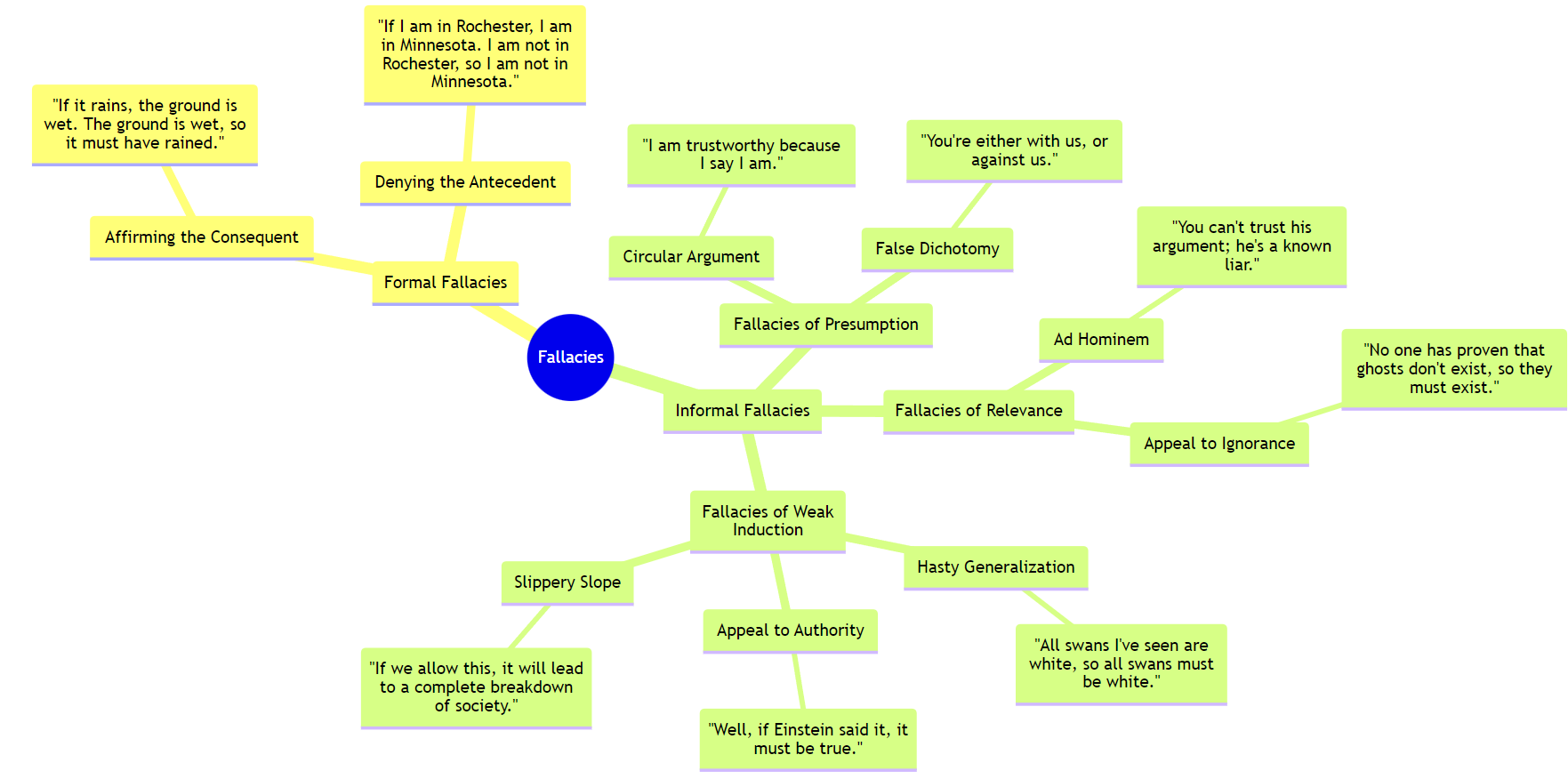

Graphic: A Family Tree of Fallacies

Bart Begs the Question

(Note: Bart and Lisa are siblings from the show The Simpsons).

Begging the Question is a subtle yet significant fallacy. It occurs when an argument’s premises assume the truth of the conclusion instead of supporting it. Essentially, the argument goes in a circle, using what it’s trying to prove as part of the proof. To get a sense of how this works, let’s consider an argument between Bart and Lisa Simpson:

Bart: “Hey, Lisa! I should get the last cupcake because, duh, I’m the Bartman. I deserve it.”

Lisa: “Oh, really, Bart? And what grand achievement has ‘the Bartman’ accomplished to earn this illustrious cupcake?”

Bart: “Well, it’s like when Milhouse wants my Krusty comics – I want them more, so they’re mine. I want this cupcake more, so obviously, it should be mine.”

Lisa: “Bart, just because you’re pulling a Milhouse and want something more doesn’t mean you automatically deserve it. You’re just going around in circles.”

Bart: “Okay, Ms. Full-of-Brains, how about this? It’s totally the right thing to do. Giving me the cupcake is like letting Homer have the last pork chop. It just makes sense.”

Lisa: “But you’re not explaining ‘why,’ Bart. That’s circular reasoning. You’re saying it’s right just because you think it’s right, without giving any real reason.”

Bart: “Fine, let’s put it this way: the person who would enjoy it most should get it, right? And that’s obviously me.”

Lisa: “You’re missing the point, Bart. That’s exactly what we’re arguing about. By claiming you should get it because you’d enjoy it the most, you’re assuming the conclusion we’re trying to reach. It’s a textbook example of begging the question.”

Bart: “Alright, then. How about this? I’m the eldest, and as Grandpa Simpson always says, ‘Age before beauty.’ That means I get the cupcake.”

Lisa: “Oh, Bart, that’s hardly a sound argument. You’re just assuming a rule—’the eldest gets their way’—and using it as the basis for your argument. It’s still circular reasoning. You need a real reason, not just an assumed rule.”

Bart: “Wait up, Lisa! You’re making my brain do the Bartman twist. Isn’t all reasoning like chasing your tail? Everything just begs the question, doesn’t it?”

Lisa: “What exactly are you getting at, Bart?”

Bart: “Look, if I try to argue why I should get the cupcake, it’s like Krusty making a joke. It all circles back to the punchline – that I should get it. It’s all just running in circles.”

Lisa: “That’s not how it works, Bart. Good reasoning isn’t a Krusty circus. You can use external facts or principles that don’t just loop back to your conclusion.”

Bart: “But those ‘external facts’ are just like Homer’s (imaginary) never-ending donut, right? You bite through it, you eventually end up where you started. Everything is circular. You end up right where you started.”

Lisa: “You’re missing a key point, Bart. It’s true that arguments are often based on deeper assumptions, but those assumptions are stepping stones, not the destination. They lead us to new conclusions, not just restate the original point in fancy Springfield lingo. Our premises shouldn’t be part of the same doughnut as the conclusion.”

Bart: “So, you mean every argument is like a ride on the Springfield Monorail? You gotta start somewhere, but it’s not the same as just ending up where you started?”

Lisa: “Exactly! You’ve surprisingly grasped it, Bart. Good reasoning is a journey. It builds on assumptions to reach new, insightful destinations, not just dance in place.”

Bart: “Whoa, deep stuff, Lisa. So, it’s like a skateboard ride, not a merry-go-round. You actually get somewhere. Still think I should get the cupcake, though.”

In the real world, of course, begging the question can be much more consequential than arguments over cupcakes, especially in areas such as politics (where people often get their news from sources that already reflect their viewpoints, and are thus unlikely to be accepted by their opponents).

False Dichotomy and the Value of the Middle Way

The False Dichotomy, also known as a False Dilemma, is a logical fallacy that occurs when an argument presents two options as the only possibilities, when in fact more options exist. It’s like being told you can either have chocolate or vanilla ice cream, ignoring the existence of other flavors. This fallacy oversimplifies complex issues by forcing a choice between two extremes, ignoring other viable alternatives.

The problem with a false dichotomy is that it limits the scope of discussion and can lead to flawed decision-making. It creates an “either/or” scenario, often for the sake of argumentative convenience or to corner the opposing side into a specific choice, ignoring the nuanced reality that often exists in a spectrum of possibilities.

Now, let’s explore this fallacy through examples from the “Teen Titans” series, where characters might find themselves trapped in overly simplified viewpoints:

Robin’s Leadership Style. “Either you follow my exact plan, or you’re not a true member of the Teen Titans.”

In a corporate setting, a manager might say, “If you don’t agree with our methods, you don’t belong in this company.” This mirrors Robin’s black-and-white approach to leadership. It (falsely) presents only two extreme options: complete agreement with the company’s methods or total incompatibility with the organization. This perspective ignores a more realistic scenario where employees might have different ideas or constructive criticisms while still being dedicated and valuable to the company. By acknowledging and fostering diverse perspectives, a workplace can innovate and improve, contrary to the rigid dichotomy presented.

Starfire’s Perception of Earth. “Earth citizens must either be exceedingly kind like my friends or utterly hostile like our enemies.”

Starfire’s view simplifies the complex nature of human behavior into two extremes. It doesn’t consider the vast middle ground where most people’s behaviors and attitudes lie, which are a mix of kindness and hostility depending on context. In the realm of politics, a similar statement might be, “You’re either a patriot who supports our policies or you’re against the nation.” Such a viewpoint oversimplifies the complex spectrum of political beliefs, where individuals might support some policies of their government and disagree with others. The false dichotomy here disregards moderate and mixed political stances, which are often where most citizens’ beliefs reside.

Raven’s Emotional Struggle. “To protect my friends, I must either completely suppress my emotions or let them run wild.”

Raven’s dilemma is akin to a common misconception in emotional management, where people believe they must either suppress all their emotions to appear strong or be completely driven by them. This belief creates a false dichotomy in emotional health, overlooking the balanced approach of recognizing, understanding, and regulating emotions. Healthy emotional management involves acknowledging emotions, understanding their source and impact, and learning to express them in a controlled and healthy manner, rather than swinging between the extremes of suppression and uncontrolled expression.

By recognizing false dichotomies in arguments, like those our Teen Titans might encounter, we can avoid falling into the trap of oversimplified reasoning. It encourages us to seek out the often-overlooked options that lie between extremes, leading to more nuanced and effective problem-solving.

Discussion Questions

- Think of a recent argument you had with a friend or family member. Can you identify any fallacies that were used during this argument? How could the argument have been improved by avoiding these fallacies?

- Choose a news article or a TV show that you recently watched. Did you notice any fallacies in the way information was presented? Discuss how these fallacies could impact the viewer’s or reader’s understanding of the issue.

- Reflect on a decision you made recently. Did you use circular reasoning to justify your choice? How can you use more sound reasoning in future decisions?

- Consider a current social or political issue. Can you identify instances where a false dichotomy is presented in the discussion of this issue? How does recognizing this fallacy change your perspective on the issue?

- Think of a topic you strongly disagree with. How would you apply the principle of charity to understand the other side’s argument better? Does this change your view of the argument?

- Reflect on a time when you found it easy to spot fallacies in someone else’s argument but not in your own. Why do you think it’s easier to identify fallacies in others’ reasoning than in our own?

- How do fallacies affect our ability to think critically? Discuss how becoming more aware of common fallacies can help you reason.

Ad Hominem—The Ultimate Insult

The Ad Hominem fallacy, a term originating from Latin meaning “to the person,” is a common logical fallacy where an argument is rebutted by attacking the character, motive, or other attribute of the person making the argument, rather than addressing the substance of the argument itself. This fallacy diverts attention from the argument’s merits and focuses on the individual’s characteristics, which are often irrelevant to the argument’s validity or truth. The key to identifying an Ad Hominem fallacy is to discern whether the personal attack is relevant to the argument. If the attack is irrelevant, it is fallacious; if relevant, it may not be.

There are several varieties of Ad Hominem attacks, each with its unique approach. The Abusive Ad Hominem involves direct verbal abuse of an individual, typically irrelevant personal attacks used to discredit their argument. The Circumstantial Ad Hominem focuses on the individual’s circumstances, suggesting that their background or interests make their argument biased or less credible. Another variety, the Tu Quoque fallacy, is a form of hypocrisy accusation – “You do it too” – where one discredits the argument by asserting the arguer’s failure to act consistently with the conclusion of the argument. Lastly, the Ad Hominem Poisoning the Well involves preemptive attacks to discredit an individual, often before they even present their argument, creating a bias against them.

It’s crucial to distinguish Ad Hominem fallacies from cogent arguments about a person’s character. In some cases, a person’s character, history, or circumstances can be relevant and crucial to the argument. For example, in a court case, questioning the credibility of a witness based on their history of lying is not an Ad Hominem fallacy; it’s directly relevant to the argument about their testimony’s reliability. Similarly, in debates about policies or actions, pointing out potential conflicts of interest due to personal circumstances can be a valid line of argumentation if those circumstances could realistically lead to bias or a compromised position. The difference lies in the relevance: if the personal attack or character scrutiny is directly related to the argument’s validity or the truth of its conclusion, it is not an Ad Hominem fallacy but a legitimate aspect of critical evaluation. Understanding this distinction is key in distinguishing fallacious personal attacks from relevant critiques of character or circumstance.

Bender’s Guide to Ad Hominem Fallacies and Legitimate Character Arguments

(Note: Bender is character from the TV Series Futurama. He is a robot who likes to insult people).

Alright, meatbags, listen up! I’m gonna teach you about Ad Hominem fallacies with my trademark charm and subtlety. And then I’ll show you how to make a legit argument about someone’s character, which I’m obviously an expert in, given my sparkling personality.

Ad Hominem Fallacies by Bender

Abusive Ad Hominem. “Hey, Fry, your idea is as dumb as your haircut. Only a guy with hair like that could think of something so stupid.”

- “This is a classic abusive Ad Hominem. I’m attacking Fry’s hair instead of his idea. It’s wrong because his hair has nothing to do with the idea’s quality, but it’s fun!”

Circumstantial Ad Hominem. “Leela, you only support saving the space whales because you’re a one-eyed alien lover. Your opinion doesn’t count.”

- “Here, I’m dismissing Leela’s view because of her circumstances. It’s wrong since her being a one-eyed alien lover doesn’t automatically invalidate her arguments about space whales.”

Tu Quoque (You Too) Fallacy. “Oh, Professor Farnsworth tells us not to mess with the space-time continuum? This from the guy who created a time machine just to steal ancient artifacts!”

- “This is the ‘you too’ fallacy. I’m accusing the Professor of being a hypocrite. It’s wrong because it doesn’t address whether his advice is good, it just points out his hypocrisy.”

Poisoning the Well. “Don’t bother listening to Dr. Zoidberg’s health advice. That guy’s a quack who couldn’t diagnose a magnet stuck to his own metal ass.”

- “This is poisoning the well. I’m discrediting Zoidberg before he even gives advice. It’s wrong because it biases you against him without considering the merit of his advice.”

Legitimate Character Arguments by Bender

Not every argument about someone’s character is bad! For example, if I were to say Fry’s ideas often lack foresight, that’s legit. Given his history of impulsive actions leading to trouble, like that time he jumped into a black hole because it looked cool. And let’s talk about me. Arguing that Bender’s plans are likely selfish isn’t Ad Hominem; it’s accurate. I mean, I once sold Fry’s spleen on the black market for beer money. Self-interest is kind of my thing. Finally, questioning the Professor’s inventions based on his past failures, like the Death Clock, isn’t Ad Hominem. It’s reasonable, considering his inventions sometimes blow up in our faces, literally.

On a more positive note, saying Leela is more likely to make responsible decisions than the rest of us is fair, given her track record of keeping Planet Express afloat despite all our shenanigans. It’s not attacking her (or us); it’s recognizing her consistent behavior. So, there you have it! Ad Hominem is attacking the person instead of the argument, and it’s usually wrong, except when it’s hilarious. But making a reasoned judgment based on someone’s character? That can be totally legit. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have some Fry’s spleen money to spend.

“You Can’t Prove Me Wrong” and the Appeal to Ignorance

The Appeal to Ignorance, or argumentum ad ignorantiam, is a logical fallacy that plays a significant role in the realms of pseudoscience and conspiracy theories. This fallacy occurs when a conclusion is drawn from the absence of evidence, rather than the presence of evidence. It operates on the principle that if something cannot be conclusively disproved, it must therefore be true, or conversely, if something cannot be proved, it must be false. This type of reasoning is problematic because it confuses the lack of evidence with evidence of absence, a critical error in logical reasoning.

Pseudoscience refers to beliefs, theories, or practices that claim to be scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience often lacks empirical support, relies on subjective interpretation, and is not open to validation or refutation through empirical testing.

A real-life example of an appeal to ignorance in pseudoscience can be found in the promotion of certain “miracle cures” or alternative medical treatments. For instance, a proponent of a new, untested herbal remedy might claim it cures a particular ailment because “there is no evidence that it doesn’t work” and

“you might as well try it.” This argument ignores the necessity for positive proof of efficacy and relies instead on the absence of disproof. In scientific practice, a claim requires empirical evidence and rigorous testing before being accepted; the burden of proof lies with the claimant, not the skeptic. Moreover, it isn’t “free” to try the miracle cure—there is almost always a cost in terms of money, unforeseen side effects (which scientific testing could have found!), or simply the lost opportunity to have your disease treated (for example, choosing herbal treatments over chemotherapy for cancer).

Conspiracy theories are explanatory hypotheses that suggest certain events or situations are the result of secret plots by usually powerful and malevolent groups. These theories often reject the standard or accepted explanation for these events, instead of proposing elaborate alternative explanations.

A notable example in conspiracy theories is the claim surrounding the moon landing being a hoax. Some conspiracy theorists assert that the moon landing was staged and filmed in a studio, citing the lack of stars in the background or the flag’s movement as “proof.” They often use the appeal to ignorance by arguing that since nobody can prove beyond a shadow of a doubt (in their view) that the landing wasn’t faked, it must have been a hoax. This again is a misuse of the principle, as it shifts the burden of proof from the conspiracy theorist, who should provide positive evidence for their claim, to those defending the moon landing.

The appeal to ignorance is problematic in both pseudoscience and conspiracy theories because it allows for the acceptance of claims without substantive evidence. It creates a situation where beliefs are justified not based on concrete evidence, but on the lack of evidence to the contrary. This reasoning is fundamentally flawed as it negates the foundational principle of empirical evidence in establishing facts.

In a world increasingly dominated by information (and misinformation), understanding the appeal to ignorance fallacy is crucial. It enables individuals to critically evaluate claims, particularly those that challenge established scientific understanding or historical facts, and fosters a more evidence-based approach to knowledge and understanding. Recognizing and countering this fallacy is essential in promoting scientific literacy and rational thought, especially in areas susceptible to misinformation, such as pseudoscience and conspiracy theories.

Ten Appeals to Ignorance to Amuse and Annoy Your Friends

- “Nobody has shown me concrete evidence that investing all my savings in a new, virtually unknown cryptocurrency isn’t a guaranteed path to wealth. I guess I’m on the verge of becoming a millionaire!”

- “Can you personally prove the Earth is round without using NASA’s photos? Maybe it’s flat, and we’ve all been misled. I’ll be here not falling off the edge.”

- “There’s no definitive proof that joining a cult that worships old toasters won’t bring enlightenment. Maybe you’re missing out on cosmic truths revealed through burnt bread.”

- “Until the government can prove that they aren’t hiding aliens in Area 51, I’ll continue to believe we’re not alone – and they’re here on vacation.”

- “Can you demonstrate conclusively that wearing green socks with purple sandals doesn’t make you more attractive? I thought not. I’m starting a trend here.”

- “You can’t prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that getting a vaccine won’t turn you into a spider-person in exactly 10 years. You just wait and see.”

- “Show me irrefutable evidence that every world leader isn’t actually a lizard person in disguise. Until then, I’ll be over here, not trusting any of them.”

- “No one has proven that drinking moonlight-infused water doesn’t cure every illness. I’ll stick to my lunar rituals—and stay away from those antibiotics—thank you.”

- “Where’s the evidence that eating only foods starting with ‘Q’ on Tuesdays doesn’t lead to a longer life? I guess I’m onto something groundbreaking.”

- “You can’t prove that my habit of driving a gas-guzzler and never recycling isn’t actually helping the environment. Maybe I’m single-handedly preventing the next Ice Age.”

Getting Emotional: Appeal to Pity and Appeal to Force

Human emotions play a crucial role in our decision-making and reasoning processes. However, when arguments rely excessively on emotional appeals rather than rational discourse, they can lead to logical fallacies. Understanding these fallacies, and Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean, can help us become well-integrated individuals whose emotions and reason work harmoniously. We’ll focus on three famous fallacies:

- Appeal to People (Argumentum Ad Populum): This fallacy occurs when an argument is considered true or better simply because many people believe it or because it is popular. It plays on our natural desire for acceptance and fear of standing out.

- Appeal to Pity (Argumentum Ad Misericordiam): This is when an argument relies on invoking pity or sympathetic feelings to persuade others, rather than presenting logical reasons. It exploits our natural compassion and empathy for others.

- Appeal to Force (Argumentum Ad Baculum): This fallacy arises when coercion, threats, or force are used in place of logical reasons. It targets our basic instincts of fear and self-preservation.

Each of these fallacies is deeply intertwined with fundamental human emotions. The appeal to people connects with our innate social instincts, the desire to belong, and the fear of isolation. The appeal to pity engages our empathy and compassionate responses. Meanwhile, the appeal to force triggers our instinctual reactions to threats and fear. Emotions are an integral part of who we are as humans, guiding our social interactions and personal decisions.

The problem arises when these emotions overpower rational thought and critical analysis. In the case of these fallacies, emotions are not just part of the decision-making process; they become the primary driver, overshadowing logical reasoning. For instance, agreeing with a popular opinion just to fit in (appeal to people), or accepting a claim because we feel sorry for someone (appeal to pity), are instances where emotion has taken the reins from reason. Similarly, changing a stance out of fear due to a threat (appeal to force) is another example of emotion-driven decision-making.

Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean provides a valuable framework here. It suggests that virtue lies in finding a balance between excess and deficiency, which can be applied to our emotional responses. The goal is not to become devoid of emotion; rather, it’s to cultivate the ability to experience emotions at the right times, to the right degree, and for the right reasons. This concept advocates for ‘training’ our emotions through reason, allowing us to become well-integrated individuals.

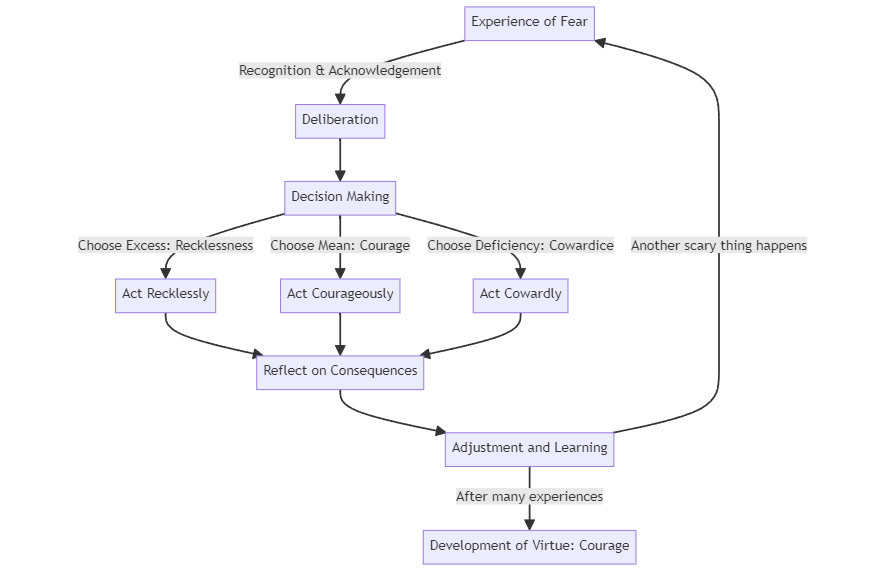

Graphic: How to Become Virtuous (Aristotle)

A well-integrated person responds to situations with an emotion that is appropriate in its intensity and duration. This balance doesn’t negate emotions but aligns them with rational thought. For example, feeling empathy in an appeal to pity is natural, but a well-integrated individual would balance this empathy with critical thinking about the logical aspects of the argument presented.

Understanding and navigating these emotional appeals involves recognizing the natural and important role emotions play in our lives, while also ensuring that our emotions work in tandem with reason. By achieving this balance, as proposed in Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean, we can make decisions that are not only emotionally sound but also logically robust, leading to a more harmonious and fulfilling life.

In order to understand how this works, we’ll consider a few “case studies” related to well-known Disney characters.

Appeal to People: Aladdin’s Dilemma

In Disney’s “Aladdin,” the titular character initially falls prey to the appeal to people fallacy. Aladdin believes that disguising himself as Prince Ali, a figure of wealth and status, will make him more acceptable and loveable, especially to Princess Jasmine. The cost of this fallacy is significant. It leads to a loss of self-identity, as Aladdin drifts away from his true self. It also creates a foundation of dishonesty in his relationship with Jasmine and places him in numerous challenging situations, including conflicts with the villainous Jafar.

Aladdin overcomes this fallacy by embracing his true identity. He realizes that genuine love and respect from others, especially Jasmine, come from being authentic. This epiphany allows him to form a real connection with Jasmine, built on trust and honesty, and to confront Jafar without the facade of Prince Ali. Aladdin’s journey demonstrates the importance of integrity over popularity.

Appeal to Pity: Elsa’s Struggle

In “Frozen,” Elsa initially succumbs to an appeal to pity. After accidentally revealing her powers, she isolates herself, believing that her isolation protects others. However, this action, fueled by fear and self-pity, leads to significant costs: Arendelle is trapped in an eternal winter, and Elsa’s relationship with her sister Anna suffers. Elsa’s self-imposed exile, while evoking pity and concern, hinders her ability to see the broader impact of her actions on her kingdom and loved ones.

Elsa overcomes this fallacy by recognizing the strength of familial bonds and the power of confronting her fears. Anna’s unwavering love and the realization that her powers can also bring joy and wonder help Elsa to balance her emotions with rational thinking. By facing her fears, Elsa not only learns to control her powers but also reestablishes her bond with Anna, showing that facing challenges head-on is more effective than retreating in self-pity.

Appeal to Force: Simba’s Redemption

In “The Lion King,” Simba faces the appeal to force fallacy. After Mufasa’s death, Scar manipulates Simba into believing he is responsible and should leave the Pride Lands. Simba’s acceptance of this false narrative, driven by fear and guilt, leads to significant costs: he abandons his responsibilities as future king and leaves his kingdom under Scar’s tyrannical rule, resulting in the Pride Lands’ downfall.

Simba’s return to Pride Rock signifies his overcoming of the appeal to force. Encounters with Timon, Pumbaa, and Rafiki, coupled with the realization of his duties, help Simba regain his courage. He confronts and overcomes his fears, challenging Scar and reclaiming his rightful place as king. Simba’s journey highlights the importance of confronting one’s fears and not allowing them to dictate life’s path.

In each story, the Disney characters initially fall victim to emotional fallacies, leading to significant personal and communal costs. However, through introspection, guidance, and personal growth, they overcome these fallacies, demonstrating the power of balancing emotion with reason. These narratives underline the importance of being well-integrated individuals, where emotions are acknowledged but do not overshadow rational thought.

Sample Problem: Finding Fallacies in the Godfather

To give you some more concrete examples of what fallacies “look” like, here are some examples from “the Godfather”:

|

Passage |

Analysis |

|

“When Don Corleone first told me that I should cast his godson in my movie, I thought this would be a terrible idea, since I’ve always thought his godson is a really bad actor. However, then he chopped off my prize horse’s head, and left the bloody head in bed with me as a warning. Now, I’ve changed my mind—the godson is obviously a great actor!” |

Appeal to Force—the person changes their mind because of a threat. Note that it is NOT a fallacy to “do what the godfather says” in order to preserve your life. The fallacy occurs only when you begin to believe whatever it is that the person threatening you wants you to believe. |

|

“I really like my godson, and I know not getting that movie part really upset him. Without a doubt, he has been mistreated by the casting agency.” |

Appeal to Pity. It’s crucially important to remember that liking someone, or feeling sorry for them, doesn’t necessarily mean their arguments are correct. In order to determine whether the conclusion is true, we would need to actually find out what happened during the audition. |

|

“Members of the mafia are everything I want to be—rich, powerful, respected, and feared. And they clearly think it is occasionally OK to murder people. So, occasionally murdering people really is OK.” |

Appeal to the People. This argument confuses two very different things—a moral conclusion about whether murdering people is OK with premises about how one wants others to see you. |

|

“My grandma always said that God helps those who helps themselves. And I clearly helped myself by importing large amounts of heroin and selling it. So, grandma (and God) would approve of my doing this.” |

Accident. This involves the misapplication of a general rule/idea (basically, that one should work hard, or something like that) to a situation that it is quite obviously not applicable to. |

|

“Tom just told me that it’s probably not the best idea for me to immediately shoot anyone who annoys me. Obviously, Tom thinks I should just passively accept whatever horrible things people do to me. But this is a recipe for disaster! So, I’m going to keep shooting people.” |

This looks like a strawman fallacy (and also a bit like a false dilemma, which we’ll be studying later). It’s almost certain that Tom isn’t really saying what the speaker says that he said, and that his real argument is a bit more nuanced. |

|

“Marlon Brando made a number of anti-Semitic comments over his life. So, I think we can dismiss any argument about his performance in the Godfather being ‘great.’” |

This is a variant of Ad hominem. It’s important to note here that one CAN make arguments about people’s character, and draw conclusions from it (e.g., “we ought not allow this person to receive big awards, or put them in future movies, etc.”). However, the argument needs to spell out the logical connection between the character flaw and the conclusion being drawn. |

|

“What do you mean you think the Godfather is too violent for your taste? After all, many of the events that happened it are based on real life, and Italian organized crime is actually still quite powerful. I think you’d find the history of the subject really fascinating…” |

Red Herring. None of the claims being offered here actually address what seems to be the actual point of contention (e.g., whether the film is too violent). |

Discussion Questions

- Reflect on a situation where you witnessed or participated in an argument. Was there an instance where the character or circumstances of a person were used to discredit their argument? Discuss whether this was a legitimate critique or an Ad Hominem fallacy. Consider Bender’s distinction between fallacious attacks and relevant character critiques.

- Have you ever been on the receiving end of an Ad Hominem attack? How did it affect the course of the argument and your emotional response?

- Identify an example from media or public discourse where the Appeal to Ignorance fallacy is used, such as in discussions of pseudoscience or conspiracy theories. Analyze why this fallacy can be persuasive to an audience and how it can be effectively countered.

- Reflect on a personal decision you made that was influenced more by emotion than by logical reasoning. Discuss how the Appeal to Pity or Appeal to Force might have played a role, and how Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean could have helped in achieving a more balanced decision.

- Discuss the role of emotions in logical fallacies, particularly in the context of the Appeal to People fallacy. How do social pressures and the desire for acceptance influence our acceptance of arguments? Consider how this plays out in social media or peer groups.

- Choose a fictional character from a book, movie, or TV show and analyze a scenario where they use or fall victim to one of the discussed fallacies. Discuss how the fallacy shapes the narrative and the character’s actions.

Minds that Mattered: WEB De Bois

W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) was an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, and writer. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois was the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard University. Throughout his life, he fought tirelessly against racial discrimination and inequality, becoming one of the most influential figures in the early civil rights movement.

Du Bois was a prolific writer and scholar, publishing numerous books, articles, and essays on race, sociology, history, and politics. His most famous work, “The Souls of Black Folk” (1903), is a collection of essays that explore the African American experience and the impact of racism on American society. Du Bois was also a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909 and served as the editor of its magazine, The Crisis, for more than two decades.

Key Ideas

In “The Souls of Black Folk,” Du Bois introduced the concept of “double consciousness,” which refers to the psychological challenge faced by African Americans of reconciling their identity as both American and Black in a society that often devalues and discriminates against them. He described this experience as a “peculiar sensation” of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” This concept highlights the internal struggle and conflict that arises from being forced to navigate two different cultural identities and expectations, often leading to a sense of alienation and disempowerment. Du Bois’s idea of double consciousness is closely related to the fallacy of false dichotomy, which presents two options as the only possible choices, ignoring the potential for additional alternatives or middle ground. The notion that one must choose between being American or Black, rather than embracing and celebrating both identities, is an example of this fallacy. Du Bois’s work challenges this false dichotomy and advocates for the recognition and valuation of the unique experiences and contributions of African Americans.

Du Bois advocated for the education and empowerment of a “Talented Tenth,” a group of exceptional African American leaders who would serve as role models and advocates for the broader Black community. He believed that by investing in the education and development of this elite group, they could help uplift and inspire the rest of the African American population, leading to greater social and economic progress. However, Du Bois’s critics argued that his focus on the Talented Tenth was misguided, since it assumed change was only possible through the actions of a small, privileged group (with political, economic and cultural power. They argued this overlooked the e potential for collaboration, negotiation, or grassroots efforts. Debates over these two approaches continue to this day.

Du Bois was a vocal critic of Booker T. Washington, another prominent African American leader of the time. Washington advocated for a more accommodationist approach to race relations, emphasizing vocational education and economic self-sufficiency over political and civil rights activism. Du Bois argued that Washington’s strategy was ultimately detrimental to the long-term progress of African Americans, as it failed to challenge the underlying structures of racism and inequality. That is, while it might be beneficial for (some) individuals to focus on their own economic well-being to the exclusion of “big” social issues around race, this wouldn’t fix the underlying issue. In the language of fallacies, De Bois thought the Washington had a committed a sort of “fallacy of composition”, when he assumed that the best of making things better for the black community (the “whole”) was to just focus on individual members of the community (the “parts”).

Influence

W.E.B. Du Bois’s ideas and activism had a profound impact on the civil rights movement and the broader struggle for racial equality in the United States. His concept of double consciousness has become a foundational theory in the study of race and identity, influencing generations of scholars and activists seeking to understand the psychological and social effects of racism.

Du Bois’s critique of Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist approach helped to shape the direction of the civil rights movement, emphasizing the importance of political and civil rights activism alongside efforts to promote economic self-sufficiency. His work as a founding member of the NAACP and editor of The Crisis also played a crucial role in mobilizing African Americans and allies in the fight against racial discrimination and segregation.

Moreover, Du Bois’s scholarship and writing have had a lasting impact on various fields, including sociology, history, and African American studies. His groundbreaking work, “The Souls of Black Folk,” remains a seminal text in the study of race and racism, and his ideas continue to inspire and inform contemporary discussions about racial justice and equity.

Today, Du Bois is celebrated as a visionary thinker and tireless advocate for racial equality, and his legacy continues to shape the ongoing struggle for civil rights and social justice in the United States and beyond.

Review Question: WEB De Bois

- How did W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of “double consciousness” challenge the fallacy of false dichotomy in understanding African American identity?

- What do you think of Du Bois idea of trying to cultivate a “Talented Tenth” of black leaders? Can you think of current social movements where this strategy might make sense?

- In your own words, how would you explain what the disagreement between De Bois and Washington was “about”? Think of a current social justice issue, and explain how each might approach it.

- What role did Du Bois play in shaping the direction and strategies of the early civil rights movement, particularly through his work with the NAACP and The Crisis?

- How have Du Bois’s ideas and scholarship influenced contemporary discussions and movements related to racial justice and equity?

Glossary

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Abusive Ad Hominem |

A fallacy where an argument is rebutted by attacking the character of the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. For example, “You can’t believe John’s claim; he’s a known liar,” focuses on John’s character instead of addressing his claim. |

|

Ad Hominem Poisoning the Well |

A preemptive attack on a person to discredit their argument or testimony before they even make it. It’s a strategy to bias the audience against the person and their argument. For example, “Don’t listen to his opinion on this matter; he’s incapable of rational thought.” |

|

Affirming the Consequent |

A logical fallacy where one incorrectly infers the truth of a premise from the truth of the consequent in a conditional statement. For example, “If it rains, the ground will be wet. The ground is wet, therefore it must have rained,” ignores other possible causes for the wet ground. |

|

Appeal to Force |

A fallacy where coercion, threats, or force are used instead of logical reasoning. It targets the audience’s fear or self-preservation instincts, like “Agree with me, or you’ll face the consequences.” |

|

Appeal to Ignorance |

A fallacy where a claim is assumed to be true because it has not been proven false, or vice versa. For example, “There’s no evidence that ghosts don’t exist, therefore they must exist,” confuses the lack of evidence for evidence of absence. |

|

Appeal to People |

A fallacy where the popularity of a premise is presented as evidence of its truth. Also known as Argumentum Ad Populum, it suggests that because many people believe something, it must be true. For example, “Everyone believes in this health remedy, so it must work.” |

|

Appeal to Pity |

A fallacy where an argument relies on invoking pity or sympathetic feelings rather than presenting logical reasons. It exploits the audience’s compassion to support a conclusion, like “You must pass me in this course; I’ve had a difficult year.” |

|

Circular Argument (Begging the Question) |

A fallacy where the conclusion of an argument is assumed in the formulation of the argument. It’s circular because the argument takes for granted what it’s supposed to prove. For example, “I am trustworthy because I always tell the truth,” uses the conclusion (trustworthiness) as a premise. |

|

Circumstantial Ad Hominem |

A fallacy where an argument is dismissed based on the circumstances or background of the person making it, suggesting bias or an ulterior motive. For example, “Of course, the senator supports this policy; she will benefit from it financially,” implies that her support is solely due to personal gain, not the policy’s merits. |

|

Denying the Antecedent |

A logical fallacy in which the falsity of a premise is inferred from the falsity of its antecedent in a conditional statement. For example, “If it is a dog, it has four legs. It is not a dog, therefore it does not have four legs,” which erroneously excludes other four-legged animals. |

|

Doctrine of the Mean |

Aristotle’s ethical doctrine suggesting virtue lies in finding a balance between excess and deficiency. It advocates for moderation in all things and proposes that virtuous behavior involves finding the mean between two extremes, allowing for a harmonious and balanced life. This concept applies to emotions, actions, and moral decisions. |

|

Double Consciousness |

The psychological challenge faced by African Americans of reconciling their identity as both American and Black in a society that often devalues and discriminates against them |

|

Fallacy |

A mistaken belief or error in reasoning, often resulting in an invalid argument or misleading conclusion. It’s a flaw in the structure of an argument that renders its conclusion invalid or suspect. |

|

Fallacy of Composition |

The mistaken inference that because something is true of individual parts, it must be true of the whole as well. |

|

False Dichotomy |

A fallacy that presents two opposing options as the only possibilities, when in fact more options exist. For example, “You’re either with us or against us,” ignores other neutral or alternative positions. |

|

Formal Fallacy |

A logical error in the form or structure of an argument. It arises from a defect in the logical form of the argument, making it invalid regardless of the content of the premises. |

|

Illicit Conversion |

A fallacy occurring in a categorical syllogism when the subject and predicate of a premise are improperly switched in the conclusion. For example, “All dogs are mammals. Therefore, all mammals are dogs,” which is a false conversion of the original premise. |

|

Informal Fallacy |

A flaw in reasoning that occurs due to the content or context of the argument, rather than its form. These fallacies are often based on assumptions, irrelevant information, or misunderstandings of the argument’s subject matter. |

|

Pseudoscience |

Practices, beliefs, or methodologies that claim or appear to be scientific and factual but lack empirical support, are inconsistent with the scientific method, or cannot be reliably tested. Pseudoscience often relies on anecdotal evidence and fails to adhere to rigorous standards of scientific evaluation. |

|

Tu Quoque |

A fallacy where a person’s argument is dismissed or criticized based on their failure to act consistently with its content. It’s a form of hypocrisy accusation, like saying, “You can’t argue against smoking since you used to smoke.” |

References

Curtis, Gary N. 2024. “Logical Fallacies: The Fallacy Files.” 2024. https://www.fallacyfiles.org/.

Dowden, Bradley. 2020. “Fallacies.” In Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/fallacy/.

Hansen, Hans. 2023. “Fallacies.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Spring 2023. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/fallacies/.