6 Arguing About Right and Wrong: Ethics at the Movies

A Little More Logical | Brendan Shea, PhD

Embark on a captivating journey through the realm of moral philosophy, as we explore the fundamental questions of right and wrong, good and evil, and how we ought to live. This chapter delves into the major normative ethical theories – utilitarianism, deontology, virtue ethics, and social contract theory – drawing upon thought-provoking examples from popular films to illuminate these abstract concepts. From E.T.’s dilemmas of loyalty and rule-breaking to Batman’s adherence to his no-killing principle, from Groundhog Day’s portrayal of personal transformation to A Hidden Life’s depiction of moral courage, the world of cinema offers a rich tapestry of ethical quandaries and character arcs that bring philosophy to life. Through the lens of thinkers like Aristotle, Kant, Mill, and Rawls, we’ll examine the strengths and limitations of each approach, grappling with issues of character, duty, consequences, and justice. Whether you’re a budding philosopher, a movie buff, or simply someone seeking to live an examined life, this chapter will equip you with the tools to navigate the complex landscape of morality, both on the silver screen and in the real world.

Learning Outcomes: By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand and differentiate between the major normative ethical theories, including utilitarianism, deontology, virtue ethics, and social contract theory.

- Apply these ethical frameworks to analyze moral dilemmas and character development in popular films.

- Evaluate the strengths and limitations of each approach, considering factors such as moral intuitions, practical guidance, and social/institutional context.

- Reflect on how different ethical traditions, such as Aristotelian, Confucian, and care ethics, conceptualize virtues and the good life.

- Engage with key thinkers and ideas in moral and political philosophy, including Aristotle’s eudaimonia, Kant’s Categorical Imperative, Mill’s utilitarianism, Rawls’ veil of ignorance, and the principles of justice.

- Apply ethical reasoning and principles to real-world issues and your own life choices, recognizing the complex interplay of character, duties, consequences, and social contexts in moral decision-making.

Keywords: Ethics, Normative ethics, Descriptive ethics, Metaethics, Utilitarianism, Consequentialism, Ethical egoism, Psychological egoism, Ayn Rand, Friedrich Nietzsche, Deontology, Categorical Imperative, Immanuel Kant, Rights, Robert Nozick, Virtue ethics, Eudaimonia, Aristotle, Confucianism, Natural law, Thomas Aquinas, Care ethics, Political philosophy, John Rawls, Social contract theory, Veil of ignorance, Liberty principle, Difference principle, Fair equality of opportunity

What is Ethics?

Ethics is the branch of philosophy that studies questions of right and wrong, good and bad. It investigates how we ought to live and treat others. Should we always tell the truth, or is lying sometimes justified? Is killing always wrong, or can it be permissible in certain circumstances like self-defense? What are our obligations to help others in need? These are some of the fundamental questions that ethics grapples with.

Within the field of ethics, there are several main areas of study:

- Normative ethics focuses on figuring out moral standards and principles that govern right and wrong conduct. It seeks to establish guidelines for how people should behave.

- Descriptive ethics investigates what people’s moral beliefs and practices actually are, not what they should be. It looks at things like what different cultures consider right and wrong.

- Metaethics explores the nature of moral claims themselves. It asks questions like: Where do moral principles come from? Are moral claims objective facts or just subjective opinions? How can moral claims be justified?

In this chapter, we’ll be focusing primarily on normative ethical theories – attempts by philosophers to systematically answer the question of what makes actions right or wrong and to provide principled guidance for moral behavior. We’ll look at four major approaches that have been influential historically and remain important today: egoism, utilitarianism, deontology, and virtue ethics. Along the way, we’ll illustrate the key ideas with examples from popular movies to help make these abstract theories more concrete and relatable.

For a straightforward illustration of basic ethical dilemmas, we can look to the 1982 sci-fi classic E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. The plot revolves around a gentle alien botanist stranded on earth and the human children, especially a boy named Elliott, who befriend him and attempt to help him return home. The kids have to wrestle with a number of (normative) ethical quandaries:

- Is it right to defy authority figures like their mother and government agents in order to aid E.T.?

- Since E.T. is an intelligent being, does that give him intrinsic rights that must be respected regardless of the law?

- Is it permissible to steal and lie in order to protect their alien friend from harm and get him back to his planet?

Different ethical frameworks would answer these questions in different ways, as we’ll see. But the movie does a great job of dramatizing the moral tension between obeying rules, caring for others, and acting for the greater good.

Psychological Egoism

Psychological egoism is a descriptive theory about what actually motivates human behavior. It holds that all our actions are ultimately self-interested, even when they appear altruistic on the surface. The 17th century philosopher Thomas Hobbes, in his book Leviathan, argues for this view, claiming that humans are fundamentally motivated by the desire for power, glory, and self-preservation. Even seemingly selfless acts, like giving to charity or helping others, are really just ways to feel good about ourselves or to ensure that others will help us in the future.

To see how this might work in practice, let’s consider an example. Suppose that you are in a park one day and you see a small girl crying. She has lost her mother and is terrified. You (emotionally) respond by feeling some of the pain, and immediately respond. You decide to help the child, soothe her, and after an hour’s search find her mother. You are awash in good feelings as you experience mother’s tearful gratitude, the child’s admiration and affection. According to the psychological egoists, the only reason you helped was because of the good things that you expected to happen to you. The welfare of the child or moather had nothing to do with it.

For an example of psychological egoism in film, consider Han Solo’s character arc in the original Star Wars trilogy. In the first film, A New Hope, Han is a selfish mercenary who agrees to help Luke Skywalker and Obi-Wan Kenobi only after being offered a huge reward. He seems to care only about himself and his own profits. However, by the end of the film, Han returns to help Luke destroy the Death Star. Did he have a genuine moral transformation? A psychological egoist would argue that Han helped simply because he realized it was in his own long-term self-interest – he saw that the Rebel Alliance would likely win and wanted to be on the winning side. Even his seemingly noble actions were ultimately selfishly motivated.

While psychological egoism may seem to fit with some cases of apparently altruistic behavior, like Han Solo’s return in A New Hope, there are strong reasons to doubt it as a complete theory of human motivation. First, it seems to fly in the face of common experience. Most of us have felt the pull to help others even when there was nothing in it for ourselves. Think of a case where you have donated to charity anonymously or helped a stranger you’ll never see again. It’s hard to see how such acts could be self-interested.

Second, psychological egoism seems to rest on an overly simplistic view of human motivation. It assumes that self-interest and altruism are always distinct and that our ultimate motivation must be one or the other. But perhaps we have ultimately altruistic aims that nonetheless make us feel good as a side effect. The satisfaction we feel when helping others needn’t always be our main goal.

So while psychological egoism highlights the hidden self-interest behind some seemingly altruistic acts, it goes too far in claiming that all behavior is exclusively self-interested. We seem capable of genuinely other-regarding concerns and motivations, even if we’re also often motivated by self-interest.

Ethical Egoism

Ethical egoism, in contrast to psychological egoism, is a normative view about how we ought to behave. It says that moral actions are those that maximize one’s own self-interest and well-being. The 20th century philosopher Ayn Rand is a famous proponent of this view. In her novels like The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, Rand portrays the ideal human as a rational egoist who pursues his own happiness and self-interest without guilt or altruistic sacrifice. For Rand, selfishness is a virtue and altruism is a vice. We should always act to benefit ourselves, not self-sacrificially serve others.

For an illustration of ethical egoism in film, we can look to Gordon Gekko’s famous “Greed is good” speech in the 1987 movie Wall Street. Gekko declares: “The point is, ladies and gentlemen, that greed – for lack of a better word – is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms – greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge – has marked the upward surge of mankind.” This is a clear endorsement of ethical egoism – the idea that acting on self-interest and greed is not only natural but morally right and leads to overall human flourishing. Of course, by the end of the film, Gekko’s egoistic actions are shown to lead to corruption and downfall. The movie seems to reject Gekko’s full-throated ethical egoism.

Problems with Ethical Egoism

Ethical egoism also faces some serious objections. Most obviously, it seems to go against core moral intuitions that we have duties to help others and not harm them. If ethical egoism is true, then the only moral obligation we have is to ourselves. We would have no moral reason not to lie, cheat, steal or even murder so long as doing so was in our own interest. But this seems to fly in the face of common sense morality.

Consider Darth Vader’s actions in The Empire Strikes Back. Vader is willing to torture Han, Leia and even his own son Luke in order to further his own power and ambition. An ethical egoist would say Vader is acting rightly so long as such cruelty benefits him personally. But surely Vader’s actions are deeply immoral, even evil, regardless of whether they are in his self-interest. We seem to have basic obligations not to cause such suffering in others that holds regardless of the consequences for ourselves.

Ethical egoism also faces the problem of disagreement between people’s interests. What if my acting in my own interest harms your ability to act in your interest? The egoist lacks a way to resolve such conflicts because they recognize no impartial moral standpoint, only each individual’s self-interest. But we generally think there are moral reasons to adjudicate fairly between people’s competing interests.

So while ethical egoism is right to emphasize each person’s legitimate self-interest, most philosophers think it fails as a complete ethical theory. We seem to have at least some moral obligations to others that can require real sacrifice.

A Place for Egoism

While few philosophers defend “pure” versions of psychological or ethical egoism, some thinkers argue that common sense morality goes too far in the direction of altruism and self-sacrifice. 19th century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and contemporary philosopher Susan Wolf both argue, in different ways, against what they see as the damaging ideal of “moral sainthood” – the idea that we should always sacrifice ourselves for others and that our own interests are morally unimportant.

For Nietzsche, the demand for total altruism and self-denial is life-denying and unhealthy. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he describes the “last men” who have no aspirations of their own and whose only values are comfort and conformity. Against this, Nietzsche advocates for great individuals to pursue their own creative self-expression and “become what they are,” even if this means going against conventional morality.

Susan Wolf, in her article “Moral Saints,” argues that a life of pure self-sacrifice and moral duty would be unappealing and lack many important human goods. Wolf imagines a moral saint who will have a life constrained by restrictions that deprive him of a great deal that is challenging and fulfilling. While Wolf doesn’t advocate for outright egoism, she thinks common morality must make more room for personal self-interest, projects, and relationships.

To illustrate this point, consider Shrek, the grumpy ogre from the animated films. In the first movie, Shrek is a loner who just wants to live in his swamp undisturbed. He’s cynical about friendship and heroics. But over the course of the film, he learns to open up and care about others, especially his companion Donkey and love interest Fiona. Shrek becomes less selfish – a better person morally. But importantly, this change doesn’t involve totally sacrificing his own needs and personality. Indeed, Fiona comes to love Shrek for his quirky, occasionally abrasive true self. In the end, Shrek finds a balance between altruism and egoism – caring for others while still being true to himself. He doesn’t become a moral saint, and that’s part of what makes him an appealing, relatable character.

So while pure egoism seems mistaken, Nietzsche, Wolf, and Shrek suggest that a healthy dose of self-concern remains important and admirable, even from a moral point of view. There is a place for egoism as part of a broader ethical outlook.

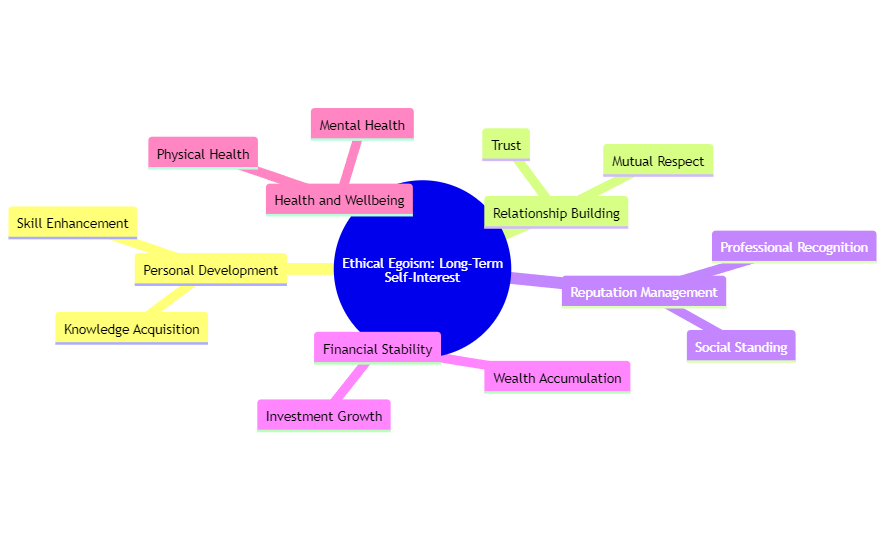

Graphic: Egoism

Glossary: Intro and Egoism

|

Term |

Definition |

|

“Last Man” (Nietzsche) |

A concept from Nietzsche’s philosophy describing individuals who lack aspirations and are driven only by comfort and conformity, in contrast to those who pursue their own unique goals and self-expression. |

|

Ayn Rand |

A 20th-century philosopher and novelist who championed ethical egoism, portraying the ideal human as a rational egoist who pursues personal happiness and self-interest without guilt or altruistic sacrifice. |

|

Descriptive Ethics |

Investigates actual moral beliefs and practices, examining what different cultures consider right and wrong, rather than prescribing norms. |

|

Ethical Egoism |

A normative view that moral actions are those that maximize one’s own self-interest and well-being, famously endorsed by Ayn Rand, who viewed selfishness as a virtue. |

|

Frederich Nietzsche |

A 19th-century philosopher who criticized traditional moral ideals like altruism, advocating instead for the development of individual greatness and self-expression, often at odds with conventional morality. |

|

Metaethics |

Examines the nature of moral claims themselves, including questions about the origin of moral principles, whether they are objective or subjective, and how they can be justified. |

|

Moral Saint |

A concept discussed in critiques of traditional morality, representing an individual whose life is dominated by moral considerations, often to the detriment of personal interests and fulfillment. |

|

Normative Ethics |

Focuses on determining moral standards and principles governing right and wrong conduct, aiming to establish guidelines for behavior. |

|

Psychological Egoism |

A descriptive theory suggesting all human actions are fundamentally motivated by self-interest, even when they appear altruistic. |

|

Thomas Hobbes |

A 17th-century philosopher who advocated for psychological egoism, asserting that all human actions are driven by self-interest for power, glory, and self-preservation. |

Questions: Egoism

- Can you think of real-life examples where people acted in seemingly altruistic ways but may have had egoistic motivations? How does this impact your moral assessment of their actions?

- Imagine a society where everyone consistently acted according to ethical egoism. What would be the benefits and drawbacks of such a society?

- Do you think the portrayal of egoistic characters like Gordon Gekko in Wall Street or Darth Vader in Star Wars makes egoism seem more or less appealing as an ethical framework? Why?

- Is there a risk that common moral ideas about self-sacrifice and altruism can be taken too far or become unhealthy, as thinkers like Nietzsche and Wolf suggest? Where should we draw the line?

What is Utilitarianism?

Utilitarianism is a normative ethical theory that holds that the morally right action is the one that produces the greatest good for the greatest number of people. In other words, utilitarianism states that we should always act to maximize overall happiness or well-being (or “utility”) for everyone affected by our actions.

The classic utilitarian slogan, coined by Jeremy Bentham, is “the greatest good for the greatest number.” Utilitarians define “good” in terms of well-being, pleasure, or happiness and “bad” in terms of suffering or unhappiness.

Act Utilitarianism

Act utilitarianism is the most straightforward form of the theory. It says that the right act is the one that produces the greatest overall utility in that particular situation. So for any individual moral decision, we should choose the option that will result in the most total happiness (or least total unhappiness) for all affected.

To illustrate, consider a famous thought experiment: A runaway trolley is about to kill five innocent people on the track ahead. You are standing next to a large stranger on a footbridge above the track. The only way to save the five people is to push the stranger off the bridge onto the track, killing him but stopping the trolley. What should you do?

An act utilitarian would say that you should push the stranger. This would result in one death instead of five, thereby minimizing overall suffering and maximizing utility. The action itself may seem abhorrent, but for the act utilitarian, only the consequences for well-being matter.

This sort of dilemma can also arise in movies. In The Dark Knight, Batman faces a choice between saving his love Rachel or saving Harvey Dent, a public figure crucial to fighting crime in Gotham. Batman wants to save Rachel, but as the Joker points out, her death would result in less overall suffering than Dent’s death plunging the city back into chaos. Ultimately, Batman tries to save Rachel anyway, arguably failing to act as an act utilitarian would recommend.

Rule Utilitarianism

Despite generating some intuitively correct answers, act utilitarianism also seems to justify actions that violate common moral norms, like pushing an innocent person to their death. Rule utilitarianism is an attempt to accommodate this concern while still maximizing overall utility.

According to rule utilitarianism, the right action is the one that conforms to the general rule that, if universally followed, would produce the greatest overall utility. The rule utilitarian asks not which action has the best consequences in this case, but which general policy would have the best consequences if everyone always followed it.

So in the trolley case, even if pushing the stranger would maximize utility, a rule utilitarian might argue that “Do not intentionally kill innocent people” is a rule that, if universally adopted, would result in greater utility than “Kill innocent people whenever it maximizes utility in that case.” We should adopt it as a general principle even if violating it would be optimal in certain rare situations.

An example of rule utilitarianism in film might be the “Prime Directive” in Star Trek, which prohibits Starfleet crews from interfering with the development of alien civilizations, even to help them. The idea is that a general policy of non-interference does more good (or less harm) in the long run than a policy of judging when to intervene on a case-by-case basis. Particular interventions might help, but an absolute rule is best overall.

Maximizing vs. Satisficing Utilitarianism

Another important distinction is between maximizing and satisficing utilitarianism. Maximizing utilitarianism says we should always choose the action that yields the absolute highest utility possible. If we can save either 10 or 11 lives, we must save 11. Any less is wrong.

Satisficing utilitarianism, in contrast, says that we are morally required only to do what yields sufficient utility, not literally the maximum. As long as we save a decent number of people, we’ve acted rightly – even if in theory we could have saved more.

The status of this distinction is controversial, but it seems to fit with common sense in some cases. Imagine that in E.T., Elliott has a choice between spending hours helping E.T. return home and spending that time collecting money to save thousands of starving children. Maximizing utilitarianism would say Elliott is obligated to abandon E.T. for the greater good. But this seems wrong. Saving E.T. does enough good to be permissible, even if there was a way to help more people in need.

Problems with Utilitarianism

Despite its intuitive appeal, utilitarianism faces some serious challenges. One problem is that it seems overly demanding, requiring us to sacrifice our own interests and even deeply held moral convictions whenever doing so would maximize overall utility.

Imagine that in The Lion King, Simba could save many more animal lives by sacrificing his friend Pumbaa to appease the vicious hyenas. A strict utilitarian calculation might require Simba to betray his friend for the greater good. But this seems to violate the commonsense principle of loyalty and the idea that we have special duties to those close to us.

Similarly, utilitarianism seems to require us to donate most of our income to highly effective charities, since the value of a dollar to someone in extreme poverty is much greater than to a middle-class person in a rich country. But even if this is admirable, it seems wrong to say those who donate less are acting immorally.

Another issue is the difficulty of actually measuring utility and comparing it across people. How can we precisely quantify happiness or compare the subjective experiences of different individuals? Utilitarianism presupposes that we can make fine-grained interpersonal utility calculations, but in practice that seems impossible or at least highly uncertain.

A deeper worry is that utilitarianism fails to respect the separateness of persons. It sees individuals as mere containers of utility to be traded off against each other. But this arguably fails to respect human dignity and inviolable individual rights. So, for example, suppose that that that the only way that save several Jewish children from death is to have sex with a Nazi officer. A utilitarian would seem to say people would be obligated to make this sacrifice for the greater good. But this violates the idea that people have a fundamental right to sexual autonomy that should not be overridden even for a greater benefit. While this simplified example is fictional, Holocaust-era films such as Schindler’s List and Au Revoir Les Enfants explore the ways dilemmas of these types occurred in real life.

A Place for Utilitarianism

That said, utilitarianism remains a powerful framework for moral reasoning, especially in the public policy domain. 19th century thinkers like John Stuart Mill and his wife Harriet Taylor argued for women’s rights, slavery abolition, political freedoms, and legal and social reforms on broadly utilitarian grounds – these changes would dramatically increase overall societal well-being.

In the 20th century, philosopher Peter Singer has applied utilitarian thinking to argue for our obligations to the global poor, animal welfare, and effective altruism – using reason and evidence to do the most good possible. For Singer, utilitarianism provides vital guidance for how to weigh competing interests and make hard choices for the greater good.

For instance, in Jurassic Park, John Hammond wants to open a dinosaur theme park to educate and delight the public. A utilitarian would ask whether the benefits of entertainment and scientific wonder are worth the risks of escaped dinosaurs rampaging and killing. Weighing the numbers, a utilitarian would likely say the potential harms outweigh the benefits and that opening the park (at least without better safeguards) would be unethical since it risks catastrophic loss of life.

On a personal level, utilitarian thinking can prod us to be more impartial and to take seriously the interests of all those affected by our actions, not just those closest to us. In The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf adopts a utilitarian rationale when he tells Frodo, “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.” In other words, we must do what will produce the best overall consequences in the war against Sauron, even if it involves great sacrifice and hardship.

So while utilitarianism faces important limits, it remains a vital tool for expanding our moral circle and guiding difficult trade-offs, especially for policymakers and leaders. We should not be strict utilitarians, but utilitariann thinking deserves a central place in our moral reasoning.

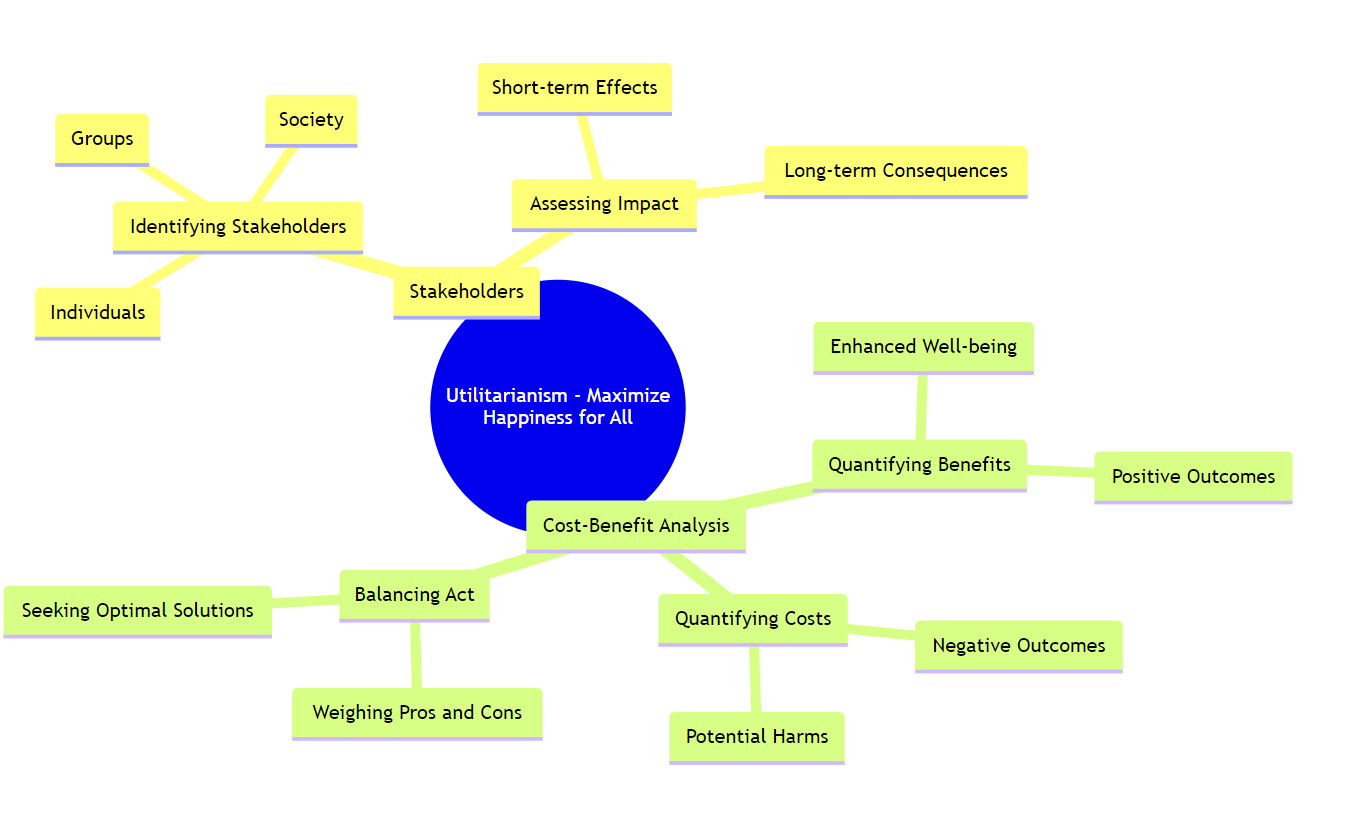

Graphic: Utilitarianism

Glossary: Utilitarianism

|

Act Utilitarianism |

The view that the morally right action is the one that produces the greatest overall utility or happiness in a specific situation, emphasizing the consequences of individual actions. |

|

Harriet Taylor Mill |

Collaborator and wife of John Stuart Mill, she was instrumental in developing and advocating for social and political reforms, including women’s rights and abolition of slavery. |

|

John Stuart Mill |

A 19th-century philosopher known for his contributions to utilitarianism, advocating for political freedoms, women’s rights, and social reforms. |

|

Maximizing Utilitarianism |

Dictates choosing the action that maximizes utility or well-being, requiring the highest possible good in every situation. |

|

Peter Singer |

A contemporary philosopher who applies utilitarian principles to address global poverty, animal welfare, and effective altruism. |

|

Rule Utilitarianism |

Proposes that moral correctness is determined by adherence to rules that, if universally followed, would lead to the greatest utility. |

|

Satisficing Utilitarianism |

Suggests that moral actions need only produce sufficient utility rather than the maximum possible, allowing for a threshold of “good enough” rather than always seeking the greatest outcome. |

|

Utility |

In utilitarian ethics, refers to the well-being, happiness, or satisfaction maximized in decision-making, serving as the standard for determining the best outcomes in moral calculations. |

Questions: Utilitarianism

- Can you think of real-life examples where a utilitarian approach might lead to actions that violate common moral intuitions or principles? How should we resolve such conflicts?

- Do you find act utilitarianism or rule utilitarianism more compelling as a moral framework? What are the strengths and weaknesses of each approach?

- Consider the ethical dilemmas faced by characters in the films mentioned or in another film. Do you think they made the right choices from a utilitarian perspective? Why or why not?

- Do you find the argument for satisficing utilitarianism persuasive? Is it enough to do a sufficient amount of good, or are we obligated to do the absolute most good possible?

- How might a utilitarian approach guide our thinking about contemporary moral issues like global poverty, animal welfare, or existential risk from emerging technologies? What policies would it recommend?

What is Deontology?

Deontology is a normative ethical theory that focuses on the rightness or wrongness of actions themselves, as opposed to the rightness or wrongness of the consequences of those actions (as in utilitarianism) or the character of the agent performing the actions (as in virtue ethics). The term “deontology” comes from the Greek word “deon,” meaning duty or obligation.

According to deontologists, certain actions are inherently right or wrong, regardless of their consequences. Lying, for example, would be considered wrong even if it leads to good consequences, because the act of lying itself is morally prohibited. Deontologists believe that there are absolute moral rules that must be followed, such as “Do not lie,” “Do not steal,” and “Do not kill innocent people.”

This is in stark contrast to utilitarianism, which holds that the morally right action is always the one that produces the greatest good for the greatest number. For utilitarians, lying could be morally permissible or even required if it leads to a better outcome. But for deontologists, lying is wrong in itself, regardless of the consequences.

Deontology is also different from ethical egoism, which claims that moral agents ought to do what is in their own self-interest. Deontologists believe that we have moral duties and obligations that transcend self-interest.

Kant’s Categorical Imperative

The most famous deontological theory is that of 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Kant argued that moral requirements are based on a standard of rationality he called the Categorical Imperative (CI).

Kant characterized the CI as an objective, rationally necessary and unconditional principle that we must always follow despite any natural desires or inclinations we may have to the contrary. The CI is a test of proposed maxims (i.e., subjective rules of action, like “I will lie whenever it’s convenient”). It asks whether the maxim can coherently be willed as a universal law.

There are a few key formulations of the Categorical Imperative:

The Universal Law Formulation

One formulation of the CI states that you are to “act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law.” In other words, an action is morally right only if you could consistently will that everyone always act the same way in the same circumstances.

For example, consider the maxim “I will make false promises when it benefits me.” Could you will this to be a universal law? Kant argues that you could not, because in a world where everyone made false promises, no one would trust each other, and the very practice of making promises would break down. The maxim fails the universality test and so making false promises is morally forbidden.

A more complex case occurs in the movie 12 Years a Slave, which tells the story of Solomon Northup—a free black man who is kidnapped and sold into slavery. In a pivotal scene, Northup is ordered by his master, Edwin Epps, to whip his fellow slave Patsey. Northup initially refuses, but Epps insists, threatening to whip Patsey even more severely if Northup doesn’t comply.

Faced with this dilemma, Northup ultimately chooses to whip Patsey, in an attempt to spare her from even worse punishment. From a deontological perspective, this is a challenging case. On one hand, Northup is acting on the maxim “I will participate in the unjust punishment of an innocent person when forced to do so under threat of even greater harm to that person.” This maxim arguably fails the universality test – we could not will a world where everyone participated in unjust punishments under duress.

On the other hand, Northup is in an impossible situation, and he chooses the course of action that he believes will minimize harm to Patsey. In this sense, he is respecting her humanity by trying to protect her from even worse abuse. The film thus illustrates the sometimes tragic conflicts that can arise between competing moral duties in extreme circumstances.

Importantly, the film never suggests that the institution of slavery itself could be justified under the Categorical Imperative. The maxim “I will own and mistreat other human beings when it benefits me” clearly fails the universality test and violates the principle of respecting humanity as an end in itself. The film powerfully condemns slavery as a categorical moral wrong.

The Humanity Formula

Another key formulation of the CI commands us to treat humanity as an end in itself: “Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end.”

This means that we should never use people merely as tools to achieve our goals, but rather respect their inherent dignity as rational agents. We must recognize that each person has their own autonomy and right to make their own choices.

For an example of what this mean, we can consider the movie Lincoln, which portrays President Abraham Lincoln’s efforts to pass the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would abolish slavery. Throughout the film, Lincoln grapples with the moral imperative to end slavery while also navigating the political realities of the time.

In Kantian terms, Lincoln recognizes the inherent dignity and worth of every human being, regardless of race. In a famous letter, he wrote , “if slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” He sees that slavery violates the principle of treating humanity as an end in itself. The slaves are being used merely as means to the ends of their owners, not respected as autonomous rational agents.

At the same time, Lincoln also grapples with the Categorical Imperative in his own actions. He is willing to engage in a degree of political maneuvering and compromise to achieve the greater good of ending slavery. But he refuses to violate his core moral principles, even when it would be expedient.

For example, when his advisors suggest that he delay the amendment until after the war, Lincoln refuses, saying “I am President of the United States, clothed with immense power, and I expect you to procure me those votes.” He recognizes his moral duty to use his power to end the categorical wrong of slavery, even at the cost of political capital.

So Lincoln illustrates the sometimes difficult balance between adhering to categorical moral imperatives and navigating real-world complexities. But throughout, Lincoln remains committed to the core deontological principle of respecting the humanity in every person.

Rights-based Deontology

In addition to Kant’s duty-based approach, another influential strand of deontological thinking focuses on individual rights. The philosopher John Locke argued that individuals have natural rights to life, liberty, and property, which must be respected regardless of consequences. These rights set inviolable side-constraints on what we can do to individuals in the pursuit of overall welfare.

The contemporary philosopher Robert Nozick developed this idea further, arguing that rights act as moral “side-constraints” that limit the permissible actions of individuals and the state. Nozick famously used the example of moral side-constraints in his “Utility Monster” thought experiment: Imagine a being that gets enormously greater gains in utility from any sacrifice of others than those others lose. An unrestricted utilitarian would have to endorse feeding the monster even if it required sacrificing many people. But Nozick argues that those people have inviolable rights that act as side-constraints against such actions, even if respecting those rights leads to less overall utility.

Films about the prison system often powerfully illustrate the importance of respecting prisoners’ basic human rights, even in a context where their freedom has been restricted due to criminal behavior.

In The Shawshank Redemption, the protagonist Andy Dufresne is wrongfully convicted of murder and subjected to brutal treatment in prison. Despite this, he maintains his dignity and asserts his right to pursue education and meaning behind bars. The film suggests that even prisoners retain fundamental human rights that must be respected.

Similarly, In the Name of the Father tells the true story of Gerry Conlon, who was wrongfully convicted of an IRA bombing and spent 15 years in prison. The film depicts the horrific abuses and deprivations Conlon suffered, and his long struggle to assert his innocence and secure his release. It powerfully illustrates the importance of due process rights and the need to protect individuals against wrongful conviction and punishment.

The documentary 13th explores the intersection of race, justice, and mass incarceration in the United States. It argues that the prison system has functioned as a means of racial control and oppression, violating the basic rights of millions of African Americans. The film suggests that respect for individual rights must be at the forefront of any ethical analysis of the criminal justice system.

These films highlight the deontological idea that there are certain fundamental rights that must be respected even in the context of criminal punishment. While society may have a legitimate interest in restricting the liberty of those who violate the law, it cannot completely override their basic human rights in the process. Rights-based deontology insists on inviolable moral side-constraints that protect the dignity and autonomy of all individuals.

Problems with Deontology

Despite its strong appeal, deontology faces some significant challenges, particularly in situations where adhering to moral rules seems to lead to disastrous consequences.

One famous example is the “ticking time bomb” scenario: imagine that a terrorist has planted a bomb in a city that will kill millions, and the only way to find and defuse it is to torture the terrorist for information. A deontologist committed to the absolute prohibition on torture would have to refuse, even if it meant the deaths of millions.

We can see a similar dilemma play out in the film The Dark Knight. Batman has the chance to kill the Joker, a villain who has murdered countless people and vowed to continue his reign of terror. From a utilitarian perspective, there’s a strong argument for taking the Joker’s life in order to save the lives of his future victims. But Batman has a deontological commitment to the rule against killing, which he believes must be upheld even in this extreme situation.

This example illustrates how deontological rules can seem too rigid and inflexible in the face of extreme moral dilemmas. In a situation where millions of lives are at stake, it may seem perverse to adhere to a moral absolute like “do not kill.”

Another challenge for deontology is the potential for conflicting duties. What happens when two moral rules come into conflict? For example, the duty to tell the truth might conflict with the duty to protect someone from harm. Deontology alone doesn’t give us clear guidance on how to resolve such conflicts.

Finally, there’s the question of what duties and rights we actually have. Deontologists often appeal to intuition or rational reflection to ground their claims, but different thinkers have arrived at very different conclusions. Without an agreed-upon foundation, it can be difficult for deontology to provide definitive moral guidance.

A Place for Deontology

Despite these limitations, deontology remains an essential part of our moral thinking. The idea that individuals have inviolable rights and that certain actions are wrong regardless of consequences seems to be a core part of commonsense morality. Even if we don’t think rights are absolute, most of us place a strong thumb on the scale against violations of individual autonomy.

Moreover, deontological constraints can provide a crucial check on utilitarian reasoning. In a pure utilitarian framework, the majority could always in principle override the rights of the minority for the greater good. Deontology insists on limits to such trade-offs, asserting the separateness of persons and the inviolability of certain individual prerogatives.

We see the importance of deontological side-constraints even in largely utilitarian policy decisions. For instance, in deciding whether to approve a new drug, the FDA must weigh the potential benefits against the risks. But there are also strict deontological constraints in place, in the form of requirements for informed consent from participants in drug trials. We recognize the right of individuals to make free choices about what risks to bear, even if violating that right might lead to faster drug approvals and greater net benefits.

So while deontology may not be the whole of morality, it remains an indispensable part of it, providing a necessary counterweight to utilitarian aggregation and ensuring respect for the separateness and inviolability of individual persons.

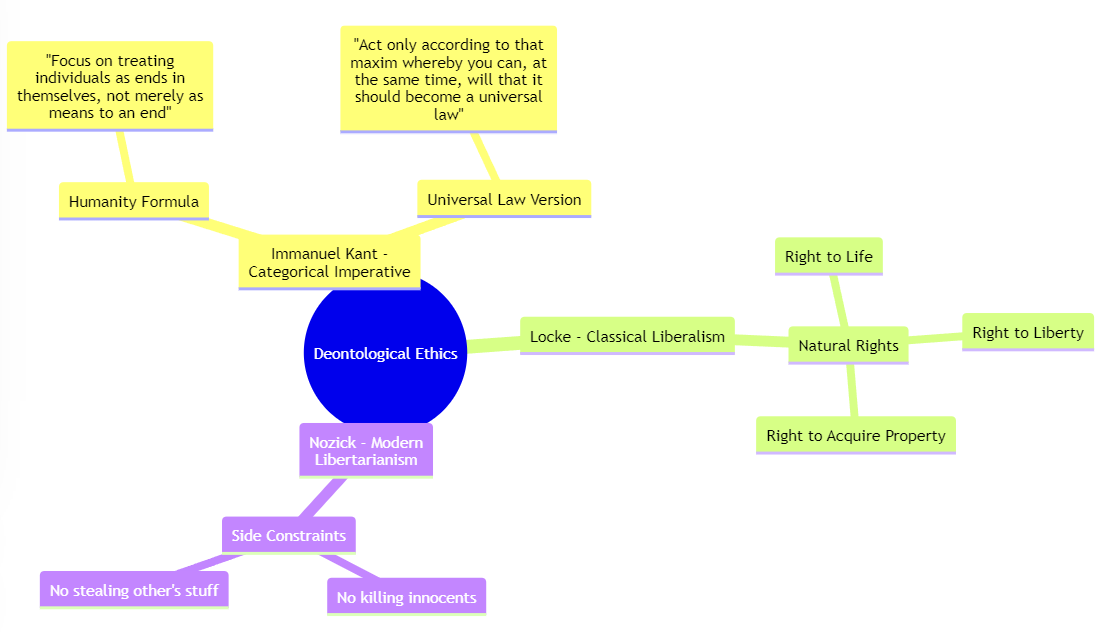

Graphic: Varieties of Deontology

Glossary: Deontology

|

Categorical Imperative |

A foundational concept in Immanuel Kant’s philosophy, which asserts that moral actions must be based on universalizable maxims that everyone MUST follow. |

|

CI: Humanity Formulation |

Another key formulation of Kant’s Categorical Imperative, which commands that humanity be treated always as an end, and never merely as a means. This emphasizes respecting the inherent dignity and worth of every individual by recognizing their autonomy and rationality. |

|

CI: Universal Law Formulation |

One formulation of Kant’s Categorical Imperative, which states that an action is morally right if its maxim can be willed as a universal law without contradiction. This formulation tests whether a maxim can be universally applied without leading to illogical or undesirable outcomes. |

|

Deontology |

A normative ethical theory focusing on the rightness or wrongness of actions themselves, rather than the consequences of those actions. It argues for adherence to absolute moral rules, such as duties not to lie or kill, regardless of the outcomes. |

|

Immanuel Kant |

An 18th-century German philosopher who founded deontological ethics, emphasizing duties and moral laws based on rationality. His philosophy introduced the Categorical Imperative, a principle demanding that actions conform to universalizable maxims respecting human dignity and autonomy. |

|

John Locke |

A 17th-century philosopher known for his theories on liberalism and natural rights, arguing that individuals inherently possess rights to life, liberty, and property, which the state must protect. |

|

Natural Right (Locke) |

Rights that John Locke argued are inherent and inalienable, including life, liberty, and property. Locke maintained that these rights are fundamental to human nature and must be preserved by society and government. |

|

Robert Nozick |

A philosopher known for his libertarian views, arguing against utilitarianism and for the protection of individual rights as side-constraints. His work challenges large-scale state interventions and supports a minimal state, primarily to enforce contracts and protect individuals from harm. |

|

Side-constraint |

A concept in ethical and political philosophy, notably developed by Robert Nozick, that argues certain rights (like those to life and property) set limits on the actions of individuals and governments, acting as constraints that cannot be violated, even for utilitarian reasons of greater overall good. |

Questions: Deontology

- How does the film 12 Years a Slave illustrate the tensions and conflicts that can arise between competing moral duties? Do you think the protagonist made the right choice in the whipping scene?

- What can we learn from Lincoln’s approach to balancing deontological principles with pragmatic political realities? Is there a point at which compromise becomes morally unacceptable?

- Do you agree that there are certain inviolable individual rights that must be respected regardless of consequences, as rights-based deontologists argue? If so, what are those rights and why are they so important?

- How do films about the prison system, like The Shawshank Redemption and 13th, highlight the importance of respecting the basic human rights of even those who have committed crimes? What are the limits of those rights?

- In the “ticking time bomb” scenario, would you agree with a deontologist that torture is always wrong, even if it could save millions of lives? Why or why not?

What is Virtue Ethics?

Virtue ethics is a normative ethical theory that emphasizes the virtues or moral character, in contrast to other frameworks that emphasize duties or rules (deontology) or the consequences of actions (utilitarianism). Virtue ethics is primarily concerned with the moral agent – what kind of person one should strive to be.

The central question in virtue ethics is not “What should I do?” but “What kind of person should I be?” or “How should I live?” The basic idea is that what matters most morally is the cultivation of good character traits or virtues, such as courage, justice, temperance, and wisdom.

Different thinkers have proposed different lists of essential virtues and offered different accounts of how they are grounded and related. Let’s look at some of the most influential formulations.

Aristotelian Virtue Ethics

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle is often considered the father of virtue ethics. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues that the highest good for human beings is eudaimonia, often translated as happiness, well-being, or flourishing. Eudaimonia is achieved through the cultivation of virtue.

For Aristotle, virtues are character traits that enable us to live well and achieve eudaimonia. They are the mean between two extremes – for example, courage is the mean between cowardice and recklessness. Virtues are developed through practice and habit.

We can see an illustration of Aristotelian virtue ethics in the film Groundhog Day. The protagonist, Phil Connors, starts off as a selfish, arrogant, and cynical man. But when he finds himself trapped in a time loop, reliving the same day over and over, he is forced to re-evaluate his life.

Through the course of the film, Phil undergoes a transformation. He develops compassion, as he learns to care about the people around him and help them with their problems. He cultivates patience and perseverance, as he works to master new skills and improve himself. He learns humility and the value of relationships.

By the end of the film, Phil has become a different person – one who embodies many of Aristotle’s virtues. And as a result, he achieves a kind of eudaimonia – a deep sense of happiness and fulfillment that comes from living a good life.

Confucian Virtue Ethics

Confucianism, the ethical tradition based on the teachings of the ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius, also focuses on virtue and character. For Confucius, the key virtues are ren (benevolence, humaneness), yi (righteousness), li (propriety, rites), zhi (knowledge), and xin (integrity).

Central to Confucian ethics is the idea of filial piety – respect and care for one’s parents and ancestors. This is seen as the foundation for all other virtues and relationships.

The film Mulan illustrates Confucian virtues in action. Mulan, the protagonist, is driven by a strong sense of filial piety – she disguises herself as a man and takes her father’s place in the army to protect him.

Throughout her journey, Mulan demonstrates courage, perseverance, and integrity. She stays true to herself even while hiding her identity, and her authentic self ultimately becomes her strength.

Mulan also embodies the Confucian ideal of the “junzi” or “noble person” – one who cultivates virtue and acts with benevolence and righteousness. By the end of the film, Mulan has become a true hero, not just through her martial prowess, but through her moral character.

Natural Law Virtue Ethics

In the natural law tradition, virtues are grounded in human nature and the natural order. The idea is that by living in accordance with our rational nature and the natural law, we can achieve happiness and fulfillment.

The most famous proponent of this view is Thomas Aquinas, who synthesized Aristotelian virtue ethics with Christian theology. For Aquinas, the cardinal virtues are prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance, and the theological virtues are faith, hope, and charity.

The film A Hidden Life depicts the story of Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian farmer who refused to fight for the Nazis in World War II due to his Catholic faith and moral convictions (and s executed for it). Jägerstätter’s actions can be seen as a powerful example of living according to one’s conscience and the natural law, even in the face of extreme adversity.

Jägerstätter demonstrates the virtues of fortitude in standing up for his beliefs, justice in refusing to participate in the evils of Nazism, and faith in remaining true to his religious convictions. His story illustrates the natural law idea that there are objective moral truths grounded in human nature that we must adhere to, regardless of the consequences.

Care Ethics

Care ethics, developed by philosophers such as Carol Gilligan and Nel Noddings, emphasizes the virtue of care and the moral significance of relationships and dependencies.

In contrast to the focus on impartial rules or consequences in other ethical theories, care ethics highlights the importance of emotional sensitivity, empathy, and attentiveness to context in moral life. It sees caring relationships as the foundation of morality.

The film Frozen beautifully illustrates the central ideas of care ethics. The heart of the story is the relationship between the sisters Anna and Elsa. When Elsa’s magical powers cause her to inadvertently plunge the kingdom into eternal winter, she flees in fear and isolation.

But Anna refuses to give up on her sister. She embarks on a perilous journey to find Elsa and bring her home, demonstrating the depth of her care and commitment. Ultimately, it is Anna’s act of true love – sacrificing herself to save Elsa – that breaks the curse and restores harmony to the kingdom.

Frozen highlights the moral importance of caring relationships, empathy, and self-sacrifice. It shows how attentiveness to particular people and contexts – in this case, the bond between sisters – can be more morally significant than abstract rules or principles.

These are just a few of the many formulations of virtue ethics, each offering a rich perspective on the moral life. Despite their differences, they all share a focus on character, moral excellence, and what it means to live well.

Tables: Different Traditions, Different Virtues

|

Virtue (Ethical Tradition) |

Explanation |

|

Courage (Aristotelian) |

This virtue involves facing fear and acting rightly in the face of potential harm, ideally balanced between the extremes of recklessness and cowardice. It is essential for achieving moral goals and upholding other virtues through action. |

|

Temperance (Aristotelian) |

Represents moderation and self-control regarding physical pleasures and desires. Temperance is about finding the mean between excess and deficiency, making it critical for personal balance and ethical behavior. |

|

Justice (Aristotelian) |

Pertains to fairness in interpersonal actions, distribution of resources, and recognition of rights and merits. Justice as a virtue involves giving each individual what they rightly deserve according to their actions and circumstances, upholding societal harmony and order. |

|

Ren (Confucian) |

Translated as benevolence or humaneness, Ren is the virtue of showing kindness and compassion towards others, forming the foundational aspect of all social interactions and the moral fabric of society. |

|

Yi (Confucian) |

Righteousness or the moral disposition to do good, Yi involves acting justly and morally in social affairs, and maintaining one’s moral integrity in decision-making, often aligned with societal norms and the welfare of the community. |

|

Li (Confucian) |

Encompassing ritual, propriety, and etiquette, Li is the virtue of acting appropriately according to one’s social roles and contexts. It is crucial for maintaining order and respect within social interactions, reflecting a deep understanding of one’s duties and expectations in society. |

|

Prudence (Natural Law) |

Involves practical reason to discern the true good in every circumstance and to choose the right means of achieving it. As a cardinal virtue, prudence guides other virtues by directing them to be applied according to correct reasoning and moral law, integral for moral decisions that align with natural law. |

|

Justice (Natural Law) |

Focuses on giving others what is rightfully theirs and is rooted in the idea of a natural order. This virtue under Natural Law emphasizes the objective standards of right and wrong that govern human behavior, suggesting a universal law that applies to all human actions. |

|

Care (Care Ethics) |

Central to care ethics, care involves maintaining and nurturing concrete, valuable interpersonal relationships. This virtue emphasizes understanding, empathy, and responsiveness to the needs of others, prioritizing relational obligations and the context of human interdependence. |

Problems with Virtue Ethics

While virtue ethics provides valuable insights into moral character and the good life, it also has some limitations. One challenge is that it doesn’t always give clear guidance on how to act in specific situations.

In Frozen, Anna faces a dilemma when she learns that her true love, Prince Hans, is actually a villainous schemer. From a virtue ethical perspective, Anna should cultivate the virtues of wisdom and discernment to avoid being deceived. But in the moment of confrontation, virtue ethics alone doesn’t tell Anna exactly what to do. She must also consider the utilitarian consequences of her actions (will exposing Hans save the kingdom?) and her (deontological) duties to her sister and her people.

Another issue is that virtues can sometimes conflict with each other. In Mulan, the protagonist’s commitment to honesty and integrity clashes with her duty of filial piety when she decides to take her father’s place in the army. Mulan must navigate between these competing virtues, but virtue ethics itself doesn’t provide a clear hierarchy or decision procedure for resolving such conflicts.

Moreover, virtue ethics has been criticized for focusing too heavily on the individual’s character, potentially neglecting the role of social and institutional factors. In Groundhog Day, Phil’s journey of self-improvement is admirable, but it’s also enabled by his unique circumstances – being stuck in a time loop. In the real world, a person’s ability to cultivate virtues may be constrained by their social environment, economic conditions, and other external factors beyond their control.

These limitations suggest that while virtue ethics is a valuable perspective, it may need to be complemented by other moral considerations, such as rules, duties, and consequences, to provide comprehensive guidance.

A Place for Virtue Ethics

One of the key insights of virtue ethics is that morality is not just about individual actions or rules, but about the development of character over time. Many films depict this process of moral progress, showing how characters grow, learn, and become better people through their experiences and choices.

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet starts out as a sharp-witted but somewhat judgmental young woman. Over the course of the story, she learns to question her assumptions, to be more open-minded and empathetic. Her moral progress is exemplified in her changing attitude towards Mr. Darcy. Initially dismissive of him as proud and aloof, Elizabeth eventually recognizes his true virtues – his integrity, loyalty, and capacity for growth. Her own journey towards greater understanding and compassion mirrors Darcy’s transformation from apparent arrogance to genuine humility and kindness.

Selma, a historical drama about the 1965 voting rights marches, portrays the moral progress of a community and a nation. The film shows how the courage, perseverance, and strategic wisdom of civil rights activists like Martin Luther King Jr. and John Lewis helped to shift public consciousness and enact political change. The virtues embodied by these leaders inspired others to join the cause, gradually bending the arc of history towards greater justice and equality.

In American History X, the protagonist Derek Vinyard undergoes a profound moral transformation. Starting out as a neo-Nazi skinhead, full of hatred and prejudice, Derek’s experiences in prison and his relationship with his former high school teacher lead him to renounce his racist beliefs. He comes to understand the toxicity of his prior worldview and strives to prevent his younger brother from following the same path. Derek’s story powerfully illustrates how even the most misguided individuals can change and grow through the cultivation of virtues like empathy, open-mindedness, and compassion.

Barbie, a 2023 film based on the iconic doll franchise, uses fantasy and comedy to explore themes of identity, conformity, and self-discovery. Barbie, a doll living in the seemingly perfect world of Barbieland, starts to question her purpose and venture into the real world. Through her interactions with diverse characters and situations, Barbie learns to think for herself, to embrace her unique quirks and interests, and to define her own version of a meaningful life. Her story can be seen as a virtue ethical journey towards authenticity, autonomy, and self-knowledge.

These films, spanning different genres and eras, all illustrate the central role of moral development in the human experience. They show how characters can progress from states of ignorance, prejudice, or conformity towards greater wisdom, justice, and authenticity. Virtue ethics provides a powerful framework for making sense of these arcs – it recognizes that becoming a good person is a lifelong process that requires the cultivation of admirable qualities through experience, reflection, and choice.

At the same time, these stories also highlight how virtue intersects with other moral considerations. In Selma, the virtues of the civil rights leaders are channeled towards deontological ends – securing the basic rights and dignities owed to all people. In Barbie, the protagonist’s self-discovery is framed in terms of the existentialist ethics of authenticity – the imperative to define one’s own values and life path.

These examples suggest that while virtue ethics is a powerful perspective, it is enriched by dialogue with other moral frameworks. Virtue is not developed in isolation, but through engagement with the duties we owe to others, the consequences of our actions, and the social and political realities we navigate.

As we seek to live well and become better people, the insights of virtue ethics can provide both guidance and inspiration. Films that depict moral progress remind us that character is not static, but an ongoing project – one that requires effort, reflection, and a willingness to learn from our experiences and relationships. By striving to cultivate virtues and live with integrity, we can write our own stories of moral growth and contribute to the broader ethical progress of our communities and our world.

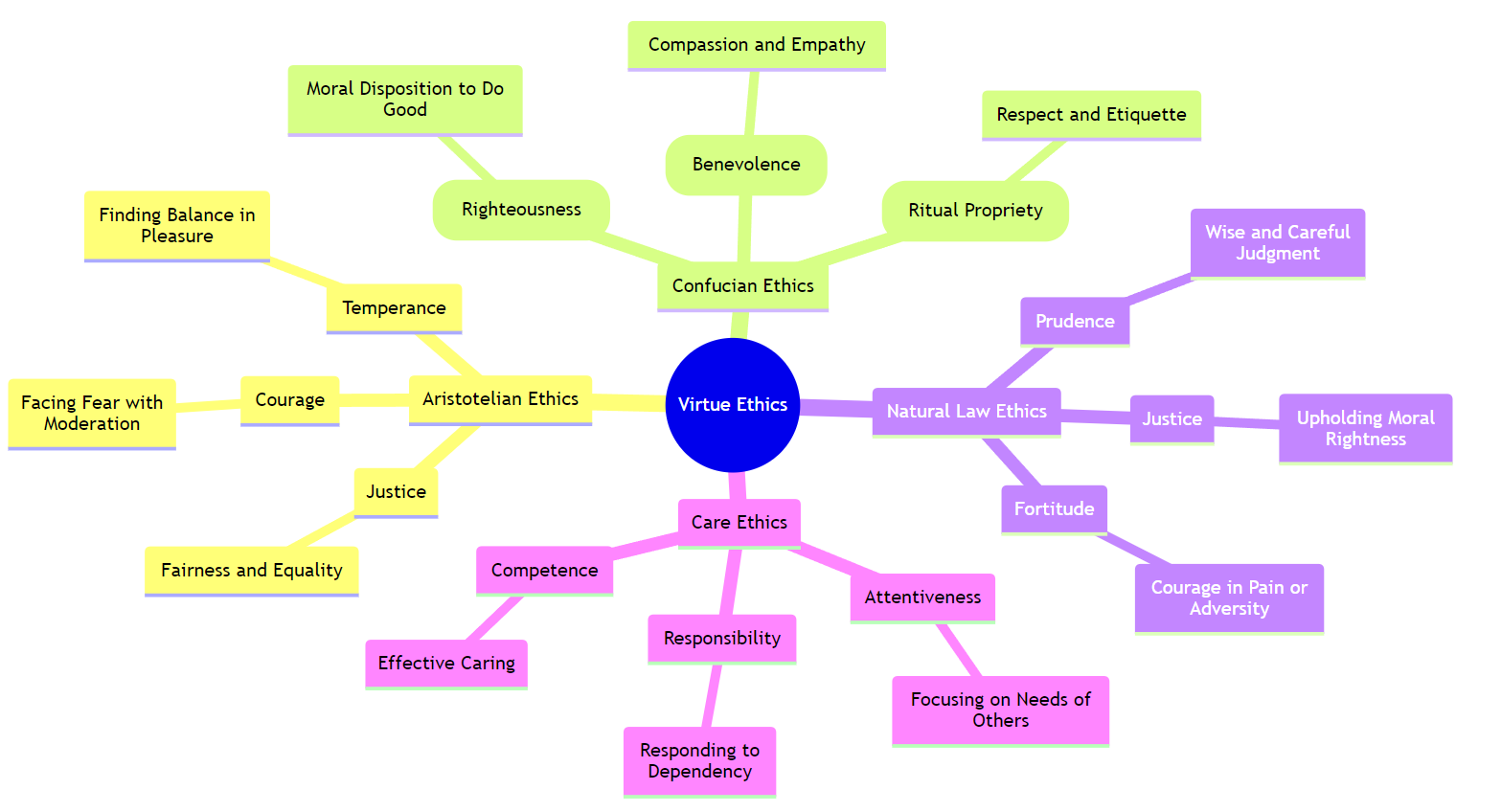

Graphic: Varieties of Virtue Ethics

Glossary: Virtue Ethics

|

Aristotle |

An ancient Greek philosopher who founded virtue ethics, focusing on the development of good character traits (virtues) as the key to achieving eudaimonia, or flourishing. His ethical theory emphasizes finding the mean between extremes in traits like courage and temperance. |

|

Eudaimonia |

A term from Aristotelian ethics, often translated as happiness, well-being, or human flourishing. It represents the highest good and ultimate aim of human endeavors, achieved through the cultivation of virtues and living in accordance with reason. |

|

Confucius |

An ancient Chinese philosopher whose teachings form the basis of Confucianism, emphasizing moral integrity, propriety, and the importance of family and social harmony. He advocated for the cultivation of virtues such as benevolence, righteousness, and respect for tradition to achieve a well-ordered society. |

|

Natural Law Theory |

A philosophical and ethical theory that posits the existence of a law whose content is set by nature and that therefore has validity everywhere. The theory asserts that certain rights and morals are inherent in human nature and can be universally understood through human reason. |

|

Care Ethics |

An ethical theory emphasizing the importance of interpersonal relationships and care as a fundamental ethical orientation. Care ethics contrasts with more justice-oriented moral theories, focusing on empathy, compassion, and the context of relationships rather than abstract principles. |

|

Thomas Aquinas |

A medieval philosopher and theologian who integrated Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology. He is known for his contributions to natural law theory, arguing that human laws are rooted in universal divine laws and the purpose of human life is to achieve the natural order intended by divine will. |

|

Virtue |

In ethical philosophy, particularly within Aristotelian and other virtue ethics traditions, a virtue is a trait or quality deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. |

Questions: Virtue Ethics

- Which virtues do you think are most essential for living a good life? Why? How do they relate to the different conceptions of virtues discussed in the text (Aristotelian, Confucian, natural law, care ethics)?

- Do you agree that character and moral development should be the primary focus of ethical thinking, as virtue ethicists argue? Or do you think other factors, like rules, duties, or consequences, are more important?

- How do the examples of Groundhog Day, Mulan, and A Hidden Life illustrate the key ideas of virtue ethics? What do they suggest about the nature of virtues and how they are developed?

- Can you think of other examples from films, literature, or real life that powerfully depict the cultivation of virtues and moral progress over time?

- One challenge for virtue ethics is that it seems to focus on individual character at the expense of social and institutional factors. How much do you think a person’s ability to develop virtues depends on their circumstances and environment? What role should society play in promoting virtue?

Ethics at Scale: Political Philosophy

While much of our discussion so far has focused on individual moral decision-making, ethics also plays a crucial role at the societal level. Political philosophy is concerned with the ethical principles that should guide the design and functioning of social institutions, laws, and public policies.

One of the most important figures in modern political philosophy is John Rawls, whose theory of justice as fairness has shaped debates about equality, rights, and the proper role of government.

Rawls’ Social Contract Theory

In his seminal work, A Theory of Justice, Rawls proposes a thought experiment to derive principles of justice for a fair and well-ordered society. He imagines a hypothetical “original position” in which rational individuals, behind a “veil of ignorance,” choose the basic structure of their society.

The key idea is that these individuals do not know their particular place in society – their class, race, gender, abilities, or conception of the good life. Behind the veil of ignorance, they must choose principles that they would be willing to live under, regardless of their eventual position.

Rawls argues that, under these conditions, individuals would agree on two fundamental principles of justice:

- The Liberty Principle: Each person has an equal right to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties, compatible with a similar scheme of liberties for all.

- The Difference Principle: Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both (a) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged, and (b) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity.

The first principle guarantees a robust set of basic rights and freedoms for all citizens. The second allows for inequalities, but only if they improve the situation of the worst-off and if everyone has a fair shot at attaining advantaged positions.

Rawls’ theory provides a powerful framework for evaluating the justice of social institutions. It suggests that a fair society is not necessarily one with perfect equality of outcomes, but one in which inequalities are justified by benefiting the least well-off and where everyone has equal basic liberties and fair opportunities.

The Original Position in Star Wars

Let’s see how this might work in practice. Imagine a group of individuals from the Star Wars galaxy coming together to choose the principles that will shape their society. Following Rawls’ framework, these individuals are situated behind a “veil of ignorance” – they do not know their particular place in the society they are designing.

They do not know if they will be human, Wookiee, Twi’lek, or any other sentient species. They are unaware if they will be born into wealth on a core world like Coruscant or into poverty on a remote outer rim planet. They do not know their gender, abilities, religious beliefs, or personal preferences. They may even be uncertain if they will be born as an organic being or as a droid.

Under these conditions of uncertainty, what principles would these individuals choose to govern their galaxy? According to Rawls, they would do a few things.

Firstly, they would likely agree on a principle of equal basic liberties for all sentient beings. Regardless of species or cybernetic status, every individual would be guaranteed fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, association, and conscience. This principle would protect the diverse ways of life and beliefs found across the Star Wars galaxy, from the spiritual practices of the Jedi to the cultural traditions of the various alien civilizations.

Secondly, the individuals in the original position would likely choose a principle of fair equality of opportunity. They would want to ensure that important roles and positions in society are open to all based on merit and ability, rather than unfairly restricted by factors like species, planet of origin, or family connections. This principle would work against the kind of systemic discrimination faced by non-human species in parts of the Star Wars galaxy and would ensure that talented individuals from all backgrounds have a fair shot at becoming Jedi, senators, or starship pilots.

Thirdly, the participants might agree on a difference principle for the distribution of wealth and resources. Knowing that they could end up as a moisture farmer on Tatooine or a factory worker on Corellia, they would want to ensure that economic inequalities are arranged to benefit the least advantaged. This might involve policies to redistribute wealth from the opulent core worlds to the poorer outer rim territories, or to ensure a basic standard of living and social services for all citizens of the galaxy.

The original position thought experiment could also be used to consider other issues of justice in the Star Wars context. For instance, what principles should guide the treatment of droids and other artificial intelligences? From behind the veil of ignorance, individuals might agree on robust rights and protections for these beings, knowing they could potentially be one. This could lead to a society more like the benevolent droid-human partnerships of Luke Skywalker and R2-D2, rather than the exploitative droid servitude seen in parts of the galaxy.

By applying Rawlsian principles, we can imagine a more just and equitable version of the Star Wars galaxy – one in which the core values of liberty, equality, and fair opportunity shape institutions and practices. While the specifics would need to be worked out, the original position provides a powerful starting point for envisioning a society that respects the rights and dignity of all its diverse members.

Of course, this thought experiment is not without its limits or potential objections. Some might argue that the vast differences between species in the Star Wars universe make the original position less applicable, or that the presence of the Force complicates questions of fairness and equality. Nevertheless, the exercise of reasoning behind the veil of ignorance can still yield valuable insights and aspirations for a more just galaxy far, far away.

Glossary: Political Philosophy

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Difference Principle (Rawls) |

A principle from Rawls which says that social and economic inequalities should: (a) benefit the least advantaged the most, and (b) be attached to positions and offices that everyone has a fair and equal opportunity to access. |

|

Fair Equality of Opportunity (Rawls) |

Rawls’s principle that people with similar abilities and skills should have equal access to positions and offices, regardless of their social or economic backgrounds. This principle aims to correct not only legal but also unfair social and economic disadvantages. |

|

John Rawls |

An important American philosopher from the 20th century known for his theory of justice as fairness, which includes ideas like the original position, veil of ignorance, and principles of liberty and difference. His theories try to balance liberty and equality in a fair way. |

|

Liberty Principle (Rawls) |

One of Rawls’s principles of justice, which states that each person has an equal right to the most extensive basic liberties, like political freedom, free speech, and personal property, as long as everyone has the same liberties. |

|

Original Position |

A hypothetical scenario described by John Rawls where people choose principles of justice from a position of equality, without knowing their place in society. This thought experiment aims to ensure the chosen principles are fair and impartial. |

|

Social Contract Theory |

A theory from the 1600s and 1700s that says people have agreed, either directly or indirectly, to give up some of their freedoms and follow the authority of a ruler or the will of the majority, in exchange for protection of their remaining rights. |

Questions: Political Philosophy

- If you were in the Original Position and didn’t know if you’d be a human, alien, or a droid in the Star Wars universe (or in the real world!), what rules would you want everyone to follow? Why might it be important not to know your species or planet?

- Given the variety of species in Star Wars (and the variety of humans in or world), how would Rawls’ idea of equal basic liberties work? Would some species need different rights or freedoms?

- Why would people in the Original Position (regardless of their “world”) likely choose a principle of fair equality of opportunity? How would this help someone born on a poorer planet or as a less privileged species?

- How might the principle that inequalities should benefit the least advantaged (the difference principle) be applied in the Star Wars universe? Would this principle mean taking resources from rich planets like Coruscant to help poorer areas like Tatooine? What about in our world?

- How could the principle of freedom of speech, association, and conscience protect the diverse cultures in Star Wars, from Jedi practices to local traditions? (Again, you can also think about our world!).

References

Alexander, Larry, and Michael Moore. 2021. “Deontological Ethics.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2021. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/ethics-deontological/.

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by W. D. Ross. Internet Classics Archive. http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.html

Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Library of Economics and Liberty. https://www.econlib.org/library/Bentham/bnthPML.html

Driver, Julia. “The History of Utilitarianism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history/

Gilligan, Carol. 1993. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Harvard University Press.

Hursthouse, Rosalind, and Glen Pettigrove. 2023. “Virtue Ethics.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Fall 2023. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/ethics-virtue/.

Hursthouse, Rosalind, and Glen Pettigrove. “Virtue Ethics.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-virtue/

Kant, Immanuel. 2009. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Translated by H. J. Paton. Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Kraut, Richard. “Aristotle’s Ethics.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-ethics/

Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/11224/11224-h/11224-h.htm

Moseley, Alexander. n.d. “Egoism.” In Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed January 19, 2024. https://iep.utm.edu/egoism/.

Nathanson, Stephen. 2024. “Utilitarianism, Act and Rule.” In Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/util-a-r/.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Beyond Good and Evil. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4363/4363-h/4363-h.htm

Noddings, Nel. 2003. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. University of California Press.

Nozick, Robert. 2013. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books.

Rand, Ayn. 1964. The Virtue of Selfishness. Signet.

Rawls, John. 2009. A Theory of Justice. Harvard University Press.

Ross, W. D. 2002. The Right and the Good. Oxford University Press.

Shaver, Robert. 2023. “Egoism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Spring 2023. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/egoism/.

Shea, Brendan. 2023. Ethical Explorations: Moral Dilemmas in a Universe of Possibilities. Rochester, MN: Thoughtful Noodle Books.

Singer, Peter. 2023. “Ethics.” In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/ethics-philosophy.

Sinnott-Armstrong, Walter. 2023. “Consequentialism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Winter 2023. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/consequentialism/.

Sinnott-Armstrong, Walter. “Consequentialism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consequentialism/

Slingerland, Edward. “Confucius.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/confucius/

Tong, Rosemarie, and Nancy Williams. “Feminist Ethics.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-ethics/

Wolf, Susan. 1982. “Moral Saints.” The Journal of Philosophy, vol. 79, no. 8, pp. 419-439. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2026228