5 Arguing About God: Design, Evil, and Fiction

A Little More Logical | Brendan Shea, PhD

Step into the contemplative world of “The Wired Kebab,” where three friends – Orion Quest, a software developer and theist; Ivy Pathogen, a medical student and atheist; and Harper Chronicle, a history teacher and agnostic – engage in a profound exploration of God, logic, and the nature of belief. Through a series of thought-provoking arguments and counterarguments, they navigate the complex terrain of the Argument from Design, the Problem of Evil, and the sociological dimensions of religion. Drawing upon insights from great thinkers like David Hume and Blaise Pascal, as well as contemporary examples from science, technology, and popular culture, this chapter invites readers to critically examine their own beliefs and assumptions about the divine. As Orion, Ivy, and Harper grapple with the implications of their diverse worldviews, they demonstrate the power of respectful dialogue and intellectual humility in the face of life’s ultimate questions. Join them on this philosophical journey, where the boundaries of faith, reason, and fiction blur, and where the quest for understanding is as vital as the answers themselves.

Learning Outcomes: By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand and evaluate the Argument from Design, including its analogical reasoning, its implications for the nature of the divine, and its potential weaknesses.

- Explain the Theory of Evolution via Natural Selection and how it challenges the Argument from Design by providing an alternative explanation for the apparent complexity and functionality of the natural world.

- Articulate the Problem of Evil and its implications for the existence of an all-powerful, all-good God, with a focus on the distinction between moral and natural evil.

- Assess the strengths and limitations of the Free Will Defense as a response to the Problem of Evil, and consider how different religious traditions approach the issue of suffering.

- Analyze religion from various sociological perspectives, including Marxist, Durkheimian, Weberian, Functionalist, and Symbolic Interactionist accounts, and evaluate the concept of religion as a “useful fiction.”

- Engage with the ideas of Blaise Pascal, particularly his contributions to probability theory, decision theory, and the famous “Pascal’s Wager” argument for belief in God.

Keywords: Theism, Atheism, Agnosticism, Argument from Design, Analogical reasoning, Hume’s Critique of the Design Argument, Evolution via Natural Selection, Problem of Evil, Moral Evil, Natural Evil, Free Will Defense, Abrahamic Religions, Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Marxist account of religion, Durkheimian perspective, Weberian perspective, Functionalist theories of religion, Symbolic interactionism, Religion as a “useful fiction”, Blaise Pascal, Probability, Expected Value, Pascal’s Wager

Introduction: A Friendly Argument

Beneath the humming neon sign of “The Wired Kebab,” a quaint coffee shop nestled on the outskirts of a bustling university town, three friends crossed the threshold into a world of aromatic coffee and contemplative discussions. This late-night sanctuary, adorned with an eclectic mix of vintage posters and modern art, became a melting pot for ideas and conversations. Here, beneath the soft glow of hanging Edison bulbs, Orion Quest, Ivy Pathogen, and Harper Chronicle convened, their friendship forged in the halls of the local community college.

Orion Quest, with his tousled hair and eyes sparkling with a thirst for knowledge, is your typical software developer. His t-shirt, adorned with a retro video game design, shouts out his love for all things digital. Back in his university days, diving deep into algorithms and coding, Orion developed a real fascination for the intricate digital worlds. He views the universe as a sort of massive, celestial software, intricately programmed and operating on a sort of divine algorithm crafted by some higher intelligence. He is a theist, who believes in the existence of an omnipotent (“all-powerful”), omniscient (“all-knowing”), and omnibenevolent (“all-loving” or “entirely good”) good God.

In sharp contrast, there’s Ivy Pathogen. She’s all about precision and focus, traits you’d expect in a med student specializing in infectious diseases. Her mind, honed by the complex world of microbiology, perceives life as a chaotic dance of viruses and bacteria, much like what she observes under her microscope. To Ivy, life is complex, unpredictable, and certainly not the work of any divine being. Her arguments are always razor-sharp, often shaking the very roots of religious beliefs. She is an atheist, who thinks that the God described by Orion doesn’t exist.

Then there’s Harper Chronicle, who often finds herself playing peacemaker in the group. As a high school history teacher, her view on religion is more about its place in society than its spiritual truths. For Harper, religion is a sociological phenomenon, intertwined with human history. Her vivid storytelling brings the past alive, skillfully linking it to modern-day scenarios. She is an agnostic, who holds that existence of the God Orion and Ivy argue about isn’t something we humans can know about. She thinks we ought to withhold belief one way or the other.

The three of them settled into the comfy leather couches of “The Wired Kebab” for what promised to be an intriguing night. Surrounded by the low hum of conversation and the occasional clink of coffee cups, this coffee shop was the perfect setting for their deep dive into faith, belief, and logic. Perched on the edge of discovery, their differing perspectives were set to brew a discussion as complex and varied as the coffee being made behind the counter.Top of Form

The Argument From Design

Orion Quest leaned in, his eyes gleaming with the unmistakable light of someone about to dive deep into a topic they’re passionate about. He took a moment to gather his thoughts, then launched into his explanation, linking the Argument from Design to his love for video games.

“Think about the worlds we explore in video games,” Orion started, his hands moving through the air as if he was drawing invisible lines and shapes. “Take ‘The Legend of Zelda’, for instance. Every puzzle, every dungeon, and every character in that game is there for a specific reason. They’ve been carefully crafted and positioned by the game’s creators. There’s a deliberate design and intelligence behind every part of it, all adding to the game’s immersive experience.”

He paused, checking to see if his friends were keeping up, then continued. “So, if we take this idea and apply it to our universe, the Argument from Design suggests that our universe, much like a video game, shows signs of being designed, which implies there’s a designer behind it. Here’s how I break it down:

- In video games, complex and functional designs, like intricate levels or sophisticated gameplay mechanics, imply the existence of a game designer.

- Our universe exhibits similar complex and functional designs, evident in the laws of physics, the structure of the cosmos, and the intricacies of biological life.

- Therefore, by analogy, the complex and functional designs in our universe imply the existence of a universal designer.”

Now fully immersed in his element, Orion Quest elaborated on his argument with a sense of enthusiasm reserved for those moments when passion and intellect converge.

“Firstly, let’s consider the laws of physics,” he said, tapping his fingers rhythmically on the table. “These laws are not just random or unlawful; they’re finely tuned. Just like in a video game, where the physics engine ensures that each jump, movement, or interaction follows specific rules, our universe operates under a set of precise and predictable laws. This suggests a craft at play, akin to a game designer programming the game’s rules. Without these laws, the universe would be chaotic, much like a game full of glitches and errors.”

“Secondly, think about the complexity of biological life,” Orion continued, “From the intricate DNA structures to the sophisticated mechanisms of cell function, life is a marvel of biological engineering. It’s as if each organism is a tenant, occupying a space in the universe perfectly crafted for it. The complexity of these biological systems, and their seamless integration into the environment, echo the design of intricate game worlds where every character, every creature, has a role to play and a niche to fill.”

“Finally, let’s not overlook the cosmos itself,” he added, gesturing towards the night sky visible through the coffee shop’s window. “The vastness of space, the balance of celestial bodies, the delicate dance of galaxies – it’s all so orderly and harmonious. This order and harmony in the cosmos resemble the careful planning and design of expansive game universes. The way a game developer crafts a vast, exploratory space for players to inhabit, the universe seems to be crafted with similar precision and attention to detail.”

Orion leaned back, his case laid out with a mix of logical reasoning and palpable passion. “Each of these aspects – the laws of physics, the complexity of life, and the order of the cosmos – suggest a design, an intelligent force behind their creation. They are not the products of randomness, but of deliberate, skilled craft, much like the worlds we explore in video games.”

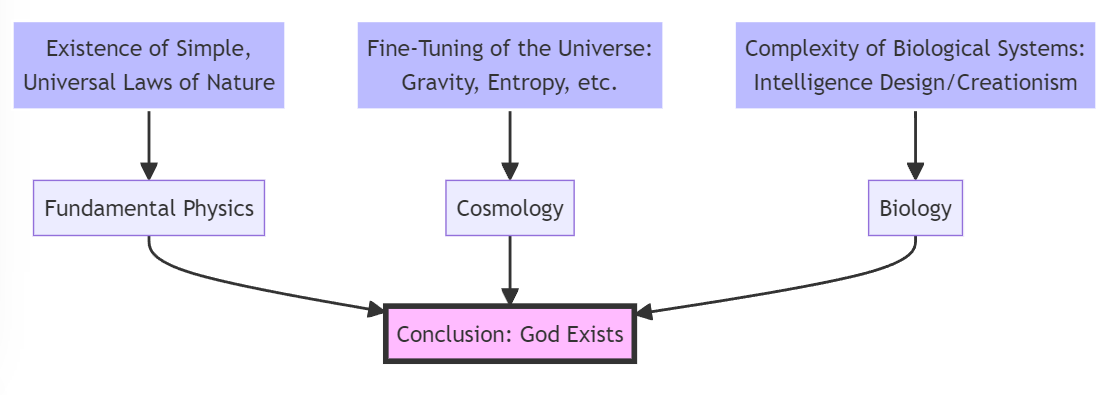

Graphic: The Argument from Design

Hume’s Objection: What Kind of Creator?

Harper Chronicle, with a thoughtful expression, gently interjected to present a counterpoint, drawing from David Hume’s objections to the Argument from Design. She turned to Orion, her voice a blend of respectful challenge and intellectual curiosity.

“Orion, your analogy is fascinating, but let’s consider David Hume’s Critique of the Design Argument, especially regarding the nature of the designer,” Harper began. “Hume argues that if the world is indeed like a machine or, in your analogy, a video game, then the nature of its creator might be very different from the traditional concept of an all-powerful, all-good God.”

She leaned forward, her eyes locked onto Orion’s. “Think about the creators of video games. They are fallible, limited in power and knowledge, and often work as a team. Extending your analogy suggests that the universe’s designer might be similar—imperfect, perhaps one of many, and not necessarily all-good or all-powerful.”

“Moreover,” Harper continued, “the very design of some video games includes elements of conflict, evil, and suffering. If our universe is akin to a game, designed similarly, this could imply that the designer is not wholly benevolent. After all, game developers create challenges and obstacles for players to overcome, not a perfect, trouble-free world.”

“And let’s not forget the diversity of video games themselves,” she added. “There are countless genres, styles, and narratives. This variety could parallel multiple creators or universes, each with different characteristics and rules. Hume’s critique suggests that if the universe is designed, it might not point to a single, all-powerful, all-good God, but rather to a designer or designers with attributes more akin to human game developers.”

Harper concluded her point, her argument a deft weaving of Hume’s philosophy with Orion’s gaming metaphors. “In essence, Hume challenges us to consider the implications of the design analogy more deeply, especially concerning the nature and characteristics of the supposed designer.”

Evolution via Natural Selection: Design Without a Designer

Ivy Pathogen, attentively absorbing the exchange between her friends, found her moment to voice a compelling counterargument. Her demeanor was calm yet assertive, reflecting the precision of her scientific training.

“Let’s consider a different perspective,” Ivy began, her voice steady and clear. “The theory of evolution through natural selection provides a robust explanation for the apparent ‘design’ in biological life, without necessitating a designer. Understanding this theory’s core principles is essential to grasp how it counters the need for a designer.”

“Evolution through natural selection operates on a few basic tenets,” she explained. “First, there is variation in traits within a population. These variations can be anything from animal fur color to plant leaf shape. Second, some of these traits offer a survival advantage in a given environment. The individuals with advantageous traits are more likely to survive and reproduce, passing these traits to the next generation. Over time, these advantageous traits become more common in the population, leading to gradual changes – evolution.”

Ivy paused for emphasis before addressing the heart of her argument. “This process creates complex, well-adapted organisms, giving the illusion of intentional design. However, it’s a natural, undirected process, based on random mutations and the environmental pressure of survival. It shows how complexity and ‘design’ can arise naturally, without a guiding intelligence.”

She then turned her focus to the disanalogies with video games. “The key difference between the evolution of life and the virtual worlds of video games lies in intentionality. Game worlds are products of deliberate planning and design by developers. They have a specific end goal or experience in mind. In contrast, evolution has no foresight or end goal. It’s a blind process, driven by random genetic changes and environmental pressures, not by a conscious plan or purpose.”

“The intricacies of life, therefore, are not akin to the crafted levels of a video game but are the results of countless generations of survival-driven adaptations. This perspective challenges the notion of a designer, suggesting instead that what we perceive as ‘design’ in nature is the outcome of a natural, unguided process of evolution,” Ivy concluded, her argument a testament to the explanatory power of evolutionary theory in accounting for the complexities of life without invoking a designer.

A Theist Response to the Objections

Orion Quest, absorbing the critiques from Harper and Ivy, prepared to respond with renewed vigor, weaving his love for video games into the fabric of his counterarguments.

“Harper, your point about the nature of the designer being different from a traditional God is well-taken,” Orion began, addressing Hume’s critique as presented by Harper. “In the world of video games, yes, developers are fallible and work in teams, but this doesn’t diminish the fact that they create intricate, purposeful worlds. Perhaps our understanding of the divine should evolve, much like how game development has evolved. Maybe the designer of the universe is unlike the traditional view of God, but still possesses a level of creativity and intelligence far beyond our comprehension. In video games, different genres and narratives don’t imply multiple creators but show the versatility of a developer. Similarly, the diversity in the universe could reflect the multifaceted nature of a single, yet complex, designer.”

Turning to Ivy’s points on evolution, Orion continued, “Ivy, the process of evolution through natural selection is indeed a powerful force, but it doesn’t necessarily negate the possibility of a designer. Consider a sandbox game like ‘Minecraft’, where the environment allows for a range of possibilities and the players shape their world through their actions. The game provides the framework and the rules, but the players’ choices drive the evolution of their world. In this way, natural selection could be a mechanism set in motion by a designer, allowing for the unfolding of life within a set framework, rather than being purely random or undirected.”

“Moreover,” Orion added, “the initial conditions necessary for life and the precise tuning of the laws of physics remain unexplained by evolution. Just like a game needs to be programmed with the right parameters for a balanced and functional gameplay experience, the universe might have been ‘programmed’ with the right conditions for life to evolve. Evolution explains the diversity of life, but not the origin of life itself or the fine-tuning of the universe’s laws, which still suggest a designer’s hand.”

Orion’s defense was a blend of acknowledgment and adaptation, using video game metaphors to illustrate how the critiques might be integrated into a broader understanding of a designer’s possible nature and methods. His argument sought not to refute the critiques outright but to offer a nuanced perspective that bridged the gap between theism and the observations of the natural world.

Discussion Questions: The Argument From Design

- Do you find Orion’s analogy between video games and the universe to be a convincing argument for the existence of a designer? Why or why not?

- How does Hume’s objection about the nature of the designer impact the Argument from Design? Is it possible to separate the argument from the specific characteristics we attribute to the designer?

- Does Ivy’s explanation of evolution through natural selection adequately refute the Argument from Design? Explain your answer.

- How well does Orion’s response address the critiques presented by Harper and Ivy? Did his use of video game metaphors strengthen his counter-arguments?

- Evaluate the Argument from Design as an example of inductive reasoning. What are its strengths and weaknesses?

- Do you find the Argument from Design persuasive? Why or why not?

The Problem of Evil

Top of FormIvy Pathogen, drawing from her deep understanding of biology and medicine, shifted the conversation to introduce the problem of evil, a classic challenge to theistic arguments. Her approach, grounded in her scientific background, lent a unique perspective to this philosophical issue.

“Let’s consider the problem of evil from a biological standpoint,” Ivy began, her tone reflecting both empathy and analytical clarity. “The problem of evil, especially in its relation to the existence of an omnipotent and benevolent designer, can be articulated in the following standard form:

- If an all-powerful and all-good designer exists, then unnecessary suffering should not exist.

- However, in the world of biology and medicine, we observe immense and seemingly unnecessary suffering.

- Therefore, the existence of such a designer is unlikely.

“Let’s consider some of the most troubling forms of suffering, those involving children and animals, to illustrate the severity of this problem,” she began, her voice tinged with a mix of professional detachment and underlying compassion.

- “There are numerous diseases that primarily or exclusively affect children, causing immense suffering. For instance, pediatric cancers like neuroblastoma, a cancer that almost exclusively affects young children, often lead to painful treatments and, in many cases, premature death. The existence of such diseases raises questions about the presence of a compassionate designer who allows such suffering in the most vulnerable.”

- “Consider also congenital anomalies, such as congenital heart defects or spina bifida. These conditions, present from birth, can lead to lifelong suffering, severe physical limitations, and in many cases, early mortality. These are not the results of lifestyle choices or environmental factors, but are inherent in the biological makeup of these children.”

- “Moving beyond human life, the animal kingdom is rife with suffering that is hard to justify if we presume a benevolent designer. Predation, disease, starvation, and harsh environmental conditions lead to a brutal existence for many animals. This suffering is intrinsic to the natural world, not caused by human intervention.”

- “Genetic diseases like Tay-Sachs disease, which leads to the degeneration of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord, are particularly harrowing. Children with this condition suffer a progressive deterioration of their physical and mental capabilities, leading to an early death, usually by the age of four.”

- “Diseases like malaria, which disproportionately affect children in certain parts of the world, cause immense suffering and death. Similarly, animals suffer from a variety of diseases, often without the possibility of relief or treatment.”

Ivy concluded her exposition with a somber note, “These examples, drawn from the realities of biology and medicine, highlight the scale and depth of suffering experienced by children and animals. They pose a profound challenge to the idea of a benevolent and omnipotent designer, as it is difficult to reconcile such suffering with the attributes traditionally ascribed to a divine being.”

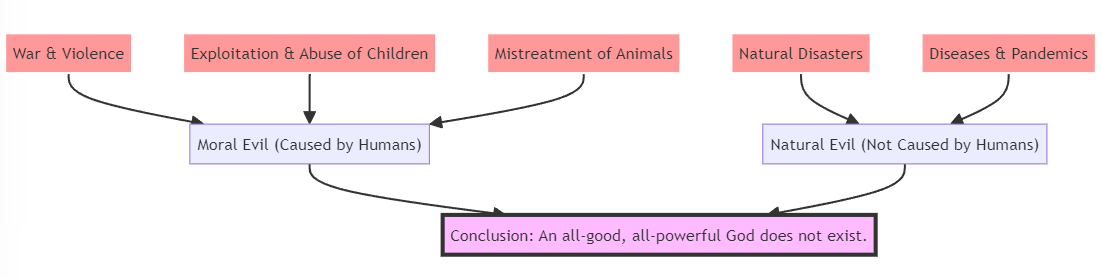

Graphic: The Problem of Evil

The Free Will Defense

Orion Quest, absorbing the gravity of Ivy’s points, responded with the free will defense, aiming to reconcile the existence of evil with the concept of a benevolent and omnipotent designer.

“First, it’s crucial to distinguish between natural evil and human evil,” Orion began. “Natural evil includes things like diseases and natural disasters, which Ivy described, while moral evil encompasses actions like murder, theft, or cruelty. The free will defense primarily addresses human evil, but I’ll attempt to extend it to natural evil as well.”

“Concerning moral evil,” Orion continued, “the argument goes like this: A key component of a meaningful human existence is free will. For our choices to be truly free, the possibility of choosing evil must exist. Therefore, the presence of moral evil can be seen as a byproduct of the gift of free will. Just as in video games, where players have the freedom to make choices that affect the game’s outcome, in life, our free choices shape our experiences and moral realities.”

“Applying this to natural evil is more complex,” Orion acknowledged. “One could argue that natural evil, like diseases or natural disasters, serves as a backdrop against which moral and spiritual growth can occur. In a video game, challenges and obstacles are essential for gameplay depth and player development. Similarly, natural evils could be seen as challenges in the ‘game’ of life, providing opportunities for humans to develop virtues like compassion, resilience, and cooperation.”

“Moreover, some argue that natural laws must operate consistently to allow for a stable, understandable universe. Just like the rules in a game world must be consistent for the game to function, the laws of nature must be uniform. Unfortunately, these same laws that allow for beauty and life also inadvertently lead to natural disasters and diseases.”

“In summary,” Orion concluded, “the free will defense suggests that moral evil is a consequence of our freedom to choose, and natural evil, while more challenging to explain, can be seen as an integral part of a world that allows for moral and spiritual growth, as well as the consistent operation of natural laws. This perspective attempts to reconcile the existence of both forms of evil with the concept of a benevolent and omnipotent designer.”

Evil in Other Religions

“You make an interesting case, Orion,” Harper began, her tone reflective and inclusive. “However, it’s important to remember that not all world religions are theistic in the way that the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) are. Many religions either do not posit an all-powerful, all-good deity or conceive of the divine in a markedly different way. This diversity in religious thought offers alternative approaches to the problem of evil.”

“Consider, for instance, Buddhism,” Harper continued. “Buddhism does not focus on a creator god but rather on the nature of human suffering and its cessation. The core teachings of Buddhism revolve around the Four Noble Truths, which diagnose the problem of suffering and prescribe a path to liberation from it. In this framework, suffering is a fundamental part of the human condition, arising from attachment and ignorance. The goal is not to question why a benevolent deity would allow suffering but to understand and overcome the causes of suffering through spiritual practice.”

“Similarly, in some forms of Hinduism, the concept of an all-powerful, benevolent deity is not central. Instead, ideas like karma and dharma play a significant role. Karma, the law of cause and effect, posits that actions in this life or past lives lead to certain consequences, including suffering. This perspective shifts the focus from a divine creator allowing evil to a moral framework where actions have natural repercussions.”

“And there are non-theistic religious traditions, like certain strains of Daoism and Confucianism, where the focus is on harmony with the Tao or ethical living, respectively, rather than on a personal, benevolent deity. The problem of evil, as framed in Abrahamic religions, does not arise in the same way in these contexts.”

Harper concluded, “These examples show that the problem of evil is not universal across all religions. It is more specific to theistic traditions that posit an all-powerful, all-good deity. Other religious traditions either bypass the problem altogether or approach it from a completely different angle, providing a rich tapestry of responses to the presence of suffering and evil in the world.”

Discussion Questions: The Problem of Evil

- How convincing is Ivy’s presentation of the problem of evil from a biological standpoint? Do you find the examples of suffering she presented compelling? Why or why not?

- Do you agree with Orion’s distinction between natural evil and human evil? Does this distinction affect the strength of the free will defense? Explain your answer.

- How does Harper’s discussion of non-theistic and polytheistic religions impact the relevance of the problem of evil? Does it weaken or strengthen the argument against the existence of a benevolent and omnipotent deity?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the Problem of Evil as an inductive argument? How does it compare to other arguments for and against the existence of God?

- How would you respond to someone who argues that suffering is essential for human growth and development? Do you agree that this justifies the existence of suffering?

- Is it possible to reconcile the existence of suffering with the existence of a benevolent God? If so, how?

Religion, Society, and the Individual

Harper Chronicle, framing her perspective within the context of her agnostic stance, began to expound on the sociological dimensions of religion with a thoughtful and academic approach.

“As an agnostic,” Harper stated, “I find the ‘truth’ of religious claims less compelling than understanding the roles and functions of religion in society. This viewpoint allows us to appreciate the sociological impact of religion, transcending its metaphysical assertions. Let’s delve into some major sociological accounts of religion, each illuminated by historical examples.”

Marxist Perspective: Religion as the ‘Opium of the People’.

“Karl Marx‘s perspective on religion is critically analytical. He saw religion as an instrument used by ruling classes to control the oppressed. This is vividly illustrated in the medieval period, where the Church played a central role in sustaining the feudal system. The Church offered comfort to those suffering under feudalism by advocating for a rewarding afterlife. This notion of heavenly rewards provided solace, making the masses more accepting of their hardships. It functioned as a psychological salve, diverting attention from the pressing injustices of their earthly existence. Marx’s critique is rooted in the idea that religion, rather than being an emancipatory force, often acts as a means of social control, pacifying populations under the guise of spiritual fulfillment.

To give a more contemporary example of Marx’s theory, we can look at the role of evangelical Christianity in American politics. Some politicians and religious leaders have used evangelical rhetoric to garner support for policies that arguably benefit the wealthy at the expense of the working class, such as cutting social welfare programs and reducing taxes on the rich. By framing these policies in religious terms and emphasizing issues like abortion and same-sex marriage, they can distract from economic inequalities and make lower-income voters more accepting of their disadvantaged position.

Another example is the rise of prosperity gospel megachurches, which preach that faith and donations to the church will be rewarded with material wealth and success. This message can make congregants more complacent with systemic injustices, believing that their hardships are a test of faith rather than the result of societal inequities.

We can also see elements of Marx’s critique in the way some authoritarian regimes have co-opted religion to solidify their power. For instance, in the early days of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the government used Shia Islam to legitimize its rule and quell dissent, framing opposition as being against God’s will.

Durkheimian Perspective: Social Cohesion and Collective Conscience

“In contrast, Émile Durkheim’s approach underscores religion’s positive, cohesive aspects. Durkheim posited that religion is a fundamental component for the cohesion of societies. It fosters what he called a ‘collective conscience,’ knitting individuals together with shared moral and ethical values. An exemplary historical instance of this is the ancient Egyptian religion. Far from being merely a set of spiritual beliefs, Egyptian religion was integral to their entire social and political structure. The divine status ascribed to the pharaoh was not just a religious belief but a unifying political force. Religious rituals and practices reinforce social norms and values, which are crucial in maintaining social order and cohesion. Durkheim’s view highlights the functional aspects of religion in society, emphasizing its role in maintaining social stability and unity.

Durkheim’s theory remains highly relevant today. A modern example that illustrates his ideas is the role of religion in many immigrant communities. For instance, in the United States, churches, mosques, and temples often serve as crucial hubs for immigrant groups, providing not just a place of worship but also a space for cultural events, language classes, and mutual aid. Participating in religious rituals and holidays together helps to maintain a sense of shared identity and strengthens social bonds.

We can also see Durkheim’s concepts at work in the way that religious institutions mobilize around social and political causes. Many faith-based organizations are at the forefront of movements for racial justice, immigrant rights, environmentalism, and more. By framing these issues in moral and spiritual terms, they help to build solidarity and a sense of shared purpose among their members.

Even in more secular societies, we can find analogs to the cohesive function of religion that Durkheim described. For example, in many European countries, sports fandom has taken on a quasi-religious character, with team allegiances and rituals serving to bind people together and provide a sense of collective identity. “

Weberian Perspective: Religion as a Catalyst for Social Change

“Max Weber’s analysis offers a distinct lens through which to view religion. In his seminal work, ‘The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,’ Weber explores how religious beliefs, specifically Protestantism, can be powerful agents of economic and social change. He argued that the Protestant ethic, with its emphasis on hard work, discipline, and frugality, significantly contributed to the development of capitalism in Western Europe. Unlike Marx’s view of religion as a tool for maintaining the status quo, Weber saw religious beliefs as dynamic forces capable of driving societal transformation. Protestantism, in this context, wasn’t just mirroring the existing social order but actively shaping a new economic ethos. This perspective reveals religion as an influential factor in the evolution of societal structures, challenging existing paradigms and fostering new ways of social and economic interaction.

A contemporary example of Weber’s theory can be seen in the rise of liberation theology in Latin America. This movement, which emerged in the 1960s, interprets Christian teachings through the lens of social justice and advocates for the empowerment of the poor and oppressed. Priests and lay activists inspired by liberation theology have been at the forefront of struggles for land reform, labor rights, and democracy, challenging the entrenched power of political and economic elites.

Another instance of religion driving social change is the role of Buddhist monks in the Tibetan independence movement. Their nonviolent resistance to Chinese rule, rooted in Buddhist principles of compassion and self-sacrifice, has drawn international attention to their cause and sparked a global human rights campaign.

In the United States, the Black Church has long been a catalyst for social and political transformation, from the abolitionist movement to the Civil Rights era. Today, many Black churches continue this tradition by engaging in community organizing, advocating for criminal justice reform, and providing social services to underserved neighborhoods.”

Functionalist Perspective: Religion as Fulfilling Social Needs

“Building on Durkheim’s foundational ideas, functionalist theories view religion as fulfilling essential social needs. This perspective posits that religion is crucial in creating a sense of belonging, providing moral guidelines, and offering comfort during times of distress. A historical example that illustrates this role is the spread of Christianity in the Roman Empire. During a period characterized by political instability and social upheaval, Christianity provided a unifying sense of community and hope. It fulfilled individuals’ psychological and social needs, offering a moral compass and a sense of belonging in a turbulent world. Functionalist theories underscore the role of religion in meeting the various needs of individuals and society, reinforcing social cohesion and offering psychological and emotional support.

The functionalist perspective remains relevant in understanding the role of religion in contemporary societies. For example, in times of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, many people have turned to their faith communities for support, finding solace in prayer, ritual, and virtual gatherings. Religious institutions have also stepped up to provide essential services, such as running food banks, offering mental health counseling, and serving as vaccination sites.

Another modern example is the way that religion can provide a sense of identity and belonging for marginalized groups. For instance, LGBTQ+ individuals who may feel excluded from mainstream religious traditions have created their own affirming congregations and spiritual practices. Similarly, Indigenous communities have used the revitalization of traditional spiritual practices as a means of cultural preservation and resistance to assimilation.

Even in highly secularized countries like Japan, religion continues to fulfill important social functions. Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples are deeply intertwined with community life, hosting festivals, marking rites of passage, and serving as spaces for art, culture, and connection to nature.”

Symbolic Interactionism: The Role of Religious Symbols in Social Life

“Symbolic interactionism, another important sociological perspective, emphasizes the role of religious symbols in shaping individual identities and social interactions. This approach focuses on the meanings individuals ascribe to religious symbols and how these symbols influence their perceptions and interactions. A poignant example can be found in the American Civil Rights Movement. Religious symbols and narratives provided a powerful moral framework and imagery that united people across diverse backgrounds. The movement’s leaders, many of whom were religious figures, used religious language and symbols to advocate for equality and justice, effectively mobilizing masses and inspiring change. This perspective highlights the profound impact of religious symbols in constructing social realities, influencing individual behaviors, and fostering collective action.

The symbolic interactionist perspective can help us understand the power of religious symbols in shaping contemporary social movements. For instance, during the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, protesters often gathered in Tahrir Square on Fridays after Muslim prayers, blending religious symbolism with political activism. The sight of Christians forming a protective circle around Muslims during prayer became an iconic image of interfaith solidarity against oppression.

In the United States, the hijab has become a potent symbol in debates over Islam, immigration, and women’s rights. For some Muslim women, wearing the hijab is a way of asserting their religious identity and resisting Islamophobia. However, others see it as a symbol of patriarchal oppression. These competing meanings reflect the complex ways that religious symbols intersect with larger social and political discourses.

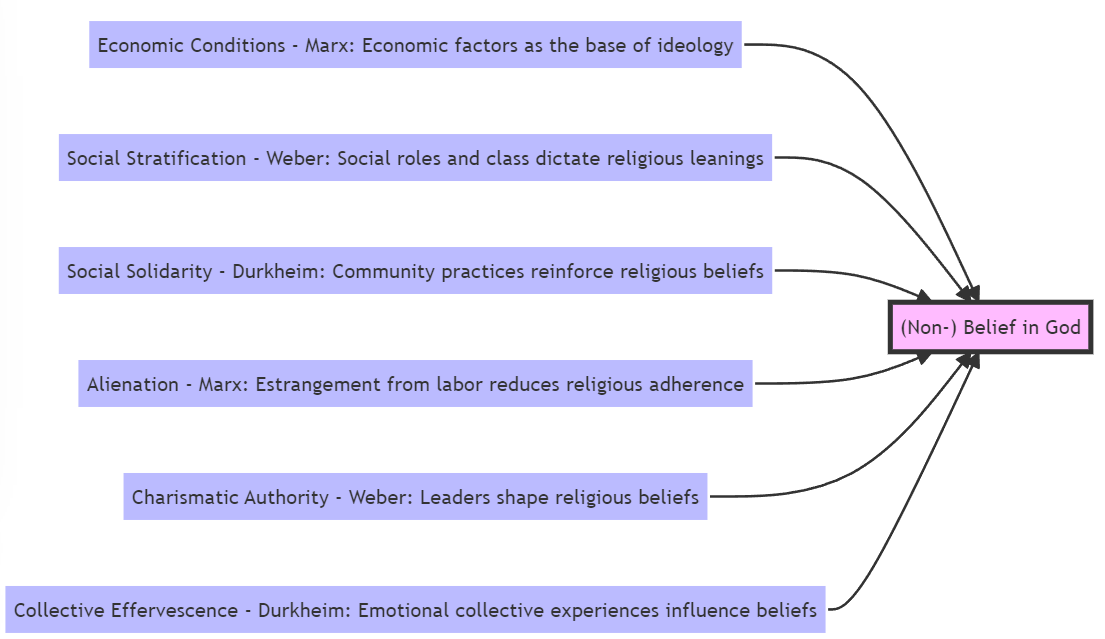

Graphics: Social Influences on (Non-)Belief

Is Religion a Useful Fiction?

“I see religion in a light similar to what we might call a ‘useful fiction,'” Harper stated. “This doesn’t diminish its value or significance; rather, it acknowledges its role in providing meaning, structure, and cohesion in human life. To make this concept more relatable, let’s draw analogies from Orion’s world of video games and Ivy’s domain of scientific theories.”

“To Orion, consider how video games, while fictional, offer valuable experiences. They create immersive worlds, tell compelling stories, and often present moral and ethical dilemmas for players to navigate. These fictional scenarios encourage creativity, problem-solving, and empathy. Similarly, religion, while it may be seen as fictional from a literal standpoint, provides moral frameworks, communal narratives, and existential meaning to its adherents. Like a well-crafted game, it can guide behavior, foster community, and offer a sense of purpose and belonging.”

“Turning to Ivy’s perspective, think about scientific theories that were once accepted but are now considered ‘wrong’ in a literal sense. For example, the geocentric model of the universe, or the phlogiston theory of combustion. While these theories are not scientifically accurate by today’s standards, they were useful in their time. They provided frameworks for understanding and exploring the world, leading to further scientific inquiry and advancement. In this sense, religion can be analogous to these early scientific theories. It may not be literally true in every aspect, but it offers a useful framework for understanding human existence, moral values, and social cohesion.”

“Thus, interpreting religion as a ‘useful fiction’ allows us to appreciate its role in human culture and history. It acknowledges the power of narrative and metaphor in shaping our understanding of the world and ourselves, regardless of its empirical veracity. This perspective doesn’t necessarily devalue religious belief but recognizes its functional and symbolic significance in human life, much like the significance of a compelling video game or an early scientific theory.”

Objections to Religious Fictionalism

Orion Quest, reflecting on Harper’s view of religion as a ‘useful fiction’, prepared his response, drawing from his deep engagement with the world of video games.

“Harper, I see the merit in your analogy, especially from my perspective of video games as meaningful, yet fictional, experiences,” Orion began. “However, there’s a fundamental difference between engaging with a video game and practicing a religion. When I play a game, I’m fully aware that it’s a constructed reality, a temporary escape. The emotions and lessons may be real, but there’s always an underlying acknowledgment of its fictional nature. With religion, however, for many believers, it’s not just a useful narrative or a metaphorical framework; it’s a literal truth that guides their entire life and worldview. To equate the two might oversimplify the depth of commitment and belief involved in religious practice.”

“Furthermore,” Orion continued, “while video games can offer moral and ethical dilemmas, they do so in a controlled environment where the consequences are limited to the virtual world. Religion, on the other hand, influences real-world decisions and actions, often with significant consequences. The idea of it being a ‘useful fiction’ might undermine the very real impact it has on societal norms, laws, and personal choices.”

Ivy Pathogen, nodding in agreement with Orion, added her perspective from the scientific realm.

“Harper, I appreciate your point about early scientific theories being ‘useful’ despite being literally wrong,” Ivy said. “However, the key difference with science is its self-correcting nature. Scientific theories are constantly tested, challenged, and revised in light of new evidence. They’re tools for understanding the world, always subject to change and improvement. Religion, in contrast, often relies on fixed doctrines and absolute truths that are not open to revision or questioning in the same way. While it might serve useful social functions, equating it with scientific theories overlooks the critical aspect of adaptability and evolution in scientific understanding.”

“Additionally,” Ivy continued, “while early scientific theories were stepping stones to better understanding, they were replaced as soon as better explanations were found. If we view religion as a similar stepping stone, it implies that it should also be replaced when better explanations for moral and existential questions are found. This perspective could challenge the enduring relevance and authority of religious teachings and institutions.”

Wrapping Up

As the conversation drew to a close, the three friends, Orion Quest, Ivy Pathogen, and Harper Chronicle, reflected on the rich tapestry of ideas they had explored. Despite their differing viewpoints, they found common ground and areas of curiosity that further fueled their desire for understanding.

Orion, with a thoughtful look, initiated the wrap-up. “This discussion has been enlightening. Despite our differing perspectives, we all seem to agree on religion’s profound impact on society and individuals. Whether seen as a literal truth, a useful fiction, or a sociological phenomenon, its influence is undeniable.”

Ivy said, “Yes, and I think we also agree on the value of questioning and exploring these beliefs. Whether through the lens of science, sociology, or personal belief, understanding the role and function of religion is crucial. Where we differ, perhaps, is in our views on the literal truth of religious claims and how we reconcile or challenge these with scientific understanding and personal beliefs.”

Harper, nodding in agreement, added, “It’s fascinating how our backgrounds influence our perspectives. Orion, through the lens of video games and digital worlds, Ivy, through the rigor of scientific inquiry, and myself, from the standpoint of historical and sociological contexts. It’s clear that our approaches to religion and its implications vary, but our mutual respect and curiosity for each other’s views have enriched this conversation.”

“There’s so much more to learn and understand,” Orion said, a sense of curiosity in his voice. “The intersections between religion, science, technology, and society are vast and complex. I’m eager to explore how my understanding of virtual worlds and programming might offer further insights into these topics.”

“And I’m interested in how evolving scientific discoveries continue to shape our understanding of the world and, in turn, how they intersect with religious beliefs,” Ivy added, her scientific mindset shining through.

Harper concluded, “As for me, I’m curious about how historical and sociological perspectives on religion will evolve as society changes. The impact of religion on culture, ethics, and social norms is an ongoing narrative, one that I’m eager to continue exploring.”

With a shared sense of camaraderie and intellectual curiosity, the friends agreed to continue their discussions, each bringing their unique perspectives to the ever-evolving dialogue about religion and its role in the world.

Discussion Questions: Religion and Society

- Do you agree with Harper’s characterization of religion as a “useful fiction”? Why or why not?

- How do the different sociological perspectives presented in the text (Marxist, Durkheimian, Weberian, Functionalist, and Symbolic Interactionism) contribute to our understanding of the role of religion in society?

- Evaluate Orion’s and Ivy’s objections to Harper’s view of religion as a “useful fiction”. Do their arguments hold merit?

- How does the text address the relationship between religion and science? Do you see any potential for reconciliation between these two seemingly disparate domains?

- What are some of the ethical implications of the different perspectives on religion presented in the text?

- Do you believe that religion has a positive or negative impact on society overall? Why or why not?

Minds that Mattered: Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, philosopher, and theologian. Born in Clermont-Ferrand, France, Pascal was a child prodigy who made significant contributions to mathematics and science at a young age. He is best known for his work in probability theory, his contributions to the development of the modern theory of decision-making, and his philosophical and theological writings.

Pascal’s early work focused on mathematics and physics. He made important contributions to the study of fluid mechanics and pressure, inventing the hydraulic press and the syringe. He also developed Pascal’s theorem in projective geometry and made significant advances in the study of infinitesimals.

Later in life, Pascal turned his attention to philosophy and theology. His most famous work in this area is the “Pensées” (Thoughts), a collection of fragments and notes on religious and philosophical topics that he intended to develop into a comprehensive defense of Christianity. Although he died before completing this work, the “Pensées” remains an influential and widely read text in the history of philosophy and theology.

Key Ideas

ascal, along with his contemporary Pierre de Fermat, is credited with laying the foundations of modern probability theory. In their correspondence, Pascal and Fermat discussed various problems related to games of chance, including how to divide the stakes in an unfinished game and how to calculate the likelihood of certain outcomes. Through these discussions, they developed the basic concepts of probability, such as expected value and the addition and multiplication rules for probabilities. Pascal’s work on probability theory has important implications for our understanding of the fallacy of hasty generalization. By providing a mathematical framework for quantifying the likelihood of different outcomes based on available evidence, probability theory helps us to avoid making overly broad or unwarranted generalizations based on limited data. Instead, it encourages us to consider the strength and representativeness of our evidence when making inductive inferences.

Another key contribution of Pascal’s work on probability was the development of the concept of expected utility. In his famous “wager” argument (discussed below), Pascal introduced the idea that the rational choice in a decision situation should be based on the expected value of each option, taking into account both the likelihood of different outcomes and the utility or value associated with each outcome. This idea forms the basis of modern decision theory, which provides a framework for making rational choices under conditions of uncertainty. By considering the probabilities and utilities associated with different options, decision theory helps us to make more informed and justifiable choices in complex situations. Pascal’s work on expected utility thus has important implications for fields ranging from economics and psychology to philosophy and artificial intelligence.

Perhaps Pascal’s most famous philosophical contribution is his “Pascal’s wager” argument, which he presents in the “Pensées” as a pragmatic justification for belief in God. The argument runs as follows: If God exists, the rewards of believing in Him (eternal happiness) are infinitely great, while the costs of not believing (eternal damnation) are infinitely terrible. If God does not exist, the costs and benefits of believing or not believing are comparatively trivial. Therefore, the rational choice is to believe in God, since the expected utility of belief is infinitely greater than that of non-belief. While the validity and soundness of Pascal’s wager have been widely debated, the argument highlights important questions about the role of reason in religious belief and the limits of rational decision-making in matters of faith. Pascal himself acknowledged that the wager was not intended to provide a conclusive proof of God’s existence, but rather to show that belief in God is rationally justifiable even in the absence of such proof.

Influence

ascal’s work has had a profound and lasting impact on a wide range of fields, from mathematics and science to philosophy and theology. His contributions to probability theory and decision theory have become foundational concepts in these areas, shaping the development of modern statistics, economics, and psychology.

In mathematics, Pascal’s work on probability, combinatorics, and infinitesimals helped to lay the groundwork for the development of calculus and modern analysis. His famous triangle, which provides a simple way to calculate binomial coefficients, is still widely used today in fields ranging from algebra to combinatorics.

In science, Pascal’s experiments on fluid mechanics and pressure helped to establish the basic principles of hydrostatics and hydrodynamics. His invention of the hydraulic press and the syringe also had important practical applications in engineering and medicine.

In philosophy and theology, Pascal’s “Pensées” remains a classic text, admired for its depth, insight, and eloquence. His ideas on the limits of reason, the importance of intuition and personal experience in matters of faith, and the paradoxical nature of the human condition have influenced generations of thinkers, from existentialists like Kierkegaard and Camus to religious philosophers like William James and Alvin Plantinga.

Today, Pascal’s legacy continues to inspire and inform work in a variety of fields. His emphasis on the importance of rigorous, logical thinking, combined with his recognition of the limits of reason and the value of other forms of knowledge, serves as a model for interdisciplinary research and scholarship. At the same time, his personal struggles with faith, doubt, and the search for meaning continue to resonate with readers seeking to navigate the complexities of the modern world.

Discussion Questions

- How does Pascal’s work on probability theory help us to avoid the fallacy of hasty generalization? What are some examples of situations in which a probabilistic approach can lead to more accurate and justified inductive inferences?

- In what ways has Pascal’s concept of expected utility influenced modern decision theory? How can the principles of decision theory be applied to real-world situations involving uncertainty and complex trade-offs?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of Pascal’s wager as an argument for belief in God? To what extent does the wager rely on assumptions about the nature of God, the afterlife, and the costs and benefits of belief?

- How does Pascal’s view of the relationship between reason and faith compare to other perspectives on this issue, such as those of rationalists like Descartes or empiricists like Hume? What are the implications of Pascal’s view for the role of reason in religious belief and practice?

- In what ways does Pascal’s work continue to be relevant to contemporary research and scholarship in fields such as mathematics, science, philosophy, and theology? What can we learn from his approach to interdisciplinary thinking and his recognition of the limits of reason?

Glossary

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Abrahamic Religions |

Monotheistic faiths that trace their origin to the figure of Abraham, primarily including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. These religions share commonalities in theology, history, and ethical teachings. |

|

Agnostic |

A position regarding the existence of God or gods, where an individual neither believes nor disbelieves in a deity. Agnosticism is based on the view that the existence of the divine is unknown or unknowable. |

|

Argument from Design |

A teleological argument for the existence of God, suggesting that the complexity and functionality of the universe imply a deliberate designer, much like the complexity of human-made objects implies a human creator. |

|

Evolution via Natural Selection |

A scientific theory proposed by Charles Darwin, stating that species evolve over time through a process of natural selection, where genetic variations that enhance survival are passed on to future generations, leading to gradual changes in the species. |

|

Expected Value |

The average outcome of a random variable, calculated by multiplying each possible outcome by its probability and summing the results. |

|

Four Noble Truths |

The central teachings of Buddhism, outlining the nature of suffering, its causes, the possibility of its cessation, and the path leading to the cessation of suffering. These truths form the core of Buddhist philosophy and practice. |

|

Free Will Defense |

A theodicy arguing that the existence of evil is a necessary consequence of free will. It posits that a world with free will and resulting evil is more valuable than a world with neither, and that free will is necessary for genuine moral choices. |

|

Functionalist theories of religion |

Sociological theories that view religion as serving vital social functions. These include creating social cohesion, providing moral guidelines, and offering psychological comfort, thus contributing to the stability and functioning of society. |

|

Hume’s Critique of the Design Argument |

David Hume’s counterargument suggesting that the world’s imperfections and evils are inconsistent with a perfect creator. He argued that the complexity of the world does not necessarily point to a single, benevolent designer, and could be the result of multiple creators or natural processes. |

|

Karma (Hinduism) |

A fundamental concept in Hindu philosophy, referring to the law of cause and effect governing actions and their consequences. It posits that every action has a corresponding reaction, affecting an individual’s future life or lives in terms of rebirth and the cycle of samsara. |

|

Marxist account of religion |

An analysis of religion from a Marxist perspective, viewing it as a tool used by ruling classes to control and pacify the oppressed. It suggests that religion serves to justify the status quo and distract people from economic and social inequalities. |

|

Moral Evil |

Evil and suffering that result from human actions and choices, such as violence, cruelty, and injustice. It is often used in the context of the problem of evil to distinguish between suffering caused by human free will and that caused by natural processes. |

|

Natural Evil |

Suffering arising from natural causes (like earthquakes, diseases, and natural disasters) rather than human actions. This form of evil challenges the existence of an all-good, all-powerful deity due to its indiscriminate nature. |

|

Pascal’s Wager |

An argument for belief in God based on the idea that the expected utility of belief is infinitely greater than that of non-belief, regardless of the actual existence of God. |

|

Probability |

The likelihood or chance that a particular event will occur, expressed as a number between 0 and 1. |

|

Problem of Evil |

A philosophical challenge to theism, questioning how an all-powerful, all-good deity can coexist with the existence of evil and suffering in the world. It argues that the presence of unnecessary suffering is inconsistent with the existence of such a deity. |

|

Symbolic interactionism |

A sociological perspective focusing on the role of symbols and language in human interactions. It examines how individuals interpret and give meaning to symbols, including religious symbols, and how these interpretations influence social behavior and identity. |

|

Tao |

A central concept in Taoism, often translated as ‘the Way.’ It refers to the essential, unnameable process of the universe, emphasizing harmony with the natural order and the interconnectedness of all things. |

|

Theism |

The belief in the existence of a god or gods, particularly a single, personal deity who is involved in the world and in the lives of its creatures. This stands in contrast to deism, atheism, and agnosticism. |

|

Weberian account of religion |

Max Weber’s sociological analysis of religion, emphasizing its role as a driver of social change. Weber explored how religious ideas, particularly Protestant ethics, contributed to the development of capitalism and influenced various aspects of society. |

|

|

|

References

Aquinas, Thomas. 2006. Summa Theologica. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/17611/pg17611-images.html.

Aristotle. 2008. Metaphysics. Internet Classics Archive. https://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/metaphysics.html.

Descartes, René. 2008. Meditations on First Philosophy. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/23306/23306-h/23306-h.htm.

Durkheim, Émile. 2012. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/41360/pg41360-images.html.

Hume, David. 2009. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4583/4583-h/4583-h.htm.

James, William. 2014. The Varieties of Religious Experience. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/621/pg621-images.html.

Kant, Immanuel. 2003. Critique of Pure Reason. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4280/4280-h/4280-h.htm.

Marx, Karl. 2010. Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. Oxford University Press. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_Critique_of_Hegels_Philosophy_of_Right.pdf.

Meister, Chad. “Philosophy of Religion.” In Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/religion/.

Murray, Michael J., and Michael Rea. 2022. “Philosophy and Christian Theology.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2022. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/christiantheology-philosophy/.

Oppy, Graham. 2022. “Ontological Arguments.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2022. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/ontological-arguments/.

Pascal, Blaise. 2006. Pensées. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/18269/18269-h/18269-h.htm.

Paley, William. 2019. Natural Theology. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47314/47314-h/47314-h.htm.

Plantinga, Alvin, and Michael Tooley. 2008. Knowledge of God. Blackwell Publishing.

Swinburne, Richard. 2004. The Existence of God. Oxford University Press.

Taliaferro, Charles. 2023. “Philosophy of Religion.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Fall 2023. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/philosophy-religion/.

Tooley, Michael. 2021. “The Problem of Evil.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2021. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/evil/.

Weber, Max. 1905. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Marxists.org. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/weber/protestant-ethic/.