Cognitive Development in Middle Adulthood

What you’ll learn to do: describe cognitive and neurological changes during middle adulthood

While we sometimes associate aging with cognitive decline (often due to the the way it is portrayed in the media), aging does not necessarily mean a decrease in cognitive function. In fact, tacit knowledge, verbal memory, vocabulary, inductive reasoning, and other types of practical thought skills increase with age. We’ll learn about these advances as well as some neurological changes that happen in middle adulthood in the section that follows.

Learning Outcomes

- Outline cognitive gains/deficits typically associated with middle adulthood

- Explain changes in fluid and crystallized intelligence during adulthood

Cognition in Middle Adulthood

Intelligence is influenced by heredity, culture, social contexts, personal choices, and certainly age.

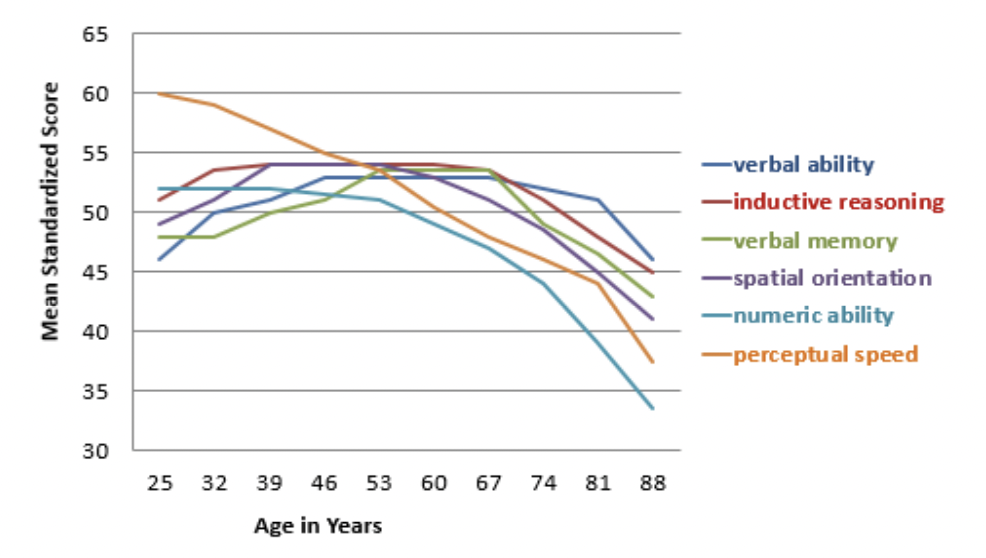

One of the most influential perspectives on cognition during middle adulthood has been that of the Seattle Longitudinal Study (SLS) of adult cognition, which began in 1956. Every seven years the current participants are evaluated, and new individuals are also added. Approximately 6000 people have participated thus far, and 26 people from the original group are still in the study today. Current results demonstrate that middle-aged adults perform better on four out of six cognitive tasks than those same individuals did when they were young adults. Verbal memory, spatial skills, inductive reasoning (generalizing from particular examples), and vocabulary increase with age until one’s 70s (Schaie, 2005; Willis & Shaie, 1999). However, numerical computation and perceptual speed decline in middle and late adulthood

Schaie & Willis (2010) summarized the general findings from this series of studies as follows: “We have generally shown that reliably replicable average age decrements in psychometric abilities do not occur prior to age 60, but that such reliable decrement can be found for all abilities by 74 years of age.” In short, decreases in cognitive abilities begin in the sixth decade and gain increasing significance from that point on. However, Singh-Maoux et al (2012) argue for small but significant cognitive declines beginning as early as age 45. There is some evidence that adults should be as aggressive in maintaining their cognitive health as they are their physical health during this time as the two are intimately related.

Seattle Longitudinal Study

A second source of longitudinal research data on this part of the lifespan has been the The Midlife in the United States Studies (MIDUS), which began in 1994. The MIDUS data supports the view that this period of life is something of a trade-off, with some cognitive and physical decreases of varying degrees. The cognitive mechanics of processing speed, often referred to as fluid intelligence, physiological lung capacity, and muscle mass, are in relative decline. However, knowledge, experience and the increased ability to regulate our emotions can compensate for these loses. Continuing cognitive focus and exercise can also reduce the extent and effects of cognitive decline.

Cognitive Aging

Researchers have identified areas of loss and gain in cognition in older age. Cognitive ability and intelligence are often measured using standardized tests and validated measures. The psychometric approach has identified two categories of intelligence that show different rates of change across the life span (Schaie & Willis, 1996). Fluid and crystallized intelligence were first identified by Cattell in 1971. Fluid intelligence refers to information processing abilities, such as logical reasoning, remembering lists, spatial ability, and reaction time. Crystallized intelligence encompasses abilities that draw upon experience and knowledge. Measures of crystallized intelligence include vocabulary tests, solving number problems, and understanding texts. There is a general acceptance that fluid intelligence decreases continually from the 20s, but that crystallized intelligence continues to accumulate. One might expect to complete the NY Times crossword more quickly at 48 than 22, but the capacity to deal with novel information declines.

With age, systematic declines are observed on cognitive tasks requiring self-initiated, effortful processing, without the aid of supportive memory cues (Park, 2000). Older adults tend to perform poorer than young adults on memory tasks that involve recall of information, where individuals must retrieve information they learned previously without the help of a list of possible choices. For example, older adults may have more difficulty recalling facts such as names or contextual details about where or when something happened (Craik, 2000). What might explain these deficits as we age?

As we age, working memory, or our ability to simultaneously store and use information, becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). The ability to process information quickly also decreases with age. This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences on many different cognitive tasks (Salthouse, 2004). Some researchers have argued that inhibitory functioning, or the ability to focus on certain information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information, declines with age and may explain age differences in performance on cognitive tasks (Hasher & Zacks, 1988).

Fewer age differences are observed when memory cues are available, such as for recognition memory tasks, or when individuals can draw upon acquired knowledge or experience. For example, older adults often perform as well if not better than young adults on tests of word knowledge or vocabulary. With age often comes expertise, and research has pointed to areas where aging experts perform as well or better than younger individuals. For example, older typists were found to compensate for age-related declines in speed by looking farther ahead at printed text (Salthouse, 1984). Compared to younger players, older chess experts are able to focus on a smaller set of possible moves, leading to greater cognitive efficiency (Charness, 1981). Accrued knowledge of everyday tasks, such as grocery prices, can help older adults to make better decisions than young adults (Tentori, Osheron, Hasher, & May, 2001).

We began with Schaie and Willis (2010) observing that no discernible general cognitive decline could be observed before 60, but other studies contradict this notion. How do we explain this contradiction? In a thought-provoking article, Ramscar et al (2014) argued that an emphasis on information processing speed ignored the effect of the process of learning/experience itself; that is, that such tests ignore the fact that more information to process leads to slower processing in both computers and humans. We are more complex cognitive systems at 55 than 25.

Watch It

This video highlights some of the cognitive changes during adulthood as well as the characteristics that either decline, improve, or remain stable.

Gaining Expertise

Expertise refers to specialized skills and knowledge that pertain to a particular topic or activity. In contrast, a novice is someone who has limited experiences with a particular task. Everyone develops some level of “selective” expertise in things that are personally meaningful to them, such as making bread, quilting, computer programming, or diagnosing illness. Expert thought is often characterized as intuitive, automatic, strategic, and flexible.

- Intuitive: Novices follow particular steps and rules when problem solving, whereas experts can call upon a vast amount of knowledge and past experience. As a result, their actions appear more intuitive than formulaic. Novice cooks may slavishly follow the recipe step by step, while chefs may glance at recipes for ideas and then follow their own procedure.

- Automatic: Complex thoughts and actions become more routine for experts. Their reactions appear instinctive over time, and this is because expertise allows us to process information faster and more effectively (Crawford & Channon, 2002).

- Strategic: Experts have more effective strategies than non-experts. For instance, while both skilled and novice doctors generate several hypotheses within minutes of an encounter with a patient, the more skilled clinicians’ conclusions are likely to be more accurate. In other words, they generate better hypotheses than the novice. This is because they are able to discount misleading symptoms and other distractors and hone in on the most likely problem the patient is experiencing (Norman, 2005). Consider how your note taking skills may have changed after being in school over a number of years. Chances are you do not write down everything the instructor says, but the more central ideas. You may have even come up with your own short forms for commonly mentioned words in a course, allowing you to take down notes faster and more efficiently than someone who may be a novice academic note taker.

- Flexible: Experts in all fields are more curious and creative; they enjoy a challenge and experiment with new ideas or procedures. The only way for experts to grow in their knowledge is to take on more challenging, rather than routine tasks.

Expertise takes time. It is a long-process resulting from experience and practice (Ericsson, Feltovich, & Prietula, 2006). Middle-aged adults, with their store of knowledge and experience, are likely to find that when faced with a problem they have likely faced something similar before. This allows them to ignore the irrelevant and focus on the important aspects of the issue. Expertise is one reason why many people often reach the top of their career in middle adulthood.

However, expertise cannot fully make-up for all losses in general cognitive functioning as we age. The superior performance of older adults in comparison to younger novices appears to be task specific (Charness & Krampe, 2006). As we age, we also need to be more deliberate in our practice of skills in order to maintain them. Charness and Krampe (2006) in their review of the literature on aging and expertise, also note that the rate of return for our effort diminishes as we age. In other words, increasing practice does not recoup the same advances in older adults as similar efforts do at younger ages.

Glossary

control beliefs: the belief that an individual can influence life outcomes, encompassing estimations of relevant external constraints and our own capabilities

crystallized intelligence: knowledge, skills, and experience acquired over a lifetime, accessible via memory and expressible in word/number form

fluid intelligence: the ability to recognize patterns and solve problems, irrespective of any past experience of the context in which these patterns or problems arise