7 Trademark and Patent Law

Agnes Gambill West

Constitutional and Statutory Law

Constitutional and Statutory Law

U.S. Const., Art. I, § 8, cl. 8. The Congress shall have Power * * * To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

Lanham (Trademark) Act, Pub. L. 79–489, 60 Stat. 427, July 5, 1946, codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1051 et seq.

Patent Act of 1952, Pub. L. 82–593, 66 Stat. 792, July 19, 1952, codified at 35 U.S.C. § 1 et seq.

Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), Pub. L. 112–29, 125 Stat. 284, September 16, 2011

Case Law

The Museum of Modern Art v. MOMACHA IP LLC and MOMACHA OP LLC, 339 F. Supp. 3d 361 (SDNY 2018)

OPINION & INJUNCTION

LOUIS L. STANTON, U.S.D.J.

Plaintiff The Museum of Modern Art (“Museum”) moves under Rule 65(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for an order preliminarily enjoining Defendants MOMACHA IP LLC and MOMACHA OP LLC (collectively “MOMACHA”) from using, displaying, or promoting the MOMA or MOMACHA marks, and the https://momacha.com/ domain name, during the pendency of this action. MOMACHA opposes the motion on the grounds that MoMA has not shown a likelihood of success on the merits of its claims or a likelihood of irreparable harm in the absence of an injunction, and that the balance of hardships tilts in MOMACHA’s favor. For the reasons that follow, the motion is granted.

BACKGROUND

The Museum of Modern Art (“Museum”) was founded in 1929. It is located in New York City. The Museum has an art collection of approximately 200,000 works of modern and contemporary art, including paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, photographs, media and performance art works, architecture, and films. It sustains a library, a conservation laboratory, and archives that are recognized as international centers of research. The Museum has published more than 2,500 titles, and participates in numerous book fairs each year, including the London Book Fair, Bologna Book Fair, and the Frankfurt Book Fair.

…

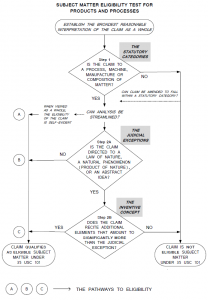

The Museum has been generally known by its acronym, MOMA, for nearly 50 years. That name appears on the Museum’s building, banners, signs, brochures, merchandise, promotional materials, and website. In the mid-1980s, the Museum transitioned its name and logo from “MOMA” to “MoMA,” with a lowercase “o” between the two capitalized “M”s. The Museum’s current logo is shown below:

![]()

The mark is used both horizontally and vertically, such as on the front of the Museum’s building, as shown below:

The logo uses a proprietary font called “MoMA Gothic,” which was developed exclusively for MoMA in 2003 based on the ITC Franklin Gothic font. Id. The logo has received significant press coverage, including in the New York Times.

The Museum has used the MoMA logo in virtually all of its communications with the public, press, artists, and sponsors, since 1967. … The Museum owns the registered trademark for “MOMA” for a variety of goods, such as stationery, arts and crafts, household items, games, artwork reproductions, books, clothing, and other merchandise. In addition, the trademark covers museum services, such as conducting exhibitions, workshops, and presentations. The Museum also owns registered trademarks for “MOMA DESIGN STORE,” “MOMAQNS,” “MOMA MODERN KIDS,” and “MOMA PS1”

MOMACHA operates an art gallery and café that was initially named “MoMaCha.” MoMaCha opened to the public in early April of 2018 in a storefront space at an art gallery called The Hole, which is located in the Lower East Side of New York City. The café is in close proximity to the MoMA Design Store in the SoHo neighborhood.

MOMACHA displays modern artwork that customers can buy. It also sells novelty art-related products such as blankets and towels. MOMACHA has filed trademark applications to register “MOMACHA” and “MOMA” for beverages and restaurant and café services. MOMACHA has a website https://momacha.com that promotes the café, and features photography and artwork.

MOMACHA’s original logo uses a font that is or greatly resembles ITC Franklin Gothic Heavy. The logo uses black-and-white coloring, with each of the three syllables in “MoMaCha” on a separate line and the first initial capitalized. MOMACHA also displays the mark vertically and on one line on its coffee cups.

On or about April 24, 2018, MOMACHA created a new logo, as shown below. The new logo is also in black and white, but uses a different font and capitalizes all of the letters in “MOMACHA.” MOMACHA has officially changed its logo to the new logo on its door, menus, cups, employees’ clothing, social media accounts, and receipts. MOMACHA has also changed its name from “MoMaCha” to “MOMACHA” on Yelp, Google Maps, its social media accounts, and its hashtag from “#MoMaCha” to “#MOMACHA”. MOMACHA now displays disclaimers on its door, its receipts, its website, its social media pages, and a sign inside the café stating that it does not have any affiliation with “the Museum of Modern Art or any Museum.”

After creating its new logo, MOMACHA has continued to use its old logo on social media and its coffee cups. MOMACHA intends to open two or three additional café locations in New York City this year with the same name.

…

Likelihood of Confusion

The parties dispute whether the Museum has shown a likelihood of consumer confusion between MoMA’s mark and MOMACHA’s mark.

…

Because MOMACHA continues to use its old logo, the court should consider MOMACHA’s old logo in addition to its new logo when assessing the likelihood of confusion between the two parties’ marks.

The factors ordinarily weighed in determining the likelihood of confusion are the familiar Polaroid factors, which include: 1) the strength of the plaintiff’s mark; 2) the similarity of plaintiff’s and defendant’s marks; 3) the competitive proximity of the products; 4) the likelihood that plaintiff will “bridge the gap” and offer a product like defendant’s; 5) actual confusion between products; 6) good faith on the defendant’s part; 7) the quality of defendant’s product; and 8) the sophistication of buyers. Gruner + Jahr USA Publ’g, 991 F.2d at 1077, citing Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Elecs. Corp., 287 F.2d 492, 495 (2d Cir. 1961), “[E]ach factor must be evaluated in the context of how it bears on the ultimate question of likelihood of confusion as to the source of the product.” Lois Sportswear, U.S.A., Inc. v. Levi Strauss & Co., 799 F.2d 867, 872 (2d Cir. 1986).

Strength of the Plaintiff’s Mark

The inquiry regarding the strength of the plaintiff’s mark “focuses on ‘the distinctiveness of the mark, or more precisely, its tendency to identify the goods’ as coming from a particular source.” Lang v. Retirement Living Publ’g Co., 949 F.2d 576, 581 (2d Cir. 1991), quoting McGregor-Doniger Inc. v. Drizzle Inc., 599 F.2d 1126, 1131 (2d Cir. 1979).

The Museum owns numerous incontestable registered trademarks for a variety of goods and services, such as stationery, arts and crafts, household items, games, artwork reproductions, books, clothing, other general merchandise, entertainment and art services, and museum services. Therefore, the Museum’s mark is presumptively distinctive for these categories of goods and services. The Museum does not, however, own any trademarks specifically covering beverages.

Even without this presumption, the Museum’s mark is distinctive. “Courts assess inherent distinctiveness by classifying a mark in one of four categories arranged in increasing order of inherent distinctiveness: (a) generic, (b) descriptive, (c) suggestive, or (d) fanciful or arbitrary.” Brennan’s, Inc. v. Brennan’s Restaurant, LLC, 360 F.3d 125, 131 (2d Cir. 2004), citing Streetwise Maps, Inc. v. VanDam, Inc., 159 F.3d 739, 744 (2d Cir. 1998); Estee Lauder Inc. v. The Gap, Inc., 108 F.3d 1503, 1508 (2d Cir. 1997). “Generic marks are those consisting of words identifying the relevant category of goods or services.” Star Indus., Inc. v. Bacardi & Co., 412 F.3d 373, 385 (2d Cir. 2005). “Descriptive marks are those consisting of words identifying qualities of the product.” Id. “Suggestive marks are those that are not directly descriptive, but do suggest a quality or qualities of the product, through the use of ‘imagination, thought and perception.’ ” Id. (quoting Time, Inc. v. Petersen Publ’g Co., 173 F.3d 113, 118 (2d Cir. 1999) ). “Arbitrary or fanciful marks are ones that do not communicate any information about the product either directly or by suggestion.” Star Indus., 412 F.3d at 385.

The Museum’s mark is descriptive because the acronym “MoMA” stands for “Museum of Modern Art.” The mark plainly communicates that MoMA is a museum that displays modern art. See Nature’s Bounty, Inc. v. Basic Organics, 432 F.Supp. 546, 552 (E.D.N.Y. 1977) (finding that the acronym “B-100” was descriptive because “the primary purpose and effect of the designation ‘B-100’ is to denote and describe the ingredients and qualities,” namely the Vitamin B product and its potency level). … The Museum’s mark is therefore not arbitrary or fanciful, as the Museum argues, with respect to its display of artwork. The Museum’s mark is, however, arbitrary in connection with the Museum’s sale of food and beverages, as the acronym “MoMA” does not communicate any information about the Museum’s cafés or restaurants.

“If an unregistered mark is deemed descriptive, proof of secondary meaning is required for the mark to be protectible.” Thompson Medical Co. v. Pfizer Inc., 753 F.2d 208, 216 (2d Cir. 1985). … The Museum has exclusively used its “MOMA” or “MoMA” mark for a significant length of time–nearly 50 years. It has owned some of its registered trademarks since 1967. Id. The Museum advertises and promotes its services under its mark in a variety of print and digital publications, such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker, Art in America, Variety, Hollywood Reporter, WNET, New York Magazine, Vice, and Gothamist. Id. The Museum has also received significant media coverage. Id. For example, a New York Times article, dated September 21, 2003, featured a spread on the Museum and its redesigned logo. Id. The article included a large image of the logo, underneath which mentioned the proprietary “new MoMA Gothic” font as well as the “Franklin Gothic # 2” font. Id.

Additionally, MOMACHA’s use of a font and style highly similar to those of the Museum’s mark for its old logo constitutes an attempt to copy the Museum’s mark. As a result, some MOMACHA consumers on social media have assumed that MOMACHA is affiliated with the Museum, demonstrating that consumers recognize the Museum’s mark and associate similar marks with the Museum. Therefore, the Museum’s exclusive use of its mark for a significant length of time, its advertising in numerous publications, its unsolicited press coverage, and MOMACHA’s attempt to copy the Museum’s mark all support the finding that the mark has acquired secondary meaning in the public mind.

…

The Museum’s mark is strong and distinctive, and identifies its goods as coming from the Museum. As a result, the use of a similar mark on a product from a different source is likely to confuse consumers into associating the product with the Museum.

Similarity of the Parties’ Marks

In considering the similarity of the parties’ marks, courts look to two questions: “1) whether the similarity between the two marks is likely to cause confusion and 2) what effect the similarity has upon prospective purchasers.” Sports Auth., Inc. v. Prime Hospitality Corp., 89 F.3d 955, 962 (2d Cir. 1996). … “[M]arks are considered similar when they are similar in appearance, sound and meaning.” Clinique Labs., Inc. v. Dep Corp., 945 F.Supp. 547, 552 (S.D.N.Y. 1996).

…

MOMACHA’s original mark is highly similar in appearance to the Museum’s mark. It uses the same black and white coloring. It capitalizes both “M”s in its name. It employs a similar bold font resembling Franklin Gothic and the Museum’s proprietary font. The image of the overlay of the Museum’s proprietary font on top of MOMACHA’s old logo demonstrates that the two fonts are almost exactly the same. MOMACHA’s display of its original logo on coffee cups both horizontally and vertically greatly resembles the Museum’s mark and the manner in which it is displayed on the Museum’s building. Although the capitalization in “MoMaCha” is slightly different from that of “MoMA”–the “a” in “MoMaCha” is lowercase–the unique alternating capitalization of the first three letters is nonetheless likely to confuse the public, especially if those letters are in the same bold font and in the same black-and-white coloring.

MOMACHA’s old mark is presented in the marketplace in a manner that is likely to cause consumer confusion. The names of the Museum’s other satellite locations (MoMA Design Stores, MoMA QNS, and MoMA PS1) all begin with the letters “MoMA,” followed by certain identifying letters or numbers. They are also all located in New York City. As a result, the public might mistakenly assume that “MoMaCha” is another one of the Museum’s satellite locations in New York City due to MOMACHA’s unique name and mark.

…

MOMACHA’s new logo is not highly similar in appearance to the Museum’s logo, as the new logo uses a significantly different font, and capitalizes all of the letters in “MOMACHA.” The Museum argues that MOMACHA’s new logo is still similar because it continues to emphasize each syllable of “MOMACHA” by separating “MO,” “MA,” and “CHA,” into three different lines. The Museum argues that the mark is thus merely “MoMA” combined with the added descriptive element “cha,” meaning tea in Mandarin. Id. MOMACHA counters that its name is based on the combination of the two words “more” and “matcha,” not “MoMA” and “cha.” Neither party’s argument is compelling, as the mark is not separated into two lines “MOMA” and “CHA,” nor is it separated into “MO” and “MACHA.” The separation of syllables into three lines alone is insufficient to make a finding that MOMACHA’s new logo looks or sounds similar to the Museum’s mark.

MOMACHA’s new logo still has some similarities to the Museum’s marks in appearance, meaning, and as presented in the marketplace, however. First, the dominant features (strong block letters in black-and-white coloring) remain the same. Second, although the change eliminates the “MoM” capitalization similarity, the capitalization of “CHA” creates another similarity with some of the Museum’s satellite locations. MoMA QNS and MoMA PS1, for example, both consist of the letters “MoMA” followed by three characters with all of its letters capitalized. It would thus not be unreasonable for someone to believe that “MOMACHA” is another one of the Museum’s satellite locations, despite the capitalized “O” and lack of a space between “MOMA” and “CHA.”

Overall, MOMACHA’s old logo is highly similar in appearance to the Museum’s logo, but the new logo is somewhat less so. However, MOMACHA still continues to display its old logo on its cups and social media accounts. Consumers are thus likely to believe, despite the display of a different logo in most other areas of the café, that MOMACHA is still affiliated with the Museum.

…

Because MOMACHA’s old logo is highly similar to the Museum’s mark, and the new mark and disclaimers have not been shown to have eliminated consumers’ previous confusion, this factor weighs in favor of finding a likelihood of confusion.

Competitive Proximity of the Products

“This factor focuses on whether the two products compete with each other.” Lang, 949 F.2d at 582. … The court may consider “whether the products differ in content, geographic distribution, market position, and audience appeal.” W.W.W. Pharm. Co. v. Gillette Co., 984 F.2d 567, 573 (2d Cir. 1993).

…

The Museum and MOMACHA are not necessarily in direct competition with each other, as the Museum contains approximately 200,000 works of art, and MOMACHA is a smaller café and gallery. However, both the Museum and MOMACHA display modern artwork and offer café and beverage services in an art gallery setting. They also both sell items in relation to the art they display. Thus, the parties’ goods and services are essentially the same in content. The Museum and MOMACHA have the same geographic location and audience appeal as well. They are both located in New York City and draw the same audience of New York tourists and residents who choose to enjoy modern art and relax with a beverage. Social media posts about MOMACHA using the hashtags “#museum,” “#gallery,” “#newyorkart,” and “#modernart” further strengthen the relatedness of services in consumers’ minds. Published articles about MOMACHA including phrases such as “modern art experience,” “art installation,” and “[t]he café, whose name is a play on MoMa’s, also doubles as a gallery,” have the same confusing effect.

MOMACHA’s argument that the services provided by the Museum “are completely different” because the Museum sells prints and reproductions of art instead of original artwork is unconvincing. Both types of products depict the modern and contemporary art that visitors appreciate inside the Museum and MOMACHA, and both are utilized for the purposes of decoration and visual enjoyment. … Therefore, the close proximity of the parties’ goods and services is likely to result in the belief that MOMACHA is connected with the Museum.

…

Actual Confusion

“It is self-evident that the existence of actual consumer confusion indicates a likelihood of consumer confusion.” Virgin Enters. Ltd. v. Nawab, 335 F.3d 141, 151 (2d Cir. 2003). …

Although the Museum has not provided survey evidence, the Museum provides multiple anecdotal instances of actual confusion. Specifically, the Museum cites an email it received from an attorney who thought “the style of the font and the display of the [MoMaCha] name looked so much like the familiar MoMA logo” that he needed to confirm whether MOMACHA was affiliated with the Museum. The Museum also points to social media posts by consumers who believed that MOMACHA’s beverages are affiliated with the Museum. One such post contained an image of a MOMACHA drink with latte foam art in the shape of MOMACHA’s old logo. Id. The post’s author included a caption alongside the photo, which stated, “When a museum makes Machas.” Id. Another post showed a picture of a MOMACHA drink decorated with latte foam art in the shape of a marijuana leaf. Id. Someone commented on the post, “I haven’t been to MoMa in a while! Great excuse.” Id. These examples refute MOMACHA’s claim that no instance of actual confusion has involved a MOMACHA consumer.

MOMACHA’s claim that no confusion has occurred since MOMACHA added disclaimers and changed its logo is incorrect. On May 15, 2018, after MOMACHA made its changes, a MOMACHA customer posted on Yelp, a crowd-sourced review forum, stating that she “thought it was affiliated with the moma.” This demonstrates that MOMACHA’s changes have not effectively dispelled consumer confusion.

Defendant’s Good Faith in Adopting the Mark

The good-faith factor “looks to whether the defendant adopted its mark with the intention of capitalizing on plaintiff’s reputation and goodwill and any confusion between his and the senior user’s product.” Lang, 949 F.2d at 583 (citation and internal quotation marks omitted).

It is more likely than not that MOMACHA intentionally copied the Museum’s mark in bad faith when it adopted its old logo. As discussed above, the marks are strikingly similar and almost identical in terms of the font style, coloring, and capitalization. The social media posts of the designer of MOMACHA’s old logo consisting of numerous photos of the Museum and MoMA PS1 exhibits demonstrate that she frequented the Museum’s locations and was aware of the Museum’s logo. It thus seems probable that MOMACHA created and adopted its logo with the intent of copying the Museum’s mark. See MetLife, Inc. v. Metro. Nat’l Bank, 388 F.Supp.2d 223, 234 (S.D.N.Y. 2005) (finding “circumstantial evidence of bad faith” because “the similarity between the parties’ marks is such that it strains credulity to believe that neither MNB nor the firm it hired to redesign its logo were not consciously influenced by the MetLife logo.”).

…

It may later be rebutted, but on the present record it appears that MOMACHA’s similarity to the Museum’s mark was not accidental, but purposive.

…

Sophistication of the Purchasers

“Generally, the more sophisticated and careful the average consumer of a product is, the less likely it is that similarities in trade dress or trade marks will result in confusion concerning the source or sponsorship of the product.” Bristol-Myers Squibb, 973 F.2d at 1046. “The greater the value of an article the more careful the typical consumer can be expected to be ….” McGregor-Doniger, 599 F.2d at 1137, superseded by rule on other grounds as stated in Bristol-Myers Squibb, 973 F.2d at 1044.

There are certainly many sophisticated visitors of the Museum and MOMACHA, such as art enthusiasts, historians, collectors, and other artists. However, art museums and galleries attract the general public, including both tourists and residents. The cost of viewing art in galleries and museums is relatively low. The Museum offers reduced prices for students and seniors, free admission on Friday afternoons, free school tours, and free admission for children under the age of 16 years. As a result, a significant amount of the Museum’s and MOMACHA’s visitors are likely to be unsophisticated and unknowledgeable about the art being displayed.

Similarly, the cost of a beverage is relatively low, and an average consumer of tea or coffee is thus unlikely to be discerning when buying a beverage from either party. Assuming that a large share of MOMACHA customers are not art or tea experts but casual viewers interested in enjoying specialty beverages, they may be more vulnerable to associating MOMACHA with the Museum.

This factor weighs in favor of finding a likelihood of confusion.

Weighing the Factors

In weighing the Polaroid factors, no single factor is dispositive. Brennan’s, Inc., 360 F.3d at 130. However, the first three factors-strength of the mark, similarity of the marks, and competitive proximity of the goods and services–are “perhaps the most significant in determining the likelihood of confusion.” Mobil Oil Corp. v. Pegasus Petroleum Corp., 818 F.2d 254, 258 (2d Cir. 1987). Taken as a whole, the Polaroid factors weigh in favor of finding a likelihood of confusion.

The Museum has shown that it is likely to succeed on the merits of its trademark infringement and unfair competition claims.

…

Because the Museum has demonstrated irreparable harm, a likelihood of success on the merits, sufficiently serious questions going to the merits to make them a fair ground for litigation, and that the balance of hardships tilts in its favor, the Museum is entitled to a preliminary injunction.

CONCLUSION

The Museum’s motion for a preliminary injunction (Dkt. No. 7) is granted and Defendants are enjoined from using, displaying, or promoting the MOMA or MOMACHA marks, and the https://momacha.com/ domain name, during the pendency of this action.

So ordered.

Commentary – Trademark Law

Trademark laws exist to inform consumers of the source of origin for the goods and services they consume. The source of origin conveys a great deal of information, including quality and uniqueness of the product or service, reputation of the markholder, goodwill inherent to the business, and brand identity.

Trademarks also help consumers distinguish between similar products and services. Consider three familiar fast food burger chains: the golden arches of McDonalds are uniquely different from the burger-shaped logo of Burger King and the smiling star logo of Hardees. Preventing confusion in the marketplace thus requires a business owner to own a strong or distinctive mark that enables the general public to make informed purchasing decisions. Trademarks can also help markholders protect their brands by preventing others from adopting similar marks.

Figure 1: Example of confusing marks

Types of Trademarks

A trademark can be a word, name, symbol, or device when it is used as a source of origin to distinguish goods and services. A trademark can also be registered for services, trade dress, a collective organization or association, and certification for a particular geographic region or to meet certain quality standards. Trademarks may consist of colors, sounds, and scents. Famous trademark examples include the robin egg blue color associated with New York City jeweler Tiffany & Co., the three-note chime for the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), and the salty, wheat-based smell of Hasbro’s Play-Doh scent.

State and Federal Trademark Law

Trademarks can be protected under both federal and state law. At the federal level, Congress enacted the Lanham Act, the primary federal trademark statute in the United States, located in Chapter 22 of Title 15 of the U.S. Code. State trademark law varies depending on state trademark statutes and common law unfair competition principles.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is the federal agency that oversees the Lanham Act and governs trademark registration policies and procedures. The USPTO also advises the federal government on intellectual property policy, both domestic and abroad. The Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure is a helpful resource that details the trademark application examination process that occurs at the federal level.

Trademark owners can seek protection outside of the United States based on international agreements, including (1) the Madrid System and (2) the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property. Regional organizations also exist to help applicants file a single application for the protection of a trademark in designated countries that have signed regional trademark law agreements, such as the Andean Pact, the African Intellectual Property Organization, and the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization.

Requirements for Federal Trademark Protection

There are two requirements before a trademark designation can receive federal protection: (1) the mark must be distinct and (2) the mark must be used in interstate commerce.

Use in commerce is established when a good is transported or sold across state lines and the good has the trademark displayed on a tag, the container, or the good itself. Use is also established for services when the trademark is used on advertising materials that are distributed to different states. For state-level protection, use in commerce is established through use within the state. Without federal registration, state rights are limited to the geographical area in which the mark is used.

The distinctiveness of a mark is evaluated along a spectrum ranging from highly distinctive marks to generic terms. In order of most distinctive, the categories are generally classified as (1) fanciful (2) arbitrary (3) suggestive (4) descriptive and (5) generic.

Figure 2: Spectrum of Distinctiveness

Source: yaymark.com/dwkb/strength-of-a-trademark/

A distinctive mark is a strong mark. When a mark is inherently distinctive, a consumer can immediately identify the source of origin for the good or service. Marks that are fanciful, arbitrary, or suggestive are considered inherently distinctive and can be registered on the USPTO’s Principal Register instead of the Supplemental Register. Listing on the Principal Register carries several advantages and presumptions, such as a presumption of validity and the ability for the mark to gain incontestable status. Marks that are not inherently distinctive can acquire distinctiveness or secondary meaning over time with continuous use and promotion of the mark. Evidence of acquired distinctiveness can include long-term use, sales and advertising expenditures, and survey feedback.

Trademark Infringement

Trademark infringement is the unauthorized use of a trademark on or in connection with goods or services in a manner that is likely to cause confusion, deception, or a mistake about the source origin of the goods or services.

Likelihood of Confusion Test

Determining trademark infringement occurs by performing a likelihood of confusion test. Courts will consider various factors to determine whether consumers are likely to be confused by similar marks. The key factors that courts consider include (1) the degree of similarity between the two marks and (2) whether the parties’ goods and services are sufficiently related that customers may mistakenly assume that they originate from the same source of origin. Courts also look at the parties’ use of marketing, advertising, and trade channels, the range of prospective consumers of the goods and services, evidence of actual confusion, the defendant’s intent in adopting its mark, and the strength of the plaintiff’s mark. The particular factors in this multi-factor test varies depending on the federal circuit. The weighting of the factors can also depend on the extent and quality of evidence available to the court.

Unfair Competition Claims

Unfair competition claims comprise a wide range of deceptive or wrongful business practices that confuse customers and result in economic injury. Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act discusses several categories of unfair competition claims including false advertising and misrepresentation of goods and services.

Lanham Act Section 43(a)

§1125 FALSE DESIGNATIONS OF ORIGIN, FALSE DESCRIPTIONS, AND DILUTION FORBIDDEN

(a) Civil action

(1) Any person who, on or in connection with any goods or services, or any container for goods, uses in commerce any word, term, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof, or any false designation of origin, false or misleading description of fact, or false or misleading representation of fact, which—

(A) is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive as to the affiliation, connection, or association of such person with another person, or as to the origin, sponsorship, or approval of his or her goods, services, or commercial activities by another person, or

(B) in commercial advertising or promotion, misrepresents the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of his or her or another person’s goods, services, or commercial activities,

shall be liable in a civil action by any person who believes that he or she is or is likely to be damaged by such act.

False Advertising

Pursuant to Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, false advertising claims can be brought by plaintiffs who have been commercially injured by a defendant’s false, deceptive, or misleading representations in advertising that are intentionally used to promote the sale of the good or service to the public. A representation can include a statement, term, symbol, or device that conveys a false or misleading message to consumers about a certain characteristic of a good or service. Examples of false or misleading advertising messages include a product name that falsely suggests a geographic origin, a television commercial misrepresenting a product’s failure to function, or a statement that implies a function or quality that the product does not have.

Circuit courts analyze false advertising claims differently, however, the most common elements of a false advertising claim include (1) the defendant made false or misleading statements in a commercial advertisement about a product or service; (2) the statement deceived or had the capacity to deceive a substantial category of potential consumers; (3) the deception is material because it is likely to influence purchasing decisions of consumers; (4) the statement is made in interstate commerce; and (5) the statement has injured or is likely to injury the plaintiff.

A failure to disclose facts through omission is not considered grounds for a false advertisement claim. Also, mere puffery may be permitted as these statements are not likely to be taken as an objectively true fact by a reasonable consumer. Examples of puffery include claims of superiority that are generally understood as an opinion and exaggerated or funny claims.

Figure 3: Puffery or False Advertisement?

Overseas Publishing Association Amsterdam BV (OPA) v. American Institute of Physics, 973 F.Supp. 414 (SDNY 1997)

In OPA, commercial publishers of scientific journals sued non-profit physics societies to prevent the societies from claiming in promotional materials that their publications were more “cost-effective” or “better bargains” than those published by the commercial publishers. The commercial publishers claimed that the studies relied on by the physics societies did not measure cost-effectiveness and that the promotions were false representations of fact in violation of Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act.

The physics societies made the “cost-effective” claims in response to a 1986 article written by physicist Henry Barschall who theorized that “science libraries all over the United States face serious financial problems associated with the increased costs of journals.” In his article, Barschall calculated the cost per thousand characters figure (“cost/kilocharacter”) per page of several journals, including those published by both the plaintiff and defendant. Barschall’s study showed that the physics societies’ publications had lower costs per printed word than those of the commercial publishers. Barschall’s article also suggested that libraries consider cost/kilocharacter calculations when making purchasing decisions:

Libraries benefit greatly from the low cost per printed word of journals published by AIP and its member societies. These journals also have larger circulations and wider readerships than commercial journals …. As chairman of our physics department’s library advisory committee, I have the unpleasant task of advising our librarian on which journal subscriptions to cancel. Obviously the most important considerations are how many people use the journal and whether the journal is available elsewhere on the campus. But I also look at cost, and my opinion is influenced not only by the price of the journal but also by the price per printed word (Barschall 36).

Given Barschall’s study results, physics societies distributed the study promotionally to libraries prior to the deadline when subscription renewals were due, adding that their publications were a “great bargain” compared to other journals, including plaintiffs’ publications. In 1988, Barschall conducted another study of over 200 physics journals that measured cost/kilocharacter and a citations-based “impact factor.” The commercial publishers again fared poorly in the study. The physics societies planned to distribute a promotional bulletin with the second Barschall study results but stopped when the commercial publishers threatened to sue.

The commercial publishers ultimately filed a false advertising claim. The court noted that to succeed in a claim brought pursuant to Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, the plaintiffs must demonstrate that the advertisement is either literally false or is likely to mislead and confuse consumers. Because the plaintiffs failed to show that Barschall’s conclusions were false, the court held that Barschall’s methodology was sufficiently sound and reliably established the study’s results, including the journal rankings based on Barschall’s measures. The court also noted that the 1988 Barschall article qualified the use of the term “cost-effective” and did not imply that the study was the only way for libraries to measure cost-effectiveness. The court further noted that the defendants’ promotional materials did not contain an implied message that journal purchase decisions should be based solely on Barschall’s study, contrary to plaintiffs’ assertions. Even if a librarian were to rely on Barschall’s study to the exclusion of other indicators in making purchasing decisions for collections, the court noted this consideration would still not make Barschall’s study or the defendants’ descriptions of the study false.

Misrepresentation of Goods & Services or Origin

Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act also provides an avenue for actionable claims dealing with false or misleading descriptions of goods and services or misrepresentations regarding the origin of a product. Plaintiffs also refer to a false designation of origin claim as a passing off claim. False designation of origin claims can also be pursued as false advertising claims. A false designation of origin claim usually occurs when the defendant expressly or implicitly misrepresents its goods or services for the plaintiff’s goods or services. Counterfeiting claims fall into this category.

Misrepresentation can also be actionable as a common law fraud claim under state law. Depending on the relevant jurisdiction, there may be different standards and requirements for proving misrepresentation. To plead the material misrepresentation of the common law fraud claim, the plaintiff generally must (1) allege an affirmative representation made by the defendant or the defendant’s knowing concealment or failure to disclose a material fact; (2) allege the representation was false; and (3) prove the relevant materiality standard (dependent upon jurisdiction). Opinions, puffery, valuations, and statements about the future would not be actionable misrepresentation claims.

Figure 4: False Designation of Origin and Counterfeit Goods

Source: A New Louis Vuitton Lawsuit

POM Wonderful LLC v. The Coca-Cola Company, 134 S.Ct. 2228 (2014) and 166 F.Supp. 3d 1085 (2016)

POM Wonderful LLC produces, markets, and sells a pomegranate-blueberry juice blend. Its competitor, the Coca-Cola Company also sells a pomegranate-blueberry juice product. POM Wonderful sued Coca-Cola for misrepresentations of the name, label, marketing, and advertising as it misleads consumers to think that the product consists mainly of pomegranate and blueberry juices when in fact the product consists mostly of cheaper alternatives – apple and grape juices. In fact, Coca-Cola’s product contained only 0.3% pomegranate juice and 0.2% blueberry juice. POM argued that these misrepresentations were deceptive and misleading, and caused the company to lose sales. Coca-Cola argued that POM’s advertising was also deceptive and misleading by describing its Pomegranate-Blueberry juice product as Pomegranate Blueberry 100% Juice even though POM’s product also contained plum, pineapple, apple, and blackberry juices.

Commentary – Patent Law

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the right to exclude others from making, using, offering to sell, selling, or importing a patented invention for a limited time. When another party engages in any of these activities without the patent owner’s permission, the patent owner can raise an infringement action.

Patent law is underpinned by Article 1, Section 8, clause 8 of the US Constitution, which grants to the Congress the power to grant patents:

The Congress shall have the Power To … promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries…

Patent law serves to promote the progress of science and useful arts by giving inventors exclusive rights to their patented inventions to encourage investment in scientific industries and incentivizing the early disclosure of useful inventions. Patent law benefits inventors by giving them a limited monopoly over their inventions. Once patents expire, the public also benefits by being able to copy the inventions. The first patent statute was enacted in 1790 and was revised in the Patent Act of 1952. In 2011, the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act was enacted and consisted of several important changes to US patent law.

A patent is granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) in exchange for public disclosure of the invention. The USPTO publishes the Manual of Patent Examination Procedure (MPEP), which provides excellent information about the examination of a patent application. US federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction over patent infringement actions and USPTO decisions. Patent protection for a US patent generally extends to infringing conduct within the United States. To protect a patent globally, a patent must be filed in the country or region where patent protection is needed. Similar to trademark law, certain treaties facilitate patent applications across the globe, such as the Patent Cooperation Treaty.

Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA)

The Leahy-Smith American Invents Act (AIA) shifted US patent law from a first-to-invent patent system to a first-to-file patent system. The AIA first-to-file patent provisions apply to all patents and patent applications that have a claim with an effective date of on or after March 16, 2013. The AIA establishes certain categories of activities that may prevent an inventor from obtaining a patent and may be used to render a patent invalid. Among these activities include describing the claimed invention in a printed publication and publicly using the claimed invention.

Patent Act of 1952

Pursuant to the US Patent Act of 1952, the USPTO may grant three types of patents: (1) utility patents; (2) design patents; and (3) plant patents. Utility patents protect new, nonobvious, and useful inventions, including products, processes, machines, and devices. Utility patents are the most common type of patent and protect the “functional” aspects of an invention, including how an invention works or is made. A famous example of a utility patent is the artificial heart valve. A typical utility patent includes an abstract, drawings or illustrations, descriptive specifications, and a numbered listing of claims. Design patents protect new, original, and ornamental designs of manufactured articles. Examples of design patents include the original curvy Coca-Cola bottle, the Manolo Blanik shoe design, and an IKEA chair. Plant patents protect certain distinct and new plant varieties. Some examples of plant patents include a variety of an almond tree or the Hass avocado.

Pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 154, the scope of rights exclusive to a patent owner include the following:

- Making the patented invention within the US;

- Using the patented invention within the US;

- Selling the patented invention within the US;

- Offering to sell the patented invention within the US; or

- Importing the patented invention into the US.

These rights last for a certain duration of time. In general, utility patents and plant patents that are filed on or after June 8, 1995 have a term which expires 20 years after the filing date of the earliest US patent application that claims domestic protection, provided that the inventor pays the required maintenance fees to the USPTO during the life of the patent. Design patents filed on after May 13, 2015 have a term of 15 years from the issue date. Once you are granted a utility patent, you are not immediately entitled to make, use, or sell an invention until a patent attorney conducts a freedom-to-operate analysis.

Patent Requirements

An invention must meet certain criteria before it can be patented. The basic requirements for obtaining a utility patent include (1) usefulness (utility); (2) subject matter eligibility; (3) novelty; (4) nonobviousness; and (5) adequately described. The first requirement, utility, means that the invention must be useful for some purpose, and must work and do what is claimed.

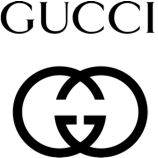

An invention must also fall into one of the following four statutory categories that Congress deems to be eligible subject matter: (1) processes; (2) machines; (3) manufactures; and (4) compositions of matter.

Categories of ineligible subject matter include abstract ideas, laws of nature, and natural phenomenon. These categories represent “the basic tools of scientific and technological work,” and by granting a limited monopoly through patent protection, innovation would be stifled rather than encouraged. See Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 216, 110 USPQ2d at 1980; Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 71, 101 USPQ2d 1961, 1965 (2012).

Figure 5: Subject Matter Eligibility Flowchart

Source: www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2106.html

The statutory requirement of novelty requires that an invention not be disclosed in any prior art. Prior art means all information that has been made available to the public that might be relevant to a patent’s claim of originality. The AIA broadened the scope of prior art to include information disclosed before the effective filing date of the patent application rather than the date when the invention was made. If an invention has been described in prior art, then the invention does not meet the novelty requirement.

The statutory requirement of nonobviousness requires that an invention must not be obvious such that a person of ordinary skill in a relevant field could easily make the invention based on prior art. For example, if there are a number of references to prior art that, when combined, create the invention, the invention is obvious and a patent application may be denied. Obviousness is a fact-based and subjective inquiry and a difficult hurdle to overcome in the patent examination process.

A patent must also be sufficiently described. In fact, the description must be written in such a way that someone who was knowledgeable in the subject area would recognize that the applicant had possession over the invention when the application was filed.

Alice Corporation Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014)

In Alice Corp Ptd. Ltd. (Alice), the US Supreme Court announced a major change in the law on patent subject matter eligibility. The patent owner, Alice Corporation, asserted that its patent claims for a computer-implemented financial settlement system were valid because they were not “abstract ideas.” The Court disagreed, however, unanimously holding that generic computer implementation does not transform a patent-ineligible abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention:

The Court has long held that § 101, which defines the subject matter eligible for patent protection, contains an implicit exception for “ ‘[l]aws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas.’” Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. 576 (2013). In applying the § 101 exception, this Court must distinguish patents that claim the “ ‘buildin[g] block[s]’” of human ingenuity, which are ineligible for patent protection, from those that integrate the building blocks into something more, thereby “transform[ing]” them into a patent-eligible invention. Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012).

…

[T]his Court has found ineligible patent claims involving an algorithm for converting binary-coded decimal numerals into pure binary form, id., at 71–72; a mathematical formula for computing “alarm limits” in a catalytic conversion process, Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 594–595; and, most recently, a method for hedging against the financial risk of price fluctuations, Bilski, 561 U.S., at 599. It follows from these cases, and Bilski in particular, that the claims at issue are directed to an abstract idea. On their face, they are drawn to the concept of intermediated settlement, i.e., the use of a third party to mitigate settlement risk. Like the risk hedging in Bilski, the concept of intermediated settlement is “ ‘a fundamental economic practice long prevalent in our system of commerce,’ ” ibid., and the use of a third-party intermediary (or“clearing house”) is a building block of the modern economy. Thus, intermediated settlement, like hedging, is an “abstract idea” beyond § 101’s scope (Alice 2355-2357).

The holding in Alice has the effect of broadening the scope of ineligible subject matter, and the USPTO has found that the likelihood of receiving a first office action with a rejection for patent-ineligible subject matter increased by 31% in over 30 technology fields after Alice was decided by the US Supreme Court (USPTO, Adjusting to Alice).

Patent Infringement Claims

Similar to trademarks and copyrights, patents can also be infringed if a patent owner’s exclusive rights are transgressed without the owner’s permission. Infringement may be difficult to detect on the surface. When two products look the same and perform the same function, infringement may not be present. For example, two convertibles with the same body style may run equally effectively and efficiently, but one may have a gas engine and the other may have a diesel engine. The engine designs may also be built in a completely different manner. To constitute infringement, an infringer must use all of the elements of an eligible patent claim.

There are several categories of infringement, however the most common types include direct infringement and indirect infringement. Direct infringement occurs when every element of a patent claim is found in the allegedly infringing product or process. Indirect infringement occurs when a potential infringer induces another party to engage in direct infringement. Pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 271(b), a person who induces this conduct will also be held liable for infringement. Inducement means the actual knowing and aiding and abetting of direct infringement.

Several defenses are available to patent infringers, such as claiming that the infringed patent was invalid in the first instance or showing that there was no actual infringement. However, patent claims should be taken seriously as the remedies available in infringement actions are substantial. In exceptional circumstances, an aggrieved patent owner can be awarded up to three times the damages and attorneys fees.

Scenarios

Scenario 1:

You are the Assistant Director of Emerging Technologies at the State Library, Museum, and Archives. You are responsible for the Makerspace Lab and 3D printing. A colleague from Special Collections asks you for a favor. A local historian recently donated a slide projector from the 1950s and a William Austin Burt typographer, which was a model of an early typewriter first produced in 1829. The machines do not work, however your colleague knows how to get them working again. Because the machines are so old, your colleague asks you to 3D print the missing parts that would fix the machines. You are willing to help – after all, you have been volunteering in your spare time to design CAD files and 3D print valves for breathing machines at two local hospitals in town that have experienced shortages in PPP equipment during the COVID-19 crisis. Discuss the legal considerations involved with the 3D printing activity for on and off campus use. Is there infringement? Why or why not?

Scenario 2:

You are the Curator of a modern art museum in New York City. You recently created an exhibition displaying the works of a famous graffiti artist. The artist approaches you to see if the gift store of the museum would sell merchandise featuring the collection of art, including greeting cards and t-shirts. What legal guidance do you provide the graffiti artist? What are the legal risks for the museum, if any?

Works Consulted

Alice Corporation Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).

Barschall, H.H. “The Cost of Physics Journals.” Physics Today, vol. 39, no. 12, Dec. 1986, pp. 34-36.

Holbrook, Timothy R. and Osborn, Lucas S. “Digital Patent Infringement in an Era of 3D Printing.” University of California, Davis Law Review, Vol. 48, 2015, pp. 1319-1385, lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/48/4/Articles/48-4_Holbrook-Osborn.pdf.

Lanham (Trademark) Act, Pub. L. 79–489, 60 Stat. 427, July 5, 1946, codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1051 et seq.

Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), Pub. L. 112–29, 125 Stat. 284, September 16, 2011.

Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 71, 101 USPQ2d 1961, 1965 (2012).

McCarthy, J. Thomas. McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition. Thomson Reuters, 1996-2017.

The Museum of Modern Art v. MOMACHA IP LLC and MOMACHA OP LLC, 339 F. Supp. 3d 361 (SDNY 2018).

“A New Louis Vuitton Lawsuit Shows Its Strategic Approach to Brand Protection,” The Fashion Law, Nov. 12, 2018, www.thefashionlaw.com/a-new-louis-vuitton-lawsuit-shows-its-strategic-approach-to-brand-protection/.

Overseas Publishing Association Amsterdam BV (OPA) v. American Institute of Physics, 973 F.Supp. 414 (SDNY 1997).

Pantalony, Rina E. Managing Intellectual Property for Museums. World Intellectual Property Organization, 2013, www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/copyright/1001/wipo_pub_1001.pdf

Patent Act of 1952, Pub. L. 82–593, 66 Stat. 792, July 19, 1952, codified at 35 U.S.C. § 1 et seq.

POM Wonderful LLC v. The Coca-Cola Company, 134 S.Ct. 2228 (2014) and 166 F.Supp. 3d 1085 (2016).

U.S. Const., Art. I, § 8, cl. 8.

U.S.P.T.O. Adjusting to Alice, www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/OCE-DH_AdjustingtoAlice.pdf.

—. Laws, regulations, policies, procedures, guidance and training, www.uspto.gov/patent/laws-regulations-policies-procedures-guidance-and-training.

—. Protecting Your Trademark: Enhancing Your Rights Through Federal Registration, www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/BasicFacts.pdf.

Yaymark, “Strength of a Trademark,” yaymark.com/dwkb/strength-of-a-trademark/.

Author

Agnes Beatrice Gambill West is Head of Scholarly Communication and Assistant Professor at Appalachian State University. In addition to working with the Office of General Counsel on various legal issues that libraries and archives encounter, she is the Coordinator of the Digital Humanities Lab and serves on Appalachian’s Intellectual Property Development Council. She was also appointed by the Office of the Lieutenant Governor to serve as the Co-Chair of the North Carolina Blockchain Initiative (NCBI), a nonpartisan initiative that aims to advance blockchain innovation in North Carolina. She is a graduate of the University of North Carolina School of Law (JD), Oxford University (MSc), and Duke University School of Law (LLM).