6 Module 6: Early Childhood Development

Module 6 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Describe Physical Growth

Explain the typical physical growth patterns in early childhood and the factors that influence healthy development. - Understand Brain Development

Summarize key changes in brain structure and function during early childhood, including the role of myelination and hemispheric growth. - Discuss Nutritional Concerns

Explain the importance of proper nutrition in early childhood and identify common nutritional challenges, such as iron deficiency and childhood obesity. - Examine Motor Skills

Differentiate between gross and fine motor skills, providing examples of how they develop in early childhood. - Analyze Sexual Development

Discuss the emergence of curiosity about the body and appropriate ways to address early childhood sexual development. - Understand Cognitive Development

Summarize Piaget’s preoperational stage and explain cognitive concepts such as egocentrism, conservation, and animism. - Explore Theory of Mind

Explain how the development of theory of mind influences social interactions and the ability to understand others’ perspectives. - Examine Language Development

Discuss how children’s vocabulary grows during early childhood and the role of fast mapping in language acquisition. - Understand Gender Identity Development

Describe how children develop gender identity, including the influence of socialization and cultural norms. - Analyze Self-Concept

Explain how children develop self-awareness, self-control, and a sense of self during early childhood. - Evaluate Learning Strategies

Compare the effects of different learning strategies, like reinforcement and modeling, on children’s behavior and emotional development. - Discuss Social and Emotional Growth

Explain how children develop emotional regulation, empathy, and social skills through interactions with caregivers and peers.

Early Childhood Physical Development

Growth in Early Childhood

Children between the ages of 2 and 6 years tend to grow about 3 inches in height each year and gain about 4 to 5 pounds in weight each year. The average 6-year-old weighs about 46 pounds and is about 46 inches in height. The 3-year-old is very similar to a toddler with a large head, large stomach, short arms and legs. But by the time the child reaches age 6, the torso has lengthened and body proportions have become more like those of adults.

This growth rate is slower than that of infancy and is accompanied by a reduced appetite between the ages of 2 and 6. This change can sometimes be surprising to parents and lead to the development of poor eating habits.

Nutritional Concerns

Caregivers who have established a feeding routine with their child can find this reduction in appetite a bit frustrating and become concerned that the child is going to starve. However, by providing adequate, sound nutrition, and limiting sugary snacks and drinks, the caregiver can be assured that 1) the child will not starve; and 2) the child will receive adequate nutrition. Preschoolers can experience iron deficiencies if not given well-balanced nutrition and if given too much milk. Calcium interferes with the absorption of iron in the diet as well.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, childhood obesity is a serious problem in the United States, putting children and adolescents at risk for poor health. Obesity prevalence among children and adolescents is still too high. For children and adolescents aged 2-19 years in 2017-20201:

The prevalence of obesity was 19.7% and affected about 14.7 million children and adolescents.

Obesity prevalence was 12.7% among 2- to 5-year-olds, 20.7% among 6- to 11-year-olds, and 22.2% among 12- to 19-year-olds. Childhood obesity is also more common among certain populations.

Obesity prevalence was 26.2% among Hispanic children, 24.8% among non-Hispanic Black children, 16.6% among non-Hispanic White children, and 9.0% among non-Hispanic Asian children.

Obesity-related conditions include high blood pressure, high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, breathing problems such as asthma and sleep apnea, and joint problems.

Caregivers need to keep in mind that they are setting up taste preferences at this age. Young children who grow accustomed to high fat, very sweet and salty flavors may have trouble eating foods that have more subtle flavors such as fruits and vegetables. Consider the following advice about establishing eating patterns for years to come (Rice, F.P., 1997). Notice that keeping mealtime pleasant, providing sound nutrition and not engaging in power struggles over food are the main goals:

Tips for Establishing Healthy Eating Patterns

Don’t try to force your child to eat or fight over food. Of course, it is impossible to force someone to eat. But the real advice here is to avoid turning food into some kind of ammunition during a fight. Do not teach your child to eat to or refuse to eat in order to gain favor or express anger toward someone else.

Recognize that appetite varies. Children may eat well at one meal and have no appetite at another. Rather than seeing this as a problem, it may help to realize that appetites do vary. Continue to provide good nutrition, but do not worry excessively if the child does not eat.

Keep it pleasant. This tip is designed to help caregivers create a positive atmosphere during mealtime. Mealtimes should not be the time for arguments or expressing tensions. You do not want the child to have painful memories of mealtimes together or have nervous stomachs and problems eating and digesting food due to stress.

No short order chefs. While it is fine to prepare foods that children enjoy, preparing a different meal for each child or family member sets up an unrealistic expectation from others. Children probably do best when they are hungry and a meal is ready. Limiting snacks rather than allowing children to “graze” continuously can help create an appetite for whatever is being served.

Limit choices. If you give your preschool aged child choices, make sure that you give them one or two specific choices rather than asking “What would you like for lunch?” If given an open choice, children may change their minds or choose whatever their sibling does not choose.

Don’t bribe. Bribing a child to eat vegetable by promising desert is not a good idea. For one reason, the child will likely find a way to get the desert without eating the vegetables (by whining or fidgeting, perhaps, until the caregiver gives in), and for another reason, because it teaches the child that some foods are better than others. Children tend to naturally enjoy a variety of foods until they are taught that some are considered less desirable than others. A child, for example, may learn the broccoli they have enjoyed is seen as yucky by others unless it’s smothered in cheese sauce!

Now, go through the tips again and ask yourself: To what extent do these tips address cultural practices? How might these tips vary by culture?

Brain weight

If you recall, the brain is about 75 percent its adult weight by two years of age. By age 6, it is at 95 percent its adult weight. Myelination and the development of dendrites continues to occur in the cortex and as it does, we see a corresponding change in what the child is capable of doing. Greater development in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain behind the forehead that helps us to think, strategizes, and controls emotion, makes it increasingly possible to control emotional outbursts and to understand how to play games. Consider 4 or 5 year old children and how they might approach a game of soccer. Chances are every move would be a response to the commands of a coach standing nearby calling out, “Run this way! Now, stop. Look at the ball. Kick the ball!” And when the child is not being told what to do, he or she is likely to be looking at the clover on the ground or a dog on the other side of the fence! Understanding the game, thinking ahead, and coordinating movement improve with practice and myelination. Not being too upset over a loss, hopefully, does as well.

Growth in the hemispheres and corpus callosum: Between ages 3 and 6, the left hemisphere of the brain grows dramatically. This side of the brain or hemisphere is typically involved in language skills. The right hemisphere continues to grow throughout early childhood and is involved in tasks that require spatial skills such as recognizing shapes and patterns. The corpus callosum which connects the two hemispheres of the brain undergoes a growth spurt between ages 3 and 6 as well and results in improved coordination between right and left hemisphere tasks. (I once saw a 5 year old hopping on one foot, rubbing his stomach and patting his head all at the same time. I asked him what he was doing and he replied, “My teacher said this would help my corpus callosum!” Apparently, his kindergarten teacher had explained the process!)

Visual Pathways

Have you ever examined the drawings of young children? If you look closely, you can almost see the development of visual pathways reflected in the way these images change as pathways become more mature. Early scribbles and dots illustrate the use of simple motor skills. No real connection is made between an image being visualized and what is created on paper.

At age 3, the child begins to draw wispy creatures with heads and not much other detail. Gradually pictures begin to have more detail and incorporate more parts of the body. Arm buds become arms and faces take on noses, lips and eventually eyelashes. Look for drawings that you or your child has created to see this fascinating trend.

Below are some examples of pictures drawn by children from ages 2 to 7 years:

Motor Skill Development

Early childhood is a time when children are especially attracted to motion and song. Days are filled with moving, jumping, running, swinging and clapping and every place becomes a playground. Even the booth at a restaurant affords the opportunity to slide around in the seat or disappear underneath and imagine being a sea creature in a cave! Of course, this can be frustrating to a caregiver, but it’s the business of early childhood. Children continue to improve their gross motor skills as they run and jump. And frequently ask their caregivers to “look at me” while they hop or roll down a hill. Children’s songs are often accompanied by arm and leg movements or cues to turn around or move from left to right. Fine motor skills are also being refined in activities such as pouring water into a container, drawing, coloring, and using scissors. Some children’s songs promote fine motor skills as well (have you ever heard of the song “itsy, bitsy, spider”?). Mastering the fine art of cutting one’s own fingernails or tying shoes will take a lot of practice and maturation. Motor skills continue to develop in middle childhood-but for preschoolers, play that deliberately involves these skills is emphasized.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions to see examples of gross motor development during early childhood:

Sexual Development in Early Childhood

Historically, children have been thought of as innocent or incapable of sexual arousal (Aries, 1962). Yet, the physical dimension of sexual arousal is present from birth. But to associate the elements of seduction, power, love, or lust that is part of the adult meanings of sexuality would be inappropriate. Sexuality begins in childhood as a response to physical states and sensation and cannot be interpreted as similar to that of adults in any way (Carroll, 2007).

Infancy:

Boys and girls are capable of erections and vaginal lubrication even before birth (Martinson, 1981). Arousal can signal overall physical contentment and stimulation that accompanies feeding or warmth. And infants begin to explore their bodies and touch their genitals as soon as they have the sufficient motor skills. This stimulation is for comfort or to relieve tension rather than to reach orgasm (Carroll, 2007).

Early Childhood:

Self-stimulation is common in early childhood for both boys and girls. Curiosity about the body and about others’ bodies is a natural part of early childhood as well. Consider this example. A mother is asked by her young daughter: “So it’s okay to see a boy’s privates as long as it’s the boy’s mother or a doctor?” The mother hesitates a bit and then responds, “Yes. I think that’s alright.” “Hmmm,” the girl begins, “When I grow up, I want to be a doctor!” Hopefully, this subject is approached in a way that teaches children to be safe and know what is appropriate without frightening them or causing shame.

As children grow, they are more likely to show their genitals to siblings or peers, and to take off their clothes and touch each other (Okami et al., 1997). Masturbation is common for both boys and girls. Boys are often shown by other boys how to masturbate. But girls tend to find out accidentally. And boys masturbate more often and touch themselves more openly than do girls (Schwartz, 1999).

Hopefully, parents respond to this without undue alarm and without making the child feel guilty about their bodies. Instead, messages about what is going on and the appropriate time and place for such activities help the child learn what is appropriate.

Parents should take the time to speak with their children about when it is appropriate for other people to see or touch them. Many experts suggest that this should occur as early as age 3, and of course the discussion should be appropriate for the child’s age. One way to help a young child understand inappropriate touching is to discuss “bathing suit areas.” Kids First, Inc. suggests discussing the following: “No one should touch you anywhere your bathing suit covers. No one should ask you to touch them somewhere that their bathing suit covers. No one should show you a part of their or someone else’s bodies that their bathing suit covers.” Further, instead of talking about good or bad touching, talk about safe and unsafe touching. This way children will not feel guilty later on when that sort of touching is appropriate in a relationship.

Early Childhood Cognition or “Thinking” Development

Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development. Piaget’s Second Stage: The Preoperational Stage:

Remember that Piaget believed that we are continuously trying to maintain balance in how we understand the world. With rapid increases in motor skill and language development, young children are constantly encountering new experiences, objects, and words. In the module covering main developmental theories, you learned that when faced with something new, a child may either assimilate it into an existing schema by matching it with something they already know or expand their knowledge structure to accommodate the new situation. During the preoperational stage, many of the child’s existing schemas will be challenged, expanded, and rearranged. Their whole view of the world may shift.

Piaget’s second stage of cognitive development is called the preoperational stage and coincides with ages 2-7 (following the sensorimotor stage). The word operation refers to the use of logical rules, so sometimes this stage is misinterpreted as implying that children are illogical. While it is true that children at the beginning of the preoperational stage tend to answer questions intuitively as opposed to logically, children in this stage are learning to use language and how to think about the world symbolically. These skills help children develop the foundations they will need to consistently use operations in the next stage. Let’s examine some of Piaget’s assertions about children’s cognitive abilities at this age.

Pretend Play

Pretending is a favorite activity at this time. For a child in the preoperational stage, a toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land!

Piaget believed that children’s pretend play and experimentation helped them solidify the new schemas they were developing cognitively. This involves both assimilation and accommodation, which results in changes in their conceptions or thoughts. As children progress through the preoperational stage, they are developing the knowledge they will need to begin to use logical operations in the next stage.

Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children to think that everyone sees things in the same way as the child. Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a three-dimensional model of a mountain and asking them to describe what a doll that is looking at the mountain from a different angle might see. Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own, rather than the doll’s view. However, when children are speaking to others, they tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. Consider why this difference might be observed. Do you think this indicates some awareness of the views of others? Or do you think they are simply modeling adult speech patterns?

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions to see an example of egocentrism. The boy in this interview displays egocentrism by believing that the researcher sees the same thing as he does, even after switching positions.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions to see older children engaging in the same task, and having the ability to look at the mountain from different viewpoints. They no longer make the cognitive error of egocentrism.

Precausal Thinking

Similar to preoperational children’s egocentric thinking is their structuring of cause-and-effect relationships based on their limited view of the world. Piaget coined the term “precausal thinking” to describe the way in which preoperational children use their own existing ideas or views, like in egocentrism, to explain cause-and-effect relationships. Three main concepts of causality, as displayed by children in the preoperational stage, include animism, artificialism, and transductive reasoning.

Animism is the belief that inanimate objects are capable of actions and have lifelike qualities. An example could be a child believing that the sidewalk was mad and made them fall down, or that the stars twinkle in the sky because they are happy. To an imaginative child, the cup may be alive, the chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive, but after age three, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007). Many children’s stories and movies capitalize on animistic thinking. Do you remember some of the classic stories that make use of the idea of objects being alive and engaging in lifelike actions?

Artificialism refers to the belief that environmental characteristics can be attributed to human actions or interventions. For example, a child might say that it is windy outside because someone is blowing very hard, or the clouds are white because someone painted them that color.

Finally, precausal thinking is categorized by transductive reasoning. Transductive reasoning is when a child fails to understand the true relationships between cause and effect. Unlike deductive or inductive reasoning (general to specific, or specific to general), transductive reasoning refers to when a child reasons from specific to specific, drawing a relationship between two separate events that are otherwise unrelated. For example, if a child hears a dog bark and then a balloon pop, the child would conclude that because the dog barked, the balloon popped. Related to this is syncretism, which refers to a tendency to think that if two events occur simultaneously, one caused the other. An example of this might be a child asking the question, “if I put on my bathing suit will it turn to summer?”

Cognition Errors

Between about the ages of four and seven, children tend to become very curious and ask many questions, beginning the use of primitive reasoning. There is an increase in curiosity in the interest of reasoning and wanting to know why things are the way they are. Piaget called it the “intuitive substage” because children realize they have a vast amount of knowledge, but they are unaware of how they acquired it.

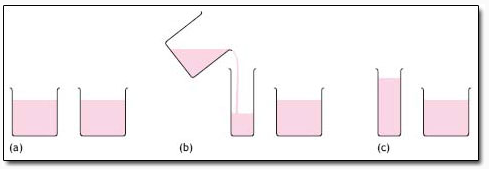

Centration and conservation are characteristic of preoperative thought. Centration is the act of focusing all attention on one characteristic or dimension of a situation while disregarding all others. An example of centration is a child focusing on the number of pieces of cake that each person has, regardless of the size of the pieces. Centration is one of the reasons that young children have difficulty understanding the concept of conservation. Conservation is the awareness that altering a substance’s appearance does not change its basic properties. Children at this stage are unaware of conservation and exhibit centration. Imagine a 2-year-old and 4-year-old eating lunch. The 4-year-old has a whole peanut butter and jelly sandwich. He notices, however, that his younger sister’s sandwich is cut in half and protests, “She has more!” He is exhibiting centration by focusing on the number of pieces, which results in a conservation error.

In Piaget’s famous conservation task, a child is presented with two identical beakers containing the same amount of liquid. The child usually notes that the beakers do contain the same amount of liquid. When one of the beakers is poured into a taller and thinner container, children who are younger than seven or eight years old typically say that the two beakers no longer contain the same amount of liquid, and that the taller container holds the larger quantity (centration), without taking into consideration the fact that both beakers were previously noted to contain the same amount of liquid.

Irreversibility is also demonstrated during this stage and is closely related to the ideas of centration and conservation. Irreversibility refers to the young child’s difficulty mentally reversing a sequence of events. In the same beaker situation, the child does not realize that, if the sequence of events was reversed and the water from the tall beaker was poured back into its original beaker, then the same amount of water would exist.

Centration, conservation errors, and irreversibility are indications that young children are reliant on visual representations. Another example of children’s reliance on visual representations is their misunderstanding of “less than” or “more than”. When two rows containing equal amounts of blocks are placed in front of a child with one row spread farther apart than the other, the child will think that the row spread farther contains more blocks.

WATCH THIS video clip below or online with captions demonstrate irreversibility and showing how younger children struggle with the concept of conservation:

Class inclusion refers to a kind of conceptual thinking that children in the preoperational stage cannot yet grasp. Children’s inability to focus on two aspects of a situation at once (centration) inhibits them from understanding the principle that one category or class can contain several different subcategories or classes. Preoperational children also have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way. For example, a four-year-old girl may be shown a picture of eight dogs and three cats. The girl knows what cats and dogs are, and she is aware that they are both animals. However, when asked, “Are there more dogs or more animals?” she is likely to answer “more dogs.” This is due to her difficulty focusing on the two subclasses and the larger class all at the same time. She may have been able to view the dogs as dogs or animals, but struggled when trying to classify them as both, simultaneously. Similar to this is a concept relating to intuitive thought, known as “transitive inference.”

Transitive inference is using previous knowledge to determine the missing piece, using basic logic. Children in the preoperational stage lack this logic. An example of transitive inference would be when a child is presented with the information “A” is greater than “B” and “B” is greater than “C.” The young child may have difficulty understanding that “A” is also greater than “C.”

As the child’s vocabulary improves and more schemes are developed, they are more able to think logically, demonstrate an understanding of conservation, and classify objects.

Was Piaget Right?

It certainly seems that children in the preoperational stage make the mistakes in logic that Piaget suggests that they will make. That said, it is important to remember that there is variability in terms of the ages at which children reach and exit each stage. Further, there is some evidence that children can be taught to think in more logical ways far before the end of the preoperational period. For example, as soon as a child can reliably count they may be able to learn conservation of number. For many children, this is around age five. More complex conservation tasks, however, may not be mastered until closer to the end of the stage around age seven.

Theory of Mind

How do we come to understand how our mind works? The theory of mind is the understanding that the mind holds people’s beliefs, desires, emotions, and intentions. One component of this is understanding that the mind can be tricked or that the mind is not always accurate.

A two-year-old child does not understand very much about how their mind works. They can learn by imitating others, they are starting to understand that people do not always agree on things they like, and they have a rudimentary understanding of cause and effect (although they often fall prey to transitive reasoning). By the time a child is four, their theory of the mind allows them to understand that people think differently, have different preferences, and even mask their true feelings by putting on a different face that differs from how they truly feel inside.

To think about what this might look like in the real world, imagine showing a three-year-old child a bandaid box and asking the child what is in the box. Chances are, the child will reply, “bandaids.” Now imagine that you open the box and pour out crayons. If you now ask the child what they thought was in the box before it was opened, they may respond, “crayons.” If you ask what a friend would have thought was in the box, the response would still be “crayons.” Why?

Before about four years of age, a child does not recognize that the mind can hold ideas that are not accurate, so this three-year-old changes their response once shown that the box contains crayons. The child’s response can also be explained in terms of egocentrism and irreversibility. The child’s response is based on their current view rather than seeing the situation from another person’s perspective (egocentrism) or thinking about how they arrived at their conclusion (irreversibility). At around age four, the child would likely reply, “bandaids” when asked after seeing the crayons because by this age a child is beginning to understand that thoughts and realities do not always match.

WATCH THIS video clip below or online with captions showing researchers demonstrate several versions of the false belief test to assess the theory of mind in young children:

Theory of Mind and Social Intelligence

This awareness of the existence of mind is part of social intelligence and the ability to recognize that others can think differently about situations. It helps us to be self-conscious or aware that others can think of us in different ways, and it helps us to be able to be understanding or empathic toward others. This developing social intelligence helps us to anticipate and predict the actions of others (even though these predictions are sometimes inaccurate). The awareness of the mental states of others is important for communication and social skills. A child who demonstrates this skill is able to anticipate the needs of others.

Impaired Theory of Mind in Individuals with Autism

People with autism or an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) typically show an impaired ability to recognize other people’s minds. Under the DSM-5, autism is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction across multiple contexts, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These deficits are present in early childhood, typically before age three, and lead to clinically significant functional impairment. Symptoms may include lack of social or emotional reciprocity, stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language, and persistent preoccupation with unusual objects.

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child’s unusual behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months, but often a diagnoses comes later, and individual cases vary significantly. Typical early signs of autism include:

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word (spontaneous, not just echolalic) phrases by 24 months.

- Loss of any language or social skills, at any age.

Children with ASD experience difficulties with explaining and predicting other people’s behavior, which leads to problems in social communication and interaction. Children who are diagnosed with an autistic spectrum disorder usually develop the theory of mind more slowly than other children and continue to have difficulties with it throughout their lives.

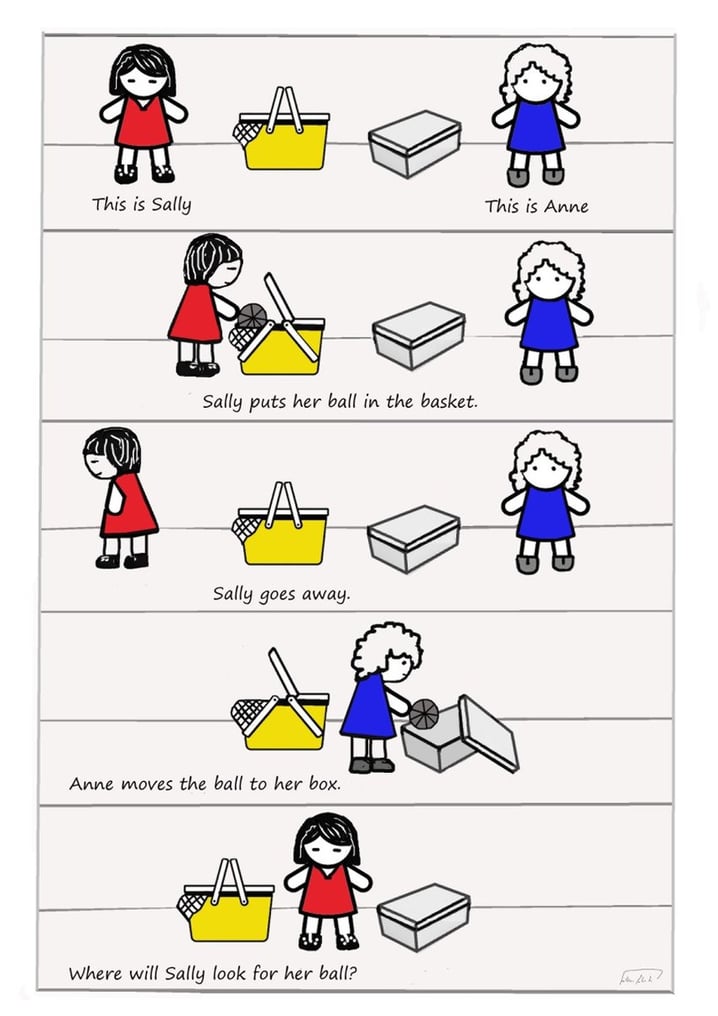

For testing whether someone lacks the theory of mind, the Sally-Anne test is performed. The child sees the following story: Sally and Anne are playing. Sally puts her ball into a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is gone, Anne moves the ball from the basket to the box. Now Sally returns. The question is: where will Sally look for her ball? The test is passed if the child correctly assumes that Sally will look in the basket. The test is failed if the child thinks that Sally will look in the box. Children younger than four and older children with autism will generally say that Sally will look in the box.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions to see the Sally-Anne test in action:

Language Development in Early Childhood

A child’s vocabulary expands between the ages of two to six from about 200 words to over 10,000 words through a process called fast-mapping. Words are easily learned by making connections between new words and concepts already known. The parts of speech that are learned depend on the language and what is emphasized. Children speaking verb-friendly languages such as Chinese and Japanese tend to learn verbs more readily, but those learning less verb-friendly languages such as English seem to need assistance in grammar to master the use of verbs. Children are also very creative in creating their own words to use as labels such as a “take-care-of” when referring to John, the character on the cartoon Garfield, who takes care of the cat.

Children can repeat words and phrases after having heard them only once or twice, but they do not always understand the meaning of the words or phrases. This is especially true of expressions or figures of speech which are taken literally. For example, two preschool-aged girls began to laugh loudly while listening to a tape-recording of Disney’s “Sleeping Beauty” when the narrator reports, “Prince Phillip lost his head!” They imagine his head popping off and rolling down the hill as he runs and searches for it. Or a classroom full of preschoolers hears the teacher say, “Wow! That was a piece of cake!” The children began asking “Cake? Where is my cake? I want cake!”

Overregularization

Children learn the rules of grammar as they learn the language. Some of these rules are not taught explicitly, and others are. Often when learning language intuitively children apply rules inappropriately at first. But even after successfully navigating the rule for a while, at times, explicitly teaching a child a grammar rule may cause them to make mistakes they had previously not been making. For instance, two- to three-year-old children may say “I goed there” or “I doed that” as they understand intuitively that adding “ed” to a word makes it mean “something I did in the past.” As the child hears the correct grammar rule applied by the people around them, they correctly begin to say “I went there” and “I did that.” It would seem that the child has solidly learned the grammar rule, but it is actually common for the developing child to revert back to their original mistake. This happens as they overregulate the rule. This can happen because they intuitively discover the rule and overgeneralize it or because they are explicitly taught to add “ed” to the end of a word to indicate past tense in school. A child who had previously produced correct sentences may start to form incorrect sentences such as, “I goed there. I doed that.” These children are able to quickly re-learn the correct exceptions to the -ed rule.

Vygotsky and Language Development

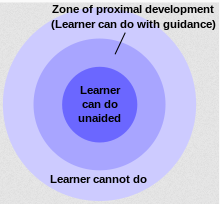

Lev Vygotsky hypothesized that children had a zone of proximal development (ZPD). The ZPD is the range of material that a child is ready to learn if proper support and guidance are given from either a peer who understands the material or by an adult. We can see the benefit of this sort of guidance when we think about the acquisition of language. Children can be assisted in learning language by others who listen attentively, model more accurate pronunciations and encourage elaboration. For example, if the child exclaims, “I’m goed there!” then the adult responds, “You went there?”

Children may be hard-wired for language development, as Noam Chomsky suggested in his theory of universal grammar, but active participation is also important for language development. The process of scaffolding is one in which the guide provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned. Repeating what a child has said, but in a grammatically correct way, is scaffolding for a child who is struggling with the rules of language production.

Private Speech

Do you ever talk to yourself? Why? Chances are, this occurs when you are struggling with a problem, trying to remember something or feel very emotional about a situation. Children talk to themselves too. Piaget interpreted this as egocentric speech or a practice engaged in because of a child’s inability to see things from other points of view. Vygotsky, however, believed that children talk to themselves in order to solve problems or clarify thoughts. As children learn to think in words, they do so aloud before eventually closing their lips and engaging in private speech or inner speech. Thinking out loud eventually becomes thought accompanied by internal speech, and talking to oneself becomes a practice only engaged in when we are trying to learn something or remember something, etc.

Vygotsky and Education

Vygotsky’s theories do not just apply to language development but have been extremely influential for education in general. Although Vygotsky himself never mentioned the term scaffolding, it is often credited to him as a continuation of his ideas pertaining to the way adults or other children can use guidance in order for a child to work within their ZPD. (The term scaffolding was first developed by Jerome Bruner, David Wood, and Gail Ross while applying Vygotsky’s concept of ZPD to various educational contexts.)

Educators often apply these concepts by assigning tasks that students cannot do on their own, but which they can do with assistance; they should provide just enough assistance so that students learn to complete the tasks independently and then provide an environment that enables students to do harder tasks than would otherwise be possible. Teachers can also allow students with more knowledge to assist students who need more guidance.

Especially in the context of collaborative learning, group members who have higher levels of understanding can help the less advanced members learn within their zone of proximal development.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions showing how Vygotsky’s theory applies to learning in early childhood:

30 Million Word Gap

To accomplish the tremendous rate of word learning that needs to occur during early childhood, it is important that children are learning new words each day. Research by Betty Hart and Todd Risley in the late 1990s and early 2000s indicated that children from less advantaged backgrounds are exposed to millions of fewer words in their first three years of life than children who come from more privileged socioeconomic backgrounds. In their research, families were classified by socioeconomic status, (SES) into “high” (professional), “middle” (working class), and “low” (welfare) SES. They found that the average child in a professional family hears 2,153 words per waking hour, the average child in a working-class family hears 1,251 words per hour, and an average child in a welfare family only 616 words per hour. Extrapolating, they stated that, “in four years, an average child in a professional family would accumulate experience with almost 45 million words, an average child in a working-class family 26 million words, and an average child in a welfare family 13 million words.” The line of thinking following their study is that children from more affluent households would enter school knowing more words, which would give them advantage in school.

Hart and Risley’s research has been criticized by scholars. Critics theorize that the language and achievement gaps are not a result of the number of words a child is exposed to, but rather alternative theories suggest it could reflect the disconnect of linguistic practices between home and school. Thus, judging academic success and linguistic capabilities from socioeconomic status may ignore bigger societal issues. A recent replication of Hart and Risley’s study with more participants has found that the “word gap” may be closer to 4 million words, not the oft-cited 30 million words previously proposed. The ongoing word gap research is evidence of the importance of language development in early childhood.

READ THIS article to learn more about common linguistic mistakes that children make and what they mean: 10 Language Mistakes Kids Make That Are Actually Pretty Smart

Social and Emotional Development

Developing a Concept of Self

Early childhood is a time of forming an initial sense of self. A self-concept or idea of who we are, what we are capable of doing, and how we think and feel is a social process that involves taking into consideration how others view us. It might be said, then, that in order to develop a sense of self, you must interact with others.

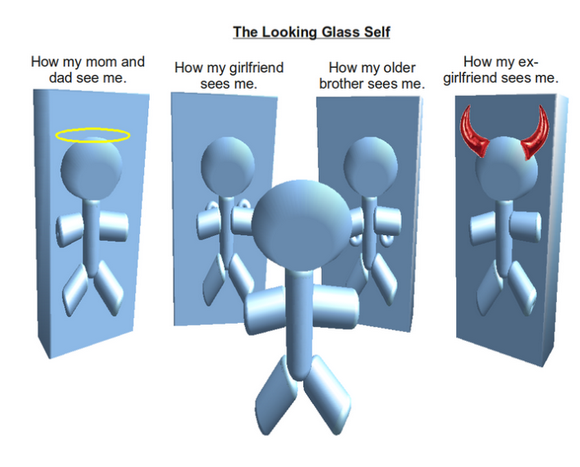

Cooley’s Looking-Glass Self

Charles Horton Cooley (1964) suggested that our self-concept comes from looking at how others respond to us. This process, known as the looking-glass self involves looking at how others seem to view us and interpreting this as we make judgments about whether we are good or bad, strong or weak, beautiful or ugly, and so on. Of course, we do not always interpret their responses accurately so our self-concept is not simply a mirror reflection of the views of others. After forming an initial self-concept, we may use our existing self-concept as a mental filter screening out those responses that do not seem to fit our ideas of who we are. So compliments may be negated, for example.

Think of times in your life when you felt more self-conscious. The process of the looking-glass self is pronounced when we are preschoolers. Later in life, we also experience this process when we are in a new school, new job, or are taking on a new role in our personal lives and are trying to gauge our own performance. When we feel more sure of who we are we focus less on how we appear to others.

WATCH THIS Khan Academy video below or online with captions to learn more about Charles Cooley’s looking-glass self.:

Mead’s I and Me

George Herbert Mead (1967) offered an explanation of how we develop a social sense of self by being able to see ourselves through the eyes of others. There are two parts of the self: the “I” which is the part of the self that is spontaneous, creative, innate, and is not concerned with how others view us and the “me” or the social definition of who we are.

When we are born, we are all “I” and act without concern about how others view us. But the socialized self begins when we are able to consider how one important person views us. This initial stage is called “taking the role of the significant other.” For example, a child may pull a cat’s tail and be told by his mother, “No! Don’t do that, that’s bad” while receiving a slight slap on the hand. Later, the child may mimic the same behavior toward the self and say aloud, “No, that’s bad” while patting his own hand. What has happened? The child is able to see himself through the eyes of the mother. As the child grows and is exposed to many situations and rules of culture, he begins to view the self in the eyes of many others through these cultural norms or rules. This is referred to as “taking the role of the generalized other” and results in a sense of self with many dimensions. The child comes to have a sense of self as a student, as a friend, as a son, and so on.

WATCH THIS video below or online explaining Mead’s understanding of the “I” and the “me,” and comparing it to other concepts you’ve already learned about, like egocentrism:

Exaggerated Sense of Self

One of the ways to gain a clearer sense of self is to exaggerate those qualities that are to be incorporated into the self. Preschoolers often like to exaggerate their own qualities or to seek validation as the biggest or smartest or child who can jump the highest. Much of this may be due to the simple fact that the child does not understand their own limits. Young children may really believe that they can beat their parent to the mailbox, or pick up the refrigerator.

This exaggeration tends to be replaced by a more realistic sense of self in middle childhood as children realize that they do have limitations. Part of this process includes having parents who allow children to explore their capabilities and give the child authentic feedback. Another important part of this process involves the child learning that other people have capabilities, too…and that the child’s capabilities may differ from those of other people. Children learn to compare themselves to others to understand what they are “good at” and what they are not as good at.

Self-Control

One important aspect of self-concept is how we understand our ability to exhibit self-control and delay gratification. Self-control involves both response inhibition and delayed gratification. Response inhibition involves the ability to recognize a potential behavior before it occurs and stop the initiation of behaviors that could result in undesired consequences. Delayed gratification refers to the process of forgoing immediate or short-term rewards to achieve more valuable goals in the longer term. The ability to delay gratification was traditionally assessed in young children with the “Marshmallow Test.” During this experiment, participants were presented with a marshmallow (or another small treat) and were given a choice to eat it or wait for a certain period of time without eating it, so that they could have two marshmallows eventually (Mischel et al., 2011).

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions of The Marshmallow Test footage:

What does the Marshmallow Test Really Test?

READ THIS: Culture and The Marshmallow Test: Debunked? Read the Article Titled, “A new take on the ‘marshmallow test’: When it comes to resisting temptation, a child’s cultural upbringing matters.”

While self-control takes many years to develop, we see the beginnings of this skill during early childhood. This ability to delay gratification in young children has been shown to predict many positive outcomes. For instance, preschoolers who were able to delay gratification for a longer period of time had higher levels of resilience, better academic and social competence, and greater planning ability in their adolescence (Mischel et al., 1988). Recent research has linked poor delayed gratification in young children to poor eating self-regulation, specifically regarding eating when not hungry (Hughes et al., 2015) and behavioral problems (Willoughby et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2012).[1].

Learning and Behavior Modification

Parenting and Behaviorism: Parenting generally involves many opportunities to apply principles of behaviorism, especially operant conditioning. In discussing operant conditioning, we use several everyday words—positive, negative, reinforcement, and punishment—in a specialized manner. In operant conditioning, positive and negative do not mean good and bad. Instead, positive means you are adding something, and negative means you are taking something away. Reinforcement means you are increasing a behavior, and punishment means you are decreasing a behavior. Reinforcement can be positive or negative, and punishment can also be positive or negative. All reinforcers (positive or negative) increase the likelihood of a behavioral response. All punishers (positive or negative) decrease the likelihood of a behavioral response. Now let’s combine these four terms: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. (See table below.)

Positive and Negative Reinforcement and Punishment |

||

|

|

Reinforcement |

Punishment |

|

Positive |

Something is added to increase the likelihood of a behavior. |

Something is added to decrease the likelihood of a behavior. |

|

Negative |

Something is removed to increase the likelihood of a behavior. |

Something is removed to decrease the likelihood of a behavior. |

The most effective way to teach a person or animal a new behavior is with positive reinforcement. In positive reinforcement, a stimulus is added to the situation to increase a behavior. Parents and teachers use positive reinforcement all the time, from offering dessert after dinner, praising children for cleaning their room or completing some work, offering a toy at the end of a successful piano recital, or earning more time for recess. The goal of providing these forms of positive reinforcement is to increase the likelihood of the same behavior occurring in the future.

Positive reinforcement is an extremely effective learning tool, as evidenced by nearly 80 years worth of research. That said, there are many ways to introduce positive reinforcement into a situation. Many people believe that reinforcers must be tangible, but research shows that verbal praise and hugs are very effective reinforcers for people of all ages. Further, research suggests that constantly providing tangible reinforcers may actually be counterproductive in certain situations. For example, paying children for their grades may undermine their intrinsic motivation to go to school and do well. While children who are paid for their grades may maintain good grades, it is to receive the reinforcing pay, not because they have an intrinsic desire to do well. Therefore, we must provide appropriate reinforcement, and be careful to ensure that the reinforcement does not undermine intrinsic motivation.

In negative reinforcement, an aversive stimulus is removed to increase a behavior. For example, car manufacturers use the principles of negative reinforcement in their seatbelt systems, which go “beep, beep, beep” until you fasten your seatbelt. The annoying sound stops when you exhibit the desired behavior, increasing the likelihood that you will buckle up in the future. Negative reinforcement is also used frequently in horse training. Riders apply pressure—by pulling the reins or squeezing their legs—and then remove the pressure when the horse performs the desired behavior, such as turning or speeding up. The pressure is the negative stimulus that the horse wants to remove.

Sometimes, adding something to the situation is reinforcing as in the cases we described above with cookies, praise, and money. Positive reinforcement involves adding something to the situation in order to encourage a behavior. Other times, taking something away from a situation can be reinforcing. For example, the loud, annoying buzzer on your alarm clock encourages you to get up so that you can turn it off and get rid of the noise. Children whine in order to get their parents to do something and often, parents give in just to stop the whining. In these instances, children have used negative reinforcement to get what they want.

Operant conditioning tends to work best if you focus on trying to encourage a behavior or move a person into the direction you want them to go rather than telling them what not to do. Reinforcers are used to encourage behavior; punishers are used to stop the behavior. A punisher is anything that follows an act and decreases the chance it will reoccur. As with reinforcement, there are also two types of punishment: positive punishment and negative punishment.

Positive punishment involves adding something in order to decrease the likelihood that a behavior will occur again in the future. Spanking is an example of positive punishment. Receiving a speeding ticket is also an example of positive punishment. Both of these punishers, the spanking and the speeding ticket, are intended to decrease the reoccurrence of the related behavior.

Negative punishment involves removing something that is desired in order to decrease the likelihood that a behavior will occur again in the future. Putting a child in time out can serve as a negative punishment if the child enjoys social interaction. Taking away a child’s technology privileges can also be a negative punishment. Taking away something that is desired encourages the child to refrain from engaging in that behavior again in order to not lose the desired object or activity.

Often, punished behavior doesn’t really go away. It is just suppressed and may reoccur whenever the threat of punishment is removed. For example, a child may not cuss around you because you’ve washed his mouth out with soap, but he may cuss around his friends. A motorist may only slow down when the trooper is on the side of the freeway. Another problem with punishment is that when a person focuses on punishment, they may find it hard to see what the other does right or well. Punishment is stigmatizing; when punished, some people start to see themselves as bad and give up trying to change.

Reinforcement can occur in a predictable way, such as after every desired action is performed (called continuous reinforcement), or intermittently, after the behavior is performed a number of times or the first time it is performed after a certain amount of time (called partial reinforcement whether based on the number of times or the passage of time). The schedule of reinforcement has an impact on how long a behavior continues after reinforcement is discontinued. So, a parent who has rewarded a child’s actions each time may find that the child gives up very quickly if a reward is not immediately forthcoming. Children will learn quickest under a continuous schedule of reinforcement. Then the parent should switch to a schedule of partial reinforcement to maintain the behavior.

WATCH THIS video below or online providing some tips for using operant conditioning in parenting:

Conceptualizations of Gender and Early Childhood Development

Children learn at a young age that there are distinct expectations for boys and girls. Cross-cultural studies reveal that children are aware of gender roles by age two or three. At four or five, most children are firmly entrenched in culturally appropriate gender roles (Kane 1996). Children acquire these roles through socialization, a process in which people learn to behave in a particular way as dictated by societal values, beliefs, and attitudes.

Another important dimension of the self is the sense of self as male or female. Preschool aged children become increasingly interested in finding out the differences between boys and girls both physically and in terms of what activities are acceptable for each. While two-year-olds can identify some differences and learn whether they are boys or girls, preschoolers become more interested in what it means to be male or female. This self-identification, or gender identity, is followed sometime later with gender constancy, or the understanding that superficial changes do not mean that gender has actually changed. For example, if you are playing with a two-year-old boy and put barrettes in his hair, he may protest saying that he doesn’t want to be a girl. By the time a child is four-years-old, they have a solid understanding that putting barrettes in their hair does not change their gender.

Children may also use gender stereotyping readily. Gender stereotyping involves overgeneralizing about the attitudes, traits, or behavior patterns of women or men. A recent research study examined four- and five-year-old children’s predictions concerning the sex of the persons carrying out a variety of common activities and occupations on television. The children’s responses revealed strong gender-stereotyped expectations. They also found that children’s estimates of their own future competence indicated stereotypical beliefs, with the females more likely to reject masculine activities.

Children who are allowed to explore different toys, who are exposed to non-traditional gender roles, and whose parents and caregivers are open to allowing the child to take part in non-traditional play (allowing a boy to nurture a doll, or allowing a girl to play doctor) tend to have broader definitions of what is gender appropriate, and may do less gender stereotyping.

WATCH THIS clip below or online from Upworthy showing how some children were surprised to meet women in traditionally male occupations:

Learning Through Reinforcement and Modeling

Learning theorists suggest that gender role socialization is a result of the ways in which parents, teachers, friends, schools, religious institutions, media, and others send messages about what is acceptable or desirable behavior for males or females. This socialization begins early—in fact, it may even begin the moment a parent learns that a child is on the way. Knowing the sex of the child can conjure up images of the child’s behavior, appearance, and potential on the part of a parent. And this stereotyping continues to guide perception through life. Consider parents of newborns. Shown a 7-pound, 20-inch baby, wrapped in blue (a color designating males) describe the child as tough, strong, and angry when crying. Shown the same infant in pink (a color used in the United States for baby girls), these parents are likely to describe the baby as pretty, delicate, and frustrated when crying. Female infants are held and talked to more frequently, given direct eye contact. Male infants’ play is often mediated through a toy or activity.

One way children learn gender roles is through play. Parents typically supply boys with trucks, toy guns, and superhero paraphernalia, which are active toys that promote motor skills, aggression, and solitary play. Daughters are often given dolls and dress-up apparel that foster nurturing, social proximity, and role play. Studies have shown that children will most likely choose to play with “gender appropriate” toys (or same-gender toys) even when cross-gender toys are available because parents give children positive feedback (in the form of praise, involvement, and physical closeness) for gender normative behavior. Sons are given tasks that take them outside the house and that have to be performed only on occasion, while girls are more likely to be given chores inside the home, such as cleaning or cooking, that are performed daily. Sons are encouraged to think for themselves when they encounter problems, and daughters are more likely to be given assistance even when they are working on an answer. This impatience is reflected in teachers waiting less time when asking a female student for an answer than when asking for a reply from a male student. Girls are given the message from teachers that they must try harder and endure in order to succeed while boys successes are attributed to their intelligence. Of course, the stereotypes of advisors can also influence which kinds of courses or vocational choices girls and boys are encouraged to make.

Friends discuss what is acceptable for boys and girls, and popularity may be based on modeling what is considered ideal behavior or appearance for the sexes. Girls tend to tell one another secrets to validate others as best friends, while boys compete for position by emphasizing their knowledge, strength or accomplishments. This focus on accomplishments can even give rise to exaggerating accomplishments in boys, but girls are discouraged from showing off and may learn to minimize their accomplishments as a result.

Gender messages abound in our environment. But does this mean that each of us receives and interprets these messages in the same way? Probably not. In addition to being recipients of these cultural expectations, we are individuals who also modify these roles (Kimmel, 2008).

One interesting recent finding is that girls may have an easier time breaking gender norms than boys.[1] Girls who play with masculine toys often do not face the same ridicule from adults or peers that boys face when they want to play with feminine toys. Girls also face less ridicule when playing a masculine role (like doctor) as opposed to a boy who wants to take a feminine role (like caregiver).

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions providing an overview of common toy commercials and how they can be analyzed based on recent research on gender stereotypes. What gender roles or gender stereotypes have you noticed in toy commercials? How do you think toy commercials have changed over the past few years?

DIG DEEPER: GENDER IDENTITY DEVELOPMENTThe National Center on Parent, Family, and Community Engagement identified several stages of gender identity development, as outlined below. You can see more of their resources and tips for healthy gender development by reading Healthy Gender Development and Young Children. |

|

Infancy. Children observe messages about gender from adults’ appearances, activities, and behaviors. Most parents’ interactions with their infants are shaped by the child’s gender, and this in turn also shapes the child’s understanding of gender (Fagot & Leinbach, 1989; Witt, 1997; Zosuls, Miller, Ruble, Martin, & Fabes, 2011). 18–24 months. Toddlers begin to define gender, using messages from many sources. As they develop a sense of self, toddlers look for patterns in their homes and early care settings. Gender is one way to understand group belonging, which is important for secure development (Kuhn, Nash & Brucken, 1978; Langlois & Downs, 1980; Fagot & Leinbach, 1989; Baldwin & Moses, 1996; Witt, 1997; Antill, Cunningham, & Cotton, 2003; Zoslus, et al., 2009). Ages 3–4. Gender identity takes on more meaning as children begin to focus on all kinds of differences. Children begin to connect the concept “girl” or “boy” to specific attributes. They form stronger rules or expectations for how each gender behaves and looks (Kuhn, Nash, & Brucken 1978; Martin, Ruble, & Szkrybalo, 2004; Halim & Ruble, 2010). Ages 5–6. At these ages, children’s thinking may be rigid in many ways. For example, 5- and 6-year-olds are very aware of rules and of the pressure to comply with them. They do so rigidly because they are not yet developmentally ready to think more deeply about the beliefs and values that many rules are based on. For example, as early educators and parents know, the use of “white lies” is still hard for them to understand. Researchers call these ages the most “rigid” period of gender identity (Weinraub et al., 1984; Egan, Perry, & Dannemiller, 2001; Miller, Lurye, Zosuls, & Ruble, 2009). A child who wants to do or wear things that are not typical of his gender is probably aware that other children find it strange. The persistence of these choices, despite the negative reactions of others, show that these are strong feelings. Gender rigidity typically declines as children age (Trautner et al., 2005; Halim, Ruble, Tamis-LeMonda, & Shrout, 2013). With this change, children develop stronger moral impulses about what is “fair” for themselves and other children (Killen & Stangor, 2001). It is important to understand these typical and normal attempts for children to understand the world around them. It is helpful to encourage children and support them as individuals, instead of emphasizing or playing into gender roles and expectations. You can foster self-esteem in children of any gender by giving all children positive feedback about their unique skills and qualities. For example, you might say to a child, “I noticed how kind you were to your friend when she fell down” or “You were very helpful with clean-up today—you are such a great helper” or “You were such a strong runner on the playground today. |

The Impact of Gender Discrimination

How much does gender matter? In the United States, gender differences are found in school experiences. Even into college and professional school, girls are likely to be perceived as less vocal in class and much more at risk for sexual harassment from teachers, coaches, classmates, and professors. These gender differences are also found in social interactions and in media messages. The stereotypes that boys should be strong, forceful, active, dominant, and rational, and that girls should be pretty, subordinate, unintelligent, emotional, and talkative are portrayed in children’s toys, books, commercials, video games, movies, television shows, and music. In adulthood, these differences are reflected in income gaps between men and women (women working full-time earn about 74 percent of the income of men), in higher rates of women suffering rape and domestic violence, higher rates of eating disorders for females, and in higher rates of violent death for men in young adulthood.

Gender differences in India can be a matter of life and death as preferences for male children have been historically strong and are still held, especially in rural areas (WHO, 2010). Male children are given preference for receiving food, breast milk, medical care, and other resources. In some countries, it is no longer legal to give parents information on the sex of their developing child for fear that they will abort a female fetus. Clearly, gender socialization and discrimination still impact development in a variety of ways across the globe. Gender discrimination generally persists throughout the lifespan in the form of obstacles to education, or lack of access to political, financial, and social power.

Gender and Health Care: Gender Affirming Care

Gender affirming care, often referred to as gender-affirming therapy or gender-affirming healthcare, is a vital aspect of medical support and psychological assistance provided to individuals whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. This form of care encompasses a range of services designed to affirm and support an individual’s gender identity, ensuring their physical, mental, and emotional well-being. In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of gender affirming care within the medical and mental health communities, as well as within society at large.

At its core, gender affirming care acknowledges and respects an individual’s self-identified gender, affirming their authentic identity rather than attempting to change or suppress it. This approach is rooted in principles of respect, dignity, and autonomy, recognizing each person’s right to define and express their gender in a way that feels true to them. Gender affirming care aims to alleviate gender dysphoria, the distress experienced by individuals whose gender identity does not align with societal expectations or their assigned sex at birth. By providing affirming and supportive care, individuals can experience improved mental health outcomes, enhanced self-esteem, and a greater sense of well-being.

The field of gender affirming care encompasses various interventions and services tailored to meet the unique needs of each individual. These may include medical interventions such as hormone therapy, surgical procedures, and other forms of medical transition, as well as non-medical interventions such as counseling, support groups, and social transition support. Importantly, gender affirming care is not a one-size-fits-all approach; rather, it is personalized to reflect the diverse experiences and identities within the transgender and gender non-conforming communities.

Despite significant progress in recent years, access to gender affirming care remains a challenge for many individuals due to various barriers, including financial constraints, lack of knowledgeable providers, and discriminatory practices within healthcare systems. Addressing these barriers and promoting equitable access to gender affirming care is essential to ensuring that all individuals have the opportunity to live authentically and access the support they need to thrive.

The Debate of the Research Support for Gender Affirming Care

The research debate surrounding gender affirming care encompasses a wide range of perspectives and areas of inquiry, reflecting the complex and evolving nature of this field. At its core, this debate centers on questions related to the effectiveness, safety, and ethical considerations of various interventions and approaches within gender affirming care.

One key area of research debate concerns the long-term outcomes of medical interventions such as hormone therapy and surgical procedures. While numerous studies have documented significant improvements in mental health, quality of life, and overall well-being among individuals who undergo gender affirming treatments, some researchers raise questions about potential risks and unknowns, particularly regarding the long-term effects of hormone therapy and surgical procedures on physical health and psychosocial outcomes.

Additionally, there is ongoing debate regarding the optimal timing and approach to gender affirming interventions, particularly among transgender youth. Some researchers advocate for early intervention to alleviate gender dysphoria and support healthy development, while others express concerns about the potential for regret or uncertainty among youth who may be exploring their gender identity. This debate highlights the need for more research to better understand the experiences and needs of transgender youth and to inform evidence-based guidelines for gender affirming care in this population.

Ethical considerations also play a central role in the research debate surrounding gender affirming care. Questions related to informed consent, autonomy, and medical decision-making are complex and multifaceted, particularly in the context of interventions such as hormone therapy and surgical procedures. Critics of gender affirming care often raise concerns about the irreversible nature of some interventions and the potential for individuals to later regret their decisions. Proponents, on the other hand, emphasize the importance of respecting individuals’ autonomy and self-determination, arguing that gender affirming care is essential for alleviating gender dysphoria and promoting mental health and well-being.

Furthermore, the research debate surrounding gender affirming care extends to broader societal attitudes and policies. Discrimination, stigma, and lack of access to affirming care remain significant barriers for many transgender and gender non-conforming individuals, highlighting the need for research to inform advocacy efforts and policy change.

Overall, the research debate surrounding gender affirming care reflects the complexities and nuances of this field, as well as the ongoing efforts to advance knowledge, understanding, and access to affirming and equitable care for transgender and gender non-conforming individuals. By engaging in rigorous research and dialogue, researchers, healthcare providers, policymakers, and advocates can work towards promoting the well-being and rights of all individuals, regardless of their gender identity.

LISTEN TO THIS podcast to learn more from a doctor on why gender affirming care is important: Evidence-Based Gender-Affirming Care for Young Adults with Robert Garofalo, MD, MPH

READ THIS empirical journal article discussing some of the ethical and practical concerns providers have about gender-affirming care for adolescents: Current Concerns About Gender-Affirming Therapy in Adolescents

REFERENCES AND RESOURCES

Listed below are the references and resources used to curate this module:

Carter, Sarah, et al. (2019). Lifespan Development. Lumen Learning. courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/.

Human Growth and Development: Press Books: https://pressbooks.pub/mccdevpsych/

Cho, June, et al. (Sept. 2011). Effects of Gender on the Health and Development of Medically At-Risk Infants. HHS Public Access. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2951302/.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Childhood Obesity Facts https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html#:~:text=Prevalence%20of%20Childhood%20Obesity%20in%20the%20United%20States&text=The%20prevalence%20of%20obesity%20was,to%2019%2Dyear%2Dolds.