5 Module 5: Infancy and Toddlerhood Development

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Describe Physical Growth

Explain the patterns of physical growth and brain development in infants and toddlers, including the role of nutrition and monitoring growth milestones. - Explain Motor Skills

Differentiate between gross and fine motor skills and identify key developmental milestones for each. - Understand Reflexes and Movements

Describe infant reflexes and how they transition to voluntary motor skills during the first two years. - Discuss Nutrition and Feeding

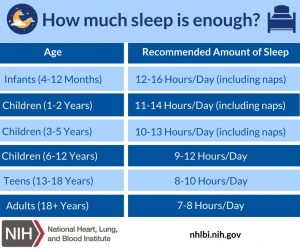

Explain the importance of breastfeeding, the introduction of solid foods, and the risks of malnutrition, including conditions like marasmus and kwashiorkor. - Analyze Sleep Patterns

Discuss typical sleep patterns in infancy, common sleep concerns, and guidelines for safe sleeping practices. - Understand Cognitive Development

Summarize Piaget’s stages of sensorimotor intelligence and explain how infants learn and develop problem-solving skills. - Examine Language Development

Compare major theories of language development and identify milestones in communication and language acquisition. - Explore Sensory Development

Explain how sensory abilities, such as vision, hearing, and touch, develop during infancy and their role in early learning. - Discuss Emotional Development

Identify key milestones in emotional development, including the emergence of self-awareness, social smiling, and stranger anxiety. - Contrast Attachment Styles

Describe the different attachment styles identified in research and their implications for social and emotional development. - Examine Theories of Temperament

Explain how temperament differences are observed in infancy and their potential impact on personality development. - Analyze the Role of Caregiving

Discuss how caregivers influence emotional regulation, attachment, and overall development in infancy and toddlerhood.

Infancy and Toddler Development

The average newborn weighs approximately 7.5 pounds, although a healthy birth weight for a full-term baby is considered to be between 5 pounds, 8 ounces (2,500 grams) and 8 pounds, 13 ounces (4,000 grams). The average length of a newborn is 19.5 inches, increasing to 29.5 inches by 12 months and 34.4 inches by 2 years old.

For the first few days of life, infants typically lose about 5 percent of their body weight as they eliminate waste and get used to feeding. This often goes unnoticed by most parents, but can be cause for concern for those who have a smaller infant. This weight loss is temporary, however, and is followed by a rapid period of growth. By the time an infant is 4 months old, it usually doubles in weight, and by one year has tripled its birth weight. By age 2, the weight has quadrupled. The average length at 12 months (one year old) typically ranges from 28.5-30.5 inches. The average length at 24 months (two years old) is around 33.2-35.4 inches.

Monitoring Physical Growth

As mentioned earlier, growth is so rapid in infancy that the consequences of neglect can be severe. For this reason, gains are closely monitored. At each well-baby check-up, a baby’s growth is compared to that baby’s previous numbers. Often, measurements are expressed as a percentile from 0 to 100, which compares each baby to other babies the same age. For example, weight at the 40th percentile means that 40 percent of all babies weigh less, and 60 percent weight more. For any baby, pediatricians and parents can be alerted early just by watching percentile changes. If an average baby moves from the 50th percentile to the 20th, this could be a sign of failure to thrive, which could be caused by various medical conditions or factors in the child’s environment. The earlier the concern is detected, the earlier intervention and support can be provided for the infant and caregiver.

Body Proportions

Another dramatic physical change that takes place in the first several years of life is a change in body proportions. The head initially makes up about 50 percent of a person’s entire length when developing in the womb. At birth, the head makes up about 25 percent of a person’s length (just imagine how big your head would be if the proportions remained the same throughout your life!). In adulthood, the head comprises about 15 percent of a person’s length. Imagine how difficult it must be to raise one’s head during the first year of life! And indeed, if you have ever seen a 2- to 4-month-old infant lying on their stomach trying to raise the head, you know how much of a challenge this is.

The Brain in the First Two Years

Some of the most dramatic physical change that occurs during this period is in the brain. At birth, the brain is about 25 percent of its adult weight, and this is not true for any other part of the body. By age 2, it is at 75 percent of its adult weight, at 95 percent by age 6, and at 100 percent by age 7 years.

While most of the brain’s 100 to 200 billion neurons are present at birth, they are not fully mature and during the next several years dendrites or connections between neurons will undergo a period of transient exuberance or temporary dramatic growth. There is a proliferation of these dendrites during the first two years so that by age 2, a single neuron might have thousands of dendrites. After this dramatic increase, the neural pathways that are not used will be eliminated thereby making those that are used much stronger. This activity is occurring primarily in the cortex or the thin outer covering of the brain involved in voluntary activity and thinking. The prefrontal cortex that is located behind our forehead continues to grow and mature throughout childhood and experiences an addition growth spurt during adolescence. It is the last part of the brain to mature and will eventually comprise 85 percent of the brain’s weight. Experience will shape which of these connections are maintained and which of these are lost. Ultimately, about 40 percent of these connections will be lost (Webb, Monk, and Nelson, 2001). As the prefrontal cortex matures, the child is increasingly able to regulate or control emotions, to plan activity, strategize, and have better judgment. Of course, this is not fully accomplished in infancy and toddlerhood, but continues throughout childhood and adolescence.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions describing some of the remarkable brain development that takes places in the first few years of life:

Another major change occurring in the central nervous system is the development of myelin, a coating of fatty tissues around the axon of the neuron. Myelin helps insulate the nerve cell and speed the rate of transmission of impulses from one cell to another. This enhances the building of neural pathways and improves coordination and control of movement and thought processes. The development of myelin continues into adolescence but is most dramatic during the first several years of life.

From Reflexes to Voluntary Movements

Every basic motor skill (any movement ability) develops over the first two years of life. The sequence of motor skills first begins with reflexes. Infants are equipped with a number of reflexes, or involuntary movements in response to stimulation, and some are necessary for survival. These include the breathing reflex, or the need to maintain an oxygen supply (this includes hiccups, sneezing, and thrashing reflexes), reflexes that maintain body temperature (crying, shivering, tucking the legs close, and pushing away blankets), the sucking reflex, or automatically sucking on objects that touch their lips, and the rooting reflex, which involves turning toward any object that touches the cheek (which manages feeding, including the search for a nipple). Other reflexes are not necessary for survival, but signify the state of brain and body functions. Some of these include: the babinski reflex (toes fan upward when feet are stroked), the stepping reflex (babies move their legs as if to walk when feet touch a flat surface), the palmar grasp (the infant will tightly grasp any object placed in its palm), and the moro reflex (babies will fling arms out and then bring to chest if they hear a loud noise). These movements occur automatically and are signals that the infant is functioning well neurologically. Within the first several weeks of life, these reflexes are replaced with voluntary movements or motor skills.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions to see examples of newborn reflexes:

Motor Development

Motor development occurs in an orderly sequence as infants move from reflexive reactions (e.g., sucking and rooting) to more advanced motor functioning. This development proceeds in a cephalocaudal (from head-down) and proximodistal (from center-out) direction. For instance, babies first learn to hold their heads up, then sit with assistance, then sit unassisted, followed later by crawling, pulling up, cruising, and then walking. As motor skills develop, there are certain developmental milestones that young children should achieve. For each milestone, there is an average age, as well as a range of ages in which the milestone should be reached. An example of a developmental milestone is a baby holding up its head. Babies on average are able to hold up their head at 6 weeks old, and 90% of babies achieve this between 3 weeks and 4 months old. If a baby is not holding up his head by 4 months old, he is showing a delay. Sitting involves both coordination and muscle strength, and 90% of babies achieve this milestone between 5 and 9 months old (CDC, 2018).

Gross Motor Skills

Gross motor skills are voluntary movements that involve the use of large muscle groups and are typically large movements of the arms, legs, head, and torso. These skills begin to develop first. Examples include moving to bring the chin up when lying on the stomach, moving the chest up, rocking back and forth on hands and knees. But it also includes exploring an object with one’s feet as many babies do, as early as 8 weeks of age, if seated in a carrier or other device that frees the hips. This may be easier than reaching for an object with the hands, which requires much more practice. And sometimes an infant will try to move toward an object while crawling and surprisingly move backward because of the greater amount of strength in the arms than in the legs!

Fine Motor Skills

Fine motor skills are more exact movements of the hands and fingers and include the ability to reach and grasp an object. These skills focus on the muscles in the fingers, toes, and eyes, and enable coordination of small actions (e.g., grasping a toy, writing with a pencil, and using a spoon). Newborns cannot grasp objects voluntarily but do wave their arms toward objects of interest. At about 4 months of age, the infant is able to reach for an object, first with both arms and within a few weeks, with only one arm. Grasping an object involves the use of the fingers and palm, but no thumbs. Stop reading for a moment and try to grasp an object using the fingers and the palm.

How does that feel? How much control do you have over the object? If it is a pen or pencil, are you able to write with it? Can you draw a picture? The answer is, probably not. Use of the thumb comes at about 9 months of age when the infant is able to grasp an object using the forefinger and thumb (the pincer grasp). This ability greatly enhances the ability to control and manipulate an object, and infants take great delight in this newfound ability. They may spend hours picking up small objects from the floor and placing them in containers. By 9 months, an infant can also watch a moving object, reach for it as it approaches, and grab it. This is quite a complicated set of actions if we remember how difficult this would have been just a few months earlier.

Timeline of Developmental Milestones |

||

|

Age |

Developmental Milestone |

|

|

~2 months |

Can hold head upright on own Smiles at sound of familiar voices and follows movement with eyes |

|

|

~3 months |

Can raise head and chest from prone position Smiles at others |

Grasps objects Rolls from side to back |

|

~4-5 months |

Babbles, laughs, and tries to imitate sounds |

Begins to roll from back to side |

|

~6 months |

Moves objects from hand to hand |

|

|

~7-8 months |

Can sit without support May begin to crawl |

Responds to own name Finds partially hidden objects |

|

~8-9 months |

Walks while holding on Babbles “mama” and “dada” |

Claps |

|

~11-12 months |

Stands alone Begins to walk |

Says at least one word Can stack two blocks |

|

~18 months |

Walks independently Drinks from a cup |

Says at least 15 words Points to body parts |

|

~2 years |

Runs and jumps Uses two-word sentences |

Follows simple instructions Begins make-believe play |

|

~3 years |

Speaks in multi-word sentences |

Sorts objects by shape and color |

|

~4 years |

Draws circles and squares Rides a tricycle |

Gets along with people outside of the family Gets dressed |

|

~5 years |

Can jump, hop, and skip Knows name and address |

Counts ten or more objects |

Sensory Development

As infants and children grow, their senses play a vital role in encouraging and stimulating the mind and in helping them observe their surroundings. Two terms are important to understand when learning about the senses. The first is sensation, or the interaction of information with the sensory receptors. The second is perception, or the process of interpreting what is sensed. It is possible for someone to sense something without perceiving it. Gradually, infants become more adept at perceiving with their senses, making them more aware of their environment and presenting more affordances or opportunities to interact with objects.

Vision

What can young infants see, hear, and smell? Newborn infants’ sensory abilities are significant, but their senses are not yet fully developed. Many of a newborn’s innate preferences facilitate interaction with caregivers and other humans. The womb is a dark environment void of visual stimulation. Consequently, vision is the most poorly developed sense at birth. Newborns typically cannot see further than 8 to 16 inches away from their faces, have difficulty keeping a moving object within their gaze, and can detect contrast more than color differences. If you have ever seen a newborn struggle to see, you can appreciate the cognitive efforts being made to take in visual stimulation and build those neural pathways between the eye and the brain.

Although vision is their least developed sense, newborns already show a preference for faces. When you glance at a person, where do you look? Chances are you look into their eyes. If so, why? It is probably because there is more information there than in other parts of the face. Newborns do not scan objects this way; rather, they tend to look at the chin or another less detailed part of the face. However, by 2 or 3 months, they will seek more detail when visually exploring an object and begin showing preferences for unusual images over familiar ones, for patterns over solids, faces over patterns, and three-dimensional objects over flat images. Newborns have difficulty distinguishing between colors, but within a few months are able to distinguish between colors as well as adults. Infants can also sense depth as binocular vision develops at about 2 months of age. By 6 months, the infant can perceive depth in pictures as well. Infants who have experience crawling and exploring will pay greater attention to visual cues of depth and modify their actions accordingly.

Hearing

The infant’s sense of hearing is very keen at birth. If you remember from an earlier module, this ability to hear is evidenced as soon as the 5th month of prenatal development. In fact, an infant can distinguish between very similar sounds as early as one month after birth and can distinguish between a familiar and non-familiar voice even earlier. Babies who are just a few days old prefer human voices, they will listen to voices longer than sounds that do not involve speech, and they seem to prefer their mother’s voice over a stranger’s voice. In an interesting experiment, 3-week-old babies were given pacifiers that played a recording of the infant’s mother’s voice and of a stranger’s voice. When the infants heard their mother’s voice, they sucked more strongly at the pacifier. Some of this ability will be lost by 7 or 8 months as a child becomes familiar with the sounds of a particular language and less sensitive to sounds that are part of an unfamiliar language.

Pain and Touch

Immediately after birth, a newborn is sensitive to touch and temperature, and is also sensitive to pain, responding with crying and cardiovascular responses. Newborns who are circumcised (the surgical removal of the foreskin of the penis) without anesthesia experience pain, as demonstrated by increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, decreased oxygen in the blood, and a surge of stress hormones. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), there are medical benefits and risks to circumcision. They do not recommend routine circumcision, however, they stated that because of the possible benefits (including prevention from urinary tract infections, penile cancer, and some STDs) parents should have the option to circumcise their sons if they want to.

The sense of touch is acute in infants and is essential to a baby’s growth of physical abilities, language and cognitive skills, and socio-emotional competency. Touch not only impacts short-term development during infancy and early childhood but also has long-term effects, suggesting the power of positive gentle touch from birth. Through touch, infants learn about their world, bond with their caregiver, and communicate their needs and wants. Research emphasizes the great benefits of touch for premature babies, but the presence of such contact has been shown to benefit all children. In an extreme example, some children in Romania were reared in orphanages in which a single care worker may have had as many as 10 infants to care for at one time. These infants were not often helped or given toys with which to play. As a result, many of them were developmentally delayed. When we discuss emotional and social development later in this module, you will also see the important role that touch plays in helping infants feel safe and protected, which builds trust and secure attachments between the child and their caregiver.

Taste and Smell

Not only are infants sensitive to touch, but newborns can also distinguish between sour, bitter, sweet, and salty flavors and show a preference for sweet flavors. They can distinguish between their mother’s scent and that of others, and prefer the smell of their mothers. A newborn placed on the mother’s chest will inch up to the mother’s breast, as it is a potent source of the maternal odor. Even on the first day of life, infants orient to their mother’s odor and are soothed, when crying, by their mother’s odor.

CLICK THIS: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes the developmental milestones for children from 2 months through 5 years old. The website has interactive questions, videos, and descriptions. Check it out!

Sleep

Infants 0 to 2 years of age sleep an average of 12.8 hours a day, although this change and develops gradually throughout an infant’s life. For the first three months, newborns sleep between 14 and 17 hours a day, then they become increasingly alert for longer periods of time. About one-half of an infant’s sleep is rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and infants often begin their sleep cycle with REM rather than non-REM sleep. They also move through the sleep cycle more quickly than adults.

Parents spend a significant amount of time worrying about and losing even more sleep over their infant’s sleep schedule, but there remains a great deal of variation in sleep patterns and habits for individual children. A 2018 study showed that at 6 months of age, 62% of infants slept at least six hours during the night, 43% of infants slept at least 8 hours through the night, and 38% of infants were not sleeping at least six continual hours through the night. At 12 months, 28% of children were still not sleeping at least 6 uninterrupted hours through the night, while 78% were sleeping at least 6 hours, and 56% were sleeping at least 8 hours.

The most common infant sleep-related problem reported by parents is nighttime waking. Studies of new parents and sleep patterns show that parents lose the most sleep during the first three months with a new baby, with mothers losing about an hour of sleep each night, and fathers losing a disproportionate 13 minutes. This decline in sleep quality and quantity for adults persists until the child is about six years old.

While this shows there is no precise science as to when and how an infant will sleep, there are general trends in sleep patterns. Around six months, babies typically sleep between 14-15 hours a day, with 3-4 of those hours happening during daytime naps. As they get older, these naps decrease from several to typically two naps a day between ages 9-18 months. Often, periods of rapid weight gain or changes in developmental abilities such as crawling or walking will cause changes to sleep habits as well. Infants generally move towards one 2-4 hour nap a day by around 18 months, and many children will continue to nap until around four or five years old.

Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths (SUID)

Each year in the United States, there are about 3,500 Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths (SUID). These deaths occur among infants less than one-year-old and have no immediately obvious cause. The three commonly reported types of SUID are:

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS): SIDS is identified when the death of a healthy infant occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, and medical and forensic investigation findings (including an autopsy) are inconclusive. SIDS is the leading cause of death in infants up to 12 months old, and approximately 1,500 infants died of SIDS in 2013 (CDC, 2015). The risk of SIDS is highest at 4 to 6 weeks of age. Because SIDS is diagnosed when no other cause of death can be determined, possible causes of SIDS are regularly researched. One leading hypothesis suggests that infants who die from SIDS have abnormalities in the area of the brainstem responsible for regulating breathing. Although the exact cause is unknown, doctors have identified the following risk factors for SIDS:

- low birth weight

- siblings who have had SIDS

- sleep apnea

- of African-American or Inuit descent

- low socioeconomic status (SES)

- smoking in the home

Unknown cause: The sudden death of an infant less than one year of age that cannot be explained because a thorough investigation was not conducted and the cause of death could not be determined.

Accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed: Reasons for accidental suffocation include the following: suffocation by soft bedding, another person rolling on top of or against the infant while sleeping, an infant being wedged between two objects such as a mattress and wall, and strangulation such as when an infant’s head and neck become caught between crib railings.

The combined SUID rate declined considerably following the release of the American Academy of Pediatrics safe sleep recommendations in 1992, which advocated that infants be placed on their backs for sleep (non-prone position). These recommendations were followed by a major Back to Sleep Campaign in 1994. According to the CDC, the SIDS death rate is now less than one-fourth of what it was (130 per 100,000 live birth in 1990 versus 40 in 2015). However, accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed mortality rates remained unchanged until the late 1990s. Some parents were still putting newborns to sleep on their stomachs partly because of past tradition. Most SIDS victims experience several risks, an interaction of biological and social circumstances. But thanks to research, the major risk, stomach sleeping, has been highly publicized. Other causes of death during infancy include congenital birth defects and homicide.

Co-Sleeping

The location of sleep depends primarily on the baby’s age and culture. Bed-sharing (in the parents’ bed) or co-sleeping (in the parents’ room) is the norm is some cultures, but not in others. Colvin, Collie-Akers, Schunn and Moon (2014) analyzed a total of 8,207 deaths from 24 states during 2004–2012. The deaths were documented in the National Center for the Review and Prevention of Child Deaths Case Reporting System, a database of death reports from state child death review teams. The results indicated that younger victims (0-3 months) were more likely to die by bed-sharing and sleeping in an adult’s bed or on a person. A higher percentage of older victims (4 months to 364 days) rolled into objects in the sleep environment and changed position from side/back to prone. Carpenter et al. (2013) compared infants who died of SIDS with a matched control and found that infants younger than three months old who slept in bed with a parent were five times more likely to die of SIDS compared to babies who slept separately from the parents, but were still in the same room. They concluded that bed-sharing, even when the parents do not smoke or take alcohol or drugs, increases the risk of SIDS. However, when combined with parental smoking and maternal alcohol consumption and/or drug use, the risks associated with bed-sharing greatly increased.

Despite the risks noted above, the controversy about where babies should sleep has been ongoing. Co-sleeping has been recommended for those who advocate attachment parenting and other research suggests that bed-sharing and co-sleeping is becoming more popular in the United States. So, what are the latest recommendations?

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) actually updated their recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment in 2016. The most recent AAP recommendations on creating a safe sleep environment include:

- Back to sleep for every sleep. Always place the baby on their back on a firm sleep surface such as a crib or bassinet with a tight-fitting sheet.

- Avoid the use of soft bedding, including crib bumpers, blankets, pillows, and soft toys. The crib should be bare.

- Breastfeeding is recommended.

- Share a bedroom with parents, but not the same sleeping surface, preferably until the baby turns 1 but at least for the first six months. Room-sharing decreases the risk of SIDS by as much as 50 percent.

- Avoid baby’s exposure to smoke, alcohol, and illicit drugs.

As you can see, there is a recommendation to now “share a bedroom with parents,” but not the same sleeping surface. Breastfeeding is also recommended as adding protection against SIDS, but after feeding, the AAP encourages parents to move the baby to their separate sleeping space, preferably a crib or bassinet in the parents’ bedroom. Finally, the report included new evidence that supports skin-to-skin care for newborn infants.

Immunizations and Nutrition

Preventing communicable diseases from early infancy is one of the major tasks of the Public Health System in the USA. Infants mouth every single object they find as one of their typical developmental tasks. They learn through their senses and tasting objects stimulates their brain and provides a sensory experience as well as learning.

Infants have much contact with dirty surfaces. They lay on a carpet that most likely has been contaminated by adults walking on it; they mouth keys, rattles, toys, and books; they crawl on the floor; they hold on to furniture to walk, and much more. How do we prevent infants from getting sick? One possible answer is immunizations.

WATCH THIS FRONTLINE documentary video “The Vaccine War” below or online to learn more about how immunization rates declined and the outcomes from it. You can view a transcript or watch online with captions here.

Many decades ago, our society struggled to find vaccines and cures for illnesses such as Polio, whooping cough, and many other medical conditions. A few decades ago parents started changing their minds on the need to vaccinate children. Some children are not vaccinated for valid medical reasons, but some states allow a child to be unvaccinated because of a parent’s personal or religious beliefs. At least 1 in 14 children is not vaccinated. What is the outcome of not vaccinating children? Some of the preventable illnesses are returning. Fortunately, each vaccinated child stops the transmission of the disease, a phenomenon called herd immunity. Usually, if 90% of the people in a community (a herd) are immunized, no one dies of that disease.

In 2017, Community Care Licensing in California, the agency that regulates childcare centers, changed regulations. Before it was possible for parents to opt-out of vaccinations due to personal beliefs, but this changed after Governor Brown signed a Bill in 2016 to only exclude children from being vaccinated if there were medical reasons. Furthermore, all personnel working with children must be immunized.

Nutrition

Good nutrition in a supportive environment is vital for an infant’s healthy growth and development. Remember, from birth to 1 year, infants triple their weight and increase their height by half, and this growth requires good nutrition. For the first 6 months, babies are fed breast milk or formula. Starting good nutrition practices early can help children develop healthy dietary patterns. Infants need to receive nutrients to fuel their rapid physical growth. Malnutrition during infancy can result in not only physical but also cognitive and social consequences. Without proper nutrition, infants cannot reach their physical potential.

Benefits of Breastfeeding

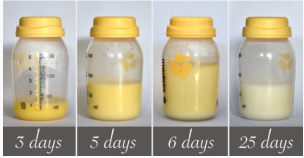

Breast milk is considered the ideal diet for newborns due to the nutritional makeup of colostrum and subsequent breastmilk production. Colostrum, the milk produced during pregnancy and just after birth, has been described as “liquid gold.” Colostrum is packed with nutrients and other important substances that help the infant build up their immune system. Most babies will get all the nutrition they need through colostrum during the first few days of life. Breast milk changes by the third to fifth day after birth, becoming much thinner, but containing just the right amount of fat, sugar, water, and proteins to support overall physical and neurological development. It provides a source of iron more easily absorbed in the body than the iron found in dietary supplements, it provides resistance against many diseases, it is more easily digested by infants than formula, and it helps babies make a transition to solid foods more easily than if bottle-fed.

The reason infants need such a high fat content is the process of myelination which requires fat to insulate the neurons. There has been some research, including meta-analyses, to show that breastfeeding is connected to advantages with cognitive development (Anderson, Johnstone, & Remley, 1999)[2]. Low birth weight infants had greater benefits from breastfeeding than did normal-weight infants in a meta-analysis of twenty controlled studies examining the overall impact of breastfeeding (Anderson et al., 1999). This meta-analysis showed that breastfeeding may provide nutrients required for rapid development of the immature brain and be connected to more rapid or better development of neurologic function. The studies also showed that a longer duration of breastfeeding was accompanied by greater differences in cognitive development between breastfed and formula-fed children. Whereas normal-weight infants showed a 2.66-point difference, low-birth-weight infants showed a 5.18-point difference in IQ compared with weight-matched, formula-fed infants (Anderson et al, 1999). These studies suggest that nutrients present in breast milk may have a significant effect on neurologic development in both premature and full-term infants.

Several recent studies have reported that it is not just babies that benefit from breastfeeding. Breastfeeding stimulates contractions in the uterus to help it regain its normal size, and women who breastfeed are more likely to space their pregnancies farther apart. Mothers who breastfeed are at lower risk of developing breast cancer, especially among higher-risk racial and ethnic groups. Other studies suggest that women who breastfeed have lower rates of ovarian cancer, and reduced risk for developing Type 2 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis.

For most babies, breast milk is also easier to digest than formula. Formula-fed infants experience more diarrhea and upset stomachs. The absence of antibodies in formula often results in a higher rate of ear infections and respiratory infections. Children who are breastfed have lower rates of childhood leukemia, asthma, obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, and a lower risk of SIDS. For all of these reasons, it is recommended that mothers breastfeed their infants until at least 6 months of age and that breast milk be used in the diet throughout the first year.

Most mothers who breastfeed in the United States stop breastfeeding at about 6-8 weeks, often in order to return to work outside the home (United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), 2011). Mothers can certainly continue to provide breast milk to their babies by expressing and freezing the milk to be bottle fed at a later time or by being available to their infants at feeding time, but some mothers find that after the initial encouragement they receive in the hospital to breastfeed, the outside world is less supportive of such efforts. Some workplaces support breastfeeding mothers by providing flexible schedules and welcoming infants, but many do not. And the public support of breastfeeding is sometimes lacking. Women in Canada are more likely to breastfeed than are those in the United States, and the Canadian health recommendation is for breastfeeding to continue until 2 years of age. Facilities in public places in Canada such as malls, ferries, and workplaces provide more support and comfort for the breastfeeding mother and child than found in the United States.

In addition to the nutritional and health benefits of breastfeeding, breast milk is free! Anyone who has priced formula recently can appreciate this added incentive to breastfeeding. Prices for a month’s worth of formula can easily range from $130-$200. Prices for a year’s worth of formula and feeding supplies can cost well over $1,500 (USDHHS, 2011).

When Breastfeeding Doesn’t Work or You Choose Not to

There are occasions where mothers may be unable to breastfeed babies, often for a variety of health, social, and emotional reasons. For example, breastfeeding generally does not work:

- when the baby is adopted

- when the biological mother has a transmissible disease such as tuberculosis or HIV

- when the mother is addicted to drugs or taking any medication that may be harmful to the baby (including some types of birth control)

- when the infant was born to (or adopted by) a family with two fathers and the surrogate mother is not available to breastfeed

- when there are attachment issues between mother and baby

- when the mother or the baby is in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) after the delivery process

- when the baby and mother are attached but the mother does not produce enough breast-milk

One early argument given to promote the practice of breastfeeding (when health issues are not the case) is that it promotes bonding and healthy emotional development for infants. However, this does not seem to be a unique case. Breastfed and bottle-fed infants adjust equally well emotionally. This is good news for mothers who may be unable to breastfeed for a variety of reasons and for fathers who might feel left out as a result.

Introducing Solid Foods

Breast milk or formula is the only food a newborn needs, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months after birth. Solid foods can be introduced from around six months onward when babies develop stable sitting and oral feeding skills but should be used only as a supplement to breast milk or formula. By six months, the gastrointestinal tract has matured, solids can be digested more easily, and allergic responses are less likely. The infant is also likely to develop teeth around this time, which aids in chewing solid food. Iron-fortified infant cereal, made of rice, barley, or oatmeal, is typically the first solid introduced due to its high iron content. Cereals can be made of rice, barley, or oatmeal. Generally, salt, sugar, processed meat, juices, and canned foods should be avoided.

Though infants usually start eating solid foods between 4 and 6 months of age, more and more solid foods are consumed by a growing toddler. Pediatricians recommended introducing foods one at a time, and for a few days, in order to identify any potential food allergies. Toddlers may be picky at times, but it remains important to introduce a variety of foods and offer food with essential vitamins and nutrients, including iron, calcium, and vitamin D.

Milk Anemia in the United States

About 9 million children in the United States are malnourished (Children’s Welfare, 1998). More still suffer from milk anemia, a condition in which milk consumption leads to a lack of iron in the diet. The prevalence of iron deficiency anemia in 1- to 3-year-old children seems to be increasing (Kazal, 2002)[8]. The body gets iron through certain foods. Toddlers who drink too much cow’s milk may also become anemic if they are not eating other healthy foods that have iron. This can be due to the practice of giving toddlers milk as a pacifier when resting, riding, walking, and so on. Appetite declines somewhat during toddlerhood and a small amount of milk (especially with added chocolate syrup) can easily satisfy a child’s appetite for many hours. The calcium in milk interferes with the absorption of iron in the diet as well. There is also a link between iron deficiency anemia and diminished mental, motor, and behavioral development. In the second year of life, iron deficiency can be prevented by the use of a diversified diet that is rich in sources of iron and vitamin C, limiting cow’s milk consumption to less than 24 ounces per day, and providing a daily iron-fortified vitamin.

Global Considerations and Malnutrition

In the 1960s, formula companies led campaigns in developing countries to encourage mothers to feed their babies on infant formula. Many mothers felt that formula would be superior to breast milk and began using formula. The use of formula can certainly be healthy under conditions in which there is adequate, clean water with which to mix the formula and adequate means to sanitize bottles and nipples. However, in many of these countries, such conditions were not available and babies often were given diluted, contaminated formula which made them become sick with diarrhea and become dehydrated. These conditions continue today and now many hospitals prohibit the distribution of formula samples to new mothers in efforts to get them to rely on breastfeeding. Many of these mothers do not understand the benefits of breastfeeding and have to be encouraged and supported in order to promote this practice.

The World Health Organization (2018) recommends:

- initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth

- exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life

- introduction of solid foods at six months together with continued breastfeeding up to two years of age or beyond

Children in developing countries and countries experiencing the harsh conditions of war are at risk for two major types of malnutrition. Infantile marasmus refers to starvation due to a lack of calories and protein. Children who do not receive adequate nutrition lose fat and muscle until their bodies can no longer function. Babies who are breastfed are much less at risk of malnutrition than those who are bottle-fed. After weaning, children who have diets deficient in protein may experience kwashiorkor, or the “disease of the displaced child,” often occurring after another child has been born and taken over breastfeeding. This results in a loss of appetite and swelling of the abdomen as the body begins to break down the vital organs as a source of protein.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions to learn more about the signs and symptoms of kwashiorkor and marasmus:

Cognitive Development

In order to adapt to the evolving environment around us, humans rely on cognition, both adapting to the environment and also transforming it. In general, all theorists studying cognitive development address three main issues:

- The typical course of cognitive development

- The unique differences between individuals

- The mechanisms of cognitive development (the way genetics and environment combine to generate patterns of change)

Piaget and Sensorimotor Intelligence

How do infants connect and make sense of what they are learning? Remember that Piaget believed that we are continuously trying to maintain cognitive equilibrium, or balance, between what we see and what we know. Children have much more of a challenge in maintaining this balance because they are constantly being confronted with new situations, new words, new objects, etc. All this new information needs to be organized, and a framework for organizing information is referred to as a schema. Children develop schemas through the processes of assimilation and accommodation.

For example, 2-year-old Deja learned the schema for dogs because her family has a Poodle. When Deja sees other dogs in her picture books, she says, “Look mommy, dog!” Thus, she has assimilated them into her schema for dogs. One day, Deja sees a sheep for the first time and says, “Look mommy, dog!” Having a basic schema that a dog is an animal with four legs and fur, Deja thinks all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. When Deja’s mom tells her that the animal she sees is a sheep, not a dog, Deja must accommodate her schema for dogs to include more information based on her new experiences. Deja’s schema for dog was too broad since not all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. She now modifies her schema for dogs and forms a new one for sheep.

Let’s examine the transition that infants make from responding to the external world reflexively as newborns, to solving problems using mental strategies as two-year-olds. Piaget called this first stage of cognitive development sensorimotor intelligence (the sensorimotor period) because infants learn through their senses and motor skills. He subdivided this period into six substages:

Sensorimotor substages by age |

|

|

Stage |

Age |

|

Stage 1 – Reflexes |

Birth to 6 weeks |

|

Stage 2 – Primary Circular Reactions |

6 weeks to 4 months |

|

Stage 3 – Secondary Circular Reactions |

4 months to 8 months |

|

Stage 4 – Coordination of Secondary Circular Reactions |

8 months to 12 months |

|

Stage 5 – Tertiary Circular Reactions |

12 months to 18 months |

|

Stage 6 – Mental Representation |

18 months to 24 months |

Substages of Sensorimotor Intelligence

For an overview of the substages of sensorimotor thought, it helps to group the six substages into pairs. The first two substages involve the infant’s responses to its own body, call primary circular reactions. During the first month first (substage one), the infant’s senses, as well motor reflexes are the foundation of thought.

Substage One: Reflexive Action (Birth through 1st month)

This active learning begins with automatic movements or reflexes (sucking, grasping, staring, listening). A ball comes into contact with an infant’s cheek and is automatically sucked on and licked. But this is also what happens with a sour lemon, much to the infant’s surprise! The baby’s first challenge is to learn to adapt the sucking reflex to bottles or breasts, pacifiers or fingers, each acquiring specific types of tongue movements to latch, suck, breathe, and repeat. This adaptation demonstrates that infants have begun to make sense of sensations. Eventually, the use of these reflexes becomes more deliberate and purposeful as they move onto substage two.

Substage Two: First Adaptations to the Environment (1st through 4th months)

Fortunately, within a few days or weeks, the infant begins to discriminate between objects and adjust responses accordingly as reflexes are replaced with voluntary movements. An infant may accidentally engage in a behavior and find it interesting, such as making a vocalization. This interest motivates trying to do it again and helps the infant learn a new behavior that originally occurred by chance. The behavior is identified as circular and primary because it centers on the infant’s own body. At first, most actions have to do with the body, but in months to come, will be directed more toward objects. For example, the infant may have different sucking motions for hunger and others for comfort (i.e. sucking a pacifier differently from a nipple or attempting to hold a bottle to suck it).

The next two substages (3 and 4), involve the infant’s responses to objects and people, called secondary circular reactions. Reactions are no longer confined to the infant’s body and are now interactions between the baby and something else.

Substage Three: Repetition (4th through 8th months)

During the next few months, the infant becomes more and more actively engaged in the outside world and takes delight in being able to make things happen by responding to people and objects. Babies try to continue any pleasing event. Repeated motion brings particular interest as the infant is able to bang two lids together or shake a rattle and laugh. Another example might be to clap their hands when a caregiver says “patty-cake.” Any sight of something delightful will trigger efforts for interaction.

Substage Four: New Adaptations and Goal-Directed Behavior (8th through 12th months)

Now the infant becomes more deliberate and purposeful in responding to people and objects and can engage in behaviors that others perform and anticipate upcoming events. Babies may ask for help by fussing, pointing, or reaching up to accomplish tasks, and work hard to get what they want. Perhaps because of continued maturation of the prefrontal cortex, the infant becomes capable of having a thought and carrying out a planned, goal-directed activity such as seeking a toy that has rolled under the couch or indicating that they are hungry. The infant is coordinating both internal and external activities to achieve a planned goal and begins to get a sense of social understanding. Piaget believed that at about 8 months (during substage 4), babies first understood the concept of object permanence, which is the realization that objects or people continue to exist when they are no longer in sight.

The last two stages (5 and 6), called tertiary circular reactions, consist of actions (stage 5) and ideas (stage 6) where infants become more creative in their thinking.

Substage Five: Active Experimentation of “Little Scientists” (12th through 18th months)

The toddler is considered a “little scientist” and begins exploring the world in a trial-and-error manner, using motor skills and planning abilities. For example, the child might throw their ball down the stairs to see what happens or delight in squeezing all of the toothpaste out of the tube. The toddler’s active engagement in experimentation helps them learn about their world. Gravity is learned by pouring water from a cup or pushing bowls from high chairs. The caregiver tries to help the child by picking it up again and placing it on the tray. And what happens? Another experiment! The child pushes it off the tray again causing it to fall and the caregiver to pick it up again! A closer examination of this stage causes us to really appreciate how much learning is going on at this time and how many things we come to take for granted must actually be learned. This is a wonderful and messy time of experimentation and most learning occurs by trial and error.

WATCH THIS TED talk below or online to see examples of babies thinking like little scientists:

Substage Six: Mental Representations (18th month to 2 years of age)

The child is now able to solve problems using mental strategies, to remember something heard days before and repeat it, to engage in pretend play, and to find objects that have been moved even when out of sight. Take, for instance, the child who is upstairs in a room with the door closed, supposedly taking a nap. The doorknob has a safety device on it that makes it impossible for the child to turn the knob. After trying several times to push the door or turn the doorknob, the child carries out a mental strategy to get the door opened – he knocks on the door! Obviously, this is a technique learned from the past experience of hearing a knock on the door and observing someone opening the door. The child is now better equipped with mental strategies for problem-solving. Part of this stage also involves learning to use language. This initial movement from the “hands-on” approach to knowing about the world to the more mental world of stage six marked the transition to preoperational thinking, which you’ll learn more about in a later in the class.

Development of Object Permanence

A critical milestone during the sensorimotor period is the development of object permanence. Introduced during substage 4 above, object permanence is the understanding that even if something is out of sight, it continues to exist. The infant is now capable of making attempts to retrieve the object. Piaget thought that, at about 8 months, babies first understand the concept of objective permanence, but some research has suggested that infants seem to be able to recognize that objects have permanence at much younger ages (even as young as 4 months of age). Other researchers, however, are not convinced (Mareschal & Kaufman, 2012). It may be a matter of “grasping vs. mastering” the concept of objective permanence. Overall, we can expect children to grasp the concept that objects continue to exist even when they are not in sight by around 8 months old, but memory may play a factor in their consistency. Because toddlers (i.e., 12–24 months old) have mastered object permanence, they enjoy games like hide-and-seek, and they realize that when someone leaves the room they will come back (Loop, 2013). Toddlers also point to pictures in books and look in appropriate places when you ask them to find objects.

WATCH THIS video clip below or online with captions to see how researchers, like Dr. Rene Baillargeon, study object permanence in young infants. The style and cinematography in this video are dated, but the information is valuable.

Learning and Memory Abilities in Infants

Memory is central to cognitive development. Our memories form the basis for our sense of self, guide our thoughts and decisions, influence our emotional reactions, and allow us to learn (Bauer, 2008).

It is thought that Piaget underestimated memory ability in infants (Schneider, 2015).

As mentioned when discussing the development of infant senses, within the first few weeks of birth, infants recognize their caregivers by face, voice, and smell. Sensory and caregiver memories are apparent in the first month, motor memories by 3 months, and then, at about 9 months, more complex memories including language (Mullally & Maguire, 2014)[4]. There is agreement that memory is fragile in the first months of life, but that improves with age. Repeated sensations and brain maturation are required in order to process and recall events (Bauer, 2008). Infants remember things that happened weeks and months ago (Mullally & Maguire, 2014), although they most likely will not remember it decades later. From the cognitive perspective, this has been explained by the idea that the lack of linguistic skills of babies and toddlers limit their ability to mentally represent events; thereby, reducing their ability to encode memory. Moreover, even if infants do form such early memories, older children and adults may not be able to access them because they may be employing very different, more linguistically based, retrieval cues than infants used when forming the memory.

Language Development and Communication

Given the remarkable complexity of a language, one might expect that mastering a language would be an especially arduous task; indeed, for those of us trying to learn a second language as adults, this might seem to be true. However, young children master language very quickly with relative ease. B. F. Skinner (1957) proposed that language is learned through reinforcement. Noam Chomsky (1965) criticized this behaviorist approach, asserting instead that the mechanisms underlying language acquisition are biologically determined. The use of language develops in the absence of formal instruction and appears to follow a very similar pattern in children from vastly different cultures and backgrounds. It would seem, therefore, that we are born with a biological predisposition to acquire a language (Chomsky, 1965; Fernández & Cairns, 2011). Moreover, it appears that there is a critical period for language acquisition, such that this proficiency at acquiring language is maximal early in life; generally, as people age, the ease with which they acquire and master new languages diminishes (Johnson & Newport, 1989; Lenneberg, 1967; Singleton, 1995).

Stages of Language and Communication Development and Corresponding Age Range |

||

|

Stage |

Age |

Developmental Language and Communication |

|

1 |

0–3 months |

Reflexive communication |

|

2 |

3–8 months |

Reflexive communication; interest in others |

|

3 |

8–12 months |

Intentional communication; sociability |

|

4 |

12–18 months |

First words |

|

5 |

18–24 months |

Simple sentences of two words |

|

6 |

2–3 years |

Sentences of three or more words |

|

7 |

3–5 years |

Complex sentences; has conversations |

Each language has its own set of phonemes that are used to generate morphemes, words, and so on. Babies can discriminate among the sounds that make up a language (for example, they can tell the difference between the “s” in vision and the “ss” in fission); early on, they can differentiate between the sounds of all human languages, even those that do not occur in the languages that are used in their environments. However, by the time that they are about 1 year old, they can only discriminate among those phonemes that are used in the language or languages in their environments (Jensen, 2011; Werker & Lalonde, 1988; Werker & Tees, 1984).

WATCH THIS video below or online explaining some of the research surrounding language acquisition in babies, particularly those learning a second language:

Newborn Communication

Do newborns communicate? Certainly, they do. They do not, however, communicate with the use of language. Instead, they communicate their thoughts and needs with body posture (being relaxed or still), gestures, cries, and facial expressions. A person who spends adequate time with an infant can learn which cries indicate pain and which ones indicate hunger, discomfort, or frustration.

Intentional Vocalizations

Infants begin to vocalize and repeat vocalizations within the first couple of months of life. That gurgling, musical vocalization called cooing can serve as a source of entertainment to an infant who has been laid down for a nap or seated in a carrier on a car ride. Cooing serves as practice for vocalization. It also allows the infant to hear the sound of their own voice and try to repeat sounds that are entertaining. Infants also begin to learn the pace and pause of conversation as they alternate their vocalization with that of someone else and then take their turn again when the other person’s vocalization has stopped. Cooing initially involves making vowel sounds like “oooo.” Later, as the baby moves into babbling (see below), consonants are added to vocalizations such as “nananananana.

Babbling and Gesturing

Between 6 and 9 months, infants begin making even more elaborate vocalizations that include the sounds required for any language. Guttural sounds, clicks, consonants, and vowel sounds stand ready to equip the child with the ability to repeat whatever sounds are characteristic of the language heard. These babies repeat certain syllables (ma-ma-ma, da-da-da, ba-ba-ba), a vocalization called babbling because of the way it sounds. Eventually, these sounds will no longer be used as the infant grows more accustomed to a particular language. Deaf babies also use gestures to communicate wants, reactions, and feelings. Because gesturing seems to be easier than vocalization for some toddlers, sign language is sometimes taught to enhance one’s ability to communicate by making use of the ease of gesturing. The rhythm and pattern of language are used when deaf babies sign just as when hearing babies babble.

At around ten months of age, infants can understand more than they can say. You may have experienced this phenomenon as well if you have ever tried to learn a second language. You may have been able to follow a conversation more easily than to contribute to it.

Holophrasic Speech

Children begin using their first words at about 12 or 13 months of age and may use partial words to convey thoughts at even younger ages. These one-word expressions are referred to as holophrasic speech (holophrase). For example, the child may say “ju” for the word “juice” and use this sound when referring to a bottle. The listener must interpret the meaning of the holophrase. When this is someone who has spent time with the child, interpretation is not too difficult. They know that “ju” means “juice” which means the baby wants some milk! But, someone who has not been around the child will have trouble knowing what is meant. Imagine the parent who exclaims to a friend, “Ezra’s talking all the time now!” The friend hears only “ju da ga” which, the parent explains, means “I want some milk when I go with Daddy.”

Underextension

A child who learns that a word stands for an object may initially think that the word can be used for only that particular object. Only the family’s Irish Setter is a “doggie.” This is referred to as underextension. More often, however, a child may think that a label applies to all objects that are similar to the original object. In overextension, all animals become “doggies,” for example.

First words and cultural influences

First words for English-speaking children tend to be nouns. The child labels objects such as a cup or a ball. In a verb-friendly language such as Chinese, however, children may learn more verbs. This may also be due to the different emphasis given to objects based on culture. Chinese children may be taught to notice action and relationship between objects while children from the United States may be taught to name an object and its qualities (color, texture, size, etc.). These differences can be seen when comparing interpretations of art by older students from China and the United States.

Vocabulary growth spurt

One-year-olds typically have a vocabulary of about 50 words. But by the time they become toddlers, they have a vocabulary of about 200 words and begin putting those words together in telegraphic speech (short phrases). This language growth spurt is called the naming explosion because many early words are nouns (persons, places, or things).

Two-word sentences and telegraphic speech

Words are soon combined and 18-month-old toddlers can express themselves further by using phrases such as “baby bye-bye” or “doggie pretty.” Words needed to convey messages are used, but the articles and other parts of speech necessary for grammatical correctness are not yet included. These expressions sound like a telegraph (or perhaps a better analogy today would be that they read like a text message) where unnecessary words are not used. “Give baby ball” is used rather than “Give the baby the ball.” Or a text message of “Send money now!” rather than “Dear Mother. I really need some money to take care of my expenses.” You get the idea.

Child-directed speech

Why is a horse a “horsie”? Have you ever wondered why adults tend to use “baby talk” or that sing-song type of intonation and exaggeration used when talking to children? This represents a universal tendency and is known as child-directed speech or motherese or parentese. It involves exaggerating the vowel and consonant sounds, using a high-pitched voice, and delivering the phrase with great facial expression. Why is this done? It may be in order to clearly articulate the sounds of a word so that the child can hear the sounds involved. Or it may be because when this type of speech is used, the infant pays more attention to the speaker and this sets up a pattern of interaction in which the speaker and listener are in tune with one another. When I demonstrate this in class, the students certainly pay attention and look my way. Amazing! It also works in the college classroom!

WATCH THIS video below or online examining new research on infant-directed speech:

Theories of Language Development

How is language learned? Each major theory of language development emphasizes different aspects of language learning: that infants’ brains are genetically attuned to language, that infants must be taught, and that infants’ social impulses foster language learning. The first two theories of language development represent two extremes in the level of interaction required for language to occur (Berk, 2007).

Chomsky and the language acquisition device

This theory posits that infants teach themselves and that language learning is genetically programmed. The view is known as nativism and was advocated by Noam Chomsky, who suggested that infants are equipped with a neurological construct referred to as the language acquisition device (LAD), which makes infants ready for language. The LAD allows children, as their brains develop, to derive the rules of grammar quickly and effectively from the speech they hear every day. Therefore, language develops as long as the infant is exposed to it. No teaching, training, or reinforcement is required for language to develop. Instead, language learning comes from a particular gene, brain maturation, and the overall human impulse to imitate.

Skinner and reinforcement

This theory is the opposite of Chomsky’s theory because it suggests that infants need to be taught language. This idea arises from behaviorism. Learning theorist, B. F. Skinner, suggested that language develops through the use of reinforcement. Sounds, words, gestures, and phrases are encouraged by following the behavior with attention, words of praise, treats, or anything that increases the likelihood that the behavior will be repeated. This repetition strengthens associations, so infants learn the language faster as parents speak to them often. For example, when a baby says “ma-ma,” the mother smiles and repeats the sound while showing the baby attention. So, “ma-ma” is repeated due to this reinforcement.

Social pragmatics

Another language theory emphasizes the child’s active engagement in learning the language out of a need to communicate. Social impulses foster infant language because humans are social beings and we must communicate because we are dependent on each other for survival. The child seeks information, memorizes terms, imitates the speech heard from others, and learns to conceptualize using words as language is acquired. Tomasello & Herrmann (2010) argue that all human infants, as opposed to chimpanzees, seek to master words and grammar in order to join the social world [1] Many would argue that all three of these theories (Chomsky’s argument for nativism, conditioning, and social pragmatics) are important for fostering the acquisition of language (Berger, 2004).

Psychosocial Development and Attachment

Emotional Development

At birth, infants exhibit two emotional responses: attraction and withdrawal. They show attraction to pleasant situations that bring comfort, stimulation, and pleasure. And they withdraw from unpleasant stimulation such as bitter flavors or physical discomfort. At around two months, infants exhibit social engagement in the form of social smiling as they respond with smiles to those who engage their positive attention.

Pleasure is expressed as laughter at 3 to 5 months of age, and displeasure becomes more specific fear, sadness, or anger between ages 6 and 8 months. This fear is often associated with the presence of strangers or the departure of significant others known respectively as stranger wariness and separation anxiety which appear sometime between 6 and 15 months. And there is some indication that infants may experience jealousy as young as 6 months of age (Hart & Carrington, 2002).

Infants progress from reactive pain and pleasure to complex patterns of socioemotional awareness, which is a transition from basic instincts to learned responses. Fear is not always focused on things and events; it can also involve social responses and relationships. The fear is often associated with the presence of strangers or the departure of significant others known respectively as stranger wariness and separation anxiety, which appear sometime between 6 and 15 months. And there is even some indication that infants may experience jealousy as young as 6 months of age (Hart & Carrington, 2002).

Stranger wariness actually indicates that brain development and increased cognitive abilities have taken place. As an infant’s memory develops, they are able to separate the people that they know from the people that they do not. The same cognitive advances allow infants to respond positively to familiar people and recognize those that are not familiar. Separation anxiety also indicates cognitive advances and is universal across cultures. Due to the infant’s increased cognitive skills, they are able to ask reasonable questions like “Where is my caregiver going?” “Why are they leaving?” or “Will they come back?” Separation anxiety usually begins around 7-8 months and peaks around 14 months, and then decreases. Both stranger wariness and separation anxiety represent important social progress because they not only reflect cognitive advances but also growing social and emotional bonds between infants and their caregivers.

As we will learn through the rest of this module, caregiving does matter in terms of infant emotional development and emotional regulation. Emotional regulation can be defined by two components: emotions as regulating and emotions as regulated. The first, “emotions as regulating,” refers to changes that are elicited by activated emotions (e.g., a child’s sadness eliciting a change in parent response). The second component is labeled “emotions as regulated,” which refers to the process through which the activated emotion is itself changed by deliberate actions taken by the self (e.g., self-soothing, distraction) or others (e.g., comfort).

Throughout infancy, children rely heavily on their caregivers for emotional regulation; this reliance is labeled co-regulation, as parents and children both modify their reactions to the other based on the cues from the other. Caregivers use strategies such as distraction and sensory input (e.g., rocking, stroking) to regulate infants’ emotions. Despite their reliance on caregivers to change the intensity, duration, and frequency of emotions, infants are capable of engaging in self-regulation strategies as young as 4 months old. At this age, infants intentionally avert their gaze from overstimulating stimuli. By 12 months, infants use their mobility in walking and crawling to intentionally approach or withdraw from stimuli.

Throughout toddlerhood, caregivers remain important for the emotional development and socialization of their children, through behaviors such as labeling their child’s emotions, prompting thought about emotion (e.g., “why is the turtle sad?”), continuing to provide alternative activities/distractions, suggesting coping strategies, and modeling coping strategies. Caregivers who use such strategies and respond sensitively to children’s emotions tend to have children who are more effective at emotion regulation, are less fearful and fussy, more likely to express positive emotions, easier to soothe, more engaged in environmental exploration, and have enhanced social skills in the toddler and preschool years.

Self-awareness

During the second year of life, children begin to recognize themselves as they gain a sense of the self as an object. The realization that one’s body, mind, and activities are distinct from those of other people is known as self-awareness (Kopp, 2011).[2] The most common technique used in research for testing self-awareness in infants is a mirror test known as the “Rouge Test.” The rouge test works by applying a dot of rouge (colored makeup) on an infant’s face and then placing them in front of the mirror. If the infant investigates the dot on their nose by touching it, they are thought to realize their own existence and have achieved self-awareness. A number of research studies have used this technique and shown self-awareness to develop between 15 and 24 months of age. Some researchers also take language such as “I, me, my, etc.” as an indicator of self-awareness.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions on Self-Awareness and the Shopping Cart study:

Cognitive psychologist Philippe Rochat (2003) described a more in-depth developmental path in acquiring self-awareness through various stages. He described self-awareness as occurring in five stages beginning from birth.

|

Stages of acquiring self-awareness |

|

|

Stage |

Description |

|

Stage 1 – Differentiation (from birth) |

Right from birth infants are able to differentiate the self from the non-self. A study using the infant rooting reflex found that infants rooted significantly less from self-stimulation, contrary to when the stimulation came from the experimenter. |

|

Stage 2 – Situation (by 2 months) |

In addition to differentiation, infants at this stage can also situate themselves in relation to a model. In one experiment infants were able to imitate tongue orientation from an adult model. Additionally, another sign of differentiation is when infants bring themselves into contact with objects by reaching for them. |

|

Stage 3 – Identification (by 2 years) |

At this stage, the more common definition of “self-awareness” comes into play, where infants can identify themselves in a mirror through the “rouge test” as well as begin to use language to refer to themselves. |

|

Stage 4 – Permanence |

This stage occurs after infancy when children are aware that their sense of self continues to exist across both time and space. |

|

Stage 5 – Self-consciousness or meta-self-awareness |

This also occurs after infancy. This is the final stage when children can see themselves in 3rd person, or how they are perceived by others. |

Once a child has achieved self-awareness, the child is moving toward understanding social emotions such as guilt, shame or embarrassment, and pride, as well as sympathy and empathy. These will require an understanding of the mental state of others which is acquired around age 3 to 5 year of age.

Attachment

Psychosocial development occurs as children form relationships, interact with others, and understand and manage their feelings. In social and emotional development, forming healthy attachments is very important and is the major social milestone of infancy. Attachment is a long-standing connection or bond with others. Developmental psychologists are interested in how infants reach this milestone. They ask such questions as: How do parent and infant attachment bonds form? How does neglect affect these bonds? What accounts for children’s attachment differences?

Researchers Harry Harlow, John Bowlby, and Mary Ainsworth conducted studies designed to answer these questions. In the 1950s, Harlow conducted a series of experiments on monkeys. He separated newborn monkeys from their mothers. Each monkey was presented with two surrogate mothers. One surrogate mother was made out of wire mesh, and she could dispense milk. The other surrogate mother was softer and made from cloth: This monkey did not dispense milk. Research shows that the monkeys preferred the soft, cuddly cloth monkey, even though she did not provide any nourishment. The baby monkeys spent their time clinging to the cloth monkey and only went to the wire monkey when they needed to be feed. Prior to this study, the medical and scientific communities generally thought that babies become attached to the people who provide their nourishment. However, Harlow (1958) concluded that there was more to the mother-child bond than nourishment. Feelings of comfort and security are the critical components of maternal-infant bonding, which leads to healthy psychosocial development.

WATCH THIS video clip below or online with captions showing the classic Harlow monkey study:

Building on the work of Harlow and others, John Bowlby developed the concept of attachment theory. He defined attachment as the affectional bond or tie that an infant forms with the mother (Bowlby, 1969). He believed that an infant must form this bond with a primary caregiver in order to have normal social and emotional development. In addition, Bowlby proposed that this attachment bond is very powerful and continues throughout life. He used the concept of a secure base to define a healthy attachment between parent and child (1988). A secure base is a parental presence that gives children a sense of safety as they explore their surroundings. Bowlby said that two things are needed for a healthy attachment: The caregiver must be responsive to the child’s physical, social, and emotional needs; and the caregiver and child must engage in mutually enjoyable interactions (Bowlby, 1969).

While Bowlby thought attachment was an all-or-nothing process, Mary Ainsworth’s (1970) research showed otherwise. Ainsworth wanted to know if children differ in the ways they bond, and if so, how. To find the answers, she used the Strange Situation procedure to study attachment between mothers and their infants (1970). In the Strange Situation, the mother (or primary caregiver) and the infant (age 12-18 months) are placed in a room together. There are toys in the room, and the caregiver and child spend some time alone in the room. After the child has had time to explore their surroundings, a stranger enters the room. The mother then leaves her baby with the stranger. After a few minutes, she returns to comfort her child. Based on how the toddlers responded to the separation and reunion, Ainsworth identified three types of parent-child attachments: secure, avoidant, and resistant (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970). A fourth style, known as disorganized attachment, was later described (Main & Solomon, 1990).

Types of Attachment

The most common type of attachment—also considered the healthiest—is called secure attachment. In this type of attachment, the toddler prefers their parent over a stranger. The attachment figure is used as a secure base to explore the environment and is sought out in times of stress. Securely attached children were distressed when their caregivers left the room in the Strange Situation experiment, but when their caregivers returned, the securely attached children were happy to see them. Securely attached children have caregivers who are sensitive and responsive to their needs.

With avoidant attachment, the child is unresponsive to the parent, does not use the parent as a secure base, and does not care if the parent leaves. The toddler reacts to the parent the same way they react to a stranger. When the parent does return, the child is slow to show a positive reaction. Ainsworth theorized that these children were most likely to have a caregiver who was insensitive and inattentive to their needs (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

In cases of resistant attachment, children tend to show clingy behavior, but then they reject the attachment figure’s attempts to interact with them (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970). These children do not explore the toys in the room, appearing too fearful. During separation in the Strange Situation, they become extremely disturbed and angry with the parent. When the parent returns, the children are difficult to comfort. Resistant attachment is thought to be the result of the caregivers’ inconsistent level of response to their child.

Finally, children with disorganized attachment behaved oddly in the Strange Situation. They freeze, run around the room in an erratic manner, or try to run away when the caregiver returns (Main & Solomon, 1990). This type of attachment is seen most often in kids who have been abused or severely neglected. Research has shown that abuse disrupts a child’s ability to regulate their emotions.

While Ainsworth’s research has found support in subsequent studies, it has also met criticism. Some researchers have pointed out that a child’s temperament (which we discuss next) may have a strong influence on attachment (Gervai, 2009; Harris, 2009), and others have noted that attachment varies from culture to culture, a factor that was not accounted for in Ainsworth’s research (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2000; van Ijzendoorn & Sagi-Schwartz, 2008).

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions to better understand Mary Ainsworth’s research and to see examples of how she conducted the experiment: