15 Module 15: Developmental Challenges and Psychopathologies Across the Lifespan

Module 15 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Define Psychological Disorders

Explain the criteria for psychological disorders, including atypical, distressful, dysfunctional, and dangerous behaviors. - Understand Cultural Contexts

Discuss how cultural expectations influence the identification and perception of psychological disorders. - Examine Theories of Psychopathology

Compare key theories of psychopathology, including the harmful dysfunction model and the DSM-5 definition. - Understand the DSM-5

Describe the purpose and structure of the DSM-5 and its role in diagnosing psychological disorders. - Identify Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Explain the features and impacts of neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder and ADHD. - Discuss Learning Disabilities

Summarize the characteristics of specific learning disorders, including dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia. - Analyze Motor Disorders

Explain the symptoms and management of motor disorders, such as developmental coordination disorder and Tourette’s syndrome. - Understand Anxiety Disorders

Identify common anxiety disorders and their developmental trajectories across the lifespan. - Examine Mood Disorders

Discuss the features and prevalence of mood disorders, such as major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. - Explore Trauma-Related Disorders

Summarize the symptoms, risk factors, and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). - Discuss Eating Disorders

Compare the characteristics of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. - Understand Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

Explain the features and impacts of OCD, body dysmorphic disorder, and hoarding disorder. - Analyze the Developmental Perspective

Discuss the importance of a developmental perspective in understanding the onset and progression of psychological disorders. - Evaluate Mental Health in Older Adults

Identify common mental health challenges in older adults, such as depression and anxiety, and their unique impacts. - Recognize the Role of Social Support

Explain how social support influences mental health outcomes and recovery from psychological disorders. - Analyze Common Myths Related to Mental Illness

Use concepts of developmental psychopathology to analyze common common myths related to mental illness.

What are Psychological Disorders?

A psychological disorder is a condition characterized by abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Psychopathology is the study of psychological disorders, including their symptoms, etiology (i.e., their causes), and treatment. The term psychopathology can also refer to the manifestation of a psychological disorder. Although consensus can be difficult, it is extremely important for mental health professionals to agree on what kinds of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are truly abnormal in the sense that they genuinely indicate the presence of psychopathology. Certain patterns of behavior and inner experience can easily be labeled as abnormal and clearly signify some kind of psychological disturbance.

The person who washes his hands 40 times per day and the person who claims to hear the voices of demons exhibit behaviors and inner experiences that most would regard as abnormal: beliefs and behaviors that suggest the existence of a psychological disorder. But, consider the nervousness a young man feels when talking to attractive women or the loneliness and longing for home a freshman experiences during her first semester of college—these feelings may not be regularly present, but they fall in the range of normal. So, what kinds of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors represent a true psychological disorder?

Definition of a Psychological Disorder

Perhaps the simplest approach to conceptualizing psychological disorders is to label behaviors, thoughts, and inner experiences that are atypical, distressful, dysfunctional, and sometimes even dangerous, as signs of a disorder. For example, if you ask a classmate for a date and you are rejected, you probably would feel a little dejected. Such feelings would be normal. If you felt extremely depressed—so much so that you lost interest in activities, had difficulty eating or sleeping, felt utterly worthless, and contemplated suicide—your feelings would be atypical, would deviate from the norm, and could signify the presence of a psychological disorder. Just because something is atypical, however, does not necessarily mean it is disordered.

Consider a person who has an unconventional sleep schedule, such as staying awake during the night and sleeping during the day. While this sleep pattern might be atypical compared to the societal norm of sleeping at night, it doesn’t necessarily indicate a sleep disorder. This person might simply have a job that requires nighttime hours or have personal preferences that lead them to be more active at night. Thus, the atypical sleep schedule in this case isn’t indicative of a disorder but rather a lifestyle choice or necessity. Just because something is atypical, however, does not necessarily mean it is disordered.

If we can agree that merely being atypical is an insufficient criterion for a having a psychological disorder, is it reasonable to consider behavior or inner experiences that differ from widely expected cultural values or expectations as disordered? Using this criterion, a woman who walks around a subway platform wearing a heavy winter coat in July while screaming obscenities at strangers may be considered as exhibiting symptoms of a psychological disorder. Her actions and clothes violate socially accepted rules governing appropriate dress and behavior; these characteristics are atypical.

Cultural Expectations

Violating cultural expectations is not, in and of itself, a satisfactory means of identifying the presence of a psychological disorder. Since behavior varies from one culture to another, what may be expected and considered appropriate in one culture may not be viewed as such in other cultures. For example, returning a stranger’s smile is expected in the United States because a pervasive social norm dictates that we reciprocate friendly gestures. A person who refuses to acknowledge such gestures might be considered socially awkward—perhaps even disordered—for violating this expectation.

However, such expectations are not universally shared. Cultural expectations in Japan involve showing reserve, restraint, and a concern for maintaining privacy around strangers. Japanese people are generally unresponsive to smiles from strangers (Patterson et al., 2007). Eye contact provides another example. In the United States and Europe, eye contact with others typically signifies honesty and attention. However, most Latin-American, Asian, and African cultures interpret direct eye contact as rude, confrontational, and aggressive (Pazain, 2010). Thus, someone who makes eye contact with you could be considered appropriate and respectful or brazen and offensive, depending on your culture.

Hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that are not physically present) in Western societies is a violation of cultural expectations, and a person who reports such inner experiences is readily labeled as psychologically disordered. In other cultures, visions that, for example, pertain to future events may be regarded as normal experiences that are positively valued. Finally, it is important to recognize that cultural norms change over time: what might be considered typical in a society at one time may no longer be viewed this way later, similar to how fashion trends from one era may elicit quizzical looks decades later—imagine how a headband, legwarmers, and the big hair of the 1980s would go over on your campus today.

THINK ABOUT THIS: Identify a behavior that is considered unusual or abnormal in your own culture; however, it would be considered normal and expected in another culture.

Harmful Dysfunction

If none of the criteria discussed so far is adequate by itself to define the presence of a psychological disorder, how can a disorder be conceptualized? Many efforts have been made to identify the specific dimensions of psychological disorders, yet none is entirely satisfactory. No universal definition of psychological disorder exists that can apply to all situations in which a disorder is thought to be present (Zachar & Kendler, 2007). However, one of the more influential conceptualizations was proposed by Wakefield (1992), who defined psychological disorder as a harmful dysfunction.

Wakefield argued that natural internal mechanisms—that is, psychological processes honed by evolution, such as cognition, perception, and learning—have important functions, such as enabling us to experience the world the way others do and to engage in rational thought, problem solving, and communication. For example, learning allows us to associate a fear with a potential danger in such a way that the intensity of fear is roughly equal to the degree of actual danger. Dysfunction occurs when an internal mechanism breaks down and can no longer perform its normal function. But, the presence of a dysfunction by itself does not determine a disorder. The dysfunction must be harmful in that it leads to negative consequences for the individual or for others, as judged by the standards of the individual’s culture. The harm may include significant internal anguish (e.g., high levels of anxiety or depression) or problems in day-to-day living (e.g., in one’s social or work life).

To illustrate, Janet has an extreme fear of spiders. Janet’s fear might be considered a dysfunction in that it signals that the internal mechanism of learning is not working correctly (i.e., a faulty process prevents Janet from appropriately associating the magnitude of her fear with the actual threat posed by spiders). Janet’s fear of spiders has a significant negative influence on her life: she avoids all situations in which she suspects spiders to be present (e.g., the basement or a friend’s home), and she quit her job last month because she saw a spider in the restroom at work and is now unemployed.

According to the harmful dysfunction model, Janet’s condition would signify a disorder because (a) there is a dysfunction in an internal mechanism, and (b) the dysfunction has resulted in harmful consequences. Similar to how the symptoms of physical illness reflect dysfunctions in biological processes, the symptoms of psychological disorders presumably reflect dysfunctions in mental processes. The internal mechanism component of this model is especially appealing because it implies that disorders may occur through a breakdown of biological functions that govern various psychological processes, thus supporting contemporary neurobiological models of psychological disorders (Fabrega, 2007).

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Definition

Many of the features of the harmful dysfunction model are incorporated in a formal definition of psychological disorder developed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). According to the APA (2013), a psychological disorder is a condition that is said to consist of the following:

There are significant disturbances in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. A person must experience inner states (e.g., thoughts and/or feelings) and exhibit behaviors that are clearly disturbed—that is, unusual, but in a negative, self-defeating way. Often, such disturbances are troubling to those around the individual who experiences them. For example, an individual who is uncontrollably preoccupied by thoughts of germs spends hours each day bathing, has inner experiences, and displays behaviors that most would consider atypical and negative (disturbed) and that would likely be troubling to family members.

The disturbances reflect some kind of biological, psychological, or developmental dysfunction. Disturbed patterns of inner experiences and behaviors should reflect some flaw (dysfunction) in the internal biological, psychological, and developmental mechanisms that lead to normal, healthy psychological functioning. For example, the hallucinations observed in schizophrenia could be a sign of brain abnormalities.

The disturbances lead to significant distress or disability in one’s life. A person’s inner experiences and behaviors are considered to reflect a psychological disorder if they cause the person considerable distress, or greatly impair his ability to function as a normal individual (often referred to as functional impairment, or occupational and social impairment). As an illustration, a person’s fear of social situations might be so distressing that it causes the person to avoid all social situations (e.g., preventing that person from being able to attend class or apply for a job).

The disturbances do not reflect expected or culturally approved responses to certain events. Disturbances in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors must be socially unacceptable responses to certain events that often happen in life. For example, it is perfectly natural (and expected) that a person would experience great sadness and might wish to be left alone following the death of a close family member. Because such reactions are in some ways culturally expected, the individual would not be assumed to signify a mental disorder.

Some believe that there is no essential criterion or set of criteria that can definitively distinguish all cases of disorder from nondisorder (Lilienfeld & Marino, 1999). In truth, no single approach to defining a psychological disorder is adequate by itself, nor is there universal agreement on where the boundary is between disordered and not disordered. From time to time we all experience anxiety, unwanted thoughts, and moments of sadness; our behavior at other times may not make much sense to ourselves or to others. These inner experiences and behaviors can vary in their intensity, but are only considered disordered when they are highly disturbing to us and/or others, suggest a dysfunction in normal mental functioning, and are associated with significant distress or disability in social or occupational activities.

Summary

Psychological disorders are conditions characterized by abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Although challenging, it is essential for psychologists and mental health professionals to agree on what kinds of inner experiences and behaviors constitute the presence of a psychological disorder. Inner experiences and behaviors that are atypical or violate social norms could signify the presence of a disorder; however, each of these criteria alone is inadequate. Harmful dysfunction describes the view that psychological disorders result from the inability of an internal mechanism to perform its natural function. Many of the features of harmful dysfunction conceptualization have been incorporated in the APA’s formal definition of psychological disorders. According to this definition, the presence of a psychological disorder is signaled by significant disturbances in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; these disturbances must reflect some kind of dysfunction (biological, psychological, or developmental), must cause significant impairment in one’s life, and must not reflect culturally expected reactions to certain life events.

Diagnosing and Classifying Psychological Disorders

A first step in the study of psychological disorders is carefully and systematically discerning significant signs and symptoms. How do mental health professionals ascertain whether or not a person’s inner states and behaviors truly represent a psychological disorder? Arriving at a proper diagnosis—that is, appropriately identifying and labeling a set of defined symptoms—is absolutely crucial. This process enables professionals to use a common language with others in the field and aids in communication about the disorder with the patient, colleagues and the public. A proper diagnosis is an essential element to guide proper and successful treatment. For these reasons, classification systems that organize psychological disorders systematically are necessary.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

Although a number of classification systems have been developed over time, the one that is used by most mental health professionals in the United States is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013).

The first edition of the DSM, published in 1952, classified psychological disorders according to a format developed by the U.S. Army during World War II (Clegg, 2012). In the years since, the DSM has undergone numerous revisions and editions. The most recent edition, published in 2022, is the DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022). This is the fifth edition and the “TR” means the editors revised the text of the book- updating things like prevalence statistics and research into etiology and treatment- but did not revise any of the disorder criteria in 2022). The DSM-5-TR includes many categories of disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and dissociative disorders).

CLICK THIS: Learn more about the DSM-5 at the APA’s website devoted to it. You can check out fact sheets, view FAQs, and much more.

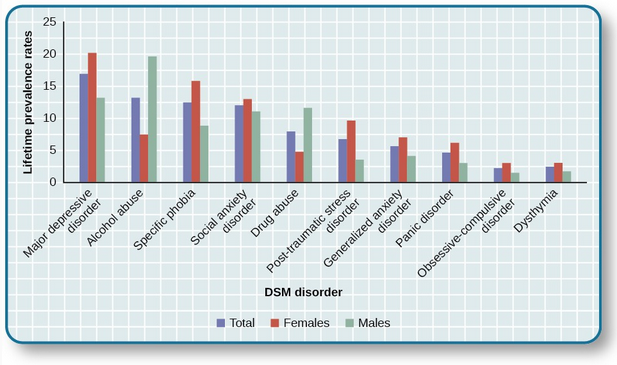

Each disorder is described in detail, including an overview of the disorder (diagnostic features), specific symptoms required for diagnosis (diagnostic criteria), prevalence information (what percent of the population is thought to be afflicted with the disorder), and risk factors associated with the disorder. It shows lifetime prevalence rates—the percentage of people in a population who develop a disorder in their lifetime—of various psychological disorders among U.S. adults. These data were based on a national sample of 9,282 U.S. residents (National Comorbidity Survey, 2007).

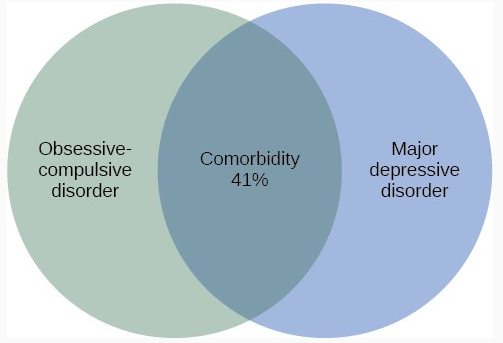

The DSM-5 also provides information about comorbidity; the co-occurrence of two disorders. For example, the DSM-5 mentions that 41% of people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) also meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Drug use is highly comorbid with other mental illnesses; 6 out of 10 people who have a substance use disorder also suffer from another form of mental illness.

The DSM has changed considerably in the half-century since it was originally published. The first two editions of the DSM, for example, listed homosexuality as a disorder; however, in 1973, the APA voted to remove it from the manual (Silverstein, 2009). Additionally, beginning with the DSM-III in 1980, mental disorders have been described in much greater detail, and the number of diagnosable conditions has grown steadily, as has the size of the manual itself. DSM-I included 106 diagnoses and was 130 total pages, whereas DSM-III included more than 2 times as many diagnoses (265) and was nearly seven times its size (886 total pages) (Mayes & Horowitz, 2005). Although DSM-5 is longer than DSM-IV, the volume includes only 237 disorders, a decrease from the 297 disorders that were listed in DSM-IV. The latest edition, DSM-5, includes revisions in the organization and naming of categories and in the diagnostic criteria for various disorders (Regier, Kuhl, & Kupfer, 2012), while emphasizing careful consideration of the importance of gender and cultural difference in the expression of various symptoms (Fisher, 2010).

Some believe that establishing new diagnoses might overpathologize the human condition by turning common human problems into mental illnesses (The Associated Press, 2013). Indeed, the finding that nearly half of all Americans will meet the criteria for a DSM disorder at some point in their life (Kessler et al., 2005) likely fuels much of this skepticism. The DSM-5 is also criticized on the grounds that its diagnostic criteria have been loosened, thereby threatening to “turn our current diagnostic inflation into diagnostic hyperinflation” (Frances, 2012, para. 22). For example, DSM-IV specified that the symptoms of major depressive disorder must not be attributable to normal bereavement (loss of a loved one). The DSM-5, however, has removed this bereavement exclusion, essentially meaning that grief and sadness after a loved one’s death can constitute major depressive disorder.

LISTEN TO THIS: Podcast titled 81 Words: The story of how the American Psychiatric Association decided in 1973 that homosexuality was no longer a mental illness:

The International Classification of Diseases

A second classification system, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), is also widely recognized. Published by the World Health Organization (WHO), the ICD was developed in Europe shortly after World War II and, like the DSM, has been revised several times. The categories of psychological disorders in both the DSM and ICD are similar, as are the criteria for specific disorders; however, some differences exist. Although the ICD is used for clinical purposes, this tool is also used to examine the general health of populations and to monitor the prevalence of diseases and other health problems internationally (WHO, 2013). The ICD is in its 10th edition (ICD-10); however, efforts are now underway to develop a new edition (ICD-11) that, in conjunction with the changes in DSM-5, will help harmonize the two classification systems as much as possible (APA, 2013).

A study that compared the use of the two classification systems found that worldwide the ICD is more frequently used for clinical diagnosis, whereas the DSM is more valued for research (Mezzich, 2002). Most research findings concerning the etiology and treatment of psychological disorders are based on criteria set forth in the DSM (Oltmanns & Castonguay, 2013). The DSM also includes more explicit disorder criteria, along with an extensive and helpful explanatory text (Regier et al., 2012). The DSM is the classification system of choice among U.S. mental health professionals, and this chapter is based on the DSM paradigm.

The Compassionate View of Psychological Disorders

As these disorders are outlined, please bear two things in mind. First, remember that psychological disorders represent extremes of inner experience and behavior. If, while reading about these disorders, you feel that these descriptions begin to personally characterize you, do not worry—Each of us experiences episodes of sadness, anxiety, and preoccupation with certain thoughts. These episodes should not be considered problematic unless the accompanying thoughts and behaviors become extreme and have a disruptive effect on one’s life. Second, understand that people with psychological disorders are far more than just embodiments of their disorders.

We do not use terms such as schizophrenics, depressives, or phobics because they are labels that objectify people who suffer from these conditions, thus promoting biased and disparaging assumptions about them. It is important to remember that a psychological disorder is not what a person is; it is something that a person has. As is the case with cancer or diabetes, those with psychological disorders suffer debilitating, often painful conditions that are not of their own choosing. These individuals deserve to be viewed and treated with compassion, understanding, and dignity.

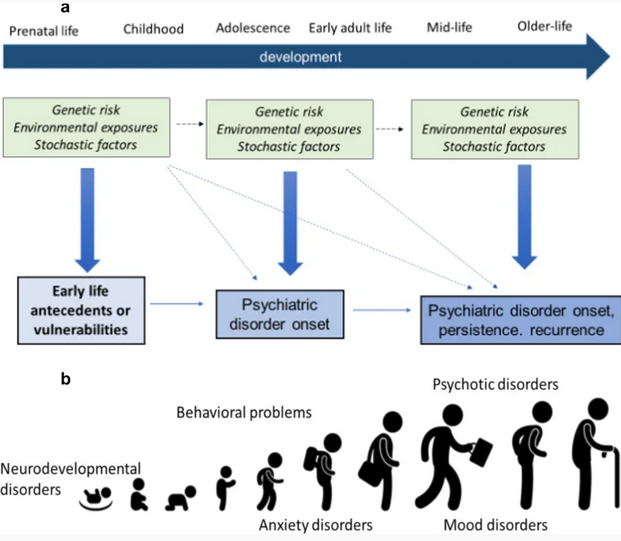

The Importance of a Developmental Perspective in Psychiatry

It is well recognized that physical, behavioral, brain, and biological phenotypes are subject to changes across the life span and that such transformation is especially marked during fetal life, childhood, and adolescence. Many of these changes are normative and arise as a result of typical developmental processes (e.g., an increase in height during childhood); others represent departures from a typical developmental trajectory (e.g., a shift from the 50th to 5th centile on a childhood height centile chart). There is growing appreciation from biological, imaging, genetic, and clinical studies that a developmental perspective is important for investigating psychiatric disorders. However, clinical practice and sometimes research, especially in an era when very large sample sizes need to be amassed, often ignore the developmental context. That is because investigating developmental processes and taking a life-course perspective typically require longitudinal investigations that are time consuming and expensive (Thapar & Riglin, 2020, p. 1).

Around 75% of psychiatric disorders onset by childhood, adolescence, or early adult life (mid-20s). Thus, it can be argued that investigation into risk and protective exposures, risk mechanisms, as well as prevention and early intervention programs needs to start very early in life. Also, the peak age of incidence for many psychiatric disorders, such as depression, coincides with the transition from “childhood/adolescence” to “adult” life. The sharp divide between child/adolescent and adult psychiatry research and clinical services is unhelpful here and can be a barrier to adopting a developmental approach (Thapar & Riglin, 2020, p. 1).

Although there is a growing recognition that different neuropsychiatric disorders show strong phenotypic and genetic overlap with each other, they are also distinctive in many respects. An obvious difference is that they display varying times of onset or at least manifest at different times although what explains this variation is unknown at present. One possibility is that the timing of exposure to a risk factor (e.g., prenatal life vs. adolescence) matters. Also, risk factors vary across the life course. For example, hormonal changes associated with puberty are likely to have greatest impact in adolescence, a time period when the incidence of depression rises. Other stressors also change across development—such as family or school stressors in childhood, employment-related stress in adulthood, and chronic illness in the elderly (Thapar & Riglin, 2020, p. 1).

Neurodevelopmental disorders as grouped by DSM-5 include autism, ADHD, learning, communication and motor disorders, and intellectual disability, and are defined as having an onset in the early developmental period, typically in early childhood. They tend to have a steady rather than remitting and relapsing course and their core features show marked maturational changes from childhood to adult life. It is now recognized that these disorders, or at least some symptoms and impairment, persist well into adult life for many (Thapar & Riglin, 2020, p. 1).

It has been long recognized that conduct disorder shows distinctive developmental courses. Childhood-onset persistent conduct problems begin early and are strongly associated with neurocognitive deficits, ADHD, a higher genetic loading, and poorer prognosis. In some regards, this group appear to share many similarities with neurodevelopmental disorders: early onset, many but not all show a chronic life-course trajectory, prominent neurocognitive deficits, and a male excess. Another group show an emergence of conduct problem after puberty. Individuals in this group do not show an elevated rate of ADHD or cognitive deficits, which tend to improve in adult life, and the social/peer context is thought to contribute risk in this group. A developmental approach enabled these different groups to be identified, yet clinical research of adolescent conduct disorder would group them as a single entity. Childhood-onset (<10 years) and adolescent-onset behavioral problems however are distinguished as subtypes in DSM-5 (Thapar & Riglin, 2020, p. 1).

The typical timing for the onset of anxiety disorders depends to a large extent on the type of anxiety problem. For example, separation anxiety and specific phobias typically onset in childhood; social anxiety disorder more commonly arises in childhood and adolescence, and agoraphobia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder most commonly manifest in later adolescence or early adulthood. Symptoms of some anxiety disorders are developmentally normative at a young age (e.g., separation anxiety in toddlers). As for neurodevelopmental disorders, symptoms of anxiety disorder need to be assessed with a developmental view but there is no clear-cut guidance on how best to do this (Thapar & Riglin, 2020, p. 1).

Mood disorders and schizophrenia typically rise in incidence from late adolescence onwards and are rare in prepubertal children. However, longitudinal, population-based studies as well as investigation of high-risk offspring of parents with depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia have shown that these disorders are commonly preceded by earlier mental health problems such as anxiety, irritability, or mild hypomania.

READ THIS: For more information about how developmental trajectories influence mental health and illness, read the journal article “The importance of a developmental perspective in Psychiatry: what do recent genetic-epidemiological findings show?“

Mental Health in Infancy and Toddlerhood

While it is widely accepted that we are in the midst of a mental health crisis for young people, what is often missed is that the precursors of mental health challenges can begin as early as the perinatal period and also in early infancy (Robinson et al., 2008). This makes the infant and early childhood period a crucial window for intervention, with the goal of promoting good mental health for infants and young children (Robinson et al., 2008).

Good mental health in infancy and toddlerhood refers to healthy social and emotional development. It includes a child’s ability to experience, regulate and express emotions, to develop close and secure interpersonal relationships, and to explore the environment and learn (Clinton, Feller & Williams, 2016). All of these capacities develop best within the context of a caregiving environment that includes family, community, and cultural expectations for young children (Parlakian & Seibel, 2002).

Research has established that infants and toddlers can suffer from mental health disorders that require treatment in their own right (Warner & Pottick, 2006; Zero to Three, 2012). Difficulties in infancy include regulatory disturbances such as excessive crying, sleeping or feeding difficulties and attachment difficulties (Postert et al., 2012; Zero to Three, 2016). Early childhood mental health problems include externalizing behaviors such as aggression and oppositional defiance (Egger & Angold, 2006; Loeber et al., 2009), and internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression.

Several epidemiological studies have determined the prevalence of mental health disorders in infants and young children, indicating a 16% to 18% prevalence of mental health disorders amongst children between 1 to 5 years of age, with approximately half of these children being severely impacted (von Klitzing, Döhnert, Kroll & Grube, 2015).

One study found that almost 35% of children between 12 to 18 months of age scored high on the Problem Scale of the Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA) (Horwitz et al., 2013), while another study found that by 18 months of age, 16% to 18% of children met criteria for one or more diagnoses of a mental health or developmental disorder (Skovgaard et al., 2007). Similar results were reported by an Australian study, which found that by 2 years of age, 12% of children had clinically significant emotional, behavioral, or social problems in the context of caregiver-child relationship disturbance (Bayer et al., 2011). In addition to this, a different Australian study found that by age five, 20% of the children studied had clinically significant behavioral problems (Robinson et al., 2008). It is important to recognize that most recent epidemiological studies have been conducted in developed, economically stable, peaceful countries (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2017). Evidence suggests that rates of mental health difficulties may be much higher in countries where extreme poverty, war, family displacement and trauma exist (Tomlinson et al., 2014).

If not treated, mental health difficulties that begin early in life can become more serious over time, and can persist into adolescence and adulthood. Children with mental health problems are at higher risk for later difficulties at school, difficulties with peers, difficulty participating in employment, drug and alcohol problems, relationship breakdown, family violence, criminal activity, juvenile delinquency and suicide.

READ THIS: Infants have mental health needs, too. “Many new caregivers ― moms, dads, grandparents and foster parents ― can experience normal challenges with their infants. When challenges become persistent or apparently unchangeable, caregivers can experience anxiety and frustration themselves. Seeking support with an expert in infant and early childhood development can provide helpful strategies to reduce stress for everyone involved (Stygar & Zadroga, 2021).”

Mental Health in Early Childhood & Adolescence

Early childhood mental health (birth to 5 years) is a child’s growing capacity to do these things, all in the cultural context of family and community (adapted from ZERO TO THREE):

- Experience, regulate, and express emotions

- Develop close, secure, relationships

- Explore the surroundings and learn.

Early childhood mental health is the same as social emotional development. Social and emotional development is important to early learning. Many social-emotional qualities—such as curiosity; self-confidence as a learner; self-control of attention, thinking, and impulses; and initiative in developing new ideas—are essential to learning at any age. Learning, problem solving, and creativity rely on these social-emotional and motivational qualities as well as basic cognitive skills.

Following with the CDC, mental disorders among children are described as serious changes in the way children typically learn, behave, or handle their emotions, which cause distress and problems getting through the day. Many children occasionally experience fears and worries or display disruptive behaviors. If symptoms are serious and persistent and interfere with school, home, or play activities, the child may be diagnosed with a mental disorder.

Among the more common mental disorders that can be diagnosed in childhood are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety (fears or worries), and behavior disorders.

Adolescent Mental Health

The consequences of mental illness in children and adolescents can be substantial. Many mental health professionals speak of accrued deficits that occur when mental illness in children is not treated. To begin with, mental illness can impair a student’s ability to learn. Adolescents whose mental illness is not treated rapidly and aggressively tend to fall further and further behind in school. They are more likely to drop out of school and are less likely to be fully functional members of society when they reach adulthood. We also now know that depressive disorders in young people confer a higher risk for illness and interpersonal and psychosocial difficulties that persist after the depressive episode is over. Furthermore, many adults who suffer from mental disorders have problems that originated in childhood. Depression in youth may predict more severe illness in adult life. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, once thought to affect children and adolescents only, may persist into adulthood and may be associated with social, legal, and occupational problems. Mental illness impairs a student’s ability to learn. Adolescents whose mental illness is not treated rapidly and aggressively tend to fall further and further behind in school.

The most commonly diagnosed mental health disorders in children aged 13-17 years are attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety problems, behavioral problems, and depression:

- ADHD: 9.8% (approximately 6.0 million)

- Anxiety: 9.4% (approximately 5.8 million)

- Behavioral problems: 8.9% (approximately 5.5 million)

- Depression: 4.4% (approximately 2.7 million)

For adolescents, depression, substance use, and suicide are important concerns. The following statistics demonstrate these concerns in adolescents aged 12-17 years in 2018-2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic:

- 36.7% had persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness.

- 18.8% seriously considered attempting suicide; 8.9% attempted suicide.

- 15.1% had a major depressive episode.

- 4.1% had a substance use disorder.

- 1.6% had an alcohol use disorder.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found an 8% increase in persistent feelings of sadness in youth.

For an introduction to how mental illness differs between adolescents and adults, read the article below.

CLICK THIS: Learn more about how symptoms of mental illness can look different in teens than adults by reading this blog post from paradigmtreatment.com. “Parents and caregivers of teens should also keep in mind that adolescence is a time of great change, including physical, mental, social and emotional changes. It is also a time when the onset of certain mental illnesses can occur. Sadly, some of these illnesses can impact an individual’s lifelong into adulthood. Because of this vulnerable time, it’s important to be familiar with the signs and conditions of a teen mental illness in order to get professional help sooner than later.”

Motor Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence

The DSM-5 motor disorders include developmental coordination disorder; stereotypic movement disorder; and the tic disorders of Tourette’s Disorder, persistent (chronic) motor or vocal tic disorder, and provisional tic disorder.

Motor disorders are malfunctions of the nervous system that cause involuntary or uncontrollable movements or actions of the body. These disorders can cause lack of intended movement or an excess of involuntary movement. Symptoms of motor disorders include tremors, jerks, twitches, spasms, contractions, or gait problems.

Causes of Motor Disorders

Pathological changes of certain areas of the brain are the main causes of most motor disorders. Causes of motor disorders by genetic mutation usually affect the cerebellum. The way humans move requires many parts of the brain to work together to perform a complex process. The brain must send signals to the muscles instructing them to perform a certain action. There are constant signals being sent to and from the brain and the muscles that regulate the details of the movement such as speed and direction, so when a certain part of the brain malfunctions, the signals can be incorrect or uncontrollable causing involuntary or uncontrollable actions or movements.

Developmental Coordination Disorder

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD), also known as developmental motor coordination disorder, developmental dyspraxia, or simply dyspraxia, is a chronic neurological disorder beginning in childhood. It is also known to affect planning of movements and coordination as a result of brain messages not being accurately transmitted to the body. Impairments in skilled motor movements per a child’s chronological age interfere with activities of daily living. A diagnosis of developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is then reached only in the absence of other neurological impairments like cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease.

The DSM-5 criteria are as follows:

- Motor coordination will be greatly reduced, although the intelligence of the child is normal for the age.

- The difficulties the child experiences with motor coordination or planning interfere with the child’s daily life.

- The difficulties with coordination are not due to any other medical condition

- If the child also experiences comorbidities such as intellectual or other developmental disorder; motor coordination is still disproportionally affected.

Management

There is no cure for the condition. Instead, it is managed through therapy. Physical therapy or occupational therapy can help those living with the condition.

Some people with the condition find it helpful to find alternative ways of carrying out tasks or organizing themselves, such as typing on a laptop instead of writing by hand or using diaries and calendars to keep organized. A review completed in 2017 by Cochrane of task-oriented interventions for developmental coordination disorder (DCD) resulted in inconsistent findings and a call for further research and randomized controlled trials.

Epidemiology

DCD is a lifelong neurological condition that is more common in males than in females, with a ratio of approximately four males to every female. The exact proportion of people with the disorder is unknown since the disorder can be difficult to detect due to a lack of specific laboratory tests, thus making diagnosis of the condition one of elimination of all other possible causes/diseases. Approximately five to 6% of children are affected by this condition.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions to get a better understanding of DCD and measures taken to learn more about the disorder:

Stereotypic Movement Disorder

Stereotyped movements are common in infants and young children; if the child is not distressed by movements and daily activities are not impaired, diagnosis is not warranted. When stereotyped behaviors cause significant impairment in functioning, an evaluation for stereotypic movement disorder is needed. There are no specific tests for diagnosing this disorder, although some tests may be ordered to rule out other conditions. Stereotyped movement disorder (SMD) may occur with Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, intellectual development disorder (intellectual disability), and fetal alcohol exposure or as a result of amphetamine intoxication.

When diagnosing stereotypic movement disorder, DSM-5 calls for specification of

with or without self-injurious behavior,

association with another known medical condition or environmental factor, and

severity (mild, moderate, or severe).

Common repetitive movements of stereotyped movement disorder (SMD) include head banging, arm-waving, hand-shaking, rocking and rhythmic movements, self-biting, self-hitting, and skin-picking; other stereotypies are thumb-sucking, nail-biting, trichotillomania, bruxism, and abnormal running or skipping.

Epidemiology

Stereotyped movement disorder (SMD) occurs in about 3%-4% of children. Stereotypies often represent a physiological and transient finding, up to 60% of neurologically typical children showing some stereotypic movements or behaviors between two and five years. Therefore, SMD are classified as primary, indicating their presence in an otherwise typically developing child, or secondary, if another of the above-mentioned neuropsychiatric disorders is present. Although not necessary for the diagnosis, individuals with intellectual development disorder (intellectual disorder) are at higher risk for SMD. It is more common in boys and can occur at any age.

Management

Though we have yet to find a cure for these disorders, some studies have looked at the effectiveness of medication therapy but thus far (based on parent reports of medication trials) there haven’t been any medication therapy identified to be effective in treating symptoms. However, behavioral therapy appears to be beneficial for those with primary SMD. Researchers found that therapy that focuses on a mix of awareness and reinforcement of other behaviors helped reduce unwanted movement. Additionally, another study looked at the effectiveness of home-based, parent-administered behavioral therapy and this assessment showed significant improvement compared to the baseline.

Tic Disorders

Tourette Syndrome (TS or Tourette’s)

To be diagnosed with Tourette syndrome (TS or Tourette’s), a person must have

two or more motor tics (for example, blinking or shrugging the shoulders) and at least one vocal tic (for example, humming, clearing the throat, or yelling out a word or phrase), although they might not always happen at the same time.

had tics for at least a year. The tics can occur many times a day (usually in bouts) nearly every day or off and on.

tics that begin before age 18 years.

symptoms that are not due to taking medicine or other drugs or due to having another medical condition (for example, seizures, Huntington disease, or postviral encephalitis).

Coughing is a common tic.

Tourette syndrome or Tourette’s syndrome (TS or Tourette’s) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence. It is characterized by multiple movement (motor) tics and at least one vocal (phonic) tic. Common tics are blinking, coughing, throat clearing, sniffing, and facial movements. These are typically preceded by an unwanted urge or sensation in the affected muscles, can sometimes be suppressed temporarily, and characteristically change in location, strength, and frequency. Tourette’s is at the more severe end of a spectrum of tic disorders. The tics often go unnoticed by casual observers.

Tourette’s was once regarded as a rare and bizarre syndrome and has popularly been associated with coprolalia (the utterance of obscene words or socially inappropriate and derogatory remarks). It is no longer considered rare; about 1% of school-age children and adolescents are estimated to have Tourette’s, and coprolalia occurs only in a minority. There are no specific tests for diagnosing Tourette’s; it is not always correctly identified because most cases are mild and the severity of tics decreases for most children as they pass through adolescence. Therefore, many go undiagnosed or may never seek medical attention. Extreme Tourette’s in adulthood, though sensationalized in the media, is rare, but for a small minority, severely debilitating tics can persist into adulthood. Tourette’s does not affect intelligence or life expectancy. While the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors. The mechanism appears to involve dysfunction in neural circuits between the basal ganglia and related structures in the brain.

Persistent (Chronic) Motor or Vocal Tic Disorder

To be diagnosed with a persistent tic disorder, a person must

have one or more motor tics (for example, blinking or shrugging the shoulders) or vocal tics (for example, humming, clearing the throat, or yelling out a word or phrase), but not both.

have tics that occur many times a day nearly every day or on and off throughout a period of more than a year.

have tics that start before age 18 years.

have symptoms that are not due to taking medicine or other drugs or due to having a medical condition that can cause tics (for example, seizures, Huntington disease, or postviral encephalitis).

not have been diagnosed with Tourette’s.

Provisional Tic Disorder

To be diagnosed with a provisional tic disorder, a person must

have one or more motor tics (for example, blinking or shrugging the shoulders) or vocal tics (for example, humming, clearing the throat, or yelling out a word or phrase).

have been present for no longer than 12 months in a row.

have tics that start before age 18 years.

have symptoms that are not due to taking medicine or other drugs or due to having a medical condition that can cause tics (for example, Huntington disease or postviral encephalitis).

not have been diagnosed with Tourette’s or persistent motor or vocal tic disorder.

Epidemiology

Tic disorders are more common among males than females. At least one in five children experience some form of tic disorder, most frequently between the ages of seven and twelve. As many as one in 100 people may experience some form of tic disorder, usually before the onset of puberty.

Treatment of Tic Disorders

There is no cure for Tourette’s and no single most effective medication. In most cases, medication for tics is not necessary, and behavioral therapies are the first-line treatment. Education is an important part of any treatment plan, and explanation alone often provides sufficient reassurance that no other treatment is necessary. Among those who are referred to specialty clinics, other conditions like ADHD and OCD are more likely than in the broader population of persons with Tourette’s. These co-occurring diagnoses often cause more impairment to the individual than the tics; hence it is important to correctly distinguish co-occurring conditions and treat them.

WATCH THIS video below or online to learn more about Tourette’s and tic disorders:

Specific Learning Disorder

Specific learning disorder is a classification of disorders in which a person has difficulty learning in a typical manner within one of several domains. Often referred to as learning disabilities, learning disorders are characterized by inadequate development of specific academic, language, and speech skills. Types of learning disorders include difficulties in reading (dyslexia), mathematics (dyscalculia), and writing (dysgraphia).

The diagnosis of specific learning disorder was added to the DSM-5 in 2013. The DSM does not require that a single domain of difficulty (such as reading, mathematics, or written expression) be identified—instead, it is a single diagnosis that describes a collection of potential difficulties with general academic skills, simply including detailed specifiers for the areas of reading, mathematics, and writing. Academic performance must be below average in at least one of these fields, and the symptoms may also interfere with daily life or work. In addition, the learning difficulties cannot be attributed to other sensory, motor, developmental, or neurological disorders.

Learning disabilities are cognitive disorders that affect different areas of cognition, particularly language or reading. It should be pointed out that learning disabilities are not the same thing as intellectual disabilities. Learning disabilities are considered specific neurological impairments rather than global intellectual or developmental disabilities. Often, learning disabilities are not recognized until a child reaches school age. One confounding aspect of learning disabilities is that they most often affect children with average to above-average intelligence. In other words, the disability is specific to a particular area and not a measure of overall intellectual ability. At the same time, learning disabilities tend to exhibit comorbidity with other disorders, like attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

READ THIS post published in Psychology Today “Gifted Kids with Learning Problems” to learn more about “twice exceptional” or “2E” children.

Dyslexia

Dyslexia, sometimes called reading disorder, is the most common learning disability; of all students with specific learning disabilities, 70–80% have deficits in reading. The term developmental dyslexia is often used as a catch-all term, but researchers assert that dyslexia is just one of several types of reading disabilities. A reading disability can affect any part of the reading process, including word recognition, word decoding, reading speed, prosody (oral reading with expression), and reading comprehension.

Dyscalculia

Dyscalculia is a form of math-related disability that involves difficulties with learning math-related concepts (such as quantity, place value, and time), memorizing math-related facts, organizing numbers, and understanding how problems are organized on the page. People with this dyscalculia are often referred to as having poor “number sense.”

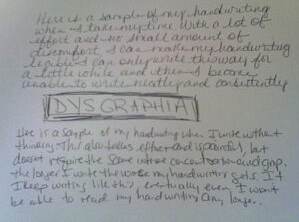

Dysgraphia

The term dysgraphia is often used as an overarching term for all disorders of written expression. Individuals with dysgraphia typically show multiple writing-related deficiencies, such as grammatical and punctuation errors within sentences, poor paragraph organization, multiple spelling errors, and excessively poor penmanship.

An additional type of learning disability is nonverbal, also known as NVLD. Nonverbal learning disabilities represent another type of learning difficulty in which individuals demonstrate adequate vocabulary, verbal expression, or reading skills, but present difficulties with certain nonverbal activities (e.g., problem-solving, visual-spatial tasks, reading body language, and recognizing social cues).

WATCH THIS short video below or online with captions on nonverbal learning disorder (from a 12-year-old’s perspective):

Etiology

The causes of learning disabilities are not well understood. However, some potential causes or contributing factors are

heredity. Learning disabilities often run in the family—children with learning disabilities are likely to have parents or other relatives with similar difficulties.

problems during pregnancy and birth. Learning disabilities can result from anomalies in the developing brain, illness or injury, fetal exposure to alcohol or drugs, low birth weight, oxygen deprivation, or premature or prolonged labor.

accidents after birth. Learning disabilities can also be caused by head injuries, malnutrition, or toxic exposure (such as heavy metals or pesticides).

Epidemiology

The DSM-5 estimates the prevalence of all learning disorders (including impairment in writing as well as in reading and/or mathematics) to be about five to 15% worldwide and the German S3 guideline names prevalence for reading and/or writing disorders of about 3%-8%.

The percentage of people with dyslexia is unknown, but it has been estimated to be as low as 5% and as high as 17% of the population. While it is diagnosed more often in males, some believe that it affects males and females equally.

Dyscalculia is thought to be present in 3%-6% of the general population, but estimates by country and sample vary. Many studies have found prevalence rates by gender to be equivalent. Those that find a gender difference in prevalence rates often find dyscalculia higher in females, but some few studies have found prevalence rates higher in males.

The prevalence for developmental writing disorders is about seven to 15% among school-aged children, with boys being more affected than girls by two to three times.

Treatment

Individuals with learning disorders face unique challenges that may persist throughout their lives. Depending on the type and severity of their disability, interventions and technology may be used to help the individual learn strategies that will foster future success. Some interventions can be quite simple while others are intricate and complex. Teachers, parents, and schools can work together to create a tailored plan for intervention and accommodation to aid an individual in successfully becoming an independent learner. School psychologists and other qualified professionals often help design and manage such interventions. Social support may also improve learning for students with learning disabilities.

PANDAS

PANDAS affects 1 in 200 children US-wide.

PANDAS (short for pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections). This diagnosis occurs when strep triggers a misdirected immune response and results in inflammation on a child’s brain. Usually, children with PANDAS have a very sudden onset or worsening of their symptoms, followed by slow, gradual improvement. If children with PANDAS get another strep infection, their symptoms suddenly worsen again. The increased symptom severity usually persists for at least several weeks but may last for several months or longer.

Though the actual prevalence of PANDAS is not known, a conservative estimate from the PANDAS Research Network suggests that 1 in 200 children are affected by this condition in the United States alone. Though symptoms often fade over time, low-level anxiety and OCD/TIC issues may remain permanently, and there are times where the exacerbation can take four to six months to remit. Treatment for this diagnosis includes antibiotics, IVIG (an intravenous pooled blood product comprising immunoglobulins that is used in treating immune deficiencies), plasmapheresis or plasma exchange (PEX) (a process during which the harmful auto-antibodies are removed from the blood system), and others such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), tonsillectomy, and probiotics. Generally, the best treatment for acute symptoms is antibiotics, and CBT to help manage neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Older Adulthood

It is estimated that 20% of people age 55 years or older experience some type of mental health concern. The most common conditions include anxiety, severe cognitive impairment, and mood disorders (such as depression or bipolar disorder). Mental health issues are often implicated as a factor in cases of suicide. Older men have the highest suicide rate of any age group. Men aged 85 years or older have a suicide rate of 45.23 per 100,000, compared to an overall rate of 11.01 per 100,000 for all ages.

Depression is Not a Normal Part of Growing Older

Depression is a true and treatable medical condition, not a normal part of aging. However older adults are at an increased risk for experiencing depression. If you are concerned about a loved one, offer to go with him or her to see a health care provider to be diagnosed and treated.

Depression is not just having “the blues” or the emotions we feel when grieving the loss of a loved one. It is a true medical condition that is treatable, like diabetes or hypertension.

How is Depression Different for Older Adults?

Older adults are at increased risk. We know that about 80% of older adults have at least one chronic health condition, and 50% have two or more. Depression is more common in people who also have other illnesses (such as heart disease or cancer) or whose function becomes limited.

Older adults are often misdiagnosed and undertreated. Healthcare providers may mistake an older adult’s symptoms of depression as just a natural reaction to illness or the life changes that may occur as we age, and therefore not see the depression as something to be treated. Older adults themselves often share this belief and do not seek help because they don’t understand that they could feel better with appropriate treatment.

How Many Older Adults Are Depressed?

The good news is that the majority of older adults are not depressed. Some estimates of major depression in older people living in the community range from less than 1% to about 5% but rise to 13.5% in those who require home healthcare and to 11.5% in older hospital patients.

READ THIS report The Mental Health Landscape of Older Adults Mental Health in the US by the Brookings Institute for more information and statistics. You can also download the full white paper.

Social Support

Social support serves major support functions, including emotional support (e.g., sharing problems or venting emotions), informational support (e.g., advice and guidance), and instrumental support (e.g., providing rides or assisting with housekeeping).

Adequate social and emotional support is associated with reduced risk of mental illness, physical illness, and mortality

The majority (nearly 90%) of adults age 50 or older indicated that they are receiving adequate amounts of support.

Adults age 65 or older were more likely than adults age 50–64 to report that they “rarely” or “never” received the social and emotional support they needed (12.2% compared to 8.1%, respectively).

Approximately one-fifth of Hispanic and other, non-Hispanic adults age 65 years or older reported that they were not receiving the support they need, compared to about one-tenth of older white adults.

Among adults age 50 or older, men were more likely than women to report they “rarely” or “never” received the support they needed (11.39% compared to 8.49%).

Psychological Disorders

In this next part of the module, we will clarify what psychological disorders are, how they are diagnosed and classified, their symptoms, and insights into their causes.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Extremely stressful or traumatic events, such as combat, natural disasters, and terrorist attacks, place the people who experience them at an increased risk for developing psychological disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Throughout much of the 20th century, this disorder was called shell shock and combat neurosis because its symptoms were observed in soldiers who had engaged in wartime combat. By the late 1970s it had become clear that women who had experienced sexual traumas (e.g., rape, domestic battery, and incest) often experienced the same set of symptoms as did soldiers. The term posttraumatic stress disorder was developed given that these symptoms could happen to anyone who experienced psychological trauma.

A Broader Definition of PTSD

PTSD was listed among the anxiety disorders in previous DSM editions. In DSM-5, it is now listed among a group called Trauma-and-Stressor-Related Disorders. For a person to be diagnosed with PTSD, she be must exposed to, witness, or experience the details of a traumatic experience (e.g., a first responder), one that involves “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” (APA, 2013, p. 271). These experiences can include such events as combat, threatened or actual physical attack, sexual assault, natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and automobile accidents. This criterion makes PTSD the only disorder listed in the DSM in which a cause (extreme trauma) is explicitly specified.

Symptoms of PTSD include intrusive and distressing memories of the event, flashbacks (states that can last from a few seconds to several days, during which the individual relives the event and behaves as if the event were occurring at that moment [APA, 2013]), avoidance of stimuli connected to the event, persistently negative emotional states (e.g., fear, anger, guilt, and shame), feelings of detachment from others, irritability, proneness toward outbursts, and an exaggerated startle response (jumpiness). For PTSD to be diagnosed, these symptoms must occur for at least one month.

Roughly 7% of adults in the United States, including 9.7% of women and 3.6% of men, experience PTSD in their lifetime (National Comorbidity Survey, 2007), with higher rates among people exposed to mass trauma and people whose jobs involve duty-related trauma exposure (e.g., police officers, firefighters, and emergency medical personnel) (APA, 2013). Nearly 21% of residents of areas affected by Hurricane Katrina suffered from PTSD one year following the hurricane (Kessler et al., 2008), and 12.6% of Manhattan residents were observed as having PTSD 2–3 years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks (DiGrande et al., 2008).

Risk Factors for PTSD

Of course, not everyone who experiences a traumatic event will go on to develop PTSD; several factors strongly predict the development of PTSD: trauma experience, greater trauma severity, lack of immediate social support, and more subsequent life stress (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000). Traumatic events that involve harm by others (e.g., combat, rape, and sexual molestation) carry greater risk than do other traumas (e.g., natural disasters) (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995). Factors that increase the risk of PTSD include female gender, low socioeconomic status, low intelligence, personal history of mental disorders, history of childhood adversity (abuse or other trauma during childhood), and family history of mental disorders (Brewin et al., 2000). Personality characteristics such as neuroticism and somatization (the tendency to experience physical symptoms when one encounters stress) have been shown to elevate the risk of PTSD (Bramsen, Dirkzwager, & van der Ploeg, 2000). People who experience childhood adversity and/or traumatic experiences during adulthood are at significantly higher risk of developing PTSD if they possess one or two short versions of a gene that regulates the neurotransmitter serotonin (Xie et al., 2009). This suggests a possible diathesis-stress interpretation of PTSD: its development is influenced by the interaction of psychosocial and biological factors.

Factors that increase the risk of PTSD include female gender, low socioeconomic status, low intelligence, personal history of mental disorders, history of childhood adversity (abuse or other trauma during childhood), and family history of mental disorders. Personality characteristics such as neuroticism and somatization (the tendency to experience physical symptoms when one encounters stress) have been shown to elevate the risk of PTSD. People who experience childhood adversity and/or traumatic experiences during adulthood are at significantly higher risk of developing PTSD if they possess one or two short versions of a gene that regulates the neurotransmitter serotonin. This suggests a possible diathesis-stress interpretation of PTSD: its development is influenced by the interaction of psychosocial and biological factors.

Support for Sufferers of PTSD

Research has shown that social support following a traumatic event can reduce the likelihood of PTSD. Social support is often defined as the comfort, advice, and assistance received from relatives, friends, and neighbors. Social support can help individuals cope during difficult times by allowing them to discuss feelings and experiences and providing a sense of being loved and appreciated. A 14-year study of 1,377 American Legionnaires who had served in the Vietnam War found that those who perceived less social support when they came home were more likely to develop PTSD than were those who perceived greater support. In addition, those who became involved in the community were less likely to develop PTSD, and they were more likely to experience a remission of PTSD than were those who were less involved.

Learning and Development of PTSD

PTSD learning models suggest that some symptoms are developed and maintained through classical conditioning. The traumatic event may act as an unconditioned stimulus that elicits an unconditioned response characterized by extreme fear and anxiety. Cognitive, emotional, physiological, and environmental cues accompanying or related to the event are conditioned stimuli. These traumatic reminders evoke conditioned responses (extreme fear and anxiety) similar to those caused by the event itself (Nader, 2001). A person who was in the vicinity of the Twin Towers during the 9/11 terrorist attacks and who developed PTSD may display excessive hypervigilance and distress when planes fly overhead; this behavior constitutes a conditioned response to the traumatic reminder (conditioned stimulus of the sight and sound of an airplane). Differences in how conditionable individuals are help to explain differences in the development and maintenance of PTSD symptoms (Pittman, 1988). Conditioning studies demonstrate facilitated acquisition of conditioned responses and delayed extinction of conditioned responses in people with PTSD (Orr et al., 2000).

Cognitive factors are important in the development and maintenance of PTSD. One model suggests that two key processes are crucial: disturbances in memory for the event, and negative appraisals of the trauma and its aftermath (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). According to this theory, some people who experience traumas do not form coherent memories of the trauma; memories of the traumatic event are poorly encoded and, thus, are fragmented, disorganized, and lacking in detail. Therefore, these individuals are unable remember the event in a way that gives it meaning and context. A rape victim who cannot coherently remember the event may remember only bits and pieces (e.g., the attacker repeatedly telling her she is stupid); because she was unable to develop a fully integrated memory, the fragmentary memory tends to stand out. Although unable to retrieve a complete memory of the event, she may be haunted by intrusive fragments involuntarily triggered by stimuli associated with the event (e.g., memories of the attacker’s comments when encountering a person who resembles the attacker). This interpretation fits previously discussed material concerning PTSD and conditioning. The model also proposes that negative appraisals of the event (“I deserved to be raped because I’m stupid”) may lead to dysfunctional behavioral strategies (e.g., avoiding social activities where men are likely to be present) that maintain PTSD symptoms by preventing both a change in the nature of the memory and a change in the problematic appraisals.

WATCH THIS video below or online on how addiction can play into trauma and the different types of treatments used:

Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are mental health illnesses that involve emotional and behavioral disturbance surrounding weight and food issues. The most common are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Eating disorders can have life-threatening consequences.

Anorexia nervosa is characterized by self-starvation and extreme weight loss either through restriction or through binge-purging. This may frequently be a result of body dysmorphic disorder (a condition in which someone feels that their body looks differently than it actually does) or a result of other psychiatric complications such as OCD or depression. Starvation can cause harm to vital organs such as the heart and brain, can cause nails, hair, and bones to become brittle, and can make the skin dry and sometimes yellow or covered with soft hair. Menstrual periods can become irregular or stop completely.

People with bulimia nervosa eat large amounts of food (also called bingeing) at least two times a week and then vomit (also called purging) or exercise compulsively. Because many people who “binge and purge” maintain their body weight, they may keep their problem a secret for years. Vomiting can cause loss of important minerals, life-threatening heart arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat), damage to the teeth, and swelling of the throat. Bulimia can also cause irregular menstrual periods.

People who binge without purging also have a disorder called binge eating disorder. This is frequently associated with feelings of loss of control and shame surrounding eating. People who are diagnosed with this disorder tend to gain weight, and many will have all of the consequences of being overweight, including high blood pressure and other cardiac symptoms, diabetes, and musculoskeletal complaints.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

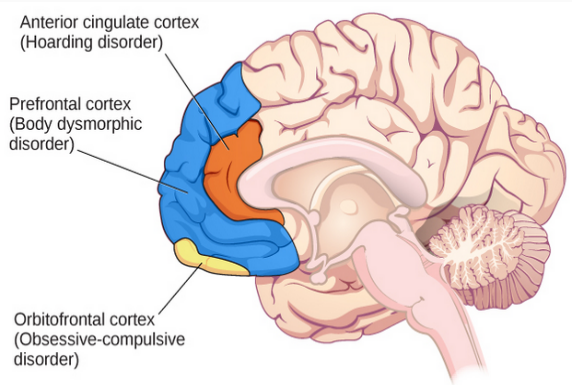

Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders are a group of overlapping disorders that generally involve intrusive, unpleasant thoughts, and repetitive behaviors. Many of us experience unwanted thoughts from time to time (e.g., craving double cheeseburgers when dieting), and many of us engage in repetitive behaviors on occasion (e.g., pacing when nervous). However, obsessive-compulsive disorders elevate unwanted thoughts and repetitive behaviors to a status so intense that these cognitions and activities disrupt daily life. Included in this category are obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), body dysmorphic disorder, hoarding disorder, trichotillomania, and excoriation disorder.

People with OCD experience thoughts and urges that are intrusive and unwanted (obsessions) and/or the need to engage in repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions). A person with this disorder might, for example, spend hours each day washing their hands or constantly checking and rechecking to make sure that a stove, faucet, or light has been turned off.

Obsessions are more than just unwanted thoughts that seem to randomly jump into our head from time to time, such as recalling an insensitive remark a coworker made recently, and they are more significant than day-to-day worries we might have, such as justifiable concerns about being laid off from a job. Rather, obsessions are characterized as persistent, unintentional, and unwanted thoughts and urges that are highly intrusive, unpleasant, and distressing (APA, 2013). Common obsessions include concerns about germs and contamination, doubts (“Did I turn the water off?”), order and symmetry (“I need all the spoons in the tray to be arranged a certain way”), and urges that are aggressive or lustful. Usually, the person knows that such thoughts and urges are irrational and thus tries to suppress or ignore them, but has an extremely difficult time doing so. These obsessive symptoms sometimes overlap, such that someone might have both contamination and aggressive obsessions (Abramowitz & Siqueland, 2013).

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions of a young mother’s struggle with OCD:

Compulsions are repetitive and ritualistic acts that are typically carried out primarily as a means to minimize the distress that obsessions trigger or to reduce the likelihood of a feared event (APA, 2013). Compulsions often include such behaviors as repeated and extensive hand washing, cleaning, checking (e.g., that a door is locked), and ordering (e.g., lining up all the pencils in a particular way), and they also include such mental acts as counting, praying, or reciting something to oneself. Compulsions characteristic of OCD are not performed out of pleasure, nor are they connected in a realistic way to the source of the distress or feared event. Approximately 2.3% of the U.S. population will experience OCD in their lifetime (Ruscio, Stein, Chiu, & Kessler, 2010) and, if left untreated, OCD tends to be a chronic condition creating lifelong interpersonal and psychological problems (Norberg, Calamari, Cohen, & Riemann, 2008).

WATCH THIS video below or online to understand why people who are simply orderly or meticulous are probably not suffering from OCD:

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

An individual with body dysmorphic disorder is preoccupied with a perceived flaw in her physical appearance that is either nonexistent or barely noticeable to other people (APA, 2013). These perceived physical defects cause the person to think she is unattractive, ugly, hideous, or deformed. These preoccupations can focus on any bodily area, but they typically involve the skin, face, or hair. The preoccupation with imagined physical flaws drives the person to engage in repetitive and ritualistic behavioral and mental acts, such as constantly looking in the mirror, trying to hide the offending body part, comparisons with others, and, in some extreme cases, cosmetic surgery (Phillips, 2005). An estimated 2.4% of the adults in the United States meet the criteria for body dysmorphic disorder, with slightly higher rates in women than in men (APA, 2013).

Hoarding Disorder

Although hoarding was traditionally considered to be a symptom of OCD, considerable evidence suggests that hoarding represents an entirely different disorder (Mataix-Cols et al., 2010). People with hoarding disorder cannot bear to part with personal possessions, regardless of how valueless or useless these possessions are. As a result, these individuals accumulate excessive amounts of usually worthless items that clutter their living areas ([link]). Often, the quantity of cluttered items is so excessive that the person is unable use his kitchen, or sleep in his bed. People who suffer from this disorder have great difficulty parting with items because they believe the items might be of some later use, or because they form a sentimental attachment to the items (APA, 2013). Importantly, a diagnosis of hoarding disorder is made only if the hoarding is not caused by another medical condition and if the hoarding is not a symptom of another disorder (e.g., schizophrenia) (APA, 2013).

Causes of OCD

The results of family and twin studies suggest that OCD has a moderate genetic component. The disorder is five times more frequent in the first-degree relatives of people with OCD than in people without the disorder (Nestadt et al., 2000). Additionally, the concordance rate of OCD among identical twins is around 57%; however, the concordance rate for fraternal twins is 22% (Bolton, Rijsdijk, O’Connor, Perrin, & Eley, 2007). Studies have implicated about two dozen potential genes that may be involved in OCD; these genes regulate the function of three neurotransmitters: serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate (Pauls, 2010). Many of these studies included small sample sizes and have yet to be replicated. Thus, additional research needs to be done in this area.

A brain region that is believed to play a critical role in OCD is the orbitofrontal cortex (Kopell & Greenberg, 2008), an area of the frontal lobe involved in learning and decision-making (Rushworth, Noonan, Boorman, Walton, & Behrens, 2011). In people with OCD, the orbitofrontal cortex becomes especially hyperactive when they are provoked with tasks in which, for example, they are asked to look at a photo of a toilet or of pictures hanging crookedly on a wall.

As with the orbitofrontal cortex, other regions of the OCD circuit show heightened activity during symptom provocation (Rotge et al., 2008), which suggests that abnormalities in these regions may produce the symptoms of OCD (Saxena, Bota, & Brody, 2001). Consistent with this explanation, people with OCD show a substantially higher degree of connectivity of the orbitofrontal cortex and other regions of the OCD circuit than do those without OCD (Beucke et al., 2013).

The findings discussed above were based on imaging studies, and they highlight the potential importance of brain dysfunction in OCD. However, one important limitation of these findings is the inability to explain differences in obsessions and compulsions. Another limitation is that the correlational relationship between neurological abnormalities and OCD symptoms cannot imply causation (Abramowitz & Siqueland, 2013).

Mood Disorders

Mood disorders are characterized by severe disturbances in mood and emotions—most often depression, but also mania and elation. All of us experience fluctuations in our moods and emotional states, and often these fluctuations are caused by events in our lives. We become elated if our favorite team wins the World Series and dejected if a romantic relationship ends or if we lose our job. At times, we feel fantastic or miserable for no clear reason. People with mood disorders also experience mood fluctuations, but their fluctuations are extreme, distort their outlook on life, and impair their ability to function.