12 Module 12: Death and Dying

Module 12 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Compare Attitudes Toward Death

Discuss how cultural, social, and individual attitudes toward death shape end-of-life experiences. - Understand Definitions of Death

Differentiate between physiological, social, and psychological death and their implications. - Explore Models of Grief

Compare theories of grief, including Kübler-Ross’s stages of loss and the dual-process model. - Discuss Bereavement and Mourning

Identify the psychological and cultural aspects of bereavement, mourning rituals, and their impacts on grieving processes. - Analyze End-of-Life Care

Explain the philosophy and practices of palliative care and hospice, including cultural attitudes toward these services. - Examine Ethical Issues

Compare euthanasia, passive euthanasia, and physician-assisted suicide, and evaluate ethical debates surrounding them. - Understand the Role of Nurses

Describe the role of nurses in providing culturally competent care for terminally ill patients and their families. - Identify Characteristics of a Good Death

Discuss components of a “good death,” such as dignity, comfort, and respect for personal and cultural preferences. - Address Death Anxiety

Summarize factors contributing to death anxiety in patients, families, and healthcare providers, and strategies for managing it. - Examine Grief Across Lifespans

Explain how grief differs by age and developmental stage, from childhood to late adulthood. - Reflect on Personal Perspectives

Express individual views on death and dying and consider how these influence attitudes toward end-of-life care. - Discuss Social and Cultural Traditions

Describe diverse funeral practices and traditions associated with death and mourning across cultures and religions.

Why Study Death and Dying?

In the Lancet’s Commission on the Value of Death: Bringing death back into life, the authors write:

The story of dying in the 21st century is a story of paradox. While many people are overtreated in hospitals with families and communities relegated to the margins, still more remain undertreated, dying of preventable conditions and without access to basic pain relief. […] How people die has changed radically over recent generations. Death comes later in life for many and dying is often prolonged. Death and dying have moved from a family and community setting to primarily the domain of health systems. Futile or potentially inappropriate treatment can continue into the last hours of life. The roles of families and communities have receded as death and dying have become unfamiliar and skills, traditions, and knowledge are lost. Death and dying have become unbalanced in high-income countries, and increasingly in low-and-middle-income countries; there is an excessive focus on clinical interventions at the end of life, to the detriment of broader inputs and contributions. […] Philosophers and theologians from around the globe have recognised the value that death holds for human life. Death and life are bound together: without death there would be no life. Death allows new ideas and new ways. Death also reminds us of our fragility and sameness: we all die. Caring for the dying is a gift, as some philosophers and many carers, both lay and professional, have recognised. Much of the value of death is no longer recognised in the modern world, but rediscovering this value can help care at the end of life and enhance living. (Salnow et. al., 2022)

In this chapter, we look at death and dying, grief and bereavement. We explore palliative care and hospice. And we explore funeral rites and the right to die.

READ THIS See the Lancet’s full Commission on the Value of Death for more information on how we can all contribute to a better way for death and dying. The authors work to extensively describe a “new vision of how death and dying could be” using five principles. The five principles are: “the social determinants of death, dying, and grieving are tackled; dying is understood to be a relational and spiritual process rather than simply a physiological event; networks of care lead support for people dying, caring, and grieving; conversations and stories about everyday death, dying, and grief become common; and death is recognised as having value.”

Attitudes about Death

When asked what type of funeral they would like to have, students responded in a variety of ways; each expressing both their personal beliefs and values and those of their culture.

I would like the service to be at a Baptist church, preferably my Uncle Ike’s small church. The service should be a celebration of life . . .I would like there to be hymns sung by my family members, including my favorite one, “It is Well With my Soul”. . .At the end, I would like the message of salvation to be given to the attendees and an alter call for anyone who would like to give their life to Christ. . .

I want a very inexpensive funeral-the bare minimum, only one vase of flowers, no viewing of the remains and no long period of mourning from my remaining family . . . funeral expenses are extremely overpriced and out of hand. . .

When I die, I would want my family members, friends, and other relatives to dress my body as it is usually done in my country, Ghana. Lay my dressed body in an open space in my house at the night prior to the funeral ceremony for my loved ones to walk around my body and mourn for me. . .

I would like to be buried right away after I die because I don’t want my family and friends to see my dead body and to be scared.

In my family we have always had the traditional ceremony-coffin, grave, tombstone, etc. But I have considered cremation and still ponder which method is more favorable. Unlike cremation, when you are ‘buried’ somewhere and family members have to make a special trip to visit, cremation is a little more personal because you can still be in the home with your loved ones . . .

I would like to have some of my favorite songs played . . .I will have a list made ahead of time. I want a peaceful and joyful ceremony and I want my family and close friends to gather to support one another. At the end of the celebration, I want everyone to go to the Thirsty Whale for a beer and Spang’s for pizza!

When I die, I want to be cremated . . . I want it the way we do it in our culture. I want to have a three day funeral and on the 4th day, it would be my burial/cremation day . . .I want everyone to wear white instead of black, which means they already let go of me. I also want to have a mass on my cremation day.

When I die, I would like to have a befitting burial ceremony as it is done in my Igbo customs. I chose this kind of funeral ceremony because that is what every average person wishes to have.

I want to be cremated when I die. To me, it’s not just my culture to do so but it’s more peaceful to put my remains or ashes to the world. Let it free and not stuck in a casket.

The Body After Death

In most cultures, after the last offices have been performed and before the onset of significant decay, relations or friends arrange for ritual disposition of the body, either by destruction, or by preservation, or in a secondary use. In the U.S., this frequently means either cremation or interment in a tomb.

There are various methods of destroying human remains, depending on religious or spiritual beliefs, and upon practical necessity. Cremation is a very old and quite common custom. For some people, the act of cremation exemplifies the belief of the Christian concept of “ashes to ashes”. On the other hand, in India, cremation and disposal of the bones in the sacred river Ganges is common. Another method is sky burial, which involves placing the body of the deceased on high ground (a mountain) and leaving it for birds of prey to dispose of, as in Tibet. In some religious views, birds of prey are carriers of the soul to the heavens. Such practice may also have originated from pragmatic environmental issues, such as conditions in which the terrain (as in Tibet) is too stony or hard to dig, or in which there are few trees around to burn. As the local religion of Buddhism, in the case of Tibet, believes that the body after death is only an empty shell, there are more practical ways than burial of disposing of a body, such as leaving it for animals to consume. In some fishing or marine communities, mourners may put the body into the water, in what is known as burial at sea. Several mountain villages have a tradition of hanging the coffin in woods.

Since ancient times, in some cultures efforts have been made to slow, or largely stop the body’s decay processes before burial, as in mummification or embalming. This process may be done before, during or after a funeral a ceremony. The Toraja people of Indonesia are known to mummify their deceased loved ones and keep them in their homes for weeks, months, and sometimes even years, before holding a funeral service.

READ THIS: Read more about the Toraja’s rituals in this Post Magazine article “Living with Corpses: How Indonesian’s Toraja People Deal with Their Dead.”

WATCH THIS TED talk, “The Corpses that Changed my Life” by Caitlin Doughty, a mortician and activist, who strives to encourage Americans to overcome their phobia of death and to be more open and involved in dealing with their deceased loved ones. Watch below or online.

These statements reflect a wide variety of conceptions and attitudes toward death. Culture plays a key role in the development of these conceptions and attitudes, and it also provides a framework within which they are expressed. For example, in a 2017 survey of people in the United States, Italy, Japan and Brazil, the percentage of people saying living as long as possible was extremely or very important ranged from about 17% in Japan to about 70% in Brazil, with Italian and United States respondents at about 45%. In that same survey, about 70% of Italian and Brazilian people said their family not being burdened financially was extremely or very important, while about 80% of Japanese people and 88% of United States people said so.

VIEW THIS: To see more results, see the survey’s chart of what people want at the end of life. However, it is important to note that culture does not provide set rules for how death is viewed and experienced, and there tends to be as much variation within cultures as well as between.

Another important consideration related to conceptions and attitudes toward death involves social attitudes. Death, in many cases, can be the “elephant in the room,” a concept that remains ever present but continues to be taboo for most individuals. Talking openly about death tends to be viewed negatively, or even as socially inappropriate. Specific social norms and standards regarding death vary between groups, but on a larger societal level, death is usually a topic reserved only for when it becomes absolutely necessary to bring up.

Cultural Considerations from Nursing Perspective

The role of the nurse in end-of-life care includes providing care that is individualized and culturally competent for each patient. Nurses who care for patients nearing the end of life should have a good understanding about the various beliefs and traditions held by various cultures about death and dying. This is something that is not always thought of in nursing school, but it is essential information to know when caring for patients who are dying. If the patient is from an ethnicity or religion that is different from the nurse, it is important to provide care that is respectful and appropriate within that particular faith or cultural tradition. Any nurse who will be caring for a patient whose particular culture differs from theirs is strongly encouraged to take the time to learn some basic information that will help to inform them about that culture and the practices they hold with regard to death and dying. The table below outlines traditions associated with several selected religions.

Diversity of Beliefs and Traditions Across Religions and Cultures

|

Religion |

Beliefs pertaining to death |

Preparation of the Body |

Funeral |

|

Catholic |

Beliefs include that the deceased travels from this world into eternal afterlife where the soul can reside in heaven, hell, or purgatory. Sacraments are given to the dying. |

Organ donation and autopsy are permitted. |

Cremation historically forbidden until 1963.The Vigil occurs the evening before the funeral mass is held. Mass includes Eucharist. If a priest is not available, a deacon can lead funeral services. Rite of committal takes place with interment. |

|

Protestant |

Belief in Jesus Christ and the Bible is central, although differences in interpretation exist in the various denominations. Beliefs include an afterlife. |

Organ donation and autopsy are permitted. |

Cremation or burial is accepted. Funeral can be held in funeral home or in church and led by minister or chaplain. |

|

Jewish |

Tradition cherishes life but death itself is not viewed as a tragedy. Views on an afterlife vary with the denomination (Reform, Conservative, or Orthodox). |

Autopsy and embalming are forbidden under ordinary circumstances. Open caskets are not permitted. |

Funeral held as soon as possible after death. Dark clothing is worn at and after the funeral/burial. It is forbidden to bury the decedent on the Sabbath or festivals. Three mourning periods are held after the burial, with Shiva being the first seven days after burial. |

|

Buddhist |

Both a religion and way of life with the goal of enlightenment. Beliefs include that life is a cycle of death and rebirth. |

Goal is a peaceful death. Statue of Buddha may be placed at bedside as the person is dying. Organ donation is not permitted. Incense is lit in the room following death. |

Family washes and prepares the body. Cremation is preferred but if buried, deceased should be dressed in regular daily clothes instead of fancy clothing. Monks may be present at the funeral and lead the chanting. |

|

Native American |

Beliefs vary among tribes. Sickness is thought to mean that one is out of balance with nature. Thought that ancestors can guide the deceased. Believe that death is a journey to another world. Family may or may not be present for death. |

Preparation of the body may be done by family. Organ donation generally not preferred. |

Most burials are natural or green. Various practices differ with tribe. Among the Navajo, hearing an owl or coyote is a sign of impending death and the casket is left slightly open so the spirit can escape. Navajo and Apache tribes believe that spirits of deceased can haunt the living. The Comanche tribe buries the dead in the place of death or in a cave. |

|

Hindu |

Beliefs include reincarnation, where a deceased person returns in the form of another, and Karma. |

Organ donation and autopsy are acceptable. Bathing the body daily is necessary. Death and dying must be peaceful. Customary for body to not be left alone until cremated. |

Prefer cremation within 24 hours after death. Ashes should be scattered in sacred rivers. |

|

Muslim |

Muslims believe in an afterlife and that the body must be quickly buried so that the soul may be freed. |

Embalming and cremation are not permitted. Autopsy is permitted for legal or medical reasons only. After death, the body should face Mecca or the East. Body is prepared by a person of the same gender. |

Burial takes place as soon as possible. Women and men will sit separately at the funeral. Flowers and excessive mourning are discouraged. Body is usually buried in a shroud and is buried with the head pointing toward Mecca. |

(ELNEC, 2010; Health Care Chaplaincy, 2009).

Developmental Perspectives on Death

Another key factor in individuals’ attitudes towards death and dying is where they are in their own lifespan development. First of all, individuals’ attitudes are linked to their cognitive ability to understand death and dying. Infants and toddlers cannot understand death. They function in the present and are aware of loss and separation, as well as disruptions in their routines. They are also attuned to the emotions and behaviors of significant adults in their lives, so a death of a loved one may cause a young child to become anxious and irritable, cry, or change their sleeping and eating habits.

A preschooler may approach death by asking when a deceased person is coming back and might search for them, thinking that death is temporary and reversible. They may experience brief but intense reactions, such as tantrums, or other behaviors like frightening dreams and disrupted sleep, bedwetting, clinging, and thumbsucking. Similarly, those in early childhood (age 4-7), might also ask where the deceased person is and search for them, as well as regress to younger behaviors. They might also think that the person’s death is their own fault, as per their belief in the power of their own thoughts and “magical thinking.” Their grief might be expressed through play, rather than verbally.

Those in middle childhood (ages 7-10) begin to see death as final, not reversible, and universal. Developing Piaget’s concrete operational thinking, they may engage in personification, seeing death as a human figure who carried their loved one away. They may not really believe that death could happen to them or their family, maybe only to the very old or sick—they may also view death as a punishment. They might act out in school or they might try to keep a bond with the deceased by taking on that person’s role or behaviors.

Preadolescents (ages 10-12) try to understand both biological and emotional processes of death. But they try to hide their feelings and not seem different from their peers; they may seem indifferent, or they may have outbursts. As Amsler (2015) noted, children’s and teens’ experiences with death and what adults tell them about death will also influence their comprehension. As teens develop formal operational thinking (ages 12-18), they can apply logic to abstractions; they spend more time pondering the meaning of life and death and what comes after death. Their understanding of death becomes more complex as they move from a binary logical concept (alive or dead) to a fuzzy logical concept with potential life after death, for instance. Adolescents are also tasked with integrating these beliefs into their own identity development.

What about attitudes toward death in adulthood? We’ve learned about adults becoming more concerned with their own mortality during middle adulthood, particularly as they experience the deaths of their own parents. Recently, (Sinoff, 2017) research on thanatophobia, or death anxiety, found differences in death anxiety between elderly patients and their adult children. Death anxiety may entail two different parts—being anxious about death and being anxious about the process of dying. The elderly were only anxious about the process of dying (i.e., suffering), but their adult children were very anxious about death itself and mistakenly believed that their parents were also anxious about death itself. This is an important distinction and can make a significant difference in how medical information and end-of-life decisions are communicated within families. Consistent with this, if elders resolve Erikson’s final psychosocial crisis, ego integrity versus despair, in a positive way, they may not fear death, but gain the virtue of wisdom. If they are not feeling desperate (“despair” with time running out), then they may not be anxious or fearful about death.

Defining Death

One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at what defines physical death and social death. According to the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) (Uniform Law Commissioners, 1980), death is defined clinically as the following:

An individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.

The UDDA was approved for the United States in 1980 by a committee of national commissioners, the American Medical Association, the American Bar Association, and the President’s Commission on Medical Ethics. This act has since been adopted by most states and provides a comprehensive and medically factual basis for determining death in all situations.

Some have challenged this definition though, noting it is difficult to capture the irreversible, final moment of death. They note Clause (1) does not accurately capture the timing of the final biological death event. That is to say, irreversible and irreparable damage to heart and lungs will quickly and inevitably lead to entire brain death, but it is not quite synonymous with that final event. There is a time interval in which the brain is dying because of lack of a supply of oxygen-rich blood to keep it alive, at which point the human brain is dying but not yet dead (Scarre 2007, p. 6).

Clause (2) points to the timing of the final event. The certitude around entire (whole) brain death follows from a clinical assessment of total brain failure. However, the assessment of total brain failure has courted controversy. The neurologist Alan Shewmon is a leading critic of equating total brain failure with human death. Shewmon identified many cases of patients who were diagnosed with total brain failure that nevertheless ended up surviving. Shewmon collected 175 case reports of patients that had survived against the odds, and whose bodies had stabilised long after the period accounted for by current literature on ‘brain death’. The length of patient survival varied from a month to a year and even, in the exceptional Florida Boy Case, 14 years (Rubenstein 2009, pp. 37–38). In certain cases, therefore, it may be possible to try to artificially sustain a body after so-called total brain failure has been diagnosed. As such, it is possible to distinguish total brain failure from chronic brain death. Shewmon’s arguments have thrown significant doubt over associating death with total brain failure.

Tomasini (2017) writes about the process of dying, which in its crudest form may be subdivided into roughly six categories, to define death:

- Reversible and natural. For example, death may be part of the natural cycle of regenerating the body;

- Irreversible and natural. Death, for example, is part of ageing;

- Reversible and catastrophic. Having a cardiac arrest is reversible, in that the patient can be resuscitated. At this point the patient may be described as clinically but not medically dead;

- Irreversible, catastrophic and unambiguously fatal. Total brain failure that is not redeemable in an ICU environment and is characterised as medical death;

- Irreversible, catastrophic and survivable if technologically aided. Serious brain injury may not necessarily be fatal—persons affected by serious brain injuries survive and sometimes make remarkable recoveries in ICU;

- Irreversible, catastrophic and survivable if technologically unaided. Survivors of major brain injuries that eventually make it out of ICU may be severely mentally and physically disabled requiring life-long support and care. Those who survive the initial crisis and are eventually discharged from ICU and hospital care may have personalities that are barely unrecognisable from before.

Aspects of Death

One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at physiological death, social death, and psychological death. These deaths do not occur simultaneously, nor do they always occur in a set order. Rather, a person’s physiological, social, and psychological deaths can occur at different times.

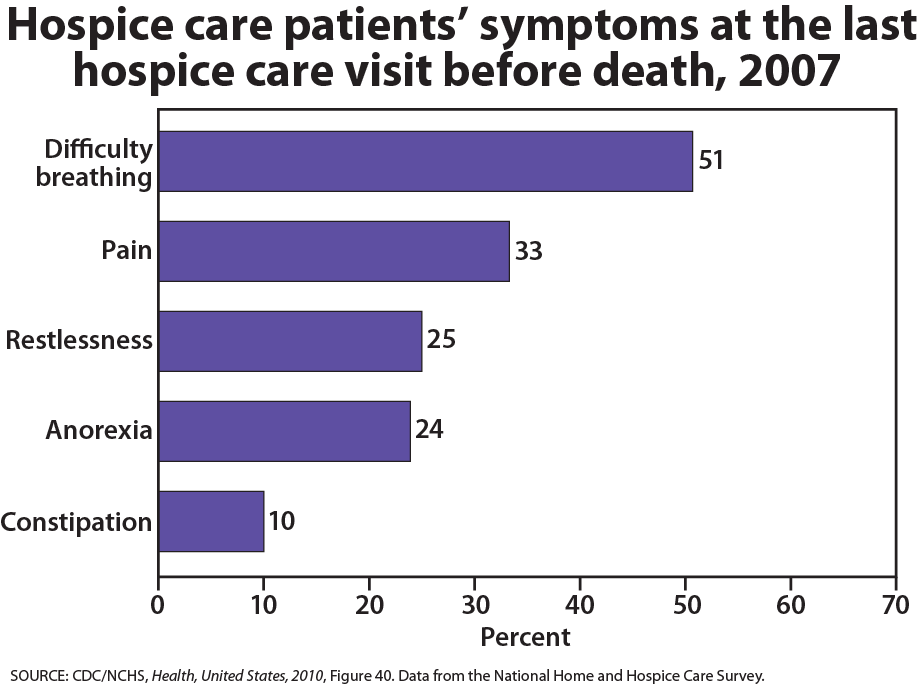

Physiological death occurs when the vital organs no longer function. The digestive and respiratory systems begin to shut down during the gradual process of dying. A dying person no longer wants to eat as digestion slows, the digestive track loses moisture, and chewing, swallowing, and elimination become painful processes. Circulation slows and mottling, or the pooling of blood, may be noticeable on the underside of the body, appearing much like bruising. Breathing becomes more sporadic and shallower and may make a rattling sound as air travels through mucus- filled passageways. Agonal breathing refers to gasping, labored breaths caused by an abnormal pattern of brainstem reflex. The person often sleeps more and more and may talk less, although they may continue to hear. The kinds of symptoms noted prior to death in patients under hospice care (care focused on helping patients die as comfortably as possible) are noted below.

When a person is brain dead, or no longer has brain activity, they are clinically dead. Physiological death may take 72 or fewer hours. This is different than a vegetative state, which occurs when the cerebral cortex no longer registers electrical activity but the brain stems continues to be active. Individuals who are kept alive through life support may be classified this way.

WATCH THIS video below or online explaining the difference between a vegetative state, a coma, and being brain dead. You can view the transcript for “Is A Brain Dead Person Actually Dead?” here.

Social death begins much earlier than physiological death. Social death occurs when others begin to withdraw from someone who is terminally ill or has been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Those diagnosed with conditions such as AIDS or cancer may find that friends, family members, and even health care professionals begin to say less and visit less frequently. Meaningful discussions may be replaced with comments about the weather or other topics of light conversation. Doctors may spend less time with patients after their prognosis becomes poor. Why do others begin to withdraw? Friends and family members may feel that they do not know what to say or that they can offer no solutions to relieve suffering. They withdraw to protect themselves against feeling inadequate or from having to face the reality of death. Health professionals, trained to heal, may also feel inadequate and uncomfortable facing decline and death. A patient who is dying may be referred to as “circling the drain,” meaning that they are approaching death. People in nursing homes may live as socially dead for years with no one visiting or calling. Social support is important for quality of life and those who experience social death are deprived from the benefits that come from loving interaction with others.

Psychological death occurs when the dying person begins to accept death and to withdraw from others and regress into the self. This can take place long before physiological death (or even social death if others are still supporting and visiting the dying person) and can even bring physiological death closer. People have some control over the timing of their death and can hold on until after important occasions or die quickly after having lost someone important to them. In some cases, individuals can give up their will to live. This is often at least partially attributable to a lost sense of identity. The individual feels consumed by the reality of making final decisions, planning for loved ones—especially children, and coping with the process of his or her own physical death.

Interventions based on the idea of self-empowerment enable patients and families to identify and ultimately achieve their own goals of care, thus producing a sense of empowerment. Self-empowerment for terminally ill individuals has been associated with a perceived ability to manage and control things such as medical actions, changing life roles, and psychological impacts of the illness.

Treatment plans that are able to incorporate a sense of control and autonomy into the dying individual’s daily life have been found to be particularly effective in regards to general attitude as well as depression level. For example, it has been found that when dying individuals are encouraged to recall situations from their lives in which they were active decision makers, explored various options, and took action, they tend to have better mental health than those who focus on themselves as victims. Similarly, there are several theories of coping that suggest active coping (seeking information, working to solve problems) produces more positive outcomes than passive coping (characterized by avoidance and distraction). Although each situation is unique and depends at least partially on the individual’s developmental stage, the general consensus is that it is important for caregivers to foster a supportive environment and partnership with the dying individual, which promotes a sense of independence, control, and self-respect.

A Good Death

There are many variations in how people and cultures approach death and dying, but most of us can agree we want a “good” death. Meier et al (2017) reviewed research literature looking at what elements constitute a good death and found components including being free of pain or discomfort; having preferences about specifics, like how and where the death occurred, and religious or spiritual aspects, respected; feeling supported emotionally; being able to say goodbye to loved ones; and having dignity. Meier’s research also noted healthcare providers, family members, and the dying person each empathized slightly different components. For example, spirituality came up more often for the dying person but less so for family members and providers whereas dignity came up more for family members and less for the dying person.

In a different study, 10 domains of a good death were identified: (1) environmental comfort (2) life completion (3) dying in a favorite place, (4) maintaining hope and pleasure, (5) independence, (5) physical and psychological comfort, (7) good relationship with medical staff, (8) not being a burden to others, (9) good relationship with family, and (10) being respected as an individual (Miyashita et al. 2008, p. 491)

Overall, research has found several themes that define a “good death” when nurses and the interdisciplinary team are caring for dying patients and their families:

- Patient preferences are met, including preferences for the dying process (i.e., where and with whom) and preparation for death (i.e., advanced directives, funeral arrangements).

- The patient is pain-free with emotional well-being.

- The family is prepared for death and supportive of patient’s preferences.

- Dignity and respect are demonstrated for the patient.

- The patient has a sense of life completion (i.e., saying goodbye and feeling life was well-lived).

- Spirituality and religious comfort are provided.

- Quality of life was maintained (i.e., maintaining hope, pleasure, gratitude)

- There is a feeling of trust/support/comfort from the nurse and interdisciplinary team.

LISTEN TO THIS: Listen to “Dying Well” a TED radio hour podcast that explores how to talk about death candidly and without fear.

Bereavement and Grief

What is bereavement and grief?

Grief is the psychological, physical, and emotional experience and reaction to loss. People may experience grief in various ways, but several theories, such as Kübler-Ross’ stages of loss theory, attempt to explain and understand the way people deal with grief. Kübler-Ross’ famous theory, which we’ll examine in more detail soon, describes five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Grief reactions vary depending on whether a loss was anticipated or unexpected, (parents do not expect to lose their children, for example), and whether or not it occurred suddenly or after a long illness, and whether or not the survivor feels responsible for the death. Struggling with the question of responsibility is particularly felt by those who lose a loved one to suicide. These survivors may torment themselves with endless “what ifs” in order to make sense of the loss and reduce feelings of guilt. And family members may also hold one another responsible for the loss. The same may be true for any sudden or unexpected death, making conflict an added dimension to grief. Much of this laying of responsibility is an effort to think that we have some control over these losses; the assumption being that if we do not repeat the same mistakes, we can control what happens in our life. While grief describes the response to loss, bereavement describes the state of being following the death of someone.

As we’ve already learned in terms of attitudes toward death, individuals’ own lifespan developmental stage and cognitive level can influence their emotional and behavioral reactions to the death of someone they know. But what about the impact of the type of death or age of the deceased or relationship to the deceased upon bereavement?

Bereavement and relationships

Death of a child

Death of a child can take the form of a loss in infancy such as miscarriage or stillbirth or neonatal death, SIDS, or the death of an older child. In most cases, parents find the grief almost unbearably devastating, and it tends to hold greater risk factors than any other loss. This loss also bears a lifelong process: one does not get ‘over’ the death but instead must assimilate and live with it. Intervention and comforting support can make all the difference to the survival of a parent in this type of grief but the risk factors are great and may include family breakup or suicide. Feelings of guilt, whether legitimate or not, are pervasive, and the dependent nature of the relationship disposes parents to a variety of problems as they seek to cope with this great loss. Parents who suffer miscarriage or a regretful or coerced abortion may experience resentment towards others who experience successful pregnancies.

Suicide

Suicide rates are growing worldwide and over the last thirty years there has been international research trying to curb this phenomenon and gather knowledge about who is “at-risk”. When a parent loses their child through suicide it is traumatic, sudden, and affects all loved ones impacted by this child. Suicide leaves many unanswered questions and leaves most parents feeling hurt, angry and deeply saddened by such a loss. Parents may feel they can’t openly discuss their grief and feel their emotions because of how their child died and how the people around them may perceive the situation. Parents, family members and service providers have all confirmed the unique nature of suicide-related bereavement following the loss of a child. They report a wall of silence that goes up around them and how people interact towards them. One of the best ways to grieve and move on from this type of loss is to find ways to keep that child as an active part of their lives. It might be privately at first but as parents move away from the silence they can move into a more proactive healing time.

Death of a spouse

The death of a spouse is usually a particularly powerful loss. A spouse often becomes part of the other in a unique way: many widows and widowers describe losing ‘half’ of themselves. The days, months and years after the loss of a spouse will never be the same and learning to live without them may be harder than one would expect. The grief experience is unique to each person. Sharing and building a life with another human being, then learning to live singularly, can be an adjustment that is more complex than a person could ever expect. Depression and loneliness are very common. Feeling bitter and resentful are normal feelings for the spouse who is “left behind”. Oftentimes, the widow/widower may feel it necessary to seek professional help in dealing with their new life.

After a long marriage, it may be a very difficult assimilation to begin anew. A marriage relationship was often a profound one for the survivor.

Furthermore, most couples have a division of ‘tasks’ or ‘labor’, e.g., one spouse mows the yard, while the other pays the bills, etc. which, in addition to dealing with great grief and life changes, means added responsibilities for the bereaved. Immediately after the death of a spouse, there are tasks that must be completed. Planning and financing a funeral can be very difficult if pre-planning was not completed. Changes in insurance, bank accounts, claiming of life insurance, securing childcare are just some of the issues that can be intimidating to someone who is grieving. Social isolation may also become imminent, as many groups composed of couples find it difficult to adjust to the new identity of the bereaved, and the bereaved themselves have great challenges in reconnecting with others. Widows of many cultures, for instance, wear black for the rest of their lives to signify the loss of their spouse and their grief. Only in more recent decades has this tradition been reduced to shorter periods of time.

Death of a parent

For a child, the death of a parent, without support to manage the effects of the grief, may result in long-term psychological harm. This is more likely if the adult carers are struggling with their own grief and are psychologically unavailable to the child. There is a critical role of the surviving parent or caregiver in helping the children adapt to a parent’s death. Studies have shown that losing a parent at a young age did not just lead to negative outcomes; there are some positive effects. Some children had an increased maturity, better coping skills and improved communication. Adolescents valued other people more than those who have not experienced such a close loss.

When an adult child loses a parent in later adulthood, it is considered to be “timely” and to be a normative life course event. This allows the adult children to feel a permitted level of grief. However, research shows that the death of a parent in an adult’s midlife is not a normative event by any measure, but is a major life transition causing an evaluation of one’s own life or mortality. Others may shut out friends and family in processing the loss of someone with whom they have had the longest relationship.

Death of a sibling

The loss of a sibling can be a devastating life event. Despite this, sibling grief is often the most disenfranchised or overlooked of the four main forms of grief, especially with regard to adult siblings. Grieving siblings are often referred to as the ‘forgotten mourners’ who are made to feel as if their grief is not as severe as their parents grief (N.a., 2015). However, the sibling relationship tends to be the longest significant relationship of the lifespan and siblings who have been part of each other’s lives since birth, such as twins, help form and sustain each other’s identities; with the death of one sibling comes the loss of that part of the survivor’s identity because “your identity is based on having them there.”

The sibling relationship is a unique one, as they share a special bond and a common history from birth, have a certain role and place in the family, often complement each other, and share genetic traits. Siblings who enjoy a close relationship participate in each other’s daily lives and special events, confide in each other, share joys, spend leisure time together (whether they are children or adults), and have a relationship that not only exists in the present but often looks toward a future together (even into retirement). Surviving siblings lose this “companionship and a future” with their deceased siblings.

Loss during childhood

When a parent or caregiver dies or leaves, children may have symptoms of psychopathology, but they are less severe than in children with major depression. The loss of a parent, grandparent or sibling can be very troubling in childhood, but even in childhood there are age differences in relation to the loss. A very young child, under one or two, may be found to have no reaction if a carer dies, but other children may be affected by the loss.

At a time when trust and dependency are formed, a break or separation can cause problems in well-being; this is especially true if the loss is around critical periods such as 8–12 months, when attachment and separation are at their height information, and even a brief separation from a parent or other person who cares for the child can cause distress.

Even as a child grows older, death is still difficult to fathom and this affects how a child responds. For example, younger children see death more as a separation, and may believe death is curable or temporary. Reactions can manifest themselves in “acting out” behaviors: a return to earlier behaviors such as sucking thumbs, clinging to a toy or angry behavior; though they do not have the maturity to mourn as an adult, they feel the same intensity. As children enter pre-teen and teen years, there is a more mature understanding.

Children can experience grief as a result of losses due to causes other than death. For example, children who have been physically, psychologically or sexually abused often grieve over the damage to or the loss of their ability to trust. Since such children usually have no support or acknowledgement from any source outside the family unit, this is likely to be experienced as disenfranchised grief.

Relocations can also cause children significant grief particularly if they are combined with other difficult circumstances such as neglectful or abusive parental behaviors, other significant losses, etc.

Loss of a friend or classmate

Children may experience the death of a friend or a classmate through illness, accidents, suicide, or violence. Initial support involves reassuring children that their emotional and physical feelings are normal. Schools are advised to plan for these possibilities in advance.

Types of grief

Survivor guilt (or survivor’s guilt; also called survivor syndrome or survivor’s syndrome) is a mental condition that occurs when a person perceives themselves to have done wrong by surviving a traumatic event when others did not. It may be found among survivors of combat, natural disasters, epidemics, among the friends and family of those who have died by suicide, and in non-mortal situations such as among those whose colleagues are laid off.

Anticipatory grief occurs when a death is expected and survivors have time to prepare to some extent before the loss. Anticipatory grief can include the same denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance experienced in loss one might experience after a death; this can make adjustment after a loss somewhat easier, although a person may then go through the stages of loss again after the death. A death after a long-term, painful illness may bring family members a sense of relief that the suffering is over or the exhausting process of caring for someone who is ill is over.

Complicated grief involves a distinct set of maladaptive or self-defeating thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that occur as a negative response to a loss. From a cognitive and emotional perspective, these individuals tend to experience extreme bitterness over the loss, intense preoccupation with the deceased, and a need to feel connected to the deceased. These feelings often lead the grieving individual to engage in problematic behaviors that further prevent positive coping and delay the return to normalcy. They may spend excessive amounts of time visiting the deceased person’s grave, talking to the deceased person, or trying to connect with the deceased person on a spiritual level, often forgoing other responsibilities or tasks to do so. The extreme nature of these thoughts, emotions, and behaviors separate this type of grief from the normal grieving process.

Disenfranchised grief may be experienced by those who have to hide the circumstances of their loss or whose grief goes unrecognized by others. Loss of an ex-spouse, lover, or pet may be examples of disenfranchised grief. It has been said that intense grief lasts about two years or less, but grief is felt throughout life. One loss triggers the feelings that surround another. People grieve with varied intensity throughout the remainder of their lives. It does not end. But it eventually becomes something that a person has learned to live with. As long as we experience loss, we experience grief.

There are layers of grief. Initial denial, marked by shock and disbelief in the weeks following a loss may become an expectation that the loved one will walk in the door. And anger directed toward those who could not save our loved one’s life, may become anger that life did not turn out as we expected. There is no right way to grieve. A bereavement counselor expressed it well by saying that grief touches us on the shoulder from time to time throughout life.

Grief and mixed emotions go hand in hand. A sense of relief is accompanied by regrets and periods of reminiscing about our loved ones are interspersed with feeling haunted by them in death. Our outward expressions of loss are also sometimes contradictory. We want to move on but at the same time are saddened by going through a loved one’s possessions and giving them away. We may no longer feel sexual arousal or we may want sex to feel connected and alive. We need others to befriend us but may get angry at their attempts to console us. These contradictions are normal and we need to allow ourselves and others to grieve in their own time and in their own ways.

The “death-denying, grief-dismissing world” is often the approach to grief in our modern world. We are asked to grieve privately, quickly, and to medicate our suffering. Employers grant us 3 to 5 days for bereavement, if our loss is that of an immediate family member. And such leaves are sometimes limited to no more than one per year. Yet grief takes much longer and the bereaved are seldom ready to perform well on the job. It becomes a clash between life having to continue, and the individual being ready for it to do so. One coping mechanism that can help smooth out this conflict is called the fading affect bias. Based on a collection of similar findings, the fading affect bias suggests that negative events, such as the death of a loved one, tend to lose their emotional intensity at a faster rate than pleasant events. This is believed to help enhance pleasant experiences and avoid the negative emotions associated with unpleasant ones, thus helping the individual return to their normal daily routines following a loss.

Models of Grief

There are several theoretical models of grief; however, none is all-encompassing (Youdin, 2016). These models are merely guidelines for what an individual may experience while grieving. However, if individuals do not fit a model, it does not mean there is something “wrong” with the way they experience grief. It is important to remember that there is no one way to grieve, and people move through a variety of stages of grief in various ways.

Five Stages of Grief:

Kübler-Ross (1969, 1975) describes five stages of loss experienced by someone who faces the news of their impending death. These “stages” are not really stages that a person goes through in order or only once; nor are they stages that occur with the same intensity. Indeed, the process of death is influenced by a person’s life experiences, the timing of their death in relation to life events, the predictability of their death based on health or illness, their belief system, and their assessment of the quality of their own life. Nevertheless, these stages help us to understand and recognize some of what a dying person experiences psychologically, and by understanding, we are more equipped to support that person as they die.

Denial is often the first reaction to overwhelming, unimaginable news. Denial, or disbelief or shock, protects us by allowing such news to enter slowly and to give us time to come to grips with what is taking place. The person who receives positive test results for life-threatening conditions may question the results, seek second opinions, or may simply feel a sense of disbelief psychologically even though they know that the results are true.

Anger also provides us with protection in that being angry energizes us to fight against something and gives structure to a situation that may be thrusting us into the unknown. It is much easier to be angry than to be sad, in pain, or depressed. It helps us to temporarily believe that we have a sense of control over our future and to feel that we have at least expressed our rage about how unfair life can be. Anger can be focused on a person, a health care provider, at God, or at the world in general. It can be expressed over issues that have nothing to do with our death; consequently, being in this stage of loss is not always obvious.

Bargaining involves trying to think of what could be done to turn the situation around. Living better, devoting oneself to a cause, or being a better friend, parent, or spouse, are all agreements one might willingly commit to if doing so would lengthen life. Asking to just live long enough to witness a family event or finish a task are examples of bargaining.

Depression or sadness is appropriate for such an event. Feeling the full weight of loss, crying, and losing interest in the outside world is an important part of the process of dying. This depression makes others feel very uncomfortable and family members may try to console their loved one. Sometimes hospice care may include the use of antidepressants to reduce depression during this stage.

Acceptance involves learning how to carry on and to incorporate this aspect of the life span into daily existence. Reaching acceptance does not in any way imply that people who are dying are happy about it or content with it. It means that they are facing it and continuing to make arrangements and to say what they wish to say to others. Some terminally ill people find that they live life more fully than ever before after they come to this stage.

According to Kübler-Ross (1969), behind these five stages focused on the identified emotions, there is a sense of hope. Kübler-Ross noted that in all the 200-plus patients she and her students interviewed, a little bit of hope that they might not die was always in the back of their minds.

Criticisms of Kübler-Ross’s Five Stages of Grief:

Some researchers have been skeptical of the validity of there being stages to grief among the dying (Friedman & James, 2008). As Kübler-Ross notes in her own work, it is difficult to empirically test the experiences of the dying. “How do you do research on dying,…? When you cannot verify your data and cannot set up experiments?” (Kübler-Ross, 1969, p. 19). She and four students from the Chicago Theology Seminary in 1965 decided to listen to the experiences of dying patients, but her ideas about death and dying are based on the interviewers’ collective “feelings” about what the dying were experiencing and needed (Kübler-Ross, 1969). While she goes on to say in support of her approach that she and her students read nothing about the prior literature on death and dying, so as to have no preconceived ideas, a later work revealed that her own experiences of grief from childhood undoubtedly colored her perceptions of the grieving process (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). Kübler-Ross is adamant in her theory that the one stage that all those who are dying go through is anger. It is clear from her 2005 book that anger played a central role in “her” grief and did so for many years (Friedman & James, 2008).

There have been challenges to the notion that denial and acceptance are beneficial to the grieving process (Telford et al., 2006). Denial can become a barrier between the patient and health care specialists and reduce the ability to educate and treat the patient. Similarly, acceptance of a terminal diagnosis may also lead patients to give up and forgo treatments to alleviate their symptoms. In fact, some research suggests that optimism about one’s prognosis may help in one’s adjustment and increase longevity (Taylor, Kemeny, Reed, Bower & Gruenewald, 2000).

A third criticism is not so much of Kübler-Ross’s work, but how others have assumed that these stages apply to anyone who is grieving. Her research focused only on those who were terminally ill. This does not mean that others who are grieving the loss of someone would necessarily experience grief in the same way. Friedman and James (2008) and Telford et al. (2006) expressed concern that mental health professionals, along with the general public, may assume that grief follows a set pattern, which may create more harm than good.

Lastly, the Yale Bereavement Study, completed between January 2000 and January 2003, did not find support for Kübler-Ross’s five stage theory of grief (Maciejewski et al., 2007). Results indicated that acceptance was the most commonly reported reaction from the start, and yearning was the most common negative feature for the first two years. The other variables, such as disbelief, depression, and anger, were typically absent or minimal.

Although there is criticism of the Five Stages of Grief Model, Kübler-Ross made people more aware of the needs and concerns of the dying, especially those who were terminally ill. As she notes,

…when a patient is severely ill, he is often treated like a person with no right to an opinion. It is often someone else who makes the decision if and when and where a patient should be hospitalized. It would take so little to remember that the sick person has feelings, has wishes and opinions, and has—most important of all—the right to be heard. (1969, p. 7-8).

Dual-Process Model of Grieving:

The dual-process model takes into consideration that bereaved individuals move back and forth between grieving and preparing for life without their loved one (Stroebe & Schut, 2001; Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2005). This model focuses on a loss orientation, which emphasizes the feelings of loss and yearning for the deceased, and a restoration orientation, which centers on the grieving individual reestablishing roles and activities they had prior to the death of their loved one. When oriented toward loss grieving individuals look back, and when oriented toward restoration they look forward. As one cannot look both back and forward at the same time, a bereaved person must shift back and forth between the two. Both orientations facilitate normal grieving and interact until bereavement has completed.

Dealing with grief

VIEW THIS “Grief Reactions Over the Life Span” from the American Counseling Association to consider how various age groups deal with the death of a loved one.

We no longer think that there is a “right way” to experience grief and loss. People move through a variety of stages with different frequency and in different ways. The theories that have been developed to help explain and understand this complex process have shifted over time to encompass a wider variety of situations, as well as to present implications for helping and supporting the individual(s) who are going through it. The following strategies have been identified as effective in the support of healthy grieving:

Talk about the death. This will help the surviving individuals understand what happened and remember the deceased in a positive way. When coping with death, it can be easy to get wrapped up in denial, which can lead to isolation and lack of a solid support system.

Accept the multitude of feelings. The death of a loved one can, and almost always does, trigger numerous emotions. It is normal for sadness, frustration, and in some cases exhaustion to be experienced.

Take care of yourself and your family. Remembering to keep one’s own health and the health of their family a priority can help with moving through each day effectively. Making an conscious effort to eat well, exercise regularly, and obtain adequate rest is important.

Reach out and help others dealing with the loss. It has long been recognized that helping others can enhance one’s own mood and general mental state. Helping others as they cope with the loss can have this effect, as can sharing stories of the deceased.

Remember and celebrate the lives of your loved ones. This can be a great way to honor the relationship that was once had with the deceased. Possibilities can include donating to a charity that the deceased supported, framing photos of fun experiences with the deceased, planting a tree or garden in memory of the deceased, or anything else that feels right for the particular situation.

WATCH THIS TEDx Talk below or online with captions by Sociologist Nancy Berns contradicting the idea that people need closure in order to “move on.”

Mourning

Mourning is the outward, social expression of loss. Individuals outwardly express loss based on their cultural norms, customs, and practices, including rituals and traditions. Some cultures may be very emotional and verbal in their expression of loss, such as wailing or crying loudly. Other cultures are stoic and show very little reaction to loss. Culture also dictates how long one mourns and how the mourners “should” act. The expression of loss is also affected by an individual’s personality and previous life experiences.

Regardless of variations in conceptions and attitudes toward death, ceremonies provide survivors a sense of closure after a loss. These rites and ceremonies send the message that the death is real and allow friends and loved ones to express their love and duty to those who die. Under circumstances in which a person has been lost and presumed dead or when family members were unable to attend a funeral, there can continue to be a lack of closure that makes it difficult to grieve and to learn to live with loss. And although many people are still in shock when they attend funerals, the ceremony still provides a marker of the beginning of a new period of one’s life as a survivor.

As a society, are we given the tools and time to adequately mourn? Not all researchers agree that we do. The “death-denying, grief-dismissing world” is the modern world (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005, p. 205). We often grieve privately, quickly, and medicate our suffering with substances or activities. Employers may grant 3 to 5 days for bereavement, if the loss is that of an immediate family member. Yet grief takes much longer and the bereaved are seldom ready to perform well on the job after just a few days. Obviously, life does have to continue, but we need to acknowledge and make more caring accommodations for those who are in grief.

Four Tasks of Mourning:

Worden (2008) identified four tasks that facilitate the mourning process. Worden believes that all four tasks must be completed, but they may be completed in any order and for varying amounts of time. These tasks include:

- Acceptance that the loss has occurred

- Working through the pain of grief

- Adjusting to life without the deceased

- Starting a new life while still maintaining a connection with the deceased

PROLONGED GRIEF DISORDER

In March 2022, prolonged grief disorder (PGD) was added as a mental disorder in the DSM-5-TR. It is characterized by a distinct set of symptoms following the death of a family member or close friend (ie. bereavement). People with PGD are preoccupied with grief and feelings of loss to the point of clinically significant distress and impairment, which can manifest in a variety of symptoms including depression, emotional pain, emotional numbness, loneliness, identity disturbance, and difficulty in managing interpersonal relationships. Difficulty accepting the loss is also common, which can present as rumination about the death, a strong desire for reunion with the departed, or disbelief that the death occurred. PGD is estimated to be experienced by about 10 percent of bereaved survivors, although rates vary substantially depending on populations sampled and definitions used.

Along with bereavement of the individual occurring at least one year ago (or six months in children and adolescents), there must be evidence of one of two “grief responses” occurring at least daily for the past month:

- Intense yearning/longing for the deceased person.

- Preoccupation with thoughts or memories of the deceased person (in children and adolescents, preoccupation may focus on the circumstances of the death).

Additionally, the individual must have at least three of the following symptoms occurring at least daily for the past month:

- Identity disruption (e.g., feeling as though part of oneself has died) since the death

- A marked sense of disbelief about the death

- Avoidance of reminders that the person is dead (in children and adolescents, may be characterized by efforts to avoid reminders)

- Intense emotional pain (e.g., anger, bitterness, sorrow) related to the death

- Difficulty reintegrating into one’s relationships and activities after the death (e.g., problems engaging with friends, pursuing interests, or planning for the future)

- Emotional numbness (absence or marked reduction of emotional experience) as a result of the death

- Feeling that life is meaningless as a result of the death

- Intense loneliness as a result of the death

The duration and severity of the distress and impairment in PGD must be clinically significant, and not better explainable by social, cultural, or religious norms, or another mental disorder. PGD can be distinguished from depressive disorders with distress appearing specifically about the bereaved as opposed to a generally low mood. According to Holly Prigerson, an editor on the trauma and stressor-related disorder section of the DSM-5-TR, “intense, persistent yearning for the deceased person is specifically a characteristic symptom of PG [prolonged grief], but is not a symptom of MDD (or any other DSM disorder).”

Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide

Euthanasia , or helping a person fulfill their wish to die, can happen in two ways: voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Voluntary euthanasia refers to helping someone fulfill their wish to die by acting in such a way to help that person’s life end. This can be passive euthanasia such as no longer feeding someone or giving them food. Or it can be active euthanasia such as administering a lethal dose of medication to someone who wishes to die. In some cases, a dying individual who is in pain or constant discomfort will ask this of a friend or family member, as a way to speed up what he or she has already accepted as being inevitable. This can have lasting effects on the individual or individuals asked to help, including but not limited to prolonged guilt.

Physician-Assisted Suicide: Physician-assisted suicide occurs when a physician prescribes the means by which a person can end his or her own life. This differs from euthanasia, in that it is mandated by a set of laws and is backed by legal authority. Physician-assisted suicide is legal in the District of Columbia and several states, including Oregon, Hawaii, Vermont, and Washington. It is also legal in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium.

WATCH THIS video clip below or online with captions about Dr. Jack Kevorkian, the individual most commonly associated with physician-assisted suicide. He was a pioneer in this practice, sparking ethical, moral, and legal debates that continue to this day. This video provides an overview of his work, and his role in the beginning of physician-assisted suicide.

The specific laws that govern the practice of physician-assisted suicide vary between states. Oregon, Vermont, and Washington, for example, require the prescription to come from either a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) or a Doctor of Osteopathy (D.O.). These state laws also include a clause about the designated medical practitioner being willing to participate in this act. In Colorado, terminally ill individuals have the option to request and self-administer life-ending medication if their medical prognosis gives them six months or less to live. In the District of Columbia and Hawaii, the individual is required to make two requests within predefined periods of time and also complete a waiting period, and in some cases undergo additional evaluations before the medication can be provided.

A growing number of the population support physician-assisted suicide. In 2000, a ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the right of states to determine their laws on physician-assisted suicide despite efforts to limit physicians’ ability to prescribe barbiturates and opiates for their patients requesting the means to end their lives. The position of the Supreme Court is that the debate concerning the morals and ethics surrounding the right to die is one that should be continued. As an increasing number of the population enters late adulthood, the emphasis on giving patients an active voice in determining certain aspects of their own death is likely.

In a recent example of physician-assisted death, David Goodall, a 104-year-old professor, ended his life by choice in a Swiss clinic in May 2018. Having spent his life in Australia, Goodall traveled to Switzerland to do this, as the laws in his country do not allow for it. Swiss legislation does not openly permit physician-assisted suicide, but it does not forbid an individual with “commendable motives” from assisting another person in taking his or her own life.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions of a news conference with Goodall that took place the day before he ended his life with physician-assisted suicide.

Another public advocate for physician-assisted suicide and death with dignity was 29-year old Brittany Maynard, who after being diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, decided to move to Oregon so that she could end her life with physician-assisted suicide.

WATCH THIS: You can watch “The Brittany Maynard Story” to learn more about Brittany’s story. Watch here with captions.

Hospice and Palliative Care

Palliative care focuses on providing comfort and relief from physical and emotional pain to patients throughout their illness even while being treated (NIH, 2007). Palliative care is part of hospice programs. Hospice involves caring for dying patients by helping them be as free from pain as possible, providing them with assistance to complete wills and other arrangements for their survivors, giving them social support through the psychological stages of loss, and helping family members cope with the dying process, grief, and bereavement. In order to enter hospice, a patient must be diagnosed as terminally ill with an anticipated death within 6 months. Most hospice care does not include medical treatment of disease or resuscitation although some programs administer curative care as well. The patient is allowed to go through the dying process without invasive treatments. Family members, who have agreed to put their loved one on hospice, may become anxious when the patient begins to experience the death. They may believe that feeding or breathing tubes will sustain life and want to change their decision. Hospice workers try to inform the family of what to expect and reassure them that much of what they see is a normal part of the dying process.

The early hospices established were independently operated and dedicated to giving patients as much control over their own death process as possible. Today, there are more than 4,000 hospice programs and over 1,000 of them are offered through hospitals. Hospice care was given to over 1 million patients in 2004 (NIH, 2007; Senior Journal, 2007). Although hospice care has become more widespread, these new programs are subjected to more rigorous insurance guidelines that dictate the types and amounts of medications used, length of stay, and types of patients who are eligible to receive hospice care (Weitz, 2007). Thus, more patients are being served, but providers have less control over the services they provide, and lengths of stay are more limited. Patients receive palliative care in hospitals and in their homes.

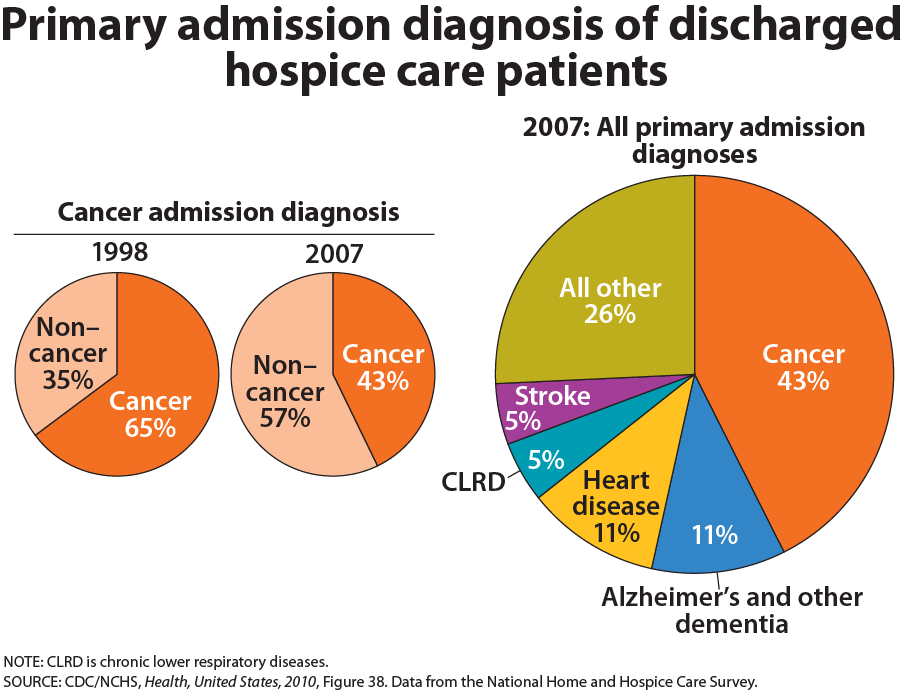

The majority of patients on hospice are cancer patients and typically do not enter hospice until the last few weeks prior to death. The average length of stay is less than 30 days and many patients are on hospice for less than a week (National Center for Health Statistics, 2003). Medications are rubbed into the skin or given in drop form under the tongue to relieve the discomfort of swallowing pills or receiving injections. A hospice care team includes a chaplain as well as nurses and grief counselors to assist spiritual needs in addition to physical ones. When hospice is administered at home, family members may also be part, and sometimes the biggest part, of the care team. Certainly, being in familiar surroundings is preferable to dying in an unfamiliar place. But about 60 to 70 percent of people die in hospitals and another 16 percent die in institutions such as nursing homes (APA Online, 2001). Most hospice programs serve people over 65; few programs are available for terminally ill children (Wolfe et al., in Berger, 2005).

Dame Cicely Saunders founded the hospice movement in Great Britain and described the kinds of pain experienced by those who are dying and their families. These 7 Pains include emotional include physical pain, spiritual pain, intellectual pain, emotional pain, interpersonal pain, financial pain and bureaucratic pain. Hospice care focuses on alleviating physical pain and providing spiritual guidance. Those suffering from Alzheimer’s also experience intellectual pain and frustration as they lose their ability to remember and recognize others. Depression, anger, and frustration are elements of emotional pain, and family members can have tensions that a social worker or clergy member may be able to help resolve. Many patients are concerned with the financial burden their care will create for family members. And bureaucratic pain is also suffered while trying to submit bills and get information about health care benefits or to complete requirements for other legal matters. All of these concerns can be addressed by hospice care teams. Learn more about Saunders in the link provided at the end of this lesson.

The Hospice Foundation of America notes that not all racial and ethnic groups feel the same way about hospice care. African-American families may believe that medical treatment should be pursued on behalf of an ill relative as long as possible and that only God can decide when a person dies. Chinese-American families may feel very uncomfortable discussing issues of death or being near the deceased family member’s body. The view that hospice care should always be used is not held by everyone and health care providers need to be sensitive to the wishes and beliefs of those they serve (Hospital Foundation of America, 2009).

Nursing and Death Anxiety

While health care environments throughout the developed world have expanded the use of technology and advanced sophisticated treatments to manage serious conditions, many patients facing trauma and life-threatening conditions experience death in institutional settings. Nurses play critical roles globally in preventing death, and they help patients and their family members with advanced directives, and end of life decision-making. Nurses may become anxious and feel overwhelmed with the work stressors associated with death and dying. Furthermore, nurses may feel unprepared to communicate effectively with patients who are dying and their family members. In some work environments such as the emergency room setting, workload demands may compromise the nurses’ ability to facilitate dignified end of life care.

Death anxiety is a multidimensional construct with emotional, cognitive, and experiential attributes. In Lehto and Stein’s review of the death anxiety literature, it was noted that developmental and sociocultural factors such as age, gender, and religiosity influence its expression. Life experiences with death may also impact attitudes about death and contribute to lower levels of death anxiety. While the fear of death is pervasive in humans, personal death and the experience of death anxiety may be denied and/or avoided. Importantly, it is recognized that death anxiety brings about important behavioral and emotional consequences. The attitude of nurses towards death may affect their empathic concern, the quality of care they provide, and the way they cope with work-related stressors such as patients’ death. While nurses and other health care professionals may have positive intentions to provide the highest quality care for patients facing death, they may have fears related to death that may negatively influence their attitudes about providing care. Furthermore, caring for dying patients may lead to grief and perceptions of failure, which also evoke heightened anxiety about managing death situations in the work environment.

Self-Care

It is important for nurses to recognize that providing end-of-life care can have a significant impact on them. A nurse’s grief might be exacerbated when patient loss is unexpected or is the result of a traumatic experience. For example, an emergency room nurse who provides care for a child who died as a result of a motor vehicle accident may find it difficult to cope with the loss and resume their normal work duties.

Grief can also be compounded when loss occurs repeatedly in one’s work setting or after providing care for a patient for a long period of time. In some health care settings, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses do not have time to resolve grief from a loss before another loss occurs. Compassion fatigue and burnout occur frequently with nurses and other health care professionals who experience cumulative losses that are not addressed therapeutically.

Compassion fatigue is a state of chronic and continuous self-sacrifice and/or prolonged exposure to difficult situations that affect a health care professional’s physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. This can lead to a person being unable to care for or empathize with someone’s suffering. Burnout can be manifested physically and psychologically with a loss of motivation. It can be triggered by workplace demands, lack of resources to do work professionally and safely, interpersonal relationship stressors, or work policies that can lead to diminished caring and cynicism.

Burnout

Self-care is important to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. It is important for nurses to recognize the need to take time off, seek out individual healthy coping mechanisms, or voice concerns within their workplace. Prayer, meditation, exercise, art, and music are examples of healthy coping mechanisms that nurses can use to progress through their individual grief experience. Additionally, many organizations sponsor employee assistance programs that provide counseling services. These programs can be of great value and benefit in allowing individuals to voice their individual challenges with patient loss. In times of traumatic patient loss, many organizations hold debriefing sessions to allow individuals who participated in the care to come together to verbalize their feelings. These sessions are often held with the support of chaplains to facilitate individual coping and verbalization of feelings.

Throughout your nursing career, there will be times to stop and pay attention to warning signs of compassion fatigue and burnout. Here are some questions to consider:

- Has my behavior changed?

- Do I communicate differently with others?

- What destructive habits tempt me?

- Do I project my inner pain onto others?

By becoming self-aware, you can implement self-care strategies to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Use the following “A’s” to assist in building resilience, connection, and compassion:

- Attention: Become aware of your physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health. What are you grateful for? What are your areas of improvement? This protects you from drifting through life on autopilot.

- Acknowledgement: Honestly look at all you have witnessed as a health care professional. What insight have you experienced? Acknowledging the pain of loss you have witnessed protects you from invalidating the experiences.

- Affection: Choose to look at yourself with kindness and warmth. Affection prevents you from becoming bitter and “being too hard” on yourself.

- Acceptance: Choose to be at peace and welcome all aspects of yourself. By accepting both your talents and imperfections, you can protect yourself from impatience, victim mentality, and blame.

READ THIS Read more about online end-of-life curriculum available on the American Association of Colleges of Nursing’s End-of-Life-Care Curriculum web page.

References and Resources

Listed below are the references and resources used to curate this module:

Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2021). Grief and loss. In Nursing Fundamentals [Internet]. Eau Claire, WI: Chippewa Valley Technical College. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591827/

Lally, M., & Valentine-French, S. (n.d.). Death and dying. In Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective (4th ed.). Retrieved June 22, 2024, from https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Human_Development/Lifespan_Development%3A_A_Psychological_Perspective_4e_(Lally_and_Valentine-French)/10%3A_Death_and_Dying

LibreTexts. (n.d.). A global perspective on aging. In Introduction to Sociology. Retrieved June 22, 2024, from https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Sociology/Introduction_to_Sociology/Sociology_(Boundless)/18%3A_Aging/18.02%3A_A_Global_Perspective_on_Aging/18.2A%3A_The_Social_Construction_of_Aging

Lowey, S.E.. (n.d.). Diversity in dying: Death across cultures. In Nursing Care at the End of Life. Retrieved June 22, 2024, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-nursing-care-at-the-end-of-life/chapter/diversity-in-dying-death-across-cultures/

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Attitudes about death. In Lifespan Development. Retrieved June 22, 2024, from https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Human_Development/Lifespan_Development_(Lumen)/11%3A_Death_and_Dying/11.06%3A_Attitudes_about_Death

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Bereavement and grief. In Childhood Psychology. Retrieved June 22, 2024, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-fmcc-childhood-psychology/chapter/bereavement-and-grief/