11 Module 11: Late Adulthood Development

Module 11 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Describe Late Adulthood

Explain the age categories within late adulthood and how they relate to physical, emotional, and functional well-being. - Understand Life Expectancy Trends

Discuss factors that contribute to longer life expectancies, including genetics, health habits, and social factors. - Differentiate Aging Processes

Explain the differences between primary aging (inevitable biological changes) and secondary aging (caused by illness or lifestyle factors). - Examine Physical Changes

Identify key physical changes in late adulthood, such as vision, hearing, and muscle strength, and strategies to address them. - Explore Cognitive Development

Discuss how memory and cognitive functioning change during late adulthood, including conditions like Alzheimer’s and dementia. - Analyze Theories of Aging

Compare theories of aging, such as the peripheral slowing hypothesis and the free radical theory, and their implications for health. - Understand Psychosocial Development

Explain Erikson’s stage of integrity vs. despair and how it relates to life satisfaction in late adulthood. - Recognize Cultural Perspectives

Compare how different cultures view aging and the elderly, such as attitudes in the U.S. versus Japan. - Examine Social Roles and Relationships

Describe how family roles, friendships, and social networks change in late adulthood, including grandparenting and widowhood. - Promote Successful Aging

Discuss the concept of successful aging, including strategies like selective optimization with compensation and maintaining independence. - Address Health Challenges

Identify common health challenges in late adulthood, such as chronic illnesses and their management, including heart disease and diabetes. - Reflect on End-of-Life Issues

Examine societal attitudes about death and dying, and the importance of quality of life considerations in late adulthood.

Defining Late Adulthood: Age or Quality of Life?

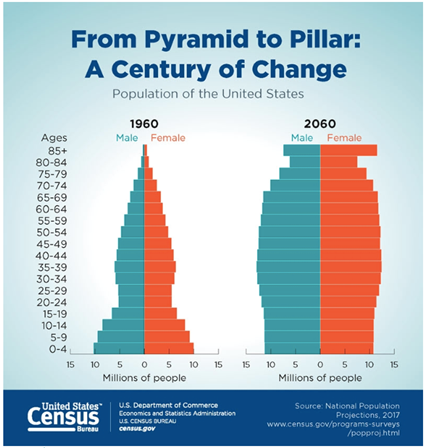

We are considered in late adulthood from the time we reach our mid-sixties until death. Because we are living longer, late adulthood is getting longer. Whether we start counting at 65, as demographers may suggest, or later, there is a greater proportion of people alive in late adulthood than anytime in world history. A 10-year-old child today has a 50 percent chance of living to age 104. Some demographers have even speculated that the first person ever to live to be 150 is alive today.

About 15.2 percent of the U.S. population or 49.2 million Americans are 65 and older. This number is expected to grow to 98.2 million by the year 2060, at which time people in this age group will comprise nearly one in four U.S. residents. Of this number, 19.7 million will be age 85 or older. Developmental changes vary considerably among this population, so it is further divided into categories of 65 plus, 85 plus, and centenarians for comparison by the census.

Demographers use chronological age categories to classify individuals in late adulthood. Developmentalists, however, divide this population in to categories based on physical and psychosocial well-being, in order to describe one’s functional age. The “young old” are healthy and active. The “old old” experience some health problems and difficulty with daily living activities. The “oldest old” are frail and often in need of care. A 98-year-old woman who still lives independently, has no major illnesses, and is able to take a daily walk would be considered as having a functional age of “young old”. Therefore, optimal aging refers to those who enjoy better health and social well-being than average.

Normal aging refers to those who seem to have the same health and social concerns as most of those in the population. However, there is still much being done to understand exactly what normal aging means. Impaired aging refers to those who experience poor health and dependence to a greater extent than would be considered normal. Aging successfully involves making adjustments as needed in order to continue living as independently and actively as possible. This is referred to as selective optimization with compensation. Selective Optimization with Compensation is a strategy for improving health and wellbeing in older adults and a model for successful aging. It is recommended that seniors select and optimize their best abilities and most intact functions while compensating for declines and losses. This means, for example, that a person who can no longer drive, is able to find alternative transportation, or a person who is compensating for having less energy, learns how to reorganize the daily routine to avoid overexertion. Perhaps nurses and other allied health professionals working with this population will begin to focus more on helping patients remain independent by optimizing their best functions and abilities rather than on simply treating illnesses. Promoting health and independence are essential for successful aging.

WATCH THIS: AGING SUCCESSFULLY

Systematic examination of old age is a new field inspired by the unprecedented number of people living longer. Developmental psychologists Paul and Margret Baltes have proposed a model of adaptive competence for the entire life span, but the emphasis here is on old age. Their model SOC (Selection, Optimization, and Compensation) is illustrated with engaging vignettes of people leading fulfilling lives, including writers Betty Friedan and Joan Erikson, and dancer Bud Mercer. Segments of the cognitive tests used by the Baltes in assessing the mental abilities of older people are shown. Although the video clip is old and dated, it remains an intellectually appealing video in which the Baltes discuss personality components that generally lead to positive aging experiences. Watch the video clip below or online. You can view the transcript for “Aging Successfully: The Psychological Aspects of Growing Old (Davidson Films, Inc.)” here.

Theories on Aging

Why do we age?

There are a number of attempts to explain why we age and many factors that contribute to aging. The peripheral slowing hypothesis suggests that overall processing speed declines in the peripheral nervous system, affecting the brain’s ability to communicate with muscles and organs. Some of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) is under a person’s voluntary control, such as the nerves carrying instructions from the brain to the limbs. As well as controlling muscles and joints, the PNS sends all the information from the senses back to the brain.

The generalized slowing hypothesis theory suggests that processing in all parts of the nervous system, including the brain, are less efficient with age. This may be why older people have more accidents. Genetics, diet, lifestyle, activity, and exposure to pollutants all play a role in the aging process.

Cell Life

Cells divide a limited number of times and then stop. This phenomenon, known as the Hayflick limit, is evidenced in cells studied in test tubes which divide about 50 times before becoming senescent. In 1961, Dr. Hayflick theorized that the human cell’s ability to divide is limited to approximately 50-times, after which they simply stop dividing (the Hayflick limit theory of aging). According to telomere theory, telomeres have experimentally been shown to shorten with each successive cell division.

Senescent cells do not die. They simply stop replicating. Senescent cells can help limit the growth of other cells which may reduce risk of developing tumors when younger, but can alter genes later in life and result in promoting the growth of tumors as we age (Dollemore, 2006). Limited cell growth is attributed to telomeres which are the tips of the protective coating around chromosomes. Each time cells replicate; the telomere is shortened. Eventually, loss of telomere length is thought to create damage to chromosomes and produce cell senescence.

WATCH THIS Ted talk below or online by molecular biologist Elizabeth Blackburn on “The Science of Cells That Never Get Old.” Blackburn won a Nobel Prize for her pioneering work on telomeres and telomerase, which may play central roles in how we age.

Biochemistry and Aging

Free Radical Theory of Aging

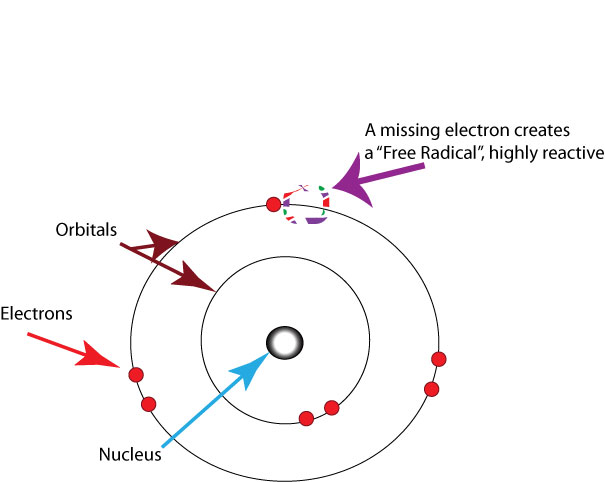

The free radical theory of aging (FRTA) states that organisms age because cells accumulate free radical damage over time. A free radical is any atom or molecule which has a single unpaired electron in an outer shell. This means that as oxygen is metabolized, mitochondria in the cells convert the oxygen to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) which provides energy to the cell. Unpaired electrons are a byproduct of this process and these unstable electrons cause cellular damage as they find other electrons with which to bond. These free radicals have some benefits and are used by the immune system to destroy bacteria. However, cellular damage accumulates and eventually reduces functioning of organs and systems. Many food products and vitamin supplements are promoted as age-reducing. Antioxidant drugs have been shown to increase the longevity in nematodes (small worms), but the ability to slow the aging process by introducing antioxidants in the diet is still controversial.

Protein Crosslinking

This theory focuses on the role blood sugar, or glucose, plays in the aging of cells. Glucose molecules attach themselves to proteins and form chains or crosslinks. These crosslinks reduce the flexibility of tissue and thus it becomes stiff and loses functioning. The circulatory system becomes less efficient as the tissue of the heart, arteries and lungs lose flexibility. Joints grow stiff as glucose combines with collagen.

DNA Damage

Through the normal growth and aging process, DNA is damaged by environmental factors such as toxic agents, pollutants, and sun exposure (Dollemore, 2006). This results in deletions of genetic material, and mutations in the DNA duplicated in new cells. The accumulation of these errors results in reduced functioning in cells and tissues. Theories that suggest that the body’s DNA genetic code contains a built-in time limit for the reproduction of human cells are called the genetic programming theories of aging. These theories promote the view that the cells of the body can only duplicate a certain number of times and that the genetic instructions for running the body can be read only a certain number of times before they become illegible. Such theories also promote the existence of a “death gene” which is programmed to direct the body to deteriorate and die, and the idea that a long life after the reproductive years is unnecessary for the survival of the species.

Decline in the Immune System

As we age, B-lymphocytes and T-lymphocytes become less active. These cells are crucial to the immune system as they secrete antibodies and directly attack infected cells. The thymus, where T-cells are manufactured, shrinks as aging progresses. This reduces our body’s ability to fight infection (Berger, 2005).

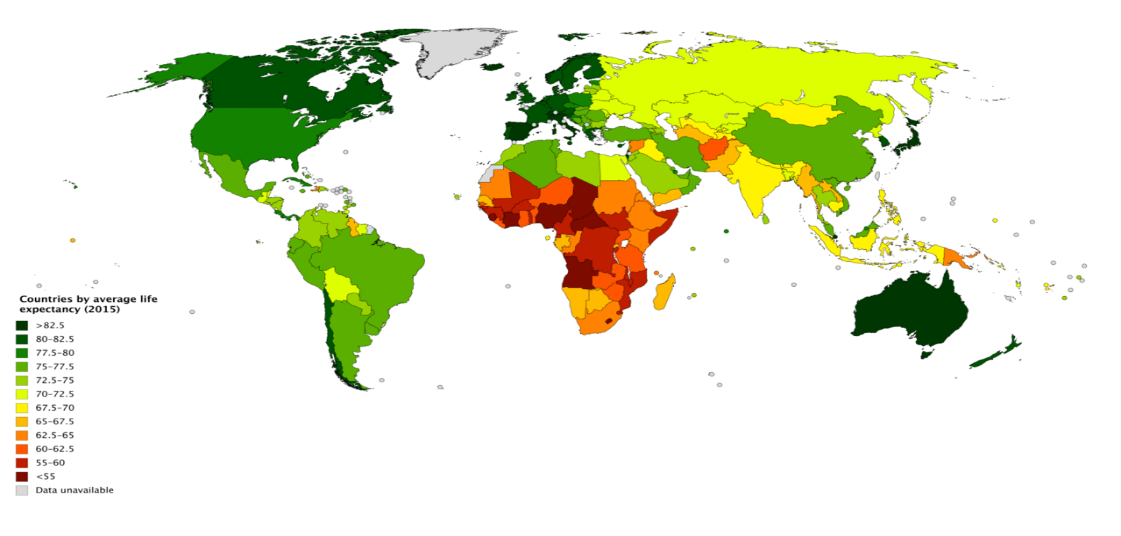

Aging as a Social Construction

While aging itself is a biological process, what it means to be “young” or “old” is socially constructed. This means that there is no inherent cultural meaning to the biological process of aging. Rather, cultures imbue youth and age with meanings. Aging is perceived differently around the world, demonstrating its social construction. Frequently, the average life expectancy in a given region bears on what age counts as “old.” For example, in the United States, where the average life expectancy is over 78 years, people are not considered “old” until they are in their sixties or seventies. However, in Chad the average life expectancy is less than 49 years. People in their thirties or forties are therefore already middle-aged or “old.” These variations in people’s perceptions of who should or should not be considered elderly indicates that notions of youth and age are culturally constructed. There is thus no such thing as a universal age for being considered old.

Cultural Treatment of Aging

Cultures treat their elderly differently and place different values on old age. Many Eastern societies associate old age with wisdom, so they value old age much more than their Western counterparts. In Japan, adult children are expected to care for their aging parents in ways different than in the United States. Sixty five percent of Japanese elders live with their children and very few live in nursing homes. Japanese cultural norms suggest that caring for one’s parents by putting them in an assisted living home is tantamount to neglect. When unable to care for themselves, parents should ideally move in with their children. The Japanese celebration of old age is further illustrated by the existence of Respect for the Aged Day, which is a national holiday to celebrate elderly citizens.

Japanese perceptions of elders diverge markedly from public perceptions of old age in the United States. Western societies tend to place an increased value on youth such that many people take extreme measures to appear young. The desire to look younger than one’s biological years is frequently the impetus for cosmetic surgeries that can hide the physical effects of aging. These surgical practices, combined with the huge expenditures on makeup culture are seen in societies that value youthfulness.

Age Categories

Senescence, or biological aging, is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics. The word senescence, can be traced back to Latin senex, meaning “old.” Lots of other English words come from senex—senile, senior, senate, etc. The word senate to describe a legislative assembly dates back to ancient Rome, where the Senatus was originally a council of elders composed of the heads of patrician families. There’s also the much rarer senectitude, which, like senescence, refers to the state of being old (specifically, to the final stage of the normal life span).

The Young Old—65 to 74

These 18.3 million Americans tend to report greater health and social well-being than older adults. Having good or excellent health is reported by 41 percent of this age group (Center for Disease Control, 2004). Their lives are more similar to those of midlife adults than those who are 85 and older. This group is less likely to require long-term care, to be dependent or to be poor, and more likely to be married, working for pleasure rather than income, and living independently. About 65 percent of men and 50 percent of women between the ages of 65-69 continue to work full-time (He et al., 2005).

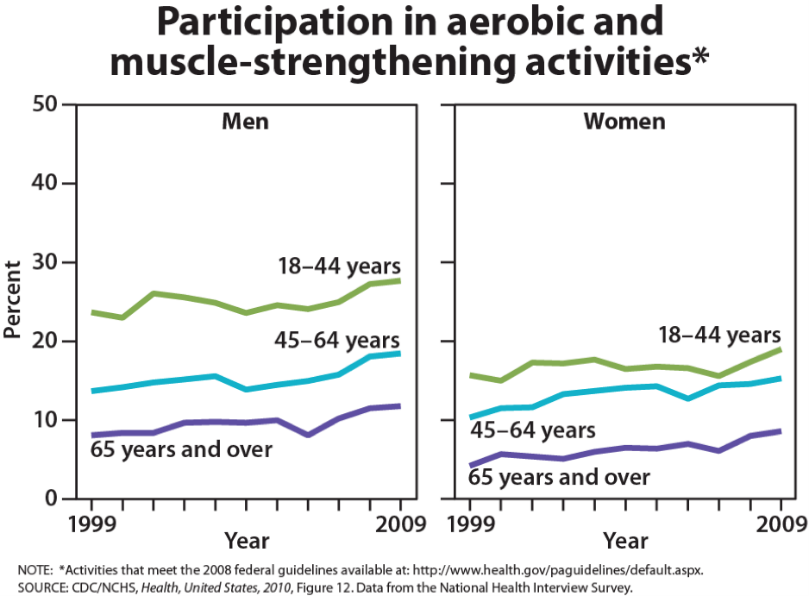

Physical activity tends to decrease with age, despite the dramatic health benefits enjoyed by those who exercise. People with more education and income are more likely to continue being physically active. And males are more likely to engage in physical activity than are females. The majority of the young-old continue to live independently. Only about 3 percent of those 65-74 need help with daily living skills as compared with about 22.9 percent of people over 85. (Another way to consider this is that 97 percent of people between 65-74 and 77 percent of people over 85 do not require assistance!) This age group is less likely to experience heart disease, cancer, or stroke than the old, but nearly as likely to experience depression (U.S. Census, 2005).

The Old Old—75 to 84

This age group is more likely to experience limitations on physical activity due to chronic disease such as arthritis, heart conditions, hypertension (especially for women), and hearing or visual impairments. Rates of death due to heart disease, cancer, and cerebral vascular disease are double that experienced by people 65-74. Poverty rates are 3 percent higher (12 percent) than for those between 65 and 74. However, the majority of these 12.9 million Americans live independently or with relatives. Widowhood is more common in this group-especially among women.

The Oldest Old—85 plus

The number of people 85 and older is 34 times greater than in 1900 and now includes 5.7 million Americans. This group is more likely to require long-term care and to be in nursing homes. However, of the 38.9 million American over 65, only 1.6 million require nursing home care. Sixty-eight percent live with relatives and 27 percent live alone (He et al., 2005; U. S. Census Bureau, 2011).

The Centenarians

Centenarians, or people aged 100 or older, are both rare and distinct from the rest of the older population. Although uncommon, the number of people living past age 100 is on the rise; between the year 2000 and 2014, then number of centenarians increased by over 43.6%, from 50,281 in 2000 to 72,197 in 2014. In 2010, over half (62.5 percent) of the 53,364 centenarians were age 100 or 101.

This number is expected to increase to 601,000 by the year 2050 (U. S. Census Bureau, 2011). The majority is between ages 100 and 104 and eighty percent are women. Out of almost 7 billion people on the planet, about 25 are over 110. Most live in Japan, a few live the in United States and three live in France (National Institutes of Health, 2006). These “super-Centenarians” have led varied lives and probably do not give us any single answers about living longer. Jeanne Clement smoked until she was 117. She lived to be 122. She also ate a diet rich in olive oil and rode a bicycle until she was 100. Her family had a history of longevity. Pitskhelauri (in Berger, 2005) suggests that moderate diet, continued work and activity, inclusion in family and community life, and exercise and relaxation are important ingredients for long life.

Blue Zones

Recent research on longevity reveals that people in some regions of the world live significantly longer than people elsewhere. Efforts to study the common factors between these areas and the people who live there is known as blue zone research. Blue zones are regions of the world where Dan Buettner claims people live much longer than average. The term first appeared in his November 2005 National Geographic magazine cover story, “The Secrets of a Long Life.” Buettner identified five regions as “Blue Zones”: Okinawa (Japan); Sardinia (Italy); Nicoya (Costa Rica); Icaria (Greece); and the Seventh-day Adventists in Loma Linda, California. He offers an explanation, based on data and first-hand observations, for why these populations live healthier and longer lives than others:

- Family – put ahead of other concerns

- Less smoking

- Semi-vegetarianism – the majority of food consumed is derived from plants

- Constant moderate physical activity – an inseparable part of life

- Social engagement – people of all ages are socially active and integrated into their communities

- Legumes – commonly consumed

The people inhabiting blue zones share common lifestyle characteristics that contribute to their longevity. The Venn diagram highlights the following six shared characteristics among the people of Okinawa, Sardinia, and Loma Linda blue zones. Though not a lifestyle choice, they also live as isolated populations with a related gene pool.

In his book, Buettner provides a list of nine lessons, covering the lifestyle of blue zones people:

- Moderate, regular physical activity.

- Life purpose.

- Stress reduction.

- Moderate caloric intake.

- Plant-based diet.

- Moderate alcohol intake, especially wine.

- Engagement in spirituality or religion.

- Engagement in family life.

- Engagement in social life.

The “Graying” of America

The term “graying of America” refers to the fact that the American population is steadily becoming more dominated by older people. In other words, the median age of Americans is going up. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 National Population Projections, the year 2030 marks an important demographic turning point in U.S. history. By 2030, all baby boomers will be older than age 65. This will expand the size of the older population so that 1 in every 5 residents will be retirement age. And by 2035, it’s projected that there will be 76.7 million people under the age of 18 but 78 million people above the age of 65. The 2030s are projected to be a transformative decade for the U.S. population. The population is expected to grow at a slower pace, age considerably and become more racially and ethnically diverse. Net international migration is projected to overtake natural increase in 2030 as the primary driver of population growth in the United States, another demographic first for the United States.

Although births are projected to be nearly four times larger than the level of net international migration in coming decades, a rising number of deaths will increasingly offset how much births are able to contribute to population growth. Between 2020 and 2050, the number of deaths is projected to rise substantially as the population ages and a significant share of the population, the baby boomers, age into older adulthood. As a result, the population will naturally grow very slowly, leaving net international migration to overtake natural increase as the leading cause of population growth, even as projected levels of migration remain relatively constant.

“Graying” Around the World

While the world’s oldest countries are mostly in Europe today, some Asian and Latin American countries are quickly catching up. The percentage of the population aged 65 and over in 2015 ranged from a high of 26.6 percent for Japan to a low of around 1 percent for Qatar and United Arab Emirates. Of the world’s 25 oldest countries, 22 are in Europe, with Germany and Italy leading the ranks of European countries for many years (He, Goodkind, and Kowal, 2015).

By 2050, Slovenia and Bulgaria are projected to be the oldest European countries. Japan, however, is currently the oldest nation in the world and is projected to retain this position through at least 2050. With the rapid aging taking place in Asia, the countries of South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are projected to join Japan at the top of the list of oldest countries and areas by 2050, when more than one-third of these Asian countries’ total populations are projected to be aged 65 and over.

Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of birth, current age and other demographic factors including gender. The most commonly used measure of life expectancy is at birth (LEB). There are great variations in life expectancy in different parts of the world, mostly due to differences in public health, medical care, and diet, but also affected by education, economic circumstances, violence, mental health, and sex.

Life Expectancy in the United States

According to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), life expectancy in the U.S. now stands at 78.7 years. Women continue to outlive men, with life expectancy being 76.3 years for males, and 81.1 years for females. Life expectancy varies according to race and ethnicity. It is highest for Hispanics, for both males and females, and lower for blacks than for whites or Hispanics.

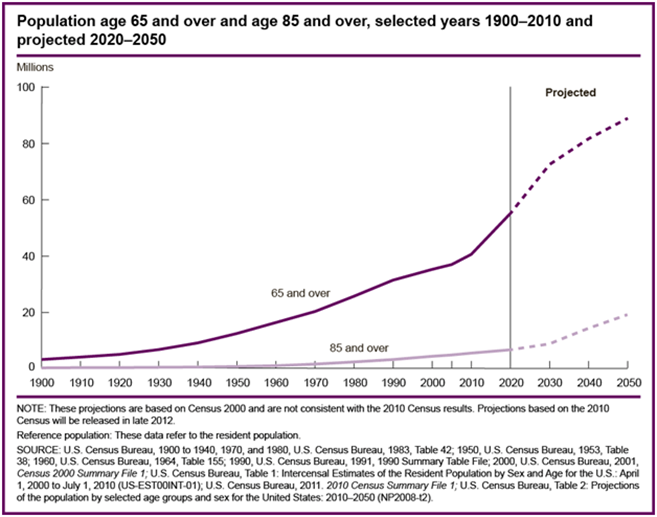

Statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau reveal that the 85-and over age group is the fastest-growing age group in America. According to the Census Bureau and AgingStats.gov, the over-65 population grew from 3 million in 1900 to 40 million in 2010, an increase of more than 1200%. But during this same time, the over-85 population grew from just over 100,000 in 1900 to 5.5 million in 2010– an increase of 5400%!

Some life factors are beyond a person’s control, and some are controllable. The rising cost of healthcare is a source of financial vulnerability to older adults. Vaccines are especially important for older adults. As you get older you’re more likely to get diseases like the flu, pneumonia, and shingles, and to have complications that can lead to long-term illness, hospitalization, and even death.

Things that contribute to longer life expectancies include eating a healthy diet that is rich in plants and nuts. Staying physically active, not smoking, and consuming moderate amounts of alcohol, tea, or coffee are also reported to be beneficial to leading a long life. Other recommendations include being conscientious, prioritizing your happiness, avoiding stress and anxiety, and having a strong social support network. Establishing a consistent sleep schedule and maintaining between 7-8 hours of sleep per night is also beneficial.

A major reason a person will statistically live longer once they reach an older age is simply that they have made it this far without anything killing them. Also, there appears to be several factors which may explain changes in life expectancy in the United States and around the world—health conditions are better, many diseases have been eliminated or better controlled through medicine, working conditions are better and better lifestyles choices are being made. Such factors significantly contribute to longer life expectancies.

CLICK THIS Sometimes referred to as mortality tables, death charts or actuarial life tables, these life expectancy tables are strictly statistical, and do not take into consideration any personal health information or lifestyle information. Take a look at life expectancy tables on the Life Expectancy Calculators website.

Understanding Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is also used in describing the physical quality of life. Quality of life is the general well-being of individuals and societies, outlining negative and positive features of life. Quality of life considers life satisfaction, including everything from physical health, family, education, employment, wealth, safety, security, freedom, religious beliefs, and the environment.

Increased life expectancy brings concern over the health and independence of those living longer. Greater attention is now being given to the number of years a person can expect to live without disability, which is called active life expectancy. When this distinction is made, we see that although women live longer than men, they are more at risk of living with disability (Weitz, 2007).

What factors contribute to poor health in women? Marriage has been linked to longevity, but spending years in a stressful marriage can increase the risk of illness. This negative effect is experienced more by women than men and seems to accumulate through the years. The impact of a stressful marriage on health may not occur until a woman reaches 70 or older (Umberson, Williams, et. al., 2006). Sexism can also create chronic stress. The stress experienced by women as they work outside the home as well as care for family members can also ultimately have a negative impact on health (He et. al., 2005).

The shorter life expectancy for men in general, is attributed to greater stress, poorer attention to health, more involvement in dangerous occupations, and higher rates of death due to accidents, homicide, and suicide. Social support can increase longevity. For men, life expectancy and health seem to improve with marriage. Spouses are less likely to engage in risky health practices and wives are more likely to monitor their husband’s diet and health regimes. But men who live in stressful marriages can also experience poorer health as a result.

Health and Sexuality

It has been suggested that an active sex life can increase longevity. Dr. Maggie Syme found in her research on sexuality in old age that, “Having a sexual partnership, with frequent sexual expression, having a good quality sex life, and being interested in sex have been found to be positively associated with health among middle-aged and older adults.” Positive sexual health in older age is gradually becoming more of a common topic and less taboo. Population percentage increase among older Americans has resulted in placing more attention on the needs of this age group, including their ideas on sexual health, desires, and attitudes. This shift in attitudes and behaviors, combined with medical advances to prolong a sexually active life, has changed the landscape of aging sexuality.

There are a number of associated health benefits with practicing positive sexual health. Positive sexual health often acts as a de-stressor promoting increased relaxation. Researchers also report health benefits such as decreased pain sensitivity, improved cardiovascular health, lower levels of depression, increased self-esteem, and better relationship satisfaction. This could also imply that there are negative consequences of poor sexual health or lack of sexual activity, including depression, low self-esteem, increased frustration, and loneliness.

Key players in improving the quality of life among older adults are the adults themselves. By exercising, reducing stress, not smoking, limiting use of alcohol, consuming more fruits and vegetables, and eating less meat and dairy, older adults can expect to live longer and more active lives (He et. al, 2005). Regular exercise is also associated with a lower risk of developing neurodegenerative disorders, especially Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Stress reduction both in late adulthood and earlier in life is also crucial. The reduction of societal stressors can promote active life expectancy. In the last 40 years, smoking rates have decreased, but obesity has increased, and physical activity has only modestly increased.

WATCH THIS clip below or online with captions from Marco Pahor, a professor in the University of Florida department of aging and geriatric research, as he discusses his research about ways physical activity affects the mobility of older adults and how it may result in longer life, lower medical costs, and increased long-term independence. You can view the transcript for “Study proves physical activity helps maintain mobility in older adults” here.

Health in Late Adulthood: Primary Aging

Normal Aging

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA, 2011) began in 1958 and has traced the aging process in 1,400 people from age 20 to 90. Researchers from the BLSA have found that the aging process varies significantly from individual to individual and from one organ system to another. Kidney function may deteriorate earlier in some individuals. Bone strength declines more rapidly in others. Much of this is determined by genetics, lifestyle, and disease. However, some generalizations about the aging process have been found:

- Heart muscles thicken with age

- Arteries become less flexible

- Lung capacity diminishes

- Brain cells lose some functioning but new neurons can also be produced

- Kidneys become less efficient in removing waste from the blood

- The bladder loses its ability to store urine

- Body fat stabilizes and then declines

- Muscle mass is lost without exercise

- Bone mineral is lost. Weight bearing exercise slows this down.

WATCH THIS video clip below or online from the National Institute of Health as it explains the research involved in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging. You’ll see some of the tests done on individuals, including measurements on energy expenditure, strength, proprioception, and brain imaging and scans.

Primary and Secondary Aging

Healthcare providers need to be aware of which aspects of aging are reversible and which ones are inevitable. By keeping this distinction in mind, caregivers may be more objective and accurate when diagnosing and treating older patients. And a positive attitude can go a long way toward motivating patients to stick with a health regime. Unfortunately, stereotypes can lead to misdiagnosis. For example, it is estimated that about 10 percent of older patients diagnosed with dementia are actually depressed or suffering from some other psychological illness (Berger, 2005). The failure to recognize and treat psychological problems in older patients may be one consequence of such stereotypes.

Primary Aging

Senescence, or biological aging, is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics. It is the process by which cells irreversibly stop dividing and enter a state of permanent growth arrest without undergoing cell death. This process is also referred to as primary aging and thus, refers to the inevitable changes associated with aging (Busse, 1969). These changes include changes in the skin and hair, height and weight, hearing loss, and eye disease. However, some of these changes can be reduced by limiting exposure to the sun, eating a nutritious diet, and exercising.

Skin and hair change with age. The skin becomes drier, thinner, and less elastic during the aging process. Scars and imperfections become more noticeable as fewer cells grow underneath the surface of the skin. Exposure to the sun, or photoaging, accelerates these changes. Graying hair is inevitable, and hair loss all over the body becomes more prevalent.

Height and weight vary with age. Older people are more than an inch shorter than they were during early adulthood (Masoro in Berger, 2005). This is thought to be due to a settling of the vertebrae and a lack of muscle strength in the back. Older people weigh less than they did in mid-life. Bones lose density and can become brittle. This is especially prevalent in women. However, weight training can help increase bone density after just a few weeks of training.

Muscle loss occurs in late adulthood and is most noticeable in men as they lose muscle mass. Maintaining strong leg and heart muscles is important for independence. Weight-lifting, walking, swimming, or engaging in other cardiovascular and weight bearing exercises can help strengthen the muscles and prevent atrophy.

Nutrition and Aging Research

The Jean Mayer Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (HNRCA) is one of six human nutrition research centers in the United States supported by the United States Department of Agriculture and Agricultural Research Service. The goal of the HNRCA, which is managed by Tufts University, is to explore the relationship between nutrition, physical activity, and healthy and active aging.

The HNRCA has made significant contributions to U.S. and international nutritional and physical activity recommendations, public policy, and clinical healthcare. These contributions include advancements in the knowledge of the role of dietary calcium and vitamin D in promoting nutrition and bone health, the role of nutrients in maintaining the optimal immune response, the prevention of infectious diseases, the role of diet in prevention of cancer, obesity research, modifications to the Food Guide Pyramid, contribution to USDA nutrient data bank, advancements in the study of sarcopenia, heart disease, vision, brain and cognitive function, front of packaging food labeling initiatives, and research of how genetic factors impact predisposition to weight gain and various health indicators. Research clusters within the HNRCA address four specific strategic areas: 1) cancer, 2) cardiovascular disease, 3) inflammation, immunity, and infectious disease and 4) obesity.

WATCH THIS: One concrete outcome of this research was a collaboration with the AARP producing a short video titled “MyPlate for Older Adults” showing how to follow the USDA’s My Plate nutrition guidelines as we age. Watch below or online with captions.

Vision

Some typical vision issues that arise along with aging include:

- Lens becomes less transparent and the pupils shrink.

- The optic nerve becomes less efficient.

- Distant objects become less acute.

- Loss of peripheral vision (the size of the visual field decreases by approximately one to three degrees per decade of life.)

- More light is needed to see and it takes longer to adjust to a change from light to darkness and vice versa.

- Driving at night becomes more challenging.

- Reading becomes more of a strain and eye strain occurs more easily.

The majority of people over 65 have some difficulty with vision, but most is easily corrected with prescriptive lenses. Three percent of those 65 to 74 and 8 percent of those 75 and older have hearing or vision limitations that hinder activity. The most common causes of vision loss or impairment are glaucoma, cataracts, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy (He et al., 2005).

Glaucoma occurs when pressure in the fluid of the eye increases, either because the fluid cannot drain properly or because too much fluid is produced. Glaucoma can be corrected with drugs or surgery. It must be detected early enough.

Cataracts are cloudy or opaque areas of the lens of the eye that interfere with passing light, frequently develop. Cataracts can be surgically removed or intraocular lens implants can replace old lenses.

Macular degeneration is the most common cause of blindness in people over the age of 60. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) affects the macula, a yellowish area of the eye located near the retina at which visual perception is most acute. A diet rich in antioxidant vitamins (C, E, and A) can reduce the risk of this disease.

Diabetic retinopathy, also known as diabetic eye disease, is a medical condition in which damage occurs to the retina due to diabetes mellitus. It is a leading cause of blindness. There are three major treatments for diabetic retinopathy, which are very effective in reducing vision loss from this disease: laser photocoagulation, medications, surgery.

Hearing

Hearing Loss, is experienced by 25% of people between ages 65 and 74, then by 50% of people above age 75. Among those who are in nursing homes, rates are even higher. Older adults are more likely to seek help with vision impairment than with hearing loss, perhaps due to the stereotype that older people who have difficulty hearing are also less mentally alert.

Conductive hearing loss may occur because of age, genetic predisposition, or environmental effects, including persistent exposure to extreme noise over the course of our lifetime, certain illnesses, or damage due to toxins. Conductive hearing loss involves structural damage to the ear such as failure in the vibration of the eardrum and/or movement of the ossicles (the three bones in our middle ear). Given the mechanical nature by which the sound wave stimulus is transmitted from the eardrum through the ossicles to the oval window of the cochlea, some degree of hearing loss is inevitable. These problems are often dealt with through devices like hearing aids that amplify incoming sound waves to make vibration of the eardrum and movement of the ossicles more likely to occur.

When the hearing problem is associated with a failure to transmit neural signals from the cochlea to the brain, it is called sensorineural hearing loss. This type of loss accelerates with age and can be caused by prolonged exposure to loud noises, which causes damage to the hair cells within the cochlea. Presbycusis is age-related sensorineural hearing loss resulting from degeneration of the cochlea or associated structures of the inner ear or auditory nerves. The hearing loss is most marked at higher frequencies. Presbycusis is the second most common illness next to arthritis in aged people.

One disease that results in sensorineural hearing loss is Ménière’s disease. Although not well understood, Ménière’s disease results in a degeneration of inner ear structures that can lead to hearing loss, tinnitus (constant ringing or buzzing), vertigo (a sense of spinning), and an increase in pressure within the inner ear (Semaan & Megerian, 2011). This kind of loss cannot be treated with hearing aids, but some individuals might be candidates for a cochlear implant as a treatment option. Cochlear implants are electronic devices consisting of a microphone, a speech processor, and an electrode array. The device receives incoming sound information and directly stimulates the auditory nerve to transmit information to the brain. Being unable to hear causes people to withdraw from conversation and others to ignore them or shout. Unfortunately, shouting is usually high pitched and can be harder to hear than lower tones. The speaker may also begin to use a patronizing form of ‘baby talk’ known as elderspeak (See et al., 1999). This language reflects the stereotypes of older adults as being dependent, demented, and childlike. Hearing loss is more prevalent in men than women. And it is experienced by more white, non-Hispanics than by Black men and women. Smoking, middle ear infections, and exposure to loud noises increase hearing loss.

Primary aging can be compensated for through exercise, corrective lenses, nutrition, and hearing aids. Just as important, by reducing stereotypes about aging, people of age can maintain self-respect, recognize their own strengths, and count on receiving the respect and social inclusion they deserve.

WATCH THIS video below or online discussing research done by T. Colin Campbell M.D., Michael Greger M.D., Neal Bernard M.D. and others demonstrating the impact of diet upon longevity and quality of life. As discussed in the video “Caloric Restriction vs. Animal Protein Restriction”, consumption of less animal-based protein has been linked with the slowing of degradation of function which was traditionally seen as part of the normal aging process. You can view the transcript for “Caloric Restriction vs. Animal Protein Restriction” here.

Secondary Aging

Secondary aging refers to changes that are caused by illness or disease. These illnesses reduce independence, impact quality of life, affect family members and other caregivers, and bring financial burden. The major difference between primary aging and secondary aging is that primary aging is irreversible and is due to genetic predisposition; secondary aging is potentially reversible and is a result of illness, health habits, and other individual differences. Secondary aging refers to the aspects of aging that are not universally shared by everyone, but are brought about by disease or chronic illness.

Chronic Illnesses

In the United States, nearly one in two Americans (133 million) has at least one chronic medical condition, with most subjects (58%) between the ages of 18 and 64. The number is projected to increase by more than one percent per year by 2030, resulting in an estimated chronically ill population of 171 million. The most common chronic conditions are high blood pressure, arthritis, respiratory diseases like emphysema, and high cholesterol.

According to research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, chronic disease is also especially a concern with older populations in America. Chronic diseases like stroke, heart disease, and cancer are among the leading causes of death among Americans aged 65 or older. While the majority of chronic conditions are found in individuals between the ages of 18 and 64, it is estimated that at least 80% of older Americans are currently living with some form of a chronic condition, with 50% of this population having two or more chronic conditions. The two most common chronic conditions are high blood pressure and arthritis, with diabetes, coronary heart disease, and cancer also being reported at high rates among older populations. The presence of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity, is termed “metabolic syndrome” and impacts 50% of individuals over the age of 60.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death from chronic disease for adults older than 65, followed by cancer, stroke, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases, influenza and pneumonia, and, finally, Alzheimer’s disease (which we’ll examine further when we talk about cognitive decline). Though the rates of chronic disease differ by race for those living with chronic illness, the statistics for leading causes of death among people over 65 are nearly identical across racial/ethnic groups.

Heart Disease

As stated above, heart disease is the leading cause of death from chronic disease for adults older than 65. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, heart failure, hypertensive heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, heart arrhythmia, congenital heart disease, valvular heart disease, carditis, aortic aneurysms, peripheral artery disease, thromboembolic disease, and venous thrombosis.

The underlying mechanisms vary depending on the disease. Coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral artery disease involve atherosclerosis. This may be caused by high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes mellitus, lack of exercise, obesity, high blood cholesterol, poor diet, and excessive alcohol consumption, among others. High blood pressure is estimated to account for approximately 13% of CVD deaths, while tobacco accounts for 9%, diabetes 6%, lack of exercise 6% and obesity 5%.

It is estimated that up to 90% of CVD may be preventable. Prevention of CVD involves improving risk factors through: healthy eating, exercise, avoidance of tobacco smoke and limiting alcohol intake. Treating risk factors, such as high blood pressure, blood lipids and diabetes is also beneficial. The use of aspirin in people, who are otherwise healthy, is of unclear benefit.

Cancer

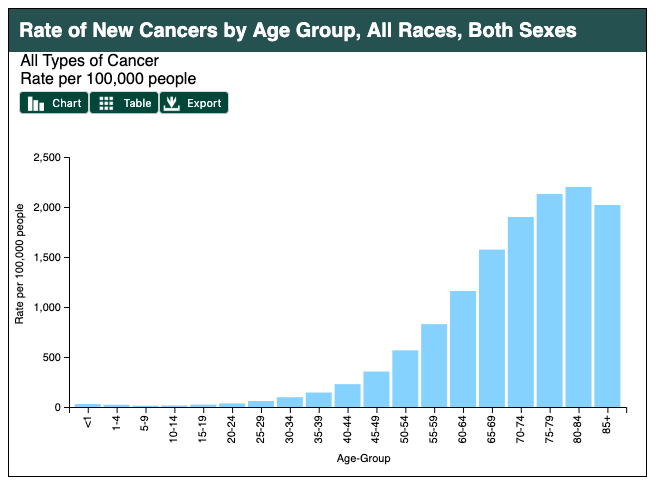

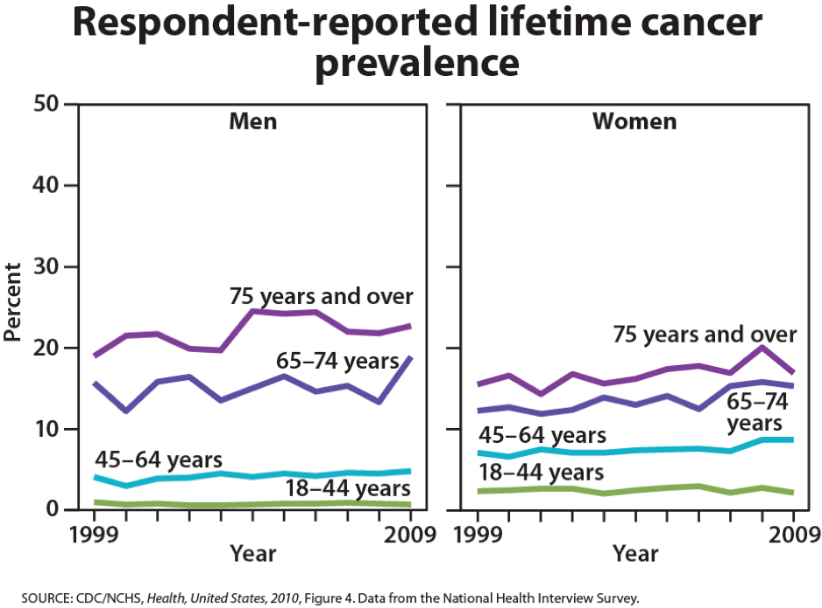

Age in itself is one of the most important risk factors for developing cancer. Currently, 60% of newly diagnosed malignant tumors and 70% of cancer deaths occur in people aged 65 years or older. Many cancers are linked to aging; these include breast, colorectal, prostate, pancreatic, lung, bladder and stomach cancers. Men over 75 have the highest rates of cancer at 28 percent. Women 65 and older have rates of 17 percent. Rates for older non-Hispanic Whites are twice as high as for Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks. The most common types of cancer found in men are prostate and lung cancer. Breast and lung cancer are the most common forms in women.

For many reasons, older adults with cancer have different needs than younger adults with the disease. For example, older adults:

- May be less able to tolerate certain cancer treatments.

- Have a decreased reserve (the capacity to respond to disease and treatment).

- May have other medical problems in addition to cancer.

- May have functional problems, such as the ability to do basic activities (dressing, bathing, eating) or more advanced activities (such as using transportation, going shopping or handling finances), and have less available family support to assist them as they go through treatment.

- May not always have access to transportation, social support or financial resources.

- May have different views of quality versus quantity of life.

Hypertension and Stroke

Hypertension or high blood pressure and associated heart disease and circulatory conditions increase with age. Stroke is a leading cause of death and severe, long-term disability. Most people who’ve had a first stroke also had high blood pressure (HBP or hypertension). High blood pressure damages arteries throughout the body, creating conditions where they can burst or clog more easily. Weakened arteries in the brain, resulting from high blood pressure, increase the risk for stroke—which is why managing high blood pressure is critical to reduce the chance of having a stroke. Hypertension disables 11.1 percent of 65 to 74-year olds and 17.1 percent of people over 75. Rates are higher among women and Black people. Rates are highest for women over 75. Coronary disease and stroke are higher among older men than women. The incidence of stroke is lower than that of coronary disease, but it is the No. 5 cause of death and a leading cause of disability in the United States.

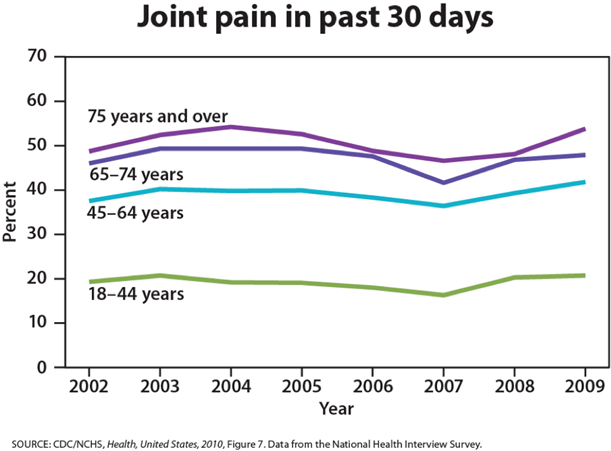

Arthritis

While arthritis can affect children, it is predominantly a disease of people over 65. Arthritis is more common in women than men at all ages and affects all races, ethnic groups and cultures. In the United States a CDC survey based on data from 2007–2009 showed 22.2% (49.9 million) of adults aged ≥18 years had self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis, and 9.4% (21.1 million or 42.4% of those with arthritis) had arthritis-attributable activity limitation (AAAL). With an aging population, this number is expected to increase.

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In some types of arthritis, other organs are also affected. Onset can be gradual or sudden.

There are over 100 types of arthritis. The most common forms are osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease) and rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoarthritis usually increases in frequency with age and affects the fingers, knees, and hips. Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder that often affects the hands and feet. Other types include gout, lupus, fibromyalgia, and septic arthritis. They are all types of rheumatic disease

Treatment may include resting the joint and alternating between applying ice and heat. Weight loss and exercise may also be useful. Pain medications such as ibuprofen and paracetamol (acetaminophen) may be used. In some a joint replacement may be useful.

OLDER AMERICANS & CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

READ THIS Visit this statistical fact sheet from the American Heart Association to learn more about some facts and figures related to heart disease.

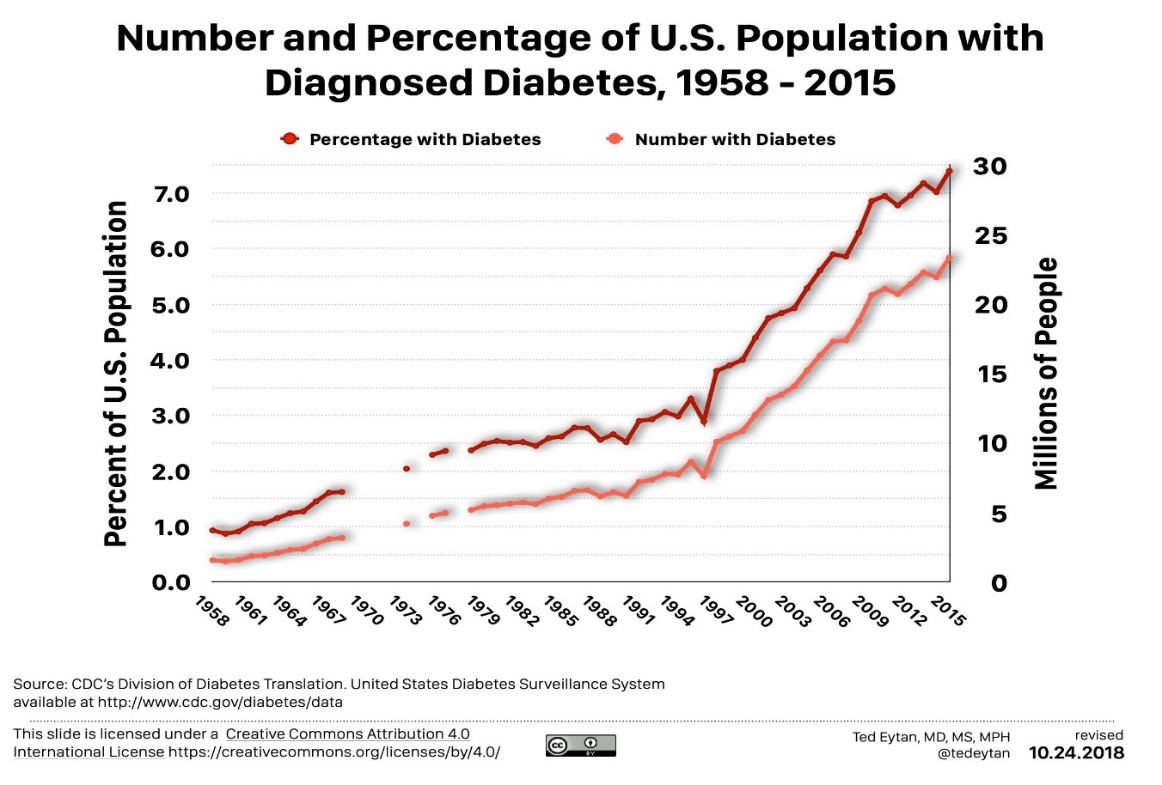

Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes (T2D), formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, is a form of diabetes characterized by high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and relative lack of insulin. Common symptoms include increased thirst, frequent urination, and unexplained weight loss. Symptoms may also include increased hunger, feeling tired, and sores that do not heal. Often symptoms come on slowly. Long-term complications from high blood sugar include heart disease, strokes, diabetic retinopathy which can result in blindness, kidney failure, and poor blood flow in the limbs which may lead to amputations.

Type 2 diabetes primarily occurs as a result of obesity and lack of exercise. Some people are more genetically at risk than others. Type 2 diabetes makes up about 90% of cases of diabetes, with the other 10% due primarily to type 1 diabetes and gestational diabetes. In type 1 diabetes there is a lower total level of insulin to control blood glucose, due to an autoimmune induced loss of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Diagnosis of diabetes is by blood tests such as fasting plasma glucose, oral glucose tolerance test, or glycated hemoglobin (A1C).

Type 2 diabetes is partly preventable by staying a normal weight, exercising regularly, and eating properly. Treatment involves exercise and dietary changes. If blood sugar levels are not adequately lowered, the medication metformin is typically recommended. Many people may eventually also require insulin injections. In those on insulin, routinely checking blood sugar levels is advised; however, this may not be needed in those taking pills. Bariatric surgery often improves diabetes in those who are obese.

Rates of type 2 diabetes have increased markedly since 1960 in parallel with obesity. As of 2015 there were approximately 392 million people diagnosed with the disease compared to around 30 million in 1985. Typically, it begins in middle or older age, although rates of type 2 diabetes are increasing in young people. Type 2 diabetes is associated with a ten-year-shorter life expectancy.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis comes from the Greek word for “porous bones” and is a disease in which bone weakening increases the risk of a broken bone. It is defined as having a bone density of 2.5 standard deviations below that of a healthy young adult. Osteoporosis increases with age as bones become brittle and lose minerals. It is the most common reason for a broken bone among older women.

Osteoporosis becomes more common with age. About 15% of white people in their 50s and 70% of those over 80 are affected. It is four times more likely to affect women than men—in the developed world, depending on the method of diagnosis, 2% to 8% of males and 9% to 38% of females are affected. In the United States in 2010, about eight million women and one to two million men had osteoporosis. White and Asian people are at greater risk are more likely to have osteoporosis than non-Hispanic blacks.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system which mainly affects the motor system, although as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms become increasingly common. Early in the disease, the most obvious symptoms are shaking, rigidity, slowness of movement, and difficulty with walking, but thinking and behavioral problems may also occur. Dementia becomes common in the advanced stages of the disease, and depression and anxiety also occur in more than a third of people with PD.

The cause of Parkinson’s disease is generally unknown, but believed to involve both genetic and environmental factors. Those with a family member affected are more likely to get the disease themselves. There is also an increased risk in people exposed to certain pesticides and among those who have had prior head injuries, while there is a reduced risk in tobacco smokers (though smokers are at a substantially greater risk of stroke) and those who drink coffee or tea. The motor symptoms of the disease result from the death of cells in the substantia nigra, a region of the midbrain, which results in not enough dopamine in these areas. The reason for this cell death is poorly understood, but involves the build-up of proteins into Lewy bodies in the neurons.

In 2015, PD affected 6.2 million people and resulted in about 117,400 deaths globally. Parkinson’s disease typically occurs in people over the age of 60, of which about one percent are affected. Males are more often affected than females at a ratio of around 3:2. The average life expectancy following diagnosis is between 7 and 14 years. People with Parkinson’s who have increased the public’s awareness of the condition include actor Michael J. Fox, Olympic cyclist Davis Phinney, and professional boxer Muhammad Ali.

Cognitive Development and Memory in Late Adulthood

How Does Aging Affect Memory?

The Sensory Register

Aging may create small decrements in the sensitivity of the senses. And, to the extent that a person has a more difficult time hearing or seeing, that information will not be stored in memory. This is an important point, because many older people assume that if they cannot remember something, it is because their memory is poor. In fact, it may be that the information was never seen or heard.

The Working Memory

Older people have more difficulty using memory strategies to recall details (Berk, 2007). Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity responsible for temporarily holding information available for processing. As we age, the working memory loses some of its capacity. This makes it more difficult to concentrate on more than one thing at a time or to remember details of an event. However, people often compensate for this by writing down information and avoiding situations where there is too much going on at once to focus on a particular cognitive task.

When an older person demonstrates difficulty with multi-step verbal information presented quickly, the person is exhibiting problems with working memory. Working memory is among the cognitive functions most sensitive to decline in old age. Several explanations have been offered for this decline in memory functioning; one is the processing speed theory of cognitive aging by Tim Salthouse. Drawing on the findings of general slowing of cognitive processes as people grow older, Salthouse argues that slower processing causes working-memory contents to decay, thus reducing effective capacity. For example, if an older person is watching a complicated action movie, they may not process the events quickly enough before the scene changes, or they may processing the events of the second scene, which causes them to forget the first scene. The decline of working-memory capacity cannot be entirely attributed to cognitive slowing, however, because capacity declines more in old age than speed.

Another proposal is the inhibition hypothesis advanced by Lynn Hasher and Rose Zacks. This theory assumes a general deficit in old age in the ability to inhibit irrelevant, or no-longer relevant, information. Therefore, working memory tends to be cluttered with irrelevant contents which reduce the effective capacity for relevant content. The assumption of an inhibition deficit in old age has received much empirical support but, so far, it is not clear whether the decline in inhibitory ability fully explains the decline of working-memory capacity.

An explanation on the neural level of the decline of working memory and other cognitive functions in old age was been proposed by Robert West. He argued that working memory depends to a large degree on the pre-frontal cortex, which deteriorates more than other brain regions as we grow old. Age related decline in working memory can be briefly reversed using low intensity transcranial stimulation, synchronizing rhythms in bilateral frontal and left temporal lobe areas.

The Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory involves the storage of information for long periods of time. Retrieving such information depends on how well it was learned in the first place rather than how long it has been stored. If information is stored effectively, an older person may remember facts, events, names and other types of information stored in long-term memory throughout life. The memory of adults of all ages seems to be similar when they are asked to recall names of teachers or classmates. And older adults remember more about their early adulthood and adolescence than about middle adulthood (Berk, 2007). Older adults retain semantic memory or the ability to remember vocabulary.

Younger adults rely more on mental rehearsal strategies to store and retrieve information. Older adults’ focus relies more on external cues such as familiarity and context to recall information (Berk, 2007). And they are more likely to report the main idea of a story rather than all of the details (Jepson & Labouvie-Vief, in Berk, 2007).

A positive attitude about being able to learn and remember plays an important role in memory. When people are under stress (perhaps feeling stressed about memory loss), they have a more difficult time taking in information because they are preoccupied with anxieties. Many of the laboratory memory tests require comparing the performance of older and younger adults on timed memory tests in which older adults do not perform as well. However, few real-life situations require speedy responses to memory tasks. Older adults rely on more meaningful cues to remember facts and events without any impairment to everyday living.

New Research on Aging and Cognition

Can the brain be trained in order to build cognitive reserve to reduce the effects of normal aging? ACTIVE (Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly), a study conducted between 1999 and 2001 in which 2,802 individuals age 65 to 94, suggests that the answer is “yes.” These participants received 10 group training sessions and 4 follow up sessions to work on tasks of memory, reasoning, and speed of processing. These mental workouts improved cognitive functioning even 5 years later. Many of the participants believed that this improvement could be seen in everyday tasks as well (Tennstedt, Morris, et al, 2006). Learning new things, engaging in activities that are considered challenging, and being physically active at any age may build a reserve to minimize the effects of primary aging of the brain.

WATCH THIS clip below or online from SciShow Psych to learn about ways to keep the mind young and active. You can view the transcript for “The Best Ways to Keep Your Mind Young” here.

Wisdom

Wisdom is the ability to use common sense and good judgment in making decisions. A wise person is insightful and has knowledge that can be used to overcome obstacles they encounter in their daily lives. Does aging bring wisdom? While living longer brings experience, it does not always bring wisdom. Those who have had experience helping others resolve problems in living and those who have served in leadership positions seem to have more wisdom. So, it is age combined with a certain type of experience that brings wisdom. However, older adults generally have greater emotional wisdom or the ability to empathize with and understand others.

Changes in Attention in Late Adulthood

Divided attention has usually been associated with significant age-related declines in performing complex tasks. For example, older adults show significant impairments on attentional tasks such as looking at a visual cue at the same time as listening to an auditory cue because it requires dividing or switching of attention among multiple inputs. Deficits found in many tasks, such as the Stroop task which measures selective attention, can be largely attributed to a general slowing of information processing in older adults rather than to selective attention deficits per se. They also are able to maintain concentration for an extended period of time. In general, older adults are not impaired on tasks that test sustained attention, such as watching a screen for an infrequent beep or symbol.

The tasks on which older adults show impairments tend to be those that require flexible control of attention, a cognitive function associated with the frontal lobes. Importantly, these types of tasks appear to improve with training and can be strengthened.

An important conclusion from research on changes in cognitive function as we age is that attentional deficits can have a significant impact on an older person’s ability to function adequately and independently in everyday life. One important aspect of daily functioning impacted by attentional problems is driving. This is an activity that, for many older people, is essential to independence. Driving requires a constant switching of attention in response to environmental contingencies. Attention must be divided between driving, monitoring the environment, and sorting out relevant from irrelevant stimuli in a cluttered visual array. Research has shown that divided attention impairments are significantly associated with increased automobile accidents in older adults. Therefore, practice and extended training on driving simulators under divided attention conditions may be an important remedial activity for older people.

Problem Solving

Problem solving tasks that require processing non-meaningful information quickly (a kind of task which might be part of a laboratory experiment on mental processes) declines with age. However, real life challenges facing older adults do not rely on speed of processing or making choices on one’s own. Older adults are able to resolve everyday problems by relying on input from others such as family and friends. They are also less likely than younger adults to delay making decisions on important matters such as medical care (Strough et al., 2003; Meegan & Berg, 2002).

Cognitive Function in Late Adulthood

Abnormal Loss of Cognitive Functioning During Late Adulthood

Dementia is the umbrella category used to describe the general long-term and often gradual decrease in the ability to think and remember that affects a person’s daily functioning. The manual used to help classify and diagnose mental disorders, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-V, classifies dementia as a “major neurocognitive disorder,” with milder symptoms classified as “mild cognitive impairment,” although the term dementia is still in common use. Common symptoms of dementia include emotional problems, difficulties with language, and a decrease in motivation. A person’s consciousness is usually not affected. Globally, dementia affected about 46 million people in 2015. About 10% of people develop the disorder at some point in their lives, and it becomes more common with age. About 3% of people between the ages of 65–74 have dementia, 19% between 75 and 84, and nearly half of those over 85 years of age. In 2015, dementia resulted in about 1.9 million deaths, up from 0.8 million in 1990. As more people are living longer, dementia is becoming more common in the population as a whole.

Dementia generally refers to severely impaired judgment, memory, or problem-solving ability. It can occur before old age and is not an inevitable development even among the very old. Dementia can be caused by numerous diseases and circumstances, all of which result in similar general symptoms of impaired judgment, etc. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and is incurable, but there are also nonorganic causes of dementia which can be prevented. Malnutrition, alcoholism, depression, and mixing medications can also result in symptoms of dementia. If these causes are properly identified, they can be treated. Cerebral vascular disease can also reduce cognitive functioning.

Delirium, also known as acute confusional state, is an organically caused decline from a previous baseline level of mental function that develops over a short period of time, typically hours to days. It is more common in older adults, but can easily be confused with a number of psychiatric disorders or chronic organic brain syndromes because of many overlapping signs and symptoms in common with dementia, depression, psychosis, etc. Delirium may manifest from a baseline of existing mental illness, a baseline intellectual development disorder, or dementia, without being due to any of these problems.

Delirium is a syndrome encompassing disturbances in attention, consciousness, and cognition. It may also involve other neurological deficits, such as psychomotor disturbances (e.g. hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed), impaired sleep-wake cycle, emotional disturbances, and perceptual disturbances (e.g. hallucinations and delusions), although these features are not required for diagnosis. Among older adults, delirium occurs in 15-53% of post-surgical patients, 70-87% of those in the ICU, and up to 60% of those in nursing homes or post-acute care settings. Among those requiring critical care, delirium is a risk for death within the next year.

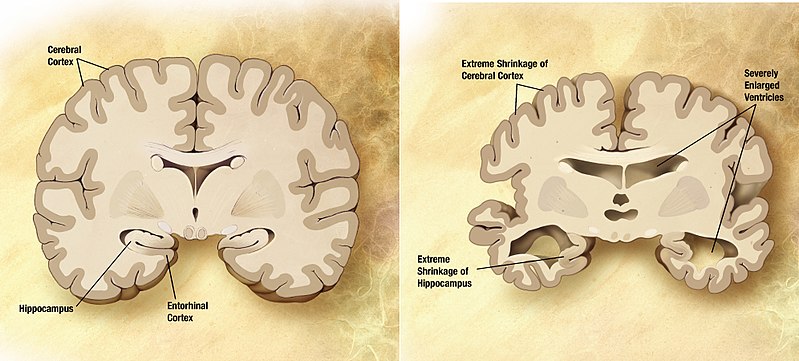

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), also referred to simply as Alzheimer’s, is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for 60-70% of its cases. Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease; causing problems with memory, thinking, and behavior. Symptoms usually develop slowly and get worse over time, becoming severe enough to interfere with daily tasks.

The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems with language, disorientation (including easily getting lost), mood swings, loss of motivation, not managing self-care, and behavioral issues. In the early stages, memory loss is mild, but with late-stage Alzheimer’s, individuals lose the ability to carry on a conversation and respond to their environment.

Alzheimer’s is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States. On average, a person with Alzheimer’s lives four to eight years after diagnosis but can live as long as 20 years, depending on other factors. Alzheimer’s is not a normal part of aging. The greatest known risk factor is increasing age, and the majority of people with Alzheimer’s are 65 and older. But Alzheimer’s is not just a disease of old age. Approximately 200,000 Americans under the age of 65 have younger-onset Alzheimer’s disease (also known as early-onset Alzheimer’s).

The cause of Alzheimer’s disease is poorly understood. About 70% of the risk is believed to be inherited from a person’s parents with many genes usually involved. Other risk factors include a history of head injuries, depression, and hypertension. The disease process is associated with plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. A probable diagnosis is based on the history of the illness and cognitive testing with medical imaging and blood tests to rule out other possible causes. Initial symptoms are often mistaken for normal aging, but examination of brain tissue, specifically of structures called plaques and tangles, is needed for a definite diagnosis. Though qualified physicians can be up to 90% certain of a correct diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, currently, the only way to make a 100% definitive diagnosis is by performing an autopsy of the person and examining the brain tissue. In 2015, there were approximately 29.8 million people worldwide with AD. In developed countries, AD is one of the most financially costly diseases.

WATCH THIS Ted-Ed video below or online explaining some of the history and biological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. You can view the transcript for “What is Alzheimer’s disease? – Ivan Seah Yu Jun” here.

LISTEN TO THIS: Samuel Cohen researches Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Listen to Cohen’s TED Talk on Alzheimer’s disease to learn more.

Psychosocial Development in Late Adulthood

Our ideas about aging, and what it means to be over 50, over 60, or even over 90, seem to be stuck somewhere back in the middle of the 20th century. We still consider 65 as standard retirement age, and we expect everyone to start slowing down and moving aside for the next generation as their age passes the half-century mark. In this section we explore psychosocial developmental theories, including Erik Erikson’s theory on psychosocial development in late adulthood, and we look at aging as it relates to work, retirement, and leisure activities for older adult. We’ll also examine ways in which people are productive in late adulthood.

Attitudes about Aging

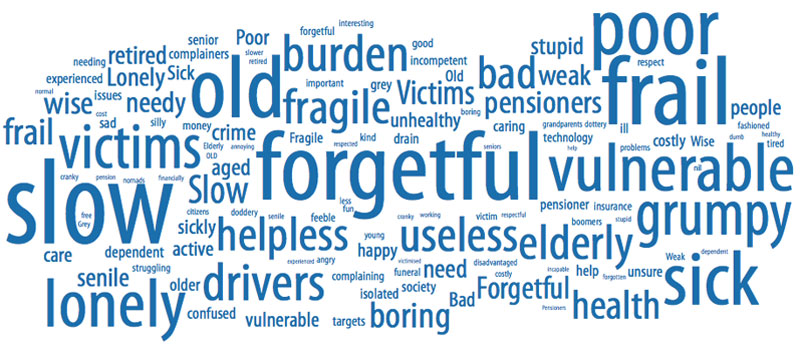

Stereotypes about people of in late adulthood lead many to assume that aging automatically brings poor health and mental decline. These stereotypes are reflected in everyday conversations, the media and even in greeting cards (Overstreet, 2006). The following examples serve to illustrate.

1) Grandpa, fishing pole in one hand, pipe in the other, sits on the ground and completes a story being told to his grandson with “. . . and that, Jimmy, is the tale of my very first colonoscopy.” The message inside the card reads, “Welcome to the gross personal story years.” (Shoebox, A Division of Hallmark Cards.)

2) An older woman in a barber shop cuts the hair of an older, dozing man. “So, what do you say today, Earl?” she asks. The inside message reads, “Welcome to the age where pretty much anyplace is a good place for a nap.” (Shoebox, A Division of Hallmark Cards.)

3) A crotchety old man with wire glasses, a crumpled hat, and a bow tie grimaces and the card reads, “Another year older? You’re at the age where you should start eatin’ right, exercisin’, and takin’ vitamins . . .” The inside reads, “Of course you’re also at the age where you can ignore advice by actin like you can’t hear it.” (Hallmark Cards, Inc.)

Of course, these cards are made because they are popular. Age is not revered in the United States, and so laughing about getting older is one way to get relief. The attitudes above are examples of ageism, prejudice based on age. Ageism is prejudice and discrimination that is directed at older people. This view suggests that older people are less in command of their mental faculties. Older people are viewed more negatively than younger people on a variety of traits, particularly those relating to general competence and attractiveness. Stereotypes such as these can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy in which beliefs about one’s ability results in actions that make it come true.

Ageism is a modern and predominately western cultural phenomenon—in the American colonial period, long life was an indication of virtue, and Asian and Native American societies view older people as wise, storehouses of information about the past, and deserving of respect. Many preindustrial societies observed gerontocracy, a type of social structure wherein the power is held by a society’s oldest members. In some countries today, older adults still have influence and power and their vast knowledge is respected, but this reverence has decreased in many places due to social factors. A positive, optimistic outlook about aging and the impact one can have on improving health is essential to health and longevity. Removing societal stereotypes about aging and helping older adults reject those notions of aging is another way to promote health in older populations.

In addition to ageism, racism is yet another concern for marginalized populations as they age. The number of Black Americans above the age of 65 is projected to grow from around 4 million now to 12 million by 2060. Racism towards Black people and other marginalized groups throughout their lifetime results in many older marginalized people having fewer resources, more chronic health conditions, and significant health disparities when compared to older white Americans. Racism towards older adults from diverse backgrounds has resulted in them having limited access to community resources such as grocery stores, housing, health care providers, and transportation.

WATCH THIS clip below or online from the Big Think that examines some of the negative prejudices towards older adults. You can view the transcript for “Ageism in the USA: The paradox of prejudice against the elderly” here. You can watch another video from Ashton Applewhite in this TED talk “Let’s End Ageism.”

Elderly Abuse

Nursing homes have been publicized as places where older adults are at risk of abuse. Abuse and neglect of nursing home residents is more often found in facilities that are run down and understaffed. However, older adults are more frequently abused by family members. The most commonly reported types of abuse are financial abuse and neglect. Victims are usually very frail and impaired and perpetrators are usually dependent on the victims for support. Prosecuting a family member who has financially abused a parent is very difficult. The victim may be reluctant to press charges and the court dockets are often very full resulting in long waits before a case is heard. “Granny dumping” or the practice of family members abandoning older family members with severe disabilities in emergency rooms is a growing problem; an estimated 100,000 and 200,000 are dumped each year (Tanne in Berk, 2007).

CLICK OR CALL THESE: If you or someone you know suspects or affected by elder abuse, help is available! A good place to start is the National Center on Elder Abuse. You can also reach out to the Adult Protection Services in your state- find those resources at the National Adult Protective Services Association website. The Eldercare Locator, a helpline and website containing a wide range of resources for seniors presented by the US government’s Administration for Community Living, can also help. They have options online and through a helpline at 1-800-677-1116.

Erikson: Integrity vs. Despair

As a person grows older and enters into the retirement years, the pace of life and productivity tend to slow down, granting a person time for reflection upon their life. They may ask the existential question, “It is okay to have been me?” If someone sees themselves as having lived a successful life, they may see it as one filled with productivity, or according to Erik Erikson, integrity.

Here integrity is said to consist of the ability to look back on one’s life with a feeling of satisfaction, peace and gratitude for all that has been given and received.

Thus, persons derive a sense of meaning (i.e., integrity) through careful review of how their lives have been lived (Krause, 2012). Ideally, however, integrity does not stop here, but rather continues to evolve into the virtue of wisdom. According to Erikson, this is the goal during this stage of life.

If a person sees their life as unproductive, or feel that they did not accomplish their life goals, they may become dissatisfied with life and develop what Erikson calls despair, often leading to depression and hopelessness. This stage can occur out of the sequence when an individual feels they are near the end of their life (such as when receiving a terminal disease diagnosis).

Erikson’s Ninth Stage

Erikson collaborated with his wife, Joan, through much of his work on psychosocial development. In the Erikson’s older years, they re-examined the eight stages and created additional thoughts about how development evolves during a person’s 80s and 90s. After Erik Erikson passed away in 1994, Joan published a chapter on the ninth stage of development, in which she proposed (from her own experiences and Erik’s notes) that older adults revisit the previous eight stages and deal with the previous conflicts in new ways, as they cope with the physical and social changes of growing old. In the first eight stages, all of the conflicts are presented in a syntonic-dystonic matter, meaning that the first term listed in the conflict is the positive, sought-after achievement and the second term is the less-desirable goal (ie. trust is more desirable than mistrust and integrity is more desirable than despair). During the ninth stage, Erikson argues that the dystonic, or less desirable outcome, comes to take precedence again. For example, an older adult may become mistrustful (trust vs. mistrust), feel more guilt about not having the abilities to do what they once did (initiative vs. guilt), feel less competent compared with others (industry vs. inferiority) lose a sense of identity as they become dependent on others (identity vs. role confusion), become increasingly isolated (intimacy vs. isolation), and feel that they have less to offer society (generativity vs. stagnation). Or, the Eriksons found that those who successfully come to terms with these changes and adjustments in later life make headway towards gerotrancendence, a term coined by gerontologist Lars Tornstam to represent a greater awareness of one’s own life and connection to the universe, increased ties to the past, and a positive, transcendent, perspective about life.

Activity Theory