13 Module 13: Identities and Environments

Module 13 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Define Social Identities

Explain the concept of social identities and how they are shaped by personal, historical, and sociopolitical factors. - Analyze the Role of Social Identities in Healthcare

Discuss how social identities affect perceptions, power dynamics, and interactions in healthcare settings. - Understand Health Disparities

Identify the causes of health disparities and their impact on different social identity groups. - Explore the Concept of Health Equity

Explain the principles of health equity and strategies to reduce health disparities in healthcare. - Examine Implicit Bias

Define implicit bias and describe its characteristics, effects, and methods for reducing bias in healthcare and other contexts. - Reflect on Personal Biases

Reflect on how personal biases and perceptions of social identities influence behavior and decision-making in professional settings. - Understand Social Determinants of Health

Identify the five main social determinants of health and explain how they influence individual and population health outcomes. - Discuss Cultural Competence

Describe the importance of cultural competence in healthcare and its role in improving patient outcomes. - Examine Intersectionality

Explain the concept of intersectionality and its relevance to understanding overlapping social identities and systemic oppressions. - Evaluate the Impact of Health-Related Stigma

Analyze how health-related stigma intersects with social marginalization to affect health outcomes. - Explore Environmental Factors on Health

Discuss how environmental factors, such as pollution and climate change, influence individual and community health. - Understand Cultural Influences on Health

Explain how cultural values, beliefs, and practices shape health behaviors and perceptions of illness. - Analyze the Role of Education in Health

Discuss the connection between educational attainment and health outcomes, including health literacy. - Apply Transcultural Nursing Principles

Describe how transcultural nursing principles improve culturally sensitive care and reduce health disparities. - Evaluate Professional Identity

Explain how professional identity develops and its importance for healthcare providers in delivering effective care. - Discuss the Psychology of Scarcity

Explore how scarcity impacts decision-making, behaviors, and long-term health outcomes.

Introduction

Understanding identities, both how we see ourselves and the social placement of identities others use, is crucial in a human development or psychology course. These aspects shape individuals’ experiences, opportunities, and interactions within various social contexts, influencing their development across the lifespan, their thoughts, feelings and behaviors. Understanding how the environment shapes individuals’ physical, cognitive, and social development provides a framework within which these processes occur. By understanding the intricate ways in which environmental factors and cultural norms influence human development and thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, we gain a holistic view of the diverse factors that contribute to growth and change. Cultural context helps in appreciating the variety of developmental pathways and the role of cultural values, practices, and beliefs in shaping individual and collective identities. By studying these concepts, we develop a deeper empathy and awareness of the human experience.

For individuals pursuing careers in healthcare, this knowledge is particularly vital. Healthcare professionals must understand how intersecting identities and cultural contexts influence health behaviors, perceptions of illness, interactions in a healthcare system, and ultimately health outcomes in order to provide culturally competent and empathetic treatment. Awareness of biases and stigma can help prevent discriminatory practices, reducing health disparities and ensuring everyone receive respectful and effective care regardless of their background.

Social Identity

The term social identity originated in the 1970s and is attributed to two social psychologists, Henri Tajfel and John Turner. These scholars were interested in developing language and theories to help better explain the way people’s identities, and their relations to each other, are affected by their belonging, or perceived belonging, in different social groups.

Social identities are often defined as one’s group memberships shaped by individual characteristics, historical factors, and social and political contexts. While we all belong to many different groups, from sports teams to families, social identity groups refer to those that are part of large power structures in society. Because they are defined by societal structures, these group memberships shape the way we experience and interact with our social world.

Implications in healthcare professions

Social identities inform our perceptions of ourselves, but they also inform our interactions with others. It is important to be aware of these identities when working within a community or with groups of people, as it can influence the way we interact with others in social contexts. The way a community perceives your social identities can impact your engagement experience. Conversely, the way that you perceive the community will also influence your relationships, the outcome of your work, and everyone’s satisfaction with the experience. Social identities can also create power dynamics, especially when working with rights holders and/or minoritized groups. This is why it is so important that you do work and reflection ahead of time to better understand how these factors might impact your work, making you better prepared to handle any situations that arise due to social identities. An important question to ask when you conduct your research is, “What is the community’s historical experience with people who have my social identities?” Then ask yourself, “How do I perceive the social identities of the people in the community?” And finally, “How would they perceive my social identities? Would these perceptions change as a result of engagement and interaction?”

TRY THIS Take a few moments to think about your own identities. Which social groups do you belong to? Consider the Circle of Power presented on page 2 of this workbook. Use the wheel diagram to explore areas where you have experienced advantage or disadvantage in your life. Looking at the Social Identify Wheel may be helpful as you complete the exercise.

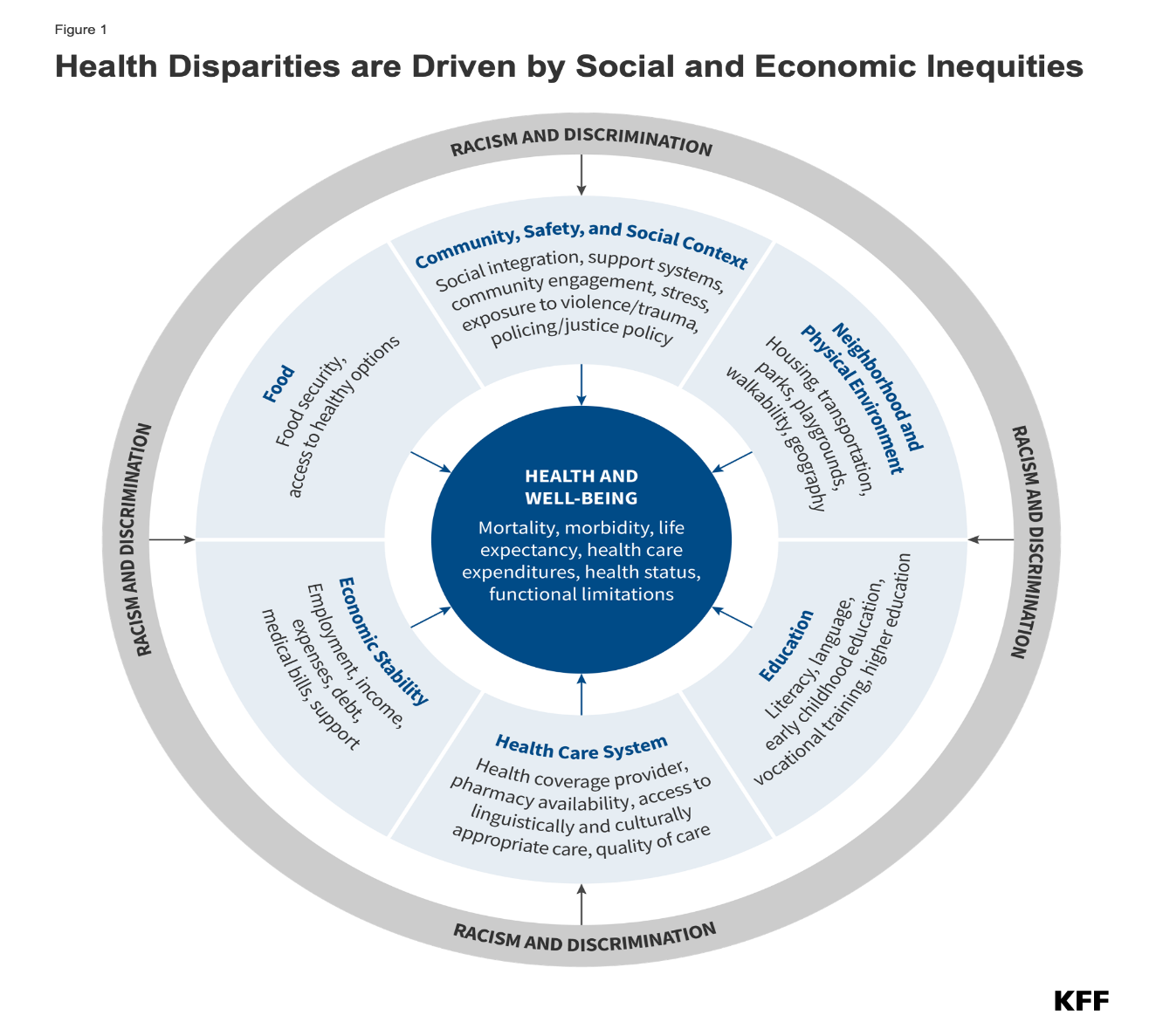

Health Disparities and Health Equity

Healthy People 2030 defines a health disparity as “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.” Health disparities are inequitable and are directly related to the historical and current unequal distribution of social, political, economic, and environmental resources.

Some of the differences in health outcomes could be:

Higher incidence and/or prevalence and earlier onset of disease

Higher prevalence of risk factors, unhealthy behaviors, or clinical measures in the causal pathway of a disease outcome

Higher rates of condition-specific symptoms, reduced global daily functioning, or self-reported health-related quality of life using standardized measures

Premature and/or excessive mortality from diseases where population rates differ

Greater global burden of disease using a standardized metric

Health disparities result from multiple factors, including

- Poverty

- Environmental threats

- Inadequate access to health care

- Individual and behavioral factors

- Educational inequalities (see below)

Health disparities are related to inequities in education. Dropping out of school is associated with multiple social and health problems. Overall, individuals with less education are more likely to experience a number of health risks, such as obesity, substance abuse, and intentional and unintentional injury, compared with individuals with more education. Higher levels of education are associated with a longer life and an increased likelihood of obtaining or understanding basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions. At the same time, good health is associated with academic success. Higher levels of protective health behaviors and lower levels of health risk behaviors are been associated with higher academic grades among high school students. Health risks such as teenage pregnancy, poor dietary choices, inadequate physical activity, physical and emotional abuse, substance abuse, and gang involvement have a significant impact on how well students perform in school.

CLICK THIS: Healthy People 2030 is a US government initiative to “eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all.” Check out the website for more information, resources, and data.

Gender and Health

Gender is a range of characteristics used to distinguish between males and females, particularly in the cases of men and women and the masculine and feminine attributes assigned to them. Depending on the context, the discriminating characteristics vary, from sex to social role to gender identity. The World Health Organization defines gender as the result of socially constructed ideas about the behavior, actions, and roles a particular sex performs. Assigning gender involves taking into account the physiological and biological attributes assigned by nature followed by socially constructed conduct. The social label of being classified into one or the other sex is obligatory to the medical stamp on the birth certificate.

There are a number of ways in which health disparities play out based on different systems of stratification. Researchers also find health disparities based on gender stratification. One study found that women are less likely than men to be recommended for knee replacement surgery, even when they have the same symptoms. While it was unclear what role the sex of the recommending physicians played, the authors of this study encouraged women to challenge their doctors in order to get care equivalent to men.

Gender, and particularly the role of women, is widely recognized as vitally important to international development issues. This often means a focus on gender-equality, ensuring participation, but includes an understanding of the different roles and expectations of the genders within the community. As recognized by the United Nations, women’s dual responsibilities as carers and income earners leaves them suffering from time poverty, and thus unable to access health and education services. The Gender-related Development Index (GDI), developed by the United Nations, aims to show the inequalities between men and women in the following areas: long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living.

VIEW THIS Infographic from the National Institutes of Health on How Sex and Gender influence health and disease.

Race and Health

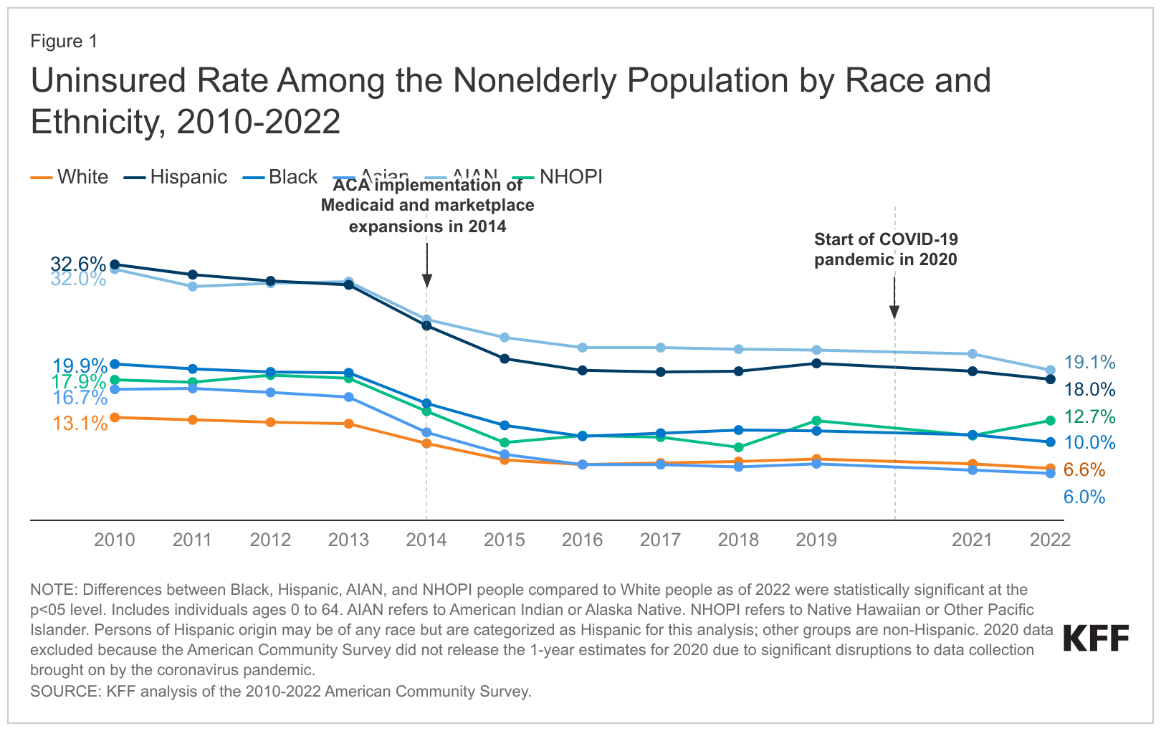

Race and health research, often done in the United States, has found both current and historical racial differences in the frequency, treatments, and availability of treatments for several diseases. This can add up to significant group differences in variables such as life expectancy. Many explanations for such differences have been argued, including socioeconomic factors, lifestyle, social environment, and access to preventive health-care services, among other environmental differences.

In multiracial societies such as the United States, racial groups differ greatly in regard to social and cultural factors such as socioeconomic status, healthcare, diet, and education. There is also the presence of racism which some see as a very important explaining factor. Some argue that for many diseases racial differences would disappear if all environmental factors could be controlled for. Race-based medicine is the term for medicines that are targeted at specific ethnic clusters, which are shown to have a propensity for a certain disorder. Critics are concerned that the trend of research on race specific pharmaceutical treatments will result in inequitable access to pharmaceutical innovation, and smaller minoritized groups may be ignored.

Health disparities based on race also exist. Similar to the difference in life expectancy found between the rich and the poor, affluent white women live 14 years longer in the U.S. (81.1 years) than poor black men (66.9 years). There is also evidence that blacks receive less aggressive medical care than whites, similar to what happens with women compared to men. Black men describe their visits to doctors as stressful, and report that physicians do not provide them with adequate information to implement the recommendations they are given.

Another contributor to the overall worse health of blacks is the incident of HIV/AIDS; the rate of new AIDS cases is ten times higher among blacks than whites, and blacks are 20 times as likely to have HIV/AIDS as are whites. Health disparities are well documented in minoritized populations such as African Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos. When compared to European Americans, these minoritized groups have higher incidence of chronic diseases, higher mortality, and poorer health outcomes. People from minoritized groups also have higher rates of cardiovascular disease, HIV/AIDS, and infant mortality than whites. American ethnic groups can exhibit substantial average differences in disease incidence, disease severity, disease progression, and response to treatment.

Infant mortality is another place where racial disparities are quite evident. In fact, infant mortality rates are 14 of every 1000 births for black, non-Hispanics compared to 6 of every 1000 births for whites. Another disparity is access to health care and insurance. In California, more than half (59 percent) of Hispanics go without health care. Also, almost 25 percent of Latinos do not have health insurance, as opposed to 10 percent of Whites.

There is a controversy regarding race as a method for classifying humans. The continued use of racial categories has been criticized. Apart from the general controversy regarding race, some argue that the continued use of racial categories in health care, and as risk factors, could result in increased stereotyping and discrimination in society and health services. There is general agreement that a goal of health-related genetics should be to move past the weak surrogate relationships of racial health disparity and get to the root causes of health and disease. This includes research which strives to analyze human genetic variation in smaller groups across the world.

VIEW THIS Learn more about How History Has Shaped Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities by viewing KFF’s A Timeline of Policies and Events in the United States from 1808 to present day.

Intersectionality

Social identities, or our social group memberships, shape our perceptions, interactions, and choice. Rather than personality traits or interests that make up your identity and sense of self, social identities describe the socially constructed groups that are present in specific environments within human societies. Our multiple identities are connected in ways that uniquely shape our experience. They may overlap and interact with each other in complex ways. It is especially important to be aware of the social identities that are important to you and the complex ways in which your different identities intersect, and recognize how certain social identities may carry unearned advantages or disadvantages with them (Crenshaw, 1989). For example, a young person with a disability may experience discrimination differently than an elderly person with a disability; women of color experience discrimination in a completely different way than men of color, or than white women.

Health-related stigma is a complex phenomenon rooted in social inequality, power asymmetry, and systemic hierarchy that mediate the process of stigmatization by othering and oppressing those affected. Such experiences of discrimination, oppression, and marginalization – enacted and reinforced by systems, institutions, and social actors – often have negative social, psychological, behavioral, and medical effects on people living with stigmatized health conditions. Further adding to the complexity, studies have found that health-related stigma does not exist in isolation, but actually interacts and intersects with other forms of social marginalization and oppression to create a compounding experience of stigma which negatively impacts those affected.

With emerging studies, researchers have found linkages of stigma associated with health conditions to other forms of marginalization due to race, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, age, etc. Studies have reported on such intersections of health-related stigma with other forms of social oppression and inequities using different terms like “double stigma” or “multiple stigmas” depending on the number of social categories explored, or as “intensified stigma” to describe the compounded experience of such oppressions. Such intersectional experience of stigma associated with a person’s health condition and adversities related to oppressive social identity/inequalities like gender, sexuality, and poverty can lead to concealment of the condition, social exclusion and isolation, and hamper access to health services, employment, and education. These evidences of intersectional relationship between health-related stigma and other forms of social marginalization indicate that stigma related to health conditions is not only a public health issue, but also a social justice issue. Further, it also shows prospects and value of embedding the concept of intersectionality into the theory of health-related stigma to elaborate and improve on the understanding of stigma associated with health conditions.

The concept of intersectionality was first introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw in order to highlight the dynamics between race and gender, and the overlapping oppressions that African American women face as a result of such an intersection. Intersectionality, as a theory, acknowledges the complexity and multidimensionality of people’s lives, and posits that the social oppression they may experience actually originate from an intersection of different social inequalities and oppressive identities rather than from a singular marginalized identity. The theory also acknowledges how such intersectional dynamics between different social inequalities and identities are contextual and may change over time and be different in different cultural and geographical settings. Intersectionality thus has much to offer to the field of health-related stigma in providing an improved understanding of the dynamic interaction and interplay of different social oppressions and marginalized identities and how they shape the experience of stigma among people living with health conditions.

WATCH THIS video below or online to learn more about intersectionality in healthcare:

Implicit Bias

Let’s take a look at how we form our biases. It is natural to have biases. Bias means a tendency toward or against someone or something. We react to the messages we receive in our environment. Although the word bias sometimes has a negative connotation, it is unavoidable in our everyday lives—we all have preferences and predispositions. Bias becomes an ethical problem when it prevents you from making a fair or reasoned choice about something, such as a hiring decision.

In this regard, implicit bias (also known as unconscious bias or implicit stereotype) is particularly important. As the name suggests, unconscious or implicit bias refers to stereotypes about people that remain hidden to the person who holds them. Unconscious biases can be extremely harmful in many circumstances, for instance, in healthcare, law enforcement, education, human resources, and public communication. Those messages often lie beneath the surface in our unconscious which makes it difficult to address as often we are unaware of them. They have an effect on how we make decisions in regards to our biases/stereotypes about race, class, sexual orientation, family structure, religion, etc.

Implicit bias refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner. Key characteristics of implicit bias include:

Implicit biases are pervasive. Everyone possesses them, even people with commitments to impartiality such as judges.

Implicit and explicit biases are related but distinct mental constructs. They are not mutually exclusive and may even reinforce each other.

The implicit associations we hold do not necessarily align with our declared beliefs or even reflect stances we would explicitly endorse.

We generally tend to hold implicit biases that favor our own in-group, though research has shown that we can still hold implicit biases against our in-group.

Implicit biases are malleable. Our brains are incredibly complex, and the implicit associations that we have formed can be gradually unlearned through a variety of debiasing techniques.

The evidence indicates that healthcare professionals exhibit the same levels of implicit bias as the wider population. A patient should not expect to receive a lower standard of care because of their race, age or any other irrelevant characteristic. However, implicit associations may influence our judgements resulting in bias. In addition to affecting judgements, implicit biases manifest in our non-verbal behavior towards others, such as frequency of eye contact and physical proximity. Implicit biases explain a potential dissociation between what a person explicitly believes and wants to do (e.g. treat everyone equally) and the hidden influence of negative implicit associations on her thoughts and action (e.g. perceiving a black patient as less competent and thus deciding not to prescribe the patient a medication).

The term ‘bias’ is typically used to refer to both implicit stereotypes and prejudices and raises serious concerns in healthcare. Psychologists often define bias broadly; such as ‘the negative evaluation of one group and its members relative to another’. Another way to define bias is to stipulate that an implicit association represents a bias only when likely to have a negative impact on an already disadvantaged group; e.g. if someone associates young girls with dolls, this would count as a bias. It is not itself a negative evaluation, but it supports an image of femininity that may prevent girls from excelling in areas traditionally considered ‘masculine’ such as mathematics. Another option is to stipulate that biases are not inherently bad, but only to be avoided when they incline us away from the truth.

In healthcare, we need to think carefully about exactly what is meant by bias. To fulfil the goal of delivering impartial care, healthcare professionals should be wary of any kind of negative evaluation they make that is linked to membership of a group or to a particular characteristic. The psychologists’ definition of bias thus may be adequate for the case of implicit prejudice; there are unlikely, in the context of healthcare, to be any justified reasons for negative evaluations related to group membership. The case of implicit stereotypes differs slightly because stereotypes can be damaging even when they are not negative per se. At least at a theoretical level, there is a difference between an implicit stereotype that leads to a distorted judgement and a legitimate association that correctly tracks real world statistical information. Here, the other definitions of bias presented above may prove more useful.

The majority of people tested from all over the world and within a wide range of demographics show responses to the most widely used test of implicit attitudes, the Implicit Association Test (IAT), that indicate a level of implicit anti-black bias. Other biases tested include gender, ethnicity, nationality and sexual orientation; there is evidence that these implicit attitudes are widespread among the population worldwide and influence behavior outside the laboratory. For instance, one widely cited study found that simply changing names from white-sounding ones to black-sounding ones on resumes in the US had a negative effect on callbacks. Implicit bias was suspected to be the culprit, and a replication of the study in Sweden, using Arab-sounding names instead of Swedish-sounding names, did in fact find a correlation between the HR professionals who preferred the resumes with Swedish-sounding names and a higher level of implicit bias towards Arabs.

We may consciously reject negative images and ideas associated with disadvantaged groups (and may belong to these groups ourselves), but we have all been immersed in cultures where these groups are constantly depicted in stereotyped and pejorative ways. Hence the description of ‘aversive racists’: those who explicitly reject racist ideas, but who are found to have implicit race bias when they take a race IAT. Although there is currently a lack of understanding of the exact mechanism by which cultural immersion translates into implicit stereotypes and prejudices, the widespread presence of these biases in egalitarian-minded individuals suggests that culture has more influence than many previously thought.

The implicit biases of concern to health care professionals are those that operate to the disadvantage of those who are already vulnerable. Examples include minority ethnic populations, immigrants, the poor, low health-literacy individuals, sexual minorities, children, women, the elderly, the mentally ill, the overweight and the disabled, but anyone may be rendered vulnerable given a certain context. The vulnerable in health-care are typically members of groups who are already disadvantaged on many levels. Work in political philosophy, such as the De-Shalit and Wolff concept of ‘corrosive disadvantage’, a disadvantage that is likely to lead to further disadvantages, is relevant here. For instance, if a person is poor and constantly worried about making ends meet, this is a disadvantage in itself, but can be corrosive when it leads to further disadvantages. In a country such as Switzerland, where private health insurance is mandatory and yearly premiums can be lowered by increasing the deductible, a high deductible may lead such a person to refrain from visiting a physician because of the potential cost incurred. This, in turn, could mean that the diagnosis of a serious illness is delayed leading to poorer health. In this case, being poor is a corrosive disadvantage because it leads to a further disadvantage of poor health.

The presence of implicit biases among healthcare professionals and the effect on quality of clinical care is a cause for concern. In the US, racial healthcare disparities are widely documented and implicit race bias is one cause.

READ THIS Read the article “Recognizing the Unconscious Barriers to Quality Care and Diversity in Medicine” from Cardiology Magazine (2020) to learn more about implicit biases and the intersections with healthcare, as well as some strategies for confronting your own implicit biases.

Confronting Implicit Bias

One well-known model for confronting implicit bias is the FLEX model, created by Interactive Business Inclusion Solutions (IBIS) consulting group and used here as seen in Brown University discussion guide for understanding the impact of unconscious bias.

The FLEX Model |

|

|

FOCUS WITHIN

|

Recognize how your experience has shaped your perspective. Stick to facts and don’t make assumptions. Turn frustration into curiosity. |

|

LEARN ABOUT OTHERS

|

Recognize how their experiences have shaped their perspectives. Consider how they might see the situation and what is important to them. Think about how your actions may have impacted them. |

|

ENGAGE IN INCLUSIVE DIALOGUE

|

Ask open-ended questions. Listen to understand, not debate. Offer your views without defensiveness or combativeness. Disentangle impact from intent. Avoid blame, think contribution. |

|

EXPAND YOUR OPTIONS

|

Brainstorm possible options. Be flexible about different ways to reach a common goal. Experiment and evaluate. Seek out diverse perspectives. |

TRY THIS: Complete a Continuing Education Activity through “Stat Pearls” on Implicit Bias to learn more about how clinicians can reduce the harm of implicit bias in their work.

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health are economic and social conditions that influence the health of people and communities. These conditions are shaped by the amount of money, power, and resources that people have, all of which are influenced by policy choices. Social determinants of health affect factors that are related to health outcomes. Factors related to health outcomes include:

- How a person develops during the first few years of life (early childhood development)

- How much education a person obtains

- Being able to get and keep a job

- What kind of work a person does

- Having food or being able to get food (food security)

- Having access to health services and the quality of those services

- Housing status

- How much money a person earns

- Discrimination and social support

WATCH THIS introductory overview video below or online on Social Determinants of Health from PsychHub:

Determinants of health

Determinants of health are factors that contribute to a person’s current state of health. These factors may be biological, socioeconomic, psychosocial, behavioral, or social in nature. Scientists generally recognize five determinants of health of a population:

- Genes and biology: for example, sex and age

- Health behaviors: for example, alcohol use, injection drug use (needles), unprotected sex, and smoking

- Social environment or social characteristics: for example, discrimination, income, and gender

- Physical environment or total ecology: for example, where a person lives and crowding conditions

- Health services or medical care: for example, access to quality health care and having or not having insurance

Other factors that could be included are culture, social status, and healthy child development. Scientists do not know the precise contributions of each determinant at this time.

Determinants of health and social determinants of health

In theory, genes, biology, and health behaviors together account for about 25% of population health. Social determinants of health represent the remaining three categories of social environment, physical environment/total ecology, and health services/medical care. These social determinants of health also interact with and influence individual behaviors as well. More specifically, social determinants of health refer to the set of factors that contribute to the social patterning of health, disease, and illness.

READ THIS Social Determinants of Health are widely broken down into 5 categories: Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context. Find summaries about each of those categories on the HealthyPeople2030’s website. HealthyPeople2030 is an initiative by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Why is addressing the role of social determinants of health important?

Addressing social determinants of health is a primary approach to achieving health equity. Health equity is “when everyone has the opportunity to ‘attain their full health potential’ and no one is ‘disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of their social position or other socially determined circumstance.” Health equity has also been defined as “the absence of systematic disparities in health between and within social groups that have different levels of underlying social advantages or disadvantages—that is, different positions in a social hierarchy.” Social determinants of health such as poverty, unequal access to health care, lack of education, stigma, and racism are underlying, contributing factors of health inequities. Health inequality refers to the unequal distribution of environmental health hazards and access to health services between demographic groups, including social classes. For example, poor and affluent urban communities in the United States are geographically close to each other and to hospitals. Still, the affluent communities are more likely to have access to fresh produce, recreational facilities for exercise, preventative healthcare programs, and routine medical visits. Consequently, affluent communities are likely to have better health outcomes than nearby impoverished ones. The role of socioeconomic status in determining access to healthcare results in heath inequality between the upper, middle, and lower or working classes, with the higher classes having more positive health outcomes.

A person’s social class has a significant impact on their physical health, their ability to receive adequate medical care and nutrition, and their life expectancy. While gender and race play significant roles in explaining healthcare inequality in the United States, socioeconomic status (SES) is the greatest social determinant of an individual’s health outcome.

Individuals with a low SES in the United States experience a wide array of health problems as a result of their economic position. They are unable to use healthcare as often as people of higher status and when they do, it is often of lower quality. Additionally, people with low SES tend to experience a much higher rate of health issues than those of high SES. Many social scientists hypothesize that the higher rate of illness among those with low SES can be attributed to environmental hazards. For example, poorer neighborhoods tend to have fewer grocery stores and more fast food chains than wealthier neighborhoods, increasing nutrition problems and the risk of conditions, such as heart disease. Similarly, poorer neighborhoods tend to have fewer recreational facilities and higher crime rates than wealthier ones, which decreases the feasibility of routine exercise.

In addition to having an increased level of illness, lower socioeconomic classes have lower levels of health insurance than the upper class. Much of this disparity can be explained by the tendency for middle- and upper-class people to work in professions that provide health insurance benefits to employees, while lower status occupations often do not provide benefits to employees. For many employees who do not have health insurance benefits through their job, the cost of insurance can be prohibitive. Without insurance, or with inadequate insurance, the cost of healthcare can be extremely high. Consequently, many uninsured or poorly insured individuals do not have access to preventative care or quality treatment. This group of people has higher rates of infant mortality, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and disabling physical injuries than are seen among the well insured.

Psychology of Scarcity

Scarcity theory explains several behaviors and decisions of people who face scarcity in a particular area of life. Mullainathan and Shafir (2013) define scarcity as “having less than you feel you need” (p. 4). Scarcity can be experienced in several contexts, e.g., when people are dieting, when being thirsty, by facing deadlines, in the case of loneliness, and when facing poverty (Cannon et al. 2019). The theory builds on cognitive psychological research regarding several features of human cognition that affect (economic) decision making. The key idea of scarcity theory is that scarcity itself induces a specific mindset by affecting how people think and decide, and subsequently affect human behaviors. Poverty is the key domain to which scarcity theory has been applied (Zhao and Tomm 2018).

Mullainathan and Shafir (2013) first talked about the Psychology of Scarcity as it relates to decision-making in their book, Scarcity. Scarcity theory integrates insights from cognitive psychology and economics and attempts to explain a wide range of behaviors often used when people do not have full economic resources. People in poverty have to make decisions under severe financial conditions that change the way they feel and think. For example, tight budgets and uncertain income require them to juggle current and upcoming needs. These urgent demands consume cognitive resources, such as attention, executive control, and working memory, leaving fewer resources for non-pressing demands. As a consequence, financial scarcity forces people into behaviors like short-term planning instead of future planning, which then may perpetuate the condition of poverty.

Scarcity theory suggests three main outcomes related to social-economic status. First, economic uncertainty leads to an attentional focus on scarcity-related demands and neglect of other issues, causing overborrowing. Second, economic uncertainty induces trade-off thinking, i.e. weighing a particular expense against other possible expenses, resulting in more consistent consumption decisions. Third, economic uncertainty reduces mental bandwidth (cognitive capacity and cognitive control), increasing time discounting (choosing rewards or items that are available now versus waiting for possibly better options in the future) and risk aversion.

READ THIS For more information on what psychological scarcity means, read “Scarcity and Consumer Decision Making: Is scarcity a mindset, a threat, a reference point, or a journey?”

LISTEN TO THIS For more information on how poverty and wealth affect our thinking, listen to “Too Little, Too Much: How poverty and wealth affect our minds,” a podcast episode by Hidden Brain.

Education and Health

Formal Education

An adult’s education level is a robust predictor of their health in the United States. Compared to their less-educated peers, adults with more education have better overall health, are less likely to develop morbidities and disability, and tend to live longer and spend more of those years in good health. The magnitude of these disparities is striking. Among U.S. adults in their mid-40s, <15% of those without a high school diploma reported being in excellent health, compared to 24% of those with a high school diploma, over 40% of those with a 4-year college degree, and over 50% of those with a doctorate or professional degree. In recent decades, disparities in health between adults with and without a 4-year college degree have become especially pronounced.

A key framework for understanding the education-health association is Fundamental Cause Theory (FCT). It asserts that education is important in contexts with the resources to avoid disease and premature death, yet more-educated persons have greater access to those resources. Indeed, compared to their less-educated peers, more-educated U.S. adults have greater access to four types of resources: economic well-being, social ties, healthy behaviors, and quality health care. Those four types of resources, or “mechanisms,” help explain a large share of the education-health association in the country today.

Health Literacy

Health literacy is an individual’s ability to read, understand, and use healthcare information to make decisions and follow instructions for treatment. Health literacy is of continued and increasing concern for health professionals, as it is a primary factor behind health disparities. While problems with health literacy are not limited to minority groups, the problem can be more pronounced in these groups than in whites due to socioeconomic and educational factors.

There are many factors that determine the health literacy level of health education materials or other health interventions. Reading level, numeracy level, language barriers, cultural appropriateness, format and style, sentence structure, use of illustrations, scope of intervention, and numerous other factors will affect how easily health information is understood and followed. The mismatch between a clinician’s level of communication and a patient’s ability to understand can lead to medication errors and adverse medical outcomes. The lack of health literacy affects all segments of the population, although it is disproportionate in certain demographic groups, such as the elderly, ethnic minorities, recent immigrants and persons with low general literacy. Health literacy skills are not only a problem in the public. Health care professionals (doctors, nurses, public health workers) can also have poor health literacy skills, such as a reduced ability to clearly explain health issues to patients and the public.

Due to the increasing influence of the internet for information-seeking and health information distribution purposes, eHealth literacy has become an important topic of research in recent years. The eHealth literacy model is also referred to as the Lily model, which incorporates the following literacies, each of which are instrumental to the overall understanding and measurement of eHealth literacy: basic literacy, computer literacy, information literacy, media literacy, science literacy, health literacy.

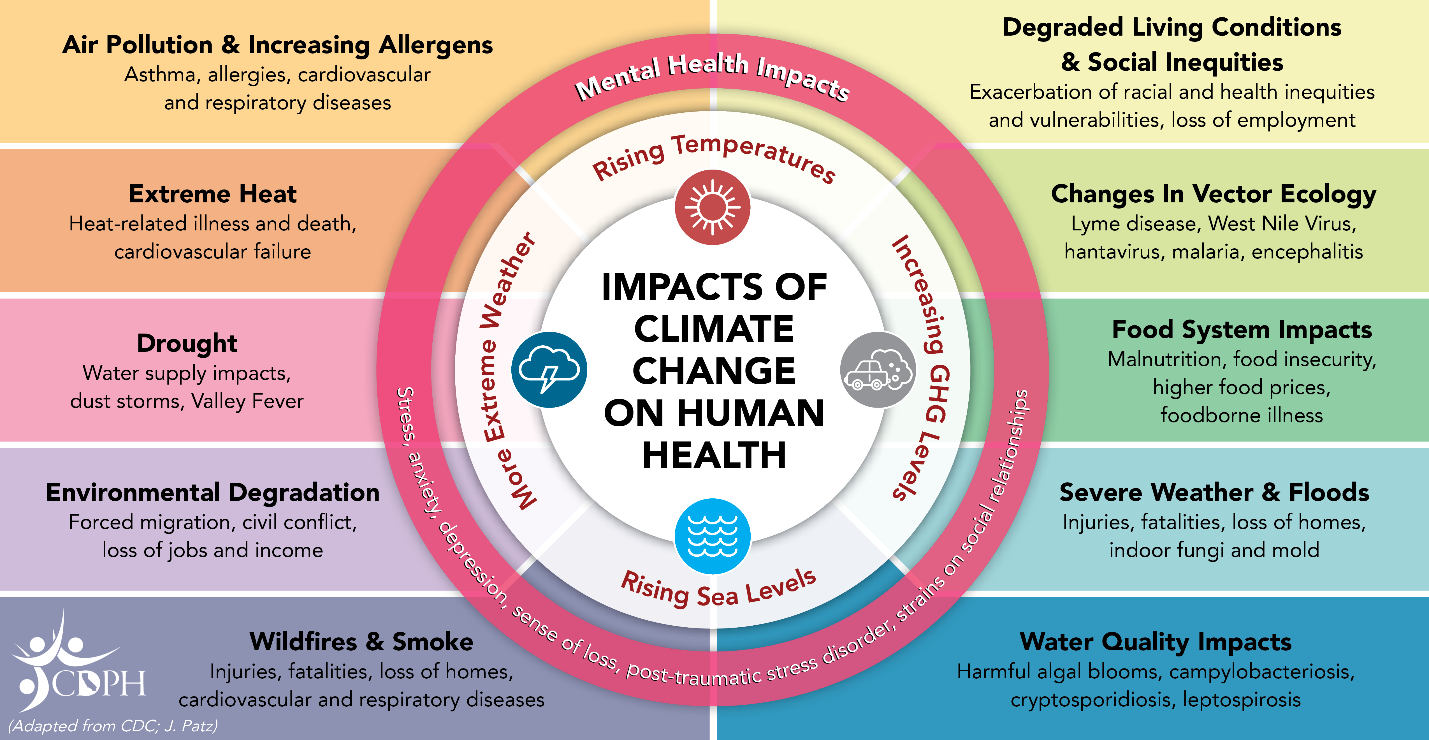

Environmental Factors affecting Health

Decreased Health

As climate change and pollution continue to worsen throughout the globe, the impacts that they have on the health of all individuals are ever evolving and changing. Across the world, life expectancy is dropping by a couple of months to 2 years as a result of air pollution. The Journal of Environmental Science & Technology Letters estimates that if all countries met the World Health Organization Air Quality Guideline, then the median population-weighted life expectancy would increase by 0.6 years.

Air pollution is not the only environmental hazard that impacts the health of individuals. The Healthy People 2020 Environmental Health initiative created by the United States Department of Health and Human Services highlights 6 themes that are key components of environmental health. These themes are outdoor air quality, surface and ground water quality, toxic substances and hazardous wastes, homes and communities, infrastructure and surveillance, and global environmental health.

In recent years, the effects of climate change can be felt not just in the United States, but also across the planet. Rising temperatures, more incidences of extreme weather, rising sea levels due to the melting of the ice caps, and increasing levels of carbon dioxide have all had an impact on human health, as the above graphic demonstrates. For example, the quality of water has been noticeably influenced by many different components of climate change. A recent example is the ongoing red tide disaster that is affecting Florida.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), red tide is a commonly used term for a particular strain of harmful algae bloom. Harmful algae blooms are “when colonies of algae…grow out of control while producing toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and birds” (NOAA 2018). Red tide blooms have been documented since the 1800s, but new organisms that cause harmful algae blooms have been recorded over time and in the 21st century the red tides have spread from being located solely in the eastern Gulf of Mexico to the eastern coast of Mexico.

The three main environmental factors that affect a bloom are the salinity of water, temperature, and wind. The severity of red tides has increased in recent years due to increasing temperatures, alteration of ocean currents, stimulation of photosynthesis due to rising carbon monoxide levels, and intensification or weakening local nutrient upwelling. If climate change continues to be an issue, the likely effects will be an increase in warm-water species at the detriment of cold-water species, changes in the seasonal window of growth of various algae species, and wide-ranging impacts on local ecology, especially marine food webs.

Increased Health

Recent research on longevity reveals that people in some regions of the world live significantly longer than people elsewhere. Efforts to study the common factors between these areas and the people who live there is known as blue zone research. Blue zones are regions of the world where Dan Buettner claims people live much longer than average. The term first appeared in his November 2005 National Geographic magazine cover story, “The Secrets of a Long Life.” Buettner identified five regions as “Blue Zones”: Okinawa (Japan); Sardinia (Italy); Nicoya (Costa Rica); Icaria (Greece); and the Seventh-day Adventists in Loma Linda, California. He offers an explanation, based on data and first-hand observations, for why these populations live healthier and longer lives than others.

The people inhabiting blue zones share common lifestyle characteristics that contribute to their longevity. The Venn diagram below highlights the following six shared characteristics among the people of Okinawa, Sardinia, and Loma Linda blue zones. Though not a lifestyle choice, they also live as isolated populations with a related gene pool.

Blue zones share many common healthy habits contributing to longer lifespans.

- Family – put ahead of other concerns

- Less smoking

- Semi-vegetarianism – the majority of food consumed is derived from plants

- Constant moderate physical activity – an inseparable part of life

- Social engagement – people of all ages are socially active and integrated into their communities

- Legumes – commonly consumed

In his book, Buettner provides a list of nine lessons, covering the lifestyle of blue zones people:

Moderate, regular physical activity.

- Life purpose.

- Stress reduction.

- Moderate caloric intake.

- Plant-based diet.

- Moderate alcohol intake, especially wine.

- Engagement in spirituality or religion.

- Engagement in family life.

- Engagement in social life.

Cultural Factors Affecting Health

Culture

Humans are social creatures. Since the dawn of Homo sapiens nearly 250,000 years ago, people have grouped together into communities in order to survive. Living together, people form common habits and behaviors—from specific methods of childrearing to preferred techniques for obtaining food. In modern-day Paris, many people shop daily at outdoor markets to pick up what they need for their evening meal, buying cheese, meat, and vegetables from different specialty stalls. In the United States, the majority of people shop once a week at supermarkets, filling large carts to the brim. How would a Parisian perceive U.S. shopping behaviors that Americans take for granted?

Note that in the above comparison we are looking at cultural differences on display in two distinct places, suburban America and urban France, even though we are examining a behavior that people in both places are engaged in. It’s important to note that geographical place is an important factor in culture—beliefs and practices, and society—the social structures and organization of individuals and groups.

Almost every human behavior, from shopping to marriage to expressions of feelings, is learned. In the United States, people tend to view marriage as a choice between two people, based on mutual feelings of love. In other nations and in other times, marriages have been arranged through an intricate process of interviews and negotiations between entire families, or in other cases, through a direct system, such as a “mail order bride.” To someone raised in New York City, the marriage customs of a family from Nigeria may seem strange or even wrong. Conversely, someone from a traditional Kolkata family might be perplexed with the idea of romantic love as the foundation for marriage and lifelong commitment. In other words, the way in which people view marriage depends largely on what they have been taught.

Behavior based on learned customs is not a bad thing. Being familiar with unwritten rules helps people feel secure and “normal.” Also, perhaps such cultural traditions are comforting in that they seem to have already worked well enough for our forebears to have retained them. Most people want to live their daily lives confident that their behaviors will not be challenged or disrupted. But even an action as seemingly simple as commuting to work evidences a great deal of cultural propriety and learned behaviors.

Take the case of going to work on public transportation. Whether people are commuting in Dublin, Cairo, Mumbai, or San Francisco, many behaviors will be the same, but significant differences also arise between cultures. Typically, a passenger will find a marked bus stop or station, wait for his bus or train, pay an agent before or after boarding, and quietly take a seat if one is available. But when boarding a bus in Cairo, passengers might have to run, because buses there often do not come to a full stop to take on patrons. Dublin bus riders would be expected to extend an arm to indicate that they want the bus to stop for them. And when boarding a commuter train in Mumbai, passengers must squeeze into overstuffed cars amid a lot of pushing and shoving on the crowded platforms. That kind of behavior would be considered the height of rudeness in the United States, but in Mumbai it reflects the daily challenges of getting around on a train system that is taxed to capacity.

In this example of commuting, culture consists of both intangible things like beliefs and thoughts (expectations about personal space, for example) and tangible things (bus stops, trains, and seating capacity).

The objects or belongings of a group of people are considered material culture. Metro passes and bus tokens are part of material culture, as are automobiles, stores, and the physical structures where people worship, or engage in other recognizable patterns of behavior.

Nonmaterial culture, in contrast, consists of the ideas, attitudes, and beliefs of a society. Material and nonmaterial aspects of culture are linked, and physical objects often symbolize cultural ideas. A metro pass is a material object, but it represents a form of nonmaterial culture, namely, capitalism, and the acceptance of paying for transportation. Clothing, hairstyles, and jewelry are part of material culture, but the appropriateness of wearing certain clothing for specific events reflects nonmaterial culture. A school building belongs to material culture, but the teaching methods and educational standards within it are part of education’s nonmaterial culture. These material and nonmaterial aspects of culture can vary subtly or greatly from region to region. As people travel farther afield, moving from different regions to entirely different parts of the world, certain material and nonmaterial aspects of culture become dramatically unfamiliar. What happens when we encounter different cultures? As we interact with cultures other than our own, we become more aware of the differences and commonalities between others’ symbolic and material worlds and our own.

Values and Beliefs

The first, and perhaps most crucial, elements of culture we will discuss are its values and beliefs. Values are a culture’s standard for discerning what is good and just in society. Values are deeply embedded and critical for transmitting and teaching a culture’s beliefs. Beliefs are the tenets or convictions that people hold to be true. Individuals in a society have specific beliefs, but they also share collective values. To illustrate the difference, Americans commonly believe in the American Dream—that anyone who works hard enough will be successful and wealthy. Underlying this belief is the American value that wealth is good and important.

Values help shape a society by suggesting what is good and bad, beautiful and ugly, to be sought or avoided. Consider the value that the United States places upon youth. Children represent innocence and purity, while an adult who is youthful in appearance signifies sexual vitality. Shaped by this value, individuals spend millions of dollars each year on cosmetic products and surgeries to look young and beautiful. The United States also has an individualistic culture, meaning people place a high value on individuality and independence. In contrast, many other cultures are collectivist, meaning the welfare of the group and group relationships is a primary value.

Living up to a culture’s values can be difficult. It’s easy to value good health, but it’s hard to quit smoking. Marital monogamy is valued, but many spouses engage in infidelity. Cultural diversity and equal opportunities for all people are valued in the United States, yet the country’s highest political offices have been dominated by white men.

Values often suggest how people should behave, but they don’t accurately reflect how people actually do behave. Values portray an ideal culture; the standards society would like to embrace and live up to. But ideal culture differs from real culture; the way society actually is, based on what occurs and exists. In an ideal culture, there would be no traffic accidents, murders, poverty, or racial tension. But in real culture, police officers, lawmakers, educators, and social workers constantly strive to prevent or repair those accidents, crimes, and injustices. American teenagers are encouraged to value celibacy. However, the number of unplanned pregnancies among teens reveals that not only is the ideal hard to live up to, but the value alone is not enough to spare teenagers the potential consequences of having sex.

One way societies strive to put values into action is through sanctions: rewards and punishments that encourage people to live according to their society’s ideas about what is good and right. When people observe the norms of society and uphold its values, they are often rewarded. Norms define how to behave in accordance with what a society has defined as good, right, and important, and most members of the society adhere to them. A boy who helps an elderly woman board a bus may receive a smile and a “thank you.” A business manager who raises profit margins may receive a quarterly bonus. People positively sanction certain behaviors by giving their support, approval, or permission, or negatively sanction them by invoking formal policies of disapproval and nonsupport. Sanctions are a form of social control, a way to encourage conformity to cultural norms. Sometimes people conform to norms in anticipation or expectation of positive sanctions: good grades, for instance, may mean praise from parents and teachers. From a criminal justice perspective, properly used social control is also inexpensive crime control. Utilizing social control approaches pushes most people to conform to societal rules, regardless of whether authority figures (such as law enforcement) are present.

When people go against a society’s values, they are punished. A boy who shoves an elderly woman aside to board the bus first may receive frowns or even a scolding from other passengers. A business manager who drives away customers will likely be fired. Breaking norms and rejecting values can lead to cultural sanctions such as earning a negative label—lazy, no-good bum—or to legal sanctions, such as traffic tickets, fines, or imprisonment.

Values are not static; they vary across time and between groups as people evaluate, debate, and change collective societal beliefs. Values also vary from culture to culture. For example, cultures differ in their values about what kinds of physical closeness are appropriate in public. It’s rare to see two male friends or coworkers holding hands in the United States where that behavior often symbolizes romantic feelings. But in many nations, masculine physical intimacy is considered natural in public. This difference in cultural values came to light when people reacted to photos of former president George W. Bush holding hands with the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia in 2005. An example of nonmaterial culture, the simple gesture of hand-holding carries great symbolic differences across cultures.

In order to improve health behaviors, cultural factors affecting health behavior and health care services need to be clearly recognized. The individuals’ beliefs about health, attitudes and behaviors, past experiences, treatment practices, in short, their culture, play a vital role in improving health, preventing and treating diseases.

Culture and Health

What does it mean to be “healthy”? It may seem odd to ask the question, but health is not a universal concept and each culture values different aspects of well-being. At the most basic level, health may be perceived as surviving each day with enough food and water, while other definitions of health may be based on being free of diseases or emotional troubles. Complicating things further is the fact that that each culture has a different causal explanation for disease. For instance, in ancient Greece health was considered to be the product of unbalanced humors or bodily fluids. The four humors included black bile, phlegm, yellow bile, and blood. The ancient Greeks believed that interactions among these humors explained differences not only in health, but in age, gender, and general disposition. Various things could influence the balance of the humors in a person’s body including substances believed to be present in the air, changes in diet, or even temperature and weather. An imbalance in the humors was believed to cause diseases, mood problems, and mental illness.

Cultural attitudes affect how medical conditions will be perceived and how individuals with health problems will be regarded by the wider community. There is a difference, for instance, between a disease, which is a medical condition that can be objectively identified, and an illness, which is the subjective or personal experience of feeling unwell. Illnesses may be caused by disease, but the experience of being sick encompasses more than just the symptoms caused by the disease itself. Illnesses are, at least in part, social constructions: experiences that are given meaning by the relationships between the person who is sick and others.

The course of an illness worsens, for instance, if the dominant society views the sickness as a moral failing. Obesity is an excellent example of the social construction of illness. The condition itself is a result of culturally induced habits and attitudes toward food, but despite this strong cultural component, many people regard obesity as a preventable circumstance, blaming individuals for becoming overweight. This attitude has a long cultural history. Consider for instance the religious connotations within Christianity of “gluttony” as a sin. Such socially constructed stigma influences the subjective experience of the illness. Obese women have reported avoiding visits to physicians for fear of judgment and as a result may not receive treatments necessary to help their condition.

WATCH THIS TED Talk below or online by Peter Attia, a surgeon and medical researcher related to an obese woman who had to have her foot amputated, a common result of complications from obesity and diabetes. Even though he was a physician, he judged the woman to be lazy. “If you had just tried even a little bit,” he had thought to himself before surgery. However, as Attia observes, high rates of obesity in the United States are a reflection of the types of foods Americans have learned to consume as part of their cultural environment. In addition, the fact that foods that are high in sugars and fats are inexpensive and abundant, while healthier foods are expensive and unavailable in some communities, highlights the economic and social inequalities that contribute to the disease.

Culture-Bound Syndromes

A culture-bound syndrome is an illness recognized only within a specific culture. These conditions, which combine emotional or psychological with physical symptoms, are not the result of a disease or any identifiable physiological dysfunction. Instead, culture-bound syndromes are somatic, meaning they are physical manifestations of emotional pain. The existence of these conditions demonstrates the profound influence of culture and society on the experience of illness.

Anorexia

Anorexia is considered a culture bound syndrome because of its strong association with cultures that place a high value on thinness as a measure of health and beauty. When we consider concepts of beauty from cultures all over the world, a common view of beauty is one of someone with additional fat. This may be because having additional fat in a place where food is expensive means that one is likely of a higher status. In societies like the United States where food is abundant, it is much more difficult to become thin than it is to become heavy. Although anorexia is a complex condition, medical anthropologists and physicians have observed that it is much more common in Western cultural contexts among people with high socioeconomic status. Anorexia, as a form of self-deprivation, has deep roots in Western culture and for centuries practices of self-denial have been associated with Christian religious traditions. In a contemporary context, anorexia may address a similar, but secular desire to assert self-control, particularly among teenagers.

During her research in Fiji, Anne Becker (2004) noted that young women who were exposed to advertisements and television programs from Western cultures (like the United States and Australia) became self-conscious about their bodies and began to alter their eating habits to emulate the thin ideal they saw on television. Anorexia, which had been unknown in Fiji, became an increasingly common problem. The same pattern has been observed in other societies undergoing “Westernization” through exposure to foreign media and economic changes associated with globalization.

Swallowing Frogs in Brazil

In Brazil, there are several examples of culture-bound syndromes that affect children as well as adults. Women are particularly susceptible to these conditions, which are connected to emotional distress. In parts of Brazil where poverty, unemployment, and poor physical health are common, there are cultural norms that discourage the expression of strong emotions such as anger, grief, or jealousy. Of course, people continue to experience these emotions, but cannot express them openly. Men and women deal with this problem in different ways. Men may choose to drink alcohol heavily, or even to express their anger physically by lashing out at others, including their wives. These are not socially acceptable behaviors for women who instead remark that they must suppress their feelings, an act they describe as having to “swallow frogs” (engolir sapos).

Nervos

Nervos (nerves) is a culture-bound syndrome characterized by symptoms such as headaches, trembling, dizziness, fatigue, stomach pain, tingling of the extremities and even partial paralysis. It is viewed as a result of emotional overload: a state of constant vulnerability to shock. Unexplained wounds on the body may be diagnosed as a different kind of illness known as “blood-boiling bruises.” Since emotion is culturally defined as a kind of energy that flows throughout the body, many believe that too much emotion can overwhelm the body, “boiling over” and producing symptoms. A person can become so angry, for instance, that his or her blood spills out from under the skin, creating bruises, or so angry that the blood rises up to create severe headaches, nausea, and dizziness. A third form of culture-bound illness, known as peito aberto (open chest) is believed to be occur when a person, most often a woman, is carrying too much emotional weight or suffering. In this situation, the heart expands until the chest becomes spiritually “open.” A chest that is “open” is dangerous because rage and anger from other people can enter and make a person sick.

Culture and Individuals

Cultural behaviors have important implications for human health. Socioeconomic status, gender, group memberships, values, and many other feelings, thoughts, and traits, all play into how individuals experience, conceptualize and react to their world. Therefore, a general understanding of cultural groups is insufficient for grasping a patient’s unique experience with health and illnesses. Additionally, structural inequalities and political economy play a critical, and often overlooked, role in health and disease. Understanding how behaviors are rooted in an individual’s unique cultural experience and as a response to social pressures can better equip medical professionals with the context, skills and empathy necessary for holistic care.

Healthcare providers can improve individual outcomes by thoroughly factoring in life experiences as part of understanding an individual’s health and treating their illnesses. Healthcare providers need to understand how identity, interpretation of illness, and the moral values of patients factor into building a trusting relationship that considers the patient’s life experiences in treatment plans. The American Nurses Association (ANA) refers to three reciprocal interactions in transcultural health care (explained further in the next section): the culture of the individual (patient), the culture of the nurse, and the culture of the environment in relation to the patient-nurse:

- Culture of the individual: When nurses understand the specific factors affecting individual health behaviors, they will be more successful in meeting their needs. Individuals’ beliefs about health, culture, past illness/health experiences form a holistic structure and play a vital role in improving the health of individuals. Culture is influential in how people think, speak the language, how to dress, believe, treat their patients and how to feed them and what to do with their funerals etc. Moreover, it plays a significant role in a variety of aspects such as new diagnostic methods, prognosis, symptomatic patterns and determination of whether there is an illness or not.

- Culture of the nurse: The patient’s culture is not the only factor influencing the patient-nurse relationship. The nurses’ own customs and traditions, beliefs and values are also important in transcultural relationships. The nurse’s self-awareness can be the starting point to understand the patient culturally.

- Culture of the environment: The last element of the transcultural trio is the culture of the environment. The environment is an integral part of the culture. Individuals as physical, ecological, sociopolitical and cultural beings are continuously interacting with each other. Nurses may have to intervene in the patient and family relationship because of frequent bureaucratic arrangements and procedures. The transcultural approach should be considered in a wide range of subjects, starting from asking if there are any religious practices to be followed or done by the patient during the hospitalization, and writing the signs in the hospital in two different languages.

READ THIS For more examples of the impact culture has on health beliefs, read the article “The Impact of Culture on Patient Education” which includes information on how culture influences health beliefs, strategies for working with patients in cross-cultural settings, doing a cultural assessment, using interpreters for non-English speaking patients, and models of care for cultural competence.

Transcultural Health Care

It is vital that health services are also appropriate for the target cultures to the extent that they are compatible with contemporary medical understanding. People’s beliefs and practices are part of the culture of the society in which they live. Cultural characteristics should be seen as a dynamic factor of health and disease. In order to be able to provide better health care, it is necessary to at least understand how the group receiving care perceives and responds to disease and health, and what cultural factors lie behind their behaviors.

Unless health care initiatives are based on cultural values, it will be impossible to achieve the goal and the care provided will be incomplete and fail. For this reason, healthcare providers should try to understand the cultural structure of a society. Health workers must collect cultural data to understand the attitudes of towards coping with illness, health promotion and protection.

Cultural differences and health beliefs have been recognized for many years as prior knowledge in practice. Despite that, cultural health care is unfortunately not part of a routine or common health practice. Knowing cultural beliefs related to health can enable us to build a framework for data collection in health care.

Today, health policies focus primarily on the prevention of health-related inequalities and discrimination, especially ethnic characteristics. In order for the societies to regulate health care that will meet the needs of different groups in terms of culture, all health team members must be equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills.

Cultural Competence

Cultural competence is the social awareness that everyone is unique, that different cultures and backgrounds affect how people think and behave, and that this awareness allows people to behave appropriately and perform effectively in culturally diverse environments. It involves “(a) the cultivation of deep cultural self-awareness and understanding (i.e., how one’s own beliefs, values, perceptions, interpretations, judgments, and behaviors are influenced by one’s cultural community or communities) and (b) increased cultural other-understanding (i.e., comprehension of the different ways people from other cultural groups make sense of and respond to the presence of cultural differences)” (Bennett, 2015).

In other words, cultural competency requires you to be aware of your own cultural practices, values, and experiences, and to be able to read, interpret, and respond to those of others. Such awareness will help you successfully navigate the cultural differences you will encounter in diverse environments. Cultural competency is critical to working and building relationships with people from different cultures; it is so critical, in fact, that it is now one of the most highly desired skills in the modern workforce.

WATCH THIS short video below or online with captions where representatives from Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care highlight the importance of Cultural Diversity and Cultural Competency in their work:

Cultural Competence: Transcultural Nursing

Nurses realize that people speak, behave, and act in many different ways due to the influential role that culture plays in their lives and their view of the world. Cultural competence is a lifelong process of applying evidence-based nursing in agreement with the cultural values, beliefs, worldview, and practices of patients to produce improved patient outcomes.

Culturally competent care requires nurses to combine their knowledge and skills with awareness, curiosity, and sensitivity about their patients’ cultural beliefs. It takes motivation, time, and practice to develop cultural competence, and it will evolve throughout your career. Culturally competent nurses have the power to improve the quality of care leading to better health outcomes for culturally diverse patients. Nurses who accept and uphold the cultural values and beliefs of their patients are more likely to develop supportive and trusting relationships with their patients. In turn, this opens the way for optimal disease and injury prevention and leads towards positive health outcomes for all patients.

The roots of providing culturally competent care are based on the original transcultural nursing theory developed by Dr. Madeleine Leininger. Transcultural nursing incorporates cultural beliefs and practices of individuals to help them maintain and regain health or to face death in a meaningful way. Read more about transcultural nursing theory in the following box.

Madeleine Leininger and the Transcultural Nursing Theory

Dr. Madeleine Leininger (1925-2012) founded the transcultural nursing theory. She was the first professional nurse to obtain a PhD in anthropology. She combined the “culture” concept from anthropology with the “care” concept from nursing and reformulated these concepts into “culture care.”

In the mid-1950s, no cultural knowledge base existed to guide nursing decisions or understand cultural behaviors as a way of providing therapeutic care. Leininger wrote the first books in the field and coined the term “culturally congruent care.” She developed and taught the first transcultural nursing course in 1966, and master’s and doctoral programs in transcultural nursing were launched shortly after. Dr. Leininger was honored as a Living Legend of the American Academy of Nursing in 1998.

Nurses have an ethical and moral obligation to provide culturally competent care to the patients they serve. The “Respectful and Equitable Practice” Standard of Professional Performance set by the American Nurses Association (ANA) states that nurses must practice with cultural humility and inclusiveness. The ANA Code of Ethics also states that the nurse should collaborate with other health professionals, as well as the public, to protect human rights, fight discriminatory practices, and reduce disparities. Additionally, the ANA Code of Ethics also states that nurses “are expected to be aware of their own cultural identifications in order to control their personal biases that may interfere with the therapeutic relationship. Self-awareness involves not only examining one’s culture but also examining perceptions and assumptions about the patient’s culture…nurses should possess knowledge and understanding how oppression, racism, discrimination, and stereotyping affect them personally and in their work.”

Developing cultural competence begins in nursing school, or earlier. Culture is an integral part of life, but its impact is often implicit. It is easy to assume that others share the same cultural values that you do, but each individual has their own beliefs, values, and preferences. Begin the examination of your own cultural beliefs and feelings by answering the questions on the next page.

The Process of Developing Cultural Competence

Dr. Josephine Campinha-Bacote is an influential nursing theorist and researcher who developed a model of cultural competence. The model asserts there are specific characteristics that a nurse becoming culturally competent possesses, including cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, and cultural encounters.

Cultural awareness is a deliberate, cognitive process in which health care providers become appreciative and sensitive to the values, beliefs, attitudes, practices, and problem-solving strategies of a patient’s culture. To become culturally aware, the nurse must undergo reflective exploration of personal cultural values while also becoming conscious of the cultural practices of others. In addition to reflecting on one’s own cultural values, the culturally competent nurse seeks to reverse harmful prejudices, ethnocentric views, and attitudes they have. Cultural awareness goes beyond a simple awareness of the existence of other cultures and involves an interest, curiosity, and appreciation of other cultures. Although cultural diversity training is typically a requirement for health care professionals, cultural desire refers to the intrinsic motivation and commitment on the part of a nurse to develop cultural awareness and cultural competency.

TRY THIS: Self-reflection on culturally responsive care

Reflect on the following questions carefully and contemplate your responses as you begin your journey of providing culturally responsive care as a nurse. (Questions are adapted from the Anti-Defamation League’s “Imagine a World Without Hate” Personal Self-Assessment Anti-Bias Behavior).

- Who are you? With what cultural group or subgroups do you identify?

- When you meet someone from another culture/country/place, do you try to learn more about them?

- Do you notice instances of bias, prejudice, discrimination, and stereotyping against people of other groups or cultures in your environment (home, school, work, TV programs or movies, restaurants, places where you shop)?

- Have you reflected on your own upbringing and childhood to better understand your own implicit biases and the ways you have internalized messages you received?

- Do you ever consider your use of language to avoid terms or phrases that may be degrading or hurtful to other groups?

- When other people use biased language and behavior, do you feel comfortable speaking up and asking them to refrain?

- How ready are you to give equal attention, care, and support to people regardless of their culture, socioeconomic class, religion, gender expression, sexual orientation, or other “difference”?

Acquiring cultural knowledge is another important step towards becoming a culturally competent nurse. Cultural knowledge refers to seeking information about cultural health beliefs and values to understand patients’ world views. To acquire cultural knowledge, the nurse actively seeks information about other cultures, including common practices, beliefs, values, and customs, particularly for those cultures that are prevalent within the communities they serve. Cultural knowledge also includes understanding the historical backgrounds of culturally diverse groups in society, as well as physiological variations and the incidence of certain health conditions in culturally diverse groups. Cultural knowledge is best obtained through cultural encounters with patients from diverse backgrounds to learn about individual variations that occur within cultural groups and to prevent stereotyping.