1 Module 1: Introduction to Developmental Psychology

Module 1 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Understand Psychology

Explain what psychology is and why it’s important for understanding people. - Learn About Developmental Psychology’s History

Describe key events and people who shaped the field of developmental psychology. - Know the Parts of Development

Identify the three main areas of development: physical, thinking (cognitive), and social/emotional (psychosocial). - Explore Big Questions in Development

Discuss important questions like whether development happens slowly or in stages and how both genetics and the environment matter. - Recognize Life Stages

List and describe the main stages of life, from before birth to old age. - Learn About Theories of Development

Compare different ideas about how people grow and change, like Piaget’s and Erikson’s theories. - Understand the Biopsychosocial Model

Explain how our body, mind, and social life work together to affect our health and development. - Understand Developmental Change

Explain how people can grow and change at any time in life. - Look at Culture and Society

Discuss how culture and society influence how people grow and behave. - Know About Different Ages

Understand the differences between physical age, mental age, and how old people feel socially. - Apply Development Ideas

Use what you learn about development to explain real-life situations. - See the Big Picture

Learn how different fields like biology, psychology, and sociology work together to explain how people develop.

Psychology refers to the scientific study of the mind and behavior. Psychologists agree that there is no one right way to study the way people think or behave. There are, however, various schools of thought that evolved throughout the development of psychology that continue to shape the way we investigate human behavior. For example, some psychologists might attribute a certain behavior to biological factors such as genetics while another psychologist might consider early childhood experiences to be a more likely explanation for the behavior. Many expert psychologists focus their entire careers on just one facet of psychology, such as developmental psychology or cognitive psychology, or even more specifically, newborn intelligence or language processing.

The four primary goals of psychology—to describe, explain, predict, and change behavior— are similar to those you probably have every day as you interact with others.

When dealing with children, for example, you might ask questions such as:

“What are they doing?” (describing)

“Why are they doing that?” (explaining)

“What would happen if I responded in this way?” (predicting)

“What can I do to get them to stop doing that?” (changing)

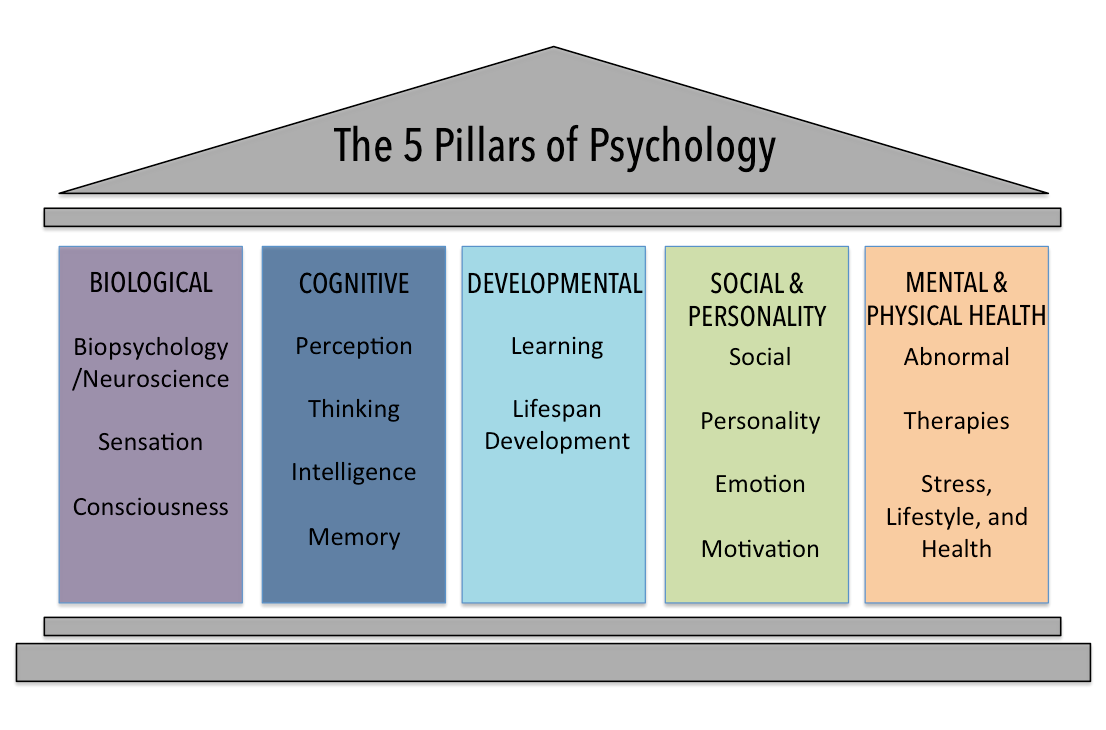

While the field of study is large and vast, the American Psychological Association (APA) has created a model of the various branches and sub-fields within the discipline to visualize how the sub-fields are all interconnected and essential in understanding behavior and mental processes. The five main psychological pillars, or domains, as we will refer to them, which are:

Domain 1: Biological (includes neuroscience, consciousness, and sensation)

Domain 2: Cognitive (includes the study of perception, cognition, memory, and intelligence)

Domain 3: Development (includes learning and conditioning, lifespan development, and language)

Domain 4: Social and Personality (includes the study of personality, emotion, motivation, gender, and culture)

Domain 5: Mental and Physical Health (includes abnormal psychology, therapy, and health psychology)

The five pillars, or domains, of psychology. Image adapted from Gurung, R. A., Hackathorn, J., Enns, C., Frantz, S., Cacioppo, J. T., Loop, T., & Freeman, J. E. (2016) article “Strengthening introductory psychology: A new model for teaching the introductory course” from American Psychologist.

These five domains cover the main viewpoints, or perspectives, of psychology. These perspectives emphasize certain assumptions about behavior and provide a framework for psychologists in conducting research and analyzing behavior. They include some you have already read about, including Freud’s psychodynamic perspective, behaviorism, humanism, and the cognitive approach. Other perspectives include the biological perspective, evolutionary, and socio-cultural perspectives.

Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of development across a lifespan. Developmental psychologists are interested in processes related to physical maturation. However, their focus is not limited to the physical changes associated with aging, as they also focus on changes in cognitive skills, moral reasoning, social behavior, and other psychological attributes.

WATCH THIS video below for more information on developmental psychology or view online.

The History of Developmental Psychology

The scientific study of children began in the late nineteenth century and blossomed in the early twentieth century as pioneering psychologists sought to uncover the secrets of human behavior by studying its development. Developmental psychology made an early appearance in a more literary form, however. William Shakespeare had his melancholy character, “Jacques” (in As You Like It), articulate the “seven ages of man,” which included three stages of childhood and four of adulthood.

Arnold Gesell

Arnold Gesell, a student of G. Stanley Hall, carried out the first large-scale detailed study of children’s behavior, authoring several books on the topic in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s. His research revealed consistent patterns of development, supporting his view that human development depends on biological “maturation,” with the environment providing only minor variations in the age at which a skill might emerge but never affecting the sequence or pattern. Gesell’s research produced norms, such as the order and the normal age range in which a variety of early behaviors such as sitting, crawling, and walking emerge. In conducting his studies, Gesell developed sophisticated observational techniques, including one-way viewing screens and recording methods that did not disturb the child.

Jean Piaget

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) is considered one of the most influential psychologists of the twentieth century, and his stage theory of cognitive development revolutionized our view of children’s thinking and learning. His work inspired more research than any other theorist, and many of his concepts are still foundational to developmental psychology. His interest lay in children’s knowledge, their thinking, and the qualitative differences in their thinking as it develops. Although he called his field “genetic epistemology,” stressing the role of biological determinism, he also assigned great importance to experience. In his view, children “construct” their knowledge through processes of “assimilation,” in which they evaluate and try to understand new information, based on their existing knowledge of the world, and “accommodation,” in which they expand and modify their cognitive structures based on new experiences.

Modern developmental psychology generally focuses on how and why certain modifications throughout an individual’s life-cycle (cognitive, social, intellectual, personality) and human growth change over time. There are many theorists that have made, and continue to make, a profound contribution to this area of psychology, amongst whom is Erik Erikson who developed a model of eight stages of psychological development. He believed that humans developed in stages throughout their lifetimes and this would affect their behaviors.

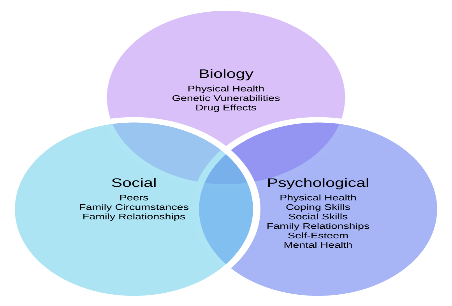

The Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial model states that behaviors, such as health and illness, are determined by a dynamic interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors.

Biopsychosocial model of health and illness

The biopsychosocial model of health and illness is a framework developed by George L. Engel that states that interactions between biological, psychological, and social factors determine the cause, manifestation, and outcome of wellness and disease. Historically, popular theories like the nature versus nurture debate posited that any one of these factors was sufficient to change the course of development. The biopsychosocial model argues that any one factor is not sufficient; it is the interplay between people’s genetic makeup (biology), mental health and behavior (psychology), and social and cultural context that determine the course of their health-related outcomes.

Biological Influences on Health:

Biological influences on health include an individual’s genetic makeup and history of physical trauma or infection. Many disorders have an inherited genetic vulnerability. The greatest single risk factor for developing schizophrenia, for example is having a first-degree relative with the disease (risk is 6.5%); more than 40% of monozygotic twins of those with schizophrenia are also affected. If one parent is affected the risk is about 13%; if both are affected the risk is nearly 50%.

It is clear that genetics have an important role in the development of schizophrenia, but equally clear is that there must be other factors at play. Certain non-biological (i.e., environmental) factors influence the expression of the disorder in those with a pre-existing genetic risk.

Psychological Influences on Health

The psychological component of the biopsychosocial model seeks to find a psychological foundation for a particular symptom or array of symptoms (e.g., impulsivity, irritability, overwhelming sadness, etc.). Individuals with a genetic vulnerability may be more likely to display negative thinking that puts them at risk for depression; alternatively, psychological factors may exacerbate a biological predisposition by putting a genetically vulnerable person at risk for other risk behaviors. For example, depression on its own may not cause liver problems, but a person with depression may be more likely to abuse alcohol, and, therefore, develop liver damage. Increased risk-taking leads to an increased likelihood of disease.

Social Influences on Health

Social factors include socioeconomic status, culture, technology, and religion. For instance, losing one’s job or ending a romantic relationship may place one at risk of stress and illness. Such life events may predispose an individual to developing depression, which may, in turn, contribute to physical health problems. The impact of social factors is widely recognized in mental disorders like anorexia nervosa (a disorder characterized by excessive and purposeful weight loss despite evidence of low body weight). The fashion industry and the media promote an unhealthy standard of beauty that emphasizes thinness over health. This exerts social pressure to attain this “ideal” body image despite the obvious health risks.

Cultural Factors

Also included in the social domain are cultural factors. For instance, differences in the circumstances, expectations, and belief systems of different cultural groups contribute to different prevalence rates and symptom expression of disorders. For example, anorexia is less common in non-western cultures because they put less emphasis on thinness in women.

Culture can vary across a small geographic range, such as from lower-income to higher-income areas, and rates of disease and illness differ across these communities accordingly. Culture can even change biology, as research on epigenetics is beginning to show. Specifically, research on epigenetics suggests that the environment can actually alter an individual’s genetic makeup. For instance, research shows that individuals exposed to overcrowding and poverty are more at risk for developing depression with actual genetic mutations forming over only a single generation.

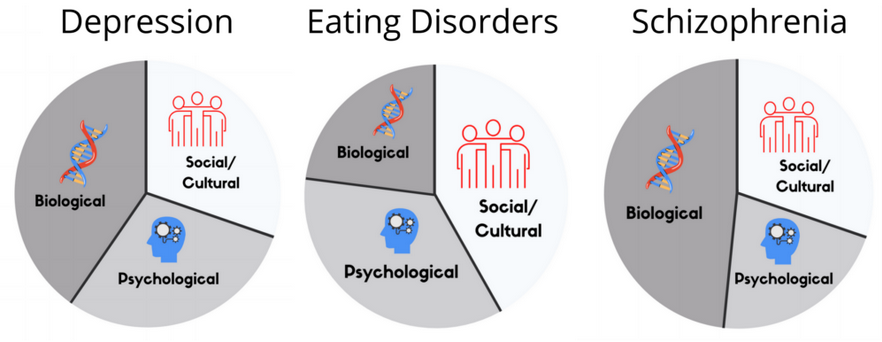

Application of the Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial model states that the workings of the body, mind, and environment all affect each other. According to this model, none of these factors in isolation is sufficient to lead definitively to health or illness—it is the deep interrelation of all three components that leads to a given outcome.

Health promotion must address all three factors, as a growing body of empirical literature suggests that it is the combination of health status, perceptions of health, and sociocultural barriers to accessing health care that influence the likelihood of a patient engaging in health-promoting behaviors, like taking medication, proper diet or nutrition, and engaging in physical activity. In addition, it is important to realize that the particular patterns of how the biopsychosocial model functions also vary by the disorder. Some disorders have a heavier influence due to genetic and other biological factors while other disorders are more heavily influenced by social or psychological elements. If you examine figure (a) in the image below for depression, you’ll see that biological elements have slightly greater influence on how a person’s life will turn out than the other elements, although both the psychological and social/cultural elements still play major roles. In contrast, in figure (b) of the image below, biological elements have a significantly smaller role in the development of eating disorders while social/cultural and psychological elements have a stronger influence. Even with a condition such as schizophrenia (see figure(c) in the image below) which is often incorrectly thought of by many as a “mental disease,” the biological elements still contribute less than 50% of the influence on whether a person will develop the disorder or not. This statistic is based on multiple studies demonstrating that the concordance rate between identical twins is less than half, a measure of the likelihood of an identical twin developing schizophrenia if the co-twin already has it. Said another way, this means that more than half of the time, even with a strongly biologically influenced disorder, an identical twin, a person with identical genes, will not develop schizophrenia. Clearly, social/cultural and psychological elements also play important roles even in this case, and it is possible that epigenetics also has some influence. You will learn more about these issues in later modules.

The Domains of Development

Read the following poem:

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety. (Wordsworth, 1802)

In this poem, William Wordsworth writes, “the child is father of the man.” What does this seemingly incongruous statement mean, and what does it have to do with lifespan development? Wordsworth might be suggesting that the person he is as an adult depends largely on the experiences he had in childhood. Consider the following questions: To what extent is the adult you are today influenced by the child you once were? To what extent is a child fundamentally different from the adult he grows up to be?

These are the types of questions developmental psychologists try to answer, by studying how humans change and grow from conception through childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and death. They view development as a lifelong process that can be studied scientifically across three developmental domains—physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development. Physical development involves growth and changes in the body and brain, the senses, motor skills, and health and wellness. Cognitive development involves learning, attention, memory, language, thinking, reasoning, and creativity. Psychosocial development involves emotions, personality, and social relationships. We refer to these domains throughout the module.

Physical

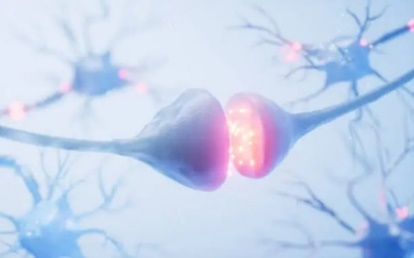

Many of us are familiar with the height and weight charts that pediatricians consult to estimate if babies, children, and teens are growing within normative ranges of physical development. We may also be aware of changes in children’s fine and gross motor skills, as well as their increasing coordination, particularly in terms of playing sports. But we may not realize that physical development also involves brain development, which not only enables childhood motor coordination but also greater coordination between emotions and planning in adulthood, as our brains are not done developing in infancy or childhood.

Physical development also includes puberty, sexual health, fertility, menopause, changes in our senses, and primary versus secondary aging. Healthy habits with nutrition and exercise are also important at every age and stage across the lifespan.

Cognitive

If we watch and listen to infants and toddlers, we can’t help but wonder how they learn so much so fast, particularly when it comes to language development. Then as we compare young children to those in middle childhood, there appear to be huge differences in their ability to think logically about the concrete world around them. Cognitive development includes mental processes, thinking, learning, and understanding, and it doesn’t stop in childhood. Adolescents develop the ability to think logically about the abstract world (and may like to debate matters with adults as they exercise their new cognitive skills!). Moral reasoning develops further, as does practical intelligence—wisdom may develop with experience over time. Memory abilities and different forms of intelligence tend to change with age. Brain development and the brain’s ability to change and compensate for losses is significant to cognitive functions across the lifespan, too. Watch the following video to learn more about the advancement if cognitive development and the theories that influence how we view these changes.

Psychosocial

Development in this domain involves what’s going on both psychologically and socially. Early on, the focus is on infants and caregivers, as temperament and attachment are significant. As the social world expands and the child grows psychologically, different types of play and interactions with other children and teachers become important. Psychosocial development involves emotions, personality, self-esteem, and relationships. Peers become more important for adolescents, who are exploring new roles and forming their own identities. Dating, romance, cohabitation, marriage, having children, and finding work or a career are all parts of the transition into adulthood. Psychosocial development continues across adulthood with similar (and some different) developmental issues of family, friends, parenting, romance, divorce, remarriage, blended families, caregiving for elders, becoming grandparents and great grandparents, retirement, new careers, coping with losses, and death and dying.

As you may have already noticed, physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development are often interrelated, as with the example of brain development. We will be examining human development in these three domains in detail throughout the modules in this course, as we learn about infancy/toddlerhood, early childhood, middle childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, middle adulthood, and late adulthood development, as well as death and dying.

Key Issues in Human Development

There are many different theoretical approaches regarding human development. As we evaluate them in this course, recall that human development focuses on how people change, and the approaches address the nature of change in different ways:

- Is the change smooth or uneven (continuous versus discontinuous)?

- Is this pattern of change the same for everyone, or are there different patterns of change (one course of development versus many courses)?

- How do genetics and environment interact to influence development (nature versus nurture)?

Is Development Continuous or Discontinuous?

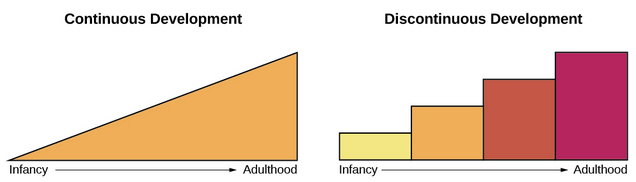

Is human development best characterized as a slow, gradual process, or as one of more abrupt change? The answer to that question often depends on which developmental theorist you ask and which topic is being studied. Continuous development theories view development as a cumulative process, gradually improving on existing skills (see figure below). With this type of development, there is a gradual change. Consider, for example, a child’s physical growth: adding inches to their height year by year. In contrast, theorists who view development as discontinuous believe that development takes place in unique stages and that it occurs at specific times or ages. With this type of development, the change is more sudden, such as an infant’s ability to demonstrate awareness of object permanence (which is a cognitive skill that develops toward the end of infancy, according to Piaget’s cognitive theory—more on that theory later.

Is There One Course of Development or Many?

Is development essentially the same, or universal, for all children (i.e., there is one course of development) or does development follow a different course for each child, depending on the child’s specific genetics and environment (i.e., there are many courses of development)? Do people across the world share more similarities or more differences in their development? How much do culture and genetics influence a child’s behavior?

Stage theories hold that the sequence of development is universal. For example, in cross-cultural studies of language development, children from around the world reach language milestones in a similar sequence. Infants in all cultures coo before they babble. They begin babbling at about the same age and utter their first word around 12 months old. Yet we live in diverse contexts that have a unique effect on each of us. For example, researchers once believed that motor development follows one course for all children regardless of culture. However, child care practices vary by culture, and different practices have been found to accelerate or inhibit achievement of developmental milestones such as sitting, crawling, and walking.

For instance, let’s look at the Aché society in Paraguay. They spend a significant amount of time foraging in forests. While foraging, Aché mothers carry their young children, rarely putting them down in order to protect them from getting hurt in the forest. Consequently, their children walk much later: They walk around 23–25 months old, in comparison to infants in Western cultures who begin to walk around 12 months old. However, as Aché children become older, they are allowed more freedom to move about, and by about age 9, their motor skills surpass those of U.S. children of the same age: Aché children are able to climb trees up to 25 feet tall and use machetes to chop their way through the forest. As you can see, our development is influenced by multiple contexts, so the timing of basic motor functions may vary across cultures. However, the functions themselves are present in all societies.

Are there Critical or Sensitive Periods of Development?

Various developmental milestones are universal in timing. For example, most children begin learning and expressing language during their first year. However, what happens if a person misses that window of typical experience? What if the child were not exposed to language early in life, could they learn language in later years? Does the timing of experience influence development, and can it be corrected later?

Psychologists believe that there are time spans in which a person is biologically ready for certain developments, but successful progress is reliant on the person having essential experiences during that time. If these experiences fail to occur or occur after the time span ends, then the person will not develop normally or may not fully recover, even with later intervention.

Some aspects of development have critical periods; finite time spans in which specific experiences must occur for successful development. Once this period ends, later experiences would have no impact on this aspect of development. Failure to have the necessary experiences during the critical period will result in permanent impairments. For instance, a person that does not receive minimal nutrition during childhood would not reach their full height potential by adulthood. Even with excellent nutrition during adulthood, they would never grow taller because their critical period of growth has ended.

More often, developmental aspects are considered to have sensitive periods. Like critical periods, a sensitive period requires particular experiences during a specific time for development to occur. However, with sensitive periods, experiences after the period ends can support developmental gains later in life. It is not to say that post-period interventions will always be simple or successful. For example, someone that was not exposed to language in early childhood, with intervention and great effort, may be able to make some gains in late childhood, but may not fully recover all language-related skills.

How Do Nature and Nurture Influence Development?

Are we who we are because of genetics, or are we who we are because of our environment? For instance, why do biological children sometimes act like their parents—is it because of genetics or because of early childhood environment and what the child has learned from their parents? What about children who are adopted—are they more like their biological families or more like their adoptive families? And how can siblings from the same family be so different?

This longstanding question is known in psychology as the nature versus nurture debate. For any particular aspect of development, those on the side of nature would argue that heredity plays the most important role in bringing about that feature. While those on the side of nurture would say that one’s environment is most significant in shaping the way we develop. However, most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single outcome as a result solely of nature or nurture.

We are all born with specific genetic traits inherited from our parents, such as eye color, height, and certain personality traits. Beyond our basic genotype, however, there is a deep interaction between our genes and our environment. Our unique experiences in our environment influence whether and how particular traits are expressed, and at the same time, our genes influence how we interact with our environment (Diamond, 2009; Lobo, 2008). There is a reciprocal interaction between nature and nurture as they both shape who we become, but the debate continues as to the relative contributions of each.

The Lifespan Perspective

Lifespan development involves the exploration of biological, cognitive, and psychosocial changes and constants that occur throughout the entire course of life. It has been presented as a theoretical perspective, proposing several fundamental, theoretical, and methodological principles about the nature of human development. An attempt by researchers has been made to examine whether research on the nature of development suggests a specific metatheoretical worldview. Several beliefs, taken together, form the “family of perspectives” that contribute to this particular view.

German psychologist Paul Baltes, a leading expert on lifespan development and aging, developed one of the approaches to studying development called the lifespan perspective. This approach is based on several key principles:

- Development occurs across one’s entire life, or is lifelong.

- Development is multidimensional, meaning it involves the dynamic interaction of factors like physical, emotional, and psychosocial development

- Development is multidirectional and results in gains and losses throughout life

- Development is plastic, meaning that characteristics are malleable or changeable.

- Development is influenced by contextual and socio-cultural influences.

- Development is multidisciplinary.

Development is Lifelong

Lifelong development means that development is not completed in infancy or childhood or at any specific age; it encompasses the entire lifespan, from conception to death. The study of development traditionally focused almost exclusively on the changes occurring from conception to adolescence and the gradual decline in old age; it was believed that the five or six decades after adolescence yielded little to no developmental change at all. The current view reflects the possibility that specific changes in development can occur later in life, without having been established at birth. The early events of one’s childhood can be transformed by later events in one’s life. This belief clearly emphasizes that all stages of the lifespan contribute to the regulation of the nature of human development.

Many diverse patterns of change, such as direction, timing, and order, can vary among individuals and affect the ways in which they develop. For example, the developmental timing of events can affect individuals in different ways because of their current level of maturity and understanding. As individuals move through life, they are faced with many challenges, opportunities, and situations that impact their development. Remembering that development is a lifelong process helps us gain a wider perspective on the meaning and impact of each event.

Development is Multidimensional

By multidimensionality, Baltes is referring to the fact that a complex interplay of factors influence development across the lifespan, including biological, cognitive, and socioemotional changes. Baltes argues that a dynamic interaction of these factors is what influences an individual’s development.

For example, in adolescence, puberty consists of physiological and physical changes with changes in hormone levels, the development of primary and secondary sex characteristics, alterations in height and weight, and several other bodily changes. But these are not the only types of changes taking place; there are also cognitive changes, including the development of advanced cognitive faculties such as the ability to think abstractly. There are also emotional and social changes involving regulating emotions, interacting with peers, and possibly dating. The fact that the term puberty encompasses such a broad range of domains illustrates the multidimensionality component of development.

Development is Multidirectional

Baltes states that the development of a particular domain does not occur in a strictly linear fashion but that development of certain traits can be characterized as having the capacity for both an increase and decrease in efficacy over the course of an individual’s life.

If we use the example of puberty again, we can see that certain domains may improve or decline in effectiveness during this time. For example, self-regulation is one domain of puberty which undergoes profound multidirectional changes during the adolescent period. During childhood, individuals have difficulty effectively regulating their actions and impulsive behaviors. Scholars have noted that this lack of effective regulation often results in children engaging in behaviors without fully considering the consequences of their actions. Over the course of puberty, neuronal changes modify this unregulated behavior by increasing the ability to regulate emotions and impulses. Inversely, the ability for adolescents to engage in spontaneous activity and creativity, both domains commonly associated with impulsive behavior, decrease over the adolescent period in response to changes in cognition. Neuronal changes to the limbic system and prefrontal cortex of the brain, which begin in puberty lead to the development of self-regulation, and the ability to consider the consequences of one’s actions (though recent brain research reveals that this connection will continue to develop into early adulthood).

Extending on the premise of multidirectionality, Baltes also argued that development is influenced by the “joint expression of features of growth (gain) and decline (loss)”. This relation between developmental gains and losses occurs in a direction to selectively optimize particular capacities. This requires the sacrificing of other functions, a process known as selective optimization with compensation. According to the process of selective optimization, individuals prioritize particular functions above others, reducing the adaptive capacity of particulars for specialization and improved efficacy of other modalities.

The acquisition of effective self-regulation in adolescents illustrates this gain/loss concept. As adolescents gain the ability to effectively regulate their actions, they may be forced to sacrifice other features to selectively optimize their reactions. For example, individuals may sacrifice their capacity to be spontaneous or creative if they are constantly required to make thoughtful decisions and regulate their emotions. Adolescents may also be forced to sacrifice their fast reaction times toward processing stimuli in favor of being able to fully consider the consequences of their actions.

Development is Plastic

Plasticity denotes intrapersonal variability and focuses heavily on the potentials and limits of the nature of human development. The notion of plasticity emphasizes that there are many possible developmental outcomes and that the nature of human development is much more open and pluralistic than originally implied by traditional views; there is no single pathway that must be taken in an individual’s development across the lifespan. Plasticity is imperative to current research because the potential for intervention is derived from the notion of plasticity in development. Undesired development or behaviors could potentially be prevented or changed.

A significant aspect of the aging process is cognitive decline. The dimensions of cognitive decline are partially reversible, however, because the brain retains the lifelong capacity for plasticity and reorganization of cortical tissue. Mahncke and colleagues developed a brain plasticity-based training program that induced learning in mature adults experiencing age-related decline.

A significant aspect of the aging process is cognitive decline. The dimensions of cognitive decline are partially reversible, however, because the brain retains the lifelong capacity for plasticity and reorganization of cortical tissue. Mahncke and colleagues developed a brain plasticity-based training program that induced learning in mature adults experiencing age-related decline.

This training program focused intensively on aural language reception accuracy and cognitively demanding exercises that have been proven to partially reverse the age-related losses in memory. It included highly rewarding novel tasks that required attention control and became progressively more difficult to perform. In comparison to the control group, who received no training and showed no significant change in memory function, the experimental training group displayed a marked enhancement in memory that was sustained at the 3-month follow-up period. These findings suggest that cognitive function, particularly memory, can be significantly improved in mature adults with age-related cognitive decline by using brain plasticity-based training methods.

Development is Contextual

In Baltes’ theory, the paradigm of contextualism refers to the idea that three systems of biological and environmental influences work together to influence development. Development occurs in context and varies from person to person, depending on factors such as a person’s biology, family, school, church, profession, nationality, and ethnicity. Baltes identified three types of influences that operate throughout the life course: normative age-graded influences, normative history-graded influences, and nonnormative influences. Baltes wrote that these three influences operate throughout the life course, their effects accumulate with time, and, as a dynamic package, they are responsible for how lives develop.

Normative age-graded influences are those biological and environmental factors that have a strong correlation with chronological age, such as puberty or menopause, or age-based social practices such as beginning school or entering retirement. Normative history-graded influences are associated with a specific time period that defines the broader environmental and cultural context in which an individual develops. For example, development and identity are influenced by historical events of the people who experience them, such as the Great Depression, WWII, Vietnam, the Cold War, the War on Terror, or advances in technology.

This has been exemplified in numerous studies, including Nesselroade and Baltes’, showing that the level and direction of change in adolescent personality development was influenced as strongly by the socio-cultural settings at the time (in this case, the Vietnam War) as age-related factors. The study involved individuals of four different adolescent age groups who all showed significant personality development in the same direction (a tendency to occupy themselves with ethical, moral, and political issues rather than cognitive achievement). Similarly, Elder showed that the Great Depression was a setting that significantly affected the overall development of adult personalities, by showing a similar common personality development across age groups. Baltes’ theory also states that the historical socio-cultural setting had an effect on the development of an individual’s intelligence. The areas of influence that Baltes thought most important to the development of intelligence were health, education, and work. The first two areas, health and education, significantly affect adolescent development because healthy children who are educated effectively will tend to develop a higher level of intelligence. The environmental factors, health and education, have been suggested by Neiss and Rowe to have as much effect on intelligence as inherited intelligence.

Nonnormative influences are unpredictable and not tied to a certain developmental time in a person’s development or to a historical period. They are the unique experiences of an individual, whether biological or environmental, that shape the development process. These could include milestones like earning a master’s degree or getting a certain job offer or other events like going through a divorce or coping with the death of a child.

The most important aspect of contextualism as a paradigm is that the three systems of influence work together to affect development. The age-graded influences would help to explain the similarities within a cohort, the history-graded influences would help to explain the differences between cohorts, and the nonnormative influences would explain the idiosyncrasies of each adolescent’s individual development. When all influences are considered together, it provides a broader explanation of development throughout adulthood.

Other Contextual Influences on Development: Cohort, Socioeconomic Status, and Culture

What is meant by the word “context”? It means that we are influenced by when and where we live. Our actions, beliefs, and values are a response to the circumstances surrounding us. Sternberg describes contextual intelligence as the ability to understand what is called for in a situation. The key here is to understand that behaviors, motivations, emotions, and choices are all part of a bigger picture. Our concerns are such because of who we are socially, where we live, and when we live; they are part of a social climate and set of realities that surround us. Important social factors include cohort, social class, gender, race, ethnicity, and age. Let’s begin by exploring two of these: cohort and social class.

A cohort is a group of people who are born at roughly the same time period in a particular society. Cohorts share histories and contexts for living. Members of a cohort have experienced the same historical events and cultural climates which have an impact on the values, priorities, and goals that may guide their lives.

One important context that is sometimes mistaken for age is the cohort effect. Cohorts share histories and contexts for living. Members of a cohort have experienced the same historic events and cultural climates which have an impact on the values, priorities, and goals that may guide their lives.

A generation refers to all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively. Who make up the generations of our day? The Baby Boom represented a surge in birth rates that endured from 1946-1964 and declined to pre-Boom rates in 1965. Generation X or “Gen X” represents the children of the Baby Boomers which spilled into Generation Y or the “Millennials”. There are no precise dates when Generation Y starts and ends. Researchers and commentators use birth years ranging from the early 1981s to the early 2000s. Generation Z is one name used for the cohort of people born after the Millennial Generation. There is no agreement on the exact dates of the generation with some sources starting from the mid-2000s to the present day.

Generational influences example

Consider a young boy’s concerns as he grows up in the United States during World War II. What his family buys is limited by their small budget and by a governmental program set up to ration food and other materials that are in short supply because of the war. He is eager rather than resentful about being thrifty and sees his actions as meaningful contributions to the good of others. As he grows up and has a family of his own, he is motivated by images of success tied to his past experience: a successful man is one who can provide for his family financially, who has a wife who stays at home and cares for the children, and children who are respectful but enjoy the luxury of days filled with school and play without having to consider the burdens of society’s struggles. He marries soon after completing high school, has four children, works hard to support his family and is able to do so during the prosperous postwar economics of the 1950s in America. But economic conditions change in the mid-1960s and through the 1970s. His wife begins to work to help the family financially and to overcome her boredom with being a stay-at-home mother. The children are teenagers in a very different social climate: one of social unrest, liberation, and challenging the status quo. They are not sheltered from the concerns of society; they see television broadcasts in their own living room of the war in Vietnam and they fear the draft. And they are part of a middle-class youth culture that is very visible and vocal. His employment as an engineer eventually becomes difficult as a result of downsizing in the defense industry. His marriage of 25 years ends in divorce. This is not a unique personal history, rather it is a story shared by many members of his cohort. Historic contexts shape our life choices and motivations as well as our eventual assessments of success or failure during the course of our existence.

WATCH THIS video below or view online. This video describes the normative history-graded influences that shaped the development of seven generations over the past 125 years of United States history. Can you identify your generation? Does the description seem accurate?

Another context that influences our lives is our social standing, socioeconomic status, or social class. Socioeconomic status is a way to identify families and households based on their shared levels of education, income, and occupation. While there is certainly individual variation, members of a social class tend to share similar lifestyles, patterns of consumption, parenting styles, stressors, religious preferences, and other aspects of daily life.

Culture is often referred to as a blueprint or guideline shared by a group of people that specifies how to live. It includes ideas about what is right and wrong, what to strive for, what to eat, how to speak, what is valued, as well as what kinds of emotions are called for in certain situations. Culture teaches us how to live in a society and allows us to advance because each new generation can benefit from the solutions found and passed down from previous generations.

Culture is learned from parents, schools, churches, media, friends, and others throughout a lifetime. The kinds of traditions and values that evolve in a particular culture serve to help members function in their own society and to value their own society. We tend to believe that our own culture’s practices and expectations are the right ones. This belief that our own culture is superior is called ethnocentrism and is a normal by-product of growing up in a culture. It becomes a roadblock, however, when it inhibits understanding of cultural practices from other societies. Cultural relativity is an appreciation for cultural differences and the understanding that cultural practices are best understood from the standpoint of that particular culture.

Culture is an extremely important context for human development and understanding development requires being able to identify which features of development are culturally based. This understanding is somewhat new and still being explored. So much of what developmental theorists have described in the past has been culturally bound and difficult to apply to various cultural contexts. For example, Erikson’s theory that teenagers struggle with identity assumes that all teenagers live in a society in which they have many options and must make an individual choice about their future. In many parts of the world, one’s identity is determined by family status or society’s dictates. In other words, there is no choice to make.

Even the most biological events can be viewed in cultural contexts that are extremely varied. Consider two very different cultural responses to menstruation in young girls. In the United States, girls in public school often receive information on menstruation around 5th grade, get a kit containing feminine hygiene products, and receive some sort of education about sexual health. Contrast this with some developing countries where menstruation is not publicly addressed, or where girls on their period are forced to miss school due to limited access to feminine products or unjust attitudes about menstruation.

Development is Multidisciplinary

Any single discipline’s account of development across the lifespan would not be able to express all aspects of this theoretical framework. That is why it is suggested explicitly by lifespan researchers that a combination of disciplines is necessary to understand development. Psychologists, sociologists, neuroscientists, anthropologists, educators, economists, historians, medical researchers, and others may all be interested and involved in research related to the normative age-graded, normative history-graded, and nonnormative influences that help shape development. Many disciplines are able to contribute important concepts that integrate knowledge, which may ultimately result in the formation of a new and enriched understanding of development across the lifespan.

Conceptions of Age

How old are you? Chances are you would answer that question based on the number of years since your birth, or what is called your chronological age. Ever felt older than your chronological age? Some days we might “feel” like we are older, especially if we are not feeling well, are tired, or are stressed out. We might notice that a peer seems more emotionally mature than we are, or that they are physically more capable. So years since birth is not the only way we can conceptualize age.

Biological age: Another way developmental researchers can think about the concept of age is to examine how quickly the body is aging, this is your biological age. Several factors determine the rate at which our body ages. Our nutrition, level of physical activity, sleeping habits, smoking, alcohol consumption, how we mentally handle stress, and the genetic history of our ancestors, to name but a few.

Biological age: Another way developmental researchers can think about the concept of age is to examine how quickly the body is aging, this is your biological age. Several factors determine the rate at which our body ages. Our nutrition, level of physical activity, sleeping habits, smoking, alcohol consumption, how we mentally handle stress, and the genetic history of our ancestors, to name but a few.

Psychological age: Our psychologically adaptive capacity compared to others of our chronological age is our psychological age. This includes our cognitive capacity along with our emotional beliefs about how old we are. An individual who has cognitive impairments might be 20 years of age yet has the mental capacity of an 8 year-old. A 70 year-old might be travelling to new countries, taking courses at college, or starting a new business. Compared to others of our age group, we may be more or less adaptive and excited to meet new challenges. Remember you are as young or old as you feel.

Social age: Our social age is based on the social norms of our culture and the expectations our culture has for people of our age group. Our culture often reminds us whether we are “on target” or “off target” for reaching certain social milestones, such as completing our education, moving away from home, having children, or retiring from work. However, there have been arguments that social age is becoming less relevant in the 21st century (Neugarten, 1979; 1996). If you look around at your fellow students in your courses at college you might notice more people who are older than the more traditional aged college students, those 18 to 25. Similarly, the age at which people are moving away from the home of their parents, starting their careers, getting married or having children, or even whether they get married or have children at all, is changing.

Those who study lifespan development recognize that chronological age does not completely capture a person’s age. Our age profile is much more complex than this. A person may be physically more competent than others in their age group, while being psychologically immature. So, how old are you?

Life Stages

Think about the lifespan and make a list of what you would consider the basic periods of development. How many periods or stages are on your list? Perhaps you have three: childhood, adulthood, and old age. Or maybe four: infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Developmentalists often break the lifespan into eight stages:

Prenatal Development

Infancy and Toddlerhood

Early Childhood

Middle Childhood

Adolescence

Early Adulthood

Middle Adulthood

Late Adulthood

In addition, the topic of “Death and Dying” is usually addressed after late adulthood since overall, the likelihood of dying increases in later life (though individual and group variations exist). Death and dying will be the topic of our last module, though it is not necessarily a stage of development that occurs at a particular age.

The list of the periods of development reflects unique aspects of the various stages of childhood and adulthood that will be explored in this book, including physical, cognitive, and psychosocial changes. So while both an 8-month-old and an 8-year-old are considered children, they have very different motor abilities, cognitive skills, and social relationships. Their nutritional needs are different, and their primary psychological concerns are also distinctive. The same is true of an 18-year-old and an 80-year-old, both considered adults. We will discover the distinctions between being 28 or 48 as well. But first, here is a brief overview of the stages.

Prenatal Development

Conception occurs and development begins. There are three stages of prenatal development: germinal, embryonic, and fetal periods. All of the major structures of the body are forming and the health of the mother is of primary concern. There are various approaches to labor, delivery, and childbirth, with potential complications of pregnancy and delivery, as well as risks and complications with newborns, but also advances in tests, technology, and medicine.

Conception occurs and development begins. There are three stages of prenatal development: germinal, embryonic, and fetal periods. All of the major structures of the body are forming and the health of the mother is of primary concern. There are various approaches to labor, delivery, and childbirth, with potential complications of pregnancy and delivery, as well as risks and complications with newborns, but also advances in tests, technology, and medicine.

The influences of nature (e.g., genetics) and nurture (e.g., nutrition and teratogens, which are environmental factors during pregnancy that can lead to birth defects) are evident. Evolutionary psychology, along with studies of twins and adoptions, help us understand the interplay of factors and the relative influences of nature and nurture on human development.

Infancy and Toddlerhood

The first year and a half to two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn, with many involuntary reflexes and a keen sense of hearing but poor vision, is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time.

Caregivers similarly transform their roles from those who manage feeding and sleep schedules to constantly moving guides and safety inspectors for mobile, energetic children. Brain development happens at a remarkable rate, as does physical growth and language development. Infants have their own temperaments and approaches to play. Interactions with primary caregivers (and others) undergo changes influenced by possible separation anxiety and the development of attachment styles. Social and cultural issues center around breastfeeding or formula-feeding, sleeping in cribs or in the bed with parents, toilet training, and whether or not to get vaccinations.

Early Childhood

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years, consisting of the years that follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling, roughly from around ages 2 to 5 or 6. As a preschooler, the child is busy learning language (with amazing growth in vocabulary), is gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may initially have interesting conceptions of size, time, space and distance, such as demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for doing something that brings the disapproval of others.

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years, consisting of the years that follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling, roughly from around ages 2 to 5 or 6. As a preschooler, the child is busy learning language (with amazing growth in vocabulary), is gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may initially have interesting conceptions of size, time, space and distance, such as demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for doing something that brings the disapproval of others.

Middle Childhood

The ages of 6-11 comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools participate in this process by comparing students and making these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. The brain reaches its adult size around age seven, but it continues to develop. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. Children also begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students; same-sex friendships are particularly salient during this period.

The ages of 6-11 comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools participate in this process by comparing students and making these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. The brain reaches its adult size around age seven, but it continues to develop. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. Children also begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students; same-sex friendships are particularly salient during this period.

Adolescence

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty; timing may vary by gender, cohort, and culture. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences. Research on brain development helps us understand teen risk-taking and impulsive behavior. A major developmental task during adolescence involves establishing one’s own identity. Teens typically struggle to become more independent from their parents. Peers become more important, as teens strive for a sense of belonging and acceptance; mixed-sex peer groups become more common. New roles and responsibilities are explored, which may involve dating, driving, taking on a part-time job, and planning for future academics.

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty; timing may vary by gender, cohort, and culture. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences. Research on brain development helps us understand teen risk-taking and impulsive behavior. A major developmental task during adolescence involves establishing one’s own identity. Teens typically struggle to become more independent from their parents. Peers become more important, as teens strive for a sense of belonging and acceptance; mixed-sex peer groups become more common. New roles and responsibilities are explored, which may involve dating, driving, taking on a part-time job, and planning for future academics.

Early Adulthood

Late teens, twenties, and thirties are often thought of as early adulthood (students who are in their mid to late 30s may love to hear that they are young adults!). It is a time when we are at our physiological peak but are most at risk for involvement in violent crimes and substance abuse. It is a time of focusing on the future and putting a lot of energy into making choices that will help one earn the status of a full adult in the eyes of others. Love and work are the primary concerns at this stage of life. In recent decades, it has been noted (in the U.S. and other developed countries) that young adults are taking longer to “grow up.” They are waiting longer to move out of their parents’ homes, finish their formal education, take on work/careers, get married, and have children. One psychologist, Jeffrey Arnett, has proposed that there is a new stage of development after adolescence and before early adulthood, called “emerging adulthood,” from 18 to 25 (or even 29) when individuals are still exploring their identities and don’t quite feel like adults yet. Cohort, culture, time in history, the economy, and socioeconomic status may be key factors in when youth take on adult roles.

Late teens, twenties, and thirties are often thought of as early adulthood (students who are in their mid to late 30s may love to hear that they are young adults!). It is a time when we are at our physiological peak but are most at risk for involvement in violent crimes and substance abuse. It is a time of focusing on the future and putting a lot of energy into making choices that will help one earn the status of a full adult in the eyes of others. Love and work are the primary concerns at this stage of life. In recent decades, it has been noted (in the U.S. and other developed countries) that young adults are taking longer to “grow up.” They are waiting longer to move out of their parents’ homes, finish their formal education, take on work/careers, get married, and have children. One psychologist, Jeffrey Arnett, has proposed that there is a new stage of development after adolescence and before early adulthood, called “emerging adulthood,” from 18 to 25 (or even 29) when individuals are still exploring their identities and don’t quite feel like adults yet. Cohort, culture, time in history, the economy, and socioeconomic status may be key factors in when youth take on adult roles.

Middle Adulthood

The late thirties (or age 40) through the mid-60s are referred to as middle adulthood. This is a period in which physiological aging that began earlier becomes more noticeable and a period at which many people are at their peak of productivity in love and work.

The late thirties (or age 40) through the mid-60s are referred to as middle adulthood. This is a period in which physiological aging that began earlier becomes more noticeable and a period at which many people are at their peak of productivity in love and work.

It may be a period of gaining expertise in certain fields and being able to understand problems and find solutions with greater efficiency than before. It can also be a time of becoming more realistic about possibilities in life; of recognizing the difference between what is possible and what is likely. Referred to as the sandwich generation, middle-aged adults may be in the middle of taking care of their children and also taking care of their aging parents. While caring about others and the future, middle-aged adults may also be questioning their own mortality, goals, and commitments, though not necessarily experiencing a “mid-life crisis.”

Late Adulthood

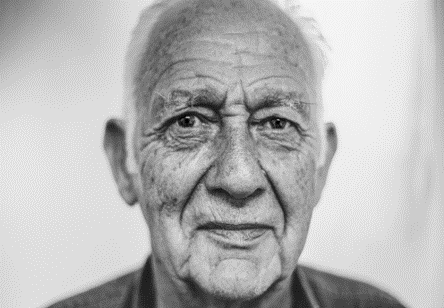

This period of the lifespan, late adulthood, has increased in the last 100 years, particularly in industrialized countries, as average life expectancy has increased. Late adulthood covers a wide age range with a lot of variation, so it is helpful to divide it into categories such as the “young old” (65-74 years old), “old old” (75-84 years old), and “oldest old” (85+ years old). The young old are similar to middle-aged adults; possibly still working, married, relatively healthy, and active. The old old have some health problems and challenges with daily living activities; the oldest old are often frail and in need of long-term care. However, many factors are involved and a better way to appreciate the diversity of older adults is to go beyond chronological age and examine whether a person is experiencing optimal aging (like the gentleman pictured to the left who is in very good health for his age and continues to have an active, stimulating life), normal aging (in which the changes are similar to most of those of the same age), or impaired aging (referring to someone who has more physical challenge and disease than others of the same age).

This period of the lifespan, late adulthood, has increased in the last 100 years, particularly in industrialized countries, as average life expectancy has increased. Late adulthood covers a wide age range with a lot of variation, so it is helpful to divide it into categories such as the “young old” (65-74 years old), “old old” (75-84 years old), and “oldest old” (85+ years old). The young old are similar to middle-aged adults; possibly still working, married, relatively healthy, and active. The old old have some health problems and challenges with daily living activities; the oldest old are often frail and in need of long-term care. However, many factors are involved and a better way to appreciate the diversity of older adults is to go beyond chronological age and examine whether a person is experiencing optimal aging (like the gentleman pictured to the left who is in very good health for his age and continues to have an active, stimulating life), normal aging (in which the changes are similar to most of those of the same age), or impaired aging (referring to someone who has more physical challenge and disease than others of the same age).

Death and Dying

The study of death and dying is seldom given the amount of coverage it deserves. Of course, there is a certain discomfort in thinking about death, but there is also a certain confidence and acceptance that can come from studying death and dying. Factors such as age, religion, and culture play important roles in attitudes and approaches to death and dying. There are different types of death: physiological, psychological, and social. The most common causes of death vary with age, gender, race, culture, and time in history. Dying and grieving are processes and may share certain stages of reactions to loss. There are interesting examples of cultural variations in death rituals, mourning, and grief. The concept of a “good death” is described as including personal choices and the involvement of loved ones throughout the process. Palliative care is an approach to maintain dying individuals’ comfort level, and hospice is a movement and practice that involves professional and volunteer care and loved ones. Controversy surrounds euthanasia (helping a person fulfill their wish to die)—active and passive types, as well as physician-assisted suicide, and legality varies within the United States.

Think it Over

Think about your own development. Which period or stage of development are you in right now? Are you dealing with similar issues and experiencing comparable physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development as described above? If not, why not? Are important aspects of development missing and if so, are they common for most of your cohort or unique to you?

|

Age Period |

Description |

|

Prenatal |

Starts at conception, continues through implantation in the uterine wall by the embryo, and ends at birth. |

|

Infancy and Toddlerhood |

Starts at birth and continues to two years of age |

|

Early Childhood |

Starts at two years of age until six years of age |

|

Middle and Late Childhood |

Starts at six years of age and continues until the onset of puberty |

|

Adolescence |

Starts at the onset of puberty until 18 |

|

Emerging Adulthood |

Starts at 18 until 25 |

|

Early Adulthood |

Starts at 25 until 40-45 |

|

Middle Adulthood |

Starts at 40-45 until 60-65 |

|

Late Adulthood |

Starts at 65 onward |

Health, Wellness, Sickness, and Disease

Health is the “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,” as defined by the World Health Organization in its Constitution. The organization goes on to state that families and communities are able to thrive when individuals are able to maintain health. Our employment, finances, mental and emotional functioning, and spiritual lives all interact with our overall health.

While the status of health is very real, it is also important to examine the aspects of health and illness that are socially constructed. Society shares an assumption of reality that creates a definition of both health and illness. The organization goes on to state that families and communities are able to thrive when individuals are able to maintain health. Our employment, finances, mental and emotional functioning, and spiritual lives all interact with our overall health. Illness has a biological component, yet it also embodies an independent element that is experienced by the person and observed by those outside of the illness. Societies construct the idea of “health” differently from place to place, and over time. For example, many societies consider health and health care to be a human right that all human beings are entitled to, but this is not universally true.

Society informs the definitions for when an illness can be considered a disability, eligibility for insurance and medical coverage, what illnesses are perceived as legitimate, when the reality of an illness is questioned, and what illnesses are stigmatized. These social constructs can, in themselves, contribute to differentiation in individual health as well as stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Sociologist Erving Goffman said, “Stigma is a process by which the reaction of others spoils normal identity.” A disease or illness that is “stigmatized” is one in which there is some societal disapproval or questioning of the integrity of people who have the disease, which can also include medical professionals and the person with the disease stigmatizing themselves.

Why Psychology Is Important in Nursing

“Think of psychology as the secret superpower nurses often employ. It helps them to see patients as whole individuals with their unique histories and personal battles, not just stats on a patient chart. By exploring beyond physical health and understanding past hardships or present mental struggles, nurses can provide standout care suited to each person’s specific needs.” – Nexus Nursing (2023)

READ THIS: Read Nexus Nursing’s article “Why Psychology is Important in Nursing.”

References and Resources

Listed below are the references and resources used to curate this module.

Bouchirika, Imed (Mar. 2023). The Four Goals of Psychology. Research.com. research.com/education/goals-of-psychology#TOC2.

Carroll, Patrick, et al. (n.d.). Introduction to Psychology. Lumen Waymaker. courses.lumenlearning.com/waymaker-psychology/.

Carter, Sarah, et al. (2019). Lifespan Development. Lumen Learning. courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/.

The Chicago School (Aug. 2020). Why is Psychology Important in Nursing Programs? The Chicago School. thechicagoschool.edu/insight/health-care/why-is-psychology-important-in-nursing-programs/.

Grucza, Ariel (May 2022). What is Developmental Psychology? WebMD. webmd.com/mental-health/what-is-developmental-psychology.

Lally, Martha, and Suzanne Valentine-French (Dec. 2020). socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Human_Development/Lifespan_Development_-_A_Psychological_Perspective_(Lally_and_Valentine-French).

Learning, L. (2020, August 1). Human development. Lifespan Development. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/lumenlife/chapter/human-development/

Miller, S.A., et al. (2022). Abnormal Psychology. Lumen Waymaker. courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-abnormalpsych/.

OpenStax and Lumen Learning (n.d.). General Psychology. Pressbooks. pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/.

Pearce, E.B. (Nov. 2022). Contemporary Families. LibreTexts Social Sciences. socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Sociology/Marriage_and_Family/Contemporary_Families_-_An_Equity_Lens_(Pearce_et_al.).

Spielman, R.M., et al. (Apr. 2020). Psychology 2e. OpenStax. openstax.org/details/books/psychology-2e.

Worthy, L.D., et al. (Sept. 2022). Culture and Psychology. LibreTexts Social Sciences. socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Psychology/Culture_and_Psychology_(Worthy_Lav